Taylor v. W.L. Sterrett Petition for Rehearing of the Denial of Attorney's Fees

Public Court Documents

April 3, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Taylor v. W.L. Sterrett Petition for Rehearing of the Denial of Attorney's Fees, 1981. 7d4fb4c7-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ee54d115-afd9-412a-bf6c-ff700af46afe/taylor-v-wl-sterrett-petition-for-rehearing-of-the-denial-of-attorneys-fees. Accessed March 11, 2026.

Copied!

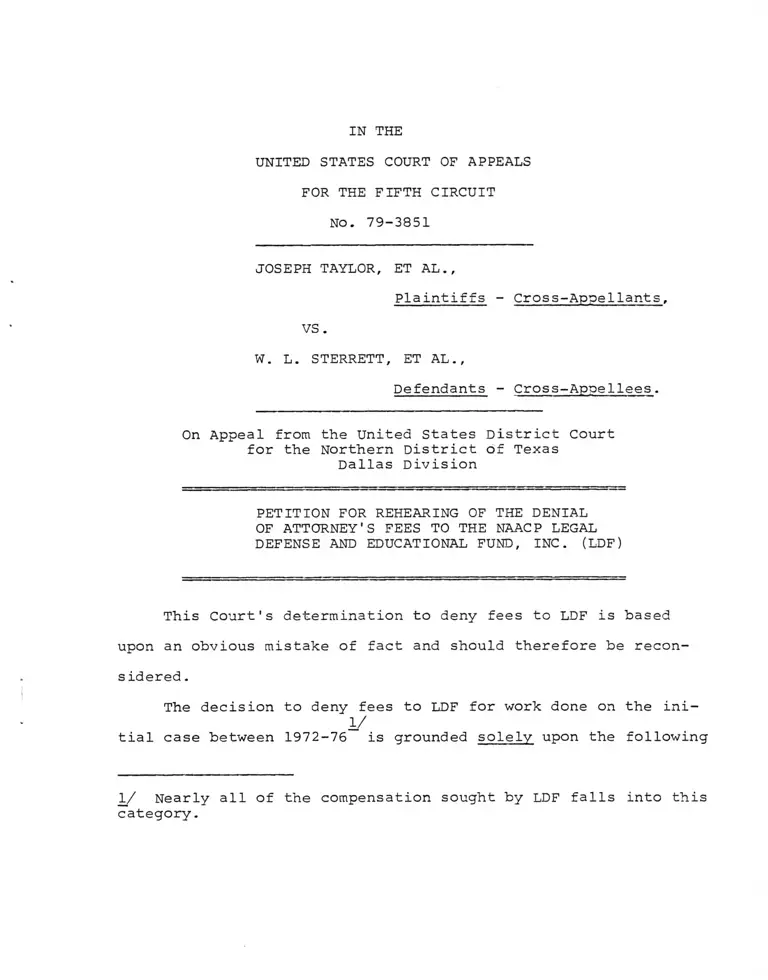

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 79-3851

JOSEPH TAYLOR, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs - Cross-Appellants,

V S .

W. L. STERRETT, ET AL.,

Defendants - Cross-Apoellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Texas

Dallas Division

PETITION FOR REHEARING OF THE DENIAL

OF ATTORNEY'S FEES TO THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. (LDF)

This Court's determination to deny fees to LDF is based

upon an obvious mistake of fact and should therefore be recon-

s idered.

The decision to deny fees to LDF for work done on the ini-

1 /tial case between 1972-76 is grounded solely upon the following

1/ Nearly all of the compensation sought by LDF falls into this

category.

factual premise:

In the case under consideration, attorney's fees for the initial case

had been denied as late as July 20,

1976 (date of the last amended order

of the District Court); this denial

was never appealed. The initial seg

ment of this case had, therefore, been

concluded on that date....

Slip. op. at 5180.

With all respect, this statement is simply inaccurate. Were

it accurate, LDF would never have prosecuted this appeal. We fully

recognize that the denial of attorney's fees on July 20, 1976

would have precluded an award of fees under the Civil Rights

Attorney's Fees Act of 1976 (effective October 19, 1976) for

nearly all of the hours claimed by LDF. However, there was

no such denial of attorney's fees in this case.

Annexed hereto as Appendix A is a copy of the district

court's Amended Order of July 20, 1976. It does not say a word

about attorney's fees. Indeed, LDF did not even move for fees

at that time. Thus, there is simply no factual basis for the

Court's statement that fees had been denied as late as July 20,

1976. That statement — crucial to the Court's holding denying

fees to LDF — is simply a mistake. In scrutinizing this volumi

nous 10 year-old record, an error was made.

LDF did not move for fees covering the 1972-76 period of the

original case until July 3, 1979, well after the effective date

2

of the Act. The propriety of waiting until then to seek fees

is clearly established by Corpus v. Estelle, 605 F.2d 175

(5th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 445 U.S. 919 (1980)(counsel

waited until 1977 to seek fees for the original case, which

had been concluded in 1971), and is not questioned by the

2/Court's opinion in this case. Slip. op. at 5180.

