Motion to Sever

Public Court Documents

January 14, 1986

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Motion to Sever, 1986. ad5248bf-b8d8-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/eda12d5a-5806-4092-adb9-a7084e1bfe65/motion-to-sever. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

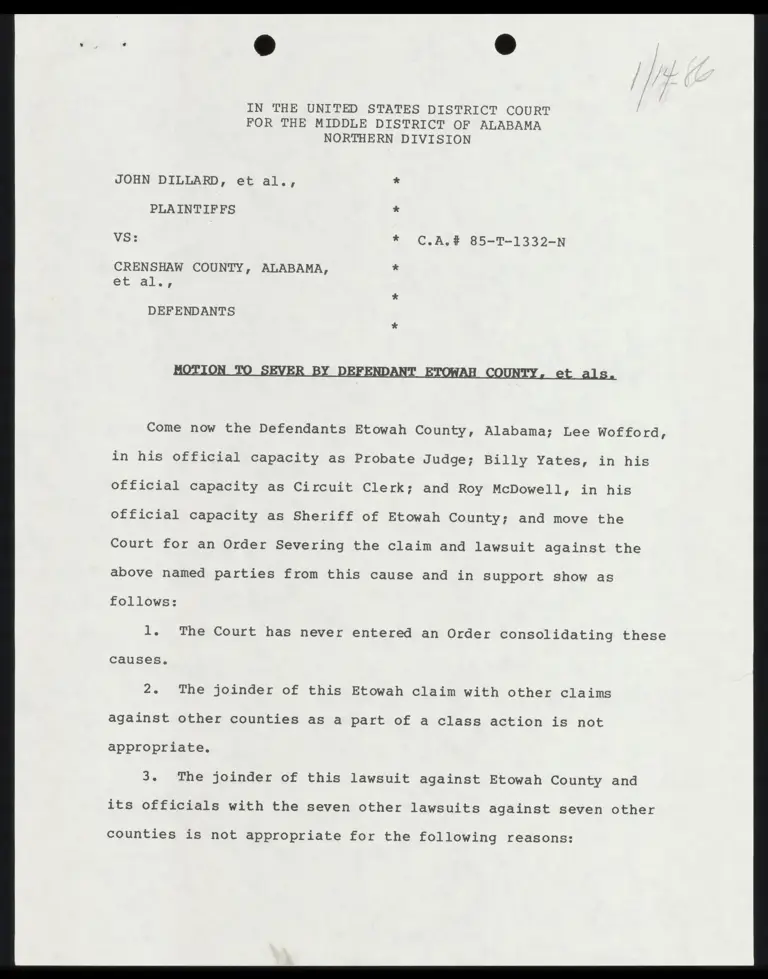

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

JOHN DILLARD, et al., *

PLAINTIFFS *

VS: * C.A.# 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA, *

et al,.,

*

DEFENDANTS

Come now the Defendants Etowah County, Alabama; Lee Wofford,

in his official capacity as Probate Judge; Billy Yates, in his

official capacity as Circuit Clerk; and Roy McDowell, in his

official capacity as Sheriff of Etowah County; and move the

Court for an Order Severing the claim and lawsuit against the

above named parties from this cause and in support show as

follows:

l. The Court has never entered an Order consolidating these

causes.

2, The joinder of this Etowah claim with other claims

against other counties as a part of a class action is not

appropriate,

3. The joinder of this lawsuit against Etowah County and

its officials with the seven other lawsuits against seven other

counties is not appropriate for the following reasons:

a. There are eight different and distinct liability

issues.

b. Each of the eight cases are diverse.

c. There is no basic commonalty because of remedy in the

eight cases.

d. The officials in the different counties are elected by

diverse and different election laws.

e. Each County named has different numbers of

commissioners, elected in different manners, with different

responsibilities.

f. The terms of the commissioners in various counties are

different.

gd. The counties named as defendants have different black

white population ratios. (In the case of Etowah, 13.8 per cent

black).

4. The factual situation with regards to each individual

cause and county is different and the consolidation of then,

creating an illusion of similarility, work to the prejudice of

these Defendants.

5. That if this cause is allowed to proceed as a

consolidated cause, then the Court would be required to conduct

eight separate and distinct trials on eight detailed separate

constitutional issues. Etowah County and its elected officials

should not be required or placed in a position of having to sit

in court while seven other separate and distinct claims and

lawsuits are tried.

6. Each county, each lawsuit, has different questions of

fact and law. There are no common questions of law and Fact,

and as such, said action is not suitable for a joint action of

as a class action.

7. In this litigation there are eight separate lawsuits

that must be looked at on a separate factual basis.

8. Etowah County is in the United States District Court for

the Northern District of Alabama. The forum in the United

States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama is

inconvenient for Etowah County to defend an action against it.

Difficulty of transporting parties, witnesses, and attorneys out

of its own district to another to prepare, present and complete

a trial mandates that this action be severed from the other

seven lawsuits and be transferred to the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Alabama.

FLOYD, KEENER & CUSIMANO

ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANTS

Etowah County, Alabama;

Lee Wofford; Billy Yates

and Roy McDowell

JACK FLOYD

816 Chestnut Street

Gadsden, AL 35999-2701

(205) 547-6328

I hereby certify that a copy of the foregoing has been

mailed to Larry. T. Menefee, Attorney, P. O. Box 1051, Mobile,

Alabama 36633; Terry G. Davis, P. O. Box 6215, Montgomery,

Alabama 36104; Deborah Fins, Julius L. Chambers, 99 Hudson

Street, 16th Floor, New York, New York 10013; Edward Still, 714;

South 29th Street, Birmingham, AL 35233; and Reo Kirkland, Jr.,

P. O. Box 646, Brewton, AL 36427, Alton Turner, Crenshaw County

Attorney, P. O. Box 207, Luverne, AL 36049, Dave Martin,

Lawrence County Attorney, 215 S. Main Street, Moutlon, AL 35650,

Warner Rowe, Coffee County Attorney, 119 East College Avenue,

Enterprise, AL 36330, H. R. Burnham, Calhoun County Attorney, P.

O. Box 1618, Anniston, AL 36202, Barry D. Vaughn, Talladega

County Attorney, 121 N. Norton Avenue, Sylacauga, AL 35150, Lee

Otts, Escambia County Attorney, P. O. Box 467, Brewton, AL

36427, Buddy Kirk, Pickens ty Soma, P. O. Drawer AB,

Carrollton, AL 35447, this the _\day of January, 1986.

LO UA

TS —

OF COUNSEL