Motion to Stay Further Proceedings Pending the Decision on Intervenors' Motion for Payment of Attorneys' Fees

Public Court Documents

May 10, 1995

123 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Motion to Stay Further Proceedings Pending the Decision on Intervenors' Motion for Payment of Attorneys' Fees, 1995. 00778794-a146-f011-8779-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ee5c26d8-4200-4125-bf69-65c82f0f1a99/motion-to-stay-further-proceedings-pending-the-decision-on-intervenors-motion-for-payment-of-attorneys-fees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

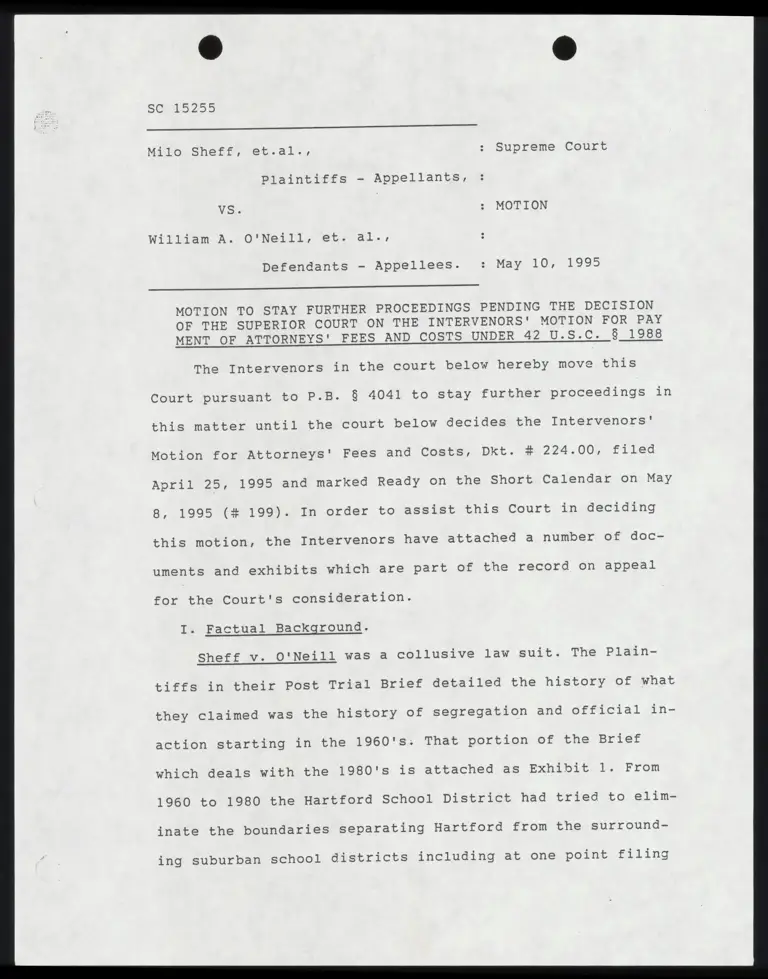

SC 15255

Milo Sheff, et.al., : Supreme Court

Plaintiffs - Appellants,

VS. : MOTION

William A. O'Neill, et. al.,

Defendants - Appellees. : May 10, 1995

MOTION TO STAY FURTHER PROCEEDINGS PENDING THE DECISION

OF THE SUPERIOR COURT ON THE INTERVENORS' MOTION FOR PAY

MENT OF ATTORNEYS' FEES AND COSTS UNDER 42 0.85,C. 5 1988

The Intervenors in the court below hereby move this

Court pursuant to P.B. § 4041 to stay further proceedings in

this matter until the court below decides the Intervenors'

Motion for Attorneys' Fees and Costs, Dkt. # 224.00, filed

April 25, 1993 and marked Ready on the Short Calendar on May

8, 1995 (# 199). In order to assist this Court in deciding

this motion, the Intervenors have attached a number of doc-

uments and exhibits which are part of the record on appeal

for the Court's consideration.

I. Factual Background.

Sheff v. O'Neill was a collusive law suit. The Plain-

tiffs in their Post Trial Brief detailed the history of what

they claimed was the history of segregation and official in-

action starting in the 1960's: That portion of the Brief

which deals with the 1980's is attached as Exhibit 1. From

1960 to 1980 the Hartford School District had tried to elim-

inate the boundaries separating Hartford from the surround-

ing suburban school districts including at one point filing

2

a federal law suit paralleling the action filed in Detroit

known as Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1983). For over

20 years their efforts had been unsuccessful. As the Plain-

tiffs accurately point out, 1983 was a turning point when

Gerald Tirozzi was appointed Commissioner of Education. See,

Exh. 1 at 74. Tirozzi put into motion a series of committees

and studies which developed recommendations for programs

which called for mandatory interdistrict desegregation. See,

Id.<at 75 - 77.

In 1988, the Report on Racial/Ethnic Equity and Deseg-

regation in Connecticut's Public Schools was issued. This

became known as the Tirozzi I Report. As the Plaintiffs cor-

rectly point out, Tirozzi I "[r]epresents a clear acknowl-

edgement of the pressing need for mandatory interdistrict

school integration, and an admission that meaningful deseg-

regation may not be achieved solely through voluntary co-

operation of local school districts". Id. at 77. Tirozzi 1

recommended that if the local school districts did not im-

plement desegregation plans voluntarily, "[t]he State Board

of Education should be empowered to impose a mandatory de-

segregation plan". Id. at 77.

The reception accorded Tirozzi I by the general assem-

bly and the local school districts compares favorably to the

reception given to Gen. Custer by the Native Americans of

the Western Plains. So strong was the opposition that the

Report had to be withdrawn and a watered down version, Tir-

ozzi II was issued in its place. Id. at 78. As the Plain-

3

tiffs dryly note, "The Sheff v. O'Neill lawsuit was filed

shortly after the release of the Tirozzi II Report.” Id. at

78.

From the early 1960's through the release of the Tiroz-

zy II Report, the N.A.A.C.P. supported the efforts first of

the Hartford School Board and later the State Board of Educ-

ation to implement a mandatory desegregation program. When

Tirozzi I failed, the N.A.A.C.P. and the State Board of Ed-

ucation adopted a new approach. Since the general assembly

and the local school districts would not voluntarily adopt

a desegregation plan or empower the State Board to impose

one, the N.A.A.C.P. and the State Board of Education in the

person of Gerald Tirozzi and the Board members would file a

"friendly suit", Sheff v. O'Neill, in which the Friendly Ad-

versaries would join together and invoke the power and auth-

ority of the state judiciary to overcome the resistance of

the general assembly. The purpose of the Sheff Plaintiffs

from the outset was to use the power of the state courts to

empower the Defendants Tirozzi and the State Board to impose

the Defendants' own plan, Tirozzi I, over the objections of

the general assembly and the local school districts. If this

Court will compare the program described in Tirozzi I set

out in Exh. 1 at 77 with the remedies suggested in the same

Brief set out in Exhibit 2, the similarities are obvious. It

is also convenient that as part of the remedy suggested by

the Sheff Plaintiffs, after judgment is entered in favor of

the Sheff Plaintiffs, the court was asked to put the Friend-

4

ly Adversaries in charge of the planning process as the

"oversight group".. See, Exh. 2 at 111.(The oversight group

consists of representatives of the plaintiffs, defendants

(Board of Education, Commissioner and Governor), and attor-

ney representatives. Their purpose is to provide guidance

and to evaluate plans submitted by the [local school dist-

rict] planning group.) Thus, at the end of the Sheff pro-

ceedings, Tirozzi, the State Board and the N.A.A.C.P. would

be empowered to impose Tirozzi I under their direct super-

vision unencumbered by opposition from the general assembly.