The only distinction between this case and Corpus is that

here the district court denied fees at one very early point

in the case: it's initial decision of June 5, 1972. Taylor

v. Sterrett, 344 F.Supp. 411, 423 (N.D. Tex. 1972). We fully

agree that this determination precludes the granting of fees

3/

for work done prior to that date. However, the initial case

continued long after June 5, 1972, encompassing two appeals

decided on the merits, a third appeal dismissed by this Court,

and various activities in the district court. LDF played a

major role in these post-June 5, 1972 proceedings in the original

case, including presentation of oral argument for plaintiffs on

the first appeal. However, LDF did not seek fees for these pro-

2/ The date of the fee applications in both Corpus and this case

did not affect pendency as of October 19, 1976, because in both

cases relief proceedings were pending at that time. Slip op. at 5180.

3/ A small portion of the 70.6 hours claimed by Mr. Bass' affi

davit falls within this period.

3

ceedinqs until July 3, 1979, and the district court did not

rule upon our right to fees for these proceedings until it

entered its order denying fees on October 23, 1979.

At the outset of the Court's opinion, during a discussion

of the history of the case, reference is made to an Amended

Judgment entered by the district court upon remand after the

first appeal. Slip. Op. at 5177. That Amended Judgment,

signed on November 1, 1974, also does not say a word about

attorney's fees. A copy is annexed hereto as Appendix B.

The Court further notes in this early passage of the

opinion that "[t]he denial of attorney's fees in the original

judgment was not questioned either on the first or the second

appeal. The two amended judgments neither reserved the question

nor altered the denial of fees." Slip. op. at 5177. These state

ments are true, but they are also irrelevant under the law of

this Circuit. Neither the 1974 Amended Judgment nor the 1976

Amended Order actually denied attorney's fees for the post-

June 5, 1972 portion of the original case, as the Court mis

takenly declares in announcing its holding (slip. op. at 5180)?

and, as the Court recognizes (ibid.), in this Circuit fees may

not be denied unless the district court had "finally disposed"

of the attorney's fee issue prior to the effective date of the

Act. The documents annexed to this petition obviously did not

"finally dispose" of the question of attorney's fees for post-

4

June 5, 1972 work on the original case.

In this Circuit, there is no time limitation for seeking

attorney's fees under 42 U.S.C. §1988. Corpus v. Estelle,

supra; Knighton v. Watkins, 616 F.2d 795, 797 (5th Cir. 1980);

Van Ooteghem v. Gray, 628 F.2d 488, 497 (5th Cir. 1980); Jones

v. Dealers Tractor and Equipment Co., 634 F.2d 180, 181-82

(5th Cir. 1981). LDF was entirely justified in requesting

fees in 1979, once the Act had been passed and our entitlement

to fees for work done after June 5, 1972 was clear. Since prior

to the Act's passage the district court never denied fees for

post-June 5, 1972 work on the original case, LDF is entitled to

fees for that period.

Respectfully submitted

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

JOEL BERGER

CHARLES STEPEHN RALSTON

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

CROSS-APPELLANTS

5

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, JOEL BERGER, hereby certify that on April 3 , 1981,

I served a copy of the within petition for rehearing upon

counsel for defendants - cross-appellees by depositing same

in the United States mail, first class mail, postage prepaid,

addressed as follows: Earl Luna, Esq. and Thomas v. Murto, III,

Esq., Luna & Murto, 2416 LTV Tower, 1525 Elm Street, Dallas,

Texas 75201.

APPENDIX A

TAYLOR v. STERRETT 5174

Joseph TAYLOR et al., Plaintiffs-Ap-

pellees, Cross Appellants,

v.

W. L. STERRETT et al..

Defendants-Appellees,

Garry Weber, County Judge of Dallas

Co., Jim Jackson, Nancy Judy, Jim

Tyson, Roy Orr, etc., Defendants-Ap-

pellants, Cross Appellees.

No. 79-3851.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit.

Unit A

March 25, 1981.

Prior to receipt of mandate on appeal

from interlocutory orders, 600 F.2d 1135,

the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas, Sarah Tilgh-

man Hughes, J., awarded attorney fees

under civil rights attorney fee statute to

counsel for plaintiff who successfully

challenged conditions in Dallas County

jail, and appeal was taken. The Court of

Appeals, Coleman, Circuit Judge, held

that: (1) since orders on appeal were only

interlocutory, district court was not di

vested of jurisdiction as to award for

prior orders; (2) since fee request for

initial proceedings had been denied prior

to effective date of fee statute, fees could

be awarded only for work relating to

supplemental proceedings stage, which

was pending on effective date of the fee

statute and up to time work began on

matters relating to the interlocutory or

der; (3) plaintiff did not prevail on any

matters pertaining to the interlocutory or

subsequent orders where it was held that

district court should have declined juris

diction; and (4) it was not abuse of dis

cretion to deny fees to legal service or

ganization.

