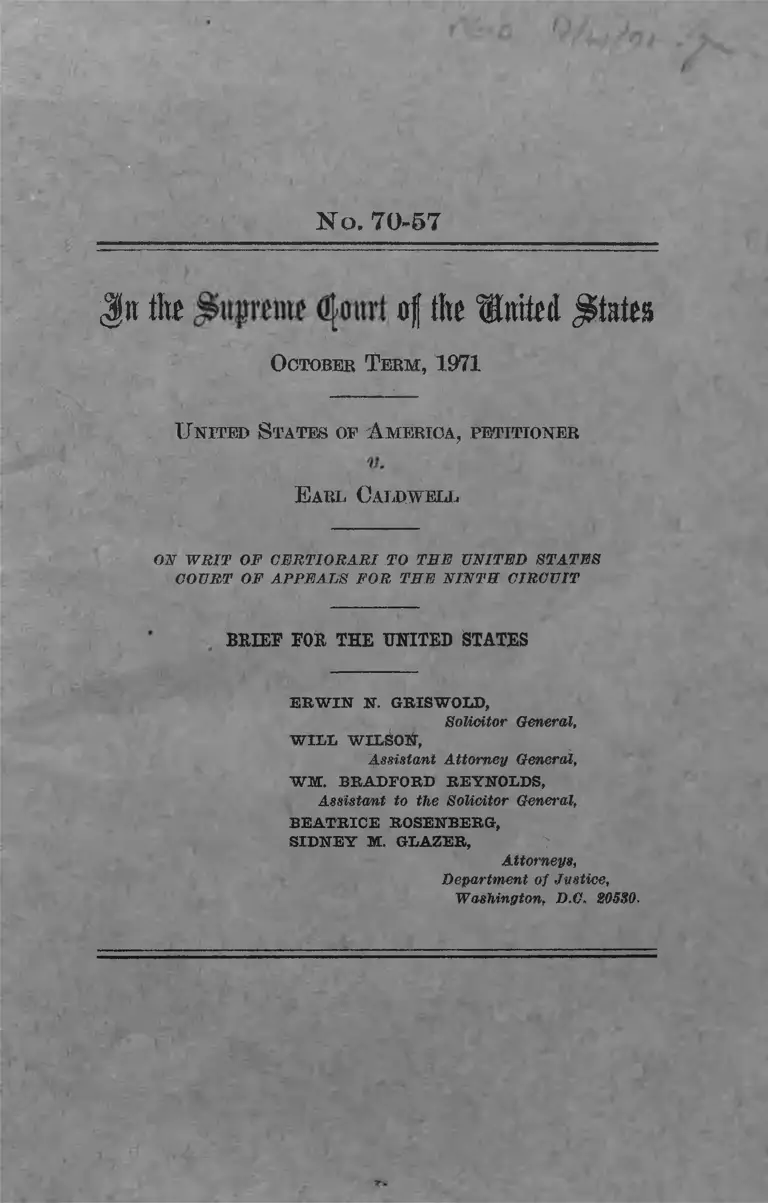

United States v. Caldwell Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

July 31, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Caldwell Brief for Petitioner, 1971. c5e1965d-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ef7e1356-b231-42c4-b82b-d720999ad9e2/united-states-v-caldwell-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

N o. 70-57

Jit to of to litod states

OOTOBEB I ’erm, 1971

U nited States OS’ A merica, petitioner

Earl Caldweej^

OW W R IT OF C m T lO R A R I TO TMB UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEARS FOR THE N IN TH CIRCUIT

BEIEl FOR THE UNITED STATES

EBWIN N. GEISWOM),

SoUoitor Qmeml,

WII/L W IlioN,

Assistant Attorney Cfmer<d,

WM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS,

Assistmt to the SoUoitor Qmeml,

BEATRICE ROSENBERG,

SIDNEY Ht. GLAZER, >

Attorneys,

Department of Justioe,

Washington, D.G. S0SSO.

I N D E X

Bags

Opinions below___________________________ 1

Jurisdiction______________________________ 1

Question presented________________________ 1

Constitutional provisions involved____________ 2

Statement_______________________________ 2

Summary of argument_____________________ 8

Argument:

I. Introduction______________________ 11

II. Requiring a newsman to appear before a

grand jury pursuant to a subpoena which

has been modified by court order to pro

tect confidential associations and private

communications does not violate the

freedom of the press guaranteed by the

Fh’st Amendment_________________ 16

A. The nature of the claimed privi

lege,_____________________ 16

B. The effect of the subpoena_____ 22

C. The proper balance___________ 34

D. The compelling need test______ 42

Conclusion___________.----------------------------- 48

Appendix------------------ 49

CITATIONS

Cases:

Alderman v. United States, 394 U.S. 165____ 5

American Communications Association v.

Douds, 339 U.S. 382__________________ 30

Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U.S. 500__ 26

A Quantity of Copies of Books v. Kansas, 378

U.S. 205___________________________ 26

O)

II

Oases—Continued

Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 page

U.S. 288___________________________ 1 1

Associated Press v. United States, 326 U.S. 1__ 17

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360___________ 26, 28

BarenhlattY. United States, 360 U.S. 109___ 30, 32, 40

Bates V. City of Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516____30, 32

Beckley Newspapers Corp. v. Hanks, 389 U.S.

81________________________________ 15

Blair v. United States, 250 U.S. 273_______ 35,

36, 37, 38, 43

Blau V. United States, 340 U.S. 332________ 39

Boyle V. Landry, 401 U.S. 77__________ __ 25, 29

Branzhurg v. Meigs, Franklin Cir. Ct., Ky,

decided January 22, 1971______________ 15

Brown Y. Walker, 161 U.S. 591___________ 37

Caldwell v. United States, C.A. 9, No. 25802,

decided May 12 , 1970________________ 6,12

Cameron v. Johnson, 390 U.S. 611_________ 22

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568._ 46

Coates V. City of Cincinnati, No. 117, October

Term 1970, decided June 1, 1971________22, 26

Cobbledick v. United States, 309 U.S. 323____ 44

Communist Party of the United States v. Sub

versive Activities Control Board, 367 U.S. 1__ 30

Connolly v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S.

385_______________________________ 23

Costello V. United States, 350 U.S. 359_ _ 10, 34, 35, 44

DeGregory v. Attorney General of New Hamp

shire, 383 U.S. 825___________________ 32

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353__________ 45

Dennis v. United States, 384 U.S. 855______ 36

DiBella v. United States, 369 U.S. 121______ 44

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479_______ 22,

24, 25, 26, 29, 31

Elfbrandt v. Russell, 384 U.S. 11__________ 31, 34

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51_______ 26

Ill

Cases—Continued

Garland v. Torre, 259 F, 2d 545, certiorari page

denied, 358 U.S. 910_________________ 12, 14

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation

Committee, 372 U.S. 539_______________30, 32

Goodfader’s Appeal, In re, 367 P. 2d 472_____13, 15

Goodman v. United States, 108 F. 2d 516_____ 35

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U.S. 233__ 15, 18

Hale V. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43______________35, 43

Hannah v. Larche, 363 U.S. 420__________ 37, 43

Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U.S. 167________ 22

Hendricks v. United States, 223 U.S. 178___ 43

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242__________ 23

Holt V. United States, 218 U.S. 245________ 44

Jenkins v. McKeithen, 395 U.S. 411______ 35

Kaplan v. United States, 234 F. 2d 345_____ 42

Katz V. United States, 389 U.S. 347________ 39

Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589__ 25,

27, 28

Kingsley Book, Inc. v. Brown, 354 U.S. 436__ 29

Kingsley International Pictures Corp. v. Regents

of University of New York, 360 U.S. 684___ 23

Konigsberg v. State Bar, 366 U.S. 36______ 30

Kunz V. New York, 340 U.S. 290__________ 26

Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 U.S. 301 __ 15, 30

LaRocca v. United States, 337 F. 2d 39_____ 43

Liveright v. Joint Committee, 279 F. Supp.

