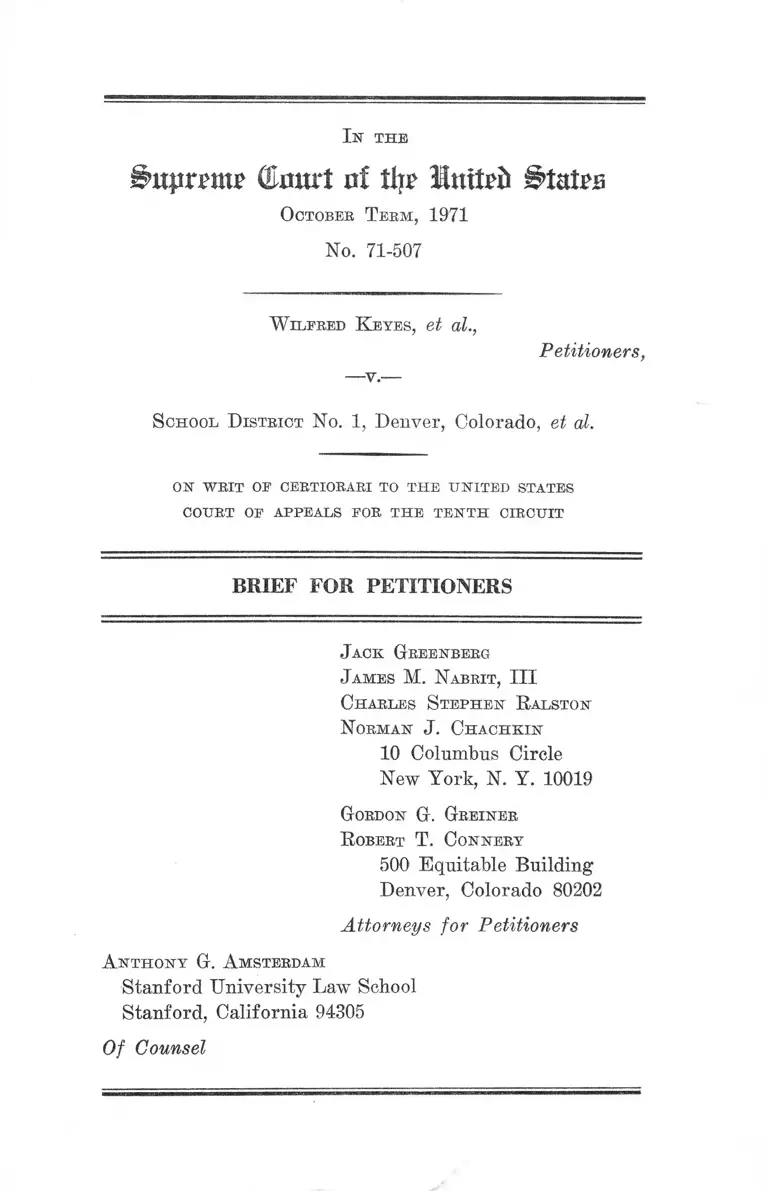

Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Brief for Petitioners, 1972. 12c63ff3-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/efacc353-4a3d-4231-a860-87aa23e4022b/keyes-v-school-district-no-1-denver-co-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

1st the

j5>uprntt£ (llmtrt nf Hit Inttpfc States

October T erm, 1971

No. 71-507

W ilfred K eyes, et al.,

-v.

Petitioners,

S chool D istrict N o. 1, Denver, Colorado, et al.

OK WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

Charles S tephen R alston

N orman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Gordon G. Greiner

R obert T. Connery

500 Equitable Building

Denver, Colorado 80202

Attorneys for Petitioners

A nthony G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinions Below .............. ......... .................................... 1

Jurisdiction .................... .................................. ........... . 3

Constitutional Provision Involved ............................... 3

Questions Presented ......................................... ............ 3

Statement ....................................................................... 4

I. Introduction ............. 4

II. The Denver School District ............................ 7

III. The Pattern of Racial Segregation ........... 8

A. Pupils .............................. 8

B. Teachers ~..................................................... 11

IV. Pupil Assignment Policies and Practices ...... 13

A. General policies and practices................ . 13

B. The Manner in Which School Authorities’

Decisions Have Determined the Racial Com

position of Schools ........ 18

1. Assigning Faculty by Race ................... 19

2. Size and Location of School Buildings;

Additions to Buildings; Capacity Utili

zation; Mobile Classrooms .............. 21

3. Transportation Policies ........................ 25

4. Establishing and Changing School At

tendance Areas ....................................... 28

PAGE

11

5. Optional Zones and Transfer Devices .... 31

6. Curriculum, Level of Instruction and the

Atmosphere of Segregated Schools...... 33

V. Denver’s Segregated Minority Schools Afford

Their Minority Students an Educational Oppor

tunity Inferior to That Afforded by Predomi

nantly Anglo Schools in the District................. 37

A. The Segregated Schools Have Homoge

neous, Low Social Class Composition Which

Deprive the Minority Children of an Impor

tant Element of Learning, a Heterogeneous

Peer Group ..... ............................................ 39

B. The Quality, Experience and Stability of

the Teaching Staffs at the Segregated

Schools Are Significantly Inferior to That

of Denver’s Predominantly Anglo Schools .. 40

1. Teacher Experience .................. 40

2. Teacher Turnover ................................. 42

3. Teacher Attitudes................................... 43

C. Inequality of Facilities ............................... 44

D. The Inferiority of the Segregated Schools Is

Also Demonstrated by the Drastically Low

Level of Academic Achievement Which They

Produce ....................................................... 44

E. Most of Denver’s Minority Children Attend

the Inferior Schools ..................................... 47

F. The Fact of the Inequality Has Been Known

for Years by the School Administration..... 47

PAGE

I l l

G-. The School Administration Obfuscated the

Poor Achievement Results at Minority

Schools......................... ................... _............ 49

H. The District Established Low Achievement

Standards for the Segregated Schools........ 50

I. Drop-Out Rates are Highest In the Segre

gated Schools ................... .......................... . 53

J. The Trial Court Determined that a Cause of

the Inequality was the Segregated Condition

of the Schools ...................... „...................... 53

K. The Respondents’ Own Policies Resulted In

Creating the Inequality of Opportunity.... 55

The Trial Court’s Conclusions as to the

Appropriate Remedy for the Inequality

of Educational Opportunity.... _............... 56

Events Subsequent to the Trial Court’s

Opinion of May 21,1970...... ..................... 62

Events Subsequent to the Issuance of the

Court of Appeals Opinion on June 11,

1971 .......................................................... 64

Summary of Argument .............................................. 65

A rgument—

I. Racial Segregation in the Denver School System

Violates the Fourteenth Amendment and Should

Be Remedied by a Comprehensive System-Wide

Desegregation Plan ................ 68

Introduction ............... 68

PAGE

IV

A. Denver’s Unconstitutional Ten Year Policy

PAGE

of Racial Segregation Necessitates a Re

quirement for System-wide School Desegre

gation ......... ............. ........................... ......... 71

B. Unlawful Segregation in Denver Is Even

More Extensive Than the Courts Below

Recognized ................................................... 79

C. Petitioners Proved a Prima Facie Case of

Unlawful Racial Segregation, But the

Courts Below Incorrectly Defined the

Burden of Proving Constitutionality Ac

tionable School Segregation ..................... 87

II. Denver’s Systematic Disparate and Discrim

inatory Educational Treatment of Minorities

Violates Equal Protection and Entitles Peti

tioners to System-Wide Relief .......... ........ ..... 92

A. Denver’s Disparate, Unequal Treatment of

Minorities in the Provision of Public Ed

ucation Violates Equal Protection .............. 93

1. The Evidence and Findings Below

Demonstrate That in Denver Minority

Children Were Consciously Treated Dif

ferently and Discriminatorily by Re

spondents’ Policies and Practices When

Compared to Anglo Children .................. 93

2. The Trial Court’s Determination of

Violation Resulted From the Proper

Application of Equal Protection Princi

ples ............ ............................... ......... . 105

V

B. The Remedy Formulated by the District

Court for the Provision of Equal Educa

tional Opportunity Was Fully Supported

by the Record and Within the Bounds of

PAGE

Proper Judicial Discretion ................. . 116

C. The Remedy Should Have Been Extended

to All of the District’s Predominantly

Minority, Inferior Schools .......................... 121

III. Considered Together the Proven Racial Segre

gation and the Proven Inequality of Educa

tional Opportunity in Denver Require a

System-Wide Remedial Approach ................... 125

C o n c lu sio n ........ ....................................................... ....................... 126

T able of A uthorities

Cases:

Barbier v. Connolly, 113 U.S. 27 (1885) ..... .................. 108

Board of Education v. Dowell, 375 F.2d 185 (10th Cir,),

cert, denied, 387 U.S. 913 (1967) ............. ................. . 113

Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F.2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970), 438

F.2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971), ----- F. Supp. ------ (E.D.