Affirmed in part; reversed and re

manded in part.

1. Federal Courts <s=>681

General rule is that a district court is

divested of jurisdiction on filing of notice

of appeal with respect to any matters

involved in the appeal; however, where

an appeal is allowed from an interlocuto

ry order, the district court may still pro

ceed with the matters not involved in the

appeal.

2. Civil Rights <3=̂ 13.17

Since appeal from district court or

ders, in civil rights action challenging

conditions in Dallas County jail, ordering

commissions’ court to buy land and adapt

this land for a new jail and directing

sheriff not to accept new inmates when

present jail was full, involved only such

orders and subsequent ones, the district

court was divest of jurisdiction only as to

matters relating to such interlocutory or

ders and was not deprived of jurisdiction

to award attorney fees for work relating

to prior orders. 28 U.S.C.A. § 1292(a)(1),

42 U.S.C.A. § 1988.

3. Civil Rights 13.17

Federal Courts <s=830

Decision to award attorney’s fees un

der civil rights attorney fee statute is

delegated to the discretion of the trial

court, and its decision will not be dis

turbed absent showing of abuse. 42 U.S.

C.A. § 1988.

4. Civil Rights «=> 13.17

Although it is discretionary whether

to award fees under civil rights attorney

fee statute, a successful civil rights plain-

Synopses, Syllabi and Key Number Classification

COPYRIGHT © 1981, by WEST PUBLISHING CO.

The Synopses, Syllabi and Key Number Classifi

cation constitute no part of the opinion of the court.

5175 TAYLOR v. STERRETT

tiff should ordinarily recover an attor

ney’s fee unless special circumstances

would render such award unjust. 42 U.S.

C.A. § 1988.

5. Civil Rights 13.17

For purpose of amended version of

civil rights attorney fee statute, which

applies to all cases pending on the effec

tive date, a case is considered “ pending”

if a motion for fees for the initial case is

unresolved or is on appeal on October 19,

1976, the effective date of the amended

version. 42 U.S.C.A. § 1988.

See publication Words and Phrases

for other judicial constructions and

definitions.

6. Civil Rights >3= 13.17

Although August 15, 1974 attorney

fees motion was still pending on effective

date of 1966 amendment to civil rights

attorney fee statute, since that motion

requested fees for time spent in enforce

ment proceedings only it could not be

used to make the entire Civil Rights Act

suit pending for purpose of fee award.

42 U.S.C.A. § 1988.

7. Civil Rights ®= 13.17

Since injunctive relief in Civil Rights

Act suit challenging conditions in Dallas

County jail had been affirmed prior to

effective date of 1976 amendment to civil

rights attorney fee statute and only sup

plemental enforcement proceedings were

pending on effective date of the amend

ment and preamendment final judgment

denying fee request had not been appeal

ed fees could be awarded under the stat

utes only for work relating to supplemen

tal proceeding stage of the case between

June 24, 1974 and the time work began

on matters relating to interlocutory or

ders which were on appeal at time of the

motion; however, if attorney fee issue

for initial case had not been decided on

effective date of the amendment such

unresolved issue apparently would have

sufficed to make entire case pending. 42

U.S.C.A. § 1988.

8. Civil Rights >3=13.17

Proper focus in determining whether

a movant is the “ prevailing party” for

purpose of award of attorney fees under

the civil rights attorney fee statute is

whether movant has been successful on

the central issue as exhibited by the facts

that he has acquired the primary relief

sought, and fact that compliance is volun

tary is no justification for holding that a

party did not prevail. 42 U.S.C.A. § 1988.

See publication Words and Phrases

for other judicial constructions and

definitions.

9. Civil Rights >3=13.17

Where although central issue on pro

ceeding supplemental to issuance of in

junctive relief in Civil Rights Act suit

challenging conditions in Dallas County

jail was to ensure compliance with the

judgment and primary relief sought in

such proceedings was compliance and up

until April order ordering commissions’

court to buy land and adapt this land for

new jail plaintiffs were prevailing parties

and such order even stated that sheriff

was in compliance with “ most of the or

ders,” the plaintiff did not “prevail,” for

purpose of civil rights attorney fee stat

ute, on any matters pertaining to the

April order or any subsequent order as it

was held that the district court should

have declined jurisdiction. 42 U.S.C.A.

§ 1988.

See publication Words and Phrases

for other judicial constructions and

definitions.

TAYLOR v. STERRETT 5176

10. Civil Rights 13.17

Time spent by more than one attor

ney where only one attorney is needed

may be discounted in awarding attorney

fees under civil rights attorney fee stat

ute. 42 U.S.C.A. § 1988.

11. Civil Rights <&=> 13.17

Refusal to award attorney fees to

legal service organization in Civil Rights

Act was not abuse of discretion given

small amount of compensable time

claimed, i. e., approximately ten hours,

duplicative nature of the work and fact

that district court specifically found that

organization’s services here not neces

sary. 42 U.S.C.A. § 1988.

