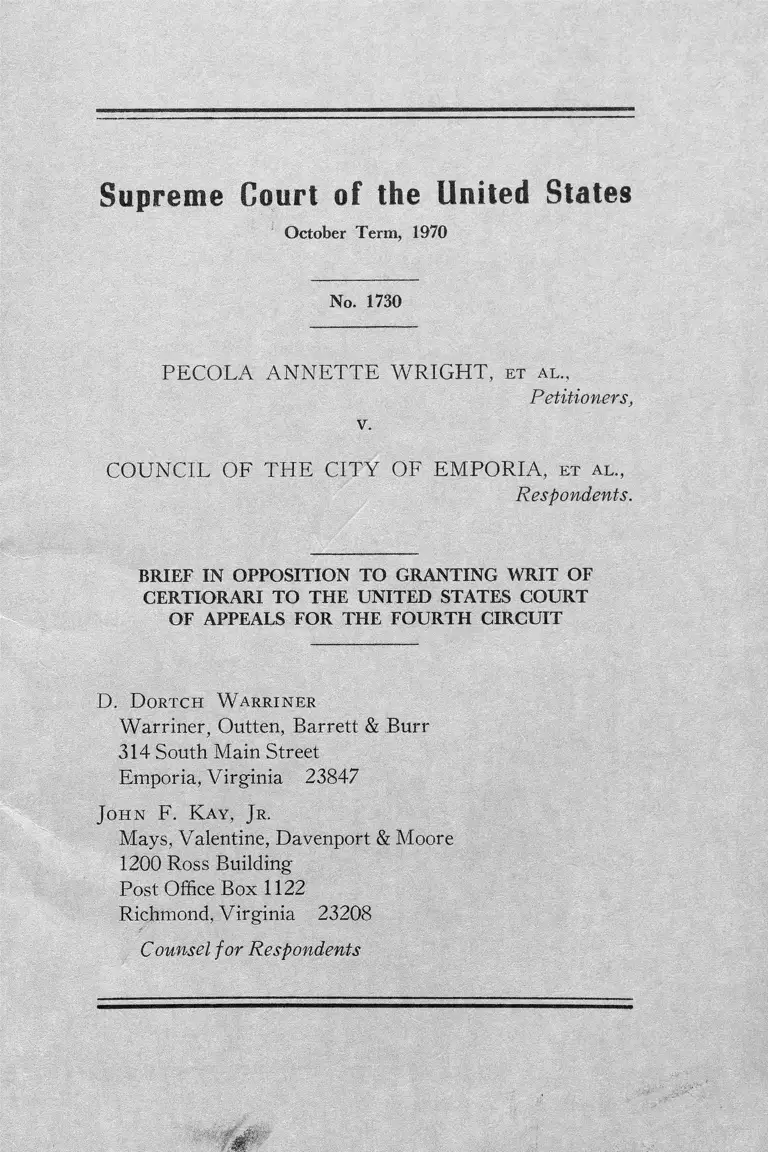

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia Brief in Opposition to Granting Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia Brief in Opposition to Granting Writ of Certiorari, 1970. e08ae68a-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ec08c842-fb71-4601-9ede-a8620e851823/wright-v-council-of-the-city-of-emporia-brief-in-opposition-to-granting-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1970

No. 1730

PECOLA A N N E TTE W RIG H T, et a l .,

v.

Petitioners,

COUNCIL OF TH E CITY OF EM PORIA, et a l .,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION T O GRANTING W R IT OF

CERTIORARI T O THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

D. D ortch W a rrin er

Warriner, Outten, Barrett & Burr

314 South Main Street

Emporia, Virginia 23847

Jo h n F. K a y , Jr .

Mays, Valentine, Davenport & Moore

1200 Ross Building

Post Office Box 1122

Richmond, Virginia 23208

Counsel for Respondents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

O pinions Below .................. ................ ................ —-........................... 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions I nvolved ............ 1

Q uestions Presented......................................... -..............................- 2

Statement ......................................................................................... 3

Reasons F or Denying W rit .......— ............................... — ........ 13

I. The Issues Involved Are Not Of Critical Importance

In The Process of School Desegregation Because Of

The Unique Structure of Local Government in Virginia 13

II. Decision Of The Court Of Appeals Below Is Not In

Conflict With Rulings Of This Court And Another

Court Of Appeals................. -......-.................. -.................... 17

1. Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968)

and Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

No. 281 O.T. 1970 ...................................... 17

2. Burleson v. County Bd. of Election Comm’rs, 432

F.2d 1356 (8th Cir. 1970) ............................... 20

III. Decision Of The Court Of Appeals Below Was Plainly

R ig h t.......................................... -........... -...................... -......... 21

Co n c l u s io n .............................................................................................. 22

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969) 21

Brown v. Board of Educ. of Topeka, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ....... 19

Burleson v. County Bd. of Election Comm’rs, 432 F.2d 1356 (8th

Cir. 1970) .............................................................................. 14, 17, 20

