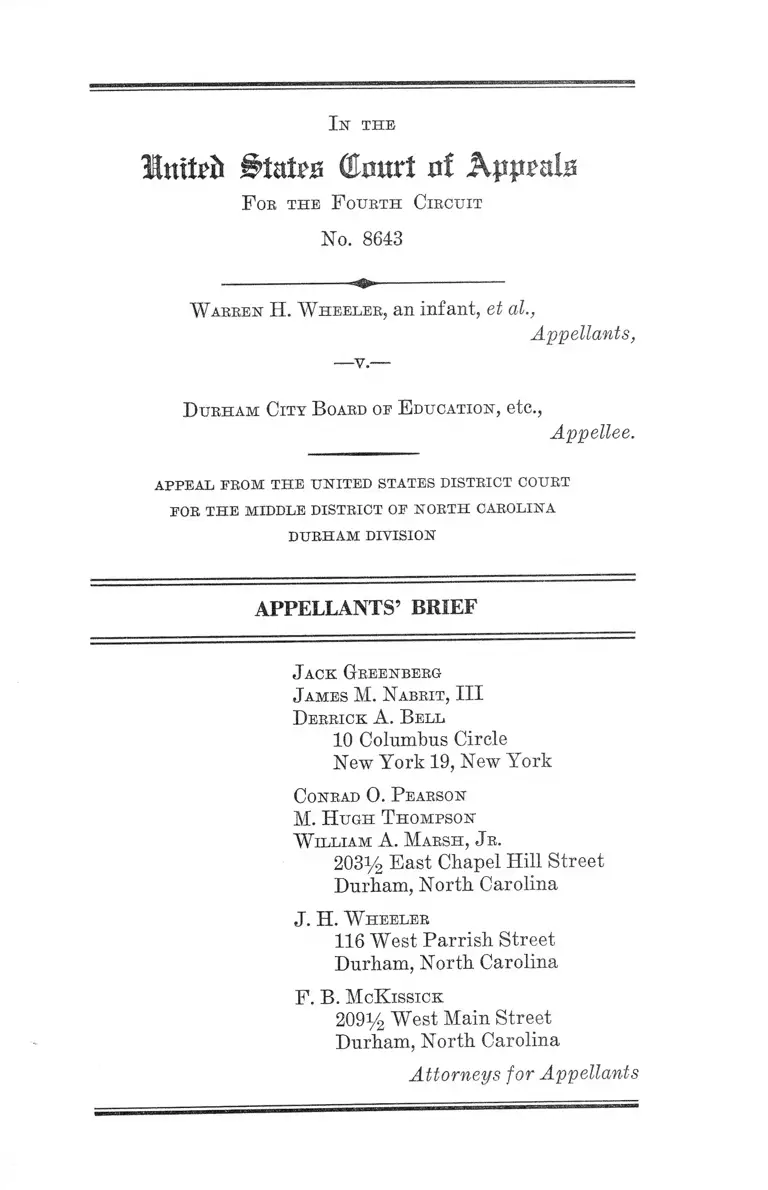

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education Appellants' Brief, 1962. 9bb18bf2-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/edf1c09e-b3cd-46f2-8422-4951a63d274d/wheeler-v-durham-city-board-of-education-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

Initpft i^tate (Eattrl nf Appeals

F oe t h e F o u r t h C ir c u it

No. 8643

W a r re n H. W h e e l e r , an infant, et al.,

Appellants,

— V .—

D u r h a m C it y B oard oe E d u c a tio n , etc.,

Appellee.

APPEAL EROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OE NORTH CAROLINA

DURHAM DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J a c k G reen berg

J a m e s M. N a b r it , III

D e r r ic k A. B e l l

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

C onrad 0 . P earson

M . H u g h T h o m p s o n

W il l ia m A. M a r s h , Jr.

2031/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J. H. W h e e l e r

116 West Parrish Street

Durham, North Carolina

F . B. M cK is sic k

2091/2 West Main Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ........................................... ...... 1

Questions Involved.................................................... . 12

Statement of the Facts .................................................. 13

Initial Assignments by Race ................................... 13

The Board’s Reassignment Practices and Proce

dures for the 1959-60 and 1960-61 School Terms 16

Standards and Procedures on Reconsideration of

Plaintiffs’ Transfer Applications ........................... 22

Argument ............................................................ 25

Introductory.................................................................. 25

I. Plaintiffs will be denied relief to which they

are entitled as individuals so long as Durham

maintains dual racial school zones .............— 27

II. Appellants who concededly exhausted admin

istrative remedies may present to the United

States Courts every issue over which they

have jurisdiction in this case ........................... 33

III. That children in the City of Durham other

than plaintiffs did not pursue the admin

istrative course does not bar them from en

joying their constitutional right to desegre

gation because the administrative remedies

provided by Durham are a sham...... ........ 35

PAGE

11

IV. Plaintiffs are entitled to an order requiring

the City of Durham to set up a nonracial

system of school assignments, or as a tempo

rary measure, pending reorganization, to an

order admitting them to schools they would

PAGE

attend if they were white ..... .......... .............. 42

Conclusion ............. ................. ............... ........... ........... . 43

T ab le of C ases

Allen v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward County,

Va., 266 F. 2d 507 (4th Cir. 1959)............................... 34

Board of Ed. of St. Mary’s County v. Groves, 261 F.

2d 527 (4th Cir. 1958) .............................................. 43

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S.

294 (1955) ..................................................................28, 34, 42

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, —— F. Supp.

------ (E. D. La. Apr. 3, 1962, C. A. No. 3630, not

yet reported) ............................................................ 32, 33, 43

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 242 F. 2d 156

(5th Cir. 1957) .............................................................. 34

Carson v. Warliek, 238 F, 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956)

34, 35, 36, 41

Clemons v. Board of Education, 228 F. 2d 853 (6th

Cir. 1956) ....... ............ ......................... ........................ 41

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ........................... 29, 42

Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (4th Cir. 1959) 36,41

Dodson v. School Board of the City of Charlottes

ville, 289 F. 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961) ........................... 29, 40

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960) 43

I l l

PAGE

Gibson y. Board of Public Instruction of Dade

County, Florida, 272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959) ....... 30, 34

Hill v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 282 F.

2d 473 (4th Cir. 1960) ............ .................................. 29

Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 265 F. 2d

95 (4th Cir. 1959) ...................................................... 34, 37

Houston Independent School Dist. v. Ross, 282 F. 2d

94 (5th Cir. 1960) ...................................................... 43

Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg,

201 F. Supp. 620 (W. D. Va. 1962) ........................... 30

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278

F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ................................................ 29

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsboro

County, Florida, 277 F. 2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960) ....... 30

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of

Memphis, ------ F. 2d — — (6th Cir., No. 14,642,

March 23, 1962, not yet reported) ...................... .30, 31, 34

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961),

rev’g Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F. Supp. 913 (E. D.

Ark. 1960) .................................................................... 34

Pettit v. Board of Ed. of Harford Cty., 184 F. Supp.

452 (D. Md. 1960) ...................................................... 43

Sehware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U. S. 232

(1957) .... ....................................................................... 39

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education,

358 U. S. 101 (1958), affirming 162 F. Supp. 372

(N. D. Ala. 1958).......................................................... 35, 41

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 IT. S. 356 (1886) .................. 34

I n t h e

United Btutm Contort nf Appeal#

F oe t h e F o u r t h C ir c u it

No. 8643

W arren H. W h e e l e r , an infant, et al.,

Appellants,

D u r h a m C it y B oard of E d u c a t io n , etc.,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

DURHAM DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement o f the Case

These cases, Warren II. Wheeler v. Durham City Board

of Education, C. A. No. C-54-D-60, and C. C. Spaulding

v. Durham City Board of Education, 0. A. No. C-116-D-60,

consolidated in the United States District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina, are here on appeal from

the final judgment of District Judge Edwin M. Stanley,

entered April 11, 1962, ordering that plaintiffs be denied

the relief prayed for and that the complaints be dismissed

(414a).

