Newark Coalition for Low Income Housing v. Newark Redevelopment Housing Authority Complaint for Injunctive Relief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Newark Coalition for Low Income Housing v. Newark Redevelopment Housing Authority Complaint for Injunctive Relief, 1989. 67c0658f-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/edf836e7-7602-45b2-8679-111567d9ae7e/newark-coalition-for-low-income-housing-v-newark-redevelopment-housing-authority-complaint-for-injunctive-relief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

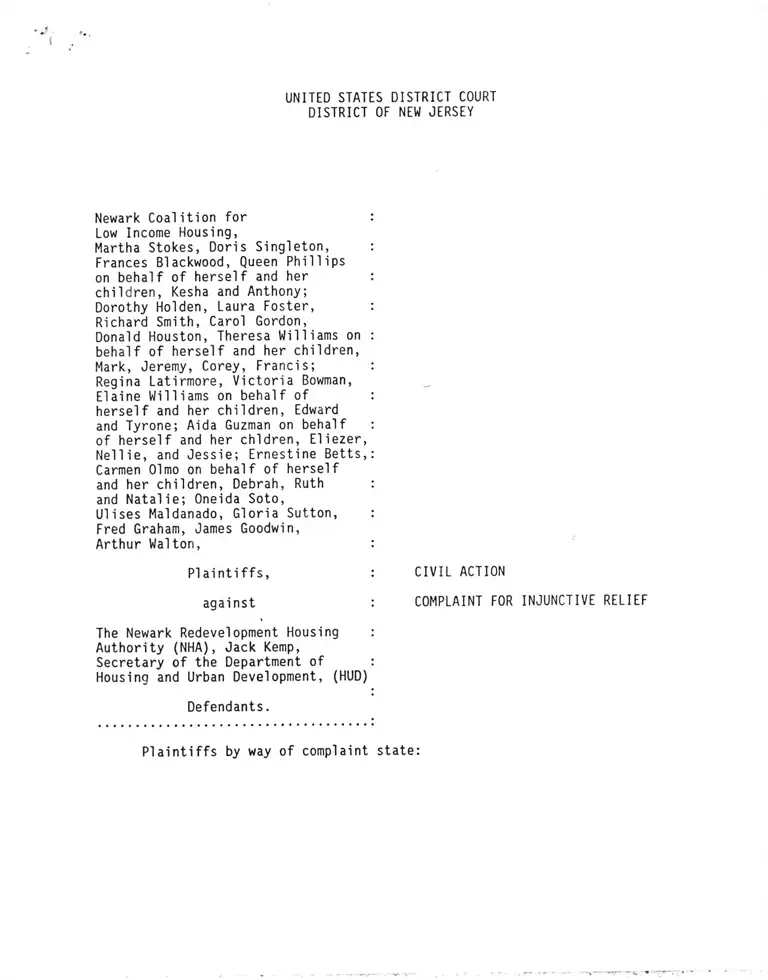

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY

Newark Coalition for :

Low Income Housing,

Martha Stokes, Doris Singleton, :

Frances Blackwood, Queen Phillips

on behalf of herself and her :

children, Kesha and Anthony;

Dorothy Holden, Laura Foster, :

Richard Smith, Carol Gordon,

Donald Houston, Theresa Williams on :

behalf of herself and her children,

Mark, Jeremy, Corey, Francis; :

Regina Latirmore, Victoria Bowman,

Elaine Williams on behalf of :

herself and her children, Edward

and Tyrone; Aida Guzman on behalf :

of herself and her chldren, Eliezer,

Nellie, and Jessie; Ernestine Betts,:

Carmen Olmo on behalf of herself

and her children, Debrah, Ruth :

and Natalie; Oneida Soto,

Ulises Maldanado, Gloria Sutton, :

Fred Graham, James Goodwin,

Arthur Walton, :

Plaintiffs, : CIVIL ACTION

against : COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

The Newark Redevelopment Housing :

Authority (NHA), Jack Kemp,

Secretary of the Department of :

Housing and Urban Development, (HUD)

Defendants.

Plaintiffs by way of complaint state:

PRF1IMINARY STATEMENT

1. This action is brought to reverse years of public housing mismanagement

by the Newark Housing Authority (NHA), to halt enormous, needless and illegal

demolition of an important public housing resource, and to insure that any

housing demolished is in fact replaced with other adequate new units, as required

by law.

The complaint is prompted by a state of affairs which includes:

explicit NHA plans to demolish at least 5,752 of an original total

of more than 13,000 units controlled by the authority, of which 816

units at Scudder Homes have already been destroyed; in furtherance

of these plans, demolition of 372 units in the Kretchmer Homes

project and at least 1,506 units in Columbus Homes has been approved

by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the

NHA is proceeding with steps to carry it out;

approximately 4,300 out of the total of NHA public housing units held

vacant and unoccupied as housing, including 1,400 units which by the

NHA's own admission were available and suitable for occupancy as of

August 1987;

abject deterioration and intolerable living conditions in many of

the housing projects operated by the NHA;

thousands of homeless and inadequately housed people in Newark alone,

and many more thousands in the surrounding area, the overwhelming

majority of whom are Black or Hispanic;

not a single new unit yet completed, or even close to being

completed, on any of the Scudder Homes sites at which public housing

2

was previously demolished by the NHA in 1987;

countless and continuing violations of federal housing

law by HUD, the agency responsible for overseeing the

nation's public housing programs, by approving NHA

proposals for demolition and furnishing other assistance

without a legal and sufficient basis, and without

insuring that the NHA had a valid one-for-one

replacement plan; by allowing the NHA to take steps in

furtherance of demolition in violation of federal law,

and by acquiescing in and failing to stop the NHA from

neglecting its projects, refusing to rent vacant units,

and generally mismanaging its affairs,

the absence of any realistic assurance that any housing

units destroyed will in fact be promptly replaced with

at least an equal number of decent, safe, sanitary, and

affordable units;

the absence of any apparent NHA intention or strategy

to preserve and rent out at least the same number of

low-income public housing units that it previously

operated, let alone to pursue reasonable steps to

increase that number of units to help meet Newark s and

the region's need for decent and affordable low-income

housing;

further racial segregation of NHA housing and the City

of Newark by the relocation of tenants displaced by the

planned demolitions, and the proposed placement of

3

replacement housing, in the racially segregated and

economically impacted Central Ward area.

2. Plaintiffs are applicants for and tenants in Newark public housing, as

well as a coalition of such individuals and organizations serving them. All

individual named plaintiffs are Black or Hispanic. The defendants are the NHA,

HUD, and the Secretary of HUD.

