Yuen v. International Revenue Service Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

August 17, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Yuen v. International Revenue Service Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1981. f40910c8-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ed8fc982-e63b-41d6-8040-0ed17bc3c8f1/yuen-v-international-revenue-service-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

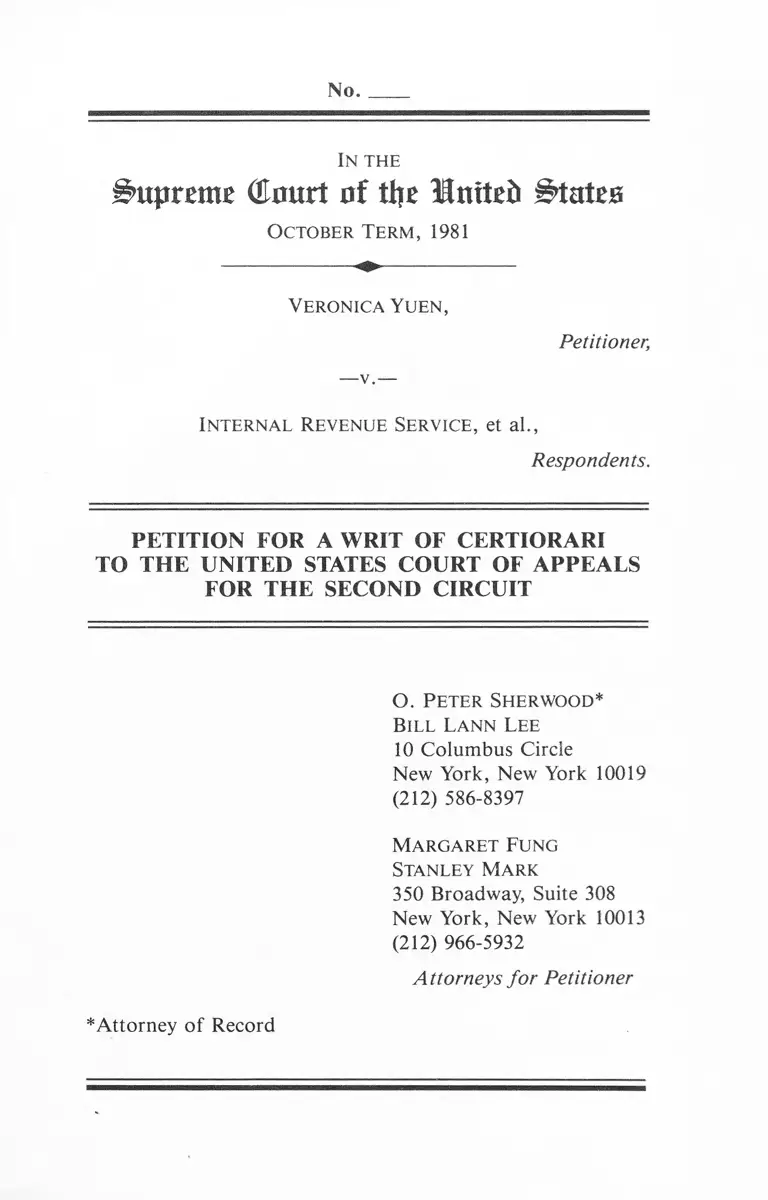

No.

In the

Court of tt?c lEntteii States

October Term , 1981

Veronica Yuen,

Petitioner,

—v.—

Internal Revenue Service, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

O. Peter Sherwood*

Bill Lann Lee

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Margaret Fung

Stanley Mark

350 Broadway, Suite 308

New York, New York 10013

(212) 966-5932

A ttorneys for Petitioner

*Attorney of Record

- 1 -

Petitioner respectfully prays for a writ

of certiorari to review the judgment of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Second

Circuit in this case.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the Second Circuit's narrow

interpretation of the provision "A person who

owes allegiance to the United States" in the

\

Appropriations Act, 31 U.S.C. § 699b, which

prohibits federal employment of a majority

of aliens, conflicts with this Court's

decision in Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, 426 U.S.

88 (1976)?

2. Whether the Appropriations Act, 31

U.S.C. § 699b, invidiously discriminates

against some aliens over others on the basis

of national origin, in violation of the Fifth

Amendment?

-11-

The petitioner, plaintiff-appellant below,

is VERONICA YUEN.

The respondents, defendants-appellees

below, are the INTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE;

GEROME KURTZ, in his capacity as Commissioner

of the Internal Revenue Service; JOHN IMBESI,

JOSEPH TRAGNA, H. KRAMER and CAROLE BUTLER,

in their official capacities as agents/employees

of the Internal Revenue Service.

LIST OF THE PARTIES

- l l l -

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ................... i

LIST OF THE PARTIES................... ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS........................iii

TABLE OF AUTHOR I T I E S................. iv

OPINIONS B E L O W ............ 1

JURISDICTION ......................... 1

STATUTORY PROVISION INVOLVED ........ 2

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ................. 3

\

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W R I T ........ 7

I. THE SECOND CIRCUIT'S RESTRICT

IVE CONSTRUCTION OF "A PERSON

WHO OWES ALLEGIANCE TO THE

UNITED STATES" UNDER THE APPRO

PRIATIONS ACT, 31 U.S.C. § 699b,

IS IN DIRECT CONFLICT WITH A

PRIOR DECISION OF THIS COURT. . . 8

II. THE APPROPRIATIONS ACT, 31

U.S.C. § 699b, VIOLATES THE

FIFTH AMENDMENT BY INVIDIOUSLY

DISCRIMINATING AGAINST SOME

ALIENS OVER OTHERS ON THE

BASIS OF NATIONAL ORIGIN........ 16

C O N C L U S I O N ............................ 24

APPENDIX

Opinion of the Court of Appeals . . . A1

Opinion of the District Court . . . . A13

-iv-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Edelman v. Jordan,

415 U.S. 651 (1974)............... 15

Cases Page

Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong,

424 U.S. 88 (1976), on

remand, 435 F. Supp. 37

(N.D. Cal. 1977), aff'd,

626 F.2d 739 (9th Cir.

1980), cert, denied,

101 S. Ct. 1419 (1981).............passim

Hines v. Davidowitz,

312 U.S. 52 (1941) .................. 16

Hirabayashi v. United States,

320 U.S. 81 (1943)................. 21

Lorillard v. Pons,

434 U.S. 575 (1978)............... 13

Mathews v. Diaz,

426 U.S. 67 (1976)................. 16,18,19

21,23

Narenji v. Civiletti,

617 F .2d 745 (D.C. Cir.

1979), cert, denied,

446 U.S. 957 (1980)............... 19

Petitioner for Naturalization

of Olegario v. United States,

629 F .2d 204 (2d Cir. 1980) . . . . 21

-v-

Ramos v. Civil Service

Commission, 430 F. Supp.

422 (D.P.R. 1977) (three

judge c ourt)................... 19

Truax v. Raich, 239 U.S. 33

(1915) 20

Vergara v. Hampton, 581

F .2d 1281 (7th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied, 441 U.S. 905

T1979) . . .......................... 19

Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld,

420 U.S. 636 (1975)................. 23

Yassini v. Crosland, 618 F.2d

1356 (9th Cir. 1 9 8 0 ) ............... 19

\

Other Authorities

8 U.S.C. § 1101....................... 9

28 U.S.C. § 1254 (1)................... 1

28 U.S.C. § 1 3 3 1 ..................... 5

28 U.S.C. § 1 3 6 1 ................. .. . 5

31 U.S.C. § 6 9 9 b .......................passim

Pub. L. No. 91-144 (1970)............. 9

Executive Order 11935,

41 Fed. Reg. 37301

(Sept. 3, 1976)................... 11,12,19

Cases Page

Other Authorities Page

5 C.F.R. § 213.3101(a) 3

5 C.F.R. § 338.101 ................. 9

Rule 20.2, Supreme Court Rules . . . . 1

Rosberg, "The Protection of

Aliens From Discriminatory

Treatment By the National

Government," 1977 S. Ct.

Rev. 275 ............................ 20

-vi-

-1-

OPINIONS BELOW

The decision of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Second Circuit, No. 80-6206

(2d Cir. May 21, 1981), not yet reported, is

attached hereto as Appendix A. The opinion

of the United States District Court for the

Southern District of New York, reported at

497 F. Supp. 1023 (S.D.N.Y. 1980), is attached

hereto as Appendix B.