Naturally, as inconvenient as it may seem, the Friendly

Adversaries had to make a record. To make this task easier,

they decided to eliminate any parties whose position was

concretely adverse to theirs. This meant that for one of the

few times in history, a desegregation suit was filed in

which the school districts involved were not named as a par-

ty. No school districts, not even Hartford, was named as a

party. This created a problem, however, since although the

local school districts were not to be parties, the Friendly

Adversaries wanted them to be bound by the decision, espec-

ially the remedy. To accomplish this, they invoked the "col-

lateral challenge rule" which was then the law in most fed-

eral circuits, including the Second Circuit, and many

states. Under the collateral challenge rule, if you were

notified of a law suit in which your rights were threatened

and you did not intervene in that law suit to protect your

rights, you were deemed to have waived those rights and if a

5

judgment was rendered which adversely effected your rights,

you were esstopped from collaterally challenging that judg-

ment in a separate action. To cloak Sheff in this procedural

rule, immediately after the action was filed, the Plaintiffs

filed a Motion for Order of Notice in which the Plaintiffs

"Because of the hardship involved in citing in all interest-

ed persons as defendants," asked for an order directing ser-

vice by registered mail upon the 21 suburban school dist-

ricts through the Superintendent of Schools and to the pub-

lic via the print media. What notice was given of, however,

was a law suit in which no relief impacting upon the subur-

ban school district was requested. In fact, until mid-trial,

the Plaintiffs refused to outline precisely what the scope

of the requested relief would be.

During the discovery phase of Sheff, the best witnesses

for the Plaintiffs were their Friendly Adversaries, the Def -

endants. In their Post Trial Brief and Reply Brief, the Plain-

tiffs highlighted some of the most damaging testimony offer-

ed by Commissioner Tirozzi and his successor, Commissioner

Ferandino. "Both defendants Commissioner Vincent Ferandino

and former Commissioner Tirozzi acknowledged the harms of

racial segregation and Commissioner Tirozzi admitted that

both he and the State Board of Education had been aware of

the harmful effects of racial segregation during his tenure

as Commissioner." Plaintiffs' Post Trial Brief at 8. "Defen-

ants also agree with plaintiffs regarding the need for a

multi-district solution or regional school planning." Reply

6

Brief at 51.(citing Ferrandino and Tirozzi depositions) "De-

fendants Ferrandino and Tirozzi both support controlled -

choice [ie. Boston] plans." Reply Brief at 51. (citing de-

positions)

The assistance given by the Defendants to the Plain-

tiffs was not limited to friendly testimony. The remedies

outlined by the Plaintiffs would have abrogated rights and

powers currently reserved to the local school districts by

state statute. Comparing the remedies set out in Exhibit 2,

Student assignment is reserved to the local school districts

under C.G.S. § 10-220, the right to employ teachers is re-

served under C.G.S. § 10-241, control over curriculum and

selection of textbooks is reserved under C.G.S. § 10-221(a)

which also reserves to the local school districts control

over discipline and ultimately, under C.G.S. § 10-220, the

general assembly delegated the power to implement the educ-

ational interests of the state to the local school districts

and not to the Board of Education. The Defendants in Sheff

neglected to cite these or any of the other numerous statu-

tory provisions reserving powers to the local school dist-

ricts in any of the briefs it filed including the State's

Post Trial Brief. Finally, despite the fact that the Plain-

tiffs were clearly asking the court to impose race based

criteria on the local school districts, the Friendly Adver-

saries stipulated that no federal statutes, ie. the 14th

Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, were involved.

Unfortunately for the Friendly Adversaries, within mon-

~

ths of the filing of the Sheff Complaint, the U.S. Supreme

Court took up the collateral challenge rule and voided it.

In Martin v. Wilks, 490 U.S. 755 (1989), the Court ruled

that joinder as a party, not knowledge of a law suit and an

opportunity to intervene, is the method by which potential

parties are bound by a judgment and decree. Id,. at 765.

With this decision, the insulation against a collateral at-

tack by the real parties in interest, the suburban school

districts and the parents, school children and taxpayers in

those districts, was stripped away.

Between December 16, 1992 and February 26, 1993, the

Sheff trial was held. Knowing that the outcome was pre-ord-

ained, representatives of the parents and the school child-

ren did not wait for the trial to end and for judgment to

enter to utilize the opening provided by the Supreme Court

in Wilks. On February 5, 1993, less than one week after the

Sheff Plaintiffs had rested their case without putting on

evidence of de jure discrimination, an action was filed in

the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut en-

titled John Doe v. Weicker, 3:93 CV 233 TFGD. A copy of the

complaint is attached as Exhibit 3. To assist this Court. in

understanding the jurisdictional and legal theories under-

lying this action, attached as Exhibit 4 is a Memorandum in

Support of Motion for a Status Conference which was prepared

and filed to assist the court in quickly understanding what

was at issue. Simply stated, the federal plaintiffs used a

court created procedural device which allowed them to invoke

8

the jurisdiction of the federal court in the first instance

to allow them to intervene in the Sheff proceedings without

submitting them to the jurisdiction of the state court sole-

ly to advise the state court of the federal claims of the

federal plaintiffs and that the federal plaintiffs were re-

serving their right to actually litigate their claims in the

federal forum if the state court issue a ruling adverse to

their interests. The federal plaintiffs followed up their

federal filing with a Motion to Intervene in Sheff, Dkt. No.

206.00, attached as Exhibit 5, along with a Memorandum in

Support, Dkt. No. 207.00, attached as Exhibit 6. The Sheff

Plaintiffs filed a Memorandum in Opposition, Dkt. No.207.50

which is attached as Exhibit 7.

The federal case which was intensely litigated through

the Spring and Summer of 1993 culminated in cross motions

for Declaratory Judgment filed by the plaintiffs and to Dis-

miss by the defendants. The Recommended Ruling on these mot-

ions is attached as Exhibit 8. The district court did dis-

miss, but not on the merits as requested by the defendants.

The court dismissed without prejudice to permit Judge Hammer

to determine what role, if any, the federal plaintiffs would

play in Sheff and to make his ruling.

On December 14, 1993, Judge Hammer heard oral argument

on the Intervenors' Motion to Intervene. At oral argument,

the Intervenors reviewed their federal claims, outlined the

deficiencies in the Sheff proceedings and presented him with

copies of the complaint, principal briefs and the Judgment

9

in the federal case. At that point, the Intervenor's with-

drew their Motion to Intervene.

Two days later on December 16, 1993, the first aborted

final argument took place. Only those familiar with the fed-

eral law suit and the argument that had taken place days be-

fore could have understood what happened. Judge Hammer had

read all of the federal pleadings and briefs. He was partic-

ularly concerned with the alleged lack of adversity in the

case and in an on the record exchange, engaged Attorney Hor-

ton in a discussion as to the adversity between the Plain-

tiffs and the Defendants. At the end of the exchange, Attor-

ney Horton agreed that there was no disagreement between the

Plaintiffs and the Defendants. At this point, Judge Hammer

knew he had a problem on two fronts. First, in view of the

lack of adversity, the probative value of the record was at

best highly speculative. In addition, there was a potential

due process taint which would preclude imposition of any re-

medy impacting non-parties to the litigation. And this was

against the background of a collateral challenge in federal

court that was a virtual certainty.

Judge Hammer's immediate reaction was to bring in an

adverse party, the general assembly. He offered to join

them as party defendants that very day. The Friendly Adver-

saries argued that this was impossible. At that point, Judge

Hammer called a halt to the proceedings to reconsider for

the third time his jurisdiction.

Final, final arguments were held on November 30, 1994

10

and the Judge issue his opinion on April 12, 1995. That

opinion can only be understood against the background of the

collateral challenge in federal court and the final argu-

ment on December 16, 1993. Attached as Exhibit 9 is the In-

tervenors Motion for Order, Dkt. No. 224.00, and the Memor-

andum in Support is attached as Exhibit 10. At pages 9 - 15,

the Intervenors outline the principal areas where they im-

pacted the decision. There is no question in the minds of

the Intervenors that they were the prevailing parties.

II. Legal Grounds.

The legal points and authorities supporting the posi-

tion of the Intervenors are contained in Exhibits 4, 6 and

10 as well as in the briefs attached to the Motion for Order

pending before Judge Hammer. The real issue in this motion

is not legal but practical. Before going forward, should

this Court not wait for all the parties who contributed to

the decision of the court below before it so that it can

have all the arguments presented to Judge Hammer before it?

At this point, by virtue of the withdrawal of the Motion to

Intervene, the Intervenors are not parties. Under federal

law, which dictates the ‘procedure Judge Hammer must apply.

the § 1988 Motion is proper and timely. The Intervenors be-

lieve Judge Hammer will grant their Motion, however, whether

he grants or denies it, it is an appealable ruling. Whether

the Intervenors come up as Appellees or Appellants, their

arguments will be presented to this Court as they were to

Judge Hammer.

