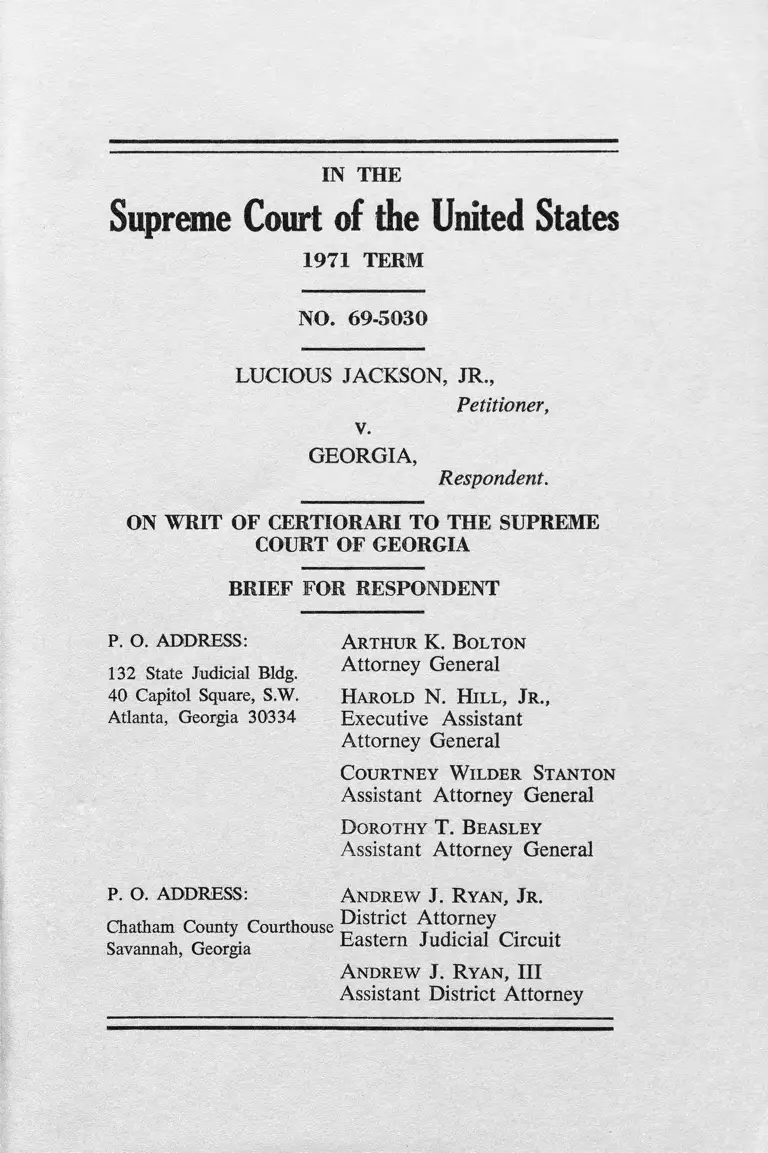

Jackson v. Georgia Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Georgia Brief for Respondent, 1971. 65cba204-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/eeb6b4f9-83c2-4ed1-bce2-b46eb17e0d5e/jackson-v-georgia-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

1971 TERM

NO. 69-5030

LUCIOUS JACKSON, JR.,

V.

Petitioner,

GEORGIA,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

P. O. ADDRESS:

132 State Judicial Bldg.

40 Capitol Square, S.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

Arthur K. Bolton

Attorney General

Harold N. Hill, Jr.,

Executive Assistant

Attorney General

Courtney Wilder Stanton

Assistant Attorney General

Dorothy T. Beasley

Assistant Attorney General

p. O. ADDRESS: Andrew J. Ryan, Jr .

Chatham County Courthouse J?istrict Attorney

Savannah, Georgia E aste rn JudlCial C ircuit

Andrew J. Ryan, III

Assistant District Attorney

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

HOW THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION

WAS PRESENTED AND DECIDED BELOW . .

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...............

ARGUMENT:

Page

. 1

19

The imposition and car

rying out of the death

penalty imposed by the

jury in this case does

not constitute a vio

lation of the cruel and

unusual punishment clause

of the Eighth Amendment

and the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amend

ment...................... 20

I. No evidence of racial

discrimination is

present, and thus it

does not constitute a

factor which might

render the death

penalty for rape in

this case a constitu

tionally prohibited

cruel and unusual

punishment................ 20

11

II. The cruel and unu

sual punishment

clause does not

forbid the imposi

tion of a penalty

of death for rape. . .

CONCLUSION .....................

APPENDICES:

APPENDIX A:

Statutory Provisions and

Rules Involved . . . . . .

APPENDIX B:

Comparative Punishments

for sexual offenses in

Georgia ....................

APPENDIX C:

Crime rate for rape—

chart . . . . . . . . . . .

. . 37

. . 56

. . la

. . lb

. . 1c

1 X 1

Abrams v. State, 223 Ga. 216

(1967) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Aikens v. California, 1971 Term,

No. 68-5027 ............. 20, 28, 30

Arkwright v. State, 223 Ga. 763

TABLE OF CASES

page

No.

(1967) .......................... 51

Betts v. Brady, 316 U.S. 455

(1942) . ...................... 18

Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483 (1954) . . . . . . . . 27

Butler v. State, 285 Ala. 387,

232 S.E.2d 631 (1970) . . . . . . 42

Craig v. State, 179 So.2d 202

(Fla. 1965) Cert. Den. 383

U.S. 959 . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Fogg v. Com., 208 Va. 541, 159

S .E .2d 616 (1968) . . . . . . . . 42

Furman v. Georgia, 1971 Term, No.

69-5003 . . . . . . . 21, 34, 37, 53

Gunter v. State, 223 Ga. 290

(1967) ............... . . . . . 51

Jackman v. Rosenbaum Company,

260 U.S. 22 (1922) 57

IV

Jackson v. State, 225 Ga. 39

(1969) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Jackson v. State, 225 Ga. 553

(1969) . 51

Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184

(1964) 38

Johnson v. State, 215 Ga. 448

(1959) 51

Kemp v. State, 226 Ga. 506 (1970) . 51

Louisiana ex rel, Francis v.

Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 (1947) . . . 38

McGautha v. California, 402 U.S.

183 (1971) 15, 36

Massey v. State, 227 Ga. 257

(1971) 5, 51

Mathis v. State, 224 Ga. 816 (1968) 51

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 F.2d 138

(8th Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ............. 22, 53

Maxwell v. Stephens, 348 F.2d 325

(8th Cir. 1 9 6 5 ) ................ 42

TABLE OF CASES-Cont.

Page

No.

V

Miller v. State, 224 Ga. 627 (1968) 4, 5, 6

Miller v. State, 226 Ga. 730 (1970) 51

Mitchell v. State, 225 Ga. 656

(1969) .......................... 51

*

Qyler v. Boles, 368 U.S. 448 (1962) 22, 30

Paige v. State, 219 Ga. 569 (1963) 51

palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319

(1937) 18

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354

(1939) .......................... 9, 11

Rjqgins v. State, 226 Ga. 381

(1970) 51

Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 889

(1963) ................... .. . . 43

Simmons v. State 226 Ga. 110

(1970) ........................ . 35

Sims v. Balkcom, 220 Ga. 7 (1964) . 4, 44

Siros v. State, 399 S.W.2d 547

(Tex. Cr. 1 9 6 6 ) ................. 42

TABLE OF CASES-Cont.

Page

No.

vi

TABLE OF CASES-Cont.

Page

No.

State v. crook, 253 La. 961, 221

So.2d 473 (1969) ................ 42

State v. Williams, 255 La. 79, 229

So.2d 706 (1969) . . . . . . . . 42

State ex rel, Barksdale v. Dees,

252 La. 434, 211 So.2d 318 (1968) 42

State v. Goes, 271 N.C. 616, 157

S.E.2d 386 (1967).............. 42

State v. Rogers, 275 N.C. 411, 168

S .E . 2d 345 (1969).............. 42

State v. Gamble, 249 S.C. 605, 155

S . E . 2d 916 (1967).............. 42

Stragder v. West Virginia, 100 u.S.

