Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, Virginia Brief for the United States

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, Virginia Brief for the United States, 1970. 45c43357-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/efea3213-a56a-4dae-9a89-7b15b6e23a46/brewer-v-school-board-of-the-city-of-norfolk-virginia-brief-for-the-united-states. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

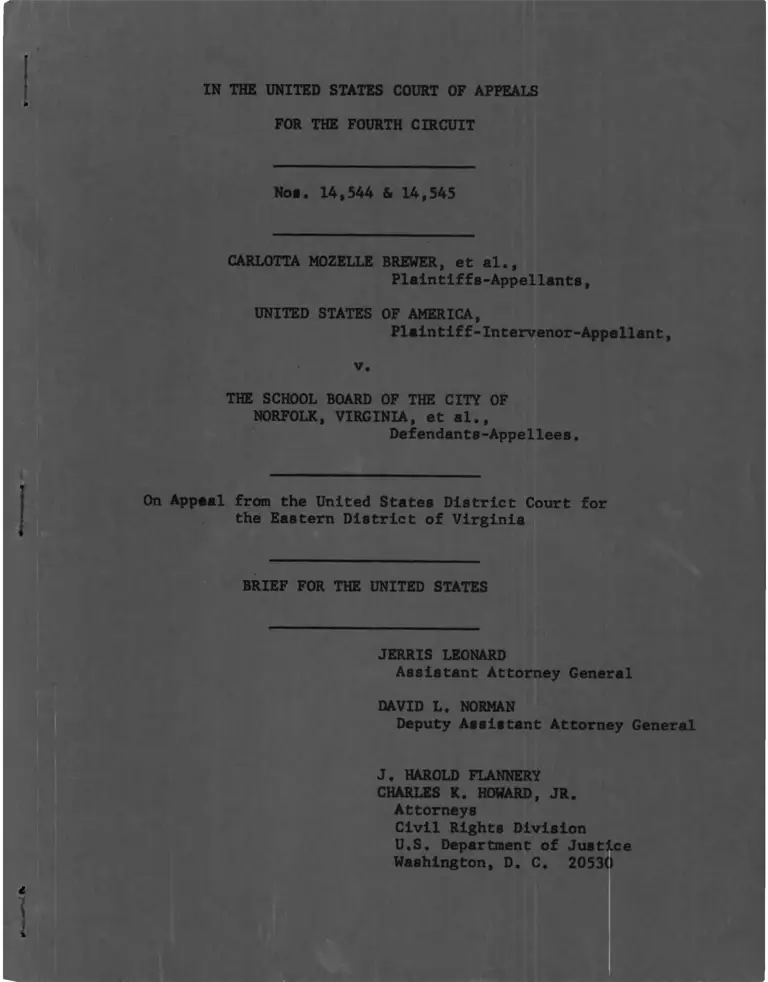

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 14,544 & 14,545

CARLOTTA MOZELLE BREWER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant,

v.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Virginia

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

JERRIS LEONARD

Assistant Attorney General

DAVID L. NORMAN

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

CHARLES K. HOWARD, JR.

Attorneys

Civil Rights Division

U.S. Department of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20530

8

10

13

17

21

29

31

34

37

40

49

52

53

59

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ------------------------- -

STATEMENT

A. Procedural History -----------------

B. Recent Proceedings----- -------------

C. Evidence

1. Student and Faculty Desegregation

in 1969-70 and 1970-71 ----------

2. Reenforcement of the Dual System

Since 1954 ----------- ----------

3. Residential Segregation --------

4. The Terminal Plan ---------------

5. Alternative Approaches ------ -

6. Pupil Transportation ------------

ARGUMENT

INTRODUCTION -------------------------------

A. De Jure Segregation--------- --------

B. The Terminal Plan -------------------

C. The Relief --------------------------

CONCLUSION -----------------------------------

APPENDICES

A. Chart - Faculty Desegregation -------

B. Chart - Student Desegregation System

W i d e --------- ----------------------

Page

C. Chart - Student Desegregation by School

with Projected Enrollments Under

Approved P lan------------------------- 60

D. Chart - A Sample of Contiguous Zoning -- 67

E. Chart - A Sample of Non-Contiguous

Zoning--------------------- 68

F. Chart - Projected Enrollments Under

Elementary Grouping Plan --------------- 69

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Andrews v. City of Monroe, ___ F. 2d ___ (No.

29,358, 5th Cir., April 23, 1970) ------------ 43

Anthony v . Marshall County Board of Education,

419 F. 2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969) --------------- 47

Beckett v. Norfolk School Board, 181 F. Supp. 87

(E.D. Va. 1959) ------------------ ------------ 5, 6

Brewer v. Norfolk School Board, 349 F. 2d 414

(4th Cir., 1965), 269 F. Supp. 118 (E.D. Va.,

1967), 397 F. 2d 37 (4th Cir., 1968), 302 F.

Supp. 18 (E.D. Va., 1969) -------------------- 7, 8

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) 43, 47

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board,

396 U.S." 290 (1970) --------------------------- 42

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange

County, ___ F. 2d ___ (No. 29,124, 5th Cir.,

February 17, 1970) ---------------------------- 43

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285

(1969) ------ --------------------------------- 47

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) 45

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ---- 44

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School

District, 409 F. 2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969) ------ 40, 45

Kemp v. Beasley, F. 2d ___ (No. 19,782, 8th

Cir., March 17, 1970) ---------- -------------- 43

Page

Keyes v. School District No. 1 of Denver, 303 F.

Supp. 279 (D. Colo. 1969); 303- F. Supp. 289

(D.Colo. 1969); ___ F. Supp. ___ (C.A. No. •

C-1499, D. Colo., March 21, 1970) ----------- 45

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450

(1968) ------------- -------------------------- 46

Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education,

418 F. 2d 1040 (4th Cir., 1969) ------------- 1, 9, 41

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, ___ F. 2d ___ (No. 29226, May 5,

1970) ---------------------------------------- 48

Spangler and United States v . Pasadena City

Board of Education, ___ F* Supp. ___ (No.

68-1433-R, C.D. Calif., March 12, 1970) ------ 45

Taylor v. Board of Education, 191 F. Stipp. 181

(S.D. N.Y., 1961), affirmed, 294 F. 2d 36 (2nd

Cir. 1961), cert, denied, 368 U.S. 940 (1961) 45

United States v. Greenwood Mimicipal Separate -

School District, 406 F. 2d 1086 (5th Cir.,

1969) -------- 40

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate

School District, 410 F. 2d 626 (5th Cir.

