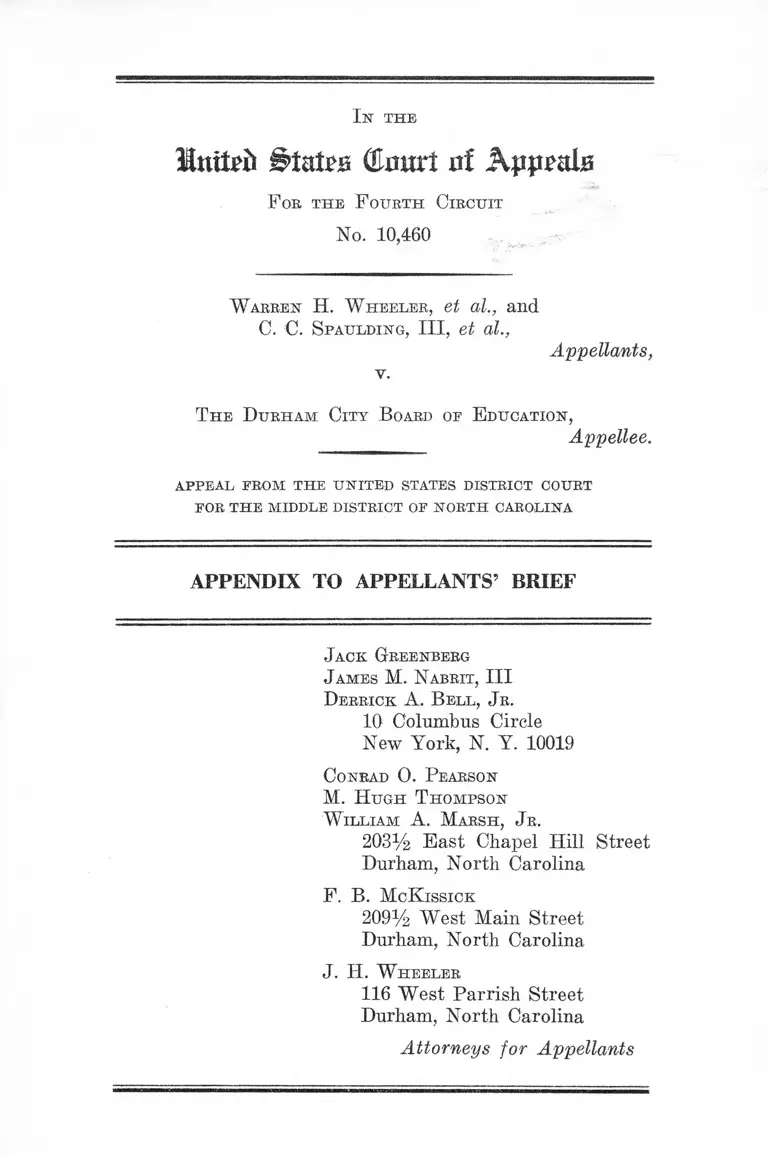

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education Appendix to Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

July 6, 1965 - January 25, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education Appendix to Appellants' Brief, 1965. ac4eb1f8-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/edbea3a2-b247-49aa-8b31-e9a19b917b60/wheeler-v-durham-city-board-of-education-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed February 18, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

MnxUb ^tatrs Court of Appeals

F or the F ourth Circuit

No. 10,460

W arren H. W heeler, et al., and

C. C. Spaulding, III, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

T he Durham City B oard oe E ducation,

Appellee.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR TH E MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Derrick A. B ell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Conrad O. Pearson

M. H ugh T hompson

W illiam A. Marsh, Jr.

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

F. B. McK issick

209% West Main Street

Durham, North Carolina

J. H. W heeler

116 West Parrish Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-11 ....... 5a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-12 ......... 15a

Answer of Defendant to Interrogatories Submitted

by Plaintiffs on September 3, 1965 ....... 17a

Exhibit 2-B Attached as Answer to Interroga

tories ............................... 20a

Exhibit 2-C Attached as Answer to Interroga

tories ..................................................................... 21a

Exhibit 2-D Attached as Answer to Interroga

tories ................................ 23a

Exhibit 2-E Attached as Answer to Interroga

tories ..................................................................... 24a

Relevant Docket Entries ................................................. la

Exhibit 4 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories 25a

Exhibit 5 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories 26a

Exhibit 6 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories 27a

Exhibit 8 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories 28a

Exhibit 9 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories 30a

Exhibit 10 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories 31a

Exhibit 11 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories 32a

Deposition of George Reid Parks ............................. 33a

Deposition of Annie Laurie Bugg ............................. 52a

Deposition of Dr. Theodore R. Speigner ................. 64a

Deposition of Lew W. Hannen .................. 75a

Excerpts from Transcript of Hearing dated Septem

ber 23-24, 1965 .................... ...... ........ .......... ............ . 98a

Memorandum and Order Denying Intervention ....... 298a

Plan for Desegregation of the Durham City Schools .. 302a

Plaintiffs’ Response to Defendant’s Permanent Plan

of Desegregation .......... ................................... ......... 315a

Plaintiffs’ Supplemental Response .................... ......... 318a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Opinion .... 321a

Order ............... 341a

Testimony

Plaintiffs’ Witnesses :

Myrl G. Herman—

Direct ............... 98a

Cross ............................................ 114a

Redirect ................ ........... ........................131a, 140a

Reeross ...... ....................................................... 138a

Dr. Joseph S. Himes—

Direct ____ __ _____ ________ ____ _______ __ 146a

Cross ............... 166a

Redirect ____ ____________ __________ _____ 191a

Dr. Joseph P. McKelpin—

Direct .......... ....... ...... ......... ........... ........... ...... 193a

Cross .......... ....................................................... 201a

Howard M. Fitts, Jr.—

Direct ............................................... ......... ..... . 211a

Cross ........................ ...... .................... ............. 220a

11

PAGE

PAGE

iii

Lew W. Hannen—

Direct ................................................................ 222a

Cross ......................................... 273a

Redirect ....................... 283a

Recross .................. ........................................... 285a

Elliott B. Palmer—

Direct .................................. 286a

Cross ................................................................. 292a

E xh ibits

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits:

Offered Printed

Page Page

65-1—Documents....................................._. 223a. *

65-2—Documents....................................... 224a 294a

65-3—Document ............................ 225a *

65-4—Document ............................ 225a *

65-5—Document ____ 226a *

65-6—Document ..... 227a #

65-7—Document ..... 227a *

65-8—Document ...... 228a *

65-9—Document ................ 231a 296a

65-10—Document ................... 236a *

65-11—Document ........... ......... ....... . 247a 5a

65-12—Document ....... 248a 15a

65-13—Deposition ________ ___________ 249a 33a

65-14—Deposition _______ 24-9a 52a

65-15—Deposition ___ 249a 64a

65-16—Deposition ...... 249a 75a

65-17 for Identification—Documents ..... 260a, #

Omitted.

Relevant Docket Entries

# # # # *

7- 6-65 R ecord on A ppeal—received back from Court

of Appeals the record, transcript of testi

mony, and Exhibits. Receipt acknowledged to

Court of Appeals.

7-16-65 Consent Order—as to reassignment of pupils

for the 1965-66 school years, signed by Judge

Stanley on 7-16-65.

7-22-65 Conference— with attorneys held before Judge

Stanley in Durham. By 9-1-65 ptf. to submit

their Memorandum of Law with respect to

their request for a permanent plan for elimi

nation of discrimination. Deft, has until

9-15-65 to respond. By 9-9-65 deft, to submit

to ptf. the results of the study of the deft.

Board with respect to employment and as

signment of teachers and other personnel

without regard to race or color; and a state

ment with respect to its proposed capital im

provement program for year ending 6-30-66.

If ptf. objects to any proposed capital im

provements, objections to be filed by 9-21-65.

H earing Set f o r — 23 September 1965 at 10:00

a.m. in Durham. Following hearing, the Court

will take under advisement matters still in

dispute.

9-13-65 R eport— by defendants on Proposed Construc

tion and Enlargement of the School Building

Facilities of Durham City Schools.

2a

9-13-65

9-20-65

9-20-65

9-20-65

9-23-65

9-28-65

Repoet—by defendants of Committee Studying

employment and Assignment of Professional

Personnel.

* * * # *

Motion to Intervene or in the Alternative

for Leave to Be Added as a Party-Plaintiff

—by applicant North Carolina Teachers As

soc. C/S attached.

