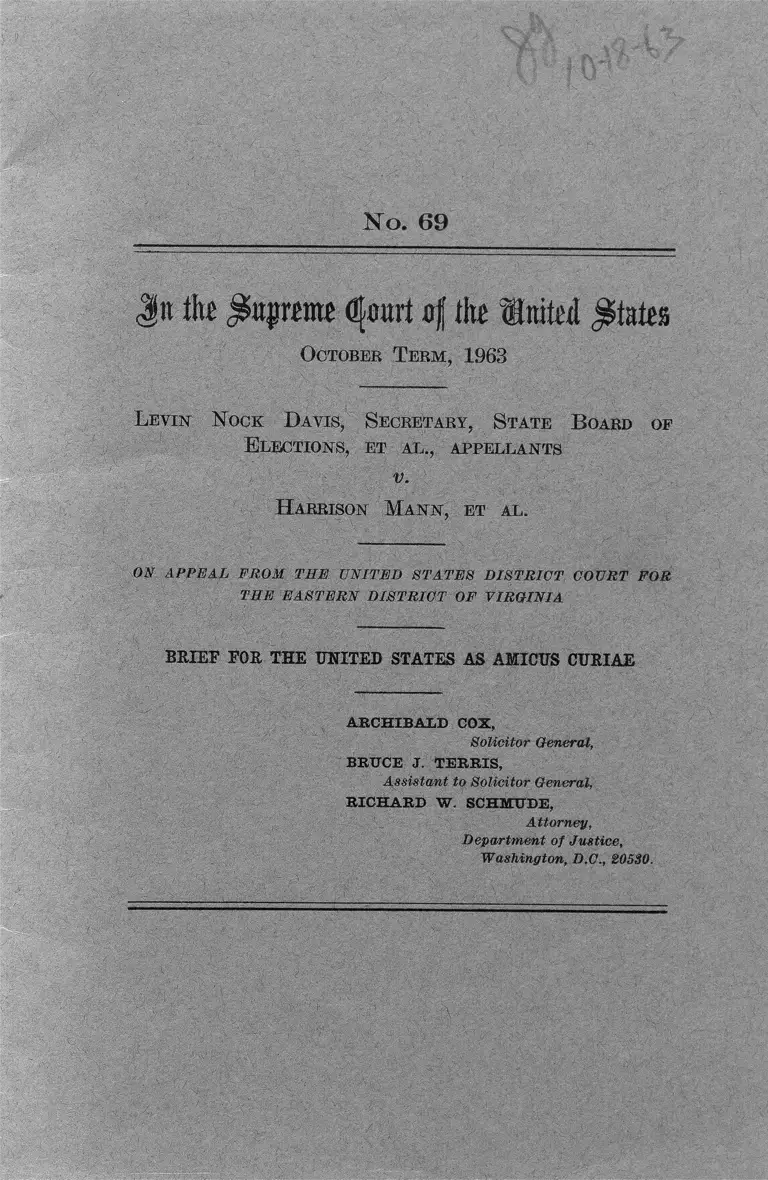

Davis v. Mann Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Mann Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1963. 49d7b052-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/efbdd14a-b032-470a-ac80-f73442cded7b/davis-v-mann-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 69

Jit the Supreme Qfmtrt of (Ik ittilwl States

October Term, 1963

L evin N ock D avis, Secretary, State B oard op

Elections, et al., appellants

v.

H arrison M an n , et al.

ON APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

A R C H IB A L D COX,

Solicitor General,

BRUCE J. T E R R IS ,

Assistant to Solicitor General,

R IC H A R D W . SCHM UDE,

Attorney,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C., 205S0.

P !S

I N D E X

Opinion below-----------------------------------------------------------------

Jurisdiction-------------------------------------------------------:--------------

(Questions presented---------------------------------------------------------

Constitutional provisions and statutes involved--------------

Interest of tlie United States------------------------------------------

.Statement__________________________________ - —7-------------

1. The pre-hearing proceedings in the district court-

2. The evidence before the district court-----------------

3. The decision and decree of the district court-------

Argument:

Introduction and summary---------------------------------------

I. The district court correctly proceeded to

an adjudication of plaintiffs" constitutional

claims--------------------------------------------------------------

A. The district court properly refused to.

postpone an adjudication pending a

state determination of the issues------- -

B. Even when abstention is appropriate, a

district court should retain jurisdic

tion to adjudicate the claims o f federal

constitutional right------------------------------

I I . Virginia’s legislative apportionment violates the

Fourteenth Amendment by grossly discrimi

nating against the people of Arlington and

Fairfax counties and the City o f Norfolk with

out rhyme or reason---------------------------------------

A. The Virginia apportionment seriously

discriminates against the voters in

Arlington and Fairfax counties and in

the City of Norfolk------------------------------

B. The gross discrimination is based upon

no intelligible policy---------------------------

•'Conclusion-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Appendix A ------------------------------------------------------------- ------

Appendix B ------------------------------------------------*-------------------

(1)

Page

1

1

2

2

2

Ot)

4

5

9

12

14

14

26

29

30

33

49

51

59

709- 361— 63--------------- 1

II

C I T A T I O N S

Cases: Fage

Albertson v. Millard, 345 U.S. 242__________________15,26

American Federation o f Labor v. Watson, 327

U.S. 582___________________________________________15,26

Armstrong v. Mitten, 95 Colo. 425, 37 P. 2d 757____ 48

Asbury Park Press, Inc. v. Wooley, 33 N.J. 1, 161

A. 2d 705_______________________________________ 48

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186_____________________12,14, 30

Borden’s Farm Products Go. v. Baldtoin, 293

U.S. 194__________________________________________ 48

Brooks v. State, 162 Ind. 568, 70 N.E. 980__________ 48

Browder v. Gale, 142 F. Supp. 707, affirmed, 352

U.S. 903_________________________________________ 20

Brown v. Saunders, 159 Va. 28, 166 S.E. 105________ 23

Burford v. Ntm CiZ Co., 319 U.S. 315_____________ 27

Chicago v. Fieldcrest Dairies, Inc., 316 U.S. 168_15,16,26

Golegrove v. Green, 328 U.S. 549___________________28,29

Cook v. Fortson, 329 U.S. 675________________________ 29

Denny v. State, 144 Ind. 503, 42 N.E. 929__________ 48

Dyer v. Kazuhisa Abe, 138 F. Supp. 220_________ 16,20

Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U.S. 464___________________ 47

Government and Civic Employees Organizing Com

mittee v. Windsor, 353 U.S. 364______________ 15,16, 26

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368______________________ 33

Harrison v. National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People, 360 U.S. 167_____15,17,18,26

Hartford Co. v. Harrison, 301 U.S. 459____________ 48

Hawks v. Ha-mill, 288 U.S. 52_____________________ 27

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268---------------------------------- 20

Lassiter v. Northampton County Board o f Elections,

360 U.S. 45______________________________________ 18

Lein v. Sathre, 201 F. Supp. 535___________________ 16

Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U.S. 61__ 47

Louisiana Power <§ Light Co. v. City of Thibodaux,

360 U.S. 25_____________________________________ _ 12,26

Maryland Committee for Fair Representation v.

Tawes, No. 29, this Term--------------------------- 2,12.16, 23

Matthews v. Rodgers, 284 U.S. 521___________________ 27

McNeese v. Board o f Education, 373 U.S. 668______12,19

Mitchell v. Wright, 154 F. 2d 924___________________ 21

Monroe, v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167----------------------------------- 17

Ill

Moss v. Burkhart, U.S.D.C., W.D. Okla., decided Page

July 17, 1963__________ ___________________________ 16

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People v. Button, 371 U.S. 415___________________ 18

Parker v. State, 133 Ind. 178, 32 ISLE. 836__________ 48

Pennsylvania v. Williams, 294 U.S. 176____________ 27

Ragland, v. Anderson, 125 Ky. 141, 100 S.W. 865_____ 48

Railroad Commission v. Pullman Co., 312 U.S. 496__ 16, 26

Reynolds v. Sims, Nos. 23, 27, 41, this Term__________ 24,48

Rice, E x parte, 143 So. 2d 848_____________________ 24

Rogers v. Morgan, 127 Neb. 456, 256 N W . 1_______ 48

Romero v. Weakley, 226 F. 2d 399___________________ 20

Royster Guano Co. v. Virginia, 253 U.S. 412________ 47

Scholle v. Secretary o f State, 367 Mich. 176, 116

N.W. 2d 350_______1______ ______________________ 48

Sims v. Frank, 208 F. Supp. 431, pending on appeal

sub. nom. Reynolds v. Sims, Nos. 23, 27, 41, this

Term_____________________________________________ 48

Spector Motor Service, Inc. \. McLaughlin, 323 U.S.