1969) ---------------------------------------- 45

United States v. School District 151, 286 F.

Supp. 786 (N.D. 111. 1968), 404 F. 2d 1125

(7th Cir. 1968), 301 F. Supp. 201 (N.D. 111.

1969) ---------- --------------------------- 39, 44, 51

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Following more than eleven years of litigation, including

eleven appeals here and two trials since this Court's last

remand for further proceedings, the court below (per Hon. Walter

E. Hoffman, J.), for reasons set forth in two Memorandum

J JOpinions, gave permanent approval to the school board s

terminal plan of desegregation. That plan provides for faculty

desegregation as required by this Court in Nesblt v. Statesville

City Board of Education, 418 F.2d 1040 (4th Cir. 1969), but

not until 1971-72; and for 1970-71, 69.5 percent of the Negro

children and 26.5 percent of the xdiite children will attend

2./segregated schools, approximately as follows:

1/ The opinion of May 19, 1969, is reported at 302 F. Supp.

L8 (E.D. Va. , 1969), the unreported opinion and order of

December 30, 1969, and January 9, 1970, have been furnished

to this Court under separate cover. The former opinion will

be referred to below by its Federal Supplement citation, the

latter by, 2 Mem. Op. ______.

2 / Defined here as any school attended ninety-eight percent

or more by children of one race. Some evidence in the record

suggests that any school attended ninety percent or more by

children of one race must be considered, for educational and

practical purposes, segregated (302 F. Supp. at 25). Using

that standard the number of white and Negro children in segre

gated schools would rise slightly. If one were to use the

defendants' criterion of a school providing inferior educational

opportunity, i.e., one attended by more than 30 to 40 percent

Negro children, the number of Negro elementary children in such

schools would exceed eighty percent.

Negro children in White children in

all-black schools all-white schools

Elementary 10,800 (76.47.) 6,945 (39.37o)

Junior High 3,055 (62.5%) 1,475 (21.37o)

3 /

Senior High 2,268 (53.7%) 0 (07)

Total 16,123 (69.57o) 8,420 (26.57c)

Viewed from the standpoint of schools, the results for 1970-71

are:

Total Schools White Negro Desegregated

Elementary 53 11 ‘ 19 23

Junior High 10 1 3 6

Senior High 5 0 1 4

The area-based terminal plan is derived from numerous

’’principles" which were approved and adopted by the court

below and which may fairly be reduced to two: first, desegre

gation is educationally self-defeating in any school attended

3 / The defendants have opted in their plan to balance racially

the senior high schools, but not until 1972-73 (at the earliest),

since implementation of this portion of the plan is contingent

upon construction of a new high school which will, in effect

but at a different site, replace the present Booker T. Wash

ington Senior High. Since 1970-71 enrollment will remain

substantially the same, the high school statistics shown

above are based on 1969-70 enrollment figures.

- 2 -

by more than 30 to 40 percent Negro children, i.e., beyond

that point the intended benefits to Negro children are not

realized and white children are harmed\ secondly, fulfillment

of the implications of the foregoing principle in a 60 percent

white school district, such as Norfolk, is not a realistic

alternative because Norfolk's extreme residential segregation

would necessitate a degree of pupil transportation that

would conflict with the neighborhood school concept and

would be administratively undesirable and economically

inadvisable.

Therefore, the questions on appeal are:

1. Whether the court below, by improper application of

racial and geographic criteria, erroneously limited Norfolk's

obligation to achieve racially unitary elementary and junior

high schools.

2. Whether that court abused its discretion in post

poning beyond the school year 1970-71 completion of faculty

desegregation and achievement of senior high school desegre

gation.

3. If the court below committed error and abused its

discretion, what further relief should be required.

- 3 -

A

STATEMENT

A. Procedural History

This case was filed by private plaintiffs on

4 /

May 10, 1956. The district court, by decree filed on

February 26, 1957, enjoined the school board "from refusing,

solely on account of race or color, to admit to, or enroll or

educate in any school under their operation, control, direction

or supervision, directly or indirectly, any child otherwise

qualified for admission to, and enrollment and education in,

such school." As a result of appellate proceedings the injunction

did not become effective until October 21, 1957.

The school board subsequently adopted and filed with the

district court on July 28, 1958, "Standards and Criteria" to

be applied to children desiring to transfer from an all-Negro

school for initial enrollment in a previously all-white school,

or from a white school to a Negro school. (Resolution, pp. 2

and 3, filed as Plaintiff's Exhibit 1, July 28, 1958). The

"Standards and Criteria" provided in substance that, the

assignment shall: not interfere with proper instruction of

pupils already enrolled in the school, be made only after

consideration of the applicant's academic achievement and the

~l£j The course of this litigation is recapitulated at 2 Mem. Op.

13-14, note 8.

- 4 -

academic achievement of students already in the school to

which he is applying, consider the physical and moral fitness

of the applicant, consider the mental ability of the applicant,

take into consideration the social adaptability of the applicant,

and shall take into consideration the cultural bacground of

the applicant and the pupils already enrolled in the schools.

The school board also established certain procedures to be

followed, which included testing and interviewing applicants

_5/

under the above standards and criteria.

For the 1958-59 school year 134 of 151 applications

for transfer by Negroes were denied on the basis of these

standards and procedures. This Court affirmed the district

court as to the 17 Negro children whose applications were

granted, and dismissed plaintiffs appeal with regard to the

134 denials as premature because the district court had

reserved for further consideration questions on the validity

of the standards and procedures contained in the July 17, 1958

resolution. School Board of the City of Norfolk v. Bee ke11,

5 / A study of Court Exhibits 1, 3, 4, 5, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14,

24”, 34, and 47, entered in evidence August 21-22, 1958, and the

Court Exhibits 1, 2, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13, entered in

evidence on August 27, 1959 discloses that the privilege of

transferring from the Negro system to the white system was

sparingly granted, e.g., the rejection rate in 1958-59 was

approximately 88 percent. The record does not disclose that

any white pupils availed themselves of the transfer appli

cation procedures to attend Negro schools.

- 5 -

r

260 F.2d 18 (4th Cir. 1958). By Memorandum and Order filed

on May 8, 1959, the district court held the standards and

procedures constitutional on their face and approved the

action of the school board in denying the 134 applications.

Beckett v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 181 F. Supp.

87 (E.D. Va. 1959). There was no appeal from this decision.

