J. Greenberg's Policy Statement

Press Release

October 8, 1965

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 3. J. Greenberg's Policy Statement, 1965. bc61084d-b692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ec20e3f5-5a2e-4020-b1d0-dec66c1d38a3/j-greenbergs-policy-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

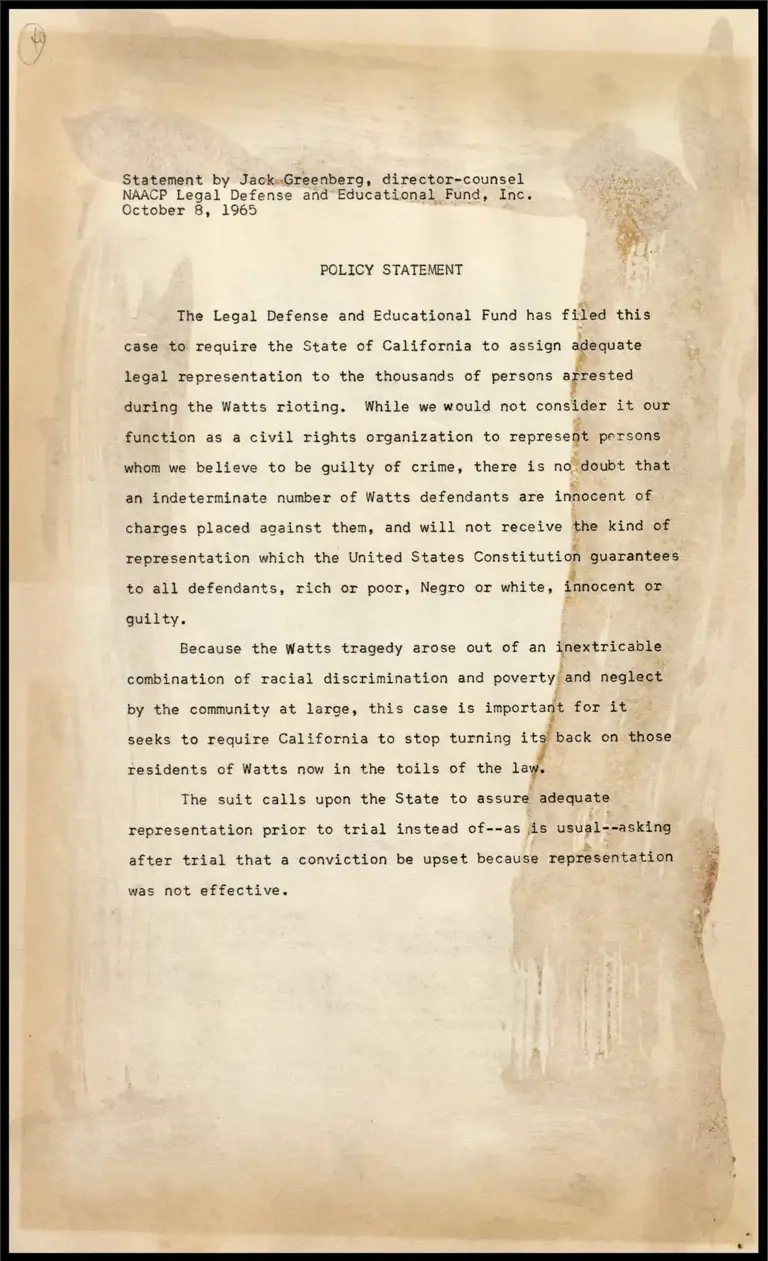

Statement by Jack»Greenberg, director-counsel

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

October 8, 1965

Ly

POLICY STATEMENT

The Legal Defense and Educational Fund has filed this

case to require the State of California to assign adequate

legal representation to the thousands of persons arrested

during the Watts rioting. While we would not consties Tt eux

function as a civil rights organization to represent persons

whom we believe to be guilty of crime, there is no doubt that

an indeterminate number of Watts defendants are innocent of

charges placed against them, and will not receive the kind of

representation which the United States Constitution guarantees

to all defendants, rich or poor, Negro or white, innocent or

guilty.

Because the Watts tragedy arose out of an inextricable

combination of racial discrimination and poverty, and neglect

by the community at large, this case is importagt for it

seeks to require California to stop turning its back on those

residents of Watts now in the toils of the law.

The suit calls upon the State to assure adequate

representation prior to trial instead of--as jis Papi ser

after trial that a conviction be upset because representation

was not effective.

ait

a

ns