Complaint in Intervention—received, but NOT

filed; not to be filed unless court grants mo

tion to intervene on N. C. Teachers Assoc.

Motion—of plaintiff’s that the court consider

the claim of intervenor upon the same evi

dence to be introduced by original plaintiffs

in the hearing on 9-23-65.

* # # « *

Hearing—in this action & C-11.6-D-60, before

Judge Stanley in Durham in accordance with

memo entered 7-22-65 (filed 7-29) and pend

ing motion to Intervene by N.C. Teachers

Assoc. Oral arguments heard;

Motion to Intervene Denied.—Following wit

nesses sworn and testified for plaintiff:

Myrl G. Heiunan—Rhode Island.

Joseph S. Hines—N. C. College.

Joseph P. McKelpin—N. C. College.

# # # « = *

Memorandum & Order—of Judge Stanley en

tered as of Sept. 23, 1965, denying motion to

Intervene of N. C. Teachers Assoc.

Relevant Docket Entries

3a

Relevant Docket Entries

9-28-65 Memorandum & Order—of Judge Stanley au

thorizing the Durham City School Board to

proceed with the acquisition of school sites,

renovation, etc. according to its report dated

8-20-65, etc.

Copies of Orders mailed to attnys. by Judge.

# # # # #

10-15-65 Deft’s Plan for Desegregation—of Durham

schools, with cert, of svc.

10- 25-65 Ptf’s Response to Deft’s Permanent Plan of

Desegregation—with cert, of service.

# # * # *

11- 26-65 Supplemental Response—of plaintiff to defen

dant’s permanent plan of desegregation and

opposition to defendant’s proposed order ap

proving the plan. W/Cert./Service.

# # * # #

1-19-66 Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and

Opinion—of Judge Stanley dated January 19,

1966.

1-19-66 Order—of Judge Stanley adjudging that:

1. That the “Permanent Plan for Desegrega

tion of Durham City Schools” filed on Oct.

25, 1965, is approved in all respects, said

plan to remain in effect until such time as

the deft. Board shall present, and be

adopted by the Court, some other plan

for the enrollment and assignment of

pupils.

4a

2. That the application of ptfs. for an order

requiring the employment and assignment

of teachers without regard to race is de

nied.

3. All previous injunctions issued by the

Court shall continue in effect.

4. Jurisdiction of these causes be retained

for the entry of such orders as are neces

sary and proper.

# # # # #

1-25-66 Notice or A ppeal—of the plaintiff’s from order

entered in the U.S. District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina 19 Jan

uary 1966, with $5.00 filing fee. C/S attached.

Relevant Docket Entries

5a

2710 Stuart Drive

Durham, North Carolina

August 20, 1965

Mr. Herman A. Rhinehart, Chairman

Durham City Board of Education

Durham, North Carolina

Re: Report of Committee Studying Employment and

Assignment of Professional Personnel

Dear Mr. Rhinehart:

This report is made pursuant to Paragraph 9 of the Court

Order issued August 3, 1964 by District Judge Edwin M.

Stanley, United States District Court for the Middle Dis

trict of North Carolina, Durham Division, Case Numbers

C-54-D-60 and C-116-D-60, which provides:

“ That consideration of the request for injunctive relief

with respect to the hiring and placement of teachers

and other professional personnel in the Durham City

School System is deferred until after the close of the

1964-65 school term. In the meantime, the defendant

Board is required to make a detailed study of the ad

ministrative and other problems involved. If the plain

tiffs still desire to pursue this relief, they may make

a further application to the court at any time after

the end of the 1964-65 school term, at which time both

the plaintiffs and the defendant shall be prepared to

express themselves fully with reference to all admin

istrative and legal problems involved, including, but

not limited to, the standing of the minor plaintiffs to

question the policy employed by the defendant Board

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-11

6a

in the hiring and placement of teachers and other

professional personnel and how the minor plaintiffs

are injured or otherwise affected by such policy.”

As directed by the Court, this committee was appointed to

make the study.

At a meeting on February 5, 1965, the committee discussed

at length the information required for proper evaluation

of this problem. The conclusions reached were:

1. To enlarge the information requested on the applica

tion for position form in order to provide additional

information to assist in upgrading the teaching staff

of our schools.

2. (a) To provide a summary of The National Teacher

Examination scores of all teachers who had taken

the examination.

(b) To determine the number of teachers who have

not taken the examination.

3. To send a questionnaire to all members of the present

teaching staff. A copy of the form is attached.

4. To request presently employed teachers who have not

taken The National Teacher Examination to take both

the Common Examination (designed to provide a gen

eral appraisal of basic professional preparation, gen

eral academic attainment and certain mental abilities)

and the Optional Examination (designed to aid in

evaluating the teacher’s preparation to teach in his

chosen field) and require the Optional Examination.

Cost of the examinations will be paid by the Durham

. City Schools.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-11

7a

The committee felt that the information obtained from

the Optional Examination scores would be of great

value to the teachers and the school administration

in determining the areas of strengths and weaknesses

and would provide a sound basis for guidance for

improvements in the areas of weaknesses.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-11

The Superintendent was asked to provide the information

requested by the committee.

On April 9, 1965, Mr. H. A. Bhinehart, Chairman of the

Board, and Mr. Lew W. Hannen, Superintendent, met with

representatives of the classroom teachers and discussed

with them Item 4 above. A copy of the report on that meet

ing is attached.

On June 18, 1965, the committee met to consider informa

tion provided by the Superintendent.

1. Only minor changes were made in the Application for

Position form. A copy of the old form and a copy

of the new form are marked “ Old” and “New” and

attached hereto.

2. (a) Teacher Examination scores are on file for 81

teachers.

Number of Teachers

Teacher scores from 300-399

White

0

Negro

3

400-449 0 0

450-499 1 3

500-599 17 5

600-699 29 0

700-799 21 0

800-899 2 0

8a

The requirement of a score of 450 for certification

of new teachers in North Carolina has been in

effect since July 1, 1961. At a regular School

Board meeting on April 3, 1964, the Board

adopted a resolution requiring a score of 500 for

all new teachers in the city schools as far as ad

ministratively possible. All teachers certified by

the North Carolina State Department of Public

Instruction on or after July 1, 1961, who were

employed by the Durham City Schools for the

school years 1964-65 and 1965-66 had a teacher’s

examination score of 500 or more.

(b) The National Teacher Examination has not been

taken by 571 teachers in the Durham City Schools.

3. The results of the questionnaire filled out by the pro

fessional personnel are summarized on a copy of the

form and attached hereto.

The committee considered the desirability of ascertaining

the attitude of parents toward the integregation of pro

fessional personnel. We concluded it would be difficult to

develop factual information in this area. A considerable

number of white parents, however, has expressed to mem

bers of the Board their dislike of having their children

under Negro teachers. Some will reluctantly accept them,

and others will resist them, even to the extent of trans

ferring their children to other schools. During the past

two years of complete freedom of choice for reassignments,

the following developments are enlightening and we think

should be considered.

1. No parent of a white child has requested assignment

to a predominantly Negro school.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-11

9a

2. Although, the Board has assigned a number of white

children to predominantly Negro schools, in every

instance reassignment has, been requested to a pre

dominantly white school.

3. A number of Negro children has also indicated a

preference for predominantly Negro school by re

questing reassignments from predominantly white

schools.

4. An analysis of the 531 requests for reassignments for

the school year 1964-65 reflects the following:

(a) 201 requests for reassignment from predomi

nantly Negro to predominantly white schools.

(Most of these were for Negro pupils, but an

undertermined number of white pupils was in

cluded in this group.)

(b) 108 requests for reassignment from predomi

nantly white to predominantly Negro schools.

(All of these were for Negro pupils.)

(c) 91 requests for reassignment from predominantly

Negro to other predominantly Negro schools.

(All of these were for Negro pupils.)

(d) 131 requests from predominantly white to other

predominantly white schools. (The majority of

these requests was from white pupils, but this

also included an undetermined number of Negro

pupils.)

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-11

10a

RECOMMENDATIONS AND OBSERVATIONS

1. It is recommended that the Durham City Board of

Education continue the policy adopted at its regular

meeting on April 3, 1964, requiring a National Teachers

Examination score of 500 for all new teachers employed

in the city schools as far as administratively possible.

