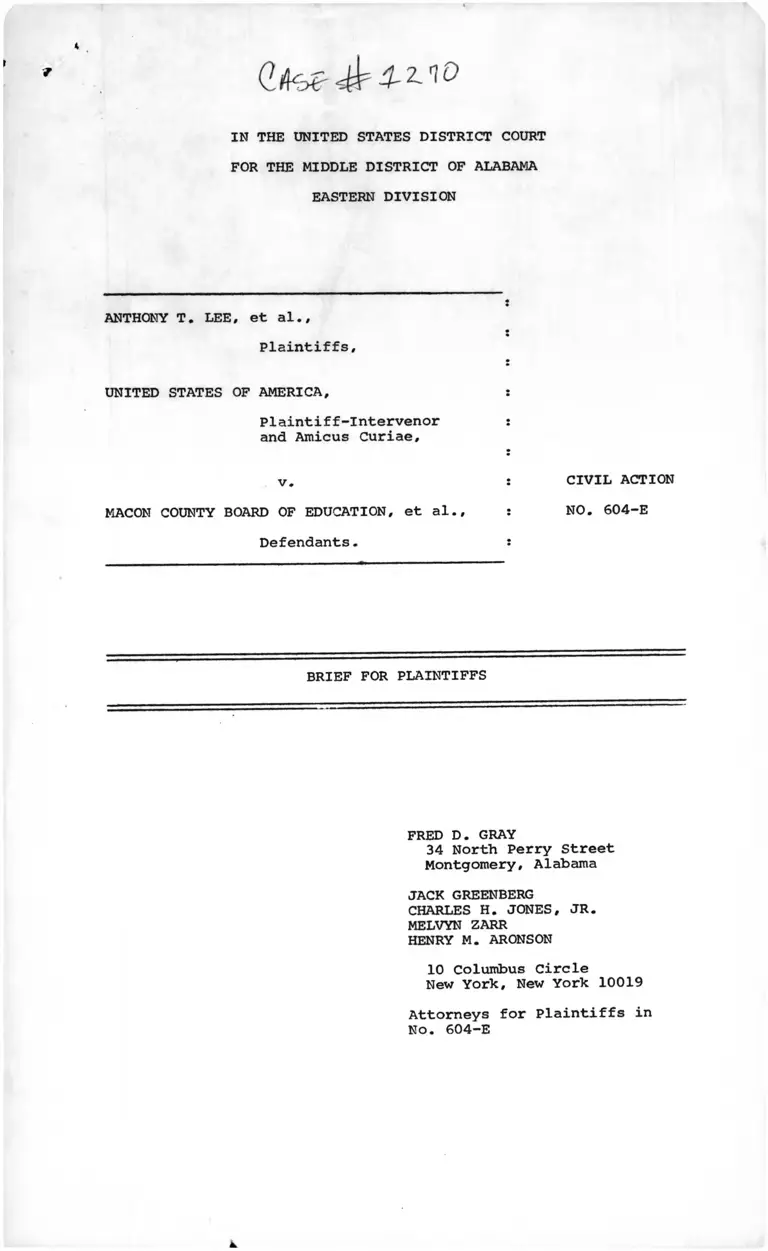

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs

Public Court Documents

January 31, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lee v. Macon County Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs, 1967. 78c2773c-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ec11bda6-5163-4dbc-b3b7-66bcb1eef5aa/lee-v-macon-county-board-of-education-brief-for-plaintiffs. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

r

i

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

EASTERN DIVISION

ANTHONY T. LEE, et al..

Plaintiffs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, :

Plaintiff-Intervenor :

and Amicus Curiae,

v. : CIVIL ACTION

MACON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al., : NO. 604-E

Defendants. :

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS

FRED D. GRAY34 North Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES H. JONES, JR.

MELVYN ZARR

HENRY M. ARONSON

10 Columbus Circle New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs in

No. 604-E

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 76-1998, 1999, and 2199

NORA LEWIS, ELIZABETH BULLOCK, MARY

CARTER, BETTY JOHNSON and GERTRUDE

MOODY, each individually and on behalf

of all other persons similarly situated,

Appellees,

v .

PHILIP MORRIS INCORPORATED, a corporation

TOBACCO WORKERS' INTERNATIONAL UNION,

an unincorporated association; and LOCAL

203, TOBACCO WORKERS' INTERNATIONAL UNION,

an unincorporated association,

Appellants.

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND

SUGGESTION FOR REHEARING EN BANC

OF NORA LEWIS, et al.

\

INDEX

Introduction

PART 1: The Constitution Of The Uhited States Imposes

Upon The Defendants An Affirmative Duty To

Effectuate Statewide Desegregation Because The

Defendants Operate A State System Of Education.

This Duty Has Not Been Fulfilled; Rather, The

Defendants Have Exercised Their General Control

And Supervision Over All The Public School In

The State To Promote And Maintain Segregation

And Other Forms Of Racial Discrimination.

Introduction

I. The Defendants Have Continued To Exercise

Their Pervasive Powers To Frustrate Local

Attempts At Desegregation. -------------

II. The Defendants Control School Finances And

Fiscal Policies And Have Exercised That

Control To Promote And Maintain Segregation

And Other Forms Of Racial Discrimination.~

III. The Defendants Control Instructional Programs

And Policies And Have Exercised That Control

To Promote And Maintain Segregation And Other

Forms Of Racial Discrimination. -------------

IV. The Defendants Control School Construction And

Consolidation Programs And Policies And Have

Exercised That Control To Promote And Maintain

Segregation And Other Forms Of Racial Discrimi

nation. —

V. The Defendants Control School Transportation

Programs And Policies And Have Exercised That

Control To Promote And Maintain Segregation

And Other Forms Of Racial Discrimination. --

PART 2: Nature Of The Relief.

PAGE

1

3

6

19

25

26

29

30

Proposed Decree 42

-2-

this Court, was, of course, not applied by the district court

to the facts of this case. Moreover, as this Court pointed out,

"the opinion [of the district court] is not clear on the precise

grounds on which it rests" (Slip Opinion at 21). Finally,

this Court determined that the lower court not only failed

to properly articulate the grounds for its decision but also

that the opinion "may be said to have been based" (emphasis

added) on an erroneous legal analysis of the applicable law

3/

at the time the decision was rendered (Id.); this Court

proceeded to set forth the applicable law.

This Court should remand the race allegations of

the complaint to the district court to properly apply the

intervening Supreme Court law, to adequately articulate

the grounds for decision and to apply the law consistent

with the opinion of the Court. This review requires, as

we set forth below, consideration of several critical

factual questions; this consideration should appropriately

be undertaken in the first instance, as the Supreme Court

directed in Hazelwood v. United States , supra and in Dothard v.

Rawlinson, supra by the district court.

The Lewis petitioners respectfully maintain that

rehearing may be granted and simply resolved by remand

ing rather than dismissing the allegations of racial dis

crimination. However, the Lewis petitioners further maintain

A finding that provides the Appellate Court with

n ̂ b mere conjectures as to the reasoning, both factually and

legally, used by the district court" is reason for remand.

Patrician Towers Owners, Inc, v. Fairchild, 513 F. 2d 216, 221

(4th Cir. 1975) .

Introduction

In this supplementary proceeding, plaintiffs seek the

establishment of no new principles of law. None are required.

What is required is the establishment of procedures to insure

that the principles enunciated by this Court on July 13, 1964

will be enforced in such a way as to make equal educational

opportunity a reality for Negroes in Alabama.

That these principles have not been translated into reality

is an understatement. To the contrary, they have been system

atically and openly defeated.

