San Antonio Independent School District v Rodriguez Appendix for Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 1, 1972

129 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. San Antonio Independent School District v Rodriguez Appendix for Brief Amici Curiae, 1972. 5b5b739e-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/eefcc12b-2704-47d9-87c7-c32a4cdf715e/san-antonio-independent-school-district-v-rodriguez-appendix-for-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

/U, g

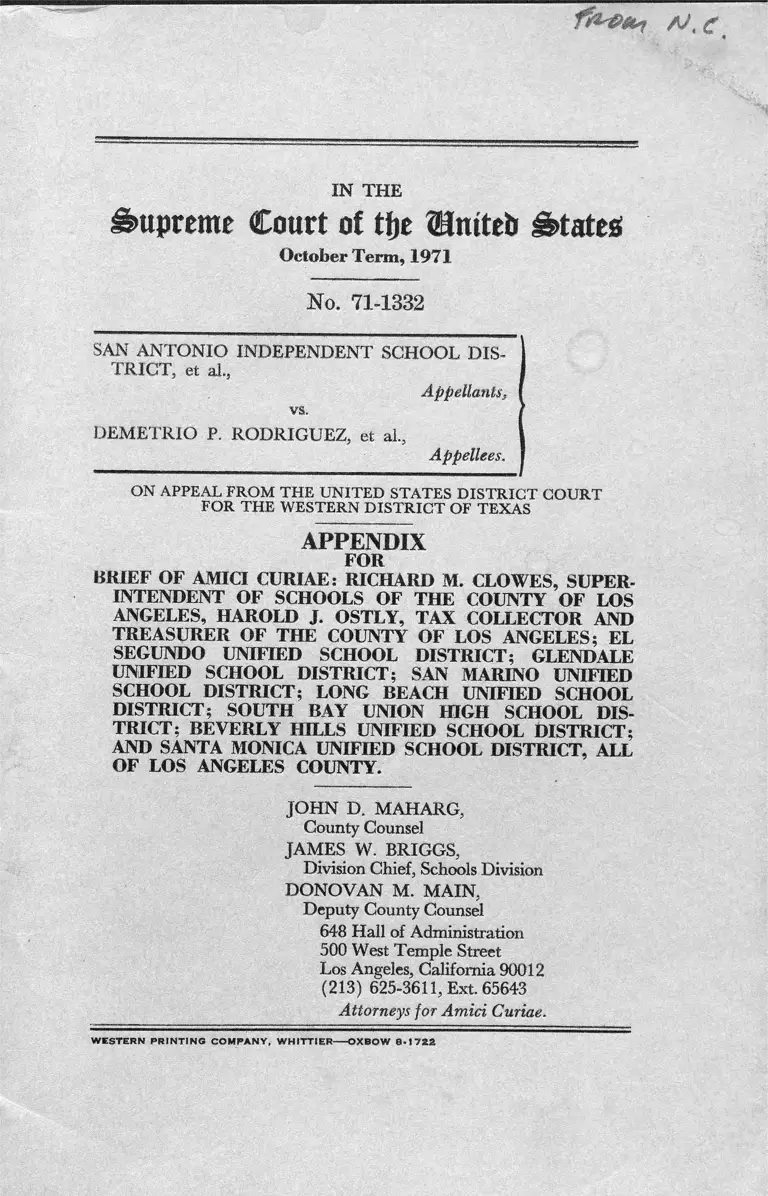

IN T H E

Supreme Court of tfje Urnteb g>tate$

October Term, 1971

No. 71-1332

SAN A N T O N IO IN D E P E N D E N T S C H O O L D IS

T R IC T , et a l,

Appellants,

vs.

D E M E T R IO P. R O D R IG U E Z , et a l,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

APPENDIX

FOR

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE: RICHARD M. CLOWES, SUPER-

INTENDENT OF SCHOOLS OF THE COUNTY OF LOS

ANGELES, HAROLD J. OSTLY, TAX COLLECTOR AND

TREASURER OF THE COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES: EL

SEGUNDO UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT; GLENDALE

UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT; SAN MARINO UNIFIED

SCHOOL DISTRICT; LONG BEACH UNIFIED SCHOOL

DISTRICT; SOUTH BAY UNION HIGH SCHOOL DIS

TRICT; BEVERLY HILLS UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT;

AND SANTA MONICA UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT, ALL

OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY.

JO H N D . M A H A R G ,

County Counsel

JAM ES W . BRIGGS,

Division Chief, Schools Division

D O N O V A N M . M A IN ,

Deputy County Counsel

648 Hall of Administration

500 West Temple Street

Los Angeles, California 90012

(213) 625-3611, Ext. 65643

Attorneys for Amici Curiae.

W E S T E R N P R IN T IN G C O M P A N Y , W H IT T IE R ----- O X B O W 3 * 1 7 2 2

APPENDIX '“ A”

INTERDISTRICT INEQUALITIES IN SCHOOL

FINANCING: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF

SERRANO v. PRIEST AND ITS PROGENY.

S t e p h e n R. G o l d s t e i n +

Rarely has a state supreme court decision received

such extensive publicity and public comment as the

recent California Supreme Court opinion in Serrano v.

Priest,3 concerning the constitutionality of interdistrict

disparities in financing California public school dis

tricts. Indeed, one might have to go back to the United

States Supreme Court reapportionment cases to find

a decision of any court that has been as extensively dis

cussed in the press as has Serrano. .Most significantly,

the press comment seems to have been uniformly af

firmative. The Serrano result has been popularly hailed

as rightly egalitarian and a significant, if not the sig

nificant, step in the struggle for better education in

urban areas.2 Even those editorial writers who have

traditionally been proponents of judicial restraint have

refrained from commenting adversely upon the court’s

decision invalidating California’s public school financ

ing system.

tAssociate Professor of Law, University of Pennsylvania. A.B. 1959, L.L.B.

1962, University of Pennsylvania, Member, Pennsylvania Bar.

*5 Cal. 3d 584, 487 P.2d 1241, 96 Cal. Rptr. 601 (1971).

'2See, e.g., N.Y. Times, Sept. 1, 1971, at 17, col. 1: id., Sept. 2, 1971, at

32, col. 1; at 55, cols. 1, 2; id., Sept 5, 1971, § 4, at 7, col. 1; at 10, col.3.

Ill part this absence of adverse comment may be

attributable to the fact that it was the California Su

preme Court and not the United States Supreme Court

that decided the case. Yet, the decision’s impact is

clearly not confined to California. The California

school finance system is similar in effect to the systems

used in 49 of the 50 states/ and the court avowedly

rested its decision on federal equal protection grounds.4

3Hawaii is the only state without local school district control of education.

H a w a ii R e v . L a w s §§296-2, 298-2 (1968).

4The court specifically rejected the argument that the California financing

system violated art. XX, §5 of the California Constitution, which provides for

“ a system of common schools.” It then stated: “ Having disposed of these

preliminary matters, we take up the chief contention underlying plaintiffs'

complaint, namely that the California public school financing scheme violates

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.” 5 Cal. 3d at 596, 487 P.2d at 1249, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 609.

Despite having thus based its decision on federal constitutional grounds, the

court, in a puzzling footnote, id. at 596 n .ll, 487 P.2d at 1249 n .ll, 96

Cal. Rptr. at 609 n .l l , then referred to 2 provisions of the California Con

stitution requiring that “ [a ]11 laws of a general nature shall have a uniform

operation,” C a l . C o n s t , art. I, §11, and prohibiting “ special privileges or

immunities,” id. art. I, §21. The court went on to state that:

We have construed these provisions as “substantially the equivalent” of

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Fed

eral Constitution. (Dept, of Mental Hygiene v. Kirchner (1965) 62 Cal.

2d 586, 588, 43 Cal. Rptr. 329, 400 P.2d 321.) Consequently, our

analysis of plaintiffs’ equal protection contention is also applicable to

their claim under these state constitutional provisions.

Id.