Mich. 1971) .......................................... ............. ....... 70

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103 (1965) 69

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

68,105,109,114

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955)..3, 68,117

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715

(1961) ......................................................................3,114

Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, Virginia,

182 F.2d 531 (4th Cir. 1950) ................... ................. 109

VI

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Indep. School District, 324

F. Supp. 599 (S.D. Tex. 1970) ................... ................ 124

Clemons v. Board of Education, 228 F.2d 853 (6th Cir.

1956) .... ......................................................................68, 70

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 TJ.S. 1 (1958) .........................3, 70,119

Corbin v. County School Board, 177 F.2d 924 (4th Cir.

1949) ........................... ............................................... 108

Davis v. School Dist. of City of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp.

734 (E.D. Mich. 1970), aff’d 443 F.2d 573 (6th Cir.

1971), cert, denied 404 TJ.S. 913 (1971) .... ..............70, 87

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963) ..............106,110

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.2d

988 (10th Cir. 1964) cert, denied, 380 TJ.S. 914 (1965) 113

Dunn v. Blumstein, -----TJ.S. ------ , 40 U.S.L.W. 4269

(Mar. 21, 1972) ............................................... .......... 109

Gayle v. Browder, 352 TJ.S. 903 (1956) ............... ......... 110

Green v. County School Board, 391 TJ.S. 430, 438

(1968) ......... ................................... .....75, 78,117,118,119

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) ____ ___ .....106,110

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) ................. 70

Harper v. Virginia State Bd. of Elections, 383 U.S.

663 (1966) ................ ..........................................8,109,110

Haynes v. Washington, 373 U.S. 503 (1963) .............. . 79

Hecht v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321 (1944) ................. ........ 116

Hernandez v. Texas, 349 U.S. 475 (1954) ..................... 124

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D. D.C. 1967) .... 106

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) ..................... 109

International Salt Co. v. United States, 332 U.S. 392

(1947) ................. ................ ................... ..................

PAGE

76

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U.8. 903 (1963) .................. . 110

Jones v. Newlon, 81 Colo. 25, 253 Pac. 386 (1927) ...... 68

Keyes v. School District No. One, 396 U.S. 1215 (1969) 6

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944) ___ 124

Kramer v. Union Free School District, 395 U.S. 699

(1969) ...... .............. ............. ........................... ....... 110

Lee v. Washington, 390 U.S. 333 (1968) ..................... 110

Los Angeles Local 626 v. United States, 371 U.S. 94

(1962) ...................................................... .......... ........ 76

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) ................... ..... 108

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350

U.S. 877 (1955) ............................................. .......... 110

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) ................. 108

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950) ...................... ................... ..... .............. .....107,108

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association, 347

U.S. 971 (1954) ........ .................. ...................... ...... 110

Norres v. Alabama, 332 U.S. 463 (1946)........................ 110

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948) ..................... 78

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) ..................... 108

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ..................... 110

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1969) .............................. 69

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) ................. 109

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ......................... 108

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942) ................. 110

Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1873) .... 107

V l l

PAGE

vm

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 311

PAGE

F.Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970) ........... .................25,70,87

Spano v. New York, 360 U.S. 315 (1959) ........... 78

Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156 (1953) .................. 78

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 318 F.2d 425 (5th Cir. 1963), 333 F.2d 55 (5th

Cir. 1964 ......................................... ......... . ....... 794

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) ___ 107

Swann v. Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ....69, 70,

75, 83, 84, 86, 87,

90,116,117,118,121

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 ..................21,16,107,108

Taylor v. Board of Education of City Sch. District

of City of New York Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181

(S.D. N.Y. 1961), appeal dismissed, 288 F.2d 600

(2nd Cir. 1961), 195 F. Supp. 231 (S.D.N.Y. 1961),

aff’d, 294 F.2d 36 (2nd Cir. 1961), cert, denied, 368

U.S. 940 (1961) ........................................ ................ 70

Turner v. Fouche, 396, U.S. 346 (1942) ....... ............. 110

United States v. Aluminum Company of America, 148

F.2d 416 (2nd Cir. 1945) ................... ................... 76

United States v. Bausch & Lomb Optical Co., 321

U.S. 707 (1944) .... ............................................... _____ 76

United States v. Board of School Commissioners of

Indianapolis, 332 F.Supp. 665 (E.D., Ind, 1971) .... 70

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, 399 U.S. 225 (1969) ......... .................................. 69

United States v. School Dist. No. 151, 286 F. Supp. 786

(N.D. 111., 1967), affirmed, 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir.

1968), on remand, 301 F. Supp. 201 (N.D. 111. 1969),

affirmed, 432 F.2d 1147 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied,

402 U.S. 943 (1971) ............ ...................................... 70; 87

IX

United States v. U. S. Gypsum Co., 340 U.S. 76 (1950) 76

United States Gypsum Co, v. National Gypsum Co., 352

U.S. 457 (1957) ...................... .................................. . 76

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) .... 13, 42,108,124

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions

28 U.S.C. §1343 .......................

42 U.S.C. §1983 ....... ................

Consl. Colo., Art. IX, Section 8

Other Authorities

Colorado D epartment of E ducation, H uman R elations

in Colorado, A H istorical R ecord (1968) ...... ........ 5

Comment, 48 D enver L.J. 417 (1972) ............................ 82

Diamond, School Segregation in the North: There Is

But One Constitution, 7 Harvard Civil Rights-Civil

Liberties Law Review 1 (1972) ............................... 89, 91

PAGE

5

5

69

In the

§>u*in>utT (Emtrf of tl?r ^fat^o

October T erm, 1971

No. 71-507

W ilfred K eyes, et al.,

Petitioners,

— v . —

S chool D istrict N o. 1, Denver, Colorado, et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The principal opinions of the courts below are as follows:

1. Opinion of District Court granting preliminary injunc

tion, July 31, 1969, reported at 303 F. Supp. 279 (App. to

Pet. for Cert. la-19a).

2. Opinion of District Court making supplemental find

ings and conclusions, August 14, 1969, reported at 303 F.

Supp. 289' (App. to Pet. for Cert. 20a-43a).

2

3. Opinions of District Court on merits, March 21, 1970,

reported at 313 F. Supp. 61 (App. to Pet. for Cert. 44a-98a).

4. Opinion of District Court on remedy, May 21, 1970,

reported at 313 F. Supp. 90 (App. to Pet. for Cert. 99a-

121a), and final decree June 11,1970, unreported (A. 1970a).

o. Opinion of Court of Appeals, June 11, 1971, reported

at 445 F.2d 990 (App. to Pet. for Cert. 122a-158a).

Other opinions filed in this case are as follows:

6. Opinion of Court of Appeals vacating’ preliminary

injunction, August 5, 1969, unreported (A. 455a).

7. Opinion of Court of Appeals staying preliminary in

junction, August 27, 1969, unreported (A. 459a).

8. Opinion of Mr. Justice Brennan as Acting Circuit

Justice reinstating preliminary injunction, August 29, 1969,

reported at 396 U.S. 1215 (A. 464a).

9. Opinion of Court of Appeals on motion to amend

stay, September 15, 1969, unreported (A. 467a).

10. Opinion of District Court denying Motions to Dis

miss, October 17, 1969, unreported (A. 475a).

11. Opinion of Court of Appeals granting stay, March

26, 1971, unreported (A. 1981a).

12. Per curiam Order of Supreme Court of the United

States vacating stay, April 26, 1971, reported at 402 U.S

182 (A. 1984a).

3

13. Opinion by Court of Appeals on Motion for Clarifi

cation, August 30, 1971, unreported (A. 1987a).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered June

11, 1971 (App. to Pet. for Cert. 159a-160a). On September

8, 1971, Mr. Justice Marshall granted an extension of time

for filing the petition for certiorari to and including Octo

ber 9, 1971. The Petition for Writ of Certiorari was filed

October 8, 1971, and granted January 17, 1972 (A. 1988a).

