Barnes v. City of Gadsen, Alabama Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Barnes v. City of Gadsen, Alabama Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1959. f2012784-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ee4d05e6-836b-48f2-9863-35901af26f03/barnes-v-city-of-gadsen-alabama-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

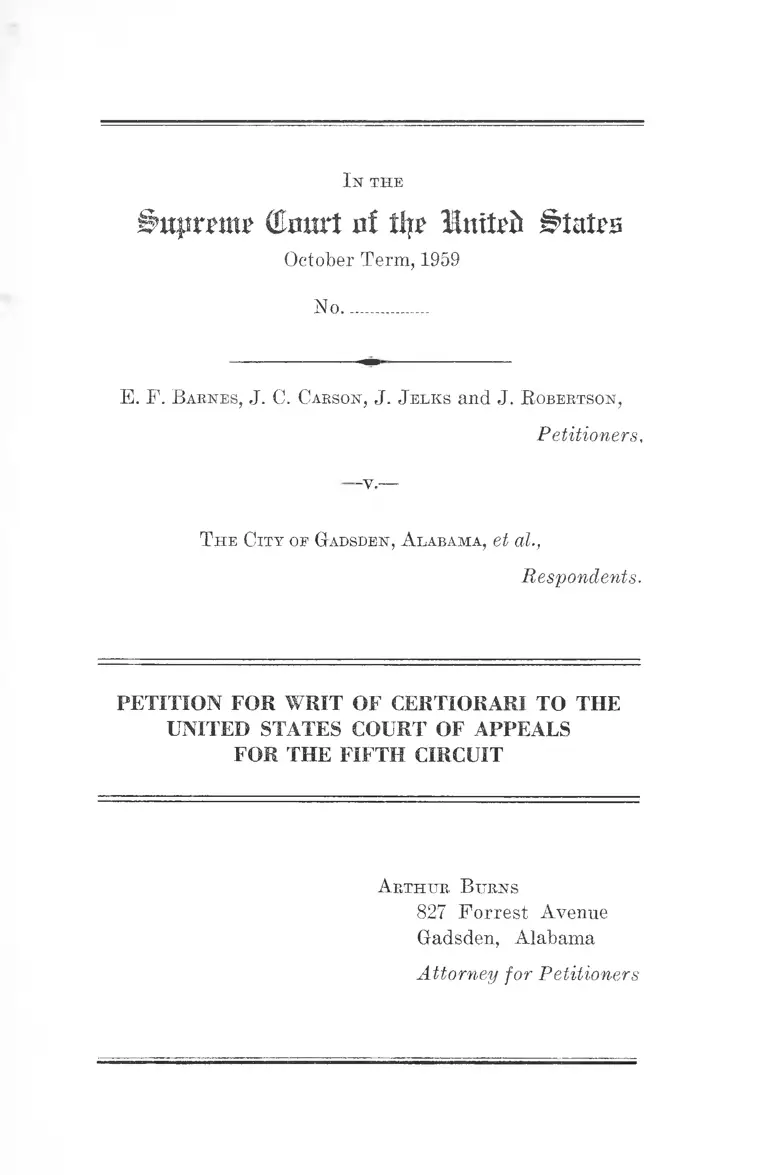

I n t h e

Bnpvnm (£mtrt of % H&niteb i ’tatrs

October Term, 1959

No.............

E. F. B a r n es , J. C. Carson , J. J e l k s and J. R obertson ,

Petitioners,

-v.—

T h e C ity oe G adsden , A labama , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

A r t h u r B u rn s

S27 Forrest Avenue

Gadsden, Alabama

Attorney for Petitioners

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below ...................... .................................... . 1

Jurisdiction ............... ......... ................................ ......... 2

Questions Presented ............................. ........................ 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved...... 2

Statement of the Case .................................................. 3

Eeasons Belied on for Allowance of Writ ................. 7

I. The Public Importance of This Case.............. 7

II. The Court Below Has Decided This Case in

Conflict With Applicable Decisions of This

Court and Applicable Principles Established

by Decisions of This Court ............................ 10

Conclusion .................................................................. 14

Appendix A

Opinion of the Court of Appeals ........................... 15

Appendix .................................... 27

Judgment .... ..................................... .................... 40

Order Denying Rehearing........... 41

Appendix B

Title 42, IT. S. C. §1455 ........................ ........... ...... 42

11

T able oe Ca s e s :

page

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ............... .........8,10,11

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Howard, 343

U. S. 768 (1952) ......................... ................. .............5,11

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 .. 11

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 .................. .............8,10

City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704 ..................... 10

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 17_________ ______ 11

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. 8. 1, 19.......... ..... ................... 11

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town, 299 N. Y. 512, 87 N. E.

2d 541, 14 A. L. R. 2d 133, 150, cert, den., 339 U. S.

981 .............. ........... ........................ ............. .............. 5,7

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 IT. S. 668 ________ _____ ____ 10

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24....................... .................. 8

Johnson v. Levitt & Sons (E. D. Pa. 1955), 131 F.

Supp. 114................... .............. ................................... 5

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 IT. S. 449, 463 (1958) ....5,11,13

Pennsylvania v. Board of Trusts, 353 U. S. 230 (1957) ..5,11

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 .............. .................8,10,11

Smith v. Allwright, 327 IT. S. 649 ...... ........................ 11

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co., 323 IT. S. 192 .... 11

Terry v. Adams, 345 IT. S. 461 (1953) .................. ......... 5,11

Ill

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s :

page

Alabama Code (1940)

Title 25, §§3, 12, 15 .............. ............................... 3

United States Code

Title 42, §§1441, 1450-1462, as amended ..........3, 7,12

Title 42, §1981 ........................................................ 3

Title 42, §1982 ......................................................... 2, 3

Title 28, §1254(1) ................................................... 2

Housing Act of 1949

Title I ...................................................................... 3, 7

Constitution of the United States

Amendment 14, §1 ................................................. 2

“Where Shall We Live!”, Report of the Commission

on Race and Housing, University of California Press

(1958), p. 29 ........... .............................. ...................... 8

Lx THE

( to r t of % Imtrft States

October Term, 1959

No...............

E. F. B a rn es , J. C. C arson , J. J e l k s and J. R obertson ,

Petitioners,

— Y.—

T h e C ity of G adsden , A labama , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Opinions Below

No opinion was written by the majority of the court

below affirming the judgment for respondents by the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama.

However, the minority opinion of Judge Rives, concurring

in part and dissenting in part, is reported, Barnes v. City

of Gadsden, Alabama, 268 F. 2d 593 (1959), and reproduced

in Appendix A. The opinion of the trial court also is re

ported, Barnes v. City of Gadsden, 174 F. Supp. 64 (1958),

and appears in the printed record (R. 275-284).

2

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

the provisions of Title 28, United States Code, §1254(1).

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit was rendered on June 30, 1959. Petition for

rehearing was denied on September 4, 1959, Judge Rives

dissenting (Appendix A, pp. 40-41).

Questions Presented

1. Whether the present urban redevelopment plans of

the City of Gadsden, Alabama, actually contemplate the

effectuation of residential racial segregation and should,

therefore, be enjoined?

2. Whether the private redevelopers, in disposing of the

housing accommodations constructed by them in accordance

with said plan, or any constitutionally valid urban rede

velopment plan, may discriminate between purchasers on

the basis of race or color.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States and the provisions of Title 42, United

States Code, §1982 which provide as follows:

“ . . . nor shall any state deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor

deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the laws” [Amendment 14, §1],

“All citizens of the United States shall have the same

right, in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by

3

white citizens thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell,

hold, and convey real and personal property” [Title 42,

U. S. C. §1982].

This case also involves some of the provisions of Title I

of the Housing Act of 1949, as amended,1 since the urban

redevelopment plans under attack are plans which were

prepared and approved and which will be financed and

executed pursuant to said provisions. However, only those

provisions deemed to have direct bearing upon this case

are set forth in Appendix B.