Following this, there was no further mention of the California Constitu

tion in the opinion and almost all authorities cited concern federal law. The

court also devoted considerable effort to avoiding the argument that the

federal constitutional issues has been foreclosed by the United States Supreme

Court summary affirmances in Mclnnis v. Shapiro, 293 F. Supp. 327 (N.D.

111. 1968), aff’ d mem. sub nom. Mclnnis v. Ogilvie, 394 U.S. 322 (1969), and

Burruss v. Wilkerson, 310 F. Supp. 572 (W.D. Va. 1969), aff’d mem.] 397

U.S. 44 (1970). The California Supreme Court, of course, would not be limited

by a United States Supreme Court interpretation of the California Constitution.

The footnote quoted above, and the explicit citation to Kirchner, however,

raise the issue whether, despite its express reliance on the Federal Consti

tution, the court has not also relied on the California Constitution in a way

that precludes United States Supreme Court review.

In Kirchner, the Califoria Supreme Court held unconstitutional a state

statute relating to liability for the care and maintenance of mentally ill per

sons in state institutions. 60 Cal. 2d 716, 388 P.2d 720, 36 Cal. Rptr. 488

(1964). The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari but vacated

and remanded the case to the California court on the grounds that the Cal

ifornia opinoin was unclear as to whether it was based on the federal or state

It has also been expressly followed by a federal dis

trict court in Minnesota in denying a motion to dis

miss5 and by a three-judge district court in Texas in

holding that state’s financing scheme unconstitutional."

While it is clear, at least at this time, that the Serrano

decision itself will not be reviewed by the United States

Supreme Court,7 * there are many other interdistrict

consitutions or both, and that the United States Supreme Court would not

have jurisdiction unless the federal Constitution had been the sole basis for

the _ decision, or the state constitution had been interpreted under what the

California court deemed the compulsion of the Federal Constitution. 380 U.S.

194 (1965). On remand, the California Supreme Court stated that although

C a l . C o n s t , art I, §§11 & 21 were generally thought to be “ substantially

the equivalent” of the federal aqual protection clause, the court was “ inde

pendently constrained” in its result by these sections of the state constitution.

The court stated that it had not acted “ solely by compulsion of the Fourteenth

Amendment, either directly or in construing or applying state law . ” 62

Cal. 2d 586, 588, 400 P.2d 321, 322, 43 Cal. Rptr. 329, 330 (1965).

Although the issue is not completely free from doubt, the California Su

preme Court in Serrano may have written an opinion expressly based on federal

law yet at the same time insulated from review by the United States Supreme

Court.

®Van Dusartz v. Hatfield, 334 F. Supp. 870 (D. Minn. 1971).

^Rodriguez v. San Antonio Ind. School Dist., 337 F. Supp. 280 (W.D.

Tex. 1971). Procedurally, Rodriguez has developed further than Serrano, as

the court there, after a hearing, declared the Texas financing scheme un

constitutional and permanently enjoined the defendants, the State Commis

sioner of Education, and the members of the State Board of Education, from

enforcing it. The court, however, stayed its mandate and retained jurisdiction

for 2 years:

in order to afford the defendants and the Legislature an opportunity to

take all steps reasonably feasible to make the school system comply with

the applicable law . . . .

The Court retains jurisdiction of this action to take such further steps

as may be necessary to implement both the purpose and spirit of this

order, in the event the Legislature fails to act within the time stated . . . .

Id. at 286. For retention of jurisdiction the court cited cases of judicially im

posed reapportionment plans.

7See note 4 supra. In addition to the problem of the independent state

ground for the Serrano decision, it is clear that the Supreme Court cannot

review it at this time because it is not a final judgment. See 28 U.S C. §1257

(1 9 7 0 ).

inequality cases in the process of litigation,8 at least

one of which will soon present the United States Su

preme Court with the Serrano problem.9

The primary reason for the favorable reception of

Serrano is probably the growing public eagerness for

its result. Unlike many other societal problems in ed

ucation and other areas, the concept of fiscal equality

in education is perceived as unambiguously good. It

does not appear to involve the competing views of

equality prevalent in desegregation and community

control issues. Nor does it represent the significant

clash between the values of equality and liberty that

the desegregation and community control issues may

present. The only visible liberty being curtailed is local

economic self-determination, a value currently of low

priority in our society when balanced against the prom

ise of improving education for the poor and racial

minorities. Fiscal equality also holds out the promise

of improving education for the poor and racial minor

ities, without raising the fears of personal adverse ef

fects on the white middle-class family aroused by other

proposed policies, such as desegregation. Fiscal equali-

8Also pending before a 3-judge court is the constitutionality of the Florida

school financing system. See Askew v. Hargrave, 401 U.S. 476 (1971), vacat

ing per curiam Hargrave v. Kirk, 313 F. Supp. 944 (MX). Fla. 1970). Recent

state court decisions that followed Serrano are: Hollins v. Shofstall, No. C-

253652 (Super. Ct. Maricopa County, Ariz. Jan. 13, 1972); Robinson v. Ca

hill, 118 N.J. Super. 223, 287 A.2d 187 (1972); Sweetwater County Planning

Comm, for the Organization of School Dists, v. Hinkle, 491 P.2d 1234 (Wyo.

1971). In disagreement with Serrano is Spano v. Board of Educ., 328 N.Y.

S.2d 229 (Sup. Ct. 1972). The issue is now before the court in more than half

the states. See Wall St. J., Mar. 2, 1972, at 1, col. 6.

9It appears that the decision in Rodriguez is immediately appealable to

the United States Supreme Court. See 28 U.S.C. §1253 (1970). If appealed,

it would presumably be heard in the October term, 1972.

t,y involves the movement of inanimate dollars, not live

children.10

Finally, fiscal equality corresponds to a basic

American belief that more money, or money distributed

more wisely, can solve major societal problems such as

the current state of public education, and that all so

ciety need do is to have the will to so spend or dis

tribute it. In Daniel P. Moynihan’s terms, Serrano

leads one to hope that what may have been considered

a “ knowledge problem” is indeed a “ political” one,

or better yet, a judicial one.11

Serrano is unquestionably sound as a matter of ab

stract egalitarian philosophy. Nevertheless, there are

many difficulties presented by its legal analysis. More

over, it is not at all clear that the practical effect of the

decision will be to improve the quality of public educa

tion generally, or the quality of urban public education

in particular.

■— 5—

lOThe Serrano result and metropolitan desegregation, e.g., Bradley v. School

Bd., 40 U.S.L.W. 2446 (E.D. Va. Jan. 5, 1972), can be viewed as alternative

methods of improving the educational quality of urban minority groups, to the

extent that the argument for metropolitan desegregation rests on a desire to

give the black urban poor access to the tax base of their more affluent white

suburban neighbors. Compare Hobson v. Hansen, 327 F. Supp. 844 (D.D.C.

1971), with Johnson v, San Francisco Unified School Dist., No. C-70 1331

SAW (N.D. Cal. June 2, 1971). See also Spencer v. Kugler, 40 U.S.L.W.

3333 (U.S. Jan. 17, 1972); United States v. Board of School Comm’rs 332

F. Supp. 655 (S.D. Ind. 1971).

u Moynihan, Can Courts and Money Dc ft?, N.Y. Times, Jan. 10, 1972.

§E (Annual Education Review), at 1, col. 3; id. at 24, col. 1.

6

I . S c h o o l D i s t r i c t I n e q u a l i t y a n d t h e

Serrano R e s p o n s e

A. The Court’s Response to Interdistrict

Financing Differentials

As is true with every state except Hawaii, over 90%

of California’s public school funds derive from a com

bination of school district real property taxes and state

aid based largely on sales or income taxation. Histori

cally the state aid, or ‘ ‘ subvention, ’ ’ has been superim

posed on the basic system of locally raised revenue. Al

though the state aid component of educational expen

ditures has been generally increasing as a percentage

of the total expenditures, the local component has re

mained dominant, California is typical in having total

educational expenditures consist of 55.7 percent local

property taxes and 35.5 percent state aid.12

The local component is a product of a locality’s tax

base (primarily the assessed valuation of real property

within its borders) and its tax rate, Tax bases in Cali

fornia, as elsewhere, vary widely throughout the state.

