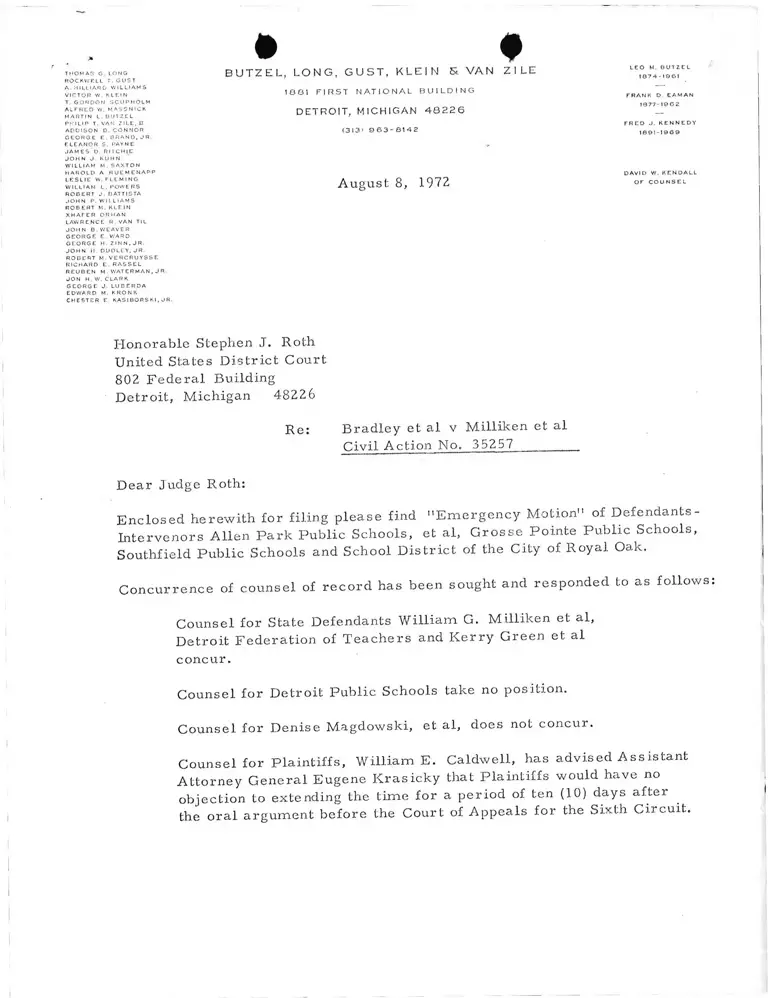

Letter to Judge Roth from Saxton RE: Emergency Motion of Defendants-Intervenors

Public Court Documents

August 8, 1972

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Letter to Judge Roth from Saxton RE: Emergency Motion of Defendants-Intervenors, 1972. 210e406f-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ecd7ad71-c07b-47cc-b0e3-fcd010501dbb/letter-to-judge-roth-from-saxton-re-emergency-motion-of-defendants-intervenors. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

L E O M. B U T Z E L

1 0 7 4 - 1 9 6 1T H O M A S G . L O N G

R O C K Vi/E L L T . G U S T

A . H I L L I A R D W I L L I A M S

V I C T O R W. K L E I N

T. G O R D O N S C U P H O L M

A L F R E D W. M A S S N I C K

M A R T I N L . B U T Z E L

P H I L I P T. V A N Z l t . E , I I

A D D I S O N D . C O N N O R

G E O R G E E . B R A N D , J R .

E L E A N O R S . P A Y N E

J A M E S D. R I T C H I E

J O H N J . K U H N

W I L L I A M M . S A X T O N

H A R O L D A . R U E M E N A P P

L E S L I E W. F L E M I N G

W I L L I A M L . P O W E R S

R O B E R T J . B A T T I S T A

J O H N P. W I L L I A M S

R O B E R T M . K L E I N

X H A T E R O R H A N

LAW R E N C E R . V A N T I L

J O H N B . W E A V E R

G E O R G E E . W A R D

G E O R G E H. Z I N N , J R .

J O H N H . D U D L E Y . J R .

R O B E R T M . V E R C R U Y S S E

R I C H A R D E . R A S S E L

R E U B E N M . WA T E R M A N , J R .

J O N H . W. C L A R K

G E O R G E J . L U B E R D A

E D W A R D M. K R O N K

C H E S T E R E. K A S 1 B O R S K I , J R .

B U T Z E L , L O N G , G U S T , K L E I N S> V A N Z I L E

1 8 8 1 F I R S T N A T I O N A L B U I L D I N G

DE T RO IT , M I C H I G A N 4 8 2 2 6

(3 13 > 963-8142

August 8, 1972

F R A N K D. E A M A N

1 8 7 7 - 1 9 6 2

F R E D J . K E N N E D Y

1 6 9 1 - 1 9 6 9

D A V I D W . K E N D A L L

O F C O U N S E L

H onorab le Stephen J. Roth

United States D is t r i c t Court

802 F e d e r a l Bui lding

D etro i t , M ich igan 48226

R e : B r a d le y et a l v M i l l iken et al

C iv i l A c t i o n No. 35257__________

D ear Judge Roth:

E n c l o s e d herew ith f o r f i l ing p lease find " E m e r g e n c y M ot ion" of D e fe n d an ts -

In tervenors A l le n P a r k Pu b l i c S ch oo ls , et al, C r o s s e Po in te P u b l i c S choo ls ,

Southfie ld P u b l ic S choo ls and S ch oo l D is t r i c t of the City o f R o y a l Oak.

C o n c u r r e n c e of c o u n se l of r e c o r d has been sought and r e sp o n d e d to as f o l l o w s

Counse l f o r State Defendants W i l l i a m G. M i l l iken et al,

D etro i t F e d e r a t i o n of T e a c h e r s and K e r r y G reen et al

c o n c u r .

C ou nse l f o r D e tro i t Pu b l ic Schoo ls take no pos i t ion .

Cou nse l f o r D en ise M agdow sk i , et al , does not c o n cu r .

C o u n s e l f o r P la int i f f s , W i l l i a m E. Caldwel l , has a d v ise d A s s i s ta n t

A t to r n e y G e n e r a l Eugene K r a s i c k y that P la int i f fs would have no

ob je c t ion to extending the t ime f o r a p e r io d of ten (10) days after

the o r a l argu m en t b e f o r e the Court of A p p ea ls f o r the Sixth C ircu it .

4

H onorab le Stephen J. Roth

August 8, 1972

P a ge Tw o

Inasmuch as the o r a l a rgu m e n t b e f o r e the Sixth C ir cu i t Court of Ap p ea ls is

August 24, 1972, and ten (10) days a f ter such date would be Sunday, Septem be

1972, and the M onday therea fter being a hol iday, L a b o r Day, Cou nse l f o r

D e fe n d a n ts - In te r v e n o r s have reques ted an ex tens ion f o r f i l ing o b je c t io n s ,

m o d i f i c a t io n s and a l ternat ives to the r e c o m m e n d a t i o n s of the d e se g r e g a t io n

P a n e l and State Superintendent of Pu b l i c Instruct ion until Tuesday , S ep tem b er

1972.

S i ” " ' " ' ' ' 1 ”

W il l ia m M. Saxton

4 4 / l j d

e n d

c c : A l l C ou nse l of R e c o r d

F r e d e r i c k W. Johnson, C lerk

of the Court