Plaintiffs' Second Memorandum in Support of Standing and Class Action

Public Court Documents

February 17, 1971

11 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Second Memorandum in Support of Standing and Class Action, 1971. c1c9664f-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ec3ae6c8-f4ce-4cbc-8118-9f1a1ca858b1/plaintiffs-second-memorandum-in-support-of-standing-and-class-action. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

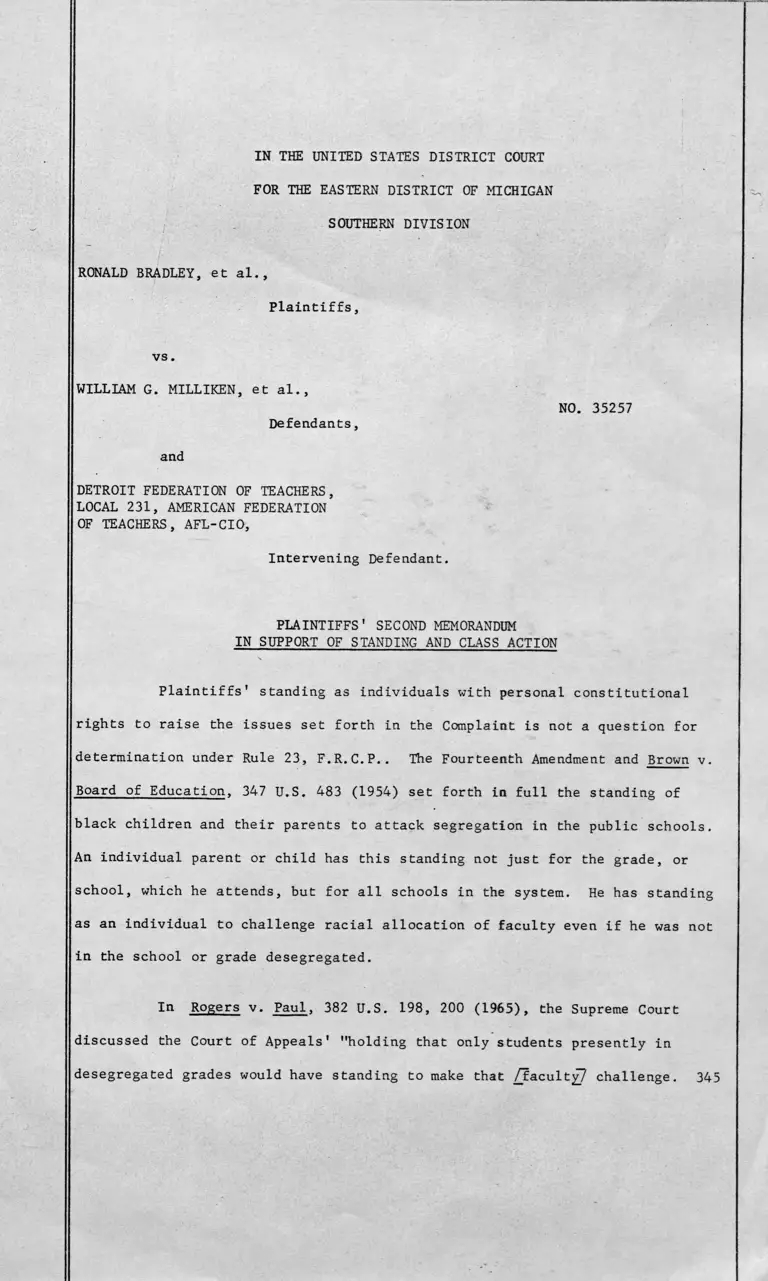

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v s .

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants,

and

NO. 35257

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Intervening Defendant.

PLAINTIFFS’ SECOND MEMORANDUM

IN SUPPORT OF STANDING AND CLASS ACTION

Plaintiffs' standing as individuals with personal constitutional

rights to raise the issues set forth in the Complaint is not a question for

determination under Rule 23, F.R.C.P.. The Fourteenth Amendment and Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) set forth in full the standing of

black children and their parents to attack segregation in the public schools.

An individual parent or child has this standing not just for the grade, or

school, which he attends, but for all schools in the system. He has standing

as an individual to challenge racial allocation of faculty even if he was not

in the school or grade desegregated.

In Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198, 200 (1965), the Supreme Court

discussed the Court of Appeals' "holding that only students presently in

desegregated grades would have standing to make that /faculty? challenge. 345

F.2d 117, 125." The Supreme Court rejected this view. "We do not agree and

remand for a prompt evidentiary hearing on this issue." It elaborated as

follows:

Two theories would give students not yet in

desegregated grades sufficient interest to

challenge racial allocation of faculty: (1)

that racial allocation of faculty denies them

equality of educational opportunity without

regard to segregation of pupils; and (2) that

it renders inadequate an otherwise constitutional

pupil desegregation plan soon to be applied to

their grades.

See also, Bradley v. School Bd. of City of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103 (1965).

The Fourth Circuit in a recent e n banc decision, Whitley v.

Wilson City Bd. of Educ., 427 F.2d 179 (4th Cir. 1970) said:

We hold that although the plaintiffs are

assigned to an integrated school, they

nevertheless have standing to attack the

defects in the board's overall assignment

What is involved is the personal constitutional right of each

plaintiff "to attend schools which, near or far, are free of governmentally

imposed racial distinctions. . . _/Not jus_t/ the peculiar rights of specific

individuals /are/ in controversy. _/The controversy is/ directed at the

system-wide policy of racial segregation." Potts v. Flax, 313 F.2d 284,

288-89 (5th Cir. 1963).

In Brown II, 349 U.S. 294 (1955), the Court made clear that the

remedy extends beyond the assignment of any particular individual. See

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372 F.2d 836 (1966), aff1d

l/ 'In Whitley,■' white parents 'and minor children assigned. to formerly black -

schools sought the right to assert their position that while their schools were

integrated, they were being singled out while other schools in the system remai led

segregated. See also, Caldwell v. Craighead,432 F.2d 213, 217 (6th Cir. 1970)

(dictum noting that single black student and parent.had standing to attack racial

discrimination in public education throughout state).

2

on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 840

(1967). "... states j_have/ the duty of furnishing an integrated school

system, that is the duty of ’effeetuat/inj;/ a transition to a racially non-

discrlminatory school system.*" 372 F.2d at 867 (quoting from Brown II at

301; emphasis added by Wisdom, J.).

Thus for all practical purposes the relief in a school segrega

tion case extends to the entire school system. Potts v. Flax, supra; Moore's

Federal Practice 3B, App. IP 23.10-1 at 2768 (1969).

Plaintiffs' standing as individuals to obtain this relief is

without reference to Rule 23, F.R.C.P. sufficient to cover all aspects of

the public schools in the city of Detroit.

In other cases discussing class actions the courts have held that

racial segregation is by definition class discrimination. ,,Hail, v Werthan .

Bag Corp., 251 F. Supp. 184, 186 (M.D. Tenn. 1966); Oatis v. Crown-Zellerbach

Corp., 398 F.2d 496, 499 (5th Cir. 1968); Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400

F.2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968); Parham v. Southwestern Bell Tel. Co., ___F.2d____

(8th Cir. 1970); see Moore's Federal Practice 3B, App. IP 23.10-1 at 2761-62.

Thus, for all practical purposes it makes no difference whether

the Court views this action technically as a class action: the inquiry into

the factual and legal issues and any ultimate relief granted will be the same

whether this action is prosecuted by the named plaintiffs on their own behalf

of some larger group. Potts v. Flax, supra; Moore's Federal Practice 3B,

App., IP 23.10-1 at 2768. As no individual has a constitutional right to. a

public school system not operated in conformity with the Constitution, class ’

action questions are academic.

3

The Detroit Branch of the NAACP is an association incorporated

undef Michigan law with over 6,000 life members and subscribers and 7,000

regular members. Many have children in the Detroit public schools. Its

purposes are "to eliminate racial prejudice; to keep the public aware of the

adverse effects of racial discrimination; and to take all lawful action to

secure its elimination..." (Constitution of the Detroit Branch of the NAACP,

Art. I, Sect. 3). It has repeatedly attempted to persuade the defendant

Board to integrate the Detroit public school system and has often questioned

specific practices and policies which operated to segregate black and white

j

children from one another. The NAACP's raison d'etre is the elimination of

unconstitutional segregation from our society and especially securing an

equal educational opportunity for black children. The local branch was

specifically authorized by its members to insure that the Detroit Public

Schools are desegregated in accord with the Brown mandate. Hence, the

local branch's stake in this litigation is very real and its status closely

related to the claim sought to be adjudicated.

