Georgia v. Rachel Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

May 14, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Georgia v. Rachel Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1965. 8742d022-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/efa46eda-bf3a-4da5-8ea6-f6276832f4e4/georgia-v-rachel-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

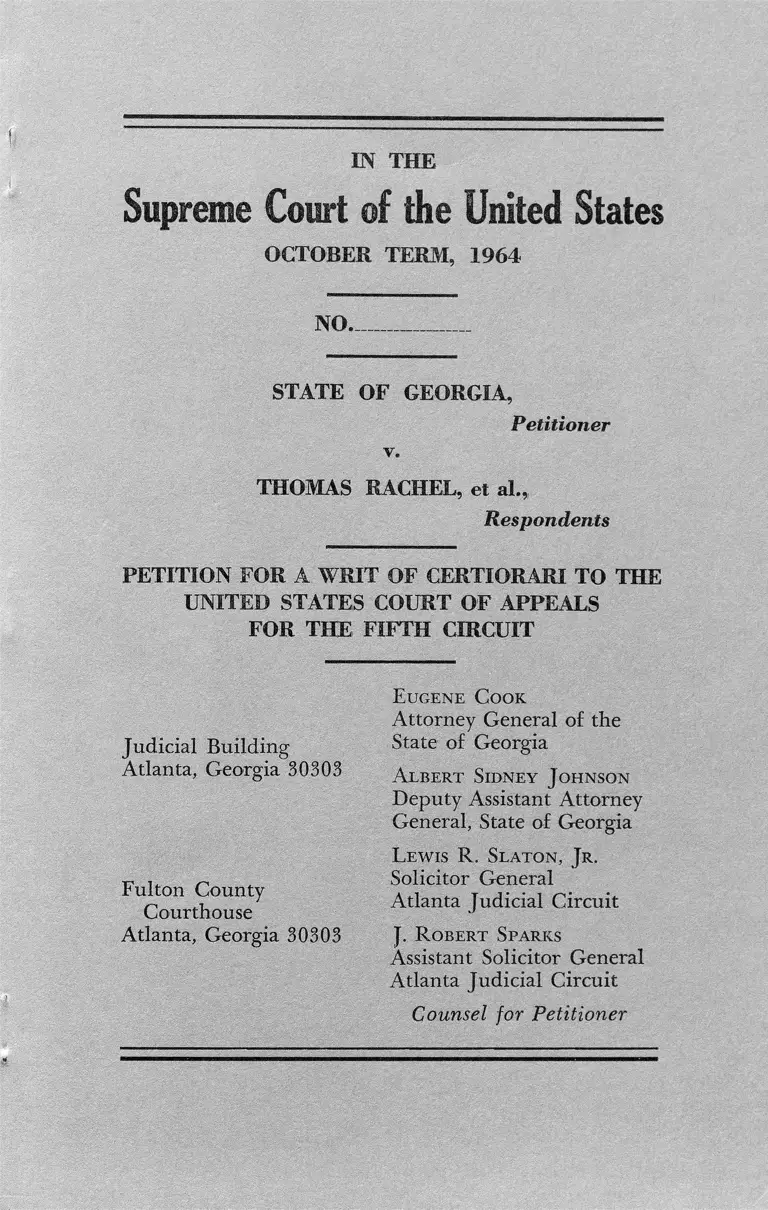

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1964

N O -.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Petitioner

v.

THOMAS RACHEL, et al.,

Respondents

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Judicial Building

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Fulton County

Courthouse

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

E u g en e C ook

Attorney General of the

State of Georgia

A l b e r t S id n ey J o hnson

Deputy Assistant Attorney

General, State of Georgia

L ew is R . S l a t o n , J r .

Solicitor General

Atlanta Judicial Circuit

J. R o b e r t Spa rks

Assistant Solicitor General

Atlanta Judicial Circuit

Counsel for Petitioner

I N D E X

Page

Petition for Writ of Certiorari _____________ »______ 1

Opinions Below _________________________________ 2

Jurisdiction ____________________________________ 2

Questions Presented ______________ 3

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved______ 6

Statement of the Case _____ _____________________ 7

Summary of Argum ent___________________________ 10

Reasons for Granting the Writ_____________________ 13

I. The Notice of Appeal of the Remand Order

was not Timely Filed, and Petitioner’s

Timely Motion to Dismiss Appeal Should

have Been G ranted____________ ___________ 13

II. The Petition for Removal does not Set Out

any Valid Ground for R em oval_______ _____16

III. Assuming Arguendo that Remand to the

District Court for an Evidentiary Hearing

was Proper, the Directions Given the Lower

Court were Clearly Erroneous _____________ 24

Conclusion _____________________________________ 28

Appendices____________________________ Ap. 1-Ap. 44

A. Order of Remand of the District Court_____Ap. 1

B. Order of Court of Appeals Staying the Order

of Remand ____________________________ Ap. 7

C. Opinion of Court of Appeals Reversing the

District C o u rt__________________________ Ap. 9

i

INDEX (Continued)

D. Opinion — Order of Court of Appeals Deny

ing Rehearing__________________________ Ap. 29

E. Constitutional Provisions and Statutes

Involved __________________ Ap. 31

F. Judgment of Court of Appeals entered pursu

ant to opinion Reversing District Court____Ap. 42

G. Order of Court of Appeals Staying

Mandate ______________________________ Ap. 44

Certificate of Service _________________________ Ap. 45

CITA TIO N S

C ases

Arkansas v. Howard, D.C. E.D. Ark., 1963,

218 F. Supp. 626 __________ ___________________19

Berman v. United States, 1964, 378 U. S. 530_______ 16

Birmingham v. Croskey, D.C. N.D. Ala., 1963,

217 F. Supp. 947 ______________________________23

Bolton v. State, 220 Ga. 632_______________________ 11, 27

City of Clarksdale, Miss. v. Gertge, D.C.

N.D. Miss., 1964, 237 F. Supp. 213______________ 22

Gibson v. Mississippi, 1896, 162 U. S. 565__________ 19

Griffin v. Maryland, 1964, 378 U. S. 130____________ 25

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, S. C., 1964,

379 U. S. 306 _________________________________ 5

Hill v. Pennsylvania, D.C. W.D. Pa., 1960,

183 F. Supp. 126______________________________ 19

Page

ii

Hull v. Jackson County Circuit Court,

6 Cir., 1943, 138 F. 2d 820______________________19

Kentucky v. Powers, 1906, 201 U, S. 1_____________ 19

Maryland v. Soper, Judge, (No. 1), 1925,

270 U. S. 9 _______ !___________________________22

Murray v. Louisiana, 1896, 163 U. S. 101__________ 19

Neal v. Delaware, 1880, 103 U. S. 370____ ________ 19

North Carolina v. Jackson, D.C. M.D. N. C., 1955,

135 F. Supp. 682 ______________________________ 19

Nye v. United States, 1941, 313 U. S. 28___________ 13

Peterson v. City of Greenville, S. G., 1963,

373 U. S. 244 ________________ ________________ 25

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, Ala., 1963,

373 U. S. 262 ____________________ ____________ 25

Smith v. Mississippi, 1896, 162 U. S. 592___________ 19

Snypp v. Ohio, 6 Cir., 1934, 70 F. 2d 535,

cert. den. 293 U. S. 563_________________________19

Texas v. Doris, D.C. S.D. Texas, 1938,

165 F. Supp. 738 _________ __ -_________________19

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 1962,

362 U. S. 199_______________ ___ _____________ 25

United States v. Robinson, 1960, 361 U. S. 220--------16

Virginia v. Rives, 1879, 100 U. S. 313----- -----------

Williams v. Mississippi, 1898, 170 U. S. 213-----------

INDEX (Continued)

Page

iii

..18

T9

C O N STITU TIO N AND STA TU T ES

C o n stitu tio n o f t h e U n it ed St a t e s :

First Amendment _________________________ Ap. 31

Fourteenth Amendment ___________________ Ap. 31

St a t u t e s and R u l e s :

Act of 1866, Sec. 3 (14 Stat. 27, 28)____________ Ap. 36

Act of 1875, Sec. 5 (18 Stat. 472)______________ Ap. 35

Act of 1887, Secs. 2 & 5 (24, Stat. 553, 555)____Ap. 35

Act of February 24, 1933,

(c. 119, 49 Stat. 904) _________________________14

Act of June 25, 1948, c. 645, (62 Stat. 683)____Ap. 41

Ga. Code Annotated, 26-3005__________________ Ap. 40

Revised Statutes, Title XIII, the Judiciary,

Sec. 641 ________________________________ Ap. 37

Rule 37 (a) (2), Title 18, U. S. C _____________ Ap. 38

Rule 54 (a) (1) (b) (1), Title 18, U. S. C___ Ap. 40

Section 3731, Title 18, U. S. C___________________ 13

Section 3732, Title 18, U. S. C .______________ Ap. 41

Section 1404, Title 18, U. S. C__________________ 13

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Sec. 201, 203_________ Ap. 41

Section 71, Former Title 28, U. S. C.