Respectfully Submitted,

7 - 7 “ % LZ

~

y = vd NT ay

Z: Robert A. Heghmann

Juris No. 100091

521 W. Avon Road

Avon, CT 06001

(203) 651 - 4611

(203) 651 - 9635 FAX

(Clemco Corporation)

CERTIFICATION

I hereby certify that copies of this Motion and all

Exhibits attached hereto were served on all counsel of

record in accordance with the Practice Book on May 10, 1995.

yd

< 1: ie 4

2 4 Hr aT =,

HL Low, Fo

.

Bs

SC 15255

Milo Sheff, et.al., : Supreme Court

Plaintiffs - Appellants,

VS. : MOTION

William A. O'Neill, et. al..,

Defendants - Appellees. + May 10, 1995

MOTION TO STAY FURTHER PROCEEDINGS PENDING THE DECISION

OF THE SUPERIOR COURT ON THE INTERVENORS' MOTION FOR PAY

MENT OF ATTORNEYS' FEES AND COSTS UNDER 42 U.S.C. § 1988

The Intervenors in the court below hereby move this

Court pursuant to P.B. § 4041 to stay further proceedings in

this matter until the court below decides the Intervenors'

Motion for Attorneys' Fees and Costs, Dkt. # 224.00, £iled

April 25, 1995 and marked Ready on the Short Calendar on May

8, 1995 (# 199). In order to assist this Court in deciding

this motion, the Intervenors have attached a number of doc-

uments and exhibits which are part of the record on appeal

for the Court's consideration.

I. Factual Background.

Sheff v. O'Neill was a collusive law suit. The Plain-

tiffs in their Post Trial Brief detailed the history of what

they claimed was the history of segregation and official in-

action starting in the 1960's. That portion of the Brief

which deals with the 1980's is attached as Exhibit 1. From

1960 to 1980 the Hartford School District had tried to elim-

inate the boundaries separating Hartford from the surround-

ing suburban school districts including at one point filing

2

a federal law suit paralleling the action filed in Detroit

known as Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1983). For over

20 years their efforts had been unsuccessful. As the Plain-

tiffs accurately point out, 1983 was a turning point when

Gerald Tirozzi was appointed Commissioner of Education. See,

Exh. 1 at 74. Tirozzi put into motion a series of committees

and studies which developed recommendations for programs

which called for mandatory interdistrict desegregation. See,

14. at 75 - 717.

In 1988, the Report on Racial/Ethnic Equity and Deseg-

regation in Connecticut's Public Schools was issued. This

became known as the Tirozzi I Report. As the Plaintiffs cor-

rectly point out, Tirozzi I "[r]epresents a clear acknowl-

edgement of the pressing need for mandatory interdistrict

school integration, and an admission that meaningful deseg-

regation may not be achieved solely through voluntary co-

operation of local school districts". Id. at 77. Tirozzi 1

recommended that if the local school districts did not im-

plement desegregation plans voluntarily, "[t]lhe State Board

of Education should be empowered to impose a mandatory de-

segregation plan". Id. at 77.

The reception accorded Tirozzi I by the general assem-

bly and the local school districts compares favorably to the

reception given to Gen. Custer by the Native Americans of

the Western Plains. So strong was the opposition that the

Report had to be withdrawn and a watered down version, Tir-

ozzi II was issued in its place. Id. at 78. As the Plain-

3

tiffs dryly note, "The Sheff v. O'Neill lawsuit was filed

shortly after the release of the Tirozzi II Report." Id. at

78.

From the early 1960's through the release of the Tiroz-

zy II Report, the N.A.A.C.P. supported the efforts first of

the Hartford School Board and later the State Board of Educ-

ation to implement a mandatory desegregation program. When

Tirozzi I failed, the N.A.A.C.P. and the State Board of Ed-

ucation adopted a new approach. Since the general assembly

and the local school districts would not voluntarily adopt

a desegregation plan or empower the State Board to impose

one, the N.A.A.C.P. and the State Board of Education in the

person of Gerald Tirozzi and the Board members would file a

"friendly suit", Sheff v. O'Neill, in which the Friendly Ad-

versaries would join together and invoke the power and auth-

ority of the state judiciary to overcome the resistance of

the general assembly. The purpose of the Sheff Plaintiffs

from the outset was to use the power of the state courts to

empower the Defendants Tirozzi and the State Board to impose

the Defendants' own plan, Tirozzi I, over the objections of

the general assembly and the local school districts. If this

Court will compare the program described in Tirozzi I set

out in Exh. 1 at 77 with the remedies suggested in the same

Brief set out in Exhibit 2, the similarities are obvious. It

is also convenient that as part of the remedy suggested by

the Sheff Plaintiffs, after judgment is entered in favor of

the Sheff Plaintiffs, the court was asked to put the Friend-

4

ly Adversaries in charge of the planning process as the

"oversight group".. See, Exh. 2 at 111.(The oversight group

consists of representatives of the plaintiffs, defendants

(Board of Education, Commissioner and Governor), and attor-

ney representatives. Their purpose is to provide guidance

and to evaluate plans submitted by the [local school dist-

rict] planning group.) Thus, at the end of the Sheff pro-

ceedings, Tirozzi, the State Board and the N.A.A.C.P. would

be empowered to impose Tirozzi I under their direct super-

vision unencumbered by opposition from the general assembly.

Naturally, as inconvenient as it may seem, the Friendly

Adversaries had to make a record. To make this task easier,

they decided to eliminate any parties whose position was

concretely adverse to theirs. This meant that for one of the

few times in history, a desegregation suit was filed in

which the school districts involved were not named as a par-

ty. No school districts, not even Hartford, was named as a

party. This created a problem, however, since although the

local school districts were not to be parties, the Friendly

Adversaries wanted them to be bound by the decision, espec-

ially the remedy. To accomplish this, they invoked the "col-

lateral challenge rule" which was then the law in most fed-

eral circuits, including the Second Circuit, and many

states. Under the collateral challenge rule, if you were

notified of a law suit in which your rights were threatened

and you did not intervene in that law suit to protect your

rights, you were deemed to have waived those rights and if a

5

judgment was rendered which adversely effected your rights,

you were esstopped from collaterally challenging that judg-

ment in a separate action. To cloak Sheff in this procedural

rule, immediately after the action was filed, the Plaintiffs

filed a Motion for Order of Notice in which the Plaintiffs

"Because of the hardship involved in citing in all interest-

ed persons as defendants," asked for an order directing ser-

vice by registered mail upon the 21 suburban school dist-

ricts through the Superintendent of Schools and to the pub-

lic via the print media. What notice was given of, however,

was a law suit in which no relief impacting upon the subur-

ban school district was requested. In fact, until mid-trial,

the Plaintiffs refused to outline precisely what the scope

of the requested relief would be.

During the discovery phase of Sheff, the best witnesses

for the Plaintiffs were their Friendly Adversaries, the Def-

endants. In their Post Trial Brief and Reply Brief, the Plain-

tiffs highlighted some of the most damaging testimony offer-

ed by Commissioner Tirozzi and his successor, Commissioner

Ferandino. "Both defendants Commissioner Vincent Ferandino

and former Commissioner Tirozzi acknowledged the harms of

racial segregation and Commissioner Tirozzi admitted that

both he and the State Board of Education had been aware of

the harmful effects of racial segregation during his tenure

as Commissioner." Plaintiffs' Post Trial Brief at 8. "Defen-

ants also agree with plaintiffs regarding the need for a

multi-district solution or regional school planning." Reply

6

Brief at 51.(citing Ferrandino and Tirozzi depositions) "De-

fendants Ferrandino and Tirozzi both support controlled -

choice [ie. Boston] plans." Reply Brief at 51. (citing de-

positions)

The assistance given by the Defendants to the Plain-

tiffs was not limited to friendly testimony. The remedies

outlined by the Plaintiffs would have abrogated rights and

powers currently reserved to the local school districts by

state statute. Comparing the remedies set out in Exhibit 2,

Student assignment is reserved to the local school districts

under C.G.S. § 10-220, the right to employ teachers is re-

served under C.G.S. § 10-241, control over curriculum and

selection of textbooks is reserved under C.G.S. § 10-221(a)

which also reserves to the local school districts control

® over discipline and ultimately, under C.G.S. § 10-220, the

general assembly delegated the power to implement the educ-

ational interests of the state to the local school districts

and not to the Board of Education. The Defendants in Sheff

neglected to cite these or any of the other numerous statu-

tory provisions reserving powers to the local school dist-

ricts in any of the briefs it filed including the State's

Post Trial Brief. Finally, despite the fact that the Plain-

tiffs were clearly asking the court to impose race based

criteria on the local school districts, the Friendly Adver-

saries stipulated that no federal statutes, ie. the 14th

Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, were involved.