303 (1880) 7, 11

Swink v. State, 225 Ga. 717 (1969) 51

Tarrance v, Florida, 188 U.S. 519

(1903) 9, 11

*Moorer v. MacDouqall, 245 S.C. 633,

142 S.E. 46 (1965) 42

Page

No.

vii

TABLE OF CASES-Cont.

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86

(1968) 37,38,52

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346

(1970) 34

yanleeward v. State, 220 Ga. 135

(1964) . . . . . ............. 51

Watt v. State, 217 Ga. 83 (1961) 51

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S.

349 (1910) ................... 38, 42

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545

(1967) 11

Williams v. Illinois, 399 U.S. 235

(1970) . . . . . ............. 22,52

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241

(1949) . ...................... 52

Williams v. State, 226 Ga. 140,

173 S .E . 2d 182 (1970)............ 42

Willis v. Smith, 227 Ga. 589

(1970) . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

STATUTORY PROVISIONS

PAGE NO.

Const, of Ga. of 1945, Art. I,

Sec. II, par. I (Ga. code Ann.

§ 2-201)............. 32, App.A, 2a

Criminal code of Ga., §§

26—2001 to —2020 ...............49, App.B

pp.lb-2b

Ga. code Ann. § 26-1302 (Ga.

Laws 1960, p. 2 6 6 ) ...........3

Ga. code of 1933, § 27-2301 . . . 32,App.A 3a

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2506 ........ App.B, 2b-4b

Ga. code Ann. § 27-2534 (Ga. Laws

1970, pp. 949, 951, as amended Ga.

Laws 1971, pp. 902-903 . . . . 4

Ga. code Ann. § 59-106 (Ga. Laws

1968, p. 533)................. 34 , App.A, 6a-7a

Ga. Code Ann. § 59—709 (Code of

1 9 3 3 ) ........................ 35

Ga. code Ann. § 70-301 ........ 32, App.A, 8a

Ga. Laws 1967, p. 251 . . . . . . 34,App.A,4-5a

Ga. Laws 1970, p. 949, as amended

Ga. Laws 1971, p. 902 (Ga. Code

Ann. § 2 7 - 2 5 3 4 ) .............4

United States Supreme Court Rules,

Rules 19 and 40 . . . . . . . 16

viii

IX

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Barzun, Jacques "In Favor of

Capital Punishment," 31 The

American Scholar 181, Spring,

1962 41

City of Atlanta, Department of

police, 91st Annual Report,

Dec. 31, 1970 ................ 25

Crime in the United States, Uniform

Crime Report 1970, pp. 12-14 54

Massie, "Death by Degrees," 75

Esquire, pp. 179-80, April, 1971 41

New York Times, July 6, 1968,

p. 42, col. 1 .......... 52

New York Times, August 30, 1971,

p. 3 2 ........................ 53

Sophocles, Ajax . . . . . . . . 55

Page

No.

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

1971 Term

No. 69-5030

LUCIOUS JACKSON, JR.,

Petitioner,

v .

GEORGIA,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

HOW THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION

WAS PRESENTED AND DECIDED BELOW

A careful analysis of the

development of the constitutional ques

tion which this Court has agreed to re

view, will show that Petitioner has

2

departed from the Supreme Court of

Georgia ruling of which he complains.

It will also provide the proper context

for this Court's consideration.

The actual presentment of the ques

tion which is currently to be decided

occurred as follows: In the amended

motion for new trial and to set aside

the verdict, its filing on April 11,

1969 (R. 35) following the trial by

some four months, one of the grounds

was that:

"18. The Court is required

to set aside the verdict and

judgment because the penalty

of death as was imposed upon

defendant is cruel and unusual

in violation of the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments to the

Constitution of the United

States." (R. 29, 31, 32).

Petitioner asserts this as the under

lying foundation for the question now

extant (Petitioner's Brief, pp. 10-

11). The motion was subsequently heard

and a new trial denied by the trial

court on July 11, 1969 (R. 36), three

months after the amended motion had

been filed.

3

Then on appeal to the Supreme Court

of Georgia, Petitioner enumerated as

error the following, among others:

"6. The court erred in permitting

the death penalty to be imposed

upon defendant in violation of the

Eighth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States.'1 (Enum

eration of Errors, Supreme Court

of Georgia, filed August 22, 1969,

p.1, unnumbered in Record).

This, Petitioner says, is how the question

was presented below (Petitioner's Brief,

pp. 10-11).

The Supreme Court of Georgia, in

its customary fashion, provided head-

notes as part of its opinion. In the

headnote summary referring to appel

lant's challenge to punishment, the

court stated:

"4. Code Ann. § 26-1302 (Ga. L.

1960, p. 266) is not subject to

the constitutional attacks made

on it." (A . 112) .

Section 4 of the opinion reveals that

several enumerated errors were embraced

in the summary. As to the first,

Enumeration No. 5 (Enumeration of Errors,

Supreme Court of Georgia, p. 1,

4

unnumbered in Record), the court held

that the penalty statute was not subject

to the attack that constitutional vio

lation occurred by simultaneously sub

mitting the issues of guilt and punish

ment to the same jury (A. 114). 1 /

In this connection it cited Miller v.

State, 224 Ga. 627, 630 (1968), which

held that the alleged error referred

to as point "(c)" in that opinion and

concerning the constitutionality of

unitary trial, was not meritorious.

Id. at 631.

As to Enumeration No. 6, which

Petitioner asserts as providing the

question sub judice (Petitioner's

Brief, pp. 10-11), the court held

that the penalty statute was not subject

to the attack that the Constitution was

violated by "imposing the death penalty

on one convicted for rape"(A. 114).

Sims v. Balkcom, 220 Ga. 7(2) (1964),

is one of the cases cited as the basis

for the court's conclusion. That case

held, in the portion cited by the court,

that the penalty of death for rape is

not "cruel and unusual punishment, such 1

1 / Georgia now has a bifurcated trial.

Ga. Laws 1970, pp. 949, 951, as

amended Ga. Laws 1971, pp. 902-903

(Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2534).

5

as is inhibited by the Federal or State

Constitution." (Id. at 7, 10-12).

Miller v. State, supra, was also cited

for the principle therein enunciated,

that the death penalty did not amount

to cruel and unusual punishment forbid

den by the federal Constitution. Supra,

224 Ga. at 631. Likewise, the case of

Massey v. Smith, 224 Ga. 721, 723 (1969)

was cited. 2 / Relevant to the point

below was Enumeration of Error No. 4 in

that case, which complaint was that the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments made

illegal Massey's sentence of death for

a crime in which life was not taken or

threatened. The court dismissed Mas

sey's contention on the basis of earlier

controlling decisions.

Enumeration No. 7 (Enumeration of

Errors, Supreme Court of Georgia, page

2, unnumbered in Record), which alleged

unequal application of the death penalty

2/ Cert. den. 392 U.S. 912 Massey

v. State, 227 Ga. 257 (1971),

petition for certiorari pending in

U. S. Supreme Court, No. 6985 Misc.

Previous appearances of same case:

220 Ga. 883 (1965); 222 Ga. 143

(1966), cert. den. 385 U.S. 36.

6

to Petitioner because of his race, is

not pressed in this Court (Petitioner's

Brief, pp. 10-11; Petition for Writ of

Certiorari, p. 6). With respect to it,

the Court held:

"As in Miller v. State, supra,at

p. 631, there was no evidence to

support the contention that 'there

exists a discriminatory pattern

whereby the death penalty is con

sistently imposed upon Negro de

fendants convicted of raping

white women.'" (A. 114). 3 /

Thus, the question here is limited

to a review of the judgment of the

Supreme Court of Georgia as it pertains

to Enumeration No. 6. Enumeration

No. 7 is in no way involved or

_3_/ Interestingly, the contention was

made in Massey., supra, 224 Ga. at

723, that under the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments, the punish

ment for Massey, a white man, was

cruel because only 3 of 66 persons

sentenced to death in Georgia for

rape since 1924 were white. The

Court did not even consider the Eighth

Amendment argument worthy of comment,

but instead ruled that no denial of

due process or equal protection was

shown.

