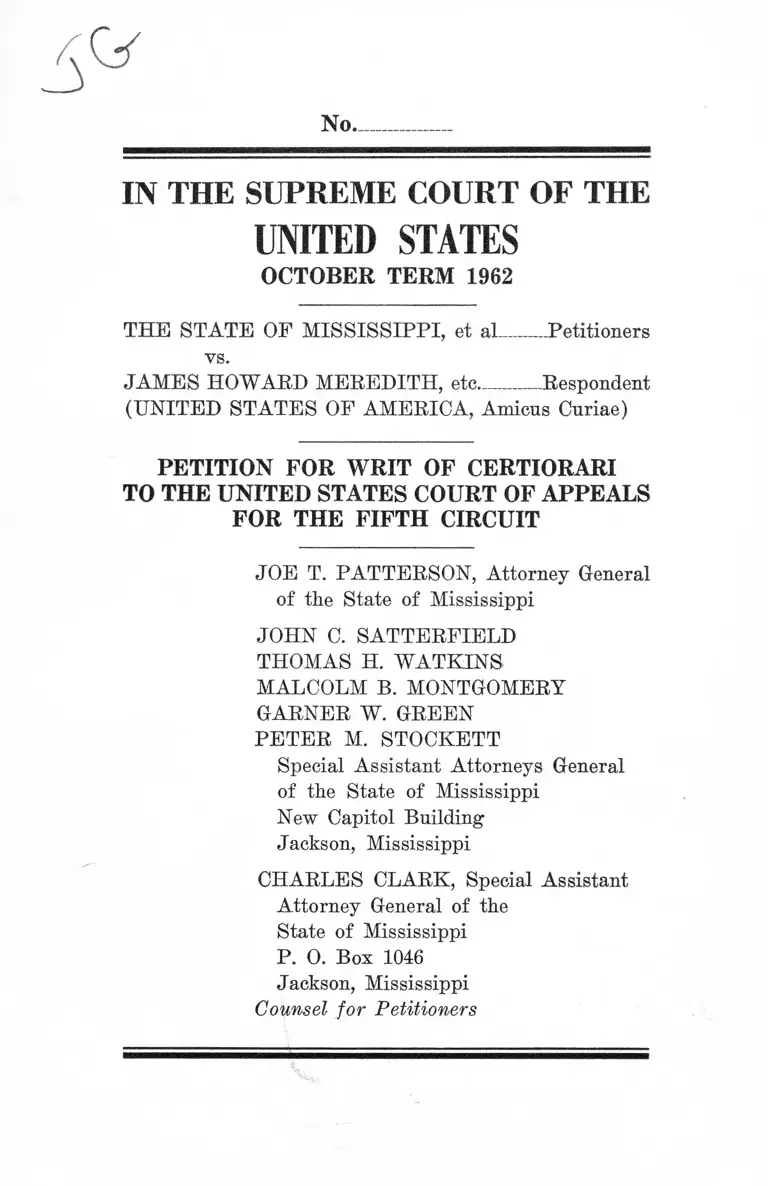

Mississippi v. Meredith Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

December 12, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mississippi v. Meredith Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1962. 2a95e8e7-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ec144698-25fc-4c6b-95dd-7da78f5b36d3/mississippi-v-meredith-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No.

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM 1962

THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI, et al_____Petitioners

vs.

JAMES HOWARD MEREDITH, etc______ Respondent

(UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Amicus Curiae)

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

JOE T. PATTERSON, Attorney General

of the State of Mississippi

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD

THOMAS H. WATKINS

MALCOLM B. MONTGOMERY

GARNER W. GREEN

PETER M. STOCKETT

Special Assistant Attorneys General

of the State of Mississippi

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi

CHARLES CLARK, Special Assistant

Attorney General of the

State of Mississippi

P. 0. Box 1046

Jackson, Mississippi

Counsel for Petitioners

X.

I N D E X

TABLE OF CASES ______________________

OTHER AUTHORITIES____________________

PE TITIO N _______________________________________ 1

A. OPINIONS BELOW _______________________ 2

B. JURISDICTIONAL GROUNDS ____________ 2

C. QUESTIONS PRESENTED ________________ 5

D. PERTINENT CONSTITUTIONAL

PROVISIONS & STATUTES _____________ 7

E. STATEMENT OF THE C A S E _____________ 9

1. Jurisdiction _____________________________ 9

2. Pleading's and Proceedings ______________ 9

3. Statement of the Pacts ___________________ 11

F. ARGUMENT ______________________________ 14

I. THE COURT OF APPEALS SO FAR

DEPARTED FROM THE ACCEPT

ED, USUAL AND STATUTORY

COURSE OF JUDICIAL PROCEED

INGS AS TO CALL FOR AN EXER

CISE OF THIS COURT’S POWER

OF SUPERVISION _________________ 14

a. The United States, as Amicus Cur

iae, Improperly Assumed Control

and Direction of Private Litigation _ 15

b. The Court of Appeals Cannot Issue

Personal Writs Across State Lines

Returnable Outside of the State

Where Service Thereof Was Made__ 16

c. Intervention in An Appellate Court

as a Plaintiff to Assert a Permis

sive and Independent Claim Against

New Defendants is Unprecedented__ 17

Page

11.

d. The Court of Appeals Usurped the

Jurisdiction and Functions of the

District Court in These Proceed

ings ______________________________ 18

II. THE ISSUANCE OF THE TEMPO

RARY RESTRAINING O R D E R S

AND THE PRELIMINARY INJUNC

TION O R D E R AGAINST THE

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI VIOLAT

ED THE ELEVENTH AMEND

MENT TO THE CONSTITUTION

OF THE UNITED STATES AND

WAS CONTRARY TO THE HOLD

ING OF THIS COURT IN THE

CASE OF MISSOURI V. F1SKE, 290

U. S. 18 _____________________________ 22

III. NEITHER THE APPELLANT NOR

THE UNITED STATES MET THE

BURDEN OF P R O V I N G THE

FACTS ESSENTIAL TO ESTAB

LISH SUCH JURISDICTION AS

THEY CLAIMED WAS VESTED IN

THE COURT OF APPEALS _______ 28

IV. THE ACTIONS OF THE AMICUS

CURIAE CONSTITUTE AN ASSER

TION BY IT OF INDIVIDUAL AND

PRIVATE FOURTEENTH AMEND

MENT RIGHTS CONTRARY TO

THE DECISIONS OF THIS COURT

IN SHELLEY V. KRAEMER, 334

U. S. 1, AND HAGUE V. C. I. 0., 307

U. S. 496

Page

30

111.

V. THE ACTIONS OF THE COURT OF

APPEALS IN CONDUCTING EN

F O R C E M E N T PBOCEEDINGS

CONFLICTED WITH THE HOLD

INGS OF THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

IN THE CASES OF DOWAGIAC

MFG. CO. V. MINNESOTA-MOLINE

PLOW CO., 124 F. 735, and MERE

DITH V. JOHN DEERE PLOW CO.,

244 F. 2d 9 __________________________ 31

VI. THE SHOW CAUSE CITATIONS

ISSUED TO GOVERNOR BARNETT

AND LT. GOVERNOR JOHNSON

WHICH REQUIRED THEM TO AP

PEAR OUTSIDE OF THE STATE

WITHIN LESS THAN FORTY-

EIGHT HOURS FROM THE IN

STANT OF ATTEMPTED SERVICE

OF SUCH CITATIONS DID NOT

ACCORD CONSTITUTIONAL AND

PROCEDURAL DUE PROCESS TO

THESE PARTIES __________________ 34

VII. THE JUDICIAL BRANCH OF THE

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT CAN

NOT MANDATORILY ENJOIN THE

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OF A STATE

TO PERFORM FUTURE DISCRE

TIONARY A C T S ____________________ 35

VIII. THE ISSUANCE OF THE PRELIM

INARY INJUNCTION AND THE

CONTEMPT JUDGEMENTS B Y

THE COURT OF APPEALS RE-

Page

IV.

Page

SULTED IN THE DECISION OF IM

PORTANT QUESTIONS OF FED

ERAL LAW WHICH HAVE NOT

BEEN BUT SHOULD BE DECIDED

BY THIS COURT ______ __________ 41

IX. THE ISSUANCE OF THE TEMPO

RARY RESTRAINING ORDERS

AND THE PRELIMINARY INJUNC

TION ORDER BY THE COURT OF

APPEALS RESULTED IN THE DE

CISION OF IMPORTANT STATE

QUESTIONS IN A W AY THAT CON

FLICTED W I T H APPLICABLE

STATE LAW _______________________ 46

X. THE PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

WAS SO BROAD, VAGUE, GENER

AL AND INDEFINITE AS TO BE

IMPROVIDENT AND IMPROPER .... 48

XI. THE CIVIL C O N T E M P T PRO

CEEDINGS AND ORDERS BY THE

COURT OF APPEALS WERE IM

PROPER ____________________________ 49

a. The United States Should Not Have

Been Permitted to Intervene In a

Private Law Suit to Invoke Court

Proceeding's In Civil Contempt ____ 49

b. A Contempt Judgment Cannot Im

pose Both Fine and Imprisonment

For a Single Course of Action Al

leged to Constitute Civil Con

tempt 50

Y.