(Judicial Code, Sec. 28 )____________________ Ap. 33

Section 74, Former Title 28, U. S. C.

(Judicial Code, Sec. 31) _________________ Ap. 33

INDEX (Continued)

Page

iv

Section 76, Former Title 28, U. S. C.

(Judicial Code, Sec. 33) _________________ JAp. 34

Section 1443, Title 28, U. S. C_______________ Ap. 31

Section 1446 (a ), (c), (d ), Title 28, U. S. C— Ap. 32

Section 1447 (c ), (d ), Title 28, U. S. C________ Ap. 32

INDEX (Continued)

Page

v

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1964

NO.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

v.

Petitioner

THOMAS RACHEL, el ah,

Respondents

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

The State of Georgia, Petitioner herein, respectfully

prays that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review the

judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit entered in the above-entitled case on March

5, 1965, rehearing denied on April 19, 1965, reversing

the judgment of the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Georgia, dated February 18, 1964,

in which the District Court remanded to Fulton Supe

rior Court twenty State of Georgia criminal prosecutions

which had theretofore been removed to said District

Court under the purported authority of the Civil Rights

1

2

Acts (28 U.S.C. 1443). The judgment sought to be re

viewed reversed the remand order of the District Court

in a divided opinion, two judges dissenting in part and

concurring in part, and remanded the criminal prosecu

tions to the District Court with directions. A rehearing

was denied by the same divided opinion of the same

three judges of the Fifth Circuit panel which entered

the judgment of March 5, 1965.

OPINIONS BELOW

The pertinent opinions of Courts below which affect

the issues sought to be reviewed are as follows:

The opinion of the District Court dated February 18,

1964 is not reported, and appears in Appendix A, infra,

Pages 1-6. An order of the Court of Appeals dated March

12, 1964, staying the remand order of the District Court,

one judge dissenting, is not reported, and appears in

Appendix B, infra, Pages 7-8. The opinion of the Court

of Appeals dated March 5, 1965, two judges dissenting

in part and concurring in part, is reported at 342 F. 2d

336, and appears in Appendix C, infra, Pages 9-28. The

per curiam opinion of the Court of Appeals, one judge

dissenting and another judge dissenting in part and con

curring in part, dated April 19, 1965, denying a rehear

ing is not reported at this time, and appears in Appendix

D, infra, Pages 29-30.

JURISDICTION

The opinion of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals was

entered on March 5, 1965 (Appendix C, infra, Pages

9-28) and the judgment was entered on March 5, 1965

(Appendix F, infra, Page 42) . The opinion-order of

the Court of Appeals denying a rehearing was entered

on April 19, 1965 (Appendix D, infra, Pages 29-30).

A 30-day Stay of Mandate was granted by the Court

of Appeals on April 27, 1965 (App. G, Page 44) . The

jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

1254 (1).

QUESTIONS PRESEN TED

I. W hether a Notice o f Appeal from an order o f

rem and o f the D istrict Court entered in twenty State

Court crim inal prosecutions theretofore rem oved to

said D istrict Court under the purported authority o f

2 8 U.S.C. 1443 is timely, where said Notice o f Appeal

was not filed within ten days from the entry o f said

rem and order, as required by R ule 3 7 ( a ) ( 2 ) , Fed.

R. Crim. P.

Other subsidiary questions fairly comprised within

Question I are:

(a) Did the majority of the Court of Appeals err in

holding that the ten day time limit for filing a notice

of appeal prescribed by Rule 37 (a) (2), Fed. R. Crim.

P., has no application to this case because, as held by

the majority of the Court, that Rule applies only to

criminal appeals after verdict, or finding of guilt, or plea

of guilty?

(b) Is not Rule 37 (a) (2) specifically made appli

cable to an appeal of a remand order entered in a re

moved criminal case by the provision of Rule 54 (b) (1),

Fed. R. Crim. P. that the Criminal Rules apply to crim

inal prosecutions removed to the United States District

Courts from state courts and govern all procedure after

removal, except dismissal?

(c) Did the Court of Appeals have jurisdiction to

4

entertain the appeal where the Notice of Appeal of the

order of remand was filed sixteen days after the entry

of the remand order, and should not Petitioner’s timely

Motion to Dismiss Appeal on the grounds that the Notice

of Appeal was not timely filed have been granted?

II. Assuming arguendo that Question I is decided

adversely to Petitioner and the merits o f the judgment

of the Court of Appeals is reached, the following

question is presented: Whether the Petition for Re

moval, which does not allege that any Georgia statute

is unconstitutional and does not specifically allege a

denial o f the equal rights o f the Respondents by vir

tue of the State statute under which they were being

prosecuted in the State Court, sets forth a valid ground

for removal under Section 1443, Title 28, U.S.C.

Other subsidiary questions fairly comprised within

Question II are:

(a) Did the Court of Appeals err in holding that a

Petition for Removal need contain only the “bare bones

allegation of the existence of a right” ; that the instant

Petition for Removal did in fact allege the denial of

protected rights by State legislation; and that the Peti

tion for Removal adequately alleged that the Respond

ents suffered a denial of equal rights by virtue of the

statute under which they were being prosecuted in the

State Court?

(b) Whether the Respondents are entitled to a hear

ing in a federal forum for the purpose of proving a de

nial of their rights under a law providing for their equal

rights because of State legislation, under the meager alle

gations of the “notice-type” pleading in their Petition

5

for Removal, and whether the District Court erred in

remanding said cases to the State Court upon considera

tion of the allegations of the Petition for Removal alone,

without ordering an evidentiary hearing.

III. Whether the majority of the Court of Appeals

erred in reversing the remand order of the District

Court and remanding the cases to said District Court

with directions to hold a hearing, and in further hold

ing that, if, upon such a hearing, it is established

that the removal of the Respondents from the various

places of public accommodation was done for racial

reasons, it would become the duty of the District

Court to order a dismissal of the prosecutions with

out further proceedings, under the holding of Hamm

v. City of Rock Hill, 1964, 379 U. S. 306, 85 S. Ct.

384.

Other subsidiary questions fairly comprised within

Question III are:

(a) Did the aforesaid directions by the majority of the

Court of Appeals to the District Court misconstrue and

expand the doctrine of Hamm, supra, to mean that all

criminal prosecutions arising from removal of persons for

racial reasons from places of public accommodation must

be abated, without regard to any possible evidence as to

the peaceful or nonpeaceful conduct of the particular

Respondents involved, and did the aforesaid directions

unduly limit the discretion of the District Court in de

ciding whether the Hamm decision was controlling or

was distinguishable on other grounds based on the pos

sible evidence adduced at the hearing?

(b) Did the majority of the Court of Appeals err in

6

remanding the case to the District Court with the direc

tions aforesaid, without requiring the removing Re

spondents to prove in the hearing that the teachings of

Hamm would not be applied fairly to them by the

Georgia Courts if the prosecutions were remanded to the

State courts?

(c) Did the majority of the Court of Appeals err in

failing to affirm the District Court’s order of remand,

thus allowing the Courts of Georgia to apply the doctrine

of the Hamm decision, rendered subsequent to the re

moval of these cases, to these prosecutions?

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS AND

STA TU TES INVOLVED

The First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Consti

tution of the United States of America are involved.

The statutes involved are the following:

(1) Sections 1443 (1) (2) ; 1446 (a ), (c0 . (d) ; and

1447 (c) and (d ), Title 28, U. S. C. (62! Stat.

938, 1948; 63 Stat. 102, 1949) .

(2) Former Sections 71, 74, 76, former Title 28,

U. S. C. (March 3, 1911, 36 Stat. 1094, 1096,

1097).

(3) Act of 1866 (14 Stat. 27, 28) .

(4) Act of 1875 (18 Stat. 470, 472).