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1254(1).

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

Questions Presented

Whether petitioners are entitled to obtain system-wide

relief to desegregate the Denver public schools because:

1. The district court’s findings that “during the ten year

period preceding . . . [1969] . . . the Denver School Board

has carried out a segregation policy” (303 F. Supp. at 287),

establish that the deprivation of constitutional rights of

black pupils in Denver is so substantial and systemic as

to require the use of remedial doctrines applied to dual

systems created by segregation statutes.

4

2. The district court erred in ruling segregation to be

“innocent” and lawful in certain schools serving Denver’s

older black neighborhood—including particularly Manual

Training High School—because the court applied incorrect

legal standards and perspectives in making its decision on

intent to segregate and the causes of segregation.

3. The court below erred in holding that the sole cri

terion of constitutionally actionable racial segregation was

segregationist intent judged by the narrow test whether

decisions of the school board resulting in racial separa

tion could conjeeturally be explained by any conceivable

non-racial explanation.

4. The Denver public schools have denied equal pro

tection of the laws to students assigned to a number of

predominantly Black and Hispano schools where there is

manifestly an inequality in educational opportunity, both

from the standpoint of the input resources placed in the

schools by the school board and the educational achieve

ment of the pupils.

S ta tem en t

I. Introduction.

This suit was commenced June 19, 1969, by petitioners,

the parents of eleven children attending the Denver pub

lic schools, who seek injunctive and declaratory relief to

remedy racial segregation of children and faculty and

racial discrimination in the district’s provision of public

education. A. 3a. The complaint alleged that the district’s

practices violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Four

5

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States,

and invoked the civil rights jurisdiction of the United

States District Court for the District of Colorado. 28

U.S.C. §1343, 42 U.S.C. §1983. A. 4a. Plaintiffs asked for

“a comprehensive plan for the school district as a whole”

to remove segregation and afford equal opportunity. A. 32a.

After extensive litigation, the district court concluded

that the school district had indeed violated petitioners’

constitutional rights by various racially discriminatory

practices, including deliberate segregation of black from

white pupils in certain schools, and operation of a num

ber of schools attended by Negro or Hispano1 pupils where

there was a serious and systematic denial of a chance for

an equal education to pupils of these minority groups.

The district court first entered a preliminary injunc

tion requiring the board to implement three resolutions it

passed and rescinded prior to the lawsuit which were in

tended to begin desegregation of certain black schools in

northeast Denver and to stabilize others in danger of be

x¥ e adopt the term “Hispano” as it is customary in the school

district and used throughout the record. A Colorado Department

of Education publication explains the usage in this m anner:

“And as for a name for the people of this Latin heritage to go

by, it has not yet been agreed upon. The term ‘Hispano’ is

popular in their intellectual circles today. The late Jack Guinn,

a staff writer for the Denver Post, quoted Dr. Daniel T. Valdes,

historian and professor of sociology in Denver’s Metropolitan

State College, on the subject:

‘Hispano is a cultural term accurately applied to people of

and from Spain, Mexico and Cuba, and any other country

with a Spanish heritage. I t avoids the confusion of hy

phenated words, such as Spanish-Ameriean and Mexican-

American, which are sometimes resented.’ ”

C olorado D epartm ent of E ducation , H um an R elations in

Colorado, a H istorical R ecord, 203 (1968).

Similarly, Caucasians or whites are often referred to in the record

as “Anglos.”

6

coming segregated. The preliminary injunction took ef

fect in September 1969, after the order was twice vacated

by the Tenth Circuit and ultimately reinstated by Mr.

Justice Brennan as Acting Circuit Justice. Keyes v. School

District No. One, 396 U.S. 1215 (1969).

In May 1970, the district court entered a final decree

requiring a variety of remedies to redress the constitu

tional violations. The opinion on the merits reaffirmed

the earlier findings of certain deliberate segregation prac

tices and policies, but held that plaintiffs had failed to

prove segregationist purpose and effect with respect to

other schools not dealt with in the preliminary injunction

hearing. The court also found that defendant board had

failed to provide equal educational opportunity to students

at a number of predominantly Negro and Hispano schools

and that this denied equal protection. The trial court for

mulated a varied remedial plan, including (a) making per

manent the temporary injunction, (b) desegregating 17

minority schools by such techniques as redistricting, trans

portation, specialty schools, and free transfer programs,

and (c) ordering various “compensatory education” pro

grams to improve the quality of education offered to mi

nority students.

On appeal by the school board the Tenth Circuit affirmed

in part and reversed in part. It affirmed the relief orig

inally granted in the temporary injunction, and some ad

ditional measures relating to the northeast part of the

City, upholding the trial court’s findings that the school

board engaged in an unconstitutional policy of deliberate

racial segregation with respect to certain schools. How

ever, the appeals court reversed the finding that there was

a denial of equal protection by unequal treatment of mi

norities in predominantly Negro and Hispano schools, and

set aside the relief requiring desegregation and educational

7

improvement programs for minority students not covered

by the board’s three 1969 desegregation resolutions en

forced by the preliminary injunction. The court of appeals

also rejected plaintiffs’ appeal seeking the desegregation

of nine other minority schools not covered by the district

court’s order.

II. The Denver School District.

During the 1968-69 school term, School District No. 1,

which serves Denver, operated 119 schools with 96,5802

pupils.8 The principal minority groups are Negroes (14%)

and Hispanos (20%); a more detailed breakdown of the

attendance pattern appears below.4 The system employed

2 There were 92 elementary schools, 15 junior high schools, 2

junior-senior high schools, and 7 senior high schools for a total of

116 regular schools. In addition, the board operated an Opportu

nity School, a Metropolitan Youth Education Center, and an A ir

craft Training Facility. See DX-HK, p. 26, A. 2158a.

3 References herein to those portions of the transcript of the

various proceedings below, which are not reproduced in the Ap

pendix will be made as follows:

—the hearing on the preliminary injunction, held Ju ly 16, 18,

21 and 22, 1969, will be cited as “P.H. Tr.” ;

—the hearing on the merits, held during February, 1970, will be

cited as “Tr.”;

—the hearing on relief held in May, 1970, will be cited as “R.H.

T r.”

Exhibits introduced by petitioners, plaintiffs below, will be cited

as “P X ” ; defendants’ exhibits will be cited as “D X,”

4 Source: PX 242, 243, 273, 274, 302, 303; A. 2050a; A. 2053a;

A. 2072a; A. 2074a; A. 2078a; A. 2080a.

Anglo Negro Ilispano

Pupils No. % No. % No. % Total

Elementary 33,719 61.8 8,297 15.2 12,570 23.0 54,586

Jr. High 14,848 68.7 2,893 13.4 3,858 17.9 21,599

Sr. High 14,852 72.8 2,442 12.0 3,101 15.2 20,395

Total 63,419 65.7 13,632 14.1 19,529 20.2 96,580

8

4,443 classroom teachers, including 7% Negroes and 1.9%

Hispanos.6 The city covers 98.4 square miles, including

substantial areas annexed in the last thirty years.6 The

school budget for 1968-69 was more than $91.5 million

dollars.7 The district is governed by an elected board of

seven members.