3. Plaintiffs seek first to halt the imminent demolition of portions of

Columbus and Kretchmer, pending a determination of their claims that demolition

would violate applicable law and that there is in any event no realistic plan

insuring one-for-one replacement housing. They also seek to halt and reverse

the NHA's pattern of causing or permitting housing conditions to deteriorate to

the point where it is tantamount to demolition, including the NHA's failure to

properly maintain and rehabilitate and to rent all available units. Finally,

plaintiffs seek to bar permanently needless demolition of other NHA housing

units.

4. Plaintiffs claim violations of the United States Housing Act, 42 U.S..C_̂

1437 et seq., the National Environmental Policy Act, 42 U.S,_C. 4331 et seg.,

Title VIII of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, 42 U . S ^ 3601 et se^, Title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000(d), and regulations and guidelines

thereunder, and the 5th and 14th Amendments to the United States Constitution,

as well as the New Jersey Constitution, the New Jersey enabling statute for

public housing authorities, N.J.S.A, 55:14A-1 et sea., and the New Jersey Law

Against Discrimination, N.J.S.A. 10:5-1 et seg.

RASTS OF JURISDICTION

5. This action arises under the laws of the United States, including

particularly the national housing acts from 1937 to 1987, 42 U ■ S_S .• 1437 et

4

sea.; Title VIII of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C., 3601 et seq._; Title

IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000(d), as made enforceable by

42 U.S.C. 1983; and the right of judicial review of federal agency actions, 5

U.S.C. 702 et seq. Jurisdiction is conferred by 28 U.S.C., 1331 and 1343(3),

and further by 28 U.S.C. 1361. Pendent jurisdiction is sought for claims

arising under the laws and Constitution of the State of New Jersey.

STATEMENT OF THE CLAIM

PARTIES

6. The Newark Coalition for Low Income Housing, c/o Vic DeLuca, 91 Darcey

Street, Newark, New Jersey 07105, is a membership organization of individuals

and groups. Individual members include the homeless, tenants residing in Newark

public housing, tenants residing in overcrowded, unsafe, or other substandard

privately owned housing, and people who have applied for but not been admitted

to NHA public housing. Groups which are members of the Coalition include, among

others: the Essex County Caucus of the New Jersey Black Issues Convention, the

Ironbound Community Corporation, the Metropolitan Ecumenical Ministries, Right

to Housing, Local 1081 of the Communications Workers of America, Apostles House

and the Kretchmer Homes Tenants Association. The Coalition's purposes and

activities on behalf of its individual tenant and applicant members include

attempting to address the problems of homelessness and the lack of affordable

housing in Newark. The Coalition seeks to end the NHA practices of allowing its

public housing units to deteriorate and remain vacant, of planning and executing

the needless demolition and disposition of public housing units that it has

allowed to deteriorate, and of failing to have an effective and realistic plan

to replace on a one-for-one basis any units which are in fact demolished. The

Coalition's individual members and those similarly situated suffer from a lack

5

of decent, safe, sanitary, and affordable housing, due in part to the practices

of the NHA and HUD challenged in this litigation.

PURI TC HOUSING TENANT PLAINTIFFS

The names and addresses of the individual public housing tenant plaintiffs

in this action are as follows:

7. Plaintiff Martha Stokes resides in the Hayes Homes public housing project

owned and operated by the NHA at 54 Boyd Street, Apt. 3F, Newark, New Jersey.

8. Plaintiff Doris Singleton resides at Hayes Homes at 322 Hunterdon Street,

Apt. 2B, Newark, New Jersey.

9. Plaintiff Frances Blakewood resides at Hayes Homes at 322 Hunterdon

Street, Apt. 4E, Newark, New Jersey.

10. Plaintiff Queen Phillips resides with her two children and a grandchild

at Hayes Homes at 322 Hunterdon Street, Apt 9C, Newark, New Jersey.

11. Plaintiff Dorothy Holden resides at the Hayes Homes Project at 322

Hunterdon Street, Apt. 9E, Newark, New Jersey.

12. Plaintiff Laura Foster resides at the Hayes Homes Housing Project at 322

Hunterdon Street, Apt. 8D, Newark, New Jersey.

13. Plaintiff Richard Smith resides at Hayes Homes Housing Project at 326

Hunterdon Street, Apt. 10D, Newark, New Jersey.

14. Plaintiff Carol Gordon resides at the Hayes Homes Housing Project with her

son, at 322 Hunterdon Street, Apt. 3C, Newark, New Jersey.

15. Plaintiff Donald Houston resides at the Kretchmer Homes Housing Project

at 101 Ludlow Street, Newark, New Jersey.

16. Plaintiff Theresa Williams resides at the Kretchmer Homes Housing Project,

97 Ludlow Street, Apt. 2D, Newark, New Jersey, with her seven children. She has

been told by the NHA that she has to move as they are going to close her

6

building down. She likes living there and does not want to move, having lived

at Kretchmer Homes for 23 years.

17. Plaintiff Regina Latimore, resides in Kretchmer Homes at 314 Dayton

Street, Apt. 4 She is chairperson of the building captains at Kretchmer, and

does not want to move.

18. Plaintiff Victoria Bowman resides with her two children in Kretchmer Homes

at 314 Dayton Street, Apt. 8H, Newark, New Jersey.

PUBLIC HOUSING APPLICANT PLAINTIFFS

The following people have applied for Newark public housing, but have not

been admitted:

19. Plaintiff Elaine Williams and her two children Edward and Tyrone are

homeless, and have resided at the Lincoln Motel in East Orange, New Jersey since

June, 1987.

20. Plaintiff Aida Guzman resides with her three children at 86 Orchard

Street, Newark, New Jersey. Her health and that of her children is suffering

because of the conditions in her apartment. Her doctor and her caseworker state

that she needs a larger, more suitable apartment.

21. Plaintiff Nereida Varela resides at 603 Broadway in Newark with her three

children.

22. Plaintiff Ernestine Betts resides with her two children, and her

grandchild at 767 S. 17th Street, Newark, New Jersey.

23. Plaintiff Carmen Olmo resides at 163 Mt. Prospect Avenue, Newark with her

three children.

24. Plaintiff Oneida Soto resides at 192 Ridge Street, Newark, New Jersey.

25. Ulises Maldanado resides at 680 North 6th Street, Newark, New Jersey.

26. Plaintiff Gloria Sutton, 59 years old, is currently living in an apartment

7

in the Stella Wright Housing Project, at 158 Spruce Sreet, Apt. 6A, Newark, New

Jersey.

27. Plaintiff Fred Graham is disabled, homeless, and at last word sleeps at

the Newark Airport.