12. Civil Rights <3= 13.17

Time spent by civil rights plaintiff

counsel opposing intervention by proper

ty owners protesting proposed conversion

of vacant hospital into minimum security

jail was excluded in computing fee award

under Civil Rights Attorney Fee Act as

opposition was irrelevant to goal of ob

taining compliance with injunction order,

which issued prior to effective date of fee

statute, and attempted intervention was

also a circumstance beyond initial defend

ant’s control. 42 U.S.C.A. § 1988.

13. Civil Rights 13.17

District court’s failure to make spe

cific findings on the Johnson factors in

passing on motion for attorney fee award

under civil rights attorney statute could

be excused under the Davis reasons as

plaintiff presents a memoranda as to ap

plication of Johnson factors and award of

fees to private counsel and denial of fees

to legal service organization did not rep

resent any palpable abuse of discretion.

42 U.S.C.A. § 1988.

Appeals from the United States Dis

trict Court for the Northern District of

Texas.

Before BROWN, COLEMAN and GEE,

Circuit Judges.

COLEMAN, Circuit Judge.

This case was originally brought as a

challenge to conditions in the Dallas

County, Texas, jail system. Once more it

appears here after protracted litigation

over a period of nearly ten years, includ

ing four previous appeals to this Court.

After the final appellate decision on the

merits, the District Court awarded fees

to John Jordan, an attorney for the plain

tiff class, for time spent on the case from

June 11, 1974, to July 30, 1979. It denied

an award of fees to Dallas Legal Services

Foundation, Inc. (hereinafter DLSF) and

to NAACP Legal Defense and Education

al Fund, Inc. (hereinafter LDF), two or

ganizations which had also participated

to some extent in behalf of the plaintiff

class.

The defendants, the Commissioners

Court of Dallas County, challenge the

award of fees to Jordan on grounds that

(1) the District Court had no jurisdiction

to award fees while the case was on

appeal; (2) only supplemental enforce

ment proceedings were pending on the

effective date of § 1988; (3) plaintiffs did

not prevail in these proceedings; and (4)

if plaintiffs could be considered to have

prevailed in the supplemental proceed

ings, Jordan should only recover fees for

time spent between June 11, 1974, and

December 31, 1976. DLSF and LDF

cross appeal, arguing that (1) non-profit

legal service organizations, including fed

erally-funded projects, may recover fees

on the same basis as private attorneys;

5177 TAYLOR v. STERRETT

(2) the District Court failed to make find

ings on the criteria set forth in Johnson

v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488

F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974); and (3) there are

no special circumstances warranting deni

al of fees.

We affirm the denial of fees to LDF

and DLSF. We reverse and remand the

award to Jordan for a reduction of

amount allowed him.

I. History

This was a class action by inmates of

the Dallas County Jail against the Dallas

County Commissioners Court and other

county officials, challenging the condi

tions there as violative of the Constitu

tion and of Texas law. It initially filed

on October 26, 1971. The complaint re

quested attorney’s fees on behalf of John

Jordan, an employee of DLSF (Jordan

went into private practice in June, 1974,

but the Court requested that he continue

to represent the plaintiff class). After

trial on the merits, the District Court in a

memorandum opinion and judgment Hied

June b, ivr2, held that the jail did not

comply with state law and ordered modi

fication of the physical facilities and

changes in jail procedure: attorney’s fees

were denied. Tavlor v. Sterrett. 344

h'.Supp. 411, 421. 423 (N.D.Tex.1972).

Defendants' appealed.

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit affirmed

in part, vacated in part, and remanded

for exercise of a retained jurisdiction.

Taylor v. isterrett, 499 F.iid 367, 369 (5th

Cir. 1974), cert, denied sub nom. 420 U.S.

983, 95 S.Ct. 1414, 43 L.Ed.2d 665 (1975).

On remand, the District Court entered an

amended judgment containing the re

quired changes. Defendants again ap

pealed. On this ppppql thp Fifth

modified and affirmed part of the

amended lodgment. and vacated and re

manded part of it. Taylor v. Sterrett,

532 F.2d 462, 484 (5th Cir. 1976). On July

20, 1976, the District Court enterecT’an

amended order conforming to the appel-

There was no appeal fromlate decision,

this amended judgment.

appe

fra

"TTuTcIenial of

attorney's fees in ihe original ludgmenT

was not questioned either on the first or

me second appeal. The two amended

judgments neither reserved the miestio

nor altered the denial of fees.

ar

¥

Enforcement proceedings began on

June 24, 1974. The defendants were or

dered to file reports on their progress at

specified intervals. At times, plaintiffs

would respond, the Court would hold

hearings on the reports, and would issue

an order commenting on the report and

identifying topics to be discussed in the

next report. On August 15, 1974, Jordan

filed a motion for attorney’s fees for time

spent in preparation for defendants’ Au

gust 15, 1974, report and for subsequent

proceedings. Apparently, this motion

was never acted upon by the District

Court.