Page

Burleson v. County Bd. of Election Comm’rs, 308 F. Supp. 352

(E.D. Ark. 1970) ........................................ .......... ................. 20, 21

City of Richmond v. County Bd., 199 Va. 679, 101 S.E.2d 641

(1958) ............................................................................................... 15

Colonial Heights v. Chesterfield, 196 Va. 155, 82 S.E.2d 566

(1954) ................................................................................................ 15

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ..........10, 17, 18,

19, 21

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969) .... 14

Murray v. Roanoke, 192 Va. 321, 64 S.E.2d 804 (1951) ...... ......... 15

School Bd. v. School Bd., 197 Va. 845, 91 S.E.2d 654 (1956) .... 16

Supervisors v. Saltville Land Co., 99 Va. 640, 39 S.E. 704 (1901) 15

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., No. 281 O.T. 1970

13, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22

United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of E du c.,..... F.2d ........ ,

Nos. 14,929 and 14,930 (4th Cir. 1971) ................................ 14, 19

Constitution

Virginia, Constitution of

Art. IX , § 133 .............................................................. ........2, 5, 6, 16

Code

Virginia Code Annotated (1950) :

§ 15.104 (now 15.1-1005) ................................................... 2

§§ 15.1-978 through 15.1-1010 ........................ .......... _......... ........ 2

§ 15.1-982 ...................................................................................... 2

§ 15.1-1005 .................................................................................. is

§22-34 ................................................................................................. 6

§22-93 .......................................................................................2, s’ 16

§22-97 ...................................................................................... 6

§ 22- 100.2 ................................................................................................................. 6

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1970

No. 1730

PECO LA A N N E TT E W R IG H T, et a l .,

Petitioners,

v.

COUNCIL OF TH E C ITY OF EM PORIA, et a l ,,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO GRANTING W R IT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

OPINIONS BELOW

The petition accurately describes the opinions of the

courts below except that it indicates that Judge Sobeloff dis

sented in this case. Judge Sobeloff did not participate in the

appeal of this case from the District Court.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATU TOR Y

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

In addition to the constitutional provisions and statutes

referred to in the petition, the case involves:

2

1. V a . C o n st , art. ix , § 133, which is set forth in the

appendix to this brief in opposition at R.A. 1.*

2. V a . C ode A n n . § 22-93 (1950), which provides:

The city school board of every city shall establish

and maintain therein a general system of public free

schools in accordance with the requirements o f the

Constitution and the general educational policy o f the

Commonwealth.

3. V a . C ode A n n . §§ 15.1-978 through 15.1-1010

(1950), which relate to the transition of towns to cities in

the Commonwealth of Virginia. V a . Code A n n . § 15.1-982

(1950), as in effect on July 31, 1967, is set forth in part at

R.A. 2.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The preliminary statement contained in the section of

the petition entitled “ Questions Presented” (P. 2) is in

accurate and incomplete and thus provides a misleading

foundation upon which the presentation of the questions

involved is based.

The City of Emporia is not located within Greensville

County. While it is surrounded by Greensville County, the

City is politically, governmentally, and geographically in

dependent of the County.

Additionally, the one sentence summaries of the reasons

for the holdings of the courts below are, of course, incom

plete and accordingly they sacrifice accuracy for brevity.

* The following designations will be used in this brief :

R.A.— Appendix to respondent’s brief in oppostion

P. — Petition for writ of certiorari

P.A.— Appendix to petition for writ of certiorari

3

The questions involved are:

1. Because of the unique independent status of cities in

the Commonwealth of Virginia, are the issues here involved

of such nationwide importance as to warrant a review and

decision by this Court?

2. May the City of Emporia, Virginia, an independent

political subdivision of the Commonwealth o f Virginia,

which was created in 1967 under long-standing state law

for reasons unrelated to public school desegregation, operate

a racially unitary and superior quality school system in

dependent of the County o f Greensville, which is a separate

independent political subdivision of the Commonwealth?

3. Was the Court of Appeals correct in deciding that

the constitutionally protected rights of the petitioners would

not be violated if the City of Emporia operated a unitary

school system independent of that operated by the County

of Greensville, which decision was based upon the factual

findings of the District Court?

STATEM ENT

In their “ Statement” petitioners call attention to the

fact that this is “ one of three cases decided together by the

Court o f Appeals involving the relationship between de

segregation and the creation of new school districts” (P . 3).

While this is true, it is important to note at the outset that

there are various significant differences between this case,

which involves a city in the Commonwealth of Virginia,

and the other two cases, which involve school districts in

the State of North Carolina. A detailed explanation of the

Virginia system of local government is contained in a

later section of this brief. At this point, however, attention

is called to the fact that the City of Emporia was created

under long-standing Virginia law and is completely in

dependent of the County of Greensville for all purposes,

4

save one.1 On the other hand, the North Carolina school

districts were created pursuant to special acts o f the North

Carolina General Assembly adopted in 1969 and the areas

involved are still a part o f the county or counties out of

which they were carved for all governmental purposes other

than education.