Statement o f the Case

Invoking the jurisdiction of the trial court pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, §1343(3) and relying upon

provisions of Title 42, United States Code, §§1981 and 1982,

petitioners filed suit in the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Alabama, Middle Division, on

March 10, 1958 on behalf of themselves and approximately

fifty other Negro property owners, similarly situated, chal

lenging the validity of the urban redevelopment plans

adopted by the City of Gadsden, Alabama on the ground

that these plans are expressly designed to effectuate resi

dential racial segregation.2 Declaratory and injunctive re

lief was sought.

The plans in controversy were approved for federal

financial assistance by the Urban Renewal Administration

in accordance with certain provisions of Title I of the Hous

ing Act of 1949, as amended, and a contract for such finan-

1 Title 42, United States Code, §§1441, 1450-1462, as amended.

2 Respondents are authorized by statute to undertake this urban

redevelopment. Alabama Code, 1940, Title 25, §§3, 12, 15.

4

cial aid was entered into between the national government

and the local public agency on August 28, 1957.

After a hearing on petitioners’ motion for preliminary

injunction, which was denied, followed by a hearing on

respondents’ motion to dismiss and, by stipulation, on the

merits, the District Court entered judgment for respondents

pursuant to its findings of fact and conclusions of law (R.

275-285). The District Court found as a fact that the plans

were not intended to and would not have the effect of

segregating the races and concluded as a matter of law that

the private redevelopers, in disposing of the housing con

structed by them in the redeveloped areas in accordance

with the city’s plan, would not be subject to constitutional

proscriptions on state action.

Upon appeal to the court below, the District Court judg

ment was affirmed by two members of the court without

opinion. Judge Rives, the third member of the court, in a

lengthy opinion, affirmed in part and dissented in part.

Judge Rives found as a fact that the plans contemplate

actual segregation but affirmed the denial of an injunction,

which would have prevented execution of the particular

plans in controversy, on the ground that “the serious in

jury which the public may suffer from the stoppage of the

slum clearance projects, and the desire to afford every

opportunity for the voluntary cooperation of the members

of all races for their common welfare and betterment are

potent factors tending to cause the Court to exercise its

discretion to deny an injunction at the present stage of

development of the plans” (Appendix A, p. 20).

Judge Rives dissented on the ground that the conclusion

of law pronounced by the District Court with relation to

the acts of the private redevelopers was clearly erroneous

in the light of several applicable decisions of this Court.

5

Relying on a decision of the Court of Appeals of the

State of New York, Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town, 299 N. Y.

512, 87 N. E. 2d 541, 14 A. L. R. 2d 133, cert, den., 339 U. S.

981, and a federal district court, Johnson v. Levitt <& Sons

(E. D. Pa. 1955), 131 F. Supp. 114, the trial court had held

that action of private redevelopers in refusing to sell to

petitioners and members of their class, solely because of

race or color, “would not be actions under color, authority,

or constraint of state law, nor would they be the perform

ances of functions of a governmental character” (R. 283).

Citing recent applicable decisions of this Court, N. A. A.

C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958); Pennsylvania v.

Board of Trusts, 353 IT. S. 230 (1957); Terry v. Adams,

345 U. S. 461 (1953); Railroad Trainmen v. Howard, 343

U. S. 768 (1952), Judge Rives held that the private rede

velopers in this case are not free to discriminate since, in

his opinion, the plans in controversy, which are clearly

“governmentally conceived, governmentally aided and gov-

ernmentally regulated,” shall not have been completed until

the property passes out of the control of these redevelopers

(Appendix A, p. 25). Accordingly, Judge Rives held peti

tioners are now entitled to a judgment declaring their

rights as stated in his opinion (Appendix A, p. 26).

Judge Rives’ conclusions that the plans contemplate ac

tual segregation and are “governmentally conceived, gov

ernmentally aided and governmentally regulated” were

based upon facts in the record which were either “undis

puted or conclusively established” but which wTere not noted

in the District Court’s findings of fact. Therefore, Judge

Rives set forth these facts in an appendix to his opinion

(Appendix A, p. 27). Judge Rives states that he followed

this unusual procedure because of “the importance of this

litigation to the public, as well as to the litigants.”

6

At this point petitioners respectfully direct the attention

of this Court to the appendix to Judge Rives’ opinion.

However, because the facts there set forth were without

appropriate page references to the printed record and ex

hibits before the Court of Appeals, and since petitioners

have furnished this Court with nine copies of the printed

record, petitioners have inserted in Judge Rives’ appendix

appropriate page references and references to petitioners’

exhibits. Attention is called to Exhibit A, entitled “Gadsden

Redevelopment,” and Exhibit B, Local Public Agency Letter

No. 16, dated Feb. 2, 1953. Attention is also called to

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1, consisting of 1) a copy of each rede

velopment plan, 2) Parts I & II of the Loan and Grant

Contracts between the Greater Gadsden Housing Authority

and the United States of America, and 3) agreements

between the City of Gadsden and the Greater Gadsden

Housing Authority, dated July 25,1957. Finally, the court’s

attention is called to Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1 attached to depo

sition of Mr. Wedge, Regional Director of the Urban Re

newal Administration, and entitled “The Gadsden Plan.”

This exhibit is a master plan for the city as a whole, adopted

by the City Planning Commission of Gadsden, Alabama,

February 19, 1949. This exhibit should not be confused

with Plaintiffs’ Exhibit A which is, admittedly, a correct

description of the immediate plans under attack (R. 172-

173).

In addition to the facts set forth in Judge Rives’ appen

dix, petitioners call this Court’s attention to the fact that

after the final decision on the merits in the trial court,

the Judge of that court reopened the case for the limited

purpose of receiving in evidence affidavits made by peti

tioners and twenty-one other Negro owner-occupants of the

Birmingham Street Area, similarly situated, attesting to

their financial ability to purchase homes in the redeveloped

Birmingham Street Area and their firm desire to do so, if

7

permitted. These affidavits as well as each exhibit have

been sent up to this Court in their original form.

Reasons Relied on fo r Allowance o f Writ

I. The Public Importance of This Case

This case involves implementation of Title I of the Hous

ing Act of 1949, the federal government’s program of

assistance to local communities in order that our perennial

nationwide problem of recurring slum and blighted resi

dential areas may be met, America’s cities rebuilt, and we

may sooner realize our national housing policy’s objective

of “a decent home and a suitable living environment for

every American family.” 3 The special importance of this

case to the public, as well as to these petitioners, stems

from the fact that the record in this case conclusively

establishes that this newest federal housing program is

being implemented by public officials, both state and fed

eral, in complete disregard of constitutional restrictions on

public action. After carefully considering the entire record

in this ease, Judge Rives stated, “I cannot escape the con

clusion that actual segregation is contemplated” (Appendix

A, p. 16). If, as Judge Rives points out, the residential

segregation to be effected here were voluntary or the result

of wholly private activity, no constitutional objections could

be interposed. But the segregation here will clearly result

from non-acquiescence on the part of the Negro community

which voiced its objections at a public hearing (R. 40, 133)

and from a plan which is “governmentally conceived, gov-

ernmentally financed, and governmentally regulated.” 4

3 Declaration of National Housing Policy. Title 42, United States

Code, §1441.

4 Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town, supra, dissenting opinion of Judge

Fuld, 14 A. L. R. 2d, 150.