Page

c. No Pinal and Unremittable Fine

Other Than a Compensatory Fine

Payable to the Complaining Party

May Be Assessed in a Civil Con

tempt Judgment __________________ 51

d. A Civil Contempt Fine Cannot Be

Imposed In The Absence of a Show

ing of Damages by the Party to

Whom the Fine is Payable_________ 53

e. An Order Adjudging Civil Con

tempt Cannot Impose Purge Terms

Which Broaden the Scope of the

Injunction on Which the Contempt

Citation Was Based ______________ 55

f. The Civil Contempt Judgments

Against the Governor and the

Lieutenant Governor Are Now Moot

and Should Be Dismissed _________ 56

CONCLUSION ___________________________________ 57

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE __________________ 58

INDEX TO APPENDIX _________________ ai

APPENDIX _____________________________________ A l

VI.

TABLE OF CASES

Alemite Mfg. Corp. v. Staff, (CA 2) 42 F. 2d 832 ___ 29

Arhens v. Clark, 335 U. S. 188, 92 L. Ed. 1898, 68

S. Ct. 1443 ____________________________________ 17

Babee-Tenda Corp. v. Sebarco Mfg. Co., 156 F.

Supp. 582 _____ ________________________________ 54

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249, 73 S. Ct. 1031,

97 L. Ed. 1586 ________________________________ 21

Bisbee v. Drew, 17 Fla, 6 7 _________________________ 39

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., (CA 5) 292 F.

2d 4 ___________________________________________ 20

Boylan v. Detrio, (CA 5) 187 F. 2d 375 ____________ 53

Brownlow v. Schwartz, 261 U. S. 216, 67 L. Ed. 620,

43 S. Ct. 263 __________________________________ 57

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 191 F. Supp.

811 -------------------------------------------------------------------- 49

Champion Spark Plug Co. v. Reich, 98 F. Supp. 242 __ 54

City National Bank v. Hunter, 152 U. S. 512, 38

L. Ed. 534, 14 S. Ct. 675 _________________________ 32

Chase National Bank v. Norwalk, 291 U. S. 431, 78

L. Ed. 894, 54 S. Ct. 475 _________________________ 29

Cliett v. Hammonds, (CA 5) 305 F. 2d 565 _________ 52

Debs, In Re., 158 U. S. 564, 39 L. Ed. 1092, 15 S. Ct.

900 ____________________________________________ 17

Dennett, In Re., 32 Maine 508 _____________________ 39

Donnelly v. Roosevelt, 259 N. 4, 356 ________________ 39

Dowagiac Mfg. Co. v. Minn.-Moline Plow Co.,

(CA 8) 124 F. 735 _____________________________ 35

Page

V ll.

Doyle v. London Gty. and Acc. Ins. Co., 204 IT. S.

599, 51 L. Ed. 641, 27 S. Ct. 313__________________ 52

Egan v. Aurora, 367 U. S. 514, 5 L. Ed. 2d 741, 81

S. Ct. 684 ______________________ _______________ 22

Estes v. Potter, (CA 5) 18 3 F. 2d 865, Cert. Den. 340

U. S. 920, 95 L. Ed. 664, 71 8. Ct. 356 ____________ 50

Fitts v. McGhee, 172 17. S. 516, 43 L. Ed. 535, 19

S. Ct. 269 _______________________________________ 23

Glidden Co. v. Zdanok, ------U. S.------ , 8 L. Ed. 2d

671 82 S. Ct. 1459 _____________________________ 47

Gompers v. Bucks Stove & Range Co., 221 U. S.

418, 55 L. Ed. 797, 31 S. Ct. 492 ___________ 49, 53, 57

Hague v. CIO, 307 IT. S. 496, 83 L. Ed. 1423, 59 S.

Ct. 954 _____________ _______________________ 30

Hanes Supply Co. v. Valley Evaporating Co. (CA 5)

261 F. 2d 29____________________________ _____ 17

Hans v. Louisiana, 134 IT. S. 1, 33 L. Ed. 842, 10 S.

Ct. 504 _________________________________________ 24

Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U. S. 167, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1152,

79 S. Ct. 1025 _______________ _________________ 47

Hawkins v. Governor, 1 Ark. 570 __________________ 39

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242, 81 L. Ed. 1066, 57

S. Ct. 732 _________________ 49

Hess v. Pawloski, 274 IT. S. 352, 71 L. Ed. 1091, 47

S. Ct. 632 __________________ 17

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, (CA 5) 258

F. 2d 730 ____________________ 18

Houston Railroad Co. v. Randolph, 24 Texas 317____ 39

Illinois, People of v. Bissell, 19 111. 229 _____________ 39

Page

V lll.

Illinois, People of v. Yates, 40 111. 126_____________ 39

Leman v. Krentler-Arnold Hinge Last Co. 284 U. S.

448, 76 L. Ed. 389, 52 S. Ct. 238 _________________ 57

Louisiana Land & Exploration Co., v. State Mineral

Board (CA 5) 229 F. 2d 5 _________________________ 23

Louisiana Power & Light Co. v. Thibodaux, 360 H. S.

25, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1058, 79 S. Ct. 1070 ________________ 47

Louisiana, State of v. Warmoth, 22 La. Ann. 1 ____ 39

Low v. Towns, 8 Ga. 360 _________________________ 39

McComb v. Jacksonville Paper Co., 336 U. S. 187,

93 L. Ed. 599, 69 S. Ct. 497 _____________________ 53

McCrone v. U. S., 307 U. S. 61, 83 L. Ed. 1108, 59 S.

Ct. 685 _________________________________________ 54

McNutt v. General Motors Acceptance Corp., 298

U. S. 178, 56 S. Ct. 780, 80 L. Ed. 1135__________ 29

Mauran v. Smith, 8 R. I. 192______________________ 39

Meredith v. John Deere Plow Co., (CA 8) 244 F. 2d

9, Cert. Den. 355 U. S. 831, 2 L. Ed. 2d 43, 78

S. Ct. 44 _______________________________________ 34

Meridian v. So. Bell T. & T. Co., 358 U. S. 639, 3 L.

Ed. 2d 562 79 S. Ct. 455 _______________________ 47

Mississippi, State of v. McPhail, 182 Miss. 360, 180

So. 387 ________________________________________ 45

Missouri v. Fiske, 290 U. S. 18, 78 L. Ed. 145, 54 S.

Ct. 18 ______________________________________ 24, 27

Missouri, v. Governor 39 Mo. 388 __________________ 39

Missouri, Inquiries by Governor of, 58 Mo. 369 ____ 39

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167, 5 L. Ed. 2d 492, 81

S. Ct. 473

Page

22

IX.

Page

Mutual Life Ins. Co. of N. Y. v. Holly, (CA 7) 135

F. 2d 675 ______________________________________ 32

New Jersey, State of v. Governor, 1 Dutch. 331____ 39

New York v. U. S., 326 XL S. 572, 90 L. Ed., 326, 64

S. Ct. 1286 ________________ ______ ______________ 47

Nordstrom v. Wahl, (CA 7) 41 F. 2d 910___________ 54

Nye v. IT. S., 313 U. S. 33, 85 L. Ed. 1172, 61 S. Ct.

810 ________________________ 54

Ohio Oil Company v. Thompson, (CA 8) 120 F. 2d

831 ___________________________________________ 832

Omaha Electric Light & Power Co. v. Omaha, (CA 8)

216 F. 848 __________________________________ ____ 31

Parker v. U. S., (CA 1) 153 F. 2d 66, 163 A. L. R. 379_ 53

Penfield Co. v. S. E. C., 330 TJ. S. 585, 91 L. Ed. 1117,

67 S. Ct. 918 ___________________________________ 51

Phillips v. U. S., 312 TJ. S. 246, 85 L. Ed. 800, 61 S.

Ct. 480 ________________________________________ 20

Regal Knitwear Co. v. N. L. R. B., 324 U. S. 9, 89

L. Ed. 661, 65 S. Ct. 478 __________________________ 29

Republic of Peru, Ex Parte, 318 U. S. 578, 87 L. Ed.

1014, 63 S. Ct. 793 _________________ 31

Rice v. Governor, 19 Minn. 103_____________________ 39

Roller v. Holly, 176 U. S. 398, 44 L. Ed. 520, 20 S. Ct.

410 ____________________________________________ 35

Shelly v. Kraemer, 344 U. S. 1, 92 L. Ed. 1161, 68 S.

Ct. 836 _________________________________________ 30

Scott v. Donald, 165 IT. S. 107, 41 L. Ed. 648, 17 S.

Ct. 262 _________________________________________ 29

X.

Sibbad v. IT. S., 37 U. S. 488, 12 Pet. 488, 9 L. Ed.