205_______________________________ 32

Louisiana ex rel. Gremillion v. NAACP, 366

U.S. 293____ 32

Lovell V. Griffin, 303 U.S. 444____________ 15

Mack, In re, 386 Pa. 251, 126 A. 2d 679,

certiorari denied, 352 U.S. 1002-------------- 15

Marchetti v. United States, 390 U.S. 39_____ 41

Marcus v. Search Warrant, 367 U.S. 717---- 28

McGrain v. Daiogherty, 273 U.S. 135------------ 40

IV

Oases—Oontinued

Minor v. United States, 396 U.S. 87_______ 41

Moore v. Ogilvie, 394 U.S. 814____________ 3

NAACP V. Alabama ex ret. Patterson, 357

U.S. 449________ _______________ 15,30,31

NAACP V. Button, 371 U.S. 415_____ 24, 26, 2l’, 29

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697__________ 15

New York Times y . Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254__ 15, 33

New York Times Company v. United States,

No. 1873, O.T. 1970, decided June 30,1971.. 15

People V. Dohrn, Grim. No. 69-3808, decided

May 20, 1970_____. . . _______________ 14

Piemonte v. United States, 367 U.S. 556_____ 42

Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company v. United

States, 360 U.S. 395------------------- 10, 35, 36, 42

Poe V. Ullman, 367 U.S, 497________._____ 1 1

Roviaro v. United States, 353 U.S. 53______ 14, 39

Samuels v. Mackell, 401 U.S. 66. _________ 45

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479___________30, 32

Shillitani v. United States, 384 U.S. 364____ 3

Smith V. California, 361 U.S. 147_______ 9, 23, 28

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513__________ 29

State V. Buchanan, 250 Ore. 244, 436 P. 2d

729, certiorari denied, 392 U.S. 905._____ 15

Staub V. City of Baxley, 355 U.S. 313______ 26

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359._____ 23

Sweezy y. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234___ 30,

31, 32, 33-34

Talley v. California, 362 U.S. 60__________ 30, 32

Taylor, In re, 193 A. 2d 181____________ 15

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88_________ 23

Times, Inc. y. Hill, 385 U.S. 374__________ 15

United States v. Amazon Industrial Corp., 55

F. 2d 254__________________________ 36

United States y. Bryan, 339 U.S. 323________ 37

United States y. Freed, No. 345, O.T. 1970,

decided April 5,1971_________________ 41

V

Oases—Continued

United States v. Johnson, 319 U.S. 503__ 34, 35, 36, 46

United States v. Procter & Gamble, 356 U.S.

677--------------------------------------- 10,34,36,42

United States v. Rohel, 389 U.S. 258___ 22, 26, 27, 31

United States v. Rose, 125 F. 2d 617_______ 35

United States v. Rumely, 345 U.S. 41_______ 40

United States v. Ryan, No. 758, decided May

24, 1971----------------------------------------- 12,44

United States v. Socony-Vacuum Oil Company,

310 U.S. 150________________________ 36

United States v. Stone, 429 F. 2d 138________ 37, 43

United States v. The Washington Post Co., No.

1885, O.T. 1970, decided June 30,1971____ 15

United States v. Thomas George, C.A. 6, No.

71-1067, decided June 14, 1971_________ 39

United States v. Tucker, 380 F. 2d 206_______ 14

United States v. Winter, 348 F. 2d 204, cer

tiorari denied, 382 U.S. 955____ 10, 37, 39, 42, 47

Walker v. City of Birmingham, 388 U.S.

307------------------------------------ 9,23,24,30,31

Whitehill v. Elkins, 389 U.S. 54__________ 31

Winters v. United States, 333 U.S. 507_____ 15, 23

Wisconsin v. Knops, Sup. Ct. Wise., State

No. 146, decided February 2,1971_______ 14

Wood V. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375_________ 35, 37, 46

Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37________ 22, 25, 29

Zwickler v. Koota, 389 U.S. 241__________ 25

Constitution, statutes and rule:

U.S. Constitution:

Bill of rights______________________ 15

First Amendment__________________

2, 9, 11, 12, 16, 21, 23, 26, 29, 30, 32-33, 38

39, 40, 45

Fifth Amendment__________ ____ 39 47

18 U.S.C. 871________________________ 3

50 U.S.C. (Supp. IV) 784(c)(1)(D)___ ^____ 26

VI

Constitution, statutes and rule—Continued p̂ge

Ala. Code Recompiled Tit. 7 §370 (1960)___ 13

Alaska Stat. §09.25.150 (1967, 1970 Cum.

Supp.)------------------------------------------- 13

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. §12-2237 (1969 Supp.) _ _ 13

Ark. Stat. Ann. §43-917 (1964)___________ 13

Cal. Evid. Code Ann. §1070 (West 1966)___ 13

Ind. Ann. Stat. §2-1733 (1968)___________ 13

Ky. Rev. Stat. §421.100 (1963)___________ 13

La. Rev. Stat. §45:1451-54 (1970 Cum.

Supp.)-------------------------------------------- 13

Md. Ann. Code Art. 35, §2 (1971)________ 13

Mich. Stat. Ann. §28.945(1) (1954)________ 13

Mont. Rev. Codes Ann. tit. 93, ch. 601-2

(1964)------------------------------------------- 13

Nev. Rev. Stat. §48.087 (1969)____________ 13

N.J. Stat. Ann. tit. 2A, ch. 84A, §2 1, 29

(Supp. 1969)________________________ 13

N.M. Stat. Ann. §20-1-12.1 (1953; 1967

Rev.)__----------------------------------------- 13

N.Y. Civ. Rights Law §79-h (McKinney,

1970)_____________________________ 14

Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §2739.12 (1953)______ 13

Pa. Stat. Ann tit. 68, §330 (1958, 1970 Cum.

Supp.)------------------------------------------- 14

Rule 6(e), F.R. Cr. p__________________ 35

Rule 6(g), F.R. Cr. P __________________ 2

Miscellaneous:

H.R. 7787, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963)____ 13

H.R. 8519, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963)____ 13

S. 1311, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess. (1970)______ 13

S. 1851, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963)_______ 13

Beaver, The Newsman’s Code, the Claim of

Privilege, and Everyman’s Right to Evidence,

47 Ore. L. Rev. 243 (1968)_____________ 28

A. Bickel, The Least Dangerous Branch, 149

(1962)-------------------------------------------- 31

VII

Miscellaneous—Continued

Bird and Mervin, The Newspaper and Society,

567 (1942)_________________________ 33

2 Chafee, Government & Mass Communications,

495_______________________________ 28

ColliQgs, Unconstitutional Uncertainty—An

Appraisal, 40 Cornel L. Q. 195 (1955)__ 24

Comment, Constitutional Protection for the

Newsman’s Work Product, 6 Harv. Civ,

R.-Civ. Lib. L. Rev. 119 (1970)_________ 13

Guest and Stanzler, The Constitutional Argu

ment for Newsmen Concealing Their Sources,

64 Nw. U. L. Rev. 18 (1960)________ 13,15, 28

1 Holdsworth, History of English Law (1927)

322----------------------------------------------- 35

Note, Reporters and Their Sources: The Con

stitutional Right to a Confidential Relation

ship, 80 Yale L. J. 317 (1970)__________ 17, 27

Note, The Chilling Effect in Constitutional Law,

69 Colum. L. Rev. 808________________ 31

Note, The First Amendment Overbreadth Doc

trine, 86 Harv. L. Rev. 844 (1970) __ 23, 24, 27, 31

Note, The Newsman’s Privilege: Protection of

Confidential Associations and Private Com

munications, 4 J. L. Ref. 85 (1970)_____ 13,17

Note, The Void-for-Vagueness Doctrine in the

Supreme Court, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67

(1960)-------------------------------------------- 23,24

Revised Draft of the Proposed Rules of

Evidence for the United States Courts and

Magistrates, Advisory Committee’s Note to

Proposed Rule 501___________________ 33

8 Wigmore, Evidence §2286 (McNaughton

rev. 1961)__________________________ 12

\n ih 0f ih

October Teem , 1971

17o. 70-57

U nited S tates of A merica, petitioner

V.

E arl Caldwell

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE N INTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOE THE UNITED STATES

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals (A. 114-130) is

reported at 434 E. 2d 1081, The opinion of the district

court (A. 91-93) is reported at 311 P. Supp. 358.

j u r is d ic t io n

The judgment of the court of appeals (A. 131) was

entered on November 16, 1970. The petition for a writ

of certiorari was filed on December 16, 1970; it was

granted on May 3, 1971 (A. 132). The jurisdiction of

this Court rests on 28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

q u e st io n p r e s e n t e d

Whether the First Amendment bars a grand jury

that is investigating possible crimes committed by

(1)

438- 569— 71-

members of an organization from compelling a news

paper reporter, who bas published articles about that

organization, to appear and testify solely about non-

confidential matters relating to the organization.

CONSTITUTIONAL PEOVISIONS INVOLVED

The First Amendment provides in pertinent part as

follows:

Congress shall make no law * * * abridg

ing the freedom of speech, or of the press * * *.

The Fifth Amendment provides in pertinent part

as follows:

hTo person shall be held to answer for a

capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on

a presentment or indictment of a Glrand Jury

STATEMENT

On June 5, 1970, the United States District Court

for the FTorthern District of California (A. 111-113)

adjudged respondent, a black reporter for The New

York Times, in civil contempt of court for refusing to

appear as a witness and testify before a federal grand

jury pursuant to a subpoena ad testificandum^ The

court of appeals reversed (A. 114-130).

̂The district court committed respondent to imprisonment

until such time as he might express an intent to testify or until

such time as the term of the grand jury expires, whichever is

earlier. It stayed its order pending final disposition on appeal.