2. In considering the facts previously outlined, we are led

to the following conclusions:

a. For the school year 1964-65 the Board of Education

made the assignment of pupils to the various schools,

after which all pupils had the privilege of request

ing reassignment to the school of their choice. All

the requests for reassignment were granted. With

complete freedom of choice all the white pupils at

tended the predominantly wdiite schools and approxi

mately 94% of the Negro pupils attended the pre

dominantly Negro schools. This gives substantial

strength to the present policy of teacher assignment.

b. The questionnaire sent to the teachers were returned

by 93.7% of them. The results, tabulated on a first

preference basis, are self-explanatory and have a

high degree of correlation with pupil preference

above.

c. The present policies of the Board with respect to

employment and assignment of teachers and other

personnel have provided our school system with an

effective program of education for all the pupils of

our schools. The committee recommends that we

continue our present policies, but that the Board in

the employment and assignment of teachers and

other personnel by majority vote of its members

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-11

11a

make exceptions to any of its policies for valid and

sound educational reasons.

3. The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools has

recently approved for accreditation all of the elementary

and high schools in the Durham City System. Accredi

tation has been recommended by the Accreditation Com

mittee for all the Junior High Schools except two.

Shepard Junior High School is not eligible for consid

eration because it is a new school. It is anticipated that

accreditation of this school will be achieved next year.

Accreditation for Holton Junior High School was de

ferred pending removal of outstanding deficiencies. It

is anticipated that the deficiencies will be removed dur

ing the 1965-66 school year, and full accreditation will

be granted. Many of the accreditation reports referred

to the good rapport between teacher and student and

an atmosphere conducive to learning. It is with a great

deal of pride that we commend our administrators and

teachers for this achievement. Obviously, none of our

pupils have been injured because of our Teacher Place

ment Policy.

4. Desegregation has been achieved and will be continued

in the areas indicated below:

a. Supervisors, Principals, and Teachers’ meetings

b. Workshops and In-service training courses

c. Grade level meetings

d. Subject area meetings including all special subject

meetings

e. Supervisory staff work

Respectfully submitted,

George R. Parks, Chairman

Mrs. Annie Laurie Bugg

Dr. Theodore R. Speigner

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-11

12a

SUMMARY OF QUESTIONNAIRE FILLED OUT

BY PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF DURHAM

In compliance with an Order of His Honor, Edwin M.

Stanley, a Committee of the Board has been giving careful

consideration and study to the hiring and placement of

teachers and other professional personnel in the Durham

City School System. For the purpose of assisting the Com

mittee in its study, the Board most respectfully requests

that each teacher answer the questions set out below.

What preferences do you have regarding your qualifica

tions and willingness to teach in the following situations?

(Enumerate your preference 1, 2, 3, etc.)

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-11

WHITE TEACHERS

I am qualified to teach: I am willing to teach

20 1. Integrated classes 29

16 2. Predominantly negro classes 4

180 3. Predominantly white classes 213

54 4. Any of the above equally 24 \ ^

53 5. No preference stated 53

Given a choice:

323 Total 323 Total

I am best qualified to teach: I am willing to teach

0 1. Retarded pupils (up to 70 I. Q.) 1

0 2. Slow pupils (70-90 I. Q.) 2

104 3. Average pupils (90UL10 I. Q.) 97

68 4. Advanced pupils (110-130 I. Q.) 71

18 5. Talented pupils (130-f- I. Q.) 17

36 6. Random grouping of pupils 34

3 7. Any homogeneous grouping 9

11 8. Any of the above equally well 14

83 No preference stated 78

13a

In what public school did you teach during the 1964-65

school year?

.... 323 Total .... 323 Total

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-11

Date:

Signature (optional)

Please deliver the completed blank in the accompanying

envelope to your principal who will return it to the Super

intendent.

SUMMARY OF QUESTIONNAIRE FILLED OUT

BY PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF DURHAM

In compliance with an Order of His Honor, Edwin M.

Stanley, a Committee of the Board has been giving careful

consideration and study to the hiring and placement of

teachers and other professional personnel in the Durham

City School System. For the purpose of assisting the Com

mittee in its study, the Board most respectfully requests

that each teacher answer the questions set out below.

What preferences do you have regarding your qualifica

tions and willingness to teach in the following situations?

(Enumerate your preference 1, 2, 3, etc.)

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-11

NEGRO TEACHERS

I am qualified to teach: I am willing to teach:

40 1. Integrated classes 48

21 2. Predominantly negro classes 50

0 3. Predominantly white classes 1

206 4. Any of the above equally 160 f l

21 5. No preference stated 29

Given a choice:

288 T otal 288 T otal

I am best qualified to teach: I am willing to teach:

3 1. Retarded pupils (up to 70 I. Q.) 5

2 2. Slow pupils (70-90 I. Q.) 9

107 3. Average pupils (90-110 I. Q.) 97

21 4. Advanced pupils (110-130 I. Q.) 24

3 5. Talented pupils (130+ I. Q.) 4

26 6. Random grouping of pupils 17

13 7. Any homogeneous grouping 65

65 8. Any of the above equally well 43

48 9. No preference stated

In what public school did you teach during the 1964-65

school year?

.... 288 Total 288 Total

Signature (optional)

Date:

Please deliver the completed blank in the accompanying

envelope to your principal who will return it to the Super

intendent.

15a

A MINORITY REPORT

PRESENTED TO THE SUB-COMMITTEE ON THE

DESEGREGATION OF THE TEACHING PERSONNEL

AND STAFF OF THE DURHAM CITY BOARD

OF EDUCATION

Me. Chairman:

I wish to make the following recommendation:

1. That the City Board of Education should authorize

the superintendent of Durham City Schools to employ

qualified and competent persons for all positions and

jobs, regardless of race, color, or national origin.

A. To implement this resolution and to make for the

widest possible desegregation of teachers, staff,

and students the following principles should be

enacted by the Board immediately:

1) That all supervisors of instruction be assigned

to serve all city schools, regardless of race,

2) That all special subject teachers be assigned to

schools, regardless of race or color.

3) That assignment of teachers for the 1965-66

academic term shall take place wherever pupil

desegregation has occurred or will occur for

1965-66, regardless of race, color or national

origin.

4) That teachers for the ensuing academic term

be assigned to elementary schools regardless of

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-12

race.

16a

5) That the Board shall authorize the appointment

of a competent and qualified Negro Assistant

Superintendent.

6) That the superintendent he authorized to inte

grate all general faculty and principal meetings

for 1965-66 school term.

7) That the superintendent be authorized to make

immediate plans for the desegregation of com

petitive sports in the city school system.

8) That the Board should authorize the employ

ment of qualified Negroes for the offices of the

Superintendent and the Business Manager as

clerks and secretaries.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 65-12

Theodore R. Speigner

, 1965

Date

17a

Answer of Defendant to Interrogatories Submitted by

the Plaintiffs on September 3 , 1965

* * * * #

3. Q u e s t io n : State the number, school and grade of

white children, if any, who attended predominantly Negro

schools during the 1964-65 school year; state the number,

school and grade of white children, if any, who are ex

pected to attend predominantly Negro schools during the

1965-66 school year. In each case, name the Negro schools

and the number of white students per grade in each school

having or expected to have white students.

A nswer: No white children attended predominantly

Negro schools during the 1964-65 school year. No white

children are presently attending predominantly Negro

schools during the 1965-66 school year.

* # # # #

17. Question : State the total number of new positions

created in 1963-64, 1964-65 and 1965-66 and the total num

ber of new teachers and other personnel who supervise

pupils hired during that period to fill such positions. Give

a breakdown of these totals by school, positions per school,

race of successful applicants.

A nswer: Eighteen new teaching positions were created

in 1963-64; sixteen new positions in 1964-65; and four new

positions in 1965-66. The number and race of the success

ful applicants for each of these years was as follows:

1963-64 White 10 teachers

1963-64 Negro 8 teachers

1964-65 White 2 teachers

1964-65 Negro 14 teachers

1965-66 White 3 teachers

1965-66 Negro 1 teacher

18a

Answer of Defendant to Interrogatories Submitted by

the Plaintiffs on September 3, 1965

All of the white teachers listed above were assigned to

teach in predominantly white schools, and all the Negro

teachers listed above were assigned to teach in predomi

nantly Negro schools, except that one white teacher listed

for 1965-66 was assigned to Hillside High School.

W W w -7?

20. Question : State whether the Durham City Board

of Education has issued a regulation to the effect that no

new teacher will hereafter be employed who is not willing

to work on a completely desegregated basis.

Answer: No.