Prior decisions of this Court have unequivocally voided

legislative and judicial enforcement of residential racial

segregation. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60; Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1; Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24; Barrows

v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249. However, in this case, the execu

tive arm of government, through agencies concerned with

expanding the availability of decent housing and the re

building of our cities, is found to be enforcing residential

racial segregation through the adoption and implementation

of plans for urban redevelopment. The record in this case

discloses that the areas to be redeveloped are presently

racially integrated. In the Birmingham Street area “ . .. oc

cupancy of dwelling units . . . is evenly divided (323 white

and 331 Negro) . . . ” (Exh. A, p. 24). This area will be

cleared of Negroes (Exh. A, p. 24). In the North Fifth

Street Area Negroes occupy about 40% of the dwelling

units. However, according to respondents, “ . . . the fact

that so little of the area is built up leaves its future racial

status still in doubt” (Exh. A, p. 24). Respondents, there

fore, conclude that with respect to this latter area, “North of

Tuscaloosa Avenue only specific planning, such as is advo

cated in this redevelopment proposal, can forecast the

future racial occupancy” (Exh. A, p. 24). Thus, this case

reveals that under the guise of urban redevelopment and

urban renewal the executive arm of government becomes

the primary agent in the initiation of segregated living.

The record in this case also confirms the shocking con

clusion of a recent major study on residential racial segre

gation in the United States: “The policies and actions of

government agencies and public officials must be counted

among the principal influences sustaining racial segrega

tion in housing.” 5

5 “Where Shall We Live?”, Report of the Commission on Race

and Housing, University of California Press (1958), p. 29.

9

Not only does this case involve nullification of prior deci

sions of this Court in the area of residential racial segrega

tion but also the nullification of this Court’s decisions in

the School Segregation Cases. Judge Rives emphasizes in

the appendix to his opinion the manner in which the urban

redevelopment program is being used in this case to nullify

this Court’s decisions in the School Segregation Cases.

Judge Rives points out that,

“The formal redevelopment plan of the North Fifth

Street Area approved by the City provides that:

‘The North Fifth Street Area will, after redevelop

ment, provide 141 units with FHA Committments

[sic] (tentatively approved) open to non-white occu

pancy . . . ’ (Appendix A, p. 28).

M. -4i-•jp iF i f tP

‘e. Recreational and Community Facilities—The

setting aside of land for the use of the City for the

erection of a needed Civic Center with adjacent play-

field and picnic area is in keeping with the adjacent

facilities already erected (Negro Swimming Pool

three blocks away). Also the City Board of Educa

tion took into consideration the Redevelopment

Plan when they erected an elementary sehool which

is located approximately eight blocks away from the

Project Area.’ ” (Appendix A, pp. 28-29).

Judge Rives then points out that “After reading the

foregoing paragraph, Mr. Mills testified: ‘That is in fact

a colored school’ ” (Appendix A, p. 29).

It is, therefore, clear that if the decision of the majority

below is permitted to remain unreversed by this Court, the

policies and actions of government agencies and public

officials must also be counted among the principal influences

sustaining racial segregation in education.

10

Consequently, the question whether the present urban

redevelopment plans of the City of Gadsden actually con

template the effectuation of residential racial segregation,

and should therefore be enjoined, and the question whether

private redevelopers, in disposing of the housing accommo

dations constructed by them in accordance with the pres

ent plan, or any constitutionally valid urban redevelopment

plan, may discriminate between purchasers on the basis

of race or color are questions of the greatest public im

portance which have not been but which must now be deter

mined by this Court.

II. The Court Below Has Decided This Case in Conflict With

Applicable Decisions of This Court and Applicable Princi

ples Established by Decisions of This Court

In the court below petitioners assigned as error, among

others, the finding of the District Court that there was no

evidence to support petitioners’ contention that the urban

redevelopment plans contemplate racial segregation. In

connection with this assignment of error, petitioners ask

this Court to consider Judge Rives’ appendix to his opinion

where he sets forth the facts which led him to hold that

the record in this case contains controlling additional facts,

themselves either undisputed or conclusively established,

which were not noted in the District Court’s findings of

fact but which, when carefully considered, lead to the in

escapable conclusion that actual segregation is contem

plated. If Judge Rives is correct that the record discloses

that actual segregation is contemplated, the judgment of

affirmance by the majority below conflicts with long settled

applicable principles established by decisions of this Court.

Buchanan v. Warley, supra; Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S.

668; City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704; Shelley v.

Kraemer, supra; Barrows v. Jackson, supra; cf. Brown v.

11

Board of Education of Topeka, 347 IT. S. 483; Bolling v.

Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1.

Petitioners also assigned as error the District Court’s

ruling that if private interests restrict sales in the Birming

ham Street Area to white people and sales in the North

Fifth Street Area to colored people, such sales would not

be actions under color, or authority, or constraint of state

law, nor would they be performances of functions of a

governmental character. Affirmance of this holding by the

majority is also in conflict with apposite principles estab

lished by decisions of this Court construing and applying

the Fourteenth Amendment’s prohibitions and defining the

duty imposed upon those acting pursuant to authority con

ferred by government. N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S.

449; Pennsylvania v. Board of Trusts, 353 U. S. 230;

Barrows v. Jackson, supra; Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461;

Brotherhood of Bailroad Trainmen v. Howard, 343 TJ. S.

768; Shelley v. Kraemer, supra; Smith v. AUwright, 327

U. S. 649; Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co., 323 U. S.

192; see Cooper v. Aaron, supra, at 19; see, Civil Rights

Cases, 109 U. S. 3,17.

Judge Elves, in his carefully considered dissenting opin

ion, holds that, under the facts of this ease, the private

redevelopers may not discriminate against purchasers of

homes on the basis of race and color and in support of his

holding cites several of the next preceding decisions of this

Court.

Judge Rives’ holding was based primarily upon the fact

that in this case the private redeveloper will be an essential

participant in the performance of a governmental function.

Judge Rives said, “In my opinion, the plan has not been

completed until the property passes out of the control of the

redeveloper, and hence in disposing of the property within

12

either of the Areas the redeveloper may not discriminate

between purchasers on the basis of race and color” (Appen

dix A, p. 25).

Judge Eives also based his decision on the degree of and

necessity for the governmental aid involved which will

inure to the private redevelopers and ultimately the pur

chasers from these redevelopers. Judge Eives found that

governmental financial aid is required if the redevelopers

are to construct the kind of housing described in the re

development plan. The city is required by the federal stat

ute to certify that such public assistance is necessary.6

The entire cost of acquiring the land in the redeveloped

areas, of clearing these areas, and providing necessary

facilities such as streets, water supply and sewers, less such

“fair value” as may be required to be paid by the rede

velopers, is to be financed by state and federal funds. Two

thirds of this cost will be borne by the federal government

and one third by the City of Gadsden (Part I, Loan and

Grant Contract, Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1).

Finally, Judge Eives based his decision on the extent of

governmental control which is to be exercised over the

activities of these redevelopers. He found that the private

redevelopers will be obligated by the local public agency

to devote the redeveloped land to the uses specified in the

urban redevelopment plans and to begin and complete the

building of the improvements, in this case homes, within

a reasonable time (Part II, Section 106(H), Loan and

Grant Contract, Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1). Such obligation is

also required by the federal statute.7

In addition to obligating the private redevelopers to

carry into effect the redevelopment plans, the private re-

8 Title 42, United States Code, §1455(a). (See Appendix B.)

7 Ibid.

13

developers will be subject to numerous other governmental

controls, as evidenced by the formal redevelopment plans.

(See section headed “Controls on Redevelopment” in each

plan. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1.)

However, it must be carefully noted that the only obli

gation on respondents and private redevelopers with re

spect to racial restrictions is to refrain from effecting or

executing any instrument whereby the sale, lease or oc

cupancy of any land in the redeveloped areas shall be re

stricted on the basis of race, creed or color. Respondents

will place great stress on this obligation and will claim that

it will operate to prevent discrimination in disposing of

land in project areas. However, even the District Court

did not find that this obligation would so operate. The

District Court held that the sales policies of private re

developers, despite this obligation, would not be subject

to Fourteenth Amendment prohibitions. The fact is peti

tioners will not be protected. Even the federal agency does

not construe the requirement as affording any such pro

tection (R. 221-223). Plaintiffs’ Exhibit B plainly demon

strates that the federal agency’s policies expressly provide

for the approval of redeveloped areas which will not be

available to Negroes and other minority group families.