Wheeler was filed April 29, 1960, by 163 Negro pupils

who had unsuccessfully applied for admission to all-white

2

or virtually all-white schools in Durham, North Carolina,

prior to the 1959-60 school term. Prior to the 1959-60 term,

225 Negro children in Durham applied for admission to

white schools. After initial assignments were made on

August 4, 1959 (274a), these 225 reassignment applications

were considered by the school board ex parte at special

meetings held August 25 and 28, 1959, and seven of the

Negro pupils were reassigned to all-white schools (274a).1

Each of the plaintiffs then appealed to the school board on

the reassignment applications which had been denied (274a-

275a). A “ hearing” was held on these appeals on Septem

ber 21,1959 (nineteen days after the school term had begun

on September 2, 1959; 281a); all the applications were

again rejected (274a-278a). Thereafter, this suit for in

junction was filed as a class action alleging racial discrimi

nation in school assignment practices against plaintiffs

and others similarly situated. The complaint prayed for

a decree enjoining defendants from assigning plaintiffs to

any school other than the one to which they would be as

signed if they were white, from operating a biracial school

system, from maintaining a dual scheme of school zone

lines based on race, and from assigning teachers, princi

pals and other personnel on the basis of the race of the

children assigned to the school (19a-21a). In the alterna

tive, it prayed that defendants be ordered to present a

complete desegregation plan, including abolition of dual

racial zones and elimination of other racial discrimination

(19a-21a).

Defendant’s motion to dismiss was denied without preju

dice on October 4,1960 (2a).

1 Two other Negroes were reassigned to a white school at this

time; but they were placed in an all-Negro school when they moved

to another residence on the day before the school term began

(127a; 379a).

3

Wheeler was consolidated (59a) with Spaulding which

had been filed September 12, 1960 (38a). Spaulding arose

out of applications filed on behalf of 116 Negro pupils

(including some who were also plaintiffs in Wheeler) seek

ing admission the following year to white schools in Dur

ham. These plaintiffs were among 205 Negro children who

sought changes of initial assignments made on August 1,

1960 (278a). Seven of these 205 Negroes were assigned

to white schools on August 24, 1960 (279a). Each of the

plaintiffs appealed under the Board’s procedures and the

Board scheduled a “hearing” for September 12,1960 (279a).

The term had already commenced August 30, 1960 (281a).

After the meeting on September 12, 1.960, the Board denied

all the appeals.

The Spaulding complaint, commencing with description

of circumstances leading up to the Wheeler case, alleged

assignments according to dual racial school zones (40a-41a),

that as early as 1955 citizens had petitioned the Board to

desegregate, and in 1956 a similar petition was filed (41a).

It alleged that in 1959 the Board assigned students accord

ing to dual racial maps and that 225 Negro students ap

plied for change of assignment to schools to which they

would have been assigned if white (43a). Nine Negro chil

dren were thereupon assigned to white junior high and

high schools. None of the elementary schools were de

segregated pursuant to a Board decision made prior to

the hearing not to do, so (43a). Their applications for re

assignment having been denied, plaintiffs applied for hear

ings. Almost three weeks after school commenced these

hearings were held. Those not present at the hearing, al

though represented by counsel with powers of attorney,

were rejected for not having been present (44a). All others

were rejected (44a).

The complaint continued: on August 1, 1960, the Board

again made assignments according to the two sets of maps.

4

No nonsegregated assignments were made except for the

children so assigned during the previous year. Two stu

dents so assigned were, however, transferred back to Negro

schools upon moving to their zone of residence. Approxi

mately 205 children, including plaintiffs, applied for re

assignment. Seven were so reassigned to the white schools

that previously had Negro children. All others continued

as assigned on the Negro map (45a).

Plaintiffs alleged compliance with the pupil assignment

law (46a). They asserted that the pattern of action by

defendant Board was arbitrary, capricious, and unreason

able, denying equal protection and due process of law

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution (46a). Particularly, plaintiffs alleged:

(a) Continued use of Negro and white maps (47a).

(b) A predetermined policy of refusing to reassign Negro

children applying to white elementary schools and refusal

to reassign Negro children to other than two junior high

schools and the high school (47a).

(c) A policy of applying criteria only to Negroes seeking

desegregation (47a).

(d) The absence of standards to judge applications for

reassignment (47a).

(e) The purported use of health standards without refer

ence to health records, the purported use of I.Q. and grade

standards without comprehension of their meaning (47a-

48a).

(f) Decision making without records or prepared in

formation and decisions on hundreds of individual children

within a period of a few hours (48a).

(g) The consistent scheduling of hearings weeks follow

ing the commencement of school (48a).

5

The complaint alleged that the administration of the

pupil assignment law was discriminatory and in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment, stating:

The North Carolina Enrollment and Assignment of

Pupils Act, Gen. Stats, of North Carolina, Sec. 115-

176 through 115-178, is unconstitutional as it exists in

actual operation for the facts establish an administra

tion directed so exclusively against a particular class

of persons as to warrant and require the conclusion

that whatever may have been the intent of the statute

as adopted, it has been applied by the public authori

ties charged with its administration and thus represent

ing the state itself, with a mind so unequal and oppres

sive as to amount to a practical denial by the State

of the equal protection of the law which is secured to

plaintiffs, as to all other persons by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Even though the law itself may be fair and impartial

on its face, since it is applied and administered by

public authority with an evil eye and an unequal hand,

so as practically to make unjust and illegal discrimina

tions between persons in similar circumstances ma

terial to their rights, the denial of equal justice is

within the prohibition of the Constitution (48a-49a).

It further alleged that the assignment law was not being

used as a desegregation plan:

Defendants have not employed the North Carolina

pupil placement statutes as a means of abolishing state

imposed racial distinctions, nor have they offered to

plaintiffs and other Negro children, by means of the

Pupil Placement Law, a genuine method for securing

attendance at nonsegregated public schools (54a).

The complaint prayed that the court enjoin the practices

complained o f :

1. Enter a temporary, preliminary, and permanent

decree enjoining defendants, their agents, employees

6

and successors from assigning plaintiffs to any school

other than the one to which they would be assigned

if they were white;

2. Enter a temporary, preliminary, and permanent

decree enjoining defendants, their agents, employees

and successors from operating a biracial school system

in Durham, North Carolina;

3. Enter a temporary, preliminary, and permanent

decree enjoining defendants, their agents, employees

and successors from maintaining a dual scheme or

pattern of school zone lines based upon race and color •

4. Enter a temporary, preliminary, and permanent

decree enjoining defendants, their agents, employees

and successors from assigning students to schools in

the City of Durham, North Carolina on the basis of

the race and color of the students;

5. Enter a temporary, preliminary, and permanent

decree enjoining defendants, their agents, employees

and successors from assigning teachers, principals and

other school personnel to the schools of the City of

Durham, North Carolina on the basis of the race and

color of the children attending the school to which the

personnel is to be assigned ;

6. Enter a temporary, preliminary, and permanent

decree enjoining defendants, their agents, employees

and successors from subjecting Negro children seek

ing assignment, transfer or admission to the schools

of the City of Durham, North Carolina, to criteria,

requirements, and prerequisites not required of white

children seeking assignment, transfer or admission to

the schools of the City of Durham, North Carolina.

7. Enter a decree ordering defendants, their agents,

employees and successors to hold an immediate meet

ing to review, on a nondiscriminatory basis, the ap

plications of plaintiffs for reassignment for the school

year 1960-61 to schools they would attend if they were

white.