Under Uule 6(g), F.E. Cr. P., no regular grand jiiry may serve

more than 18 months. The grand jury here was impanelled on

May 7, 1970, succeeding a prior grand jury (see p. 6, infra). Its

original term has been extended by court order to October 31,1971;

a further extension of one week, until ISTovember 6, 1971, may

be possible. After that date, however, “the grand jury ceases

to function, the rationale for civil contempt vanishes, and the

On December 3, 1969, an indictment was returned

against David Hilliard, Chief of Staff of the Black

Panther Party, charging him with making threats

against the life of the President of the United States,

in violation of 18 U.S.C. 871f During the preceding

month, Hilliard had stated publicly in a speech given

on November 15, 1969: “We will kill Richard Hixon”

(A. 65, 67). This threat was repeated in the Novem

ber 22, 1969, issue of the weekly periodical. The Black

Panther; it appeared again in the December 27, 1969,

issue, and was reiterated a third time in the Jan

uary 3, 1970, issue (A. 65). Moreover, numerous

public statements of a similar nature were reportedly

being made during the same period by members or

friends of the Black Panther Party in various parts

of the country (A. 66-67).

Coincident with this rash of threats against the life

of the President, an article by respondent about the

Black Panther Party was published on December 14,

1969 in The New York Times (A. 11-16). In that

article, respondent reported, among other things, on

a conversation he had with Hilliard and others at the

Panthers’ headquarters in Berkeley, California. At

contemnor has to be released.” ShUlitani v. United States, 384

U.S. 364, 371-372.

The question remains a live one, however, for the respond

ent can be summoned before another grand jury if the issue

here is resolved against him. Cf. Moore v. Ogilvie, 3§4 U.S. 814.

̂On May 4, 1971, the district court dismissed the indictment

against Hilliard after the government refused to disclose its logs

of an electronic surveillance undertaken to protect itself from

domestic subversion. An appeal from that dismissal is now

pending in the Ninth Circuit. United States v. Hilliard, C.A. 9,

No. 71-1882.

one point, he quoted Hilliard as having made the fol

lowing statement: “We advocate the very direct

overthrow of the Government by way of force and

violence. By picking up guns and moving against it be

cause we recognize it as being oppressive and in recog

nizing that we know that the only solution to it is

armed struggle” (A, 13). The article then continues

with these words: “In their role as the vanguard in a

revolutionary struggle the Panthers have picked up

guns” (ibid.). I t refers to two police raids on Panther

offices in other cities resulting in shooting incidents

and the discovery of caches of weapons, including

high-powered rifles (ibid.).

On February 2, 1970, respondent was served with

a subpoena duces tecum (A. 20), ordering him to ap

pear on February 4 and testify before the federal

grand jury in San Francisco, California; he was

ordered to bring with him notes and tape-recorded in

terviews covering the year 1969, which “reflect[ed]

statements made for publication” by Black Panther

officers and spokesmen “concerning the aims and

purposes * * * and the activities of said organiza

tion” and its members (ibid.). This subpoena, how

ever, was subsequently withdrawn voluntarily by the

government and is not involved in the instant action

(A. 91 note).

Thereafter, on March 16, 1970, the government

caused respondent to be served with a second grand

jury subpoena—this one a subpoena ad testificandum;

with no duces tecum clause (A. 21, 4). The next day,

he and The New York Times Company moved to

quash the subpoena on the ground that the First

Amendment relieved respondent, as a news reporter,

of any obligation to appear before the grand jury.

Alternatively, he requested a protective order prohibit

ing all grand jury interrogation “concerning any con

fidential interviews or information which he had

obtained exclusively by confidential interviews” (A.

4-5).^ This, he asserted, would include all unpublished

interviews with the Panthers; however, he indicated a

willingness to affirm “before the grand jury—or in any

other place the authenticity of qixotations attributed

to Black Panther sources in his published articles”

(A. 6).

Respondent’s position rested essentially on the claim

that his appearance alone at the secret proceedings

would be interpreted by the Black Panthers “ as a pos

sible disclosure of confidences and trusts” that would

cause the “Panthers and other dissident groups” to

refuse to speak to him and “destroy [his] effective

ness as a newspaperman” (A. 19).

The motion was heard upon affidavits and documen

tary evidence on April 3, 1970. On April 8, 1970, the

district court denied the motion to quash and directed

respondent to appear, subject to the following pro

visos ( A. 96) :

(1) That * * * Earl Caldwell * * * shall not

be required to reveal confidential associations,

̂He also contended that the court should conduct an in

quiry, pursuant to Alderman v. United States, 394 U.S. 165, to

determine whether the subpoena was the product of illegal

electronic surveillance (A. 4, 108-109). On this issue, the dis

trict court held (A. 93) that respondent had no standing to

raise such an objection “at this posture of the grand jury

investigation.” The court of appeals did not reach the question

and it is not now before this Court.

6

sources or information received, developed or

maintained by Mm as a professional journalist

in the course of Ms efforts to gather news for

dissemmation to the public through the press or

other news media.

(2) That specifically, without limiting para

graph (1 ), Mr. Caldwell shall not be required

to answer questions concerning statements made

to him or information given to him by members

of the Black Panther Party uMess such state

ments or information were given to him for

publication or public disclosure;

(3) That, to assure the effectuation of this

order, Mr. Caldwell shall be permitted to con

sult with his counsel at any time he wishes dur

ing the course of his appearance before the

grand jury;

The court further stated that it would entertain a

motion for modification of its order “ at any time

upon a showing by the Government of a compelling

and overriding national interest m requiring Mr. Cald

well’s testimony which cannot be served by any alter

native means * * *” (A. 96).^

At the end of the first week in May, the term of the

grand jury that had issued the March 16 subj)oena

expired, and a new grand jury was impanelled on

May 7, 1970. Respondent was served with a new sub-

^Eespondent appealed from this order on April 17, 1970; the

government moved to dismiss that appeal on the ground that

the order was interlocutory and unappealable, and that the

appeal was frivolous and would cause undue interruption of the

grand jury inquirj^ On May 12, 1970, the Ninth Circuit dis

missed the appeal without opinion. Caldwell v. United States,

C.A. 9, No. 25802. See n. 9, infra.

poena ad testificandum on May 22 to appear before

the newly impanelled grand jury, and the district

court denied a motion to quash, reissuing on June 4,

1970, its previous order limiting the scope of the grand

jury’s inquiry (A. 104-105).® On Jime 5, 1970, after

respondent persisted in his refusal to appear before

the grand jury, he was held in civil contempt ( A. 111-

113); ® he appealed to the Court of Appeals for the

Mnth Circuit.

In reversing, the court of appeals agreed with the

district court that the First Amendment accords news

paper reporters a qualified privilege to refuse to

answer questions in response to a grand jury subpo

ena. I t held, however, that because grand jury pro

ceedings are by nature secret, an order limiting the

scope of inquiry did not, ‘‘by itself, adequately pro

tect the First Amendment freedoms at stake in this

area” (A. 124). Finding that respondent had estab

lished a relationship of trust and confidence with the

Black Panthers which rested “ on contmuing reassur

ance” that his handling of news and information has

been discreet, the court reasoned as follows (A. 123) :

This reassurance disappears when the re

porter is called to testify behind closed doors.

The secrecy that surroimds Glrand Jury testi

mony necessarily introduces uncertainty in the

minds of those who fear a betrayal of their con

fidences. These uncertainties are compounded by

® Since the May 22 subpoena was, in substance, an extension

of the March 16 subpoena, we will for convenience refer here

after only to the earlier of the two.

The sentence to an indefinite term of imprisonment, not to

exceed the term of the grand jury then sitting, was stayed

pending appeal (see n. 1 supra).

8

the subtle nature of the journalist-informer re

lation. The demarcation between what is con

fidential and what is for publication is not

sharply drawn and often depends upon the par

ticular context or timing of the use of the

information. Militant groups might very under

standably fear that, under the pressure of

examination before a Grand Jury, the vdtness

may fail to protect their confidences with quite

the same sure judgment he invokes in the

normal course of his professional work.

Accordingly, it held that before respondent could be

ordered to appear ‘the Government must respond by

demonstrating a compelling need for the witness’

presence” (A. 125)."

SUMMABY OF ARGUMENT

This case does not raise the question whether a

newspaperman—like an attorney or a doctor or a

clergyman—can refuse to disclose information that he

has received as a matter of professional confidence.

Rather, the issue here is much narrower: whether a

reporter can refuse to appear and testify before a

grand jury about matters concededly nonconfidential

in nature on the ground that his appearance alone

could jeopardize confidential relationships and thereby

'Judge Jameson, District Judge for the District of Mon

tana, sitting by designation, while concurring in the result,

stated (A. 129) : “Appellant did not have any express con

stitutional right to decline to appear before the grand jury.

This is a duty required of all citizens. ITor has Congress

enacted legislation to accord any type of privilege to a news

reporter. In my opinion the order of the district court could

properly be affirmed, and this would accord with the customary

procedure of requiring a witness to seek a protective order

after appearing before the grand jury” (footnote omitted).