101___________________________________________ 15, 16, 26

Stainba.ck v. Mo Ilock K e Lok Po, 336 U.S. 368______ 27

Stapleton v. Mitchell, 60 F. Supp. 51, appeal dis

missed sub. nom. McElroy v. Mitchell, 326 U.S. 690_ 21

State ex rel. Attorney General v. Cunningham, 81

Wis. 440, 51 N.W. 724___________________________ 48

State ex rel. Lamb v. Cunningham, 83 Wis. 90, 53

N.W. 35______________________________________ 48

Stiglitz v. Sehardien, 239 Ky. 799, 40 S.W. 2d 315_ 48

Thigpen v. Meyers, U.S.D.C. W.D. Wash., decided

May 3, 1963______________________________________ 48

Toombs v. Fortson, 205 F. Supp. 248______________ 16

Waid v. Pool, 255 Ala. 441, 51 So. 2d 869__________ 24

Wesberry v. Sanders, No. 22, this Term____________ 24

Westminster School Dist. v. Mendez, 161 F. 2d 774_ 21

Wilson v. Beebe, 99 F. Supp. 418___________________ 21

WMCA, Inc. v. Simon, No. 20, this Term_______ 23, 40, 45

Constitutions and statutes:

U.S. Constitution:

Fourteenth Amendment______________________________2,

4,11,12,13, 21, 24, 28, 29, 30, 45,48

Civil Eights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1983, 1988-______________ 4

Page

Georgia Constitution, Art. 1, c. 2-1, Secs. 102, 103------ 24

Virginia Constitution, as amended:

Article 1, Sec. 8________________________________ 22

Article I, Sec. 11------------------ 22

Article IV , Sec. 40__________________________ 2, 22,51

Article IV , Sec. 41__________________________5,22,51

Article IV , Sec. 42------------------------------------------ 2, 5, 51

Article IV , Sec. 43_________________________ 2,6,22,51

Article IV , Sec. 55_____- ______________ 23

Virginia Constitution o f 1864 (Section 6) ----------------- 22

Virginia Acts of Assembly, Chapters 635 and 638

(1962) :

Sec. 24-12______________________________________ 6,54

Sec, 24-14— ____________________________________ 6, 51

Virginia Code:

24 Va. Code 17___________________________ 2, 34,56

24 Va. Code 18_______________________________2,34, 57

24 Va. Code 19_______________________________2,34,58

24 Va. Code (1962 Supp.) 23.1______________ 2,34,57

Miscellaneous:

Chafee, Bills of Peace with Multi f ie Parties. 45

Harv. L. Rev.' 1297__________________ 19

Department of Commerce, County and City Data

Booh, 196%_______________________________________ 42

IV

J it fltt j&ajiramt flfottrt of the I n t e l states

O cto ber T e r m , 1963

No. 69

L e v in N o c k D a v is , S e c r e t a r v , S t a t e B oard of

E l e c t io n s , e t a l ., a p p e l l a n t s

v.

H a r r is o n M a n n , e t a l .

ON A P P E A L FROM T E E UNITED STATES D IST R IC T COURT FOR

T E E E ASTERN D IST R IC T OF V IRG IN IA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

O PIN IO N BELOW

The opinion of the three-judge district court (R.

57-79) is reported at 213 F. Supp. 577.

JU R ISD IC T IO N

The order of the district court was entered on No

vember 28, 1962 (R. 79). The notice of appeal to this

Court was filed on December 10, 1962, and probable

jurisdiction was noted on June 10, 1963 (R. 81, 83).

The jurisdiction of this Court rests upon 28 TI.S.C.

1253.

(i)

2

QUESTIONS P R E SE N TE D

1. Whether the federal district court, instead of

deciding the constitutionality of the apportionment

of Virginia’s legislature under the Fourteenth Amend

ment, should have either dismissed or stayed the pro

ceedings to allow a suit to be brought in a State court

in order to decide State issues.

2. Whether the apportiomnent of the Virginia

legislature violates the equal protection clause because

it discriminates against voters in Arlington and Fair

fax Counties and the City of Norfolk without rhyme

or reason.

CO N ST ITU T IO N A L PR O V IS IO N S A N D ST A T U T E S IN V O L V E D

Sections 40 to 43 of Article IV of the Constitution

of Virginia are set forth in Appendix A, p. 51.

Chapters 635 and 638 of the Virginia Acts of As

sembly for 1962 are set forth in Appendix A, pp. 51-56.

Sections 17-19 and 23.1 of 24 Virginia Code are set

forth in Appendix A, pp. 56-58.

IN T E R E S T OE T H E U N ITED ' STATES

This is one of four cases pending argument on the

merits in which the Court will be called upon to

formulate under the Fourteenth Amendment the con

stitutional principles applicable to challenges to mal

apportionment of a State legislature. The United

States has filed its principal brief in Maryland Com

mittee for Fair Representation v. Tawes, No. 29, be

cause that ease presents a greater variety of issues.

There, we presented a compendious analysis of the

substantive issues in all four cases showing their

relation to each other. Substantively, the instant case

raises the specific problem of the validity of discrim

3

ination in per capita representation against the citi

zens of three areas without any rational justification

whatever. Procedurally, the instant case raises ques

tions concerning the relationship between federal and

State forums in the adjudication of such constitutional

issues.

Individually and collectively, these cases present

issues of great importance to millions of American

citizens seeking full and fair participation in their

State governments. This is the primary basis of the

government’s interest.

ST A T E M E N T

The plaintiffs—four citizens of the United States

and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, who are resi

dents and qualified voters of Arlington and Fairfax

Counties—filed a complaint on April 9, 1962, in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District

of Virginia, in their own behalf and on behalf of all

voters in Virginia similarly situated, challenging the

apportionment of the Virginia legislature (R. 1-31).

The defendants, who were sued in their representative

capacities as officials charged with duties in connec

tion with State elections, include the Governor and

Attorney General of Virginia; three members of the

Virginia Board of Elections; the three members of

the Electoral Boards of Fairfax and Arlington Coun

ties, as representatives of all members of city and

county electoral boards of Virginia; and the Clerks of

the Circuit Courts of Arlington and Fairfax Counties,

as representatives of all of the county and city clerks of

Virginia (R. 1, 3-4). The plaintiffs claimed rights un

der the Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1983, 1988, and

asserted jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. 1343(3) (R. 2).

4

The complaint alleged that the present statute ap

portioning of the General Assembly, as amended in

1962, results in “ invidious discrimination” since-

voters in Arlington and Fairfax Counties are given

substantially less representation than voters residing'

elsewhere in the State (R. 6-7). The plaintiffs as

serted that the discrimination violates the Fourteenth

Amendment as well as the Virginia Constitution.

They contended that the requirements of the Four

teenth Amendment and the Virginia Constitution

could be met only by a re-distribution of legislative

districts among the counties and cities of the State-

“ substantially in proportion to their respective popu

lations” (R. 7-8).

The complaint sought the convening of a three-

judge district court. As relief, plaintiffs asked: (1)

a declaratory judgment that the statutory scheme o f

reapportionment, prior as well as subsequent to the

1962 amendments, contravenes the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and is, there

fore, unconstitutional and void; (2) a prohibitory

injunction restraining the defendants from perform

ing their official duties with respect to the election

of members of the General Assembly pursuant to*

the present statute; and (3) a mandatory injunction

requiring the defendants to conduct the next primaries

and general election for legislators on an at-large

basis throughout Virginia (R. 8-9).

