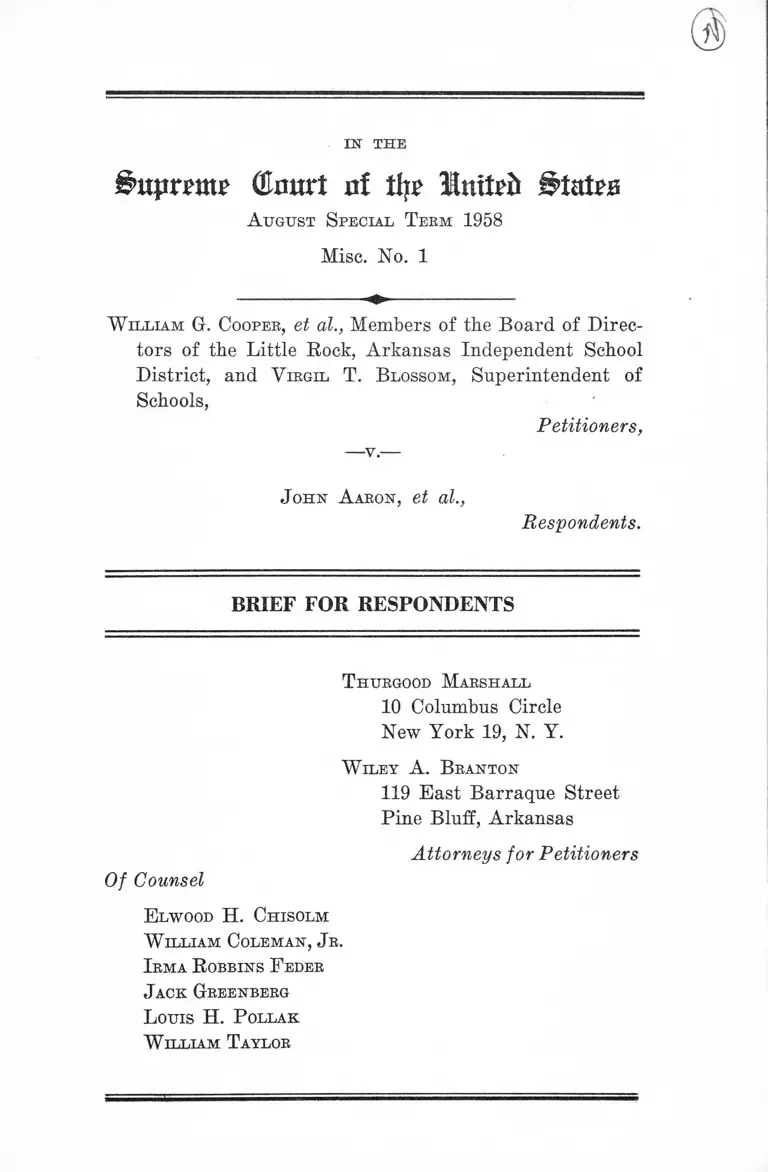

Cooper v. Aaron Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cooper v. Aaron Brief for Respondents, 1958. db457f48-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ef34b47e-e1f1-419a-80cf-57d092436e37/cooper-v-aaron-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN TH E

Bnptrnt (Slantt at tty Imteft §>tatPB

A ugust Special T eem 1958

Misc. No. 1

W illiam G-. Cooper, et al., Members of the Board of Direc

tors of the Little Rock, Arkansas Independent School

District, and V iegil T. Blossom, Superintendent of

Schools,

Petitioners,

-v -

J ohn A aron, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

T hubgood Maeshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

W iley A. B ranton

119 East Barraque Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Attorneys for Petitioners

Of Counsel

E lwood H. Chisolm

W illiam Coleman, J e.

Iema R obbins F eder

J ack Greenberg

L ouis H. P ollak

W illiam Tayloe

I N D E X

PAGE

Preliminary Statement .................................................... 1

Questions Presented ........................................................ 2

Summary of Argument.................................................... 3

Argument ...... 4

I—Overt public resistance including mob protests

is not sufficient cause to nullify federal court

orders requiring gradual desegregation of pub

lic schools ................................................................ 5

II—Any suspension of petitioners’ original plan of

gradual desegregation would subvert rather than

preserve the fundamental objective of public

education ................................................................ 8

Conclusion ................................................................................ 12

T a b l e of C a s e s :

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 249 F. 2d 462 (4th Cir., 1957) ...................... 7

Beatty v. Citibanks, L. R. 9 Q. B. Div. 314, 51 L. J.