In its opinion, the Court directed the present defendants -—

2/ 3/

George C. Wallace, Austin R. Meadows and the Alabama State

4/Board of Education — to recognize that !l in the exercise of

their general control and supervision over all the public schools

in the State of Alabama and particularly in the allocation and

distribution of state funds for school operations, they have an

affirmative duty to proceed with 'deliberate speed' in bringing

about the elimination of racial discrimination in the public

schools of this State" (231 F. Supp 743, 756). Those defendants

were directed "to formulate and place into effect plans designed

to make the distribution of public funds to the various schools

throughout the State of Alabama only to those schools and school

1/ This proceeding is on plaintiffs’ alternative motion for fur

ther relief filed September 22, 1966, and plaintiffs' motion for

a preliminary injunction against defendant George C. Wallace in

his capacity as Governor of the State of Alabama filed November 2̂.,

1966.

2/ Governor and President of the Alabama State Board of Education.

This defendant was originally served solely in his latter capacity.

J3/ State Superintendent of Education and Executive Officer and

Secretary of the Alabama State Board of Education.

4/ The present members of the Alabama State Board of Education

are: James D. Nettles, Ed Dannelly, Mrs. Carl Strang, Fred L.

Merrill, W. M. Beck, Victor P. Poole, W. C. Davis, Cecil Word, and

Rev. Harold C. Martin.

-4-

the Appeals Court erred in substituting its judgment for

that of the trial court. The Supreme Court, however, ruled

that additional statistical factors require consideration;

but, importantly, the Supreme Court declined to rule on the

inferences to be determined from the statistics in the

first instance because,

"statistics . . . come in infinite variety

. . . Their usefulness depends on all the

surrounding facts and circumstances." Only

the trial court is in a position to make the

appropriate determination. . . ." 53 L.Ed.2d

at 780. (Emphasis added)

In another Title VII case decided on the same, day

as Hazelwood, the Court further emphasized this point, Dothard

v. Rawlinson, 53 L.Ed. 786, 803-04 (1977):

"It is for the District Court in the first

instance to determine whether statistics appear

sufficiently probative enough of the ultimate

fact in issue . . . . In making this determina

tion, such statistics are to be considered in

light of all other relevant facts and circum

stances. . . . " If the defendants in a Title

VII suit believe there to be any reason to

discredit plaintiffs' statistics that does

not appear on their face, the opportunity to

challenge them is available to the defendants

just as in any other lawsuit. They may endeavor

to impeach the reliability of the statistical

evidence, they may offer rebutting evidence,

they may disparage in arguments or in briefs

the probative weight which the plaintiffs

evidence should be accorded."

The defendants in this case attempted to discredit the

plaintiffs statistics in several of the ways outlined by

the Supreme Court in Dothard. The district court considered

and rejected these criticisms offered by the defendants,

419 F. Supp. at 354-56. Even though this Court disagreed

with the lower court's analysis, it was not proper for the

in thesystems that have proceeded with 'deliberate speed'

desegregation of their schools and school systems as required

by Brown v. Board of Education"(231 F. Supp. at 756-57).

Defendants concede that they have made no plans to cease

their "unconstitutional support of segregated school systems"

6/(231 F. Supp. at 756). Instead, they have continued to employ

their general control and supervision over public education in

the State of Alabama to promote and maintain segregation.

Plaintiffs still seek what they sought in 1964, namely, an

order directing these defendants to effectuate "desegregation in

all the public schools of the State of Alabama" (231 F. Supp. at

756). In 1964, this Court held (231 F. Supp. at 756):

For the present time, this Court will

proceed upon the assumption that the Governor,

the State Superintendent of Education and the

State Board of Education will comply in good

faith with the injunction of this Court . . .

and, through the exercise of considerable

judicial restraint, no state-wide desegre

gation will be ordered at this time.

The reliance by the Court on the good faith of these defend

ants has since been conclusively demonstrated as misplaced.

Instead of promoting and encouraging desegregation, these defen<j-

.ants have done their best to prevent, discourage and obstruct

7/

desegregation, both at the state and local level. Thus there is

no cause today for continued judicial restraint, for it will only

serve to further delay trie enjoyment of the federal constitutional

rights of the 300,000 Negro public school students of Alabama.

5/

J5/ Delays once found to be consistent with "deliberate speed"

are no longer permissible in this circuit. See United States v.

Jefferson County Board of Education. 5th Cir., December 29, 1966,

in which the Court stated (slip op. p. 49):

The announced speed of desegregation no

longer seems to be a critical issue. The

[defendant] school boards generally con

cede that by the school year 1967-68 all

grades should be desegregated.

€>/ State Superintendent of Education Meadows conceded in open

court that he has done nothing to eliminate segregation, but he

maintained that his only duty was to eliminate"discrimination"

(Meadows' testimony, Transcript 77-78; 147-48). Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) teaches that segregation ̂ is discri

mination.

1_/ The so-called anti-guidelines bill (Acts of Alabama 1966, Special Session, Act No. 252 (H. 446)) is but one example of the

defendants' efforts to thwart desegregation.

- 2 -

-6-

district judge. United States v. Appalachian Electric

Power Co., 107 F.2d 761 (4th Cir. 1939) See aĵ so Hamnick

v. Aerojet-General Corp., Indus. Sys. Div., 528 F.2d 65, 67

(4th Cir. 1976) concurring opinion. cf. Glasscock v. United

States 323 F.2d 589 (4th Cir. 1963) and United States v.

Warwick Mobile Home Estates, Inc., 537 F.2d 1148 (4th Cir. 1976).

The Supreme Court in the 1976 and 1977 terms

summarized three general types of unlawful systemic dis

crimination which may be briefly summarized for purposes

of this petition. The Court determined that purposeful

discrimination, disparate treatment, violates Title

VII; but more to the point, the Court, as the panel noted,

(Slip Opinion at 25-6), held that a statistical imbalance

may create a prima facie case of purposeful discrimination,

Teamsters v. United States, supra at 339-40.

The second type of systemic discrimination, disparate

effect, also may depend on statistical analysis, however, these

statistics do not have to lead to a conclusion of purposeful

discrimination but only that "the facially neutral standards

in question select applicants for hire [or promotion, assign

ment, etc.] in a significantly discriminatory pattern." Dothard

v. Rawlinson, supra at 797; Teamsters v. United States, Supra at

n. 15; see Nashville Gas Co. v. Satty, 15 EPD 1[7948 at 6734-35

(1977) .

Finally, the Court held that practices which continue

the effect of prior purposeful discrimination may be unlawful.

For example,in Teamsters the Court determined that a seniority

In Part 1 of this brief, plaintiffs will demonstrate that

the statewide relief sought since 1964 should no longer be with

held. In Part 2 of this brief, plaintiffs will treat the nature

of that relief.

PART 1

The Constitution Of The United States Imposes

Upon The Defendants An Affirmative Duty To

Effectuate Statewide Desegregation Because

The Defendants Operate A State System Of

Education. This Duty Has Not Been Fulfilled;

Rather, The Defendants Have Exercised Their

General Control And Supervision Over All The

Public Schools In The State To Promote And

Maintain Segregation .And Other Forms Of Racial

Discrimination.

Introduction

In its 1964 opinion, this Court concluded that the present

defendants — George C. Wallace, Austin R. Meadows and the Alabama

State Board cx Education — possess "general control and super

vision over all the public schools in the State of Alabama" (231

F. Supp. at 756), finding (231 F. Supp. at 750-751):

The evidence in this case is clear that over the years the State Board of Education

and the State Superintendent of Education

have established and enforced rules and

policies x'sgarding the manner in which the

city and county school systems exercise their

responsibilities under State law. This con

trol relates, among other things, to finances,

accounting practices, textbooks, transporta

tion, school construction, and even Bible

reading.

Since that time nothing has occurred to diminish the force

of that conclusion (See, e.g. Meadows’ testimony, Tr. 15-16).

To the contrary, that conclusion has been buttressed by

defendant Meadows himself. On March 4, 1965, defendant Meadows

cited his plenary constitutional power over public education in

8/Alabama, granted him by Section 262 of the Constitution

Q/ Section 262 of the Constitution of Alabama provides:

The supervision of the public schools shall

be vested in a superintendent of education,

whose powers, duties and compensation shall

be fixed by law.

3

-8-

neutrality is, in fact, not neutral, for

past acts of discrimination continue to

significantly affect modern practice.