1. The Pre-hearing Proceedings in the District

Court. On April 17, 1962, the Chief Judge of the

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit convened a

three-judge district court. Four citizens of the

United States and Virginia, who are residents and

5

qualified voters of the City of Norfolk, moved on

May 25, 1962, to intervene as intervenor-plaintiffs

against the original defendants and against four ad

ditional defendants, namely, the Clerk of the Cor

poration Court for the City of Norfolk and the three

members of the Electoral Board of Norfolk (R. 32-

43). The application set out the substance of the alle

gations and grounds contained in the complaint and

sought the same relief from the court which the

plaintiffs were seeking (R. 36-43). The applica

tion was granted (see R. 58). On June 20, 1962, the

plaintiffs and intervenor-plaintiffs sought and ob

tained leave to amend the complaint by adding an

.additional prayer for relief that, unless the General

Assembly “ promptly and fairly” reapportioned the

legislative districts, the court should reapportion the

districts so as to accord the parties and others simi

larly situated “ fair and proportionate” representa

tion in the legislature (R. 55).1

2. The Evidence Before the District Court. The

Virginia Constitution provides for a Senate of not

more than 40 nor less than 33 members, and for a

House of Delegates of not more than 100 nor less

than 90 members. Art. IY , Sec. 41, 42 (see Appendix

A., p. 51). At all relevant times, State statutes have

fixed the number of senators at 40 and of delegates

at 100. The constitution also specifies that a reap

portionment must be made at least once every ten

years (Art. IV, Sec. 43). The constitution provides

1 The plaintiffs introduced into evidence two alternate plans

for reapportioning the House of Delegates (R. 105-114, 119-

131) and three alternate plans for the redistricting of the Sen

ate (R. 133-158).

6

no express standards, however, for the apportion

ment of representatives and it also leaves the estab

lishment of the districts to legislation.

The core of the evidence before the district court

is the basic figures showing the population of the sev

eral districts from which senators and delegates are

chosen and the number of senators and delegates as

signed to each. The most convenient tabulation ap

pears at R. 11-24. Prom that data other statistical

comparison were derived. Since the 1962 appor

tionment was enacted only two days before the

complaint was filed and made only a small change

in Virginia Code 21-12, 14, which had been last

amended in 1958, the evidence covers both the pres

ent and last previous apportionments.

Although the conclusions to be derived from the

data are matters of argument, the basic figures make

it abundantly clear that the people of Arlington and

Fairfax Counties and the City of Norfolk suffer from

gross inequalities in per capita representation in both

houses of the Virginia legislature. Since there are 40

senators and Virginia had a population of 3,966,949,

according to the 1960 census, the ideal ratio would be

one senator for 99,174 people. Arlington County has

only one senator for 163,401 people—only 61 percent

of its fair representation. Its voters are the most un

derrepresented in the State. The City of Norfolk

has only 65 percent of its fair share—two senators

for a population of 305,872—making it the second

most underrepresented senatorial district. Fairfax,

with two senators for 285,194 people, is the third

worst represented area with only 70 percent of a fair

apportionment.

/

The inequality is also apparent from the following-

table showing the Arlington, Fairfax and Norfolk

districts in comparison with the most overrepresented

districts as well as other typical areas (R. 18-20):

Senatorial district

Total

population

(1960)

Number

of

Senators

Population

per

Senator

Ratio to

most under

represented

district

Arlington_____________________________ ________ 163,401 1 163,401 1.00

City of Norfolk________________________________

Fairfax---------------------------------------------------------------

305,872

1

2 152,936 1.06

City of Fairfax------------------ --------------------------------

Falls Church_________________ _________________

> 285,194 2 142,597 1.14

City of Richmond------- -------------------------------------- 219,958 2 109,979 1.58

City of Alexandria-------------- -------- ----------------------

Henry---------- ----------- -------------------- --------------------

Patrick-------------- -----------------------------------------------

91,023 1 91,023 1.79

Pittsylvania_______________________ ______ ____

City of Danville____________ — --------------- --------

City of Martinsville____________________________

Bland------ ----------- -------------------------------- ----------- -

. 179,288 2 89,644 1.82

Giles--------------------------- -------- -----------------------------

Pulaski_____________________________ ____ - ........

Wythe____________________ ____ _________ - ........

| 72,434

]

1 72,434 2. 25

Fauquier___________ ________ —-------- ----------------

Loudoun............................... ................. ........ - ........ -

Brunswick_____________________________________

[ 63,703

1

1 63,703 2.56

Lunenburg____________________________________

Mecklenburg------- ----- ---------------------------------------

> 61,730 1 61,730 2.64

State total............... ........................ ................. 3,966,949 40 99,174 1.65

Thus, the ratio between the most overrepresented and

the most underrepresented districts is more than 2%

to 1. Twelve districts have over twice the representa

tion of Arlington County; ten have over twice the

representation of Norfolk; and six have over twice

the representation of Fairfax.1*

The same discrimination against the people of

Arlington and Fairfax Counties and the City of Nor-

la In mailing such calculations, we have considered overlapping

districts as one large district. For example, under the appor

tionment before 1962, Amhurst County (population 22,953) and

the City of Lynchburg (population 54,190) together had a dele

gate, Lynchburg alone had a delegate, and Nelson (population

12,752) and Amhurst Counties had a delegate. We have con

sidered all three as composing one district with a population of

90,595 and three delegates.

8

folk is apparent in the figures relating to the House

of Delegates. Fairfax, the third most underrepre

sented district in the Senate, is the most underrepre

sented in the House of Delegates, having only 42 per

cent of the ideal representation. Arlington, the most

underrepresented district in the Senate, is the fifth

most underrepresented district in the House, with

only 73 percent of its fair share. The City of Nor

folk is the sixth most underrepresented district in the

House of Delegates, with 78 percent of its fair repre

sentation.

The discrimination in the House of Delegates is

also apparent from the following table comparing

Arlington and Fairfax Counties and the City of Nor

folk with the most overrepresented districts and other

typical districts (R. 21-24) :

House district

Total

population

(1960)

Number of

delegates

Population

per

delegate

Ratio to

most

underrep

resented

district

Fairfax Comity___________________________

City of Fairfax. _____ _______ ___________________ [ 285,194 95,064 1.00

City of Falls Church__________________________

Chesterfield.. _____________________ ______ ____

City of Colonial Heights____ ____ ______________

1

J 80,784 1 80,784 1.17

A rlington...____ _____ ____ ____________________ 163,401 3 54,467 1.74

City of Norfolk____________ ____ _______________ 305,872 6 50,978 1.86

City of Newsport News________________________ 113,662 3 37,887 2.50

W ise._____ ______ _____________________________ | 74,416 2 37,203 2. 55

City of N orton.._____ ______________ _____ _____

City of Petersburg_____________________________

Dinwiddie........ ................. ............................. .......... J 58,933 2 29,466 3. 22

Pittsylvania_____ _______________ ____________ _ 58,296 2 29,148 3. 26

Rockingham_______________________ ___________

City of Harrisonburg__________ ____ ___________ | 52,401 2 26,200 3.62

Loudoun______________________ __________ 24,549 1 24,549 3.87

Bland_______________ _______ _______ __________

Giles_____________________ _____ ______ _____ _ J 23,201 1 23,201 4.09

Grayson__________ _______ ________ ____ _____

City of Galax.............................. .......... ................... | 22,844 1 22,644 4.19

Wythe.............................. .......................................... 21,975 1 21,975 4.32

Shenandoah................................................................. 21,825 1 21,825 4.35

State total................................................... . 3,966,949 100 39,669 2.40

9

Excluding Arlington, Norfolk, and several pertinent

overlapping districts (see note la, p. 7), every district

except six has more than twice the representation of the

people o f Fairfax. Twenty-seven districts have more

than three times the representation of the people of

Fairfax. The ratio between Fairfax and the four

most overrepresented districts is more than 4 to 1.

Twelve districts had twice the representation of

Arlington, and six, twice that of Norfolk.

The evidence also showed that measured simply by

the percentage of the population required to elect a

majority in each house of the legislature, Virginia

ranks well up on the list of well-apportioned States.