\

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the U.S. Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit was entered on May 21,

1981. This petition for certiorari was filed

within ninety days of that date, as required

by 28 U.S.C. § 2101(c) and Rule 20.2 of the

Supreme Court Rules. This Court's juris

diction is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

-2-

STATUTQRY PROVISION INVOLVED

31 U.S.C. § 699b (1981 Supp.)/ codifying

Pub. L. No. 96-74, Title VI, § 602:

Unless otherwise specified during the

current fiscal year no part of any appro

priation shall be used to pay the compensa

tion of any officer or employee of the Govern

ment of the United States (including any

agency the majority of the stock of which is

owned by the Government of the United States)

whose post of duty is in continental United

States ̂ unless such person (1) is a citizen of

the United States, (2) is a person in the

service of the United States on September 29,

1979, who, being eligible for citizenship,

has filed a declaration of intention to

become a citizen of the United States prior

to such date and is actually residing in the

United States, (3) is a person who owes

allegiance to the United States, (4) is an

alien from Cuba, Poland, South Vietnam, or

the Baltic countries lawfully admitted to

the United States for permanent residence, or

(5) South Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian

refugees paroled into the United States be

tween January 1, 1975, and September 29, 1979:

Provided, That for the purpose of this section,

an affidavit signed by any such person shall

be considered prima facie evidence that the

requirements of this section with respect to

his status have been complied with: Provided

further That any person making a false affi

davit shall be guilty of a felony, and, upon

conviction, shall be fined not more than

$4,000 or imprisoned for not more than one

year, or both: Provided further, That the

above penal-clause shall be in addition to,

and not in substitution for any other pro

visions of existing law: Provided further,

That any payment made to any officer or

employee contrary to the provisions of this

-3-

section shall be recoverable in action by the

Federal Government. This section shall not

apply to citizens of Israel, the Republic of

the Philippines or to nationals of those

countries allied with the United States in

the current defense effort, or to temporary

employment of translators, or to temporary

employment in the field service (not to

exceed sixty days) as a result of emergencies.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioner Veronica Yuen was born in

China and is an alien lawfully admitted for

permanent residence in the United States. In

April 1980, while completing her second year

at Brooklyn Law School, petitioner applied

* /for a GS-7 excepted civil service position—

as a legal research assistant in the Appeals

Office of the Internal Revenue Service

[hereinafter "IRS"], located in New York City.

Her duties were to assist Appeals Officers in

researching tax issues and other case-related

technical support activities. Although the

*/ Excepted civil service positions are those

which are not filled by competitive examina

tion. 5 C.F.R. § 213.3101(a).

-4

job advertisement did not state that aliens

were barred from employment, petitioner

disclosed her lawful permanent resident

status both in her application and at the

employment interview.

On May 29, 1980, John Imbesi, Associate

Chief of the New York City Appeals Office of

the IRS, orally offered petitioner the

position, to begin June 2, 1980. She was to

work full time during the summer and part

time during her third academic year. Peti

tioner obtained a release from a prior employ

ment commitment, called Mr. Imbesi and accepted

the offer. Later that day, an IRS represen

tative called and left word that the offer

was rescinded because petitioner was not a

United States citizen. The IRS's sole basis

for withdrawing her employment offer was

section 699b of the Appropriations Act, since

IRS stood ready to appoint her to the position

should she prevail in the litigation.

-5-

Petitioner executed the following affi

davit bearing her oath of allegiance to the

United States:

I, Veronica Yuen, do solemnly

swear (or affirm) that I will

support [and] defend the Con

stitution of the United States

against all enemies, foreign

and domestic; that I will bear

true faith and allegiance to

the same. So help me God.

On June 4, 1980, she filed an action in

federal district court, pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§§ 1331, 1361 and the Fifth Amendment of the

United States Constitution, against the IRS

and named officials because they denied her

employment due to her alienage. She sought

$10,000 in damages and an order to hire her.

The district court conceded that in

Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, 426 U.S. 88 (1976),

this Court clearly decided that aliens are

eligible for federal employment under the

same provision contained in similarly-worded

predecessor appropriations acts. Nonetheless,

the district court declined to follow Hampton

-6-

and instead relied upon obscure excerpts of

pre—Hampton legislative history to conclude

that aliens, such as petitioner, are barred

from federal employment. With respect to the

constitutional issue, the district court

correctly applied an intermediate equal

protection standard but found that the statu

tory classification drawn by Congress further

ed sufficiently important governmental

interests to satisfy Fifth Amendment due

process requirements. Summary judgment was

granted in favor of defendants, and the

complaint was dismissed. On appeal, the

Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed for

the reasons set forth in the district court's

opinion.

-7-

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The Second Circuit's decision--the only-

reported opinion interpreting the Appropria

tions Act--involves the important question of

the extent to which Congress may discriminate

against legal permanent resident aliens in

federal employment.

Viewed as a matter of statutory con

struction, the decision below conflicts with

this Court's decision in Hampton v. Mow Sun

\

Wong, supra, which ruled that aliens may take

an oath of allegiance and be eligible for

federal employment.

However, if the Appropriations Act is

construed to exclude aliens from federal

employment, this Court is squarely presented

with the constitutional question left open

in Hampton: whether a congressional ban on

the employment of aliens by the federal

government violates equal protection prin

ciples encompassed in the Fifth Amendment.

See Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, supra, 426 U.S.

-8

at 114, 117 (Brennan and Marshall, JJ.,

concurring). If the constitutional issue is

reached, this case provides the Court with an

opportunity to clarify the standard by which

congressional action limiting the rights of

aliens should be reviewed under the Fifth

Amendment.

I. THE SECOND CIRCUIT'S RESTRICTIVE

CONSTRUCTION OF "A PERSON WHO

OWES ALLEGIANCE TO THE UNITED

STATES" UNDER THE APPROPRIATIONS

ACT, 31 U.S.C. § 699b, IS IN

DIRECT CONFLICT WITH A PRIOR

DECISION OF THIS COURT.

In Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, supra, this

Court conclusively construed the term "A

person who owes allegiance to the United

States" to include aliens who take an oath

of allegiance. At issue in Hampton was a

Civil Service Commission [hereinafter "CSC"]

regulation which provided that a person could

be appointed to a competitive civil service

position "only if he is a citizen of or owes

permanent allegiance to the United States,"

-9-

5 C.F.R. §338.101(1976)— i.e., a citizen

* /or a noncitizen national- of the United

States.

Plaintiffs in Hampton argued that the

regulation was inconsistent with section 502

of Pub. L. No. 91-144 (1970), a substantially

similar predecessor of the Appropriations

Act here, which provided that appropriated

funds could only be paid to a citizen or "a

\

person who owes allegiance to the United

States." 333 F. Supp. 527, 530, 531 (N.D.

Cal. 1971); 426 U.S. at 93, n.6 and accom

panying text.

This Court invalidated the regulation

under the Fifth Amendment's due process

clause, holding that "[s]ince these residents

were admitted as a result of decisions made

by the Congress and the President . . . due

process requires that the decision to impose

V A "national" is defined as "a person

owing permanent allegiance to a state."

8 U.S.C. § 1101 (1980).

10-

that deprivation of an important liberty be

made . . . at a comparable level of govern

ment . . . ." 426 U.S. at 116. Central to

this holding was a careful review of the

language, purpose and legislative history of

appropriations acts since 1938 and, specifi

cally, the "owes allegiance" provision at

issue here. See id. at 107-12. This Court

thus concluded: "Congress has regularly

provided for compensation of any federal

employee owing allegiance to the United States.

Since it is settled that aliens may take an

appropriate oath of allegiance, the statutory

category, though not precisely defined, is

plainly more flexible and expansive than the

Commission rule." Id. at 110. Since this

Court decided the statutory question at issue

in this case, principles of stare decisis

should control.

-11-

Moreover, Congress has demonstrated its

acquiescence in the clear holding of Hampton

by failing to modify the terms of the Appro

priations Act to exclude aliens who take an

oath of allegiance.