Tax rates also vary from district to district.

12ln addition, federal funds account for 6.1% and other sources for 2.7%.

These figures and others given for California in this Article are taken from the

court’s opinion in Serrano. 5 Cal. 3d at 591 n.2, 487 P.2d at 1246 n.2 96

Cal. Rptr. at 606 n.2.

In discussig expenditure differentials, the Serrano court did not indicate

whether or not its figures included federal revenues. Other authorities have

excluded federal revenues from these calculations. This author has elsewhere

questioned the validity of this exclusion. See Goldstein, Book Review, 59 C a l if .

L. R ev . 302, 303-04 (1971). Nationwide, approximately 52% of all schooi

revenue is collected locally, and from 97-98% of local tax revenue is derived

from property taxes. Briley, Variation between School District Revenue and

Financial Ability, in St a t u s an d I m p a c t of Ed u c ation al F in a n c e Pr o

gram s 49-50 (R. Johns, K. Alexander & D. Stoilar eds. 1971) (National

Educational Finance Project vol. 4). In California, all local school revenues

are raised by property taxation. See C a l . Ed u c . C ode §§20701-06 (1969)

-7—

Tiie state component of school expenditures is gen

erally distributed through a flat grant system, a foun

dation system, or a combination of the two. The flat

grant is the earliest and simplest form of subvention,

consisting of an absolute number of dollars distributed

to each school district on a per-pupil or other-unit stan

dard. Foundation plans are more complicated and have

a number of variants. In its simplest form, a founda

tion plan consists of a state guarantee to a district of

a minimum level of available dollars per student, if the

district taxes itself at a specified minimum rate. The

state aid makes up the difference between local collec

tions at the specified rate and this guaranteed amount.

I f the actual tax rate is greater than the specified rate,

the funds raised by the additional taxes are retained

by the locality but do not affect the amount of state aid.

Finally, there are combinations of flat grants and

foundation plans. Under one form of combination plan

the flat grant is added to whatever foundation aid is

due to the district:

State Aid = [guaranteed amount — local collec

tion at specified rate] + flat grant.

Under the other combination system, the flat grant is

added to the local collection in initially calculating the

foundation grant:

State Aid = [guaranteed amount — (local col

lection at specified rate + flat grant)] + flat

grant.

Under tliis approach, a district that would qualify for

a state foundation grant equal to, or in excess of, the

flat grant does not in effect receive the flat grant. That

grant is superfluous when it serves only to bring a dis

trict up to the foundation level, because a district is

always guaranteed the foundation level in any case.

The full benefit of the flat grant goes only to those dis

tricts where the local collection at the specified rate

equals or exceeds the foundation guarantee.

The latter combination plan is the system employed

in California.13 The flat grant is $125 per pupil. The

foundation minimum, based on a tax rate of 1.0 percent

for elementary school districts and 0.8 percent for high

school districts,14 is $355 for each elementary school

pupil and $488 for each high school student, subject to

specified minor exceptions. An additional state pro

gram of “ supplemental aid” subsidizes particularly

poor school districts that, are willing to set local tax

rates above a certain statutory level. An elementary

school district with an assessed valuation of $12,500 or

less per pupil may obtain up to $125 more for each

child under this plan. A high school district whose as

sessed valuation does not exceed $24,500 per pupil can

18As noted, this results in the quirk that the full effects of the flat grant

are available only to those districts whose revenue at the prescribed rate ex

ceeds the foundation guarantee. There would seem to be no rational basis for

this result. The Serrano court, however, did no more than mention this fact

and there is no indication that the opinion rested on it.

14This is simply a computational tax rate used to measure the relative tax

bases of the different districts. It does not necessarily relate to the actual rates

levied.

receive a supplement of up to $72 per pupil if it taxes

at a sufficiently high rate.15

Although the foundation plan does help to equalize

available educational funds throughout the state, the

relatively low foundation guarantee nevertheless allows

significant disparities among school districts. The Ser

rano court cited the following statistics for the 1969-

1970 school year for district per-pupil educational ex

penditures :

Elementary

Low $ 407

Median 672

High 2586

H igh School

'$ 722

898

1767

Unified16

$ 612

766

2414

Statistics cited by the court for assessed valuations per

pupil also reflected the disparities:

15There are other minor provisions in the state subvention system. Districts

that maintain “ unnecessary small schools” receive $10 per pupil in their

foundation guarantee, a sum intended to reduce class sizes in elementary

schools. Unified districts (those which contain both elementary and secondary

schools) receive $20 more per pupil in foundation grants. In addition, a spe

cial program attempts to provide equalization in districts included in re

organization plans that were rejected by the voters. It gives the poorer dis

tricts in the reorganization the effect of the reorganization to the limited

extent of levying a tax areawide, of 1.0% in elementary districts and 0.8%

in high school districts. The resulting revenue is then distributed among the

individual districts according to the ratio of each district’s foundation level to

the areawide total revenue. Thus, in these rare circumstances of voter-re

jected reorganization plans, poorer districts share in the higher tax bases of weal

thier districts in their area. The districts are, of course, free to tax themselves

above the 1.0% or 0.8% level and retain all additional revenue. 5 Cal. 3d

at 593 n.8, 487 P.2d at 1247 n.8, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 607 n.8.

!«W . at 593 n.9, 487 P.2d at 1247 n.9, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 607 n.9.

10

Low

Median

High

Elementary

$ 103

19,600

952,156

High School17

$ 11,959

41,300

349,093

The complaint in Serrano set forth two main causes

of action. The first was that of plaintiff school children

residing in all school districts except the one that “ af

fords the greatest educational opportunity,” who al

leged that:

As a direct result of the financing scheme . . . sub

stantial disparities in the quality and extent of

availability of educational opportunities exist and

are perpetuated among the several school districts

of the State . . . . The educational opportunities

made available to children attending public schools

in the Districts, including plaintiff children, are

substantially inferior to the educational opportuni

ties made available to children attending public

schools in many other districts in the State . . . ,18

The financing scheme was alleged, therefore, to violate

the equal protection clause of the fourteenth amend

ment and various clauses of the California Constitu

tion.

17Id. Note that these figures and those in the text accompanying note 16

supra, represent the extremes and thus may be skewed, as extremes often are.

In this case a major skewing mechanism may be an abnormally low number

of public school students in a given district. Even outside the extremes, how

ever, the discrepancies in California are substantial. These assessed valuation

per pupil figures also assume uniform assessment practices. This assumption

was not discussed by the court. The discrepancies were much less substantial

in Texas but the system was invalidated nonetheless. See Rodriguez v. San

Antonio Ind. School Dist., 337 F. Supp. 280 (W.D. Tex. 1971).

185 Cal. 3d at 590. 487 P.2d at 1244, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 604.

11

The second cause of action, brought by the parents

of the school children, as taxpayers, incorporated all

the allegations of the first claim. It went on to allege

that as a direct result of the financing scheme, plain

tiffs were required to pay a higher tax rate than tax

payers in many other school districts to obtain for

their children the same or lesser educational opportun

ities.

The complaint sought: (1) a declaration that the

system as it existed was unconstitutional; (2) an order

directing state administrative officials to reallocate

school funds to remedy the system’s constitutional in

firmities ; and (3) retention of jurisdiction by the trial

court so that it could restructure the system if the leg

islature failed to do so within a reasonable time19 The

trial court sustained a general demurrer to the com

plaint and the action was dismissed. The dismissal of

the complaint for failing to set forth a cause of action

was appealed to the California Supreme Court.

The California Supreme Court stated the issue in

the first line of its opinion:

We are called upon to determine whether the

California public school financing system, with its

substantial dependence on local property taxes and

resultant wide disparities in school revenue, vio

lates the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.20 10

10Id. at 591. 487 P.2d at 1245, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 605.

20Id. at 589, 487 P.2d at 1244, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 604.

—12—

The court immediately went on to hold:

We have determined that this funding scheme in

vidiously discriminates against the poor because

it makes the quality of a child’s education a func

tion of the wealth of his parents and neighbors.