7

8. Enter a judgment declaring the North Carolina

Enrollment and Assignment of Pupils Act, Gen. Stats,

of North Carolina, §115-176 through 115-178 uncon

stitutional as denying Negro children the equal pro

tection of the laws secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution (54a-55a).

In the alternative it prayed for presentation of a desegrega

tion plan (55a-56a).

Plaintiffs applied also for a temporary restraining order

and preliminary injunction against further enforced segre

gation in the Durham City school system.

After the 1960 hearings were held and all plaintiffs’

appeals from reassignment denials were rejected, plaintiffs

obtained leave to file a supplemental complaint alleging

the supervening facts (58a).

The Wheeler and Spaulding cases were consolidated

(59a). The motion for preliminary injunction was denied

“ without prejudice,” as was the Board’s motion to dismiss

(2a-3a). Answers and stipulations as to facts and exhibits

were filed (22a, 60a, 89a), interrogatories were filed, but

defendants objected thereto and a hearing was held Decem

ber 14, 1960, after which the Court required that the inter

rogatories be answered so long as school schedules were

not disrupted (3a-4a).

December 21, 1960, the case was called for trial (114a).

Because all interrogatories had not yet been answered, the

Court ordered response to certain of them to which no

response had yet been made (114a). Following trial, briefs

were submitted and the case was set for oral argument on

February 24,1961 (5a).

On July 20, 1961, Judge Stanley filed findings and con

clusions and an opinion (268a). The Court held that those

plaintiffs who had not attended the School Board hearings

8

in 1959 and 1960 had failed to exhaust their administrative

remedies and that they were not entitled to relief. The

Court further stated that it would not issue “ a decree

integrating the entire Durham School System” (289a),

stating that:

[T]he court is limited to the protection of the indi

vidual rights of those plaintiffs who exhausted their

administrative remedies prior to the institution of the

actions. As earlier noted, the United States Supreme

Court has never suggested that mass mixing of the

races is required in public schools. It has simply

required that no child shall be denied admission to a

school of his choice on the basis of race or color. There

is, of course, no objection to a number of plaintiffs

joining in the same suit, as was done in the cases under

consideration (289a).

The Court went on to say that many of defendant’s prac

tices used in 1959-60 and 1960-61 school terms were dis

criminatory and unconstitutional, including the use of a

dual system of attendance areas for elementary students

based on race (289a-290a). The Court also indicated dis

approval of the defendant’s practice of initially assigning

pupils by notices in the newspapers so late in the summer

as to make it practically impossible for pupils to complete

their administrative procedures before the opening of

school(290a).

The Court also founded an infirmity in the Board’s

administration of the law in failing to adopt criteria or

standards for considering applications for reassignment

(290a-291a). However, the Court observed that the Board

had many problems, including overcrowding, a school en

largement and construction program, and emphasized that

the Board had made what the Court termed “ a significant

and good faith start toward desegregating the schools” at

the beginning of the 1959-60 school term. The Court con-

9

eluded that the plaintiffs’ applications had not been con

sidered on their indivdual merits in that all elementary

students were denied transfers on the basis of a predeter

mined policy not to desegregate those schools, and that the

record was not clear as to why the secondary students’

applications were denied (292a). The Court said:

If there had been a scrupulous observance of the indi

vidual constitutional rights of the minor plaintiffs,

many of them would have undoubtedly been entitled

to a transfer. At the same time, by applying criteria

and standards that have received judicial approval, the

board would have likely been justified in denying many

of the applications (292a).

The Court concluded that the Board should separately

reconsider each application and report to the Court its

action on each pupil who had attended the reassignment

hearings. No injunctive relief was granted.

On August 8, 1961, the Court entered an “ interlocutory

order” (296a) directing the Board to reconsider the ap

plications of those plaintiffs who had attended the Board’s

appeal hearings in 1959 and 1960, and to file a report with

the Court within thirty days indicating its action. The

order further provided that the case be retained on the

docket and that if plaintiffs were dissatisfied with the action

of the Board they might apply for a hearing on their ob

jections. Plaintiffs excepted to this order (297a).

On August 21, 1961, the Board filed its report (298a).

The report indicated that the Board had adopted a resolu

tion stating, inter alia:

That the future use of dual attendance area maps

be discontinued effective immediately.

The report also listed certain criteria and standards to

be used in the future in assigning pupils as follows (299a-

300a):

10

(1) The relation of residence location of the pupils

to the schools to which the pupil will be assigned or

seeks reassignment to another school;

(2) The proper and most effective utilization of the

physical facilities available and the teacher load in the

school as well as the total enrollment in the school;

(3) Academic preparedness and past achievement of

the pupil;

(4) Factors involving the health and well-being of

the pupil;

(5) Physically handicapped pupils;

(6) Bona fide residence in the administrative school

unit;

(7) Morals, conduct, deportment and attendance rec

ord of pupil seeking assignment or reassignment;

(8) Efficient administration of the schools so as to

provide for the effective instruction, health, safety

and general welfare of the pupil.

At any hearing on an appeal for reassignment of a

pupil, unless the pupil or one of his or her parents or

a person standing in loco parentis is present in person,

the appeal will not be considered and it shall be con

clusively presumed to have been abandoned and with

drawn.

The Board then indicated its action and the reasons for

its action with respect to the group of plaintiffs the Court

had ordered it to reconsider. The Board reported that six

of these pupils would be granted transfers to white schools;

that ten had graduated, dropped out of school, or moved

from the city; that one was already attending a white

school, and that approximately 112 others were denied

transfers for a variety of reasons. These reasons fell into

three principal categories, e.g., distance from pupil’s resi

dence to the school involved, below average academic

achievement, and overcrowding in the schools (301a-324a).

11

Plaintiffs then filed objections to the report in which

they alleged that the assignment standards applied to this

group of plaintiffs were racially discriminatory as applied.

Plaintiffs’ objections renewed the request for injunctive

relief and for an order requiring a desegregation plan

(331a-332a).

October 11, 1961, the Court called a conference with at

torneys to discuss the most feasible way to hear plaintiffs’

objections to the Report (6a). As a result, further deposi

tions were taken which were filed with the Court on No

vember 8, 1961. At the taking of these depositions, defen

dant had refused to furnish certain documents and to

permit response to certain questions; the Court ordered

that these documents and answers be furnished (6a).

March 28, 1962, the Court called a conference of counsel

at which exhibits were identified and marked (333a).

On April 11, 1962, the Court filed a supplemental opinion

(403a).

The Supplemental Opinion made additional findings with

respect to the Board’s resolution discontinuing the use of

dual attendance area maps and the adoption of standards

for considering reassignments. The Court also found that

the Board had not made any material change in its previous

initial assignment practices (408a). The Court concluded

that the plaintiffs were attempting to maintain a class

action and that it held that they were not entitled to do so,

stating that their rights “must be asserted as individuals,

not as a class or group” (410a). Relying upon this Court’s

decision in Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (4th Cir.

1959), the Court held that plaintiffs were not entitled to

the relief they requested and that the Court had no alter

native other than to dismiss the action.

12

The opinion of the Court is in part predicated upon the

Court’s assertion that plaintiffs did not seek an adjudica

tion of their rights as individuals (409a, 410a, 413a). It

may be noted, however, that plaintiffs did seek an injunc

tion requiring that they be admitted to the various schools

they would attend if they were white students as indicated

on the white attendance area maps. (See Wheeler Com

plaint, 13a, 19a; Spaulding Complaint, 49a-53a, 54a; Plain

tiffs’ Objections to Report, 331a-332a; oral statement to

Court at final hearing, 335a-336a.)