1176 ------------------------------------------------------------------ 32

Smith v. American Asiatic Underwriters (CA 9)

134 F. 2d 233 __________________________________ 18

South Carolina v. U. S., 199 U. S. 437, 50 L. Ed. 261,

26 S. Ct. 110 ___________________________________ 47

Southerland v. Governor, 29 Mich. 320 ____________ 39

Star Bedding Co. v. Englander Co., (CA 8) 239 F.

2d 537 _________________________________________ 56

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U. S. 378, 77 L. Ed. 375,

53 S. Ct. 190 ___________________________________ 42

Stone v. Interstate Natural Gas Co., (CA 5) 103 F.

2d 544, Aff., 308 U. S. 522, 84 L. Ed. 442, 60 S. Ct.

292 -------------------------------------------------------------------- 22

Strutwear Knitting Co. v. Olsen, 13 F. Supp. 384 42

Terminal E. E. Assn, of St. Louis v. U. S., 226 U. S.

17, 69 L. Ed. 150, 45 S. Ct, 5 ____________________ 56

Texas v. White, 74 U. S. 700, 19 L. Ed. 227 _________ 47

Turner v. Bank of North America 4 Dali. 8, 1 L. Ed.

718 ------------------------------------------------- 29

Turnpike Co. v. Brown, 8 Baxter 490 _____________ 39

U. S. v. Alabama, 171 F. Supp. 720, (CA 5) 267 F.

2d 808 _________________________________________ 30

U. S. v. Detroit, 355 U. S. 466, 2 L. Ed. 2d 424, 78

S. Ct. 474 _____________________________________ 47

CJ. S. v. E. I. Du Pont, 366 U. S. 316, 6 L. Ed. 2d 318,

81 S. Ct. 1243 __________________________________ 32

U. S. v. Mayer, 235 U. S. 55, 59 L. Ed. 129, 35 S. Ct.

16

Page

31

si.

U. S. v. Montgomery, 155 F. Snpp. 633 _____________ 50

U. S. v. Onan, (CA 8) 190 F. 2d 1, Cert. Den. 342

('. S. 864 96 L. Ed. 654, 72 S. Ct. 112_____________ 53

U. S. v. United Mine Workers, 330 U. S. 258, 91 L.

Ed. 884, 67 S. Ct. 677 ___________________________ 52

Vicksburg & Meridian R. R. Co. v. Lowry, 61 Miss.

102, 48 Am. Rep. 76 ____________________________ 40

Wenborn-Karpen Drier Co. v. Cutler Dry Kiln Co.

(CA 2) 292 F. 861 _____________________________ 18

Wooten v. Bomar, (CA 6) 266 F. 2d 27_____________ 32

Wuchter v. Pizzutti, 276 U. S. 13, 72 L. Ed. 446, 48 S.

Ct. 259 ________________________________________ 17

Yanish v. Barber (CA 9) 232 F. 2d 932 ____________ 53

Page

XU .

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Rule 4 (f) ___________________________________ 16, 17

Rule 24 (a) - (c) ______________________________ 18

Rule 65 (d) ____________________________________ 48

Mississippi Code of 1942

Section 3975 ___________________________________ 36

Section 3978 ___________________________________ 36

Section 6726.7 __________________________________ 36

Section 8082 ___________________________________ 36

Section 8576 ___________________________________ 36

Regular Legislative Session of 1962

House Bill No. 403 _____________________________ 36

Senate Bill No. 1710 ___________________________ 36

Mississippi Constitution of 1890

Article 4, Section 50 ___________________________ 37

Article 5, Section 116 __________________________ 35

Section 119 __________________________ 35

Section 123 __________________________ 35

Article 9, Section 217 __________________________ 36

United States Code

Title 10, Section 332, 333 _______________________ 44

Title 18, Section 401 _________________________50, 51

Section 402 ___________________________ 50

Title 28, Section 547 (a), (b) & (c) __________16, 44

Section 713 (d) ______________________ 44

Section 1254 __________________________ 5

Section 1291 __________________________ 18

Page

Page

Section 1345 ________________________ 19

Section 1391 (b) ______________________ 19

Section 1404 (a) ______________________ 19

Section 1651 ________________________ 31

Section 2071 ________________________ 8

Section 2101 (c) ______________________ 5

Section 2281 _______________________42, 47

Section 2403 ________________________ 18

Title 42, Section 1983 ________________________ 22

United States Constitution

Article III Section 2, Clause 2 __________________ 19

Article IV, Section 4 ___________________________ 38

Amendment V __________________________________ 8

Amendment X __________________________________ 47

Amendment XI _____________________________22, 24

Rules of the U. S. Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

Rule 8 _________________________________________ 20

Rule 9 _________________________________________ 16

Rule 10 ________________________________________ 20

42 ABA Journal 833 _____________________________ 21

44 ABA Journal 113 _____________________________ 45

Barron & Holtzhoff, Federal Practice and Procedure

§597 ___________________________________________ 18

36 C. J. S. 784 ____________________________________ 38

7 Cong. Deb. 21st. Cong. 2d Sess. Cols. 560-561 _____ 51

Cyclopedia of Federal Procedure, 3rd Ed. Vol. 15,

Contempt §87.23 ________________________________ 56

High’s Extraordinary Legal Remedies 3rd. Ed. p.

128 ____________________________________________ 41

Report of Advisory Committee, Vol. 3-A, p. 542-4 __ 17

X l l l .

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM 1962

THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI, et al______ Petitioner

V S.

JAMES HOWARD MEREDITH, etc______ Respondent

(UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Amicus Curiae)

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

The State of Mississippi; Ross R. Barnett, Governor

of the State of Mississippi; Joe T. Patterson, Attorney

General of the State of Mississippi; T. B. Birdsong,

Commissioner of Public Safety of the State of Missis

sippi; Paul G. Alexander, County Attorney of Hinds

County, and William R. Lamb, District Attorney of

Lafayette County; J. Robert Gilfoy, Sheriff of Hinds

County, and J. W. Ford, Sheriff of Lafayette County;

William D. Rayfield, Chief of Police of the City of

Jackson, James D. Jones, Chief of Police of the City

of Oxford, and Walton Smith, Constable of the City

of Oxford, hereinafter referred to as “ Petitioners” ,

pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review the judg

ments and orders of the U. S. Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit hereinafter set out in Section B-l of

this Petition.

2

A.

OPINIONS BELOW

No opinions were delivered in the Court of Appeals

in connection with the orders and other procedures re

quested to be reviewed by this Petition. A Petition

for a Writ of Certiorari to said Court was previously

filed and docketed in this Supreme Court as Cause

No. 347, October Term, 1962, seeking a review of the

final decision and other matters in the case of Meredith

v. Fair, et al. This Petition was denied by this Court

on October 8, 1962. The present Petition does not cover

any matters presented to this Court in the former

Petition for Certiorari.

B.

JURISDICTIONAL GROUNDS

1. The sixteen Judgments and Orders of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit sought

to be reviewed were dated and entered as set out be

low:

(a) Order designating the United States as Amicus

Curiae.

Dated and Entered: September 18, 1962.

(A. 18)

(b) Order enjoining Appellees from:

(1) Enforcing Senate Bill No. 1501, enacted

September 20, 1962, against Appellant, Mer

edith ;

(2) Taking any steps to effectuate the misde

meanor conviction of Appellant of Sep

tember 20, 1962; and

3

(3) Complying with a State Court Injunction

issued September 19, 1962 by the Chancery

Court of Jones County, Mississippi.

Dated and Entered : September 20, 1962.

(A. 19)

(c) Show Cause Order in Civil Contempt directed

to all members of Board of Trustees on appli

cation of Amicus Curiae.

Dated and Entered-. September 21, 1962.

(A. 21)

(d) Show Cause Order in Civil Contempt directed

to all Appellees on application of Appellant.

Dated and Entered: September 22, 1962.

(A. 23)

(e) Order requiring Trustees to take enumerated

actions.

Dated and Entered: September 24, 1962.

(A. 24)

(f) Temporary Restraining Order directed to the

State of Mississippi, Governor Barnett and oth

ers on application of Amicus Curiae.

Dated and Entered: September 25, 1962.

(A. 26)

(g) Order adding Governor Barnett as new party

defendant.

Dated and Entered: September 25, 1962.

(A. 30)

(h) Temporary Restraining Order directed to Gov

ernor Barnett and others on application of Ap

pellant.

Dated and Entered: September 25, 1962.

(A. 31)

4

(i) Show Cause Order in Civil Contempt directed to

Governor Barnett on application of Amicus

Curiae.

Dated and Entered: September 25, 1962.

(A. 33)

(j) Show Cause Order in Civil Contempt directed

to Governor Barnett on application of Appellant.

Dated and Entered: September 26, 1962.

(A. 35)

(k) Show Cause Order in Civil Contempt directed

to Lt. Governor Johnson on application of Amicus

Curiae.

Dated and Entered: September 26, 1962.

(A. 36)

(l) Judgment of Civil Contempt against Governor

Barnett.

Dated and Entered: September 28, 1962.

(A. 38)

(m) Judgment of Civil Contempt against Lt. Gov

ernor Johnson.