Mag. Cas. N. S., 117, 47 L. T. N. S. 194, 31 Week

Eep. 275, 15 Cox, C. C. 138, 46 J. P. 789 .............. 7

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954),

349 U. S. 294 (1955) .............................................4, 5, 7, 8

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 .......................... 5

City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F. 2d 859 (5th Cir.

1950), cert, denied 341 U. S. 940 ............................. 6

11

PAGE

Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 ......................................... 6

Faubus v. United States, 254 F. 2d 797 (8th Cir., 1958) 11

Hoxie School Dist. No. 46 of Lawrence Co., Ark. v.

Brewer, 137 F. Snpp. 364 (E. D. Ark. 1956), aff’d

Brewer v. Hoxie School Dist. No. 46, 238 F. 2d 91

(8th Cir., 1956) ............................................................2,11

Jackson v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir., 1956), cert,

denied 352 U. S. 925 .................................................... 7

Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d 92 (6th Cir., 1957) .......2,11

Mitchell v. Pollack, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1038 (D. C.

Ky., 1956) ...................... 7

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U. S. 8 6 .................. ................... 6

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156

(5th Cir., 1957), cert, denied 354 U. S. 921.............. 7

Pugsley y. Sellmeyer, 158 Ark. 247, 250 S. W. 538

(1923) ............................................................................. 10

School Board of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen, 240 F. 2d

59 (4th Cir., 1956), cert, denied 353 U. S. 910........... 7

Strutwear Knitting Co. v. Olson, 13 F. Supp. 384

(D. Minn. 1936) ............................................................ 6

Thomason v. Cooper, 254 F. 2d 808 (8th Cir., 1958) .. 11

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U. S. 624 ................. 9

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U. S.

579 6

I l l

Other A uthorities:

page

Cremin, Lawrence A. and Borrowman, Merle L., Pub

lic Schools In Our Democracy 88-102, 204-216

(1956) ........................................................... 10

Grieder, Calvin and Eosenstengel, William E., Public

School Administration 89-98 (1954) ............................ 10

Griffiths, Daniel E., Human Relations in School Ad

ministration 14-20, 152-161, 240, 307-309 (1956) .... 10

Hobbes, De Cive I, 12 (1651) ..................................... 6

Koopman, G. Robert; Miel, Alice; and Misner, Paul

J., Democracy in School Administration 225-276

(1943) .......................................................... 10

Newlon, Jessie H., Education for Democracy in Our

Time 168-169 (1939) .................................................. 10

Richards, Edward A., Ed., Midcentury White House

Conference on Children and Youth, Washington,

D. C. 1950, passim (1951) ............................................. 10

IN TH E

i ’nprrnti' QInitrt ai liir Mnitefc t̂atrii

A ugust Special T eem 1958

Misc. No. 1

W illiam G. Coopee, et al., Members of the Board of Direc

tors of the Little Rock, Arkansas Independent School

District, and V ibgil T. B lossom, Superintendent of

Schools,

Petitioners,

J ohn A aron, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Preliminary Statement

Briefs for petitioners and respondents being filed simul

taneously we have not seen the “ Statement of the Case”

in petitioners’ brief. We assume that such statement will

be accurate and adequate. In any event, the Opinion of the

Court of Appeals adequately sets forth the facts. We,

however, call this Court’s attention to one paragraph of

the Opinion of the Court of Appeals which states as fol

lows :

It is not the province of this Court in this proceed

ing to advise the Board as to the means of implementing

integration in the Little Rock Schools. We are directly

concerned only with the legality of the order under

2

review. We do observe, however, that at no time did

the Board seek injunctive relief against those who

opposed by unlawful acts the lawful integration plan,

which action apparently proved successful in the Clin

ton, Tennessee and Hoxie, Arkansas situations. See

Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d 92 (6 Cir. 1957), certi

orari denied 355 U. S. 834, rehearing denied 355 U. S.

886; Hoxie School District v. Brewer (E. D. Ark.), 137

F. Supp. 364, aff’d Brewer v. Hoxie School District

(8 Cir. 1956), 238 F. 2d 91. The evidence also affords

some basis for belief that if more rigid and strict

disciplinary methods had been adopted and pursued in

dealing with those comparatively few students who

were ring leaders in the trouble making, much of the

turmoil and strife within Central High School would

have been eliminated.