28. Plaintiff James Goodwin is disabled and resides at the Carlton Motel.

29. Plaintiff Arthur Walton resides at the Bellevue Men's Shelter, 400 E. 30th

Street, New York, New York. He has been there since January, 1988.

DEFENDANTS

30. The defendant Newark Redevelopment and Housing Authority (NHA) is a

municipal corporation with offices located at 57 Sussex Avenue, Newark, New

Jersey 07103. It owns and operates the low-income public housing projects in

the city pursuant to the United States Housing Act. It was established pursuant

to N.J.S.A. 5 5 : 1 4 A - 1 et seg., and by Newark municipal ordinance, and under

N-J-S.A. 5 5 : 1 4 A - 7 it has the power to sue and be sued. At all times herein,

defendant NHA has acted under the color of the laws, custom, and usage of the

State of New Jersey.

31. Defendant Jack Kemp is the Secretary of HUD. The address of defendants

Kemp and HUD is the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of the

Secretary, Washington, D.C. 20410.

32. The defendant Department of Housing and Development (HUD) is the agency

of the United States government responsible for administering and supervising

the national public housing program pursuant to 42 U.S.C. 1437 et sea.

CLASS ACTION

33. Plaintiffs bring this as a class action pursuant to Fed. R.Civ. Proc. 23.

There are three classes, as follows:

(a) all applicants to NHA public housing who have not yet

8

gained admission, and who need and seek decent, safe,

sanitary, and affordable housing; and

(b) those tenants of NHA public housing projects, who (i)

seek better housing conditions and maintenance than they

now experience, (ii) oppose any needless or illegal

demolition of public housing, and (i i i) seek decent,

safe, sanitary, and affordable replacement housing of

their own choice if they are relocated because of

rehabilitation or demolition.

(c) all other homeless or inadequately housed people who

seek admission to NHA public housing.

34. Plaintiffs contend that all of the requirements of Fed. R.Civ. Proc. 23

are met, in that (i) the classes are so numerous that joinder of all members is

impossible, (ii) the key questions of law and fact are common to all members of

the classes, (iii) the claims of the representative parties are typical of those

of the classes as a whole, and (iv) the representative parties will fairly and

adequately protect the interests of the classes.

35. Prosecutions of separate actions by the class members would create a risk

of inconsistent and varying adjudications which would establish incompatible

standards of conduct for the parties opposing the classes. In addition,

adjudications with respect to individual members of the classes would as a

practical matter be dispositive of the interests of the other members not

parties to the adjudications, or substantially impair or impede their ability

to protect their interests. The party opposing the classes has acted and

refused to act on grounds generally applicable to the classes, thereby making

appropriate final injunctive relief and corresponding declaratory relief with

9

respect to the classes as a whole.

CAUSES OF ACTION

BACKGROUND

The Need for Public Housing and the Lack of Affordable

Housing in Newark

36. The defendant NHA owns more than 12,000 units of public housing in the

city, constructed pursuant to federal and state legislation to provide decent

and safe low-income housing for the poor.

37. There is a substantial need and demand for public housing units in Newark,

evidenced by an enormous waiting list of families seeking admission. This list

was found to be as high as 13,000 by HUD in 1986, and recently conceded by the

NHA itself to include over 7,000. Moreover, based on the information and

experience of plaintiffs, for at least two years the NHA has been refusing to

take new applications for public housing, except for elderly units.

38. Newark's homeless population is further evidence of the severe need for

public housing. A reported recent estimate by a Newark city agency cites some

16,000 homeless people in the city, up from an estimated 8,500 in 1984.

39. The critical shortage of housing for the poor in Newark is further

indicated by the large number of people living in dilapidated, substandard,

unhealthy and hazardous conditions, or in oppressively overcrowded situations.

The 1988-1991 Housing Assistance Plan for Newark states that there are 14,055

occupied substandard units of housing in the city.

40. There has been a steady and marked decline in Newark's affordable and

decent housing stock for many years, due to speculation, demolition,

abandonment, redevelopment, gentrification, construction of freeways, housing

10

code enforcement, building fires, and other factors. According to one expert:

"Newark's housing stock is old, rapidly diminishing, and is in so poor a

condition that it clearly qualifies as being one of the worst in the nation."

41. The vast majority of persons who are eligible for and need public housing

are welfare recipients. In Newark and Essex County, as well as the rest of New

Jersey, the fair market values of private rentals exceed the basic welfare grant

levels. As a result, many families live in apartments for which rents and

utilities constitute a disproportionate share of their income, preventing them

from having necessary funds for other essentials such as food, clothing, and

transportation. In sum, welfare recipients and the poor in general simply

cannot afford housing in the private market and still have resources for the

other basic necessities of life. In contrast, under federal law public housing

tenants cannot be required to pay more than 30% of their income for rent and

utilities. See 42 U.S.C. 1437a(I). This protection makes public housing

affordable to the poor, and for many it is the only housing they can afford.

The Racial Impact of Defendants' Conduct

42. A disproportionate number of the classes represented by plaintiffs are

minority, predominantly Black and Hispanic. Defendants' actions therefore have

a disproportionate and deleterious effect on racial and ethnic minorities, whose

opportunities for adequate housing in the private market are already restricted

due to persistent racial discrimination.

43. Defendants' actions, and particularly the Columbus and Kretchmer

demolitions, will have a devastating impact on racial minorities in several

ways. This conduct will reduce the supply of scarce low-income housing

resources to thousands of desperately needy, overwhelmingly minority homeless

and inadequately housed persons. It will remove thousands of apartment units

11

from housing sites with particular social and functional value to low-income

minority households. Finally, these plans will increase segregation in the city

and the NHA by relocating displaced tenants and placing new replacement housing

in the racially segregated and economically impacted Central Ward, and by

removing thousands of units from more integrated areas.

The NHA's Other Activities to Reduce Low-Income Public Housing

44. In the face of this huge need for safe and decent low-income housing in

Newark, the NHA has taken and continues to take numerous steps to reduce the

public housing supply. Specifically, the NHA has taken the following actions.

(a) It has undertaken an extensive plan for demolishing

existing NHA housing units in 39 mid-and high-rise

buildings, targeting the eventual destruction or

disposition of at least 5,752 out of an original 13,133

units, without any provision to create at least one new

unit for each unit destroyed; current plans call for

replacement of only a fraction of the units which have

been or will be destroyed. This is the most sweeping

demolition plan of its kind in the country.

(b) The NHA has actually demolished 816 units.

