Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

April 21, 1997

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Campaign to Save our Public Hospitals v. Giuliani Hardbacks. Reply Brief, 1997. 96b88c49-6835-f011-8c4e-0022482c18b0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/eb696e10-89f7-4076-8042-64f1c9351872/reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

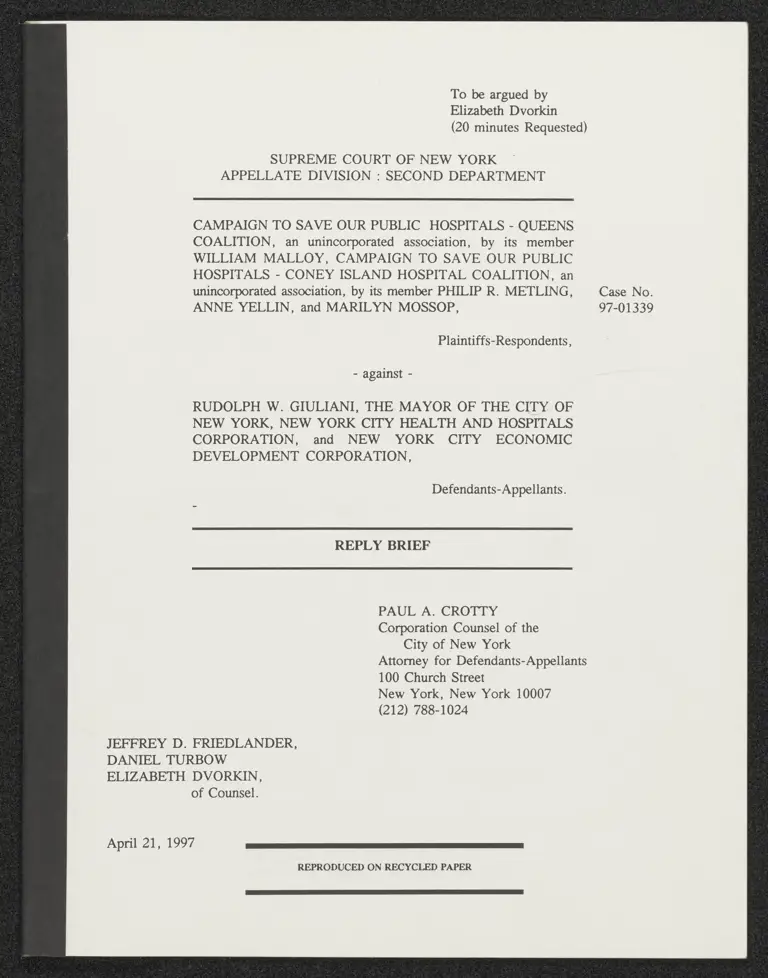

To be argued by

Elizabeth Dvorkin

(20 minutes Requested)

SUPREME COURT OF NEW YORK

APPELLATE DIVISION : SECOND DEPARTMENT

CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC HOSPITALS - QUEENS

COALITION, an unincorporated association, by its member

WILLIAM MALLOY, CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC

HOSPITALS - CONEY ISLAND HOSPITAL COALITION, an

unincorporated association, by its member PHILIP R. METLING, Case No.

ANNE YELLIN, and MARILYN MOSSOP, 97-01339

Plaintiffs-Respondents,

- against -

RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI, THE MAYOR OF THE CITY OF

NEW YORK, NEW YORK CITY HEALTH AND HOSPITALS

CORPORATION, and NEW YORK CITY ECONOMIC

DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION,

Defendants-Appellants.

REPLY BRIEF

PAUL A. CROTTY

Corporation Counsel of the

City of New York

Attorney for Defendants-Appellants

100 Church Street

New York, New York 10007

(212) 788-1024

JEFFREY D. FRIEDLANDER,

DANIEL TURBOW

ELIZABETH DVORKIN,

of Counsel.