'Under the act, practices, procedures, or

tests neutral on their face, and even

neutral in terms of intent, cannot be

maintained if they operate to 'freeze' the

status quo of prior discriminatory employ

ment practices." Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424, 430 (1971). See also Quarles

v. Philip Morris, Inc., supra. The company

in order to reassert a balance, should have

informed all applicants for hourly positions

at the beginning of any interview (1) of the

position currently available in each of the

four departments with an appropriate job

description and (2) that it assigns and

hires new workers without reference to race.

All those class members that were not so

informed when they were hired into the Stemmery,

and that believed that their race substantially

limited their initial employment to the Stemmery

are entitled to recover for their losses." (emphasis

supplied)

Appellees submit that the above-quoted excerpt

indicates that the district court was not referring to a

"racially balanced workforce" but instead that language

referred to the previously mentioned "disadvantage" that black

applicants had because of the prior discriminatory practices of

the company and the company's failure to adequately dispel

the belief of black workers established by the company's

unlawful practices that initial job assignments were made by

race; a belief which was not held by most white applicants.

In order to remove this disadvantage the court held that the

company should have informed applicants of all the available

positions and tha.t job assignments are made without reference

to race.

of Alabama to then United States Commissioner of Education Keppel

(Government's Exhibit 157):

The State Superintendent of Education is the

only educational official or agency that is

in the Constitution for the supervision of

the public schools in this State . . . The

State Superintendent of Education is the

only state agency or official required by law

to sign and approve budgets of county and city school systems, sale of school warrants of

indebtedness by county and city school systems,

all vocational education contracts with county

and city boards of education, all Title III

documents of county and city boards of educa

tion, all Title V-A documents, all Title X

documents, all Vocational Education Act of

1963 documents, all Manpower Development and

Training Act of 1962 documents, all Training

Redevelopment Act documents, and will be the

legally constituted authority to disburse all

Federal funds to all services, local and State.

The following year, in his letters of May 24, 1966 to local

school superintendents (Government's Exhibits 36-57), defendant

Meadows invoked his plenary constitutional power under Section

262, in the following terms:

In accordance with Section 262 of the Constitu

tion of Alabama that places the supervision of

the public schools under the State Superintendent

of Education, I am requesting that no superinten

dent nor board of education sign any such agree

ment and, if signed, that such board withdraw

such agreement [to comply with HEW regulations].

Defendant Meadows' view of his powers mirrors a view con

sistently held by the Supreme Court of Alabama. In 1935, that

Court said:

Without question, public education through

a system of public schools is, by the Constitu

tion, as well as by the statutes, a government

function in Alabama; indeed a major 'activity of the state government.

County boards of education, county superin

tendents of education, county treasurer[s] of

public school funds, school district organiza

tions, are all part of the state set-up in

maintaining a system of public schools through

out the state.

* * *

Every public school is a state school, created

by the state, supported by the state, supervised

by the state, through state-wide and local agen

cies, taught by teachers licensed by the state,

employed by agencies of the state. Williams.

Supt. of Banks, et al. v. State. For Use and

4

- l O -

in Castaneda v. Partida. . . . It involves

calculation of the "standard deviation" as a

measure of predicted fluctuations from the

expected value of a sample . . . . The Court

in Castaneda noted that "[a]s a general rule

for such large samples, if the difference

between the expected value and the observed

number is greater than two or three standard

deviations", then the hypothesis that teachers

were hired without regard to race would be

suspect.

It is illuminating to apply the Castaneda -

Hazelwood formula to this case. From 1965-1974 approximately

50% of those hired were black while approximately 80% of

5/

those hired into the Stemmery were black. (Slip Opinion

at 24) Using the 50% figure as the expected value (assuming

even distribution by race as does the Supreme Court), the

difference between the observed value (80%) and the expected

value was 57.9 standard deviations. Moreover, for the period

from 1971-1974 the picture does not improve; there is a

difference of 57.4 standard deviations between the expected

6/

and the observed values.

Thus, the disparity in this case, 57 standard

deviations, is much larger than the general rule of 2-3

5/The specific figures which are used in the analysis

are found in the Record at App. 624-625.

6/Between 1971 and 1974, approximately 59% of all

hires were black while approximately 86% of all hires assigned

to the Stemmery were black.

Benefit of Pickens County, et al., 230 Ala.

395, 397, 161 So. 507, 507-08 (1935); fol

lowed in State v. Tuscaloosa County, et al»,

233 Ala. 611, 172 So. 892 (1937).9/

Succeeding sections of Part 1 will analyze specific major

areas of defendants' control of public education in Alabama and

will demonstrate the exercise of that control to promote and

maintain segregation and other forms of racial discrimination.

In I, plaintiffs will show that since this Court's 1964 opinion

and injunction the defendants have continued to exercise their

pervasive power over local school systems to frustrate desegre

gation attempts. In II, plaintiffs will examine the control

by these defendants over local school systems through rigid

control of their finances and will show that this control has

been exercised to promote and maintain segregation and other

forms of racial discrimination. In III, IV and V, plaintiffs

will show that the defendants control programs and policies

relating to, respectively, instruction, school construction and

transportation and have exercised that control to promote and

maintain segregation and other forms of racial discrimination.

This analysis will demonstrate the propriety and necessity of

a statewide desegregation order.

9/ Nothing said by the Supreme Court of Alabama in its advisory

opinion of February 18, 1964 casts doubt upon the state constitu

tional power of the defendants "to exercise general control and

supervision over the county and city boards of education" (160

So.2d 648, 650) or, presumably, to define and enforce state edu

cational policy regarding segregation and desegregation. The

court found that the Alabama Legislature had delegated to local

boards of education the power to assign pupils and teachers and

to provide transportation. However, as a matter of federal law,

that delegation is plainly ineffective to withdraw from responsi

ble state officials state authority to do what the federal con

stitution requires. "[Decisions of the Supreme Court of the

United States] compel a state in this [Fifth] Circuit to take

affirmative action to reorganize its school system by integrating

the students, faculties, facilities and activities” (United States

v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 5th Cir., Dec. 29, 1966,

slip op. p. 19).

5

-12-

the facts in the Record and to support its legal conclusion

8/

led to error in the panel's opinion. In fact, this witness was

affirmatively discouraged from initially seeking employment

9/

in a permanent department. Moreover, many other witnesses

testified at trial that they were only informed of vacancies

in the Stemmery, even though many of them were in fact seeking

10/permanent employment. Though not stated in the lower court's

findings, that testimony was a basis for, and adequately

supports the lower court's ultimate finding.

The district court, in fact, relied on the disparate

effect analysis of systemic discrimination in concluding that

the defendants violated Title VII:

8/

The question of whether, or to what extent, the trial

court relied on the testimony of a particular witness is a basis

for remand. See School v. Conboy, 551 F.2d. 41, 43 (4th Cir. 1977) .

9/

See App. 820-824; this testimony was unrefuted. In

fact, several other witnesses testified that they had been dis-

courgaged from transferring from Stemmery to Fabrication, which

amounted to the same as being a new hire since they could not

retain seniority credit for time spent in Stemmery. See App.

711-713; 737-738; 745; 749; 776; 780-782; 848; 945; 955; 1262;

1311-1313 and 1334.

10/

See pp. 703-705; 728, 730, 793, 943, and 1115;

See also 729, 777, 821, 843, 1065-67, 1104, and 1114. The panel

made repeated references to the lack of evidence to show that

defendants discouraged applicants (Slip. Opin. p. 30), however,

as noted above the trial court's basis for liability was

"failure to inform".

The Defendants Have Continued To

Exercise Their Pervasive Powers

To Frustrate Local Attempts At

Desegregation.

In its 1964 opinion, the Court warned these defendants that

they must no longer interfere with local desegregation attempts

" — either directly or indirectly — through the use of subtle

coercion or outright interference" (231 F. Supp. at 756). More

over, these defendants were ordered not to fail to exercise their

"control and supervision over the public schools of the state...

in such a manner as to promote and encourage the elimination of

racial discrimination in the public schools, rather than to

prevent and discourage the elimination of such discrimination"

(Order of July 13, 1964, <][6) .