After Hampton was decided, the President

issued Executive Order 11935 of September 2,

1976, which states that no "person" shall be

admitted to competitive examination or given

any appointment in the competitive service

"unless such person is a citizen or national

of the United States," except that the Commis

sion may "authorize the appointment of aliens

to positions in the competitive service when

necessary to promote the efficiency of the

service in specific cases or for temporary

appointments. 41 Fed. Reg. 37301 (Sept. 3,

1976). At the time, the President stated:

"In its decision, the Court stated that either

Congress or the President might issue a broad

prohibition against the employment of aliens

in the civil service, but held that neither

Congress nor the President had mandated the

-12-

general prohibition." Letter of the President

to the Speaker of the House, accompanying

Executive Order 11935 of September 2, 1976.

41 Fed. Reg. 37301, 37303 (September 3, 1976).

Both the executive order and the letter refer

specifically to the "competitive service."

However, neither the President nor

Congress has changed the terms of the yearly

appropriations act or otherwise affected the

status of the excepted service, such as the

position sought by petitioner. Thus, although

the appropriations acts clearly apply to both

competitive and excepted service, see pp. 2-3

supra, Congress has acquiesced in the con

struction of the appropriations act given by

Hampton as to excepted service positions, and

reenacted the act as construed by Hampton.

Plainly, Congress or the President knew of

Hampton and could have acted to modify the

terms of the appropriations act if they desired

to because the President did, in fact, act as

to competitive positions.

-13-

Since "Congress is presumed to be aware of

. , . [a] judicial interpretation of a statute

and to adopt the interpretation when it re

enacts a statute without change," Lori Hard

v. Pons, 434 U.S. 575, 580-81 (1978) and

authorities cited therein, it is clear that

Hampton remains controlling authority with

respect to this case.

The Second Circuit's characterization

of dispositive passages in Hampton as dicta

was erroneous for a number of reasons.

First, this Court necessarily relied upon

the "owes allegiance" provision of that

appropriations act in determining that the

class of persons eligible for employment

under the statute was broader than the class

eligible under the CSC regulation. Hampton

held that the statute is "plainly more

flexible and expansive" than the CSC rule

-14 -

precisely because "Congress has regularly

provided for compensation of any federal

employee owing allegiance to the United

States" and "it is settled that aliens

may take an appropriate oath of allegiance."

Id. at 109-10.

Second, the statutory question was

clearly decided since the Hampton plaintiffs

in fact had standing only to challenge the

impermissible narrowing of the "owes

allegiance" provision. It appears that

the Hampton plaintiffs were not eligible

for employment under any other statutory

* /classification,- and two of the plaintiffs

filed affidavits swearing allegiance to the

United States, thereby confirming their

*_/ The other classifications included 1) citi

zens; 2) certain persons declaring their intent

to become citizens; 3) certain aliens from Cuba,

Poland, South Vietnam, or the Baltic countries;

4) certain Southeast Asian refugees; 5) citizens

of Israel, the Philippines or nationals of

countries allied in the "current defense effort"

or emergency temporary service. See pp. 2-3

supra.

-15-

standing to challenge the "owes allegiance"

provision.

The controlling effect of Hampton on

the statutory question in this case is further

supported by the fact that it was decided

only after this Court's thorough review of

the language, legislative history and Presi

dential interpretation of the "owes allegiance"

provision. Id. at 108-11. Since this

question was not decided in a summary

fashion, compare with Edelman v. Jordan,

415 U.S. 651, 670-71 (1974), the doctrine

of stare decisis bans relitigation of

settled law that an alien who takes an

oath of allegiance is considered "a person

who owes allegiance to the United States"

and thus is eligible for federal employment.

-16-

II. THE APPROPRIATIONS ACT,

31 U.S.C. § 699b, VIOLATES

THE FIFTH AMENDMENT BY

INVIDIOUSLY DISCRIMINATING

AGAINST SOME ALIENS OVER

OTHERS ON THE BASIS OF

NATIONAL ORIGIN.

This Court has stated that Congress

has broad power to restrict the rights of

aliens residing in this country. See, e.g.,

Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, supra, 426 U.S. at

118; Mathews v. Diaz, 426 U.S. 67, 81-82

(1976); Hines v. Davidowitz, 312 U.S. 52,

69-70 (1941). While judicial scrutiny of

federal governmental action in this area

is admittedly narrow, the full reach of

the equal protection component of the Fifth

Amendment's due process clause has

-17-

not been precisely defined, and the standard

of review for federal classifications based

on alienage remains obscure.

In Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, supra, this

Court noted that "overriding national interests

may provide a justification for a citizenship

requirement in federal service even though an

identical requirement may not be enforced by

a State." 426 U.S. at 101. The Court none-%

theless recognized certain limits upon

federal power and thus cautioned that "[w]e do

not agree, however, with the petitioners'

primary submission that the federal power

over aliens is so plenary that any agent of

the National Government may arbitrarily sub

ject all resident aliens to different sub

stantive rules from those applied to citizens."

Ih. However, with respect to an express

Congressionally-mandated rule, i.e., a statute,

the Court stated that it "might presume that

any interest which might rationally be served

by the rule did in fact give rise to its

-18-

adoption." Id. at 103 (emphasis added). No

indication was given as to the particular

considerations that would govern such a pre

sumption .

Mathews v. Diaz, supra, decided on the

same day as Hampton, involved a federal

regulation that discriminated within

the class of aliens by restricting Medicare

benefits to aliens who were admitted for

permanent residence and who had continuously

resided in the United States for five years.

Applying an apparently more relaxed standard

than in Hampton, this Court upheld these

eligibility requirements affecting only

certain aliens since neither requirement was

"wholly irrational." 426 U.S. at 83.

The instant case raises a question

regarding federal alienage classifications

that differs substantially from other cases

previously decided by this Court. Unlike

Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, supra, and its

-19-

* /progeny,— the issue here does not involve

a provision that draws a clear unvarying line

between citizens and all aliens. Nor does

the Appropriations Act make distinctions

within a class of aliens on the basis of a

neutral dividing line, such as the residency

requirement in Mathews v. Diaz, supra. In

addition, the Appropriations Act does not

constitute a direct exercise of Congress's

%

plenary power to admit and exclude aliens

or to implement foreign policy decisions.

See, e.g., Yassini v. Crosland, 618 F.2d 1356

1360 (9th Cir. 1980) (upholding revocation

of deferred departure dates for Iranian

nationals under deportation orders); Naren]i

*/ See, e.g., Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, 435

F. Supp. 37 (N.D. Cal. 1977), aff'd, 626 F .2d

739 (9th Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 101 S. Ct.

1419 (1981) (on remand); Vergara v. Hampton,

581 F .2d 1281 (7th Cir. 1978), cert, denied,

441 U.S. 905 (1979); Ramos v. Civil Service

Commission, 430 F. Supp. 422 (D.P.R. 1977)

(three judge court) (upholding constitutional

ity of Executive Order 11935).

-20-

v. Civiletti, 617 F.2d 745, 747 (D.C. Cir.

1979), cert, denied, 446 U.S. 957 (1980)

(upholding reporting requirements applied

only to Iranian nationals). See generally

Rosberg, "The Protection of Aliens From

Discriminatory Treatment by the National

Government," 1977 Sup. Ct. Rev. 275.

Instead, the Appropriations Act creates

distinctions that permit federal employment

of specifically-exempted aliens, defined by

their national origin,-' but deprives all

other aliens of an important interest in

liberty.— Such distinctions based on

national origin have long been acknowledged

to be "odious to a free people whose institu

tions are founded upon the doctrines of

*/ See pp. 2-3 supra for enumerated categories

of exempted aliens.

**/ This Court acknowledged in Hampton that

"ineligibility for employment in a major sector

of the economy [the federal government] . . .

is of sufficient significance to be character

ized as a deprivation of an interest in liberty.

426 U.S. at 102. See also Truax v. Raich, 239

U.S. 33, 41 (1915)“ “

-21-

equality." Hirabayas'hi vY United States, 320

U.S. 81, 100 (1943). Where, as here, Congress

selectively deprives certain aliens of a sig

nificant liberty interest under the due process

clause on the basis of national origin, a

higher level of judicial scrutiny should be

required or, at minimum, a more clearly arti-

culated standard than the vague criteria set

forth in Hampton and Mathews.