& Unfortunately for the Friendly Adversaries, within mon-

7

ths of the filing of the Sheff Complaint, the U.S. Supreme

Court took up the collateral challenge rule and voided it.

In Martin v. Wilks, 490 U.S. 755 (19892), the Court ruled

that joinder as a party, not knowledge of a law suit and an

opportunity to intervene, is the method by which potential

parties are bound by a judgment and decree. Id,. at 765.

With this decision, the insulation against a collateral at-

tack by the real parties in interest, the suburban school

districts and the parents, school children and taxpayers in

those districts, was stripped away.

Between December 16, 1992 and February 26, 1993, the

Sheff trial was held. Knowing that the outcome was pre-ord-

ained, representatives of the parents and the school child-

ren did not wait for the trial to end and for judgment to

enter to utilize the opening provided by the Supreme Court

in Wilks. On February 5, 1993, less than one week after the

Sheff Plaintiffs had rested their case without putting on

evidence of de jure discrimination, an action was filed in

the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut en-

titled John Doe v. Weicker, 3:93 CV 233 TFGD. A copy of the

complaint is attached as Exhibit 3. To assist this Court. in

understanding the jurisdictional and legal theories under-

lying this action, attached as Exhibit 4 is a Memorandum in

Support of Motion for a Status Conference which was prepared

and filed to assist the court in quickly understanding what

was at issue. Simply stated, the federal plaintiffs used a

court created procedural device which allowed them to invoke

8

the jurisdiction of the federal court in the first instance

to allow them to intervene in the Sheff proceedings without

submitting them to the jurisdiction of the state court sole-

ly to advise the state court of the federal claims of the

federal plaintiffs and that the federal plaintiffs were re-

serving their right to actually litigate their claims in the

federal forum if the state court issue a ruling adverse to

their interests. The federal plaintiffs followed up their

federal filing with a Motion to Intervene in Sheff, Dkt. No.

206.00, attached as Exhibit 5, along with a Memorandum in

Support, Dkt. No. 207.00, attached as Exhibit 6. The Sheff

Plaintiffs filed a Memorandum in Opposition, Dkt. No.207.50

which is attached as Exhibit 7.

The federal case which was intensely litigated through

the Spring and Summer of 1993 culminated in cross motions

for Declaratory Judgment filed by the plaintiffs and to Dis-

miss by the defendants. The Recommended Ruling on these mot-

ions is attached as Exhibit 8. The district court did dis-

miss, but not on the merits as requested by the defendants.

The court dismissed without prejudice to permit Judge Hammer

to determine what role, if any, the federal plaintiffs would

play in Sheff and to make his ruling.

On December 14, 1993, Judge Hammer heard oral argument

on the Intervenors' Motion to Intervene. At oral argument,

the Intervenors reviewed their federal claims, outlined the

deficiencies in the Sheff proceedings and presented him with

copies of the complaint, principal briefs and the Judgment

9

in the federal case. At that point, the Intervenor's with-

drew their Motion to Intervene.

Two days later on December 16, 1993, the first aborted

final argument took place. Only those familiar with the fed-

eral law suit and the argument that had taken place days be-

fore could have understood what happened. Judge Hammer had

read all of the federal pleadings and briefs. He was partic-

ularly concerned with the alleged lack of adversity in the

case and in an on the record exchange, engaged Attorney Hor-

ton in a discussion as to the adversity between the Plain-

tiffs and the Defendants. At the end of the exchange, Attor-

ney Horton agreed that there was no disagreement between the

Plaintiffs and the Defendants. At this point, Judge Hammer

knew he had a problem on two fronts. First, in view of the

lack of adversity, the probative value of the record was at

best highly speculative. In addition, there was a potential

due process taint which would preclude imposition of any re-

medy impacting non-parties to the litigation.'And this was

against the background of a collateral challenge in federal

court that was a virtual certainty.

Judge Hammer's immediate reaction was to bring in an

adverse party, the general assembly. He offered to join

them as party defendants that very day. The Friendly Adver-

saries argued that this was impossible. At that point, Judge

Hammer called a halt to the proceedings to reconsider for

the third time his jurisdiction.

Final, final arguments were held on November 30, 1994

10

and the Judge issue his opinion on April 12, 1995. That

opinion can only be understood against the background of the

collateral challenge in federal court and the final argu-

ment on December 16, 1993. Attached as Exhibit 9 is the In-

tervenors Motion for Order, Dkt. No. 224.00, and the Memor-

andum in Support is attached as Exhibit 10. At pages 9 - 15,

the Intervenors outline the principal areas where they im-

pacted the decision. There is no question in the minds of

the Intervenors that they were the prevailing parties.

II. Legal Grounds.

The legal points and authorities supporting the posi-

tion of the Intervenors are contained in Exhibits 4, 6 and

10 as well as in the briefs attached to the Motion for Order

pending before Judge Hammer. The real issue in this motion

is not legal but practical. Before going forward, should

this Court not wait for all the parties who contributed to

the decision of the court below before it so that it can

have all the arguments presented to Judge Hammer before it?

At this point, by virtue of the withdrawal of the Motion to

Intervene, the Intervenors are not parties. Under federal

law, which dictates the procedure Judge Hammer must apply.

the § 1988 Motion is proper and timely. The Intervenors be-

lieve Judge Hammer will grant their Motion, however, whether

he grants or denies it, it is an appealable ruling. Whether

the Intervenors come up as Appellees or Appellants, their

arguments will be presented to this Court as they were to

p Judge Hammer.

11

® Respectfully Submitted,

J Se he, i rd 7

~ ZF ~

Vi F 3 7 alle - 2 ~

Robert A. Heghmann

Juris No. 100091

521 W. Avon Road

Avon, CT 06001

(203) 651 - 4611

(203) 651 - 9635 FAX

(Clemco Corporation)

CERTIFICATION

I hereby certify that copies of this Motion and all

Exhibits attached hereto were served on all counsel of

record in accordance with the Practice Book on May 10, 1995.

Fd

A Pe } —

/ re — f ~

AZ - ”

< ai & 7 . .

CV89-0360977S

MILO SHEFF, et al. : SUPERIOR COURT

Plaintiffs :

Vv. : JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

: HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al. : AT HARTFORD

Defendants April 19, 1993

|

| PLAINTIFFS’ POST-TRIAL BRIEF

1

communities, representing over 50% of the total school enrollment in

the Hartford region (see Pls’ Exs. 150, 151, 112). During the same

time period, defendants financed a major expansion of school capacity

within the increasingly racially isolated Hartford school district.

(Id.) Defendants had extensive approval authority over each of these

schools (Gordon I p. 133), and reimbursed local districts at rates

ranging from 50% to 80% of total construction cost (Gordon pp. 135-

36). (See also Pls’ Exs. 9, 144, 145.) To this day, defendants

continue to fund the construction or expansion of segregated single

district schools (see Pls’ Exs. 142, 143, 160).%

The 1980s

The appointment of Gerald Tirozzi as state Commissioner of

Education in April of 1983 marked a turning point in the history of

equal educational opportunity in Connecticut. As former

superintendent of one of Connecticut’s most segregated school

districts, Tirozzi was aware of the harmful effects of racial and

economic isolation, and placed the issue at the center of the state’s

educational agenda. However, in spite of Commissioner Tirozzi’s

efforts and despite the state’s increasing recognition and

documentation of the inequities and isolation affecting its inner

city school children, no progress had been made in addressing the

problem by the end of Commissioner Tirozzi’s term.

® As plaintiffs have earlier pointed out, the state is also

responsible for creating and maintaining coterminous town and school

district lines pursuant to C.G.S. §10-240, (see Collier) and

requiring that parents send children to schools within their town,

C.G.S. §10-184.

