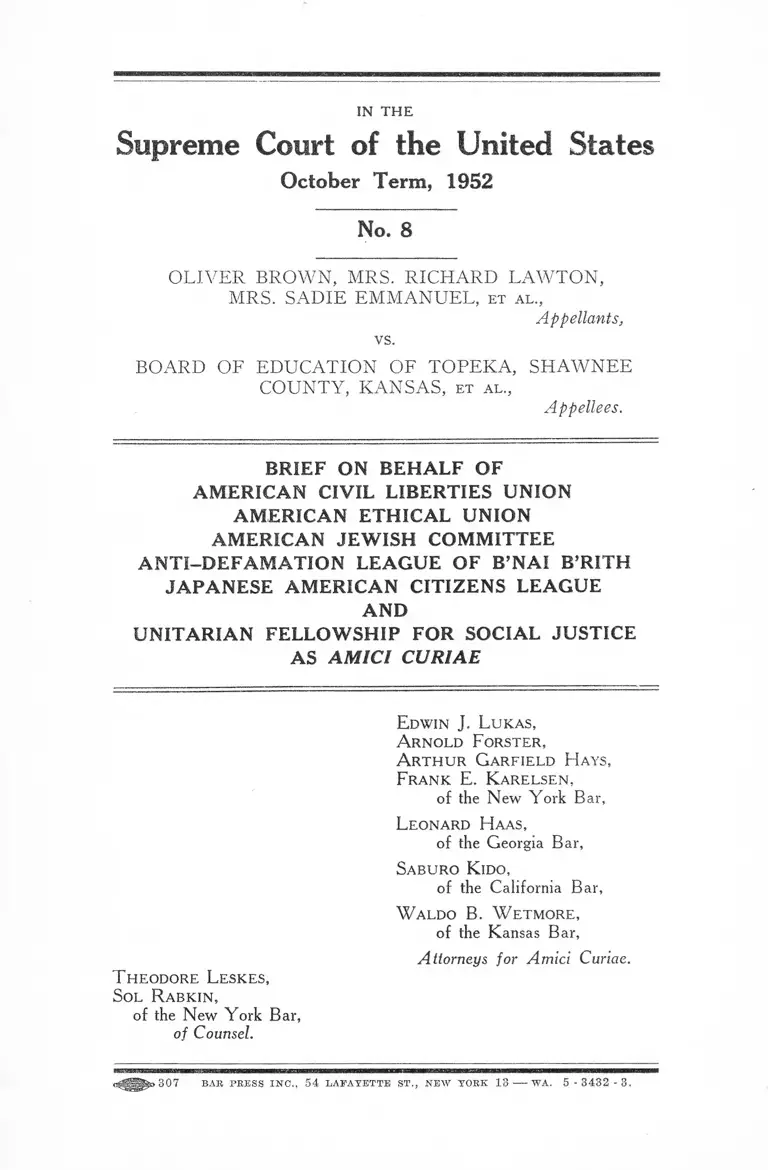

Brown v. Board of Education Brief on Behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union, American Ethical Union, American Jewish Committee, Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, Japanese American Citizens League, and Unitarian Fellowship for Social Justice as Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

November 15, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Brief on Behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union, American Ethical Union, American Jewish Committee, Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, Japanese American Citizens League, and Unitarian Fellowship for Social Justice as Amici Curiae, 1952. 46d4ddd5-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ec029e0f-61db-419b-9e11-05c381064358/brown-v-board-of-education-brief-on-behalf-of-the-american-civil-liberties-union-american-ethical-union-american-jewish-committee-anti-defamation-league-of-bnai-brith-japanese-american-citizens-league-and-unitarian-fellowship-for-social-jus. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN TH E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1952

No. 8

OLIVER BROWN, MRS. RICHARD LAW TON,

MRS. SADIE EMMANUEL, et a l .,

Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, SHAWNEE

COUNTY, KANSAS, et a l .,

Appellees.

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

AMERICAN ETHICAL UNION

AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE

ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF B’NAI B’RITH

JAPANESE AMERICAN CITIZENS LEAGUE

AND

UNITARIAN FELLOWSHIP FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE

AS AMICI CURIAE

Edwin J. Lukas,

A rnold Forster,

A rthur Garfield Hays,

Frank E. Karelsen,

of the New York Bar,

Leonard Haas,

of the Georgia Bar,

Saburo Kido,

of the California Bar,

W aldo B. W etmore,

of the Kansas Bar,

Attorneys for Amici Curiae.

T heodore Leskes,

Sol Rabkin,

of the New York Bar,

of Counsel.

3 0 7 B A R P R E SS IN C ., 5 4 L A F A Y E T T E S T ., N E W Y O R K 1 3 -----W A . 5 - 3 4 3 2 - 3 .

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

I nterest oe t h e A m ici ............................................................. 1

S tatem en t of th e Ca s e ' ........................................................... 3

T h e S tatu te I nvolved ............................................................. 4

T h e Question P resented ...................................................... 4

S u m m ary of A rgu m en t ........................................................... 5

A rgum ent

I. The validity under the equal protection of

the laws clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment of racial segregation in public educa

tional facilities has never been decided by

this Court ...................................................... 6

II. Racial segregation in public educational

institutions is an unconstitutional classifi

cation under the equal protection of the

laws clause of the Fourteenth Amendment 12

III. The finding of the court below, that Negro

children are disadvantaged by the segre

gated public school system of Topeka, re

quires this Court to disavow the “ separate

but equal” doctrine as it has been applied

to public educational institutions ................ 16

C onclusion .................................................................... 28

Appendix 33

11 Index

Table of Cases

PAGE

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U. S. 219 (1911)................... 13

Banks v. San Francisco Housing Authority, decided

by the Superior Court of San Francisco, Cal.,

Oct. 1, 1952 ............................................................. 19

Belton v. Gebhart, decided by the Supreme Court of

Delaware, Aug. 28, 1952 ........................................ 19

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U. S. 45 (1908)...... 8

Briggs v. Elliott, 98 F. Supp. 529 (1951)................... 19

Brotherhood of R. R. Trainmen v. Howard, —; II. S.

—, 72 S. Ct. 1022 (1952) ......................................... 13

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 98 F. Supp.

797 (1951) ............................................................... 18,19

Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278 (1936) .............. 13

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) ................. 13, 14

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227 (1940)................ 13

Gumming v. County Board of Education, 175 U. S.

528 (1899) ............................................................... 7

Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147 (1948) ................... . 10,18

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 (1927).......... 5, 9,10,11,18

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45 (1935)................... 19

Guinn v. U. S., 238 U. S. 347 (1915)............................. 14

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485 (1878) ........................... 6, 7

Henderson v. U. S., 339 U. S. 816 (1950)................... 13

Hirabayashi v. H. S., 320 H. S. 81 (1943)............12,15,16

Jones v. Opelika, 316 U. S. 584 (1942)....................... 19

Korematsu v. IT. S., 323 H. S. 214 (1944) ................. 12,15

Index 111

PAGE

Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U. S. 61

(1911) ...................................................................... 12

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 151

(1914) ...................................................................... 10

McGee v. Mississippi, — Miss. —, 40 So. 2nd 160

(1949) ............. 28

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Board of Regents, 339

U. S. 637 (1950) .................................8,10,11,18,20

Minersville School District v. Gobitis, 310 U. S. 586

(1940) ...................................................................... 19

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337

(1938) ...................................................................9,10,18

Mitchell v. U. S., 313 U. S. 80 (1941)......................... 13

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 IT. S. 373 (1946)................. 13

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U, S. 105 (1943).......... 19

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 (1927)..................... 14

Oyama v. California, 332 IT. S. 633 (1948)................... 12

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 IT. S. 537 (1896)

5,7, 8,10,11,18,19, 20

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1 (1948) ..................... 13,14

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 1'. S. 50 (1951)...................... 13

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of

Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631 (1948) ..........................10,18

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944) .................... 14,19

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co., 323

U. S. 192 (1944) ................................................ 13

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880)...... 13

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950) ..........8,10,18,20

Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission, 334 U. S.