It requires just under 40 percent of the population to

elect majorities in both the Senate and House of

Delegates.

3. The Decision and Decree of the District Court.

On November 28, 1962, the district court, one judge

dissenting, sustained the plaintiffs’ claim and entered

an interlocutory order (R. 57-80). In an opinion by

Judge Bryan, concurred in by Judge Lewis, the court

held that the complaint alleged a claim upon which

relief could be granted; that the complaint pleaded a

class action and an actual controversy within the

Declaratory Judgment Act; and that the action was

not barred by the 11th Amendment as one by private

citizens against a State (R. 57-59).2 The court refused

to stay the case on the ground that the plaintiffs should

first procure the views of the State courts on the

validity of the apportionment, holding that since *

* The court sustained motions to dismiss the suit as to the

Governor and Attorney General, holding that those officials had

no “ special relation" to the elections in question (R. 59).

10

neither the 1962 legislation nor the State constitution

was ambiguous, no question of State law requiring

abstention was presented.

In applying the equal protection clause, the court

ruled, although population is the “predominant” con

sideration, other factors including “ [cjompactness and

contiguity of the territory, community of interests of

the people, observance of natural lines, and conformity

to historical division * * * are all to be noticed in

assaying the justness of the apportionment” (R. 65).

While exactitude in population is not constitutionally

required, the court said, “ there must be a fair ap

proach to equality unless it be shown that other ac

ceptable factors may make up for the differences in

the numbers of people” (R. 66). In view of the gross

inequalities in representation in Virginia (see pp. 6-9

above), the court put the burden of explanation upon

the defendants but found that they failed to meet i t ;

consequently, the court concluded that the discrimi

nation against Norfolk City and Arlington and Fair

fax Counties was invidious and violates the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (R. 67).

As for relief, the court said that, while it would

have preferred for the General Assembly to correct

the unconstitutionality of the 1962 legislation, it would

not defer the case until the next regular session of the

General Assembly in January 1964, because the dele

gates to be elected in 1963 would hold office until 1966

and the senators to be elected in 1963, until 1968 (R.

67-68), which would cause “unreasonable” delay in

correcting the injustices in the House and Senate

<R. 68).

11

The interlocutory order (1) declared that the 1962

apportionment violated the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment and accordingly was void

and of no effect; (2) restrained and enjoined the de

fendants from proceeding under the 1962 legislation,

but stayed the operation of the injunction until

January 31, 1963, so that either the General Assembly

could act or an appeal could be taken to this Court;

(3) provided that, if neither of these steps were taken,

the plaintiffs might apply to the court for further re

lief ; and (4) retained jurisdiction over the cause for

the entry of such orders as may be required (R. 80).

Judge Hoffman dissented both on the merits of

plaintiffs’ claim and on the question of relief and pro

cedure (R. 68-79). On the merits, he said that he

was not prepared to say that the discrimination under

the 1962 legislation violated the Fourteenth Amend

ment “ in the absence of further guidance” from this

Court or the Virginia Court of Appeals (R. 69). He

-said that the majority decision “place[d] too much

emphasis upon the weighted vote of one county, city,

or district as contrasted with the weighted vote in an

other county, city or district” (R. 69). On the ques

tion of relief and procedure, Judge Hoffman favored

application of the doctrine of abstention, at least until

the plaintiffs should have exhausted their remedies in

the State courts (R. 70, 7F-78).

The defendants noted an appeal on December 10,

1962, to this Court (R. 81-83). The Chief Justice

granted a stay of the injunction pending disposition

o f the case by this Court.

12

A R G U M E N T

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

The instant case raises a threshold question not

presented in the companion cases. The district court

refused defendants’ request that it abstain from de

ciding the basic issues under the federal Constitu

tion so that they could be litigated in the State courts,,

and that ruling is questioned on appeal.

We submit that ruling was correct. The federal

courts have power to determine suits challenging the

constitutionality of a State’s legislative apportion

ment. Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186. A federal action

over which the court has jurisdiction is not to be

dismissed merely because an alternative remedy may

be available under State law in the State courts.

E.g., Louisiana Power & Light Co. v. City of Thibo-

daux, 360 U.S. 25, 27. In this case there are no State

issues to be resolved before reaching the federal

question, nor is the constitutional right asserted by

the plaintiffs “ entangled in a skein of state law that

must be untangled before the federal case can pro

ceed.” McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U.S..

668, 674. The Virginia statute is precise on its face.

Plaintiffs’ claim is predicated upon the Fourteenth

Amendment. Therefore, the district court not only

had discretion but the duty to decide the ease.

Our basic analysis of the constitutional standards

to be applied in adjudicating challenges to the con

stitutionality under the Fourteenth Amendment of an

apportionment of seats in a State legislature is set

forth in the Brief for the United States in Maryland

Committee for Fair Representation v. Taives, jSTo..

13

29, this Term.8 Here, we predicate that the Four

teenth Amendment imposes substantive limitations

upon State legislative apportionment, as urged in

that brief (pp. 26-29).

We show below that the apportionment of the Vir

ginia legislature violates the second proposition ad

vanced in our Maryland brief (pp. 34-39)—that the

equal protection clause condemns gross inequalities in

per capita representation that have no rhyme or rea

son. We submit that, the people of Fairfax and

Arlington Counties and of the City of Norfolk have

been capriciously denied anything approaching equal

representation in either house of the Virginia legis

lature. Since these areas contain a substantial part

of the population, the discrimination cannot be brushed

aside as the kind of trifling inequality that sometimes

emerges in the operation of an essentially fair sys

tem. The only justifications suggested, in fact, fail

to explain the invidious discrimination. Even if

appellants’ figures concerning military personnel and

their dependents were acceptable, they would not

support the relatively inadequate representation ac

corded to Arlington and Fairfax Counties. Nor can

the discrimination be explained as an attempt to bal

ance urban and rural power. Other urban areas,

such as the City of Richmond, are given appropriate

representation. 3

3 The analysis, as stated in our Maryland brief, proceeds on

the assumption that the Fourteenth Amendment permits rea

sonable deviations from equal per capita representation in at

least one house of the legislature. The assumption is made

arguendo, reserving further judgment, because the’ issue does

not have to be decided in the present cases.

709- 361— 6:.!-----------2

14

I

THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY PROCEEDED TO AN ADJU

DICATION OF PLAINTIFFS’ CONSTITUTIONAL CLAIMS

The district court had jurisdiction of the subject

matter of the present action. The plaintiffs, who as

individual voters were the victims of the discrimina

tion against the people of Arlington and Fairfax

Counties and of the City of Norfolk, had standing

to bring the action. The federal question raised by

the complaint is justiciable. All three points were

settled beyond dispute in Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S.

186. Appellants’ argument is that the federal court

should have dismissed the complaint because the

issues had not first been litigated in the State courts,

and in this connection appellants point to the suit

entitled Tyler v. Davis in a State court (see Appel

lants’ Brief, pp. 26-27), which was instituted after

the decision below, raising the same questions. We

submit that there was no occasion for the district court

to postpone adjudication and that, in any event, it

would have been error to dismiss the complaint.

A . T H E DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY REFUSED TO POSTPONE A N A D JU D I

CATIO N P E N D IN G A STATE D E T E R M IN A T IO N OF T H E ISSUES

Where a federal court has jurisdiction of an action

arising under the Constitution of the United States,

it is the court’s duty to proceed promptly to a final

adjudication without deferring to State courts unless

some recognized ground of abstention appears. Only

two grounds have any possible relevance in the

present case.

15

1. Where the meaning of a State statute or other

State action is uncertain, and therefore its constitu

tionality cannot be determined until the State has

given its action definitive meaning, the federal pro

ceeding may be suspended for a reasonable period

pending clarification of the question of State law in

a State court. The reason for the rule is that the

federal courts will not anticipate a constitutional

controversy by adjudicating the validity of State

action upon a hypothetical interpretation. E.g.,

Government and Civic Employees Organizing Com

mittee v. Windsor, 353 U.S. 364, 366; Chicago v.