III. The Pattern o f Racial Segregation.

A. Pupils.

At the outset of this case Denver schools were character

ized by an intense pattern of isolation of black pupils from

white pupils and an intense concentration of black teachers

in schools with black pupils. Nearly three-fifths of the

Negro pupils attend schools which are less than 10% Anglo,

and nearly 4/5ths were in schools less than 30% Anglo:8

5 Source: PX 244, 245, 275, 276, 304, 305; A. 2055a; A. 2057a;

A. 2075a;A . 2076a; A. 2081a;A . 2082a.

Anglo Negro Hispano Other

Teachers No. % No. % No. % No. % Total

Elementary 2,012 88.8 193 8.5 39 1.7 21 .9 2,265

Jr. High 881 88.5 87 8.7 22 2.2 6 .6 996

Sr. High 1,103 93.3 44 3.7 21 1.8 14 1.2 1,182

Total 3,996 89.9 324 7.3 82 1.9 41 .9 4,443

6 The district grew from 58.8 sq. miles in 1940 to 98.4 sq. miles in

1969. DX HK, pp. 20-21; A. 2158a.

7 DX HK, p. 19, A. 2158a.

8 The district judge adopted a rule of thumb that schools with

more than 70% of a single minority group were “segregated.” 313

F. Supp. at 77; 313 F. Supp. at 92.

9

N um ber and P ercentage of P u pils

1968-1969

A ll S chools

Percentage

of Anglo No. of Anglo Negro Hispano

Students Schools No. % No. % No. %

90-100% 31 28,096 44.3 379 2.8 845 9.3

80-89% 20 13,863 21.9 316 2.3 1,959 10.0

70-79% 15 7,609 12.0 595 4.4 1,921 9.8

60-69% 9 4,788 7.5 46 .3 2,413 12.4

50-59% 7 4,354 6.9 1,389 10.2 2,332 11.9

40-49% 4 1,163 1.8 140 1.0 1,340 6.9

30-39% 7 1,412 2.2 90 .7 2,232 11.4

20-29% 5 990 1.6 1,684 12.4 1,320 6.8

10-19% 8 870 1.4 1,346 9.9 3,372 17.3

1-9% 8 252 .4 4,785 35.1 1,441 7.4

less than 1% 4 22 0 2,862 21.0 354 1.8'

Total 118 63,419 100 13,632 100 19,529 100

Source: P X 242, 243, 273, 274, 302, 303; A. 2050a; A. 2053a; A.

2053a; A. 2072a; A. 2074a; A. 2078a; A. 2080a.

The pattern of pupil segregation existed at all levels.

At the elementary level where 92 schools serve compar

atively smaller neighborhoods than at the secondary level,

the pattern was particularly intense. Two-thirds of the

black elementary pupils attended ten schools,9 all of which

had less than 10 percent Anglo pupils; indeed, one-third

were in schools with less than 1% Anglo populations.

More than four-fifths of the black elementary children at

9 The ten schools with less than 10% Anglo students in 1968-69

w ere: (less than 1%)-—Barrett, Columbine, Mitchell and W hittier

(less than 10% )—Crofton, Gilpin, Harrington, Smith, Stedman and

W yatt. Crofton, Gilpin and W yatt had Hispano majorities and sub

stantial numbers of black pupils.

10

tended schools less than 20 percent Anglo. The table in

note 9 shows the breakdown.10

Black junior high pupils were concentrated at Cole,

Morey and Smiley. More than four-fifths of the black

junior high pupils (2423 out of 2893 or 83.7%) attended

these three schools with 4 percent of the Anglo population.

The remaining 470 black students were scattered among

14 other junior high schools with 95.6% of the Anglos.

At the high school level blacks were concentrated in

Manual Training High School and East High School which

served 91% of all black high school pupils and 10% of

Anglo pupils. Out of a total of 2,442 black high school

pupils there were 1,200 (49.1%) at Manual, the only

predominantly minority high school. Manual had 78

Anglo and 300 Hispano pupils. Another 1,039 black pupils

attended East High School (53.7% Anglo). The remain

ing 203 black pupils were scattered in 7 predominantly

Anglo high schools with 13,365 Anglos.

N um ber and P ercentage op P upils

1968-69

E lem enta ry S chools

Percentage

of Anglo No. of Anglo Negro Hispamo

Students Schools No. % No. % No. %

90-100% 22 13,614 40.4 242 2.9 401 3.2

80-89% 17 8,426 25.0 267 3.2 1,109 8.8

70-79% 11 4,164 12.3 404 4.9 894 7.1

60-69% 8 2,986 8.9 41 .5 1,490 11.9

50-59% 4 1,129 3.3 212 2.6 687 5.5

40-49% 3 711 2.1 76 .9 766 6.1

30-39% 7 1,412 4.2 90 1.1 2,232 17.S

20-29% 3 393 1.2 145 1.7 1,072 8.5

10-19% 7 734 2.2 1,257 15.2 2,713 21.6

1-9% 6 128 .4 2,701 32.6 852 6.8

less than 1% 4 22 .1 2,862 34.5 354 2.8

Total 92 33,719 100 8,297 100 12,570 100

Source: P X 242, 243; A. 2050a; A. 2053a.

11

B. Teachers.

Negro classroom teachers have been assigned in those

schools where black pupils are concentrated. The District

Court found that this concentration results from a delib

erate school district policy of assigning black teachers

to teach black children. 303 F. Supp at 284-285. In 1964,

the Voorhees Committee, appointed by the Board to study

the school system, reported this policy and urged its aban

donment :

While precise statistics are not available, the Com

mittee believes that almost all of Denver Negro teach

ers were initially assigned to schools having a high

proportion of Negro students. A few have been trans

ferred to other schools. There is now at least one

Negro teacher in each senior high school except for

Manual which has eleven. Nine out of thirteen junior

high schools have one or more Negro teachers, and

Cole has thirty-three. One or two Negro teachers have

been placed in each of seven elementary schools other

than those which contain large numbers of Negro

children.

Spanish surname teachers are fewer in number than

Negro teachers and the housing pattern of people of

Spanish-American background is more dispersed. How

ever, it does appear that relatively few Spanish sur-

named teachers have been assigned to areas where

there are few or no residents with Spanish-American

background.

As a result of its interviews the Committee is con

vinced that race has been relevant in the assignment

of teachers. It appears that the administration has

been extremely reluctant to place Negro and Spanish-

American teachers in predominantly white schools be

cause of concern with a possible lack of acceptance on

12

the part of a white neighborhood and a realistic assess

ment of the possible lack of support by some prin

cipals and faculties.

# # #

Recommendations as to Teacher Assignment and

Transfer

1. The Board of Education should establish and en

force a policy that qualified teachers of minority

background will be assigned throughout the system.

A. 2015a-2016a.

Former Superintendent Oberholtzer confirmed that the

racial policy was deliberate and he defended it on the

ground that Negro teachers should be assigned to schools

with concentrations of Negro pupils for whom they would

have “immediate empathy” and for whom they would be

“role-models”. A. 1352a. In 1964 there were about 15

schools with Negro teachers, all located in the central part

of the City. A. 1165a. By 1969-70, Negro teachers had

been assigned to many more schools, but a disproportionate

concentration remained in the schools with most of the

black pupils.

In 1969-70 at the elementary level, with 193 Negro ele

mentary teachers, 91 were concentrated in 9 schools, each

of which had less than 10% Anglo pupils,11 and 121 (62%)

were in schools with less than 20% Anglo pupils.12 At the

junior high level, 60 of 87 black teachers, or 68%, were

11 Thus, 91 or 47 % of the black elementary teachers are assigned

to Barrett, Columbine, Mitchell, W hittier, Gilpin, Harrington,

Smith, Stedman and W yatt. The only school with less than 10%

Anglo pupils which has no Negro teacher is Crofton, a predomi

nantly Hispano school. See PX 244, 245, 275, 276, 304, 305; A.

2055a; A. 2057a; A. 2075a; A. 2076a; A. 2081a; A. 2082a.

12 Ibid. See Ebert, Elmwood, Fairmount, Fairview, Garden Place,

Greenlee and Hallett schools (each with 10-19% Anglo pupils) with

a total of 30 black teachers.

13

assigned to the three schools—Cole, Morey and Smiley—

serving four-fifths of the black junior high pupils. Among

senior high school pupils 25 of the 44 black teachers are

assigned to Manual Training High School, the only pre

dominantly minority high school in the district. Adding

the six black teachers at East High School to those at

Manual, we find 31 of the 44 black teachers (70%) at the

two high schools attended by nine-tenths of the black high

school students. The district judge concluded that the

“tendency to concentrate minority teachers in minority

schools has helped to seal off these schools as permanent

segregated schools.” 303 F. Supp. at 284-285.

IV. P upil Assignm ent Policies and Practices.

The largest portion of the record relates to the pupil

assignment practices of' the Denver school authorities. The

courts below made detailed findings on this subject. We

undertake to summarize the major findings and evidence.

A. General policies and practices.

The district court found that the Denver school system

had carried out a segregation policy for a ten year period

prior to the filing of this lawsuit. Judge Doyle wrote:

We have seen that during the ten year period preced

ing the passage of Resolutions 1520, 1524 and 1531, the

Denver School Board has carried out a segregation

policy. To maintain, encourage and continue segrega

tion in the public schools in the face of the clear man

dates of Brown v. Board of Education cannot be

considered innocent. 303 F. Supp. 279.

