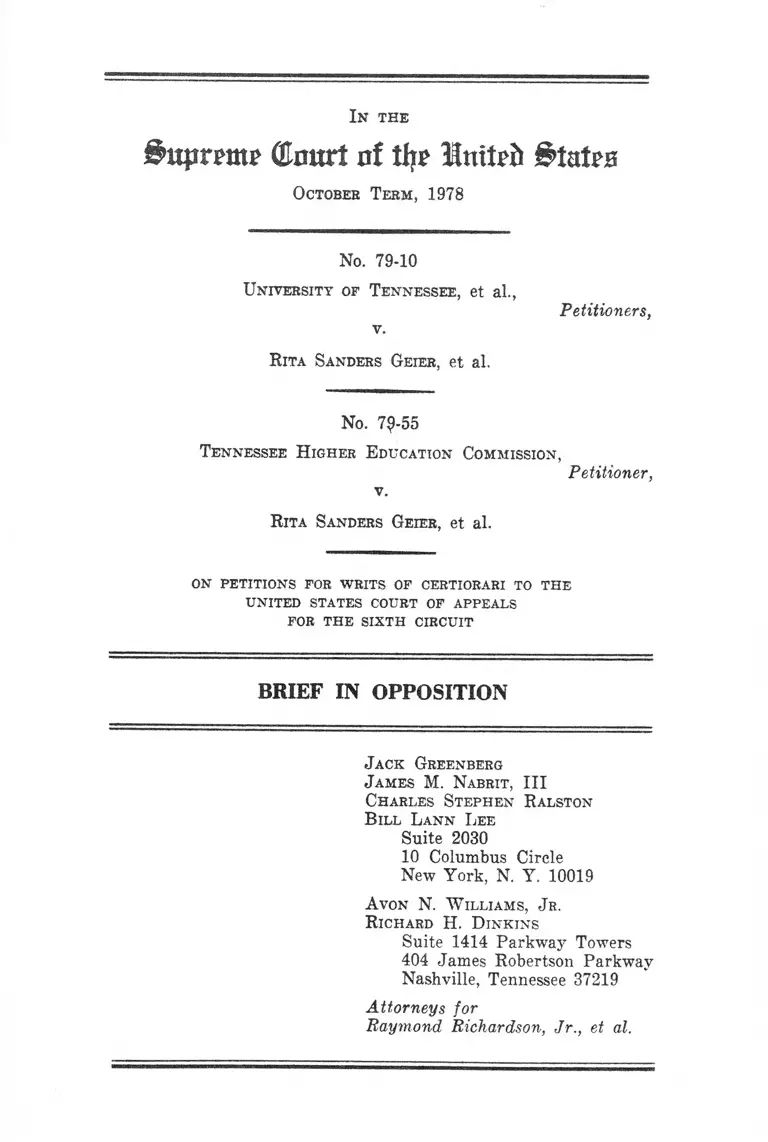

University of Tennessee v. Geier Brief in Opposition

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. University of Tennessee v. Geier Brief in Opposition, 1978. b6eb23f2-c79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ef36af11-00d9-4e51-a3d8-18f4a22c153f/university-of-tennessee-v-geier-brief-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

dnurt of IIjjo States

Octobee T eem, 1978

No. 79-10

University of T ennessee, et a l,

Petitioners,

v.

R ita Sandebs Geiee, et al.

No. 7?-55

Tennessee H igher Education Commission,

Petitioner,

v.

R ita Sanders Geiee, et al.

on petitions for writs of certiorari to the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

B ill L ann L ee

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

R ichard H. D inkins

Suite 1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

Attorneys for

Raymond Richardson, Jr., et al.