(c) The NHA has actively taken steps to prepare the way for

more demolitions by vacating still other buildings,

which could be utilized to provide public housing. Such

steps include (i) relocating tenants; (ii) refusing to

rent units in targeted buildings that become vacant and

available; (iii) holding units in buildings not targeted

for demolition vacant, to be used to relocate tenants

12

from buildings that it hopes to demolish, instead of

renting them to Newark's homeless or inadequately housed

people who have applied for public housing; (iv) failing

to properly maintain, rehabilitate, and manage

individual units, buildings and entire projects in a

decent, safe, and sanitary fashion, creating intolerable

living conditions which discourage existing tenants and

encourage them to leave, in turn creating more

vacancies; and (v) failing to properly secure vacated

buildings, causing conditions to further deteriorate.

(d) The NHA has actively planned for and pursued the sale

of project sites, thereby reducing the supply of

available land and housing, without an equivalent gain

in land, units, or compensation.

45. The specific history of the NHA's demolition applications, approvals, and

actual destruction is as follows:

(a) Scudder Homes: In September, 1985, HUD approved the

demolition of 816 out of the project's 1,428 units.

Pursuant to this approval, these units were demolished

during the period May through November, 1987.

In August, 1987, the NHA applied for permission to

demolish an additional 612 units. HUD returned this

application unapproved because it failed to comply with

the provisions of the Housing and Community Development

Act (hereafter the 1987), which included, inter alia,

important additions to the federal statutory

13

requirements concerning the demolition and disposition

of property. 42 U.S.C. 1437p.

(b) Hayes Homes: In September, 1985, HUD approved the

partial demolition of four buildings, an elimination of

328 out that project's 1,458 units. There has been no

demolition pursuant to this approval.

In August, 1987, the NHA abandoned the above plan, and

applied for permission to totally demolish all ten

buildings at Hayes Homes, combining it with the second

Scudder application described in (a) above: As

indicated, HUD returned this application unapproved.

(c) Kretchmer Homes: In September, 1985, HUD approved the

demolition of three buildings containing 372 units.

There has been no demolition pursuant to this approval,

but the NHA is taking steps to carry out the demolition,

including securing the necessary approvals from HUD and

bidding and executing contracts for the work.

(d) Columbus Homes: In November, 1988, HUD approved the

demolition of 1,506 units at Columbus Homes. It also

approved NHA's "plan" for replacement housing.

(e) Summary - planned demolition for Scudder, Haves,

Kretchmer, Columbus:

The NHA has received approval to demolish 3,022 units,

(including the 816 already demolished). It also sought

approval to demolish an additional 1,742 at Hayes and

Scudder, for a total planned demolition of 4,764, in

14

the application that was returned to the NHA by HUD. In

contrast, the NHA has received a firm commitment of

funding for only 519 units of new construction. Of

these, 101 are at the site of the Hayes/Scudder

demolition, 124 originally scheduled for the

Hayes/Scudder and currently have no site, 100 are

located at other sites in the Central Ward, and 194

represent HUD's commitment as a part of the first year

of one-for-one replacement for Columbus Homes.

Further, in response to the NHA "replacement plan for

the Columbus demolition, HUD has also agreed to commit

funding for an additional 1,312 units, subject to

appropriations."

The net loss of units., in these few projects alone, even

if the additional 1,312 units were realized,1 will be

2,919, a staggering loss of housing capacity.

(f) Additional contemplated demolition and disposition.

In June, 1987 the NHA filed a "Comprehensive

Modernization" plan. This announced that "five family

high-rise projects comprised of thirty-nine buildings

should be demolished and replaced by townhouses or sold

to private developers." In March, 1988, a second such

comprehensive modernization plan proposed elimination

1 The commitment of 1,506 replacement units for Columbus Homes over a six

year period, is "subject to appropriations." Given the fact that no replacement

units are included in the FY 1990 Bush budget, and given the budget deficit,

the reality of these replacement units is tenuous.

15

of at least 5,252 units, representing several hundred

units at Kretchmer and Walsh in addition to those noted

above. The comprehensive plans also suggest the

possibility of losing still more units, through a

possible disposition (i.e., sale) of all of Walsh. The

number of lost and unreplaced units would thus rise to

at least 3,421. As noted, this is the most sweeping plan

of its kind in the history of public housing in this

country.

FIRST CAUSE OF ACTION - COLUMBUS HOMES DEMOLITION

46. On July 25, 1988, the NHA applied to HUD for approval to demolish all

eight buildings at Columbus Homes, comprising 1,506 units. On October 28, 1988,

the Secretary of HUD approved this application. This approval violated

42 U .S .C . 1437p and other applicable law in the following respects.

(a) Based upon the information before the Secretary in the

Columbus Homes demolition application, there was not

sufficient evidence that Columbus Homes is so obsolete

as to physical condition, location or other factors as

to make it totally unusable for any housing purposes (42

U.S.C. 1437p(a)(1)); in fact part of Columbus is

currently being used for housing, and housing experts

have formulated plans under which other portions of

Columbus could be used again for housing as well.

(b) There are reasonable programs of modifications which are

feasible to return Columbus Homes or portions thereof

16

to useful life as housing (42 U.S.C. 1437p(a)(1)).

(c) The application from the NHA for the demolition of

Columbus Homes was not developed "in consultation with"

affected Columbus tenants or tenant groups, as required

by 42 U.S.C. 1437p(b)(1), but rather was developed by

the NHA, and was first disclosed to said tenants only

after the application was submitted to HUD. The

substance of the application was not changed in any way

after the subsequent disclosure and a meeting with

tenants, despite their presentation of a petition in

opposition to the demolition signed by many of the

tenants.

(d) Not all tenants to be displaced as a result of the

demolition are in fact being relocated to other decent,

safe, sanitary, and affordable housing of their own

choice, as required by 42 U.S.C. 1437p(b)(2); the

choices are defined and limited by the NHA.

(e) The one-for-one housing replacement plan developed by

the NHA and approved by HUD is defective and fails to

meet the requirements of 42 U.S.C. 1437p(c), and

regulations, guidelines and other rules promulgated

thereunder. The plan's failings include but are not

limited to the following:

(i) It fails to specify any of the sites upon

which the replacement housing will be built,

as required by HUD Notice PIH 88-5(b)(5) and

17

53 Fed. Reg. 30,989, to be codified at 24

C.F.R. 970.11(h).

(ii) It fails to assess the suitability of the

replacement sites, as required by 24 C.F.R.

970.11(h), and specifically does not contain

an assessment as to whether or how these

undescribed replacement sites comply with

applicable HUD Site and Neighborhood

standards relating to full compliance with

applicable non-discrimination laws,

including not being in areas of minority

concentration (unless certain exceptions

apply), promoting greater choice of housing

opportunities, and avoiding concentration

of tenants in areas with a high proportion

of low-income people, as required by 24

C.F.R. 941.202(b), (c), and (d), and 53 Fed.