On pages 4 and 5 of the petition, footnote 4, the back

ground of the litigation is set forth. Some elaboration is

necessary. The evidence was uncontradicted that the moti

vating factor behind the transition of Emporia from a town

to a city was the desire of Emporia’s elected officials to have

the city receive the benefit o f the state sales tax that had

recently been enacted and to eliminate other economic in

equities. There has been no charge by the plaintiffs that the

decision to become a city was in any way motivated by

the school desegregation situation. There was no finding by

the District Court to impugn the motives or purposes of

the City in effecting this transition. The Court of Appeals

so indicated (P .A . 4a). Thus, it is clear that this is not a

case in which an area has been “ carved out” for the purpose

of avoiding school desegregation.

Further, petitioners indicate that at the time Emporia

became a city it was free to operate its own independent

school system, but chose not to do so. The courts below

were satisfied that Emporia considered so doing at that

time, but determined that such was not practical immediate

ly after transition.

The Court of Appeals stated:

Emporia considered operating a separate school sys

tem but decided it would not be practical to do so im

mediately at the time of its independence. There was

an effort to work out some form of joint operation with

1 It shares with the County the cost of the circuit court and its

clerk, the commonwealth’s attorney and the sheriff.

5

the Greensville County schools in which decision mak

ing power would be shared. The county refused. Em

poria finally signed a contract with the county on

April 10, 1968, under which the city school children

would attend schools operated by the Greensville

County School Board in exchange for a percentage of

the school system’s operating cost. Emporia agreed to

this form of operation only when given an ultimatum

by the county in March 1968 that it would stop educat

ing the city children mid-term unless some agreement

was reached.

The District Court held:

Ever since Emporia became a city consideration has

been given to the establishment of a separate city

system. A second choice was some form of joint oper

ating arrangement with the county, but this the county

would not assent to. Only when served with an “ulti

matum” in March of 1968, to the effect that city stu

dents would be denied access to county schools unless

the city and county came to some agreement, was the

contract of April 10, 1968, entered into.

The contract of April 10, 1968, was limited to a term of

four years expiring on July 1, 1971 (P .A . 73a).

On pages 6 and 7 o f the petition, footnote 6, petitioners

undertake to explain the Virginia system of school divisions

and school districts. They erroneously state that when

Emporia became a city “ it could not operate a separate

school system unless it was named a separate school divi

sion by the State Board.” The Constitution of Virginia

requires that supervision of schools in each county and

city shall be vested in a school board. V a . Co n st , art. ix ,

§ 133 (R .A . 1). The Code of Virginia requires that the

city school board of every city shall establish and maintain

therein a system of schools. V a . C ode A n n . § 22-93 (1950)

6

{supra at 2 ). It sets forth the duties and powers o f the

city school boards. V a . C ode A n n . § 22-97 (1950) (P .A .

91a). While it is possible for a city and a county to be in

one school division, each has its own school district, its own

school board and each operates its own system. In such

cases the boards are required to meet together only for the

purpose o f appointing a superintendent of the division who

serves both boards but who administers each system separ

ately. V a . C ode A n n . § 22-34 (1950) (P .A . 87a). The

Constitution of Virginia permits supervision of such divi

sion to be vested in a single school board in which event

the separate school boards cease to exist. V a . C o n st , art.

ix , § 133 (R .A . 1). The Code provides that such may

occur only upon approval of the school board and the gov

erning body of each of the political subdivisions involved.

V a . C ode A n n . § 22-100.2 (1950) (P .A . 97a). The courts

below found that the County refused to agree to a jointly

operated system (P .A . 4a, 75a). It is therefore clear that

under state law the City of Emporia has the power and duty

to operate its own system of schools as a separate school

district. The City sought to be constituted a separate divi

sion only so that it could employ its own superintendent

(Transcript o f the Proceedings, December 18, 1969, at 27).

On pages 7, 8, and 9 of the petition, reference is made

to the reasons o f the City for attempting to establish its

own system and to the findings of the District Court at the

time it granted the temporary injunction on August 8, 1969.

At that same hearing, officials of the City also testified

that the City’s primary motive in seeking to establish its

own unitary system was to afford better educational op

portunities for its children than would be provided by the

County of Greensville (Transcript o f the Proceedings,

August 8, 1969, at 120, 163, 164). However, the best sum

mary of the purposes o f the City is provided by the opinion

7

of the District Court on March 2, 1970, after it had heard

the evidence at the hearing on the permanent injunction in

December 1969:

The city clearly contemplates a superior quality edu

cational program. (P .A . 67a)

* * *

Emporia’s position, reduced to its utmost simplicity,

was to the effect that the city leaders had come to the

conclusion that the county officials, and in particular

the board of supervisors, lacked the inclination to make

the court-ordered unitary plan work. The city’s evi

dence was to the effect that increased transportation

expenditures would have to be made under the existing

plan, and other additional costs would have to be in

curred in order to preserve quality in the unitary

system. The city’s evidence, uncontradicted, was to

the effect that the board of supervisors, in their opinion,

would not be willing to provide the necessary funds.