INDEX

Page

Questions Presented ......................................... 2

Statement of the Case ..................................... 2

A. District Court Proceedings ............. 2

B. Court of Appeals Decision .............. 6

Argument ...................... 8

Conclusion .......................................... 13

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Alabama State Teachers Assoc, v. Alabama

Public School and College Authority,

289 F.Supp. 784 (M.D. Ala. 1968),

a f f 'd per curiam, 393 U.S. 400 (1969).. 10

Blau v. Lehman, 368 U.S. 403 (1962) ............ 9

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick,

___ U.S.___ , 47 USLW 4924 (July 2,

1979), affirming, 583 F.2d 787

(6th Cir. 1978) ....................................... 9

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman,

___ U.S.____ , 47 USLW 4944 (July 2,

1979), affirming, 583 F.2d 243

(6th Cir. 1978) . ...................................... 10

Geier v. Blanton, 427 F.Supp. 644

(M.D. Tenn. 1977) ................................... 4

Geier v. Dunn, 337 F.Supp. 573

(M.D. Tenn. 1972) ................................... 4

Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) ................... 9

X1

Page

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) .. 11

Norris v. State Council of Higher

Education for Virginia, 327 F.Supp.

1318 (E.D. Va.), a f f 'd per curiam

sub nom Board of Visitors of the

College of William & Mary in

Virginia v. Norris, 404 U.S. 907

(1971) ...................................... 10

Sanders v. Ellington, 288 F.Supp. 937

(M.D. Tenn. 1968) ....................................... 4

United States v. Johnston, 268 U.S. 220

(1925) ........................................................... 8

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia,

407 U.S. 451 (1972) ..................................... 9

Statutes and Other Authorities:

Revised Criteria Specifying Ingredients

of Acceptable Plans to Desegregate

State Systems of Public Higher

Education, 43 Fed. Reg. 6658

(February 15, 1978) .............................. 12

Tenn. Code Ann. §49-3206 (1977) .................. 3

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1978

No. 79-10

UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, et a l . ,

Petitioners,

RITA SANDERS GEIER, et a l. ,

No. 79-55

TENNESSEE HIGHER EDUCATION COMMISSION,

Petitioner,

v.

RITA SANDERS GEIER, et a l. ,

ON PETITIONS FOR WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

Raymond Richardson, Jr. , et a l . , p la in t i f fs -

intervenors below, respectfully request that the

petitions for writs of certiorari to review the

opinion of the Sixth Circuit be denied.

2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the courts below properly found

that the St ate of Tennessee' s maintenance of Ten

nessee St ate University as a predominantly black

college in Nashville and the State's competitive

development of the Un iv e r s i t y o f Tennessee at

Nashville as a predominantly white public college

perpetuated an unconstitutional state created dual

system of public higher education?

2. Whether the remedial order of the courts

be low requiring the merger of Tennessee State Uni

versity and the University of Tennessee at Nash

v i l l e a fter a decade of trying to eliminate state

imposed segregation by other means was an abuse

of equitable discretion?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. District Court Proceedings

Th is act ion was f i led in 1968 by p la in tiffs

Rita Geier, et a l . , black students, parents, fac

ulty and citizens to desegregate the public higher

education system in the St ate of Tennessee. Subse

quent l y , the United States and Raymond Richardson,

Jr. , et al. , additional black students, parents,

facu lty and c i t izen s , intervened on behalf o f

3

p la in tif fs . Defendants include the Governor of

the State of Tennes see and the principal State

instrumentalities responsible for the operation

of public higher education, v i z ., the University

of Tennessee, the Tennessee Higher Education Com

mission and the State Board of Regents. The

principal issue has been the remedy required to

eliminate the formerly statutorily required dual

system perpetuated by the continued maintenance

in the c ity of Nashville, the State cap ita l, of

Tennessee State University (TSU) as the State's

h istoric public col lege for black persons, and

the competitive development of formerly a l l white

Univers ity of Tennes see at Nashville (UT-N) as a

predominantly white institution alongside pre

dominantly black TSU.

A ll Tennessee public colleges were formally

rac ia lly segregated pursuant to State constitu

tional provision and law until at least 1960. Pet.