410 (1948) .............................................................. 14

IV Index

PAGE

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, 323

U. S. 210 (1944) ..................................................... 13

U. S. v. Reynolds, 235 U. S. 133 (1914)....................... 13

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U. S. 624 (1943) .............................................. 19

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) ................ 14

Yu Gong Eng v. Trinidad, 271 IT. S. 500 (1926)........ 14

Other Authorities Cited

Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford,

The Authoritarian Personality (1950) ................ 18

52 American Jewish Yearbook (1951)......................... 20

Antwerp Le Matin, May 1951 ...................................... 31

The Austin Statesman, November 14, 1950................ 21

Biennial Report, 1949-1951, State of New Jersey,

Dep’t. of Education, Division Against Dis

crimination .............................................................25, 26

Bond, Education of the Negro in the American Social

Order (1934) ........................................................... 17,27

Chicago Sun-Times, September 26, 1950 ..................... 24

Cologne Welt Der Arbeit, April 7, 1950 ..................... 30

Dallas Times Herald, October 2, 1951 ......................... 20

Dawkins, Kentucky Outgrows Segregation, The Sur

vey, July 1950 ......................................................... 21

Dayton Journal Herald, June 23, 1950 ....................... 25

Frenkel-Brunswik, A Study of Prejudice in Children,

1 Human Relations 295 (1948).............................. 18

Index v

Gallagher, American Caste and the Negro College

(1938) ...................................................................... 17

Goodman, Race Awareness in Young Children (1952) 18

Heinrich, The Psychology of a Suppressed People

(1937) ......... "............“.............................................. 17

The Houston Chronicle, Sept. 10, 1952 ....................... 20

The Houston Informer, December 5, 1951 .................. 20

The Houston Post, January 9, 1951 ............................. 20

Little Rock Arkansas Gazette, July 1, 1951................ 21

Long, The Intelligence of Colored Elementary Pupils

in Washington, D. C., 3 J. of Negro Ed. 205

(1934) ... ............................. 17

Long, Some Psychogenic Hazards of Segregated

Education of Negroes, 4 J. of Negro Ed. 336

(1935) ...................................................................... 17

Marseilles Semailles, May 18, 1951 ............................. 29

Miami Herald, May 6, 1951 .......................................... 21

46 Michigan L. Rev. (1948) .............. 7

Morisey, A New Trend in Private Colleges, New

South, Aug.-Sept. 1951 .......................................... 22

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944) ........................ 6,18

New York Herald Tribune, June 23, 1949................... 21

New York Herald Tribune, Sept. 28, 1951.................. 22

New York Post, Aug. 24, 1948 .... ............................... 21

The New York Times, January 30, 1950 ................... 24

The Oklahoma City Daily Oklahoman, June 7, 1951 . 20

PAGE

Paris L ’Aube, May 9, 1951 ................

Pittsburgh Courier, December 1, 1951

29, 30

24

V I Index

PAGE

President’s Commission on Higher Education, Higher

Education for American Democracy (1947)...... 17

President’s Committee on Civil Rights, To Secure

These Rights (1947) .............................................. 27

Richmond News Leader, September 25, 1952..............22, 23

Santa Pe New Mexican, September 2, 1951................ 23

Saveth, The Supreme Court and Segregation, The

Survey, July 1951 ................................................. 23

Segregation in Public Schools—A Violation of

“ Equal Protection of the Laws” , 56 Yale L. J.

1059 (1947) .................... 17

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 17, 1952................... 22

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 7, 1950; May 11, 1952.. 22

Thompson, C. H., Letter to the Editor, The New

York Times, April 6, 1952 .................................... 27

Vienna Arbeiter-Zeitung, February 4, 1951................ 29

Washington Times-Herald, July 17, 1951................... 22

IN TH E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1952

No. 8

OLIVER BROWN, MRS. RICHARD LAW TON,

MRS. SADIE EMMANUEL, et a l .,

Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, SHAWNEE

COUNTY, KANSAS, et a l .,

Appellees.

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

AMERICAN ETHICAL UNION

AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE

ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF B’NAI B’RITH

JAPANESE AMERICAN CITIZENS LEAGUE

AND

UNITARIAN FELLOWSHIP FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE

AS AMICI CURIAE

Interest of the Amici

This brief is filed, with the consent of both parties, on

behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union, the American

Ethical Union, American Jewish Committee, the Anti-

2

Defamation League of B ’nai B ’rith, the Japanese Ameri

can Citizens League and the Unitarian Fellowship for

Social Justice. The Appendix contains a description of

each of these organizations.

The present case and the companion cases, all involv

ing the constitutionality of racial segregation in public

elementary and secondary schools, present an issue with

which all six organizations are deeply concerned because

such segregation deprives millions of persons of rights

that are freely enjoyed by others and adversely affects

the entire democratic structure of our society.

We have read the briefs of the appellants, with the

appendix thereto, and we unequivocally endorse the argu

ments, legal, educational and sociological, therein advanced.

In this amici brief we are urging arguments which have

not been made in the appellants’ briefs and which we

believe should be presented to this Court.

3

Statement of the Case

The adult appellants are Negro citizens of the United

States and of the State of Kansas (R. 3-4) while the

infant appellants are their children eligible to attend and

now attending elementary schools in Topeka, Kansas, a

city of the first class within the meaning of Section 13-101,

General Statutes of Kansas, 1949. Appellees are State

officers empowered by State law to maintain and operate

the public schools of Topeka, Kansas.

On March 22, 1951, appellants instituted this action

seeking a declaratory judgment and an injunction to com

pel the State to admit Negro children to the elementary

public schools of Topeka on an unsegregated basis on the

ground that segregation deprived them of equal educa

tional opportunities within the meaning of the Fourteenth

Amendment (R. 2-7). In their answer, appellees admitted

that they acted pursuant to the statute, that infant ap

pellants were not eligible to attend any of the eighteen

“ white” elementary schools solely because of their race

and color (R. 12, 24), but that they were eligible to

attend the equivalent public schools maintained for Negro

children in the City of Topeka (R. 11, 12). The Attorney

General of the State of Kansas filed a separate answer

defending the validity of the statute in question (R. 14).

The court below was convened in accordance with Title

28, United States Code, §2284 and on June 25-26 a trial

on the merits took place (R. 63 et seq.). On August 3,

1951, the court below filed its opinion, 98 F. Supp. 797 (R.

238-244), its findings of fact (R, 244-246), and conclusions

of law (R. 246-247), and entered a final judgment and de

cree in appellees’ favor denying the relief sought (R. 247).