.Fielderest Dairies, Inc., 316 U.S. 168, 171-172; Spec-

tor Motor Service, Inc., v. McLaughlin, 323 U.S. 101,

104-105; American Federation of Laihor v. Watson,

327 U.S. 582, 596; Albertson v. Millard, 345 U.S. 242,

.244; Harrison v. National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored, People, 360 U.S. 167.

This ground of abstention is obviously inapplicable

to the present case, even if Harrison v. National As

sociation for the Advancement of Colored People,

supra, be thought to make the doctrine applicable to

cases under the Civil Rights Act involving an ante

cedent question of State law. Plaintiffs’ claims under

the Fourteenth Amendment require no preliminary

interpretation of the State legislation or of the sig

nificance of executive action. As both the majority

and dissenting judges in the court below agreed (R.

59, 76), the Virginia apportionment statute is clear on

its face. It defines exactly each legislative district.

It assigns specific numbers of representatives to each

16

district in the Senate and House of Delegates. There

is no room for interpretation. Consequently, there is

no justification for abstention. Toombs v. Fortson,

205 P. Supp. 248, 253 (N.D. Da.) ; Moss v. Burkhart,

U.S.D.C., W.D. Okla., decided July 17, 1963; Dyer v.

Kazuhisa Abe, 138 P. Supp. 220, 233 (I). Hawaii).4

2. The Court has also held that where the State-

action challenged in a federal court may be illegal

under the State’s own law, either statutory or consti

tutional, then the federal court should suspend action

until proceedings in the State courts reveal whether

there is need to decide the federal constitutional ques

tion. The rule is based partly upon the principle that

the federal courts should not adjudicate constitutional

questions unless their resolution is unavoidable, and

partly upon the desirability of avoiding unnecessary

conflict between the federal, courts and State govern

ments. Government and Civic Employees Organizing

Committee v. Windsor, 353 IT.S. 364, 366; Railroad

Commission v. Pullman Co., 312 TI.S. 496, 498, 500-

501; Chicago v. Fieldcrest Dairies, Inc., 316 IT.S. 168,

171-172; Spector Motor Service, Inc. v. McLaughlin,.

323 H.S. 101, 104-105. The doctrine is inapplicable

to the present case, however, first, because the action

is one under the Civil Rights Act and, second, because

4 Numerous other federal courts have considered the consti

tutionality of State apportionments without finding even the

necessity o f alluding to this question. See the federal cases

cited in the government’s brief in Maryland Committee for Fair

Representation v. Tawes, No. 29, this Term, pp. 26-27. Only

one court has held to the contrary. Lein v. Sathre, 201 F..

Supp. 535, 536 (D.N.D.).

17

there is no serious doubt about the validity of Vir-

'ginia’s apportionment under the Virginia Constitu

tion.

It would defeat the basic purpose of the Civil

Rights Act to hold that a federal court must tempo

rarily deny a plaintiff his civil rights under the fed

eral Constitution because he may also have a plausible

-claim that the defendant’s action is violating State

law. The very purpose of the legislation is to pro

tect the basic constitutional rights of American citi

zens against State infringement. Where the chal

lenged State action is ambiguous, it may be reasonable

to require the plaintiff initially to ascertain the pre

cise meaning of the State action so as to show that

his constitutional rights are actually being violated,

and to spare the court the danger of making an un

necessary ruling upon a false hypothesis. Cf. Harri

son v. National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, 360 U.S. 167. But where the nature

o f the alleged wrong is clearly established, it is no

answer to the plaintiff to say that perhaps he has a

different remedy in another forum. This Court

stated in Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167, 183, after a

lengthy analysis of the legislative history of the Civil

Rights Act—

It is no answer that the State has a law which

if enforced would give relief. The federal

remedy is supplementary to the state remedy,

and the latter need not be first sought and

refused before the federal one is invoked.

18

A requirement of abstention, whenever State action*

might violate State law would produce long delays 5'

and add greatly to the cost of vindicating federal con

stitutional rights. Litigants would be required to pro

ceed not only in the district courts and then to this

Court by direct appeal, but to the district court, to*

the State trial court and one or more State appeal;

courts, and then either to this Court directly6 or to*

the federal, district court and then to this Court. The

result is likely to be the defeat of important con

stitutional rights in voting, racial segregation, and

numerous other fields for a considerable period of"

time or, in practice, often forever.7 The only alterna

t o r example, this Court decided that the district court

should have abstained in Harrison v. National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People, swpra, in June 1959. A

suit was then brought in the State courts, which upheld the

constitutionality of the statutes. This Court ultimately re

versed and held that the statute violated the Fourteenth Amend

ment in National Association for the Advancement o f Colored

People v. Button, 37l TJ.S. 415, in January 1963, nearly four

years after the determination to abstain was first made.

6 This Court has reviewed cases on direct appeal from the

highest State court, after a federal district court has abstained

merely to allow the State courts to decide State issues while-

retaining jurisdiction. National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People v. Button, supra; Lassiter v. Northamp

ton County Board, of Elections, 360 U.S. 45. As a result, the

jurisdiction conferred by the Civil Rights Acts on the federal

district courts to decide federal constitutional questions in the

first instance may be entirely defeated.

7 “ The King of Brobdingnag gave it for his opinion that,

‘whoever could make two ears of corn, or two blades of grass

to grow upon a spot o f ground where only one grew before,

would deserve better of mankind, and do more essential service

to his country than the whole race of politicans put together.’

In matters of justice, however, the benefactor is he who makes

19

tive would be for voters to bring apportionment issues

in the State courts—a course which would defeat the

purpose of the Civil Bights Acts to provide a federal

forum for the assertion of constitutonal rights.

The recent decision in McNeese v. Board of Educa

tion, 373 U.S. 668, confirms the view that abstention

is not required in cases brought under the Civil

Rights Act where the sole State issue is the consti

tutionality of the State statute under State law. This

Court refused to order a federal district court to

abstain in a case brought under the Civil Rights Act

on the ground that segregation in an Illinois public

school might violate State law, saying that it would

defeat the purposes of the Act to hold that the

assertion of a federal claim in a federal court must

await an attempt to vindicate the same claim in a

State court. Id. at 672. Summarizing its view of

the applicable law, the Court stated (id. at 674) :

The right alleged is as plainly federal in

origin and nature as those vindicated in Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483. Nor is

the federal right in any way entangled in a

skein of state law that must be untangled

before the federal case can proceed. For peti

tioners assert that respondents have been and

are depriving them of rights protected by the

Fourteenth Amendment. It is immaterial

whether respondents’ conduct is legal or illegal

as a matter of state law. Monroe v. Pape

* * *. Such claims are entitled to be adjudi

cated in the federal courts.

one lawsuit grow where two grew before/' Chafee, Bills o f

Peace with Multiple Parties, 45 Harv. L. Rev. 1297.

20

Earlier, in Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S, 268, 274, the

Court likewise said in a case under the Civil Rights

Act that “ resort to a federal court may be had without

first exhausting the judicial remedies of state courts.”

Numerous lower federal courts have also held that

persons claiming rights under the Civil Rights Act

need not proceed first in the State courts to deter

mine whether the State conduct violates the State’s

own law. Browder v. Gale, 142 P. Supp. 707, 713

(M.D. Ala.), affirmed, 352 U.S. 903, involved statutes

and ordinances requiring segregation of buses in

Montgomery, Alabama. The district court refused to

abstain to allow a State court to determine either

the construction or validity of the statutes and ordi

nances involved because the doctrine of abstention

“ has no application where the plaintiffs complain that

they are being deprived of constitutional civil rights,

for the protection of which the Federal courts have

a responsibility as heavy as that which rests on the

State courts.” In Dyer v. KazuMsa Abe, 138 F. Supp.

220, 233 (D. Hawaii), the district court refused to

abstain in a case challenging the apportionment of

the Hawaii legislature even though it stated that the

apportionment plainly violated the Organic Act.