Questions Presented

The questions presented by the Petition for Certiorari

are:

(1) Whether a court of equity may postpone the enforce

ment of the respondents’ constitutional rights if the con

tinued enforcement thereof will result in an intolerable

situation and great disruption of the educational process to

the detriment of the public interest, the schools, and the

students including the respondents.

(2) Whether a school district has a duty and obligation,

by invoking extraordinary legal processes and otherwise,

to quell violence, disorder and organized resistance to

desegregation.

3

Summary of Argument

I

Neither overt public resistance, nor the possibility of it,

constitutes sufficient cause to nullify the orders of the

federal court directing petitioners to proceed with their

desegregation plan. This Court and other courts have con

sistently held that the preservation of public peace may

not be accomplished by interference with rights created by

the Federal Constitution.

Applying this familiar rule, this Court held in the School

Segregation Cases, that delay could not be predicated on

opposition to desegregation.

The sustension of this principle is all the more impera

tive where, as here, the forces at work to frustrate the

Constitution and the authority of the federal courts were

deliberately set in motion by the Governor of a state whose

school system is under mandate to achieve conformity with

the Constitution. Here one state agency, the School Board,

seeks to be relieved of its constitutional obligation by

pleading the force majeure brought to bear by another

facet of state power. To solve this problem by further

delaying the constitutional rights of respondents is unthink

able.

II

Hardship to petitioners is no excuse for abrogating the

Rule of Law, but even if it were, petitioners here cannot

validly claim it.

Petitioners had at their disposal and still have available

to them a legal remedy to prevent interference with the

performance of their constitutional duties.

4

There is no ground for a presumption that the authori

ties charged with the duty of enforcing the law will refuse

or be unable to perform this duty. In fact, the federal

government stands ready to perform this duty.

Even if it be claimed that tension will result which will

disturb the educational process, this is preferable to the

complete breakdown of education which will result from

teaching children that courts of law will bow to violence.

Argument

The decision of the Court of Appeals setting aside Judge

Lemley’s two and one-half years suspension of desegrega

tion was correct and should be sustained. Indeed, the

decision is so eminently sound, so clearly in harmony with

decisions of this Court and other federal courts, that the

questions presented by the Petition for Certiorari could

hardly even be characterized as substantial, were it not for

two factors:

First, the legal controversy over the obligation of the

Little Rock School Board to proceed with the desegregation

of Central High School, and other schools it manages, pur

suant to the original, and judicially approved, schedule

has now become a national test of the vitality of the prin

ciples enunciated in Brown v. Board of Education.

Second, the principal ground urged for overruling the

Court of Appeals’ decision is, in essence, that unless peti

tioners’ obligation to proceed with desegregation of the

Little Rock schools is suspended, ruffians with or without

support from state officials will resume their attempts

forcibly to block the execution of valid federal court orders.

Acquiescence in any such argument would subvert our

entire constitutional framework.

5

In short, this case involves not only vindication of the

constitutional rights declared in Brown, but indeed the

very survival of the Rule of Law. This case affords this

Court the opportunity to restate in unmistakable terms

both the urgency of proceeding with desegregation and the

supremacy of all constitutional rights over bigots—big

and small.

I

Overt public resistance including mob protests is not

sufficient cause to nullify federal court orders requiring

gradual desegregation of public schools.

The Petition for Certiorari herein filed seeks a reversal

of the decision of the Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit complaining:

The Circuit Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

agreed with the findings of the District Court that the

evidence is appalling but that great additional ex

pense, disruption of normal educational procedures,

tension and nervous collapse of the school personnel,

turmoil, bedlam, and chaos, are not a legal basis for

suspension of the plan since this would be an accession

to the demands of insurrectionists.

The Court of Appeals defined the issue in the case as:

“whether overt public resistance, including mob protest,

constitutes sufficient cause to nullify an order of the federal

court directing the Board to proceed with its integration

plan.” There has never been a suggestion that the rule is

other than as stated in Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60,

81:

It is urged that this proposed segregation will pro

mote the public peace by preventing race conflicts. De

sirable as this is, and important as is the preserva

6

tion of the public peace, this aim cannot be accom

plished by laws or ordinances which deny rights created

or protected by the Federal Constitution.

This principle has been reiterated in connection with

housing in the City of Birmingham which faced threats of

bombing because Negroes had purchased in a zone for

bidden to their race, City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185

F. 2d 859 (5th Cir. 1950), cert, denied 341 U. S. 940; in

reversing an order of the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Arkansas which dismissed a writ

of habeas corpus submitted by petitioners who had been

convicted of murder after a promise of “ leading officials”

to a lynch mob “ that, if the mob would refrain . . . they

would execute those found guilty in the form of law . . .