Moreover, as this Court said in N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama,

supra, at 463:

It is not sufficient to answer, as the State does here,

that whatever repressive effect compulsory disclosure

of names of petitioner’s members may have upon par

ticipation by Alabama citizens in petitioners’ activities

follows not from state action but from private com

munity pressures. The crucial factor is the interplay

of governmental and private action, for it is only after

the initial exertion of state power represented by the

production order that private action takes hold.

14

Similarly, here, the crucial factor is the interplay of

governmental and private action, for it is only after the

initial exertion of state power, represented by public

planning, public condemnation, public expenditures and

public clearance and redevelopment of land that private

discriminatory action against petitioners will take hold.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, petitioners pray that a writ o f certiorari

issue to review the judgment o f the court below.

Respectfully submitted,

A r t h u r B u r n s

827 Forrest Avenue

G-asden, Alabama

Attorney for Petitioners

Certificate o f Service

This is to certify that on th e ........ . day of October, 1959,

I served a copy of the foregoing petition for writ of certio

rari upon the Hon. William B. Dortch, attorney for respon

dent City of Gadsden, Alabama, and upon the Hon. John A.

Lusk, Jr., attorney for respondents Greater Gadsden Hous

ing Authority and Walter B. Mills, by personally serving

a copy upon each of them at their respective offices in the

City of Gadsden, Alabama.

A r t h u r B u r n s

Attorney for Petitioners

15

APPENDIX A

Opinion o f the Court o f Appeals

I n t h e

UNITED STATES COUET OF APPEALS

F oe t h e F ie t h C ir c u it

No. 17534

E. F . B a rn es , J. C. Carson , J. J e l k s and J . E obertson ,

Appellants,

T h e C it y of G adsden , A labama , et al.,

Appellees.

a ppea l from t h e u n it e d states d istrict court for t h e

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

(June 30, 1959.)

Before E iv es , Cam eron and J o nes , Circuit Judges.

E iv es , Circuit Judge: This appeal is from a final judg

ment for defendants. The plaintiffs seek a declaration

and injunction against the execution and putting into effect

of certain urban redevelopment plans of the City of Gads

den, Alabama, attacked upon the ground that they foster

enforced racial segregation. The district court entered

judgment in favor of defendants pursuant to findings of

fact and conclusions of law, now reported in -----F.Supp.

----- , with which all of the members of this Court were

16

tentatively in agreement in our first conference following

the argument and submission of this appeal. After further

study and more mature deliberation, Judges Cameron and

Jones adhere to that view while the writer concurs in part

and dissents in part for reasons separately stated. The

judgment is therefore

A f fik m e d .

E iv es , Circuit Judge, Concurring in part and dissenting

in part:

A careful study of the record and exhibits has con

vinced me that there are controlling additional facts,

themselves either undisputed or conclusively established,

which were not noted in the district court’s findings of

fact. Recognizing the importance of this litigation to the

public, as well as to the litigants, I have set forth those

facts at considerable length in an appendix to this opin

ion. Excluding those items of doubtful value or of ques

tionable admissibility, but otherwise carefully consider

ing the entire record, I cannot escape the conclusion that

actual segregation is contemplated. So long as that is

voluntary, rather than governmentally enforced, there

can be no constitutional objection. As we said in Cohen

v. Public Housing Administration, 1958, 257 F.2d 73, 78:

“Mr. Stillwell’s testimony has been noted (footnote

7, supra) to the effect that in his opinion actual segre

gation is essential to the success of a program of public

housing in Savannah. If the people involved think

that such is the case and if Negroes and whites desire

to maintain voluntary segregation for their common

good, there is certainly no law to prevent such co

operation. Neither the Fifth nor the Fourteenth

Amendment operates positively to command integra-

17

tion of the races but only negatively to forbid govern-

mentally enforced segregation.11

“ 11 Cf. Avery v. Wichita Falls Independent

School District, 5 Cir., 1957, 241 F.2d 230, 233;

Dippy v. Borders, 5 Cir., 1957, 250 F.2d 690, 692.”

That governmentally enforced segregation in housing

is unconstitutional has now been settled beyond contro

versy.1 The cases just cited in footnote 1 make clear that

a State agency has no constitutional power to oust persons

of one race from their homes and thereafter forcibly to

restrict the land to the exclusive occupancy of persons

of another race. Ultimately then, the issue on its merits

must turn upon whether the contemplated actual segrega

tion is to be voluntary or governmentally enforced. At the

present stage the plaintiffs and the defendants face real,

though different, dilemmas in reaching that issue. The

plaintiffs feel that they cannot wait longer. As their at

torney stated to the district court:

“Mr. Burns: That is the very reason why we have

to do this now. If we wait until the private developers

get it into their hands, it’s too late.

“In that Levitown case, where the Court said that the

Court would not require the private developer to sell;

allowed him to discriminate, where it was without

1 Buchanan v. Warley, 1917, 245 U.S. 60; Benjamin v. Joseph W.

Tyler, 1927, 273 U.S. 668; City of Richmond v. Deans, 1930, 281 U.S.

704; Shelley v. Kraemer, 1948, 334 U.S. 1; Barrows v. Jackson, 1953,

346 U.S. 249; City of Birmingham v. Monk, 5th Cir. 1950, 185 F.2d

859; Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 6th Cir. 1955, 226 F.2d

180; Tate v. City of Eufaula, Alabama, M.D. Ala. 1958,165 F.Supp.

303; Jones v. City of Ilamtramck, E.D. Mich. 1954, 121 F.Supp.

123; Vann v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority, N.D. Ohio

1953, 113 F.Supp. 210; Banks v. Housing Authority, D.C. App.

Calif. 1953, 260 P.2d 668; Taylor v. Leonard, 30 N.J. Super. 116,

1954, 103 A.2d 632.

18

dispute that he was discriminating and the Court let

him do it.”

In its conclusion of law the district court recognized,

if it did not resolve, the plaintiffs’ dilemma:

“The Court concludes from an analysis of plaintiffs’

complaint, evidence and arguments that their claim

for relief is grounded primarily on the apprehension

that when the two areas are cleared and rehabilitated

and sold to private interests under legitimate restric

tions as to use that plaintiffs and members of their

class will not be able to purchase property in the Bir

mingham Street Area because of their race or color,

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corp., 299 N.Y. 512, 87

N.E. 2d 541, 14 A.L.R.2d 133, cert, denied 337 U.S.

981, and that if they purchase homes in the North

Fifth Street Area they will be racially segregated in

that area, and, therefore, they should be delivered

from the apprehension of this possible dilemma by

injunctive relief, preventing the carrying out of the

plans which, they insist, constitute a scheme and de

sign for initiating, enforcing, extending and perpetuat

ing racial segregation in residential areas of Gadsden

in violation of their constitutional rights. Otherwise,

they see no escape from their anticipated predicament

once the properties are sold to private interests; and

they are fearful in that event that their last state will

become worse than their first.

“If the Court assumes that private interests will

restrict sales in the Birmingham Street Area to white

people and the North Fifth Street Area to colored

people, such sales would not be actions under color,

authority, or constraint of state law, nor would they

19

be the performances of functions of a governmental

character. Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corp., supra,

Johnson v. Levitt & Sons, Inc., E.D. Pa., 131 F.Supp.

114.”

The defendants, on their part, stoutly deny that any

enforced segregation is contemplated. Their brief states:

“In this case no one is compelled to occupy the new

houses to be constructed, and no one is prohibited from

purchasing such houses; anyone buying any of the

property will have to buy it with full knowledge that

there can be no discrimination in the future.

“The court should assume that the defendants, their

agents and successors in office, after receiving the

federal assistance in this public project, will, upon

completion of this project, or in carrying it out, recog

nize the law to the effect there can be no governmentally

enforced segregation solely because of race or color.

Tate v. City of Eufaula, 165 Fed.Supp. 303.”