These standards and procedures remained in effect,

with minor modifications, until the 1963-64 school year. For

each of the school years 1959-60, 1960-61, and 1961-62 there

were district court proceedings involving denial of transfer

6 /

applications.

On July 11, 1963, Carlott.a Mozelle Brewer and others

moved to intervene and for further relief. In response to

this motion, the school board filed a plan for-desegregation

of the Norfolk schools based upon certain "Principles". This

plan involved some freedom of choice within certain geographic

zones, with each zone usually containing one white and one Negro

schools. Other students were assigned to schools on the basis

of zones, while at the senior high level all students had a

choice of Booker T. Washington, the at-large Negro school,

6 / The number of denials of request for transfer by Negro stu

dents can be determined to some extent by the number of children

involved in subsequent court actions. In addition to the 134

denials in 1958-59, there were 33 in 1959-60, 16 in 1960-61 and

63 in 1961-62. We can further determine from Answers to Inter

rogatories filed by defendants on November 1, 1963, (number 6)

that there were at least 28 in 1962-63 and 94 in 1963-64, a six

year total of 368.

6

as well as the school in their zones. (Defendants' Exhibit 1 and

Plaintiff's Exhibit 1-A-l through l-A-4, filed December 7, 1963).

7_/

This plan was first implemented for the 1963-64 school year.

This limited free choice plan was, in effect, ratified

by the district court in a Memorandum Opinion filed July 30, 1964.

(unreported). Plaintiff appealed and this Court remanded the

matter for further consideration in light of certain of its

supervening decisions. Brewer v. School Board of City of

Norfolk, 349 F.2d 414. (1965).

The United States was allowed to intervene under Title

IX of the 1964 Civil Rights Act (42 U.S.C. 2000h-2) on February

23, 1966. Shortly thereafter, on March 17, 1966, a consent

decree was entered approving a freedom of choice (within zones)

desegregation plan at the elementary and junior high school

levels which, with some modifications, is presently in effect.

(Plan, dated and filed March 17, 1966). The prior senior high

school procedures remained in effect, but were modified to a

system of assignment by zones at the behest of white intervenors

on June 2, 1967. Brewer v. School Board, 269 F. Supp. 118

(E.D. Va. 1967).

77 It appears from Plaintiff's Exhibits 2-B-2, 2-B-3 and 2-C,

"filed December 7, 1963, that many applications for transfer made by

Negro students were denied for the 1963-64 school year on the

grounds that such applications were made after May 31, 1963, which

was about two months before the new plan became public or operative

but which had been the transfer application cut-off date under the

prior plan.

7

Following plaintiffs' subsequent appeal, this order

was affirmed in part and vacated in part by this Court and

remanded for further proceedings, Brewer v. School Board

of City of Norfolk. 397 F. 2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968). The

instant appeal grows out of these further proceedings.

B. Recent Proceedings

The initial recent hearings below, in April and May

of 1969, followed several months of negotiations among

the parties which did not produce an agreed plan for 1969-70.

An early version of next year's area-based terminal

plan, as qualified by the percentage Negro doctrine, was

referred to by counsel for the school board and xvas the

subject of some testimony and pre-trial discovery by both

appellants here. (11 Tr. 11-31; 12 Tr. 84-85; deposition of

8/

Assistant Superintendent McLaulin, April 16, 1969, pp. 24-28).

Both parties appellant, while asserting the inadequacy of that

proposal with respect to both faculty and students, urged

that it be adopted with modifications as a minimum starting

8/ We are advised that the private appellants have arranged

with the Clerk of this Court to place on each volume of tran

script the arabic number corresponding to their identification

by roman numerals in the record on appeal transmitted by the

district court by letter dated April 10, 1970. Our transcript

citations will conform to that system, e.g., 1 Tr. 1, and wit

nesses will be identified by name. Exhibit references will be

to the offering party, the April or October, 1969, trial, and

where appropriate to transcript page.

8

point for 1969-70, instead of another year of the board's

freedom of choice/high school zones plan. However, the school

board contended and the court held (302 F. Supp. at p. 28)

that insufficient time remained to finalize the terminal

plan for implementation in 1969-70.

Unlike the procedure at the spring trial, the appellants

here were required at the October hearing to proceed first

with their proof, but the basic issue was the acceptability

of the school board's terminal plan in the light of more

promising alternatives assertedly available for 1970-71.

During final arguments on December 8, 1969, following

this Court’s decision in Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of

Education, 418 F.2d 1040 (4th Cir. 1969), plaintiffs and the

government renewed their arguments that certain relief,

particularly with respect to faculty and senior high school

desegregation, should become effective prior to the fall 1970

_9_/

school term. Except as noted below, such relief was denied.

In its Memorandum Opinion of December 30, 1969, followed

by its Order of January 9, 1970, the court below adopted the

defendants' terminal plan virtually in tact. On the basis of

9/ The arguments are presently being transcribed, but counsel's

notes reflect that the court's view was that the law of Nesbit

and its companion cases as to timing was not applicable to

Norfolk, that the court had proceeded expeditiously with the

Norfolk case and would continue to do so, and that further argu

ment with respect to time would not be heard.

9

evidence of space availability in certain white schools, and

representations by the defendants concerning feasibility, the

court directed the board, in its discretion, to fill such

vacancies with Negro pupils for the second semester of 1969-70.

(2 Mem. Op. 31, n. 24; Order of January 9, 1970, para. 2.)

According to a subsequent report by the school board, 213 Negro

pupils from 3 schools - accompanied by their teachers - were

transferred to 6 white schools. The Order also required court

approval of any use of Booker T. .Washington as a regular high

school after construction of the proposed new facility (Order

of January 9, 1970, para. 1).

C. Evidence

1. Student, and Faculty Desegregation in 1969-70

10./and 1970-71.

Government Exhibits 1, 2 and 3 (10/69), which appear

in the Appendix hereto, reflect current pupil and faculty

desegregation by school as well as pupil desegregation for

1970-71 under the terminal plan (Def. Ex. 1, 10/69). It was

not possible to project 1970-71 faculty desegregation by school

10/ The figures used in this section were as of the times

of trial and are not adjusted for the transfers of Negro pupils

effected in February of this year; nor do they project transfers

which may result from the qualified transfer provision in the

terminal plan (Def. Ex. 1, p. 7).

- 10 -

since the terminal plan provides only for complete desegre

gation by 1971-72 with half that goal to be reached for

1970-71.