Defendants concede that they have failed to promote or

encourage desegregation of the public schools of Alabama (Meadows'

testimony, Tr. 77-78; 147-48; Mrs. Strang’s testimony, Tr. 170).

What they have done is to flout this Court's warning against

interference with local desegregation attempts.— ^

The defendants' actions since the Court's 1964 ruling can

most usefully be examined chronologically.

On August 31, 1965, Governor George C. Wallace, Lieutenant

Governor James B. Allen;» and Speaker of the House of Representa

tives Albert Brewer sent telegrams to local school superintendents

of systems that had submitted desegregation plans to the United

States Department of Health, Education and VTelfare (HEW) covering

all grades (Government's Exhibits 6-11). These telegrams stated,

I.

10/ Plaintiffs recognize that this Court's warning against

interference with local desegregation included the words "when

the local school authorities are attempting to comply with the

desegregation orders of a federal court" (231 F. Supp. at 756).

But these words do not limit the defendants' obligation to refrain

from all interference with any local school system, for all local

school systems (whether under federal court order or not) are

under a federal constitutional obligation to desegregate.

6

-In

applicable law (much of which was announced by the Supreme

Court subsequent to the decision) should not lead to a dis

missal of the allegations of race discrimination but rather

11/

to a remand. As the Fourth Circuit stated in EEOC v. United

Virginia Bank-Seaboard National, 555 F.2d 403, 406 (1977):

" . . . there is not the 'detail and exactness'

on the material issues of fact necessary for an

understanding by an appellate court of the factual

basis for the trial court's findings and conclusions,

and for a rational determination of whether the

findings of the trial court are clearly erroneous.

It was to assure that 'detail and exactness' in

the trial court's findings as a predicate for intel

ligent appellate review that Rule 52(a) was adopted.

The failure of the district court to comply in this

case with the basic requirement of the Rule for

detailed findings of fact compels us to remand

the cause for detailed findings of fact and con

clusions of law by the trial court."

The panel's reasons for remanding the issue of

sex discrimination apply equally to the issue of race

12/

discrimination:

1. The findings of fact, on which the judgment

was granted, were phrased in broad conclusory

terms and did not include any subsidiary find

ings which would give appropriate support to

11/See United States v. Commonwealth of_ Virginia,

_______ F.2d __ _ (No. 77-1683), (4th Cir. 1978); and, Moseley

v. United States, 499 F.2d, 1361, 1363 (4th Cir. 1974).

12/

Petitioners respectfully submit that the Record

is sufficiently clear on the issue of race discrimination for

the Court to affirm the lower court's decision. But, at least,

the issue of race discrimination should be remanded.

in part: "[T]hose school systems which have been required to

desegregate under federal court order are not required to desegre

gate all 12 grades in one year. We think it would be advisable

for your school board to reconsider your action in the submission

of your compliance plan."

On September 3, 1965, these same superintendents received

"follow-up" telegrams from the same state officials, again urging

that their all-grade compliance plans be reconsidered (Government's

Exhibits 15-20) and defining the maximum tolerable desegregation

under state policy as the minimum desegregation required by the

federal courts.— ^ These telegrams requested the local superinten

dents to "take whatever action is necessary to see that the

administration and execution of these plans do not go beyond the

requirements of federal court orders of five grades." The

telegrams urged obedience to the resolution of the State Board of

Education of September 2, 1965 (Government’s Exhibit 12), which

stated that "any action taken by local school boards in excess

of minimum requirements of laws and court orders could jeopardize

the continued support by the public of public education." The

telegrams also stated: "We again respectfully call to your

attention that the execution and administration of plans beyond

those required is not in the interest of public education in the

State of Alabama."

On September 2, 1965, defendant Meadows sent telegrams to

local superintendents stating: "Please wire immediately number or

Negroes enrolled in white schools and total number grades in

which enrolled" (Government's Exhibits 13-14).

11/ Lauderdale County Superintendent Thornton's reply to this

telegram failed to convince the senders that he was innocent of

unnecessary desegregation. They replied: "We call upon you to

align your policies with the minimum requirements of the law and

of court orders" (Government's Exhibit 2 (Lauderdale)).

7

-16-

the district court; in the alternative the appellees

respectfully suggest that the case be reheard en banc.

Respectfully submitted

By ! * ' -/f -/>■' *-> ____

Henry L. Marsh, III

William H. Bass, III

Hill, Tucker & Marsh

509 North Third Street

Richmond, VA 23219

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

806 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

JACK GREENBERG

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, N.Y. 10019

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on the 5th day of June, 1978,

two (2) copies of the foregoing Petition For Rehearing And

Suggestion For Rehearing En Banc were mailed, postage prepaid,

to Lewis T. Booker, Esquire, Hunton & Williams, P. O. Box 1535,

Richmond, VA 23217, and Jay J. Levit, Esquire, Suite 2120,

Central National Bank Building, Richmond, VA 23219, counsel

for appellants.

A few days later, on September 7, 1965, a meeting was held

of all local school superintendents and defendants Wallace and

Meadows in Montgomery (see Government's Exhibits 21-25). At this

meeting, so defendant Meadows testified (Tr. 33), defendant

Wallace "again urged school boards not to go beyond what was

required...by the courts." The effect on the local superintendents

of being summoned by telegram from all over the state to attend a

special meeting at the State Capitol was predictable — and

intended. They got the message. Within a few hours after

returning from this meeting, the Choctaw County Board of Education

met and passed the following resolution (Government's Exhibit 35):

RESOLVED, that due to the change in

conditions, particularly within the past

few days, the Board concludes it is for the

best interest of the children attending the

schools of Choctaw County, Alabama, their

safety and welfare, for the continued orderly

operation of the schools in the County, and

for the prevention of violence which would

likely result in serious consequences adversely

affecting the orderly operation of the schools,

the plan of desegregation of the schools of Choctaw County, Alabama, adopted by this Board

on August 23, 1965, be and the same is hereby

revoked.

Another such meeting was held on March 31, 1966 (see Plain

tiffs' Exhibit 3). Defendant Wallace again urged the local boards

to do nothing in excess of the minimum desegregation requirements

of the federal courts (Meadows' testimony, Tr. 33). A smaller

meeting, involving only about 15 local superintendents, was held

in the Governor's office on April 6, 1966 (see Government's

Exhibit 26). At this meeting defendants Wallace and Meadows

recommended that the local superintendents not submit HEW compliance

agreements or, if submitted, that they be qualified (Meadows'

testimony, Tr. 40-41) ^

12/ Some local superintendents who attended apparently were

persuaded. That same day, defendant Meadows wrote HEW requesting

the return of Geneva County's executed Form 441-B, submitted the

previous day (Government's Exhibit 2 (Geneva)).

8

The defendants next accelerated their campaign against

faculty desegregation. On May 10, 1966, defendant Meadows sent

a letter to Lauderdale County Superintendent Thornton "recom

mending" "that you not integrate teachers unless you have a court

order requiring you to do so" (Government's Exhibit 27). The next

day defendant Meadows sent letters to about 20 local superintendents

(those that he knew had signed unconditional Form 441-B compliance

agreements) (see Government's Exhibit 34), stating (Government's

Exhibits 28-34): "I am requesting that you ask your Board of

Education to reconsider its action in adopting form 441-B and

through you, I recommend that your Board rescind agreement of

HEW Form 441-B." The next day. May 12, 1966, defendant Meadows

returned Cleburne County's form 441-B with the "recommendation"

that it be amended, setting forth the amendment. This was done

(Plaintiffs' Exhibits 12-13).