In 1976, two groups of property owners

protesting the proposed conversion of a

vacant hospital into a minimum security

jail sought intervention in the federal

court case. Plaintiffs opposed this inter

vention. The District Court denied inter

vention, but, upon defendants’ motion,

joined both as third-party defendants.

The Fifth Circuit vacated this order of

joinder. The challenges were then tried

in state court with the county officials

prevailing. Oak Lawn Preservation Soci

ety v. Bd. o f Mgrs. o f Dallas Cty. Hosp.,

566 S.W.2d 315, 318 (Tex.Civ.App.1978),

writ re f ’d n. r. e.

On February 1, 1977, the plaintiffs

filed a § 1988 motion for attorney’s fees

for time spent on the case from October

19, 1976 to the end of the case. On

February 8, 1977, the District Court, dis-

rs 'S 'e / —

H/- r S e * * * " r e .s* ',s,*3

o rAe rt7V /-/ITS -r

TAYLOR v. STERRETT 5178

appointed with defendants’ progress, ap

pointed a special master to gather infor

mation concerning jail facilities and oper

ations. The special master’s report was

filed April 15, 1977. The county respond

ed, pointing out that Texas had estab

lished an agency to promulgate and en

force jail standards, and requested the

Court to decline to retain further juris

diction of the case. The Court’s April 27

order (entered as a separate order May 12

upon defendants’ request) approved the

special master’s report, ordered the Com

missioners’ Court to buy land and adopt a

plan for a new jail within three months,

and directed the sheriff not to accept new

inmates when the present jail was full to

capacity. Defendants then appealed

from these two orders. During the pend

ency of this appeal, the enforcement pro

cedure continued as before.

Jordan, Stanley Bass, LDF staff attor

ney, and Betsy Julian, DLSF staff attor

ney, filed an amended motion for attor

ney’s fees on July 3, 1979, requesting fees

for services rendered from October 26,

1971, future services, and past and future

appeals. Each attorney filed affidavits

and memoranda detailing time spent on

the case and discussing application of the

Johnson factors. The hearing on the mo

tions was held August 29, 1979.

On August 16, 1979, the Fifth Circuit

rendered its opinion on the county’s latest

appeal. Convinced that the District

Court’s role in improving the Dallas

County jail had been completed and that

control of the jail system should be re

turned to state and local officials, the

Court vacated the April 27 and May 12

orders and all other orders and stays still

in effect. The case was remanded “ with

directions to the district court to discon

tinue the further exercise of its retained

jurisdiction and to dismiss the cause.”

Taylor v. Sterrett, 600 F.2d 1135, 1141,

1145-46 (5th Cir. 1979).

On October 23, 1979, the District Court

found that the case had been pending on

the effective date of § 1988, that the

plaintiff class had prevailed, and awarded

fees of $26,417.50 to John Jordan for all

time spent on the case from June 11,

1974, to July 30, 1979, and denied fees to

DLSF and LDF. DLSF was denied fees

because the Court found, inter alia, that

there was no need for its services in that

period because Jordan was capable of and

did continue as plaintiffs’ primary coun

sel at the Court’s request. No reason

was given for denying fees to LDF. The

mandate pursuant to our August 19 opin

ion reached the District Court on October

25 and the case was dismissed on October

29.

II. Jurisdiction o f the District Court

[1,2] On appeal of the April 27 and

May 12 orders, the Court held that these

orders were appealable under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1292(aXl) (1976) as interlocutory orders

modifying the 1972 injunction and, “ nec

essarily” construing the orders as deny

ing defendants’ request that the district

court decline to retain jurisdiction, as re

fusals to dissolve or modify an injunction.

600 F.2d at 1140, 1140 n.10. Under this

construction, it appears the appeal of the

April 27 and May 12 orders involved only

those orders and subsequent ones; previ

ous orders were not involved in the ap

peal. It is the general rule that a district

court is divested of jurisdiction upon the

filing of the notice of appeal with respect

to any matters involved in the appeal. 9

Moore’s Federal Practice H 203.11, at 3-44

(2d ed. 1980). However, where an appeal

is allowed from an interlocutory order,

the district court may still proceed with

matters not involved in the appeal. 9

Moore’s Federal Practice, supra, at 3-54

(2d ed. 1980). Therefore, the District

/■ > /*/ 7972- f o s fhe / r ' f S 7/-72*

y m 79 7 </

a + e * * / " / / ‘'*/**"? -for 7?r?-7tT

/ t o f — f + r * * > / / * * / < * « / , « >*r

5179 TAYLOR v. STERRETT

Court was divested of jurisdiction only as

to matters relating to the April 27 and

May 12 orders and subsequent orders and,

for that reason, fees cannot be recovered

for work relating to these orders. The

Court still had jurisdiction as to previous

orders and could award fees for work

relating to these prior orders.