Recognizing as we must that the right to an edu

cation in our public schools is a fundamental in

terest which cannot be conditioned on wealth, we

can discern no compelling state purpose necessitat

ing the present method of financing. We have con

cluded, therefore, that such a system cannot with

stand constitutional challenge and must fall before

the equal protection clause.21

In so holding, the California court employed the

“'new equal protection” analysis. Under this doctrine,

certain t y p e s of legislative classification require a

higher level of state justification to pass judicial scrut

iny than is required under the traditional “ rational

basis” equal protection test. This doctrine holds that

if a suspect classification is employed, and the classi

fication pertains to a fundamental interest,22 then the

21Id.

22It is unclear whether the court regarded the fundamental interest and

suspect classification tests as operating in conjunction with each other as stated

in the text or as operating independently. Compare id. at 612 487 P.2d at

1261, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 621, with 5 Cal. 3d at 604, 487 P.2d at 1257, 96

Cal, Rptr. at 615. To the extent the court suggested that either test, operating

independently, would trigger the “ special scrutiny” review of state action, it

appears to be an inaccurate view of the present state of the law as applied to

state actions other than racial classifications.

The invariable formulation of the doctrine as applied to wealth classifica

tions requires both wealth classification and impairment of a fundamental in

terest in some varying combination. See Bullock v. Carter, 40 U.S.L.W. 4211,

4214 (U.S. Feb. 24, 1972); Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S. 471, 519-30

(1970) (Marshall, J., dissenting). But see Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618,

658 (Harlan, J., dissenting.) See generally J. C o o n s , W. C l u n e & S. Su g ar -

m a n , Private W e a l t h a n d P u blic Ed u cation 339-446 (1970) [hereinafter

cited as Private W e a l t h an d P u blic Ed u c a t io n ].

13—

classification violates the equal protection clause un

less it is necessitated by a compelling state purpose. A

fuller discussion of the Serrano court’s use of this doc

trine follows.

B. The Choice of a Standard of Equality:

Response to Activist Legal Scholarship

The most striking element in the California Su

preme Court’s holding was its reliance on the relation

ship between the wealth of a school district and its ed

ucational expenditures. By “ wealth” the court meant

taxable wealth (property tax basis23 * * * *) per pupil o'r other

unit. Yet, as stated above, the local component of school

financing is a product of taxable wealth and tax rate.

A district’s expenditures may be low because it is low

in taxable wealth or because it chooses to tax itself at

a low rate, or both. Why, then, did the court focus on

wealth differences as the constitutional vice, rather

than on disparities in expenditures, regardless of

cause %

23Serrano and its progeny have been predicated on the assumption of the

exclusive use of the real estate property tax for local education financing. As

stated in note 12 .supra, however, nationwide property taxes constitute 97-98%

of local taxes for education and thus are almost the exclusive but are not the

exclusive means of local financing. Indeed, by 1968-1969, 22 states and the

District of Columbia authorized the use of local nonproperty taxes by local

school districts. A lt e r n a tiv e Program s for Fin a n c in g Edu cation 186

(1971) (National Educational Finance Project vol. 5). While this still

amounted to less than 3% of local education taxes nationwide, in a given state

the amount could be sufficiently significant that the Serrano analysis premised

on exclusive real estate taxation would be inapplicable. For example, in Penn

sylvania local nonproperty taxes in 1968-1969 produced a mean revenue per

pupil of $101.30 in central city districts. Id. 187.

Local nonproperty taxes include occupational, utility, and other excise

taxes, as well as local sales and income taxes. Tax bases for such taxes would

be much more difficult to calculate than is a given locality’s real property tax

base.

14—

To understand this, one must know something about

the legal literature that predated Serrano. The litera

ture in this field, particularly the book Private Wealth

and Public Education,24 exemplifies a current wave of

consciously activist scholarship, written with an avowed

bias, and aimed at producing specific legal results. This

new breed of writers, not content with pure scholar

ship, actively engages in the litigation process to ac

complish their aims.23 This activist legal scholarship—

of a very high caliber—-produced the legal formulations

manifested in Serrano™

Serrano apparently adopted as the constitutional

ride what was denominated as Proposition 1 in Private

Wealth and Public EducationP “ The quality of public

education may not be a function of wealth other than

the wealth of the state as a whole.” 28 Proposition 1

24Supra note 22.

25Coons and Sugarman, for example, filed amicus briefs in Serrano and

Rodriguez.

28Although the court acknowledged its reliance on Coons, Clune & Sugar-

man by citations throughout the opinion, it cited a law review article, Coons

Clune & Sugarman, Educational Opportunity. A Workable Constitutional Test

for State Financial Structures, 57 C a l if . L. R e v . 305 (1969), rather than the

more comprehensive analysis in Private W e a l t h and P ublic Ed u c a tio n ,

supra note 22. The reason for this is not clear. This may reflect only the

opinion writer’s relative access to the two works. It may also reflect the court’s

sensitivity to the reader’s relative access to the two works. Finally, it might

be suggested that it represents a possible reflection of the difference in esteem

in California, between the California Law Review and the Harvard University

Press.

27The following discussion of Proposition 1 and district power equalizing

is based upon, and some parts are taken entirely from, an earlier analysis of

Private Wealth and Public Education by this author. Goldstein, Book Review

59 C a l if . L. R e v . 302, 304-10 (1 9 7 1 ).

28Private W e a l t h an d P u blic Edu cation , supra note 22, at 2 (emphasis

omitted). Proposition 1 is, however, never directly quoted by the Serrano

Court. The federal court in Van Dusartz, 334 F. Supp. 870 (D. Minn. 1971)

which expressly relied on Serrano. did quote Proposition 1 and explicitly ac

cepted it as the constitutional standard. Id. at 872 & n.l. Somewhat less

itself was a response to prior debate about interdistrict

disparities in educational offerings. Recently there has

been increased concern with inequalities in government,

services, especially as they affect the poor. In particu

lar, society has become increasingly concerned with

the deplorable condition of urban public education. It

has been argued that a major cause of this condition is

the relative lack of resources available to urban school

districts as compared to their more affluent suburban

neighbors. Moreover, there has been increased recogni

tion that plans for improving urban education through

such alternatives as integration, decentralization and

community control, or compensatory education are, in

the final result, highly dependent on the availability

of greater resources for urban school districts.

Although the exact relationship between financially

Poor school districts and poor people, particularly the

urban poor, is unclear,29 the existence of large wealth

discrepancies among school districts is undeniable. The

disparity in the quality of education, as conventionally

measured, between urban and suburban school districts

clearly the 3-judge court in Rodriguez seemed to adopt Proposition 1 as the

constitutional rule.

One caveat must be stated regarding the Serrano court's acceptance of

Proposition 1 as the constitutional test. As will be discussed at length text

accompanying notes 30-44 infra, Proposition 1 and Serrano do not require

equality of expenditures. Neither, however, is Proposition 1 satisfied by equality

of expenditures. If equal expenditures were achieved by differential rates ap

plied to differential tax bases, that is, lower tax base districts achieving the

same revenue level by employing higher rates, Proposition 1 would not be satis

fied. At this point Proposition 1 leaves education as its concern and becomes

completely taxpayer oriented. Despite the taxpayer orientation in Serrano, see

text accompanying notes 86-9! infra, it is unlikely that the Serrano court

would go this far. Throughout the opinion, the court emphasized differential

educational expenditures.

