Memorandum in Brief of Respondents in Reply to Petitioner's Brief in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment

Working File

February 24, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Memorandum in Brief of Respondents in Reply to Petitioner's Brief in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment, 1984. 9f2fa26b-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ec61ae92-6681-4c90-973d-3e10b7a27fbc/memorandum-in-brief-of-respondents-in-reply-to-petitioners-brief-in-support-of-motion-for-summary-judgment. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

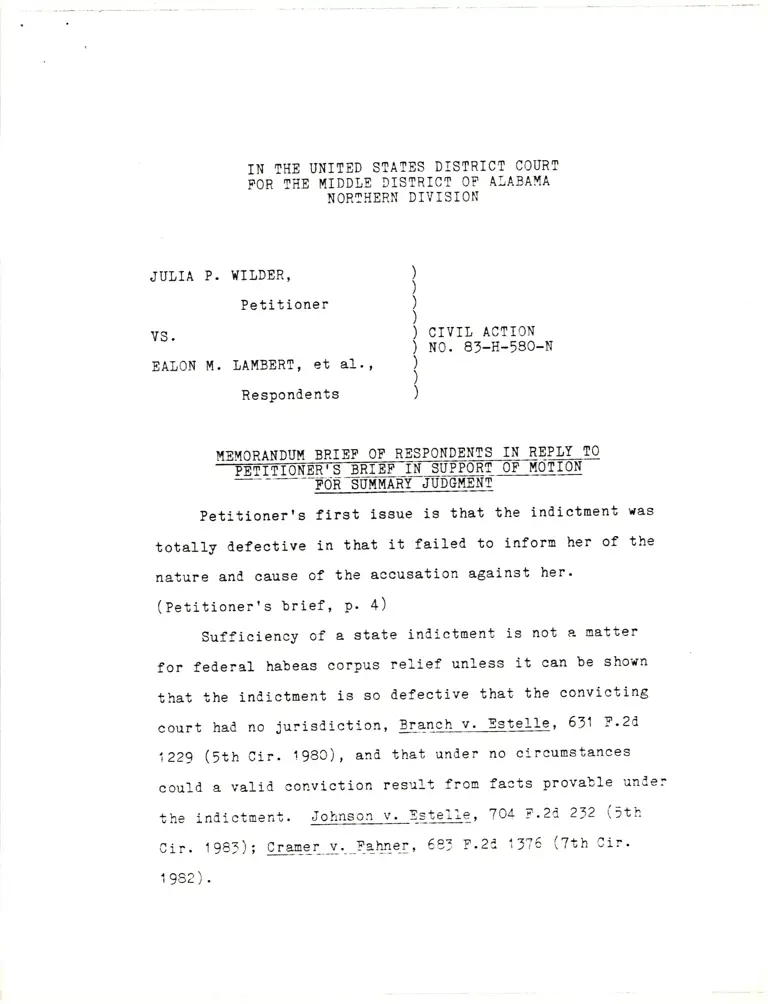

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR TEE MIDDTE DISTRICT OF ATABA}IA

NORTHERN DIVISION

JUIIA P. WII,DER,

Petit ioner

vs.

EAION M.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

CIVII ACTION

No.8r-H-580-N

IAMBERT, et &1.,

Respondents

I-!EI'1ORANDIru BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS IN REPTY IO

OF tdmr-0Rt=-:==:--roFffi

Petitionerts first issue is that the indictment vas

totally defective in that it failed to inforn her of the

nature and. cause of the accusation against her'

(Petitioner's brief, P. 4)

sufficieney of a state indietnent is not e natter

for federal habeas eorPus relief unless it can be shown

that the indictnent is so tlefective that the convieting

court had no jurisdiction, Sranch v. Estel1e, 531 F.2d

i2Zg (5tf, Cir. 198C), and that under no eireumstanees

could a valid conviction result fron facts provable unde:

the indictmeni. Jofinson y. l-s-lgllq , 7Ol F' 2'1 232 ('ti:

cir. t981); qIeP-q-Lv'--Lzlue:, 6e3 F'2d i175 (Ztn cir'

19S2).

The inctictment vas clearly sufficient to confer

jurisdiction on the state trial court to try petitioner

for a violation of Alabama Cocle 19?5, $ 17-23-1 .