III. Attorney’s Fees

A. 42 U.S.C. § 1988

[3,4] 42 U.S.C. § 1988, as amended

October 19, 1976, provides in pertinent

part:

. . . In any action or proceeding to

enforce a provision of sections 1981,

1982, 1983, 1985, and 1986 of this title,

Title IX of Public Law 92-318, or in

any civil action or proceeding, by or on

behalf of the United States of America,

to enforce, or charging a violation of, a

provision of the United States Internal

Revenue Code, or title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, the court, in its

discretion, may allow the prevailing

party, other than the United States, a

reasonable attorneys’ fees as part of

the fees.

This Court has held that the decision to

award attorney’s fees is delegated to the

discretion of the trial court, and its deci

sion will not be disturbed absent an abuse

of that discretion. See, e. g., Harkless v.

Sweeny Independent School District, 608

F.2d 594, 596 (5th Cir. 1979); Morrow v.

Dillard, 580 F.2d 1284, 1300 (5th Cir.

1978). Nonetheless, a successful civil

rights plaintiff should ordinarily recover

an attorney’s fees under § 1988 unless

special circumstances would render such

an awardunjust. S.Rep.No.94 1011, 94th

1. The August 15, 1974, attorney’s fees motion

was still pending on October 19, 1976, but that

motion requested fees for time spent in the

Cong., 2d Sess., 4, reprinted in [1976]

U.S.Code Cong. & Ad.News 5908, 5912; e.

g., Robinson v. Kimbrough, 620 F.2d 468,

470 (5th Cir. 1980); Crowe v. Lucas, 595

F.2d 985, 993 (5th Cir. 1979).

B. Pendency

The amended version of § 1988 applies

to all cases pending on the effective date.

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678, 694 n.23,

98 S.Ct. 2565, 2575 n.23, 57 L.Ed.2d 522

(1978), quoting H.R.Rep.No.94- 1558, p. 4

n.6 (1976); Escamilla v. Santos, 591 F.2d

1086, 1088 (5th Cir. 1979). A determina

tion of pendency here will effectively de

cide the outcome of this appeal.

[5,6] A case is considered to be pend

ing if a motion for attorney’s fees for the

initial case in unresolved or is on appeal

on October 19, 1976. Gore v. Turner, 563

F.2d 159, 163 (5th Cir. 1977); Brown v.

Culpepper, 559 F.2d 274, 276 (5th Cir.

1977); Rainey v. Jackson State College,

551 F.2d 672, 676 (5th Cir. 1977).1 How

ever, according to Escamilla v. Santos,

591 F.2d at 1088, and Peacock v. Drew

Municipal Separate School District, 433

F.Supp. 1072, 1075-76 (N.D.Miss.1977)

cited with approval in Escamilla, only the

supplemental proceedings to enforce com

pliance with the District Court’s judg

ment were pending on October 19, 1976.

According to Peacock :

The mere pendency on the date of

enactment of an attorney fees act of

supplemental proceedings to effectuate

a prior final judgment [which had in

cluded a denial of attorney’s fees] is

not, in our opinion, sufficient to con

vert an action into such a “pending

action” as to warrant an award of at-

enforcement proceedings only and, therefore,

cannot be used to make the entire case pend

ing.

TAYLOR v. STERRETT 5180

torney fees under such act pursuant to

Bradley-type retroactive application of

the Act.

433 F.Supp. at 1075. Peacock went on to

say that if a party prevailed in supple

mental proceedings which were pending

on the effective date, then attorney’s fees

could be awarded for the supplemental

proceedings, but only for those proceed

ings. Id. at 1076-77. Similarly, this

Court, in Escamilla, noted that pendency

of a motion concerning appellant’s failure

to comply with a consent decree was in

the nature of a supplemental proceeding

to effectuate a prior consent judgment

and was, therefore, insufficient to sup

port award of attorney’s fees for the

initial case. 591 F.2d at 1087-88. A

final judgment denying fees had already

been rendered prior to passage of the

amended version of § 1988. Id. at 1087.

[7] la . the case under consideration.

attorney’s fees for the initial case Viarl

been denied as late as . In ly 9 0 1Q7« M a t o

,of the last amended order of the District

Court); this denial was never appealed.

The initial segment of this case had,

therefore, been concluded on that date;

the only pending active issue on October

19, 1976, was the supplemental enforce

ment proceedings begun on June 24, 1974,

with the District Court ordering defend

ants to begin compliance with portions of

the June 5, 1972, judgment.

Corpus v. Estelle, 605 F.2d 175 (5th Cir.

1979), cert, denied sub nom. Estelle v.

Corpus, 445 U.S. 919, 100 S.Ct. 1284, 63

L.Ed.2d 605 (1980), may appear to be the

contrary since attorney’s fees were

awarded for work done in the initial case

and in the supplemental proceedings even

though the initial case had been conclud

ed in 1971. 605 F.2d at 176. However,

attorney’s fees apparently had not been

requested until conclusion of the enforce

ment proceedings. Id. at 176-77. Thus,

it is necessary, according to Robinson v.