* # % # #

22. Question : State the rules, procedures and practices

(including copies of any written rules), with respect to

transfer of teachers from one position to another, includ

ing separate statements with respect to transfers initiated

by teachers and transfers initiated by the school adminis

tration for the good of the school system.

A nswer : The written policy with respect to transfer of

teachers is attached hereto marked Exhibit No. 9. See

Answer to Interrogatory No. 18 with reference to the fre

quency of such transfers.

Teachers are sometimes transferred from one position

to another, at their request, to facilitate travel if the trans

fer is in the interest of the schools. Transfers are initiated

by the school administration when it is possible to place a

teacher in a position for which she is better qualified than

she would be in her former position.

# # # # *

19a

24. Q uestion : Describe generally the school board’ s

practices with respect to selecting new teachers for the

school system, i. e., the process of selecting those to be

hired from among a group of applicants.

A nswer: New teachers are selected for the school sys

tem on the basis of certification, experience, scholastic rec

ord, recommendations, and a number of intangibles which

include, among others, appearance, personality, general

attitude, and apparent fitness for a given position. Per

sonal interviews are required of applicants in order to

determine the quality of voice and the use of oral English,

and to detect any other strengths or weaknesses of the

applicant which are not apparent in a written application.

25. Q uestion : Describe generally the process of deter

mining the specific assignments of new teachers hired in

the school system.

A nswer: A sincere attempt is made to place each new

teacher in the specific position for which he or she is best

qualified and apparently will be most happy because a

teacher who is happy and satisfied is most likely to con

tribute most effectively to the school program.

Answer of Defendant to Interrogatories Submitted by

the Plaintiffs on September 3, 1965

20a

Exhibit 2-B Attached as Answer to Interrogatories

PRO JECTED C A P A C ITY OF EACH CITY SCHOOL 1965-66 (Exhibit 2-B )

Durha' C ity Schools - Sept b er 13, 1965

School G rades Capacity *

i . Durham High 10-12 1770

2. H illside High 10-12 1350

3. B rogden Junior High 7-9 780

4. C a rr Junior High 7-9 970

5. Holton Junior High 7-9 695

6. Shepard Junior High 7-9 595

7. Whitted Junior High 7-9 1430

8. Burton 1-6 745

9. Club B ou levard 1-6 680

10. C re s t Street 1-6 225

11. E ast End 1-6 770

12. Edgem ont 1 -6 475

13. F ayettev ille Street 1-6 660

14. H ollow ay Street 1-6 545

15. Lakew ood 1-6 420

16. Lyon P ark 1-7 600

17. M orehead 1-6 420

18. North Durham 1-6 420

19. W. G. P ea rson 1-6 965

20. E„ K, Powe 1-6 700

21. Y . E. Smith 1-6 640

22. Southside 1-7 380

23. C. C. Spaulding 1-6 615

24. W alltown 1 -6 285

25. G eorge Watts 1-6 420

♦Based on 30 pupils p er room in the p r im a ry grades and 35 pupils per

room in grade 4 through 8 as room s are actually assigned .

1553

581

739

535

572

337

429

356

278

270

471

515

150

321

im

•k c;

ENROLLMENT BI GRADES

WHITE

1965-66

September 13, 1965 - Monday

SCHOOL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

1

12 i

Durham High 514 528 511 i

Brogden Junior 192 188 183 Sp 18 —

Carr Junior 224 276 _ 239

Holton Junior 212. 162

i!

i

___

1

Club Boulevard 88 102 88 108 ____It ... 12

Ed g onion t 66 12 27 30 41 50

Sp 13

Sp 13

CSIP *

85

dEsaaaot

Holloway Street 85 71 74 65 62 _ i7 .Sp 12

Lakewood 56 58 63 67 68 44

Morehead 39 46 47 43 45 33 1_25

North Durham 46 48 44 38 47 47

E. K. Powe 85 86 78 76 85 61

Y. E. Smith 83 90 82 82 69 96 Sp 13

1Southside 19 25 22 22 ___ 12__ 20 15 Sp 10

' George Watts 52 _ki ____ 18 „ ____ 18__ 1____54_ T 24

TOTAL 619 579 563 589 582 554 650 627 575 514 528 511

102 _2S 18

753 722 532

ft

0<w83

0

M*

>IP is an ungraded primary group.

E

xhibit 2-C Attached as Answ

er to

ENROLLMENT BY GRADES

NEGRO

1965-66

Monday, September 13 > 1965

%OOL

__

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

’

12 {

_J?*rham High 41 26

1

15

ogden Junior 15 14 8 Sp 1

_Cir*r Junior 57 71 55

_J<‘ .lton Junior 11 9 8

C-ab Boulevard

I-a'emont 7 5 2 4 4 2

Sp 2

Sp 4

~CSIF—

5

SiiKE

n.-.Llov/ay Street 11 7 8 6 3 11 Sp 3

L.irewood 1 3 3

! K-:~ ehead 13 15 10 10 9 9 T 3

Ik/'th Durham 10 5 9 13 8 9

E, K. Powe 1 1 2 1

Y. E. Smith 1 2 1 2

S^uthside 2 4 4 4 i 1 5 Sp 1

f

1

GeiTge V/atts 2 8 ___ 3___j ____ L 1 T 2 _ 1t

T, m 47 39 42 43 35 39 88 94 70 41 26 15

. 1 4 _ 6 1

102 io o 42

!%:

Ixi-

/S O

\Sfi I

E

xhibit 2-D

A

ttached as A

nsw

er to Interrogatories

23a

Exhibit 2-E Attached as Answer to Interrogatories

(E xhibit 2-E )

NUMBER OF PR O F SIGNAL PERSONNEL AT EAC SCHOOL BY RACE

Septem ber 13, 1965

ST A FF, BY RACE

SCHOOL White N egro

Durham High 80

H illside High 1 64

B rogden Junior High 28

C arr Junior High 40

Holton Junior High 27

Shepard Junior High 25

Whitted Junior High 48

Burton 26

Club Boulevard 23

C rest Street 9

East End 27

Edgemont 16

Fayettev ille Street 21

Holloway Street 20

Lakewood 13

Lyon P ark 19

M orehead 15

North Durham 14

W. G. P earson 32

E. K. Powe 20

Y. E. Smith 23

Southside 10

C. C. Spaulding 21

W a lit own 10

G eorge Watts 15

24a

Exhibit 4 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories

JSXH J & IT //

DURHAM CITY SCHOOLS

JUNE 1965

NUMBER OF NEGRO PUPILS AT EACH GRADE LEVEL

1964-65

SCHOOL ________1 2 3 4 5____6 7 S 9 10 II 12 Total

Durham High 1 ft 12 8 38

Brogden Jr. High 11 13 5 * 1 29

Carr Jr. High 30 67 40 137

Holton Jr. High 7 10 4 21

Club Boulevard

Edgemont 4 6 3 5 2 • 2 3 22

Holloway Street 4 5 7 4 5 10

*

3 35

Lakewood 0 0 0 0 2 0 2

Mo rehead 17 10 i i 12 5 8 63

North Durham 2 6 6 5 6 3 28

E. K. Powe 0 1 0 1 0 0 2

Y„ E. Smith 1 0 1 0 0 0 « i 2

Souths ide 2 1 3 0 0 2 1 9

George Watts 3 8 4 1 1 3 20

TOTAL 33 37 35 28 21 28 49 90 .49 18 12 8 408

* Special classes ___________7 Total

Holloway Street 1

Mo rehead 4

Y. E. Smith 1

Brogden 1

ia-tm&jtjj

-+//L r 0F a/ £0/10 c s w ^ ^ s A-rrt5A/c///& f z k o m 1 ///)//rj -i W /nr£ sw ctn-^

Monday, September 13, 19&5

a y (2

SCHOOL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

I

i12 ,

Durham High 41 26

|

15

Brogden Junior 15 14 8 Sp 1

Carr Junior 57 71 56

Holton Junior 11 9 6

Club Boulevard

Edgeinont 7 5 2 4 4 2

Sp 2

Sp 4

"C3TP

5

Holloway Street 11 ‘ 7 8 6 3 11 Sp 3

Lakewood 1 3 3

Morehead 13 15 10 10 9 9 T 3

North Durham 10 5 9 13 8 9

E. K. Powe 1 1 2 1

Y. E. Smith 1 2 1 2

Southside 2 4 4 4 1 1 5 Sp X

i

1

' George Watts 3 2 8 ___ 3___ ___ L _ i T 2 — li

TOTAL 47 39 42 43 35 39 88 94 70 41 26 15

14. 6 1

102 100 42

4~

ct>

o

o

<<i.ObCo

E

xhibit 4 A

ttached as A

nsw

er to Int

26a

Exhibit 5 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories

(E xhibit 5 )

NEGRO PUPILS

ATTENDING PREDOM INANTLY WHITE SCHOOLS FO R THE FIRST TIME

Septem ber 1965

SCHOOL ______________ ______ GRADE T O T A L

1

i 1 2 3 4 S 6 7 a.- 9 10 11 12

Durham High S ch ool! 37 13 4 54

B roaden Junior High 13 3 16

C a rr Junior High 56 33 7 ...... 9 6

H olton Junior High 10 5 1 16

Club B ou levard 0

Edgem ont * 6 4 1 .....11 .....

