Gardner v. Florida Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gardner v. Florida Brief for Respondent, 1976. 02afe9c7-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ebf7da1a-cb0c-49f2-8b7a-2ddbb5b6f026/gardner-v-florida-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

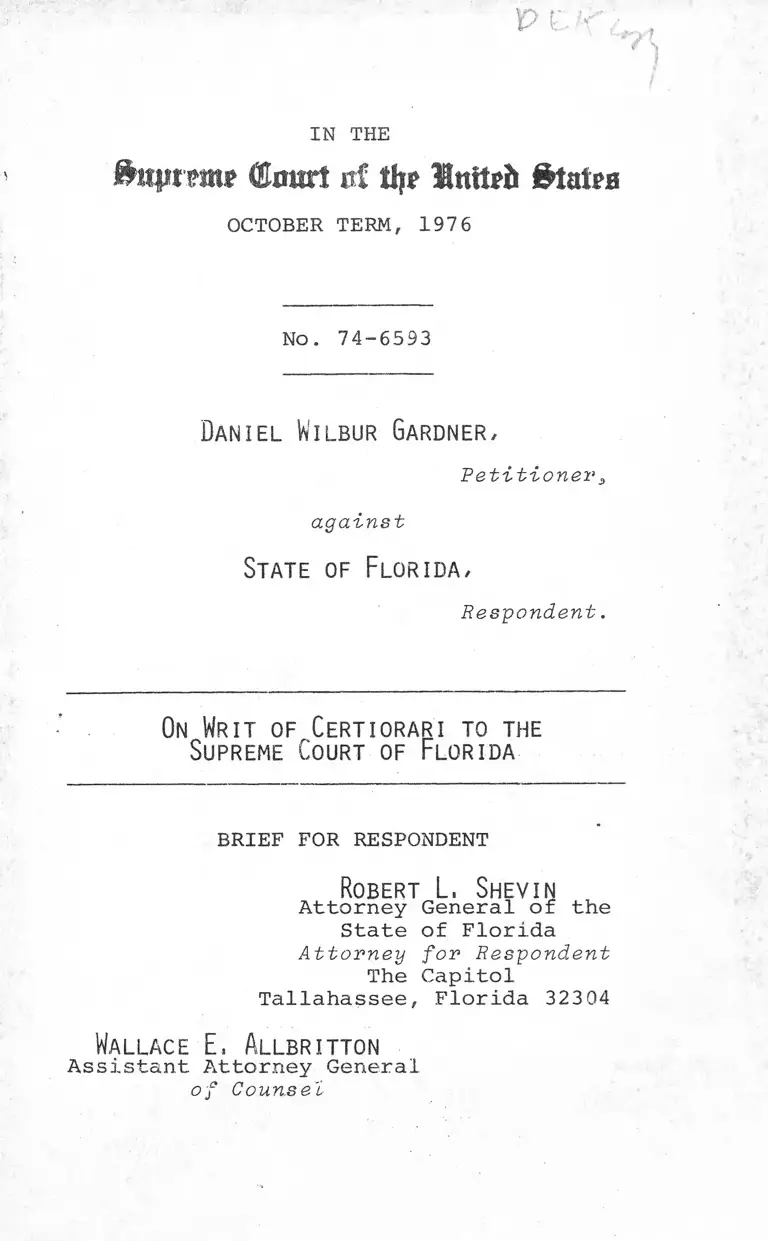

IN THE

P £.

f h q ir w it * € u s ir t it! tl|F I n t f r i i $ t a i e a

OCTOBER TERM, 1976

No. 74-6593

Daniel Wilbur Gardner,

Petitioner3

against

State of Florida,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Florida

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

Robert L. ShevinAttorney General of the

State of Florida

Attorney for Respondent

The Capitol

Tallahassee, Florida 32304

Wallace E, AllbrittonAssistant Attorney General

of Counsel

-x-

TOPICAL INDEX TO BRIEF

Preliminary Statement

Page

1,2

Opinion Below 2

Jurisdiction 2,3

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved 3,4

Question Presented 4

Statement of the Facts 5-19

Summary of Argument 19-22

Argument 23-55

Conclusion 55

-li-

Cases

Page

Baker v. United States, 388 F.2d

931 (4th Cir. 1968) 44

Hancock Brothers, Inc. v. Jones,

293 F.Supp. 1229 (D.C.N.D. Cal.

1968) 40

Hoover v. United States, 268 F.2d

787 (10th Cir. 1959) 41

Proffitt v. State of Florida,

_____U.S.____, 49 L .Ed.2d 913,

96 S.Ct._____ (1976) 48

Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605

(1967) 43

State v. Dixon, 283 So.2d 1 (Fla.

1973) 51

United States v. Durham, 181 F.Supp.

503 (D.D.C. I960) 39

United States v. Horsley, 519 F.2d

1264 (5th Cir. 1975) 47

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241

(1949) 34

Statutes

Page

Section 775.082, Florida Statutes 3

" 782.04, " " 3

" 921.141, " " 4

Rules

Fla.R.Cr.P. 3.710 4

Fla.R.Cr.P. 3.711 4

Fla.R.Cr.P. 3.712 4

Fla.R.Cr.P. 3,713 4

-iii-

~ 1 V ~

Other Authorities

Page

Guzman, Defendant's Access to Pre

sentence Reports in Federal

Criminal Courts, 52 Iowa L.Rev.

161 (1966) 26

Higgins, In Response to Roche, 29

Albany L .Rev. 225 (1965) 26

Higgins, Confidentiality of Pre

sentence Reports, 28 Albany L.

Rev. 12 (1964) 26

Hincks, In Opposition to Rule 34(c)

(2), Proposed Federal Rules of

Criminal Procedure, Fed.Prob.,

Oct.-Dec. 1944, p. 3 27

Lorensen, The Disclosure to Defense

of Presentence Reports in West

Virginia, 69 W.Va.L.Rev. 159

(1967) 26

Note, Right of Criminal Offenders

to Challenge Reports Used in

Determining Sentence, 49 Colum.

L.Rev. 567 (1949) 27

Parsons, The Presentence Investiga

tive Report Must be Preserved as

a Confidential Document, Fed.