29See notes 65-75 infra & accompanying text.

is also apparent. Thus the existing system of education

al financing has been increasingly condemned as in

tolerable. However, there has existed substantial dis

agreement on methods of relief. Opponents of judicial

intervention have argued against court action to in

validate the current system: first, for lack of a work

able judicial standard ; secondly, because an equality

concept might result in a downward leveling of expen

ditures when the real need is to improve low quality;

thirdly, because judicial relief would result in centra

lization of educational financing; and fourthly, because

an equality requirement that prevented local school

expenditures above the state norm would be either

unworkable or would result in substantial middle class

exodus from the public schools.30

Proposition 1 was an avowed attempt to respond to

these criticisms. By adopting it, the California Su

preme Court has apparently limited its decision to

wealth-derived educational differentials and has not

required equal expenditures statewide. On this basis

of decision, there are a number of alternative school

financing systems that would meet the court’s constitu

tional standard. Among these is abolition of local school

districts and their replacement with a completely state

wide system. Short of that, centralized state financing 80

80See Kurland, Equal Educational Opportunity. The Limits of Constitu

tional Jurisprudence Undefined, 35 U.C h i . L. R ev . 583 (1968). For the

views of the proponents of judicial intervention, see A, W is e , R ic h Sc h o o l s ,

Poor Sc h o o l s : T h e P ro m ise of Eq u a l Ed u c a tio n a l O p p o r t u n it y 143^

59 (1968); Horowitz & Neitring, Equal Protection Aspects of Inequalities in

Public Education and Public Assistance Programs From Place to Place With

in a State, 15 U.C.L.A. R e v . 787 (1968) : Kirp, The Poor, the Schools, and

Equal Protection, 38 H a r v . Ed u c . R ev . 635 (1968).

17-

that raises and distributes all funds could be coupled

with local district administration of the schools. Cen

tralized financing, however, is not required under the

Serrano rule invalidating only wealth-derived differ

entials. A general school redistricting' that equalized

wealth among school districts would satisfy the deci

sion and at the same time allow the present system of

financing and administration to continue. Finally,

there is the innovative suggestion proposed in Private

Wealth and Public Education—district power equaliz

ing—a system t h a t allows differential expenditures

among school districts, while removing the effect of

differential tax bases on these expenditures.

Under district power equalizing, existing school dis

tricts would have funds available for education based

on their tax rate regardless of their tax base. A school

district would be free to choose any tax rate it desired

and its available funds—defined as “ x dollars per edu

cational unit” —would be established by the state for

any given tax rate. In a simplified model, a district

power equalizing scheme might appear as follows:

Tax Hate Available Funds

1 % $ 400 per educational task unit

2 /a

3

2

600

800

1000

1200

A district with a low tax base whose chosen tax rate

produced less revenue than the state prescribed amount

18

wpuld receive state funds to make up the difference.

A district that produced more revenue than the state

prescribed amount at its chosen rate would be required

to pay the excess to the state.

The scheme of power equalizing as a means to satis

fy the requirements of Proposition 1 has been attacked

on equalitarian grounds. It requires merely that dis

trict wealth disparities be eliminated as a factor in

financing education, thus still permitting districts to

spend more by taxing more. What is in fact required,

it is argued, is statewide equality of learning oppor

tunity to the extent achievable by statewide financing.81

The Serrano decision is subject to the same attack in

sofar as the court adopts an equal wealth formula, ra

ther than an equal expenditure formula.

It is not indisputably clear, however, that the

court has rejected th e equalization o f expenditures

formula. Although the language quoted above, a n d

other statements in the opinion seem to accept the

equal wealth standard, it might well be argued that

the court decided only the facts before it—that the

existing financing scheme was unconstitutional—and

did not go so far as to endorse an equal wealth stan

dard or reject the argument that an equalization of ex

penditures standard is constitutionally required. In

deed, in response to an argument that autonomous lo

cal decisionmaking was so important a value that it

31See, e.g., Silard & White. Intrastate Inequalities in Public Education:

The Case for Judicial Relief Under the Equal Protection Clause, 1970 Wis

L. R e v . 7, 26-28, 30.

19-

justified the existing system, the court stated: “ We

need not decide whether such decentralized financial

decision-making is a compelling state interest, since

under the present financing system, such fiscal free

will is a cruel illusion for the poor school districts.” 32

Other evidence of the court’s possible acceptance of the

equal expenditure formula as being constitutionally

required is its specific recognition that many of the

values of local choice could still be preserved under a

spending equalization formula that centralized financ

ing but localized administration of schools.

The court’s possible failure to rule out a constitu

tional command of expenditure equalization may also

be explained by the fact that tax base, not tax rate, is

the main determinant of local educational expendi

tures. Available statistics, in California and elsewhere,

indicate that districts with smaller tax bases, such as

Baldwin Park, tax themselves at higher rates than do

richer districts, such as Beverly Hills, even though

their total yield is not as great,33 Therefore, the Ser

rano court may have assumed that Proposition 1, which

removes the wealth factor, would produce generally

equal offerings among school districts, and thus left

until another day the issue of what happens if it does

not.

These reasons, however, are not sufficient to ex

plain the very strong equal wealth emphasis in the

325 Cal. 3d at 611, 487 P.2d at 1260, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 620.

ssid . ; Private W e a l t h and Public Ed u c a tio n , supra note 22, at 127-50.

See also A ltern ative Program s for F in a n c in g Edu cation 81-101 (1971)

(National Educational Finance Project vol. 5).

20

Serrano opinion. The most logical reading of the de

cision is that the court did adopt the formula of equal

wealth rather than the equal expenditures formula as

its constitutional command. The probable explanation

for this is twofold. First, an expenditure equalization

standard would cause problems with compensatory edu

cation and other programs that would devote extra

funds for the education of disadvantaged students. The

propopents of equal expenditures are also in favor of

this degree of inequality and struggle valiantly to make

these concepts consistent. Perhaps their struggles are

successful. It is much easier, however, to avoid the in

consistency by not adopting an equal expenditure test-

in the first place.

The second basic argument in favor of an equal

wealth standard is that it permits a local school dis

trict to choose how much it wishes to spend on the ed

ucation of its children. The desirability of retaining

this local choice responds to basic federalist, pluralist

values of diversity and local decisionmaking—-a con

cept termed “ subsidiarity” in Private Wealth and

Public EducationP In Serrano the state argued that

the existing school financing system was constitutional

ly valid because it incorporated just these values.85

^ P rivate W e a l t h an d Public Ed u cation , supra note 22. at 14-15. Sub

sidiarity is “ the principle that government should ordinarily leave decision

making and administration to the smallest unit of society competent to handle

them.” Id. 14. See also Goldstein, Book Review, 59 C a l if . L. R e v . 302, 306

(1971).

35The court quoted the state’s argument that:

“ [I ] f one district raises a lesser amount per pupil than another

district, this is a matter of choice and preference of the individual dis

trict and reflects the individual desire for lower taxes rather than an

expanded educational program, or may reflect a greater interest within

— 21—

The court’s response, while rejecting the state’s arg

ument, shows sensitivity to the idea of local choice:

[S]o long as the assessed valuation within a dis

trict’s boundaries is a major determinant of how

much it can spend for its schools, only a district

with a large tax base will be truly able to decide

how much it really cares about education. The poor

district cannot freely choose to tax itself into an

excellence which its tax rolls cannot provide. Far

from being necessary to promote local fiscal choice,

the present financing system actually deprives the

less wealthy districts of that option.86

The Serrano court did recognize that local choice

in nonfiscal educational matters might still be retained

under centralized financing; yet this limited degree of

choice is not sufficient. As a purely theoretical issue it

is difficult to determine the value of retaining local

control over educational spending, particularly when

weighed against the possibility of continuing expendi

ture inequalities, which the retention of local choice

produces. But this issue is not merely a matter of po

litical theory. Rather, adoption of the equal wealth

standard in Serrano is an implicit recognition of the

fact that, in light of our history and traditions, judicial

or legislative decrees cannot be used to prevent local-

ilies from trying to get better education for their chil

dren by raising more funds locally.

that district in such other services that are supported by local property

taxes as, for example, police and fire protection or hospital services.”