* /Whatever standard of review xs applied,

the Second Circuit erroneously concluded that

section 699b rationally furthers the federal

interests asserted by the government below.

In support of its position, respondents con

tended that the statutory provision gives the

President a bargaining chip in negotiating

defense alliances, encourages naturalization

and provides Congress with an expendable

**7 While the district court in the instant

case applied an intermediate equal protection

standard, 497 F. Supp. 1023, 1037-39; accord,

Mow Sun Wong v. Hampton, 435 F. Supp. 37 (N.D,

Cal. 1977) (on remand)'';' Petition for Naturali

zation of Olegario v.' United States, 629 F . 2d

204 (2d Cir. 1980), the Second Circuit did not

decide what standard of review is appropriate.

No. 80-6206 (2d Cir. May 21, 1981), slip op.

at 3142.

-22-

foreign policy token— justifications which,

not surprisingly, coincide precisely with

what this Court posited in Hampton as possible

legitimate governmental interests. 426 u.S. at 104,

Even assuming that the federal interests

asserted are bona fide, the actual categories

of aliens exempted by the statute are either

underinclusive or overinclusive as implemen

tation of the interests asserted. First,

there is no evidence on the face of the Appro

priations Act or its legislative history

which demonstrates that, for instance, offer

ing federal employment to Cuban or Polish

lawful permanent resident aliens but not to,

say, Czech or Soviet permanent resident aliens

would serve as a "bargaining chip" or "token."

Nor is there any demonstration that federal

employment would be a better "bargaining chip"

or "token" than the refusal to hire certain

aliens (thus avoiding possible "brain drain"

in those countries). Moreover, it is difficult

to perceive how naturalization is encouraged

-23-

by exempting some but not all aliens on a

basis having nothing to do with what an

individual himself or herself could affect.

Finally, if a purpose of the Appropriations

Act is to prohibit federal employment of

persons who have not renounced their allegiance

to a foreign country, the statute does not

accomplish this goal; it allows Israeli and

Filipino citizens and certain aliens to qualify

for federal civil service positions.

As this Court stated in Weinberger v.

Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636, 648 (1975), "(T]he

mere recitation of a benign . . . purpose is

not an automatic shield which protects

against any inquiry into the actual purpose

underlying a statutory scheme." The skeletal

standard set forth in Hampton and Mathews

fails to permit any meaningful analysis of

actual governmental interests furthered by

the statutory provision and thereby allows

discriminatory federal legislation to stand

on mere hypothetical justifications. Given

-24-

the invidious nature of national origin classi

fications , the federal government should carry

a heavier burden to justify such distinctions

within the class of aliens. By reviewing this

case on certiorari, this Court can clarify the

degree to which Congress may restrict fundamen

tal rights of permanent resident aliens under

the Fifth Amendment.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, a writ

of certiorari should issue to review the

judgment below.

Respectfully submitted,

0. PETER SHERWOOD*

BILL LANN LEE

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

MARGARET FUNG

STANLEY MARK

Asian American Legal Defense

and Education Fund

350 Broadway, Suite 308

New York, New York 10013

(212) 966-5932

Attorneys for Petitioner

*Attorney of Record

Dated: New York, New York

August 17, 1981

A P P E N D I X

A1

U N IT ED STATES CO U RT OF A PPE A LS

For the Second C ircuit

----------- —--------- .

No. 858— September Term, 1980

(Argued February 18, 1981 Decided May 21, 1981)

Docket No. 80-6206

------ *■------

Veronica Yuen,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Internal R evenue Service, G erome Kurtz, in his ca

pacity as Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Ser

vice; John Imbesi, J oseph T ragna, H. Kramer and

C arole Butler, in their official capacities as agents/

employees o f the Interna! Revenue Service,

Defendants-Appellees.

B e f o r e :

Van G raafeiland and Kearse, Circuit Judges,

and Stewart,* District Judge.

---------------

Honorable Charles E. Stewart, of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York, sitting by designation.

3131

A 2

Appeal from a final judgm ent of the United States

District Court for the Southern District o f New York,

Leonard B. Sand, Ju d g e , 497 F. Supp. 1023, dismissing a

complaint challenging the denial of federal employment

to a resident alien under 31 U .S.C. § 699b.

Affirmed.

-------*-------

Bill Lan Lee , New York, New York

(Margaret Fung, Stanley M ark, Stephen

Gleit, O. Peter Sherwood, New York,

New York, of counsel), f o r P la in t i f f - A p

p e lla n t.

Steven E. O bus, Assistant United States

Attorney, New York, New York (John S.

Martin, Jr., United States Attorney for

the Southern District o f New York, Peter

C. Salerno, Assistant United States

Attorney, New York, New York, of coun

sel), f o r D e fe n d a n ts -A p p e lle e s .

-------«-------

Kearse, C ircu it J u d g e :

Plaintiff-appellant Veronica Yuen appeals from a final

judgm ent of the United States District Court for the

Southern District of New York, Leonard B. Sand, Ju d g e ,

dismissing her complaint against the United States In

ternal Revenue Service (“ IRS” ) and certain o f its employ

ees for denial o f employment with IRS. IRS refused to

employ Yuen on the ground that a statutory provision

entitled “ Citizenship requirement for federal employees

compensated from appropriated funds,” codified at 31

U .S.C . § 699b (Supp. Ill 1979) (hereinafter, together with

3132

A 3

its predecessor statutes, referred to as the “A ppropria

tions A c t” or the “ A ct” ), prohibits employment by the

federal government of persons other than United States

citizens and certain groups of noncitizens that IRS con

tends do not include Yuen. Yuen contended that the

proper construction of the Act does not, and could not

constitutionally, exclude her from employment. The dis

trict court upheld IR S’s interpretation of the Act and

ruled that the Act, as construed, does not deprive Yuen of

the equal protection of the law. We agree.

BACKGROUND

The case involves the interpretation and constitutional

ity of 31 U .S.C. § 699b which, in effect, prohibits the

federal government from employing in the continental

United States any person

unless such person (1) is a citizen of the United

States, (2) is a person in the service of the United

States on September 29, 1979, who, being eligible for

citizenship, has filed a declaration of intention to

become a citizen o f the United States prior to such

date and is actually residing in the United States, (3)

is a person who owes allegiance to the United States,

(4) is an alien from Cuba, Poland, South Vietnam,

or the Baltic countries lawfully admitted to the

United States for permanent residence, or (5) South

V ietnamese, C am bodian and Laotian refugees

paroled into the United States between January 1,

1975, and September 29, 1979 . . . .'

1 31 U.S.C. § 699b provides:

Unless otherwise specified during the current fiscal year no part

of any appropriation contained in this or any other Act shall be

3133

A 4

The relevant facts were stipulated and are set forth in

greater detail in the district cou rt’s opinion, reported at

497 F. Supp. 1023, familiarity with which is assumed.

Briefly, Yuen is a Chinese citizen, permanently residing in

the United States, who in April 1980 applied for employ

ment with the IRS. IRS offered Yuen a position, and she

accepted the offer on the same day, after terminating

other employment. Later that day, IRS realized that Yuen

was a citizen o f China rather than the United States (a

fact disclosed on her written application). Believing that

§ 699b barred its employment of Yuen, IRS promptly

informed her that citizenship was required for the posi

tion she had sought (a fact not disclosed in IRS’s solicita

tion o f applications), and that she was therefore not to

report for work with IRS.

Yuen commenced the present action, alleging breach of

contract and violation o f her rights to equal protection

used to pay the compensation of any officer or employee of the

Government of the United States (including any agency the major

ity of the stock of which is owned by the Government of the United

States) whose post of duty is in continental United States unless

such person [is in one of the five categories quoted in the text

accompanying this footnote]: Provided, That for the purpose of

this section, an affidavit signed by any such person shall be

considered prima facie evidence that the requirements of this

section with respect to his status have been complied with: Provided

further, That any person making a false affidavit shall be guilty of a

felony, and, upon conviction, shall be fined not more than $4,000

or imprisoned for not more than one year, or both: Provided

further, That the above penal-clause shall be in addition to, and not

in substitution for any other provisions of existing law: Provided

further, That any payment made to any officer or employee con

trary to the provisions of this section shall be recoverable in action

by the Federal Government. This section shall not apply to citizens

of Israel, the Republic of the Philippines or to nationals of those

countries allied with the United States in the current defense effort,

or to temporary employment of translators, or to temporary em

ployment in the field service (not to exceed sixty days) as a result of

emergencies.