App. 103a. TSU was established in 1912 and main

tained as the exclusive public in s t itu t ion of

higher education for black persons.—̂ The Uni-

\J To this day, Tennessee law provides that:

"The function of the Tennessee State University

at Nashville shall be to train negro students in

agriculture, home economics, trades and industry,

and to prepare teachers for the elementary and

high schools for negroes in the state." Tenn.

Code Ann. §49-3206 (1977).

v e r s i ty o f Tennessee, on the other hand, was

founded and maintained as a college solely for

white persons. UT-N was established in 1947 as a

non-degree granting night extension school in

Nashville solely for white students who were pro

h ib ited from attending nearby TSU. Pet. App.

103a-104a. In 1968, when the action was filed ,

TSU had an a l l black facu lty and student body

while UT-N remained essentially a l l white. Pet.

App. 4a-5a.

Over the course of eleven years of l i t iga t ion

the d is tr ic t court repeatedly found that "the dual

system of education created originally by law has

not been e f f e c t i v e l y dismantled." Sanders v.

Ellington, 288 F.Supp. 937, 940 (M.D. Tenn. 1968),

Pet. App. 4a-5a; Geier v. Dunn, 337 F.Supp. 373,

576 (M.D.Tenn. 1972), Pet. App. 19a; Geier v.

Blanton, 427 F.Supp. 644, 651-657 (M.D.Tenn.1977),

Pet. App. 52a-66a. The d is tr ic t court in i t ia l ly

declined to preliminarily enjoin the expansion of

UT-N. (then a small non-degree granting night

school) in 1968 because "[t jhere is nothing in the

record to indicate that the University of Tennes

see has any intention to make the Nashville Center

a [competitive) degree-granting day institution,"

Pet. App. 7a. However, defendants were repeatedly

ordered to develop a workable and e ffect ive plan

o f desegregation fo r the e lim ination of TSU' s

- 4 -

5

status as an identifiable black institution, Pet.

App. 9a-12a, 29a-32a, 41a-66a, 105a-114a. These

orders went unheeded, and the State expanded UT-N

into a degree-granting predominantly white in s t i

tution with classes beginning in the late a fter

noon, while TSU stagnated and remained overwhelm

ingly black. Id . Finally, in 1977, the d istr ict

court concluded that, " [t ]h e Court now finds that

the existence and expans ion of predominantly white

UT-N alongside the traditionally black TSU have

fostered competion for white students and thus

have impeded the dismantling of the dual system",

Pet. App. 54a. The court made specific findings

that the two schools were competitive institutions

offering duplicative courses, that UT-N's unres

trained growth prevented TSU from attracting white

students, and that the State' s various jo int, co

operative and exclusive programs between the two

schools had fa iled to result in substantial de

segregation of the dual system in Nashville. Pet.

App. 54a-66a, 105a-114a.

On the basis of 20 days o f t r i a l (and the

unanimous opinion of a l l the expert witnesses for

the parties ), the court concluded that "at this

time the only reasonable alternative is the merger

of TSU and UT-N into a single institution," and

ordered merger no later than July 1980 under the

State Board of Regents, the defendant governing

6

board of TSU. Pet. App. 67a, 114a.—̂ The State

Board of Regents f i l e d a plan o f merger which

provides "a comprehensive framework for imple

mentation of merger," including joint TSU-UT-N

implementation committees and subcommittees, time—

tables, and fu l1 implementation of merger in July-

August 1979. Pet. App. 116a-117a. The plan,

which expressly provides that UT-N's continuing

education and evening programs are to continue at

its downtown campus as part of TSU, was accepted

by the d istr ict court. Pet. App. 117a.