9

have a “cMlling effect” on the freedom of press guar

anteed by the First Amendment.

In safeguarding basic freedoms of speech or press,

this Court has often shifted its focus from the constitu

tional status of a particular complainant’s conduct to

the degree of chill being generated on others. But, this

approach has consistently been conditioned on the

need “to insulate * * * individuals from the 'chilling

effect’ upon exercise of First Amendment free

doms generated by vagueness, overbreadth and un

bridled discretion to limit their exercise” (Walker v.

City of Birmingham, 388 U.S. 307, 345 (Brennan, J.,

dissenting)).

The vices of unconstitutional vagueness or over

breadth are not present in this case. The grand jury

subpoena served on respondent has been modified by

court order to protect him against disclosures of con

fidential associations, sources and information; confi

dential matters relating to his relationship with the

Black Panthers need not be revealed; and he is per

mitted to interrupt his appearance at any time to confer

outside the jury room with his counsel. These precisely

defined guidelines are well within the “stricter standard

of permissible * * * Ytigu^eiiess” (Smithy. California,

361 U.S. 147, 151) that this Court has required to pro

tect against the chill on free speech or press caused by

government regulation that sv/eeps unnecessarily broad.

Hor do they trench on other First Amendment freedoms

by compelling injurious disclosures of confidential

associations.

In these circumstances, it is clear that respondent’s

challenge is not really to the subpoena power as such,

438- 569— 71 3

10

but rather to the fundamental nature of grand jury

proceedings in general—i.e., to the firmly established

policy of grand jury secrecy. That policy has long been

recognized as indispensable to the grand jury’s investi

gative process. I t is “older than our Hation itself”

{Pittshurgli Plate Glass Company v. United States,

360 U.S. 395, 399). Respondent should not be permit

ted to undermine the traditional investigative function

of that body on the ground that his appearance alone

(albeit fully protected) may cause the group under

investigation to stop communicating with him for fear

of a possible betrayal of confidences behind the closed

doors of the jury room. Such fear, in the circum

stances of this ease, is imaginary and insubstantial,

not real and appreciable. I t should not be allowed to

erode the “long-established policy that maintains the

secrecy of the grand jury proceedings” (United States

V. Proctor & Gamble, 356 U.S. 677, 681) and “denude

that ancient body of a substantial right of inquiry”

(United States v. Winter, 348 F. 2d 204, 208 (C.A. 2),

certiorari denied, 382 U.S. 955).

Uor is it appropriate to require the government, as

did the court below, to litigate the question whether

there exists a compelling need for attendance before

permitting enforcement of a grand jury subpoena to

any reporter working in a “sensitive” area. Such liti

gious interruptions of this historic investigative proc

ess have long been discouraged by this Court. The cir

cumstances presented here do not warrant intruding

on this “acquired * * * independence” (Costello v.

United States, 350 U.S. 359, 362) of grand juries by

requiring the government to make a satisfactory show-

11

ing in court of compelling need as a precondition to

calling respondent.

ARGUMENT

I. INTRODUCTION

This case presents only the narrow question stand

ing at the threshold of far broader and intrinsically

more difficult issues relating to the proper scope of a

news reporter’s claim of privilege. I t comes here in a

posture which permits disposition without requiring

this Court to decide the significant constitutional ques

tions now before it in Bransburg v. Hayes, Ho. 70-85,

and in In the Matter of Paul Pappas, No. 79-94.*'

Accordingly, we consider it neither appropriate (cf.

Poe v. Ullman, 367 U.S. 497, 503-504; Ashwander v.

Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U.S. 288, 345-348

(Brandeis, J., concimfing)), nor essential to the posi

tion we urge here, to include in this brief a broad

discussion of First Amendment rights and their rela

tionship to the ability of the news media to gather and

disseminate news.

Instead, as both our petition for certiorari and

respondent’s reply thereto indicate, the issue in this

case is narrow; the government did not appeal from

that part of the district court’s order that permits

respondent not to testify with respect to confidential

̂The issues as framed in those cases are whetlier a news

reporter can be compelled to disclose before a grand jury confi

dential associations (B ranzburg)or ab̂ rrt, matters seen and heard

by him on the express condition that he would divulge nothing

{Pafpas), without violating the First Amendment guarantee of

freedom of the press. We shall give the Court our views on those

questions in a brief amicus curiae, which we shall file in those cases.

matters.® This Court is thus called upon here to

decide only whether a reporter can refuse to appear

and testify before a grand jury about matters coii-

cededly non-eonfidential in nature on the ground that

his appearance alone could jeopardize confidential

relationships and thereby have a “ chilling elf'eet” on

the freedom of press guaranteed by the First

Amendment.

In urging that this question should be answered

negatively, we note |)Teliniinarily that the confidential

relationship between a newsman and his informant

can claim no protection at common law. 8 Wigmore,

Evidence § 2286 (McNaughton rev. 1961). Moreover,

courts have consistently declined the invitation to

create a common law privilege for newsmen by anal

ogizing the reporter-source relationship to traditional

relationships of attorney-client, doctor-patient and

priest-penitent. See, e.g., Garland v. Torre, 259 P. 2d

545, 550 (C.A. 2), certiorari denied, 358 U.S. 910;

® We do not consider the broader constitutional arguments

foreclosed to us in later proceedings by our decision not to seek

review of the district court order specifically protecting respond

ent from disclosure of any professional confidences unless the

government shows a compelling need therefor. In our view, that

was an unappealable order (cf. United States v. Ryan, Ao. 758,

October Terms, 1970, decided May 24, 1971; and see GaldiveU v.

United States, C.A. 9, No. 25802, decided May 12, 1970, where

the court of appeals refused to entertain respondent's eailier

appeal from that order); moreover, we felt that mandamus was

inappropriate at that time because it would call upon the court of

appeals to decide broad constitutional issues divorced from a con

crete setting. Consequently, we determined that the proper course

was to await respondent’s challenge, if any, to specific questions

during the grand jury proceeding, and I'aise any objections, consti

tutional or otherwise, that we might have to the order of the dis

trict court at that time.

13

In re Goodfader’s Appeal, 367 P. 2d 472 (Sup. Ct.

Hawaii).^" ISTor lias Congress been any more receptive

to the proponents of a newsman’s privilege. Although

federal legislation has been proposed on several occa

sions, no bill has ever emerged from the committee.”

On the other hand, some state legislatures have en

acted statutes protecting newsmen in varying degrees

against compulsory disclosure of confidential news

sources.” In so doing, these states have created a

10 For an illuminatiug discussion of tlie several factors which

have led courts to conclude that such analogies are imperfect,

see Note, The Newmnan-s Privilege: Protection of Coniidential

dissociations and Private Communications. 4 J.L. Reform 85,

89-93 (1970). Compare Guest and Stanzler, The Constitutional

Argument for Newsmen Concealing their Sources, 64 Nw. U. L.

Rev. 18, 26-27 (1969).

” See, e.g., S. 18.51, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963); H.R. 8519,

88tli Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) ; H.R. 7787, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1963) . There is presently pending before the Judiciary Com

mittee another bill which provides for the protection of ne\vs-

nien’s confidential sources and communications. See S. 1311,

92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1970). It has not yet been reported out

of committee.

” Such legislation has bewn passed in fifteen states: Ala. Code

Recompiled Tit. 7, § 370 (1960); Alaska Stat. § 09.25.150 (1967,

1970 Cum. Supp.); Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 12-2237 (1969

Supp.); Ark. Stat. Ann. § 43-917 (1964); Cal. Evicl. Code Ann.

§ 1070 (West 1966) ; Ind. Ann. Stat. § 2-1733 (1968) ; Ky. Rev.

Stat. §421.100 (1963); La. Rev. Stat. § 45:1451-54 (1970 Cum.

Supp.) ; Md. Ann. Code Art. 35, § 2 (1971) ; Mich. Stat. Ann. § 28.-

945 (1) (1954); Mont. Rev. Codes Ann. tit. 93. cli. 001-2

(1964) ; Nevada Rev. Stat. §48.087 (1969); N.J. Stat. Ann. tit.

2A, ch. 84A, §21, 29 (Supp. 1969) ; N.M. Stat. Ann. §20-1-12.1

(1953; 1967 Rev.) ; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §2739.12 (1953). For

a discussion of the differences in the scope of coverage under

these statutes, see Comment, Constitutional Protection for the

Newsman's Work Product, 6 Harv. Civ. R.-Civ. Lib. L. Rev.

119, 121-122 (1970).

More than a dozen other states liave considered and rejected

such legislatioii. See Guest and Stanzler, sv/pra, n. 10, at 20-21.

14

legislative privilege not unlike the common law priv

ilege of the government informer (see Boviaro v.