7

subject to review here. Petitioner does

not cite it as a basis for the question

at this juncture and,of greater significance,

he does not challenge the court's ruling

that there was no evidence to support a

pattern of discrimination.

Nor could he. The court's ruling

was correct. Illustrative are the analo

gous "systematic exclusion” cases which

similarly claimed denial of equal protec

tion of the laws.

To begin with, the underlying con

cept in those cases is that:

"The very idea of a jury is a

body of men composed of the peers

or equals of the person whose rights

it is selected or summoned to deter

mine ; that is, of his neighbors,

fellows, associates, persons

having the same legal status in

society as that which he holds."

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100

U.S. 303, 308 (1880).

A reason for this fundamental pro

vision was stated by the Court in that

case:

"It is well known that prejudices

often exist against particular

classes in the community, which

sway the judgment of jurors, and

8

which, therefore, operate in

some cases to deny to persons of

those classes the full enjoyment

of that protection which others

enjoy."

* * *

"Without the apprehended existence

of prejudice that [equal protection]

portion of the [Fourteenth] amend

ment would have been unnecessary,

and it might have been left to the

States to extend equality of pro

tection. " Id. at 309.

The Court concluded that the State

statute in effect discriminated against

Negroes in the selection of jurors and

therefore amounted to a denial of equal

protection of the laws to a Negro per

son when he was tried. _!/ There, of

course, the statute was invalid on its

face because of what it did. It was

thus a discrimination made by law.

_4_/ The statute provided that only

white males were liable to serve

as jurors. id. at 305.

9

In Tarrance v. Florida, 188 U.S.

519 (1903), the plaintiffs in error

contended that they were denied equal

protection by reason of an actual dis

crimination against their race in the

selection of jurors. They did not chal

lenge the law itself, but rather its

application. This Court recognized that

equal protection could be denied as

well by actual discrimination as by that

created by law:

"But such an actual discrimi

nation is not presumed. It must

be proved or admitted." _Id. at

520.

No evidence was submitted in the trial

court in support of the allegations, ex

cept an affidavit stating that the facts

contained in the motion to quash the

indictment were true "to their best

knowledge, information, and belief."

Id. at 521. This was deemed insufficient.

In Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S.

354 (1939), jury discrimination was

again complained of. Petitioner did

not contend that Louisiana laws require

an unconstitutional exclusion of the

Negroes from the grand jury but rather

that his evidence showed that the State,

acting through its administrative officers,

had deliberately and systematically

excluded Negroes from jury service because

10

of race, contrary to the equal protec

tion of the laws guaranteed by the

Constitution. The State appellate

court held that the evidence presented

to the trial court on the motion to

quash did not establish that members

of the Negro race were systematically

excluded. Since petitioner asserted

that his evidence did show such ex

clusion, the question before this Court

was made to turn upon the disputed

questions of fact. The Court said:

"In our consideration of the

facts, the conclusions reached

by the Supreme Court of Louisi

ana are entitled to great

respect. Yet, when a claim is

properly asserted - as in this

case - that a citizen whose

life is at stake has been de

nied the equal protection of

his country's laws on account

of his race, it becomes our

solemn duty to make independent

inquiry and determination of

the disputed facts - for equal

protection to all is a basic

principle upon which justice

under laws rests." id. at

358.

The Court examined at length the

evidence which had been presented to the

trial court on the motion and concluded

11

that there was a strong prima facie

showing that Negroes had been systemat

ically excluded because of race, and

that it was not overcome by contrary

evidence. The Court held that the

Petitioner had proved his case and that

the indictment against him should have

been quashed.

The Court in considering the ques

tion of systematic exclusion in Whitus

v. Georgia. 385 U.S. 545 (1967), said:

"'The burden is, of course, on

the Petitioners to prove the

existence of purposeful dis

crimination' Tarrance v.

Florida [citation omitted].

However, once a prima facie

case is made out the burden

shifts to the prosecution."

Id. at 550.

The "prima facie" case in Whitus

consisted of evidence adduced in the

trial court at the hearing on the chal

lenge to the array of petit jurors.

Whitus, supra, 385 U.S. at 547; see 222

Ga. at 112, 114. This Court concluded

that the concrete evidence presented

concerning the method of obtaining prospec

tive jurors, the racial makeup of the commun

ity, and the racial percentages of jurors drawn

12

constituted a prima facie case of pur

poseful discrimination. Further, it

concluded that the State failed to offer

evidence meeting the burden of rebutting

that case. id. at 552.

Thus, in Strauder, an examination

of the statute itself was sufficient to

make out a case of unequal protection.

Tar ranee, Pierre, and Whi tus, proof

was required to show actual discrimina

tion, because operational rather than

simply facial violation by the state

laws was asserted.

Turn now to the instant case.

Petitioner had alleged below that

the death portion of the penalty statute

had been unequally applied to him because

of his race. His was not an attack on

the statute as it was written, in which

event the statute itself would evidence

discrimination. His attack was instead

aimed at the implementation or applica-

tion of the statute, and thus proof of

actual discrimination was called for.

The record does not reveal any

evidence in this respect presented to

the trial court. Apparently there was

none, because on appeal new factual al

legations were made in the Brief of

Appellant which were not shown to exist

anywhere in the record. The argument

offered to the Supreme Court of Georgia

13

on the question of discrimination, which

was embodied in Enumeration of Error No.

7, was as follows:

"f. The Death Penalty was

Unequally applied. Petitioner

further urges that the death

penalty as to him, a Black, is

violative of the equal protec

tion clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

"In the State of Georgia, since

1924, 63 Negroes have served the

death penalty for rape; since

1924, 3 whites have served the

death penalty for rape; none

for raping Negro women; since

1945, 26 Negroes have served

the death penalty for rape, and

during the same period no whites

have served the death penalty

for rape." Appellant’s Brief

in Supreme Court of Georgia,

p. 8.

The brief, of course, is not a part

of the record before this Court. The

record, moreover, is devoid of any judi

cial proof of the statistics asserted.

Even if the facts asserted in this docu

ment, which is outside the record, had

been admitted, they do not prove that

14

Petitioner was discriminated against

because of his color insofar as his

penalty is concerned. The mere number

of Negroes executed for rape, as compared

with the number of whites executed for

the same crime, has no relevancy, exist

ing alone, to a claim of discrimination.

Numerous factors, such as the comparative

ratio of Negroes in the community, the

ratio of convictions of rape by Negroes,

the comparative circumstances of the

crimes themselves, and the selection of

the jury, to name just a few factors,

would be necessary to support a conclu

sion of discrimination.

Therefore, the court below was

eminently correct in finding that no

evidence supported the bald claim of

racial discrimination and that it

therefore had no merit. Consequently,

its decision offers no ground upon which

to build a complaint cognizable by this

Court. What is more, Petitioner con

ceded the correctness of the Georgia

Supreme Court's ruling in this regard,

by not pursuing it.

His effort now seems to be directed

towards bringing the claim in through

the back door. That is to say, since

he cannot, and does not, dispute the

finding of "no evidence", he attempts

now to maintain instead that he does

15

not need evidence of actual discrimination

in a "cruel and unusual punishment”

context. He asserts in effect that he

is entitled to a presumption of discrimi

nation because of the history of the

Georgia statute setting punishment for

rape, because of the position of most

of the world and a majority of the states

outside of the South _JL/ on the ques

tion, and because of the racial imbalance

in executions for rape since 1930.

Such an attempt must surely fail

at the outset because of the fallacy

of the premise. As this Court made

plain in McGautha v. California, 402

U.S. 183 (1971):

"[I]t requires a strong show

ing to offset this settled

practice of the nation on

constitutional grounds."

Id. at 203.

5/ Which he loosely and inartfully lists

as the "Segregation States", Peti

tioner's Brief, p. 14, as though

such a characterization would lend

some element of proof to the claim.

16

Looking back, it is noted that the

Fourteenth Amendment prohibition against

unequal application of the law, which

Petitioner invoked in Enumeration No.

7 in the court below and expressly

abandoned here §_/ has somehow been

transformed into an Eighth Amendment

"cruel and unusual punishment' claim.