3134

A 5

and due process. The complaint sought $10,000 in d am

ages and an injunction compelling IRS to hire Yuen.

A fter commencing the action, Yuen executed an affi

davit which stated as follows:

I, Veronica Yuen, do solemnly swear (or affirm)

that I will support [and] defend the Constitution of

the United States against all enemies, foreign and

domestic; that 1 will bear true faith and allegiance to

the same. So help me God.

Yuen contends, and IRS disputes, that on the basis of this

affidavit she “ is a person who owes allegiance to the

United States” within the meaning of category (3) of

§ 699b.2 In support of her position, Yuen pointed to the

opinion of the Supreme Court in H a m p to n v. M o w S u n

W ong, 426 U.S. 88 (1976), in which, while ruling on the

constitutionality of certain regulations of the United

States Civil Service Commission (“C SC ” or “Comm is

s ion”), the Court stated as follows:

Congress has regularly provided for compensation of

any federal employee owing allegiance to the United

States. Since it is settled that aliens may take an

appropria te oath of allegiance, the statutory cate

gory, though not precisely defined, is plainly more

flexible and expansive than the Commission rule.

Id . at 109 (footnote omitted). Yuen argued that she was

entitled to judgment on the basis of this language, plus

the provision in § 699b that “ for the purpose of this

Finding that IRS would have refused to hire Yuen even if she had

executed such an affidavit prior to the decision on her application, the

district court properly declined to base its decision on the technical

ground that Yuen apparently did not “owe [ ] allegiance” to the

United States at the time she was rejected.

3135

A 6

section, an affidavit signed by any such person shall be

considered prima facie evidence that the requirements of

this section with respect to his status have been complied

with . . . Alternatively, she argued that if the statute

were construed to bar her employment, it impermissibly

distinguished among aliens on the basis of their nationali

ties, in violation o f the Equal Protection Clause o f the

Constitution.

In an able opinion, Judge Sand granted summary

judgm ent dismissing the complaint. He held, first, that

the dicta in H a m p to n did not foreclose inquiry into the

meaning of § 699b(3), 497 F. Supp. at 1028; second, that

the language and legislative history of that section, rein

forced by the history o f similar language in other s ta tu

tory provisions, led to the conclusion that the phrase “ a

person who owes allegiance to the United States” was

intended to mean a noncitizen national of the United

States rather than a nonnational alien who merely exe

cutes an affidavit, id. at 1035-36; and finally, that C on

gress’s restriction on federal employment of aliens had a

sufficient relationship to appropriate congressional con

cerns that it did not violate the Constitution, id. at 1040.

DISCUSSION

We affirm principally on the basis of the district cou rt’s

thorough opinion, which we adopt, and content ourselves

here with a few observations.

A. H a m p to n v. M o w S u n W ong

We agree with the district court that H a m p to n v. M o w

S u n W ong, su p ra , did not definitively resolve the question

presented here, and that the Supreme C o u rt’s observa

tions with respect to the Appropriations Acts neither were

3136

A 7

nor were intended to be dispositive of the meaning of

“ owes allegiance.”

In H a m p to n , several resident aliens challenged the

constitutionality of a CSC regulation that permitted a

civil service appointment only if the candidate was “a

citizen of or owe[d] permanant allegiance to the United

States.” 5 C.F.R. § 338.101 (1976). After first concluding

that the question before it was the validity o f a CSC

regulation rather than the validity of a s ta tu te ,3 * 5 426 U.S.

at 98-105, the Supreme Court sought to determine

whether there had been Congressional approval or disap

proval of C SC ’s citizenship/nationalism requirement. In

so doing it reviewed the then-current and four prior

A ppropriations Acts, whose “owes allegiance” provisions

are identical to category (3) o f the current § 699b. The

C ourt found that the limitations on federal employment

provided by Congress in the Acts gave rise to conflicting

inferences as to whether or not the CSC rule was author

ized:

In the District Court respondents argued that the

exemptions from the limitations included in the A p

propriations Acts had become so broad by 1969 as to

constitute a congressional determination of policy

repudiating the narrow citizenship requirement in the

Commission rule. Though not controlling, there is

force to this argument. On the other hand, the fact

3 The Court had granted certiorari on the question:

Whether a regulation of the [CSC] that bars resident aliens from

employment in the federal competitive civil service is constitutional.

426 U.S. at 98-99. The defendants had devoted their argument instead

to the proposition that the CSC regulation was “within the constitu

tional powers of Congress and the President and hence not a constitu

tionally forbidden discrimination against aliens.” Id. at 99.

3137

A 8

that Congress repeatedly identified citizenship as one

appropria te classification o f persons eligible for com

pensation for federal service implies a continuing

interest in giving preference, for reasons unrelated to

the efficiency of the federal service, to citizens over

aliens. In our judgm ent, however, that fact is less

significant than the fact that Congress has consis

tently authorized payment to a much broader class of

potential employees than the narrow category of

citizens and natives o f American Samoa eligible un

der the Commission rule. Congress has regularly

provided for compensation o f any federal employee

owing allegiance to the United States. Since it is

settled that aliens may take an appropria te oath of

allegiance, [citing In re G r iff i th s , 413 U.S. 717, 726

n.18 (1973)], the statutory category, though not pre

cisely defined, is plainly more flexible and expansive

than the Commission rule. Nevertheless, for present

purposes we need merely conclude that the A ppro

priations Acts cannot fairly be construed to evidence

either congressional approval or disapproval of the

specific Commission rule challenged in this case.

Id . at 109-110.

We agree with the district cou rt’s conclusion that the

Supreme C o u r t’s discussion of the “ owes allegiance”

provision in the passage quoted above is not an au thori ta

tive construction necessary to the C o u r t’s determination

o f the validity o f the CSC regulation. First, the Court did

not purport to give a definitive interpretation of “ owes

allegiance” ; rather, it stated that the statutory category of

those owing allegiance was “ not precisely defined.” Id . at

109 (majority opinion); id. at 126 (Rehnquist, J . , dissent

ing). Moreover, although Yuen argues that the discussion

3138

A 9

of “ owes allegiance” was essential to the decision because

the H a m p to n plaintiffs were not eligible for federal em

ployment under any other category of the Appropriations

Act, we note that the meaning o f “owes allegiance” was

not considered an issue by the parties. The plaintiffs in

H a m p to n made no assertion that they qualified under the

“ owes allegiance” provision, 426 U.S. at 126 (Rehnquist,

J . , dissenting); and the Commission, for its part, did not

assert that employment of the plaintiffs was barred by the

A ppropriations Act. The Appropriations Acts were not

listed by the parties as relevant statutory provisions; and

none o f the briefs, including the three a m ic u s briefs filed,

argued the meaning o f the phrase “ owes allegiance.”

Finally, it is clear that the decision of the case did not turn

on a construction of “owes allegiance” favorable to the

plaintiffs, since only two of the plaintiffs executed affi

davits stating that they owed allegiance, and the C o u r t’s

judgm ent did not distinguish between the two who had

done so, and those who had not. The CSC regulation was

held invalid as to all o f them, and the basis of the

invalidity was not the Appropriations Acts: the Court had

concluded that those Acts could not fairly be construed as

either approval or disapproval of the CSC rule in issue.

Consequently, we concur that the Supreme C ou rt’s

discussion of “ owes allegiance” in H a m p to n was dictum,

and that the district court was bound to make its own

inquiry into the meaning o f the language.

B. C o n g r e s s ’s In te n t

We agree generally with the district cou rt’s analysis of

the language and history o f § 699b(3), and make the

following observations.

Yuen relies in part on H a m p to n for the proposition that

an affidavit such as she has executed here meets the

3139

A10

statutory requirement for p roof that she “owes alle

giance” to the United States. In H a m p to n , the Court

stated that “ it is settled that aliens may take an appropri

ate oath of allegiance,” 426 U.S. at 109, citing In re

G r if f i th s , 413 U.S. 717, 726 n.18 (1973), in which the

C ourt had rejected the proposition that only a citizen

could in good faith take an oath to support the Constitu

tion, and had held that a state may not restrict an

individual from practicing law on the basis o f alienage.