United States, 353 U.S. 53, 59), which permits the

recipient of information, i.e., the government, to

withhold the informant’s identity to protect ‘‘the

strong public interest in encouraging the free flow of

information to law enforcement officers.” United

States V. Tucker, 380 F, 2d 206, 213 (C.A. 2). Only

two states have passed statutes going ].)eyond the

perimeters of source identification; they have ex

tended the newsman’s privilege to confidential com

munications and, in one instance, to documents

received in confidence.^’’

Until the Islinth Circuit’s decision in the instant

case, the claim that a reporter’s privilege (though

withoiit common law roots and recognized by few

state legislatures) enjoys a constitutional basis in the

First Amendment freedom of the press has, with

one recent exception,“ been uniformly rejected by

federal and state courts. Garland v. Torre, supra;

See N.Y. Civ. Rights Law § 79-h (McKinney 1970) ; Pa.

Stat. Aim. tit. 28, § 330 (1958, 1970 Cum. Supp.). Only the

Pennsylvania statute has been construed to protect documents.

See In re Taylor^ 193 A. 2d 181 (Sup. Ct. Pa.)

A decision by the Cook County Circuit Court, Chicago, Illi

nois, which was rendered while the appeal in the instant case

was pending before the Ninth Circuit, upheld the claim of a

reporter’s privilege not to divulge confidential information on

First Amendment grounds. People v. Dohi'n, Crim. No. 69-3808,

decided May 20, 1970. And see Wisconsin v. Knops, Sup. Ct.

Wise., State No. 146, decided February 2, 1971, which was

announced after the court of appeals decision here and essen

tially agreed with the balancing approach of the Ninth Circuit

but reached a different result. The Enops opinion is reprinted

in our Supplemental Memorandum to the petition for cer

tiorari, No. 70-57.

15

In re Mach, 386 Pa. 251, 126 A. 2d 679, certiorari

denied, 352 U.S. 1002; In re Goodfader’s Appeal,

supra; In re Taylor, supra; State v. Buchanan, 250

Ore. 244, 436 P. 2d 729, certiorari denied, 392 IJ.S.

905; and see Branzhurg v. Meigs, Franklin Cir. Ct.,

Ky, decided January 22, 1971; In the Matter of

Paul Pappas, supra. Moreover, the major premise on

vfhich it is founded—that, in addition to the protected

freedoms to write (New York Times v. Sullivan, 376

U.S. 254; Times, Inc. v. Hill, 385 U.S. 374; Beckley

Newspapers Gorp. v. Hanks, 389 U.S. 81), to publish

(New York Times Company v. United States and

United States v. The Washington Post Company,

Uos. 1873 and 1885, October Term, 1970, decided

June 30, 1971), and to circulate (Winters v. United

States, 333 U.S. 507, 510; Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U.S.

444; Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U.S. 233;

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697, 713) news, there is

a constitutionally protected right of the press to

gather news—finds little support from statements of

the framers and backers of the Bill of Rights or

from prior decisions by this Court.’'

The opinion in Bramburg v. Meigs appears in the appendix

to the petition for a v/rit of certiorari in Bramburg v. Hayes.,

No. 70-85, at pp. 69-75.

See Guest and Stanzler, surra n. 10, at 30-31.

^^We do not read Lament v. Postmaster General., 381 IT.S.

301, holding that the First Amendment protects the right of

members of the public to receive “communist political propo-

ganda without first having to disclose the identities of the

recipients, as guaranteeing to news reporters a privilege to

receive (or gather) news without later having to disclose the

identities of the sources. Nor do we think the question was

reached in N A AO P v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357 U.S. 449,

462, where the Court held that Alabama could not by state

16

Nevertheless, even if the Court should hold in

Branzburg and Pappas that the First Amendment

freedom of the press covers neAvsgathering in general

and authorizes newsmen to refuse to disclose to grand

juries confidential associations and private communica

tions in particular {supra n. 8), such protection

would not warrant the relief respondent seeks in the

instant case. For, whatever may be the scope of a re

porter’s constitutional privilege, it does not justify his

refusal to appear before a grand jury to testify only

as to matters eoncededly nonconfidential in nature.

n. REQUIRING A NEWSMAN TO APPEAR BEFORE A GRAND

JURY PURSUANT TO A SUBPOENA W H ICH HAS BEEN

MODIFIED BY COURT ORDER TO PROTECT CONFIDENTIAL

ASSOCIATIONS AND PRIVATE COMMUNICATIONS DOES NOT

VIOLATE THE FREEDOM OP TPIB PRESS GUARANTEED BY

THE FIRST AMENDMENT

A . T H E N A T U E E OF T H E CLA IM ED PK IV ILEG E

We start with the fundamental proposition that

the reporter’s privilege, if one indeed exists, has as

its conceptual basis a common desire for anonymity

among those providing the news media with informa

tion. As a general matter, it is not that which is com

municated to the reporter that is intended to be with

held from publication, but only the identity of the

communicant. The affidavit filed in this action by news

correspondent Walter Cronkite makes the point with

customary precision (A. 52-53) :

3. In doing my work, I (and those who assist

me) depend constantly on information, ideas,

statute compel disclosure of membership in the local NAACP

chapter. See discussion infra at pp. A

1 /

leads and opinions received in confidence. Suefi

material is essential in digging out newsworthy

facts and, equally important, in assessing the

importance and analyzing the significance of

public events. Without such materials, I would

be able to do little more than broadcast press

releases and public statements.

4. The materia] that I obtain in privacy and

on a confidential basis is given to me on that

basis because 1115̂ news sources have learned to

trust me and can confide in me ivitJiout fear of

exposure. In nearly every case, their position,

perhaps their very job or career, would be in

jeopardy if this were not the case. * * * [Em

phasis added.]

To the extent, then, that there is a need for confiden

tiality in order to provide the public with “the widest

possible dissemination of information from diverse

and antagonistic sources” {Associated Press v. United

States, 326 U.S. 1, 20), it has been argued that the

reporter-informant privilege must at least protect

newsmen against involuntary disclosures of news

sources. See, e.g., Hote, Reporters and Their Sources:

The Constitutional Right to a Confidential Relation

ship, 80 Yale L. J. 317, 329-334 (1970).

The media, however, generally seem to view the

claimed professional privilege in a broader light.""

In urging more comprehensive protection of confiden

tial relationships, they emphasize, as does respondent

in the instant ease, that today there are many “dissi-

See generally, Comment, The Newsman's Privilege: Pro

tection of Confidential Associations and Private Comm,urdca-

tions, 4 J. of L. Ref. 85 (1970).

438- 569— 71----- 4

18

dent groups [which] feel oppressed by established in

stitutions, [and] they will not sjjeak to newspapermen

until a relationship of complete trust and confidence

has been developed” (A. 17). A reporter’s continued

access to such groups, it is urged, thus requires pro

tection against a forced betrayal of established confi

dences. Picking up a phrase used by this Court in

another context, such protection is claimed to be es

sential to the preservation of an “untrammeled press

as a vital source of * * * information.” Grosjean v.

American Press Go., 297 P.S. 233, 250.’®

Setting to one side the merits of this constitutional

argument {supra n. 8), it is significant that, with

the exception of respondent and one other journalist,’’®

every experienced reporter who discussed in the dis

trict court the scope of protection necessary to fore

stall possible erosion of such “tenuous and unstable”

relationships (A. 123), defined the outer perimeters

in terms of a professional privilege to Vvuthhold, in

addition to confidential sources, no more than the re-

In Grosjean, this Court held that a special license tax, ap

plicable only to newspapers with circulation in excess of 20,000

copies per week, was an unconstitutional restraint on both pub

lication and circulation. The separate question whether the news

media also had a First Amendment right to gather news was

not presented in that case.

'̂’Gerald Fraser, a black reporter for the New Yorh Times,

was of the opinion that the only professional privilege that

could provide adequate protection to confidential relationships

was one that granted him complete immunity from testifying

“about black activist groups” (A. 22), whether called before a

grand jury or a legislative committee, or asked to appear at

trial. That view apparently is not shared by respondent and

goes far beyond the position he takes in the instant case. See

discussion infra, p.

19

porter’s private notes or tiles, and other inforination

of a confidential nature/’ For example, national cor

respondent Eric Severeid, stated (A. 54): ^^Aiany

people feel free to discuss sensitive matters with me

in the knowledge that I can use it with no necessity

of attributing it to anyone. * * * Should a widespread

impression develop that my information or notes on

these conversations is subject to claim by government

investigators, this traditional relationship, essential

to my kind of work, would be most seriously jeopar

dized.” Similarly, staff correspondent Mike Wallace

emphasized (A. 55) that, if those with whom he had

established a confidential relationship “believed that I

might, voluntarilj^ or involuntarily, betray their trust

by disclosing my sources or their private communica

tions to me, my usefulness as a reporter would be

seriously diminished.” White House correspondent

Dan Rather put it in these terms (A. 60) : “The fear

that confidential discussions may be divulged, as a re

sult of grand jury subpoena, or otherwise, would cur

tail a repoiter’s ability to discover and analyze the

news.” Thus, he concluded (ibid.), newsmen should

not “be forced to disclose confidential conmiunications

and private sources.” And diplomatic correspondent

Marvin Kalb expressed the same view in yet another

way (A. 61) :

As the court below accurately pointed out (A. 118): “The

affidavits contained in this record required the conclusion of

the District Court that "coni'peUecl disclosure of information

received by a journalist within the scope of such confidential

relationships jeopardizes those relationships and thereby impairs

the journalist’s ability to gather, analyze, and publish the

news’ ” (emphasis added).