- 74 -

In 1984, and again in 1986, the State Board of Education

set out an official state definition of equal educational opportunity

(Pls’ Exs. 39 and 43), focussing on eliminating disparities in

educational resources and outcomes among districts and among racial

and ethnic groups. Significantly, the state Board at this time

emphasized the important relationship between racial and economic

integration and equal educational opportunity, and reiterated its

position that access to equal educational opportunity "is an issue

that goes beyond local school district boundaries to the region and

in some instances, the state as a whole" (Pls’ Ex. 39 at 84)

(emphasis added).

In a letter transmitting the 1986 policy to each

superintendent in the state, Commissioner Tirozzi noted that

"[n]Jothing in our business is more important than...equality of

educational opportunity." "Every major study of educational

opportunities in our state," wrote Tirozzi, "has identified two

Connecticuts: one is remarkably advantaged, the other unfortunately

disadvantaged. Experience shows that it is a constant pattle just to

keep that disparity from growing; and yet our goal remains the

reduction of that disparity" (Pls’ Ex. 44).

During this same time, the committee charged with making

recommendations to the Commissioner on the racial imbalance law was

moving toward the conclusion that increasingly levels of racial and

economic isolation were educationally harmful to students, and that

interdistrict desegregation was the only way to bring about construc-

tive reform. In their 1985 "Interim Report" (Pls’ Ex. 41), the

"Advisory Committee to Study the State’s Racial Imbalance Law and

Regulations" urged the State Board of Education "to declare that

racially segregated schools are a barrier to quality and equality of

opportunity in education." The Committee called for increased

payments for interdistrict Plans, magnet schools, and educational

parks, and endorsed the Cambridge controlled choice approach, a

combination of voluntary and mandatory student assignment. In the

committee’s final report published the following year, the Department

of Education documented increasing levels of racial concentration,

and acknowledged the "strong inverse relationship between racial

imbalance and quality education in Connecticut’s public schools"

(Pls’ Ex. 42 at 1). The report concluded that racial imbalance was

"coincident with poverty, limited resources, low academic

achievement, and a high incidence of students with special needs"

(Pls’ Ex. 42, at 1).

In December 1986, another Department of Education

committee, the "Committee on Racial Equity," began its work, which

would eventually culminate in the first Tirozzi report in January

1988 (Pls’ Ex. 50). The Committee’s working documents Clearly show

that the staff had full knowledge of available desegregation

techniques (Gordon II p. 63), and quickly realized the need for

mandatory interdistrict desegregation. As developed by the

Committee, the concept of metropolitan "collective responsibility"

(Pls’ Ex. 46) which would later reappear in the January 1988 final

report had a strong coercive character: "should [local districts] be

unable to affect a plan and/or successfully implement it in the time

- 76 =

established in the plan, the State Department of Education (SDE

shall mandate a plan of action" (Pls’ Ex. 47 at 2) (emphasis added).

The controversial January 1988 Report o acia thnic

Equity and Desegregqgation in Connecticut’s Public Schools ("Tirozzi

I") (Pls’ Ex. 50) represents a clear acknowledgment of the pressing

need for mandatory interdistrict school integration, and an admission

that meaningful desegregation may not be achieved solely through

voluntary cooperation of local districts (Gordon II p. 11). The

report urged prompt action, noting that "[f]or Connecticut, the

period of grace is running out" (Pls’ Ex. 50 at 4):

First, it is recommended that the school districts

affected, following state guidelines, would be required to

prepare a corrective action plan to eliminate racial

imbalance. Each school district in a region, including

those deemed to be contiguous and adjacent, shall

participate in the plan development and implementation.

Boundary lines separating school districts, often perceived

as barriers that prohibit or discourage the reduction of

racial isolation, should not be allowed to defeat the

school integration efforts.

Second, it is recommended that solutions contained in the

desegregation plan should initially be nonprescriptive and

voluntary, such that the affected school districts might

themselves find remedies appropriate to their own unique

situations. Nevertheless, to ensure that solutions are

found and progress is made, the State Board of Education

should be empowered to impose a mandatory desegregation

plan at such time as it might judge the voluntary approach,

in whole or in part, to be ineffectual.

(Pls’ Ex. 50 at 11) (emphasis added).

After the report was released, Commissioner Tirozzi toured

the state to "get the pulse of the citizens" (Pls’ Ex. 494 at 113).

Hearing community protest, the state took no action on the Tirozzi

report’s central recommendations, and to this day, none of the

- 77

interdistrict recommendations of the report has been implemented

(Gordon II p. 72) (Pls’ Ex. 494 at 101, 107, 113, 119-20).%

Instead, the Department issued a second report in April of

1989, Quality and Integrated Education: Options for Connecticut

("Tirozzi II") (Pls’ Ex. 60), which, as William Gordon observed,

"retreats completely from Tirozzi I. It goes purely to voluntary

strategies" (Gordon II p. 73). Gone from the Tirozzi II report is

the strong state role envisioned by Tirozzi I, and the concept of

"collective responsibility" (Gordon II p. 73). According to Dr.

Gordon, the Tirozzi II report was neither a meaningful nor an

effective set of recommendations to address the problem of racial

isolation in Hartford (Gordon II p. 74). However, during this same

period, the Department of Education was continuing to study and

document the harms of racial and economic isolation and the glaring

inequities between Connecticut’s urban and suburban schools. In a

series of detailed research reports, defendants readily admitted (as

they had in the first and second Tirozzi reports) a number of the

points raised by plaintiffs in this case (see Pls’ Exs. 56, 58, 59,

69, 70). Once again, defendants failed to take appropriate action.

The Sheff v. O’Neill lawsuit was filed shortly after the release of

the Tirozzi II Report.

5% The defendants’ capitulation to political opposition appears

even more unfortunate in light of the support that Commissioner

Tirozzi received from educators and religious leaders, with

organizations such as the Connecticut Education Association (Pls’ Ex.

65), the Christian Conference of Connecticut (Pls’ Ex. 64), and the

Connecticut Federation of School Administrators (Pls’ Ex. 57) calling

for action on school integration. See also Pls’ Exs. 81, 82.

CV89-0360977S

MILO SHEFF, et al. : SUPERIOR COURT

Plaintiffs :

v. : JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

3 HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

WILLIAM A. O/NEILL, et al. 3 AT HARTFORD

Defendants 3 April 19, 1993

| PLAINTIFFS’ POST-TRIAL BRIEF

INJUNCTIVE AND DECLARATORY RELIEF IS APPROPRIATE TO REDRESS

CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATIONS.

A. Plaintiffs Meet the Standard for Issuance of Declaratory

Relief.

The purpose of a declaratory judgment action is "to secure

an adjudication of rights where there is a substantial question in

dispute or a substantial uncertainty of legal relations between the

parties." Connecticut Association of Health Care Facilities wv.

Norrell, 199 Conn. 609, 613 (1986).

The declaratory judgment procedure is "peculiarly well

adopted to the judicial determination of controversies concerning

constitutional rights." Horton I, 172 Conn. at 626. The relevant

practice book provisions and statutes have been consistently

construed "in a liberal spirit, in the belief that they serve a sound

social purpose." Id.

The harms plaintiffs face clearly necessitate the

imposition of a declaratory judgment. Serious constitutional

deprivations have been inflicted upon the children for too long. The

evidence compels a remedy declaring the present educational system to

be in violation of plaintiffs’ rights under Connecticut statutes and

the Connecticut Constitution. It is only when the controversy on

liability has been resolved that the parties can truly face the most

challenging disputes in this case -- the appropriate remedies to

address the legal wrongs.

B. Plaintiffs Meet the Standard For Issuance of an Injunction.

The requirements for the granting of a permanent injunction

in this state are well-settled. The Plaintiffs must show irreparable

harm and the lack of an adequate remedy at law. Stocker wv.

Waterbury, 154 Conn. 446, 449 (1967). In exercising its discretion

whether to grant injunctive relief, a court must balance the

competing interests of the parties, and the relief granted must be

"/compatible with the equities of the case.’" Dukes v. Durante, 192

Conn. 207, 225 (1984) (citations omitted).