Appellants filed a petition for appeal on October 1,

1951 (R. 248), and an order allowing the appeal was duly

entered (R, 250). Probable jurisdiction was noted on

June 9, 1952 (R, 254). Jurisdiction of this Court rests on

Title 28, United States Code, §§1253 and 2201 (b).

4

The Statute Involved

Segregated elementary schools in Topeka, Kansas, are

maintained solely pursuant to the authority of Section

72-1724 of the General Statutes of Kansas (1949) which

reads as follows:

Powers of hoard; separate schools for white and

colored children; manual training. The hoard of edu

cation shall have power to elect their own officers,

make all necessary rules for the government of the

schools of such city under its charge and control and

of the board, subject to the provisions of this act and

the laws of this state; to organize and maintain sep

arate schools for the education of white and colored

children, including the high schools in Kansas City,

Kans.; no discrimination on account of color shall he

made in high schools except as provided herein; to

exercise the sole control over the public schools and

school property of such city; and shall have the power

to establish a high school or high schools in connec

tion with manual training and instruction or other

wise, and to maintain the same as a part of the public-

school system of said city. (G. S. 1868, Ch. 18, §75;

L, 1879, Ch. 81, §1; L. 1905, Ch. 414, §1; Feb.'28;

R. S. 1923, §72-1724.)

The Question Presented

The question presented by this appeal is whether the

State of Kansas, or indeed any State, by establishing

racial segregation in its public elementary school system,

has violated the equal protection of the laws clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

5

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This Court has never ruled directly on the constitu

tionality of racial segregation in public elementary schools.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896) and Gong Lum

v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 (1927), relied upon by the court

below, are not controlling here.

Segregation in State-supported educational institutions

violates the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by

the Fourteenth Amendment in that it is an inadmissible

classification. This Court has consistently rejected dif

ferential treatment by State authority predicated upon

racial classifications or distinctions.

The finding of the lower court that Negro children are

disadvantaged by the segregated public school system

necessitates granting the relief requested. That which is

unequal in fact cannot be equal in law and, therefore,

segregation and equality cannot co-exist in public educa

tion.

6

P O I N T I

The validity under the equal protection of the

laws clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of racial

segregation in public educational facilities has never

been decided by this Court.

The issue now squarely before this Court is whether

the State of Kansas, pursuant to statute, may maintain

and operate racially segregated public elementary schools,

without heed to the damage inflicted by segregation upon

its Negro victims. Despite the transcendent importance of

the question, this Court has never ruled directly on the

constitutionality of racial segregation in public education.

The Court has ruled on related problems, such as the

validity of racial segregation in transportation and in

housing. Kegretfully, it has, but always in dictum, ap

peared to accept racial segregation where the validity of

segregation was not actually before the Court. Historically,

these dicta reflect the fact that prior to World War I, the

status of the American Negro was such that he could make

no realistic demand for equality of treatment in those sec

tions of the country in which he lived in substantial num

bers. Because of his depressed economic condition and

concentration in agriculture, his children could not even

obtain the most elementary education. Myrdal, An Ameri

can Dilemma, Ch. 8-9 (1944).

Following the adoption in 1868 of the Fourteenth

Amendment, the earliest case in which some reference was

made by this Court to racial segregation in education was

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485 (1878). That ease involved

the validity of a State statute prohibiting segregation in

7

public carriers. The statute was declared unconstitutional

as an improper regulation of foreign and interstate com

merce. In a concurring opinion, Mr. Justice Clifford re

viewed with approval the conclusions of a number of

State cases which had upheld the reasonableness of racial

segregation in education and stated in dictum that segre

gation in the public schools did not violate the Fourteenth

Amendment if physically equal facilities for Negroes were

provided. It is probably unnecessary for us to note that

no evidence was offered in that ease, because it would have

been irrelevant, that school segregation must in fact in

volve inequality.

In 1896 this Court decided Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

U. S. 537 (1896), which sustained the constitutionality of

a Louisiana statute requiring public carriers to furnish

separate but equal coach accommodations for whites and

Negroes. The Court as before, in dictum, cited with ap

proval several old State cases which had held that a State

could require the segregation of racial groups in its edu

cational system.

The constitutionality of “ separate but equal” facili

ties in education was concededly not before the Court in

either the Hall or the Plessy cases. Yet, although there

was no evidentiary or psycho-sociological basis for a dis

cussion of equal facilities in education, and in spite of the

fact that the statements of the Court were clearly dicta,

the Plessy case has been cited to this date by State and

lower Federal courts to sustain the constitutionality of

segregation in public educational institutions. See cases

cited, 46 Mich. L. Rev. 639, 643 (1948).

Three years later, this Court decided Gumming v.

County Board of Education, 175 U. S. 528 (1899). There

an injunction was sought to restrain a board of education

8

in Georgia from maintaining a high school for white chil

dren where none was maintained for Negro children. The

State court had upheld the board, saying that its alloca

tion of funds did not involve bad faith or abuse of dis

cretion. In affirming the decision of the State court, this

Court speaking through Mr. Justice Harlan, the lone dis

senter in Plessy, stated expressly that racial segregation

in the school system was not in issue. (542, 546)

The next case before this Court which involved com

pulsory educational segregation was Berea College v.

Kentucky, 211 U. S. 45 (1908), wherein the validity of a

State statute which prohibited domestic corporations from

teaching white and Negro pupils in the same private edu

cational institution was attacked. While the scope of the

statute was broad enough to include individuals as well

as corporations, this Court said:

. . . it is unnecessary for us to consider anything

more than the question of its validity as applied to

corporations. . . . Even if it were conceded that its

assertions of power over individuals cannot be sus

tained, still it must be upheld so far as it restrains

corporations. (54)

This Court agreed with the reasoning of the State

^court that the statute could be upheld as coming within

the power of a State over one of its own corporate crea

tures. The statute was not deemed to have worked a dep

rivation of property rights. The rights of individuals were

not considered.1

1 Interestingly, since the decisions of this Court in Sweatt v.

Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950) and in McLaurin v. Oklahoma,

339 U. S. 637 (1950), Berea College accepts Negro students.

9

Not until 1927 did racial classification in educational

institutions again become the subject of controversy be

fore this Court. In Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 (1927),

a Chinese girl contested the right of the State of Missis

sippi to assign her to a Negro school under the State’s

segregated school system. Mississippi contended that

under its statute requiring separate schools to be main

tained for children of the white and colored races, the

plaintiff could not insist on being classed with the whites

and that the legislature was not compelled to provide

separate schools for each of the non-white races.

The issue of segregation was not presented in that

case. The plaintiff accepted the system of segregation in

the public schools of the State but contested her classifi

cation within that system.

Nor was the validity of segregation before the Court

in the case of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S.

337 (1938). There the petitioner was refused admission

to the University of Missouri Law School, a State-sup

ported institution, solely because he was a Negro. He

brought mandamus to compel the University to admit him.

The State, having no law school for Negroes, sought to

fulfill its obligation to provide equal educational facilities

by offering to pay the petitioner’s tuition for a legal edu

cation in another State. This the Court held did not sat

isfy the constitutional requirement. It said that the peti

tioner was entitled to be admitted to the University of

Missouri Law School in the absence of other and proper

provision for his legal training within the State of Mis

souri. The issue wTas whether an otherwise qualified Negro

applicant for law training could be excluded from the

only State-supported law school. This Court assumed that

1 0

the validity of equal facilities in racially separate schools

was settled by earlier decisions and cited the Plessy case,

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 151

(1914), both of which involved segregation in public car

riers, and the Gong Lum case. But the constitutional

validity of segregation was not decided.