The data disclose that the Norfolk system educates

approximately 56,628 students of whom 32,621 are white and

24,007 are black. There are 5 senior high schools (4 desegre

gated and one all-Negro); 11 junior high schools (of which

4 are all-Negro, and a fifth is 91 percent Negro, while 3

others are 3, 4, and 8 percent Negro, respectively); and of

56 elementary schools, 21 have 15 or fewer white pupils and

9 have fifteen or fewer Negro pupils. Thus, of 4220 Negro

senior high students, fewer than, half (46.3 percent) currently

attend formerly white schools; of 5903 Negro junior high students,

fewer than a quarter (24 percent) attend formerly white schools;

and of 13,884 Negro elementary children, fewer than a fifth

(19 percent) attend formerly white schools.

For 1969-70 the system employs 2475 regular classroom

teachers, of whom 840 (about 34 percent) are Negro and 1635

(about 66 percent) are white. Four hundred and seven (slightly

over 16 percent) of these teachers are presently assigned

across racial lines, and at only 2 of the districts' 73

schools do the faculties reflect approximately the racial

11

composition of the entire teacher corps. (Govt. Ex. 1, 10/69.)

The terminal plan of desegregation will result even

tually in 5 desegregated, racially balanced high schools

when a proposed new facility is completed(for 1972-73, at the

earliest), but the status quo of 4 desegregated high schools

JJ/

and one all-Negro high school will obtain until that time.

(21 Tr. 141, Thomas; 21 Tr. 150-151; 28 Tr. 14-16, McLaulin.)

Of ten junior high schools, which will be fed by

specified elementary schools, 3 will be ninety-eight percent

or more Negro, 1 will be all-white, and 6 will be desegregated.

(Def. Ex. 16, 10/69.)

At the elementary level more than half of the schools

will be all-white (11) or all-black (19) (Def. Ex. 15, 10/69).

Thus, more than three-quarters of the Negro elementary children

(approximately 10,800 of 14,130) and almost two-thirds of the

Negro junior high pupils (about 3055 of 4890) will go to

11 / As presented, the defendants' plan projected two possible

future uses of Booker T. Washington: (1) to accommodate any

excess of Negro students over their percentage quotas at

the other schools, and (2) to accommodate black separatist

students (27 Tr. 153-156, McLaulin). The court below explicitly

condemned the latter proposal in its second Memorandum Opinion

(p. 51) and conditioned the school's future use as a regular

facility upon prior judicial approval (Order of January 9, 1970,

para. 1); the Negro overflow option, however, apparently remains.

Other non-regular-school uses were also proposed.

12

schools that are 98 to 100 percent black. (Gov't Ex. 3, 10/69.)

Similarly, almost 40 percent of the white elementary children

(about 6945 of 17,655) and more than one-fifth of the white

junior high pupils will be assigned to schools that are 98

to 100 percent white.

In addition, the plan provides that Negro pupils may

transfer to any school which has space available and where

the 30 percent Negro quota has not been reached. (2 Mem. Op.

12/

23, n. 16.) The efficacy of this transfer provision is un

certain especially since the pupils will bear any transportation

expense involved (see undated school board report of

1JL/approximately February 10, 1970, pp. 2-3). (And see 12 Tr.

179, Lamberth; 28 Tr. 177-180, Bash.)

2. Reenforcement of the Dual System Since 1954

Although both trials below focused primarily upon

whether the school board's plan adequately disestablishes

12 / The transfer option does not refer to Negro pupils by race

but it does so by implication since 30 percent is the Negroes -

per school ceiling in other parts of the Board's plan. Pre

sumably, although it is not set forth,white children have an

analogus option to transfer to schools that are at least 70

percent white.

13 / Fuller consideration of the school board's plan and

the assertedly feasible alternative approaches suggested by

educational experts who testified for plaintiffs and the

government appears in part C, below.

13

the dual system in comparison with more promising alternatives

that were testified to be educationally sound and administratively

and economically feasible, some evidence was adduced tending

to show that, for years after this litigation began, a number

of school board policy decisions were based upon perpetuation

of the racially dual system.

For example, in 1957-58 Gatewood, Lee, and Madison

were schools in which all white teachers taught all white

pupils (Court Ex. 13-A, August 22, 1958). In 1963-64 Lee

and Madison were schools in which all black teachers taught

almost all black pupils (Pi. Ex. 1-A, December 7, 1963).

Superintendent Lamberth testified (Hearing of December 7,

1963, Tr. 26-27) about the change at Lee:

Q. I believe that prior to the close of the last

school session - that is during the 1962-63 school

session - and in prior years, the Lee school - the

Lee Elementary School was predominantly white as

far as student body was concerned?

A. Was prior to - it was predominantly white prior to

the present [1963-64 school session, yes.

Q. And the faculty and staff was all white?

A. Yes sir, that's right.

Q. And I believe that now the faculty is all Negro?

A. Yes

Q. Mien was the change made, sir?

A. July 1st, 1963.

14

(And see Govt. Ex. F-31, 4/69, Minutes of the Informal

School Board Meeting Held December 28, 1961.) The conversion

of Madison, among others, was projected at the school board

meeting of November 17, 1960 (Gov't Ex. F-29, 4/69):

Superintendent Lamberth stated that

Madison could be remodeled for use as

a junior high school v.7ith the help of

an architect and the application of

colored children to other schools in

the area would be greatly curtailed.

He complimented the Board on its willingness

to turn over schools to the colored students

(i. e. Ruffner, Brambleton, Berkley, Madison).

(And see Govt. Ex. F-27, item 11, 4/69.) Gatewood in 1966-67

was attended only by Negroes who were taught by an all-Negro

faculty (Govt. Exs. 1, 3, 10/69).

Similarly, faculty segregation practices were operative

as recently as this school year and last. The spring testimony

(12 Tr. 135-142, Brewster) of the system's personnel director,

considered together with his fall testimony (25 Tr. 13-18,

Brewster) and that of a research analyst witness for the

government (25 Tr. 39-57, Ross), disclose that the substitute

teacher roster was maintained by race, that assignments across

racial lines were "exceptions," and that during an eight-day

random period in the current school year white teachers on

the roster received 120 assignments to white schools (75 per-

15

cent or more white pupils) and 4 assignments to Negro

schools (75 percent or more Negro pupils). Simultane

ously, Negro teachers received 160.5 assignments to

Negro schools and 18 assignments to white schools.