Reg. 30,989, made applicable by 24 C.F.R.

970.11(h).

(iii) It fails to include the required reserved

percentage of units accessible to

handicapped people, as required by HUD

Notice PIH 88-5(e), and 24 C.F.R. 970.11(i)

and 8.25.

(iv) Its schedule fails to include a provision

that construction of all replacement units

18

will in fact be completed within six years

of demolition, as required by 42 U.S.C.

1437p(b)(3)(D) and 24 C.F.R. 970.11 (d). In

fact, there is not even a date specified for

the beginning of implementation, as required

by the regulation. Both HUD's own

construction standards (setting out a norm

of 30 months from date of funding to start

of construction and made a matter of statute

in Section 5(k) of the 1987 Act 42 U.S.C.

1437c(k)), and even more importantly the

NHA's own abysmal construction history,

suggest that these replacement units cannot

possibly be completed during the six-year

period set by statute. HUD data shows that

NHA has taken on average an astonishing ten

years to complete what little new

construction it has undertaken since 1977.

(v) It depends on a commitment by the Secretary

of HUD to provide replacement units. This

commitment must be considered inadequate as

a matter of law since HUD itself proposes

no funds specifically for new construction

in the latest FY 1990 budget, indicating

impossibility if not outright bad faith.

Further, the "commitment" is fatally vague:

19

there is no indication of what specific

dollar amount is actually "committed," what

would actually be spent by HUD for this

project at various appropriation levels,

what priority would be assigned the Newark

project as compared with other proposals,

or even when the money would become

available.

(vi) It fails to include any specifics as to how

the same number of individuals and families

will be provided housing after demolition,

as required by law. (42 LKS_X.

1437p(b)(3)(E))

(vii) It fails to include specifics as to the

requisite provision for payment of actual

tenant relocation expenses, or assurances

that (A) the new rents paid by tenants will

be within allowable amounts (42 U .S .C_̂

1437p(b)(3)(F)) (the Brooke Amendment), or

that (B) no unit will be demolished until

the tenant of that unit is in fact relocated

to a unit which is decent, safe, sanitary,

affordable, and to the extent practicable

of that tenant's own choice.

(viii) It fails in general to provide any

description or detail sufficient to support

20

a conclusion that the plan is credible or

realistic, as required by 42 U.S.C.

1437p(b)(3); among the omissions are (A)

any mention of the number, source and amount

of any rent supplements to be applied to the

units, (B) any indication of the state of

working drawings or other palpable plans

for the new construction, (C) any indication

as to what approvals and permits are

required, which have been obtained, and when

the remainder may be expected, (D) what

specific contingency plans for alternative

funding exist if HUD is unable to meet its

commitment in any year, and (E) specifically

how the NHA plans, to overcome past

difficulties, whether caused by management

problems or other factors, which have

prevented it from constructing or

rehabilitating units in a timely fashion.

47. As the Columbus demolition application makes clear, the destruction of the

buildings is just the first step in a planned disposition of the property. The

demolition is simply designed to clear the land so that it is more attractive

for private developers. Indeed, before NHA had even filed its demolition

application for Columbus, it had already entered into a contract with a private

party (a firm led by former Mayor Kenneth Gibson and Peter Macco) to sell the

cleared site. Nonetheless, the planned disposition was not part of the

21

demolition application, even though both the statute and HUD regulations have

distinct criteria guiding the Secretary's consideration of whether to approve

the proposed disposition of a public housing site.

48. There is no indication that the planned disposition would meet the

requirements of 42 U.S.C. 1437p(a)(2), nor did the Secretary of HUD so find. For

defendant HUD to have approved a demolition of a project when it was expressly

part and parcel of a planned disposition of that project, without any

consideration or decision whether the integrally-related disposition itself

satisfied the statute and regulations thereunder, was a serious abuse of

discretion and violation of applicable law. Without evaluating the demolition

and disposition as an integrated scheme, there is no basis to judge, inter al ia,

the effect on overall availability of public housing land and units in Newark,

just one part of the evaluation required by law.

SFCOND CAUSE OF ACTION - KRETCHMER HOMES DEMOLITION

49. Demolition of three buildings at the Kretchmer Homes housing project of

the NHA was approved by the Secretary of HUD on September 20, 1985. These

buildings have not been demolished. This approval violated 42 U.S.C. 1437p(a),

as it existed at the time of the approval, in that the Kretchmer Homes buildings

were not obsolete, reasonable modifications would return the buildings to useful

life as housing, and the other statutory criteria were not met.

50. No plan of one-for-one replacement of the housing units to be destroyed

was submitted with or was a part of this application, nor has such a plan ever

been submitted.

51. Subsequent to HUD's approval, the 1987 Act became law. This statute

strengthened part (a) of the prior law by requiring that a showing of both

22

obsolescence and non-feasibility of modification or repairs was necessary before

the Secretary could approve a demolition or disposition; the prior statute

required a showing of either obsolescence or non-feasibility. Neither

obsolescence nor non-feasibility is present in the case of Kretchmer Homes.

Furthermore, the 1985 application was approved partly on the basis that

demolition of a portion of Kretchmer would help preserve the rest of the

project. In fact, as revealed in the NHA'a most recent plans, all of Kretchmer

is slated for demolition, no portion is to be preserved, and this ground for

approval is invalid.

52. Among the 1987 Act's other provisions is a prohibition against HUD

furnishing assistance to or approving an application for demolition unless there

is a one-for-one replacement plan which meets the requirements of the law. 42

U.S.C. 1437p(b). Since the effective date of the Act in February 1988, HUD has

issued a number of approvals of contracts and actions concerning the planned

demolition of the three Kretchmer buildings, and authorized the expenditure of

funds in connection with demolition, without requiring a one-for-one replacement

plan, in violation of the 1987 Act.

53. The 1987 Act also bars housing authorities from taking any action in

furtherance of demolition or disposition without obtaining the approval of the

Secretary and satisfying the newly amended 1437p(a) and (b), the one-for-one

replacement plan provision. The NHA has taken numerous actions since the

effective date of the 1987 Act in furtherance of the planned demolition at

Kretchmer, without having satisfied the one-for-one replacement requirement, in

violation of 42 U.S.C. 1437p(d).

54. At the time of the Kretchmer demolition approval in 1985, HUD had in

effect a regulation requiring one-for-one replacement of any demolished units,

23

which it arbitrarily and improperly purported to "waive". The regulation

originally appeared at 44 Fed. Reg. 65368, codified at 24 C .F.R,_ 970.6. The

one-for-one requirement then applicable must be applied to Kretchmer, as the

"waiver" was without legal basis.