Judge Doyle found that the “climactic and culminative

act of the Board was the June 9 rescission of Resolutions

1520, 1524 and 1531” and “there can be no gainsaying the

14

purpose and effect of the action as one designed to segre

gate.” 303 F. Snpp. at 285.

The ten year period of undeviating and uniform conduct

to concentrate the growing Negro population in separate

schools in northeast Denver and to keep other schools white

is detailed in the opinions below. See 303 F. Supp. at 284-

286, 290-295; 313 F. Supp. at 64-69; 445 F.2d at 996-1002.

Judge Doyle sums it up:

Between 1960 and 1969 the Board’s policies with re

spect to these Northeast Denver schools show an un

deviating purpose to isolate Negro students first in

Barrett, and later in Stedman and Hallett while pre

serving the Anglo character of schools such as Philips

and Park Hill. The ultimate effect of the Board’s

actions and policies in the face of a steady influx of

Negro families into the area was to create and main

tain segregated situations at Barrett, Stedman, and

Hallett which ultimately led to a substantially segre

gated situation at Smiley. 303 F. Supp. at 294-295.

During part of the period the board was carrying out

its “undeviating purpose” to segregate Negro pupils, it

claimed to operate under a color-blind neighborhood as

signment policy. Indeed, the former Superintendent, Dr.

Oberholtzer, thought that Colorado’s constitutional prohibi

tion against racial classifications of school children actually

prevented him from adopting any policy designed to fur

ther integration or relieve the concentration of Negroes in

certain schools. A. 1370a-1371a. At the same time that the

school system was deliberately establishing segregated

schools, the “view of the school administration [was] that

it was precluded from taking action which would have an

integrating effect”. 313 F. Supp. 65.

Community protests in 1962 by black and civil rights

groups over a plan to build an all-black junior high school

15

in northeast Denver on the same site with Barrett led the

board to form the Special Study Committee on Equality

of Educational Opportunity in the Denver Public Schools

(sometimes called the Voorhees Committee) which issued

a report in 1964. PX 20; excerpts at A. 1997a-2020a. The

1964 report criticized the hoard’s school boundary policies

as perpetuating racial isolation, as well as the policy of

concentrating minority faculties in minority schools. The

committee concluded that segregated schools resulted in

inequality in educational opportunity and recommended a

policy of considering racial and ethnic factors in setting

boundaries to minimize segregation and establish heter

ogeneous schools. The school board adopted such a position

—Policy 5100 (PX 1; A. 1989a)—and then did nothing to

implement. the policy. 303 F. Supp. at 283. “Nothing of

substance was accomplished”. 445 F.2d at 996. The 1966

Berge Committee (PX 21) appointed by the board also

suggested changes to lead to integration, but “Again, the

recommendations were not effected”. 445 F.2d at 996.

In May 1968 the board by a 5-2 vote adopted the Noel

Resolution (Res. 1490, PX 2, A. 1991a), proposed by Mrs.

Rachel Noel, its only black member, directing the super

intendent to prepare a “comprehensive plan for the inte

gration of the Denver Public Schools,” for adoption no

later than December 31, 1968. Superintendent Gilberts pre

sented a plan in October 1968. DX-D; excerpts at A. 2128a.

Eventually Dr. Gilberts proposed and the board adopted

three resolutions relating to school segregation: Res. 1520

(Jan. 30, 1969), PX 3, A. 42a; Res. 1524 (Mar. 20, 1969),

PX 4, A. 49a; and Res. 1531 (Apr. 24, 1969), PX 5, A. 60a.

The three resolutions constituted a modest and tentative

step to deal with segregation. Resolution 1531 was aimed

at 2 black schools in northeast Denver (Barrett and Sted-

man) and two nearby Anglo schools (Park Hill and Phil

ips). It desegregated Barrett by changing boundaries and

transporting students to and from white schools. It left

16

Stedman with the same predominantly black percentage but

reassigned about 120 blacks to white schools permitting the

removal of 4 mobile classrooms from Stedman. The resolu

tion also made boundary changes and used transportation

to stabilize Philips and Park Hill as Anglo majority schools.

The resolution also sought to integrate Hailett by promot

ing voluntary exchanges with white schools, a program

started by a group of white parents in January 1969.

Resolutions 1520 and 1524 proposed to desegregate Smiley

Junior High by boundary changes, and sought to prevent

East High School from becoming segregated by other boun

dary changes. Finally, Resolution 1524 reassigned some 200

pupils from the majority black Cole Junior High to other

schools, reducing the number attending this school, which

would nevertheless remain only 1% Anglo. Despite the

modest objectives of this pilot desegregation program,

Judge Doyle found that the passage of these resolutions

“constituted the first acts of departure from the Board’s

prior undeviating policy of refusing to take any positive

action which would bring about integration of the Park

Hill schools”. 313 F. Supp. at 66.

However, on June 9, 1969, the board, its membership

changed by an election in which integration was the prin

cipal campaign issue (A. 1087a), rescinded the three resolu

tions. The rescission by a 4-3 vote, over the opposition of

the superintendent (A. 241a) occurred as soon as the new

board members took office. Judge Doyle, after analyzing

the effect of rescission on each of the affected schools, con

cluded that the only purpose of rescission was the perpetu

ation of segregation:

This action was taken with little study and was not

justified in terms of educational opportunity, educa

tional quality or other legitimate factors. The only

stated purpose for the rescission was that of keeping

faith with the will of the majority of the electorate.

17

The effect of the rescission was to restore and per

petuate the status quo as it existed in northeast Denver

prior to the passage of Resolutions 1520,1524 and 1531.

This status quo was one of segregation at Barrett,

Hallett, Stedman and Smiley. 303 F. Supp. at 295.

Although the main focus of the resolutions was aimed at

only eight minority schools (Barrett, Stedman, Hallett,

Park Hill, Philips, Smiley, Cole and East) they neverthe

less involved 37.6% of all black students in the school

system. Smiley and Cole enrolled 68.9% of black junior

high students. East had 42% of black high school pupils.

A chart showing the effect of the implementation of re

scission of the resolutions on the attendance pattern of

these schools, plus the 23 other schools involved in receiv

ing transferred students under the three resolutions, is

attached to the Tenth Circuit’s opinion. See 445 F.2d at

1008. We point out in footnote 13 below the relation of

the schools found to be deliberately segregated to the

system as a whole.18

13 The board was found guilty of intentional segregationist acts

of one kind or another with respect to the schools listed below. (As

to Cole and East the conclusion rests on the rescission of Resolutions

1520 and 1524).

P u pils— 1968-1969

Anglo Negro Hispano Total

B arrett .............................. 1 410 12 423

Stedman ............................ 27 634 25 686

Hallett ............................. . 76 634 41 751

Park Hill .......................... 684 223 56 963

P h ilip s ................................ 307 203 45 555

Smiley Jr. High .............. 360 1112 74 1546

Cole Jr. High .................. 46 884 289 1219

E ast H ig h .......................... 1409 1039 175 2623

Subtotal elementary.. 1095 2104 179 3378

Subtotal Jr. High .... 406 1996 363 2765

Subtotal Sr. High .... 1409 1039 175 2623

Total .................. 2910 5139 717 8766

( continued )

18

B. The Manner in W hich School Authorities’ Decisions

Have Determined the Racial Composition of Schools.

The record indicates the variety of decisions by which

school authorities control the racial composition of schools

in Denver. This control over racial composition has been

purposefully exercised, according to the findings below,

even during periods when the board asserted it was color

blind in such matters. The control appears in routine de

cision-making at the administration level, and in major

and minor decisions by the elected school board.

It should be noted that there has been substantial con

tinuity in administrative control of the Denver system for

many years. Dr, Oberholtzer served as Superintendent

from 1947-1967. A. 1300. The present Superintendent How

ard Johnson (1970 to date) served as Deputy Supt. during

Oberholtzer’s tenure and remained in that position during

Supt. Gilberts’ tenure (1967-1970). Mr. Johnson was re

sponsible for teacher placement and attendance bound

aries during the years involved in the lawsuit. A. 256a-257a,

The findings below relate to decisions about such things

as (1 ) the location of new schools and additions to schools,

(2) the size of schools, (3) the utilization of schools, (4)

the drawing of school attendance boundaries, (5) the use

of optional zones, (6) the use of transfer plans, (7) the

The total black sehool enrollment in 1968 was:

Elementary 8297

Jr. High 2893

Sr. High 2442

Thus the above-mentioned schools included:

Elem entary— 25.36% of all black elem. pupils

J r. High — 68.99% of all black Jr. High pupils

Sr. High — 42.55% of all black Sr. High pupils

Total — 37.69% of all black pupils

Source: P X 242, 243, 273, 274, 302, 303; A. 2050a; A. 2053a- A

2072a; A. 2074a; A. 2078a; A. 2080a.