B. Court of Appeals Decision

Two of the State defendants, the University

of Tennessee and the Tennessee Higher Education

Commission, appealed. On April 13, 1979, a major

ity of the court of appeals, Judges Lively and

Peck, affirmed in a lengthy and comprehensive

2/ Merger was sought by a l l the parties plain

t i f f and TSU. Pet. App. 64a, 110a, 112a. Merger

was opposed by defendants University of Tennessee

and Tennessee Higher Educat ion Commission, a l

though in 1972 the Commission had reported that

"a merger of Tennessee State and U.T Nashville

does not appear to be fea s ib le at the present

time, although this may be necessary at some time

in the future to complete the desegregation pro

cess and to eliminate duplication and overlapping

of programs." Pet. App. 66a, 110a.

opinion. Pet. App. 102a. Judge Engel concurred

in the affirmance of the finding of a clear under

lying constitutional violation arising from the

State's failure to dismantle the dual system in

Nashville, but dissented on the particular remedy

ordered. Pet. App. 132a-134a. Judge Engel would

have vacated the judgment and remanded for further

proceedings specifica lly for "the entry of appro

priate injunctive r e l i e f to confine UT-N to those

courses and activ it ies which were offered prior to

the exp ansi on in 1969" or " [ s ]hould UT-N not be

satisfied with this, there remains available to i t

the opportunity to enter into [a voluntary merger]

agreement with TSU such as that which is now in

e ffec t in Memphis between UT and Memphis State

University." Pet. App. 142a-143a.

3/On July 1, 1979 TSU and UT-N were merged.—

Petitions for certiorari have been f i led by

defendants University of Tennessee (No. 79-10) and

Tennessee Higher Education Commission (No. 79-55).

Ne ither defendant Governor nor defendant State

Board of Regents have sought review.

3/ On June 18, 1979 the fu ll Court denied appli

cations for a stay of the merger f i led by peti

tioners University and Higher Education Commis

sion. Motions to stay the merger previously had

been considered and denied twice by the d istr ict

court and twice by the court of appeals.

8

ARGUMENT

1. The petitions request the Court to re

view evidence and discuss specific facts, see,

United States v. Johnston, 268U.S.220, 227(1925).

Petitioner 's argument with the courts below is

that "the mere existence of a predominantly black

institution of higher education" is insufficient

proof of discrimination. UT Pet. 17, THEC Pet.

19. The court of appeals, however, specifica lly

rejected this characterization of the factual re

cord: "This is not an accurate statement of the

d istr ic t court's holding . . . It was the failure

of the defendants to dismantle a statewide dual

system, the 'heart' of which was an all-black TSU,

which was found to be a continuing constitutional

v io la tion ." Pet. App. 118a, see also, 133a-134a.

The related factual claim that the University of

Tennessee played no role in the maintenance of

Tennessee State University as a predominantly

black institution, UT Pet. 27, THEC Pet. 22, was

also specifica lly rejected by the court of appeals

because " [ t]he d istr ict court found that acts of

the UT Board in expanding the program and size of

UT-N impede desegregation of TSU and thus the dis

mantling of Tennessee's dual system of public

higher education." Pet. App. 128a.

9

These factual contentions which two courts

be low have rejected are neither meritorious nor

appropriate for certiorari. See, e .g . , Blau v.

Lehman, 368 U.S. 403 (1962). With respect to

v io la t io n , a l l four judges who considered the

merits below found facts supporting a finding of

constitutional violation. Two courts below found

that the factual record required a merger remedy;

the lone dissenter would have required either a

more drastic remedy, i . e , stripping UT-N o f a ll

its post-1968 expansion programs and activ it ies ,

or the same remedy, i . e . , providing UT-N with the

opportunity to voluntarily transfer its programs

to TSU. Pet. App. 142a-143a.

2. The le g a l standards applied by the

courts below are neither novel nor remarkable.

The actions of St ate de fendants in expanding UT-N

as a white alternative to TSU in the Nashville

area, and the ineffective e fforts taken to elim i

nate the prior dual system imposed by law were

measured against the affirmative duty of the State

to provide for e f f e c t i v e desegregat ion and to

desist from impeding the desegregation process.

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968);

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451, 460 (1972). These basic principles of school

de segregation law were just reaffirmed in Columbus

10

Board of Education v. Penick, ___ U.S. , 47 USLW

4924, 4926-4927 (July 2, 1979), affirming, 583

F .2d 787 (6th Cir. 1978), and Dayton Board of

Education v. Brinkman, ___ U.S. , 47 USLW 4944,

4947 (July 2, 1979), affirming, 583 F.2d 243 (6th

Cir. 1978).