THIRD FOUNT - ACTIONS IN FURTHERANCE OF

DFMOI TTTON AT OTHER PROJECTS

55. Since the effective date of the 1937 Act, the defendant NHA has taken, and

continues to take, numerous steps in furtherance of demolition at other high-

rise buildings that it operates, including the remaining buildings at Kretchmer,

Scudder, and Hayes not covered by the NHA's 1985 demolition application, as well

as buildings at Walsh Homes.

55. There has been no HUD approval of demolition or disposition for any of

these other buildings, nor are any of these buildings the subject of a pending

demolition application.

57. NHA's actions in furtherance of demolition without HUD approval include

preparing the way for more demolitions by vacating these other targeted

buildings, which could and should be utilized to provide public housing, by

taking the actions described in paragraph 44(c) above. For example, the NHA has

recently begun wholesale relocation of tenants from the Kretchmer Homes building

at 97-101 Ludlow Street in Newark, to empty the building for demolition, even

though there is no HUD approval and no one-for-one replacement plan.

58. These actions in furtherance of demolition, without an approved demolition

application satisfying legal requirements, constitute continuing violations by

the NHA of 42 U.S.C. 1437p(d), to the great injury of plaintiffs and members of

their classes that they represent. By taking units and entire buildings out of

public housing rental, these actions also constitute de facto or constructive

24

demolition without HUD approval, and thereby violate 42 U-S.C. 1437p.

59. Defendant HUD has refused to halt these illegal NHA actions in furtherance

of demolition, thereby violating its responsibilities under the 1987 Act.

60. Within the past two years the NHA has embarked on a substantial

modernization program at 97-101 Ludlow Street of the Kretchmer Homes. There has

been substantial modernization of the apartments and common areas of those

buildings. 24. C.F.R. 968.6 requires that for each modernization program there

must be an amendment to the Annual Contributions Contract (ACC). It further

provides that the amendment shall require the low-income use of modernized

housing for at least 20 years from the date of the modernization. The

plaintiffs are third party beneficiaries of the ACC. The NHA's plans to

demolish the modernized buildings, and the emptying out of those buildings

within less than a year of the modernization, and indeed before it has been

completed, denies plaintiffs their rights under the ACC, and under 24 C.F._R...

968.6.

FOURTH CAUSE OF ACTION- MISMANAGEMENT OF PUBLIC HOUSING

61. The defendant NHA has mismanaged in a most serious and fundamental fashion

the public housing under its control. A 1984 HUD audit stated:

The NHA has not developed adequate management procedures for

overseeing its maintenance program, has not made maximum use of

available resources, and has not operated its maintenance programs

in an efficient and economical manner. As a result, the housing

stock continues to deteriorate, leaving 4,355 unoccupied units which

represent 34 percent of the 12,904 units.

62. This mismanagement includes but is not limited to the actions and failures

set forth below.

25

(a) The NHA has caused or allowed conditions in the high-

rise buildings to deteriorate over a long period, and

consequently a large number of units are not decent,

safe, or sanitary, as required by the United States

Housing Act, regulations thereunder, and the Annual

Contribution Contact between the NHA and HUD.

(b) The NHA has not kept the buildings secure, and in most

there is the constant threat of crime and physical harm.

(c) Thousands of apartments have been held vacant for

several years, when they could and should have been

rented, denying needed housing to low-income people in

Newark. The 1984 HUD audit found:

The... percentage of increased vacant units indicate

that instead of making decent, safe and sanitary housing

units available to low-income families, as required by

the ACC, the NHA has continually allowed units to become

unavailable for occupancy. In fact, they have

intentionally kept them out of service.

(d) As of December 1, 1987, there were at least 4,302

vacancies, a vacancy rate of at least 37%.

(e) Because of the NHA's inability to manage public housing

properly, and its deliberate strategy of creating

vacancies in high-rise public housing as a prelude to

demolition, vacancies in Newark's public housing have

risen dramatically since 1979. According to a variety

of NHA statistical reports over the years, the vacancies

have risen from 587 in 1978 to 5,547 in 1987, a rise of

26

945 percent.2 The NHA vacancy rate is the highest of

any major public housing authority in the United States.

(f) Notwithstanding these vacancies, the NHA has continued

to seek and receive operating subsidies from HUD for

such vacant units, thereby building up excessive

operating reserves, while also allocating excessive

amounts to central administration, instead of utilizing

the money to repair and maintain some of the vacant

units so that they would be decent, safe, and sanitary

and in proper condition for re-renting. Furthermore HUD

has found that the NHA ran up excessive administrative

expenses for modernization projects, while failing to

carry out the modernization itself.

(g) HUD audits and reviews during the 1980's have detailed

a long list of continued deficiencies in NHA management,

and it also has been designated an "Operationally

2 Fiscal Year Total Vacancies Percentage Increase Since 1978

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1986

6/30/1987

9/30/1987

12/1/1987

* (After the demoliti

587

762

1,030

2,180

2,943

3,790

4,355

5,285

5,381

5,547

4,302

i of 813 vacant units

30%

75%

271%

401%

546%

642%

900%

917%

945%

732%*

in the Fall of 1987)

27

Troubled" housing authority by HUD.

(h) The NHA has proceeded with plans to dispose of NHA-owned

property, such as the Columbus Homes site, even though the

land is badly needed for low-income housing, the reasons for

the sale are not related to the goals of the NHA in preserving

and expanding low-income housing, and an equivalent or greater

amount of low-income housing will not in fact result from the

sal e.

(i) The NHA has taken an astonishing average of nearly ten

years from approval and funding by HUD just to start

badly needed construction of the new housing units.

(j) As repeatedly documented by HUD, the NHA has failed to

utilize modernization funds awarded to it for existing

units in a timely manner, frequently exceeding HUD's

three-year guideline for completion of modernization

projects, and leading to the recapture by HUD of at

least $5 million of unexpended funds. In 1984, a HUD

audit found that since the federal modernization program

began in 1974, HUD had authorized NHA expenditures of

$145 million, but the NHA had spent only $76 million,

leaving $69 million unspent. More recent reviews by HUD

echo the same theme. This money, if spent, could have

had an enormously beneficial effect on the deplorable

conditions in NHA housing projects.

(k) The NHA's practices concerning admissions and the

required maintenance of waiting lists have been

28

criticized by HUD. Combined with a recent reported

practice of refusing to take applications from families,

these practices illegally harm people seeking admission

to public housing.

(l) The NHA has failed to seek or obtain from HUD permission

to use high-rise units that the NHA deems unsuitable for

families as housing for single individuals. Such

single-person usage would be permissible if approved by

HUD.

