Research Memorandum on Bozeman and Wilder v. State 2

Working File

January 1, 1981 - January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Research Memorandum on Bozeman and Wilder v. State 2, 1981. 242af400-f092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ebd1c753-3c8c-42ad-921a-434f4b6d7937/research-memorandum-on-bozeman-and-wilder-v-state-2. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

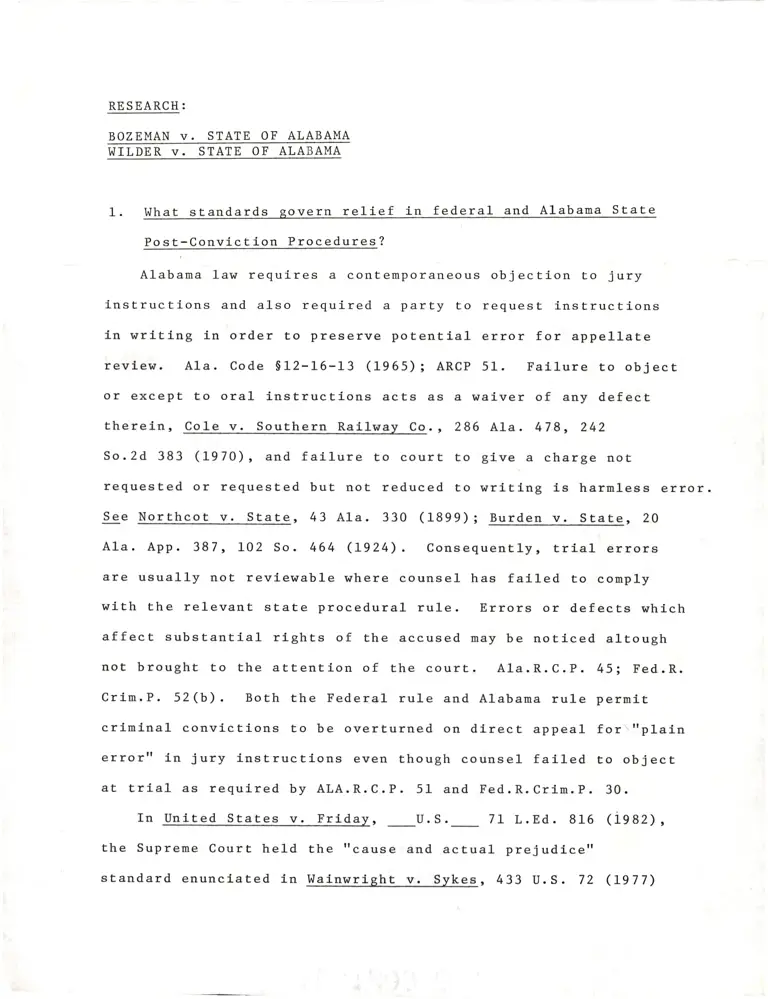

RESEARCH:

BOZEMAN V. STATE OF ALABAMA

WILDER V. STATE OF ALABAMA

1. What standards govern relief ln federal and Alabama State

Post-Conviction Procedures ?

Alabama 1aw requires a contemporaneous objection to jury

instructions and also required a party to reguest instructions

ln wrlting ln order to preserve potential error for appelJ-ate

revlew. A1a. Code Sl-2-l-6-13 (1965); ARCP 5l-. Failure ro objecr

or except to oral instructions acts as a waiver of any defect

thereln, Cole v. Southern Rallway Co., 286 A1a. 478, 242

So.2d 383 (1970), and failure to court to glve a charge not

requested or requested but not reduced to writing is harmless error.

See Northcot L Sl3ls, 43 Ala. 330 (1899); Lurde4 v. Srare, Z0

A1a. App. 387, L02 So. 464 (L924). Consequenrly, rrial errors

are usually not reviewabl-e where couns el_ has f aiLed to conply

wlth the relevant st,ate procedural- rul-e. Errors or def ects whlch

affect substantlal rlghts of the accused may be notlced altough

not brought to the attention of the court,. A1a.R. C.p. 45; Fed.R.

CrLm.P. 52(b). Both the Federal ruLe and Alabama rule permit

crlmlnal convlctions to be overturned on dlrect appeal for ttplaln

error" ln jury lnstructions even though counsel failed to object

at trlal- as requlred by ALA.R.C.P. 51 and Fed.R.Crim.P. 30.

In Unlted States v. Frlday, _U.S._ 71 L.Ed. 816 (1982),

the Supreme Court held the ttcause and actual prejudice"

standard enunclated in walnwrighr v. sykes, 433 u.s. 7z (L977)

governs relief on collateral attack following procedural- de-

fault at trial. In drawing thls conclusj.on the Court noted

that where counsel- has had an opportunity to object to instruct-

ions at tri-al and on direct appeal, but failed to do sor a

collateral challenge may not do service for an appeal-." Frady,

supra; E,e.g., I{111 v. U.S., 368 U.S. 424, 428-429 (L962).

Thus, the "p1ain errortt standard only governs relief on dj-rect

appeal from errors not objected to at trial.