19

use of mobile classrooms, (8) the maintenance of trans

portation programs, (9) the composition of school facul

ties, (10) the differing educational programs offered at

schools.

The record in this case shows that where race was an

issue each type of decision was invariably made in Denver

so that the result was racial segregation. For a decade

before the suit was filed the court found they were made

for the purpose of segregating. Yet the courts below found

the system guilty of unlawful segregation practices only

in those cases where the asserted justification for action

was shown to be “a sham or subterfuge to foster segrega

tion.” 445 F.2d at 1000. Wherever the board could show

any “rational neutral criteria segregative intent will not

be inferred.” Id. Indeed, the district court refused to

find unlawful segregation in cases where it thought “the

result is about the same as it would have been had the

administration pursued discriminatory policies, since the

Negroes, and to an extent the Hispanos as well, always

seem to end up in isolation.” 313 F. Supp. at 73. But,

even with this strict burden of proof, which petitioners

protest as too onerous, the Denver system was found to

have engaged in a decade-long segregation policy affect

ing a substantial portion of the black community.

1. Assigning Faculty by Race.

As described at pp. 11-13 above, the school district

admitted to a long time practice of assigning minority

teachers to schools with minority children. The District

Judge found that this practice “helped to seal off these

schools as permanent segregated schools.” 303 F. Supp.

at 284-85. He also found that the reason for the practice

was racial prejudice or more precisely that the reluctance

to place minority teachers in white schools was because of

20

“concern over a possible lack of acceptance by the white

community and because of a fear of lack of support by

some faculties and principals.” 303 F. Supp. 284.

The findings of unlawful segregation at Barrett (52.6%

Negro teachers) and Smiley Jr. High (23% Negro teachers)

were expressly related to the faculty assignments by race.

303 F. Supp. at 290, 294. Schools where black teachers were

concentrated in heavily disproportionate numbers were

invariably schools where black pupils were concentrated.

See PX 318, A. 2083a; PX 258, A. 2059a; and DX-DG-,

A. 2146a, showing percentage of Negro teachers 1964-

1968 in elementary schools with faculties 20% or more

Negro. The percentage of black teachers at Barrett, Hal-

lett, Smiley and Cole was actually greater in 1967 and

1968 than it was five years earlier when the board an

nounced a policy of assigning minority teachers outside

minority schools. A. 337a-38a.

The policy of assigning minority teachers to minority

schools was in effect when Dr. Oberholtzer became super

intendent in 1947 and continued in following years.14 * Dur

ing the period when the board said it thought itself legally

bound to be “color blind” in pupil assignments it never

theless continued assigning black teachers to schools with

black pupils. The board’s policy was that a teacher’s res

idence should have nothing to do with the teacher’s school

assignment, nor was it a reason for granting teacher

transfers. A. 285a.

Negro principals were also assigned only to minority

schools. The Voorhees Committee reported in 1964:

14 The first Negro teacher in Denver was hired at W hittier Ele

mentary school in 1934. From 1934 to 1944 there were never more

than five Negro teachers in the system and all were assigned £o

W hittier. By 1954 there were 43 Negro teachers in the system all

assigned to minority schools. See PX 410, A. 2106a.

21

“At present, Denver’s two Negro principals two

Spanish-American assistant principals, one Negro as

sistant principal and one Negro teacher-assistant are

assigned to schools in minority neighborhoods. (Two

Negro coordinators and one Japanese-American as

sistant principal are not so assigned.) The Committee

sees no acceptable reason why administrators with

minority background should continue to be assigned

to schools where minority students predominate.” PX

20, pp. D-17-18.

2. Size and Location of School Buildings; Additions to

Buildings; Capacity Utilisation; Mobile Classrooms.

The racial composition of schools in the system was

determined by interrelated decisions about such matters

as the location of new schools, the construction of added

space at existing schools by new permanent or mobile

classrooms, and decisions to overcrowd15 or under-utilize

existing school capacities. For example, the district court

found that Barrett elementary school was built in a par

ticular location “with conscious knowledge that it would

be a segregated school.” 303 F. Supp. at 285. Barrett

was built as a small school on a large site with its size

designed to fit the number of black pupils in the area

without providing any room, for pupils from an over

crowded white school a few blocks away:

“At the time Barrett was built Stedman School, in

a predominantly white area, and located a few blocks

east of Barrett, was operating at approximately 20

percent over capacity. Yet Barrett was built as a 16

16 Sometimes the decision would be made to use double sessions in

a school to keep the children in their neighborhood. A. 1180a. Some

times the school day was “extended” to increase capacity. A. 375a.

22

relatively small school and was not utilized to relieve

the conditions at Stedman.” 303 F. Supp. at 285.

Manual Training High School was built in 1953 as the

smallest high school in the city (it still is) to accommo

date the predominantly Black and Hispano population in

the central city area. A. 1404a. It was admittedly de

signed to serve the minority community as Dr. Oberholtzer,

then Superintendent, testified:

Q. Now, first of all, with respect to the building of

new Manual, it’s true, is it not, Doctor, that Manual

High School today is the smallest high school in the

district? A. It is the smallest senior high school, yes.

Q. And it was at the time it was built, also, was

it not? A. I believe it was, yes.

Q. Why was Manual built so small, Doctor! A.

Are you talking about new Manual or old?

Q. New Manual. A. The new Manual was built in

the same general location as the old Manual and sub

stantially the same attendance area. That was the

reason.

Q. It was built to serve a particular community? A.

The community in that area, yes.

Q. What was the composition of that community,

Doctor? A. Negro and Anglo, largely; some Hispano.

Q. Well, you recall, do you not, Doctor, that as early

as, I believe it’s 1950-1951, that Manual was already a

predominantly minority school, do you not, about 40

percent black, 35 percent Hispano, 25 percent Anglo?

A. Somewhere in that neighborhood.

Q. And I assume that that neighborhood that new

Manual was to serve wasn’t getting any whiter between,

say, 1951 and ’53 when new Manual was opened? A.

No.

23

Q. It was becoming blacker, was it not1? A. There

was some tendency, yes, to that.

Q. Well, it’s true, isn’t it, that when the new Manual

opened, Doctor, it only had 77 Anglos in it?

Mr. Brega: Your Honor, I object to this line of

testimony. In 1953—that was prior to Brown and

at that time the law in the country was separate but

equal. That was all right. If that were the case in

Denver, that would not have been unconstitutional at

that time. I think it’s moot and not relevant to the

the issues.

The Court: Well, I think that we have been per

mitting inquiry into the history of this for various

purposes. So we will not draw the line at this point.

The Witness: Would you repeat the question,

please?

Mr. Greiner: Would the reporter read it, please?

(Question read by the reporter.)

A. I do not recall that figure.

(A. 1404a-1405a.)

In 1949, 76% of Denver’s Negro high school students

(278 of 363) attended old Manual High School; by 1956,

84% of them (541 of 641) attended new Manual. A. 499a-

500a; PX 401. A school board publication makes it clear

that new Manual was designed to be a predominantly mi

nority school to replace the old school of the same name

PX 356, A. 2086a, “The New Manual” :

“S ome B asic P boblems to B e P aced

I n P lanning a N ew Manual

There was little doubt when it became known that

Manual would be on the “must” list of the new build

ings that Manual could not be just a high school cut

24

from a general pattern. Manual is different. The col

lege preparatory function of a high school is not the

first consideration in Manual although it has not been

neglected for those boys and girls who do go to college.

For roughly three-fourths of the student body college

is virtually an impossibility.

The usual problems faced by youth are sharpened for

the many Manual boys and girls who are members of

minority groups. Since 1926 the Anglo population at

Manual has dropped from over eighty per cent to about

forty-one per cent; the Negro population has gone

from ten to twenty-seven per cent; the Spanish-Ameri

can figure has risen from less than one per cent to

twenty-three and one-half per cent; and the Oriental

has gone from seven-tenths of one per cent to eight

per cent. These boys and girls have needs which the

school must meet in order to prepare them for effec

tive participation in the community. The chart follow

ing shows the changing racial distribution in Manual.”