Overall, substitute teachers were assigned to schools

where their race predominated more than ninety-three

percent of the time. (See Govt. Ex. 21, 10/69, tendered,

accepted, and rejected, 25 Tr. 55-56.)

The defendants’s position appeared to be that some

substitutes decline to teach across racial lines (25

Tr. 41-42).

16

3. Residential Segregation

In its most recent opinion (397 F. 2d at 41-42)

this Court directed that inquiry be made into the origins

of Norfolk's residential racial segregation; and the

court below inquired of counsel concerning that part of

this Court's opinion (12 Tr. 160-164, 4/69). Eighty

percent of Norfolk's Negro population resides in the

southwestern quadrant of the City with the balance in

smaller enclaves in the northwestern (TitustoWn) and

central (Oakwood, Coronado, Rosemont) portions (Govt. Exs.

B-l, B-2, 4/69)

The evidence, consisting of expert and lay testi

mony and documents, confirmed that the racial composition

of schools and neighborhoods are interdependent phenomena,

17

and that Norfolk's present residential segregation has

resulted substantially from public and private racial

discrimination.

First, the laws of Virginia from 1912 through 1947

explicitly authorized legally compelled residential

segregation (12 Tr. 165-167). Similarly, the ordinances

of Norfolk from 1920 until approximately May 1, 1951,

required residential segregation (12 Tr. 167-169). And

the testimony of an expert witness, that the effects of

such restrictions upon the racial composition of neigh

borhoods persist after the restrictions have been formal

ly/'

ly removed, was not challenged (16 Tr. 137-138, Jackson).

Second, expert testimony was adduced to the effect

that, at least prior to 1964, it was the practice of

public housing authorities to select sites for projects

and to assign tenants on a racially segregated basis

(16 Tr. 111-116, 120-121, Jackson), and that such prac

tices affect the racial composition of schools -

14/ As the witness's answer reflects, the second word in

line 10 at page 137-was "including" rather than "exclud-

mg' .

18

especially where the school is planned in conjunction

with the project (16 Tr. 118-119, Jackson). In that

connection, Govt. Exhibits F-l through F-31 and M,

M-l disclose a long history of close cooperation be

tween the school board and the Norfolk Housing and Re

development Authority (see esp. F-22, 28, 30, and 31,

15./4/69). Moreover, the G series of exhibits (G-l through

G-20, 4/69) confirms that degree of cooperation from

the Authority's standpoint and reveals that racial con

siderations, including the segregated racial composition

of present and future schools, were prominent factors in

the deliberations of the board and the Authority. Examples

1_5/ As expressed in a letter, dated February 15, 1950,

from School Superintendent Brewbaker to the Authority:

"Gentlemen: This confirms conversations concerning the

interlocking of our school program with your double program

of redevelopment of slum areas and construction of housing

on vacant land sites." (Govt. Ex. G-13, 4/69). And, at a

meeting with the Exectitive Director of the Authority on

January 2, 1958, "(9) The school Board raised the question

as to where he thought the families would relocate from the

Downtown Project. Mr. Cox stated that he did not think

that it would involve such encroachment on the existing

white areas." (Govt. Ex. G-18, 4/69)

19

of schools serving children of one race and that were

considered in conjunction with Housing Authority develop

ment plans are: Bowling Park (Project No. Va 6-7, Govt.

Ex. F-16 and G-6, 4/69); Diggs Park (Project No. Va 6-6,

Govt. Exs. F-16 and G-6, 4/69); and Roberts Park (Govt.

Ex. G-3, 4/69).

Third, it was undisputed that (presently unenforce

able) racially restrictive covenants appear frequently

in deeds to Norfolk residential property (Govt. Exs.

E-l through E-2-A, 4/69). In that regard, some evidence

adduced by defendants as well as the govenment. tended to

show that the restrictive effects of racial covenants

have persisted to the present and even now burden the

transfer of property. (16 Tr. 137-138, Jackson; 19 Tr.

278-282, Robertson.)

Fourth, testimonial and documentary evidence with

respect to private racial discrimination indicated that,

as recently as the spring of 1967, fewer than half of the

off-base rental housing facilities of five or more units

were available to Negro military personnel. (16 Tr. 149-

153, Pearce; Govt. Exs. L-l, L-2, 4/69).

20

Lastly, evidence from various other sources was

introduced that private discrimination presently af

fects housing opportunitites for Negroes in Norfolk.

(E.g., 16 Tr. 207, James; 19 Tr. 296-297, Ferebee; 16

Tr. 190, DeJournette; and 16 Tr. 230-231, Pearson.)

The defendants’ initial position at the spring

hearing appeared to be that evidence of residential

segregation was inadmissible as irrelevant to the in

terim plan (12 Tr. 180-181). It was also suggested

that, at least now, housing is available to Negroes

on a non-dlscriminatory basis (19 Tr. 289, Ferebee).

The school board’s position in the fall was that

its plan, while neighborhood-based, took residential

segregation into account to the extent feasible, but

not to the extent of coming into conflict with its

percentage Negro doctrine (see, e.g. 28 Tr. 155-158,

McLaulin).

4. The Terminal Plan (Def. Ex. 1, 10/69)

The defendants' terminal plan provides for pupil

desegregation within two limitations: first, Norfolk’s

21

residential racial segregation, combined with the board'

selection of a neighborhood plan and the° economic and

administrative inadvisability of more pupil transporta-

tion, limit desegregation a priori; secondly, and more

importantly, for reasons of school system stability and

educational quality, no desegregated school can accommo

date more than 30 percent (perhaps 40 percent in excep

tional cases) Negro children. The second limitation re

ceived extensive treatment below by all parties because

its implementation in Norfolk relegates so many Negro

children to schools denominated inferior, and because it

drastically limits in this district the use of such

traditional techniques of desegregation as zoning, con

tiguous pairing and grouping, and revised bus routes -

where a school less than 60 to 70 percent white would

result. (See, e,g., 29 Tr. 194-196, Lamberth; and 28

Tr. 155-158, McLaulin.)

The defendants' extensive testimonial and documen

tary evidence in support of the plan was offered to show

22

(a) that a school's social class composition is the

principal determinant of its quality; (b) that a mid

dle class school is educationally better for all

children; (c.) that in Norfolk white and Negro are sub

stantially synonomous with middle and lower class,

respectively; (d) that as the number of Negro children

in a school rises above 30 to 40 percent the intended

benefits to them disappear and the effects on the edu

cation of white children are increasingly adverse; (e)

that the educational unsoundness of the 30 percent-

plus Negro school induces white flight -- to the

16./eventual detriment of the entire system.