On May 13, 1966, a resolution was unanimously approved by

defendants Wallace and Moadows, the Lieutenant Governor, the

Speaker of the House and the Alabama Congressional Delegation

and sent to all local superintendents in a release by defendant

Meadows of May 16, 1966 (Government's Exhibit 36). This resolu

tion urged "that every responsible official should continue to

resist all illegal requirements imposed by the 1966 Guidelines,

such as faculty desegregation and quota or percentage pupil

assignments." (As we have seen, the defendants' definition of

"illegal" desegregation is any desegregation beyond the minimum

requirements of the federal courts.) On May 19, 1966, defendant

Meadows released a resolution of the State Board of Education

commending the May 13th resolution to all the local superintendents

and "recommending""that local school superintendents and boards

of education withdraw any 441-B signed agreements for the new

Guidelines" (Government's Exhibit 37).

On May 24, 1966, defendant Meadows sent letters to all local

superintendents "requesting" them to withdraw their unconditional

9

Forms 441-B and to report their actions to him by May 30, 1966.

The letters stated in part (Government's Exhibits 38-57):

In accordance with Section 262 of the

Constitution of Alabama that places the

supervision of the public schools under

the State Superintendent of Education, I

am requesting that no superintendent nor board of education 3ign any such agreement and, at such board withdraw

On June 2, 1966, defendant Meadows sent telegrams to 17

superintendents that had not furnished the reports "requested"

in his May 24th letter, stating (Government's Exhibits 66-67);

Plaintiffs' Exhibit 11): "May 24th letter requesting report,

approved by State Board of Education, on your Board's action on

HEW guidelines not received and such report will be necessary

before any further distribution of any funds to your school sys

On June 6, 1966, a meeting of all local superintendents with

defendants Wallace and Meadows was held in Montgomery (see Govern-

the local school authorities he would take his case against volun

tary desegregation plans submitted in compliance with HEW require

ments "to the people," meaning that he would stage mass meetings

13/ Defendant Meadows’ May 24th letter bore immediate fruit.

Winston County Superintendent Albright wrote him on May 30, 1966,

advising him that HEW Form 441-B had been withheld "from respect

of you, the State Department of Education and our Governor"

(Government's Exhibit 118). Sheffield City Superintendent Brewster

replied on May 27, 1966: "I am pleased to report that the

Sheffield Board has not signed form 441-B" (Government's Exhibit

112). Marion County Superintendent Hudson replied on May 27, 1966..

that it was withdrawing its form 441-B (Government's Exhibit 109).

Escambia County Superintendent Weaver replied on May 28, 1966 thr.t

at the May 27th meeting of the Board of Education, it voted not to

sign form 441-B (Government's Exhibit 106). Other systems delayed

action on compliance until after the state-wide meeting of June 6,

1966, discussed, infra, (see, e.g., Government's Exhibits 105,107, 110).

14/ In advance of this meeting, local superintendents were fur

nished by the Governor with a legal memorandum arguing the

illegality of the guidelines, in which defendant Wallace stated:

"I hope you will reconsider or already have reconsidered this

matter in accordance with our request" (Government's Exhibits 62-65).

such

tem. "

ment's Exhibits 58-61) 14/ At that meeting Governor Wallace told

10

in localities where compliance had been effected (Meadows'

testimony, Tr. 61-62)

To the local superintendents the message was unmistakably

clear. That same day the Talladega County Board of Education

reversed its earlier intention to execute a form 441-B? this

action was communicated on June 9th to HEW by Superintendent

Pittard, with the explanation that "conditions are such that our

Board is unwilling to pledge compliance with the 1966 Guidelines

at this time" (Government's Exhibit 2 (Talladega)).

On June 9th, Martin Ray, the attorney for the Tuscaloosa

City and County School Systems, wrote to HEW (Government's

Exhibit 1 (Tuscaloosa)):

As a result of pressures, applied and

threatened, I request that any informa

tion with regard to the proposed staff

cross-overs by either the Tuscaloosa

County or City School System remain

confidential.

Florence City Superintendent Hibbert characterized the

situation in the period after the meeting in a later letter to

HEW (Government's Exhibit 1 (Florence)):

...About that time the top blew off

again in Alabama over the fact that we

had signed 441-B. Some local Boards,

including ours, were threatened with

called mass meetings to oppose the

signing of 441-B. Although our Board

was unmoveable on the question of

rescinding 441-B, it seemed best not

to go beyond our present position for

fear that a certain party might cause

an explosion in our otherwise peaceful

and harmonious community.

On June 10 and 11, 1966, defendant Wallace, Lieutenant

Governor Allen and Speaker Brewer sent telegrams to local super

intendents requesting the status of compliance with the guidelines

(Government's Exhibits 68-76).

15/ Defendant Meadows testified that the Governor had offered

Meadows' services as well and that he did not demur (Tr. 63). Defendant Meadows also testified that the local officials would be

"invited" to attend and would be given an opportunity to defend

their positions (Tr. 62).

11

On July 1, 1966, defendant Meadows expressed his views on

"segregation" in a release sent to all local superintendents

(Government's Exhibits 77-82), This release stated in part:

"Segregation is the basic principle of culture."

On July 29, 1966, defendant Meadows sent telegrams to all

local superintendents directing them to report by return mail or

telegram "the number of Negro teachers assigned for 1966-67 to

white schools" (Government's Exhibits 84-91).

As the defendants1 war against faculty desegregation intensi'

fied, newer weapons appeared indicated.

On August 18, 1966, defendant Wallace appeared before a

joint special session of the Legislature of Alabama and urged the

enactment of H.B. 446, the anti-guidelines bill (Government’s

Exhibit 92). On August 22, 1966, the defendant State Board of

Education "wholeheartedly" endorsed the legislation (Government's

Exhibit 93), and, the following day, defendant Meadows, in a

statement to the committee of the Legislature, recommended certain

strengthening amendments to the proposed legislation (Plaintiffs'

Exhibit 8; Meadows' testimony, Tr. 134).

On September 2, 1966, the anti-guidelines bill was passed

as Act No. 252. It provides that: "Any agreement or assurance of

compliance with the guidelines heretofore made or given by a local

County or City Board of Education is null and void and shall have

no binding effect."

In the face of the defendants' incremented attack on faculty-

desegregation, the Tuscaloosa County Board of Education displayed

uncommon pluck in assigning two Negro teachers to teach in white

schools at the opening of school on September 6th. A response

from the defendants was not long in coming. On September 8th,

defendant Meadows telephoned Superintendent Elliott and "recom

mended" that the two Negro teachers be returned to Negro schools

(Elliott's deposition, p. 63). Defendant Meadows, invoking his

power as constitutional officer of the state, stated that the

12

assignment of Negro teachers to white schools was "against the

law" and "public policy" of the State of Alabama (Elliott's

deposition, pp. 63, 64, 68).

The next day, Friday, September 9th, defendant Wallace

informed a press conference that he would use the police power of

the state to maintain"peace"and "requested" that the two Negro

teachers be returned to Negro schools (Elliott's deposition, p. 68).

The two Negro teachers immediately took heed. On Sunday evening,

September 11th, they called Superintendent Elliott and asked him

to meet with them at 7:30 the next morning (Elliott's deposition,

p. 119). The next morning they not unexpectedly voiced apprehen

sion about their assignments and expressed an unwillingness to

teach that day (Elliott's deposition, p. 119). They remained in

Elliott's office all morning and then went home, staying there

for the next two days.

The next day, Tuesday, September 13th, defendant Meadows

again called Superintendent Elliott and "recommended" the Negro

teachers be reassigned.l^/ The same day, Hugh Maddox, legal

advisor to the Governor, telephoned Elliott and reminded him that

it was the public policy of the state that Negro teachers not

teach white children; Maddox also reminded Elliott of the Gover

nor's intention to use the police power of the state to preserve

desirable conditions (Elliott's deposition, pp. 66-68).

Also on September 13th, defendant Meadows undertook to

answer a letter to Superintendent Elliott from a private citizen

on this matter, stating (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 7): "A strong stand

by people like you will help to prevent assignment of Negro

teachers to white schools.... The Governor has certainly done

everything that anyone can do to prevent what is happening at

the Tuscaloosa County school system and we are both trying to do

everything that we can to get the teacher assignment changed."