20

2. In the course of reporting on diplomatic af

fairs, I depend extensively on information which

comes to me in confidence from source^., whose

anonymity must be maintained. * * *

3. Privacy and discretion are the very essence

of my work as a reporter. Most of the informa

tion from which stories of diplomatic develop

ments emerge comes from private talks. Secrecy,

privacy, off-the-record, backgToimd, deep back

ground—these are the words which describe the

kind of work in the reporting of diplomatic

nuance and detail and the building of a. pattern

which ultimately emerges as a story.

4. I f my sources were to learn that their pri

vate talks with me could become public, or could

be subjected to outside scrutiny by court order,

they would stop talking to me, and the job of

diplomatic reporting could not be done.

What emerges from a full reading of the affidavits

of these and other reporters “ is a reaching out among

journalists for a reporter-source privilege—whether it

is to be created as a matter of constitutional right or

^^Eeporters Lowell (A. 44-45), Morgan (A. 46-47) and Yee

(A. 48-50) viewed the claimed privilege as protecting essen

tially confidential sources and production of files, notes or films.

Seporters Burnham (A. 43) and Lukas (A. 39-40) took a

broader view; they stated that the privilege should also pro

tect private communications or other information obtained by

reporters during confidential conversations. Reporters Johnson

(A. 24-25), Kifner (A. 26-27), Knight (A. 28-29), Proffitt (A.

30-31), and Turner (A. 34), in affidavits filed before the

issuance of the subjjoena that is the subject of the instant

litigation (see sujn-a, p. 4), objected principally to the

earlier subpoena duces tecum issued to respondent, calling for

production of notes, files and other documents; they felt this

material should be protected and that an appearance before a

grand jury in response to a subpoena of that nature would

destroy confidential relationships. Reporter Noble (A. 37-38)

21

results from legislative action —which will, protect at

least confidential sources, preferably also the news-

mcin’s confidential notes, and at most the private com

munications and other confidential information received

from an informant who wishes to remain anonymous.

Even if this Court should determine {supra n. 8)

that the most expansive of these alternatives is essen

tial to the preservation of the freedom of the press,

the subpoena involved in this case, as modified by the

district court’s order, does no violence to such a con

stitutional privilege. The judicial safeguards that have

been imposed here, we submit, adequately insulate re

spondent’s appearance from the charge that it gen

erates a “chilling effect” upon the exercise of First

Amendment rights.

expressed the same view. Eeporter Eipley (A. 32-33) related

simply that his own appearance and testimony before a legis

lative committee—without a limitation on the scope of inquiry

similar to the protective court order in this case—destroyed

many of his confidential relationships with “the radical stu

dent left." Finally, Eeporter Arnold (A. 41-42) discussed only

the nature of the reporter^ relationship with various groups,

pointing out that (A. 42), “[tjlie same forces are at work

whether the reporter is covering and writing about a radical

organization, a group of college students, narcotic users,

police, or Democratic or Eepublican politiciaus.” Without com

menting on the scope of protection necessary to a reporter to

maintain tire confidences he has developed, Arnold did point

out the relatively “tenuous and unstable” (A. 123) nature of

these relationships. “If it becomes known,” he stated (ibid.),

“that a reporter is loilling to tell a Go^rernment agency Avhat lie

has heard or learned or saw, his usefulness will be destroyed

because news sources will no longer speak to him” (emphasis

added). Eespondent is in no danger of jeopardizing his use

fulness on that score.

That question, of coni'se, is at the heart of the issues before

the Court in Bra/iishv.rg and Papjxis and will be treated in

our brief amicus curiae in tliose cases (supra n. 8).

22

B. T H E E F E E C T O F T H E SU B PO E N A

1. In SO far as the chill factor is relevant here, the

instant case requires preliminary reference to the two

lines of authority in this Court involving an applica

tion of the ‘‘chilling effect” concept as a basis for

judicial intervention. One, represented by Dombrow-

shi V. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479, Cameron v. Johnson, 390

U.S. 611, and most recently Younger v. Harris, 401

tr.S. 37, inter aha, recognizes a narrow exception to

this Court’s policy of abstention “ where a threatened

criminal prosecution, under an overly broad state

statute regulating expression, is fraught with “ im

ponderables and contingencies that themselves may

inhibit the full exercise of First Amendment free

doms” (380 U.S. at 486). The other, evidenced by

UnUed States v. Rohel, 389 U.S. 258, and most re

cently Coates V. City of Cincinnati, N̂o. 117, October

Term, 1970, decided dune 1 , 1971, inter alia, permits a

direct challenge to a statute purporting to regulate or

proscribe rights of si3eech, press, or association on the

ground that, although perhaps constitutional as applied

to the specific conduct in question, it has a potentially

deterrent impact on the rights of expression of others.

The element common to both lines of decision is that the

sweep of the underlying statutory provisions has a

“ ‘chilling effect’ upon exercise of First Amendment

That policy, grounded 03i principles of comity, is designed

to prevent federal courts generally from interfering- with im

minent or initiated state criminal pi-osecution, or adjudicating

“the constitutionality of state enactments fairly open to inter

pretation until the state courts have been afforded a reasonable

opportunity to pass upon them.” Harrhon v. N A AC P, 360 U.S.

167. 176; and see Younger v. Harris, supra, 401 U.S. at 43-45.

23

freedoms generated by vagueness, overbreadtli and

unbridled discretion to limit their exercise.” Walker v.

City of Birmingham, 388 U.S. 307, 344-345 (Brennan,

J., dissenting)

That concept, of course, has roots in early decisions

by this Court invalidating on due j)roeess gro\mds a

law “which either forbids or recpiires the doing of an

act in terins so vague that men of common intelligence

must necessarily guess at its meaning and differ as to

its application * * Connally v. General Construc

tion Co., 269 U.S. 385, 391."'’ Of more enduring signifi-

cajiee to the chilling effect doctrine, however, are cases

sustaining attacks on overbroad statutes because, as

drafted, they leave room for unconstitutional applica

tion under the First Amendment. See, e.g., Thornhill

V. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 ; Herndon v. Lotvry, 301 U.S.

242; Stromherg v. California, 283 U.S. 359, 360;

Kingsley In t’l Pictures Corp. v. Regents of Univ. of

N.Y., 360 U.S. 684, 694-695 (Frankfurter, J.,

conciiiTing).

In these latter decisions, as reflected in Smith v.

California, 361 U.S. 147, 151, there is the intimation

“that stricter standards of permissible statutory

vagueness may be applied to a statute having a poten

tially inhibiting effect on speech; a man may the less

be required to act at his peril here, because the free

dissemination of ideas may be the loser.” And see

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 ,509-510, 517-518.

Unlike the evil in the due process eases of lack of fair

See generally Note, The First AmeruLment Overhreadth

Doctrine, 83 Harv. L. Eev. 844 (1970).

See generally Note, The Yoid-for-Yagueness Doctrine, in the

Suprems Court, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960).

24

warning, the vice of unconstitutional vagueness in the

area of speech or press inheres in the threat that stat

utes which sweep unnecessarily broad “may throttle

protected conduct. They have a coercive effect since

rather than chance prosecution people will tend to

leave utterances unsaid even though they are protected

by the Constitution.” Collings, Unconstitutional Un

certainty—An A ^m isa l, 40 Cornell L. Q. 195, 219

(1955).^^

Judicial protection against such unconstitutional in

hibition derives support from the “chilling effect” doc

trine. I t permits courts to modify “traditional rules of

standing and prematurity” {Walker v. City of Bir

mingham, 388 U.S. 307, 344 (Brennan, J., dissenting) )

in order to provide an immediate response to the

threat or imposition of legal or criminal sanctions

imposed under overbroad legislation regulating

expression.

In Domhrowski, supra, “the existence of a penal

statute susceptible of sweeping and improper applica

tion” (380 U.S. at 487) generated sufficient chill to

first amendment values to warrant this Court’s inter

ference with threatened state prosecutions that were

In this area the vices of statutory vagueness and overbreadth

are often intimately related. See generally Note, The Void-for-

Vagueness Doctrine in the Sujn-eme Court, supra n. 26^at 110-

113. Indeed, at times the two are functionally indistig^iusliable.

As pointed out in N A A C P v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 432-433:

“ File objectionable quality of vagueness and overbreadtli does

not depend upon [the] al)senco of fair notice to a criminally

accused or upon unchanneled delegation of legislativ’e po\vers,

but upon the danger of tolerating, in the area of First Amend

ment freedoms, the existence of a penal statute susceptible of

sweeping and improper application.’' And see Note, The First

Amendment Overhreadth Doctrine, supra n. 25, at 871-876.