Prob., March 1964, p. 3 26

Roche, The Position for Confiden

tiality of the Presentence

Investigation Report, 29 Albany

L.Rev. 206 26

- V -

Rubin, What Privacy for Presentence

Reports, Fed.Prob., Dec. 1952,

p. 8 27

Sharp, The Confidential Nature of

Presentence Reports, 5 Catholic

U.L.Rev. 127 (1955) 27

Symposium on Discovery in Federal

Criminal Cases, 33 F.R.D. 47,

122-28 (1963) 27

Thomsen, Confidentiality of the

Presentence Report: A Middle

Position, Fed.Prob., March 1964 26

IN THE

fciipran* ®0Mrt of % Itttlad fctafea

OCTOBER TERM, 1976

No. 74-6593

DANIEL WILBUR GARDNER,

P et-itionev 3

against

STATE OF FLORIDA,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Florida

Preliminary Statement

All references to the appendix will be

made by use of the prefix "A" followed by

appropriate page number. References to

the original transcript of trial testimony

2

will be made by use of the symbol "Tr."

followed by appropriate volume and page

number.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of

Florida affirming petitioner's conviction

of first degree murder and sentence of

death by electrocution is reported at

313 So.2d 675 (A 149-156). The findings

of fact made by the trial judge in support

of the imposition of the death sentence

and the judgment and sentence of the Cir

cuit Court of the Fifth Judicial Circuit

of Florida, in and for Citrus County, ad

judicating petitioner guilty and senten

cing him to death appear at A 138-140.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of

Florida was entered on February 26, 1975

3

(A 149). The petition for certiorari was

filed on May 24, 1975 and was granted on

July 6, 1976 (A 157). The jurisdiction

of this Court rests on 28 U.S.C. §1257 (3).

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved

This case involves the Sixth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States,

which provides:

"In all criminal prosecutions, the

accused shall enjoy the right...to

have the Assistance of Counsel for

his defence."

It also involves the Due Process Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

It further involves the following pro

visions of the statutes and rules of Crim

inal Procedure of the State of Florida.

Section 775.082, Florida Statutes,

1975.

Section 782.04, Florida Statutes,1975.

4

Section

1975

921.:141, Florida Statutes,

Florida

3.710.

Rule of Criminal Procedure

Florida

3.711.

Rule of Criminal Procedure

Florida

3.712.

Rule of Criminal Procedure

Florida

3.713

Rule of Criminal Procedure

Question Presented

Whether nondisclosure of a "con

fidential" portion of a presen

tence investigation report to a

defendant convicted of a capital

crime constitutes a denial of the

effective assistance of counsel

guaranteed by the Sixth and Four

teenth Amendments to the Constitu

tion of the United States, and of

the right to a fair hearing as

guaranteed by the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, in a case where the trial

judge declines to accept a jury

recommendation of a life sentence

and instead imposes the death sen

tence partially on the basis of

the presentence report?

5

Statement of the Facts

Glenda Mae Demney, presently residing

in Tampa, Florida, suffered a traumatic

experience on June 29, 30, 1973. On that

date, she was living in Homosassa, Florida.

She lived in a trailer right beside her

daughter, Bertha Mae Gardner, and her hus

band, petitioner, Daniel Wilbur Gardner

(R Vol.II, pp. 166, 167). Glenda Mae saw

her daughter around 7:00 o'clock on

June 29, 1973 (R Vol.II, p. 168). Later,

after dark, Glenda Mae and Bertha Mae

took Bertha Mae's children to the home of

Glenda Mae's youngest son. Glenda Mae

and Bertha Mae then went on to the Sugar

Mill, a local tavern. Glenda Mae let her

daughter out at the Sugar Mill and then

went back home (R Vol.II, pp. 169, 170).

Later Glenda Mae saw Bertha again when

Bertha came to her trailer and said she was

6

out of cigarettes. This was about 10 or

10:30 p.m., and Bertha remarked that she

was going to look for her husband, peti

tioner Gardner. As far as Glenda Mae

knew Bertha had not had anything of an

p/. '

alcoholic nature to drink (R Vol.II,

p. 171). On that particular evening,

Glenda Mae was keeping company with Cal

vin Loenacker, more popularly known as

Buckshot. Later in the evening or per

haps in the early morning hours, Glenda

Mae and Buckshot were in her trailer.

She was fixing her lunch for the next

morning and sipping along on a beer. All

of a sudden, the door, hinges and all,

came off and her son-in-law, Daniel Wil

bur Gardner petitioner was behind it. He

hit Glenda Mae on the side of the face,

and she was knocked out (R Vol.II, p. 172).

The next morning, Glenda Mae was fixing

7

some coffee when her son-in-law came over

again and said that her daughter, Bertha

Mae, wasn’t breathing right (R Vol.II, p .

174). Glenda Mae went next door and saw

her daughter naked on a bed with bruises

on her face. Glenda Mae didn,' t know if

Bertha was unconscious or not. But as

far as she could determine, her son-in-

law was not drinking that morning and he

did not appear to be intoxicated. She

stated that he had been drinking the night

before when he came to her trailer and

struck her but he was not drunk (R Vol.II,

pp. 175, 176). No question about it,

Glenda Mae flatly denied a contention

that her son-in-law came to her house,

knocked on the door and inquired about

the whereabouts of his children. Glenda

Mae further denied that she slammed the

door in her son-in-law's face, that he

8

then kicked the door and it flew open

and hit her and knocked her down (R Vol.

II, p. 182). Glenda Mae remarked again

that her son-in-law knocked her out with

his fist and kicked her in the end of her

spine "and the door didn't do that."

(R Vol.II, p. 183).

Alva Loenecker was a commercial fisher

man and long time friend of petitioner

Gardner and his wife (R Vol.II, p. 185).

He was at Glenda Mae's house on June 29,

1973 drinking some whiskey. At about 11

or 11:30 p.m., petitioner Gardner came

over, drug the door off the trailer, came

in and hit Glenda- Mae and knocked her out

on the floor (R Vol.II, p. 186). Buck

shot asked him not to do that any more.

Petitioner Gardner remarked that he was

going back and beat hell out of his wife.

Buckshot saw Bertha Mae at the door of

9

her trailer, and then gesturing, said

that petitioner was pulling her head down

at which time Bertha said, "please don't

hit me any more." (R Vol.II, p. 187)

Approximately 35 minutes later, petitioner

Gardner returned to the trailer where

Glenda Mae and Buckshot were. Petitioner

wanted to jump on Glenda Mae again but

Buckshot apparently talked him out of it.

Nothing was mentioned concerning the where

abouts of petitioner's children (R Vol.II,

p. 188). The next morning, petitioner

came to the trailer, called Buckshot and

said something was wrong with his wife,

Bertha Mae (R Vol.II, p. 189). Glenda

Mae got up and she and Buckshot went to

petitioner's trailer. On entering the

trailer, Buckshot saw Bertha Mae and

petitioner remarked that he couldn't

understand why his wife didn't wake up.

10

Buckshot said that Bertha Mae looked like

she was dead. Petitioner asked him to go

call the ambulance (R Vol.II, p. 190).