April 21, 1997 a trl r,t ee a -__es. o uo s R RED

REPRODUCED ON RECYCLED PAPER

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. The HHC Board has the authority to sublease

Coney Island Hospital

eae elt elt ehae Leis ellie eo Keg lel wi ef Tek wie eo lee fle wile ike 8: tw Tele eile ek 0 Tey Ne a Uele Je

2. ULURP does not apply to the sublease of

Coney Island Hospital

Se Lee Le Te eh ee we ee a ee TL A AS ee ee eRe Ke Selah Side 1 Nie ae Eerie bes chek de

3. The Mayor has succeeded to the Board of

Estimate’s consent authority under the HHC Act

We lee tes ee Ge te Gre ee ee eS Te ie ne Sede Ter he ei eh le Sle lel el ell el eli led ie Tlie ae ee ie SL ee

10

SUPREME COURT OF NEW YORK

APPELLATE DIVISION : SECOND DEPARTMENT

CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC HOSPITALS - QUEENS

COALITION, an unincorporated association, by its member

WILLIAM MALLOY, CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC

HOSPITALS - CONEY ISLAND HOSPITAL COALITION, an

unincorporated association, by its member PHILIP R. METLING,

ANNE YELLIN, and MARILYN MOSSOP,

Plaintiffs-Respondents,

- against -

RUDOLPH WW. GIULIANI, THE MAYOR OF THE CITY OF

NEW YORK, NEW YORK CITY HEALTH AND HOSPITALS

CORPORATION, and NEW YORK CITY ECONOMIC

DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION,

Defendants-Appellants.

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

1. The HHC Board has the authority to sublease Coney Island Hospital

Plaintiffs’ argument that the HHC Board lacked the authority to sublease Coney Island

Hospital cannot withstand a quick review of the plain language of the HHC Act. The Legislature

gave HHC the power to sublease a hospital in the broadest possible terms. Unconsolidated Laws

§ 7385 states:

The language could not be clearer; HHC is fully authorized to sublease a hospital, as it has done

in the case of

The corporation shall have the following powers . .

[6] to dispose of by . . . lease or sublease . . . real or personal

property, including but not limited to a health facility, or any

interest therein for its corporate purposes. .

Coney Island Hospital.

The statutory grant of authority is so clear that the Council plaintiffs do not even discuss

this controlling section of the HHC Act, much less try to construe section 7385[6] to support any

other meaning. Instead they cite another section of the statute concerning when HHC may return

real property to the City or dispose of property that it no longer needs. See Unconsolidated

Laws § 7387[4]. Similarly, the Campaign plaintiffs argue about whether HHC could set up a

subsidiary pursuant to ‘section 7385[20]. Neither instance is applicable to this case. HHC is not

returning the hospital to the City, has not determined that the facility is no longer needed, and

is not setting up a subsidiary. Instead, HHC is acting pursuant to the authorization contained

in Unconsolidated Laws § 7385[6], which empowers the HHC Board to "dispose of" "a health

facility" "by sublease" "for its corporate purposes."

HHC has properly determined that the sublease of Coney Island Hospital will advance

"its corporate purposes." The purpose of HHC is to make high quality health care services

available, especially for the neediest New Yorkers. It is not to maintain government operation

of hospitals as a value in and of itself, as the Campaign plaintiffs argue.' Indeed, the language

of the HHC Act, which authorizes the HHC Board to sell, lease or sublease hospitals to further

its corporate purposes, Unconsolidated Laws § 7385[6], assumes that HHC can advance its

mission of ensuring high quality health care for the poor by subleasing a hospital to another

entity’s operation and control.

! The legislative history of the HHC Act is consistent with this statutory language. As then

Mayor Lindsay explained, HHC was created because the government was too inflexible to be

an effective provider of health care services. Plaintiffs have confused HHC pursuing its mission,

which it may do by subleasing a hospital to a private entity, with HHC retaining full operational

and managerial control of all the hospitals in the system.

2.