The next consideration of a related problem was in

1948 in Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of

Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631. This Court, in a per curiam

decision, said that the State must provide law school fa

cilities for the Negro petitioner “ in conformity with the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and

provide it as soon as it does for applicants of any other

group” (633). The facts in the Sipuel case were similar

to those in the Gaines case, in that no law school facilities

were afforded Negroes by the State of Oklahoma.

Segregation was not at issue in the Sipuel case. This

Court stated in Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147 (1948), that:

The petition for certiorari in Sipuel v. University

of Oklahoma did not present the issue whether a state

might not satisfy the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment by establishing a separate

law school for Negroes. On submission, we were

clear it was not an issue here. (150)

The most recent cases involving segregation in public

institutions of learning were Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S.

629 (1950) and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Board of

Regents, 339 U. S. 637 (1950). Although the petitioners

and numerous amici in those cases urged this Court to rule

expressly that discrimination inevitably results from en

forced segregation in educational institutions, the Court did

not reach that question. In Sweatt, Mr. Chief Justice Yin-

son, speaking for a unanimous Court, said, “ Nor need we

1 1

reach petitioner’s contention that Plessy v. Ferguson

should be reexamined in the light of contemporary knowl

edge respecting the purposes of the Fourteenth Amend

ment and the effects of racial segregation” (636). The

judgment of the court below was reversed and the Uni

versity of Texas Law School was ordered to admit the

petitioner because equivalent educational opportunity was

not afforded by the hastily organized Negro law school.

In McLaurin, again speaking for a unanimous bench,

Mr. Chief Justice Vinson expressly limited the decision:

In this case, we are faced with the question whether

a state may, after admitting a student to graduate

instruction in its state university, afford him different

treatment from other students solely because of his

race. We decide only this issue . . . (638)

Thus in no case previously before this Court, in which

racial segregation in public education has been the subject

of comment in an opinion, has the Court felt called upon

to rule squarely on the issue: Does segregation in public

educational institutions meet the requirements of the equal

protection of the laws clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment?

We emphasize that absence of a specific ruling at the

outset of this brief because of the thread of urgency

running through the fabric of much previous argument

on the crucial issue in this case, namely, that the “ sepa

rate but equal” doctrine, as it has been thought to apply

to public educational institutions, should be “ overruled” .

Indeed, in that framework, there is nothing to overrule.

But there are dicta which must be disavowed. The con

stitutionality of segregation in educational institutions

was clearly not involved in Plessy or Gong Lum, the two

cases relied upon by the court below.

1 2

P O I N T II

Racial segregation in public educational institu

tions is an unconstitutional classification under the

equal protection of the laws clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

This Court’s decisions in eases involving the constitu

tionality of governmental action reveal a special scrutiny

and constant vigilance in those instances where such ac

tion was predicated upon alleged racial distinctions or

where racial classifications were involved. Except in

times of overriding peril or crisis, this Court has rejected

all obvious or devious efforts to establish racial or reli

gious lines of demarcation for the enjoyment of civil

rights.

Whereas in cases involving other types of legislative

classifications, the “ one who assails the classification . . .

must carry the burden of showing that it does not rest

upon any reasonable basis” , Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic

Gas Co., 220 U. S. 61, 79 (1911), “ all legal restrictions

which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are

immediately suspect” . Korematsu v. U. 8., 323 U. S. 214,

216 (1944).

Again, “ only the most exceptional circumstances can

excuse discrimination on that basis in the face of the

equal protection clause.” Oyama v. California, 332 U. S.

633, 646 (1948). In Hirabayashi v. U. 8., 320 U. S. 81

(1943), this Court said:

Distinctions between citizens solely because of their

ancestry are by their very nature odious to a free

people whose institutions are founded upon the doc

13

trine of equality. For that reason, legislative classi-

cation or discrimination based on race alone has

often been held to be a denial of equal protection.

( 100)

In the application of these principles, the Court has,

with one exception (discussed infra), always declared gov

ernmental classification based on race or color to be con

stitutionally invalid.

This Court has ruled that Negroes must be treated the

same as whites with respect to the privilege and duty of

jury service. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303

(1880). It has stricken down state statutes aimed at keep

ing the Negro “ in his place.” Bailey v. Alabama, 219

U. S. 219 (1911); U. S. v. Reynolds, 235 U. S. 133 (1914).

Common carriers engaged in interstate travel have been

prevented from segregating and discriminating on the

basis of race or color. Mitchell v. U. 8., 313 IT. S. 80

(1941) ; Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 (1946); Hen

derson v. U. 8., 339 IT. S. 816 (1950). Repeated instances

of prejudice in criminal cases evidenced by brutal treat

ment of Negroes have been condemned. Brown v. Mis

sissippi, 297 IT. S. 278 (1936); Chambers v. Florida,

309 IT. S. 227 (1940); Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U. S. 50

(1951). Racial segregation through zoning and attempts

to institutionalize ghettos by restrictive covenants have

been outlawed. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 IT. S. 60 (1917);

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1 (1948). Discrimination

has been forbidden in labor unions that receive their col

lective bargaining and representation powers by virtue

of statute. Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R,ailroad Co.,

323 IT. S. 192 (1944); Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomo

tive Firemen, 323 U. S. 210 (1944); Brotherhood of R. R.

Trainmen v. Howard, — U. S. — , 72 S. Ct. 1022 (1952).

14

From time to time, this Court has stricken down all the

various devices used to prevent or limit Negroes from

participating in elections. Guinn v. U. S., 238 U. S. 347

(1915); Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 (1927); Smith v.

Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944). So, too, laws which in

their administration have effected a limitation or denial

of the right to carry on a business or calling because of

race or ancestry, have been declared unconstitutional.

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886); Yu Cong Eng

v. Trinidad, 271 F. S. 500 (1926); Takahashi v. Fish and

Game Commission, 334 U. S. 410 (1948).

In Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, which involved a

racial residential zoning ordinance, the State invoked its

authority to pass laws in the exercise of its police power,

and urged that this compulsory separation of the races

in habitation be sustained because it would “ promote the

public peace by preventing race conflicts” (81). This

Court rejected that contention, saying:

The authority of the state to pass laws in the exercise

of the police power . . . is very broad . . . [and] the

exercise of this power is not to be interfered with by

the courts where it is within the scope of legislative

authority and the means adopted reasonably tend to

accomplish a lawful purpose. But it is equally well

established that the police power . . . cannot justify

the passage of a law or ordinance which runs counter

to the limitations of the Federal Constitution . . . (74).

The police power of the State, broad as it is, does not

justify a racial classification where rights created or pro

tected by the Constitution are involved.

In Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 F. S. 1, this Court, by

unanimous decision, held that the enforcement of racial

restrictive covenants by State courts is State action,

15

prohibited by the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment. In the course of its decision, the

Court measurably strengthened the equal protection clause

as a formidable barrier to restrictions having the effect

of racial segregation. The contention was there pressed

that since the State courts stand ready to enforce racial

covenants excluding white persons from occupancy or

ownership, enforcement of covenants excluding Negroes

is not a denial of equal protection. This Court rejected

the equality of application argument, decisively dismissing

it in the following language:

This contention does not bear scruitiny. . . . The

rights created by the first section of the Fourteenth

Amendment are, by its terms, guaranteed to the

individual. The rights established are personal rights.