Dated and Entered: September 29, 1962.

(A. 41)

(n) Order dismissing contempt citation as to Ap

pellants.

Dated and Entered: October 2, 1962. (A. 45)

(o) Order continuing hearing on Motion for Temp

orary Injunction.

Dated and Entered: October 2, 1962. (A. 46)

(p) Judgment and Order granting Preliminary In

junction.

Dated and Entered: October 19, 1962. (A. 46)

5

2. No orders have been sought or entered respecting

rehearing or extension of time within which to file

this petition.

3. Jurisdiction to review each of these orders of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

is conferred upon this Honorable Court by Title 28 USC,

§1254 (1) and §2101 (c). (A. 4, 5).

C.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Did the Court of Appeals so far depart from the

accepted, usual and statutory course of judicial pro

ceedings as to call for an exercise of this Court’s power

of supervision in the following particulars:

(a) Was the United States as Amicus Curiae, im

properly and unnecessarily allowed to assume

control and direction of private litigation?

(b) Can a Court of Appeals issue a personal writ

across state lines returnable outside of the state

where service thereof was made?

(c) Can a party intervene in an appellate court as a

plaintiff to assert a permissive and independent

claim against new defendants?

(d) Did the Court of Appeals usurp the jurisdiction

and functions of the District Court in entering

the orders set out in Section B-l above?

2. Did the issuance of the Temporary Restraining

Orders and the Preliminary Injunction Order against

the State of Mississippi violate the Eleventh Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States contrary

to the holding of this court in the case of Missouri v.

Fiske 290 US 18?

6

3. Did the appellant and the United States meet the

burden of proving all facts essential to establish the

jurisdiction which they claimed was vested in the Court

of Appeals to conduct these proceedings?

4. Did the actions of the United States, as Amiens

Curiae, amount to the assertion by it of individual and

private Fourteenth Amendment rights contrary to the

decisions of this Court in Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1,

and Hague v. CIO, 307 U. S. 496?

5. Was the conduct of the enforcement proceedings in

the Court of Appeals contrary to and in conflict with

the holdings of the 8th Circuit in the cases of Dowagiac

Mfg. Co. v. M-M Plow Co. 124 F 735 and Meredith v.

John Deere Plow Co. 244 F 9?

6. Did the Show Cause Citations to Governor Barnett

or Lt. Governor Johnson directing them to appear out

of the state within less than 48 hours from the instant

of attempted service of process accord to these parties

due process of law required by the Fifth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States?

7. Can the Judicial Branch of the Federal Govern

ment mandatorily enjoin the Chief Executive of a State

to perform future discretionary acts?

8. Did the issuance of the Preliminary Injunction and

the Contempt Judgments by the Court of Appeals de

cide important questions of Federal Law which have

not been but should be decided by this Court?

9. Did the issuance of the Temporary Restraining Or

ders and Preliminary Injunction Order by the Court

of Appeals result in the decision of important state

questions in a way that conflicted with applicable state

law?

7

10. Was the Preliminary Injunction so broad, vague,

general and indefinite as to be improvident or improper ?

11. With regard to the Civil Contempt proceedings by

the Court of Appeals:

(a) Can the United States intervene in a private law

suit to invoke court proceedings in civil contempt?

(b) Can a Civil Contempt Judgment impose both fine

and imprisonment for a single course of action

alleged to constitute civil contempt?

(c) Can a final and unremittable fine, other than

a compensatory fine payable to the complaining

party, be assessed in a civil contempt judgment?

(d) Can a compensatory civil contempt fine be im

posed absent a showing of damages by the party

to whom such fine is payable?

(e) Can an order adjudging civil contempt impose

purge terms which broaden the scope of the in

junction on which the contempt citation was

based?

(f) Should the civil contempt judgments against the

Governor and the Lt. Governor now be dismissed

as moot?

D.

PERTINENT CONSTITUTIONAL

PROVISIONS AND STATUTES

Because of the length of the provisions involved, their

citation alone is set out at this point and pertinent text

is set forth in the Appendix, as indicated.

The Constitution of the United States-.

Article III, §2, Clause 2 (A. 1)

Article IV, §4 (A. 1)

8

Amendment Y (A. 1)

Amendment X (A. 1)

Amendment XI (A. 2)

United States Code:

Title 18, use, §401 (A. 2)

§402 (A. 2)

Title 28, use, §547 (A. 3)

§713 (d) A. 4)

§1254 (1) (A. 4)

§1291 (A. 4)

§1345 (A. 5)

§1391 (b) (A. 5)

§1404 (a) (A. 5)

§2071 (A. 5)

§2101(c) (A. 5)

§2281 (A. 6)

§2403 (A. 6)

Title 42 use <51983 (A. 7).

Rules of the U. S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit :

Rule 8 (A.7)

Rule 9 (A. 7)

Rule 10-1 (A. 7)

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

Rule 4 (f) (A. 8)

Rule 24 (A. 8)

Mississippi Constitution of 1890:

Article IV, §50 (A. 9)

Article V, §116 (A. 9)

§119 A. 10)

§123 (A. 10)

9

Article IX, §217 (A. 10)

Mississippi Code of 1942:

§3975 (A. 10); §3978 (A. 12)

§6724(a) & (c) (A. 12); §6726.7 (A. 13);

§8082(a) 1-3 and (b) (A. 14); §8576, Par.

1 (A. 15);

Section 3 of HB 403, Regular Legislative Session

of 1962 (A. 16);

SB 1710, Regular Legislative Session of 1962 (A. 17).

E.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

1.

JURISDICTION

Petitioners respectfully contend that there was no

basis for Federal Jurisdiction in the U. S. Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which was the Court of

first instance for all actions brought here for review.

Petitioners contend that such jurisdiction as was as

serted by the Honorable U. S. Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit was, under the Acts of Congress and

the Constitution of the United States, possessed only

by this Honorable Supreme Court and by the Honorable

District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi.

2.

PLEADINGS AND PROCEEDINGS

On the 13th day of September, 1962, the U. S. Dis

trict Court for the Southern District of Mississippi

entered its Permanent Injunction in this cause. (A. 56).

On the 20th day of September, 1962, on the petition

of the United States, as Amicus Curiae, the U. S. District

10

Court for the Southern District of Mississippi cited

Registrar Ellis, Dean Lewis and Chancellor Williams

of the University of Mississippi to appear on the 21st

day of September, 1962 in Meridian, Mississippi to show

cause why they should not he found in civil contempt

of the court’s injunction of September 13, 1962. On

September 20, 1962, Appellant, Meredith, also moved the

District Court to enjoin the Appellees from applying

an act of the legislature of the State of Mississippi,

SB 1501, to Meredith. The hearing on this motion was

continued because the Court of Appeals set a conflicting

hearing. The Court of Appeals entered an order en

joining any action under this act on the same day (A. 19).

On the 21st day of September, 1962 at 1 :30 o ’clock

P.M. the said District Court heard the citation for con

tempt against these three college officials and found

that they were not guilty of civil or criminal contempt

of the court’s permanent injunction order. [The Court

of Appeals later came to the exact same conclusion.

(A. 45).] Neither the Appellant nor the Amicus Curiae

ever took any subsequent action concerning this matter

in the U. S. District Court for the Southern District of

Mississippi, but instead both the Appellant and the

Amicus proceeded to conduct all subsequent matters

in the Court of Appeals.

Section B-l above presents in chronological sequence

all of the sixteen orders entered by the U. S. Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit which are involved on

this petition. To save prolixity, said orders and the

petitions or motions on which they were granted are

not restated here. The Court of Appeals conducted

six original hearings in New Orleans, Louisiana in these

proceedings, as follows:

11

(a) On the 24th day of September, 1962, an en banc

hearing was held on that court’s Show Cause

Order directed to the Board of Trustees and

University officials.

(b) On the 28th day of September, 1962, the Court

heard en banc, the Show Cause Order directed

to Governor Boss B. Barnett on a citation for

civil contempt.

(c) On the 29th day of September, 1962, a division

of the Court heard the citation for civil contempt

against Lt. Governor Paul B. Johnson.

(d) On the 1st day of October, 1962 a division of the

court heard a motion to dissolve the temporary

restraining order issued September 25, 1962.

(e) On the 2nd day of October, 1962, a division of

the Court held a hearing on the contempt orders

issued against Governor Barnett and Lt. Gov

ernor Johnson.

(f) On the 12th day of October, 1962, the Court

held an en banc hearing on the motion of the

Appellant and the Amicus Curiae for a Pre

liminary Injunction and on the contempt orders

issued against Governor Barnett and Lt. Gov

ernor Johnson.

3.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

On the evening of September 13, 1962 Governor Bar

nett made a state-wide radio and television broadcast

to the citizens of the State of Mississippi. During the

course of this broadcast he published a Proclamation,

pursuant to a state legislative resolution and statute,

directing the officials vested with the authority of op

erating the colleges and universities of the State of

Mississippi to uphold the laws of the state and to oppose

12

any illegal usurpation of their powers. (Govt. Ex. No.

6, Hearing 9/28/62 p. 69).