The proposition that an alien may in good faith take an

appropria te oath of allegiance to the United States, how

ever, does not compel the conclusion that Congress in

tended a conclusory oath to suffice to establish an alien as

a person who “ owes allegiance” to the United States, for

purposes of federal employment. Thus, the language of

H a m p to n and the ruling in G r if f i th s do not dispose o f the

question at issue here, which is not who may take an

oath , but rather what Congress meant by “ owes alle

giance.”

The intendment of category (3) must be assessed in

light o f Congress’s overall purpose in enacting § 699b.

S ee K o k o s z k a v. B e lfo rd , 417 U.S. 642, 650 (1974).

Contrary to Yuen’s suggestion that the “ overall statutory

purpose” of the Appropriations Act was to authorize

federal employment of a much broader class o f potential

employees than citizens and other nationals, we agree

with the district co u r t’s view that the o vera ll purpose of

the Act was restrictive.4 As originally proposed, the Act

would have limited federal employment strictly to citi-

The district court did not err by testing this conclusion against

analogous or related statutes since other statutes “not strictly in pari

materia but employing similar language and applying to similar per

sons, things, or cognate relationships may control by force of anal

ogy.” Stribling v. United States, 419 F.2d 1350, 1352 (8th Cir. 1969).

3140

A l l

zens. 83 Cong. Rec. 357, 713 (1938). Although that

proposed exclusivity was relaxed, the tenor of the statute

remains restrictive. The Act is phrased in negative terms:

it provides that no federally appropriated moneys may be

used to employ anyone who is not within the groups

listed. The congressional debate with respect to the “ owes

allegiance” category evinced concern for only limited

groups of aliens— most notably the Filipinos—who by-

virtue of their status, owed allegiance to the United

States. And the subsequently added special categories of

§ 699b, apparently enacted in response to international

political situations, have extended federal employability

to aliens from only specified countries, such as Poland,

Pub. L. No. 87-125, 75 Stat. 268, 282 (1961); Cuba, Pub.

L. No. 93-143, 87 Stat. 510, 525 (1973); South Vietnam,

Pub. L. No. 94-91, 89 Stat. 441, 458 (1975); and C am bo

dia and Laos, Pub. L. No. 95-429, 92 Stat. 1001, 1015

(1978). Congressional debate surrounding certain o f these

special extensions reveals a belief that such extensions are

the only means by which such an alien may obtain federal

employment. Thus, in arguing in favor of the most recent

exception for Cam bodian and Laotian refugees, C on

gressman Steed stated that “ [w ithou t this waiver, even

though they do come in legally as refugees, they would

not be allowed to work for the Federal Governm ent.” 124

Cong. Rec. H. 11439 (1978).

In short, we do not find support for the proposition

that Congress intended to allow the mere execution o f an

affidavit promising allegiance to convert any and every

alien into a person who “ owes allegiance” to the United

States within the meaning of § 699b.5

5 Cf. Woodward v. Rogers, 344 F. Supp. 974, 984 (D.D.C. 1972),

a ff’d, 486 F.2d 1317 (D.C. Cir. 1973) (table), construing the phrase

“owing allegiance” in the passport law, 22 U.S.C. § 212:

(footnote continued)

3141

A 1 2

C. The Constitutional Question

The district court ruled that § 699b, as interpreted to

deny federal employment to aliens whose sole claim o f

employability under § 699b was the execution o f an

affidavit swearing allegiance, did not deny Yuen equal

protection o f the law because it sought to further app ro

priate congressional goals. Yuen argues that although the

court correctly chose an “ intermediate” standard of re

view of the propriety of Congress’s classifications, it

erred in its conclusions that the statute evinced proper

congressional concerns. IRS, on the other hand, while

approving the district court’s conclusion, argues that only

minimal judicial scrutiny o f Congress’s actions was

appropria te and that § 699b must be upheld if it has any

rational basis.

While there is contemporaneous support for both posi

tions as to the standard of review, compare Hampton v.

M ow Sun Wong, supra (because CSC regulation deprived

aliens of a liberty interest, “ some judicial scrutiny o f the

deprivation is mandated by the C onstitu tion” ), 426 U.S.

at 103, with Mathews v. Diaz, 426 U.S. 67, 82, 83 (1976)

(under “ narrow standard of review,” Medicare benefit

restrictions based on alienage were upheld where not

“ wholly irrational”), we see no need to decide which

standard o f review was required here. Even under the

intermediate review used by the district court, we find no

error in the conclusion that the statute furthers important

governmental interests.

The judgm ent o f the district court dismissing the com

plaint is affirmed. No costs.

The statutory test is whether one “owes” allegiance—that is,

whether he is regarded by law as “owing” allegiance to the United

States by virtue of his territorial residence and status. The statutory

test is not whether one “gives” or promises his allegiance to the

United States.

3142

A 1 3

OPINION OF THE DISTRICT COURT

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ----------------------------- -------x

VERONICA YUEN, :

Plaintiff,

vs.

80 Civ. 3177

INTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE et al.,

Defendants.

x

OPINION

Stephen Gleit, New York City, for plaintiff.

John S. Martin, Jr., U.S. Atty., for the

Southern District of New York, Steven E.

Obus, Asst. U.S. Atty., New York City, for

defendants.

SAND, District Judge.

Plaintiff is a permanent resident alien

who claims that she sought and was unlawfully

denied federal employment solely on account

of her alienage."'" Plaintiff first contends

1. Plaintiff is apparently a citizen of

China who came to this country as a student in

1970. (Yuen Aff. p. 8). Her assertion that

she is a lawful permanent resident alien is

not contested by the defendants. (Yuen Aff.

p. 6). The position for which plaintiff

applied is an excepted, i.e., non-Civil Service

position. See discussion, infra. Positions

(footnote continued on next page)

A 1 4

that she "owes allegiance" to the United States

and is therefore eligible for federal employ

ment under 31 U.S.C. § 699b (Supp. 1980), (re

ferred to hereinafter as the "appropriation

act" or "§ 699b"), which, with certain exceptions,

effectively limits federal employment opportu

nities to citizens, aliens from specifically

enumerated countries, and those who "owe

2

(footnote continued)

in the competitive Civil Service are generally

limited to citizens or "nationals" of the

United States. Exec. Order No. 11,935, 5 C.F.R.

§ 7.4 (1974). See also, Jailil v. Campbell,

590 F .2d 1120 (D.C. Cir. 1978); Vergara v.

Hampton, 581 F.2d 1281 (7th Cir. 1978), cert.

denied 441 U.S. 905, 99 S. Ct. 1993, 60 L.Ed.2d

373 (1979); Mow Sun Wong v. Hampton, 435 F.

Supp. 37 (N.D. Calif. 1977); Ramos v. Civil

Service Commission, 430 F. Supp. 422 (D.P.R.

1977) (3 Judge Court).

2. Plaintiff's claim that she "owes allegiance"

to the United States is based solely on her

execution, on June 10, 1980, of the following

affidavit:

I, VERONICA YUEN, do solemnly swear

(or affirm) that I will support defend

the Constitution of the United States

against all enemies, foreign and

domestic; that I will bear true faith

and allegiance to the same. So help

me God.

A 1 5

allegiance" to the Unxted States. Alterna-3

3. The statute, which limits the class of

persons who can be compensated from funds

appropriated by Congress and which is entitled

"Citizenship requirement for federal employees

compensated from appropriated funds" provides

that:

"Unless otherwise specified during the

current fiscal year no part of any appropria

tion shall be used to pay the compensation of

any officer or employee of the Government of

the United States (including any agency the

majority of the stock of which is owned by

the Government of the United States) whose

post of duty is in continental United States

unless such person (1) is a citizen of the

United States, (2) is a person in the service

of the United States on September 29, 1979,

who, being eligible for citizenship, has filed

a declaration of intention to become a citizen

of the United States prior to such date and is

actually residing in the United States, (3) is

a person who owes allegiance to the United

States, (4) is an alien from Cuba, Poland,

South Vietnam, or the Baltic countries lawfully

admitted to the United States for permanent

residence, or (5) South Vietnamese, Cambodian

and Laotian refugees paroled into the United

States between January 1, 1975, and September

29, 1979; Provided, That for the purpose of

this section, an affidavit signed by any such

person shall be considered prima facie evidence

that the requirements of this section with

respect to his status have been complied with.;

Provided further, That any person making a

false affidavit shall be guilty of a felony,

and, upon conviction, shall be fined not more

than $4,000 or imprisoned for not more than one

year, or both; Provided further, That the above

penal-clause shall be in addition to, and not

in substitution for any other provisions of

(footnote continued on next page)

A 1 6

tively, if her status is construed as not

falling within the express terms of that

statute, plaintiff argues that the "distinction

made by the statute between alien [s] eligible

to work and receive compensation and those

alien[s] not eligible to work and receive com

pensation is unconstitutional and deprives

(footnote continued)

existing law; Provided further, That any pay

ment made to any officer or employee contrary

to the provisions of this section shall be re

coverable in action by the Federal Government.