It is, therefore, no answer to these petitioners to say

that the courts may also be induced to deny white

persons rights of ownership and occupancy on grounds

of race or color. Equal protection of the laws is not

achieved through indiscriminate imposition of in

equalities. (21, 22)

There has been but one recent departure from this rule.

This Court stated that “ in the crisis of war and of

threatened invasion” when the national safety might

appear to be imperilled, it will permit a racial classifica

tion by the Federal Government. Hirabayashi v. U. 8 .,

320 U. S. 81, 101. That case involved a prosecution for

failure to obey a curfew order directed against citizens

of Japanese ancestry. Korematsu v. U. 8., 323 U. S. 214,

arising out of the same war emergency, involved the

validity of a governmental order excluding all persons of

Japanese ancestry from the West Coast military area.

The Court, on the grounds of overriding pressing public

urgency in time of war, sustained the racial classification

16

in these cases, but it emphasized that this was an ex

traordinary exception. “ [Legislative classification or dis

crimination based on race alone has often been held to

be a denial of equal protection. . . . We may assume” ,

continued the Court, “ that these considerations would be

controlling here were it not for the fact that the danger

of espionage and sabotage, in time of war and of threat

ened invasion” has made necessary this racial classi

fication, which “ is not to be condemned merely because

in other and in most circumstances racial distinctions are

irrelevant.” Hirabayashi v. TJ. 8., supra, 101.

Clearly, State laws providing for racial segregation in

public educational facilities are not accompanied by any

“ pressing public necessity” . The record here is barren

of any such showing, as indeed it would have to be. Rather,

there is a pressing public necessity to give all American

citizens their due—equality of opportunity to use educa

tional facilities established by the State for its inhabitants.

P O I N T I I I

The finding of the court below, that Negro chil

dren are disadvantaged by the segregated public

school system of Topeka, requires this Court to dis

avow the “separate but equal” doctrine as it has

been applied to public educational institutions.

In one vital respect, the problem posed by this record

is sharpened to the point of unique narrowness. The un

challenged finding that segregation irreparably damages

the child lifts this case out of the murky realm of specu

lation on the issue of “ equality” of facilities, into the

17

area of certainty that segregation and equality cannot

co-exist. That which is unequal in fact cannot be equal in

law.

It is respectfully submitted that the finding of the court

below, that Negro children were disadvantaged by the

segregation of white and colored students in the public

elementary schools, requires this Court to reverse the

lower court’s refusal to grant the requested relief. The

lower court found as a fact that the segregation of white

and Negro children in the public schools “ has a detri

mental effect upon the colored children” ; that such segre

gation creates in Negro children a “ sense of inferiority”

which “ affects the motivation of a child to learn” ; that

legally sanctioned segregation “ therefore has a tendency

to retard the educational and mental development of

[N]egro children and to deprive them of some of the

benefits they would receive in a racially integrated school

system. ’ ’

Educators and social scientists have long proclaimed

that these and other social evils necessarily flow from

racially segregated education. Segregation in Public

Schools—A Violation of “ Equal Protection of the Laws” ,

56 Yale L. J. 1059, 1061 (1947). See also Long, Some

Psychogenic Hazards of Segregated Education of Negroes,

4 J. of Negro Ed. 336, 343 (1935); Long, The Intelligence

of Colored Elementary Pupils in Washington, D. C., 3 J.

of Negro Ed. 205-222 (1934); Gallagher, American Caste

and the Negro College, 109, 184, 321-2 (1938); Bond, Edu

cation of the Negro in the American Social Order, 385

(1934); President’s Commission on Higher Education,

2 Higher Education for American Democracy 35 (1947);

Heinrich, The Psychology of a Suppressed People, 52, 57-

18

61 (1937); Myrdal, An American Dilemma, 54-5, 97-101,

577-8, 758; Frenkel-Brunswik, A Study of Prejudice in

Children, 1 Human Relations 295, 305 (1948); Goodman,

Race Awareness in Young Children (1952); Adorno,

Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford, The Authori

tarian Personality, Ch. IV, Y (1950).

Whenever this Court has been presented with a record

that established inequality in fact as between educational

opportunities offered by the State to its white and Negro

inhabitants, it has ordered the immediate termination of

the inequality. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 IT. S.

337; Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 IT. S. 631; Fisher v.

Hurst, 333 U. S. 147; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 IT. S. 629.

In McLaurin v. Oklahoma, 339 IT. S. 637, this Court went

even further to hold that officially imposed racial segre

gation within a State-maintained school violated the equal

protection clause. It is noteworthy that the court below

said in its opinion, where “ segregation within a school

as in the McLaurin case is a denial of due process, it is

difficult to see why segregation in separate schools would

not result in the same denial.” Brown v. Board of Edu

cation of Topeka, 98 F. Supp. 797, 800 (Emphasis added).

We respectfully urge this Court to follow the prin

ciples it recently enunciated in Sweatt and McLaurin,

rather than the unsound ones of Plessy and Gong Lum,

and to hold unequivocally that racial segregation per se

in all State educational institutions, is a violation of the

equal protection of the laws clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

The Need to Disavow Plessy

As we explained in Point I, we believe that Plessy is

not controlling. Assuming, arguendo, that the court below

was justified by Plessy in refusing to hold that segregation

19

in public elementary schools is per se discrimination under

the Fourteenth Amendment, this Court should now ex

pressly overrule Plessy and reverse the court below. This

Court has not hesitated in the past to overrule or recon

sider and reverse earlier decisions where the nature and

consequences of discrimination became fully disclosed or

apparent upon later consideration. Murdoch v. Pennsyl

vania, 319 U. S. 105 (1943), reversing Jones v. Opelika,

316 U. S. 584 (1942); West Virginia State Board of Edu

cation v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624 (1943), overruling Miners-

ville School District v. Gobitis, 310 U. S. 586 (1940); Smith

v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649, overruling Grovey v. Townsend,

295 U. 8. 45 (1935). “ In constitutional questions, where

correction depends upon amendment and not upon legis

lative action this Court through its history has freely

exercised its power to reexamine the basis of its constitu

tional decisions.” Smith v. Allwright, supra, 655 and cases

cited in footnote 10 thereto.

Lower courts, State and federal, have indicated clearly

that they believe a break with the “ separate but equal”

doctrine in education is “ in the wind” , but they insist

that they must await such a holding by this Court. Belton

v. Gebhart, decided by the Delaware Court of Chancery,

April 1, 1952, affirmed by the Supreme Court of that State

on August 28, 1952; Banks v. San Francisco Housing

Authority, decided October 1, 1952, by the Superior Court

of San Francisco; Brown v. Board of Education of To

peka, 98 F. Supp. 797, 798; Briggs v. Elliott, 98 F. Supp.

529, 535 (1951).

It is not surprising that American courts are ques

tioning the validity of Plessy in view of the tremendous

changes which have taken place since the turn of the cen

tury in the understanding of the nature of the individual

20

and his relationships to racial groupings and to society.