The ease with which this assertion slips

into Eighth Amendment garb highlights its

shallowness. At this stage, the sub

stance of the question may not be so

changed. Rules of the Supreme Court of

the United States, Rule 40(d)(2). Nor

could it be said that the State court's

decision in this regard was "not in

accord with applicable decisions of

this court." Rules, supra. Rule 19(1)

(a) •

The real scope of the question

before the Court must therefore be out

lined so that the argument can be con

sidered in the proper perspective.

Paraphrasing the query as put by the

Court, and particularizing it to Peti

tioner's case, the question is whether

the imposition and carrying out of the

death penalty in the case of Lucious

Jackson, who forcibly raped a young

Petitioner's Brief, p. 16.

17

mother by breaking into her home and

threatening her with a dagger he made

by dismantling her scissors, consti

tutes cruel and unusual punishment in

violation of the Eighth Amendment clause

prohibiting such an infliction, and of

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Petitioner says that the penalty

in his case is invalid because the penal

law itself is unconstitutional, on its

face as compared with the rape penalties

in other countries and states, and in

operation due to its historical origin,

the geography of its existence, and the

number of Negroes executed. He does not

contend that the penalty is excessive

under the circumstances of his case but

rather solely that it is excessive in

all rape cases. That is, he makes no

complaint that if the Court finds the

statutory penalty itself is not contrary

to the Constitution, it was unconsti

tutionally applied to him. He attacks

the statute per se.

Thus, the question as developed

by Petitioner embraces only whether

the statutory maximum of death for rape

is unconstitutional because, as he alleges,

it is not universally accepted, its purpose

as contrived by the legislature and as

18

served in operation, is racial discrim

ination, and it allows a penalty which

would be excessive in any case, even

the worst.

In the broad constitutional con

text, the question is whether the dis

cretionary penalty of death for rape

is forbidden the States as cruel and

unusual punishment because it is a de

nial of a right "implicit in the con

cept of ordered liberty," Palko v.

Connecticut, 302 U.S.319, 325 (193 7 )

or "a denial of fundamental fairness

shocking to the univ ersal sense of

justice." Betts v. Brady, 316 U.S.

455, 462 (1942 ).

19

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The sentence in this case for the

crime of rape bears no unconstitutional

mark of being cruel and unusual. The

basis upon which Petitioner bottoms his

specific attack is an allegation of

racial discrimination. The facts offered

do not support the allegation to any de

gree of certainty, much less to the

degree judicially required to establish

unconstitutionality. Contrary indications

affirmatively point to there being no

racial discrimination in the imposition

of the death penalty as a sentence for

rape. In addition, the application of

the tests heretofore utilized in cases

involving the Eighth Amendment, to the

present inquiry, leads to the conclusion

that the penalty is not beyond the

accepted bounds of decency, is not im

permissibly severe in comparison to the

crime perpetrated, and is a viable tool

rationally related to the protection of

the public and the control of crime,

which aims the State is obligated to

achieve.

20

ARGUMENT

THE IMPOSITION AND CARRY

ING OUT OP THE DEATH PENALTY

IMPOSED BY THE JURY IN THIS

CASE DOES NOT CONSTITUTE A

VIOLATION OP THE CRUEL AND

UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT CLAUSE OF

THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT AND THE

DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT.

I. NO EVIDENCE OF RACIAL DISCRIMINA

TION IS PRESENT, AND THUS IT DOES

NOT CONSTITUTE A FACTOR WHICH

MIGHT RENDER THE DEATH PENALTY

FOR RAPE IN THIS CASE A CONSTI

TUTIONALLY PROHIBITED CRUEL AND

UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT.

Petitioner's primary argument in con

tending that the penalty of death for the

rape committed in this case is cruel and

unusual punishment, is that it was racially

inspired. In addition to the general ar

guments advanced in the Aikens brief 7 /,

Petitioner claims that the death penalty

for rape is unconstitutional because

only 16 states and the federal govern

ment still provide for it, and because its

_Ly Aikens v. California, Supreme Court of

the United States, 1971 Term, No. 68-5027.

21

only purpose must be the implementation

of racial discrimination. These addi

tional factors, he asserts, prove that

it violates contemporary standards of

decency and is excessive.

Respondent relies herein on the

argument it submitted in response to the

brief of Petitioner in Furman v, Georgia,

United States Supreme Court, 1971 Term,

No. 69-5003. In addition, and with re

spect specifically to the instant case,

Respondent shows that Petitioner Jackson

cannot prevail in his claim.

In the first place, the red flag of

racial discrimination is illusory. Peti

tioner does not prove his serious charge

that racial discrimination is a factor,

and the controlling factor, which resulted

in the infliction of the death penalty

upon him. He does not allege that there

was any discrimination in his case, nor is

there any proof even remotely connected to

such a theory. Rather, he alleges that

the death penalty for rape in Georgia only

exists because of discriminatory racial

considerations; that it would not survive

if the props of discrimination against the

Negro race were removed. Thus, as pointed

out previously, his charge is that the law

operates discriminatorily, that the pur

pose and effect of the penalty provision

is the achievement of an impermissible ob

jective .

22

This contention must, of course,

be supported if it is to prevail in

this case. As has been shown, it should

be required to meet the same degree of

proof as a similar charge does when

couched in due process and equal pro

tection terms. See also, Maxwell v .

Bishop, 398 F.2d 138 (8th Cir. 1968).

The fact that the allegation is removed

to a cruel and unusual punishment con

text should not remove it from the

requirements of proof. It is obvious

that a man cannot be punished more

harshly due solely to his race, whether

such be called a denial of equal pro

tection of the laws, or cruel and unu

sual punishment, but the conclusion

that such a case exists must be based

on more than mere allegation and

inference. In this case, the proof

fails to make the case.

(A) Look first at the allegation

concerning the number of executions.

It does not prove discrimination. This

Court observed in Williams v. Illinois,

399 U.S. 235 (1970), that identical

punishment treatment among convicted

defendants is not constitutionally

required.

This was also the subject of Oyler

v. Boles, 368 U.S. 448 (1962). The

recidivists there complained that

other inmates had not been similarly

23

proceeded against, with respect to

receiving harsher penalties for prior

convictions. They invoked the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The Court found that no

ground of violation was alleged, since

although there appeared an unexplained

selectivity, Petitioner did not state

or show what the basis for the selec

tion was. The Court pointed out reasons

other than arbitrary discrimination that

might explain such selection. The Court

went further and suggested that even

conscious selectivity was not unconsti

tutional so long as it was not based

on an unjustifiable standard such as

race. Id. at 454-456.

Similarly, in the present case, the

mere fact that more Negroes than whites

were executed for rape in Georgia

between 1930 and 1968 does not prove

that the reason for Petitioner's death

penalty is racial discrimination in his

sentencing. There is evidence showing

instead that of the persons convicted

of rape, a proportionately greater number

are Negro than are white. According to

the records of the Georgia Department

of Corrections, the following numbers

of persons were received into its

authority due to rape convictions in

the years just prior to and including

24

the year in which Petitioner was sen

tenced: 8/

1965 - 31 Negro

1966 - 49 Negro

1967 - 43 Negro

1968 - 59 Negro

1969 - 52 Negro

- 10 white

- 26 white

- 22 white

- 15 white

- 34 white

Of these, 13 Negro and 5 white persons

received the death penalty. This is

substantially proportionate to the

total number of persons received by the

Department, which is 234 Negro and 107

white.

Also, a higher proportion of persons

arrested for this violent crime against

the person are Negro. For example, in

Atlanta, Georgia, in 1970, 18 white

8/ These numbers were derived from the

ledger books of the State Department

of Corrections, Atlanta, Georgia.

They reflect the year in which those

persons included in the total were

received into the Department's author

ity, rather than the year of sentenc

ing. A delay would occur in cases

where motions for new trial or appeals

carried over to a succeeding year.