That the local branch, of. the. NAACP has standing under. the liberal'- „•

ized requirements recently set by the Supreme Court in Flast v. Cohen, 392

U.S. 83 (1968) and Association of Data Processing Service Organizations v.

Camp, 397 U.S. 150 (1970), is therefore not open to serious question. Further

more, as Mr. Justice Blackmun noted cases which challenge system/race discrim

ination "dictate a liberal evaluation of the requirement of standing." Smith

v * M * Morrilton Sch. Dept. , No. 32; 365 F.2d 770,777 (8th Cir., 1966 ).

2/ The 2nd Circuit in Norwalk, Conn, v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395 F.2d

920, 937 (1968) took a contrary and, in our view, rather wooden approach to

the issue of the standing of an association to represent a classs in an other

wise insightful opinion. The quality of the second circuit's substantive dis -

cussion of other issues.especially race discrimination and urban renewal pro

jects, should not obscure that Court's failure to articulate policy reasons

to buttress its "compelling need" test for the standing of an association. In

any event, Norwalk Core is factually distinguishable from the question of the

NAACP's standing in this case: here 'the'' substantive attack is oh a system of

public schools, an issue long fought by the local branch, not the effects of a

specific urban renewal project. Further, the NAACP's position as a spokesman

for racial equality and its very appeal to a community interested in deeds is

on the line; continued racial separation in the public schools may well have an

adverse effect on the NAACP as an entity through dimunition in its membership

and financial support. Smith v. Bd. _of Ed. Morrilton Sch. Dist. 367 F.2d 770,7f7

Finally, there is serious question whether Norwalk Core is still the view of

the Second Circuit after the more recent Supreme Court rulings on the subject.

- 4 -

/

See also, "Note: Parties Plaintiff in Civil Rights Litigation, " 68 Col. L.

Rev. 893, 921 (1968). In Smith, Justice Blackmun held that an organization of

black teachers was a proper party plaintiff - had standing - to attack racial

discrimination in a school system.

There are persuasive policy arguments to support the standing of

Othe NAACP. First, policy favors adjudciation of the issue of racial

distinctions in public programs, especially in the system of public schools.

The charge is serious, the harm, if the' allegations are true, irreparable,

and the duty for remedial court action where discrimination exists is

absolute. Second, that an association with large membership and historic

and active interest in the issues before the Court is a plaintiff insures

that the suit is not baseless and that the issues are framed in an adversary

context. Third, the presence of an association like the NAACP as a party

insures that the vital issues to be heard by the Court are not "mooted" by

the fear of reprisal, unrelated departure or "purchase" of an individual

named plaintiff. Smith v. Board of Ed. of Morrilton Sch. Dept. No. 32, 365

F2d 770, 777 (8th Cir. 1966). Fourth, equity suggests that citizens should

be able to band together to assert their common constitutional rights, as

has the membership of the Detroit Branch of the NAACP, in federal court where

the cost of litigation is beyond the resources of any one or a small group

of plaintiffs.

We do not argue that the NAACP is an indispensable party. We do

I - .

_3/ We note that consistency is the least among many policy reasons. This

Court has already accepted another association, the Detroit Federation of

Teachers, as a proper party to this litigation. See also Alston v. Norfolk

School Board, 112 F.2d 993, 997 (4th Cir. 1940); Moore's Federal Practice 3A,

17.25 at 854. We also note that the local defendants readily concede the

standing of. the NAACP in this action., "Memorandum of.Detroit Bd, of Educ.

Defendants Relating to Glass Action" act 1. • • - •

- 5-

submit that the NAACP is a proper party,^ only the more so because the

substantive issue in this case concerns the entire system of public schools

in this city: the NAACP as a party augurs well that the claims presented

will be typical and representative and thereby best sharpen the issues of

this case, a type historically resolved through the judicial process. Cf.

Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83, 95, 97 (1968).5

Plaintiffs, however, appropriately bring this action as a class

action. The Notes of the Advisory Committee to the 1966 revision of Rule 23

make clear that Section (b) (2) is intended for use in civil rights cases,

especially school segregation cases like the instant action where injunctive

relief is sought to end discrimination throughout the school system:

Illustrative are various actions in the civil-rights field

where a party is charged with discriminating unlawfully

against a class, usually one whose members are incapable of

specific enumeration. 28 U.S.C.A., F.R. Civ. P. Rules 17-33,

1970 Supplement (emphasis added.)

Cited in support of the quoted propositi'

several other school desegregation cases

ate Potts ,v. Flax,, supra, and .

