Carmical v. Craven Supplemental Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

April 20, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carmical v. Craven Supplemental Brief for Respondent, 1971. f1e427ca-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ed66b698-d252-4238-ab72-bef990048df9/carmical-v-craven-supplemental-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Copied!

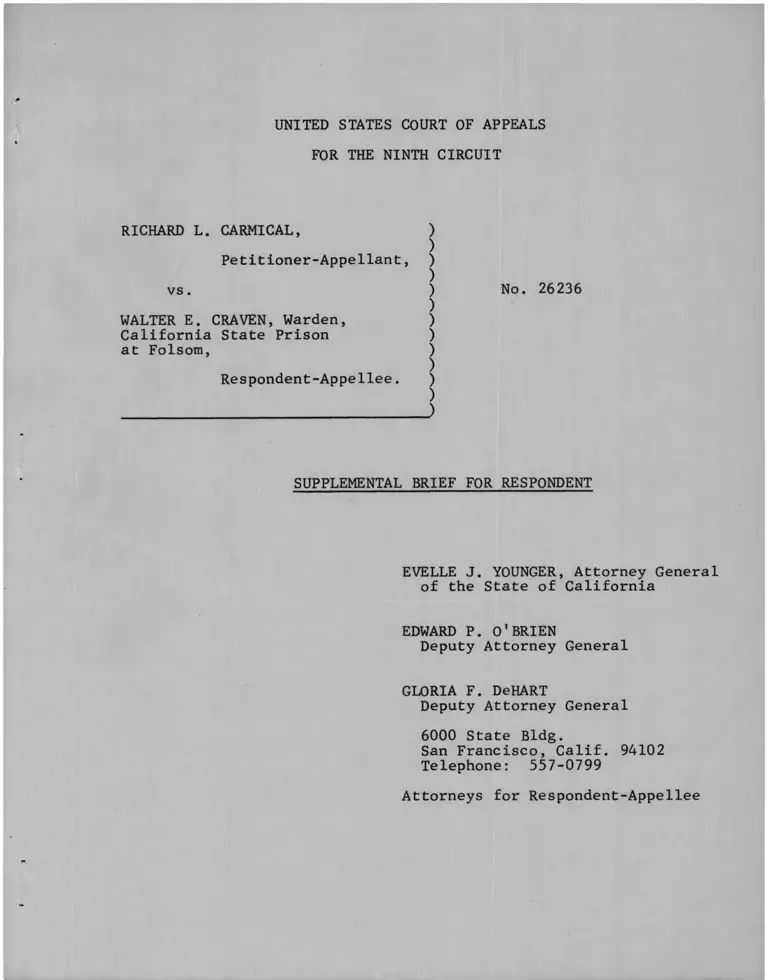

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

RICHARD L. CARMICAL, )

)

Petitioner-Appellant, )

)

vs. )

)

WALTER E. CRAVEN, Warden, )

California State Prison )

at Folsom, )

)

Respondent-Appellee. )

)

_________________________________________________ )

No. 26236

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

EVELLE J. YOUNGER, Attorney General

of the State of California

EDWARD P. O'BRIEN

Deputy Attorney General

GLORIA F. DeHART

Deputy Attorney General

6000 State Bldg.

San Francisco, Calif. 94102

Telephone: 557-0799

Attorneys for Respondent-Appellee

TABLE OF CASES

j

Page

Carter v. Jury Commission,

369 U.S. 320 (1970) 3

Griggs v. Duke Power Company,

39 U.S.L.W. 4317 (1970) 1, 2, 3, 4

Turner v. Fouche,

369 U.S. 346 (1970) 3

STATUTES AND AUTHORITIES

2, 3

Civil Rights Act

§ § 703 (a) , (h)

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

RICHARD L. CARMICAL, )

)

Petitioner-Appellant, )

)

vs. ) No. 26236

)

WALTER E. CRAVEN, Warden, )

California State Prison )

at Folsom, )

)

Respondent-Appellee. )

)

____________________________________________________ )

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

Petitioner has filed a "Supplemental Brief for

Appellant" calling this Court's attention to the recently

decided case, Griggs v. Duke Power Company, No. 124,

Oct. 1970, 39 U.S.L.W. 4317, and urging that the reason

ing of Griggs is dispositive of the issue before this

Court in the instant case. We disagree with petitioner's

analysis and interpretation of Griggs.

The Court in Griggs indicated that it granted

review

"to resolve the question whether an employer is

prohibited by the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

Title VII, from requiring a high school educa

tion or passing of a standardized general

intelligence test as a condition of employment

in or transfer to jobs when (a) neither standard

is shown to be significantly related to

1.

n

successful job performance, (b) both requirements

operate to disqualify Negroes at a substantially

higher rate than white applicants, and (c) the

jobs in question formerly had been filled only by

white employees as part of a longstanding practice

of giving preference to whites.

Section 703(a) of the Civil Rights Act provides

inter alia that it shall be an unlawful practice for an

employer to classify his employees in ways to adversely

affect his status because of his race, color, religion,

sex or national origin. Section 703(h) provides that it is

not unlawful to give or act on the results of a profession

ally developed ability test provided the test "is not

designed, intended or used to discriminate because of race,

color, religion, sex or national origin."

The Court in Griggs was concerned solely with

interpreting the meaning of the Act. The Court noted that

the objective of Congress was to achieve equality of job

opportunities and remove past barriers:

"Under the Act, practices, procedures or tests

neutral on their face, and even neutral in terms

of intent cannot be maintained if they operate to

'freeze' the status quo of prior discriminatory

employment practices. . . . What is required by

Congress is the removal of artificial, arbitrary,

and unnecessary barriers to employment when the

barriers operate invidiously to discriminate on

2.

the basis of racial or other impermissible

classification. . . . The Act proscribes not

only overt discrimination but also practices

that are fair in form but discriminatory in

operation. The touchstone is business neces

sity. If an employment practice which

operates to exclude Negroes cannot be shown

to be related to job performance, the practice

is 'prohibited.' Id. at 4319.

The Court then went on to discuss the meaning of

section 703(h) authorizing tests not "designed, intended or

used to discriminate . . . " (Emphasis added by Court). The

Court noted that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

with enforcement responsibility, had issued guidelines inter

preting this section to permit only the use of job related

tests. The Court then reviewed the legislative history of

the Act and concluded that the guidelines expressed the will

of Congress. Id. at 4320-21.

Thus, the decision is based entirely on statutory

construction and not on constitutional requirements. We

submit that such a decision interpreting a statute and

related to the entirely different problems of employment is

entirely inapplicable to the instant case. There is no

constitutional violation in a jury selection process unless

intentional discrimination on grounds of race is shown.

The Griggs case does not change in any way the position of

the Court expressed in Carter v. Jury Commission, 369 U.S.

320 (1970) and Turner v. Fouche, 369 U.S. 346 (1970). The

3.

"clear-thinking" test formerly used in Alameda County may

not have been a perfect measure of intelligence, but it did

not "measure" race and the record is clear that there was

no purposeful discrimination based on race.

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons and those expressed in

Respondent's Brief, we respectfully request that the

decision of the District Court denying the petition be

affirmed.

Dated: April 20, 1971.

EVELLE J. YOUNGER, Attorney General

of the State of California

EDWARD P. O'BRIEN

Deputy Attorney General

GLORIA F. DeHART

Deputy Attorney General

Attorneys for Respondent-Appellee

G F D :EB

SF CR 013359

4 .

I