(P .A . 75a) * * *

The Court does find as a fact that the desire of the

city leaders, coupled with their obvious leadership

ability, is and will be an important facet in the success

ful operation of any court-ordered plan. (P .A . 76a)

5̂

This Court is satisfied that the city, if permitted,

will operate its own system on a unitary basis. (P .A .

77a)

It is these findings of the District Court, which were

made after the evidence was fully developed, that are

controlling. Obviously, they supersede any conflicting find

ings made after the expedited and peremptory hearing on

the temporary injunction.

On page 11 of the petition, petitioners state that the

District Court concluded that the “ establishment of separ

8

ate systems would plainly cause a substantial shift in the

racial balance.” The facts upon which this conclusion is

based are these:

Combined system .............. . 66% black; 34% white

Separate systems

County ........................... 72% black; 28% white

C ity .................................. 52% black; 48% white

(P .A . 6a)

Petitioners then state that “ the District Court concluded

that the operation of separate school systems would have

serious adverse impact on the provisions o f the plaintiffs’

constitutional rights” (emphasis added) (P . 11). The Dis

trict Court simply did not say that. Rather it said:

This Court is most concerned about the possible adverse

impact o f secession on the effort, under Court direction,

to provide a unitary system to the entire class of plain

tiffs. (Emphasis added.) (P .A . 78a)

It also said:

But this [operation of a unitary system by the City]

does not exclude the possibility that the act o f divi

sion might have foreseeable consequences that this

Court ought not to permit. (Emphasis added.) (P .A .

77a)

It is clear that the District Court considered any adverse

effects o f separate systems to be purely speculative.

Petitioners next proceed to summarize the majority opin

ion of the Court of Appeals (P . 12, 13). That summary is

incomplete and therefore misleading. On page 13 of the

petition, petitioners have selected statements from the opin

ion of the Court o f Appeals and have placed them together

in a manner that does not accurately depict the context in

9

which they were made. The majority did not conclude that

Emporia would not be a “ white island” because “ there will

be a substantial majority of black students in the county

system.” It concluded that Emporia would not be a white

island because of the obvious and uncontradicted fact that

it will have a system composed of a majority of black

students. It did not conclude that “ the effect of separation

does not demonstrate that the primary purpose of the

separation was to perpetuate segregation” solely because

of the racial makeup of the two systems. It reached this

conclusion based on all the findings of the District Court

with respect to all the evidence presented.

Next, the petitioners state that “ [Sjince the district court

made no explicit ‘finding of discriminatory purpose/ and

because the school district officials advanced non-racial mo

tives for the creation of a separate district,” the majority

held the injunction by the District Court to have been im-

providently entered (P. 13). Again, the decision of the

majority was not based merely on those grounds; rather, it

was based on the record as a whole. It should be pointed out

that not only did the Court of Appeals state “ that there

was no finding of discriminatory purpose,” but it also stated

that “ the [district] court noted its satisfaction that the city

would, if permitted, operate its own system on a unitary

basis” (P .A . 8a).

The following is a summary of what the Court o f Ap

peals did, in fact, hold.

It stated that if the shift in racial balance “ is great

enough to support an inference that the purpose” o f the

new school district “ is to perpetuate segregation,” the new

district must be enjoined (P .A . 2a).

It stated:

The creation o f new school districts may be desirable

and/or necessary to promote the legitimate state inter

10

est o f providing quality education for the state’s chil

dren. The refusal to allow the creation of any new

school districts where there is any change in the racial

makeup of the school districts could seriously impair

the state’s ability to achieve this goal.

* * *

If the creation o f a new school district is designed to

further the aim of providing quality education and is

attended secondarily by a modification of the racial

balance, short of resegregation, the federal courts

should not interfere. If, however, the primary purpose

for creating a new school district is to retain as much

o f separation of the races as possible, the state has

violated its affirmative constitutional duty to end state

supported school segregation. (P .A . 3a)

The Court o f Appeals then proceeded to examine the

evidence and the findings of the District Court on the ques

tion of the purpose of Emporia in becoming a city and in

seeking its own school system. However, o f equal im

portance, it also examined the effect o f the so-called separa

tion2 of the school systems. It is impossible to determine the

subjective purpose without considering the objective effect.

First, the Court of Appeals found that the purpose of

Emporia in attaining city status was not to prevent or

diminish integration. The Court stated that at the time

Emporia became a city, July 31, 1967, “ a freedom of choice

plan approved by the district court” was in effect and the

decision in Green v. County School Board, of New Kent

Comity, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), “ could not have been antici

pated by Emporia, and indeed, was not envisioned by this

2 Actually, this case involves “ consolidation” rather than “ separa

tion” since the systems were legally separated when Emporia became

a city on July 31, 1967. Only because of the contract which expires on

June 30, 1971, under its own terms, did Greensville County educate

children of Emporia in its system.

