Order

Public Court Documents

October 31, 1969

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Order, 1969. 1c504fea-d067-f011-bec2-6045bdd81421. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ef273d84-a5a3-4957-b698-8eb82dab676b/order. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

® Qe

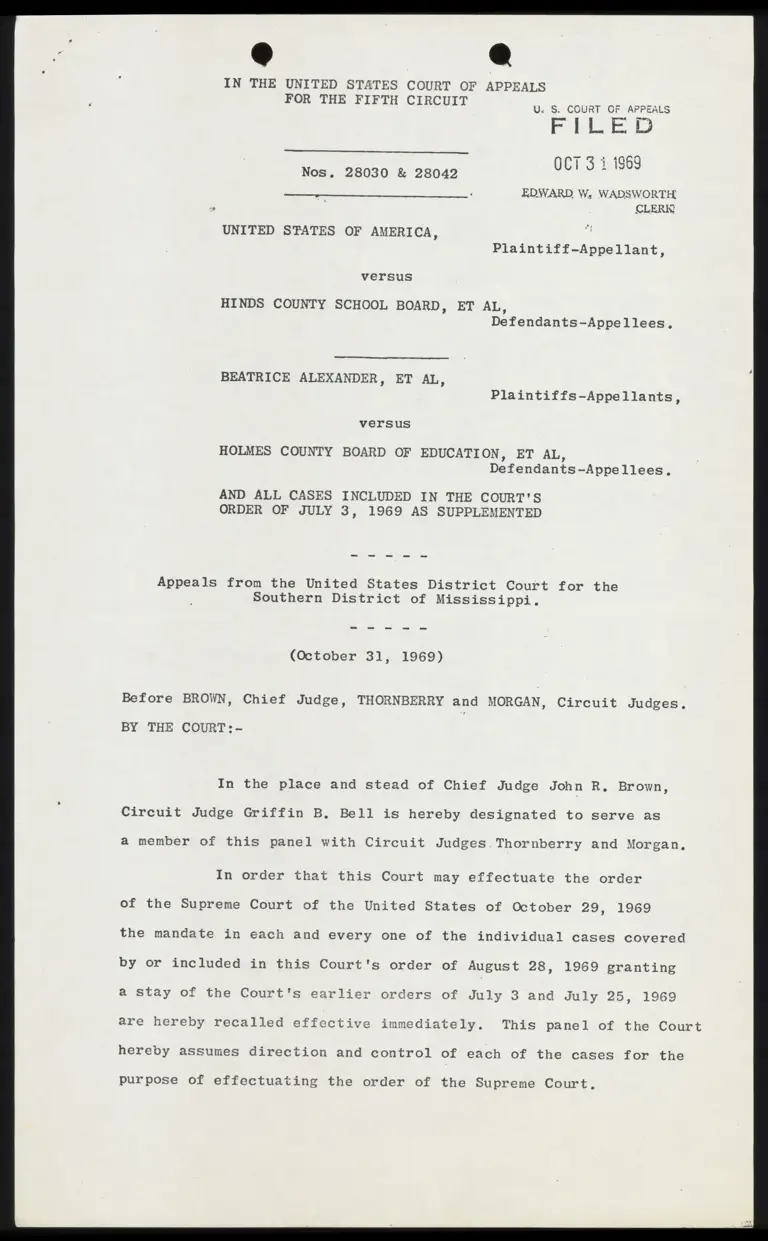

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT U. S. COURT CF APPEALS

FILLES

0CT 31 1968

EDWARD, W. WADSWORTH

CLERK]

Nos. 28030 & 28042

-

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

versus

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees.

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, ET AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees.

AND ALL CASES INCLUDED IN THE COURT'S

ORDER OF JULY 3, 1969 AS SUPPLEMENTED

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi.

(October 31, 1969)

Before BROWN, Chief Judge, THORNBERRY and MORGAN, Circuit Judges.

BY THE COURT:-~

In the place and stead of Chief Judge John R, Brown,

Circuit Judge Griffin B. Bell is hereby designated to serve as

a member of this panel with Circuit Judges. Thornberry and Morgan,

In order that this Court may effectuate the order

of the Supreme Court of the United States of October 29, 1969

the mandate in each and every one of the individual cases covered

by or included in this Court's order of August 28, 1969 granting

a stay of the Court's earlier orders of July 3 and July 25, 1969

are hereby recalled effective immediately. This panel of the Court

hereby assumes direction and control of each of the cases for the y

purpose of effectuating the order of the Supreme Court.

Appellants, Appellees and the United States of

America, as amicus or intervenors, shall file with the Clerk

of this Court on or before the 5th day of November, 1969, their

recommended and proposed orders which will properly effectuate

and implement the opinion and decree of the Supreme Court of the

United States rendered on October 29, 1969 in the above named

cases.