While the court believed that abstention was proper

where interpretation of local law could avoid a con

stitutional question, it said that otherwise a plaintiff

may litigate in. a federal court even though a local

court could grant effective relief. Ibid. In Romero

v. Weakley, 226 F. 2d 399, 400-402, the Ninth Circuit

noted that the California constitution had the same

21

provisions as the federal prohibiting racial segrega

tion of public schools. The court nonetheless said that

the plaintiffs were entitled to an adjudication under

the federal Constitution since the “ obvious purpose

of the civil rights legislation [was] to give the liti

gant his choice of a federal forum rather than of the

state.” Id. at 401. Accord, e.g., Westminster School

Dist. v. Mendez, 161 F. 2d 774, 781 (C.A. 9 ); Mitchell

v. Wright, 154 P. 2d 924, 926 (C.A. 5) ; Stapleton v.

Mitchell, 60 P. Supp. 51, 55 (D. Kansas), appeal

dismissed sub nom. McElroy v. Mitchell, 326 TT.S.

690; Wilson v. Beebe, 99 P. Supp. 418, 420-421 (D.

Del.).

The decision below would be correct even if the

abstention doctrine applied in an apportionment case

brought under the Civil Rights Act because, in the

present case, there is no substantial claim that the

Virginia apportionment deprives the plaintiffs of

rights secured by Virginia law. At one point the

complaint does allege that the apportionment violates

both the Fourteenth Amendment and the Virginia

Constitution (R. 7-8), but the reference follows two

allegations confined to violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment (R. 4, 6), and the complaint cites no pro

vision of the Virginia Constitution that is said to be

violated. The prayer for relief asks only that the

district court declare the apportionment invalid under

the Fourteenth Amendment (R. 8-9). The district

court construed the complaint not to assert rights

under the State constitution, for it described the issue

as one arising solely under the Fourteenth Amend

ment (R. 57-58).

22

There is no apparent ground on which the appor

tionment could be held invalid under the Virginia

Constitution. Virginia’s constitution establishes no

standards for apportionment of the legislature. The

only provision fixes the maximum and minimum num

ber of members in each house and states when they

should be elected. Article IV, Sec. 40-41, Appendix

A, p. 51. While appellants rely (Br. 24) on Article

IV, Sec. 43 (Appendix A, p. 51), it merely provides

for reapportioning every ten years. It is in marked

contrast to the analogue provision in the Constitution

of 1864 (Section 6) which required the legislature to

reapportion every ten years on the basis of an enum

eration of population. The Virginia Constitution

contains no provision guaranteeing equal protection

of the law. The two due process clauses are plainly

inapplicable.8

s One clause, under the heading o f “ criminal prosecutions

generally,” provides that no man shall “be deprived of life or

liberty, except by the law of the land * * Art. I, Sec. 8.

Apportionment of a legislature obviously has nothing to do

with a criminal prosecution. The other provision states that

“ no person shall be deprived o f his property without due process

of law * * Art. I, Sec. 11. Since the right to fair rep

resentation involves liberty not property, this provision is like

wise inapplicable.

Even if Virginia did have equal protection or a due process

clause applying to liberty, we still believe abstention would

not be proper. Many States have such provisions without ap

plying them to require fair apportionment. Indeed, we know

of no cases where they have been applied. Consequently, we

do not believe that even when such clauses exist, there is a sub

stantial enough likelihood that the State issue will be con

trolling for a federal court to stay its determination of the

federal constitutional issues (this is on the assumption, which

we reject above, pp. 16-18, that abstention is proper where there

is a real question as to the validity o f the State statutes under

the State constitution).

23

Brown v. Saunders, 159 Ya. 28, 166 S.E. 105, holds

nothing to the contrary. The Supreme Court of Vir

ginia held that the State’s congressional district

ing violated Art. IY, Sec. 55, of the Virginia Con

stitution, which requires congressional districts to

have “ as nearly as practicable, an equal number of in

habitants.” The specific requirement applicable to

-congressional districting obviously has no bearing on

apportionment of the legislature.

Contrary to appellants’ argument (Br. 26-28), the

pendency of litigation in the State courts challenging

the existing apportionment under both federal and

State constitutions is irrelevant. The present case was

brought on April 9, 1962 (R. 2), and decided by the

■district court on November 28, 1962 (R. 57, 79).

Tyler v. Davis was not instituted in the State court

until March 26, 1963, almost four months after the

district court had rendered its decision; in the trial

court the action was dismissed on the merits. Obvi

ously, the district court could not have taken into ac

count the State litigation even if it were relevant.

Nor should pendency of this action, which throws no

light upon the present issues, affect this Court’s con

sideration of the federal controversy.0 9

9 There is equally no basis for abstention in the other ap

portionment cases now being heard on the merits by this

Court—even if this issue had been raised in those cases.

Maryland Committee for Fair Representation v. Tawes, No. 29,

this Term, was decided by a State court and therefore cannot

possibly present the issue o f abstention. In WMCA, I no. v.

Simon, No. 20, this Term, the New York apportionment faith

fully follows the State constitution; indeed, it is the state con

stitutional provisions which are under attack. While the pre

'24

3. Although appellant does not raise the point, it

may be suggested that since a court-ordered reappor

tionment (if the legislature refused to act following

invalidation of the existing apportionment) would

penetrate deeply into the political processes of the

State and might require familiarity with State cus

toms as well as State law, a federal court should not

rule upon a challenge to an existing apportionment

under the Fourteenth Amendment if the question

could be litigated in a State court, which, presumably,

would be better equipped to formulate a judical rem

edy. In our view, abstention for this purpose would

not be appropriate for three reasons:

existing apportionment in Reynolds v. Sims, Xos. 23, 27, 41,

this Term, violated the Alabama Constitution, the highest State

court has refused to exercise jurisdiction in cases challenging

the apportionment o f the State legislature. Waid v. Pool,

255 Ala. 441, 442, 51 So. 2d 869; E x parte Rwe, 143 So. 2d

848 (Ala. Sup. C t.) ;

As to the congressional districting in Georgia involved in

Wesberry v. Sanders, Xo. 22, this Term, the Georgia Constitu

tion has no provisions giving standards for congressional dis

tricts. While it has equal protection and due process clauses

(Art. I, c. 2-1, Secs. 102, 103), there is no indication that these

general provisions would invalidate the present districts making

the decision of the federal constitutional issue unnecessary (see

p. 22, note above). In any event, as we emphasize in our brief

in that case (pp. 42-44), that case involves at the present time

only whether the complaint should be dismissed for want of

jurisdiction or o f equity. Since, as we have seen above (pp.

15-16), there is plainly no basis for dismissal in order to allow

the State courts to decide the State issues, the question of

abstention is not now at issue. On remand, the district

court may properly decide whether to stay proceedings for any

valid reason, such as to allow the State legislature to act. See

the cases cited in our brief in Wesberry v. Sanders, pp. 37-38.

25

First, the abstention doctrine lias never been ap

plied on the question of remedies. The doctrine is

derived from the precepts of constitutional law pre

venting unnecessary constitutional decisions and ad

visory opinions. Neither line of reasoning would

support abstention to allow a State court to frame a

remedy for violation of a federal, constitutional right.

Second, abstention prior to an adjudication of the

merits would be inappropriate even if it might be

within the court’s discretion once the task of formulat

ing a remedy was reached. The court below did not

undertake to reapportion the Virginia legislature. It

merely enjoined further action pursuant to the State

statute and provided ample opportunity for the State

legislature to adopt a new apportionment honoring

plaintiffs’ constitutional rights. In the event that the

legislature fails to act—an event there is no apparent

reason to anticipate—it will be time enough to con

sider what further relief should be awarded and

whether the plaintiffs should be required to ascertain

whether it can be obtained promptly in a State court.

Third, in the present case even a judicial reappor

tionment would not involve consideration of State law.

The Virginia Constitution contains no standards for

the apportionment of the legislature except to estab

lish the maximum and minimum size of each house.

There are no judicial decisions or statutes bearing

upon the question beyond those which the district

court found to be unconstitutional. Thus, in this case,

even the formulation of a judicial reapportionment

would not be entangled with questions of State law.