(5) Act of 1887 (24 Stat. 553, 555) .

(6) Georgia Code Annotated, 26-3005 (Ga. Laws

1960, pages 142 and 143).

(7) Rules 37 (a) (2), 54 (a) (b) (1) and 45 (a) ,

Title 18, U. S. C.

(8) Rule 73 (a ), Title 28, U. S. C.

7

(9) Revised Statutes, Title XIII, the Judiciary,

Sec. 641.

(10) Civil Rights Act of 1964, Secs. 201 (b) (2)

and 203.

(11) Act of June 25, 1948, codifying and enacting

Title 18, U. S. Code c. 645, 62 Stat., 683,

page 845.

The constitutional provisions and statutes involved

being somewhat lengthy, their pertinent text is set out

in Appendix E for Petitioner, as authorized by Rule

23 (1) (d) of this Court, Pages 31-41.

STATEM ENT OF THE CASE,

On August 2, 1963, a Grand Jury of Fulton Superior

Court, Atlanta, Georgia, indicted Thomas Rachel and

19 other defendants in separate indictments for viola

tions of Georgia Laws, 1960, pages 142 and 143, a misr

demeanor. This statute is codified as 26-3005, Georgia

Code Annotated (App. E, Page 40) .

The misdemeanor with which Thomas Rachel was

charged was his failure and refusal, on June 17, 1963,

to leave the premises of another, to-wit, Lebco, Inc.,

doing business under the name of Lebs on Luckie Street

after having been requested to leave said premises by

the person in charge.

The indictments returned against the other 19 de

fendants, who are now Respondents herein, involved

here contained identical allegations to the Rachel indict

ment with the exception that in some instances the

misdemeanor was alleged to have been committed on

another date and at a different restaurant in Fulton

County, Georgia.

8

On February 17, 1964, the Respondent Rachel and

the 19 other Respondents filed a Petition for Removal

in the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Georgia, under the purported authority of

Sections 1443 (1) (2) and 1446, Title 28, U. S. C.

(R. 2-9)

Briefly stated, the removal petition alleged that the

State of Georgia by statute was perpetuating customs

and serving members of the Negro race in places of

public accommodation on a racially discriminatory basis,

and on terms and conditions not imposed on the white

race. They further alleged that they were being prose

cuted for acts done under color of authority derived

from the Constitution and laws of the United States,

and for refusing to do an act inconsistent therewith.

(R. 2-9)

The next day after filing of the removal petition, i.e.,

on February 18, 1964, United States District Judge Boyd

Sloan issued an opinion and order remanding said cases

to Fulton Superior Court, stating in part, “ the petition

for removal to this Court does not allege facts sufficient

to justify the removal which has been effected.” (R. 10-

15; App. A, Pages 1-6.)

On March 5, 1964, the Respondents filed a Notice of

Appeal from the order of remand to the Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals, (R. 16)

The Respondents filed with the Fifth Circuit Court

of Appeals a Motion for Stay Pending Appeal, on March

12, 1964.

On March 12, 1964, a hearing was held before a three

Judge panel of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals on

9

the motion for stay of the remand order of the District

Court. Petitioner, the State of Georgia, filed a Motion

to Dismiss Appeal on two grounds. (1) that the remand

order of the District Court was not reviewable on appeal

or otherwise, and (2) the Notice of Appeal was not

timely filed, having been filed more than ten days from

the date of the remand order. (R. 26-30)

After an oral hearing, the majority of the Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals by a 2 - 1 division granted the stay.

District Judge G. Harrold Carswell, Northern District

of Florida, dissented, saying, “ I would, therefore, grant

appellee’s motion to dismiss,” (App. B, Pages 7-8)

Thereafter, after extensive oral argument before the

Court of Appeals, said Court on March 5, 1965, entered

an opinion by a divided three-judge Court reversing the

judgment of the District Court, and remanding the case

to the lower Court with instructions to hold a hearing

and to dismiss the prosecutions, if it is established that

the removal of the Respondents from the various places

of public accommodation was done for racial reasons.

(R. 42-61; App. C, Pages 9-28) Two Judges dissented

in part and concurred in part.

A timely Petition for Rehearing En Banc was filed by

the State of Georgia, Petitioner (R. 63-78) and was

denied in a per curiam opinion of the Court of Appeals

entered on April 19, 1965, with one Judge dissenting

and another Judge dissenting in part and concurring

in part (R. 79-80; App. D, Pages 29-30) . A 30-day Stay

of Mandate was granted by the Court of Appeals on

April 27, 1965 on application of Petitioner pending

submission of this Petition for Writ of Certiorari. (Ap

pendix G, Page 44)

10

The jurisdiction of the Court of first instance, the

United States District Court for the Northern District

of Georgia, was invoked by the removing Respondents

under the purported authority of Sections 1443 and

1446 (c) (d ), Title 28, U.S.C. (R. 6, 7)

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Only three very basic and important reasons for grant

ing the Writ are urged by Petitioner. First, the Court

of Appeals had no jurisdiction to consider the appeal,

inasmuch as the Notice of Appeal of the order of remand

was filed six days too late. The majority of the Court

of Appeals has held, in the first opinion known to coun

sel for Petitioner since the 1948 enactment of Title 18,

U.S.C., that the ten-day time limit of Rule 37 (a) (2),

Fed. R. Crim. P. for filing a notice of appeal from an

order in a criminal case applies only to criminal appeals

after verdict, or finding of guilt, or plea of guilty. This

novel construction of one of the basic Criminal Rules

originally promulgated by this. Honorable Court and

subsequently incorporated by reference in an Act of

Congress in 1948, alone would warrant the granting of

the Writ. One Judge of the panel dissented on this

ground alone both in the opinion on the merits and on

the petition for rehearing. This construction of the Rule

was never urged by the Respondents in their briefs or

argument before the Court of Appeals.

Secondly, the Petition for Removal completely fails,

according to all federal judicial precedent, to set out a

valid ground for removing State prosecutions to a federal

district court for trial. Petitioner urges that there is no

requirement for a hearing of the allegations of the re

moval petition and that removability must stand or fall

11

upon the allegations of the petition. All federal case

precedent, including that of this Honorable Court, sup

port this position, and Petitioner strongly maintains that

no error was committed by the District Court in re

manding the cases without an evidentiary hearing.

Finally, even if Petitioner’s first two grounds are

decided adversely to us, the Writ should be granted

because the majority of the Court of Appeals has directed

the District Court to look for only one criteria on the

hearing, and to dismiss the State Court prosecutions if

that single element is found from the evidence. That

element is, of course, the finding that racial reasons

were the cause of the removal of the Rachel, et al, de

fendants from the various restaurants. This virtual man

date to the District Court unduly limits his judicial dis

cretion in considering whether or not the prosecutions

are in fact controlled by Hamm, supra. Many distinguish

ing factors might be raised by the evidence on such a

hearing. Were the defendants peaceable and non-violent

in their demonstrations? Were the restaurants places of

public accomodation coming under the purview of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964? Under the directions of the

Court of Appeals, the District Court could consider

none of these factors, if the racial factor alone were

found.

Further, the Court of Appeals by its remand to the

District Court with directions ignores the fact that the

Supreme Court of Georgia has recognized and followed

the Hamm decision and has abated five similar State

Court prosecutions. Bolton, et al v. State of Georgia,

220 Ga. 632, decided February 8, 1965. The Hamm case

had not been decided when these (Rachel, et al) prose

12

cutions were pending in the Georgia Courts, and the

Georgia Courts have not had an opportunity to consider

these cases in connection with the Hamm doctrine. They

should be afforded that opportunity, as pointed out by

Circuit Judge Bell in his partial dissent (R. 60, App. C.,

Page 27) . The action of the majority of the Court of

Appeals amounts to a finding that the Courts of Georgia

will not apply Hamm fairly to these Respondents before

such courts have even been given the opportunity to

do so. This casual treatment of the Georgia Courts in

volves jeopardy to our dual system of courts, state and

federal, as pointed out by Circuit judge Bell. Petitioner

feels that, if these cases are remanded to the District

Court for a hearing, contrary to Petitioner’s other

grounds, at the very least these Respondents should be

required to prove that the Georgia Courts will not treat

them fairly, in the light of Hamm. If they cannot prove

this, the cases should be remanded to the State Courts.

The District Court should not have its hands tied by the

erroneous directions of the majority of the Court of

Appeals, in limiting the hearing to one issue only.