Because the harm that would flow from the absence of any

injunctive relief is immense, this Court must grant plaintiffs more

than merely a declaratory judgment. In Hartford alone, there are

almost 26,000 children in a racially and economically isolated school

system which is failing to provide an adequate education or

opportunities equal to that of other children in this state. As

plaintiffs’ witnesses at trial indicated, "something very dulling

happens to them when they stay in a negative environment, where lack

of expectation gets lower and lower every year. They just don’t

grow, they don’t blossom" (Cloud p. 106). "They may not get a chance

if we don’t provide the experiences" (Carter Pp. 30). As the detailed

historical treatment of this issue has so repeatedly demonstrated,

while the state has continued to talk, it has consistently failed to

back its words with any significant action. But for the children who

are failing, talk has come all too cheap. Task force report after

task force report has failed to yield any concrete improvements in

their educational experiences. Legislative proposal after

- 108 =-

legislative proposal has failed to give them the education they

deserve. They are "the poorest of the poor. ..achieving the lowest of

the low...[having] the least of the resources...in the highest of the

high racially impacted districts" (Natriello II Pp. 67-68). Each

child experiences the education system only once. Each month that we

delay and each year that we put off action impairs the academic

ability of these children and continues this "bifurcation of the

haves and have nots" (Foster p. 152; see also Haig p. 65). As Badi

Foster testified, "there are individuals we’re losing right now on

the streets of Connecticut, losing simply because they’re losing

hope" (Foster p. 55). This Court is a means of last resort to

translate words into action (Carter p. 45; Noel p. 46). "The

outcomes that Hartford has been producing year after year after year

may be the best it can do given the current resources and

circumstances, but if it is it really says something pretty terrible

about ourselves as a society and government in the State of

Connecticut" (Slavin p. 40). Injunctive relief is essential if the

children of Hartford are to be rescued from their current fate.

Cc. Components of a Remedial Plan

The state cannot fairly claim that it has taken significant

action to address the problem of racial and economic isolation in the

Hartford schools and the educational disparities facing Hartford

students. In spite of almost 30 years of recommendations and

reports, almost nothing has been done. Project Concern was never

expanded to a level that would lead to meaningful desegregation, and

- 109 ~-

the remaining interdistrict education programs in the Hartford area

serve only 62 Hartford students, and should not be taken seriously by

this court. (See supra §III.)

As Dr. William Gordon pointed out, Connecticut has been a

leader in documenting the problem of segregation, but has done little

to constructively address the problem. Unfortunately, the

legislative and executive branches of government have not had the

courage to correct what has long been acknowledged to be a situation

which is "utterly unnecessary" (Slavin Pv 34). Without court

intervention, there can be no progress (Carter Pp. 45; Gordon pp. 24,

64, 93).

For more than three decades in the post-Brown era,

communities have formulated successful school desegregation plans by

engaging in a court-ordered and expert-assisted planning process.”

Those school desegregation plans which have been developed under the

close supervision and guidance of the court have been the most

successful (Gordon III p. 24). Initially the court sets the end

goals, defines the standards, issues timetables and then orders the

Dr. Gordon testified that he knew of no metropolitan plans

implemented without a court order (Gordon I Ps 118). Another

educational expert for the plaintiffs testified that he knew of only

one city that has voluntarily sought to desegregate its schools

without a court order (Orfield p. 31). A few successful plans

identified by Dr. Gordon in his testimony include: Eastern Allegheny

County, Pennsylvania (see, e.qg., oots wv. Commonwealt

Pennsylvania, 703 F.2d 722, 724 n.1 (3rd Cir. 1983), for various

cites); Benton Harbor, Michigan (see, e.qg., Berry v. School District

of City of Benton Harbor, 467 F.Supp. 721 (W.D. Mich 1978);

Louisville/Jefferson County, Kentucky (see, e.g., Newburg Area

unci CoV, ard ducatj of Jefferson C ty, 583 F.2d 827

(6th Cir. 1978). (Gordon III pp. 26-29). See also Orfield I pp. 46-

47.

- 110 =

groups in the planning process to design a plan (Orfield I pp. 44-

46).

Plaintiffs’ other expert witness on school desegregation

planning, Professor Charles Willie of Harvard University, testified

that successful plans have resulted from such a planning process

(Willie p. 45). This process consists of two tiers: an oversight

group and a working planning group (Gordon II p. 84; Gordon III p.

24). These groups resemble the relationship between a homeowner

and an architect. The oversight group consists of representatives of

the plaintiffs, defendants (Board of Education, Commissioner, and

Governor), and attorney representatives. Their purpose is to provide

guidance and to evaluate plans submitted by the planning group. The

planning group, which includes educational experts, desegregation

experts, demographers, school board and superintendent

representatives, teachers, parents and selected community

representatives (Gordon p. 83),” will actually draft a plan for

submission to the oversight group for approval and eventual

submission to the court.

Once the groups are established, it is important to charge

them with specific directions. As outlined below, any plan for the

Hartford region must include the following seven components:

7% The court usually appoints an expert or monitor with the

authority to summon the groups in the planning process until

completion (Willie p. 45; Gordon III p. 24).

7” Professor Orfield also emphasized the importance of bringing

together the remedy experts and the educational experts (Orfield I

PP. 31, 97).

-31l -

The Remedial Plan Must Be Interdistrict In Its Design.

The Plan Must Include Mandatory and Voluntary

Provisions.

Reduction of Racial Isolation and Poverty

Concentration Must Be a Major Goal.

Bilingual Education Programs Must be Preserved.

Educational Enhancements Must Supplement Any

Desegregation Goals.

Housing and Other Components Must be Addressed in the

Plan.

Timetables Must be Strictly Enforced.

Monitoring and Reporting Requirements Must be

Included.

These components are discussed more fully below.

1. The Remedial Plan Must Be Interdistrict In Its Design.

The planning process to achieve racial balance and

quality education in the greater Hartford region actually began in

1965 with the Harvard report (Gordon II pp. 11-12 and Pls’ Ex. 1).

This report recommended a metropolitan plan of education for the

school districts in the region within a fifteen mile radius of

Hartford.

With the isolation of African American, Puerto Rican,

other Latino and poor students in Hartford, and the isolation of

white students in an overwhelming number of suburban districts, an

interdistrict approach remains today the only feasible method to

ameliorate the disparate conditions in Hartford (Willie pp. 41, 42,

49; Gordon II p. 14). Plaintiffs’ witnesses were quite unanimous in

their conclusions that the plan must be "metropolitan wide" (Orfield

- 112 -

p. 32), encompassing the entire urban community housing and

economic area. Stability as well as academic progress have been

achieved with metropolitan plans around the country (Orfield I pp.

46-48; Orfield II pp. 142-43).

2. The Plan Must Include Mandatory and Voluntary

Provisions.

Certain mandatory components are critical ingredients

of the planning process itself as well as of the actual plan (Willie

p. 44). Voluntary participation by educational authorities in

planning for desegregation will not work (Gordon II P. 125). local

school districts cannot be allowed to "decide" whether to participate

in the desegregation plan. Even more important, any noncompliance by

school districts with the goals of the plan should trigger a sanction

process. The planning process needs the bite of enforcement to

insure full participation by every district. All school districts

must participate in the planning process, and they must also

implement the final educational equity plan (Gordon II pp. 125-126).

To achieve the goals of racial and educational equity,

the plan may include some voluntary school selection options by

parents” as well as "controlled choice" (Willie pp. 41, 42) and

Even one of the key defendants, John Mannix, the former

chairman of the State Board of Education (until January, 1993)

supported the plaintiffs’ position, favoring a metropolitan remedial

planning approach ordered by the court to counter the detrimental

effects of racial and economic isolation (Pls’ Ex. 495 at 18, 26, 30

and 37) (Deposition of John Mannix).

5 ..In this respect, it is important to have parent involvement

as part of the plan (Orfield I pp. 38-58).

-3113 -

mandatory "back-up" measures (Orfield I PP. 33-34). No standard

method currently used in educational administration, such as

mandatory student assignment, should be excluded from consideration

in the planning process.

3. Reduction of Racial Isolation and Poverty

Concentration Must Be a Major Goal.

An educational equity plan should be guided by the

principles well established in Green v. New Kent County,® to focus

on student assignment, faculty and staff assignments, curriculum,

transportation, extracurricular activities and facilities. Commonly

Known as the six Green factors, they guide the court in the planning

process to accomplish the ultimate goal of the elimination of racial

identifiability in every school (Gordon II Pp. 149). In the end,

schools full of children, who are eager to learn, should not be

"identified as any racial [group] =-- shouldn’t be the poor school,

the black school, the Hispanic school, the white school" (Gordon II

p. 150)% -- "but just Schools." Green, at 441.