26

B. EVEN W H E N A B STE N TIO N IS APPRO PRIA TE , A DISTRICT COURT

SH OU LD R E T A IN JU R ISD IC TIO N TO A D JU D ICA TE T H E C L A IM S OF'

FEDERAL C O N STITU TIO N A L R IG H T

The doctrine of abstention, where applicable, pro

vides for the determination of State and federal

questions in orderly sequence. It is not a defense de

feating the plaintiff’s constitutional rights. Conse

quently, when a federal court stays its hand to await

a State determination, the proper course is to retain

jurisdiction pending the proceeding in the State

courts. Thus, in Louisiana Power & Light Co. v.

City of Thibodaux, 360 U.S. 25, 30-31, the Court,

while holding that State issues should be decided by

the State courts, ordered the federal district court

to retain jurisdiction. Accord, e.g., Harrison v.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, 360 U.S. 167, 179; Government and Civic

Employees Organizing Committee v. Windsor, 353

U.S. 364, 366-367; Railroad Commission v. Pullman

Co., 312 U.S. 496, 501-502; Chicago v. Fieldcrest

Dairies, Inc., 316 U.S. 168, 173; Spector Motor Serv

ice, Inc. v. McLaughlin, 323 U.S. 101, 106; American

Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327 U.S. 582, 599;

Albertson v. Millard, 345 U.S. 242, 245. The Court

in the Louisiana Power case specifically stated that

“ the mere difficulty of state law does not justify a

federal court’s relinquishment of jurisdiction in favor

of state court action” Id. at 27.

The occasional cases cited by appellants in which

the Court has ordered the dismissal of actions brought

in federal courts because of the existence of control

ling State issues are readily distinguishable. In

27

Pennsylvania v. Williams, 294 U.S. 176, 184, the

Court emphasized, in a case involving liquidation of

a building and loan association, that it was not a

State court but a State officer that was asserting

jurisdiction, and that this officer was charged by

State law with supervising and, in case of insolvents,

liquidating the State’s own associations. Further

more, the ease did not involve constitutional issues

and the Court emphasized that purely private rights

were involved. Id. at 185. Hawks v. Harnill, 288

U.S. 52, was a diversity case involving no claim of

federal right and which depended entirely on the

purely local question whether a State-granted fran

chise was valid under the State constitution. The

Court in Matthews v. Bodcjers, 284 U.S. 521, relied

on the well-established rule that the federal courts

will not enjoin State taxes where there is an adequate

State remedy by suing for return of taxes paid.

This is, as the Court emphasized (id. at 525), a par

ticular application of the general equitable principle

that suits in equity do not lie when there is an

adequate legal remedy. In Stainback v. Mo Hock Ke

Lok Po, 336 U.S. 368, 383, this Court made clear that

the Hawaii statute was susceptible to varying inter

pretations by the Hawaii courts. While the Court

ordered, without discussion, the complaint to be dis

missed rather than having the district court retain

jurisdiction until the scope of the statute was re

viewed, the result is inconsistent with the cases cited

in the text above (pp. 15-16) and numerous other deci

sions of this Court. The Court in Burford v. Sun Oil

Co., 319 U.S. 315, 331, 333-334, dismissed an action

28

challenging Texas’ regulation of oil wells within the

State since such regulation involves almost exclu

sively State issues which are of local and not general

concern, and review by the federal courts will pro

duce conflicting determinations where uniform regu

lation is necessary.

None of those cases is apposite here. There is no

substantial remedy at law for the malapportionment

of State legislatures. The State statutes here need

no interpretation. Legislative apportionment is not

of limited, local concern. Most important, the case

raises basic, constitutional rights under the Four

teenth Amendment concerning the right of American

citizens to equal participation in their own State gov

ernment. Thus, even if the federal courts should

sometimes stay proceedings in apportionment cases

for the determination of State issues, dismissal is

plainly improper. Once the State issues have been

determined, it is the duty of the federal courts to

protect constitutional rights and therefore to decide

the constitutional issues. The responsibility continues

whether or not State issues are also present.

The only case decided by this Court even suggesting

that controversies involving State legislative appor

tionment should be dismissed for want of equity is

Colegrove v. Green, 328 U.S. 549, which involved the

analogous issue of Congressional districting. There,

Mr. Justice Rutledge, who cast the deciding vote, said

that the cases should be dismissed for want of equity.

However, this view was not based on the need for

determining whether the statute was ambiguous or

might violate the State constitution. Rather, Mr.

29

Justice Rutledge concluded that the Court should

refuse to exercise its equitable discretion because “ [t]he

shortness of the time remaining [before the next

election] makes it doubtful whether action could, or

would, be taken in time to secure for petitioners

the effective relief they seek.” Id. at 565. In a

subsequent case involving the Georgia county unit

system, Mr. Justice Rutledge explained his position

in Golegrove as based on the “ particular circum

stances” of that case. Cook v. Fortson, 329 U.S.

675, 678.

In the present case, there was no difficulty arising

from the imminence of an election. Nor was there any

other special reason why the district court should not

have exercised its equitable discretion to prevent the

violation of federal constitutional rights.

II

Vir g in ia ’s l e g is l a t iv e a p p o r t io n m e n t v io l a t e s t h e

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT BY GROSSLY DISCRIMINATING

AGAINST THE PEOPLE OF ARLINGTON AND FAIRFAX COUN

TIES AND THE CITY OF NORFOLK WITHOUT RHYME OR

REASON

In our brief in the Maryland case (pp. 24-34), we

argued that population is the point of departure for

judging the constitutionality under the Fourteenth

Amendment of a State’s legislative apportionment.

Where serious inequalities are found in per capita repre

sentation, the apportionment violates the equal protec

tion clause unless some rational basis can be found for

the differentiation. When no justification is apparent

and the State offers none that is adequate, the differ

709- 361— 63------------- 3

30

ences in the representation of voters in the several

areas are arbitrary and capricious and therefore vio

late the Fourteenth Amendment.

These conclusions merely apply to apportionment

principles long settled under the Fourteenth Amend

ment. As the Court said in Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S.

186, 226, “ it has been open to the courts since the enact

ment of the Fourteenth Amendment to determine, if

on the particular facts they must, that a discrimina

tion reflects no policy, but simply arbitrary and capri

cious action. ” The lower courts have consistently ap

plied this principle in apportionment eases. See the

authorities cited in our Maryland brief, pp. 39 and

50-51.

The Virginia apportionment is invalid under the

foregoing rules.

A . T H E V IR G IN IA A P P O R T IO N M E N T SERIOU SLY D ISC R IM IN A T E S A G A IN ST

T H E VOTERS I N A R L IN G T O N A N D F A IR F A X 10 COU N TIES A N D I N T H E

C IT Y OF N O R FO LK

The discrimination against the voters in Arlington,

Fairfax and Norfolk is too plain for dispute.11 Ar

10 We use Fairfax County as a short-hand description for the

total area of the county including the cities of Fairfax and

Falls Church which are actually independent. The county and

the two cities constitute a single district in both the Senate and

the House of Delegates.

“ We do not mean to suggest that there is no discrimination

against other districts, or that such discrimination does not violate

the Fourteenth Amendment. Just as the district court did not

consider it necessary to decide whether such discrimination was

unconstitutional (see R. 67), we likewise do not discuss the issue.

I f the discrimination against Norfolk, Fairfax, and Arlington

violates the Fourteenth Amendment, the apportionment is uncon

stitutional and the district court’s injunction against further elec

tions under it was proper.

31

lington, Fairfax and the City of Norfolk are the three

most underrepresented districts in the State Senate..

The extent of the discrimination is demonstrated both

by the evidence that each has only about two-thirds

of its proper representation and also by comparison

of the per capita representation of their voters with

that of the three most over-represented districts:

Senatorial district Population

(1960)

Senators Population

per Senator

Percent of

ideal ratio *

163,401 1 163,401 61

305,872 2 152,936 65

285,194 2 142, 597 70

63, 703 1 63, 703 156

62,523 1 62,523 159

61, 730 1 61,730 161

i Since Virginia’s population is 3.966,949, the average or ideal population per Senator is 99,174.

Thus, the three most overrepresented districts have

2-1/2 times the per capita representation of Arlington

and Norfolk and over twice the representation of

Fairfax.

Arlington, Fairfax and Norfolk suffer in compari

son with almost all other senate districts. They have

the smallest percentages of the average ratio. Of

the 36 senate districts, twelve have over twice the per

capita representation of Arlington; ten have over

twice the per capita representation of Norfolk; and

six over twice that of Fairfax.