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U. S. 86, 88-89; in holding a gov

ernor forbidden to close a factory beset by rioters during

a strike, Strutwear Knitting Co. v. Olson, 13 F. Supp. 384

(D. Minn. 1936); in rejecting a claim of the government

that an American citizen of Japanese ancestry should have

been confined because “community hostility towards the

evacuees . . . has not disappeared,” Ex parte Endo, 323

U. S. 283, 297; and in holding, that notwithstanding a

national military emergency the constitutional rights of

steel producers could not be abridged by presidential

seizure. Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343

U. S. 579.

The imperviousness of the Buie of Law to arguments of

this sort is, after all, the underlying foundation of equal

justice under law. For if criminal defendants, home owners,

manufacturers, and others can be routed from their lawful

rights by a transient emergency, then we have returned to

a state prior to civil society, when there was the Hobbesian

state of “a war of all men against all men.” 1

1 Hobbes, De Cive I, 12 (1651).

7

This Court reaffirmed this premise of lawful government

in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 IT. S. 294, 300:

. . . it should go without saying that the vitality

of these constitutional principles cannot he allowed to

yield simply because of disagreement with them.

The federal judiciary (with the exception of Judge Lem-

ley whom the Court of Appeals reversed herein) has uni

formly followed this rule. See Jackson v. Rawdon, 235

F. 2d 93, 96 (5th Cir., 1956), cert, denied 352 U. S. 925;

School Board of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen, 240 F. 2d

59, 64 (4th Cir., 1956), cert, denied 353 U. S. 910; Orleans

Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156, 163-164 (5th

Cir., 1957), cert, denied 354 U. S. 921; Allen v. County

School Board of Prince Edward County, 249 F. 2d 462,

465 (4th Cir., 1957); Mitchell v. Pollack, 1 Race Eel. L.

Rep. 1038 (D. C. Ky., 1956).2

Therefore, the court below acted in consonance with all

lawful precedent and the best traditions of constitutional

government when it said:

The issue plainly comes down to the question of

whether overt public resistance, including mob pro

test, constitutes sufficient cause to nullify an order of

the federal court directing the Board to proceed with

its integration plan. We say the time has not yet come

in these United States when an order of a Federal

Court must he whittled away, watered down, or shame

fully withdrawn in the face of violent and unlawful

acts of individual citizens in opposition thereto.

2 A like rule was long ago recognized at English common law.

Beatty v. Gillhanks, L. R. 9 Q. B. Div. 314, 51 L. J. Mag. Cas. N. S.,

117, 47 L. T. N. S. 194, 31 Week Rep. 275, 15 Cox, C. C. 138, 46

J. P. 789.

8

II

Any suspension of petitioners’ original plan of gradual

desegregation would subvert rather than preserve the

fundamental objective of public education.

Throughout, petitioners’ argument is that education at

Central High School has been seriously impaired by law

less acts and the only solution is to revert to segregated

education as terms for peace with the lawless elements.

This plea is predicated on the argument that unless this

is done the total educational system at Central High School

will be seriously impaired or destroyed.

In the first Brown opinion this Court, however, made the

following declaration as to the position of education in our

modern day life, 347 U. S. 483, 493:

Today, education is perhaps the most important

function of state and local governments. Compulsory

school attendance laws and the great expenditures

for education both demonstrate our recognition of the

importance of education to our democratic society. It

is required in the performance of our most basic public

responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is

the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is a

principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural

values, in preparing him for later professional train

ing, and in helping him to adjust normally to his en

vironment.

Applying these principles to this case the Solicitor Gen

eral effectively disposed of the School Board’s contention

in his argument before the Court on August 28:

But when you talk about a deterioration of the edu

cational process in this school, it seems to me that one

9

of the things that all educators, certainly teachers,

would recognize, is that part of the educational process

is the attitude and conduct of the teachers, the per

sonnel of the school and the children themselves, and

part of their responsibility is to get across to these

teachers and for the teachers to get across to the chil

dren and those that are in the educational process, the

responsibility to enforce the laws; that we do live

in a country where we seek to maintain law and order

for the benefit of all the people, that the Constitution

and each of the rights that every citizen has under it,

is precious to every one of us, not just the rights that

I like and want for me, or that you like and want for

you, but all of them for every man and woman.