The appellants' challenges to this doctrine were

several. First, the doctrine and assertedly support

ing data were objected to as irrelevant if they were

-] / It was made clearer at the second trial that

the School Board seeks to avoid middle class flight

irrespective of race. (Compare 13 Tr. 234-235,

Thomas, and 18 Tr. 22-23, McLaulin; with 31 Tr. 45,

Pettigrew. But see 27 Tr. 129-130, McLaulin, and

21 Tr. 147, Thomas.) The operative effect of that

dictinction in a system which eauates class with

race, and which proposes to maintain 60 to 70 percent

white schools because they are the middle class,

remains less clear.

23

being offered as a limitation -- on account of race --

of the defendants' obligation to disestablish dual

schools. The objections were overruled. * (19 Tr.

188-190.)

Second, evidence introduced by plaintiffs and

the government focused upon the selected data being

relied upon by the defendants and tended to show:

(a) that the studies were inapposite to, and not

intended for, the use to which they were being put;

(b) that some of the data were mutually inconsistent

while others contradicted certain conclusions drawn

by the School Board; and (c) that certain crucial

inferences were in fact highly tentative, fragmentary,

or uncertain of uniform application.

For instance, certain studies are not studies

of the process of desegregation but, rather, are a

series of snapshots about particular children of

particular races at one point in time, i.e., the

studies are not longitudinal. (28 Tr. 146, McLaulin;

22 Tr. 119, Foster; 31 Tr. 109, Pettigrew; id., 111-112.)

24

Also, the principles are contradictory (22 Tr. 154-

155, Foster) and the data and studies upon which they

are based is inconclusive and subject to differing

interpretations (28 Tr. 150, McLaulin; 22 Tr. 131-

133, Foster; 24 Tr. 45 to 48, Stolee; 16 Tr. 64-65,

Stolee.) Social class becomes the one supreme factor

to the exclusion of many other proven factors which

have historically and universally been used in the

field of education in developing sound educational

policy, (22 Tr. 119-120, Foster; 26 Tr. 108-110,

Brazziel) and social science research is used without

regard to its limitations (22 Tr. 102-108, Foster).

Third, the defendants' witnesses testified to

their reliance upon certain findings cited, but they

also testified that no inrtuiry was made into whether

the findings in general applied to Norfolk in particular.

Nor was any effort made to compare specific data

assertedly relied upon with similar Norfolk data to

test the reliability, or at least the applicability,

of the former.

25

For example, studies introduced in support of

the percentage Negro doctrine were said to show that,

as the number of Negroes rises above 30 or so percent,

the performance of white children begins to decline

and the improvement in Negro performance slows and

then also declines. As noted above, problems in the

methodology of such studies undermine their validity

(28 Tr. 147-149, McLaulin) (Def. Ex. 24, 10/69,

p. 38 and 63); but the evidence also showed that

this system, which has a test5.ng program and schools

of varying Negro percentages, made no examinations of

its own data from this standpoint (28 Tr. 150, McLaulin).

And when the system’s pertinent test results were col

lected in a trial exhibit (Govt. Ex. 4-64a, 10/69), it

was apparent and agreed that no conclusions upon which

to base school policy could be drawn (31 Tr. 114, 116-

117, Pettigrew).

Finally, the evidence showed that the plan was

promulgated without systematic inquiry as to the cor

relation in Norfolk between race and social class

26

(28 Tr. 123-125, McLaulin), that different School

Board witnesses were determining social class by

different criteria (Dr. Pettigrew used parents edu

cation and Dr. McLaulin used income data. 31 Tr.

127-128, Pettigrew; 28 Tr. 66, McLaulin; Dr. Brazziel

disagreed with the criteria and their use, 26 Tr.

112-116, Brazziel), and that, while race and social

class were said to be independent variables in their

effects upon school performance (31 Tr. 125, Pettigrew;

and see Def. Ex. 1, 4/69), no one -- from all that

appears -- has sought to quantify eiJher in terms of

Norfolk or its plan.

The senior high school portion of the plan pro

vides for racially balanced high schools when a new

facility opens, at the earliest in 1972-73 (Def.

Ex. 7, 10/69; 21 Tr. 141, 10/69, Thomas). That will

entail significantly increased Negro pupil transporta

tion. (2 Mem. Op. 49, n. 34.) The School Board

declines to desegregate the high schools at once

because there are not enough white pupils who could

be zoned into Booker T. Washington consistent with

27

the percentage Negro doctrine, and desegregation by

transportation now is unacceptable. (21 iTr. 143-

150, Thomas.) The plan provides that Booker T.

Washington may be used as a regular facility for

blacks after the new school is in operation in order

to maintain the prescribed racial quotas elsewhere,

and there was testimony for the defendants that

black separatist students might go there. (Def.

Ex. 1, p. 7, 10/69; 27 Tr. 153-156, McLaulin.) The

trial court's order of January 9, 1970, requires

prior approval of any future use of Booker T. as a

regular facility.

28

Finally, desegregation of faculty and staff, by an

approximate racial balance formula, will be implemented

for 1971-72 (Def. Ex. 1, p. 9). It was suggested that

the accomplishment of this objective was being delayed

to permit additional in-service teacher training (2 Mem.

Op. 80). Other testimony indicated, however, that

teacher reassignments were made for 1969-70 independent

ly of such training (25 Tr. 11-13, Brewster), and that,

while such training is often helpful, it is most effec

tive when it accompanies, rather than precedes, teacher

desegregation {15 Tr. 514-517, Stolee).

5. Alternative Approaches

The government's view below was that the School

Board had a non-delegable duty to come forward with a

plan that promised realistically to work then. Conse

quently, the practice of presenting a comprehensive,

detailed plan for adoption by the district court in

tact, which has become current in the wake of recent

Supreme Court decisons, was not followed. At both

trials, however, the government presented a detailed,

- 29 -

illustrated series of approaches that expert witnesses

testified were options available to this district to

produce greater desegregation within the framework of

educational soundness and administrative feasibility.

And in the words of the School Board’s principal in-

house expert (27 Tr. 174-175, McLaulin):

...and I think I stated before that I don't

really thinlc I could do a much better job

than [the government -expert] did with even

considerable local knowledge. We might

change a boundary line here and there, but

the plan would look essentially as his plan

looks without any substantive modification

of the program,,

(Plaintiffs' expert witness agreed (26 Tr. 152-154)

Brazziel.)