The Court entered judgment accordingly on April 11,

1962 (414a). Notice of appeal was filed April 16, 1942

(414a).

Question Involved

The following question was raised in the complaints

(8a, 38a) and in plaintiffs’ objections to defendant’s report

to the Court (326a), and was decided adversely to plain

tiffs by the interlocutory order (296a) and final judgment

dismissing the case and denying all relief (414a).

Whether plaintiffs, Negro school children and parents,

are entitled to injunctive relief restraining the continued

operation of a system of initially assigning pupils to the

public schools on a racially segregated basis through the

use of dual racial attendance areas, and an order requiring

the school board to adopt a non-racial method of initially

assigning plaintiffs and all other pupils in the school system

and placing plaintiffs in schools without regard to their

race, where:

(1) continued use of dual racial attendance areas is

clearly established, and pupils seeking to escape the racially

segregated initial assignments are measured against re

strictive transfer standards not used in assigning pupils

generally or even in other types of transfers (such as

changes of residence transfers);

13

(2) some of the plaintiffs have eoneededly exhausted all

administrative remedies for transfer to “white” schools

and have been repeatedly rejected by the school board, first

without giving any reasons, and later upon the basis of

assignment criteria not used in placing white students in

such schools;

(3) the administrative hearings which some other plain

tiffs did not attend were futile and inadequate admin

istrative proceedings since:

(a) the board had decided before the hearings to deny

all elementary school applications;

(b) the hearings were not held for the purpose of ob

taining information from those present, all information

requested by the board was furnished, and the board merely

called the roll and then denied all requests whether the

persons were present or absent;

(c) the hearings were not held until after the school

term had commenced;

(d) the board had neither any procedural rules for con

ducting the hearings nor any agreed standards or criteria

for deciding assignment applications.

Statement of the Facts

Initial Assignm ents by Race

The Durham City Board of Education has at all times

material to this case initially assigned children to schools

on the basis of race in a racially segregated pattern.

Segregation has been accomplished and continues by a

system of assigning pupils on the basis of separate school

zone maps for white and Negro pupils (Exs. 5 and 6; 140a,

272a). These maps are used to determine the assignment

of pupils when they initially enter the system (272a) or

14

when they change residence within the City (384a-385a).

Upon graduation from elementary school, all Negro pupils

are assigned to the one all-Negro junior high (Whitted

Junior High School) (270a-271a), and upon graduation

from Whitted Junior High, all Negro pupils are initially

assigned to the single all-Negro high school (Hillside

High) (270a).

When white pupils finish elementary school they attend

one of the three white junior high schools, Brogden, Carr

and East Durham (sometimes called Holton), on the basis

of the junior high school zones (360a). All white junior

high school graduates are initially assigned to the Durham

High School (270a).2

Under this system every pupil thus lives in the zone

of one school on the Negro map and another school on the

white map. The school zones in which plaintiffs resided

on the Negro map at the time of the trial are indicated in

the answer to Interrogatory No. 1(b), see Exhibits D-l and

D-2 (240a-249a). The school zones in which plaintiffs

resided on the white school zone attendance map are in

dicated in the answer to Interrogatory 1(c), see Exhibits

E -l and E-2 (250a-259a). The nearest school serving each

plaintiff’s grade level to their residences is indicated in

the answer to Interrogatory 1(d), see Exhibits A -l, A-2,

A-3, A-4 (228a-235a) and also Exhibits F -l and F-2

(260a-267a). The last mentioned exhibits indicate that a

considerable number of the plaintiffs live closer to the

white junior and senior high schools and that a few of

them live closer to the white elementary schools.

2 School census reports used to plan for enrollments are taken

on the basis of the Negro and white populations and arranged

in terms of Negro and white schools by Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3

(131a-133a).

15

Each of the schools in the system has pupils with a varied

range of abilities, the range being determined by the nature

of the pupils living in the zone served by the various

schools. There are no schools set aside for above average

or average pupils, but rather the pupils are grouped by

ability within the schools after they are admitted (358a).

Similarly there are pupils with poor attendance records,

poor academic preparedness and achievement records and

poor conduct records in all of the schools (371a-372a).

School zones have been occasionally modified to deal with

overcrowding (360a-361a). Occasional exceptions to the

general practice of assigning pupils by zones are made for

crippled children and other unusual cases (383a).

Although approximately 15 Negro pupils are presently

attending previously all-white schools (357a) they all ob

tained such assignments by applying for changes of their

initial assignments. No Negro pupils have ever been

initially assigned to white schools (380a). The school sys

tem, which has approximately 15,000 pupils and 24 schools

(395a) is (apart from the 15) completely racially segre

gated. The Negro schools are stalled by Negro teachers

and principals and the white schools with white teachers

and principals (357a).

After the Court’s opinion of July 20, 1961, criticized the

use of dual attendance areas based on race, the Boairl on

July 27, 1961, passed a resolution stating: “ That the future

use of dual attendance area maps be discontinued effective

immediately” (299a). However, after July 27, 1961, the

Board continued to assign pupils on the basis of the old

attendance area maps. It did so with respect to all of the

entering first-grade pupils for the year 1961-62 who hap

pened to be assigned after July 27 (381a-384a). The super

intendent also used the zoning system in determining the

assignments of about 1,000 pupils who were granted changes

16

of assignment because of a change of their residence after

July 27, 1961 (3S4a-386a). The form used by pupils seeking-

transfers by reason of removal of residence is PI. Exh.

14-1962; 400a. The transfers are made on an interim basis

by the superintendent and then invariably are approved

en masse at the next Board meeting (366a-367a).

On July 27, 1961, the school Board directed the super

intendent to make a study of and to recommend new at

tendance areas (353a). No attendance areas had been pre

pared by the time the case was submitted to the Court on

March 28, 1962 (336a); they were to be completed before

the end of the term (386a-387a). Upon questioning by the

Court as to the nature of the school zones the Board was

preparing, defendants’ counsel indicated that the Board

was preparing zones only for elementary schools (337a).

The Board’s attorney steadfastly refused to commit the

Board to a program of assigning every child living in the

boundary of a particular school on the basis of a single

set of zones (336a-337a).

The Court’s Supplemental Opinion states “ that the dual

attendance area maps” have been eliminated (411a). Plain

tiffs submit that this finding is clearly erroneous, in that it

is contrary to the uncontradicted testimony by the defen

dants themselves as described above to the effect that these

zones have been used since July 27, 1961 (see 381a-387a;

cf. Finding No. 10 at 408a).

The Board ’s Reassignm ent Practices and Procedures

fo r the 1959-60 and 1960-61 School Term s

This section describes the events surrounding the con

sideration of plaintiffs’ reassignment requests prior to the

commencement of the cases. The section which follows de

scribes the procedures and standards used in reconsidering

the applications of some of the plaintiffs at the direction

of the Court prior to the 1961-62 term.

17

Prior to the 1959-60 school year no Negro child had been

assigned to a white school (134a). On August 4, 1959, and

again the following year on August 1,1960, the Board made

initial assignments by publishing a paid notice in a local

newspaper stating, in substance, that all pupils were re

assigned to the schools they previously attended except

those being graduated to another level and who were as

signed to the school which normally served the graduates

of their school. Students entering school for the first time

were assigned on the basis of the white and Negro at

tendance zone maps (see Finding No. 10 (273a) and Finding

No. 21 (278a)). These assignments had the effect of con

tinuing complete segregation in all of the Durham City

schools (except in 1960-61 for the few Negroes at predomi

nantly white schools who were continued in those schools).