Counsel for Petitioner are not concerned in this peti

tion with the merits of the State Court prosecutions

against these Respondents, and as to the eventual out

come of same if they are remanded to the State Courts.

We are deeply concerned with the grave and highly im

portant constitutional question of whether a federal

appellate court should accept jurisdiction over State

Court criminal prosecutions and virtually order dismissal

of the actions, without ever giving the State Courts

a chance to reconsider the cases in the light of the latest

decision from this Honorable Court. Particularly is this

so in view of the Bolton decision by the highest Court

13

of Georgia, which proves conclusively that Georgia

Courts are following the decisions of the United States

Supreme Court in racial controversies.

For the foregoing reasons, Petitioner respectfully in

sists that the Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals should be granted.

REASONS FO R GRANTING TH E W RIT

I. The Notice o f Appeal o f the Rem and Order

was not tim ely filed, and Petitioner’ s timely Motion

to D ism iss Appeal should have been granted.

The majority of the Court of Appeals, with Judge

Whitehurst dissenting, held that Rule 37 (a) (2) applies

only to criminal appeals “after verdict, or finding of

guilt . . . or plea of guilty,” citing Nye v. United States,

1941, 313 U. S. 28, 43-44. Therefore, the Court held

that the notice of appeal was timely, even though filed

sixteen days after entry of the remand order. Petitioner

respectfully maintains that this was erroneous.

( a ) Rule 3 7 (a ) ( 2 ) controls the time lim it fo r

filing a notice o f appeal in a crim inal case both before

and after verdict.

The language of Rule 37 (a) (2), which is. a single

paragraph, clearly refutes the reasoning of the Court

of Appeals. The last sentence allows 30 days for an ap

peal by the government when authorized by statute. The

government may appeal before verdict in criminal cases

(1) an order suppressing evidence in a narcotics case.

(18 U.S.C. 1404) and (2) a decision dismissing an

indictment or sustaining a motion in bar, where the

defendant has not been put in jeopardy. (18 U.S.C. 3731.)

14

Only in rare instances where a judgment of conviction has

been arrested based on invalidity or construction of the

statute can the government appeal after verdict in a crimi-

inal case. If Rule 37 (a) (2) applies only to “after verdict”

judgments and orders, why does the last sentence of that

Rule deal with the government’s “ before verdict” ap

peals? The ruling of the Court of Appeals makes the last

sentence of that Rule a complete nullity. It splits a

single paragraph into two parts — the first dealing with

“after verdict” appeals by defendants and the latter pre

scribing a different time limit for both “before” and

“after” verdict appeals by the government. This is a

far-fetched construction of the Rule, and one which was

never urged even by the Respondents before the Court

of Appeals.

The Nye case, supra, is not controlling. It was decided

in 1941, and was not a criminal case, but an adjudication

of criminal contempt arising out of a civil case. The

main thrust of the decision was that “ the categories of

cases embraced in the rules cannot be expanded by inter

pretation to include this type of case.” 313 U. S. at Page

45. In Nye, the Court was interpreting Rule III, effec

tive September 1, 1934 (292 U. S. 661) under the “after

verdict” enabling Act of February 24, 1933, (c. 119, 49

Stat. 904, as amended) . Since that time, the Old Rule

III has been superseded by Rule 37, prepared by the

Advisory Committee of this Court which also prepared

Rules 1-31, 40-60. This Court by order dated February

6, 1946, directed that all the Rules (1 through 60) be

consecutively numbered, indexed, and given their title.

327 U. S. 827. It is inconceivable that the Advisory Com

mittee would have left Rules 32-39 applicable only to

“after verdict” judgments while balance of the Rules

15

applied to both “before” and “after” verdict judgments,

or that this Court in promulgating all of the Rules in

the same order intended any such result.

Finally, the Court of Appeals based its ruling in large

part on the assertion that Rule 37 (a) (2) had never

been presented to Congress. The Court of Appeals over

looked the fact that when Congress enacted the Act of

June 25, 1948, (c. 645, 62 Stat. 683) entitled “An Act

to Revise, Codify, and Enact into Positive Law Title 18

of the United States Code” on page 845 of that statute,

under Section 3732, Rule 37 (a) is incorporated by refer

ence. (See Appendix E, Page 41.)

Finally, we point out that the Court of Appeals, while

holding that Rule 37 (a) (2) was not applicable, failed

to state in its opinion what other Rule or statute would

control the time limit for a notice of appeal in the instant

case. Certainly we cannot go to the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure for an answer, because this is not a

civil case.

(b ) R ule 54 , ( a ) ( 1 ) , (b ) ( 1 ) , Fed. R. Grim. P.

specifically m akes Rule 3 7 (a ) ( 2 ) applicable to the

instant ease.

The first sentence of Rule 54 (a) (1) makes “ these

rules” applicable to all criminal proceedings in the United

States District Courts. Rule 54 (b) (1) specifically pro

vides that “ these rules” apply to criminal prosecutions

removed to U. S. district courts from state courts and

“govern all procedure after removal” except dismissal.

(Appendix E, Page 40.) The phrase “govern all pro

cedure after removal” must certainly include appeal of

remand orders. No remand order can issue until after

16

a case is removed from state to federal court. Rule 54

was promulgated by this Court on the same day as Rule

37, as previously pointed out. Therefore, counsel for

Petitioner insist that to hold that Rule 37 does not apply

to an appeal of a remand order in a criminal case flies

into the teeth of Rule 54, both generally and specifically.

Rule 54 in its broad application applies the Criminal

Rules to all criminal proceedings in district courts and

then in precise language applies the Rules to this exact

type of case.

(c) For the foregoing reasons, the Court of Appeals

erred in holding this appeal to be timely. A notice of

appeal in a criminal case not filed within the ten-day

time limit prescribed by Rule 37 (a) (2) confers no juris

diction upon the Court of Appeals, United States v.

Robinson, 1960, 361 IJ. S. 220; Berman v. United States,

1964, 378 U. S. 530. Therefore, Petitioner’s timely Mo

tion to Dismiss Appeal should have been granted.

II. The Petition for Removal does not set out any

valid ground for removal.

(a ) There is nothing in the Petition for Removal

to warrant the exercise of Federal jurisdiction.

Petitioner respectfully maintains that the Petition for

Removal is completely devoid of any valid ground for

removal of these criminal prosecutions from State to Fed

eral court. What it does not contain is more important

than the skimpy allegations set forth. The Petition for

Removal (R. 2-7) does not allege (1) that any statute

or law of the State of Georgia is unconstitutional (2)

that any civil right, or the enforcement thereof, of

Respondents is destroyed by any statute of the State of

17

Georgia or by its Constitution (3) that any statute of

the State of Georgia, or its Constitution creates an in

ability on the part of Respondents to enforce in the

Courts of Georgia their equal civil rights under the

United States Constitution.

Furthermore, there is a complete failure in the Peti

tion for Removal to set out sufficient facts to support a

removal. Only bare allegations are made that certain

Respondents sought service, food, entertainment and

comfort in certain restaurants and hotels in Atlanta,

Georgia, and were arrested pursuant to Georgia Code

Annotated 26-3005. Then appears a mere conclusionary

allegation that these arrests were effected for the sole

purpose of perpetuating customs and usages of the City

of Atlanta with respect to serving and seating Negroes,

and white persons accompanying Negroes, in places of

public accommodation upon a racially discriminatory

basis. They allege, in a pure conclusion, that they cannot

enforce their rights in the Georgia courts, but do not

allege a single fact showing why they cannot do so. They

do not specify one single Georgia law which prevents

enforcement of their rights in the State courts. More

over, they do not allege that any judge, law enforcement

officer, prosecuting attorney, or other officer of the State

of Georgia has in any way violated any of their civil

rights, or prevented them from asserting any of such

rights. In other words, there is no allegation of improper

conduct by any State official. Even if such allegations

were contained in the Petition for Removal, many fed

eral decisions hold that such allegations would not justify

removal. This woefully inadequate removal petition was

everything that the District Court had before him when

he considered, on his own motion as it was his duty

18

to do, the question of whether a cause for removal was

shown.

Petitioner will discuss briefly just a few of the con

trolling cases which illustrate beyond the shadow of a

doubt that this case is not removable under any possible

construction of the Petition for Removal.