The district court’s decision about plaintiffs’ complaint

that Manual was “earmarked for minority occupants” was

that “we have to be mindful of the evidence that it was

opened in 1953 at a time prior to Brown v. Board of Edu

cation . . . , and we are told that this location had the

consent of the people in the neighborhood.” 313 F. Supp.

at 69-70. The court said: “At that time there was much less

concern about minority concentration.” 313 F. Supp. at 70.

Control of racial composition by decisions as to capacity

utilization is also illustrated by Manual which was operated

under capacity from the time of its opening in 1953, al

though nearby East High School with only 2% Negro

enrollment was “filled to capacity.” 313 F. Supp. at 70.

School capacities were controlled by adding mobile class

rooms to expand some crowded buildings. This became a

25

general practice in northeast Denver where there was a

large migration of blacks in the 1960’s and 28 mobile class

rooms were erected to accommodate the black pupils.16

Mobile classrooms were used almost exclusively at black

schools in the northeast Denver area. A. 106a. Capacities

at Stedman and Smith were systematically controlled by

the periodic addition of mobile units to contain the blacks

in the area.

Mobile units and new classrooms were added to Hallett

beginning in 1965 to “solidify segregation.” 17 Mobile units

were added to Smith with similar results.18

3. Transportation Policies.

Denver has used its transportation system as an alternate

means of dealing with the lack or shortage of facilities in

particular neighborhoods, and this has necessarily had an

impact on the racial composition of schools. The established

policy was to make free transportation available to ele

mentary pupils who lived more than a mile from their

assigned schools. A. 1188a. In 1968 the school system sup

16 “The building of 28 mobile units in the Park Hill area in 1964

(at the time there were only 29 such units in all of Denver) resulted

in a further concentration of Negro enrollment in Park Hill schools.

The retention of these units on a more or less permanent basis

tended to continue this concentration and segregation.” 303 P.

Supp. at 285. See PX 101; PX 73, 74.

17 “In 1965 four mobile units were constructed at Hallett. Shortly

thereafter, the Board also approved the construction of additional

classrooms. A t this time Hallett" was approximately 75 percent

Negro. The effect of the mobile units and additional classrooms was

to solidify segregation at Hallett increasing its capacity to absorb

the additional influx of Negro population into the area.” 303 F.

Supp. 293.

18 When the school became overcrowded Smith parents were

offered a choice between adding mobile units a t Smith or being

bussed possibly back to black core city schools. A. 691a-694a, 696a-

697a.

26

plied transportation to 1184 Negro and Hispano children

(6% of minority elementary children) and 4,369 Anglo

children (about 13% of Anglo elementary children). A.

775a. In 1969-70 the Superintendent said about 12,000

pupils were bussed and that the board’s “pay-as-you-go”

policy for financing new construction necessitated much of

the busing in newly annexed areas. A. 1755a.

Basically in southeast and southwest Denver, Anglo

pupils in newly annexed areas of the city were bussed to

the nearest Anglo school which had available capacity.19

A.. 1183a-1184a. Before the lawsuit, no Anglo students

were bussed to any predominantly minority schools.

A. 1203a. The school administration policy was not to bus

pupils into schools classified as the poverty area, target

area or culturally deprived area under federal programs.

A. 1205a-1206a.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 390-A and 390-B are large maps (de

scribed in testimony at A. 767a-775a) which show that the

school system bussed numbers of Anglo students past

under-utilized minority schools.

Anglo pupils were bussed as far as ten miles before the

lawsuit, some of the longest distances being from South

west Denver to Asbury, University Park, Steele and Cory.

A. 375a. Exhibit 390 shows that in many cases students

who were being transported were not being taken to the

nearest school which had capacity to absorb them. One

of the more striking examples of this was the transporta

tion in 1967 and 1968 of junior high school children from

the Montbello area to Lake Junior High School. These

children who live in the northeasternmost corner of the

city were being transported past Cole Junior High School,

19 The District did not employ mobile units to increase the ca

pacity of schools which were even closer to the annexed areas.

PX 101.

27

which was under-utilized, to the western edge of the city.

PX 426. The Montbello children were predominantly

Anglo, and Cole’s membership was predominantly Negro.

In this case a neighborhood or distance principle was not

enforced.

Judge Doyle noted that the three 1969 resolutions con

templated the use of transportation facilities to promote

desegregation. In ordering that the three resolutions be

implemented he noted that “the board has had for many

years and now has a policy of transporting students who

live a certain distance from their schools,” and thus trans

portation was “probably necessary in order to carry out

this decree, but nothing in this order shall be construed

to require the Board to use such transportation if it can

be dispensed with.” 303 F. Supp. at 296.

The court’s final decree requiring integration of various

schools contemplated that detailed plans about such mat

ters as transportation requirements would be submitted

to the court at a later date. In fact, the board did submit

various transportation plans in considerable detail at a

hearing which occurred in May 1971 while the case was

pending on appeal.20

20 The transcript of this hearing commencing May 14, 1971 was

not before the court of appeals because it took place while the

appeal was under advisement. However the transcript has been

lodged with the Clerk of this Court so that the Court may have

access to all available materials about the case which may be rele

vant. Judge Doyle concluded that the board’s Plan C as modified

by the suggestions of plaintiffs’ counsel should be adopted. May

1971 Tr. p. 445. The original Plan C would have required trans

portation for an estimated 3,919 pupils to desegregate the seven

minority elementary schools in the first year of the plan. The esti

mated cost was $823.80 per day or about 21 cents per child per

day. (See Report, Alternative Plans for Implementation of United

States District Court Orders Stated in the P inal Decree of June 8,

1970, Denver Public Schools, March 17, 1971, p. 51.)

28

4. Establishing and Changing School Attendance

A rea s .

The general practice in Denver was to hold public hear

ings and have formal board action only on secondary at

tendance boundaries and to permit the administrative staff

to fix elementary school attendance areas or sub-districts

without public hearings or detailed board attention. A. 117a;

A. 901a. An important but unexplained exception to this

general practice was the fact that various elementary bound

aries in northeast Denver involved in the court’s finding

of deliberate segregation during the 1960’s were set by

the school board. A. 173a; 303 F. Supp. at 291. One con

sequence of the staff making elementary school zone changes

is that many such changes did not appear in minutes of

the school board, and for the years prior to 1960 only a

few maps were still available at the time of the trial.

A. 842a. Thus the parties engaged in attempting to recon

struct boundary maps for years prior to about 1960, ex

cept for the 1956-57 boundary changes. A. 842a-857a;

481a-484a.

The district court’s findings of deliberate fixing of bound

ary lines for the purpose of segregating Negroes from

whites related to (1) the original boundaries set when

Barrett was opened in 1959 (303 F. Supp. at 290; PX 40,

41; A. 2021a; A. 2022a) ; (2) 1962 and 1964 boundary deci

sions affecting Stedman (303 F. Supp. at 291; PX 50, 53,

70, 71; A. 2024a; A. 2026a; A. 2028a; A. 2030a); (3) various

actions during the 1960’s maintaining Park Hill and Philips

as Anglo schools (303 F. Supp. at 292); (4) 1962 boundary

By the 1970-71 school year the system was transporting 12,500

pupils daily on 134 school buses, including busing of handicapped

pupils, pupils in newly annexed areas, pupils more than one mile

from elementary schools or more than two miles from junior high

schools, pupils in crowded areas, pupils under the court orders of

1969 and 1970 and pupils on instructional excursions {Id. at 6-7).

29

decisions relating to Hallett-Philips and 1964 decisions

relating to Stedman-Hallett and Hallett-PMlips (303 F.

Supp. 293); (5) rescission of the 1969 proposed boundary

changes for Smiley and East (303 F. Supp. 294).

Plaintiffs offered evidence trying to prove discrimination

in the fixing of various other boundaries which is sum

marized in the district court opinion at the pages indicated

hereinafter: (1) original boundaries between New Manual

and East High schools 1953, and changes in 1956 (313 F.

Supp. at 69-70, 75); (2) Cole and Smiley Jr. High schools

boundary change in 1956 (similar to Manual-East change

at same time; 313 F. Supp. 70-71, 75); (3) Cole, Morey

and Byers junior high school changes in 1962 (313 F. Supp.