Nellie Merkerson is the mother of peti

tioner. She saw Buckshot on the morning

of June 30, 1973 and as a result went to

the trailer where her son and his wife

were living (R Vol.II, p. 196). On

arrival at the trailer, she asked her

son what had he done, and he denied hav

ing done anything at all (R Vol.II, p.

197). After this, Nellie went back to

her house, called her daughter-in-law

and asked her to call the ambulance.

Nellie then returned to her son's trailer

and when she saw what had happened and

asked her son about it, he said, "She

wouldn't tell me where my babies are and

I tried to get her to tell me and she

wouldn't so I kept on beating her."

11

(R Vol.II, pp. 198, 199)

David Merkerson is the half-brother of

petitioner (R Vol.II, p. 200). David lived

about 150 feet from the trailer where peti

tioner and his wife lived. He went to

their trailer on the morning of June 30,

1973. His mother, Nellie Merkerson, his

wife Susan, and Bertha's mother, Glenda

Mae, were there (R Vol.III, p. 201).

Buckshot was outside. When David Merker

son saw Bertha Mae, she was on the bed

and "she was dead." A sheet had been

pulled up all the way to her neck (R Vol.

II, p. 202). David was present when peti

tioner was placed in the patrol car (R Vol.

III, p. 203). At that time, petitioner

remarked to him, "Dave, I guess I really

did it this time." David answered, "Yes,

I guess you did." (R Vol.III, p. 204)

12

Susan Markerson is the aunt of peti

tioner. She lived less than one-half

block from where petitioner and his wife

lived. Her rest was disturbed at approx

imately 11:30 p.m. on June 29, 1973 when

she was awakened by noises emanating from

petitioner's trailer which sounded like

someone was bumping or moving furniture

around (R Vol.III, p. 206).

Walter Owezarek is an emergency medical

technician and on the morning of June 30,

1973 went to the residence of Daniel Wil

bur Gardner and Bertha Mae Gardner (R Vol.

Ill, p. 207). Upon arrival, Walter asked

where the patient was (R Vol.III, p. 208).

Petitioner pointed to a room. Walter saw

a woman lying on a bed and examined her

but found no vital signs. He looked at

her entire body and saw a gigantic hematosa

in the pelvic area (R Vol.III, pp. 209, 210).

13

The woman had been so badly bruised that

Walter inquired from the petitioner as to

now it happened. Petitioner remarked that

his wife probably went out and got some

drugs and when she came back she told peti

tioner to hit her and that he constantly >.j/ u

kept pounding on her. When Walter heard

this, he called the Sheriff's Department

and they all stood by and waited for the

officers to arrive (R Vol.III, p. 211).

Later after receiving permission from the

law enforcement officers, Walter and the

ambulance driver removed the body to the

Citrus Memorial Hospital (R Vol.III, p.

215) .

Lloyd Shelton had been employed as a

deputy sheriff of Citrus County, Florida,

for approximately 8-1/2 years. On

June 30, 1973, he had occasion to go to

the residence of petitioner Gardner at

14

approximately 7:00 a.m. (R Vol.Ill, p.

216). He had known petitioner and his

wife prior to this occasion (R Vol.Ill,

p. 217). When he looked at the nude body

which had been beaten and bruised, there

wasn't any sign of life. He touched the

leg just below the knee, and it was cold.

He radioed the sheriff's office to send

Deputy Williams and for them to call Mr.

Green to come to the scene (R Vol.Ill,

p. 218). Deputy Shelton took a lot of

photographs inside the premises (R Vol.

Ill, p. 219). Deputy Shelton turned all

the evidence over to Deputy George Han-

stein (R Vol.Ill, pp. 230, 231). Later

when Deputy Shelton arrested petitioner,

he advised him of his constitutional

rights, commonly known as Miranda warn

ings (R Vol.Ill, p. 239). After Deputy

Shelton put petitioner in the car and they

15

were driving along, petitioner remarked,

"Why would a man do something like that"

--"why would I do something like that,"

Petitioner also commented that his wife

had been running around with other people

and "that thing has been eating on me,-—

it was just more than I could stand."

(R Vol.III, p. 240) Petitioner gave a

statement to Deputy Shelton and basically

in the statement said that he and his wife

got into a fuss after they got home and

he beat her. Then she got up and took a -

bath and when she came back to bed, he

beat her some more. And then he went to

sleep and didn't wake up until the next-

morning (R Vol.III, p. 243).

David Chancey first saw the body of

Bertha Mae at the Citrus Memorial Hospi

tal. He took the body from Citrus Mem

orial to the Leesburg General Hospital.

16

No one was with him when he transported

the body (R Vol.III, pp. 244, 245). He

identified a photograph of the body

(State's Exhibit No. 6) as being a photo

graph of the body he transported.

George Hanstein was a deputy sheriff

in Citrus County, Florida. He received

three packages from Deputy Shelton which

he initialled and processed them for

turning over to the Florida Crime Lab in

Sanford, Florida. Counsel for the res

pective parties stipulated to this fact

(R Vol.III, pp. 249, 250).

Dr. William H. Shutze is a medical

doctor specializing in pathology. Coun

sel for petitioner at trial had no objec

tion to his qualification as a patholo

gist licensed to practice in the State of

Florida (R Vol.III, pp. 252, 253). Dr.

Shutze identified State's Exhibit No. 6

17

as being a photograph of a body upon which

he performed an autopsy on July 2, 1973 at

the Leesburg General Hospital. He ascer

tained that the name of the body of the

deceased was Bertha Mae Gardner. This

was done from a name tag on the body (R

Vol.III, p. 255). Dr. Shutze described

the condition of the body and stated that

there were at least 100 bruises thereon

(R Vol.III, p. 256). And as a result of

one injury, it was his opinion that some

thing like a broomstick, bat, or bottle

had been placed in the vagina (R Vol.III,

p. 257). Dr. Shutze estimated that the

wounds were perpetrated upon the body of

the deceased by combination of instrument,

fists, stomping, and rolling on the floor

(R Vol.III, p. 258). The cause of death

was a result of a combination of a loss

of blood from a large tear in the liver

18

and from the fracture of the pubic bone

(R Vol.Ill, p. 259). He estimated that

the deceased weighed 90 pounds (R Vol.

Ill, p. 260). On examining the body of

the deceased, it was determined that

large patches of hair were missing that

were not of a diseased nature. Rather,

the hair loss resulted from same being

pulled out (R Vol.Ill, p. 261). When

counsel for petitioner questioned Dr.

Shutze, there was quite a hassle over

the identity of the body upon which the

doctor performed the autopsy. In fact,

counsel for petitioner moved to strike

all of the doctor's testimony because he

could not positively identify the body

upon which he performed the autopsy as

being the body of Bertha Mae Garnder

(R Vol.Ill, pp. 262-264). A blood alco

hol test was performed with a result of

19

.19 grams percent which Dr. Shutze inter

preted as indicating mild tc moderate in

toxication (R Vol.III, p. 267).

