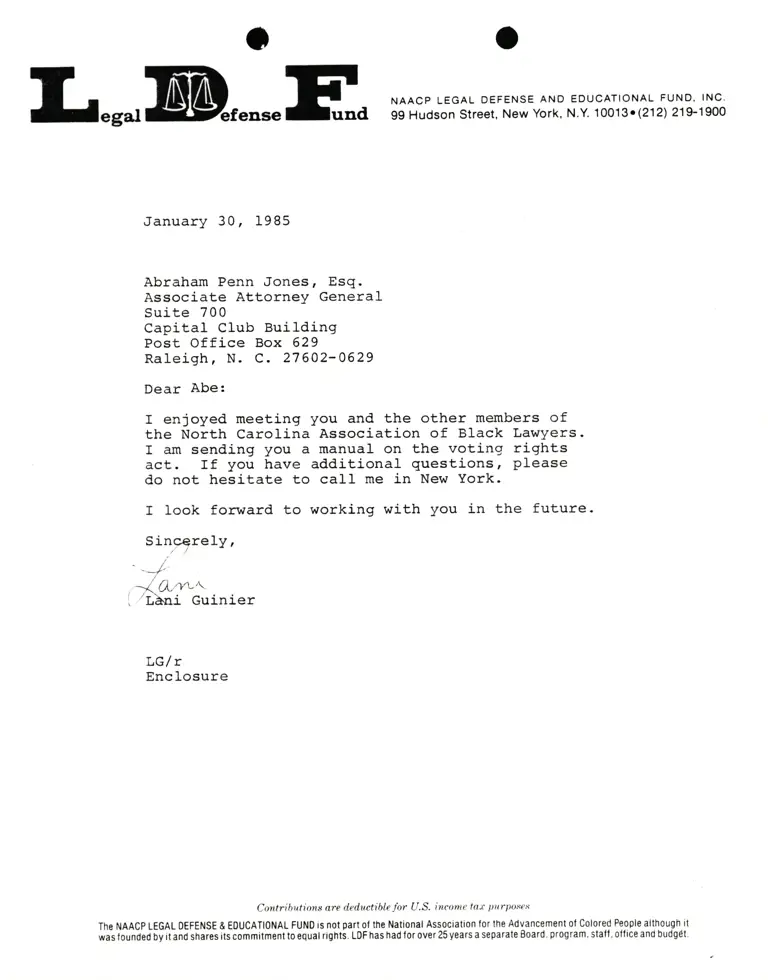

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Abraham Penn Jones, Esq. (Associate Attorney General)

Correspondence

January 30, 1985

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Abraham Penn Jones, Esq. (Associate Attorney General), 1985. 1f3fe45b-e892-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/edad36ae-323f-4c5a-8559-e1aa91cb6011/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-abraham-penn-jones-esq-associate-attorney-general. Accessed February 18, 2026.

Copied!

Lesar@renseH"

January 30, 1985

Abraham Penn Jones, Esg.

Associate Attorney General

Suite 700

Capital Club Building

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, N. C. 27602-0629

Dear Abe:

I enjoyed meeting you and the other members of

the North Carolina Association of Black Lawyers.

I am sending you a manual on the voting rights

act. If you have additional questions, please

do not hesitate to call me in New York.

I look forward to working with you in the future-

Sincerely,

'-J'-

1&ryt-x

, 'Lbni Gui.nier

LGl r

Enclosure

Contribntions are deductible lor U.S. irtcortle lor prrrf)oscr-

The NAACp LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND is not part of the National Association for the Advancement of colore.d People although it

"al

fornOeO OV it and shares its commitment to oqual rights. LoF has had lor over 25 years a separate 8oard. program, stalf, oltice and budgdt.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND' INC.

99 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. '10013o (212\ 21S1900