25

males and 88 Negro males were booked

for rape. 9/

Also, there are too many variables

which may explain the numbers shown by

Petitioner. The type of crime committed,

how aggravated it was in each case, com

mutations or reduced sentences following

reversals in other cases where the death

penalty was initially imposed by the jury,

all indicate that the number of Negroes

executed as compared with the number of

whites, cannot be taken to lead directly

to the assumption that such a statistic

results from racial discrimination. It

must be kept in mind also that juries are

imposing the sentences, not some official

9 / Atlanta Police Department, 1970

Annual Report, p. 41. Petitioner's

county, Chatham, is also a large

metropolitan area; and the sta

tistics are likely comparable.

26

state organ such as a judge or prosecu

tor or executive authority, or the legis

lature by a mandated death penalty. The

choice is the jury's.

Moreover, the great majority of the

executions between the years of 1930 and

1968, when petitioner received his sentence,

are too far removed to indicate any dis

crimination as to the penalty in Peti

tioner's case. In the eleven years prior

to Petitioner's December trial, that is,

including back through 1958, only four

persons were executed for rape in

Georgia.1^ Whatever attitude prevailed

during the '30's and '40's and whatever

lack of safeguards existed up to the period

in which Petitioner was sentenced, cannot

be presumed prevalent during the time in

question here. changes in jury selection

methods, provision for counsel, non-death-

qualified juries, and the movement towards

greater recognition of Negro equality and

away from the attitudes engendered by

slavery, all palpably affected Petitioner's

trial in ways non-existent in 1930. In

addition, the present attitude of other

ID/ Edward Samuel Smith on January 17,

1958; Leroy Dobbs on November 7, 1958;

Nathaniel Johnson on July 1, 1960; and

George Watt on August 11, 1961. Records

of the State Board of Corrections,

Atlanta, Georgia.

27

states and countries, concerning appro

priate penalties for rape, cannot fairly

be compared to whatever situation pre

vailed in Georgia prior to the '601s.

The distinction would obviously be magni

fied.

(B) Petitioner additionally offers

the history of Georgia's rape statute as

an indication of racial discrimination.

Suffice it to say that even if discrimina

tion were a motive in 1866, there is nothing

to link such a motive to Petitioner's 1968

jury, which represented the standards and

conscience of the community of 1968, not

whatever existed in 1866. The flexibility

which the Georgia penalty statute provides

through its wide range of possible penal

ties removes any rigidness from a legisla

tively imposed penalty and indicates that

today's community believed the death

penalty was justified in this case.

Such flexibility demonstrates in addi

tion that the attitudes of a century

ago, whatever they were, are not imposed

on today's criminal by an unwilling public.

(C) Thirdly, Petitioner insinuates

that the existence of segregation in

Georgia's schools evidences discrimination

in sentencing. Such a connection is to

tally absent, it is obvious. Any segrega

tion maintained until 1954^bears no

UJ See Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483 (1954).

28

relation to what petitioner1s jury con

cluded was a fit penalty for his crime

fourteen years later.

(D) In answer to Petitioner's

"indicator" that death as a maximum

penalty for rape is retained primarily

in the South, discrimination is not there

by shown. Rape is a crime against the per

son which does not result in death. The

fact that only 16 states and the federal

jurisdiction retain this ultimate penalty

for such a crime should not be taken as

any indication of discrimination or, more

broadly, cruel and unusual punishment.

Other crimes which do not amount to the

taking of life also bear the death penalty

in states which do not retain such a

penalty for rape. According to the list

contained in Petitioner Aiken's Brief .13. / >

fifteen states provide the death penalty

for kidnapping if the victim is harmed,for

kidnapping for ransom, or both-lj/ Five

states provide the death penalty for armed

12/ Aikens v. California, 1971 Term,

No. 68-5027, Appendix G, pp. lg-13g.

13/ Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho,

Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Montana,

Negraska, New Jersey, Ohio, South

Dakota, Utah, Washington, Wyoming.

29

assault by a life term prisoner.!§/ Two

states provide the death penalty for rob

bery if the victim is harmed. 15/ The death

penalty is also provided for such other

civilian, non-life-taking crimes as train

robbery^/ train wrecking!^ boarding a train

with intent to commit a felonyisj child

stealing 19/ and attempt or conspirary to

assault a chief of state.2 o/ Thus it cannot

be said that since only seventeen juris

dictions provide the death penalty for

rape, which in the present case was a life-

threatening and life-endangering crime, the

death penalty is so out of order that it

offends the standards of decency in the

community. Compared to kidnapping, it is

often a much more repugnant crime in terms

of the victim's experience, the probable

long-lasting effects on the victim, and

the motive of the attacker.

The death-for-rape states also pro

vide death as a maximum for other non-life- * 1

14 / Arizona, California (or by means likely

to cause great bodily injury), Colorado

(if prisoner is escaped), Pennsylvania

(assault with intent to kill), Utah.1 c / California, Wyoming.

16/ Arizona

17 / California

18 / Wyoming

1 9 / Wyoming

20/ New Jersey

30

taking crimes in addition to rape,2l/so

death for rape is an integral part of the

systems of penal laws of those states and

is not a disproportionate sentence.

The conclusion to be drawn from the

statistics regarding the types of non-life-

taking crimes which call for the death

penalty around the country is that some

states consider certain crimes more serious

than other states do, or that they regard

life imprisonment as insufficient to secure

the state's objectives for criminal punish

ment. At any rate, the conclusion is not

authorized that the states which retain the

death penalty for rape do so because of

aberrant discrimination against Negro

rapists.

Thus, as in Oyler, supra, petition

er's evidence does not show that the penal

ty statute effects a deliberate policy of

discrimination against Negroes insofar as

the death penalty for rape is concerned.

2l/ Of the 16 death-for-rape states, 10

have death-for-robbery of some type,

usually armed, and two have death-

for-burglary: Alabama for robbery;

Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Mis

souri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Texas

for armed robbery; North Carolina for

burglary; and Virginia for burglary,

armed bank robbery, and aggravated

robbery. Aikens Brief, supra, App. G.

31

The discrimination alleged is just as

hypothetical in the present context as

it would be if Petitioner had pursued

the equal protection claim he advanced

below as Enumeration of Error No. 7.

Why should Petitioner's burden to

prove the racial discrimination which

he claims as an "objective indicator"

of cruel and unusual punishment, be

any less than if he were claiming jury

discrimination due to a systematic ex

clusion of Negroes from the jury selec

tion process? In the cases reviewed

earlier, a prima facie case was required.

Here, in the analogous situation where

racial discrimination is claimed in

sentencing as opposed to its being an

infection of the "jury of his peers"

which is the claim in the typical dis

crimination case, comparable proof should

be a requisite.

That is, in order for this Petitioner

to prevail in asserting his entitlement

to a penalty which is not cruel and un

usual, his charge of discrimination should re

quire proof that the penalty was used

exclusively for Negroes in the time per

iod when he was sentenced, that Negroes

consistently received the death penalty

for rape during that period, that the

death penalty was given to Negroes re

gardless of the heinousness of the crime,

that for the same degree of crime white

32

persons consistently received lesser

punishment, and that compared with punish

ments for other crimes, the maximum

punishment for the crime of rape is sub

stantially out of line.

Petitioner instead offers only

superficial proof which amounts to no more

than a cloud of innuendo. It does not

provide a basis for regarding the death

penalty as cruel and unusual punishment

on that account.

An opportunity for revealing any

racial discrimination believed to exist

was available to Petitioner on voir dire

at the outset. If he believed that such

discrimination became evident only after

return of the verdict and imposition of

the sentence, he could have pursued it

in the hearing on the amended motion for

new trial. 22/

Moreover, at least three factors

point in the other direction and indicate

that racial discrimination would not be

found.

See the applicable constitutional

and statutory provisions, App. A,

pp. 2a, 3a, 8a-9a.

33

(1) Statistics:

In Georgia, during the period in

which Jackson was tried and sentenced,

from 1965 through 1969, 13 Negroes have

received the death penalty for rape, and

5 white men have been so sentenced. 33/

Although the total is higher for members

of Jackson's race, the initial cases

and ultimate convictions are also sub

stantially higher so that the higher

number of Negro death penalties may be

explained in part by the base from which

these penalties arise. 33/

(2) The jury selection method in

Georgia at the time of Petitioner's trial

operated to avert discrimination. The

legislature had, in 1967, adopted a new

method based on the voter's lists of the

county, and discarded the previous method

23/ Supra, p. 24.