11

court.” (P .A . 4a). The purpose of Emporia in becoming a

city was to receive the benefits of the newly enacted sales

tax and to eliminate other economic inequities (P .A . 4a;

Transcript of the Proceedings, August 8, 1969, at 118,

119).

Next, the Court of Appeals examined the purpose and

effect of Emporia’s decision in 1969 to operate its own

system. After pointing out that if Emporia did so the City

would have a majority of black students in its system and

that a six percent shift of the racial balance of the Greens

ville County school system would be created, the Court

stated:

Not only does the effect of the separation not demon

strate that the primary purpose o f the separation was

to perpetuate segregation, but there is strong evidence

to the contrary. Indeed, the district court found that

Emporia officials had other purposes in mind. (Empha

sis added.) (P .A . 6a)

The Court o f Appeals then referred to the evidence of

Dr. Neil H. Tracey, Professor of Education at the Univer

sity of North Carolina, who testified that his studies were

made with the understanding that it was not the intent of

the City to resegregate8; that an examination o f the pro

posed budget for the Greensville County schools indicated

that it not only would not provide the funds required for in

creased transportation expenses necessitated by the pairing

plan, but it would not provide the funds to keep up with the

increased costs o f operation due to inflation; that the tent

ative budget adopted by Emporia would provide increased

revenues to increase the quality of education for its stu

dents ; and that the proposed system of Emporia would be

educationally superior to Greensville’s system (P .A . 7a). 3

3 Transcript of the Proceedings, December 18, 1969, at 68.

12

The Court o f Appeals pointed out that “ Emporia proposed

lower student teacher ratios, increased per pupil expendi

tures, health services, adult education, and the addition of a

kindergarten program.” (P .A . 7a).

The Court of Appeals then stated:

In sum, Emporia’s position, referred to by the dis

trict court as “ uncontradicted,” was that effective inte

gration of the schools in the whole county would re

quire increased expenditures in order to preserve edu

cation quality, that the county officials were unwilling

to provide the necessary funds, and that therefore the

city would accept the burden o f educating the city

children (P .A . 7a).

Further, the Court of Appeals pointed out that because

of the unusual nature o f the organization of city and

county governments in Virginia under which counties and

cities are completely independent, Emporia had no repre

sentation on the governing body of the County or on the

school board of the County. Thus, neither Emporia nor its

residents have any means by which they can exert any

influence or control whatever with respect to the education

of the school children of the City (P .A . 7a, 8a). In conclu

sion, the Court of Appeals stated:

The district court must, of course, consider evidence

about the need for and efficacy of the proposed action

to determine the good faith of the state officials’ claim

of benign purpose. In this case, the court did so and

found explicitly that “ [t]he city clearly contemplates a

superior quality education program. It is anticipated

that the cost will be such as to require higher tax pay

ments by city residents.” 309 F. Supp. at 674. Notably,

there was no finding of discriminatory purpose, and

instead the court noted its satisfaction that the city

would, if permitted, operate its own system on a uni

tary basis (P .A . 8a).

13

The “ Statement” portion o f the petition concludes by

setting out rather extensive quotations from the dissenting

opinions o f Judges Sobeloff and Winter.4

REASONS FOR DENYING W RIT

I.

The Issues Involved Are Not Of Critical Importance In The Process

Of School Desegregation Because Of The Unique Structure Of

Local Government In Virginia.

Petitioners are not correct when they state on page 1S of

the petition that “ [T]his case arises out o f the repeated

failure of the County School Board o f Greensville County

to propose an acceptable desegregation plan.” Rather it

arises out of the effort of petitioners to restrain the inde

pendent City of Emporia from operating its own unitary

school system as all other cities in Virginia are permitted

to do.5

This case is not the usual desegregation suit involving

the constitutional validity of a desegregation plan ( e.g.,

Swaxnn v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Edvtc., No. 281

O.T. 1970).

It is not a case where school district lines have been

gerrymandered to affect the racial makeup of schools (e.g.,

4 Again, petitioners indicate that Judge Sobeloff dissented in the

Emporia case though he neither participated nor voted in it. If any

significance can be attached to his views so far as this case is con

cerned, then it should be noted that Judge Butzner, who likewise did

not participate in it, was a part of the majority in the United States v.

Scotland Neck City Bd. of E duc.,..... F .2 d ....... (4th Cir. 1971), and

must, therefore, be assumed to be in accord with the views of the

majority in the Emporia case.

5 The District Court found that Emporia contemplated operating

“ a superior quality educational program” (P .A . 67a) and would, if

permitted by the courts, “ operate its own system on a unitary basis”

(P .A . 77a).

14

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., 419 F.2d 920 (8th Cir.