16/ Defendant Meadows testified generally as to those conversa

tions (Tr. 65, 139).

13

On September 22, 1966, defendant Meadows issued a release

reminding the local superintendents that any desegregation beyond

the minimum required by federal law was intolerable as a matter of

state policy (Government's Exhibit 94). In an initialled attach

ment to the release defendant Meadows stated: "The Governor

requests reassignment of Negro teachers so as not to be teaching

white children."

On October 17, 1966, defendant Meadows again telephoned

Superintendent Elliott and advised him that the Governor had

suggested that two additional teacher units be allotted to

Tuscaloosa County on condition that the students in the white

schools then being taught by the Negro teachers be allowed the

freedom to choose a white teacher (Government's Exhibit 95). On

the following day, defendant Meadows attended a meeting of the

Tuscaloosa County Board of Education and made the same proposal

in person (Government's Exhibit 96). On October 24th, defendant

Meadows wrote Superintendent Elliott reconfirming his previous

offer, and adding (Defendants' Exhibit 5):

This is to further announce to you that

the Public School and College Authority

will approve any priority request for use

of the State Board Issue funds allocated

to the Tuscaloosa county Board of Education

for making classroom space available for the two teachers.

Defendants' attempts to resegregate faculties culminated in

a faculty resegregation plan promulgated on October 25, 1966,

providing (Government's Exhibit 97): "In complete accord and with

full approval of Governor George C. Wallace, any county or city

board of education will be allocated a teacher unit and apportion

ment of funds therefor where such board employs a teacher for

pupils to transfer from a teacher of the opposite race to a

teacher of their own race by freedom of choice of such pupils and

their parents."

Having considered at some length the actions taken by these

defendants since this Court's opinion and injunction of July 13,

14

1964, it is now appropriate to state some of the conclusions which

emerge therefrom.

First, the defendants have manipulated the concept of

"deliberate speed" enunciated by the Supreme Court in Brown v.

Board of Education II to inhibit desegregation. Brown II and

succeeding decisions made it clear that nothing short of complete

desegregation would be countenanced, although a transition period

to accomplish complete desegregation was permitted during which

public school systems were expected to do all in their power to

accomplish complete desegregation. That transition period has

expired: "The clock has ticked the last tick for tokenism and

delay in the name of 'deliberate speed'" (United States v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, 5th Cir., Dec. 29, 1966,

slip op. p. 57). As the preceding survey has shown, the defendant?

have stood Brown II on its head by consistently defining state

policy as rendering unlawful any actions of local school officials

in excess of minimum desegregation requirements of federal courts

(see e.g.. Meadows' testimony, Tr. 61). This policy has defeated

the function of the transition period envisaged in Brown II.

The anti-guidelines bill marks merely a codification of this

policy, for it was enforced for at least a year prior to enactment

of the bill. To stifle voluntary desegregation and discourage

acceleration of existing desegregation plans beyond minimum

requirements of federal courts is nothing short of the "outright

interference" condemned by this Court's 1964 ruling.

Second, the defendants have seriously misconstrued their

federal constitutional obligation to desegregate. Defendant

Meadows, in open court, purported to be ignorant of the teaching

of Brown v. Board of Education, viz, that "segregation" is.

"discrimination." Defendant Meadows drew a distinction between

the two terms (Tr. 148) and, although admitting he had done

nothing to eliminate segregation in the public schools of Alabama

(Tr. 77-78; 147-48), he denied having done nothing about "dis

crimination." Apparently, the teaching of Brown must be made

- 15

clear to him and his successors if segregation and releases such

as that of July 1, 1966 (Government's Exhibits 77-82) are to

end.i^/ The defendants have also apparently failed to understand

that the desegregation of faculties is essential to the disesta

blishment of dual school systems based upon race. Bradley v.

School Board of Virginia, 382 U.S. 103 (1965); Rogers v. Paul,

382 U.S. 198, 200 (1965)— /

Third, defendants' protestations that their actions have

been non—coercive have a hollow ring. It is true that in the

defendants' letters, telegrams, releases, meetings, etc., preca

tory words such as "request," "recommend," and "advise" have been

employed. But it may hardly be thought that local school authori

ties, being in a dependent position vis-a-vis these defendants

did not get the message. One example will suffice. In his

letters of May 24, 1966, to all local superintendents (Government's

Exhibits 38-57), defendant Meadows "requested" them to submit

reports to him as to their compliance with the HEW guidelines.

Some 17 of the local superintendents failed to satisfy this

"request" and were immediately threatened with a cutoff of all

state funds.(Government's Exhibits 66-67; Plaintiffs' Exhibit 11).

Nor can the anti-guidelines bill be considered non-coercive.

Among other things, this bill nullifies all local compliance agree

ments of HEW in their entirety. Its effect on local school

officials has been predictable and intended: it is state law and

17/ Even under defendant Meadows' pre-Brown definition of racial

discrimination, the defendants have been guilty of federal consti

tutional violations, for there is a tragic disparity between

educational opportunities offered to Negroes and educational

opportunities offered to whites in Alabama.

18/ See Meadows' testimony, Tr. 99.

19/ See, e.g., Anniston City Superintendent Hall's letter of

April 15, 1966, pointing out one aspect of local dependency

(Government's Exhibit 1 (Anniston)).

16 -

they feel bound by it. See Walker County Superintendent

Cunningham's testimony, Tr. 54? Lee County Superintendent Marshall's

letter of September 29, 1966 to HEW (Government's Exhibit 2 (Lee))?

Pickens County Superintendent Burns' letter of October 11, 1966,

to HEW (Government's Exhibit 2 (Pickens))? Calhoun County Super

intendent Boozer's response to Mr. Maddox of October 25, 1966

(Plaintiffs' Exhibit 16).

Fourth, the defendants have failed to understand that,

notwithstanding a school system is not under a federal court order

to desegregate or has not complied with HEW requirements, it is

not relieved from its paramount federal constitutional obligation

to desegregate. Strictly speaking, the absence of a federal court

order only allows a school system that does not effectively de

segregate to escape punishment for contempt. And failure to

comply with HEW desegregation requirements only triggers the

withdrawal of federal financial support. But no amount of

obfuscation can blur the fact that local school authorities have

a federal constitutional obligation to totally and effectively

desegregate their school systems and that these defendants are

forbidden to interfere with the performance of that obligation.

Fifth, it is against this background of a paramount federal

constitutional obligation to desegregate on the part of local

school systems that the anti-guidelines act must be considered.

Although its importance cannot be doubted, the question of the

compatibility of the guidelines with the Civil Rights Act of 19G4

is not central to this c a s e . ^

The question presented here is whether the anti-guidelines

act has been employed by the defendants as an instrument of inter

ference with the performance by local school systems of their

paramount federal constitutional obligation to desegregate. Since

the anti-guidelines act nullifies all desegregation compliance

20/ It is, of course, central to the companion case, No. 2457-N.

17

agreements in their entirety, it must be condemnable if it in

any way interferes with the performance of the local systems'

obligation to desegregate. From the survey earlier undertaken,

there can be no doubt of that interference. Indeed, the defend

ants have conceded as much: since the anti-guidelines act is

avowedly designed to defeat faculty desegregation, and since

faculty desegregation is part of the local systems1 federal

constitutional obligation to desegregate, the act must fall.

18

II.

The Defendants Control School Finances And

Fiscal Policies And Have Exercised That

Control To Promote And Maintain Segregation

And Other Forms Of Racial Discrimination.

A. Nature And Extent Of The Control.

In its 1964 opinion, this Court found that "[t]he control

by the State Board of Education over the local school systems

is effected and rigidly maintained through control of the

finances" (231 F. Supp. at 751). This condition continues to

prevail.

It is undisputed that state funds are the predominant

support of local schools. In 1964, the Court found that for

the latest reported year, over 90% of the financial support of

the public schools in Macon County came from the State (231 F.