24/ Supra, pp. 24 and 25.

34

of selecting jurors from the tax lists. 25/

Detailed evidence concerning the method

of selecting prospective jurors in Chatham

County in the year previous to Petitioner's

trial was submitted in Eddie Simmons'

trial in June, 1957. 26/ ^ ruling by the

25/ Ga. Laws 1967, p. 251, App. A,

pp,4a-5a. That statute was subse

quently superceded by the present

law, Ga. Laws 1968, p. 533 (Ga. Code

Ann. § 59-106), which is the same in

the provisions here pertinent.

App. A ,pp6ar-7a. This Court discussed

the new scheme in Turner v. Fouche,

396 U.S. 346 (1970).

26/ The transcript of that evidence was

submitted in the trial of William

Henry Furman and is therefore part

of the record before this Court in

that case. Furman v. Georgia, 1971

Term, No. 69-5003, Transcript of

Trial, beginning after page 11 EE

and continuing to page 3.

35

Supreme Court of Georgia, that systematic

exclusion of Negroes was not shown, is

supported by the evidence described in the

opinion. Simmons v. State. 226 Ga. 110

(1970) .

(3) Jury oath and charge:

The oath which is administered to

juries in criminal cases is provided by

law. Ga. Code § 59-709 (Code of 1933)

provides:

"In all criminal cases, the fol

lowing oath shall be adminis

tered to the petit jury, to wit:

'You shall well and truly try

the issue formed upon this bill

of indictment between the State

of Georgia and A.B., who is

charged [here state the crime

or offense], and a true verdict

give according to evidence. So

help you God.'"

The court instructed the jury that the

punishment was to be fixed "in the exer

cise of the discretion which is left with

you by law. . . ."(A. 109). The solemnity

imposed on such proceedings, in which a

man's fate hangs in balance, is manifest.

36

The faith that a jury will perform its

obligations honorably and fairly is

historically a bulwark of our system of

criminal justice, as recognized most re

cently in McGautha v. California, 402

U.S. 183 (1971). There is not an allega

tion or a shred of fact in this case

which could even raise an inference that

the jury departed from its duties and dis

criminated against Petitioner in setting

his penalty at death rather than recom

mending mercy. Nor does the case rise

any higher in regard to the imposition

of the death penalty for rape generally.

37

II. THE CRUEL AND

UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT

CLAUSE DOES NOT FORBID

THE IMPOSITION OF A

PENALTY OF DEATH FOR

RAPE.

It has been shown that Petitioner

cannot prevail in this case because

he has not properly raised the question

he seeks litigated, and further, because

he does not make out his case. But the

matter need not end there. An examina

tion of the relevant factors will sup

port the affirmative conclusion that

the death penalty for rape in this case

does not exceed the constitutional

limitations on punishment.

In addition to the argument of

Respondent advanced in its brief in

Furman v. Georgia, 1971 Term, No. 69-

5003, Respondent maintains that the

imposition and carrying out of the

death penalty for the rape in this

case meets the tests which determine

whether a punishment is constitutional

ly barred.

(A) The penalty in this case does

not violate "evolving standards of

decency that mark the progress of a

maturing society." Trop v. Dulles,

38

356 U.S. at 86. Nor is it contrary

to "standards of decency more or less

universally accepted." Louisiana ex

rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S.

459, 469 (Mr. Justice Frankfurter con

curring) . See Weems v. United States,

217 U.S. 349, 373.

In this case, the facts show that

the victim was brutally and violently

assaulted by Petitioner, who broke

into her home and repeatedly endan

gered her life and her freedom from

harm with a scissor blade which he

kept pressed against her neck. it

is indisputable that her life was

endangered by the vicious attack.

Petitioner urges a world-wide

standard, but it is submitted that

the national standard is more

appropriate to the question, both

because the attitudes and experience

of other contries with the crime of

rape may be far different than that

prevailing in the United States, and

also because the penalty for rape is

not peculiarly an international

subject matter as was the penalty in

Trop v. Dulles, supra.

In construing the meaning of

"contemporary community standards" in

Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184 (1964),

the Court explained that this meant the

39

society at large, the public, or

people in general so that the concept

under review had a varying meaning

from time to time rather than from

geographical location to geographical

location. 2/ it was stated that:

" . . . the constitutional

status of an allegedly ob

scene work must be deter

mined on the basis of a

national standard. It is,

after all, a national Consti

tution we are expounding."

Id. at 195.

Thus it would appear appropriate to

apply a national standard of decency

to the question of whether our national

constitutional prohibition of cruel

and unusual punishment is infringed

by the penalty in this case.

Most states provide for the

death penalty for some crimes at

least and thus it becomes a matter

of degree, a matter of which crimes

may draw the death penalty without

crossing the barrier of universally

accepted standards of decency. As

27 / Id. at 193.

40

has been shown, -^^in addition to

crimes of homicide, the majority of

states provide the death penalty for

some civilian, peace-time crimes which

do not involve the taking of human

life. The greatest incidence of

such non-life-taking crimes is kid

napping. The nature of that crime

cannot be said to be more vicious,

or more violent, or more serious, or

more damaging to the victim's mental

and physical health than is the crime

of rape, which is an infinitely

greater invasion and disruption of

intimate privacy. Rape, moreover,

generally leaves irreversible scars.

The standard of decency involves

"broad and idealistic concepts of

dignity, civilized standards, humanity,

. . ." Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F„2d

571 (8th Cir. 1968), p. 579. In terms

of the criminal and his punishment, it

cannot be taken as settled that life

imprisonment rather than capital

punishment affords a man a greater

degree of basic dignity or is so

substantially greater a civilized

precept that the alternative punish

ment of death must be cast aside as

barbaric. Reflection on the prospect

of even a long prison sentence fol

lowed by a dismal freedom also leaves

doubt that the death penalty is by

28/ Supra, pp. 28-29.

41

comparison unconstitutionally inhuman

and without dignity. 29/ At the least,

whether life imprisonment in terms of

today's prisons, or the life which a

long-incarcerated man faces upon

release by parole, is so much more

civilized than the death penalty

by comparison that the latter must

be regarded as indecent, is not a

foreclosed question.

With further respect to the

examination of accepted standards of

decency, account must be taken of

the fact that the many jurymen and

appellate court justices and others

who have brought about and affirmed

the sentence of death for rape, are

themselves reflectors of the

29/ See Jacques Barzun "In Favor

of Capital Punishment," 31

The American Scholar, 181-

191, Spring, 1962, reprinted,

Bedeau, The Death Penalty in

America, p. 154. See also

Robert L. Massie, "Death by

Degrees", 75 Esquire, pp.

179-180. April 1971.

42

acceptable standard of decency. 30/

30 / Representative cases in which it

was held that the death penalty

for rape is not cruel and unu

sual punishment are as follows:

Maxwell v. Stephens, 348 F.2d

325 (8th Cir. 1965);

Butler v. State, 285 Ala. 387,

232 S.E .2d 631 (1970);

Craig v. State, 179 So.2d 202

(Fla. 1965), cert, denied

383 U.S. 959;

State v. Crook,253 La. 961, 221

So.2d 473 (1969);

State v. Williams, 255 La. 79,

229 So.2d 706 (1969);

State ex rel. Barksdale v. Dees,

252 La. 434, 211 So.2d 318

(1968);

Gordon v. State, 160 So.2d 73

(Miss. 1964);

State v. Yoes, 271 N.C. 616,

157 S.E.2d 386 (1967);

State v. Rogers, 275 N.C. 411,

168 S .E.2d 345 (1969);

State v. Gamble, 249 S.C. 605,

155 S.E .2d 916 (1967), cert,

denied 390 U.S. 927;

(continued on next page)

43

Is it to be said that the death penalty

for rape is a violation of universally

accepted standards of decency, when

even this Court declined to review the

question in even narrower terms in

Rudolph v. Alabama? 31/

Georgia follows a tough line in

providing the ultimate penalty for rape.