1969) ).

It is not a case where a school district within a county

or city has been divided by carving out a new school district

consisting of primarily white students (e.g., Burleson v.

County Bd. of Election Comm’rs, 432 F.2d 1356 (8th Cir.

1970) ).

It is not a case where a new city or school district has

been created by a special act of a state legislature (e.g.,

United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Edwc.,......F.2d

......, Nos. 14929and 14930 (4th Cir. 1971)).

Rather it is a case in which the independent City of

Emporia, which became such on July 31, 1967, under gen

eral laws existing in Virginia since at least 18928, is seeking

to operate its own school system, independently of that of

the county of which it was a part prior to July 31, 1967, as

all other cities in Virginia are entitled to do.

The decision o f the Court o f Appeals in this case does not

constitute a precedent that would have wide spread appli

cation or effect in the area of school desegregation because

o f the unique structure of local government in Virginia and

because of the factual context from which the case arises.

In Virginia, counties and cities are independent of

each other politically, governmentally and geograph

ically. 6

6 The present Code of Virginia provides that a town upon attaining

a population of 5,000 may elect to become a city of the second class

for following the procedures set forth in the Code. Title 15.1, ch. 22,

Va. Code Ann. (1950), as amended. The law has been substantially

the same since at least 1892. Acts of Assembly, 1891-1892, ch. 595, at

934. Thus it is clear that the provisions under which the Town of

Emporia acted to become a city have long been a part of the law

in Virginia and were not enacted in any way as a result of the school

desegregation suits or for any other racial reasons.

15

City of Richmond v. County Bd., 199 Va. 679, 684, 101

S.E.2d 641, 644 (1958)

It is the only state in the United States having such a

statewide system of local government.7

In Murray v. Roanoke, 192 Va. 321, 324, 64 S.E.2d 804,

807 (1951), the Virginia court stated:

In Virginia, counties and cities are separate and

distinct legal entities. . . . Citizens of the counties have

no voice in the enactment of city ordinances, and con

versely citizens of cities have no say in the enactment

of county ordinances.

That this has been the law historically in Virginia is

demonstrated by Supervisors v. Saltville Land Co., 99 Va.

640, 39S.E . 74(1901).

This principle is applicable to a city that became such

under the provisions of the law providing for the tran

sition of towns to cities. In Colonial Heights v. Chesterfield,

196 Va. 155, 82 S.E.2d 566, 572 (1954), the Supreme

Court of Appeals held:

The town, upon becoming a city, separates from a

political subdivision of which it was a part and becomes

an independent political subdivision, except as to cer

tain joint services specified in Code, § 15.104 [now

§ 15.1-1005],

Schools are not listed among the services specified in

§ 15.1-1005— that section is limited to the sharing o f the

costs of the circuit court and its clerk, the commonwealth’s

attorney, and the sheriff.

The Constitution of Virginia has, since 1928, vested the

supervision of county schools in the county school boards

7 C. Bain, “ A Body Incorporate” — The Evolution of City-County

Separation in Virginia ix, 23, 27, 35 (1967) ; C. Adrian, State and

Local Governments 249 (2d ed. 1967).

16

and the supervision o f city schools in the city school boards.

V a . C o n st , art. ix, § 133 (R .A . 1).

Since at least 1919 the Code o f Virginia has affirmatively

required the city school boards to establish and maintain a

system of schools in each city of the Commonwealth. V a .

C ode A n n . § 22-93 (1950).

In School Bd. v. School Bd., 197 Va. 845, 91 S.E.2d 654

(1956), dealing with the transition of a town to a city, the

Supreme Court o f Appeals o f Virginia held that upon tran

sition the new city is required by law to maintain its own

school system.8

The Court of Appeals below stressed the importance of

the unusual nature o f local government in Virginia and

the fact that because o f it Emporia has no representation

on either the governing body or the school board of the

County of Greensville (P .A . 7a). I f Emporia were to be

compelled to remain tied to Greensville County, it would be

helpless to exert any influence or control with respect to the

school system attended by its children.

Since no other state has such a system of local govern

ment, this case is not o f nationwide significance.9

8 “As a town, Covington was a part of Alleghany County whose

public schools were operated by the county school board. When

Covington became a city it ceased to be a part of the county, became

completely independent governmental subdivision, and was required

by law to maintain its own school system,” 197 Va. at 847, 91 S.E.2d

at 656.

9 While the details of all the cases cited on page 17, footnote 10,

of the petition are not known to counsel for respondent, it is noted

that none arise from the State of Virginia. Because of the unique

structure of local government in Virginia, the Emporia case could

have little, if any, bearing on those cases. The case of Burleson v.

County Bd. o} Election Comm’rs., 432 F.2d 1356 (8th Cir. 1970),

it is distinguished on page 20 of this brief.

17

II.

Decision Of The Court Of Appeals Below Is Not In Conflict With

Rulings Of This Court And Another Court Of Appeals.