71-72, 76); (4) Boulevard school boundary change 1961

(313 F. Supp. at 72, 76) and Columbine zone changes

1962 (313 F. Supp. at 72-73, 75-76). We summarize the

evidence as to Manual, Cole and Columbine.

Manual. The eastern boundary of Manual in 1953 was

set one-half block from the building. PX 203; Map of

Manual Boundaries 1955; A. 2044a. It coincided with the

easternmost Negro residence. As the Negroes moved east

ward, the Manual boundaries were changed with them to

embrace the Negroes as part of the mandatory Manual

area where theretofore the area had been in an optional

Manual-East zone. PX 204, Map of 1956 Manual Bound

aries, A. 2046a. There was widespread concern in the

Negro community about the segregationist effects of the

proposed 1956 Manual changes, and Mr. Lorenzo Traylor,

a black official of the Urban League, organized meetings

with schools officials and community groups to protest the

changes but had no success. His testimony about the

Manual changes and the Cole boundary changes in 1956

shows very plainly that the boundary changes followed the

black population migration eastward, that the school of

30

ficials were made aware of this and that they declined to

adopt alternative proposals that wonld have worked to

integrate Manual and Cole. A. 580a-599a. In summary :

1. When the new Manual was built, its eastern

boundary was only one-half block from the school,

approximating the location of the Negro population.

2. The eastern boundary of Manual was moved east

ward to York Street in 1956 commensurate with the

Negro population movement.

3. This 1956 change occurred after widespread com

munity concern that it would be a segregatory change.

4. During the relevant period Manual was always

under-utilized and no rational justification for this

boundary change on the basis of capacity utilization

exists. PX 210, A. 2048a.

Cole. In 1952 Cole was under capacity and predominantly

black and Hispano while Smiley to the east was over

crowded and still an Anglo school. PX 215, 215A. Rather

than shift the boundaries to relieve overcrowding at Smiley

by adding whites to Cole, the board built additional class

rooms at Smiley. 313 F. Supp. at 71. In 1956 as the black

community moved eastward the Cole boundary was shifted

to follow them, the boundary change being the same as

that described previously for Manual in 1956. Id.; PX 211,

211A, 211B. Again in 1958 another addition was built at

Smiley notwithstanding that Cole still had empty spaces.

Id.; PX 215, 215A. These changes were opposed by the

black community, and Mr. Traylor of the Urban League

offered the board boundary proposals which would have

the effect of integrating the schools to no avail. A. 580a-

599a. PX 333, A. 2118a. This was during the period when

the board asserted that it was not lawful for it to consider

31

race for the purpose of integrating students. A. 1370a-

1371a.

Columbine. The hoard established a series of optional

zones around Columbine in 1951 which increased the Negro

enrollment because it set up options which “were appar

ently employed by Anglo students as a means of escaping

from Columbine to the almost totally Anglo Harrington

and Stedman.” 313 F. Supp. at 72-73; PX 406, 407. Al

though the asserted purpose was to relieve overcrowding

at Columbine the court found that actually “the effect of

the administration’s action was to slightly decrease over

crowding at Columbine while creating an overcrowded

situation at Harrington and Stedman.” 313 F. Supp. at 72.

5. Optional Zones and Transfer Devices.

The board has employed a variety of devices which have

enabled parents to choose schools so as to achieve racial

separation. Optional zones located in the border areas of

mixed racial population between white and black schools

functioned as an effective device to accommodate segrega

tionist sentiment among the public. The two optional

zones between East and Manual defined the racially mixed

neighborhoods, and as soon as a neighborhood became all

black it was shifted from an optional zone to a mandatory

part of the Manual zone—-Traylor testimony at A. 580a-

592a; PX 203, 204; A 2044a; A. 2046a.

The use of optional areas for whites to escape black

students at Columbine is discussed in the preceding section.

The Cole-Smiley optional zone was identical to the Manual-

East optional area. A. 502a-503a; PX 211, 211A, 212,

212A.

The Voorhees Committee Report denounced the board’s

use of optional areas and recommended that the board im

32

mediately stop the practice “at the earliest possible date.”

PX 20, pages A-12 to A-13; A. 2013a. The report stated

that the “use of optional areas forms no part in rational

administration of the system for fixing boundaries which

the Committee has recommended” Id. After this report

the board eliminated the last optional zones in 1964 (A.

1347a), but in September 1964 instituted a Limited Open

Enrollment (LOE) program which gave pupils freedom

of choice to transfer out of the schools in their attendance

zone to certain schools which were designated as open to

LOE transfers. A. 299a; 304a.

Under LOE a student could transfer to any school where

openings were listed as available but the student had to

furnish his own transportation. There were in 1968 only

365 LOE spaces open at the elementary level. A. 541a;

PX 87, 89, 90; A. 2032a; A. 2034a; A. 2036a. No priority

was given to transfers that would promote integration nor

was there any prohibition against transfers that would

tend to promote segregation. Plaintiffs’ evidence showed

that the LOE program involved only about 267 elementary

students out of 50,000 (A. 538a). It had negligible effect

toward integration—a maximum of 29 pupils—while an

estimated 58 to 77 white pupils left black schools to at

tend white schools. A. 538a; PX 99, 100. Plaintiffs showed

that 10 Anglo schools which were under-capacity and re

ceiving Anglo pupils by bus were not on the list report

ing LOE openings. A. 539a-540a; PX 89, A. 2034a. Seven

predominantly minority schools with an overall Anglo per

centage of only 12 percent contained over 55 percent of

the available LOE spaces (203 of the 365 elementary open

ings in the district). A. 541a; PX 90, A. 2036a. Although

objective data shows that the white schools had space avail

able, the principals were not reporting space as open for

LOE purposes. PX 89, A. 2034a; PX 87, A. 2032a.

33

The Voluntary Open Enrollment (VOE) program adopted

in the fall of 1968 and implemented in January 1969 was

offered as an integration program. Shortly after the Board

announced the program a group of white parents formed

the idea of targeting Hallett school as a black school which

might be integrated if a sufficient number of whites could

be organized to volunteer to transfer in and an equiva

lent number of blacks could be organized to transfer out.

A. 665a-683a. Their initial efforts were rebuffed by Deputy

Supt. (now Supt.) Howard Johnson, who stated they had

no duty to promote the VOE program but merely to make

it available. A. 675a. Later in Resolution 1531 (April

1969) the board endorsed the idea of making Hallett a

“demonstration integrated school as of September 1969,

by use of voluntary transfer”. A. 68a. After an intensive

summer recruitment program (A. 687a-691a), VOE helped

to change Hallett from 84% black in 1968 (Anglo pupils—

76, black 634, Hispano 41) to 58.4% black in 1969-70 (An

glo pupils 290, black—444, Hispano—22). About 1500

pupils were involved in the VOE program in the entire

city. A. 1769a. At the relief hearing in May 19701 the board

offered its VOE program as the sole remedy to achieve

integration. Judge Doyle, while permitting the VOE pro

gram to continue, refused to permit the Board to limit

its integration program to this one technique. 6

6 . Curriculum, Level of Instruction and the Atmosphere

of Segregated Schools.

Manual Training High School was planned prior to 1953

to offer a curriculum designed for minority and other low

income students. See supra pp. 23-24. Manual was planned

as a lower caste school to meet the “special needs” of lower

income and minority pupils about whom it was noted that

“Fewer pupils got to college,” “Fewer take college pre

paratory subjects,” “More go to work immediately” and

34

“More go into unskilled and semiskilled labor.” PX 356;

A. 2086a. Such prophecies of course have a, way of becom

ing self-fulfilling, and people who want to avoid the mold

will try to avoid the school. Robert O’Reilly, one of plain

tiffs’ expert witnesses called this sort of thing “program

ming students into basically lower occupations than the

whites are programmed into.” A. 1964a.21

The community perception of Manual and its feeder

school Cole Junior High was negative. The feeling in the

black community was that Manual was a substandard school

and that the quality schools were in other parts of the City

according to George Brown, a black State legislator and

former local newsman covering education subjects. A. 865a.

The dropout rate was high and “even the name had its nega

tive connotation” he said. A. 865a. Manual’s black prin

cipal was aware of the community resentment toward the

school and of the reluctance of employers to hire Manual

graduates. A. 1847a. He attempted many program inno

vations, but acknowledged that Manual students scored in