This section shall not apply to citizens of

Israel, the Republic of the Philippines or to

nationals of those countries allied with the

United States in the current defense effort,

or to temporary employment of translators, or

to temporary employment in the field service

(not to exceed sixty days) as a result of

emergencies." 31 U.S.C. § 699b.

Section 699b is from the Treasury, Postal

Service, and General Government Appropriations

Act, 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-74, 93 Stat. 559, 574

(1979). Similar appropriations acts have been

enacted annually since at least 1938 . See,

e .g., Treasury and Post Office Department

Appropriations Act for 1939, Pub. L. No. 75-453,

52 Stat. 120, 148 (1938) .

A 1 7

plaintiff of equal protection of the law."

(Plaintiff's Memorandum of Law In Support of

Issuance of Preliminary Injunction at 2).

At a hearing held on June 10, 1980,

plaintiff's application for preliminary

4injunctive relief was denied. Since there

are no disputed issues of material fact, the

parties have agreed to present the case to the

Court for disposition on the merits on stipula-

5ted facts. After considering a series of

4. Plaintiff commenced this action by com

plaint dated June 4, 1980, alleging that the

Court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§§ 1331 and 1361 and the Fifth Amendment to

the United States Constitution. Simultaneously

with the filing of the complaint plaintiff

sought a preliminary injunction to prohibit

defendants from hiring any person other than

herself for the position in question.

Although the hearing on June 10, 1980 was

not transcribed, the Court summarized its

reasons for denying plaintiff's application at

a subsequent hearing on June 16, 1980. See

Transcript of June 16, 1980 Hearing (hereinafter

"Trans.") at 4-6.

5. The parties also agreed that plaintiff's

affidavit in support of her application for a

preliminary injunction ("Yuen Aff."}, together

with the opposing affidavit of Robert Walker,

Chief, Personnel Branch, North Atlantic Region,

Internal Revenue Service ("Walker Aff."), would

constitute the agreed statement of facts.

A 1 8

briefs submitted by each side,6 the Court

finds that plaintiff is not eligible for

federal employment under the appropriation

act and that the statute does not deprive her

of equal protection of the law. Accordingly,

summary judgment is granted in favor of the

defendants and the complaint is dismissed.

I. The Factual Background

On April 6, 1980, plaintiff, a second

year law student, applied for a position as a

Legal Research Assistant with the New York

City Appeals Office of the Internal Revenue

Service ("IRS"). (Yuen Aff. p. 2). Plaintiff

disclosed her alien status both in her employ

ment application (Standard Form 171) and at

6. In addition to the briefs submitted in

connection with plaintiff's application for

a preliminary injunction, supplemental memo

randa of law were served and filed prior to

the hearing on June 16, 1980. At that time,

the Court requested further briefing on

specific questions, see Trans, at 8-13, and

final briefs were submitted on July 8, 1980.

A 1 9

her employment interview. (Yuen Aff. pp.

6, 8). Apparently, the job description for

the position she sought "did not require

United States citizenship as a condition of

7employment." (Yuen Aff. p . 7).

On May 29, 1980, John Imbesi, Associate

Chief, New York City Appeals Office, telephoned

Ms. Yuen and offered her a position as a Legal

Research Assistant commencing on June 2, 1980.

(Walker Aff. p. 4). Plaintiff was to work

"full time" during the summer and "part-time

during the academic year." (Yuen Aff. p. 10).

After obtaining a release from a prior employ

ment commitment of which defendants were

apparently aware (Yuen Aff. pp. 3, 4), Ms.

Yuen telephoned Imbesi later in the day on 7

7. According to the IRS, Internal Revenue

Manual 13 G 107 (April 7, 1978) contains

guidelines to be followed in hiring law

students as part time Legal Research Assistants.

(Walker Aff. p. 2).

A 2 0

May 29, 1980 and accepted the position.

(Walker Aff. p. 5; Yuen Aff. p. 2). That

same day, after "discovering" that Yuen was

not a United States citizen, Imbesi contacted

IRS Personnel Specialist Carole Butler, who

Oimmediately rescinded the offer. (Walker

Aff. pp. 6, 7). Although the interval of time

between the offer of employment and its with

drawal was thus no more than several hours,

it was long enough for plaintiff to have ob

tained a release from her prior employment

commitment. Plaintiff maintains that she

still desires a Legal Research Assistant's

position with the IRS. (Yuen Aff. p. 9). 8

8. Butler attempted to reach Yuen by telephone

late in the afternoon of May 29, 1980. Al

though she did not reach Yuen directly, Butler

left a message to the effect that "United

States citizenship was required and that she

[Yuen] should not report for work on June

2, 1980." (Walker Aff. p. 7).

We note that the IRS asserts that "[t]he

action of the North-Atlantic Region, Internal

Revenue Service in rescinding the oral offer

of appointment made to Yuen was based upon

the legal proscription against utilizing appro

priated funds to pay non-citizens." (Walker

Aff. p. 8) (emphasis added.) It is clear from

defendant's subsequent assertions, however, both

(footnote continued on next page)

A 2 1

II. The Statutory Issue

A. Preliminary Considerations

Plaintiff contends that an oath of

allegiance which she executed in affidavit

form on June 10, 1980 makes her eligible for

federal employment under the "owes allegiance"

9provision of § 699b(5). Plaintiff also

points specifically to the clause in that

statute which provides that "for the purpose

of this section, an affidavit signed by any

such person shall be considered prima facie

evidence that the requirements of this section

with respect to his status have been complied

with . . . Id. On the other hand, the

government contends that Congress' intent

when it first enacted the "owes allegiance"

provision in 1938 was to exempt non-citizen

"nationals", i.e., inhabitants of United *

(footnote continued)

at oral argument and in various briefs, that

IRS's actual position is that the offer was

rescinded because plaintiff is not encompassed

within any of the categories of eligible em

ployees contained in the appropriation act.

See note 3, supra.

9. See notes 2 and 3, supra.

A 2 2

States possessions such as Puerto Rico or the

Philippines, from a newly imposed citizenship

requirement,10 rather than to open federal

employment to any alien willing to take an

oath. The government claims that at the

present time, the only non-citizens who owe

allegiance to the United States in the sense

that that phrase is used in the statute are

inhabitants of American Samoa. Before

reaching these primary statutory contentions,

there are two preliminary matters which must

first be addressed: the first relates to the

timing of plaintiff's oath of allegiance; the

second concerns plaintiff's contention that

the statutory issue in this case has already

been resolved by the United States Supreme

decision

Court's/ in Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, 426 U.S.

88, 96 S. Ct. 1895, 48 L.Ed.2d 495 (1976)

(Hampton I.)

10. See discussion infra. A citizenship

requirement had long been imposed by the Civil

Service Commission. See Hampton v. Mow Sun

Wong, 426 U.S. 88, 105, 110-111, 96 S. Ct.

1895, 1906, 1908-1909, 48 L.Ed.2d 495 (1976).