Petitioners assert that the decision of the Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit is in conflict with the decision

of this Court in Green v. County School Bd,, 391 U.S. 430

(1968), and with the decision of the Court o f Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit in Burleson v. County Bd. of Election

Comm’rs, 432 F.2d 1356 (8th Cir. 1970). Reference is also

made to the decision of this Court in Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., No. 281 O.T. 1970.

An analysis of those decisions reveals that there is no

conflict between them and the decision of the Court of

Appeals below. Rather it is in complete accord with the

principles enunciated by this Court in Green and in Swann.

In making such an analysis consideration must be given to

the facts of each case since principles of law cannot be

applied in the abstract.

1. G reen v . C o u n t y S chool Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968)

and S w a n n v . C h arlo tte -M eck len bu rg Bd. of

E duc ., No. 281 O.T. 1970

In Green this Court held that freedom of choice plans

could not be approved unless they result in the dismantling

of dual systems. It there held that such a plan was not

working in New Kent and thus could not be accepted.10

In Swann this Court examined the powers of district

courts to require busing o f children between attendance

10 New Kent County had only two schools, one on each side of the

county. There were 740 Negroes and 550 white students in the

system. After freedom of choice had been in effect three years, one

school remained all Negro and the other school had all the white stu

dents together with 115 Negro students.

18

zones of large metropolitan school systems as an aid to de

segregation.11

Several important principles were established by those

decisions with which the decision of the Court o f Appeals

below is in complete accord.

First, with respect to objectives, this Court held in Green

that a unitary, nonracial system of schools is the ultimate

end to be brought about (391 U.S. at 436) and in Swann

that the objective is to eliminate from public schools all

vestiges of state-imposed segregation (Slip Op. at 10).

In the instant case the City of Emporia would have a

unitary, nonracial system of public education composed of

approximately 52 percent black and 48 percent white. The

Court of Appeals (P .A . 6a) and the District Court (P .A .

74a, 75a) so found. The County of Greensville would also

have such a system composed of approximately 72 percent

black and 28 percent white (P .A . 6a).

Second, this Court held in Green (391 U.S. at 439) and

in Swann (Slip Op. at 23) that there is no one way to ac

complish the objectives and that each case must be judged

in light o f the circumstances present and the options avail

able.

In accordance with that principle, the Court o f Appeals

below recognized that flexibility in the operation o f the

school system is both desirable and permissible (P .A . 8a).

Third, this Court stated in Green that a plan which has

been adopted in good faith and which has the real prospect

of resulting in a unitary system “ at the earliest practicable

date . . . may be said to provide effective relief” (291 U.S.

at 439).

In Swann the Court recognized that at some point school

11 The Swann case did not involve the interchange of children be

tween independent school districts, but rather involved the inter

change of students between attendance zones contained in one school

system.

19

systems will be “ unitary” and that subsequently interven

tion by district courts should not be necessary in the absence

of a deliberate scheme to affect the racial composition of the

schools ( Slip Op. at 28).

Thus, it is clear that in two of the most recent decisions

by this Court in school desegregation cases the elements of

the “ good faith” and of the “ purpose” o f the local authori

ties are considered to be important factors in determining

the acceptability o f a course o f action. Even the dissenting

judge in this case and Judge Sobeloff in the Scotland Neck

case laid great emphasis upon the motive and purpose o f the

local authorities (P .A . 11a, 28a). Consideration by the

Court o f Appeals o f the purpose of Emporia in attempting

to set up its own system was clearly in accord with the

decisions of this Court. Based on the findings of the Dis

trict Court, the Court o f Appeals held that the primary

purpose of the separation was to provide better education

and that the local authorities acted in good faith (P .A . 6a,

8a).

It should also be noted that this Court in Brown II recog

nized that consideration by the courts o f the good faith of.

school authorities was both necessary and proper.12

Fourth, this Court in Green stated that school boards

must come forward with plans that promise realistically to

work now (291 U.S. at 438).

In Swann the Court said that a plan is to be judged by

its effectiveness (Slip Op. at 21).

The Court of Appeals below complied with the mandate

that a plan is to be judged by its effectiveness (P .A . 6a,

8a). While it stressed the importance of the purpose and

good faith o f the local authorities, it recognized that those

factors must be judged in light of results. It further recog

12 Brozvn v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955), at 299.

20

nized that whether a plan will work or be effective means a

good deal more than mathematical racial ratios.

In summary, the decision o f the Court of Appeals below

is in complete harmony with the decisions of this Court.

2. B urleson v . C o u n t y B d. of E lectio n C o m m ’rs, 432

F.2d 1356 (8th Cir. 1970)

In the Burleson case, by per curiam opinion, the Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit affirmed the decision of the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas.13

That case is clearly distinguishable upon its facts from

the Emporia case.

First, in Burleson the question was whether the Hardin

Area o f the Dollarway School District of Jefferson County,

Arkansas, would be permitted to secede from that particu

lar district and establish a new district within the same

county. Apparently, in addition to the county board of edu

cation, each school district had its own “ board of directors.”