Scientific research in the fields of anthropology, sociology,

biology and education has demonstrated the fallaciousness

of the racial and blood strain concepts which are basic

to the majority opinion in Plessy.

Peaceful Integration Will Follow

The defenders of racial segregation have frequently

expressed the fear that compulsory destruction of the bar

riers in the public schools would increase racial tensions

and even cause strife. Such results, obviously, should be

avoided if possible, without yielding constitutional prin

ciples. Experience, however, has clearly demonstrated

that these dire predictions are unfounded.

Following this Court’s decision in McLaurin v. Okla

homa, 339 U. S. 637, Negro students applied for admission

and were admitted in large numbers to that State’s col

leges and universities. By June 1951, approximately 400

Negroes were enrolled at the University of Oklahoma and

at Oklahoma A & M, all without the slightest increase in

racial tension, but rather with every sign of increased

mutual understanding and respect. The Oklahoma City

Daily Oklahoman, June 7, 1951.

In Texas, after the decision in Sweatt v. Painter, 339

U. S. 629, two Negroes were admitted to the University

of Texas Law School and two others were admitted to the

Dental School. 52 American Jewish Yearbook 42 (1951);

The Houston Chronicle, Sept. 10, 1952. Negroes have also

been admitted to private institutions of higher learning

in Texas following Sweatt, Southern Methodist Univer

sity (The Houston Post, January 9, 1951), Amarillo Col

lege (Dallas Times Herald, October 2, 1951) and several

other junior colleges (The Houston Informer, December

5, 1951) have all found that the admission of Negroes was

2 1

possible without any adverse effect upon interracial rela

tions. Quite the contrary. The Austin Statesman of No

vember 14, 1950, reported the white students at Southern

Methodist University advised the president that “ SMU

student opinion favors admitting Negroes to the school.”

The University of Arkansas has accepted Negroes for

LL.B. and M.D. degrees. Little Rock Arkansas Gazette,

July 1, 1951; New York Post, August 24, 1948. Notwith

standing the fact that the University of Florida has thus

far refused to admit Negroes, the Florida Student Gov

ernment Association, an organization of student leaders

representing all colleges and universities in the State,

unanimously passed a resolution calling for an immediate

end to racial segregation in the State’s institutions of

higher learning. Miami Herald, May 6, 1951. The Uni

versity of Kentucky since 1949 has enrolled Negro stu

dents. New York Herald Tribune, June 23, 1949. By

July 1950, twelve Negroes were attending classes at the

University and “ [t]hey took their places quietly in the

student body without any open hostility.” Dawkins, Ken

tucky Outgrows Segregation, The Survey, July 1950. Pri

vate educational institutions have followed the lead of the

University of Kentucky. Berea College led the way. Three

Roman Catholic colleges in Louisville, Nazareth, Ursuline

and Bellarmine Colleges, immediately followed suit. Next

to fall in line was the University of Louisville with a stu

dent body of seven thousand. Southern Baptist Theologi

cal Seminary and Louisville Theological Seminary now

also admit Negroes on an unsegregated basis.

In July 1950, the first Negroes were admitted to the

University of Missouri and less than two years later a

Negro was appointed to the faculty. St. Louis Post-

2 2

Dispatch, July 7, 1950; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April

17, 1952. St. Louis University has admitted Negroes to

all its facilities for the past few years. They have been

fully integrated into the University program with no

unhappy results. During the academic year 1950-51, a

total of 351 Negro students was enrolled and there were

five Negro faculty members. The experience of institu

tions like St. Louis University has demonstrated that the

admission of Negro students poses no problem of accept

ance by white students. Morisey, A New Trend in Private

Colleges, New South, Aug.-Sept. 1951. Another private

university in St. Louis, Washington University, admits

Negroes to all its branches and schools. St. Louis Post-

Dispatch, May 11, 1952. Its experience has been identical

with that of St. Louis University.

In July 1951, the University of North Carolina ad

mitted its first Negro student. Washington Times-Herald,

July 17, 1951. The following September, six additional

Negro students attending the University, were excluded

from the regular student cheering section at a football

game. When the entire student body protested this action

by the University authorities, it was quickly reversed.

New York Herald Tribune, September 28, 1951.

Since 1951, the University of Virginia has been ad

mitting Negro students and “ the formerly 'all-white’

schools which have accepted Negro students have found

that their presence creates no special problem” . Rich

mond News Leader, September 25, 1952.

The College of William and Mary, which next to Har

vard University is the oldest of the country’s colleges,

has admitted two Negro students, both of whom are

attending regular day classes. According to President

23

Chandler, “ [t]he presence of these two Negro graduate

students has not created any special problems on the

campus.” Ibicl.

By July 1951, there were approximately one thousand

Negro students in previously “ all-white” institutions of

higher education in the South. “ They have encountered

virtually no open objection to their presence.” Saveth,

The Supreme Court and Segregation, The Survey, July

1951.

Just as the admission of Negroes to formerly “ all-

white” colleges and universities has created no friction

or other difficulties, so too experience has proved that in

tegration of white and Negro children at the elementary

and high school levels can be aeieved without incident.

In the State of New Mexico where segregation is al

lowed, though not required, in the public schools, the town

of Carlsbad maintained separate schools for the two races

until 1951. Following the refusal of the State School

Board to accredit the inferior Negro high school, the local

school authorities voted to admit Negroes to the “ white”

school. ‘ ‘ Carlsbad white students approved the move. The

1951 graduating class and the high school senior council

voted unanimously to welcome the Negro students. The

junior and senior class and faculty members were 95 per

cent in favor of it.” Santa Fe New Mexican, September 2,

1951. The integration has not caused a single untoward

incident to date. Furthermore, racial segregation was

abolished in Alamagordo’s public schools in August of

this year and the first Negro teacher was hired to teach

in that New Mexico city’s integrated public schools. There

has been no disharmony as a result of either action.

24

Racial segregation in public schools is not required in

Arizona. Local school boards are free to determine

whether or not they will maintain a dual educational

system. Under this local option provision, segregation has

been abandoned in the public schools of every city and

town in the State except Phoenix. The transition from

segregation to integration was made in all these communi

ties without any difficulty.

Despite the fact that segregation in public schools has

been banned in Illinois for many years, segregation was.

the practice in most of the southern counties. A 1949

State statute provided that, no State funds should be made

available to any school district where racial segregation

of students is practiced. This statute led to a movement

to abolish segregation in the southern communities of

Illinois. Notwithstanding an 85-year-old policy of racial

segregation in the public schools of East St. Louis, the

local board of education abandoned segregation and

adopted a policy of integration. There was “ no indication

of any organized resistance to the change” which was

effected without incident. The New York Times, January

30, 1950. Segregation in public schools was also abandoned

in Harrisburg (Chicago Sun-Times, September 26, 1950),

in Alton, a stronghold of racial discrimination even dur

ing World War II (Pittsburgh Courier, December 1, 1951),

and in Cairo at the southernmost tip of the State.

A similar process of uneventful integration is under

way in southern Ohio. In Glendale, a town about fifteen

miles from the Kentucky border, segregation in the public

schools was ended in October of this year when the local

board of education was advised that exclusion of Negro

pupils from a formerly “ all-white” school violated the

25

Constitution. In Dayton, the school hoard abolished segre

gation in the use of two swimming pools at Roosevelt

High School on June 22, 1950. Dayton Journal Herald,

June 23, 1950.