A 2 3

Plaintiff applied for federal employment

on April 6, 1980 and was offered, accepted

and ultimately denied a Legal Research Assist

ant's position on May 29, 1980. Since her

oath of allegiance, on which she relies ex-

11clusively to establish her statutory claim,

was executed on June 10, 1980, Ms. Yuen

apparently did not "owe allegiance" to the

United States in the sense that she uses the

phrase either at the time of her application

or at the time the offer was made, accepted,

and withdrawn. It is thus arguable, although

the government has not raised this issue, that

plaintiff's statutory claim is non-justiciable

because she could not prevail even if her in- 11

11. Plaintiff puts forth no other ground on

which to base her claim of allegiance. More

over, it is clear that neither the duration

nor the nature of her residence in the United

States will satisfy the "owes allegiance"

requirement. See Oliver v. United States De

partment of Justice, Immigration and Naturali

zation Service, 517 F.2d 426 (_2d Cir. 1975),

cert. denied,~~42 3 U.S. 1056, 96 S.Ct. 789, 46

L.Ed.2d 646 (1976) .

A 2 4

terpretation of the statute is correct.

While the Court has raised this question

on its own initiative, we decline to reach such

a result. Despite IRS's assertion that it

"stands ready" to hire plaintiff if she should

prevail in this litigation (Walker Aff. p. 9;

Trans, at 15), the Service has persisted in

its refusal to hire Ms. Yuen even after her

execution of an oath of allegiance. Obviously,

the government disputes plaintiff's interpreta

tion of the statutory phrase "owes allegiance";

just as obviously, Ms. Yuen, as a result of

that dispute, is being denied a position which

would otherwise be hers. We turn next to

plaintiff's argument concerning the significance

of Hampton I to the statutory issue in this case.

In Hampton I, the Supreme Court held that

a Civil Service Commission ("CSC") regulation

which excluded all aliens from competitive

12Civil Service employment and which was not 12

12. The CSC regulation at issue in Hampton I,

5 C .F .R. § 338.101 (1976), provided in per-

tinpnt narf- •F '(footnote continued on next page)

A 2 5

mandated by either Congress or the President

deprived aliens of liberty without due process

13of law. Addressing the question whether the

(footnote continued)

"(a) A person may be admitted to com

petitive examination only if he is a

citizen of or owes permanent allegiance

to the United States.

"(b) A person may be given appointment

only if he is a citizen of or owes

permanent allegiance to the United

States. However, a noncitizen may

be given (1) a limited executive

assignment under section 305.509 of

this chapter in the absence of qualified

citizens or (2) an appointment in rare

cases under section 316.601 of this

chapter, unless the appointment is pro

hibited by statute."

Under the CSC' s interpretation of the regula

tion, except for the specific exceptions under

§ 338.101(b)(1) and (2), only citizens and

residents of American Samoa were qualified.

See Hampton I, at 90 n.l, 96 S. Ct. at 1899.

13. The Court first assumed "without deciding

that the national interests identified by the

. . . [government] would adequately support an

explicit determination by Congress or the Presi

dent to exclude all noncitizens from the federal

service." 426 U.S. at 116, 96 S. Ct. at 1911.

It then concluded, however, that because the

"only concern of the [CSC] is the promotion of

an efficient federal service . . .," the

Commission, unlike Congress or the President,

see discussion infra, could put forth no

interest other than efficiency in support of a

citizenship requirement. Id. at 114-115, 96

S. Ct. at 1910. Since the Court found no

(footnote continued on next page)

A 2 6

CSC regulation at issue was mandated by

Congress, the Court examined, inter alia, the

citizenship requirements contained in Appro

priation Acts similar to the one currently

14before us. Id. 426 U.S. at 108-109, 96

S. Ct. at 1907-1908. The Court found that

" . . . Congress has consistently

authorized payment to a much broader

class of potential employees than

the narrow category of citizens and

natives of American Samoa eligible

under the Commission rule. Congress

has regularly provided for compensa

tion of any federal employee owing

(footnote continued)

evidence that the regulation at issue resulted

from a "considered evaluation of the relative

desirability [from the standpoint of efficiency]

of a simple exclusionary rule on the one hand,

or the value to the service of enlarging the

pool of eligible employees on the other," it

held that the CSC's efficiency interest could

not support the rule. Id. Finally, the Court

noted that

"[a]ny fair balancing of the public

interest in avoiding the wholesale

deprivation of employment opportunities

caused by the Commission's indiscrim

inate policy, as opposed to what may be

nothing more than a hypothetical justi

fication, requires rejection of the

argument of administrative convenience

in this case." Id. at 115-116, 96 S.

Ct. at 1911. (Footnote omitted).

14. See note 3, supra.

All

allegiance to the United States.

Since it is settled that aliens

may take an appropriate oath of

allegiance, the statutory category,

though not precisely defined, is

plainly more flexible and expansive

than the Commission rule." Id. at

109, 96 S. Ct. at 1908. (Footnote

omitted).

Plaintiff relies on this passage from

Hampton I to argue that "the Supreme Court

necessarily decided that the phrase 'a per

son who owes allegiance to the United States'

in the appropriations act may include an

alien" and that the principles of stare de

cisis bar a reconsideration of that issue by

this Court. (Plaintiff's Response To Defen

dant's Memorandum of Law at 6; Plaintiff's

Further Memorandum of Law at 5-7). The govern

ment characterizes this portion of Hampton I

as "dictum" and contends that in Hampton I the

Court "was not squarely presented with any

issue requiring interpretation of the 'owes

allegiance' provision of any federal appro

priations act." (Memorandum of Law In Oppo

sition to Plaintiff's Motion For A Preliminary

A 2 8

Injunction at 15; Defendants' Supplemental

Memorandum at 16-17) .

Plaintiff's contention is not without

initial appeal. Although the Court's sugges

tion that aliens are eligible for employment

under the appropriations acts because they can

take an oath of allegiance is technically

dictum, Hampton I referred specifically to

the "owes allegiance" provision and its impact

on aliens to support its conclusion that the

class eligible under those acts is more

expansive than the class eligible under the

CSC rule. This conclusion, moreover, was

central to the Court's finding that the rule

was not mandated by Congress, which was in turn

central to the Court's holding that the rule

violated due process. Nevertheless, we reject

the contention that Hampton I "necessarily

decided" the meaning of "owes allegiance" in

this context, and conclude that Hampton I does

nbt foreclose an analysis of that question by

this Court,

A 2 9

As the government correctly points out,

the Hampton I Court was not "squarely presented"

with any issue requiring interpretation of the

"owes allegiance" provision. The passage

relied on by plaintiff was undoubtedly an

important "building block" in the Court's

reasoning, but the essential part of that

passage is the finding that:

" . . . Congress has consistently

authorized payment to a much broader

class of potential employees than the

narrow category of citizens and

natives of American Samoa eligible under

the Commission rule."

426 U.S. at 109, 96 S. Ct. at 1908.

The Court's passing reference to the apparent

plain meaning of the "owes allegiance" pro

vision, however, was not essential to the

conclusion that the CSC rule was not mandated 15

15. Although the Court made some references

to the legislative history of the appropriation

acts, see 426 U.S. at 108, 96 S. Ct. at 1907,

no detailed analysis of the purposes and

origins of either the "owes allegiance" pro

vision or the affidavit provision, see text

accompanying notes 9-10 supra, appears to

have been undertaken by the Court or the

parties. See the following briefs in Hampton I:

Brief For the Petitioners at 83-84; Brief For

the Respondents; Reply Brief For the Petitioners.

A 3 0

by Congress. Even if an oath alone cannot

qualify aliens for federal employment under

the appropriation acts, "the statutory cate

gory . . . is [still] plainly more flexible

and expansive than the Commission rule."16

Finally, to conclude that Congress meant

something other than an oath of allegiance

when it used the phrase "owes allegiance" is

not to deny that "aliens may take an appro

priate oath of allegiance . . . ."Id.,

citing In re Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717, 93 S.Ct.

2851, 37 L .Ed.2d 910 (1973).

We thus proceed with our analysis of the

language and legislative history of the

relevant appropriation acts.

B . The Statutory Language

On its face, § 699b appears to support

plaintiff's position. Plaintiff has signed

an affidavit stating that she "will bear

true faith and allegiance to" the Constitu-

16. Compare 31 U.S.C. § 699b (note 3 supra)

with 5 C.F.R. § 338.101 (note 12 supra).

A 3 1

txon of the United States. Since the

statute provides that "an affidavit signed

by [a person seeking federal employment] . . .

shall be considered prima facie evidence that

the requirements of this section with respect

to [her] status have been complied with; . .

the burden would appear to be on the govern

ment to prove that plaintiff's affidavit is