The sublease advances HHC’s purposes by using the private sector to improve the quality

and range of health care for the poor at Coney Island Hospital. The HHC Board's

environmental consultant advised that if HHC did not enter into the sublease, it would have to

shrink the services offered at Coney Island Hospital, including services for the poor and

uninsured, as HHC continued to lose its Medicaid patient base. Under the sublease, however,

the hospital would offer expanded services to the entire patient base, including the poor and

uninsured, because PHS? would be able to attract a sufficient number of insured patients to keep

the hospital viable (Co 566-67; Ca 556-57).*

The sublease also specifically advances HHC’s corporate purpose of providing health care

services for the poorest New Yorkers. PHS is obligated under to offer 115% of the cost of the

charity care that HHC currently provides, a figure that will be calculated net of government

reimbursements and indexed to increase with medical inflation. HHC’s consultant projected that

this obligation would be more than ample to meet demand as far into the future as it was possible

to project (Co 553; Ca 562). Thus, HHC has arranged for a sublease that will devote more

resources to charity care than HHC alone can dedicate, and will improve the range and

2 The Campaign plaintiffs are incorrect when they suggest that HHC cannot effectuate its

purposes by subleasing a hospital to a for profit corporation. The HHC Act explicitly permits

HHC to enter into subleases with private corporations. Unconsolidated Laws § 7385(8].

3 "PHS" refers to Primary Health Systems, Inc., which will manage Coney Island Hospital, and

Primary Health Systems New York, Inc., which will enter into the sublease.

4 Citations preceded by "Co" are to the Record on Appeal in the Council case. Citations

preceded by "Ca" are to the Record on Appeal in the Campaign case.

3-

availability of health care services at the hospital. The HHC Board rationally determined that

these outcomes will advance the Corporation's purposes.’

While the Campaign plaintiffs and their amicus supporters disagree with the HHC Board's

conclusions that PHS will provide more and better health care services for the poor and

uninsured than HHC could do without the sublease, their disagreement goes to the wisdom of

Board’s choice to entér into the sublease. It has no relevance to whether the HHC Board has

the authority to sublease Coney Island Hospital to PHS.

Finally, it is important to recognize the limits of the step HHC has taken. The HHC

Board has voted to sublease one hospital. It has not decided to privatize the entire HHC system.

Indeed, it has not even decided to sublease the two other hospitals that were the subject of an

Offering Memorandum. ' Thus, the case before this Court is very different than the proposed sale

of the entire Water System discussed in Giuliani v. Hevesi, N.Y. 2d , (March 20, 1997), and

relied on by plaintiffs. In that case, the Court of Appeals found that while the Water Authority

could issue bonds for individual water projects, it could not issue bonds to buy the entire Water

System. In the case at bar, the HHC Board is explicitly authorized by the HHC Act to sublease

a health facility. Reading "the words of the statute to ‘mean just what they say’" (Giuliani v.

Hevesi, Slip Op. at p. 14), HHC was fully authorized to "dispose of ... by sublease ... a health

facility ... for its corporate purposes." Unconsolidated Laws § 7385[6]. Accordingly, the

sublease of Coney Island Hospital is within the powers of HHC.

> The Campaign plaintiffs raise arguments concerning whether the HHC Board had sufficient

information before voting to approve the sublease. These claims have been fully litigated in

another action brought by the Campaign plaintiffs: Jones v. Giuliani, N.Y. Co. Index No.

117768/96 (Gangel-Jacob, J.), and will not be addressed in this brief.

i.

2. ULURP does not apply to the sublease of Coney Island Hospital

The sublease of Coney Island Hospital is not subject to ULURP because it is the

disposition of HHC’s property -- the leasehold interest in the hospital -- not the City’s property

-- the underlying fee, which cannot be conveyed in a sublease. Therefore, the sublease does not

fall into any of the categories of property dispositions that are within the scope of ULURP.