In both school years groups of Negro pupils applied for

reassignment to attend white schools (225 in 1959, and 205

in 1960) (274a, 278a). In both years the School Board met,

considered their reassignment requests, and assigned seven

Negroes to three white schools {Ibid.). Each of the plain

tiffs in the Wheeler and Spaulding cases appealed the

denials of their requests within the time provided by the

Board’s rules and all were notified that hearings on their

appeals would be held by the Board {Ibid.).

In both cases these hearings were held after the school

term had begun (281a). On both occasions, some of the

adult plaintiffs appeared in person at the hearing, and the

rest appeared by counsel who presented powers of attorney

to the Board (275a-280a). The attorneys, representing both

the present and absent plaintiffs, submitted individual writ

ten statements for each plaintiff requesting desegregation

of the school system and assignments without regard to

race {Ibid.). Prior to this time, each plaintiff had filed a

2-page written application form supplying all of the infor

mation requested by the Board. (A specimen of this form

18

appears at 396a-398a; the original applications submitted

by each plaintiff are in the record as Exhibits 7 and 10.)3

3 The Board had not publicized the manner in which such ap

plication forms might be obtained (149a-150a), nor had it pub

licized that applications for change of assignment may be employed

as a means whereby the Durham City schools may be desegregated

(150a), nor has it generally distributed these forms to children

to bring home to their parents (150a). The forms may be obtained

only by an individual parent calling at the Superintendent’s office

and obtaining forms for his own children (134a). They are issued

to other persons only if they present powers of attorney from

parents (135a-136a).

The stated purpose of this restriction is to “maintain at all times

an accurate count by the secretary at the main office of pupils

desiring to enter the Durham City schools, or to change from

one school to another. . . . ” (134a). The Superintendent was

asked (135a):

“ Q. Wouldn’t that account (sic) be more accurately served

by the completed forms rather than by the forms that are

issued ?

# # # # #

“A. It is essential that both the forms given out and the forms

returned be known in the office, in order that we might be

aware of any possible changes in enrollment; that is, we have

a certain number of rooms in certain schools, we have certain

teachers employed, and in order to provide that the school

funds are used to best advantage, it is very necessary that

we have every bit of information that we can secure regarding

the possible enrollment.

“ Q. In that information furnished by the completed form,

how can you secure any information of that sort by the issu

ance of a blank form, when you issue the form, you don’t

know the school to which the child is going to apply, you

only know that when you get the completed form, isn’t that

correct? A. It is essential that we keep a record of every bit

of business that would affect enrollment.

“ Q. Now, if Mr. Pearson were to come to your office and

say, ‘I would like 25 forms for children to transfer from the

colored high school to the white high school,’ would those 25

forms be issued to him?

# # # * #

“A. They would be issued to him if he had power of attorney

to secure those forms.

“ Q. Is there a Board regulation requiring that he have

a power of attorney? A. I don’t know.

“ Q. This is your own policy? A, This is our own procedure.

“ Q. Is this a superintendent’s policy rather than the policy

adopted by a Board of Resolutions? A. This is simply the

19

At the hearing held September 21, 1959, the Board did

not ask any questions of any of the parents who were

present; it merely called the roll (215a-221a). At the end

of the roll call Board chairman thanked plaintiffs’ attorney

for expediting the proceeding, stating, “ You are very help

ful in helping us through what otherwise might have been

an unending task” (221a). Similarly, at the 1961 hearing

the Board called the roll, offered the parents who were

present an opportunity to make a statement, and recessed.

A few parents made statements asking for desegregation

in addition to the general statements made by their at

torneys (see, PL Exh. 13; see also Exh. B, 108a).

Prior to both hearings (in 1959 and 1960) the Board

members agreed among themselves that no applications for

admission of Negroes to white elementary schools would

be granted (163a, 284a).

Board members took the position that a desire for a

nonsegregated education was not an adequate reason for

granting’ transfers (157a, 182a, 189a). The Board adopted

no standards either substantive or procedural prior to

either meeting; individual Board members followed their

own consciences (160a, 162a, 171a, 177a, 284a).

Q. Were there any other such standards, or was

each individual left up to his own ideas of what was

right? A. Well—

* j {. 41. ji. 42.vp w

way it is being done and has been done except for inadvertent

cases in which someone misrepresented his being the parent,

as has happened in some cases, the forms were given out unin

tentionally.

“ Q. Now, how is your policy of securing accurate informa

tion furthered by the presentation of a power of attorney?

A. That’s a legal question that I am not in a position to

answer” (135a).

20

A. In the absence of specific formal regulations, I

would say that it was up to the individual members

of the Board.

Q. In other words, you do not know what standards

the other Board members employed in arriving at their

decisions, is that correct? A. That is correct.

Q. You follow your individual conscience, and each

of the others follow their individual consciences, and

none of them followed a standard that was formally

set down, or informally set down? A. Yes, I would

say that was followed, as was indicated by the votes

on these applications (161a-162a).

Nor were procedural rules adopted (161a).

The burden of proof at these hearings was on the ap

plicant (161a).

Certain criteria purportedly were used by individual

members. Health was one, but Board members testified that

they did not consult medical records (166a). I.Q. score was

another, but Board testimony indicated lack of familiarity

with I.Q. tests and not too much reliance was placed on this

factor (171a). Grades were another factor, but there was

testimony that the significance of grades was not fully

understood (174a).

After the 1959 hearing the Board met in executive ses

sion and immediately thereafter announced its decision

that the pupils who had not been represented by a parent

at the hearing were rejected, their failure to appear being

stated as the reason for rejection (93a et seq.). All those

pupils who were present were also rejected without any

reason being given (ibid,). Decision on each child was

made between 8:00 and about 10 p.m. (101a, 215a). The

1960 meeting was similar to the prior meeting (Pl.’s Exh.

13). At the 1960 meeting decision as to each child was made

between 9 and 10:00 p.m. (108a, 113a). In 1959 the first

time the applications were seen by the Board was at the

21

meeting (176a); the Board did not request copies prior

to the 1959 meeting (176a). No prepared information was

furnished to the Board. Verbal summaries were made by

the Superintendent (175a). In 1960 it was said: “ . . . prob

ably more preliminary discussion in the form of discussion

and study of the situation took place this year [1960]

than last year” (208a).

Those applicants who did not attend the meeting were

rejected even though in some instances excuses were given

such as emergency hospitalization of a member of the

family, attendance at a City Council meeting as City Coun

cilman (see PI. Exh. 12, 219a). Powers of attorney were

produced at the meeting for those not present, but this

was held not to be a substitute for personal appearance.

The Board has taken the position that “ a careful reading

and consideration of the purported powers of attorney,

clearly showed that they did not authorize or empower the

said attorneys or any of them to represent or appeal for

the said parents or any of them at the hearing” (75a).

However, the powers of attorney for the 1961 meeting did

specifically mention the hearing in question (PL Exh. 11),

but the absent applicants were rejected nonetheless.

Prior to and during both the 1959-60 and 1960-61 school

terms large numbers of pupils were granted transfers

routinely by the superintendent on the basis of a change of

residence (144a-148a). These “ administrative transfers”

involving white children to white schools and Negro children

to Negro schools are obtained by submitting a special ap

plication form which is different from that plaintiffs had

to submit (401a). These transfers are generally routinely

approved by the school Board after being granted on an

interim basis by the superintendent without the use of

any of the assignment criteria applied to plaintiffs (148a;

367a; 374-a-375a). No Negro child has been assigned to a

white school by moving his residence closer to it under

this change of residence transfer procedure (379a-380a).

Standards and Procedures on Reconsideration o f

Plaintiffs’ Transfer Applications

After the Court’s opinion of July 20, 1961, directed the

Board to reconsider the applications of those plaintiffs who

had attended the two appeal hearings, the Board adopted

written assignment criteria for the first time (299a-300a).