Chandler Smith worked in the Sanford

Crime Lab as a criminalist examiner (R

Vol.III, pp. 268, 269). He was qualified

as an expert without objection. He tes

tified as to tests performed by him upon

certain exhibits and the results thereof

(R Vol.III, pp. 270-275).

The petitioner, Daniel Wilbur Gardner,

did not take the stand to testify in his

own behalf. (A 27-84)

Summary of Argument

Petitioner received a fair trial, and

the exercise of a reasoned discretion

by the trial judge in the sentencing pro

ceeding does not violate the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Fail

20

ure to disclose a confidential portion of

the presentence report did not deny peti

tioner the effective assistance of coun

sel nor deny him a fair hearing as guar

anteed by the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

First, for an investigator to get in

formation, especially of an intimate na

ture, he must be able to give a firm

assurance of confidentiality. Mandatory

disclosure would immediately dry up sources

of information that would otherwise be

available to an investigator. People do

not want to get involved. When they learn

that the supplying of information can

result in having to go to court or a neigh

borhood feud, they will no longer share

their knowledge and impressions.

Secondly, mandatory disclosure would

interminably delay the proceedings. A

21

defendant would, and understandably so,

challenge everything in the report, thus

transforming the sentencing process into

a much more lengthy affair then it has to

• If a. court must permit controversy

with resultant hearings over each part of

a presentence report, this would defeat

the very purpose of the report by extend

ing the process to such an extent that it

would no longer be a practical tool for

the aid of the court in the sentencing

process.

Thirdly, mandatory disclosure of parts

of the presentence report would be harm

ful to the rehabilitative efforts of a 4*, y

defendant. For example, a psychiatrist

would hardly reveal his complete diagnosis

of a patient at the beginning of their

relationship. Similarly, and particularly

if a defendant is to be supervised on pro-

22

bation by the same officer who compiled

the report, it can impede the defendant's

progress from the beginning if complete

disclosure is made.

Finnally, it is not unfair to a defen

dant to proceed against him in this man

ner. There is no longer the scrupulous

need for trial-type hearings with full

disclosure and confrontation that properly

governs a guilt-innocence determination.

The reasoned exercise of discretion by

the trial judge in evaluating the confi

dential portion of a presentence report

can be trusted and constitutes an ade

quate safeguard of the interests of both

the defendant and society.

23

Argument

A, The sentencing proceedings

MET THE REQUIREMENTS OF DUE

PROCESS AND PETITIONER RE

CEIVED THE EFFECTIVE ASSIS

TANCE OF COUNSEL.

Sub judice, the Findings of Fact sub-

mitted by the trial judge (A 138) in sup

port of the death sentence proves conclu

sively that no mitigating circumstances

were ignored. A separate and plenary

hearing was conducted on the penalty

issue as required by Section 921.141(1),

Florida Statutes. The jury was correctly

instructed as to their duty in this

second phase of the trial (A 121), and

then the trial judge reread the entire

jury instructions to them (A 124). Peti

tioner made no request for any additional

instructions or for any corrections to be

made to the instructions as given in this

24

phase of the trial (A 125, 126). Peti

tioner was given ample opportunity to pre

sent anything he desired for considera

tion by the jury as a mitigating circum

stance. No request was made for the sen

tencing phase to be continued for the

purpose of securing mitigating testimony.

Petitioner did not argue in his brief

filed in the court below that other miti

gating testimony should have been presen

ted to the jury (and the judge) but that

he was unable to do so because of lack of

time.

The record shows that the jury returned

its verdict of guilt on January 10, 1974

(A 106). The second phase or sentencing

proceeding was immediately begun and the

jury's Advisory Sentence was returned on

the same date, January 10, 1974 (A 126).

However, the trial judge's Findings of

25

Fact were not filed until January 30,

1974, and the death sentence was imposed

on the same day (A 138-140). Simple arith

metic shows that the trial judge had a

period of twenty days within which to

mull over, cogitate on, consider, and

weigh all of the testimony adduced at the

trial and at the sentencing proceeding.

Certainly, it cannot be successfully urged

that the trial judge was in any haste or

in any way eager to impose the death pen

alty. Rather, this was done after an

ample period of reflection and considera

tion of everything that had transpired

and should not be disturbed by this Court.

B, Petitioner was not denied a

FAIR HEARING OR THE EFFECTIVE

ASSISTANCE OF COUNSEL BECAUSE

OF NONDISCLOSURE OF THE FULL

PRESENTENCE REPORT.

It must be admitted that the question

26

of disclosure vel non of the presentence

report to parties has generated much heated

debate in the literature. See, e.g.,

Lorensen, The Disclosure to Defense of

Presentence Reports in West Virginia,

69 W.Va.L.Rev. 159 (1967); Guzman, Defen

dant 's Access to Presentence Reports in

Federal Criminal Courts, 52 Iowa L.Rev.

161 (1966); Roche, The position for Con

fidentiality of the Presentence Investiga

tion Report, 29 Albany L.Rev. 206; Higgins,

In Response to Roche, 29 Albany L. Rev.

225 (1965); Higgins, Confidentiality of

Presentence Reports, 28 Albany L. Rev. 12

(1964); Parsons, The Pre-sentence Investi

gative Report Must be Preserved as a Con

fidential Document, Fed.Prob., March 1964,

p. 3; Thomsen, Confidentiality of the Pre

sentence Report: A Middle Position, Fed.

Prob., March 1964, p. 8; Symposium on Dis

27

covery in Federal Criminal Cases, 33 F .R.D

47, 122-28 (1963); Sharp, The Confidential

Nature of Presentence Reports, 5 Catholic

U.L. Rev. 127 (1955); Rubin, What Privacy

for Presentence Reports, Fed. Prob., Dec.

1952, p. 8; Note, Right of Criminal Offen

ders to Challenge Reports Used in Deter

mining Sentence, 49 Colum.L.Rev. 567

(1949); Hincks, In Opposition to Rule 34(c)

(2), Proposed Federal Rules of Criminal

Procedure, Fed.Prob., Oct.-Dec. 1944,

p. 3. There is also a division among

statutes on the point. Most maintain a

position of silence which is usually inter

preted as placing disclosure within the

discretion of the sentencing court.