On the 18th day of September, 1962, the United

States requested leave of court to appear as amicus

curiae in this cause. It did not make this appearance

in the U. S. District Court, whose permanent injunction

had been issued prior to the Governor’s broadcast, but

strangely, it went instead, before a division of the Court

of Appeals, then sitting in another case in Hattiesburg,

Mississippi, and, without notice, applied for leave to

intervene as an Amicus Curiae. On this motion, with

out a hearing, this division granted Amicus Curiae

status to the United States to appear both in that

Court and in the District Court.

On the 20th day of September, 1962, the legislature

of the State of Mississippi enacted Senate Bill 1501

(Govt. Ex. No. 12, Hearing 10/12/62 p. 15) making

it a misdemeanor for any person charged with a crime

involving moral turpitude to attempt to enroll in any

institution of higher learning in the State of Mississippi.

On the same day Governor Barnett, in the exercise of

the police power of the State of Mississippi, by Procla

mation, directed the Board of Trustees of Institutions

of Higher Learning to refuse admission to the University

of Mississippi to James H. Meredith (Govt. Ex. No. 7,

Hearing 9/28/62 p. 69). On the same date, and contrary

to the wishes of Governor Barnett, this Board of Trus

tees appointed the Governor as Registrar of the Uni

versity of Mississippi for the purpose of dealing with

the application of Meredith (A. 59). This date was

the first day for admission of transfer students. Mere

dith presented himself at the University for admission.

Governor Barnett refused him admission and delivered

13

to Meredith at that time a Proclamation covering such

denial (Govt. Ex. No. 8, Hearing 9/28/62 p. 69).

On the 25th day of September, 1962 Governor Barnett

directed all sheriffs and law enforcement officials of

the counties and municipalities of Mississippi to pro

ceed to do all things necessary to the end that the

peace and security of the people of the state would

be fully protected. (Govt. Ex. No. 10, Hearing 9/28/62,

p. 70). In New Orleans the Court of Appeals, on the

applications of the Amicus Curiae and Meredith, grant

ed Temporary Restraining Orders, without notice, or

hearing, enjoining the State of Mississippi, Governor

Barnett, Lt. Governor Johnson and numerous other

persons who had never been parties to this cause at

any stage of the proceedings. (A. 26, 31).

Also on the 25th day of September, the Board of

Trustees entered an order stating that Governor Bar

nett’s appointment as Registrar was revoked. Subse

quent thereto, the Governor issued and personally de

livered to James H. Meredith a Proclamation finally

denying him admission to the University of Mississippi

(Govt. Ex. No. 11, Hearing 9/28/62, p. 70). In the

evening of this day, the Court of Appeals, on the ap

plication of the Amicus Curiae, without notice or hear

ing, issued a Citation to Governor Barnett to appear

in New Orleans, Louisiana and Show Cause why he

should not be held in civil contempt. (A. 33). A copy

of the court’s Show Cause Citation was “ attempted”

to be served on September 26, 1962 but no personal or

other service was made on the Governor. The return

of the Deputy U. S. Marshall on this Citation shows

that he did not leave a copy thereof at the Governor’s

office or at his home. (Govt. Ex. No. 3, Hearing 9/28/62,

p. 23).

14

On the 26th day of September, 1962, Lt. Governor

Johnson met Meredith at the entrance to the campus

of the University in Oxford and, acting- on behalf of

Governor Barnett, denied Meredith admittance to the

University of Mississippi. (Hearing 9/29/62, p, 19).

On the 27th day of September, 1962, a Deputy U. S.

Marshal “ served” a Citation in Civil Contempt issued

to him “ by leaving a true and correct copy thereof with

Mrs. Paul B. Johnson, Jr., personally.” (Govt. Ex.

No. 3, Hearing 9/29/62, p. 10).

On Sunday, September 30, 1962, Meredith, accompani

ed by armed U. S. Marshals, entered the campus of

the University of Mississippi and, upon demand by

the United States that housing be furnished immediate

ly, he and the accompanying US marshals were assigned

to a suite of rooms in a dormitory at said institution.

Demands for the special registration of Meredith on

that Sunday were denied by the University.

On October 1, 1962, Meredith registered as a student

at the University of Mississippi, and since that date

he has been continuously enrolled as a student in said

institution and has been attending classes there.

F.

ARGUMENT

I.

THE COURT OF APPEALS SO FAR DEPART

ED FROM THE ACCEPTED, USUAL AND

STATUTORY COURSE OF JUDICIAL PRO

CEEDINGS AS TO CALL FOR AN EXERCISE

OF THIS COURT’S POWER OF SUPERVISION.

A simple recitation of the fact that in the course of

thirty days an appellate court of limited jurisdiction

15

issued sixteen original judgments and orders in Hat

tiesburg, Mississippi, New Orleans, Louisiana and At

lanta, Georgia in a case which had previously been

remanded to the District Court and that all such pro

ceedings were done after the issuance of the District

Court’s Permanent Injunction, should be sufficient

argument to carry this point without the necessity of

detailing that none of these orders were directed to

the court of original jurisdiction whose actions this

appellate court is constituted to review. The majority

of these orders were directed to persons who had never

been parties to the action in the District Court. At least

such recitation will indicate that no precedent exists

for such a procedure. We pray the court’s consideration

of the following analysis.

a.

The United States, as Amicus Curiae, Improperly

Assumed Control and Direction of Private Litiga

tion.

The case of Meredith v. Fair was an action by an

individual citizen asserting rights under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

The United States applied to the Court of Appeals

for the designation of the United States as Amicus

Curiae, but, under this aegis, instead of befriending

the court it dominated and controlled all subsequent pro

ceedings which are here sought to be reviewed.

An allegation was made in the application to the

court that such designation was necessary because the

interest of the United States could not be adequately

represented by the “ Plaintiff ” in the proceeding. Not

only was no evidence introduced to support this alle

gation but rather the contrary clearly appears from

16

the record which show that the “ Plaintiff” secured sub

stantially duplicating orders in the Court of Appeals

at most of the stages in this proceeding.

Just why the Department of Justice assumed this

role and why it chose to conduct its actions in the

appellate court and not in the court having jurisdiction

of the cause is not readily discernible from any study

of legal precedents. What is abundantly clear is that

the allowance of this course of judicial proceeding by

the Court of Appeals is so unusual and unaccepted that

it should invoke the powers of supervision of this Hon

orable Supreme Court.

b.

The Court of Appeals Cannot Issue Personal Writs

Across State Lines Returnable Outside of the State

Where Service Thereof Was Made.

Historically and traditionally, personal summonses to

parties-defendant in courts of the Federal Judiciary

have been limited by the territorial boundaries of the

sovereign states which formed and composed the Federal

Union, in the absence of a specific statute of the United

States to the contrary. Rule 4 (f), Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure. (A. 8). Yet, in this instance, the

Court of Appeals issued summonses which did not

comply with its own Rule 9 or with Rule 59(1) of this

Supreme Court, and caused such summonses to be served

by Deputy Marshals who were not acting as the marshals

of that court (Hearing 10/12/62 p. 19). Title 28 USC,

§547(a). (A. 3). This process allegedly served in Mis

sissippi was returnable in the State of Louisiana.

It is interesting to note that this court has not yet

seen fit to adopt the provision of the 1955 Report of

17

the Advisory Committee, which proposed a liberalization

of Buie 4(f) to permit service outside of the state but

within 100 miles of the place where the suit is to be

tried. Report of the Advisory Committee, Yol. 3-A,

Pages 542-544. Neither attempted service was within

a 100 mile radius of New Orleans. The Fifth Circuit

has ruled that service outside of the territorial limits

of the state by a District Court is unavailing. Hanes

Supply Co. v. Valley Evaporating Co., 261 F. 2d 29. Cf.

Hess v. Pawloski 274 US 352, 71 L. Ed. 1091, 47 S. Ct.

632; Wuchter v. Pizzutti 276 US 13, 72 L. Ed. 446, 48

S. Ct. 259, and Ahrens v. Clark, 335 US 138, 92 L. Ed.

1898, 68 S. Ct. 1443.

c.

Intervention in An Appellate Court as a Plaintiff

to Assert a Permissive and Independent Claim

Against New Defendants is Unprecedented.

The United States made a drastic change in its posi

tion in these proceedings when the question of the bar

of the Eleventh Amendment was raised. Despite its

designation as Amicus Curiae, the United States now

apparently wishes to assert that it became a new party-

plaintiff in the case of Meredith v. Fair in the Court of

Appeals. Its amicus curiae pleadings assert a general

right on its own behalf to preserve the administration

of justice and the integrity of the judicial processes

of the United States courts as distinguished from an

amicus curiae duty to aid the court in this cause. Such

a general right, if it did exist, would be a separate and

distinct claim from any claim asserted by the original

plaintiff, Meredith, cf. In Re Debs, 158 U. S. 564, 39

L. Ed. 1092, 15 S. Ct. 900.

18

In dealing with the subject of intervention in courts

of first instance, this court has prescribed two distinct

conditions of intervention:

(1) Intervention as of right, under Buie 24 (a) of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, (A. 8) must

involve a situation where the applicant is or may be

bound by the judgment in the action in which he in

tervenes. Barron & Holtzoff, Federal Practice and Pro

cedure, §597.