The Board then proceeded to consider each of the pupils

at meetings held July 27 and July 31, 1961. At these meet

ings the superintendent made oral presentations of facts

about each pupil (342a-349a). Prior to the meeting the

superintendent had specially employed two school adminis

trators to drive about the City in an automobile measuring

the distance between each child’s home and the nearest

Negro and white schools to a tenth of a mile (343a-345a,

377a-378a). The superintendent also had gathered informa

tion about each pupil’s scholastic record, attendance record,

health record and conduct record, and he had available

general figures indicating which schools were expected to

be overcrowded when school opened (342a-349a). In gen

eral, the Board action on these pupils, as reflected by its

report (298a-325a), followed this pattern:

(1) Negro pupils residing closer to all-Negro schools

were denied on this ground (361a).

(2) Some Negro pupils residing equal distances between

the Negro and white schools were denied transfers for this

reason (362a).

(3) Negro pupils whose academic records were not at

least average were denied transfers on this ground (362a).

(4) Several Negro pupils were denied transfers on the

ground that the white schools that they sought to enter were

23

ground that the white schools that they sought to enter were

overcrowded (see Report, 298a et seq.; cf. 331a).

(5) Poor attendance or conduct records were also men

tioned in one or two cases (304a, 322a).

Failure to meet any one of these criteria was ground

for disqualification (see Report, 298a et seq.; cf. 347a-348a).

The Negro student seeking transfer had to pass muster on

all grounds. For example, Negro pupils living closer to

white schools than to Negro schools were disqualified if

they had below average academic records or if the white

school was overcrowded. Similarly, Negro pupils with

above average academic records were denied transfers if

they lived closer to the Negro schools or if the white schools

were overcrowded. In like fashion the overcrowding cri

teria served to disqualify pupils but was not used affirma

tively to justify transfers where Negro schools were more

crowded than the white schools.4 A few examples demon

strate this. The figures given were those available to the

board in July 1961 (395a). Four Negro pupils5 attending

the all Negro Whitted School (19% overcrowded) were

denied transfers to the Carr Jr. High (8.9% overcrowded)

on the basis of overcrowding at Carr, although they lived

closer to Carr Junior High. Six Negro pupils6 assigned to

the all Negro W. G. Pearson School (12% overcrowded)

4 School capacity and overcrowding statistics as estimated on

July 27, 1961, and actual enrollment figures as of October, 1961 are

indicated in PI. Exhibit 12, 395a. There were some pupils living

outside the school district who paid tuition to attend the city schools

who were permitted to attend various public schools (356a, 379a,

402a). Thus while Negro pupils were assigned to the overcrowded

Whitted Junior High, including some who lived near the Brogden

Junior High, white pupils outside the district were allowed to

attend Brogden (357a).

6 See 319a-320a, re : Bernadette Strudwick, Cynthia Bullock,

Linda Mae Bullock, James O’Dell Daniel, Jr.

6 See 303a, re : Barbara Ann Cole, Elvin Cole, Rose Mary Cole,

Anna Louise Dunston; 312a, re : Pauline Valines and Larry Valines.

24

were denied transfers to Moreliead School (2.8% over

crowded) on the basis of overcrowding at Moreliead and

the fact that they lived about the same distance between the

two schools. Another pupil7 living closer to Morehead than

to Pearson was denied on the basis of overcrowding.

Similarly a Negro student8 living the same distance be

tween the all Negro Burton School (9.4% overcrowded) and

the white Edgmont School (undercapacity) was rejected

on residence grounds, as was another9 living equal dis

tances between Pearson (12% overcrowded) and Edgmont

(under capacity).

The residence criteria, the academic achievement criteria,

and the overcrowding criteria were all applied to these

plaintiffs in a special fashion which had not been used

before and which has not been used since plaintiffs’ appli

cations were considered. As indicated above, students are

routinely assigned on the basis of school zones when they

enter the system, when they change their residence, and

when they are graduated from one level to another. They

attend the schools in their zones without regard to their

academic records, conduct records, attendance records, or

to whether there is a closer school. This was the procedure

used to assign all other pupils for the 1961-62 school term,

including those assigned before and after plaintiffs were

considered.

Measurement of the distance between plaintiffs’ homes

and the white and Negro schools to a tenth of a mile was

a procedure that had not been used to assign pupils before

or since it was applied to plaintiffs (378a). With regard

to the academic achievement standard, it was made plain

7 See 308a, re : Larry Johnson.

8 See 318a, re : Leroy Mason.

9 See 319a, re : Wanna Pay Smoke.

25

that there were pupils attending all of the schools plain

tiffs sought to enter with similar academic records to plain

tiffs’ (872a). The same was true of the conduct and at

tendance factors {ibid.). Overcrowding has generally been

handled by modifying school zones (360a-361a), rather than

by denying pupils assignment within their zones as was

done with plaintiffs.

ARGUMENT

Introductory

The Court below held in its supplemental opinion that

“ since the minor plaintiffs have clearly demonstrated that

they are not interested in a protection of their individual

rights under the Constitution of the United States, and do

not desire that their individual rights be determined and

enforced by this court, the court is left no alternative other

than to dismiss the action” (413a). Accordingly, the Court

dismissed the case (414a).

But this statement in the opinion is erroneous. The

Wheeler complaint asked for an injunction against assign

ing plaintiffs to any school other than the one to which they

would be assigned if they were white, from operating a

biracial school system, from maintaining a dual scheme or

pattern of school zone lines based upon race and color, from

enjoining defendants from assigning students on the basis

of race, enjoining defendants from assigning teachers, prin

cipals and other school personnel on the basis of the race

and color of the children attending the school to which the

personnel is assigned, and from subjecting Negro children

seeking assignment, transfer, or admission to criteria not

required of white children seeking assignment, transfer, or

admission to schools of the City of Durham. In the alter

native, the complaint prayed for a decree directing defen

26

dants to present a complete plan within a period of time

to be determined by the Court for the reorganization of

the school system of the City of Durham on a nonracial

basis. The prayer asked that the Court retain jurisdiction

pending approval of full implementation of defendant’s

plan (19a-20a).

The complaint in the Spaulding case contained a similar

prayer (54a-55a). The supplemental complaint once more

prayed for the relief requested in the original complaint

(58a). The objections to defendant’s report contained like

prayers (331a-332a). In colloquy at the court proceedings

of March 28,1962, counsel made clear that plaintiffs sought

an order restraining defendant from maintaining a pattern

of segregation, as well as an order declaring the rights of

particular children to attend particular schools (334a-336a).

1. Plaintiffs submit that their individual constitutional

rights are infringed so long as a school system based upon

dual racial zones is maintained and they are assigned pur

suant to those zones subject to the burden of transferring

out under the pupil assignment law. Therefore, plaintiffs’

individual constitutional rights will not be secured unless

the Court enters an order requiring the desegregation of the

Durham City schools. In this sense, these pupils cannot

secure their rights without a reorganization which also

abolishes public school segregation as it affects every Negro

child in the City of Durham.

2. Beyond this, plaintiffs submit that those of them who

have “ exhausted” the North Carolina pupil assignment rem

edy are entitled to an order, under Buie 23(a)(3) of the

Federal Buies of Civil Procedure, adjudicating the rights

of Negro children similarly segregated in the City of Dur

ham. The prerequisite to maintaining this suit in the fed

eral court having been satisfied by “ exhaustion,” appellants

27

may present to the United States courts every issue in the

case—in a manner permitted by the Federal Rules.