The suggested approaches began with the use of con

ventional methods, such as zoning, contiguous pairing

and grouping, and revised minimally increased transpor

tation, which would have produced a modest but signifi

cant increase in desegregation. The other options,

each accompanied by maps, overlays, pupil assignment

computations and explanatory testimony as to educational

30

soundness and administrative feasibility, would increas

ingly employ related techniques, e.g., non-contiguous

pairing and more transportation, with a corresponding

increase in the desegregation achieved. Even educational

parks were touched upon. (14 Tr. 447-462, Stolee; 23 Tr.

87, et seq., Stolee; Govt. Exs. 18 through 18--B-2; 23 Tr.

179, Stolee; Govt. Ex. 18-D-l.)

In the last analysis, the suggested approaches could

not surmount the scissors effect of the School Board’s

"principles." The modest options which accommodated the

neighborhood concept were fouiid to conflict with the per

centage Negro doctrine; whereas approaches embodying the

Board's preference for preponderantly white schools would

sacrifice the neighborhood school concept.

6. Pupil Transportation

Approximately 8000 pupils are now transported to

schools in Norfolk (18 Tr. 74-75, McLaulin), and under

the School Board's plan that number will increase when

the new high school is in operation. Neither the School

Board nor the appellants presented to the court below an

31

analysis of the district's economic capability with

respect to increased transportation expenditures. To

be s\ire, evidence of grossly increased costs was pre

sented (and challenged); and the court below placed

great emphasis on the projected costs. The School

Board's position, however, during closing arguments on

December 9, 1969 (and see 29 Tr. 132-133, Lamberth),

seemed to be that, while mon.ey could be found for

transportation at its most expensive estimate, such ex

penditures should not be required at the sacrifice of

18/

other programs, and neighborhood schools.

Evidence was adduced by the plaintiffs to the ef

fect that the Board's cost estimates were unreal, that

the Board's projected bus routes did not-take into

account the suitability of presently available public

transportation and were inexpertly prepared without the

12/ The preponderance of the expert testimony was that

pupil transportation has no independent educational

significance. (23 Tr. 12.8-130, Stolee;. 28 Tr. 90,

McLaulin; 15 Tr. 500-503, Stolee.)

- 32 -

technical assistance available from the state, that

state funds to which the district would be entitled

for non-capital outlays had been omitted, and that

the actual costs of pupil transportation in nearby

Virginia cities were wholly inconsistent with the

Board's figures.

33

ARGUMENT

INTRODUCTION

Certain portions of the opinions below which

characterize the government’s view of the applicable

law suggest that the court misunderstood our position.

(See, e.g., 302 F. Supp. at 31.) It bears reiteration,

if only because it is also our position here.

The Constitution ordains no one method of

pupil desegregation, but it does require the con

version from duai to unitary systems. The district

courts, in their implementation of that mandate,

should require the adoption of that plan which

promises best, within the framework of educational

soundness, administrative feasibility and economic

resources, to end de jure segregated schools. Courts

often measure the adequacy of plans in terms of the

extent, to which white and Negro children go to school

together, and it is the school board's burden to

justify continued racial separation of children where

more promising alternatives are apparently at hand.

34

On the other hand, it is not our view that the

Constitution rectuires the racial balancing of pupils,

although the discretion vested in school boards would

permit that option. The circumstances of some dis

tricts may be such that some schools in a unitary

system will be attended disproportionately by children

of one race.

We find the legal applicability of these princi

ples to Norfolk not difficult. Many of the techniques

associated with de jure segregation have, at one time or

another, been employed by this district. That is

relevant here in two ways: first, it provides a

reliable measure of the extent to which the existing

racial dualism results from the policies of the Board;

and secondly, the Board's educationally ingenious,

but presumably not harmful (race aside), aevices

employed in furtherance of segregation,

35

illustrate how venturesome it can and must be in further-

y/

ance of desegregation.

We recognize, too, however, practically speaking,

that the Norfolk school system serves a racially segre

gated, sizable urban area. This Court is surely not un

mindful that children and buildings are where they are,

and that such factors cannot be disregarded. We would

emphasize, however, and the record is clear to this ef

fect, that people and facilities are in their present

places often as a result of racial discrimination; and

the Board may not rely upon the present effects of

policies to which it contributed as the bulwark of today’s

passive resistance to desegregation.

lfy Of course, we do not refer to methods such as the

attendance of 2400 Negro pupils at a school (L. I.

Washington, 1967-68, Govt. Ex. 3, 10/69) with a rated

capacity of 1800 (Govt. Ex. 15, 10/69), and an under

capacity white school (Lake Taylor) reasonably accessible

(That problem has been improved, 302 F. Supp. at 21.)

Rather, we refer to such techniques, familiar to this

system, as racially oriented zoning, pairing, and grade

restructuring.

36

A . De Jure Segregation

By a somewhat novel analysis, involving statutes of

other states dealing with miscegenation, Indian rights,

and Mongolians, the court below was led to the conclu

sion that " . . . the de facto-de .jure issue is not a

determinative factor in arriving at what is required

under Brown I and the subsequent cases." 2 Mem. Op. 75-79

and Appendix.

We reach the same conclusion, with respect to hoi.**

folk, by a different route. Even disregarding the effects

oh the composition of Norfolk’s schools of the longstand

ing ordinances requiring residential segregation, the

evidence shows that much of today’s dualism stems from

the interlocking segregationist policies'of the School

Board and the Housing Authority in the 1940's and 1950’s.

Of course, the issue is not the legality of such policies

when some of them were made. The point, rather, is that

even if Norfolk never had school segregation lavs, or if

after 1954 it had been racially neutral concerning schools,

its legal burden would be the same today because the

- 37 -

r

placement of schools by race (many in conjunction with

the Housing Authority's placement of people by race),

and related supplementary policies, were de jure acts

whose effects have yet to be undone.

In an article (citing, inter alia, a report of the

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights) written for a scholarly

publication, Dr. Thomas F. Pettigrew, one of the School

Board's principal witnesses, summed it. up as follows

(Govt. Ex. 22, p. 105, 10/S9):

Norfolk, Virginia is a good illustration

of *the extreme use of residential separation

to achieve racially-separate public education.

To strengthen the exploitation of existing

housing patterns, many of the city's new

schools are small, three-to-four room struc

tures for the first three to four grades.