That such a penalty is not used uni

versally for this crime should not

render it unconstitutional since the

Constitution does not require a uniform

system of maximum penalties throughout

the States.

(B) The imposition and carrying

out of the death penalty to protect a

value other than life itself is not

Moorer v.MacDougall, 245 S.C. 633,

142 S.E .2d 46 (1965);

Siros v. State, 399 S.W.2d 547

(Tex. Cr. 1966);

Fogg v. Com., 208 Va. 541, 159

S.E .2d 616 (1968);

Williams v. State, 226 Ga. 140,

173 S.E.2d 182 (1970).

31 / 375 U.S. 889 (1963).

44

inconsistent with the constitutional

proscription against "punishments

which by their excessive . . .

severity are greatly disproportioned

to the offenses charged." Weems v.

United States, supra, 217 U.S. at 371.

The crime in this case was heinous.

Petitioner deliberately invaded his

victim's home and stalked her with a

dagger fashioned from a pair of

scissors. He invaded her baby’s

nursery and secreted himself in the

closet and then overpowered her. He

repeatedly overcame her struggles and

pleas and, fighting her, brutally

forced her subjection to a violent

intrusion of her body, all the while

threatening her life and seriously

endangering it with the scissor blade

he held to her neck.

The values to be protected by the

imposition of capital punishment for

such an act are cogently described in

Sims v. Balkcom, 220 Ga. 7 (1964): 32 /

"No determination of this

question [of whether death

for rape is cruel and unu

sual punishment] is either

JL2/ Reversed on other grounds.

45

wise or humane if it fails

to take full account of the

major place in civilized

society of woman. She is

the mother of the human race,

the bedrock of civilization;

her purity and virtue are the

most priceless attributes of

human kind. The infinite

instances where she has

resisted even unto death

the bestial assaults of

brutes who are trying to

rape her are eloquent and

undisputable proof of the

inhuman agonies she endures

when raped. She has chosen

death instead of rape. How

can a mere mortal man say

the crime of rape upon her

was less than death? Man

is the only member of the

animal family of which we

have any knowledge that is

bestial enough to forcibly

rape a female. Even a dog

is too humane to do such

an outrageous injury to the

female.

"We are not dealing

with the wisdom of capital

punishment in any case.

46

That must be left by the

judiciary to the legisla

tive department. But any

man, who can never know

the haunting torment of a

pure woman after a brutal

man has forcible raped her,

who would arbitrarily clas

sify that crime below murder,

would reveal a callous

appraisal of the true value

of woman's virtue.

"We reject this attack

upon the sentence in full

competence that in so doing

we permit the sovereign

State, which is actually

all the people thereof, to

guard and protect the mothers

of mankind, the cornerstone

of civilized society, and the

zenith of God's creation,

against a crime more horrible

than death, which is the

forcible sexual invasion of

her body, the temple of her

soul, thereby soiling for

life her purity, the most

precious attribute of all

mankind. . . . there can

be no more reprehensible

47

crime [than forcible rape].

k k k

"We would regret to see

the day when this freedom

loving country would lower

its respect for womanhood

or lessen her legal protec

tion for no better reason

than that many or all other

countries have done so. She

is entitled to every legal

protection of her body, her

decency, her purity and her

good name. Anyone so depraved

as to rape her deserves the

most extreme penalty that the

law provides for crime." Id.

at pp. 10-12.

Rape is an absolutely aggravated

bodily attack on one who is incapable

of meeting force with force. It is

a crime of flagrant and serious magni

tude. It is never unpremeditated. It

is never accidental. It is perhaps

the most atrocious indecent act a

man can perform on another human.

To say that it is so much less serious

than murder that it never justifies

the same penalty, is to place the

values which rape destroys so far

48

below the value of human life that the

latter must be said to stand undisput-

ably as humanity's highest value. This

is at the least debatable, and such

being the case, an unconstitutional

disproportion between punishment and

crime in this case cannot be made out.

The retention of the death penalty

as the maximum punishment for rape in

seventeen American jurisdictions itself

indicates how serious the crime is

considered. Taking away the death

penalty only reduces the seriousness

of the crime and cheapens the values

it seeks to protect.

The crime of rape should in fact

be regarded as more and more heinous

as civilized precepts increase. The

greater the progress of our maturing

society, and the more wide-spread the

enlightenment of its people becomes,

so greater becomes the gap between

what society may legitimately expect

of its members and a crime such as

rape. The nature of the crime is not

static in terms of the deviation of

the criminal from accepted norms.

Thus, the punishment, to accurately

reflect the greater departure from

civilized norms which attends the

rapist's act, should itself be

increased rather than the converse.

49

Not only is the death penalty not

disproportionate to the crime in this

case, but it also is not disproportionate

to other punishments. The comparison

with life imprisonment as an alterna

tive has already been discussed. In

terms of the broad constitutional

principles enforceable here, it would

not appear that the alternative of life

imprisonment is so far superior in its

decency and humaneness that death, but

not life imprisonment, constitutes

punishment forbidden as cruel and

unusual. The broad thrust of the Eighth

Amendment's intendment is not meant to

draw so fine a line when opposition to

the death penalty is not universally

felt to be devoid of decency.

Nor is the death penalty for rape

disproportionate as compared with

punishments for other sexual crimes.

The death penalty for rape in Georgia

is part of a scheme which indicates the

high revulsion of such offenses in this

State leading to the utter condemnation of rape

as the most reprehensible crime. The

new Criminal Code of Georgia, effec

tive July 1, 1969, lists nineteen

sexual offenses subject to punishment

ranging from misdemeanor to death. 33/

33 / Appendix B, pp. lb - 4b.

50

The sex crime next to rape in degree

of severity is aggravated sodomy,

which bears a maximum punishment of

life imprisonment. 34 /

As to the proportionate relation

ship between the crime and the punish

ment, it should be noted also that the

crime affects not only the victim, but

also her family and society which must

live in fear of such brutality. In

this case, the young mother had a four-

month -old baby daughter, and a physi

cian husband. Both had to suffer the

consequences of the mother and wife's

ordeal, not only on the day of its

occurrence, but also thereafter.

Since Petitioner does not simply

single out his own case, but contends

that the death penalty is excessive

for every rape, the Court's attention

is drawn to the type of crime which

Petitioner would have the Court rule

could never warrant the penalty of

34J See Willis v. Smith, 227 Ga.

589 (1970), a case which involves

the imposition by a jury of a

life sentence for sodomy.

51

death. See in this connection

Riggins v. State, 226 Ga. 381 (1970);

Kemp v. State, 226 Ga. 506 (1970);

Miller v. State, 226 Ga. 730 (1970);

Jackson v. State, 225 Ga. 39 (1969)

and Jackson v. State, 225 Ga. 553

(1969); Mitchell v. State, 225 Ga.

656 (1969) ; Swink v. State,

225 Ga. 717 (1969); Mathis v . State

224 Ga. 816 (1968); Abrams v. State,

223 Ga. 216 (1967) ; Gunter v. S tel t0 f

223 Ga. 290 (1967); Arkwright v.

State, 223 Ga. 768 (1967); Vanleeward

v. State, 220 Ga. 135 (1964);

Paige v. State, 219 Ga. 569 (1963);

Watt v. State, 217 Ga. 83 (1961);

Johnson v. State, 215 Ga. 448 (1959).

The facts in these cases themselves

speak convincingly of the appropriate

ness of the penalty here attacked.

52

(C) The death penalty in this

case is rationally related to the

permissible aims of punishment.

Williams v. New York. 337 U.S. 241

(1949); Trop v. Dulles, supra.

The question of the State's sta-

utory provision of the death penalty

for the crime of rape, in the context

of the Court's consideration, is neces

sarily narrow. it is not whether the

punishment is good or bad, or more or

less effective than any other punish

ment, but rather whether it is consti

tutionally prohibited by the principles

of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.

As this Court pointed out in Williams v.

Illinois, supra, 399 U.S. at 241:

"A state has wide latitude in

fixing the punishment for State

crimes. " 35_/

35 / Former Chief Justice Warren pointed

this out in an interview in which he

stated his opposition to capital

punishment. The New York Times

reported: "However, he said, capital

punishment should be left to the

states. They are in a position to

experiment with its effects, he said."