In the present case, which addresses the dual harms of

racial and poverty concentration, the Green factors can be adapted to

8 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

® Adams v. Weinberger, 391 F.Supp. 269 (D.D.cC. 1975); Diaz v.

ifie hoo istrict, 633 F.Supp. 808, 814 (N.D. cal.

1985); ited States wv. onkers Board Scho jrectors o

Milwaukee, 471 F.Supp. 800, 807 (E.D. Wis. 1979) aff’d 616 F.2d 305 (7th Cir. 1980); Arthur v. Nyquist, 566 F.Supp. 511, 514 (W.D.N.Y.

1983); Vaughans v ard of Education ince Ge d unty, 574

F.Supp. 1280, 1375 (D. Md. 1983) aff’d in part, rev’d in part on

other grounds, 758 F.2d 983 (4th Cir. 1985); United States v.

Ss ount le) i jct, 738 F.Supp. 1513 (D.S.C. 1990)

modified on other unds, 960 F.2d 1227 (4th Cir. 1992).

-114 -

& eliminate both racial and poverty isolation in the region’s schools.

Only a racial goal set by this court for each school offers the most

| effective remedy of removing all stigmatization.® Schools should

mirror society and provide access to mainstream America (Orfield I p.

30). In addition, to counteract the concentration of poor students

in individual schools, the Plan must contain specific goals to

address the economic isolation (Gordon II Pp. 84; Orfield I p. 35;

Kennedy p. 42). Unless deconcentration of poverty is an integral

, part of any court-ordered plan, the dismal Hartford outcomes described at trial will continue (Slavin p. 29).%

The same goals equally apply to the integration of

faculty and staff (Orfield I p. 44). Not only is it important to have a diversity in staff, but it is important to train staff for |

& i diversity (Orfield I pp. 31-32, 37).

] The curricula also must be evaluated and altered as

i necessary to adequately address the diversity -- racially, ethnically

I and socio-economically =- of the students in the Hartford |

metropolitan region. Special education, gifted, advanced placement,

academic and vocational offerings must be designed so that no racial |!

2 por example, the court may order the schools in Hartford and

the surrounding districts to reflect the student racial ratio in the

region of approximately 2/3 White and 1/3 children of color. Any

magnet schools could have increased racial balance such as 50:50

white and nonwhite African American, Puerto Rican and other Latino

students (Orfield I p. 55).

8 See generally, Haig pp. 66, 67 on the necessity to eliminate |

the high concentration of poverty. See also Pls’ Ex. 493 at 51

(Deposition of Vincent Ferrandino).

¢ ng

or economic group is disproportionately represented in any single

area.

Effective and equitable transportation must be a part

of a desegregation plan (Orfield I p. 38) to get to and from school

as well as to participate in all school related extracurricular

activities (Orfield I P. 38).

4, Bilingual Education Programs Must be Preserved.

Hartford’s bilingual education program currently

serves approximately 6,000 students per year (Marichal p. 11). The

vast majority of these students are enrolled in a program for native

Spanish speakers (Marichal Pp. 12). In order to successfully

desegregate Hartford and its suburbs the programmatic needs of these

limited English proficient (LEP) students must be addressed (Orfield

I Pp. 49). Addressing these needs appropriately entails the

establishment of quality bilingual education programs in suburban

schools. Since state law requires that bilingual education be

provided only when there are 20 or more students with the same native

language in a school building, consideration must be given to the

numbers of LEP children who will attend a particular school. There

must be careful planning in order to insure both the continued

provision of bilingual education and the guarantee of ethnic

diversity.

Given the balances that must be achieved, the

requirements of state law, and the pedagogy that has developed over

the implementation of quality bilingual education programs,

- 116 ~-

|

i

|

|

1

|

i

|

|

participation of experts in this area is crucial to the planning

process.

5. Educational Enhancements Must Supplement Any

Desegregation Goals.

To enhance the quality of education in Hartford for

all students, the plan must include educational enhancements?

(Gordon II p. 113; Orfield I pp. 51-53; Haig p. 66).%® These

programs are designed around the assumption that all children can

learn and that it is the schools’ job to insure that every child will

be successful (Slavin p. 14).% A one-to-one early intervention

tutoring program such as "Success for All" could be easily and

quickly replicated in Hartford (Slavin pp. 37-38). Drop-out

prevention programs, and Upward Bound programs (Orfield I p. 52) are

8 Educational enhancements have been defined as programs which

set a minimum floor for achievement of every child and which improve

the overall achievement of all children (Slavin pp. 13-14).

Enhancement includes upgrading the physical facilities and curricula

to provide an extraordinary education in the inner city schools

(Willie pp. 48, 49).

8 The witnesses cautioned, however, that educational

enhancements alone cannot achieve positive results. They must be in

combination with the other components (Orfield p. 35), and cannot be

substitutes for the need to reduce racial and economic isolation

(Slavin pp. 37-38).

8 There are several successful enhancement models. Dr. Slavin

described in detail his model, "Success for All" which has been

adopted in fifty-six schools in twenty-six school districts (Slavin

PP. 14-26, 52-53), and is well-respected by educational experts

(Orfield I p. 36). Other models with positive benefits include the

"Follow Through" model (Orfield I p. 36), which Hartford had to

eliminate in budget cutting measures (Hernandez p. 45), and the

Reading Recovery and Comer Programs (Slavin pp. 32-33; Pls’ Ex. 473).

--3117 =

examples of the types of programs which could be used in upper

grades.

Enhancements to educational programs should take into

account the cultural diversity of the Hartford area. Schools must

reflect this diversity not only in students, faculty and staff, but

also in curriculum. Green, supra. Dr. Morales summarized how the

lack of a multi-cultural education for all students can cause

continued difficulties.

I think it’s essential that the teachers and the

administrators be knowledgeable about issues relating to

Puerto Rican culture and heritage and implications of the

combination of poverty and ethnicity into the classroom.

I think is also means teaching more about =-- all groups of

people about the Puerto Rican experience.

(Morales pp. 51-52).

6. Housing and Other Components Must be Addressed in the

Plan.

As Dr. Orfield indicated, it is also important to

include housing provisions in the educational plan® (Orfield I PP.

31, 40-43). School construction and housing construction -- an

obvious link -- require comprehensive planning to prevent the

perpetuation of segregation in neighborhoods, and regional housing

mobility programs should be carefully considered.2

5 Housing components can be an integral part of a school

desegregation order. See e.g. Denver; Palm Beach County; Louisville;

St. Louis (Orfield I pp. 40-41).

8 Regional housing mobility programs provide counselling and

moving assistance to tenants who hold state and federal rental

certificates (Orfield I p. 41).

- 118 -

In addition, components relating to the health needs

of students may be necessary (Orfield I P. 54). This is particularly

true in this case given the health effects of poverty confronting the

students and impeding their academic learning. Id. See also Section

II(B), supra.

7. Timetables Must be Strictly Enforced.

For the planning process to succeed, the court must

set firm timetables with sufficient time to develop a plan, but not

SO much time to further defer the dream of an equal educational

opportunity for students in Hartford with the least and who deserve

the most (Orfield I p. 44; Gordon I P. 85). Unless rapid deadlines

are set, racial polarization can also begin to occur in the community

(Orfield I p. 44), and implementation will become more difficult.

The plaintiffs cannot overly impress upon this Court

the urgency to act to prevent further lost generations of youngsters.

Dr. Orfield indicated a plan could be developed in a minimum of two

to three months (Orfield I p. 61). Dr. Willie and Dr. Gordon

indicated no more than six months was necessary to furnish an

equitable plan for education (Willie P. 47; Gordon II p. 157).

Within this time frame, the oversight and planning groups must be

ordered to present the plan to the Court for approval.®

® Dr. orfield also suggested that interim measures could be ordered pending development of a plan, including expansion of Project Concern, an injunction against new school construction that is not racially integrated, training of teachers and staff, faculty recruitment, and development of dual immersion programs (Orfield I PP. 61-64). Dr. Slavin indicated a remedial program could quickly be implemented (Slavin p. 38).

-. 3119 =

8. Monitoring and Reporting Requirements Must be

Included.