Nor is there any authority for the claim that

the sum total of the State's obligation to dis

mantle a dual system in the f ie ld of public higher

education is merely to drop formal racial bars to

admission. UT Pet. 21, THEC Pet. 12. Indeed, i t

has long been recognized that the affirmative duty

to desegregate is as exacting in public higher

education, but that the means of eliminating dis

crimination are necessarily different when dealing

with d i f fe ren t leve ls o f education. Norris v.

State Counci1 o f Higher Education for Virginia,

327 F.Supp. 1318 (E.D. Va.), a f f 'd per curiam sub

nom Board of Visitors of the College of William &

Mary in Virginia v, Norris, 404 U.S. 907 (1971);

Alabama State Teachers Assoc. v. Alabama Public

School and College A u thority , 289 F.Supp. 784

(M.D. Ala. 1968), a f f 'd per curiam, 393 U.S. 400

(1969). Compare Pet. App. 118a-123a. That the

long settled principle of the affirmative duty to

dismantle a dual system of public education is

applied in this case to higher education does not

in i t s e l f raise substantial questions. Id.

11

Certainly, the clear factual record in this

case of purposeful state act ion that inevitably

impeded the process of desegregation, in which a l1

four judge s be low concurred, does not press the

limits of any doctrine of l i a b i l i t y .

3. The remedy of merger was ordered by the

d is tr ic t court only after nearly a decade of l i t i

gation and repeated submission of unworkable dese

gregation plans by defendants. There was no abuse

of equitable discretion under the facts in this

case. Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 280-282

(1 9 7 7 ) . Nor is the merger remedy unique or unpre-

4/ The court of appeals held that:

"The scope of the d is tr ic t court's equitable

power is broad enough to encompass a merger

order under the facts of th is case. The

court 's experience taught that the only

meaningful resu lts were obtained when i t

ordered the graduat e program in educat ion

transferred exclusively to TSU. A merger of

the two institutions w il l involve the dis

tr ic t court in their day-to-day a ffa irs to a

much less pervasive degree than any attempt

by i t to divide and allocate a ll the various

programs to one school or the other. Merger

also intrudes less into the freedom of stu

dents to attend a co llege o f the ir choice

than any plan which might require compulsory

assignments to bring about a dismantling of

the dual system. The acknowledged d i f fe r

ences between higher education and education

at the primary and secondary levels appear to

(contd. )

12

cedented. As both the d is tr ic t court and court of

appeals found, the competition between preexisting

Memphis State University, a predominantly white

sister school of TSU, and an expanding University

of Tennessee fa c i l i t y in another Tennessee c ity,

Memphis, was resolved by merger of the two in s t i

tutions under Memphis State. Pet. App. 56a-58a,

126a, see also 142a-143a.—̂

There simply is no warrant to unravel a

remedy that has provided Nashville, Tennessee for

the f ir s t time with equal educational opportunity

in public higher education.

4/ (cont'd)

make such frequently used remedies as assign

ment and transportation of students to a par

ticular institution unworkable as well as un

desirable. "

Pet. App. 125a-126a.

5/ Guidelines o f the U.S. Department of Health,

Education and Welfare promulgated pursuant to

T it le VI of the C iv il Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C

§2000d, specifica lly approve "merging institutions

or branches thereof, particularly where institu

tions or campuses have the same or overlapping

service areas" as a desegregation device in public

higher education. Revised Criteria Specifying

Ingredients o f Acceptable Plans to Desegregate

State Systems of Public Higher Education, 43 Fed.

Reg. 6658, 6661 (February 15, 1978).

13 -

CONCLUSION

The petitions for writs of certiorari f i led

by the University of Tennessee and the Tennessee

Higher Educat ion Commission should be denied.

Respectfully submitted.

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

RICHARD H. DINKINS

Suite 1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, I I I

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BILL LANN LEE

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Raymond

Richardson, Jr. et a l .