H ollow ay Street * 11 6 4 1 ? 7

I

30

Lakew ood 1 3 2 6

M orehead 13 2 2 4 2 9 32

N orth Durham 9 3 4 4 5 2 i 27

E. K. Powe 1 1 1

i

i

I 3

Y, E. Smith 1 2 2

1! 5

Southside 2 2 3 1 1 4 : 13

G eorge Watts 2 1 1 1 ! 8

S p ecia l Education *

Edgem ont - C laes 1 ̂ __________ ______________________________ _____ 3

Edgem ont - C lass 2 2 2

H ollow ay Street 2 2-

Total 324

Exhibit 6 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories

/ / ('-

In terrogatory #10

27a

T each er and su p erv isory vacancies f ille d during the 1964-65 sch oo l

term :

School Number P osition

Race o f su ccess fu l

_____ applicant

Durham High 3 Ge rm an

English

Home E con om ics

White

White

White

C a rr Junior High 2 7th M ath-Science

7th M ath-Science

White

White

Holton Junior High 1 7th E n glish -S ocia l

Studies White

Shepard Junior High 1 7 th M ath-Science N egro

Whitted Junior High 2 A rt

Spanish

N egro

N egro

Club B oulevard 1 Prim ary- White

C rest Street 1 L ibrary N egro

East End 1 P r im a ry N egro

Edgemont 2 L ib ra ry

Specia l Education

White

White

Mo re he ad 1 G ram m ar White

North Durham 1 G ram m ar White

Y. E. Smith 1 Speech therapy White

Souths ide 1 P rin cip a l White

G eorge Watts 1 G ram m ar White

There was one application made at the tim e o f the vacancy fo r each of

the fo llow ing positions: C rest Street, lib rarian , Edgem ont, librarian and

sp ecia l education, A ll other vacan cies w ere filled by applicants still

available from the lis t accum m ulated during the preced in g sum m er. It

is im p oss ib le to give a re a lis tic figure on the num ber of applicants actually

available because m ost of the applicants had a lready taken other teaching

positions by the tim e the above vacan cies occu rred .

28a

Exhibit 8 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories

(Interrogatory No. 14)

Recruitment and Selection

4111

A. General Point of View

1. The outstanding educational program wanted in this

district depends upon getting outstanding teachers

and holding them.

2. This district can secure the kind of teachers it wants

by an effective recruitment program based on alert

ness to good candidates, initiative that results in

prompt action, and good personnel practices in deal

ing with applicants.

3. The effectiveness of our education program is best

secured by assigning personnel where they work best

in meeting the needs of the district.

B. Employment of Teachers

1. It is the responsibility of the Superintendent of

Schools to determine the personnel needs of each

school and to locate suitable candidates to recom

mend for employment to the Board of Education.

a. It is the responsibility of the principal to report

the personnel needs in his school to the Super

intendent as early in the year as possible.

b. It is the responsibility of the principal and the

teachers to assist the Superintendent to locate

or recommend and to secure the services of

suitable teachers.

29a

Exhibit 8 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories

The principal, with the help of the classroom

teachers, must play the major role in locating,

recommending, and securing outstanding student

teachers.

2. All candidates for employment as teachers must

make application for positions through the office of

the Superintendent.

a. The Superintendent is responsible for the final

selection of desirable candidates for recommenda

tion to the Board of Education.

Whenever possible, each principal will be asked

to interview those candidates judged by the

Superintendent as possibilities for filling the

needs of the principal’s school and to make recom

mendations concerning their employment or pos

sible assignment.

b. All applicants are to receive considerate and

prompt service. Candidates will be evaluated

on their merits and qualifications for a position;

basic essentials sought are: Intelligence, train

ing, personality, and interest in boys and girls.

In effect

January, 1965

Uniformly applied in hiring teachers and other personnel.

30a

4115

Exhibit 9 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories

(Interrogatory No. 15)

Assignment and Transfer

The assignment of staff members and their transfer to

positions in the various schools and departments of the

district shall be made by the superintendent on the basis

of the following criteria:

1. The needs of the school system as determined by the

board upon the recommendation of the superinten

dent;

2. Contribution which staff member could make to stu

dents in new positions;

3. Qualifications of staff members compared to those of

outside candidates both for position to be vacated

and for position to be filled;

4. Opportunity for professional growth;

J 5. Desire of staff member regarding assignment or

transfer;

6. Length of service in Durham City Schools,

j These criteria are listed in order of their importance.

In effect

May 24, 1965

31a

Exhibit 10 Attached as Answer to Interrogatories

\ h ; t j i J -

Jr, f en -* tU ̂ aXBSt 16

DURHAM C IT Y S C H O aS

TEACHERS H IR E D DURING THE SCHOOL YEAR EACH YEAR

SCHOOL 1 2 S 2 I9 6 0 1 9 6 1 1 9 6 2 1 2 6 1 1 9 6 4

D urh a m H ig h 1W 3W 3W

H il ls id e H ig h

B ro g d e n J r . H ig h 1W 1W 3W

C a r r J r . H ig h 2W 2W 1W 5W 3W

H o lto n J r , H ig h 2W 1 ¥

S h e p a rd J r . H ig h IN

W h it te d J r . H ig h IN IN 2N IN 3N

B u r to n

C lu b B o u le v a rd 2W 1W 1 ¥ 1W

C re s t S tr e e t IN IN

E a s t E n d IN IN 2N IN

E d g em o n t 1W 1W 1W 1W 1W

F a y e t te v i lle S tr e e t IN

H o llo w a y S tr e e t 1W 1W 2W

L a ke w o o d 1W 1W 1W 1 ¥

L y o n P a rk IN

M o re h e a d 2 ¥ 1W

N o rth D urham 1W 1W

W . G . P e a rs o n IN IN

E . K . Powe 1W

Y . E . S m ith 1W 1W 2W 3 ¥ 1 ¥

S o u th s id e 1W 1W 1W 1W

C . C . S p a u ld in g

W a llto w n IN

G e o rg e W a tts 2W 1W 2W 1W

lye j/ /iO/tt / s rvi- J r PI jCHM er-P p i ’JPA/i' ////;.• p m /i p

32a

Exhibit I I Attached as Answer to Interrogatories

/=■ / f> //

In terrogatory #19

Durham City Schools

P erson n el who serve in m ore than one sch oo l

SUBJECT

TAUGHT

NUMBER

OF TEACHERS

RACE

OF TEACHER

PREDOM INATE

RACE OF 3CHOO

A rt 1 v/hite V/hite

A rt 1 N egro N egro

L ib ra ry 5 White White

L ib ra ry 2 N egro N egro

M usic 6 White White

M usic 4 N egro N egro

P h y s ica l Education 2 V/hite White

P h ysica l Education 1 N egro N egro

G eneral Supervision 2 White White and

N egro

G eneral Supervision 1 White White

G eneral Supervision 1 N egro N egro

33a

-----4r—

Geobge Reid Pabks, a witness called pursuant to agree

ment, being first duly sworn in the above causes, was

examined and testified on his oath as follows:

Direct Examination by Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Mr. Parks, state your full name. A. George Reid

Parks.

Q. And you are a member of the Durham City Board of

Education! A. Yes.

Q. How long have you been a member, approximately!

A. Approximately six years.

Q. Mr. Parks, would you give me a brief resume of your

educational and employment background during this period,

during your work with the Durham City Board of Educa

tion! A. My educational background, Accounting Major

at the University of North Carolina, Class of 1935. I have

been employed by Golden Belt Manufacturing Company

since 1937. At present, I am President of the Company.