Kimbrough, 620 F.2d 468 (5th Cir. 1980),

to determine whether the attorney’s fees

issue has been decided for the initial case;

if this question has not been decided,

then apparently this unresolved issue is

sufficient to make the entire case pend

ing. Id. at 475, citing, inter alia, Corpus

v. Estelle. On the other hand, if the

Court has finally disposed of all issues,

including the attorney’s fee issue, prior to

the effective date of § 1988, then supple

mental proceedings to effectuate a prior

final judgment are independent of the

original action and cannot be used to

make the entire case pending. Id. At

torney’s fees may then be awarded only

if these proceedings are pending on the

effective date. Id.

Miller v. Carson, 628 F.2d 346 (5th Cir.

1980), although urged by appellee at oral

argument as authority for the proposition

that a case should not be divided into the

initial and supplemental proceeding stage

in order to determine pendency, provides

no support for appellee’s position. The

question in Miller was whether the plain

tiffs were prevailing parties sufficient to

support an award of attorney’s fees for

work done on postjudgment motions', the

issue of whether postjudgqnent proceed

ings would be sufficient to make the en

tire case pending was not presented to

the Court. Id. at 347-48.

Therefore, fees may only be awarded

here for work relating to the supplemen

tal proceeding stage of the case between

June 24, 1974, and the time work began

on matters relating to the April 27 order.

C. Prevailing Party

[8] Section 1988, by its terms, permits

an award of attorney’s fees only to a

“ prevailing party” . The question here,

since only the supplemental proceedings

5181 TAYLOR v. STERRETT

were pending, is whether appellees pre

vailed in those proceedings. As Iranian

Students Association v. Edwards, 604

F.2d 352 (5th Cir. 1980), explains, the

proper focus is whether the plaintiff has

been successful on the central issue as

exhibited by the fact that he has acquired

the primary relief sought. Id. at 353.

The fact that compliance is voluntary is

no justification for holding that a party

did not prevail. Robinson v. Kimbrough,

620 F.2d at 475-76 (5th Cir. 1980);

Brown v. Culpepper, 559 F.2d at 277 (5th

Cir. 1977); S.Rep.No.94-1011, supra, at 5.

[9] The central issue of the supple

mental proceedings here was to ensure

compliance with the district court judg

ment; the primary relief sought in these

proceedings was compliance. Up until

the April 27 order, the appellees were the

prevailing parties in that compliance was

being obtained; the April 27 order even

stated that the sheriff was in compliance

with “ most of the orders” contained in

the June 5, 1972 order. Record, V. 6, p.

1480. As this Court said in the appeal of

the April 27 and May 12 orders: “ The

objects sought to be accomplished in the

original suit have been accomplished.

That which was sought to be remedied

has now been remedied.” 600 F.2d at

1141. Appellees did not prevail on any

matters pertaining to the April 27 order

or any subsequent orders because it was

held that the District Court should have

declined jurisdiction.

D. Denial o f Fees to LDF and DLSF

[10,11] The greatest portion of the

time claimed by Stanley Bass, LDF staff

attorney, in his 1979 affidavit for attor

2. This holding in no way based on the fact that

the DLSF is federally funded and that the LDF

is a privately-funded civil rights organization.

Thompson v. Madison County Board of Educa-

ney’s fees was spent on the appeal of the

initial case and, for that reason, is non-

compensable. However, a small portion

of the time claimed may relate to the

supplemental proceedings (it is impossible

to tell from Bass’s affidavit); if some of

this time was expended in relation to the

enforcement proceedings, it was spent

only in reading papers of the case and in

correspondence and telephone conversa

tions with co-counsel and court clerks.

Record, V. 8, p. 1916. The same is true of

the time claimed by Betsy Julian, DLSF

staff attorney, who was assigned to the

case in September, 1976; after eliminat

ing work relating to the April 27 and

subsequent orders, the remaining 9.3

hours was spent in reading reports filed

by defendants, preparing for and attend

ing hearings on these reports, and confer

ring with co-counsel. According to John

son v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.,

time spent by more than one attorney

where only one is needed may be dis

counted. 488 F.2d at 717. Given the

small amount of compensable time

claimed, the duplicative nature of the

work, and the fact that the District Court

specifically found the DLSF attorney was

not necessary to the case, Record, V. 8, p.

1936, we hold that the District Court did

not abuse its discretion in awarding no

fees to LDF and DLSF and we affirm

the denial of fees.2

E. Award of Fees to Jordan

[12,13] The fee award to Jordan must

be reduced so as to include only time

spent in the supplemental proceedings

from June 24, 1974, to December 3, 1976

(work done after this date related to mat

ron, 496 F.2d 682, 689 (5th Cir. 1974); Fairly v.

Patterson. 493 F.2d 598, 606 (5th Cir. 1974);

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d

534, 538-39 (5th Cir. 1970).