3. Moreover, that others in the City of Durham did not

all pursue the administrative course, does not place them

in a class different from the one occupied by appellants

who did “ exhaust.” The evidence demonstrates that the

administrative remedy is nothing but a sham, a technique

employed by Durham to frustrate, not effectuate desegre

gation. For this reason persons who did not “ exhaust” are

not cut off from enjoying the consequences of federal ju

dicial relief. Those plaintiffs who did not attend the hear

ings, but were represented there by counsel, took every

reasonably necessary step to “ exhaust” their remedies, and

did so. But even if they may be held not to have “ ex

hausted,” they, as segregated public school children in

Durham, are entitled to desegregation where the remedy

is, as this one conclusively has been shown to be, merely

a mask.

I.

Plaintiffs will be denied relief to which they are en

titled as individuals so long as Durham maintains dual

racial school zones.

The record is clear that the School Board has used dual

racial zones at all relevant times in this case (272a, 273a-

274a, 278a, 290a, 359a-360a, 381a-384a). Although the Dis

trict Court in its July 1961 opinion held such racial zones

invalid (290a), and the School Board on July 27, 1961,

said it was discontinuing the use of such zones “ effective

immediately” (299a), the Court did not order the Board to

cease using such zones and the Board did not adopt a single

set of zones when it passed this Resolution (353a-354a). It

merely ordered that a study of zoning be made. At the

2 8

end of the 1960-61 school term the Board notified all pupils

on their report cards of their assignments for the 1961-

1962 school term. Pupils already in the system were as

signed initially back to the schools they previously attended,

or to the “ next higher school serving the school they had

attended” as determined by the school zoning system (359a-

360a). First grade pupils who pre-registered during the

spring of 1961 for the coming year were again assigned

on the basis of the school zones used in prior years; late

registrants, including those who were assigned after July

27, 1961 (the date when the Board resolved to “ discon

tinue” use of the dual zones), were also assigned on the

basis of the old school zones (381a-384a). Moreover, it

employed these zones in assigning over 1,000 pupils who

moved from one section of Durham to another after July

27 (384a-386a).

There are only two high schools in the City of Durham

and all Negroes are initially assigned to the Negro high

school no matter where they live (270a, 364a-365a); all

whites are assigned to the white high school no matter where

they live (365a), even though some Negroes live nearer to

the white school and some whites live nearer to the Negro

school (364a-366a). No Negroes have initially been as

signed to a white school (380a). Negroes living nearer the

white junior high and elementary schools have been and

continue to be initially assigned to the Negro schools farther

from their homes (357a, 260a, 266a).

The fundamental requirement of Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, is that school boards must effect a “ transition to

school systems operated in accordance with the constitu

tional principles set forth in [the Supreme Court’s] May

17,1954, decision.” Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

349 U. S. 294, 300 (1955). Brown also holds that while

effectuating “ transition to a racially nondiscriminatory

29

school system . . . the courts will retain jurisdiction . . . ”

Id. at 301.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7 (1958), calls for “ the

earliest practicable completion of desegregation, and . . .

appropriate steps to put their program into effective opera

tion . . . ” as well as for “ a prompt start, diligently and

earnestly pursued, to eliminate racial segregation from the

public schools.” This Circuit consistently has held that

the Board may not initially assign on the basis of dual

racial school zones and then require Negro children to

pass muster under a pupil assignment formula in order

to achieve desegregation secured to them by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution. Jones v.

School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72

(4th Cir. 1960); Hill v. School Board of the City of Nor

folk, 282 F. 2d 473 (4th Cir. 1960). In Dodson v. School

Board of the City of Charlottesville, 289 F. 2d 439 (4th

Cir. 1961), this Court held at 443:

In respect to the assignment of students to high

schools, the application of the plan is even more of

fensive to the constitutional rights of Negroes. All

white students are automatically assigned initially to

Lane High School, regardless of their place of resi

dence or level of academic achievement. All white

public high school students in the city presently attend

Lane. Absolutely no assignment criteria are applied

to them. On the other hand, residence and academic

achievement criteria are applied to Negro high school

pupils. As the plan is presently administered, if a

colored child lives closer to Burley than to Lane, he

must attend Burley High School. Moreover, even if a

Negro student does live closer to Lane, he may not

be permitted to attend it unless he performs satis

factorily on scholastic aptitude and intelligence tests

— a hurdle white students are not called upon to over

come.

30

Such administration of public school assignments

is patently discriminatory. As pointed out previously,

the law does not permit applying assignment criteria to

Negroes and not to whites . . .

More recently Judge Michie in Jackson v. School Board

of the City of Lynchburg, 201 F. Supp. 620, 629 (W. D.

Ya. 1962) held:

“ It is obvious that, if a general injunction requiring

desegregation can never be issued against a school

board or other assignment authority in a state in which

a pupil placement act is in effect, then the courts can

never perform this supervisory function which the

United States Supreme Court has told them they

should perform” [in Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U. S. 294 and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1].

These holdings are in complete accord with those of other

circuits. See, Northcross v. Board of Education of the City

of Memphis (6th Cir. No. 14642, March 23, 1962, not yet re

ported) ; Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade

County, Florida, 272 F. 2d 763, 767 (5th Cir. 1959); Man

nings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsboro County,

Florida, 277 F. 2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960).

The individual plaintiffs cannot obtain their constitu

tional rights while continuing to attend school in a segre

gated system. A system in which students and teachers

are assigned on a racial basis is such a segregated system.

In Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d 763,

766 (5th Cir. 1959), in reviewing evidence of a continuing

policy of racial segregation the court expressly noted that

continuation of the policy was evidenced by the fact that,

“At the time of trial, in the Fall of 1958, complete actual

segregation of the races, both as to teachers and as to

pupils, still prevailed in the public schools of the County.”

Moreover, in Northcross v. The Board of Education of

Memphis, supra, the complaint prayed for desegregation of

31

the school system, including the assignment of school per

sonnel without regard to race. The Sixth Circuit ordered

an injunction against operation of a “biracial school

system.” As in Northcross:

Minimal requirements for non-racial schools are geo

graphic zoning, according to the capacity and facilities

of the buildings and admission to a school according

to residence as a matter of right. “ Obviously the

maintenance of a dual system of attendance areas based

on race offends the constitutional rights of the plain

tiffs and others similarly situated and cannot be tol

erated.” Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria,

Virginia, 278 F. 2d 72, 76, C. A. 4.

# # # # #

The trial judge found that the defendants do not

operate a compulsory biracial school system. It might

he said that by reason of the transfer aspect of the

law, it is not compulsory. The real question is, Do

they maintain separate schools? The first Brown case

decided that separate schools organised on a racial

basis are contrary to the Constitution of the United

States.

The inescapable conclusion is that at the time of

the judgment in this case the schools of Memphis

were operated on a basis of “ white schools” for white

children and “Negro schools” for Negroes. The find

ings of fact that the school zone maps introduced in

evidence have no significance as evidence of a biracial

school system, and that the defendants do not maintain

a dual schedule or pattern of school zone lines, based

upon race or color, are contrary to the evidence and

clearly erroneous. As we have previously said, the

Pupil Assignment Law cannot serve as a plan to

organize the schools as a non-racial system.

More to the point, appellants certainly cannot obtain

these rights under the cloud of a pupil assignment law

which is used to impede rather than to effectuate desegre

gation.

32

The matter was recently stated most forcefully by Judge

J. Skelly Wright in Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board,

------ F. S u p p .------ (E. D. La., April 3, 1962, C. A. No.