Uncler subheadlng rrArt of petitlonerrs argunent, she

asserts: "The Jury Yas...authorized to fincl petitioner

guilty under $ ll-21-l if she acted in a manner'not

authorized by or...eontrary to' any stngle provtsion of

any one of a number of statutes not specifled or even

hinted at 1n the lndlctnent.n (petitioner's brief' p'

5)

Thie assertion by petitioner is absolutely

incorreet. under the trial court's charge to the Jury,

the jury was authorlzed to return guilty verdicts only

upon proof of the following tro theories as set out by

the court:

cl.2/

-G

J *tr ot*^

^ r7d, t '/

v-< t> '\<=-d

1. The State charges here that the

defendlant voted Elore than once and

that she receivecl ballots

ctestgnated for registered voters,

that she narked or hail these

ballots narked in the uaY that she

nantetl then to be narked, ancl they

rere eventuallY cast and counted

as lar for votes. Ihe charge ls

that the tlefendant voted the

ballots and not the absentee

voters in whose name theY t ere

clesignated, and that this ancunted

to her having voted. nore than

once.

l'r--r';--'6 L'*r,.1*.-j

-<4

/v1 Q,

-n

Q,4

2. The State contends that the

clefendant ParticiPateC in the

scheme to seeure absentee ballots

and to il1ega11Y or fraudentlY

cast those ballots. It ie the

Staters contention that on gotre of

bhe absentee ballots that eane

into JuIia Wilcler's Possession 'she narked the ballote@had

knowledge that the ballots Yere

narked bY someone other than the

;:*:l:";l"Iili;"":1 :::::xi,'tf;l'

she signetl or caused to be signed

/67had knowletlge that the ballots

were signed bY someone other than

the reglsterecl voter rithout that

voter's knowledge or consent.

Sueh a bal1ot voultl be i}1ega1 to

cast a ballot or ParticiPate in

the schene to cast that ba1lot

with knonletlge of these facts and

roultl faI1 within the acts

prohibitett by Section 17-21-1 .

3 L*-. eJ i..tfr-,^-x^-*D\;31 1 -r1 z)

Ihus, Petitioner's argunent that the jury vas

authorized to find her guilty under 5 ll-Zl-l if she had

acted in a manner I'not authorized by or contrary to" any

single provision of any one of a number of statutes not

specified in the ind.lctnent is rithout merit'

lhus, under the trial court's instruetions, the case

was submitted to the iury on the very charges of the

ind.ictnoent, nhich charges are characterized by the

ALabana Couri of Criminal Appeals as follows:

Count one roade the IPetitioner]

aware that she did i1lega11Y or

fraudulently vote by voting more than

once ly-iepositine more th?n qng

ballot nocratie

P-@ection of SePtember

26,1978.

Count trro infornetl the Ip"titioner]

that she did cast l1lega1 or

fraudulent absentee ballots by voting

Bore than one absentee ba1lot or bY

depositing loore than one absentee

taltot as her vote in the Democratic

Prinary Run-off Election of Septenber

26, 1 978.

Count three notified the

'1

\

.;c-L ',4.,3

<4

tj

t.;

(

t'I

e

I

'l -z

,/

u-1--

Ipetj.tioner] ttrat she did cast iIlegaI

depositing with the Piekens County

Ciicuit C1erk, absentee ballots which

yere fraudulent and that she knew to

be fraudulent.

t{iltter v. State, Ms- 0P., P. 20'

Respondents subnit the eviclence was sufficient

to fin,t petitioner guilty under either or both theories

on whieh the case was subnittetl to the iury and under any

three counts of the indictment und'er the

revier nandated by Jackson v. Yirginia, 443

,4*_

, ,aI7

,3

a-

one or al-I

standard of

u.s. 1o7 (1979).

Petitioner's entire challenge to the sufficieney of

the inclietnent must fa11 under Knewei v. EgL4, 258 U.S.