N.Y.C. Charter § 197-c [a]. See Mauldin v. New York City Transit Authority, 64 A.D. 2d

114, 117 (2d Dept. 1978) ("[Tlhe applicability of [Charter § 197-c] is necessarily limited to the

11 paragraphs of subdivision a thereof.")

This interpretation is also consistent with the reasons for ULURP review. ULURP

applies to dispositions of "property of the City" in order to bring all relevant issues concerning

the sale or lease by the City of its property to the attention of the City decision makers. The

City made its land use decision in the 1970’s, when it leased the hospitals to HHC. The

sublease will not alter the City’s decision to lease the hospital property. To the contrary, the

sublease explicitly permits no use of the property except as a health facility (Co 464; Ca 467).

When the City is not making the decision to enter into a sublease, and the City’s property rights

are not being transferred, ULURP review would serve no purpose.

Plaintiffs have advanced no instance to support their claim that a sublease by a non-City

agency is subject to ULURP when the City retains the fee. The sole practical example is to the

contrary; in the one instance where HHC subleased a portion of a health facility after ULURP

had been enacted, the sublease was not subjected to ULURP review. Indeed, when the Board

of Estimate approved that sublease pursuant to section 7385[6] of the HHC Act, it specifically

stated that it was acting only pursuant to the HHC Act, not pursuant to ULURP (Co310, Ca

342).

Further, even if a sublease by a non-City entity of its leasehold interest were within the

scope of ULURP, ULURP review would be pre-empted by the existing land use review process

incorporated by the State Legislature within the HHC Act. It is telling that plaintiffs fail even

to acknowledge the import of this section of Unconsolidated Laws § 7385[6].° Instead of a

ULURP type review, the statute establishes a more limited land use review process governing

only a limited class of property dispositions by HHC. The statute requires that when HHC plans

to enter into the sale or lease of a hospital, it must first hold a public hearing and the disposition

must be approved by the Board of Estimate (now the Mayor, see Point Three, infra). When

the Legislature specifically stated that it created HHC to free health care review from

cumbersome City decision making, it would be anomalous to hold that HHC could be subject

not only to the HHC Act land use review process but also to the City’s separate ULURP

process.

3. The Mayor has succeeded to the Board of Estimate’s consent authority under the HHC

Act

All the parties agree that the City retains its consent authority under Unconsolidated Laws

§ 7385[6], although the statute provides that the City will exercise that authority through the

Board of Estimate. The Board of Estimate was allocated the authority to consent to property

dispositions under the HHC Act because the Board exercised the same responsibility under the

Charter with regard to City property dispositions. See Charter § 384(a). When the Charter was

revised to eliminate the Board of Estimate, Charter § 384(a) was amended to give the authority

to consent to City dispositions of property to the Mayor. Accordingly, the Mayor is the City

¢ "[NJo health facility or other real property acquired or constructed by the corporation shall

be sold, leased or otherwise transferred by the corporation without public hearing by the

corporation after twenty days public notice and without the consent of the board of estimate."

-6-

officer who has replaced the Board of Estimate for the purpose of consenting to dispositions of

property by HHC as well.

Of course Charter § 384(a) does not directly govern HHC’s sublease of Coney Island

Hospital because it applies only to the disposition of City owned property and the sublease is the

disposition of HHC’s property. Instead, it is relevant because in construing legislation that has

not been amended to eliminate references to the Board of Estimate, the Charter instructs that the

body or officer who exercises similar authority should exercise the Board’s former role. Charter

§ 1152(e). Since the Mayor now exercises the authority formerly allocated to the Board of

Estimate to consent to dispositions of City property under section 384(a), it is the Mayor who

has succeeded to the comparable authority formerly allocated to the Board of Estimate under the

HHC Act.