New York Times, July 6, 1968, p. 42,

column 1.

53

See also Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 P.2d

138, 154 (8th Cir. 1968).

The distinction between legisla

tive desirability and constitutionality

must be maintained. With that perimeter,

the pertinent question is whether the

death penalty statute for rape trenches

on the constitutionally protected free

dom from cruel and unusual punishment.

To lay to rest any qualms in this

regard, Respondent wishes to add the

following points to the argument already

advanced in its brief in Furman v.

Georgia, 1971 Term, No. 69-5003. The

primary purpose of the State's system

of criminal justice is the protection

of the public. This was pointed out

by Lord Oaksley, president of the

international war crimes tribunal at

Nuremberg, who said:

"The prime and immediate

object of punishment is the

protection of the public.

It is possible to think too

much of the reform of the

criminal." 36 /

36/ New York Times, Monday, August 30,

1971, p. 30M.

What he said at the war trial is pertinent

here:

"I have the greatest horror of

the capital sentence, but a

greater horror of the crimes

which have been perpetrated."

Ibid.

This puts the death penalty for rape,

and the State's interests in retaining

it, in proper context before this Court.

The State's obligation to its citizens

is to make every effort to prevent the

type of crime which the instant case

portrays and to afford freedom from fear of

similar attacks. This overriding obli

gation warrants the threat and imposition

of the death penalty as a device in the

battle. it is particularly true since

the incidence of the crime is measurably

increasing, 21/ and there is no evidence

that another penalty or method is a more

effective deterrent:^That the threat of

37 / "Crime in the United States," issued

by John Edgar Hoover, Director, FBI,

Uniform Crime Reports, 1970, pp.

12-14. Chart. 7 is reproduced as App.C

38/ No guidance is offered by the States

which do not retain the death penalty

for rape, and in some of them, the

rate of rape is substantially higher

than it is in Georgia, where the rate

in 1970 was 16.1 per 100,000 inhabi

tants. Alaska's rate was 26.1, Ari

zona's 27.0, California's 35.1, Colo

rado's 36.0. "Crime in The United

States",supra, pp. 72-73.

55

death is no deterrent has not been proved,

while on the other hand common sense

teaches that leniency would lead to the

belief that rape, after all, is not

such a despicable crime. This is what

advances the breakdown of law and

order. The idea is an ancient one:

"For in a state that hath no

dread of law / The laws can

never prosper and prevail./

Where dread prevails and

reverence withal / Believe me,

there is safety, but the state/

Where arrogance hath license and

self-will / Though for a while,

she run before the gale / Will

in the end make shipwreck and

be sunk." Sophocles, in Ajax.

The utter disregard shown by rapists

for values which society holds at least

as high as the value of life, and in some

cases higher, as demonstrated by those

who have died trying to avoid rape,

warrants death as a commensurate penalty.

These values are honor and virtue,

personal peace and integrity. As com

pared with other serious crimes, rape

is more strenuously to be prevented,

since a bank robber or a burglar wants

only property, whereas a rapist desires

the unwilling submission of another

person's will and body. Another dis

tinguishing factor is that the victim

in a rape, be it woman or child, can

never escape the memory, can never

56

avoid the indelibility of the tarnishing

experience, whereas in theft, burglary,

larceny, or robbery there is not such a

lasting element of personal anguish.

The lack of knowledge to eliminate

crimes such as this one make the reten

tion of harsh penalties mandatory. The

lack of knowledge has been brought about

in part by the long delays in recent

years, and indeed the cessation, of the

carrying out of death penalties imposed

by duly constituted juries. The effec

tiveness of swiftly carried out execu

tions, surrounded by all of the legal

requisites of due process, and including

all of the procedural and substantive

safeguards afforded in recent years,

would afford a more intelligent analysis

of current effectiveness. The consti

tutional mandate does not forbid the

use or resumption of use of this penalty.

CONCLUSION

The death penalty for rape in this

case is not constitutionally infirm.

In the first place, the death penalty

for rape has not been shown to be a

departure from the fundamental standards

of decency which are required of the

State. And as Mr. Justice Holmes stated

nearly fifty years ago:

57

"[I]f a thing has been practised

for two hundred years by common

consent, it will need a strong

case for the 14th Amendment to

affect it, . . . " Jackman v.

Rosenbaum Company, 260 U.S. 22,

31 (1922).

The punishment which Georgia has

held consistent for over one hundred

years should not now be constitutionally

abrogated because of any of the reasons

advanced by Petitioner, as it has not

been shown that it must be counted among

the ranks of forbidden "cruel and unus

ual punishments".

Respectfully submitted,

ARTHUR K. BOLTON

Attorney General

HAROLD N. HILL, JR.

Executive Assistant

Attorney General

COURTNEY WILDER STANTON

Assistant Attorney General

DOROTHY T. BEASLEY

Assistant Attorney General

ANDREW J. RYAN, JR.

District Attorney

ANDREW J. RYAN, III

Assistant District Attorney

58

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Dorothy T. Beasley, Attorney of

Record for the Respondent herein, and a

member of the Bar of the Supreme Court

of the United States, hereby certify that

in accordance with the Rules of the

Supreme Court of the United States, I

served the foregoing Brief for Respondent

on the Petitioner by depositing copies

of the same in a United States mailbox,

with first class postage prepaid, addressed

to counsel of record at their post office

addresses:

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

JACK HIMMELSTEIN

ELIZABETH B. DuBOIS

JEFFRY A. MINTS

ELAINE R. JONES

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

BOBBY L. HILL

208 East 34th Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

MICHAEL MELTSNER

Columbia University Law School

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

This ______ day of __________ , 1971.

DOROTHY T. BEASLEY

APPENDICES

la

APPENDIX A

STATUTORY PROVISIONS AND RULES INVOLVED

Constitution of the State of Georgia

of 1945, Article I, Section I, Paragraph

IX (Ga. Code Ann. § 2-109, 1948 Revision)

Bail; fine; punishment; arrest; abuse

of prisoners. - Excessive bail shall not

be required, nor excessive fines imposed,

nor cruel and unusual punishments inflict

ed; nor shall any person be abused in

being arrested, while under arrest, or

in prison.

Constitution of the State of Georgia

of 1877, Article I, Section I, Paragraph

IX (Ga. Code Ann. § 2-109, 1948 Revision)

Bail; fines; punishment; arrest; abuse

of prisoners. - Excessive bail shall

not be required, nor excessive fines

imposed, nor cruel and unusual punish

ments inflicted; nor shall any person

be abused in being arrested, while

under arrest, or in prison.

2a

Constitution of the State of Georgia

of 1945, Article I, Section II, Paragraph

I (Ga. Code Ann. § 2-201, 1970 Cummula-

tive Supplement). (6382) Paragraph I.

Libel; jury in criminal cases; new trials

restrictions as to property near certain

Federal highways. - In all prosecutions

or indictments for libel the truth may

be given in evidence; and the jury in

all criminal cases shall be the judges

of the law and the facts. The power of

the judges to grant new trials, in case

of conviction, is preserved. . . .

Ga. Code § 27-2301 (Ga. Code Ann.

1953 Revision). (1059 P.C.) Jury judges

of law and facts; general verdict; form

and construction of verdicts. - On the

trial of all criminal cases the jury

shall be the judges of the law and the

facts, and shall give a general verdict

of "guilty" or "not guilty." Verdicts

are to have a reasonable intendment, and

are to receive a reasonable construction,

and are not to be avoided unless from

necessity. (Const., Art. I, Sec. II,

Par. I (§ 2-201). (Cobb, 835)

3 a

4a

Ga. Laws 1967, pp. 251-252:

§"59-106— Immediately upon the passage

of this Act and thereafter at least

biennially, or, if the judge of the

superior court shall direct, at least

annually, on the first Monday in August,

or within sixty (60) days thereafter,

the board of jury commissioners shall

compile and maintain and revise a jury

list of upright and intelligent citizens

of the county to serve as jurors. in