(m) NHA's failings as cited above have in turn made it less

able to secure other federal funding that might have

been available.

63. The 1984 HUD audit concluded:

[T]he NHRA's primary responsibility is to provide decent, safe and

sanitary housing in an efficient and economic manner. We believe

that the NRHA has failed in this regard and has not, considering the

conditions found, demonstrated the capacity to effectively maintain

the projects, implement its long-range plans and market the units

accordingly.

64. All of the foregoing constitute serious mismanagement of the NHA and its

resources, thereby needlessly denying potential housing opportunities to low-

income people in violation of the letter and spirit of the United States Housing

Act, 42 U.S.C. 1437 et seg-> and regulations thereunder, as well as the

obligations of the NHA under the Annual Contributions Contract with HUD, of

which plaintiff tenants and applicants are third-party beneficiaries, and the

duties and responsibilities of public housing authorities under the letter and

spirit of the New Jersey housing authority enabling statute, N.J._S,/L 55:14A-1

et seq.

29

65. Notwithstanding NHA's continued severe problems, defendant HUD has failed

to take sufficient affirmative remedial measures, continued to grant

unconditioned operating subsidies and other funds, and granted various other

approvals. In thus allowing NHA to carry on with its mismanagement and the

resulting loss of low-income housing opportunity in Newark, HUD has abused its

discretion and failed to meet its responsibilities of regulation and supervision

of public housing authorities, thereby violating its duties under the United

States Housing Act.

FIFTH CAUSE OF ACTION

DISCRIMINATORY RACIAL EFFECT OF NHA AND HUD ACTIONS

66. A disproportionate share of the plaintiff classes -- Newark s homeless

and inadequately housed applicants for public housing, on the one hand, and

Newark's public housing tenants, on the other -- are members of racial and

ethnic minority groups. Many are disabled. The share of racial and ethnic

minorities, and disabled people, is significantly higher in the plaintiff

classes than in Newark's population as a whole.

67. As a result of this disproportionate representation, the entire range of

defendants' actions described in this complaint, which deny plaintiffs and their

class members decent, safe, sanitary, and affordable housing, have an adverse

and disproportionate impact on these racial and ethnic minorities and the

di sabled.

68. The NHA's proposed demolition of Columbus and Kretchmer will result in the

relocation of Black and Hispanic tenants into more racially segregated,

virtually all minority-occupied public housing in Newark's virtually all

minority Central Ward. Over 70% of the units provided for the relocation of

30

tenants displaced by the demolitions are in the Central Ward.

69. The NHA's proposed demolitions also will result in the placement of new

replacement housing in the Central Ward. While noted the Columbus replacement

"plan" mentions nothing about sites for replacement units, the City of Newark's

most recent Housing Assistance Plan indicates that 32 of the approximately 44

acres of land listed as available for the placement of replacement housing units

are in the Central Ward.

70. The NHA proposed demolitions of Columbus Homes and Kretchmer Homes will

results in further racial segregation in the city and in the NHA's housing.

71. The NHA has knowledge of the segregative impact of its proposed

demolitions, as well as of the effect that its failure to fill vacant units has

on racial minorities.

72. The NHA's conduct violates plaintiffs' rights under Title VII of the Fair

Housing Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. 3601 et seg^ and 24 C.F.R., 941.202(c)(1); Title

VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000d et seg, and 24 C ^ R ^

1.4(b)(2)(i); the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the United

States Constitution; and the New Jersey Law Against Discrimination, N.J .S.A^

10:5-1 et seq.

73. Defendants Secretary of HUD and HUD, in approving the demolitions of

Columbus and Kretchmer, have failed to properly weigh the question of racial

impact, investigate and determine the social factors involved in the approved

housing choice, or weigh appropriate and less discriminatory alternatives.

74. The conduct of the federal defendants violates HUD's affirmative

obligation to further the purposes of Title VIII of the Fair Housing Act of

1968, 42 U.S.C. 3608(e)(5), as well as its obligations under Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000d et seg., and the Fifth Amendment to

31

the United States Constitution.

75. Furthermore, defendants conduct, which has the effect of making low-income

housing resources unavailable to a plaintiff class disproportionately consisting

of disabled and handicapped people violates Section 504 of the Rehabilitation

Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. 794, and regulations promulgated thereunder, and the New

Jersey Law Against Discrimination, N.J.S.A. 10:5-1 et seg.

SIXTH CAUSE OF ACTION - FAILURE TO

ASSFSS ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

76. The NHA has embarked on a course of demolition and disposition which, if

completed, will result in the destruction of more than 5,000 public housing

units. Despite its awareness of the full scope of this destruction, HUD

approved the demolition proposals for Kretchmer and Columbus Homes without HUD

and NHA preparing an environmental impact statement (EIS), or indeed, as far as

plaintiffs are aware, without HUD preparing or publishing locally a finding of

no significant [environmental] impact (F0NSI).

77. For all of its projects not categorically excluded by applicable

regulations, HUD must perform an initial environmental assessment to determine

whether the project will have a significant environmental impact. This

requirement is imposed on HUD by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA),

42 U.S.C. 4331 seg.

78. Demolition or disposition of public housing is plainly a major federal

action under NEPA. Given the scope of the proposed NHA demolition and

disposition, well over 2,500 units, those actions are presumed to have a

significant environmental impact under 24 C.F.R. 50.42, and in fact will have

such an impact. Failure to prepare, publish, and receive comment on an EIS

violates 24 C.F.R. 50.47.

32

79. This required environmental assessment must include determination of the

effect of the proposed demolition on the quality of urban life, including the

effect on the low-income housing supply.

80. HUD approval of the demolition of Kretchmer and Columbus must therefore

be set aside, and any steps toward demolition enjoined, until a satisfactory

environmental assessment is made, an EIS prepared, and public comment received

and considered.

SFVFNTH CAUSE OF ACTION

FAILURE TO TAKE REASONABLE STEPS TO

PRFSFRVE AND EXPAND THE SUPPLY OF LOW-INCOME HOUSING

81. Defendant NHA's cumulative actions as set forth in this complaint have

reduced significantly the supply of decent, safe, sanitary, and affordable low-

income housing in Newark, compounding the desperate shortage of such housing in

the private market.

82. Defendant NHA has also failed to take all reasonable steps within its

power to preserve and increase the supply of such housing, such as securing and

utilizing in a timely fashion all available federal new construction and

modernization funding.

83. As a result, thousands of Newark residents have been and are denied a

housing opportunity that would otherwise be available, and that the NHA was

created to provide.

