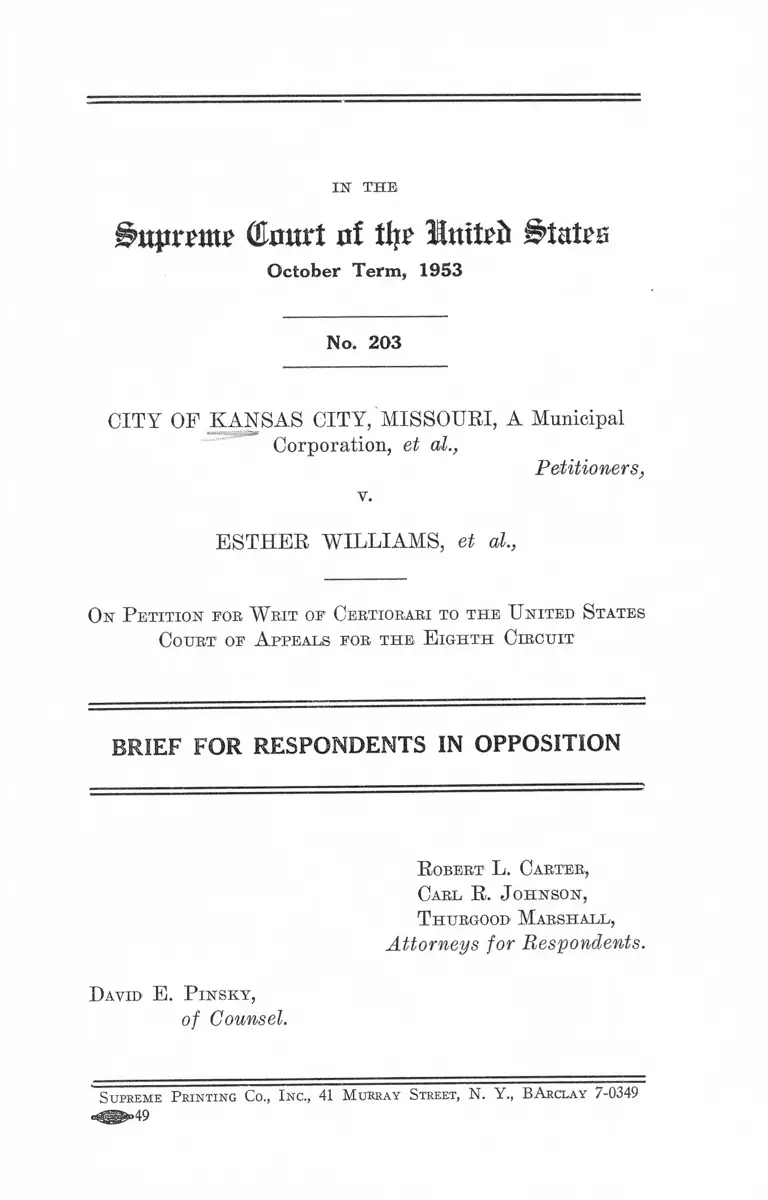

City of Kansas City, Missouri v. WIlliams Brief for Respondents in Opposition

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Kansas City, Missouri v. WIlliams Brief for Respondents in Opposition, 1953. 72edf596-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/eba69f74-558a-41b1-a684-453e0089ea51/city-of-kansas-city-missouri-v-williams-brief-for-respondents-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

(Emsrt of tlti' UnftoJt Stales

October Term, 1953

IN THE

No. 203

CITY OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, A Municipal

Corporation, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

ESTHER WILLIAMS, et al.,

On P etitio n foe. W rit of Certiorari to t h e U nited S tates

Court of A ppeals for t h e E ig h t h C ircu it

BRIEF FO R RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

R obert L. Carter,

Carl R . J o hnson ,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Respondents.

D avid E . P in sk y ,

of Counsel.

Supreme P rinting Co., I nc., 41 M urray Street, N. Y., BArclay 7-0349

1ST TH E

S>vtpxm t ( ta r t nf % luttrfr B M xb

O ctober Term , 1S53

No. 203

------- ----------- 0--- -------- ----- -—

C ity of K ansas. C ity , M issouri, A Municipal

Corporation, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

E sther W illiam s , et al.

On P etitio n for W r it of Certiorari to t h e U nited S tates

Court of A ppeals for t h e E ig h t h C ircu it

■— --------------------- ---------- 0 -------------------------------------

BRIEF FO R RESPONDENTS IN O PPO SITIO N

O pinions Below

The opinion of the District Court (R. 24-44) is reported

at 104 F. Supp. 848. The opinion of the Court of Appeals

(R. 92-101) is not yet officially reported — F. 2d —.

Jurisdiction.

The jurisdictional requisites are adequately set forth in

the petition.

Q uestion Presen ted

Whether the Fourteenth Amendment requires that peti

tioners admit respondents and all other Negroes similarly

2

situated to the use of the public wading, swimming and div

ing facilities afforded at Swope Park subject only to the

same rules, and regulations applicable alike to all other

persons?

S tatem ent

Respondents began this action in the district court seek

ing to enjoin petitioners from refusing to admit them to

the wading, swimming and diving facilities at Swope Park

solely because of their race and color. A trial on the merits

took place on February 15,1952 (R. 61 et seq.), and on April

18, 1952, the district court entered a memorandum opinion,

including findings of fact and conclusions of law (R. 24-44)

104 F. Supp. 848. On May 7,1952, a final decree was entered

in respondents’ favor restraining petitioners from refusing

to admit them to Swope Park Pool and “ all facilities oper

ated in connection therewith because of their race and

color” (R. 46-47). The Court of Appeals affirmed the

judgment of the district court (R. 92-101). Petitioners now

seek review of that judgment on certiorari in this Court.