New Jersey is another State which, while normally

considered a Northern State, has a long-standing tradition

of racial segregation in its southern regions. In Novem

ber 1947, the people of New Jersey adopted a new State

Constitution which prohibited any person from being

“ segregated in the militia or in the public schools, because

of religious principles, race, color, ancestry or national

origin” . When this Constitution was adopted, cynics re

marked that the clause against racial segregation was an

excellent statement of principle but they predicted that

segregation would not be eliminated for at least a genera

tion. In 1948, the New Jersey Department of Education

made a survey of the 52 school districts in the State which

were reported to practice segregation in one form or an

other. It found that in 43 districts, segregation was im

posed by the school authorities. These districts ranged in

size from rural areas with one-room schools to large cities

with many schools. The end of the school year 1950-51

saw the complete elimination of segregation in 39 of the

43 school districts involved. In the other 4 districts, steps

had by that time been taken and building proposals were

underway which would bring about complete integration

in the near future. The report of the New Jersey Depart

ment of Education states:

A most significant factor in this transition is that

it has been done with a minimum of friction and a

maximum of good will.

Another important factor has been the success with

which colored teachers, who formerly taught classes

26

consisting of all colored children, have been employed

to teach classes of mixed races. While many indi

vidual examples could be cited, one in particular bears

mentioning. The one in question contained the only

junior high school operated on a segregated basis.

This junior high school was a fairly large institution

and naturally existed in a good sized city. Today, the

student body of this school is approximately one-third

Negro and two-thirds white. The teachers who for

merly were teaching all-Negro junior high school

classes have been completely integrated into the new

setup and include teachers of all regular and special

subjects. The morale of both the student body and

faculty is excellent. Biennial Report for the Years

July 1, 1949, to June 30, 1951, State of New Jersey,

Department of Education, Division Against Discrimi

nation 12, 13.

On the basis of the accumulated experience, instances

of which we have described above, we are convinced that

integration can and will be accomplished in the public

schools of the South without “ bloodshed and violence”

if the law enforcement agencies, federal or local, demon

strate that they will not tolerate breaches of the peace or

incitement. Americans are law abiding people and abhor

klanism and violence.

Segregation Is An Economic Waste

There is another cogent reason that this Court should

speak out clearly and definitively now. Since the ‘ ‘ separate

but equal” doctrine in public education will have to be

abandoned ultimately, it should be abandoned sooner

rather than later, to forestall the wasteful expenditure by

many States of huge sums of money to build segregated

schools when that money could be used more economically

and enduringly to build and improve public schools where

they will provide the greatest good for the greatest num

ber. This we believe is a necessary consequence of the

constitutional requirement that the State must grant each

person equal protection of its laws.

27

The President’s Committee on Civil Rights, in its his

toric report, To Secure These Rights (1947), states:

The South is one of the poorer sections of the country

and has at best only limited funds to spend on its

schools. With 34.5 percent of the country’s popula

tion, 17 southern states and the District of Columbia

have 39.4 percent of our school children. Yet the

South has only one-fifth of the taxpaying wealth of

the nation. Actually, on a percentage basis, the South

spends a greater share of its income on education than

do the wealthier states in other parts of the country.

(63)

The South has been struggling under a heavy financial

burden to support its educational system, with the Negro

schools admittedly inferior to the white. The southern

States would have to expend over one and one-half billion

dollars to bring the Negro schools to the level of the

“ white” schools and, in addition, approximately eighty-one

million dollars annually just to maintain parity. Charles

H. Thompson, Dean, Graduate School of Howard Univer

sity, Letter to the Editor, The New York Times, April 6,

1952. This additional burden is beyond the capacity of

the South to bear. Bond, in Education of the Negro in the

American Social Order (1934) sums this up:

If the South had an entirely homogeneous population,

it would not be able to maintain schools of high

quality for the children unless its states and local

communities resorted to heavy, almost crushing rates

of taxation. The situation is further complicated

by the fact that a dual system is maintained. Con

sidering the expenditures made for Negro schools, it

is clear that the plaint frequently made that this dual

system is a burden is hardly true; but it is also_ clear

that if an honest attempt were made to maintain

“ equal, though separate schools” , _thc_ burden would

be impossible even beyond the limitation of existing

poverty. (231)

28

Public schools should be planned and erected as part

of the development of the total community. They should

be built in those areas that have expanding populations

and needs for such facilities, rather than in opportunistic

response to random law suits or threats of law suits, as is

now the case in many southern States.

Conclusion

The United States is now engaged in an ideological

world conflict in which the practices of our democracy are

the subject of close scrutiny abroad. We cannot afford,

nor will the world permit us, to rest upon democratic

pretensions unrelated to reality.

The people of other lands listen not only to our Voice

of America which quite properly extols the virtues of

democracy; they listen to broadcasts from Communist

sources as well. We know that our enemies seize eagerly

upon the weaknesses of our democracy and, for propa

ganda purposes, magnify, exaggerate and distort hap

penings in the United States. Not so well known, although

possibly more significant, is that the liberal and conserva

tive press abroad is constantly comparing our declara

tions and statements about democracy with our actual

practices at home. Domestic incidents are noted and com

mented upon. Our discriminatory practices in education,

in employment, in housing, have all been the subject of

much adverse press comment in those foreign countries

which we are trying to keep in the democratic camp.

While McGee v. Mississippi, 40 So. 2nd 160 (1949), was

the subject of some considerable comment in Communist

circles here and elsewhere, the Paris office of the American

29

Jewish Committee assembled characteristic press comment

from liberal, conservative and Catholic European news

papers :

Semailles, a liberal Marseilles newspaper, said on May

18, 1951:

In associating ourselves with the United States in the

defense of liberty, we have included in the notion of

liberty, a respect for all human beings, the notion of

the common fraternity of all men. And it appears

that in this association, we, too, have much to bring.

What the world awaits from us is not cannons and

atomic bombs, but the permanent and vigilant affirma

tion of the inalienable right of all men to be judged

according to their acts and not according to the color

of their skin or the latitude in which they were born.

Otherwise, where is the difference between our enemies

and ourselves ?

An editorial, entitled “ An American Tragedy” , in the

Vienna Arbeiter-Zeitung, one of the staunchest anti-Com-

munist publications in Europe, said on February 4, 1951:

The Communist reply to accusations made about the

injustices and cruelties of their dictatorship, of forced

labor, of the arbitrariness of their courts and their

violation of human dignity, by pointing to the in

sincerity of American democracy which permits racial

persecution and deprives millions of human beings of

their equal rights on the basis of the color of their

skin.

One cannot appear before the world as a fighter for

freedom and right when one is unable to eliminate

injustice in one’s own house.

L ’Aube, Paris organ of the Popular Republican Move

ment (MRP), the second largest political party in France,

led by Georges Bidault and Foreign Minister Robert Schu-

man, in its May 9, 1951, issue said:

30

How much does a Negro weigh in a world where

people of all colors are struggling with the bitter

forces of nature and societies? Why is there so much

noise about a trial which after all is an internal affair,

not only of the United States of America, but of one

of its states? He weighs exactly that of all those

whose lot it is to protest an injustice. And the in

justice in this instance has as its name, racism. Our

reaction to injustice does not depend on the region of

the world where the wrong was committed. It is the

more bitter to know that it took place in a continent

which gave for liberty enough of its sons not to

deliver up to hatred of a poor Negro; that is what

weighs heavily.