The defendants point out that the plaintiffs may not,

when the time comes, want to move back into either of

the Areas:

“ . . . it boils down to the question of whether a

complaint based on plaintiffs’ alleged fears that they

may not be able to repurchase land in the redeveloped

area states a cause of action upon which relief can

be granted. It is obvious that such redevelopment

cannot be accomplished in a short period of time. It

is equally obvious that not only plaintiffs but all occu

pants of the North Fifth Street area and the Birming

ham Street area must be moved and relocated pending

such clearance. It is by no means clear that plaintiffs

20

or any of the occupants of these areas will even want

to move back into such areas after redevelopment. Yet

these plaintiffs are insisting that the entire slum clear

ance project be stopped on such a complaint.”

1 agree that the serious injury which the public may

suffer from the stoppage of the slum clearance projects,

and the desire to afford every opportunity for the volun

tary cooperation of the members of all races for their

common welfare and betterment are potent factors tend

ing to cause the Court to exercise its discretion to deny

an injunction at the present -stage of development of the

plans. As said by Judge Sibley, speaking for this Court

in Kelliher v. Stone & Webster, 5th Cir, 1935, 75 F.2d 331,

333, 334:

“ . . . and when a public improvement is sought to

be stopped, the inconvenience to the public, as weighed

against a slight or remediable wrong to the plaintiff,

may determine the court of equity against this dis

cretionary remedy.”

The injury which the plaintiffs anticipate, namely, that

they may be forced to dispose of their homes for an un

constitutional purpose, cannot be called slight. Rather,

the questions are whether the plaintiffs will suffer a legal

wrong and whether, at the present stage, their plight is

irremediable. If irreparable injury to the plaintiffs will

ensue, and if such injury cannot be otherwise prevented,

then a suit for injunction restraining the carrying out of

the plans is appropriate to present the question of a pro

posed unlawful exercise of the power of eminent domain

for the purpose of subjecting the property taken to a

racially discriminatory and unconstitutional use.2

2 City of Los Angeles v. Los Angeles Gas & Electric Corporation,

1919, 251 U.S. 32; Iowa Electric Light & Power Co. v. City of

21

The “Controls on Redevelopment,” including the re

quirement of an anti-racial covenant, go a long way to

protect the plaintiffs from governmentally enforced segre

gation. They do not, however, afford adequate protection

if the redeveloper is free to restrict sales in the Birming

ham Street Area to white people and in the North Fifth

Street Area to Negroes. Enforced segregation might well

be the practical result, whether or not so intended by the

defendants. The plaintiffs might derive some small com

fort from hearing a court tell them that their segregation

was privately enforced rather than governmentally en

forced. They might still feel that they stood equal before

the law.

' While the district court entered formal judgment for

the defendants, it did not in fact decline to make any

declaration of the rights of the parties, but in those parts

of its conclusions of law which I have quoted, ante, p. 3,

as construed in connection with the cases cited, it held

that the redeveloper is a mere private individual and as

such free to discriminate in sales to persons of different

races. For reasons presently to be stated, I do not agree

with that conclusion, but, by the same token, I do agree

that injunction at the present stage of development of

the plans should be denied.

The district court relied upon two cases in considering

that sales by the redeveloper would not constitute state

action within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corporation, 1949, 299 N.Y.

512, 87 N.E.2d 541, 14 A.L.R.2d 133, and Johnson v.

Levitt Sons, E.D. Pa. 1955, 131 F.Supp. 114. In the

Lyons, Neb., D.C. Neb. 1958, 166 F.Supp. 676, 680; Quinn v.

Dougherty, App.D.C. 1929, 30 F.2d 749; Reichelderfer v. Quinn,

App.D.C. 1931, 53 F.2d 1079, reversed on merits, 1932, 287 U.S.

314; 30 C.J.S., Eminent Domain, Sees. 403, 407; 18 Am.Jur.,

Eminent Domain, Sec. 386.

22

Johnson ease the district court held that F.H.A. and V.A.,

as federal agencies guaranteeing mortgages on housing-

projects, had no duty to prevent discrimination in sales

of houses, and injunction did not lie to restrain agencies

from insuring mortgages so long as the project proprietor

discriminated against purchasers because of race and color.3

In Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corporation, supra, the

New York Court of Appeals held that a corporation or

ganized under the New York Redevelopment Companies

Law to provide low-cost housing is not an agency of the

state and hence is not prohibited by the equal protection

clauses of the State and Federal Constitutions from dis

criminating against prospective tenants because of race,

color, or religion. The case is unusually well considered

both by Judge Bromley, speaking for the majority of four,

and by Judge Fuld, speaking for the three dissenting

judges. The majority arrives at the conclusion that:

“ . . . The aid which the State has afforded to re

spondents and the control to which they are subject

are not sufficient to transmute their conduct into State

action under the constitutional provisions here in

question.” 14 A.L.R. 2d 146.

The extent of the aid furnished by the State and Fed

eral Governments to the redeveloper and of the control to

which the redeveloper is subject readily distinguishes the

present case from either of the cases upon which the

district court relied. In Johnson v. Levitt £ Sons, supra,

the federal agencies simply guaranteed mortgages on hous

ing projects. In Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corporation,

supra, the City of New York agreed to condemn the land

3 Compare Ming v. Horgan, Super. Ct. Sacramento County, Calif.,

1958, reported in 3 Race Relations Law Reporter 693.

23

necessary for the project and to grant a tax exemption,

but the full cost of construction and land acquisition was to

be borne by the corporation. In the present case, the entire

cost of land acquisition, and of the land itself, less such

“use value” as may be required to be paid by the rede

veloper, is to be borne by government funds, approximately

two-thirds by the United States and one-third by the City

of Gadsden. Of even more importance, the redeveloper is

an essential participant in the overall plans for redevelop

ment here involved. The federal statute made it necessary

for the Authority to require the redeveloper to carry the

plan into execution.4

The formal plans approved by the City of Gadsden

contained detailed and specific “Controls on Redevelop

ment” requiring “The redeveloper to begin and complete

the development of Project Land acquired by it for the

use required by the Redevelopment Plan . . . ” If Dorsey

v. Stuyvesant Town Corporation, supra, had presented a

like extent of governmental aid and of state control of

4 “§1455. Requirements for loan—or capital-grant contracts

“Contracts for loans or capital grants shall be made only with

a duly authorized local public agency and shall require that—

“Obligations of purchasers, lessees,

and assignees of property

“ (b) When real property acquired or held by the local public

agency in connection with the project is sold or leased, the pur

chasers or lessees and their assignees shall be obligated (i) to devote

such property to the uses specified in the urban renewal plan for

the project area; (ii) to begin within a reasonable time any im

provements on such property required by the urban renewal plan;

and (iii) to comply with such other conditions as the Administrator

finds, prior to the execution of the contract for loan or capital grant

pursuant to this subchapter, are necessary to carry out the purposes

of this title: Provided, That clause (ii) of this subsection shall

not apply to mortgagees and others who acquire an interest in

such property as the result of the enforcement of any lien or claim

thereon.” 42 U.S.C.A. §1455(b).

24

the corporation, I believe that the majority must have

agreed with the dissenters’ view that:

“ . . . Unmistakable are the signs that this under

taking was a governmentally conceived, governmentally

aided and governmentally regulated project in urban

redevelopment.” 14 A.L.K. 2d 150.

I would not repeat a reference to the authorities so

well discussed in Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corporation,

supra, but would refer briefly to a few later decisions.