442 (19?5) (Ucting he:'e that petitioner has male some

a:.gunents about the inJictnent being insufficient because

fraudule::t con'luct is chaiged and' there being no

specifies or particulars of the fraudutrent acts, the

faets of Knewel v. Egan raake that easc particularly

appltcable here 1n that the lndictnent challenged in

Knewel alleged filtng a "false and fraudulent I lnsurance]

clainr" but dld not etate tn particular ln chat manner

the clalm was "false or fraudulent'u)'

II.

Petitionerrs second lssue is that the court's Jury

instruetions subjected petitioner to ex post facto

liabillty. (petttloner's brief, p. 24) This assertion

by petitioner is nerttless. As has been shown in

respcndentst argunents above under petltloner's first

issue, the ease ras submitted to the iury under tro

tireories of guilt unoer the indictnent, both of whlch

vere elearly charged in the indictment'

iII.

Petitioner's third iesue (pet:'tioner's brief' p'

2A), trike her first tuo, ts based Orr the faLse prenise

that the trial court'e instructions authcrlzed the iury

to eonvtet unoer S 17-21-1 nf they founo petttioner had

irrfringed irr arr$ ray' the siatutes the court maoe

reference tc in its cral charge' Agaln, as has beerr

shcwrr above, this prenise is absclutely ar^o tctally

i-necrrect.

Flna11y, it is the position of responclents that none

of the arguments made here which are based on alleged

errors in the trial eourt's oral charge can be

entertained by a habeas court because they rere nct

presented to the state trial court as provicled for and

required. by Alabarna procedural law.

Although petltioner did challenge the sufficiency of

the intllctment by a pre-tria1 notion (R. 524-125), the

grounds raised in the habeas petition here relating to

the court's orai charge Yere not presented to the trial

court, nor have they been passed on by the Alaba"ma

appellate courts.

The proper proceclure at trial woul-d have been an

objection at the end of the eourtrs oral eharge to the

jury, and that objeetion shoult!. have been that it was

error for the trial court to instruct tne jury as to the

four statutes eovered in the orai eharge on groun'1s the

statutes were not included or charged in the indictment,

on grountls that eharging the jury on these statutes

subjected petitioner to ex post faeto liability, and on

grounds the trial eourt's oral charge allowed a guilty

verd.ict on strict liability grounds.

Alaba.na law is very clear that in order to preserve

for review alleged errors in a trial eourtrs oral charge'

a defendant nust object, point out to the trial court the

a1}egeflIy erroneous portions of the charge, ancl assign

speeific grounds as to why the defendant believes there

1ras error. Brazell v. State, 421 So.Zd 123 (afa. Crlm.

App. 1 982).

Failure to nale suffieient objection to preserve an

al1eged1y erroneous iury instruction vaives the alleged

error for purposes of appellate revier. Eil1 v. -ttgt9'

409 So .2A 94, (Ara. Crin. App. 1 981 ).

t{orever the obJection ie valved unless nade before

the Jury retires. Shovers v. State, 4O7 So'2d 169, 172

(na. I981 )

The only relevant objection made at the end of the 7

trial court's oral charge was: ,/

. . .The Court. . . eharged the jury on

periury under Title 11. We objeet to

that portion of the eourt's charge'

(n. 315)

No grounds for the objection vere assigned '

since petitioner matle no objection sufficient to

preserve for appellate revier any issue as to the trial

eourt's orai charge, petitioner failec to conply with

Alabana proceiuial 1aw. Therefore, the motion for

summary jud.gment is d.ue to be denied, and tne petition is

due tO be Cenied On a}l assertiOns cgncernlng the trlal

courtrs Oral chargc unless petitiOner e&n show eause fOr

failure to object and actual prejudice resultlng fron the

charge. HalnwrLght v. Sykes, 455 U.S' 72 (1977)'

Respectfu}ly submttted',

AITOR}IEY GENERAI'

ISTANT ATIORIEY GEI{ERA],

ASSISIANT ATTORSTIY GENERAI

I

g_qB!!q r c {I_E_qE -qEruqE

I hereby certify that on this Z4th day of Febru&rX,

1984, I dld serve a copy of the foregoing on the attorney

for Petitioner, Yanzetta Penn Durant, 619 ltlartha street'

lrlontgonery, Alabana ,5108, bX hancl dellvery'

ATTORNEY GENERAI

ASSISIANT AITORNEY GE}TERAL

A

ASSISTANT

9