5 Cal. 3d at 611, 487 P.2d at 1260, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 620.

22

A in-e-Serrano law review article37 by Silard and

White, which dismissed district power equalizing in

one paragraph as not producing equality of educational

offerings, ended discussion of its equalization solution,

centralized financing, by adding: “ The [centralized

financing] mechanism might also be formulated in such

a way as to retain a local option to surtax for addi

tional education.” ™ This “ local option” is obviously

a device to allow localities to spend more on education

than the centrally determined norm, and thus produce

inequalities in offering. Despite their very strong com

mitment to egalitarian principles, proponents of judi

cial action in this field obviously cannot resist the no

tion that local districts should retain the option to

spend more on education. It is this fact, deeply em

bedded in our public consciousness, that primarily ex

plains why the Serrano court did not and would not

require spending equality.39

The existence of this public sense raises a further

question about the limits of Serrano. Is the Silard and

White system—centralized financing with a local op

tion surtax—consistent with the California court’s con

stitutional standard? While the spending equalization

standard is not required under Serrano, it remains to

be seen what minimal remedies are consistent with the

®7Silard & White, supra note 31.

S8W. 29 (emphasis added).

_S9Thi_s public feeling was clearly expressed in the response to the Serrano

decision in a New York Times editorial. After hailing the case on egalitarian

grounds, the editorial abruptly concluded with the assertion that the ideal so

lution for school financing lies in centralized state financing “without discour-

aging additional investments by education minded communities in the better

ment of their schools.” N.Y. Times, Sept. 2, 1971, at 32, col. 1.

standard actually adopted by the court, and thereby

determine the limits of its holding. Any appearance of

consistency between Serrano and the surtax proposal

is nothing more than a semantic illusion, unless the

surtax were based on power equalization or another

scheme that removed differential tax bases as an ele

ment in a district’s ability to surtax itself. Otherwise

the surtax has the same constitutional defect as that

condemned in Serrano because the quality of a child’s

education remains dependent on the district’s wealth.

In fact, the surtax system is the present system in Cal

ifornia—it is the foundation plan. The justifications

for the surtax are the reasons given above for preferr

ing district power equalizing* over expenditure equali

zation—subsidiarity and the deeply embedded feeling

that one cannot preclude a locality from taxing itself

more heavily, if it so chooses, to get better education

for its children. But, if one accepts the Serrano equal

protection reasoning, these concepts and this felt need

are only sufficient to justify the surtax if the surtax

is necessitated by a compelling state purpose. It is not

clear that these factors even provide a sufficiently com

pelling purpose to justify district power equalizing.

Even if they do, however, they would not justify a non

power equalized surtax. Such a surtax is not necessary,

because its objective of allowing local choice can be

achieved by power equalizing. Thus, because it has the

(S'errario-determined constitutional vice of differential

expenditures related to differential tax bases that

power equalizing does not have, it must be invalid un

der Serrano.

24

The proposal of a centralized financing system with

a local surtax option also suggests that the evils of

school finance might be remedied merely by increas

ing the minimum spent per child. Following this line,

a system that increased the California foundation plan,

say from $500 to $1000, might be said to accomplish the

goal of providing to each student, regardless of the

district in which he resides, an adequate level of edu

cational expenditure. Such a constitutional standard

would be based not on equal protection but on a con

stitutional right to an affirmative minimum provision

of services similar to that suggested by Professor

Frank Miehelman and discussed later in a footnote to

this Article.40 One of the most fundamental objections

to this concept of minimum provision of services is the

inability of courts to determine at what point the mini

mum of a given service has been reached. In the hypo

thetical above, $1000 was used, but why should the min

imum not be $1200? Indeed, why is the current mini

mum of approximately $500 unacceptable ? Apparently

the California legislature believed it to be sufficient.

One might simply argue that a minimum of $500 is

unreasonable, a determination that a court could make

without having to determine exactly what the minimum

should be. Such an approach, however, ignores the need

for judicial standards as illustrated by recent Supreme

Court history. As happened in reapportionment be- 0

i0See note 84 infra; Miehelman, Forward: On Protecting the Poor Through

the Fourteenth Amendment, The Supreme Court, 1968 Term, 83 H a r v . L .

R e v . 7 (1 9 6 9 ).

tween the Baker v. Carr*1 “ rationality” test and the

Reynolds v. Sims42 “ one man-one vote” test, once a

court defines a principle it is difficult to stop short of

setting- a minimum standard.48

Lastly, one may argue that, under a system with a

sufficiently large state minimum, the surtax is merely

a minor deviation that will be permitted under Serrano

in the same manner that the United States Sup'reme

Court has allowed a degree of deviation from mathe

matical precision under its one man-one vote rule. The

two situations are not comparable, however. The sur

tax, unlike the unavoidable, inconsequential deviations

o f voting district mathematics, is a policy decision to

allow some school districts to make their schools un

equal to schools in other districts. The more apt reap

portionment analogy is deviation for policy prefer

ences, such as protecting rural areas. Such policy pre

ferences have been rejected by the Supreme Court in

the reapportionment cases.44 Of course, in school fi

nancial equalization there will b e deviations f r o in

«-369 U.S. 186 (1962).

42377 U.S. 533 (1964).

43Professor Michelman recognized this when he hypothesized the applica

tion of his minimum protection theory to education. After suggesting that each

child was constitutionally entitled to a minimum provision of education, he

concluded that minimum provision would mean equalization. He based this

conclusion on the fact that education is valued because of its relevance to

competitive activities; thus the minimum required for A must be determined

in relation to what his competitor, or future competitor, B, is receiving. While

there is merit in this position, Professor Michelman overstates it when he

thereby equates the minimum with no substantial inequality. The fact that he

does so, however, is indicative of the standardless nature of the minimum pro

vision theory. Professor Michelman thus is driven to equalization in order to

provide a standard. Michelman, supra note 40, at 47-59,

^See Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533. 562-68 (1964). But see Abate v.

Mundt, 403 U.S. 182 (1971).

26

mathematical certainties as a result of such things as

differential labor costs and economies of scale. Such

deviations occur because o f a practical inability t o

achieve perfect equality. The surtax is not such a de

viation. It represents a conscious decision to create in

equality.

II. D i s t r i c t W e a l t h D i s c r i m i n a t i o n : A S u s p e c t

G l a s s i f i c a t i o n ?

While the California Supreme Court’s reliance on

an equal wealth formula thereby precludes resort to

remedies such as the surtax system, and limits the

holding so that it does not require expenditure equa

lization, the court’s adoption of equal wealth has sig

nificance beyond its force as a limitation. Wealth dis

crimination was, in fact, the affirmative basis used to

invalidate an almost universal school financing system.

The Serrano court cited “ wealth discrimination” as

one of the “ suspect classifications” that, in conjunc

tion with a fundamental interest, triggered the “ new

equal protection. ’ HS

The Serrano court held that “ this funding scheme

invidiously discriminates against the poor because it

makes the quality of a child’s education a function of

the wealth of his parents and neighbors,” 46 that is, the

wealth of his school district. The factual data relied

on by the court in reaching this result, however, con

sisted of disparities in tax bases and school expendi-

Cal. 3d at 597, 487 P.2d at 1250. 96 Cal. Rptr. at 610.

Mid. at 590, 487 P.2d at 1244, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 604.

—27

tures among school districts. Therefore, two basic ques

tions must be answered before this holding is 'related

to the data:

1. What is the relationship between school expen

ditures and the “ quality” of a child’s education?

2. What is the relationship between poor districts

—districts with low taxable wealth—and poor people?

A. The Relationship of Expenditures to Educa

tional Quality

The problem of relating levels of educational ex

penditures to quality of education is a persistent and

annoying one. For one thing, there is no consensus on

what the desired educational outputs are, or how edu

cational quality should be measured. Secondly, there

is very little empirical data to support a finding of an

affirmative relationship between expenditure levels

and measurable educational outputs.

The Coleman Report,47 the leading study attempt

ing to correlate selected educational outputs with vari

ous inputs, founds little relationship between expendi

ture levels and the educational outputs it measured,

when other variables were held constant.48 While the

Coleman Report’s methodology has been attacked per

suasively,49 affirmative data that dispute its conclusion

47O ffice of Ed u c a t io n , U.S. D e p ’ t of H e a l t h , Edu cation & W e l

fare , Eq u a l it y of Ed u c ation al O p p o r t u n it y (1966).

48See id. 20-21, 312-16.