Among these is our own case of Derrington v. Plummer,

5th Cir. 1956, 240 F.2d 922, in which we held that, where

a county leases a cafeteria in a newly constructed court

house to a private tenant operator, the tenant’s exclusion

of persons merely because they were Negroes constituted

state action in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.5

In N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 1958, 357 U.S. 449, 462, 463,

the Supreme Court said:

“We think that the production order, in the respects

here drawn in question, must be regarded as entail

ing the likelihood of a substantial restraint upon the

exercise by petitioner’s members of their right to free

dom of association. Petitioner has made an uncontro

verted showing that on past occasions revelation of

the identity of its rank-and-file members has exposed

these members to economic reprisal, loss of employ

ment, threat of physical coercion, and other manifesta

tions of public hostility. Under these circumstances,

we think it apparent that compelled disclosure of peti

tioner’s Alabama membership is likely to affect ad

versely the ability of petitioner and its members to

5 That holding, it may be noted, was cited with approval by the

Supreme Court in Cooper v. Aaron, 1958, 358 U.S. 1, 17.

25

pursue their collective effort to foster beliefs which

they admittedly have the right to advocate, in that it

may induce members to withdraw from the Association

and dissuade others from joining it because of fear

of exposure of their beliefs shown through their as

sociations and of the consequences of this exposure.

“It is not sufficient to answer, as the State does

here, that whatever repressive effect compulsory dis

closure of names of petitioner’s members may have

upon participation by Alabama citizens in petitioner’s

activities follows not from state action but from private

community pressures. The crucial factor is the inter

play of governmental and private action, for it is only

after the initial exertion of state power represented by

the production order that private action takes hold.”

A few other late Supreme Court cases illustrative of

the principle that governmental action may include the

action of a private person who performs a governmental

function are: Railroad Trainmen v. Howard, 1952, 343 U.S.

768; Terry v. Adams, 1953, 345 U.S. 461; and Pennsylvania

v. Board of Trusts, 1957, 353 U.S. 230.

In my opinion, the plan has not been completed until

the property passes out of the control of the redeveloper,

and hence in disposing of property within either of the

Areas the redeveloper may not discriminate between pur

chasers on the basis of race or color. We should, I think,

follow the course so well outlined by Judge Johnson of

the Middle District of Alabama in Tate v. City of Eufaula,

Alabama, M.D.Ala. 1958, 165 F.Supp. 303, 306, 307:

“ . . . this Court must now assume that these de

fendants, their agents and successors in office, after

receiving the federal assistance in this public project,

will, upon a completion of this project (or any phase

of it), recognize the law that is now so clear; this law

26

being to the effect that there can be no governmentally

enforced segregation solely because of race or color . . .

“If these defendants, their agents or successors,

as public officers and with federal financial assistance

complete this project or any phase of it, they do so

with the certain knowledge that there must be a full

and good faith compliance with this existing law.”

I agree that the judgment should be affirmed in so far

as it denies an injunction, but, to the extent that it seems

to me actually but erroneously to declare the rights of the

parties, I think that the judgment should be reversed and

judgment here rendered declaring such rights as stated in

this opinion. I therefore concur in part and dissent in

part.

27

Appendix*

M atebial F acts N ot F u l l y S et F o eth in t h e

D istrict C o urt’s F in d in g s

The City of Gadsden is an Alabama municipal corpora

tion,1 and the Greater Gadsden Housing Authority is a

public body corporate organized under the laws of the

State of Alabama.2

Each of the four Negro plaintiffs owns a house in which

he resides located in the Birmingham Street Area (R. 276).

Each member of the represented class of about fifty other

Negro citizens owns a house in one of the areas planned

for redevelopment (R. 276). The North Fifth Street Area

contains a considerable amount of vacant land and is

planned to be redeveloped ahead of the Birmingham Street

Area, so as to provide living space in the form of 128 small

building lots for some of the families displaced by the later

demolition of the Birmingham Street Area (Plaintiffs’ Exh.

A, pp. 10, 12). The latter area is then to be redeveloped to

provide 121 large building lots for single-family homes

(Plaintiffs’ Exh. A, p. 10). The Authority admits in its

answer that it plans to purchase or acquire by eminent

* Petitioners have inserted in this appendix appropriate refer

ences to the pages of the printed record, 9 copies of which have

been furnished this Court, and appropriate references to Peti

tioners’ exhibits which have been sent up to this Court in their

original form.

1 The laws of Alabama authorize the City to join in the execu

tion of the plans for urban redevelopment. 1940 Code of Alabama,

Title 25, Section 3.

2 The powers of the Authority are detailed in 1940 Code of

Alabama, Title 25, Section 12. Section 15 of the same title vests

the Authority with the right to acquire property by eminent

domain.

28

domain all of the property in the two Areas planned for

redevelopment (R. 95).

The Agreements between the City and the Authority

disclose that, in order for the Authority to effectuate the

plans,

“ . . . the assistance of both the Federal Govern

ment and the City is required; namely of the Federal

Government by lending funds needed to defray the

gross cost of the Project, and upon completion of the

project and repayment of such loan, by contributing

two thirds (%) of the net cost of the project; and of

the City by making certain local grants-in-aid (as

specified by Title I of the Housing Act of 1949, as

amended) as hereinafter provided, in a total amount

equal to at least one-third (Yz) of the net cost of

the Project . . . ” (Plaintiffs’ Exh. I, p. 1 of said

Agreement.)

The formal redevelopment plan of the North Fifth Street

Area approved by the City provides that:

“The North Fifth Street area will, after redevelop

ment, provide 141 units, with FHA Committments

[sic] (tentatively approved) open to non-white oc

cupancy. 73 single family sales units in the price

range of $6,500 to $8,500, 64 duplex units in the rental

ranges of $40.00, $45.00 and $50.00 shelter rent per

month, will be available (Plaintiffs’ Exh. I, p. 7 of

said plan).

“c. Recreational and Community Facilities—The

setting aside of land for the use of the City for the

erection of a needed Civic Center with adjacent play-

field and picnic area is in keeping with the adjacent

facilities already erected (Negro Swimming Pool three

29

blocks away). Also the City Board of Education took

into consideration the Redevelopment Plan when they

erected an elementary school which is located approxi

mately eight blocks away from the Project Area”

(Plaintiffs’ Exh. I, p. 11 of said plan).

After reading the foregoing paragraph, Mr. Mills testified:

“That is in fact a colored school” (R. 36).

The formal redevelopment plan of the Birmingham Street

Area approved by the City also states: “The North Fifth

Street area will, after redevelopment, provide 138 units,

with FHA Committments [sic] (tentatively approved) open

to Negro Occupancy” (Plaintiffs’ Exh. I, p. 6a of said plan).

The document principally relied on by the plaintiffs

was made Exhibit A to their complaint, and consisted of

an elaborate printed brochure captioned, “Gadsden Rede

velopment.” Its preparation was paid for by the Federal

Government (R. 197-198). It was the only document handed

out to the general public at the time of a public hearing-

required by 42 U.S.C.A. 1455(d) to be held in connection

with the redevelopment plans (R. 133). At that hearing

Negro citizens voiced their objections to the plans (R. 133).

Mr. Wedge, Regional Director of the Urban Renewal

Administration, testified:

“A. That particular brochure was submitted to our

agency in connection with the planning and survey

materials prepared with the benefit of the preliminary

advance of funds.

“Q. All right, sir. I believe you said or did I under

stand you to say that this brochure here was submitted

to your agency by the Greater Gadsden Housing Au

thority?

“A. It was submitted as a part of the supporting docu

mentation accompanying the applications” (R. 198).

30

The parts of that document upon which the plaintiff rely are

quoted in the margin.3

3 “SITES SELECTED FOR REDEVELOPMENT

“The Birmingham Street Site

“The Master Plan describes the Birmingham Street Area as

‘ • . . lying in the flat land at the head of Rum Branch, formerly

a servants’ quarters section that became pocketed by better class

residential development. Lack of space for expansion led to

“building between” until now these few blocks contain 250 dwell

ings. The area is occupied by Negroes, but the number is too few

to justify provisions of proper recreational, school, and social

facilities.’

“The recent survey brought out, more forcefully because it was

more detailed, the facts stated in the Master Plan’s diagnosis: the

poor quality of housing, lack of public and community facilities,

and overcrowding. These conditions are in strong contrast to

those of the surrounding section which, except for a small commer

cial center to the north, is characterized by homes of good quality.