(2) Permissive intervention under Rule 24(b) is ap

plicable, where a statute of the United States confers

a conditional right to intervene or, the claim asserted

involves a common question of law or fact. None of

these conditions were here present if the United States

is asserting a general right in its own behalf. It should

also be of interest to note that this court requires any

intervention to be accomplished only after notice served

on all parties affected thereby. Rule 24(c). cf. 28 USC

2403.

Our research has failed to disclose a case in which

any Federal Court has ever permitted a party to in

tervene as a plaintiff at the appellate level. To the

contrary are the cases of Smith v. American Asiatic

Underwriters, 134 F. 2d 233, from the 9th Circuit, Wen-

borne-Karpen Drier Co. v. Cutler Dry Kiln Co., 292 F.

861, from the 2nd Circuit, and Holland v. Board of Pub

lic Instruction, 258 F. 2d 730, from the 5th Circuit.

d.

The Court of Appeals Usurped the Jurisdiction

and Functions of the District Court in These Pro

ceedings.

Title 28, USC, §1291, grants to the Court of Appeals

the only possible basis for jurisdiction of any of these

actions, and this statute (A. 4) specifies that this jur-

19

isdiction is entirely appellate. The appeal in Meredith

v. Fair was long ago heard and decided by the Court

of Appeals. Its mandate had been returned to the Dis

trict Court and, prior to the institution of any of the

proceedings here complained of, that court had entered

its Permanent Injunction in full conformity with the

mandate of the Court of Appeals. Never at any time

was it shown that the District Court was, because of

the condition of its docket or for any other reason, un

able to promptly take action to enforce the Court of

Appeals mandates or its own orders issued pursuant

thereto. It was not shown and, indeed, it could not

be shown that the District Court was corrupt or un

willing to obey the mandates of the Court of Appeals.

The District Court was simply ignored, yet it was the

only court possessed with jurisdiction of the cause. In

deed the District Court is the only court in the Federal

Jurisdiction System, other than this Honorable Supreme

Court, which is possessed of any constitutional or statu

tory jurisdiction of a suit by the United States against

a sovereign, cf. 28 USC, §1345, 1391(b) & 1404(a) (A .5 );

U. S. Constitution, Article III, §2, Clause 2. (A. 1).

Every one of the judgments and orders entered by the

Court of Appeals, if valid at all, should have been en

tered, in the accepted, usual and statutory course of

judicial proceedings, only by the District Court which

was possessed of original jurisdiction.

We respectfully direct the court’s attention to the

remarks of the concurring Court of Appeals Judges

that the handling of this matter by the District Court

after their order of October 19, 1962 “ should tend

to restore normalcy in Mississippi and wrould comport

with good judicial administration under the circum

20

stances” . (A. 54). cf. Phillips v. U. S., 312 U. S. 246,

85 L. Ed. 800, 61 S. Ct. 480.

The District Court was possessed of all powers which

were claimed by the Court of Appeals. It had venue of

the original action. In addition, its rules contemplate

the conduct of fact finding litigation. On the contrary

we call to the Court’s attention that under the doctrine

of inclusio unius est exclusio alterius the Court of Ap

peals has not adopted and has rejected the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure (with certain exceptions, none of

which are pertinent here). Rules of the Fifth Circuit

Rule 10, cf. Rule 8.

The Legislature of the State of Mississippi was con

vened in special session during most of these proceed

ings, which involved both the Governor and the Lt.

Governor, who is the President of the Senate. Yet, at

many stages during these new proceedings which were

originated against them in the appellate court, process

was issued to them, returnable hundreds of miles away

in another state. The annals of jurisprudence of this

country disclose no precedent, let alone an accepted and

usual course for the District Court proceedings which

were here instituted and conducted in a court possessing

only limited appellate jurisdiction. Indeed, the absence

of any appropriate rules in the Court of Appeals gov

erning these proceedings should be most indicative of

the complete novelty involved here. As the best argu

ment indicating the vital importance of “ playing by

the rules” we respectfully direct the Court’s attention

to the following excerpts from the dissenting opinion in

the case of Boman v. Birmingham Transit Company 292

F. 2d 4.

“ <# * * Since we must rest our decision on the

Constitution alone, we must set aside predilections on

21

social policy and adhere to the settled rules which

restrict the exercise of our power to judicial review

•—remembering that the only restraint upon this power

is our own sense of self-restraint’ .1

‘ ‘ The author2 then illustrates his point by supposing

that two baseball teams were tied in the last inning

of the World Series and the umpire is morally con

vinced that the Yankees ought to win. The Yankee

runner is tagged with the ball forty-five feet from

the home plate, and the umpire, acting on his under

standing of the precepts of natural law, rules that the

runner is safe at home. Those who bet on the Dodgers

are then confronted with the problem of whether the

moral law requires them to pay their bets. He closes

with this question, which he answers himself:

“ ‘ Does the decision of the umpire prevail over

the rules of the game? One of the rules of the game

is that both teams shall obey the decision of the um

pire; and the umpire has promised to stick to the

rule book.’ ”

Eegardless of how certain the Court of Appeals may

have been that they alone had the correct moral or

social concept of how the litigation then properly cogniz

able only by the District Court or this Court should be

decided, the rules which have governed legal procedures

since the establishment of the Federal Judicial System,

the rules which set them above District Courts, do not

unshackle them from the necessity of exercising their

review powers only according to the rules.

xThis quotation is from the dissent of Chief Justice Vinson in

Barrows v. Jackson, 1953, 346 U. S. 249, 269, 73 S. Ct. 1031, 97

L. Ed. 1586.”

2Ralph T. Catterall of the State Corporation Commission of Vir

ginia, Vol. 42, American Bar Journal No. 9, September, 1956, p. 833.

22

II.

THE ISSUANCE OF THE TEMPORARY RE

STRAINING ORDERS AND THE PRELIMI

NARY INJUNCTION ORDER AGAINST THE

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI VIOLATED THE

ELEVENTH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTI

TUTION OF THE UNITED STATES AND WAS

CONTRARY TO THE HOLDING OF THIS

COURT IN THE CASE OF MISSOURI V. FISKE,

290 U. S. 18.

James H. Meredith originally brought suit against

the persons who composed the Board of Trustees of

Institutions of Higher Learning. This was not brought

or maintained as a suit against the State of Mississippi.

Under the strict provisions of the Eleventh Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States (A. 2), as

well as under the provisions of Title 42, USC, §1983,

(A. 7) (the basis for the asserted jurisdiction in the

original action) it could not have been entertained as

a suit directly or indirectly against the State of Mis

sissippi. By its plain, direct terms the Eleventh Amend

ment expressly prohibits the judicial power of the courts

of the United States from being extended to suits by

individuals against sovereign states. Section 1983 of

Title 42 only permits an action against a “ person” .

This does not include a state or governmental unit.

Monroe v. Pape 365 US 167, 5 L. Ed. 2d 492, 81 S. Ct. 473,

Egan v. Aurora 367 US 514, 5 L. Ed. 2d 741, 81 S. Ct. 684.

Stone v. Interstate Natural Gas Co. (CA 5) 103 F. 2d

544, affirmed 308 U. S. 522, 84 L. Ed. 442, 60 S. Ct. 292,

taught that even a suit against the Attorney General

of the State was not necessarily a suit against the state

itself and that litigation involving state officials did

not per se bind the State of Mississippi. In the case of

23

Louisiana Land & Exploration Co. v. State Mineral

Board (CA 5) 229 F. 2d 5, the Court of Appeals held that

the determination as to whether or not a particular suit

against a state agency amounted to a suit against the

state was to be decided by the law of the state and that

if the state courts decided that a suit against a state

agency was directed to it in its official capacity and

not to the members of the agency individually, the

Eleventh Amendment would prohibit the action. No

state court decision has ever been rendered as to whether

a suit against the state officials sued at any stage of the

proceedings here is in fact a constitutionally prohibited

suit.

In the case of Fitts v. McGhee, 172 U. S. 516, 43 L. Ed.

535, 19 8. Ct. 269 this court stated:

“ ‘ The very object and purpose of the eleventh

amendment were to prevent the indignity of subject

ing a state to the coercive process of judicial tribunals

at the instance of private parties. It was thought

to be neither becoming nor convenient that the several

states of the Union, invested with that large residuum

of sovereignty which had not been delegated to the

United States, should be summoned as defendants

to answer the complaints of private persons, whether

citizens of other states or aliens, or that the course

of their public policy and the administration of their

public affairs should be subject to, and controlled

by, the mandates of judicial tribunals without their

consent, and in favor of individual interests. To se

cure the manifest purposes of the constitutional ex

emption guaranteed by the eleventh amendment re

quires that it should be interpreted, not literally and

too narrowly, but fairly, and with such breadth and

largeness as effectually to accomplish the substance

24

of its purpose. In this spirit it must be held to cover,

not only suits brought against a state by name, but

those also against its officers, agents, and represen

tatives, where the state, though not named as such,

is, nevertheless, the only real party against which

alone in fact the relief is asked, and against which

the judgment or decree effectively operates * *

i C # * #

“ If these principles be applied in the present case,

there is no escape from the conclusion that, although

the state of Alabama was dismissed as a party de

fendant, this suit against its officers is really one

against the state. As a state can act only by its of

ficers, an order restraining those officers from taking

any steps, by means of judicial proceedings, in exe

cution of the statute of February 9, 1895, is one which

restrains the state itself, and the suit is consequently

as much against the state as if the state were named

as a party defendant on the record.”