Q. Mr. Parks, do you have any academic training relat

ing to schools or school administration or anything like

that! A. No special courses in school administration.

Q. Now I understand you were Chairman of a Commit

tee of the School Board which had the task of studying

—5—

the problem of employment and assignment of professional

personnel and considering the matter of teacher desegrega

tion, is that correct! A. That is correct.

Q. Could you give me a statement, a general description

of the activities of your Committee, starting with when they

were appointed and who served on the Committee, what

Deposition of George Reid Parks

34a

you did in terms of meeting, and so forth? A. I believe all

of that is outlined in that statement, is it not?

Q. Well, some of it is. When was your Committee ap

pointed, approximately? A. It was probably in January.

Our first meeting was on February 5th.

Q. And the members of your Committee were? A. Mrs.

Bugg, Doctor Speigner, and I. Mr. Hannen and Mr. Rhine-

hart were ex officio members.

Q. There are three members of the School Board plus

the Superintendent and the Chairman of the School Board?

A. That’s right.

Q. I have a copy of a report dated August 20, 1965, which

has, I believe, been filed with the Court. Was this the re

port of your Committee? A. Yes, that’s the report.

Q. Now has this report and your recommendations in it

been submitted to a full Board, a full School Board? A.

— 6—

Yes, sir, it has.

Q. And has the School Board taken any action with

respect to it? A. They approved the report of the Com

mittee.

Q. About when was that? A. It’s been very recently; it

was on Tuesday, I believe, following this date. This was

filed about a week before the School Board meeting. I

believe it was the September School Board meeting. I be

lieve it was—

Q. Yesterday was September 13th.

Mr. Pearson: August the 30th.

A. August the 30th.

Q. August 30, 1965? A. That’s correct. That was a

special meeting.

Deposition of George Reid Parks

35a

Q. The report does not indicate anything with respect to

the method or criteria for hiring new teachers, new em

ployees as teachers in the school system. Can you give me

a description of how it worked? A. Mr. Hannon inter

viewed and employed teachers; I think that information

should be taken from him.

Q. As part of your Committee study, did you make any

study of this process? A. Not of the employment; not of

the techniques of selection, no.

Q. Did you make any study with respect to the plaee-

—7—

ment of teachers in specific schools and positions within

the system, what the standards were? A. Not in specific

schools, no.

Q. All right. Did you make any study of the— Are you

informed with respect to the recruitment program for in

viting applicants to take jobs or what is done along those

lines? A. I am generally informed but not specifically.

Q. What is your understanding? A. Brochures are dis

tributed to a number of schools in this area, outlining the

advantages of teaching in the Durham City schools; and

the teachers in these schools make recommendations from

time to time to people they know who would like to teach

here; those are referred to the Superintendent.

Q. Do they invite applicants for specific jobs or invite

applications? A. I don’t know.

Q. The application form, the one that’s marked “ old”

and the one that’s marked “new” , are attached to your re

port. And I notice that both of them ask for the race of

the applicant and ask for a photograph. Did your Com

mittee take any action with respect to that or any recom-

Deposition of George Reid Parks

36a

mendation with respect to the meeting of those require

ments? A. No.

Q. Did the Committee decide to continue those, or dis-

—8—

cuss it at all, or what? A. There were minor changes

made in the employment application form. Those were

attached to show the minor changes that were made. The

“old” has been in effect for some time and minor changes

were made in the “new” . There are no significant differ

ences between the two.

Q. That change you mentioned had to do with the ques

tion about the National Teacher Examination? A. I be

lieve that was one of them, yes.

Q. Do you know what the others were? I couldn’t find

any others. A. Mr. Hannen may recall. I think I would

have to make a detailed check of the old and the new in

order to answer that.

Q. Well, we won’t take the time now. But getting back

to the matter I asked before, what about this business of

asking the applicant for his race and asking for the photo

graph? Did your Committee decide that this was a thing

that should continue on the form, or what? A. That was

not discussed.

Q. Do you have a general idea, Mr. Parks, how many

applications for new positions as teachers were received

and how many positions were open, say, this year or the

last school year? A. No, I do not.

Q. You wouldn’t know either the number of new teachers

hired or the number of positions? A. No, I do not.

—9—

Q. Did your Committee use any of that information? A.

No, we did not; we did not use any of that information.

Deposition of George Reid Parks

37a

Q. Do you know the basis upon which the teachers are

paid in the system, the school system? A. Yes.

Q. What— They have a salary scale, do they? A. A

salary scale and a supplementary salary scale.

Q. What are the variables, the experience, the number

of years teaching? Are those— A. Both.

Q. Those are the two things that determine salary? A.

A Bachelor’s Degree has one salary scale and a graduate

degree has another. Of course, a graduate degree carries

a higher pay scale.

Q. And within the scales-— A. Are years of experience.

Q. —years and experience teaching? A. Yes; up to

thirteen.

Q. Do they count years taught in other systems other

than in Durham? A. Yes, sir, they do.

Q. Does the salary scale take anything else in account

that you know of? A. I ’m not sure of your question.

Q. Are there any other things that determine salary

- 10-

other than years of experience teaching? A. No.

Q. And Degrees? A. No, not once they are employed;

they do determine this scale.

Q. Your report contains references to the National

Teachers Examination? A. Yes.

Q. Am I correct in understanding that very few of the

teachers presently in the system have taken the test? Is

that the fair summary of it? A. Our report includes all

the teachers in the City schools who have taken the test

who are employed at the time of the report.

Q. If you’ll look at it and just verify this. It indicates

81 teachers have taken the test and have the scores on file

and 571 have not taken the test? A. That’s correct.

Deposition of George Reid Parks

38a

Q. Your report also mentions something about the test

now being required. Is it required of all new teachers? A.

Yes, sir, it is.

Q. How long has that been in effect? A. It was passed

by the North Carolina Legislature in 1961.

Q. I see. And it went into effect that year? A. Yes.

— 11—

Q. Well, have all the—And the minimum score required

by the Legislature is 450 points on the exam? A. That’s

required for certification.

Q. Now more recently in 1964, the Durham Board re

quires a 500 score? A. That’s correct.

Q. For employment, is that correct? A. That’s correct.

Q. Now has this been required of all new teachers who

have been hired during this period in Durham? A. Yes.

Q. How about non-certified teachers? Are there non-

certified teachers in Durham who don’t meet these require

ments? A. I believe there’s one with a B certificate.

The Witness: Is that correct, Mr. Hannen?

(Discussion off the record.)

A. (Continuing) I don’t know.

Q. Your report also refers to a questionnaire which the

School Board or your Committee distributed to teachers.

Do you have a copy of that? A. Isn’t that attached to that?

Mr. Nabrit: Off the record.

(Discussion off the recoi’d.)

Mr. Nabrit: On the record.

Deposition of George Reid Parks

39a

Deposition of George Reid Paries

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Was this form prepared by your Committee or for

your Committee? A. For our Committee.

— 12—

Q. And was it distributed during the last school year?

A. Yes.

Q. I ’m looking at a tabulation apparently—I think the

report indicates this is a report of the first choices? A.

That’s correct.

Q. Did you make any tabulation of the total number of

Negro and white teachers who indicated that they were will

ing, either a first, second, or third preference, to teach in

tegrated classes or classes of pupils predominately in the

other race? A. These are only first choices.

Q. That’s what I thought. I wonder if you made a tabu

lation of the other choices. A. No------

Q. Do you know how many teachers—for example white

teachers—indicated as a first, second, or third preference

that they would be willing to teach integrated classes? A.

These are their first preference. No other second or third

choices were tabulated. These are the only tabulations

made.

Q. Are the original forms still available? A. Yes, they

are.

Q. All right. Was there any other effort to inquire about

the attitude of the teachers other than this questionnaire?

—13—

A. No.

Q. They were not asked whether or not they were will

ing to serve on faculties with teachers of the other race

or any question like that? A. As far as our Committee

was concerned, there were no questions asked. This ques

tionnaire was submitted to them, filled out, and returned.

40a

Q. The questionnaire indicates, “ signature optional” .

Was that the case! A. That is the case.

Q. Now, Mr. Parks, what is your understanding* as to

the pattern of teacher assignment on a racial or non-racial

basis! On a racial basis now, specifically. Is it still true

that there are no Negro teachers teaching any white chil

dren in the system? A. That’s correct,

y Q. Are there any white teachers who teach Negro children

in the system? A. Yes.