49See Bowles & Levin, The Determinants of Scholastic Achievement— An

Appraisal of Some Recent Evidence, 3 J. H u m an R esource s 3 (1968).

-28

remain minimal.30 The Coleman Report and other

studies are concerned with spending differentials only

within the relatively narrow range of current school

expenditures. The lack of correlation between expendi

ture levels and educational outputs in this range does

not preclude the possibility of some absolute minimum

of expenditures being necessary to achieve measurable

educational outputs. Further, this absence of correla

tion between expenditures and outputs is more under

standable when it is recognized that approximately

two-thirds of a typical school district’s revenues are

spent for teacher salaries.51 Differences in teacher sal

aries are often a function not of teaching quality, but

of such indirectly related factors as longevity and ed

ucational degrees. Differences in salary scales among

districts may be the result of such factors as differ

ential general wage scales and the bargaining power of

teacher unions. The Serrano court discussed the prob

lem of relating expenditures to quality in a footnote

and admitted that “ there is considerable controversy

among educators over the relative impact of eduea-

50Some support for a correlation between expenditure level and quality

of education is found in J. G u t h r ie , G . K lf.in d o r fe r , H. L evin & R. St o u t ,

Sc h o o l s an d I n e q u a lit y (1971). This support, however, is hardly sufficient

to support a judicial finding of correlation. Moreover, a recently published re

examination of the Coleman data by a score of eminent social scientists in a

faculty seminar at Harvard University has confirmed the findings of the orig

inal report, while avoiding some of the original report’s methodological prob

lems. Indeed, this reexamination indicates that the influence of school ex

penditures on student achievement is even weaker than was indicated by

the original Coleman Report. See Hosteller & Moynihan, A. Pathbreaking

Report, in O n E q u a l it y of Ed u c a tio n a l O p p o r t u n it y 36-45 (F. Mosteller

& D. Moynihan eds. 1972): Jencks, The Coleman Report and the Conven

tional Wisdom, in id. 69-115; Smith, Equality of Educational Opportunity:

The Basic Findings Reconsidered, in id. 230-42.

51Schoettle, The Equal Protection Clause in Public Education. 71 C o lu m

L. R ev . 1355, 1359 (1971).

29

tional spending and environmental influences on school

achievement . . . .” 52

The court avoided the problem in two ways. One

was to cite other cases that have rejected the argument

that there is no proof that different levels of expendi

ture affect the quality of education.53 Except for the

latest decision in Hobson v. Hansen,5i discussed below,

these cases have not given a rationale for this rejection.

Secondly, the court relied on the procedural pos

ture of the case. Since the complaint was dismissed on

demurrer, the court countered the defendant’s conten

tion that different levels of educational expenditures

do not affect the quality of education with the state

ment that “ plaintiffs’ complaint specifically alleges

the contrary, and for purposes of testing the sufficien

cy of a complaint against a general demurrer, we must

take its allegations to be true.” 55 It is not clear that

this approach was consistent with the court’s earlier

statement that the California procedure is to “ treat the

B25 Cal. 3d at 601 n. 16, 487 P. 2nd at 1253 n. 16, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 613

n. 16.

ss/d . The court cited Mclnnis v. Shapiro, 293 F. Supp. 327 (N.D. 111.

1968), aff’d mem. sub nom. Mclnnis v. Ogilvie, 394 U.S. 322 (1969), in

which a 3-judge federal court stated, without a supporting citation, in the

course of rejecting a constitutional attack on interdistrict differentials in school

financing, “ [presumably, students receiving a $1000 education are better

educated that [sic] those acquiring a $600 schooling.” 293 F. Supp. at 331.

In another case cited in Serrano, Hargrave v. Kirk, 313 F. Supp. 944 (M.D.

Fla. 1970), vacated on other grounds per curiam sub nom. Askew v. Hargrave,

401 U.S. 476 (1971), the district court stated: “ [I]t may be that in the

abstract ‘the difference in dollars available does not necessarily produce a

difference in the quality of education.’ But this abstract statement must give

way to proof to the contrary in this case.” 313 F. Supp. at 947. No proof on

this issue, however, was ever stated by the court in Hargrave and the opinion

goes on not to discuss this, but to discuss the inability of school districts to

raise school revenues under the Florida system.

543 2 7 F. Supp. 844 (D.D.C. 1971).

525 Cal. 3d at 601 n. 16, 487 P. 2d at 1253 n. 16, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 613

30—

demurrer as admitting all material facts properly

pleaded, but not contentions, deductions or conclusions

of fact or law.” 515 The court did not explain why, for

example, the possibility of a causal relationship be

tween expenditures and educational quality would not

be considered a contention of fact. .More significantly,

the reliance on this procedural posture, if this is what

the court did, means that the issue still remains open

for proof—proof that does not appear to be available.

The authors of Private Wealth and Public Educa

tion, in enunciating the equal wealth standard, try to

finesse the problem by stating the issue as equality of

resources available to the student rather than as equal

ity of educational offerings. What is available, they

then contend, are the goods and services purchased

by school districts, and there is no reason to assume

that the money spent for these goods and services is

not the appropriate measure of their value.57

The problems may also be avoided in terms of bur

den of proof. When A shows that the state is spending-

more money on B than on him, the state must respond

by demonstrating either that this fact is irrelevant be

cause A is not really receiving less than B, or that even

if A is receiving less, the differential is still constitu

tionally permissible. Available data are insufficient to

support a state’s assertion that expenditures are irrele

vant to educational equality and thus the issue shifts to

Mid. at 591, 487 P.2d at 1245, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 605.

B’ Private W e a l t h and P u blic Ed u cation , supra note 22, at 25-27.

—31

a determination of the constitutionality of differential

treatment. This burden of proof approach to the issue

was apparently the one taken by Judge Wright in the

latest decision of Hobson v. Hansen/’8 although there

were also elements of estoppel involved in the Hobson

court’s reliance on the school administration’s own as

sertions of a correlation beteen educational 'resources

and quality of education.38

While the burden of proof argument has appeal as

an expedient solution it is not a completely satisfying

basis for judicial invalidation of a longstanding method

of public school financing. From this perspective, arg

uments for judicial action must be discounted some-

Avhat by uncertainty about the present system’s detri

mental effect on the quality of education, and also

therefore, by doubts of improving education by such

invalidation.60

58327 F. Supp. 844, 854-55. The court in Hobson was not concerned with

a correlation between gross expenditures and quality of education, but rather

with the specific differences in expenditures on teacher salaries, rated on a

per pupil basis, between essentially “ white” and “ black” schools within the.

District of Columbia. The quality-expenditure issue in terms of teacher sal

aries per pupil was posed as the correlation or lack thereof between quality-

instruction and higher salaries. Phrasing the issue as “ teacher salary per pupil”

also raised the issue of the relationship between educational quality and class

size or student-teacher ratio.

58Id. at 855.

«oprofessor Moynihan has suggested that:

[t]he only certain result that will come from [a rise in educational ex

penditures, which he states Serrano will produce] is that a particular

cadre of middle-class persons in the possession of certain licenses— that

is to say teachers— will receive more public money in the future than

they do now.

Moynihan, Can Courts and Money Do It?, N.Y. Times, Jan. 10, 1972, §E

(Annual Education Review) at 24, col. 1. Note that by ordering equalization

of teacher salaries per pupil between “ white” and “black” schools, Judge

Wright in Hobson v. Hansen, 327 F. Supp. 844 (D.D.C. 1971), allowed the

school district the choice of transferring higher paid teachers from “white”

schools to “black” schools or reducing the student-teacher ratio in the “ black”

schools. Although the evidence of correlation between class size and pupil

-32—

13. The Relationship of Poor Districts to Poor

People

The second question raised by the wealth analysis

underlying the Serrano holding centers on the supposed

relationship between a school district’s wealth, as mea

sured by its real estate tax base, and the personal

wealth of its people. For its wealth classification argu

ment the court relied on United State Supreme Court

“ de facto wealth classification” cases in which states

have been restricted in imprisoning indigents for fail

ure to pay fines,01 have been required to provide indi

gent criminal defendants with such things as tran

scripts02 and attorneys for appeal,63 and have been pre

cluded from requiring the payment of a poll tax as a

precondition to voting.64 All of these eases, however, in

volved “ wealth classifications” that operated against

individuals, whereas Serrano involved school districts.