In Virginia v. Rives, 1879, 100 U. S. 313, where two

Negroes removed their pending State trial for murder

to federal court, and the State of Virginia filed a petition

for mandamus to the United States Supreme Court to

force the remand of said cases, Justice Strong said, in

part, for the Court, in granting the petition for man

damus:

. . But in the absence of constitutional or legisla

tive impediments he cannot swear before his case

comes to trial that his enjoyment of all his civil rights

is denied to him. When he has only an apprehension

that such rights will be withheld from him when his

case shall come to trial, he cannot affirm that they are

actually denied, or that he cannot enforce them. Yet

such an affirmation is essential to his right to remove

his case. By the express requirement of the statute his

petition must set forth the facts upon which he bases

his claim to have his case removed, and not merely

his belief that he cannot enforce his rights at a sub

sequent stage of the proceedings. The statute was not,

therefore, intended as a corrective of errors or

wrongs committed by judicial tribunals in the ad

ministration of the law at the trial.” (Emphasis

added)

Virginia v. Rives, supra, holds categorically that a case

is not removable under the civil rights acts (the prede

cessor of 28 U.S.C. 1443) unless a State Constitution or

Statute on its face denies the removing defendant his

19

federal constitutional rights. In other words, there must

be discriminatory state legislation depriving him of those

rights before he can remove the case. Since that time,

federal courts have followed that rule without deviation

or modification. To list just a few, Appellee cites Ken

tucky v. Powers, 1906, 201 U. S. 1; Williams v. Missis

sippi, 1898, 170 U. S. 213; Murray v. Louisiana, 1896,

163 U. S. 101; Gibson v. Mississippi, 1896, 162 U. S. 565;

Smith v. Mississippi, 1896, 162 U. S. 592; H ullv. Jackson

County Circuit Court, 6 Cir., 1943, 138 F. 2d 820; Snypp

v. Ohio, 6 Cir. 1934, 70 F. 2d 535, cert. den. 293 U. S.

563; Arkansas v. Howard, D.C. E.D. Ark., 1963, 218 F.

Supp. 626; North Carolina v. Jackson, D.C. M.D. N.C.,

1955, 135 F. Supp. 682; Hill v. Pennsylvania, D.C. W.D.

Pa., 1960, 183 F. Supp. 126; Texas v. Doris, D.C. S.D.

Texas, 1938, 165 F. Supp. 738; and Neal v. Delaware,

1880, 103 U. S. 370. Each of the foregoing was a criminal

case, and removal was sought in each under the civil

rights acts.

The Kentucky v. Powers case, supra, appears to be the

last Supreme Court ruling on exactly what grounds will

authorize a removal under color of the civil rights acts,

and it has been followed in every instance by the lower

federal courts in the cases previously cited in this section

of this Petition. In Powers, supra, the Supreme Court

said, (201 U. S. at page 30) :

“The question as to the scope of section 64,1 of

the Revised Statutes again rose in the subsequent

cases of Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370, 386; Bush

v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110, 116; Gibson v. Missis

sippi, 162 U. S. 565, 581, 584, and Charley Smith v.

Mississippi, 162 U. S. 592, 600. In each of these cases

it was distinctly adjudged, in harmony with previous

20

cases, that the words in section 641 — ‘who is denied

or cannot enforce in the judicial tribunals of the

State, or in the part of the State where such suit or

prosecution is pending, any right secured to him

by any law providing for the equal civil rights of

citizens of the United States, or of all persons within

the jurisdiction of the United States’ —- did not give

the right of removal, unless the constitution or the

laws of the State in which the criminal prosecution

was pending denied or prevented the enforcement

in the judicial tribunals of such State of the equal

rights of the accused as secured by any law of the

United States. Those cases, as did the prior ones,

expressly held that there was no right of removal

under section 641, where the alleged discrimination

against the accused, in respect of his equal rights,

was due to the illegal or corrupt acts of administra

tive officers, unauthorized by the constitution or laws

of the State, as interpreted by its highest court. For

wrongs of that character the remedy, it was held, is

in the state court, and ultimately in the power of

this court, upon writ of error, to protect any right

secured or granted to an accused by the Constitution

or laws of the United States, and which has been

denied to him in the highest court of the State in

which the decision, in respect of that right, could

be had.”

Petitioner maintains that the Powers case still controls

the federal case law on this question of removability,

and that it has not been altered, modified, or watered-

down by any subsequent decision of the Supreme Court,

or any inferior federal court.

Thus, Petitioner has clearly shown that according to

prevailing federal case law discriminatory state legislation

which interferes with a constitutional right of defense

by the defendant must exist before a case is removable

21

under the civil rights acts. The Respondents’ Petition

for Removal does not allege this. The only statute they

mention is Georgia Code Annotated, 26-3005, which

simply makes it unlawful for any person who is on the

premises of another to refuse and fail to leave said premi-

ises when requested to do so by the owner or other person

in charge of said premises. There is nothing discrimi

natory about that statute, and nothing which in any

manner deprives a defendant of any right of defense.

The statute on its face has application to many situations

other than racial ones. It authorizes prosecution of the

drunken visitor in one’s home, the person behaving in a

disorderly manner in one’s church, or the disreputably

dressed, boisterous customer in a store, who refuses to

leave when requested. If the gist of Respondents’ com

plaint is that 26-3005 is being unconstitutionally applied,

then they have no grounds for removal. Their remedy

is to defend themselves through the State courts and

then seek review by certiorari in the United States Su

preme Court.

The Court of Appeals in their opinion impliedly rec

ognize the lack of sufficient allegations in the removal

petition. The majority refers to “ the bare bones allega

tion of the existence of a right,” and to “liberality of

pleadings under the (Civil) rules.” Circuit Judge Bell

refers in his partially concurring and partially dissenting

opinion to the removal petition as “notice type plead

ings.” In fact, the whole Court agreed to send the case

back to the District Court to allow Respondents to prove

the allegations of the removal petition, or as Judge Bell

stated “ to determine just what appellants do claim.”

(R. 60, App. C, Page 27.)

22

Finally, we direct the Court’s attention to the very

able, thorough and scholarly opinion of United States

District Judge Clayton, Northern District of Mississippi,

in City of Clarksdale, Miss. v. Gertge, 1964, 237 F. Supp.

213, in which he remanded to the State courts a removed

prosecution arising from racial incidents in which the

removal petition was far more detailed as to alleged

denial of federally protected rights in Mississippi courts

than is the removal petition in the instant case. Judge

Clayton concluded that removal was not justified under

either sub-section (1) or (2), of Section 1443, Title 28,

U.S.C. He did not hold a hearing, but rendered his

opinion on briefs directed to the face of the pleadings.

His opinion in that case is even more applicable to the

instant case, where the removal petition is so much more

inadequate.

(b ) The rem oval petition m ust stand or fa ll upon

its allegations alone, and there is no requirem ent fo r

a district court to hold an evidentiary hearing.

The Court of Appeals held that the district court

should have held a hearing, to allow the Respondents

to prove their allegations and remanded the case to the

District Court for such a hearing. Petitioner maintains

that this was error. We find no legal precedent for such

action. Removal petitions are considered on their face,

by the factual allegations.

In Maryland v. Soper, Judge, (No. 1) 1925, 270 U. S.

9, the Supreme Court said:

“We think the averments of the amended petition

in this case are not sufficiently informing and specific

to make a case for removal under Sec. 33.” (at

page 34)

23

“ These averments amount to little more than to

say that the homicide on account of which they are

charged with murder was at a time when they were

engaged in performing their official duty . . . (at

page 35) ....................

“ . . . . But they (the removing defendants) should

do more than this in order to satisfy the statute

(Section 33, Judicial Code, formerly Section 643,

Revised Statutes) . In order to justify so exceptional

a procedure (removal of criminal cases to federal

court) , the person seeking the benefit of it should

be candid, specific, and positive in explaining his

relation to the transaction growing out of which he

has been indicted, and in showing that his relation

to it was confined to his acts as an officer. As the

defendants in their statement have not clearly ful

filled this requirement, we must grant the writ of

mandamus directing the District Judge to remand

the indictment and prosecution. Should the District

Judge deem it proper to allow another amendment

to the petition for removal, by which the averments

necessary to bring the case within Sec. 33 are sup

plied, he will be at liberty to do so. Otherwise the

prosecution is to be remanded as upon a peremptory

writ.” (Italics and explanatory words in parenthesis

added.)

Petitioner thus maintains that the removability of a

case depends on the allegations of the removal petition

itself. For example, in Birmingham v. Croskey, D.C.