Q. How many white? A. One.

Q. Where is that teacher employed? A. Hillside High.

Q. When did she take that post? A. The beginning of

this school year.

—14—

Q. September, ’65? A. Yes.

Q. Is that the first and only such white teacher to teach

\ in a Negro school that you are aware of? A. Yes.

Q. Did your Committee have anything to do with that?

' A. No.

Q. Did your Committee have at any time any communi

cation with the United States Office of Education about the

matter of teacher desegregation? A. Our Committee as

such had no such communication.

Q. As a member of the School Board have you— A.

There have been communications through the School Board

for the School Board.

Q. Would you be in a position to tell me what the situa

tion is? A. Well, it’s a long story. I have quite a few of

the memorandums here that we have received.

Q. Could I see some of them, or could you summarize

what’s gone on first?

Mr. Spears: Off the record.

(Discussion off the record.)

Deposition of George Reid Parks

41a

Q. Let me ask one or two questions: Has the Board

submitted a plan or plans—proposed plans—to the Com

missioner of Education? A. Yes.

—15—

Q. And have any of them been approved? A. No.

Q. Are they still pending? A. As far as I know.

Q. And of course you know there is an application pend

ing? A. As far as I know, that’s true.

Q. What has the Commissioner’s office advised the Board

with respect to teacher desegregation? A. Well, among

the things, in the application for employment we can’t ask

their sex, their race, we can’t ask for pictures; they are re

quired to teach anywhere they desire to teach. Those are

some of the most recent communications regarding employ

ment of teachers.

Q. And have any of them been adopted by the Board as

of now? A. No.

Q. If I could look at those a little bit later, please? A.

I have plenty of them.

Q. Your report indicates that no parent of a white child

has requested assignment to a predominantly-Negro school,

is that correct? A. That’s correct.

Q. And that those white children who have been assigned

to Negro schools have requested reassignment and have

been granted? A. That’s correct.

—16—

Q. Hid that experience enter into your Committee’s

recommendation on the question of whether or not to

change? A. This indicated the attitude of parents and we

submitted that as part of our report.

Q. I understand. I was just wondering what that meant

to you? A. Well, as a member of the School Board, I

think we are—I am obligated to try and serve the people

in the community; their wishes, of course, are influential.

Deposition of George Reid Parks

42a

Q. Well, did yon take this as an indication that—yon

I interpreted it to indicate that the white parents did not

\ choose schools with Negro teachers? A. That’s correct.

| Q. Your report also says that with complete freedom of

choice—I’m paraphrasing. A. Yes.

Q. —approximately 94 percent of the Negro pupils at-

S tended predominantly Negro schools. This gives substan

tial strength to the present policy of teacher assignment.

Would you explain that? A. That means that most of the

/Negro children prefer Negro teachers.

Q. And that conclusion was one of the bases that your

Committee acted on to continue your present policy? A.

Yes.

—17—

\

Q. Now your report says under the part that is Recom

mendation 2c. that—on the second sentence, says, “The

Committee recommends that we continue our present poli

cies, but that the Board in the employment and assignment

of teachers and other personnel by majority vote of its

members make exceptions to any of its policies for valid

and sound educational reasons.” What present policies

were you referring to? A. The present policy of employ

ment and assignment.

Q. On a racial basis, assigning Negro teachers to schools

with all Negro children and white teachers to the other

schools? A. Employing the best Negro teachers we could

for Negro schools and the best white teachers we could for

white schools.

y Q. And the reference to exceptions to that was that if a

particular applicant came forward, you felt that the Board

might make exceptions in a particular case, is that the idea ?

A. I think that statement is clear. I don’t know what cir

cumstance will require special consideration but they had

Deposition of George Reid Parks

43a

in mind making exception for valid, sound educational rea

sons.

Q. In any event, the general pattern would be as before

and it would only be the exceptional case that there would

be any assignment of a Negro teacher to a white school or

a white teacher to a Negro school? A. That’s correct.

Q. That was your Committee’s recommendation? A.

That was the Committee’s recommendation.

—18—

Q. And that was adopted by the Board? A. Yes.

Q. By the full Board? A. Yes.

Mr. Spears: I don’t think he understands you.

When you say “the full Board” , do you mean unani

mous?

By Mr. Nabrit;

Q. I meant that was adopted by the Board of Education.

A. That is correct.

Q. Was there a vote on that? A. Yes.

Q. Do you recall the vote? A. I believe it was five to one.

Q. Who dissented? A. If there was a dissent, it was

Doctor Speigner.

Q. Did Doctor Speigner join in the Committee report,

your Committee’s report, or did he disagree? A. There

are some areas in which he disagrees.

Q. They are not indicated on the report, are they? A.

No. He didn’t ask for anything to be added to the report.

He did not file a minority report.

Q. Did he file a minority report with the School Board?

A. He filed a statement which he read at one of the Com

mittee meetings. At the Board meeting at which this was

approved, he filed that at our request.

Deposition of George Reid Parks

44a

Deposition of George Reid Parks

—19—

Q. Do you have a copy of that? A. Yes, I do.

Q. I take it that Doctor Speigner was in favor of faculty

desegregation. He proposed eight steps listed here. Did

your Committee, or sub-committee, consider these pro

posals? A. Yes, they did. He read these at a Committee

meeting.

Q. Did you agree with any of them or disagree with all

of them, or what? A. The final agreement was as indicated

in the report. That was the majority opinion of the Com

mittee.

Q. Would it be fair to say that you didn’t agree with

Doctor Speigner’s report? A. I think it’s obvious that the

majority did not agree with that.

Q. One item on here refers to special subject teachers.

What are they? Are they teachers in junior and senior

high schools, is that— A. I—

Q. Well, I can ask him. A. That will be better.

Q. Well, what about integrating general faculty and

Principal meetings? Have they been desegregated now?

A. That’s covered in the report, the areas in which there

is complete desegregation.

Q. Well, let’s go to that. Your report on page 5 says,

— 20—

“Desegregation has been achieved and will be continued in

the areas indicated below: a. Supervisors, Principals, and

Teachers’ meetings.” Would you tell me what meetings

those are? A. I believe that’s as clear as I could make it,

Mr. Nabrit.

Q. What about the workshops and in-service training

courses? What are they and who conducts them, and so

forth? A. I don’t know who conducts them but there are

frequently held workshops for new techniques in the vari

ous courses for upgrading the staff. I don’t know the fre-

45a

quency of these and I don’t know who are the supervisors

or the instructors.

Q. What are grade level meetings! A. First grade,

second grade, third grade, and so forth; all the grades in

the school come together for a meeting on a particular

grade problem.

Q. You mean all the first grade teachers from the whole

City! A. Yes.

Q. Well what’s the frequency of those, do you know!

A. I don’t know.

Q. What do you mean by “Supervisory staff work” , that

desegregation has been achieved in supervisor}' staff work!

A. Well, to me that’s self-explanatory. It’s supervisors;

their work is integrated.

Q. You mean the whites supervise Negroes. Are there

any Negroes who supervise whites! A. I can’t give you

the complete details because I don’t know.

—21—

Q. Did your Committee make any study of distribution

of teachers and schools in terms of what schools had the

number of most-experienced teachers, which had the most

teachers of less experience, in terms of the salary groups,

scales, and standards! A. That was not discussed.

Q. You don’t know which school has the teachers with

the most experience and higher salaries and which have the

lower! A. That was not considered by our Committee.

Q. Do you know! A. Yes, I do.

Q. Do you know, in terms of the Negro schools and the

white schools! A. Yes, I do.

Q. What is that! A. The Negro teachers are, on the

average, higher-paid teachers than the white teachers.

Q. And that would he the function of experience! A.

And Degrees.

Deposition of George Reid Parks

46a

'-N„.

Q. Degrees? A. Yes.

Q. What about certification? A. Well, they all have to

be certified to teach.

Q. Did your Committee consider—or as a Board mem

ber, do you know of any State laws or regulations of the

State Department of Public Instruction which has a bearing

on the matter of faculty desegregation? A. No.

—22—

Q. Do you know whether or not the allotment of teaching

positions by the State Department is still done on a racial

basis and they allot so many white positions and so many

Negro positions?

Mr. Jarvis: I object to the form of the question,

Mr. Nabrit, “Is it still done” . It may have been done

in the past but I ’m not sure.

Q. What do you know about this subject ? A. Our Com

mittee didn’t consider; you’re asking for my knowledge ?

Q. Yes. A. This year it was discontinued; assignments

this year were not on a racial basis.