The issue in Serrano would therefore be simpler if the

wealth of school districts coincided with the wealth of

its people, thus making poor districts aggregates of

poor individuals.

Available statistics, however, do not indicate this

hypothesized 'relationship between poor districts and

performance does not seem significantly greater than that between average

teacher salary and pupil performance, one’s subjective sense is that the class

size is the more significant factor to education. Both the intradistrict and racial

aspects of Hobson also strengthened the case for judicial intervention.

"Williams v. Illinois, 399 U.S. 235 11970); Tate v. Short, 401 U.S. 395

\ 1^ / I / •

62Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956).

,!8DougIas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963).

84Harper v. State Bd. of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966).

33-

poor people. One recent study of 223 school districts

in eight states indicates that there is no substantial

pattern of differences in real estate tax basis per pupil

among seven categories of school districts: major ur

ban core cities, minor urban core cities, independent

cities, established suburbs, developing suburbs, small

cities, and small towns.66 It is true that the three-judge

federal district court which invalidated the Texas

school financing system in Rodrigues v. San Antonio

Independent School District found that “ those dis

tricts most rich in property also have the highest medi

an family income and the lowest percentage of minority

pupils, while the poor property districts are poor in

income . . . . ” 06 The basis for this finding was an affi

davit submitted by plaintiffs and cited by the court.

As a basis for the court’s conclusion, this was a ques

tionable source; a careful reading of the data contained

in the affidavit creates grave doubts about the validity

of its conclusions.67

e5S ee A lt e r n a tiv e Program s for F in a n c in g E d u cation 83-89 (1971)

(National Educational Finance Project vol. 5).

66337 F. Supp. at 282 (W.D. Tex. 1971).

e7The Rodriguez court cited the affidavit as showing a median family in

come of $5900 in the 10 districts with the highest tax base per pupil and $3325

in the 4 districts with the lowest tax base per pupil. Id. at 282 n.3. The fol

lowing are the study’s figures:

Market Value of

Taxable Property

Per Pupil

Above $100,000

(10 Districts)

$100,000-$50,000

(26 Districts)

$50,000-$30,000

(30 Districts)

$30,000-$10,000

(40 Districts)

Below $10,000

(4 Districts)

Median Family

Income From

1960

$5900

Per Cent

Minority

Pupils

8%

State & Local

Revenues Per

Pupil

$815

4425 32 544

4900 23 483

5050 31 462

3325 79 305

34

In tlie amicus brief filed in Serrano by the Harvard

Centers for Educational Policy Research and for Law

and Education, an attempt was made to avoid the ab

sence of statistics correlating poor people and poor

school districts, by defining the injured class as those

poor people who also live in poor school districts,68 Al

though the amicus brief never explains the basis for

this definition of the injured class, it may be argued

that the people in this narrow group are singularly

disadvantaged because they have neither the advantage

of a high tax base as do the poor in rich districts, nor

the mobility68 and private school alternatives of the

more wealthy residents of poor school districts. The

flaw in this approach is that defining the injured class

in these terms considerably weakens the wealth classi

fication argument. The system no longer can be said

to discriminate against the poor but only against a

certain segment of the poor. In fact, when the school fi

nance system is viewed from this perspective, the chief

beneficiaries of the system when the class is so defined

Affidavit of Joel S. Berke at 6 (footnotes omitted).

The 5 category breakdown of school districts seems to be arbitrary, and it

is only this breakdown which appears to produce the correlation of poor

school districts and poor people. Even on this breakdown, however, the cor

relation is doubtful. Note the very small number of districts in the top and

bottom categories. Even more significant is the apparent inverse relationship

between property value and median income in the three middle districts, where

96 of the 110 districts fall. While the family income differences among the

3 groups of districts are small, they may be even more significant if categories

are weighted by the number of districts in each. At the very least, the study

does not support the affirmative correlation of poor school districts and poor

people stated by the court and the affiant; this is, however, the study the

court relied upon, and it is apparently the only study which purports to show

such correlation.

68Brief for the Center for Educational Policy Research and the Center for

Law and Education as Amici Curiae at 3 n.l.

6»Id. 6 n.5.

— 35—

would be those pool’ families who live in rich districts.

Not only do they have a resource advantage over those

who live in poor districts, but also, they get more school

for fewer tax dollars than do their more wealthy neigh

bors in the rich districts. The relative advantage of

the poor in rich districts is further increased by the

very factors that arguably are the unique disadvantage

of the poor in poor districts—their lack of mobility

and private school alternatives. As with the wealthy

in poor districts, the wealthy in rich districts are not

as dependent on their district’s public schools as their

less affluent neighbors and thus not as benefited by

living in a rich district under the present system.

Finally, to focus on aiding the poor who live in poor

districts would probably require greater relief than

that offered by Serrano and the subsequent cases. Un

der this analysis, the poor in districts that undervalue

education under such equal wealth alternatives as dis

trict power equalizing would be just as disadvantaged

as the poor who live in poor districts today. Their im

mobility and lack of private school alternatives would

still uniquely disadvantage them as compared to the

wealthy inhabitants of the same districts, and the poor

in districts with greater school expenditures. A focus

on the poor in poor districts would, therefore, require

equalization of expenditures to avoid the hypothesized

legal wrong.

Another complication in applying a district wealth

classification theory is that any correlation that does

exist between poor school districts and poor people

36—

may vary from state to state. Also, it is quite possible

that there is a greater correlation between the rural

poor and poor school districts than there is between

the urban poor and poor school districts. I f this cor

relation is necessary to the legal analysis, the legiti

macy of the Serrano result might very well vary from

state to state. A decision by the United States Supreme

Court, however, attempting to differentiate among the

states, would be entirely inappropriate. It would be

most unwise to have basically similar state systems

held invalid or valid depending on where the state’s

poor lived, or more accurately, depending on judges’

views of the difficult statistical analysis demonstrating

a correlation between poor people and poor school dis

tricts.

A related failure to demonstrate a relationship be

tween blacks or other racial minorities and poor dis

tricts is particularly disappointing to proponents of

judicial action for whom the presence of such correla

tion would have significant legal effects.70 One report

notes that in California, over half the minority pupils

reside in districts with above average assessed wealth

per pupil.71

™$ee, e.g., Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th Cir. 1971), in

which statistical evidence of discriminatory distribution of municipal services

along racial grounds triggered a “ compelling state interest” test.

^ P rivate W e a l t h an d P ublic E d u c a tio n , supra note 22, at 356-57 n.47.

The complaint in Serrano alleged that “ [a] disproportionate number of

school children who are black children, children with Spanish surnames, chil-

dren. belonging to other minority groups reside in school districts in which a

relatively inferior educational opportunity is provided.” 5 Cal. 3d at 590 n.l.

487 P.2d at 1245 n.l, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 605 n.l. Other than quoting this al

legation as part of the complaint, however, the California court did not rely

on it.

Hie affidavit relied on by the court in Rodriguez, 337 F. Supp. at 282

The absence of a correlation between poor or racial

minorities and poor districts may be attributable to,

among other factors, the failure of the property tax

as a measure of a man’s actual wealth. Most signifi

cantly, however, the reason for the absence of correla

tion is the location of industrial and commercial pro

perty, the presence of w h i c h increases a district’s

wealth by increasing its tax base, without a necessary

increase in school population.

These facts raise a basic question of the effect of

Serrano and its progeny. While the case has been hailed

on theoretical egalitarian grounds, many of its pro

ponents are more concerned with the practical prob

lem of getting more money for urban education. While

some major cities with high concentrations of poor

people are financially poor school districts, others, such

as New York, San Francisco, and Philadelphia, have

relatively high tax bases as compared to their respec

tive state averages.72 * They also spend more per pupil

than their respective state averages. Therefore, if cur