On April 7, 1950, the Cologne Welt Tier Arbeit, official

publication of the anti-Communist German trade unions,

carried an article entitled, “ The Negro Question in the

IT. S.” That article contained the following significant

language:

In recent weeks, one found in the German press the

following items: In Frankfurt-am-Main the proprietor

of a cafe was fined 600 DM by American Occupation

Authorities because he had ejected two colored Ameri

can soldiers from his establishment. In Washington,

the Capital of the IJ. S. A., Doctor Bunche, who made

a name for himself as the UN intermediary in Pales

tine, was refused admittance to a movie house because

he was colored. He then went to another movie house

where he spoke French and was admitted because it

was believed he was a foreigner. In the one case, the

American authorities want foreigners to treat every

colored soldier with dignity as an American citizen

and punish any transgression of this principle. On

the other hand, world-famous leaders of the colored

population are deprived of their full equality. How

are these two attitudes to be reconciled? It is only

too natural that the average European can make no

sense of such contradictions. The racial attitudes in

the U. S. have no parallel in the entire world.

31

And finally, we have the following quotation from the

liberal Le Matin of Antwerp, Belgium, in May 1951:

The crime of racism is odious. And, without doubt,

the world will never know true peace while there exist

nations, peoples or races that believe themselves su

perior to other nations, peoples or races. It is a pain

ful declaration to make at the moment when our

American friends are presenting themselves in the

United Nations as the sturdy defenders of the free

world.

Legally imposed segregation in our country, in any

shape, manner or form, weakens our program to build

and strengthen world democracy and combat totalitarian

ism. In education, at the lower levels, it indelibly fixes

anti-social attitudes and behavior patterns by building

inter-group antagonisms. It forces a sense of limitation

upon the child and destroys incentive. It produces feel

ings of inferiority and discourages racial self-appreciation.

32

For all of the reasons urged herein, State-imposed racial

segregation in public schools, denies to the appellants

herein, and to all similarly situated Negro children, equal

protection of the laws in every meaningful sense of those

words.

The judgment of the court below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Edwin J. Lukas,

A rnold Forster,

A rthur Garfield Hays,

Frank E. Karelsen,

of the New York Bar,

Leonard Haas,

of the Georgia Bar,

Saburo Kido,

of the California Bar,

W aldo B. W etmore,

of the Kansas Bar,

Attorneys for Amici Curiae.

T heodore Leskes,

Sol R abkin,

of the New York Bar,

of Counsel.

November 15, 1952

33

APPENDIX

American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union is a private or

ganization composed of individual citizens. It is devoted

to supporting the Bill of Rights—for everybody. Founded

in 1920, it has, day in and day out, actively championed

the three-fold cause of civil liberties, the heart and core

of democratic government, as set forth in the Constitution

and the Declaration of Independence: (1) Government

by the people, grounded on freedom of inquiry and ex

pression—speech, press, assembly and religion—for every

body; (2) specific rights guaranteed to the people, such

as due process and fair trial—for everybody; and (3)

equality of the people before the law—for everybody,

regardless of race, color, place of birth, position, income,

political opinions, or religious belief.

The Union has no cause to serve other than civil liber

ties. It is dedicated simply and solely to furthering the

actual practice of democracy. It defends the civil liberties

of everybody, including those whose anti-democratic opin

ions it abhors and opposes, like Communists, Nazis, Fas

cists and Ku Klux Klanners.

34

The American Ethical Union is a national association

of Societies for Ethical Culture. Its purpose is to bring

into close fellowship of thought and action existing Ethical

Societies and to promote the establishment of new socie

ties. It is thus devoted, on a national scale, as is each

society in its local setting, to the promotion of the knowl

edge, the love and the practice of the right in all the rela

tionships of life. It asserts the supreme importance of the

ethical factor in all the relations of life and affirms the

belief that the greatest spiritual values are to be found in

man’s relationship to man. Through its religious and edu

cational programs it seeks to make the individual more

adequate in his personal relationships and better able to

contribute to the life of his community. The Ethical So

ciety has as one of its objectives the inspiring words of

St. Paul: “ He has made of one blood all nations of men to

dwell on the earth.”

American Ethical Union

35

The American Jewish Committee is a corporation cre

ated by an Act of the Legislature of the State of New

York in 1906. Its charter states:

The object of this corporation shall be to prevent the

infraction of the civil and religious rights of Jews, in

any part of the world; to render all lawful assistance

and to take appropriate remedial action in the event

of threatened or actual invasion or restriction of such

rights, or of unfavorable discrimination with respect

thereto . . .

During the forty-six years of its existence it has been

one of the fundamental tenets of the organization that the

welfare and security of Jews in America depend upon the

preservation of constitutional guarantees. An invasion of

the civil rights of any group is a threat to the safety of all

groups.

For this reason the American Jewish Committee has

on many occasions fought in defense of civil liberties

even though Jewish interests did not appear to be spe

cifically involved.

American Jew ish Committee

36

Anti-Defamation League

of

B’nai B’rith

B ’nai B ’rith, founded in 1843, is the oldest civic or

ganization of American Jews. It represents a member

ship of over 350,000 men and women and their families.

The Anti-Defamation League was organized in 1913, as a

section of the parent organization, in order to cope with

racial and religious prejudice in the United States. The

program developed by the League is designed to achieve

the following objectives: to eliminate and counteract

defamation and discrimination against the various racial,

religious and ethnic groups which comprise our American

people; to counteract un-American and anti-democratic ac

tivity; to advance goodwill and mutual understanding

among American groups; and to encourage and translate

into greater effectiveness the ideals of American democ

racy.

37

The Japanese American Citizens League is the national

organization of Americans of Japanese ancestry. Estab

lished in 1930, its story is an account of a group of young

Americans treasuring their birthright of American citizen

ship, defending it and seeking to be worthy of it. Although

its membership is composed primarily of Americans of

Japanese ancestry, membership is open to all Americans

who believe in its principles.

The purpose of the organization is to promote good

citizenship, protect the rights of Americans of Japanese

ancestry, and acquaint the public in general with this group

of citizens toward their full acceptance into American life.

The twin mottoes of “ For Better Americans in a Greater

America” and “ Security Through Unity” express this

purpose.

Japanese American Citizens League

38

Unitarian Fellowship for Social Justice

The Eev. Dr. John Haynes Holmes and a group of other

Unitarian clergymen established the Unitarian Fellowship

for Social Justice in 1908. They sought “ to sustain one

another in united action against social injustice and in the

realization of religious ideals in present-day society. ’ ’ Dr.

Holmes served for three years as the Fellowship’s first

president.

The Fellowship concerns itself especially with freedom

of conscience, the rights of minorities, the defense of public

education, and substantial efforts to strengthen the United

Nations and to plan for peace.

The Fellowship participates in the United Unitarian

Appeal for its funds, and it is affiliated with the American

Unitarian Association through the Association’s Depart

ment of Adult Education and Social Relations. The society

has individual members, organizational affiliates, and chap

ters throughout the United States and Canada in Unitarian

and liberal community churches.

[ 3434-3478— SOO— 12-52 ]