Supp. at 751). The Court continued: "The annual report of the

State Board of Education further reflects that the other counties

in Alabama heavily rely upon State financing for the operation

of their school systems" (231 F. Supp. at 751). This is still

true today. The latest figures released by the State Department

of Education reveal that over 70% of the financial support of21/

public education in the State of Alabama comes from the State.

Most of the state financial support is administered under

the Minimum Program Fund. In 1964, the Court found: "The allo

cation of State 'minimum program' funds, which comprise a manor

part of the State contribution, is according to 'teacher units'

in each local school system. The State Board of Education has

considerable discretion in the manner of allocating these teacher

units" (231 F. Supp. at 751).

The defendants today continue to exercise considerable

discretion in the allocation of Minimum Program funds. For

example, the State Board of Education has granted the following

21/ The 1965 Annual Report, p. 18.

19

broad powers to the State Superintendent:

In order to provide more nearly equal

educational facilities for all children,

the State Superintendent of Education may

approve the allocation of additional teacher

units to junior and senior high schools where

requested, to carry out the purpose of the

pupil placement law, if in his judgment after

investigation the circumstances justify such

approval (Government's Exhibit 127, I.A. 1,

p. 2) .

Other examples of the State Board's discretion over Mini

mum Program funds are its power to change the teacher unit

ratio (Government's Exhibits 127, 128) and to grant more units

to small survey-approved schools than to small non-approved

schools (Director Layton's testimony, Tr. 227-28).

Moreover, defendant Meadows possesses the wide powers

of the purse recited by him in Government's Exhibit 157, quoted

22/

earlier at p. 4, supra.

What the State gives, it can take away. In defendant

Meadows' telegrams to the 17 local superintendents who had

not filed the requisite reports on their rescission of Form

441-B, defendant Meadows threatened the cut-off of all state

funds to their school systems (Government's Exhibits 66-67;

Plaintiffs' Exhibit 11). At the trial of this case, defendant

Meadows testified that such cut-offs were within his state

23/

constitutional power (Tr. 149).

22/ Defendant Meadows' control over federal funds to local

schools was underlined in his telegram of April 8, 1965 to

Commissioner Keppel, which read in part (Meadows' testimony,

Tr. 167-68):

The Alabama State Superintendent of Education

as Chief Constitutional Education Officer has

signed every agreement for federal funds for education in this state without any countersigning

or approval of any board, body, or agent since

1917. Your suggestion not to accept my signing

Title VI Civil Rights Act state agreement is a

complete violation of 48 years of practice in

Alabama.

23/ See Code of Ala., Tit. 52, §174.

20

Nor is failure to make satisfactory reports the only

ground for the cut-off of all state funds. Code of Ala., Tit.

52, §544 compels the cut-off of all state funds to local school

systems which fail to comply with the state statutory require

ments of Bible reading (Code of Ala., Tit. 52, §§542-43) and

temperance instruction (Code of Ala., Tit. 52, §536). Moreover,

Code of Ala., Tit. 52, §551 compels cut-off of all state funds

to public schools which fail to comply with the state statu

tory requirements for the proper display of the flag (Code of

24/

Ala., Tit. 52, §§549-50).

B. Racially Discriminatory Exercise Of The Control.

The defendants* discretion in the allocation of Minimum

Program funds has been directed toward the promotion of segre

gation, notably faculty segregation. The most recent abuse

of this discretion occurred in October, 1966, when defendant

Meadows sought to induce Tuscaloosa County Superintendent

Elliott and other local superintendents to resegregate their

faculties by offering them additional teacher units (Defen

dants* Exhibit 5; Government's Exhibit 97; Meadows' testimony,

Tr. 68-71) .

Just as Minimum Program funds have been employed to

reinforce segregation and induce resegregation, vocational

education funds have been employed to reward local non-compliance

with federal desegregation requirements. Bibb County is an

outstanding example. In 1966-67, after federal aid to Bibb

County was terminated for non-compliance with Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, defendant Meadows used state money

to more than offset the lost funds (Defendants' Exhibit 70, p.

109; Government's Exhibit 143). Defendant Meadows was then able

24/ Although the sanction of withdrawal of state funds is not

made explicit. Code of Ala., Tit. 52, §545 commands the schools

to provide instruction in the Constitution of the united States.

21

to cite this case to the Alabama Legislature as an example

that "the State has already replaced federal funds in these

school systems [not eligible for federal aid] out of funds

over and above that necessary for matching federal funds"

25/(Plaintiffs' Exhibit 8, p. 3).

Not only have state funds been employed by the defendants

as inducements to, and rewards for, maintaining segregation,

but the threat of their withdrawal has also been employed. It

requires little subtlety to appreciate that the defendants'

continued "requests" for information on desegregation were

nothing more than reminders of state power to local authorities

guilty of attempts at desegregation in excess of the minimum

federal requirements. Thus, the threatened cut-offs of all

state funds to the 17 local superintendents for failure to

immediately respond to the defendants' "requests" for informa

tion must be seen as part of the total fabric of the defendants'

campaign against desegregation.

Finally, even under defendant Meadows' pre-Brown defini

tion of "discrimination" (see Note 6, supra), the defendants

have committed federal constitutional violations in their

administration of state funds. The defendants have knowingly

allowed Negro students to be short-changed by local school

authorities in the enjoyment of Minimum Program funds*

During the 1963-64 school year, such maladministration

was impossible because teacher units were computed separately

for each race and the local systems were required to use the

funds allocated to each race exclusively for that race (Stone

deposition, U.S. Ex. 16, p. 2). The Wilcox County superinten

dent requested Dr. Meadows to change this rule, saying: "I

think you can easily see the advantage in a system such as ours

25/ Defendant Wallace told Bibb County Superintendent Pratt

that he was very anxious to see further vocational units allotted

to his system by the State (Pratt deposition, p. 47). The

schools of Bibb County are still completely segregated (Pratt deposition, p. 18).

22

where we have allotted only 26 teacher units

162 of another if we can account for this on

(Government's Exhibit 138). Dr. Meadows, on

replied:

of one race and

an overall basis"

October 26, 1964,

The use of Negro children teacher units

to employ white teachers in white schools (1)

will result in the court assigning the Negro

children to said white schools, [and] (2) will

show Negro teachers and our Negro supporters

that the white people in official positions

do not intend to treat Negro pupils either

justly or fairly and thereby jeopardise their

support . . . . (Government's Exhibit 139).

Notwithstanding this pronouncement, in 1965 the rule was

in fact abandoned. Local school boards are now permitted to

use teacher units earned in Negro schools to hire teachers for

white schools. Director Layton's testimony on this matter merits

examination (Tr. 217-19):

Q. . . . [T]here is one thing I want to clarify;

you have determined the teacher units earned

on the basis of the teachers that each school

within the system is entitled to? right?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. By your formula?

A. Yes, sir.

O. But those units are paid out regardless of how the

teacher units are split up back at the . . . local

school system level once the monies are received?

A. This is a matter for — this is for the local Board

to determine — to the entire system as a whole.

Q. All right, one last question on this . . . Sup

pose you have two high schools within the system,

each of them having three hundred students, and

each of them being exactly the same type of build

ing in terms of brick and approved, et cetera, and

accreditation, they are both accredited by the

Southern Association; each of those schools would

have the same number of teacher units, wouldn't

they?

A. If they had three hundred A.D.A., average daily

attendance —

Q. Three hundred A.D.A. in each school?

A. — they would have the same number of earned

teacher units, as far as our calculations are

concerned.

Q. All right? and let's just assume for the purposes of this examination that each school,

according to your formula, got ten teacher

units; all right?

23

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, if the school system saw fit to give one

school fifteen teachers and the other school

five teachers — in other words, if they took

their ten for each school, added them up to

twenty, but then re-allocated them at the dis

trict level, giving one school fifteen and

another five, you would continue to pay out

for twenty units throughout the year; is that

not correct?

A. As long as the system employed the total number

earned and paid them —

Q. Yes.

A. — on the allocation schedule, we would; yes,

sir; we do not exercise control over the dis

tribution of the teachers into the various

schools.