We do not understand that the

4/ It is reversible error to dismiss a proper party. Bradley v. Milliken

(6th Cir. 1970), slip op. at 14-15.

— ̂ In Ass'n of Data Processing Service Organization v. Camp, 397 U.S. 150,

153 (1970), the Court stated that standing would lie if the interest sought

to be protected is "arguably within the zone of interests" protected by

! statutory or constitutional guarantees in question. That the NAACP asserts

such an interest on behalf of its membership is clear. More important, how-

| ever> Ass'n of Data Processing by example shows that an association has a

sufficient interest to sue in its own name. Accord, Citizens Ass'n of

Georgetown v. Simonson, 403 F. 2d 175 (D.C.Cir. 1968); Environmental

Defense Fund, Inc, v. Hardin, 428 F. 2d 1093, 1096-97 and Notes 12-17. (D.C.

1970). Courts have enforced uniformly the Congressional policy con

tained in aggrieved party" statutes, to grant standing to many organizations

and associations. See, e.g. International Chemical Workers Union v. Planters

Manufacturing Co., 259 F. Supp. 365 (N.D. Miss. 1966); Nashville 1-40

Steering Committee v. Ellington, 387 F.2d 179 (6th Cir. 1967) . ThT^aggrieved

; / _ party'' requirernent "is the equivalent to the requirement that - the complainant's

: interests fall within the zone of interests protected.'^ ' Environmental ' - ■

Defense Fund, Inc, v. Hardin, 428 F. 2d 1093, 1097 N. 16.

- 6 -

Detroit Board's memorandum^ questions the appropriateness of class action

in these type suits generally; rather local defendants apparently question

the (1) precise defintion of the class and (2) need for notice.

As the Advisory Committee noted a (b) (2) type class is usually

one whose members are incapable of specific enumeration. It is not necessary

that the members of the class be so clearly identified that any member can be

presently ascertained. Carpenter v. Davis, 429 F. 2d 257 (5th Cir. 1970).

Nor is it relevant that members of the class are personally satisfied with

the actions complained of in the suit; the Court need not look into the

particular circumstances of each member of the class. Moore's Federal

Practice 3B s. 23.40 at 651, 23.06-2 at 327; Norwalk Core v. Norwalk

Redevelopment Agency, 395 F. 2d 920, 937 (2d Cir. 1968). Furthermore, precise

description of the class is not required until final judgment is entered.

F.R. Civ. P. 23(c) (3). Plaintiffs, however, assert the constitutional right

•of all' parents' of sehoolage chid red (and sehoolage children) witbitv .the City .

of Detroit to a public school system operated in accord with the Constitution

(j/ Insofar as State defendants attack only the standing of the NAACP to act

as a representative of a larger class, that issue is decided by the decision

on whether the NAACP has standing at all as a party. Smith v. Morrilton Sch.

Dist. No. 32, 365 F. 2d 770, 777. If anything, however, the NAACP's

participation in the class action should be favored for its participation

insures that the claims will be typical and the. representation fair and

adequate. F.R. Civ. P. Rule 23(a) (3) - (4); "Note, Parties Plaintiff in

Civil Rights Litigation," 68 Vol. L. Rev. 893, 919-921.

7/ It is constitutionally irrelevant if some black parents and their children

Tn Detroit are satisfied with the present situation. "Separation is just as

offensive to the law when fostered by the Negro community as when the white

community encourages it." Haney v. County Board of Educ. of Sevier County,

410 F. 2d 920, 926 (8th Cir. 1969); accord, United States v. Choctaw County

Board of Educ., ____F. 2d ___, ____ (5th Cir. 1969).

- 7-

insofar as race is concerned.

Rule 23 requires that notice be given only in 23 (b) (3) type

class actions. F.R. Civ. P., Rule 23 (c) (2). The Court may require

that notice be given in 23 (b) (2), class actions under 23 (d) (2) "for

the protection of the members of the class or otherwise for the fair ®

, ■ ' ' Iconduct of the proceedings." But this is a school segregation case and

the Constitution dictates immediacy in the hearing of this cause. Alexander

and Carter. Requiring that notice be given will only delay these proceedings

not promote fairness. First, the parties and counsel now before the Court

are more than sufficient in number and interest to permit hearing and

j

determination of the issue whether the Detroit public school system

insofar as race is concerned is operated in a constitutional fashion. Second,

as a practical matter, the extensive publicity given this case by the media

in Detroit since its inception constitutes sufficient notice. Snyder v. Board

of Trustees of University of Illinois, 286 F. Supp. 927, 931 (N.D. 111. 1968).