The Council plaintiffs term the consent authority "legislative." The Council offers no

justification, explanation or support for its claim. The State Legislature has never treated the

City’s HHC consent authority as legislative. It originally allocated the authority to the Board

of Estimate, not to the Council, and it has failed to amend the HHC Act to allocate the consent

authority to the Council although the Council has proposed bills to that effect (Co 312-21; Ca

344-55). There is nothing legislative about reviewing leases or sales of property, that is why

the Mayor now exercises that authority on behalf of the City in connection with the disposition

of City owned property. See Charter § 384(a).

The Campin plaintiffs argue that the Council has a general land use authority. This

is incorrect. The Council has succeed to the Board of Estimate’s ULURP authority, but the

Council has no authority over land use issues that fall outside of ULURP. See Charter

§ § 28[al; 384[b][5]. The Charter Review Commission Report cited by plaintiffs describes the

7.

ULURP land use authority newly assigned to the Council. The Charter nowhere allocates to the

Council any non-ULURP land use authority.

The general non-allocated land use authority for issues that are not covered by ULURP

falls to the Mayor because the Charter grants all residual, non-allocated authority to the Mayor.

Charter § 8. Thus, to the extent that the HHC consent authority is different than the power to

consent to property dispositions under Charter § 384[a], as a non-ULURP based authority

concerning the disposition of property, it would fall to the Mayor under the Charter’s reserve

clause.

Finally, this Court should reject plaintiffs’ invitation to distort the law in order to lessen

the Mayor’s authority. The Mayor has not subleased an HHC hospital as the Council plaintiffs

contend. Under the HHC Act, only the HHC Board can decide to sublease a hospital. If the

Mayor had proposed to HHC that it sublease Coney Island Hospital and the Board decided

against the sublease, the Mayor would not have had the authority to enter into the sublease on

his own.

The HHC Act grants the Mayor a significant role in determining the membership of the

HHC Board, Unconsolidated Laws § 7384[1], but the Board is not the Mayor's alter ego.

Indeed, the Legislature gave the Council a role in influencing HHC decision making by having

five of the fifteen Mayoral appointees to the HHC Board designated by the Council. Thus, when

the Mayor exercises the City consent authority over HHC property dispositions, he or she

performs an independent review of an action taken by the Board of Directors of a public benefit

corporation, not a Mayoral agency. See generally Brennan v. City of New York, 59 N.Y.2d 791

(1983) (HHC is not a City agency).

This does not mean that HHC acts without oversight. A major step such as the sublease

of Coney Island Hospital cannot take effect until it is reviewed and approved by the HHC Board

after a public hearing, by the City through the Mayor, and by the State through the State

Department of Health. The law requires careful study before any of these steps are taken. The

HHC Board prepared an environmental assessment before approving the sublease pursuant to the

State Environmental Quality Review Act and the State Department of Health will require a

certificate of need application, which is a stringent health care review pursuant to Public Health

Law § § 2801, 2805.” Thus, although the Council has only a limited role in the process, the

HHC determination to sublease Coney Island Hospital will be carefully reviewed by many

governmental entities and the suggestion that the Mayor has simply subleased the hospital on his

own is without any basis in law.

7 Every step of the way so far has also been challenged in Court. In addition to the Council

and Campaign litigations, the Campaign plaintiffs joined with three members of the HHC Board

to challenge the sublease in Jones v. City of New York, N.Y. Co. Index No. 117768/96

(Gangel-Jacob, J.) and with the Commission on the Public's Health System to challenge the

SEQRA analysis in Commission v. HHC, N.Y. Co. Index No. 103242/97 (Gangel-Jacob, J.).

Dated:

CONCLUSION

THE ORDER AND JUDGMENT APPEALED FROM SHOULD

BE REVERSED AND SUMMARY JUDGMENT SHOULD BE

GRANTED DEFENDANTS.

New York, New York

April 21, 1997

PAUL A. CROTTY

Corporation Counsel of the City New Yak

Attorney for Defendants

100 Church Street

New York, New York 10007

(212) 788-1024

JEFFREY D. FRIEDLANDER,

DANIEL TURBOW,

ELIZABETH DVORKIN,

of Counsel

-10-