Q. But your records do reflect how the teachers

are deployed, do they not?

A. Our — our — yes, sir; we calculate from this,

because this is the beginning; we have to do

this; this is necessary; there is no other way

to do it.

Q. But during the year, you would know at any given

point in time, from records sent in to you by the

local system, the numbers of teachers and, indeed,

the exact identity of each teacher within each

school, wouldn't you?

A. Yes, sir; employed within that school.

The defendants cannot be unaware that they are presently

subsidizing racial discrimination. For example, the defen

dants can hardly fail to know that the average pupil-teacher

ratio in Negro schools is higher than in white schools; the

defendants' own records reveal this (Government's Exhibit 137;

Appendix c to Government's Brief, Tables I and II).

The discrimination against Negro students in Alabama is

traceable in other ways as well. The per-pupil valuation of

school buildings and contents is $607.12 per white pupil as

compared to $295.40 per Negro pupil (Government's Exhibit 172).

And over 25% of the Negro high schools in Alabama are un

accredited, as compared with only 3.4% of the white high schools

26/

(see 1966-67 Educational Directory).

26/ For other examples of disparity, see the Government's

Brief, pp. 114-16.

24

Ill

The Defendants Control instructional Programs

And Policies And Have Exercised That Control

To Promote And Maintain Segregation And Other

Forms Of Racial Discrimination.

Although this area of defendants' control is highly

important, it may nevertheless be treated briefly. Defendants

cannot deny that they have bent every effort short of obvious

contempt of federal court orders to enforce their statewide

policy of faculty segregation. See, pp. 9-14, supra. Moreover

as the Government's brief adequately illustrates (pp. 82-95?

111-13), the defendants have exercised their control over

27/

numerous instructional programs to promote segregation and

other forms of racial discrimination. This being so, the only

matter left for discussion is the appropriate relief (see Part

2, infra).

27/ Vocational and exceptional children teaching programs ?

teacher institutes; in-service training programs; teacher certi

fication? and trade schools and junior colleges.

25

IV

The Defendants Control School Construction And

Consolidation Programs And Policies And Have

Exercised That Control To Promote And Maintain

Segregation And Other Forms Of Racial Discrimi

nation.

That the State Department of Education has an important

role in establishing and locating public schools is documented

in the preface to its 1965 REPORT OF A PARTIAL SURVEY OF THE

28/

CLARKE COUNTY SCHOOLS:

For more than 35 years the State Depart

ment of Education has maintained a survey

staff which has provided assistance to county

and city superintendents and their boards of

education in the solution of various types

of educational problems. One of the most

important aspects of the service has been

the location of permanent centers for ele

mentary, junior and senior high schools.

(Emphasis supplied)

This role has not been a salutary one. It is a sad

fact that every public school in the State of Alabama has been

planned and constructed as a segregated school -*■ for white

children or for Negro children — pursuant to the supervision,

direction and control of the State Department of Education.

In light of the Government's detailed analysis of the role

of the State of Alabama in maintaining and perpetuating segre

gated school systems through its control over abandonment, con

solidation, site selection and construction of schools within the

several school district of Alabama, no purpose would be served

29/

in discussing the matter at length here. The defendants'

role in perpetuating the dual system, amply supported by the

evidence summarized in the Government's brief, is buttressed by

the testimony of Dr. George Layton, Director of the Division of

Administration and Finance, which was not transcribed at the

23/ Government's Exhibit 144B# p. 2.

29/ See Government's brief, pp. 52-75.

26

time the Government's brief was written (Transcript of November

30, 1966, pp. 176-234), Dr. Layton testified (Tr. 210):

Q. Are you aware of any school that has been

built in the State of Alabama, public ele

mentary, junior, or senior high school, which your Department has not issued a final approval

for the last five years?

A. There may — there may have been; I would not

say that it has not been.

Q. Do you know of any?

A. I don't know of — right off hand, I don't;

no, sir.

Q. Furthermore, do you know of any school within

the last five years that has been built on a

site which had not previously been approved by

your Department?

A. I am not aware of this; no, sir.

Q. All right. So it is fair to say, at least,

that predominantly all sites for new school

construction are approved by your Department?

A. Yes, sir; in general they are; we — we hope

they are.

School sites or locations are not selected until com

pletely separate analyses, by race, are made of the systems’

facilities by the State Department of Education. These surveys

include: an inventory of the number, condition and capacity of

each existing school facility; the taking of a census of school

age children from which a "dot map" is prepared which reflects,

by race, the residence of each school age child; and a forecast

of the number of school age children, by race, anticipated to

be in attendance in the system within the foreseeable future.

Two such analyses are always made — one for white children and

30/one for Negro children. Standards establishing the minimum

attendance and minimum acreage for each elementary, junior high

and senior high school have been promulgated by the State Board

30/ Dr. Layton testified (Tr. 211):

Q. . . . [H]as there ever been a survey,

to your knowledge, up to the current day,

which has not included clusters or dots

showing densities of children by race?

A. Not to my knowledge; I don't think so.

27

31/ 32/of Education. Using these rules as benchmarks, the State

Department of Education survey personnel analyze the size, age

and capacity of existing school facilities, by race, in light

of the number and location of students attending the system

(as indicated on the "dot map").

To this day, the State Department of Education considers

each school system as two school systems (see Government's

Exhibit 147). School consolidations are recommended only between

schools for children of the same race (Dr. Layton's testimony,

Tr. 233-34). The surveys of Negro students and the facilities

provided for them are in practice unrelated to the surveys of

white students and the facilities provided for them. Thus, the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit correctly concluded that

"the location of Negro schools with Negro faculties in Negro

neighborhoods and white schools in white neighborhoods cannot

be described as an unfortunate fortuity: It came into existence

as state action and continues to exist as racial gerrymandering,

33/

made possible by the dual system." This conclusion accurately

summarizes conditions in each of the one hundred and eighteen

public school districts of Alabama. These conditions were

intentionally designed, financed and implemented — and continue

to exist — as a result of the concerted activities of the

Alabama State Department of Education.

31/ See, e.g.. Government’s Exhibit 144B, Report of a Partial

Survey of the Clarke County School System, p. 11; Government's

Exhibit 152.

32/ Government's Exhibit 144B, Note 31, supra, p. 11:

"Obviously, exceptions should be made only in extreme cases and

after careful study."

33/ United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 5th

Cir., December 29, 1966, slip op. p. 32.

28

V.

The Defendants Control School Transportation

Programs And Policies And Have Exercised That

Control To Promote And Maintain Segregation And

Other Forms Of Racial Discrimination.

In its 1964 opinion, the Court found that the defendants

exercise considerable control over local school bus transporta

tion (231 F. Supp. at 751). As the Government's brief demon-

strates (pp. 96-98), that control continues to exist.

theIn 1964, the Court cited/racially discriminatory exercise

of that control as exemplary of the fact that "the State of

Alabama has operated and presently operates a dual school system

based upon race" (231 F. Supp. at 750). Defendants cannot deny

that the Court's holding is equally true today (see Government's

35/

brief, pp. 99-103).

This leaves only the question of effective relief to dis

establish this abuse of state power, discussed in Part 2, infra.

34/ For example, approximately 97 percent of the total cost of

local school transportation programs is paid for by the State

(See Government's Exhibit 127; Defendants' Exhibit 70, p. 21).

35/ Not only are busses segregated, but the percentage of Negro

busses over 10 years old (when they should be discarded) is nearly

3 times that of white busses (Government's Appendix C, Table V).

29

PART 2

Nature Of The Relief

In 1964, this Court admonished these defendants:

"Needless to say, it is only a question of time until [their]

illegal and unconstitutional support of segregated school

systems must cease. These State officials and the local school

officials are now put on notice that within a reasonable time

this Court will expect and require such support to cease" (231

F. Supp. at 756). The Court's expectations have not been ful

filled. Mere "notice" has not been enough. "Illegal and un

constitutional support" continues to be the sole guideline