Illustrative of this position is Florida

Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.713(a) pro

viding that the trial judge "may disclose"

any of the contents of the presentence

2 8

investigation. It is emphasized that

there have been numerous proposals in an

effort to draw an acceptable line of de

marcation between complete disclosure

and complete secrecy. The President's

Crime Commission recommended, for example,

that "in the absence of compelling reasons

for nondisclosure of special information,

the defendant and his counsel should be

permitted to examine the entire presen

tence report." President's Comm'n, The

Challenge of Crime 145. See also Presi

dent's Comm'n, The Courts 20. Other pro

posals have often proceeded from the view

that what the defendant needs is not the

whole report, but merely the facts on

which it is based. Sources of informa

tion, together with opinions of the pro

bation officer, properly can remain a

privileged communication between officer

29

and judge. See, e.g.3 Higgins, Confiden

tiality of Presentenoe Reports3 28 Albany

L.Rev. 12 (1964). There are real advantages

in a truly confidential report immune from

disclosure to the defendant or his counsel.

A presentence report, being designed as an

aid to the judge, will contain an intimate

character sketch of the defendant. In the

State of Florida where the reports, at

least parts thereof, have been held con

fidential, they have attained a quality

which makes them far more reliable and

hence more useful to the judge. No one

will deny that in formulating a sentence,

a judge needs as accurate an estimate as

possible of the character of the defen

dant. The best source of information on

a man's life is his family, if he has one.

If the investigating officer can tell the

members of the family that any information

30

they give will be held confidential, the

chances are he can get a more accurate

picture of the defendant's family life

for his report. But if the defendant

has been a bad provider and a bad influ

ence on the children, in many cases, the

wife will understandably hesitate to dis

close the information if she knows that

it will subsequently be brought to her

husband's attention.

Another very useful source of informa

tion includes the defendant's employers.

If employers, as a result of full disclo

sure of the presentence reports, learn

that their cooperation in disclosing in

formation to the investigating officer

will result in subpoenas to appear and

testify on contested issues at hearings

on a sentence, this Court can believe

that their cooperative attitude will soon

31

be destroyed. The net result will be

that a valuable source of information

about the defendant no longer will be

available for the presentence report as

an aid to the judge in formulating a

sentence.

Then, too, the requirement of disclo

sure seems particularly unfortunate when

a defendant is a gangster with dangerous

associates. It is neither fair nor sensi

ble for any person who can give useful

information on the character of such

defendants to be subjected to the hazard

of retaliation which well may flow from

the disclosure of confidential data.

Frequently, presentence reports will

include testimony from neighbors and mem

bers of the community. Such information

constitutes hearsay and there is perhaps

a certain minimal degree of logic in say-

32

ing the considerations of fairness require

that the defendant be given an opportunity

to dispute and cross examine any unfavor

able testimony gathered by the investiga

tor. But it is the position of respon

dent that the character and official posi

tion of the investigating officer is a

better guaranty against unfair prejudice

than the opportunity for partisan coun

sel to verify and cross examine. Proba

tion officers in the preparation of pre

sentence reports are on the alert to dis

card or discount character evidence moti

vated by spite or prejudice. Unreliable

testimony is either wholly excluded or,

if included, accompanied by sufficient

warning to put the judge on notice. In

this way, the judge has the benefit of

information apparently trustworthy and

can make his own estimate of the reliabil-

33

ity of questionable information, just as

well as though the objection were raised

by defense counsel.

Should this Court determine that full

disclosure is constitutionally required,

then it can look forward to delays in the

imposition of sentence in the trial courts.

This is so because defense counsel can

urge, and properly so, that the only rea

son for the rule was to afford opportunity

for an independent investigation of cer

tain material found therein and can then

protest in all sincerity that their pres

sing trial engagements will prevent them

from promptly undertaking the investiga

tion of the subject matter. And the trial

judge will be saddled with an added

dilemma: He will be accused of frustrating

the rule of disclosure unless he affords

defense counsel reasonable opportunity to

34

verify the report without interference with

his court assignments elsewhere. The inevit

able result is that the offender whose law

yer is most in demand will have the greater

success in delaying the day of sentence.

Respondent's constitutional contention

is simply stated: The Sixth and Fourteenth

Amendments do not forbid the imposition of

a death sentence after consideration of

confidential matters in a presentence re

port that have not been disclosed to the

parties. The decision of this Court in

Williams v. New York3 337 U.S. 241 (1949),

has long been recognized as the complete

and final word in support of nondisclo

sure. In Williams, this Court reviewed

a decision of the New York Court of Appeals

and by a majority opinion upheld a convic

tion of first degree murder. The jury

had recommended life imprisonment for the

35

slaying of a young girl in Brooklyn. The

trial judge, relying upon a probation inves

tigation report as a basis for ignoring the

jury recommendation, imposed the death pen

alty. This Court held that the trial judge

had full power to rely upon a probation

investigation report and this notwithstand

ing the defendant's contention that his

constitutional rights had been violated

because he had not had access to the re

port and the right to confrontation and

rebuttal. This Court pointedly remarked

that the imposition of the death sentence

would not alter the principles of nondis

closure, remarking that:

"We cannot say that the due process

clause renders a sentence void merely

because a judge gets additional out-of-

court information to assist him in this

awesome power of imposing the death

sentence." Id. at 252.

36

The opinion of this Court authored by

Mr. Justice Black contains many noteworthy

statements expounding the philosophy of

probation acceptable to this Court which

is appropriately related to an understand

ing and appreciation of the issue at hand.

This Court recognized that Williams pre

sented serious and difficult questions as

to the constitutional rights of a defen

dant at sentencing as well as the rules

of evidence applicable to the manner in

which a judge might obtain information to

assist him in the disposition of a con

victed offender. Following references to

the need of rigid rules of evidence in a

trial to determine the issue of guilt,

the court then significantly pointed out:

"A sentencing judge, however, is not

confined to the narrow issue of guilt.

His task within fixed statutory and

constitutional limits is to determine

the type and extent of punishment

37

after the issue of guilt has been

determined„ High! relevant— if

not essential--to his selection of

an appropriate sentence is the pos

session of the fullest information

possible concerning the defendant's

life and characteristics. And

modern concepts individualizing

punishment have made it all the more

necessary that the sentencing judge

not be denied an opportunity to ob

tain pertinent information by a re

quirement of rigid adherence to

restrictive rules of evidence proper

ly applicable to the trial."

Id. at 247.

The Court then made appropriate references

to the modern changes in the treatment of

offenders which make it more necessary

than in years past for observation of the

distinctions in the evidential procedure

in the trial and sentencing process. The

expanding use of the indeterminate sen

tence, and of probation itself, are ex

amples of procedures resulting in an in

crease in the discretionary powers employed

in determing punishment. The Court then

38

indicated its appreciation of the fact

that such procedures give rise to the

need for the fullest information possible

concerning the defendant's life and char

acteristics as an aid in the selection of

the most appropriate sentence. The Court

noted that:

"The considerations we have set

out admonish us against treating

the due process clause as a uni

form command that courts through

out the Nation abandon their age-

old practice of seeking informa

tion from out-of-court sources to

guide their judgment toward a more

enlightened and just sentence....