ARGUMENT

I.

Petitioners have m ade no show ing th a t the tria l

court w as in e rro r in concluding th a t respondents w ere

no t afforded equal facilities for swim m ing enjoym ent.

The issue as raised and presented in the present posture

of this case is too well settled to warrant review by this

Court on certiorari. The decision of the court below that

petitioners have denied respondents substantial equality

with respect to public recreational facilities, as required by

3

the Fourteenth Amendment, is amply supported by the

record adduced at the trial of this cause (R. 33-35, 75).

None of these evidentiary facts which are set forth in

the memorandum opinion of the trial court (R. 25, 26, 27,

30, 34) are in dispute. Thus, petitioners do not purport to

■seek review of the evidentiary bases on which the judgment

in this case rests. Petitioners .merely state in effect that

while the trial court has the correct facts, its conclusions

are in error.

The undisputed evidentiary facts may be summarized

as follows: Swope Park is the main outdoor recreational

center of Kansas City. I t is composed of some 1800 acres,

contains a bathhouse, swimming pool, two golf courses, zoo,

a theatre, band pavilion, picnic shelter and facilities. All of

these facilities, except the swimming pool, are open to

Negroes and white persons alike. The swimming pool,

restricted to white persons, was constructed at a cost of

$534,544.40. I t is divided into three separate parts—

swimming pool, diving pool and wading pool. Three

thousand persons may be accommodated at the same time,

and there is no time limit on the individual’s use of the pool

during the hours when it is open to the public. A refresh

ment concession is operated in connection with the pool;

there is a sun beach, automatic dryers, and a separate

bath house. A fee for admission is charged.

The Parade Park Pool cost $60,000, and there are no

separate facilities for diving, swimming and wading, no

automatic dryers, no sun beach, no refreshment concession,

and no admission charge. It can only accommodate 250

people at a time, and its size is such that a time limit has

to be set on each person’s use of the pool.

On the basis of these facts, the trial court concluded

that the Parade Park Pool did not afford respondents

facilities for enjoyment of swimming equal to those avail

4

able at the Swope Park Pool. The facts would seem to

warrant that conclusion. Petitioners attempt to modify

these differences by emphasizing such factors as the acces

sibility of Parade Park Pool to those residential areas where

the Negro population is concentrated and the high percent

age of Negroes using Parade Park Pool as compared with

the low percentage of white population attracted to Swope

Park Pool. This, however, is patently beside the point.

The rights which respondents asserted are individual,

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629. What must be determined

is whether the individual, not the group, is afforded equal

protection. Thus, those factors involving group advantages

or disadvantages cannot be determinative of the issues in

this case. The court below was required to disregard such

factors in order to conform to the rulings of this Court,

and quite properly refused to take such irrelevant and

extraneous matters into account in deciding this case.

I I .

R espondents have been den ied equal trea tm en t.

The Court of Appeals found that respondents, in being-

denied use of the Swope Park Pool, were denied equal

treatment in the use and enjoyment of Swope Park Pool

for the purposes for which it was designed—a center for

recreational activities. The appellate court took a broader

view of the question than did the trial court. It found

that the public was encouraged to make use of Swope Park

as a comprehensive outlet for recreation. One could picnic,

lounge, play golf, go to theatre, visit a zoo, and Negroes

were admitted to the Park to enjoy these facilities. How

ever, the swimming pool which was a part of the compre

hensive recreational program offered at the Park was off

limits for Negroes. The court, viewing Swope Park in

terms of the function it was designed to perform, concluded

5

that Negroes having been admitted to the Park were denied

equal treatment in not being permitted to use all of its

facilities on the same basis as all other persons. White

people could go to Swope Park and indulge in its variety

of recreational offerings, including use of the swimming

pool. Negroes, on the other hand, could go to the park and

indulge in all of its offerings except the swimming pool.

Those desiring to swim had to leave Swope Park and go

to Parade Park Pool on the other side of town. Without

regard to a comparison of the two pools, on the basis of

physical facilities alone, the court quite properly concluded

that Negroes were not being accorded equal treatment with

respect to the use and enjoyment for which Swope Park was

designed. This, we think, is sound and accords with the

rationale of this Court in McLcmrm v. Oklahoma State

Regents, 339 U. S. 637.

Petitioners make no effort- to attack this reasoning but

take out of context the court’s statement that viewing the

case in this manner it was not necessary to make a detailed

comparison between the Parade Park Pool, some 4% to

6i/2 miles away with the Swope Park Pool on the basis of

mere physical facilities. The court was merely indicating

that the judgment of the trial court, enjoining petitioners

from refusing to admit respondents to the Swope Park

Pool on the basis of their race and color, could be sustained

without regard to the superiority of the Swope Park Pool

with respect to physical facilities. The Court of Appeals,

however, did not stop there. It went on to point to physical

differences between the two pools and concluded that such *

differences made it impossible for it to conclude that the

trial court was in error in deciding that respondents could

not enjoy equal facilities for swimming at the Parade Park

Pool. In short, the court’s opinion indicates that judg

ment for respondents could be rendered without a com

parison of physical facilities, under the rationale it adopted

which it preferred as a sounder approach to decision in

6

this case. However, if physical differences alone were

regarded as proper basis for decision, its opinion clearly

shows that it finds ample justification for judgment for

respondents on that ground.

CONCLUSION

It IS respectfu lly subm itted th a t no basis for review

of th is judgm ent exists and th e petition for certio rari

should be denied.

R obert L . Carter,

Carr R . J o h nso n ,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Respondents.

D avid E. P in sk y ,

of Counsel.

Dated: August 21, 1953.

■