Q. You say “assignment” . I take it you mean “allot

ment” ? A. Allotments.

\ Q. Allotment of numbers. A. Allotment of numbers

■were not so many for Negro schools and not so many for

'white schools.

Q. And that was action by the State Department of Pub

lic Instruction? A. I assume it was.

Q. Have you made any study of the comparative test

scores of Negro pupils and white pupils in the system for

standardized tests? A. The Committee did not consider

—23—

Deposition of George Reid Parks

that.

47a

Mr. Jarvis: I ’m not sure I understood your ques

tion.

Mr. Nabrit: I asked Mm about a comparison of

scores of Negro and white pupils on a standardized

test.

Mr. Jarvis: You asked him— All right.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Going back to the Department of Health, Education

and Welfare, are you familiar with a document issued by

the Commissioner of Education called “ Guidelines for De

segregation” ? A. I ’ve read that.

Q. Did your Committee give consideration to the provi

sions in that relating to faculty desegregation? A. No.

Q. You didn’t discuss this? A. No.

Q. Was that because you disagreed or didn’t want to do

that? A. We didn’t discuss it; the question was not raised.

Q. Did you think about it individually? A. No, I didn’t.

Q. Did you receive a copy of a so-called model desegrega

tion plan issued by the Office of Education ? Have you seen

that? A. I don’t recall that particular one.

Q. It looks something like this. Do you recall seeing it?

A. Yes, I ’ve seen this. It’s captioned, “Plan of Desegrega

tion” , not “Model” .

—24—

Q. Correct. You are referring to this document issued

by the Commissioner. Did your Committee give any con

sideration to the staff desegregation matters mentioned in

this plan of desegregation and to the attachment marked,

“Additional steps toward staff desegregation” ? A. It

wasn’t considered by the Committee.

Q. It was not? How many meetings did your Committee

Deposition of George Reid Parks

48a

have, do you know? A. I believe they are all referred to

in the report.

Q. All right. There were—February 5,1965, was the first

\ one? A. February 5 was mentioned first; then June 18th

\ was mentioned.

\ Q. Were there any subsequent meetings? A. August 16;

that was the last one.

Q. Was the final decision not to ask the teachers already

employed to take the National Teacher exam? A. That’s

correct.

Q. One of the attachments indicate that the members or

the representatives of four teachers organizations— A.

That meeting was between Mr. Hannen and Mr. Rhinehart.

Q. I see. Did your Committee consider any programs to

prepare teachers for teaching in a desegregated situation

of any kind? A. No, to give you a direct answer to that

\ - 2 5 -

question.

Q. Has any program along that line been undertaken that

you know of? A. It was hoped that if the teachers would

take this exam that it would point out some of their weak

nesses, so that additional courses and instruction would be

helpful in upgrading them, to bring them up-to-date. That

was the principle purpose in suggesting that they take this

exam.

Q. Do you know of any efforts by the Board to apply

for assistance from the Commissioner of Education, finan

cial assistance or technical assistance, under the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, a provision for financial grants for

School Boards who conduct such programs? A. No.

Q. As far as you know, there has been no— A. As far

as I know, there has been none for the teachers.

Q. All right. Has there been any requests for assistance

Deposition of George Reid Parks

49a

in drafting plans, consultants to be furnished by the De

partment? A. Not to my knowledge.

Q. Do you know if there are any State agencies that fre

quently refer teachers to you, or school placement offices

that do that? A. I know some are referred from time to

time, but I don’t know which ones or how many.

Q. Are vacancies and positions posted or listed by race?

—26—

A. Repeat your question.

Q. Well, if you have vacancies, personnel vacancies, are

they listed in any way? Do you notify the public at large

or anyone that you have so many vacancies— A. No.

Q. —and invite applications? A. No. Not about post

ing vacancies. There has been some advertising done on a

few occasions for teachers.

Q. Has the advertising indicated that you were looking

for Negro teachers or white teachers? A. I’m not sure

exactly how the ads read.

Q. Does your Committee know of any applications by

white teachers to teach in Negro schools? A. That was not

discussed and as far as I knew there was no knowledge of

that among the Committee members.

Q. What about going out to the Board? Did such a re

quest ever come to the attention of the Board? A. I don’t

know of any.

Q. I ’ll make the question broader: or white teachers to

teach in Negro schools or Negro teachers to teach in white

schools. A. I don’t know of any application.

Q. Do you know of the Board’s considering any people

for such assignments, any individuals? A. I ’ve mentioned

one that was hired.

Q. Any others? A. Not to my knowledge.

Deposition of George Reid Parks

—27—

Q. What about other staff posts! A. What others!

Q. Were there any applicants for other Negroes to work

in white schools and others—in other positions dealing with

children? A. Not that I know of.

Q. Or whites in Negroes? A. Not to my knowledge.

Q. Is it correct that the present practice and policy of

the Board, the School Board, is to assign only white per

sonnel in supervisory, administrative, teaching, and other

positions dealing with children in the schools—to the

schools that are predominantly-white where white children

attend? A. I can’t add anything to my previous statement.

Q. Well, what I was trying to get to, the previous state

ment applied to these other jobs as well as to classroom

jobs? A. I don’t know that that’s necessarily handled the

same way. Are you talking about office staff, for example ?

Q. Well, counselors, librarians, visiting teachers. A. I

do not know of any applications.

| Q. Assistant Superintendents, Principals. I ’m not asking

i you about the applicants; I ’m asking you about the assign

ments. A. I would assume that the assignment policy

would be the same as teachers.

—28—

Q. Both Negro and white schools? A. That’s correct.I ,Those that come directly m contact with the children.*

Q. Has your Committee made any recommendation with

respect to such positions? A. The recommendations dealt

with the general principle, not with a specific group.

Q. Why was Doctor Speigner’s name on the report if he

disagreed with it? A. He was a member of the Committee.

Q. Did he sign it? A. Not to my knowledge; he had an

opportunity to.

Q. Did the Superintendent, at a recent meeting of the

Board, recommend a Negro librarian or special teacher be

Deposition of George Reid Parks

51a

placed in a predominantly-white school? A. We gave

serious consideration to it. That was not the application

that he had. There was a librarian over, I believe, at East

End that was considered for Lakewood School. However,

a better-qualified librarian was found for Lakewood; and

that did not deprive East End of their good librarian.

Q. Did the Superintendent propose this to the Board |

and the Board turned him down? A. Yes, you might say

that.

Q. The Superintendent proposed employing a Negro

librarian to— A. No, not employing.

—29—

Q. Transferring. A. Transferring.

Q. Transferring a Negro librarian to a predominantly-

white school and the Board— A. Well, no action was

taken on it, sir.

Q. Well, did members of the Board indicate they dis

approved of that? A. They indicated that he should see

if he could find—if he could find a qualified, a well-qualified

librarian, to fill that position first. This was before school

started.

Q. About when was this? A. Probably a month ago. I

don’t recall the date of the meeting that was discussed.

# # # # #

Deposition of George Reid Parks

52a

A nnie Laurie Bugg a witness called pursuant to agree

ment, being first duly sworn in the above cause, was ex

amined and testified on her oath as follows:

Direct Examination by Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Would you state your full name? A. Mrs. Everett

Bugg, Jr.

Q. Mrs. Bugg, would you give me a brief resume of your

educational background, employment, and work experience

you have had? A. Well, I graduated from Duke Univer

sity in the Class of ’36, majored in History. Other than

that, primarily a wife and parent.

Q. And you are a member of the Durham School Board?

A. Yes.

Q. How long have you been on the Board? A. Approx

imately three years.

Q. And you were a member of the Committee Mr. Parks

just talked about? A. Yes, I was.

Q. You were sitting in the room when I was questioning

Mr. Parks? A. Yes, I was.

Q. Now would you look at a copy of your Committee re-

—5—

port? By the way, did you sign it? Is it your report? A.

No, sir, I neglected to do that.

Q. Do you adopt it? A. Yes, sir.

Q. This is the report you are in favor of? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you study any of the material from the Commis

sioner of Education on the proposed plan of desegregation

as guidelines? Did you see any of those? A. I have

tried to read each of it as it has come in to us by the week.

Q. Did you make any attempt to make recommendations

by your Committee which were consistent with the things

the Commissioner of Education sent to you? A. No, I

Deposition of Annie Laurie Bugg

•—4—

53a

made no such attempt. I don’t believe that any member of

the Committee did; I’m not sure.