TAYLOR v. STERRETT 5182

ters involved in the April 27 order).

Time spent on appeal of the initial case

and on the intervention matters should

be excluded. Appellee’s opposition to in

tervention was irrelevant to the goal of

obtaining compliance; the attempted in

tervention was also a circumstance be-

3. The District Court’s failure to make specific

findings on the Johnson factors may be ex

cused for the reasons set forth in Davis v. City

of Abbeville, 633 F.2d 1161 (5th Cir. 1981).

Since appellee did present memoranda as to the

application of the Johnson factors and since the

yond appellants’ control. See Robinson v.

Kimbrough, 620 F.2d at 478 (5th Cir.

1980). On remand, the District Court

must reduce Jordan’s award in accord

ance with the guidelines here announced.3

AFFIRMED in part; REVERSED and

REMANDED in part.

award of fees to Jordan and denial of fees of

LDF and DLSF does not represent any “ palpa

ble abuse of discretion,” we are unable to hold

that the District Court failed or refused to con

sider the Johnson factors. At 1163.

Adm. Office, U.S. Courts—West Publishing Company, Saint Paul, Minn.

«. i . o*»t» ic t couim Q ^ < 2 f ■

hoittxck ' " 0 I »T «1 C T 0 » r m » »

F I L E D f h s ,

JUL 2 0 t97G

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 'JQSEP-H Mc£LRQY’aR" CL£RK

FOR TI1E NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS BI

DALLAS DIVISION

Deputy

0

(}

0

TAYLOR, ET AL. 0

0

VS 0

0•STERRETT, ET AL. , 0

0

0

0

0

CA 3—5220-B

AMENDED ORDER

On this day came before the Court for

consideration the opinion of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in the

above styled and numbered cause rendered on

June 1, 1976.

In accordance with that- opinion,

paragraph 4 of this Court's November 1, 1974

Order is revised as follows:

4. The Sheriff is directed not to open out

going mail addressed to the courts, prosecuting

attorneys, parole or probation officers,governmental agencies,

members_of the press, and identifiable^attorneys. The

Sheriff is allowed 48 hours to ascertain whether or

not an individual addressed as a member of the

press is in fact such’a press representative.

Inmates wishing to correspond with attorneys must

present the name and address of such an attorney to

the Sheriff at least 48 hours before any corres

pondence to that attorney is mailed for the purpose

of ascertaining whether or not that addressee is

• \

in fact an attorney.

With respect to incoming mail, the Sheriff may

open mail from the courts, prosecuting attorneys.,

parole or probation officers, governmental agencies,

members of the press, and identifiable attorneys,

but only in the presence of the inmate to whom the

correspondence is addressed, and only for the

purpose of determining the presence of contraband,

not for the purpose 'of reading that correspondence.

Press representatives who wish to correspond with

an inmate may be required to identify themselves

and their status in writing before their unread

mail is distributed to the inmate.

Paragraph 8 of this Court’s November

1, 1974 Order is hereby vacated and set aside.

’ ‘ XT IS ..THEREFORE ORDERED, ADJUDGED, AND DECREED

that the Order entered by this Court on November 1,

1974 BE and it hereby IS AMENDED in accordance with

the above provisions.

SIGNED AND ENTERED this ' day of 1976.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

SARAH T. HUGHES

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

DALLAS DIVISION

JOSEPH TAYLOR, ET AL §

V § CIVIL ACTION 3-5220-3

W. L. STERRETT, ET AL §

AMENDED JUDGMENT

On this the L8th day of October, 1974, came on for consideration

the modification of paragraphs 4, 3 and 10 of the judgment of June 5,

1972, directed by the United States Court of Appeals (Fifth Circuit) in

its opinion of August 19, 1974, in the above styled case.

The Court has carefully considered the opinion of the Circuit

Court and the case of Wolff v. McDonnell (Supreme Court 42 LW 5190

June 26, 1974) and the argument of counsel and is of the opinion that '

this Court's judgment of June 5, 1972, should be modified so that

paragraphs 4, 9 and 10 should read as follows:

4. The sheriff is directed not to open mail transmitted

between inmates of the jail and the following persons: courts, prosecu

ting attorney, probation and parole officers, governmental agencies,

lawyers and the press. If, however, there is a reasonable possibility

that contraband is included an the mail, it mav be ODened, but only in

the presence of the inmates.

8. The sheriff is directed not to allow persons to see prisoners

except with the consent or request of the inmate. This has particular

reference to 'cop out' men who have heretofore visited inmates unrepre

sented by counsel for the purpose of plea bargaining. This provision

is not intended to eliminate visits from official investigators engaged

in the efforts to solve crimes or to perform other legitimate duties,

nor is it intended to eliminate,only to limit plea bargaining. The

attention of the District Attorney is particularly called to this

provision.

IT IS 50 ORDERED.

Signed this the 's' day of OtiMhec, 1974.

£ < L IUnited States District Judge

U

/