To obtain federalcollateral relief, the petitioner must

demonstrate: (1) cause excusing the procedural default and;

(2) actual prejudice resulting from conplained errors. Frady.

The Federal Habeas Corpus Manual for Capital Cases llsts arguments

for showing cause and prejudice (pg. 4O7). In the case of

Wllder and Bozeman cause for fallure to request special instruct-

lons as required by S12-16-13 Ala. Code L975 may be established

(e1-aborate)

by asserting ineffective assistance of counseL.l To establish

aetual prejudice the complained error by ltself must have so

infected the entire trial that the resulting conviction violates

due process. Henderson v. Kibbe, 43L U.S. L45, L54, 52 L.Ed.2d

203 (L977). Several arguments establishing actual prejudice may

apply to the factual clrcumstances in the Wilder and Bozeman cases.

The arguments set out in the Federal Habeas Corpus Manual (p. 42L-

425) are as follows: (1) under the circumstances there was a

"reasonable possibil-1ty" that the error lnfluenced the verdict

of the trier of fact. See Chapman v. Callfornia, 386 U.S. 18,

24, 25-26 (L967) where prosecutorlal comment on peti-tioner

not taking the stand was not harmless error; (2) when the tainted

evidence is excluded, the evidence of guil-t at trial rras not

-2-

t'overwhelming" so that the error cannot with certainty be said

to be harmless beyond a reasonable doubt. E.g., chapman v.

California, supra at 24 (L977); (3) but for the rainted evidence,

a "rational juror" could not have found the petitioner guilty be-

yond a reasonable doubt. E.g., collins v. Auger, 557 F.2d l-107,

1110 (5rh cir. L97B) , cerr. denied, 439 u. s. 1133 (1979) . These

arguments will be discussed inthe sections regarding circumstantial

evidence and impeachment Eestimony.

In Frady the Court did not consider error in the instruction

concerning the elements of the crime, prejudice per se. The

particular circumstances of each case must be considered and the

instruction must be vi-ewed in the context of the overall charge.

cupp v. Naughren, 4L4 u.s. L4L, L46-L47 (1973). Frady did nor

present any affirmative evidence of mitigating circumstances which

would tend to Prove lack of malice and thereby a killing from murder

to manslaughter. A1so, the evidence for the State was substantial

on the question of malice. A jury properly instructed would have

probably reached the same conclusion. In light of these considera-

tions the Court found the instruction resulted in no actual preju-

dice. rn Alabama the l{rit of Error coram Nobis provides post-

convicti.on relief i.n the state courts . A. R. c. p. 60. Generally the

motion is made in the court which rendered the judgment. rf the

motion is denied petitioner appeals to the next court. ',st.ate law

must be consulted to determine what types of claims attacking the

conviction and sentence may be raised in the post-conviction

proceedings available in a state. rn general, all matters that

might possibly warrant federal habeas corpus relief in the

case that were not clearly and exhaustively raised on appeal

-3-

from the conviction and sentence in the State courts must be

raised in some State post-conviction proceeding to assure that

the Federal exhaustion requirement has been met.t' Federal Habeas

Corpus Manual for Capital Cases, James Liebman, Vo1. 1, 1981 2d.

Edition, pC. 62. See, Johnson v. liilliams, 244 Ala. 391' 72 So.2d

683 (l-943) (adopts Writ of Error Coram Nobis into Alabama Procedure);

Grole v. State, 48 A1a. App. 709 (L972) (whether issues raised by

appellant are within purview of error coram nobis proceedings).

Initially, the writ !{as available to question procedural issues

other than the merits of the case, and to raise errors concerning

facts not known to court at the time of trial. Johnsgn, supra' at

394, 395. Alabarna case law since 1943 has narrowed the scoPe

of the wirt to correct rr*** an error of acts, one not appearing on

the face of the record, unknown to the Court or party affected, and,

which if known in time, would have prevented the judgment challenged,

and served as a motion for new trial on the ground of newly dis-

covered evidence." T111is v. State, 349 So.2d 95, 97 (A1a. App.

Le77).

Where a collateral attack in federal procedure will not do

service for failure to raise issues on direct aPpeal, Frady,

-Urg, the Writ of Error Coram Nobis will not provide rellef

where a petitioner had the opportunity to bring to the attentlon

of the Court the matter complained of but failed to do so.

Srrang v. United States,53 F.2d 820 (1931). In Lewis v. State,

367 So.2d 542 (A1a.Cr.App. 1978), writ. denied, Ala. 367 So.2d 547'

defense counsel pettitioned the trial court by Wirt of Error

Coram Nobis, asserting newly discovered evidence and ineffective

-4-

assistance of counsel as grounds for a new trlal. The writ was

denied for several reasons. First, the defendant I s failure

to remember the name of an alibi witness of the first trial and

his recollection of the name during second trial was considered

newly diselosed evidenee but not newly discovered evidence.

The writ was not intended to relieve a party of his own negligence.

Thornburg v. State, 42 A1a. App. 70, L52 So.2d 442 (1963).