Although the Eleventh Amendment does not by its

terms bar a citizen from suing his own state, this Hon

orable Court has squarely held that such a suit cannot

be maintained, in the absence of the consent of the

state, by one of its own citizens. Hans v. Louisiana, 134

U. S. 1, 33 L. Ed. 842, 10 S. Ct. 504.

This entire proceeding is contrary to the holding of

this court in Missouri v. Fiske, 290 U. S. 18, 78 L. Ed.

145, 54 S. Ct. 18. In that case an ancillary action was

started in a U. S. District Court. The State of Missouri

was made a party and an injunction was sought against

the state to stop the prosecution of a citation in a state

court, which prosecution, it was found, would interfere

with the in rem subject matter of the Federal Court

action. This court stated:

25

“ * * * The Eleventh Amendment is an explicit

limitation of the judicial power of the United States.

* * * However important that power, it cannot extend

into the forbidden sphere.1 Considerations of conveni

ence open no avenue of escape from the restriction.

The ‘ entire judicial power granted by the Constitution

does not embrace authority to entertain a suit brought

by private parties against a State without consent

given.’ Re New York, 256 U. S. 490, 497 * # *. Such

a suit cannot be entertained upon the ground that

the controversy arises under the Constitution or laws

of the United States. * * *

“ The ancillary and supplemental bill is brought

by the respondents directly against the State of Mis

souri. It is not a proceeding within the principle

that suit may be brought against state officers to

restrain an attempt to enforce an unconstitutional en

actment # * *. Here, respondents are proceeding

against the State itself to prevent the exercise of its

authority to maintain a suit in its oivn court.

1‘ The proceeding by ancillary and supplemental bill

to restrain the State from this exercise of authority

is unquestionably a ‘ suit’. * * * Expressly applying

to suits in equity as well as at law, the Amendment

necessarily embraces demands for the enforcement of

equitable rights and the prosecution of equitable reme

dies when these are asserted and prosecuted by an

individual against a state. This conception of the

Amendment has had abundant illustration. * # #

(Citations).

“ * * * This is not less a suit against the State be

cause the bill is ancillary and supplemental. The State

XA11 emphasis in quotations is supplied.

26

had not been a party to the litigation which resulted

in the decree upon which respondents rely. The State

has not come into the suit for the purpose of litigating

the rights asserted. Respondents are attempting to

subject the State, without its consent, to the court’s

process.

“ The question, then, is whether the purpose to pro

tect the jurisdiction of the Federal Court, and to main

tain its decree against the proceeding of the State

in the State Court, removes the suit from the appli

cation of the Eleventh Amendment. The exercise of

the judicial poiver cannot be protected by judicial

action which the Constitution specifically provides is

beyond the judicial power. Thus, when it appears that

a State is an indispensable party to enable a Federal

court to grant relief sought by private parties, and

the State has not consented to be sued, the court will

refuse to take jurisdiction. * * * And if a State, unless

it consents, cannot be brought into a suit by original

bill, to enable a Federal court to acquire jurisdiction,

no basis appears for the contention that a State in

the absence of consent may be sued by means of an

ancillary and supplemental bill in order to enforce a

decree.

“ The fact that a suit in a federal court is in rem,

or quasi in rem, furnishes no ground for the issue of

process against a non-consenting state. * * *.

L < # * *

“ * # * The contention that the question of owner

ship of the shares has been finally determined by

the Federal Court affords no ground for the con

clusion that the Federal Court may entertain a suit

against the State, without its consent, to prevent the

27

State from seeking to litigate that question in the

State Court.”

“ The decree of the Circuit Court of Appeals is re

versed and the cause is remanded to the District Court

with directions to dismiss the ancillary and supple

mental bill.”

The fact that this present assertion of ancillary jur

isdiction is made by a court of limited appellate juris

diction, as well as the fact that such relief is being

sought by a newcomer to the litigation, designated as

Amicus Curiae, cannot operate separately or together

to create a jurisdictional situation whereby the appel

lant, Meredith, would be enabled to do that which the

Eleventh Amendment forbids, to-wit: sue the State of

Mississippi without its consent.

Thus, in summary analysis, we find the Court of

Appeals granting an Amicus Curiae a Writ of Injunction

which the Court of first instance could not have entered

as either original or ancillary relief, on the basis that

what the Amicus really sought, by its motion to be de

signated as Amicus, was not the right to advise the

court as to the merits of the controversy but to assert

a new distinct, separate and independent cause of action

based upon new facts and requiring the presence, as

a party, of a sovereign state. Such a state of facts

cannot be made to accord with the express prohibition

of the Eleventh Amendment under the holding of this

court in Missouri v. Fiske, supra, or with any statutory

grant of jurisdiction by act of Congress.

Neither the State of Mississippi nor any of the other

new party ‘ ‘ defendants ’ ’ in the appellate court have had

their day in court. As to such new ‘ ‘ defendants ’ ’ the pro

ceedings were coram non judice, and they are in no way

bound thereby.

28

III.

NEITHER THE APPELLANT NOR THE

UNITED STATES MET THE BURDEN OP

PROVING THE FACTS ESSENTIAL TO ES

TABLISH SUCH JURISDICTION AS THEY

CLAIMED WAS VESTED IN THE COURT OP

APPEALS.

By its own name, “ Ancillary Jurisdiction” indicates

it must depend upon the prior presence of a case or

controversy before a court which asserts such jurisdic

tion. At the time that these “ ancillary” proceedings

took place in the Court of Appeals, there was no such

jurisdictional prior case then in that court to which ap

pendant or “ ancillary” jurisdiction could attach.

The Court of Appeals is possessed of appellate re

view jurisdiction only. It heard an appeal on the merits

from the District Court and on the basis of that appeal,

it reached a decision that the case should be reversed

and remanded with directions. This decision was im

plemented by the court’s mandate; and after the man

date was sent down the District Court fully complied

with the directions of the appellate court. If there is

an end to appellate review proceedings, this end was

fully reached before any “ ancillary” proceedings were

commenced.

The only possibility which existed for the assertion

of any residual jurisdiction was an injunction which, by

its own terms, was to last only “ pending such time as

the District Court has issued and enforced the orders

herein required and until such time as there has been

a full and actual compliance in good faith with each

and all of said orders by the actual admission of plain

tiff-appellant to, and the continued attendance thereat,

29

at the University, on the same basis as other students

who attend the University.”

This court has held that the burden of proving all

jurisdictional facts rests upon the party asserting that

the court has jurisdiction. McNutt v. General Motors

Acceptance Corp., 298 U. S. 178, 56 S. Ct. 780, 80 L. Ed.

1135. In fact, since more than a century ago in Turner

v. Bank of North America, 4 Dali. 8, 1 L. Ed. 718, this

court has adhered to the doctrine that courts of the

United States were presumed to be without jurisdiction

unless the contrary affirmatively appears from the rec

ord. No proof was offered to show that the conditions

upon which the court’s injunction was to remain out

standing had not, in fact, completely transpired.

Proof that parties other than those addressed in the

injunction might be involved in some questionable ac

tivities cannot suffice. An injunction cannot be issued

which is so broad as to make punishable the conduct

of persons who act independently of the parties to the

litigation and whose rights have not been adjudged ac

cording to law. Regal Knitwear Co. v. National Labor

Relations Board, 324 U. S. 9, 89 L. Ed. 661, 65 S. Ct. 478

Chase National Bank v. Norwalk, 291 U. S. 431, 78 L. Ed.

894, 54 S. Ct. 475; Alemite Mfg. Corp. v. Staff, 42 F. 2d

832, Scott v. Donald 165 U. S. 107, 41 L. Ed. 648, 17 S. Ct.

262.

It is patent that a court which has no jurisdiction

at all cannot exercise' “ ancillary” jurisdiction. The

record here makes it equally clear that the parties who

had the burden of proving jurisdiction failed to prove

that any conditions existed which would give life to

the only order which could vest a modicum of juris

diction in the Court of Appeals.

30

IV.

THE ACTIONS OF THE AMICUS CURIAE

CONSTITUTE AN ASSERTION BY IT OF IN

DIVIDUAL AND PRIVATE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT RIGHTS CONTRARY TO THE

DECISIONS OF THIS COURT IN SHELLEY v.