In order to insure that the plan is successful, it is

important to have a group of experts, independent of the school

authorities, assess the plan and report directly to the Court and the

parties? (orfield I pp. 50-51; Pls’ Ex. 455). In particular, the

educational components of a plan must be carefully scrutinized to

insure that academic progress is actually being achieved (Orfield I

P. 50). In addition, drop-out data and college attendance rates

should be monitored, as well as the numbers participating in pre-

collegiate training (Orfield I p. 53). Districts should be required

to monitor and report on such items as discipline, course

assignments, guidance programs, special education/gifted programs as

well as the Green factors. School districts must get court approval

for school closings, attendance zone changes, new construction, new

programs, and other modifications which might affect the plan’s

goals.

Judges often appoint a bi-racial or bi-cultural committee to

oversee problems in the implementation of the plan (Willie pp. 46,

47).

- 120 =

U. 8. DISTRICT COURT

DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT

John Doe and Mary Doe, individually

and on behalf of their children William :

and Jane Doe, as well as all other parents Civil Action No.

and students similarly situated, and

Robert Heghmann and Beatrice Heghmann, FY S09%y 2s

individually and on behalf of their daughter 3 93 Lh U U oh 3 3

Victoria Heghmann, as well as all other 3

parents and students similarly situated; Plaintiff's Demand _

a Trial by Jury | :

Ve.

A .

«a.

Hon. Lowell P. Weicker, Governor, State of

Connecticut, State Board of Education, and

Vincent L. Ferrandino, member of the State

Board of Education and Commissioner.

COMPLAINT

1. The Plaintiffs, John Doe and Mary Doe, are fictitious

parties representative of citizens of the United States and the

State of Connecticut who are domiciled and reside in the twenty

(20) towns surrounding the city of Hartford. Their children,

William and Jane Doe attend public elementary and secondary schools

in the towns where their parents reside. These towns are cited in

a law suit pending in the Superior Court of the State of

Connecticut, Judicial District of Hartford-New Britain styled Milo

sheff, et al. v. William A. O'Neill, et. al., Civ. No. 89-0360977S

(Hereinafter Sheff). These fictitious Plaintiffs seek to preserve

the right of real parties to be determined at a later date who are

affected by the orders, remedies, policies or programs enacted or

adopted as a result of the Sheff law suit.

- 2 =

2. The Plaintiffs, Robert A. and Beatrice M. Heghmann are

citizens of the United States and the State of Connecticut and are

domiciled and reside in the town of Avon, Connecticut. Victoria

Heghmann, their natural daughter, attends Pine Grove Elementary

School, an elementary school maintained by the town of Avon for the

children of its residents. Plaintiffs Robert and Beatrice Heghmann

bring this action on their own behalf, on behalf of their daughter

Victoria and on behalf of all other parents and children similarly

situated in the 21 towns surrounding Hartford cited in the Sheff

law suit.

3. Defendant Lowell P. Weicker is the Governor of the State of

Connecticut. Pursuant to C.G.S. Secs. 10-1 and 10-2, with the

advice and consent of the General Assembly, he is responsible for

appointing the members of the State Board of Education.

4. Defendant State Board of Education of the State of

Connecticut is charged with the overall supervision of educational

interests of the State, including elementary and secondary

education, pursuant to C.G.S. Sec. 10-4.

5. Defendant Vincent L. Ferrandino is the Commissioner of

Education of the State of Connecticut and a member of the State

Board of Eduction. Pursuant to C.G.S. Secs. 10-2 and 10-3a, he is

responsible for carrying out the mandate of the Board, and is also

director of the Department of Education.

6. The Defendants herein are defendants in the Sheff law suit

and would ke the state officers directed to adopt or implement any

policy, program, order or remedy required by the court in Sheff.

-i3

7. This action arises under the United States Constitution,

more particularly the Freedom of Association, Parental Rights, the

Right of Privacy, the Right to Due Process and the Equal Protection

of the Law contained in the Constitution and more specifically, the

1st, 5th, 9th and 14th Amendments thereto, and under federal law,

particularly 42 U.S.C Sec. 1983 (1979) and 28 U.S.C. Sec. 1343 (3)

(1979). Venue is proper in this district by reason of 28

U.8.C. 1391 (Db) (1990)

8. This action is brought to redress violations and threatened

violations of the Plaintiffs Constitutional rights guaranteed under

the United States Constitution and made applicable to the states

under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. The Plaintiffs seek

both injunctive and declaratory relief from the enforcement

of any order, remedy, policy or program entered or required by the

court and entered by either judgment or settlement in Sheff,

either directly by the Court, the Board of Education or by

legislative enactment, to the extent that any order, remedy,

policy or program abridges the Constitutional rights enjoyed

by the Plaintiffs as parents and students and protected by statutes

and provisions cited above, as well as their rights of Due Process

and Equal Protection under the Law.

9. This action is filed in accordance with the procedural

dictates as set out in the decisions of the U. S. Supreme Court in

the cases of England v. Medical Examiners, 375 U.S. 411 (1964),

Government Employees v. Windsor, 353 U.S. 364 (1956) and Railroad

Commission of Texas v. Pullman, 312 U.S. 496 (1941).

Bw

10. The Plaintiffs herein are not parties to the state court

action nor are they in privy with any party currently before that

court. The Sheff case, as plead, does not implicate and does not

seek any remedies which would implicate or abridge any of the

Plaintiffs rights or privileges guaranteed by the U.S.

Constitution. According to media reports, however, the state court

plaintiffs, who are seeking the creation and enforcement of

a state right in addition to and beyond those rights contained in

the U.S. Constitution, are introducing evidence and are laying a

foundation to request remedies under said state created right

which, if granted by the court or enacted by the legislature, would

implicate and abridge the U.S. Constitutional rights of the

Plaintiffs herein.

11. In keeping with the Rules of this Court and the advice of

the Supreme Court in the cases cited in par. 9, supra., the

Plaintiffs are filing this action as the first step required under

England to secure federal court adjudication of their

Constitutional claims. With the filing of this action, Plaintiffs

respectfully request this Court to stay any further proceedings

pending conclusion of the Sheff case. The Plaintiffs herein will

seek to appear in the Sheff case to advise the state court of their

Constitutional concerns pursuant to the Supreme Court's decision in

Windsor but will not submit to state court adjudication of those

claims and will reserve adjudication of those claims for this

Court. See Letter Dated February 1, 1993 attached as Exhibit A.

12. The purpose of this action is to secure federal court

iB

adjudication of Plaintiffs' U.S. Constitutional claims while

permitting the Plaintiffs to appear in the state court proceeding

to appraise the state court judge of their concerns in the hope

that the state court will reach a conclusion on the state law

issues without implicating or abridging Plaintiffs Constitutional

rights while still preserving the Plaintiffs rights to return to

this Court if necessary. If the state court in Sheff reaches a

decision which does not implicate or abridge the U.S.

Constitutional rights of the Plaintiffs, this case will be

withdrawn. If the state court issues orders or remedies

inconsistent with the Constitutional rights of the Plaintiffs, they

will return to this Court to seek redress for that deprivation.

13. John Doe, Mary Doe, Robert Heghmann and Beatrice Heghmann

are parents whose children attend public schools in the 21 towns

cited in the Sheff complaint. The Heghmann child attends public

school in the town of Avon. Each of these towns exists within

boundaries created prior to the founding of the Republic often

dating back to the 1600's. These town lines were defined by

geographical boundaries and the pre-existing boundaries of other

towns. Sheff does not allege nor is there any evidence that these

boundaries were created or maintained to foster racial segregation.

14. The school zones in the town of Avon as well as the other

towns named in Sheff are traditional neighborhood school zones.

Each school zone is a cohesive and contiguous geographical area

within which the children are assigned to a school based solely on

their residence as a matter of right with no reference to race or

- Bo

color. The schools are generally located in the center of the zones

with each zone as compact and reasonable as possible. The schools

generally follow a feeder system. Children entering primary school

are assigned to the school nearest their residence. Primary schools

then feed their graduates to a specific middle school and then on

to a specific high school. The town of Avon has two primary

schools, one middle school and one high school. Other towns have

more or less schools but in all cases, the zones were drawn along

natural geographical or physical boundaries without regard to race

or color. None of the school districts cited in Sheff has ever

maintained a segregated dual school system, and all school