The due process clause should not

he treated as a device for freez

ing the evidential procedure of

sentencing in the mold of trial

procedure. So to treat the due

process clause would hinder--if

not preclude--all c o u r t s s t a t e

and federal, from making progres

sive efforts to improve the ad

ministration of criminal justice. "

(Emphasis supplied.) Id. at 250.

It may be argued that the decision in

Williams did not go to the crux of the

39

matter of determining whether or not a

defendant has a right to examine the

presentence report. This argument ignores

what the decision in Williams represents.

It unmistakably represents that the use

of confidential information by a trial

judge in the imposition of a death sen

tence violates no constitutional right of

a defendant.

If the decision of this Court in

Williams is distasteful to the propon

ents of full disclosure, then surely the

decision of Judge Holtzoff in United

States v. Durham, 181 F.Supp. 503 (D.D.C.

1960), cert, denied 364 U.S. 854 (1960),

will be even less palatable to them.

"It is not the practice to per

mit the defendant or his counsel

or anyone else to inspect reports

of presentence investigations.

Such reports are treated as con

fidential documents.... In fact,

it has been the traditional prac-

40

tice even before the system of

presentence investigation was

introduced for the court to re

ceive information in confidence,

which the court might or might

not disclose to the defendant,

as the court saw fit, that

might bear upon the question of

what sentence should be imposed.

The custom of treating reports

as confidential documents is

merely a continuation of that

prior practice." Id. at 503,

504.

The basis of Judge Holtzoff's decision

was, of course, this Court's decision

in Williams. See Footnote 1 appended to

the Durham decision.

Eight years later in 1968, Judge Car

ter in Hancock Brothers, Inc. v. Jones,

293 F.Supp. 1229 (D.C.N.D. Cal. 1968),

held that presentencing memoranda pre

pared in connection with sentencing of

defendants in a criminal proceeding

under the Clayton Act should not be made

a matter of public record and disclosure

41

would not be compelled. Note the follow-

ing:

"If the confidential nature of a

probation report is not protected,

a serious curtailment could result

in information now made available

to sentencing judges. Hoover v.

United States, 268 F .2d 787 (10th

Cir. 1959); United States v. Dur

ham, 181 F .Supp. 503 (D.C. 1960) ,

cert. den. 364 U.S. 854, 81 S.Ct.

83, 5 L.Ed. 77 (1960); United

States v. Greathouse, 188 F .Supp.

765 (Ala. 1960); Dillon v. United

States, 307 F.2d 445 (9th Cir.

1962) (Barnes, J., dissenting;

Barnet and Gronewold, Confiden

tiality of the Pre-sentence Report,

26 Fed.Prob. 26 (1962). 'To de

prive sentencing judges of this

kind of information would under

mine modern penalogical procedural

policies that have been cautiously

adopted throughout the nation after

careful consideration and experimen

tation. ' Williams v. People of

State of New York, 337 U.S. 241,

249-250, 69 S.Ct. 1079, 1084, 93

L.Ed. 1337 (1949)." Id. at 1232,

1233.

In the case of Hoover v. United States,

268 F .2d 787 (10th Cir. 1959), the sen

tence was attacked on the ground that the

42

presentence report contained many inaccur

ate and untrue statements and that the defen

dant was given no opportunity to contra

dict or rebut them. In disposing of this

attack, Chief Judge Bratton, writing for

a unanimous court, commented as follows:

"One further challenge to the judg

ment and sentence was that the pro

bation service made a presentence

investigation and report in the case;

that the report contained many in

accurate, untrue, and prejudicial

statements; that it was an ex parte

investigation; that appellant was

not given any opportunity to con

tradict or rebut the inaccurate,

untrue, and prejudicial statements;

that they prejudiced the court

against appellant; and that in

such manner he was denied due pro

cess. Rule of Criminal Procedure

32(c)(1), 18 U.S.C., provides that

the probation service of the court

shall make a presentence investiga

tion and report to the court before

the imposition of sentence or the

granting of probation unless the

court directs otherwise; and Rule

32(c) (2) provides in presently

pertinent part that the presentence

investigation shall contain such

information concerning the circum

stances affecting the behavior of

43

the defendant as may be helpful

in imposing sentence. The pre

sentence investigation was made

and the report submitted pursuant

to the rule. And the action of

the court in taking into consider

ation and giving appropriate weight

to the information obtained in that

manner in determining the kind and

extent of punishment to be imposed

upon appellant within the limits

fixed by law, without affording

appellant an opportunity to con

tradict or rebut statements con

tained in the report, did not

violate due process. Williams v.

People of State of New York, 337

U.S. 241, 69 S.Ct. 1079, 93 L.Ed.

1337." Id. at 790.

In the case of Specht v. Patterson,

386 U.S. 605 (1967), this Court had an

opportunity to repudiate its holding in

Williams but declined to do so. In

Speoht, this Court condemned the proced

ure followed by a Colorado state court in

sentencing the defendant under the Color

ado Sex Offenders' Act to an indetermin

ate term of from one day to life. The

defendant Specht was afforded no hearing

44

or right of confrontation for the pur

pose of determining the validity of the

conclusions stated in the reports of the

psychiatrists. This Court held that the

failure to grant such procedural safe

guards as a hearing and the right of con

frontation violated the due process require

ments of the Fourteenth Amendment. In

determining the applicability of Williams,

this Court remarked as follows:

"We adhere to Williams v. New York,

supra; but we decline the invita

tion to extend it to this radically

different situation." Id. at 329.

The decision in Baker v. United States,

388 F .2d 931 (4th Cir. 1968), is informa

tive. Although there, the sentence was

vacated and the cause remanded because of

the unusual factual situation, the comments

of the Court on the issue of nondisclosure

are interesting. Note the following:

45

"Fixed practices aside, we must

observe that there is no obliga

tion upon the Court to divulge,

or any right in the defendant to

see, the entire report at any

time. See Williams v. State of

Oklahoma, 358 U.S. 576, 79 S.Ct.

421, 3 L .Ed.2d 516 (1959); Williams

v. People of State of New York, 337

U.S. 241, 69 S.Ct. 1079, 93 L.Ed.

1337 (1949); F.R.Crim.P. 32(c)(2),

supra. Indeed, there could be dan

ger in delivering it to the defen

dant or his attorney for scrutiny.

It could defeat the object of the

report— to acquaint the court with

the defendant's background as a

sentencing guide--by drying up

the source of such information.

See United States v. Fischer, 381

F .2d 509 (2 Cir. July 24, 1967).