For all purposes other than schools, it is assumed that the

Hardin Area would remain a part of Jefferson County. In

the instant case, the City o f Emporia, under the law of

Virginia, is already independent o f Greensville County'—

politically, governmentally, and geographically.

Next, in the Burleson case the district court found:

The population of the Area is almost exclusively

white. In the fall o f 1969 270 students residing in the

Area were in attendance in the schools o f the District,

and only 5 of those students were Negroes.

308 F. Supp. at 353.

In the instant case, slightly over 50 percent of the stu

13 308 F. Supp, 352 (E.D. Ark. 1970).

21

dents residing in Emporia are Negro. Thus, while the

Hardin system would be composed almost entirely of white

children, the Emporia system would be composed of almost

an equal number of Negro and white children.

In Burleson the district court held that

. . . as of this time and in the existing circumstances the

proposed succession cannot be permitted and will be

enjoined (Emphasis added).

308 F. Supp. at 358.

III.

Decision Of The Court Of Appeals Below Was Plainly Right.

This Court said in Swann that “ [O ] nee a right and a

violation have been shown,” the district court has broad

powers to remedy the wrong; that “ it is important to re

member that judicial powers may be exercised only on the

basis o f constitutional violation” ; and that “ [Jjudicial au

thority enters only when local authority defaults.” 14 It fur

ther said:

The basis o f our decision must be the prohibition of

the Fourteenth Amendment that no State shall “ deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protec

tion of the laws.”

Slip Op. at 13.

According to Green, the constitutional right o f the plain

tiff is to attend a unitary, nonracial system. According to

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19

(1969), at 21, it is the duty of local school authorities not to

operate a dual system based on race or color, and . . .

to operate as [a] unitary school system[s] within

which no person is to be effectively excluded from any

school because of race or color.

14 Swann, Slip Op. at 11.

22

Here, there has been no violation of the constitutional

rights of the plaintiffs as enunciated by this Court; likewise,

there has been no default by the Emporia authorities. There

has been no finding to the contrary. In fact, the District

Court found that the City would operate a unitary system

(P .A . 77a), and its previous order assures that such a

system will be operated in Greensville County.

Only if plaintiffs are entitled as a constitutional matter

to attend schools with a particular racial balance can it be

held that plaintiffs’ rights have been violated. Such a hold

ing would be contrary to the holding in Swann that:

If we were to read the holding of the District Court

to require, as a matter of substantive constitutional

right, any particular degree of racial balance or mix

ing, that approach would be disapproved and we would

be obliged to reverse. The constitutional command to

desegregate schools does not mean that every school in

every community must always reflect the racial compo

sition of the school system as a whole.

Slip Op. at 19, 20.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons respondents respectfully pray

that a writ o f certiorari be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

D . D ortch W a r r in e r

314 South Main Street

Emporia, Virginia 23847

Jo h n F. K a y , Jr .

1200 Ross Building

Post Office Box 1122

Richmond, Virginia 23208

Attorneys for Respondents

A P P E N D I X

VIRGINIA CONSTITUTION

§ 133. School districts; school trustees.— The supervision

of schools in each county and city shall be vested in a school

board, to be composed of trustees to be selected in the man

ner, for the term and to the number provided by law. Each

magisterial district shall constitute a separate school district,

unless otherwise provided by law, and the magisterial dis

trict shall be the basis o f representation on the school board

of such county or city, unless some other basis is provided

by the General Assembly; provided, however, that in cities

o f one hundred and fifty thousand or over, the school boards

of respective cities shall have power, subject to the approval

of the local legislative bodies o f said cities, to prescribe

the number and boundaries of the school districts.

The General Assembly may provide for the consolidation,

into one school division, of one or more counties or cities

with one or more counties or cities. The supervision of

schools in any such school division may be vested in a single

school board, to be composed of trustees to be selected in the

manner, for the term and to the number provided by law.

Upon the formation of any such school board for any such

school division, the school boards o f the counties or cities in

the school division shall cease to exist.

There shall be appointed by the school board or boards of

each school division, one division superintendent of schools,

who shall be selected from a list o f eligibles certified by the

State Board of Education and shall hold office for four

years. In the event that the local board or boards fail to

elect a division superintendent within the time prescribed by

law, the State Board of Education shall appoint such divi

sion superintendent.

* * *

App. 2

VA . CODE ANN. (1950)

§ 15.1-982. Result o f census; order.—-If it shall appear

to the satisfaction o f the court, or the judge thereof in va

cation, from such enumeration that such incorporated com

munity has a population of five thousand or more, such

court or judge shall thereupon enter an order declaring that

fact to exist and thereafter such incorporated community

shall be known as a city and entitled to all the privileges

and immunities and subject to all the responsibilities and

obligations pertaining to cities o f this Commonwealth. . . .