N.D. Ala., 1963, 217 F. Supp. 947, the Courts’ opinion

does not mention any evidentiary hearing, and reads in

brief portions as follows (217 F. Supp. 950-51) :

“As will become readily apparent, the foregoing

allegations (of the removal petition) are insufficient

to justify the removal of the case to this Court

(at page'950) and “Considered in the light of the

24

aforementioned authority, the petition for removal

to this Court does not allege facts sufficient to justify

the removal that has been granted” (at the bottom

of page 950 and top of page 951).

In other cases where remand was ordered, the follow

ing excerpts illustrate our point:

“ The petition is probably insufficient also for the

reasons, etc.” (North Carolina v. Jackson, supra at

page 683) ; “Otherwise stated, even if the material

factual allegations of the petition are accepted at

face value, the Court is not convinced, etc.” (.Arkan

sas v. Howard, supra, at page 633.)

Appellee could quote similar language from many

other cases, showing that the allegations of the removal

petitions are the only matters considered by federal dis

trict courts, and that evidentiary hearings are not re

quired or even indicated, but we feel it is unnecessary.

If District Courts are required to hold prolonged

and detailed hearings every time an inadequate removal

petition is filed, the work load of such Courts will be

greatly increased. Such petitions should be, and have

been in the past, considered strictly in the light of the

facts alleged therein. Therefore, the District Court prop

erly remanded the case without a hearing.

III. Assuming arguendo that remand to the District

Court for an evidentiary hearing was proper, the

directions given the lower court were clearly erro

neous.

The majority of the Court of Appeals directed the

lower court to dismiss the prosecutions, if upon the

hearing it appeared that racial reasons were the cause

of Respondents’ removal from the various restaurants.

25

No discretion whatever was left to the District Court

by these directions, except to make a finding of fact as

to that one issue.

(a ) The aforesaid directions to the lower court

unduly limited the judicial discretion of that Court

in applying the evidence to the doctrine of Hamm

v. City of Rock Hill.

As Circuit judge Bell points out (App. C, Page 26;

R. 59) , such a holding is tantamount to applying Hamm

in all its sweep against trespass statutes, retroactively to

the State of Georgia, and is in effect a holding that Georgia

has applied and will continue to apply its trespass statute

contrary to the teachings of this Honorable Court in

Hamm, even though Hamm had not been decided when

the cases were in the State Courts, and even though those

State Courts have not had an opportunity to deal with

these cases in the light of Hamm.

This holding assumes that any trespass prosecution

growing out of racial causes is automatically abated by

Hamm. Hamm does not hold this. It is strictly limited

to peaceful and non-violent attempts to exercise a right

to be served in places of public accommodation, without

regard to race, color or creed. A number of recent Su

preme Court decisions have also stressed the peaceful

and non-violent actions of defendants prosecuted in va

rious types of “sit-in” demonstrations. These cases are

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 1962, 362 U. S. 199;

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, Ala., 1963, 373

U. S. 262; Peterson v. City of Greenville, S. C., 1963,

373 U. S. 244; and Griffin v. Maryland, 1964, 378 U. S.

130. If the evidence should show violence or vandalism

26

on the part of Respondents, Hamm would not be

applicable.

Another issue which might arise from the evidence

in a hearing is whether or not any one of the restaurants

involved is in fact a place of public accommodation

within the meaning of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The

District Court should be allowed to determine these

matters upon the evidence, and not be restricted to one

issue as he is at present under the majority decision of

the Court of Appeals.

(b ) The District Court’ s remand order should have

been affirmed, and the criminal prosecutions returned

to Fulton Superior Court, thus allowing the Courts

of Georgia to consider the cases in the light of the

Hamm decision.

Counsel for Petitioner respectfully submit that the

Court of Appeals has gone one step further than this

Honorable Court has ever done, in returning the cases

to the District Court with directions to dismiss same if

one specific finding, i.e., racial causes for the arrests

of Respondents, is made. This wrests jurisdiction of the

cases from the Georgia Courts without giving them a

chance to apply the latest ruling of this Honorable

Court. And there is not a single allegation in the Petition

for Removal which indicates that the Respondents will

not be treated completely fairly in the Georgia Courts,

in the light of Hamm. Counsel for Petitioner agree with

Circuit Judge Bell’s opinion that Respondents should

be required to show that Georgia Courts will not apply

Hamm fairly to them. If they fail to do this, the cases

should be remanded to the State courts.

27

Any possible conjecture that Georgia Courts will not

fairly apply the doctrine of Hamm to any and all defend

ants similarly situated to these Respondents should have

been laid to rest in the case of Bolton v. State, 1965, 220

Ga. 632. The Negro defendants in Bolton, supra, were

convicted for violation of the same anti-trespass law

involved in the instant case, for sitting dowTn in, and

refusing to leave a public eating place in Athens, Geor

gia, after having been refused service. The Supreme

Court of Georgia, in reversing the convictions, said in

part, in a unanimous opinion:

“ . . . So applying the rules of Sec. 201 (b) (2),

(c) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to the facts of

this case, we find and hold that this public eating

place offers to serve interstate travelers and under

the majority holding of the Supreme Court of the

United States in Hamm v. City of Rock Hill (South

Carolina), and Lupper v. State of Arkansas, 379

U. S. 306 (13 L.E. 2d 300), both of which were

decided in one opinion on December 14, 1964, these

convictions must be vacated and the prosecutions

dismissed, notwithstanding the offense charged

against each of these defendants was committed and

convictions therefor were obtained prior to the pas

sage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In those two

cases the majority held that the Civil Rights Act of

1964 forbids discrimination in specified places of pub

lic accommodation and removes peaceful attempts to

be served on an equal basis from the category of

punishable activities. While those majority holdings

do not accord with our conception of the meaning

and purpose of the provisions of the Constitution

of this State and the Constitution of the United

States which prohibit the enactment of ex post facto

or retroactive laws (Code Sec. 1-128, 2-302), we are,

under our oaths, nevertheless required to follow

them and we will therefore do so in these cases; and

28

being so required, we therefore hold that these

pending convictions are abated by the 1964 Civil

Rights Act and it is ordered that the sentences im

posed on each of these defendants be vacated and

that the charge against each defendant be dismissed.”

(Italics added)

Counsel for Petitioner most respectfully insist that the

Georgia Courts should be afforded an equal opportunity

to rule on these cases, unless Respondents can show that

their equal rights will be denied them in the Georgia

Courts.

CONCLUSION

As stated in our summary of argument, counsel for

Petitioner are not concerned in this case with the future

of these cases if they are remanded to State courts. The

issue of whether these cases are removable to federal

courts and whether the appeal was timely are the only

questions presented. We feel they are of sufficient im

portance to warrant the issuance of the Writ of Certio

rari. To our knowledge, this is the first time the issue of

removability of criminal prosecutions from State to fed

eral court in light of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has

been presented to this Court. It is an important question

of federal law which has not been, but should be, decided

by this Honorable Court. The unusual construction by

the Court of Appeals of one of the jurisdictional Rules

of Criminal Procedure promulgated by this Court, (Rule

37 (a) (2)) is important enough alone to warrant the

issuance of the Writ.

Finally, there has been a wide disparity of views of

Federal Judges during the course of this case in the

lower federal courts. The District Judge remanded the

cases. One Judge dissented from the Order staying the

29

remand order. Two Judges dissented in part and con

curred in part in both the opinion of the Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals on the merits, and in the opinion of

that Court denying a rehearing. This Court should re

solve these conflicting views with finality.

For the foregoing reasons, Petitioner respectfully urges

this Court to grant the Petition for Writ of Certiorari

and review the judgment of the Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals.

Respectfully submitted,

Judicial Building

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(&------------------------------

* * E u g en e C ook

Attorney General of the

State of Georgia

Al b e r t S idney J ohnson

Deputy Assistant Attorney

General, State of Georgia

Fulton County

Courthouse

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

ew is R . S la to n , J r .

Solicitor General

Atlanta Judicial Circuit

J . R o ber t S parks

Assistant Solicitor General

Atlanta Judicial Circuit

APPENDIX

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX A — ORDER OF REMAND

(Filed in Clerk's Office February 18, 1964, B. G. Nash,

Clerk. By: Mary Roper, Deputy Clerk.)

