Legal Defense Fund Takes New Orleans School Case to Court of Appeals

Press Release

June 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Legal Defense Fund Takes New Orleans School Case to Court of Appeals, 1962. e61b4c30-bd92-ee11-be37-6045bddb811f. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ee9ad17f-ea4d-4e83-869a-7854b3ff4c86/legal-defense-fund-takes-new-orleans-school-case-to-court-of-appeals. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

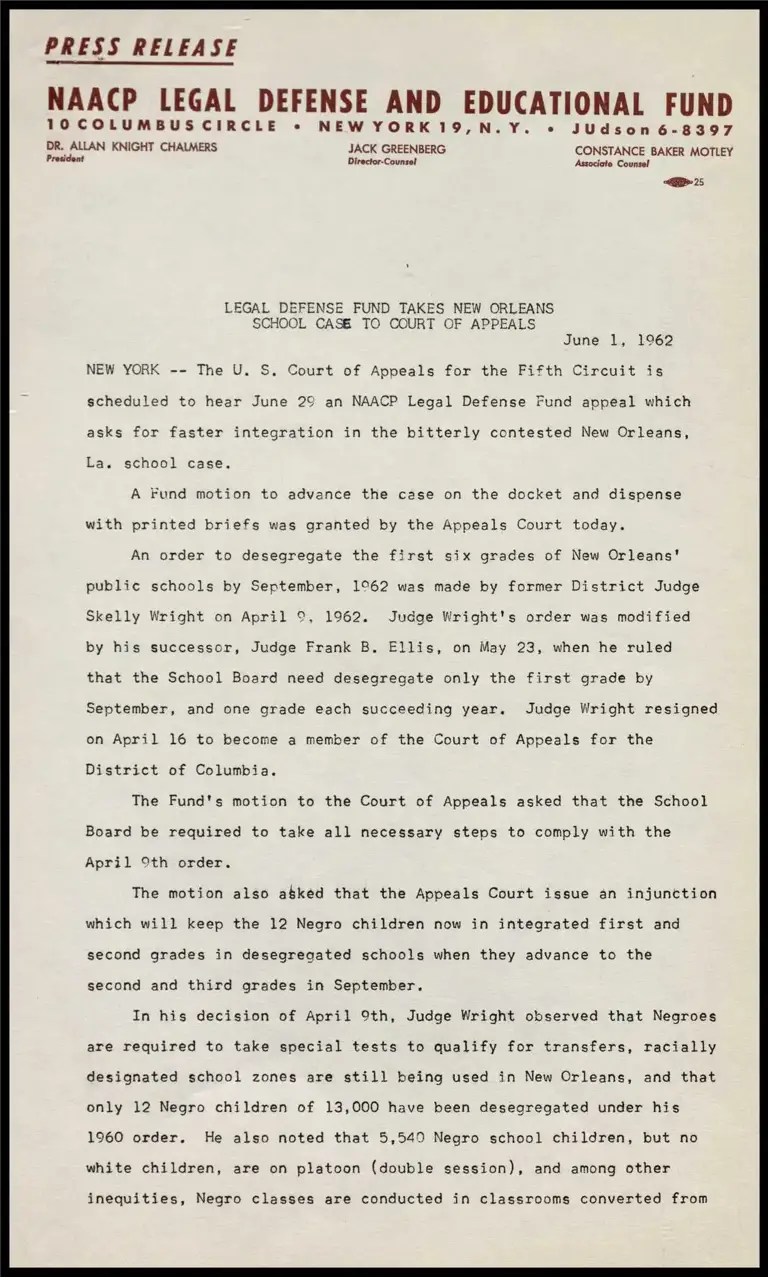

PRESS RELEASE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

TOCOLUMBUS CIRCLE + NEWYORK19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS JACK GREENBERG CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY President Director-Counsel Associate Counsel

S25

LEGAL DEFENSE FUND TAKES NEW ORLEANS

SCHOOL CAS& TO COURT OF APPEALS

June 1, 1962

NEW YORK -- The U. S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is

scheduled to hear June 29 an NAACP Legal Defense Fund appeal which

asks for faster integration in the bitterly contested New Orleans,

La. school case.

A Fund motion to advance the case on the docket and dispense

with printed briefs was granted by the Appeals Court today.

An order to desegregate the first six grades of New Orleans'

public schools by September, 1962 was made by former District Judge

Skelly Wright on April 9, 1962. Judge Wright's order was modified

by his successor, Judge Frank B. Ellis, on May 23, when he ruled

that the School Board need desegregate only the first grade by

September, and one grade each succeeding year. Judge Wright resigned

on April 16 to become a member of the Court of Appeals for the

District of Columbia.

The Fund's motion to the Court of Appeals asked that the School

Board be required to take all necessary steps to comply with the

April 9th order.

The motion also asked that the Appeals Court issue an injunction

which will keep the 12 Negro children now in integrated first and

second grades in desegregated schools when they advance to the

second and third grades in September.

In his decision of April 9th, Judge Wright observed that Negroes

are required to take special tests to qualify for transfers, racially

designated school zones are still being used in New Orleans, and that

only 12 Negro children of 13,000 have been desegregated under his

1960 order. He also noted that 5,549 Negro school children, but no

white children, are on platoon (double session), and among other

inequities, Negro classes are conducted in classrooms converted from

oe

stages, custodians’ quarters, libraries and teachers’ lounge rooms,

while similar classroom conditions do not exist in white schools.

Judge Wright also invalidated on April 9 the Louisiana Pupil

Placement Law until the Board has abolished "Negro" and "white"

schools and racially drawn school zones.

Judge Ellis, in his modifying decision of May 23, expressed

agreement with most of Judge Wright's findings. He continued the

invalidation of the Pupil Placement Law as now applied in New Orleans,

and noted that the Board had not voluntarily complied with Judge

Wright's previous desegregation orders.

He based hig withdrawal of Judge Wright's order to desegregate

the first six grades, however, on administrative problems that the

Board would encounter if it were to comply by September.

Legal Defense Fund attorneys argued in yesterday's motion that

"the Orleans Parish School Board has presented no evidence of admin-

istrative problems even tending to justify continued segregation in

grades 2 through 6...except generalized statements."

A. P. Tureaud, Ernest Morial and A. M. Trudeau of New Orleans;

Jack Greenberg, James M. Nabrit, III and Constance Baker Motley of

New York City represent the Negro children.

---0---