KRAEMER, 334 U. S. 1, AND HAGUE v. CIO,

307 U. S. 496.

No case has ever held that the Federal Government

acquired any rights under the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution. In the case of Shelley v. Kraemer,

344 U. S. 1, 92 L. Ed. 1161, 68 S. Ct. 836, this court held

that the rights created by the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment are

guaranteed to the individual, and the rights established

are personal rights.

In Hague v. CIO, 307 U. S. 496, 83 L. Ed. 1423, 59 S. Ct.

954 this court stated:

“ Natural persons, and they alone, are entitled to

the privileges and immunities which Section 1 of the

14th Amendment secures for citizens of the United

States.” cf. U. S. v. Alabama, 171 F. Supp. 720, 729,

(CA 5) 267 F. 2d 808.

Despite these authorities, an examination of the record

discloses that the United States, under its designation

of Amicus Curiae, not only has brought civil contempt

proceedings (which exist solely for the benefit of the

complainant and not for any public purpose, see XI,

infra) but also has sought and received an injunction

and restraining order—all as a part of a private law

suit by an individual person asserting Fourteenth

Amendment rights against other individual citizens. In

deed, the entire control and direction of this litigation

31

has been assumed by the amicus curiae to assert rights

which it has no power to assert, in a forum lacking

jurisdiction.

Y.

THE ACTIONS OF THE COURT OF APPEALS

IN CONDUCTING ENFORCEMENT PROCEED

INGS CONFLICTED WITH THE HOLDINGS OF

THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT IN THE CASES OF

DOWAGIAC MFC. CO. v. MINNESOTA-MOLINE

PLOW CO., 124 F. 735, and MEREDITH v. JOHN

DEERE PLOW CO., 244 F. 2d 9.

The enforcement of a final judgment or decree after

an appeal has been remanded to the court of original

jurisdiction is a function of that court. The proper

function of a Court of Appeals is to provide a calm,

deliberate and dispassionate forum for reviewing the

legality of that done in a trial court where decisions

are frequently made on the spur of the moment and

in the sometimes heat of trial proceedings.

The “ All Writs Statute” , 28 USC 1651, is not a catch-

all which creates any new type of appellate review

power. It only permits the issuance of writs by a Court

of Appeals in exceptional cases where such writs are

necessary to aid existing appellate jurisdiction. U. S.

v. Mayer, 235 U. S. 55, 59 L. Ed. 129, 35 S. Ct. 16; 36

C. J. S. 784; cf. Ex Parte Republic of Peru, 318 U. S. 578,

87 L. Ed. 1014, 63 S. Ct. 793. When an appeal is no

longer pending before a Court of Appeals, the right

to issue such writs is at an end. In the case of Omaha

Elictric Light & Power Co. v. Omaha, 216 F. 848, 855,

the Eighth Circuit stated:

‘ ‘ The jurisdiction of an appellate court differs radi

cally from that of a trial court. It exists solely for

32

the purpose of review. As soon as that is finished the

suit is remitted to the trial court.”

To the same effect are Wooten v. Botnar (CA 6) 266

F. 2d 27, and Mutual Life Insurance Co. of New York

v. Holly (CA 7), 135 F. 2d 675.

The enforcement of a final decree issued by a District

Court pursuant to the mandate of an appellate court is

subject to supervision and direction by Writ of Man

damus to that court or by way of a new appeal. Sibbald

v. U. 8., 37 U. S. 488, 12 Pet. 488, 9 L. Ed. 1167; City

National Bank v. Hunter, 152 U. S. 512, 38 L. Ed. 534,

14 S. Ct. 675; cf. U. 8. v. E. I. Du Pont de Nemours, 366

U. S. 316, 6 L. Ed. 2d 318, 81 S. Ct. 1243.

In the case of Ohio Oil Company v. Thompson, 120

F. 2d 831, the Eighth Circuit pointed out:

“ It is for the district court to which the mandate

(of the Supreme Court) is directed, to construe and

execute such mandate; and if that court (1) miscon

strues or (2) refuses to enforce it or (3) attempts

‘ to vary it ’, or (4) ‘ to intermeddle with it ’, it is for

the Supreme Court alone to construe and enforce its

own mandate.”

No one of these four conditions are present here.

The mandate of the Court of Appeals to the District

Court directed the entry of an injunction of broader

scope than that prayed for in the complaint. The in

junction order of the District Court clearly complies

with the directions of the mandate, a fact which has

never been questioned. The District Court has never re

fused to enforce the mandate of the Court of Appeals

or its own injunction, nor has it attempted to vary it

or intermeddle with it. The District Court in this case

33

continues to retain the actual and proper powers of

a District Court.

The proceedings here are directly contrary to the

holdings of the Eighth Circuit. In the case of Dowagiac

Mfg. Co. v. Minnesota-Moline Plow Co., 124 F. 735, the

opinion of the court, in pertinent part was as follows:

“ An examination of the affidavits discloses the

fact that the contempt charged in this case occurred

subsequent to the filing of the mandate of this court

in the United States Circuit Court. The proposition

to which Mr. Howard has addressed himself, to the

effect that every party in a proceeding is bound to

take notice of the order of the court, and obey it,

is undoubtedly sound; and, if there had been a vio

lation of the injunction which was practically ordered

by this court during the time antecedent to the re

mission of the mandate, the court would proceed to

punish for contempt, if it thought proper to do so.

But when the mandate of this Court was remitted to

the Circuit Court, the decree of that court was, in

effect, modified, as declared by the opinion of this

court; or, if not modified simply by the filing of

that mandate, it was in the power of that court, upon

motion of the successful party, to so change its decree

that it would read in accordance with the opinion

then handed to it by this court. I f that application

has not been made, it may still be made; and if there

has been a violation of that decree since the mandate

was remitted, we are unanimously of the opinion that

the jurisdiction to punish for that violation is not in

this court, but in the Circuit Court. For this reason,

the demurrer will be sustained, and the petition dis

missed.”

34

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit in 1957, in the case of Meredith v. John Deere

Plow Co., 244 F. 2d 9, 10, cert. den. 355 U. S. 831, 2 L.

Ed. 2d 43, 78 S. Ct. 44, stated:

“ In an effort to put an end to appellant’s repeti

tive suits against it on the alleged contract, appellee

has moved for leave to file in this Court a petition

for a writ of injunction. No injunctive relief was

sought by way of counterclaim in the District Court,

nor has appellee otherwise undertaken to obtain from

that Court any such protection. No controlling reason

is apparent why, as against the normal prerogative

and function of the District Court, we should he asked

to entertain such a petition in original jurisdiction.

“ In addition, the elements of hearing that might

be involved in relation to the issuing of a writ, and

the incidents of enforcement that could become neces

sary from any granting of it are matters which a

single-judge court manifestly would be in a position

to deal with, from the standpoint of both parties,

more routinely, expeditiously, conveniently and eco

nomically than we.”

We respectfully submit that the appellate court’s

functions here were not only improper and a departure

from accepted and usual practice, but also created a

conflict between the circuits, as well as a conflict with

prior rulings of this court.

VI.

THE SHOW CAUSE CITATIONS ISSUED TO

GOVERNOR BARNETT AND LT. GOVERNOR

JOHNSON WHICH REQUIRED THEM TO AP

PEAR OUTSIDE OF THE STATE WITHIN

LESS THAN FORTY-EIGHT HOURS FROM

35

THE INSTANT OF ATTEMPTED SERVICE OF

SUCH CITATIONS DID NOT ACCORD CON

STITUTIONAL AND PROCEDURAL DUE

PROCESS TO THESE PARTIES.

The returns of the officers showing attempts made

to serve the citations in civil contempt against Governor

Barnett and Lt. Governor Johnson show that such “ at

tempts” were made less than forty-eight hours prior

to the return time of these citations (Govt. Ex. No. 3 &

Appellant’s Ex. No. 2, Hearing 9/28/62, p. 22, 57; Govt.

Ex. No. 3, Hearing 9/29/62). The citations themselves

show that they were returnable in New Orleans, Lou

isiana. The returns do not show personal service on

either respondent; but, assuming arguendo that they

had received personal service, the shortness of the time

interval would have constituted a lack of due process.

Roller v. Holly, 176 U. S. 398, 44 L. Ed. 520, 20 S. Ct. 410.

VII.

THE JUDICIAL BRANCH OF THE FEDERAL

GOVERNMENT CANNOT MANDATORILY EN

JOIN THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OF A STATE

TO PERFORM FUTURE DISCRETIONARY

ACTS.

The acts of Governor Barnett were all done and per

formed in his official capacity as the Chief Executive

Officer of the State of Mississippi, charged with the

enforcement of its laws. Mississippi Constitution of

1890, Article V, §§116, 119 and 123. (A. 9). Indeed,

the Temporary Restraining Order and the Injunction

issued against him by the Court of Appeals require

nothing at the hands of Ross R. Barnett, an individual

person. The prohibitions contained in these injunctions

are not personal but official, and are directed against

36

him as the Governor of the State. Assuming arguendo

that the Constitution of the United States does not

prohibit the issuance of such a prohibitory injunction

and restraining order, properly framed, the Court must