Second, the alibi witness provided testimony that was only im-

peachi-ng in nature in that 1t cast doubt on part of testimony

of prosecutionfs witness placing the defendant near the scene

of the murder. with impeachment testirnony the jury can either

accePt or rej ect the new witness I s testimony and still convict

the defendanE. This fal1s short of the requirement that the newly

discovered evidence must be such as will probably change the

result if a ner,f trial is granted. Tucker v. state , 57 Ala. App. 15,

325 So.2d 531 (L975) , cert. denied, 295 Ala. 430, 325 So.2d 539

(L976). Probably means having more evidence for the defendant

than against. Lewis, supra at 545. other requireuents for the

newly discovered evidence include: 1) tfrat it has been diseovered

since the l'riaLi 2) that it could not have been dj-scovered before

trial; 3) that it is material to the issue. Finally, counsel was

not dound to be inadequate. Even though it can be shown that an

attorney has made a mistake i"n the trial of a case that result,s

in an unfavorable judgrnent, this alone is not sufficient to

demonstrate that his client has been deprived of his constitutional

right to adequate and effective representation by counsel. Lee

v. srare, 349 so.2d L34 (Ala.cr.App., Lg77). Even rhe failure of

-5-

counsel to make a closing argument has been held insufficient

to demonstrate inadequate representatlon because thj-s can be a

tactical m ve by counsel. Robinson v. State, 361 So.2d LL72

(Ala.Cr.App.; Behl v. State, 405 So.2d 51 (A1a.Cr.App. 1981)

An adequate defense in the context of a constitutional report

to counsel does not mean that counsel wil-1 not commit tactlcal

errors. Summer v. State, 366 So.2d 336, 341 (A1a. Cr. App. 1978).

Alabama case law on the l,rrrit of Error Coran Nobis embodies a stand-

ard governlng relief whereby the petltioner has a duty to establish

his right to reli-ef by "c1ear, ful1 and satisfactory proof."

Vincent v. State, 284 Ala. 242, 224 So.2d 60 (1969): "Clear"

is highl-y exactlng as to proof of facts and always means more than

"reasonably satisfying." Burden v. St,ate, 52 A1a. App. 348, 292

So.2d 463 (L974). The application of this standard seems com-

parable to the "cause and actual prejudice" standard set forth

ln Waj-nwright, supra. See, e.9., Summers v. State, 366 So.2d 336

(A1a. Cr. App.,1978); Hlshtower v. State,410 So.2d 442 (A1a.Cr.

App. 1981); Behl v. State, 405 So.2d 51 (A1a.Cr.App. 1981).

Consequently, any issues ralsed in the Writ of Error Coram Nobis

should be supported by a showing of cause and actual prejudice.

This memorandum will set out to establlsh those issues whlch will

most llkely survive the cause of actual prejudice test.

-6-

!,. I

€aCh dUh.o, U /1a/ /a/.i d4/ /4frr?>-tz4 tz-Coql, I'

-t/1 tt" t/. /d.l4b. or/t- /rrT.rrr ttutaf L-<

ry lnu?utd fu h stan- a74k

- P;-rr* stta cr, tu/ rtczulul,la^1 W ry u1o/<t "

4ru1 t/,4

P laun 1l r14 f/u Uttrl.Zlttn, t'

Y clt"/,/t qtcuy'tal$ ytu %J t/afi,+/ /' au,-

h *t- o/Q;nA n ,staa drrrr so ftqr ds /rr-( a /o.// t

P Wr//,t,4 /oat/4/21 h or*r<

W ba-ou fnd4/4ua t .t stnn- t, Fnuat fu- 't fl, tthslatf,<l

'1hxlofun nad hsr oNfu ffit<

flllofutl

dil* ,w b,rnazt/ra f.*"'h lL sa'nZ P&';

atlorui. h Hiprtrli.i fr Zi7osthry,

u, /ru*,* r |/r,a6fo n saffiqru@ /ralL

{t uiln c/dir,rr, , oq Nlw?*t-' ,**i ,,;4.'.rtrt llfiLl olaa*a r^

ry t fi*t"l 7uculrru7 , h* ,'ilril n dri/r,r,,*

@ ,*f{'t{, ct' yt'tuat?t-oi k,.,/ llrLn* k @-I

J4lauul

4( ttnluayruy {1thtat,,ruX t,furlruil drra,t,.* $ a dsr,,u, rur,*o/

eft aotn gL.*t, %N , ii*uuul ,fu^A Ott.orr/n /,,/,/vtu-/,A

, k,ot ,tu.afiy '/hr-/orna/ f,u1fat .ftt t- c/t.tr,* h

pteh- Ptt- b"uiddnlrw@. l)ur 4-4-s///u4 tld,k

|LiPLh tlr' *otd t an1$ ryyr>.(rl c(ou,'t;c u'cLl h-t-

,'+/no;t t f*i n;r*iy 0/",r.r,oL trt /&,trl fu/"/t/.

Drulr sty, W u,/t44,4

Prui,^

t/a" A./4 /X Ut4 to$t-t*a /.^

' l.

i

i

l

,,.4

,

I

Ctt

I

,WJt/4r/,utu;4 W Hlttu.

t U L , . , t t ^. /t -.