To illustrate, the probation offi

cer could be deprived of the con

fidence of trustworthy and logical

informants--persons close to the

accused--if they knew they could

be confronted by the defendant

with their statements. The inves

tigation would then amount to no

more than a repetition of the pub

lic records--so limited a function

as to obviate the need of a proba

tion officer.

* * *

46

"Of course, the defendant's gen

eral conduct and behavior, as well

as his reputation in the community

in regard to honesty, rectitude

and fulfillment of his civic and

domestic responsibilities, may be

treated in the report. Whether

any of such commentary should be

released will remain in the discre

tion of the District Judge. Names

of informants, as well as intimate

observations readily traceable by

the defendant, ordinarily should

be withheld lest, to repeat, dis

closure cut off the investigator

from access to knowledge highly

valuable to the sentencing court.

It is to be expected of the judge,

however, that he winnow substance

from gossip." Id. at 933, 934.

As recently as 1975, the Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals had occasion to pass

on the disclosure issue. There the appel

lants contended that the District Court

erred in denying them access to presen

tence reports. The record did not dis

close what, if any, information in the

reports was relied upon by the trial

judge. However, appellants urged that

the nondisclosure was significant in light

47

of the disparity of sentences imposed on

the two defendants. In rejecting this

argument, the Fifth Circuit in United

States v , Horsley3 519 F .2d 1264 (5th Cir.

1975), remarked as follows:

"This Circuit has repeatedly held

that the decision whether or not

to disclose part or all of a pre

sentence report submitted pursuant

to Federal Rule of Criminal Proce

dure 32(c)(2) lies within the dis

cretion of the trial judge. United

States v. Arenas-Granada, 5 Cir.,

1973, 487 F .2d 858, 859 (per cur

iam) ; United States v. Thomas, 5

Cir., 1970, 435 F.2d 1303 (per cur

iam) ; United States v. Chapman, 5

Cir., 1969, 420 F.2d 925, 926,* Good

v. United States, 5 Cir., 1969, 410

F .2d 1217, 1221; United States v.

Bakewell, 5 Cir., 1970, 430 F.2d

721, 722 (per curiam). We have also

held that even where some errors

in the presentenee report have

come to light and been corrected,

the trial judge may properly re

fuse to disclose the remainder of

the report to the defendant for

purposes of ascertaining whether

further mistakes have been made.

United States v. Jones, 5 Cir.,

1973, 473 F.2d 293, cert, denied,

411 U.S. 934, 93 S.Ct. 2280, 36

L.Ed.2d 961."

* * *

48

"The leading Supreme Court case

regarding access to presentence

reports, Williams v. New York,

337 U.S. 241, 69 S.Ct. 1079, 93

L.Ed. 1337 (1949), has not been

overruled. In Williams, the Court

sustained a death sentence imposed

on the basis of a presentence re

port, despite a jury recommendation

of a life sentence. The Court held

that the due process clause does

not require that a sentence be

based on information received in

open court, noting that much of

the information relied upon by

judges in presentence reports would

be unavailable if it were restricted

to that given in open court by wit

nesses subject to cross-examination."

Id. at 1266, 1267.

The use of a presentence report is an

integral part of Florida's sentencing

procedure. In Proffitt v. State of

Florida, ____U.S._____ , 49 L.Ed.2d 913,

96 S.Ct.______ (1976), this Court put its

unmistakable stamp of approval on Florida's

capital-sentencing procedures.

"The Florida capital-sentencing

procedures thus seek to assure

that the death penalty will not

be imposed in an arbitrary or

49

capricious manner. Moreover, to

the extent that any risk to the

contrary exists, it is minimized

by Florida's appellate review sys

tem, under which the evidence of

the aggravating and mitigating cir

cumstances is reviewed and reweighed

by the Supreme Court of Florida ' to

determine independently whether the

imposition of the ultimate penalty

is warranted.' Songer v State, 322

So 2d 481, 484 (1975). See also

Sullivan v. State, 303 So 2d 632,

637 (1974). The Supreme Court of

Florida, like that of Georgia, has

not hesitated to vacate a death

sentence when it has determined

that the sentence should not have

been imposed. Indeed, it has

vacated eight of the 21 death sen

tences that it has reviewed to date.

See Taylor v State, 294 So 2d 648

(1974); LaMadline v. State, 303 So

2d 17 (1974); Slater v State, 316

So 2d 539 (1974); Swan v State, 322

So 2d 485 (1975); Tedder v State,

322 So 2d 908 (1975); Halliwell v.

State, 323 So 2d 557 (1975); Thomp

son v State, 328 So 2d 1 (1976);

Messer v State, 330 So 2d 137 (1976)."

Id. at 49 L .Ed.2d 913 at 923.

Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure

3.713 is remarkably similar to Federal

Rule of Criminal Procedure 32 (c) (3).

Subsection (a) of the Florida rule pro

vides :

50

"The trial judge may disclose any

of the contents of the presentence

investigation to the parties prior

to sentencing. Any information so

disclosed to one party shall be dis

closed to the opposing party."

See also Subsections (b) and (c). The

federal rule at Subsection (c)(3)(A) pro

vides :

" (A) Before imposing sentence

the court shall upon request

permit the defendant, or his

counsel if he is so represen

ted, to read the report of the

presentence investigation exclu

sive of any recommendation as to

sentence, but not to the extent

that in the opinion of the court

the report contains diagnostic

opinion which might seriously

disrupt a program of rehabilita

tion, sources of information ob

tained upon a promise of confiden

tiality , or any other information

which, if disclosed, might result

in harm, physical or otherwise,

to the defendant or other per

sons; and the court shall afford

the defendant or his counsel an

opportunity to comment thereon

and, at the discretion of the

court, to introduce testimony or

other information relating to any

alleged factual inaccuracy con

tained in the presentence report."

(Emphasis supplied.)

51

Thus, both rules permit the exercise of a

reasoned discretion by the trial judge in

the disclosure in determining the extent

of disclosure of the contents of a pre

sentence report. At this point, the words

of Mr. Justice Adkins in writing the major

ity opinion in State v. Dixon3 283 So.2d 1

(Fla. 1973), come to mind.

"Two points can, however, be gleaned

from a careful reading of the nine

separate opinions constituting Furman

v. Georgia, supra. First, the opin

ion does not abolish capital punish

ment, as only two justices— Mr. Jus

tice Brennan and Mr. Justice Marshall

— adopted that extreme position. The

second point is a corollary to the

first, and one easily drawn. The

mere presence of discretion in the

sentencing procedure cannot render

the procedure violative of Furman v.

Georgia, supra; it was, rather, the

quality of discretion and the manner

in which it was applied that dictated

the rule of law which constitutes

Furman v. Georgia, supra.