“The opportunity to reconstitute the area as a residential district

in harmony with its surroundings was the main reason for its

selection as the number one redevelopment site (Exh. A, p. 4).

“The North Fifth Street Site

“A relatively small amount of housing—standard or substandard

—exists on the North Fifth Street site. This, in fact, is the prin

cipal reason for its selection as a companion project to the Birming

ham Street one: it will permit redevelopment for a greater number

of families than clearance of the site will displace, thus affording

home sites for those occupants of the Birmingham Street site who

are not eligible for relocation in public housing or who, for reasons

of their own, prefer single-family or duplex dwellings.

“A second important reason for selection of this area for redevelop

ment is the incentive it will provide for further extension of the

Negro neighborhood up along the foothills of Shinbone Ridge.

While some of the terrain is steep, much of it is gently rolling and

well drained; this can be developed as an open residential section,

convenient to school and social centers as well as to the central

business district and industries of the city (Exh. A, p. 5).

“THE PROJECTED PLANS

“North Fifth Street Area

“In most Southern cities there is a scarcity of vacant land located

close to schools and churches and shopping districts and served by

city utilities and transportation, land that is suitable and desirable

31

The plaintiffs rely also on “Local Public Agency Letter

No. 16” issued by the Director of the Housing and Home

Finance Agency on February 2, 1953, and reading in part

as follows:

for expansion of Negro neighborhoods or creation of new ones.

This is true of Gadsden.

“But sometimes careful search will reveal areas that have been

overlooked or by-passed or, for some other reason, have not been

exploited for this purpose. The North Fifth Street site is such an

area.

“Blighted in its south part and spoiled for residential use north of

Tuscaloosa Avenue by a sprawling but small industrial enterprise,

this site is, nevertheless, one that offers the possibility for a new off

shoot from the Tuscaloosa Avenue neighborhood. It is close to

schools, churches, lodges, swimming pool, and playgrounds, as well

as to the Tuscaloosa Avenue business section. It can easily be

served with city utilities.

“Most importantly, it gives, to the north, onto a large open space

that can be used for expansion of the small development to be

created initially through this program (Exh. A, p. 6).

“USE OF LAND

“North Fifth Street Area

“A feature of the plan is the four-acre site allocated to a com

munity center; here the city will in future construct an auditorium

to serve the Negro community. A small playfield to augment exist

ing recreational facilities in the neighborhood will be provided in

conjunction with the center (Exh. A, p. 10).

“BIRMINGHAM STREET AREA

“Located half a mile from the central business district, the Bir

mingham Street section will offer spacious home sites on quiet resi

dential streets, newly paved and serviced with utilities (Exh. A,

p. 14).

“NORTH FIFTH STREET AREA

“Like the Birmingham Street Area, this area is only a short dis

tance from the central business district of the city. And it is equally

well served with city utilities and community facilities, elementary

and high schools for Negro children being less than half a mile

away. The North Fifth Street Area is, in fact, virtually the only

32

“The general procedures developed in the course of

actual operating experience from the joint efforts of

such close-in land available for expansion of the Negro community

(Exh. A, p. 15).

“Provision is made at the north extreme of the area for continuing

North Fifth Street beyond this site so that the Negro neighborhood

can be expanded by private developers (Exh. A, p. 15).

“SURVEY AREAS

“Birmingham Street Survey Area

“The core of this area is a group of squalid dwellings occupied by

Negro families, some of whose grandparents undoubtedly also occu

pied this same old servants’ quarters section. There are no schools,

parks, or social facilities, but the residents have built several

churches which fill an important social need as well as the religious

one (Exh. A, p. 18).

“COMMUNITY FACILITIES

“Birmingham Street Survey Area

“Of the five churches, two serve the Negro neighborhood at Bir

mingham Street, the others having city-wide white congregations

(Exh. A, p. 22).

“RACIAL OCCUPANCY

“While occupancy of dwelling units in the Birmingham Street

Survey Area is evenly divided (323 white and 331 Negro), it is

the sections of Negro occupancy—Birmingham-Bay Streets and

St. John’s Alley—that coincide with the sections of blighted hous

ing (Exh. A, p. 24).

“In the North Fifth Street Survey Area Negro families occupy

about 40% of the dwellings, but the fact that so little of the area

is built up leaves its future racial status still in doubt. North of

Tuscaloosa Avenue only specific planning, such as is advocated in

this redevelopment proposal, can forecast the future racial occu

pancy” (Exh. A, p. 24).

That document also contained a colored map with “Source: City

Directory, 1952” showing “Racial Occupancy and Home Owner

ship” and the other maps showing the projected plans for the

North 5th Street area, including a “Proposed Colored Auditorium”

and “Playfield (Col.)” (Exh. A, p. 25).

33

the local and Federal agencies to assure that the liv

ing space available in a community to Negro and other

racial minority families is not decreased are based upon

the following:

“A slum or blighted area presently occupied in whole

or in part by a substantial number of Negro or other

racial minority families may be cleared and redeveloped

if:

“1. The area is to be redeveloped as a residential

area and the housing is to be available for occupancy

by all racial groups (at rents or sales prices within the

financial capacity of a substantial number of Negro

or other racial minority families in the community), or

“2. The area is to be redeveloped as a residential

area and a proportion of the housing bearing reason

able relationship to the number of dwelling units in the

area which were occupied by Negro or other racial

minority families prior to its redevelopment is to be

available for occupancy by Negro or other racial

minority families, or

“3. The area is to be redeveloped as a residential

area but the housing is not to be available for occu

pancy by all racial groups or for occupancy by Negro

or other racial minority families, and:

“A. Decent, safe, and sanitary housing available

for occupancy by Negro, or by other minority group,

families (in an amount substantially equal to the

number of dwelling units in such area which were

occupied by Negro or other racial minority families

prior to its redevelopment) is made available (at

rents or sales prices within the financial capacity

of a substantial number of Negro or other racial mi

nority families in the community) through new con-

34

struction in areas elsewhere in the community or in

adequate existing housing in areas elsewhere in the

community not theretofore available for occupancy

by Negro or by other racial minority families, which

areas are not generally less desirable than the area

to be redeveloped, and

“B. Representative local leadership among Negro

or other racial minority groups in the community

has indicated that there is no substantial objection

thereto, or . . . ” (Plaintiffs’ Exh. B, pp. 2-3).

Referring to that letter, Mr. Wedge testified that: “Para

graph 3 of L.P.A. 16 has (n)ever been used or applied by

the Housing and Home Finance Agency to promote any

form of housing restricted to occupancy by members of the

colored race” (R. 268).

Mr. Wedge further testified:

“Since L.P.A. Letter No. 16 contains administrative

guides for reviewing one of the many aspects of an

urban renewal project, the Birmingham Street Project

was reviewed in the light of so-called procedure No. 3

as well as many, many other procedures and require

ments of the agency” (R. 205).

After some understandable hesitation, both Mr. Wedge

and Mr. Mills were commendably frank and candid to the

effect that the plans contemplated actual segregation of

the races.

Mr. Wedge testified:

“Q. Then I will ask you the same question with reference

to the Birmingham Street area. It is contemplated that

the Birmingham Street area when redeveloped will be

available for any non-white occupancy? (R. 225.)

35

“A. The relocation plan, as I mentioned, is the place

where we have to look carefully under the provisions

of 105 (c) to determine the financial ability of displaced

families and, therefore, North Fifth Street is a factor

in the feasibility of relocation strictly from an economic

point of view. With respect to the Birmingham Street,

the plans in compliance with the federal law conform

to the plan for the community as a whole and of the

neighborhood in particular, and in that case on the basis

of marketability studies and indications of probable

types of development, it appeared that the land there

would be substantially more costly than the land that

would be provided in the North Fifth Street area. Does

that answer your question? (R. 225-226.)