25

being brought in bad faith to harass and discourage

those intent on promoting ISTegin civil rightst^ By al

lowing injiinctive relief, the Court, without declaring

the state statute unconstitutional, effectively narrowed

the scope of its application so that “ [t]he area of pro

scribed conduct will be adequately defined and the

deterrent effect of the statute contained within con

stitutional limits * * *” (380 U.S. at 490).

The analysis was conceptually no different in Eohel,

supra, though that case involved a direct, rather than

indirect, constitutional challenge to the statute. There,

this Court, ignoring the narrow application of the dis

trict court,invalidated a statutory prohibition on

members of a “registered” Communist-action orga

nization from engaging “in any emj)]oyment in anj^

'W hile we are m in d fu l th a t th is C ourt's recent decisions in

Y o u n g er v. H arris , 401 U .S . 37, B o y le v. L andt'y , 401 U .S. 77,

an d re la ted cases decided th e sam e day, em phasize th a t aspect

o f D om hrow sJd w hich exp la in s ju d ic ia l in terven tion on the

g ro u n d of bad fa ith harassm ent, we do no t understan d those

decisions to re jec t th e analysis in D om brow shi re la tin g to the

“ch illing effect” doctrine. E athei', th e C o u rt in Y ounger, and

re la ted cases, seemed to agree th a t the existence o f a “ch illing

effect” on F ir s t A m endm ent rig h ts due to s ta tu to ry vagueness

or overb read th was essential to ju d ic ia l in terven tion in such

cases. Because o f the “ long-stand ing public policy ag a in st fed

era l cou rt in terfe rence w ith sta te proceedings * * *” (401 U .S . a t

43), how ever, i t insisted th a t “th is so rt of ‘ch illing effect * * *

should n o t by itse lf ju s tify federal in te rv en tio n ” 401 U .S. a t 50).

A n d cf. K eyisliian v. B oard o f R egen ts, 385 U .S . 589; ZroieM er

V. K oota , 389 U .S . 241.

T he d is tric t court h ad overcome the “ ‘likely constitu tional

in firm ity ’ ” o f the s ta tu te by constru ing i t as a p p lju n g only to

“active” m em bers h av in g a “specific in te n t” to fu r th e r th e goals

of th e organ ization (389 U .S. a t 26 1 ); i t concluded th a t there

h a d been no show ing th a t R obel w as w ith in th e narrow ly

defined category.

26

defense facility” (50 U.S.C. (Supp. IV) 784(a)(1)

(D) ) ; the decision was premised solely on the statute’s

inhibiting effect on the exercise of First Amehdirient

rights * * (389 U.S. at 265). Again, as iir Pom-

IjTowski, the chill that called for judicial remedy was

found in the sweep of the statute: “It Casts its met

across a broad range of assoeiational activities, in

discriminately trapping membership which can be con

stitutionally punished and membership which cannot

be proscribed” (389 U.S. at 265-266). That alone, with

out regard to the constitutional status of the particular

complainant, was the “fatal defect” (389 U.S. at 266).^“

Whether one travels the Do'inbrotvski road, or comes

by way of Bobel^ the destination is analytically the

■̂ VSee also N A A C P v. Button, 371 IJ.S. 415 (b a rra try law as

construed held void fo r o v e rb re a d th ) ; Baggett v. Bullitt, 377

XI.S. 360 (lo y a lty o a th s ta tu te held to have an in h ib itin g effect

on free speech because o f v ag u en ess); Coates v. City of Cincin

nati, supra (ord inance re g u la tin g the r ig h t to assemble

held void fo r vagueness an d o v e rb re a d th ) ; cf. A^ptheker v.

Secretary of State, 378 U .S . 500 (fed era l law re s tr ic tin g sub

versives’ rig h ts to ob tain passports held void as an overbroad

burden on fifth am endm ent r ig h t to tra v e l) . T he “ch illing

elfect” analysis in th is line of cases closely para lle ls the reason

in g of th is C ourt in cases invo lv ing licensing o f expression in

public places. See, e.g., Freedmam, v. Maryland, 380 U .S. 51; A

Quantity of Copies of Books v. Kansas, 378 U .S . 205; Staub v.

City o f Baxley, 355 U .S . 313; K unz v. Nexo York, 340 U .S. 290.

T here, too, th e vice of vagueness w a rran ted ju d ic ia l in te rv en

tion in o rd e r to p ro tec t aga in st the prospect o f “self-censorship”

of ac tiv ity pro tec ted by th e F ir s t A m endm ent. A s sta ted in

Freedman, supra, 380 U .S . a t 56, “i t is well established th a t one

has s tan d in g to challenge a s ta tu te on th e g ro u n d th a t i t dele

gates overly broad licensing d iscretion to an ad m in istra tive

office, w hether or no t h is conduct could be proscribed by a

p rop erly d raw n sta tu te , and w hether or no t he app lied fo r a

license.”

27

same. Unconstitutional vagueness or overbreadth is

a prerequisite to judicial intervention imder the

“chilling effect’’ doctrine. See generally Uote, The

First Amendment Overbreadth Doctrine, supra n. 25,

at 852-865. As this Court has emphasized repeatedly,

“ [pjrecision of regulation must be the touchstone in

an area so closely touching our most precious free

doms.” NAACP V. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 438; see also

United States v. B.obel, supra, 389 IT.S. at 265; Keyi-

shian v. Board of Regents, supra, 385 U.S. at 603.

That is the fundamental policy which sustains the

shift in judicial focus from the constitutional status

of a particular complainant’s conduct to the degree of

chill being generated on the conduct of others. “Be

cause First Amendment freedoms need breathing space

to survive, government may regulate in the area only

with narrow specificity.” NAACP v. Button, supra,

371 U.S. at 433.

2. We turn, then, to an examination of the “speci

ficity” of government regulation in the instant case.

The starting point, of course, is the grand jury sub

poena ad testificandum served on respondent on

March 16, 1970 (see n. 5 supra,) ; admittedly, it was im-

restricted in scope or application. This Court, however,

even if it should, peering very deeply, ultimately find

a reporter-source privilege in the Constitution {supra

n. 8), is not called upon in this ease to analogize

“ [t]he deterrent effect of an unbridled subpoena

power * * * to the inhibiting effect of vague and

overbroad statutes affecting First Amendment free

doms.” Uote, Reporters and Their Sources: The Con

stitutional Right to a Confidential Relationship, supra.

28

p. 17, at 336. Whatever might be the validity of that

analogy in the broader context," ̂ it is inapposite here

in light of the significant modifications the district

court made to the March 16 subpoena {supra pp. 5-6).

The appearance which respondent now resists is

exceedingly narrow. By court order, protection—

albeit qualified (p. 6 supra)—has been afforded to

“confidential associations, sources or information re

ceived, developed or maintained by him as a profes

sional journalist * *” (A. 96 105). Moreover,

“ without limiting” (ibid.) this protection, respondent

also need not reveal “ statements made to him or

information given to him by members of the Black

Panther Party unless such statements or informa

tion” were intended “for pu].)lication or public dis

closure” (*&id.). Finally, he has been given explicit

permission to interrupt the ai)pearanee to “ consult

with his counsel” outside the jury room “ at any time

he wishes” {ibid.).

These precisely defined guidelines, we submit, are

well within the “stricter standards of j)ermissible * * *

vagueness” {Smith v. California, supra, 361 U.S.

at 151) applied by this Court in the “ sensitive areas

of basic First Amendment freedoms” {Baggett v.

Bullitt, supra, 377 U.S. at 372). Disclosure has been

explicitly limited to matters wliich are non-confidential

in nature. Compare, e.g., Marcus v. Search Warrant,

C om pare 2 C hafee, Government & Mass Communications,

4 9 5 ^9 9 , w ith Note, Reporters and Their Sources: The Consti

tutional B ight to a Confidential Relationship, supra p. 17, a t

329-358. A n d see generally , BeaveT, The Newsman's Code, The

Claim of Privilege and EverymaNs R ight to Evidence, 47 Ore.

L . Rev. 243 (1968). See also G uest & S tanzler, supra n. 10.

29

367 U.S. 717, with Kingsley Booh, Inc. v. Brown, 354

U.S. 436. If that generates a chill on the right of the

public to a free press, the shiver results not from

the fear that an exercise of protected expression will

bring governmental reprisals. See, e.g., Keyishian v.

Board of Regents, supra, 385 U.S. at 604; Domhrow-

shi V, Pfister, supra, 380 U.S. at 486; NAACP v.

Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 433; ef. Speiser v. Randall,

357 U.S. 513. Rather, it comes from mere speculation

that the ‘‘Black Panthers and other dissident groups”

(A. 19), solely as a reaction against the reporter’s

appearance, will refrain from exercising protected

expression. This may occur; however, where, as here,

such self-imposed silence by dissident groups cannot

be traced to a subpoena power which, from over-

breadth or vagueness, jeopardizes confidences, its

“ chilling effect” is, we think, too incidental to war

rant judicial intervention. Cf. Younger v. Harris,

supra, 401 U.S. at 50-51.‘*‘’

Whatever the resulting pollution to the “ breathing-

space” of First Amendment freedoms {NAACP v.

Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 433)—if a newsman’s priv

ilege is indeed within that area of primary protected

activity {supra n. 8)—it comes not from a lack of speci

ficity in g'overnment regulation, but from the insistence

of a selected few to blind themselves to precisely defined

protections against compelled injurious disclosures (see

There is no evidence in th is record that the subpoena in

th is case was served on respondent in bad fa ith or fo r p u r

poses o f harassment. Sec Younger v. Harris, sugra: Boyle v.

Landry, supra, and related cases decided the same day. iSTor

has respondent ever made any such assertion. See discussion

infra, at pp.

¥ 6

4 'Z 30

pp. 3f-AX infra). That is a response—generated to a

considerable degree by “a good deal of paranoia in the

Movement” (A. 40)—which falls well outside the insu

lated area that this Court has sheltered from the chill

of unconstitutional vagueness and overbreadth. Cf.

Walker v. City of Birmingham, supra, 338 U.S. at 344-

345 (Brennan, J. dissenting).

3. There is another virtue in the precision of the

modifying order in this case. Frequently, this Court

has recognized limitations derived from the First

Amendment upon the government’s right to compel

injurious disclosures of confidential associations. See,

e.g., NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357 U.S. 449;

Talley v. California, 362 U.S. 60; Gibson v. Florida Leg

islative Investigation Committee, 372 U.S. 539; Lamont

V. Postmaster General, 381 U.S. 301.̂ ̂ In determining

which identities or associational ties must be divulged

and which are entitled to protection, it has balanced

against the governmental interest not only the direct

injury that disclosure might have on the complainant,

but also incidental injury that might result to the

particular association with which he has been linked,

such as discouragement of continued associational

ties, dissuasion of others from joining, or public

harassment. See, e.g., Konigsberg v. State Bar, 366

These decisions generally fa ll in to two ca teg o ries : (1) those

invo lv ing elforts to compel in ju rious disclosures d u rin g legis

la tive investigations, see, e.g.. Communist Party o f the United

States V. Subversive Activities Control Boa,rd, 367 U .S . 1;

Peirenhlatt v. United States., 360 U .S . 109; Sweezy v. Neva

Ilam fshire. 354 U .S . 234; an d (2) those involv ing sta tu tes

req u irin g in ju rio u s disclosures in o rder to exercise F ir s t A m end

m ent rig h ts , see, e.g.. Shelton v. Tucker. 364 U .S . 479; Bates

V. City of Little Rook. 361 U .S . 516; American Commvunica-

tlons Ass^n v. Douds. 339 U .S . 382.

31

U.S. 36; Elfbrandt v. Russell, 384 U.S. 11; cf. WMte-

Jiill V. Elkins, 389 U.S. 54; Sweezy v. New Hampshire,

supraN The underlying policy for this judicial elas

ticity is self-evident: “ Inviolability of privacy in

group association may in many circumstances be in

dispensable to preservation of freedom of association,

particularly when a group espouses dissident beliefs”

{NAAGP V. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, supra, 357

U.S. at 462).

Whenever this Court has focused on the detriment

to aggregate associational rights of all those in a par

ticular group, however, the ease has involved a chal-

'̂‘ A t least one com m entator has discussed these cases as rep

resen ting th e “substan tive [opera tion o f th e] ch illing effect”

doctrine. See Note, The Chilling E fe c t in Constitutional Law,

69 Coluin. L . Rev. 808, 822. W hile th a t analysis has concep

tu a l basis, u'8 th in k it tends to confuse the o v errid in g purpose

fo r the C o u rt’s use of “chilling- effect” : i.e., to m odify “t r a d i

tional ru les o f s tan d in g and p re m a tu rity ” in o rd e r to “insu late

all ind iv idua ls from th e ‘ch illing effect’ upon exercise o f F ir s t

A m endm ent freedom s generated l\y vagueness, overb read th and

unbrid led d iscretion * * *” {WalJeer y . City of Birmingham,

supra. 388 U .S . a t 344-345 (B rennan , J . , d is sen tin g )). In Dom-

broiosJd, Robel, an d the cases discussed eaidier, th e C o u rt v a s

no t concerned w ith the constitu tional s ta tu s of a p a r tic u la r

com p la in an t’s conduct, bu t only w ith th e F ir s t A m endm ent

rig h ts o f expression of unidentified ind iv idua ls generally . See

A. B ickel, The Least Dangerous Branch, 149-150 (1962). B y

con trast, in the cases c ited above, the constitu tional s ta tu s of

th e p a r tic u la r com plainan t’s conduct is d irec tly a t issue; the

court looks to inciden tal in ju ry to th e com plainan t’s associa-

tional ties sim ply as a m easure o f th e burden im posed on him

an d his im m ediate associates by th e s ta tu to ry requirem ent.

Because of th is fundam en ta l d istinction , we th in g these la tte r

cases should no t be lum ped together w ith th e “ch illing effect”

cases, b u t deserve separa te trea tm en t. See generally N ote, The

First Amendment Overbreadth Doctrine, supra n. 25, a t 848-

849, 911-918.

32

lenge to the same type of government activity: com

pelled disclosure of particularized constitutionally

protected associations. '̂' That el^nent is missing here.

As earlier indicated {supra pp. 2^-2^], the only informa

tion presently subject to compulsory process under the

March 16 subpoena (as judicially modified) is wholly

non-eonfidential in nature. Associational ties are

afforded explicit protection (ibid.). Moreover, pre

cisely because of the strict limitations imposed by the

district court on the scope of grand jury interrogation

(cf. LiverigM v. Joint Committee, 279 F. Supp. 205,

215 (M.D. Tenn.)), there is little danger of intrusion

“by more subtle governmental interference” (Bates v.

City of Little Rock, supra, 361 U.S. at 523). Here,

invasions into sphei*es of privacy affected by First

See, e.g.^ Sweezy v. Ne%o Hampshire., supra, 354 U .S. a t

241-242 (com pelled disclosure o f com p la in an t’s “know ledge of

the P rogressive P a r ty in New H am p sh ire o r o f persons w ith

whom he was acquain ted in th a t o rg an iza tio n ” ) ; N A A G P v.

Alabama ex rel. Patterson, supra, 357 U .S. a t 460 (“com pelled

disclosure o f the m em bership lis ts” ) ; B arerjlu tt v. United States,

supra, 360 U .S . a t 126 (com pelled disclosure of com plainan t's

“p ast or p resen t m em bership in the C om m unist P a r ty ” ) ; Bates

V. City o f Little Roch, supra, 361 U .S . a t 517 (com pelled d is

closure of “a lis t of the nam es of the m em bers of a local

b ra n ch ” of th e N A A C P ) ; Talley v. California, supra, 362 U .S.

a t 65 (“com pel m em bers of g roups engaged in th e dissem ina

tio n o f ideas to be publicly iden tified” ) ; Shelton v. Tucker,

supra,, 364 U .S . a t 485 (“com pel a teacher to disclose h is every

associational tie ” ) ; Louisiana ex rel. GremiUion v. N A AC P, 366

U .S . 293, 296 ( “disclosure o f m em bership lis ts” ) ; Gibson v.

Florida Legislative Investigation Committee, supra, 372 U .S. a t

540 (“subpoena to ob ta in the en tire m em bership lis t o f the

M iam i b ran ch ” of the N A A C P ) ; DeGregory v. Attorney Gen

eral of New Hampshire, 383 U .S. 825, 828 (com pelled disclo

sure o f “in fo rm atio n re la tin g to * * * po litica l associations of

an ea rlie r day, th e m eetings * * * a ttended , and the view s ex

pressed and ideas advocated a t any such g a th e rin g s” ).

33

Amendment concerns—however those concerns may

ultimately be defined by this Court {supra n. 8)—

have been effectively foreclosed to the investigative

jjrocess. Not even the news media seek greater jDrotec-

tion than this. As we pointed out earlier {supra pp. 18-

21), virtually all those journalists who spoke to the ques

tion of the proper scope of a reporter’s privilege in

the district court seem to agree that compelled dis

closure of nothing more than matters “for publication

or public disclosure ’ ’—as is the case under the instant

subpoena {supra, pp. 5-6)—would not jeopardize

vital professional relationships; it was the disclosure

of confidential sources, private communications and

other confidential information (including notes, files,

etc.) that caused them concern.'’̂

4. We, therefore, submit that—whatever may be its

ultimate limits—-“the exercise of the power of compul

sory process” has been “carefully circumscribed” in

this case so that the “investigative process” will not “im

pinge upon such highly sensitive areas as freedom of

speech or press, freedom of political association, and