And that if you teach these children in Little Rock

or any other place in the country that as soon as you

get some force and violence, the courts of law in this

country are going to bow to it, they have no power

to deal with it, they will give way to it, will change

everything to accommodate that, I think that you de

stroy the whole educational process then and there.

Transcript of Argument, Aug. 28, 1958, p. 107.

This Court recognized as much in West Virginia State

Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624, in which

Justice Jackson wrote, at p. 637:

The Fourteenth Amendment, as now applied to the

States, protects the citizen against the State itself and

all of its creatures—Boards of Education not excepted.

These have, of course, important, delicate, and highly

discretionary functions, but none that they may not

perform within the limits of the Bill of Rights. That

they are educating the young for citizenship is reason

for scrupulous protection of Constitutional freedoms

of the individual, if we are not to strangle the free

1 0

mind at its source and teach youth to discount impor

tant principles of our government as mere platitudes.

Indeed, the Supreme Court of Arkansas has embraced

the same principle in a case in which it upheld the right

of a. school board to expel a student who had disobeyed

school regulations. While the board was upheld in its

enforcement of the particular regulation (concerning the

wearing of cosmetics) as reasonable, the language of the

court may properly be quoted here: “ It will be remembered

also that respect for constituted authority, and obedience

thereto, is an essential lesson to qualify one for the duties

of citizenship, and that the schoolroom is an appropriate

place to teach that lesson.” Pugsley v. Sellmeyer, 158 Ark.

247, 253, 250 S. W. 538, 539 (1923).3

Petitioners have a duty to accord respondents the equal pro

tection of law and should have sought injunctions against the

unlawful interferences with their performance thereof.

Petitioners, in the second of the questions presented in

their application for a writ of certiorari, ask whether they

have “a duty and obligation, by invoking extraordinary

legal processes and otherwise, to quell violence, disorder

and organized resistance to desegregation.”

Assuming the question is properly before the Court, it

cannot be gainsaid that petitioners could have invoked

3 See Cremin, Lawrence A. and Borrowman, Merle L., Public

Schools In Our Democracy 88-102, 204-216 (1956); Grieder, Calvin

and Rosenstengel, William E., Public School Administration 89-98

(1954) ; Griffiths, Daniel E., Human Relations in School Adminis

tration 14-20, 152-161, 240, 307-309 (1956); Koopman, G. Robert;

Miel, Alice; and Misner, Paul J., Democracy in School Administra

tion 225-276 (1943) ; Newlon, Jessie H., Education for Democracy

in Our Time 168-169 (1939); Richards, Edward A., Ed., Mid

century White House Conference on Children and Youth, Wash

ington, D. C. 1950, passim (1951).

1 1

“ extraordinary legal processes” to restrain interference

with the performance of their duty to accord respondents

nonsegregated public education. See Thomason v. Cooper,

254 F. 2d 808 (8th Cir., 1958); Faubus v. United States, 254

F. 2d 797 (8th Cir., 1958), pending on petition for a writ

of certiorari, No. 212, Oct. Term, 1958.

In addition, petitioners certainly had and have a duty

to preserve discipline and order in and about the premises.

And where, as here, third parties seek, to upset discipline

and order in attempts “ to deprive (among others) Negro

pupils of their constitutional rights, then it would seem

proper for [the School Board], so closely related as they

were to victims in this case, to bring a restraining suit.

They were officials of a great state and an omission by

them would, in effect, be a deprivation of rights under the

color of law.” Eoxie School Dist. No. 46 of Lawrence Co.,

Ark. v. Brewer, 137 F. Supp. 364, 367 (E. D. Ark. 1956),

affirmed Brewer v. Hoxie School Dist. No. 46, 238 F. 2d 91,

100 (8th Cir., 1956); Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d 92, 94

(6th Cir., 1957).

1 2

CONCLUSION

To prevent further disorder, petitioners have urged this

Court to approve Judge Lemley’s order, the purpose of

which is not to repress the lawless violence, but to give

the sanction of law to the motives which inspired it. The

answer can only be: not “ while this Court sits.”

Wherefore, respondents respectfully urge this Court to

affirm the judgment of the Court of Appeals, reinstate the

prior order of Judge Davies and order its mandate to

issue forthwith.

Respectfully submitted,

T hubgood Marshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

W iley A. B raxton

119 East Barraque Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Attorneys for Petitioners

Of Counsel

E lwood H. Chisolm

W illiam Coleman, Jb.

Ibma R obbins F edeb

J ack Greenbebg

L ouis H. P ollak

W illiam T aylob

38