The situation in the House of Delegates is even

worse. The average population per delegate for the

State as a whole is 39,669. The population per dele

gate in Fairfax, Arlington, and the City of Norfolk,

which are the first, fifth, and sixth most underrepre

32

sented in the State,1- are 95,064, 54,467, and 50,978,

respectively. Contrast the three most overrepresented

districts:

House district

Population

(1960) Delegates

Population

per

delegate

Percent of

ideal ratio

285,194 3 95, 064 42

Arlington----------- -------- ----------------- ------------ ------- 163,401 3 54,467 73

City of Norfolk-------------------------------------------------- 305,872 6 50,978

Grayson, e ta l---------------------------- ----------------------- 22,644 1 22,644 175

Wythe_______________________ __________ ______ 21, 975 1 21,975

Shenandoah_________ —- --------------------------- ------- 21,825 1 21,825 182

Thus, the three most overrepresented districts have

over four times the representation of Fairfax and

about 2y2 times the representation of Arlington and

the City of Norfolk. Again, the discrimination is

not confined to a few favored districts but runs against

the counties in question in comparison with the rest

of the State. Twenty-seven districts of the seventy

have three times the representation of Fairfax; fifty-

five districts have over twice the representation of Fair

fax; twelve have twice the representation of Arling

ton; and six twice that of Norfolk City.12 13

Thus, the discrimination against Fairfax, Arling

ton, and Norfolk extends to both houses. Fairfax has

only 70 percent of its appropriate representation in

the Senate and only 42 percent in the House. Arling-

12 The second, third, and fourth most underrepresented dis

tricts are the City of Hampton, Chesterfield, et al., and the City

o f Portsmouth, which have populations of 89,258, 80,784 and

114,773 (57,386 per delegate), respectively.

13 The table also shows severe discrimination even among

Fairfax, Arlington, and Norfolk City. Fairfax has_ only

20,000 less people than Norfolk but Norfolk has twice as

many delegates. Arlington has slightly over half the popu

lation of Fairfax, yet has the same number of delegates.

33

ton has 61 percent of its appropriate representation

in the Senate and 73 percent in the House. Taking

the legislature as a whole they are, by a wide margin,

the three most underrepresented counties in the State.

Manifestly, the discrimination cannot be brushed

aside as sport in an essentially fair plan of representa

tion. The three districts in question contain almost

one-fifth of the population of the State.14

B . T H E GROSS D IS C R IM IN A T IO N IS BASED U P O N N O IN T E L L IG IB L E

PO LIC Y

The statutes of Virginia set forth no rational basis

for the foregoing inequalities in per capita repre

sentation. None is advanced in any of the documents

or other history underlying the statutory apportion

ment. Nor is any apparent from Virginia’s history

14 Appellants argue (Br. 46-50) that the discrepancies in

Virginia between districts are not as great as those in the

electoral college. However, as we showed in our brief in the

Maryland case (pp. 73-80), the federal government was a com

promise between a unified national government and a con

federation. Those who favored the former type of government

wanted representation based directly on population; supporters

of the confederation wanted representation based on the States.

Just as the Congress is a compromise of the two views as to

the basic nature o f the new government (and not as to what

kind of apportionment is permissible), so is the electoral

college. For a State has the same numbers of electoral votes

as it has representatives which are determined by population,

and senators, which are given equally to each State. The

States, on the other hand, are unitary governments operating

directly for the people and therefore only representation and

statewide elections based on population are permissible.

In Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368, 378, this Court held that

the electoral college was not analogous to the Georgia county

unit system for statewide election; certainly, that analogy is

far closer than the electoral college, which relates to nation

wide elections, is to state legislative apportionment.

34

generally, except that the same areas suffered similar

discrimination under the previous apportionment.

The justifications now put forward by appellants are

all afterthoughts that cannot be squared with the

facts.

1. Appellants’ principal contention (Br. 33-37)

is that the inequalities in per capita representation

are to be explained by a State policy of excluding

from persons entitled to representation all transient

military personnel and their families. The conten

tion fails for two reasons.

First, the policy of Virginia, so far as evidenced

by her election laws, actually favors military per

sonnel. They are not included in the categories of

persons disabled to vote. 24 Va. Code 18, Appendix A,

p. 57. Military personnel and members of their fam

ilies who have been residents of Virginia for a year,

residents o f a county, city or town for six months and

residents of a precinct for 30 days are entitled to vote.

24 Va. Code 17, Appendix A, pp. 56-57. Although the

mere stationing of military personnel in the State

does not give them residence (24 Va. Code 19, Appen

dix A, p. 58), Virginia election officials interpret the

provision to mean that residence for military person

nel is determined in the same manner as for all other

citizens. The Virginia election laws enable persons

in the armed forces to vote without registration or

payment of poll tax. 24 Va. Code (1962 Supp.) 23.1,

Appendix A, pp. 57-58. While the literal language of

the statute grants the privilege to those on “ active serv

ice * * * in time of war, ” the Virginia State Board of

Electors is applying it currently.

35

In no event could it be lightly assumed that in

apportioning representatives the Virginia legislature

would discriminate against men and women in their

country’s armed forces. Virginia’s policy, as evi

denced by its statutes, looks the other way. Since

other non-voters, such as felons and other temporary

residents, were not eliminated, it is unreasonable to

suppose that a State which favors military personnel

in voting, actually reversed itself to eliminate them

from consideration in apportioning representatives

in the legislature.

Appellants cite no evidence of any such legislative

intent. All the proposed apportionment plans which

preceded the 1962 apportionment, including the pro

gram of the Commission on Redistricting which re

ported to the governor (R. 159-188), invariably

used total population without reference to military

personnel or their families.

Second, the exclusion of military personnel from

the total population of the various districts will not

explain the discrimination against Fairfax, Arlington,

and Norfolk. Nor will the exclusion of 2y2 times the

number of military personnel, as appellants suggest

(Br. 37), in order to account for the entire families

of servicemen, explain the discrimination.

The following table will show that there is the same

gross discrimination in per capita representation in

the Senate even if military personnel and their

families are excluded from the population.15

15 The number o f military personnel in each county and inde

pendent city is given in Appendix B below, pp. 59-61. The

population o f each senatorial and house district after exclusion

o f military personnel and after exclusion o f 2y 2 times the

number o f military personnel is also given in Appendix B. pp.

62-67.

Senatorial district

Population

excluding

military

personnel

(1960)

Population

minus V/z

times

military

personnel

(1960)

Senators

Population,

excluding

m litary

personnel,

per Senator

Population,

minus 2 l/i

times

military

personnel,

per Senator

Percent of

ideal ratio

based on

exclusion of

military

personnel

Percent of

ideal ratio

based on

exclusion of

times

mi

personnel

152,025 134,961 1 152,925 134,961 63 67

261,491 194,919 2 130,745 97,460 73 i 93

268,227 242,777 2 134,113 121,388 71 75

63,143 62,303 1 63,143 62,303 152 146

62,325 62,028 1 62,325 62,028 154 146

61,730 61,730 1 61,730 61,730 155 147

3,833,867 3,634,244 40 95,847 90,856 100 100

i kppellmts state (Br 57) that Norfolk City is over-represented in the Senate if military personnel and their families are excluded. This is incorrect. Appellants’ view

is based on an average population per Senator throughout the State of 99,174. However, if military personnel are excluded, the average population per Senator is 9o,847 and

if 2H times the number of military is excluded the average population per Senator is 90,856.

CO

O

37

Using total civilian population, the three most over

represented counties have 2 ^ times the representa

tion of Arlington and over twice the representation

of the City of Norfolk and Fairfax. Of the 36 sen

ate districts, ten have over twice the representation

of Arlington, and three over twice the representation

of Norfolk and of Fairfax. Using total population,

minus 2 ^ times the number of military personnel,

the three most overrepresented counties still have

approximately twice the representation of Arlington

and Fairfax. Twenty-two districts have over 1%

times the representation of Arlington, thirteen have

over U/2 times the representation of Fairfax, and four