Third, if the Court were to require personal notice, even if'the Court were ‘

to bear the expense of mailing, Knight v. Bd. of Educ. of the City of New

York, 48 F.R.D. 108, delay would be inevitable and involve the Court and

8V The better view is that' notice is not required as a matter of due

process. Moore’s Federal Practice 3B 23.55 at 1152, 23.72 at 1421-22:

"The essential requisite of due process as to absent

members of the class is not notice, but the adequacy of

representation of their interests by _/the_/ named parties.

Northern Natural Gas Co. v. Grounds, 292 F. Supp 619,

636 (N.D. 111. 1968)." But Cf.Eisen v. Carlisle and

Jacquelin, 391 F. 2d 555, 564 (2d Cir. 1968).

9/ Twice the Sixth Circuit has advanced appeals in this case for hearing

ahead of its normal practice; furthermore, the Chief Judge of the Circuit

heard a motion for injunction pending appeal four days after the filing

of the. motion. Oral argument on the second appeal made, clear .that the

Sixth Circuit wants an expeditious hearing on the ...merits.' to, proceed n o w .

- 8 -

the parties in burdensome and time consuming tasks for no reason. See10

Moore's Federal Practice 3B, 23.55 at 1153-1156. For these reasons we

urge the Court to follow the consistent practice of courts in school desegre

gation cases and not order additional notice beyond that already made in

fact by the extensive publicity given the case by the media.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, plaintiffs respectfully

submit that the Court issue an order stating that

ri»

a. individual plaintiffs have standing to bring this

action attacking the racial separation of students

and faculty -- the racial identifiability of schools --

in the Detroit public school system in all particulars;

b. the Detroit Branch of the NAACP has standing to join

in such attack; and

c. although academic, the action is properly brought

. .. .... .. . as. .a class action making such, attack. . . .... ,• . . ■

10/ In another case a District Court noted that to require personal notice

to each of the 200,000 persons there affected "would, for all pracitical

purposes spell the immediate end of this litigation." Doglow v. Anderson,

43 FRD 472, 498 (E.D. N.Y. 1968).

In contrast defendants concern for the effect of the judgment is illusory.

Any judgment in this case will bind the defendants: they will have to

operate a system found to be in conformity with the United States Constitution.

Although individual parents and children may not be bound as a technical

matter by the judgment, they have no right to attend a public school system

not in conformity with the Constitution. Hall v. St. Helena Parish School

Board, 287 F. 2d 376, 379 (5th Cir. 1961). Even if they object to such a

school system, they cannot waive their right to a "Constitutionally operated

school system: their options are to attend a unitary public school system

which is in full compliance with the Constitution of the United States in

the City of Detroit _or flee, not to have public schools in the City of Detroit

set aside for their special use. Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S.

450, 459 (1968). See also Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F. 2d 820, 827

(4th Cir. 1970. Sobeloff, J., concurring) As a practical matter, therefore,

defendants run no risk of inconsistent judgments, but may, of course, be

subject to the continuing jurisdiction of the Court in order to insure that

remedial plans ordered are 'effective'. . . ..\: V

- 9-

\

Of counsel:.

rOjtJ£ J)

PAUL R. DIMOND

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

Center for Law and

Education, Harvard

University

38 Kirkland Street

Cambridge, Massachusetts

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

Ratner, Sugarmon 6c Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

E. WINTHER McCROCM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

NATHANIEL JONES

General Counsel, N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

BRUCE MILLER and

LUCILLE WATTS, Attorneys for

Legal Redress Committee

N.A.A.C.P., Detroit Branch

3426 Cadillac Towers

Detroit, Michigan

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

- 10-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing Memorandum For

Plaintiffs has been served on counsel for the defendants, Mr. George E.

Bushnell, Jr., 2500 Detroit Bank & Trust Building, Detroit, Michigan 48226,

Mr. Theodore Sachs, 1000 Farmer, Detroit, Michigan, and Mr. Eugene

Krasicky, Assistant Attorney General, Seven Story Office Building, 525

West Ottawa Street, Lansing, Michigan 48913, by United States airmail,

postage prepaid, this 17th day of February, 1971.

fi .DfjVLPtuQ

Paul R. Dimond