IN T H E U N ITED STA TES D ISTR IC T CO U RT

N O RTH ERN D IST R IC T OF GEORGIA

A TLA N TA DIVISION

NO. 23,869

T h e St a t e o f G eorgia

v.

T hom as R a c h e l , J erry W a l k e r , L arry C raw ford

F o x , D e b b ie A m is , W il l ie P a u l B e r r ie n , J r ., L ynn

P f u h l , M ic h a e l Sa y e r , J u lia n M. Sa m st e in , R a lph

M. M o o re , R o na ld F r a n k lin T u r n er , C a r l C. A r n o ld ,

J a m es F. T h o m pso n , A r c h er C o lu m b u s B l a c k , C a rl

V in c e n t H i l l , J e a n e t t e Sto ckto n H u m e , J a m es

A rth u r C h e r r y , R u sse ll C. C a m p b e l l , A l l e n R .

E llio tt ’, A nn a J o W ea v er , and C h a r les E dward W e l l s

CRIM INAL

In a petition for removal verified by counsel, filed

in this Court on February 17, 1964, by the above named

defendants, the petitioners allege:

That they are presently at liberty on bail on a charge

of having violated Title 26, Georgia Code Annotated,

§ 3005; that they were arrested by members of the Police

Department of the City of Atlanta and that “ their

1

2

arrests were effected for the sole purpose of aiding, abet

ting, and perpetuating customs, and usages which have

deep historical and psychological roots in the mores and

attitudes which exist in the City of Atlanta with respect

to serving and seating members of the Negro race in

such places of public accommodation and convenience

upon a racially discriminatory basis and upon terms and

conditions not imposed upon members of the so-called

white or Caucasian race. Members of the so-called white

or Caucasian race are similarly treated and discriminated

against when accompanied by members of the Negro

race.”

It is alleged that petitioner, William Paul Berrien, Jr.,

was arrested ‘when he sought lodging, food, service,

entertainment and comfort at the H & G Corporation

d /b /a Henry Grady Hotel” which is alleged to be a

hotel facility open to the general public, built on real

estate owned by the State of Georgia, but leased to said

corporation. It is alleged that the other petitioners were

arrested at specified privately owned restaurants and

cafeterias in the City of Atlanta, all of the arrests being

on specified dates in 1963 and it being alleged that all

of petitioners were indicted by the July-August, 1963,

Grand Jury of Fulton County, Georgia, for violation

of said statute; that the cases are presently pending in

the Superior Court of Fulton County, Georgia, and are

set to be heard during the week of February 17 to Feb

ruary 22, 1964, “ the first case to be called for trial at

9:30 A.M. on February 17, 1964.”

Petitioners allege that this Court has jurisdiction to

hear and try the charges presently pending against them

by virtue of 28 United States Code Annotated § 1443

3

(1) (2) ; That removal is sought to protect rights guar

anteed to petitioners under the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States and to protect the right

of free speech, association, and assembly guaranteed by

the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States; that “petitioners are prosecuted for acts done un

der color of authority from the constitution and laws

of the United States and for refraining to do an act which

was, and is, inconsistent with the Constitution and Laws

of the United States;” that they are denied and/or can

not enforce in the courts of the State of Georgia the

specified rights claimed under the Constitution and laws

of the United States, “ in that, among other things, the

State of Georgia by statute, custom, usage, and practice

maintains a policy of racial discrimination.” Petitioners

pray for removal of said criminal proceedings from the

state court to this court for trial and “ that said prose

cutions stand so removed as provided for in Title 28,

United States Code Annotated, Sec. 1446(c) and (d) .”

The criminal statute under which these movant de

fendants are indicted is <$ 26-3005 of the Georgia Code,

which reads, as follows:

“ Refusal to leave premises of another when or

dered to do so by owner or person in charge, — It

shall be unlawful for any person, who is on the

premises of another, to refuse and fail to leave said

premises when requested to do so by the owner or

any person in charge of said premises or the agent

or employee of such owner or such person in charge.

Any person violating the provisions of this section

shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and upon convic

tion thereof shall be punished as for a misde

meanor.”

4

The defendants do not here contend that this statute

is unconstitutional. The Supreme Court of Georgia has

recently held that this statute does not violate the due

process clause of the federal constitution. 1

It is the duty of the district court to examine on its

own motion the question of whether a case removed to

it should be remanded to the state court without waiting

for a motion to remand. 1 2-

The removal statute — § 1443, Title 28, U. S. C. — is

to be strictly construed. 3-

A criminal prosecution or a civil cause under this

statute [28 U. S. C., $ 1443] because of a civil right or

the enforcement of such right must arise out of the

destruction of such right by the Constitution or statu

tory laws of the State wherein the action is pending.

The statute does not justify federal interference where

a party is deprived of any civil right by reason of dis

crimination or illegal acts of individuals or judicial or

administrative officers. If the alleged wrongs are per

mitted by officers or individuals the remedy is the pros

ecution of the case to the highest court of the State and

then to the Supreme Court of the United States as the

laws of the United States authorize. The statute contem

plates that during the trial of a particular case, the state

court will respect and enforce the right of the defendant

1. Clark v. State of Georgia (28971), Supreme Court of Georgia

— Case No. 22,323, decided Jan. 30. 1964.

2. In Re MacNeil Bros. Co. (CCA Mass. 1958) 259 F. 2d 386;

Westark Production Credit Ass’n v. Fidelity Sc Deposit Co.,

(D.C. W.D. Ark. 1951) 100 F. Supp. 52, 56; Rand v. State

of Arkansas (D.C. W.D. Ark. 1961) 191 F. Supp. 20; Title 28,

§ 1447 (c), U. S, C,

3. Shamrock Oil Corp. v. Sheets, 313 U. S. 100; City of Birming

ham, Ala. v. Croskey, 217 F. Supp. 947.

5

to the equal protection of the laws of the State or the

constitutional laws of the United States. 4-

The duty to enforce and protect every right granted

and secured by the United States Constitution rests

equally upon State and Federal Courts. 5-

Considered in the light of the aforementioned au

thority, the petition for removal to this Court does not

allege facts sufficient to justify the removal that has been

effected.

Since the case was improperly removed to this Court,

it is the duty of this Court to remand the same to the

Superior Court of Fulton County, Georgia, [§ 1447 (c)

Title 28, U. S. C.] and the defendants named in the

above styled case are hereby required to report without

delay to the Superior Court of Fulton County, Georgia,

and there attend from day to day thereafter as may be

ordered by said Superior Court.

It is therefore ORDERED, ADJUDGED and DE

CREED that the above styled case is hereby remanded

4. Hull v. Jackson County Circuit Court, (CCA Mich. 1943)

138 F. 2d 820; Rand v. State of Arkansas, supra, note 1;

City of Birmingham, Ala. v. Croskey, supra, note 2; People

of State of California v. Lamson, 12 F. Supp. 813; 2 Cyc. of

TTp/j Prncpfliirp Spc % ft9

5. Gibson v. State’ of Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565, 40 L. Ed. 1075;

Ex Parte Royall, 117 U. S. 241, 248, 29 L. Ed. 868 at p. 870;

Synpp v. State of Ohio, 70 F. 2d 535.

6

to the Superior Court of Fulton County, Atlanta,

Georgia.

This the 18th day of February, 1964.

B oyd S lo a n

United States District Judge

(Filed in Clerk’s Office and a True Copy Certified, This

February 19, 1964, B. G. Nash, Clerk. By Dalton K.

Kirkpatrick, Deputy Clerk.)

APPENDIX B

Appeal from the United S tates District Court

for the Northern D istrict of Georgia

Filed: M arch 12, 1964

In The United States Court Of Appeals

For The Fifth Circuit

Thom as Rachel, et al,

Appellants,

versus No. 21,354

The States of Georgria

Appellee.

Before TU TTLE, Chief Judge, WISDOM, Circuit

Judge, and CARSW ELL, District Judge.

P E R CURIAM:

This Court having heretofore, in the case of Con

gress of R acia l Equality v. City of Clinton, Louisiana,

granted a stay of the order of rem and returning the

said case to the state courts of Louisiana, pending

an appeal from such order of rem and on the m erits,

we conclude that consistent with that order a stay

should be granted to the appellants here.

The question of the appealability of an order of re

mand is presented in the C.O.R.E, ca se which will be

promptly heard by this Court. We conclude that the

effectiveness of the order of the District Court, dated

February 18, 1964, rem anding these cases to the Su

7

8

perior Court of Fulton County should be delayed pend

ing a determination of the appeal on the m erits.