“Q. Well, yes, sir, I think it does substantially answer

it except for one minor point that I would like to get

completely clear. The fact is, then, that whether it is

because of economics or for whatever other reason, the

Urban Renewal Administration does not contemplate

that the Birmingham Street area will be available for

non-white occupancy? (R. 226.)

“A. We do not contemplate that” (R. 226).

Mr. Mills testified:

“Q. I will ask you if it is not a matter of policy, custom

and usage for all housing projects in the City of Gads

den to be racially segregated ?

“A. The projects occupied by white people are built in

white areas. And the ones occupied by colored people

are in the colored areas.

All applications are received in one central office,

and they are all processed by the same person, and the

housing, as it becomes vacant is made available to

them” (R. 61).

36

As to low rent public housing to be administered directly

by the Authority, Mr. Mills testified:

“Q. You don’t plan any new construction of low rent

public housing ?

“A. Oh yes.

“Q. Have you set any date ?

“A. Some future time.

“Q. Even any date within years ?

“A. Do you want me to answer your question!

“Q. Has any date been set within even a period of three

or four years?

“A. No, there has been no date set, but a reservation of

two hundred units has been made.

“Q. Will they be for white or colored?

“A. It is dependent on the need.

“Q. In any event, will they be segregated or desegre

gated?

“A. They will follow the community pattern of Gadsden,

which is segregated public housing.

“Q. We come back to the same thing, if any of these

plaintiffs are eligible and do, either by choice or neces

sity, move into a low rent housing project, it will be a

segregated low rent housing project?

“A. Oh yes.

“Q. If it is in Gadsden.

“A. That is right” (B. 154).

Mr. Mills insisted, however, that there was no require

ment of racial segregation:

“A. Of course, Mr. Burns, all the way through, in both

the preliminary and the other plan there has been this

anti-restrictive clause, anti-racial clause in it. And we

haven’t said that Negroes shall live or shall not live in

37

either one of these areas in the redevelopment plan as

adopted” (R. 170).

In the formally approved redevelopment plan of the

Birmingham Street Area, it is provided under the heading

of “Controls on Redevelopment” :

“a. Redeveloper’s Contracts—In addition to such condi

tions and requirements as the Authority may deem

desirable, each contract and deed with a redeveloper

shall also require: (Plaintiffs’ Exh. 1, p. 9 of said

Plan.)

“b. Covenants Running with the Land—Notwithstand

ing the provisions of any zoning or building ordinances

or regulations, now or hereinafter in force, the follow

ing shall be incorporated as covenants inappropriate

disposition instruments by reference to a written dec

laration thereof recorded simultaneously with the new

plat of the Project Area. These covenants are to run

with the land and shall be binding on all parties and

persons claiming under them for the period of time this

Redevelopment Plan is in effect, except that the Anti-

Racial Covenant paragraph (2)(c) below shall run in

perpetuity (Id. p. 10).

“(2) General Covenants

“(c) Anti-Racial Covenant—No covenants, agree

ment, lease, conveyance or other instrument shall be

effected or executed by the Authority, or by the pur

chasers or lessees from it or any successors in interest

of such purchasers or lessees, whereby land in the

Project Area is restricted upon the basis of race, creed

or color, in the sale, lease or occupancy thereof” (Id.

p. 10).

Section 106 of “Part II of Loan and Grant Contract

between a Local Public Agency and the United States of

America” provides in part:

“(C) General Requirements Concerning Land.—The

Local Public Agency will:

“ (1) Take all reasonable steps to remove or abro

gate or to cause to be removed or abrogated, any

and all legal enforceable provisions in any and all

agreements, leases, conveyances or other instruments

restricting, upon the basis of race, creed or color,

the sale, lease or occupancy of any land in the Project

Area which the Local Public Agency acquires as a

part of the Project;

“ (2) Not itself effect or execute, and will adopt

effective measures to assure that there is not effected

or executed by the purchasers or lessees from it (or

the successors in interest of such purchasers or

lessees), any agreement, lease, conveyance or other

instrument whereby Project Land which is disposed

of by the Local Public Agency is restricted, either by

the Local Public Agency or by such purchasers,

lessees or successors in interest, upon the basis of

race, creed or color, in the sale, lease or occupancy

thereof; (Plaintiffs’ Exit. 1 , p. 9 of said Contract)

“ (H) Obligating Redevelopers.—When Project

Land is sold or leased by the Local Public Agency,

it will obligate the purchasers or lessees, as the case

may be, (1) to devote such Project Land to the uses

specified in the Project Redevelopment Plan; and

39

(2) to begin and complete the building of their im

provements on such Project Land within a reason

able time” (Id. pp. 10-11).

I do not consider it necessary to extend this overlong

statement of the facts by referring to another printed

brochure captioned “The Gadsden Plan” and shown on its

flyleaf to have been “Adopted by The City Planning Com

mission Of The City of Gadsden, Alabama—February 19,

1949” (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1 attached to Wedge deposition).

Mr. Wedge testified that the parts of that document upon

which the plaintiffs rely were not considered by the Urban

Renewal Administration, and Mr. Mills called attention that

that document was obsolete:

“I would like for the record to show that is a publica

tion of the City Planning Commission of the City of

Gadsden, that the studies were completed in 1947, that

it was adopted in January 1949, I think, prior to the

passage of the Housing Act of 1949” (R. 254).

Further, it is not necessary to consider two items of evi

dence to the introduction of which the defendants objected;

namely, a news release of the Housing and Home Finance

Agency dated November 7, 1957, and an article from a

Jackson, Mississippi, newspaper dated March 5, 1958, de

scribing a meeting at which Mr. Mills described parts of

the Gadsden redevelopment program (Plaintiffs’ Exhibits

C&E).

40

Judgment

Extract from the Minutes of June 30,1959.

No. 17534

E. F. B a rn es , J. C. Carson , J. J e l k s and J. R obertson ,

-v.—

T h e C it y oe Gadsden , A labama , e t a l .

This cause came on to be heard on the transcript of the

record from the United States District Court for the North

ern District of Alabama, and was argued by counsel;

On consideration w h e r e o f , It is now here ordered and

adjudged by this Court that the judgment of the said Dis

trict Court in this cause be, and the same is hereby, affirmed;

It is further ordered and adjudged that the appellants,

E. F. Barnes, J. C. Carson, J. Jelks and J. Robertson, be

condemned, in solido, to pay the costs of this cause in this

Court for which execution may be issued out of the said

District Court.

“Rives, Circuit Judge, concurring in part and dissenting

in part.”

41

Order Denying Rehearing

Extract from the Minutes of September 4,1959.

No. 17534

E. P. B a bn es , J. C. C abson , J. J e l k s and J. R obektson ,

T h e C ity oe Gadsden , A labama , e t a l .

It is ordered by the Court that the petition for rehearing

filed in this cause be, and the same is hereby, denied.

“Rives, Circuit Judge, dissents.”

42

APPENDIX B

Title 42, United States Code §1455

Local determinations.—Contracts for loans or capital

grants shall be made only with a duly authorized local

public agency and shall require that—

(a) The urban renewal plan for the urban renewal area

be approved by the governing body of the locality in which

the project is situated, and that such approval include

findings by the governing body that (i) the financial aid to

be provided in the contract is necessary to enable the project

to be undertaken in accordance with the urban renewal plan;

(ii) the urban renewal plan will afford maximum oppor

tunity, consistent with the sound needs of the locality as a

whole, for the rehabilitation or redevelopment of the urban

renewal area by private enterprise; and (iii) the urban

renewal plan conforms to a general plan for the develop

ment of the locality as a whole;

(b) When real property acquired or held by the local

public agency in connection with the project is sold or

leased, the purchasers or lessees and their assignees shall

be obligated (i) to devote such property to the uses specified

in the urban renewal plan for the project area; (ii) to begin

within a reasonable time any improvements on such prop

erty required by the urban renewal plan; and (iii) to com