"Discretion and judgment are essential

to the judicial process, and are pre

sent at all stages of its progression

— -arrest, arraignment, trial, verdict,

52

and onward through final appeal.

Even after the final appeal is

laid to rest, complete discretion

remains in the executive branch

of government to honor or reject

a plea for clemency. See Fla.

Const., art. IV, § 8, F.S.A., and

U.S. Const., art. II, § 2.

"Thus, if the judicial discretion

possible and necessary under Fla.

Stat. § 921.141, F.S.A., can be

shown to be reasonable and con

trolled, rather than capricious

and discriminatory, the test of

Furman v. Georgia, supra, has

been met. What new test the

Supreme Court of the United States

might develop at a later date, it

is not for this Court to suggest.

* * *

"Review by this Court guarantees

that the reasons present in one

case will reach a similar result

to that reached under similar

circumstances in another case.

No longer will one man die and

another live on the basis of race,

or a woman live and a man die on

the basis of sex. If a defendant

is sentenced to die, this Court

can review that case in light of

the other decisions and determine

whether or not the punishment is

too great. Thus, the discretion

charged in Furman v. Georgia, supra,

can be controlled and channeled

53

until the sentencing process be

comes a matter of reasoned judg

ment rather than an exercise in

discretion at all.” Id. at 6, 7,

10.

Much has been said and written on the

issue of disclosure versus nondisclosure

of the confidential portion of a pre

sentence report. Petitioner's entire

brief is based on the premise that because

of the failure of the trial judge to sua

sponte furnish counsel for both parties

a copy of the confidential portion of the

presentence report he has suffered a

grievous denial of his constitutional

rights. A reading of petitioner's brief

conveys the unmistakable impression that

the confidential portion of the presen

tence report contains gross inaccuracies,

misrepresentations, and other distortions

of the truth. It is urged that all of

these terrible accusations could have been

54

rebutted and the truth of the matter shown

if only petitioner and/or his counsel could

have been furnished with a copy thereof.

Therefore, respondent has secured a copy

of the "Confidential Evaluation" which is

the confidential portion of the presentence

report that was furnished to the trial

judge at the sentencing phase of petitioner's

trial. It forms the appendix to this brief.

It is readily apparent that most, if not

all, of the material found in the confiden

tial portion is also contained in the non-

confidential portion (A 133-137). The

truth of the matter is there is nothing

in the confidential portion that is not

found in the non-confidential part of the

presentence report. A fair appraisal of

both the confidential and the non-

confidential portions of the presen

tence report compels the conclusion that

55

failure to furnish a copy of the confiden

tial portion to petitioner did not result

in a denial of any of his constitutional

rights.

Conclusion

The judgment of the Supreme Court of

Florida should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Robert L. Shevin

Attorney General

By:

Wallace E. Allbritton

Assistant Attorney General

56

CONFIDENTIAL EVALUATION

Name Daniel Wilbur Gardner Dist. # 4 2 __

I. Offense; It is obvious that the subject

has received a fair trial. He apparently

was under heavy influence of alcohol, which

was normal for him. Apparently, he beat

his wife to an extreme on this occasion,

which resulted in her death. It is pos

sible that the subject did not remember

what he did, due to the fact that he was

highly intoxicated. He continually showed

remorse for what happened, claimed that

he did not remember, feels he should not

be held responsible for something that he

cannot remember.

II. Prior Arrests & Convictions: A check

of the subject's record will indicate that

he is a drinker, has been arrested several

times for disorderly conduct, and fight-

A p p e n d i x "A"

57

ing. The charge in Ft. Myers on 7-20-50

for investigation of Aggravated Assault

was not able to be verified, due to the

fact that the time limit involved. It

is noted that the records in Ft. Myers

are quite sketchy about what happened.

The subject volunteered the statement

that this attack was the result of his

first wife. He stated that they appar

ently had a fight and she went off with

somebody to a trailer. He claims he

went by the trailer and heard his wife

telling the person to leave her alone.

He stated he broke into the trailer,

noticed a colored man sitting in the

front parlor with no clothes on and his

wife in the back room with a white man

apparently fighting or arguing. He

stated that he took out his knife and

Appendix "A"

58

told the colored man to get out of there,

and went back to the bedroom he apparently

claimed brushed past his wife and cut her

with the knife and threatened the other

man. He stated this all subsided when

the States Attorney saw the disposition of

the case and stated that, the man had every

right to defend his wife, so eventually

the charge was dropped. The Other Assault

charges on 4-2-70 and 4-21-72, were Assaults

and Battery, both being on the subject's

wife. It should be noted that these charges

were dropped at the request of the wife.

III. Plan: Subject does have an adequate

residence and employment plan in Homosassa,

but it is felt that this subject is no fit

candidate for Probation.

IV. Analysis: Before the Court is a 39

Ap p e n d i x "A"

59

year old white male who was charged with

and found guilty of Murder in the 1st

degree.

This offense is the result of the subject

apparently under the influence of alcohol,

administering a severe beating, both with

his hands and feet and objects. Appar

ently, beat his wife to death over no

apparent reason.

This subject has resided most of his life

in the Homosassa area, being considered

the usual drinker and fighter. His

younger life was spent mostly being shifted

around from Mother to Boys Home. The

subject was more or less to let run on

his own, without any supervision. Sub

ject was married twice, the second mar

riage being to the victim in this case.

Appendix "A"

60

It should be noted that this subject is

a heavy drinker, which apparently has

governed most of his life. Subject spent

a short time in the Air Force, stating

that he received a General Discharge under

honorable conditions. He stated that he

did spend some time in the brig, which

was mostly due to drinking and disobey

ing orders. Subject does have a trade as

a carpenter, but apparently only works when

he feels too. Florida Power indicated

that he had worked on and off for the

past five years, but apparently was

laid off, mostly due to his drinking.

They noted that the subject was not work

ing, two months prior to this incident.

Criminal Record: The subject does possess

Ap p e n d i x "A"

a fairly long record, most of it due to

61

drinking and fighting and Assault charges

as a result of drinking. It should be

noted that the subject in these charges

has had at least three times when he has

beat on his wife. The subject does pos

sess an Assaultive nature and apparently

is aggravated by drinking.

Most of the feelings in this case are

against the subject. Police feel that he

is an extremely poor candidate for Proba

tion due to his drinking and fighting,

also they feel that he should not be

allowed on the streets, due to what he

did to his wife.

It is the opinion of this supervisor that

the jury in this case found a true verdict

and the subject had a fair trial, that he

would be an extremely poor candidate for

A p p e n d i x "A"

62

Ap p e n d i x "A"

probation.

Respectfully Submitted,

Michael C. Dippolito,

District Supervisor

MCD/kb

1-28-7 4