84. Individually and collectively these actions and failures to act constitute

a pattern and practice of reduction and destruction of the supply of affordable

housing for low-income people, and violate the duties and responsibilities of

the NHA as set forth in the public housing authority enabling legislation,

33

N.J.S.A. 55:14A-1 et se^. Any municipal public housing authority draws its sole

power to act from this enabling statute. A municipal public housing authority

is an instrumentality of municipal government, a public entity exercising

governmental functions. As a governmental entity, the NHA must conduct itself

in a way that is consistent with and furthers the purposes of that legislation.

85. Under the New Jersey Constitution, public housing authorities, just as

municipalities themselves, must utilize their delegated powers in a fashion that

is consistent with and furthers the general welfare. The NHA's actions to

reduce the housing supply affordable to low-income people, to fail to rent and

utilize available vacant units, and to fail to take reasonable steps to increase

the supply of public housing are in derogation of the general welfare, and

therefore violate the NHA's constitutional responsibilities. The actions of the

NHA also constitute a pattern of arbitrary and capricious behavior by a public

body.

85. All of the foregoing violations arise out of the same actions and,

failures to act which give rise to plaintiffs' federal claims, and therefore

support and require the exercise of pendent jurisdiction, intervention and

remedial action by this Court.

PLAINTIFFS' IRREPARABLE HARM AND HARDSHIP

87. Because of their homelessness, or being trapped in unsafe, substandard,

overcrowded or other inadequate housing conditions, plaintiffs and the classes

they represent are suffering irreparable harm and hardship for which there is

no adequate remedy at law. Defendants actions, as described above, have

significantly reduced the supply of affordable housing in Newark, and thereby

caused irreparable harm and hardship to plaintiffs and the members of their

cl asses.

34

Specifically, this harm and hardship has at least the following aspect

(a) Homelessness is an unbearable situation, and subjects

people to life-threatening conditions, with severe

adverse effects on their physical and mental health.

(b) Homelessness has been identified by the Governor's

Committee on Children's Services Planning as a major

cause of family break-up, resulting in DYFS placement

of children in foster care.

(c) People are forced to live on the streets, or in

abandoned buildings, seriously overcrowded or

substandard housing, dangerous homelessness shelters,

or crowded, squalid welfare hotels.

(d) Many families who are able to maintain their own private

apartments are forced to spend an inordinate amount of

their income on rent, and therefore do not have money

to meet other vital needs, such as food for their

children. This inadequacy of resources is the major

cause of the widespread hunger in New Jersey, and a

resulting "new phenomenon of children who are growing

up chronically hungry," according to the Governor's

Committee. Chronic malnutrition, in turn, retards

physical and mental development.

(e) This homelessness and inadequacy of housing adversely

affect the physical and mental health of adults and

children, as well as the ability of children to develop

and perform in school, thus limiting their opportunities

35

for the rest of their lives.

(f) The proposed and imminent demolition of Columbus and

Kretchmer would remove for many years a potential and

essential housing resource that could be made available

to individual plaintiffs and members of their classes.

PRAYFR FOR RELIEF

Wherefore plaintiffs request that this Court:

A. Issue an immediate temporary order

restraining defendants from taking any

additional action in furtherance of the

demolition of Columbus and Kretchmer Homes

pending final judgment in this action.

B. Certify this matter as a class action;

C. Order the NHA to rent immediately all

available vacant units;

D. Issue a preliminary and permanent injunction

barring the NHA from taking any further

steps in anticipation of or to carry out

demolition or disposition of publ ic housing,

unless and until all legal obligations under

federal and state law have been satisfied.

Such prohibited steps include but are not

limited to:

1. Relocating tenants from

buildings which the NHA hopes

to demol ish or otherwise dispose

36

2.

of;

Taking any additional steps to

vacate buildings, including but

not limited to actions such as

(i) refusing to rent units that

become vacant and available in

buildings targeted for

demolition; (ii) holding units

vacant to serve as a source of

relocation for buildings that

it hopes to demolish; (iii)

failing to properly maintain and

manage individual units and

buildings and projects as a

whole, creating a dangerous

situation for existing tenants,

and leaving many otherwise

vacant and available units in

an uninhabitable state;

3. Taking any steps to sell or

dispose of public housing

buildings or land to private

developers, including but not

limited to taking bids, or

entering contracts, at all

projects, including Columbus and

37

Kretchmer Homes;

E. Declare HUD's approvals of the demolition

of Columbus and Kretchmer Homes to be in

violation of federal law, and issue a

preliminary and permanent injunction (i)

setting aside these approvals, (ii)

compel ling HUD to fol 1 ow appl i cabl e 1 aw, and

particularly the provisions of the 1987 Act,

in its review of any future demolition or

disposition applications, including

requiring NHA to prepare replacement and

relocation plans which comply in all

respects with the legal requirements set

forth in this complaint, and (iii) ordering

NHA to prepare such plans;

F. Order the NHA to immediately take all

feasible steps to rehabilitate and utilize

existing public housing units, restoring

them to the required decent, safe, and

sanitary state, including improving safety,

security, and conditions in all projects and

the utilization of tenant management and

private management where appropriate;

G. Order HUD to oversee these steps and insure

that they are carried out, including the

appointment of HUD or other appropriate

38

outside personnel as may be necessary to

supervise programs of new construction,

modernization, reconfigurration, and other

remedial action related to public housing

in Newark;

H. Order HUD and the NHA to prepare an

environmental impact statement (EIS) and

otherwise comply in all respects with the

National Environmental Policy Act and all

regulations and rules thereunder, in

connection with any building or site

considered for demolition or disposition;

I. Order HUD to insure that in any future

review of NHA demolition or disposition

plans and activities the alternative with

the least discriminatory impact on

minorities is pursued by the NHA;

J. Order the NHA to proceed promptly with the

construction at the Scudder site, where it

has already demolished housing, and to

commence construction of the other 224

townhouses for which it has received

funding; order the NHA to utilize the vacant

land now owned by the NHA or available from

the City of Newark for said construction,

and for all other new construction that it

39

plans or undertakes, instead of using land

now occupied by existing public housing

units; and order the NHA to take all

possible steps within its power to plan for

and achieve the expansion of the supply of

safe and decent low-income housing in

Newark;

K. Order the NHA to immediately request from

HUD permission to rent units to single non-

elderly individuals up to the statutory and

federal regulatory limits.

L. Restore plaintiffs and the members of their

class to their rightful place on the NHA

waiting list where appropriate.

M. Grant such other relief as the court deems

just and equitable, including the

appointment of such experts, receivers or

masters, as may be appropriate to aid in a

resolution of this matter; and

N. Award plaintiffs and their counsel costs and

attorneys' fees.

40