3630, not yet reported), in ruling upon the rights of New

Orleans school children, most of whom did not participate

in the pupil assignment procedures. That case was much

like this one and the Court said:

The Board maintains that it was justified in apply

ing the pupil placement law to the desegregation order

of this court in an effort to make certain that the chil

dren applying to “ transfer” were intellectually and

psychologically acceptable in the schools they sought

to attend. The Board makes no explanation for its

failure to test all children seeking to enter the first

grade, or any other grade, in an effort to determine

whether or not they were intellectually and psycho

logically acceptable in the segregated schools to which

they were automatically assigned. This failure to test

all pupils is the constitutional vice in the Board’s test

ing program. However valid a pupil placement act

may be on its face, it may not be selectively applied.*

Moreover, where a school system is segregated,** there

* “ The admission of thirteen Negro pupils, after a scholas

tic test, which the white children did not have to take,

out of thirty-eight who made application for transfer,

is not desegregation, nor is it the institution of a plan

for non-racial organization of the Memphis sehool sys

tem.” Northcross, et al. v. Bd. o f Educ., et al., 6 Cir.,

------ F. 2d ------ (2/23/62), p. 10, slip opinion. See

also Mannings v. Board o f PuM ic Instruction, 5 Cir.,

277 F. 2d 370, 374; Jones v. School Board o f C ity of

Alexandria, Virginia, 4 Cir., 278 F. 2d 72, 77; D ove v.

Parham, 8 Cir., 282 F. 2d 256, 258. [Footnote in Judge

Wright’s opinion.]

** “ Obviously the maintenance of a dual system of attend

ance areas based on race offends the constitutional rights

of the plaintiffs and others similarly situated and cannot

be tolerated. * * * In order that there may be no doubt

about the matter, the enforced maintenance of such a

dual system is here specifically condemned.” Jones v.

School Board o f Alexandria, Virginia, supra, 76. [Foot

note in Judge Wright’s opinion.]

33

is no constitutional basis whatever for using a pupil

placement law.*** A pupil placement law may only be

validly applied in an integrated school system, and

then only where no consideration is based on race.****

To assign children to a segregated school system and

then require them to pass muster under a pupil place

ment law is discrimination in its rawest form.

*** Compare Gibson v. Board o f Public Instruction o f Dade

County, 5 Cir., 246 F. 2d 913, 914; id., 272 F. 2d 763,

767. [Footnote in Judge Wright’s opinion.]

**** “The Pupil Assignment Law might serve some purpose in

the administration of a school system but it will not

serve as a plan to convert a biracial system into a non-

racial one.” N orthcross, et al. v. Bd. o f Educ., et al.,

supra, p. 6, slip opinion. See also id., p. 8: “ Since that

decision [Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483],

there cannot be ‘Negro’ schools and ‘white’ schools. There

can now be only schools, requirements for admission to

which must be on an equal basis without regard to race.”

[Footnote in Judge Wright’s opinion.]

For these reasons, the dual zones should be abolished and

plaintiffs have standing to raise that issue—for abolition

of dual zones is the only way the individual plaintiffs may

secure their individual rights.

II.

Appellants who concededly exhausted administrative

remedies may present to the United States Courts every

issue over which they have jurisdiction in this case.

The opinion of the court below found that a large number

of the appellants “ exhausted” their administrative rem

edies. Without conceding that others did not or that “ ex

haustion” is necessary under the facts of this case, appel

lants submit that nonetheless those who “ exhausted” may

present to the United States Courts all of the issues of

racial segregation arising out of the maintenance of a dual

racial school system in the City of Durham as they affect

34

appellants and all others similarly situated, Carson v.

Warlick, supra, dealt “with the administrative procedure

of the state and not with the right of persons who have

exhausted administrative remedies to maintain class actions

in the federal courts in behalf of themselves and others

qualified to maintain such actions.” 238 F. 2d at 729. This

is consistent with the fundamental principles of jurispru

dence set forth in Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886).

Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 265 F. 2d 95,

98 (4th Cir. 1959), held that “ the District Judge might

not have felt obliged to dismiss the complaint if he had

reached the merits of the case. * * * ” Here, large num

bers of children have “ exhausted” their administrative rem

edies. They have overcome the hurdle prerequisite to

bringing action in the federal court. The door is now open

to them, as indicated in Carson and Holt, to assert rights

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution on behalf of all members of the class of citi

zens who are discriminated against in similar fashion. That

school segregation suits may be maintained as class actions

on behalf of all children whose rights have been denied

within a school district is so well settled as to be common

place. See Allen v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward

County, Va., 266 F. 2d 507 (4th Cir. 1959); Bush v. Orleans

Parish School Board, 242 F. 2d 156, 165 (5th Cir. 1957);

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Memphis,

supra; Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade

County, Florida, supra; Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798

(8th Cir. 1961), reversing Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F. Supp.

913 (E. D. Ark. 1960).

Indeed, the “ School Segregation Cases” themselves,

Brown\. Board of Education, supra, were class actions and

were regarded as such by the United States Supreme Court.

It hardly can be denied that the questions of law and fact

raised by plaintiffs who “ exhausted” are common to chil

35

dren throughout the City of Durham, nor given the large

number of plaintiffs and the exhaustive presentation of

facts in this record, could it be maintained that plaintiffs

have not adequately represented the interests of other mem

bers of the class.

III.

That children in the City o f Durham other than plain

tiffs did not pursue the administrative course does not

bar them from enjoying their constitutional right to

desegregation because the administrative remedies pro

vided by Durham are a sham.

In SJmttlesworth v. Birmingham. Board of Education,

358 U. 8. 101, the United States Supreme Court, while

affirming a District Court decision, 162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D.

Ala. 1958), which refused to hold unconstitutional on its

face the Alabama Pupil Assignment Law, adverted specifi

cally to “ the limited grounds on which the District Court

rested its decision, 162 F. Supp. 372, 384.” The District

Court (at 384) held that it was refraining from striking

down the Pupil Assignment Law on its face because that

law furnished “ the legal machinery for an orderly admin

istration of the public schools in a constitutional manner

by the admission of qualified pupils upon a basis of in

dividual merit without regard to their race or color.” The

Court presumed that the law would be so administered. It

held, however, that “ [i]f not, in some future proceedings

it is possible that it may be declared unconstitutional in

its application” (Ibid.).

These holdings are consistent with the holding of this

Circuit in Carson v. Warlick, supra, which reserved the

question of “whether [the North Carolina Pupil Assignment

Law] . . . has been unconstitutionally applied . . . ” 238

F. 2d 724, 728 (4th Cir. 1956).

36

This Court observed that the administrative remedy had

“ not been invoked” (238 F. 2d at 728). This Court warned,

however, that “ the federal courts should not condone dila

tory tactics or evasion on the part of state officials in

according to citizens of the United States their rights

under the Constitution . . . ” (238 F. 2d at 729).

Similarly, in Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780, 783

(4th Cir. 1959), this Court in assuming that the North

Carolina Pupil Assignment Law was an adequate remedy

to achieve desegregation wrote that “ [i]f there were no

remedy for such inaction, the federal court might well make

use of its injunctive power to enjoin the violation of the

constitutional rights of the plaintiffs . . . ”

This case comes to this Court upon a meticulously de

tailed record demonstrating that the North Carolina Pupil

Assignment Law does not provide a means whereby Negro

children in Durham can achieve their constitutional rights

but has been used, in the words of Carson v. Warticle, as a

“ dilatory tactic” and as an “ evasion.”

Appellants submit that while many of them did “ ex

haust” , the North Carolina procedure as applied in Dur

ham need not have been exhausted to warrant an order

requiring their admission to the schools which they would

have attended if white.

Before proceeding to a demonstration (which undoubtedly

is already implicit from a reading of the Statement of

Facts), that the Pupil Assignment Law as applied in Dur

ham is not a genuine remedy, appellants first address

themselves to the question of whether those appellants

who did not attend the administrative hearings did “ ex

haust” the so-called administrative remedies. Appellants

submit that those of their number who did not attend the

hearings were not absent from any meaningful portion of

37

the procedure. The hearings consisted merely of a calling

of the roll and a statement by appellants’ counsel that