It is, therefore, O RD ERED that the said order of

February 18, 1964, be and the sam e is hereby stayed

pending final disposition of this appeal on the m erits

or the earlier order of this Court.

This 12th day of March, 1964.

(Signed) E L B E R T P. TU TTLE

E L B E R T P. TUTTLE

United S tates Circuit Judge

(Signed) JOHN MINOR WISDOM

JOHN MINOR WISDOM

United States Circuit Judge

CARSW ELL, District Judge, D ISSENTING:

Orders of rem and are not appealable under the af

firm ative language of the statute, nor have the courts

before this held them so to be. The nature of the

sufficient cause to disturb this universally applied rule. I

I would, therefore, grant appellee’s motion to dis

m iss this appeal.

APPENDIX C

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 2 1 3 5 4

THOMAS RACHEL, ET AL,

Appellants,

versus

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Georgia,

(March 5, 1965.)

Before TUTTLE, Chief Judge, BELL, Circuit Judge, and

WHITEHURST, District Judge.

TUTTLE, Chief Judge: This is an appeal by the named

appellant and 19 other persons charged with the violation

of Georgia’s so-called anti-trespass statute, Title 26 Georgia

Code Annotated, Section 3005, from an order entered by

the district court without a hearing remanding the cases

for trial to the state court after they had been removed

9

10

R achel, et al. v. S ta te of G eorgia

by a petition for removal filed pursuant to Title 28

U.S.C.A. §1443(1) and (2) (the Civil Rights Removal

Sections). Having held, in the case of Congress of Racial

Equality, et al. v. Town of Clinton, Parish of East Fe

liciana, 5 Cir., 1964, . . . . F. 2d . .. ., that the enactment

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 resolved the question

of appealability of remand orders as to cases removed to

the Federal District Courts under Section 1443, supra,1

we turn directly to the merits of the appeal.2

Prior to the enactment of Section 901 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, Title 28 U.S.C.A. §1447(b) on its face seemed

to prohibit an appeal from an order of remand. It provided:

“an order remanding a case to the state court from which

it was removed is not reviewable on appeal or otherwise.”

Notwithstanding the provisions of that statute, however, a

substantial question had been raised in the CORE case,

supra, and in this case when this Court originally granted

a stay of the remand order pending appeal whether the

express provisions of 1447(b) applied to Civil Rights cases.

We discussed this issue in the CORE case. This discussion

need not be repeated by reason of the fact we have now

determined that whether or not remand orders in such cases

were appealable before the passage of the Civil Rights Act,

the adoption of that Act by Congress forecloses the issue

in favor of appealability.

The appellee’s contention that this appeal is untimely

has no merit. The notice of appeal was filed sixteen calendar

days after the order appealed from, and it could only be

considered untimely if the ten-day time limit of Fed. R.

Crim. P. 37(a)(2) were applicable. It is absolutely clear,

however, that Rule 37 has no application here.

The Supreme Court promulgated Rules 32 through 39,

without submitting them to Congress, under the authority

of the Criminal Appeals Rules Act. Act of Feb. 24, 1933,

c. 119, 49 Stat. 904, as amended, 18 U.S.C. § 3772. The only

power given under that Act was to prescribe rules of pro

cedure “with respect to any or all proceedings after verdict,

or finding of guilt by the court if a jury has been waived,

or plea of guilty . . . . ” (Emphasis added.) When it

adopted the predecessor to Rule 37(a)(2), see 292 U.S. 661,

662, and when it promulgated that Rule in its present form,

see 327 U.S. 825, the Supreme Court made it explicit that

the Rule was meant to apply only to criminal appeals “after

verdict, or finding of guilt . . . or plea of guilty.”

The question whether the predecessor to Rule 37(a)(2)

applied to a criminal appeal prior to verdict—in that case

an appeal from an adjudication of criminal contempt—was

11

R ach el, et al. v. S ta te of G eorgia

The question to be resolved on the merits of the appeal

is whether the petition for removal in this case adequately

stated a basis for removal under the indicated section of

the removal statutes. Title 28 U.S.C.A. §1443, provides

as follows:

“ §1443. Civil rights cases

Any of the following civil actions or criminal

prosecutions, commenced in a State court may be

removed by the defendant to the district court of

the United States for the district and division em

bracing the place where it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or can

not enforce in the courts of such State a right

under any law providing for the equal civil rights

of citizens of the United States, or of all persons

within the jurisdiction thereof;

(2) For any act under color of authority de

rived from any law providing for equal rights, or

squarely decided in Nye v. United States, 1941, 313 U.S. 28,

43-44. Rejecting the argument that the Criminal Rules dp-

plied to all cases that could be categorized as “criminal”, the

Court held that the history and the language of the order

promulgating the Rule required that it be applied only “with

respect to any or all proceedings after verdict in criminal

cases.” (Emphasis added.)

In 1940, Congress authorized the Supreme Court to pre

scribe rules of procedure in criminal proceedings “prior to

and including verdict.” Act of June 29, 1940, c. 445, 54

Stat. 688, as amended, 18 U.S.C. § 3771. Rules 1-31 and

40-60 were promulgated under the authority of this Act. It

is clear that Rule 37(a)(2) can find no authority in this

statute. Not only was it expressly prescribed under the

“after verdict” enabling act, see 327 U.S. 825, but, as au

thorized in that act, it was never submitted to Congress.

Under the “prior to verdict” enabling act, no rule could

become effective unless submitted to Congress for its ac

quiescence. Only Rules 1-31 and 40-60 were so submitted.

See 327 U.S. 824; Dession, The New Federal Rules of

Criminal Procedure: II, 56 Yale L.J. 197, 230 (1947).

12

R achel, et al. v. S ta te of G eorgia

for refusing to do any act on the ground that it

would be inconsistent with such law.”

The meaning of this statute, passed in a package with

the first post-bellum Civil Rights Act, Act of April 9, 1866,

14 Stat. 27, has been the subject of debate since its pas

sage. It was originally construed to cover cases in which

the defendant alleged his inability to obtain a fair trial

due to such informal impediments as local prejudice.

State v. Dunlap, 1871, 65 N.C. 491; see also Ex parte

Wells, 3 Woods 128, quoted in Kentucky v. Powers, 1906,

201 U.S. 1, 27 (Bradley, J., on circuit).

Later, the view was taken that only formal impediments,

stemming from State legislation, could give rise to such

deprivations of equal civil rights as would allow a defend

ant to invoke federal jurisdiction by removal. Kentucky

v. Powers, 1906, 201 U.S. 1. As this latter view was the

latest Supreme Court pronouncement directly on the

matter, the district court in the present case felt bound

by it. In remanding the case to the State court, the dis

trict court states that “A criminal prosecution or a civil

case under this statute [28 U.S.C.A. §1443] because of a

civil right or the enforcement of such right must arise

out of the destruction of such right by the Constitution

or statutory laws of the State wherein the action is pend

ing.”

In delineating the scope of the civil rights removal

statute for the first time, the Supreme Court placed great

stress on the necessity that the denial of protected rights

be made to appear in advance of trial, Virginia v. Rives,

13

R achel, et al. v. S ta te of G eorgia

1879, 100 U.S. 313. By way of illustration, the Court in

dicated that denials of equal rights at the hands of court

officials, occurring during trial, could not be cured by

removal but that such denials under state legislation could

be safeguarded against in this manner. It has been argued

that, under a realistic appraisal of the facts in a given

case, the Supreme Court today would recognize the right

to removal under §1443(1) even where no legislative

denial of rights is shown. See Krieger, “Local Prejudice

and Removal of Criminal Cases From State to Federal

Courts,” 19 St. John’s L. Rev. 43 (1944); Note, “Local

Prejudice in Criminal Cases,” 54 Harv. L. Rev. 679, 685-86

(1941). Such a recognition by the Court thus would re

emphasize the putative essence of Virginia v. Rives—that

the denial of equal rights must be susceptible of demon

stration before trial—and minimize the illustrative lan

guage in that case dealing with state legislation.

We have been asked by the appellants to anticipate

such an interpretation of §1443 by the Supreme Court;

however, there is no reason for us to reach that question

in this case. This is so for two reasons. First, the peti

tion in this case did allege the denial of protected rights

by State legislation. Secondly, the passage of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 and its interpretation in Hamm v.

City of Rock Hill, 1964, . . . . U.S........., provide a different,