These little boxes are carefully located to

maximize de facto school segregation (footnote

omitted).

We conclude, therefore, with the district court,

that today's racial separation of pupils in Norfolk is

entirely de 'jure, even irrespective of the Board's non

performance of its affirmative responsibilities since 19j>4.

A word as to faculty. Desegregation is lagging im

permissibly and that will be treated further, briefly,

38

below. In addition, however, the evidence showed -

with respect to the present school year as well as last

- that substitute teachers were designated on the roster

by race and, with rare exceptions, were being assigned

to schools attended predominantly by children of their

own race. Although we think the court below erred in

19/

its denial of relief and dismissal of that contention,

we acknowledge that it is less than the heart of this

matter. The significance of this evidence, however, is

that such flagrant de jure segregation, so directly with

in the control of the Board and so easily cured, is not

consistent with the "good faith" so often claimed by,

and attributed to, this Board. (See, e.g., 2 Mem. Op.

2-3). United States v. School District 151, 301 F. Supp.

iy Evidence with respect to this problem was presented

in the fall as well as the spring. In its second Memo

randum Opinion the court below held (p. 83); "There is

no merit to the contention that discrimination has been

shown in the assignment of substitute teachers. It does

not justify any discussion." The Board's position ap

pears to be that some substitutes decline to accept as

signments across racial lines (25 Tr. 41).

39

201, 229-230 (E.D. 111., 1969); Henry v. Claries dale

Municipal Separate School District, 409 F. 2d 682,

684 (5th Cir. 1969).

B. The Terminal Plan

We believe that the plan approved below is unaccept

able in its premises and, in light of the feasible alter

natives shown, it is equally unacceptable in its results.

Two issues, in our view., can be disposed of briefly

before turning to the Board's use of the neighborhood

school concept and its reliance on the percentage Negro

doctrineo The court below declined to require faculty

desegregation during 1969-70 or even for 1970-71 (2 Mem.

Op. 80-83)o Its reasons were the desirability of addi

tional in-service training and teacher reluctance in a

"seller's market". The latter reason is impermissible

(United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F. 2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969); and the former

reason is belied by the record in two respects. First,

there was expert testimony that such training, while de

sirable, is more effective as part of desegregation

- 40 -

r

rather than beforehand. Secondly, the Board's Director

of Personnel acknowledged that such training was not a

criterion in the transfer of teachers for 1969-70. We

urge this Court to require the acceleration of the Board's

faculty racial balance plan, including with respect to

summer programs and student teachers and substitute

teachers. Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education,

supra.

The defendants senior high school plan, which was ap

proved by the court, proposes to balance racially the

schools at that level by a combination of zoning and bus

ing. The problem, however, is that implementation of the

plan is contingent upon construction of a new high school

which cannot be ready before 1972-73. Meanwhile more than

half of the Negro high school pupils will continue to at

tend all-black Booker T. Washington. In addition, the

plan projects the possible future use of Washington as a

regular high school for Negroes should that become

necessary to keeping the other high schools 60 to 70

percent white.

- 41

There was testimony that the Board had considered

zoning in several hundred white students, but injected

that on account of the percentage Negro doctrine. The

option of busing whites in and blacks out was also con

sidered and rejected, although the school could be de

segregated in that way with less busing than is contem

plated for 1972-73. Lastly, the court rejected a plan,

offered by the government’s expert witness, that would

have paired Lake Taylor with Washington, resulting in

two 47 percent white schools. And from all that appears

that same result could be achieved by combining the Lake

Taylor and Washington zones.

Senior high school desegregation may not be

deferred pending construction of new facilities or the

fulfillment of any other contingency. Carter v. West

Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S. 290 (1970). We

agree with the district court (2 Mem. Op. 51) that

Booker T. Washington should not become a segregated

school for black separatists. But we cannot agree that

it may become a segregated school to accommodate the

- 42

percentage Negro doctrine elsewhere; and this Court

should explicitly disapprove such tise. Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

According to the defendants and the court below

(2 Memorandum Opinion, 58), the neighborhood school

concept is one of the plan's two key elements. (And

see 21 Tr. 166-168, Thomas.) In our view, this case

does not involve the validity of neighborhood schools.

(Cf. Kemp v. Beasley, ___ F. 2d ___, slip. op. p. 14

8th Cir., No. 19,782, March 17, 1970.)) First, rather

than assigning children on the basis of proximity and

school capacities, this plan involves zone lines, man

made and natural topographical factors, and the per

centage Negro doctrine. Compare Ellis v. Board of

Public Instruction of Orange County, Florida, ___ F.

2 d ___ (5th Cir., No. 29, 124, February 17, 1970),

with Andrews v. City of Monroe, ___ F. 2d ____ (5th. Cir.

No. 29,358, April 23, 1970, slip. op. pp. 4-6).

Second, the record here does not show that schools

have been located on the basis of pupil need independently

- 43

of the racial composition of neighborhoods. Indeed,

even putting aside the racial structuring of neigh

borhoods undertaken by Norfolk's authorities, this

record is conclusive to the effect that the School

Board located and built schools not for children in

the area, but for Negro children in the area contem

poraneously with other schools for white children in

the same or adjacent areas.

Of course, neighborhood schools is a familiar

principle of educational organization. But that

principle, like any other, may not be manipulated so

as to create and maintain racially dual schools.

United States v. School District 151, 404 F.2d 1125

(7th Cir. 1968) (affirmance of preliminary injunction);

same, 301 F. Supp. 201 (N.D. 111., 1969) (permanent

injunction); Taylor v. Board of Education, 191 F. Supp.

181 (S.D. N.Y., 1961), affirmed, 294 F.2d 36 (2nd Cir.

44

1961), cert, denied, 368 U.S. 940 (1961); Keyes v.

School District No. 1 of Denver, 303 F. Supp. 279

(D. Colo., 1969); same, 303 F. Supp. 289 (T). Colo.,

1969); same, ____F. Supp. ____ (C.A. No. C-1499,

D. Colo., March 21, 1970) (permanent injunction),

Spangler and United States v. Pasadena City Board_of

Education, ____ F. Supp. ____ (No. 68-1438-R, C.D.

Calif., March 12, 1970). See also Gomillion v.

Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1964).

Third, the Supreme Court has indicated that

" . . . a geographical formula is not universally appropri

ate. . . ." for the establishment of unitary schools.

Green v. P.rmntv School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 442, n. 6

(1968). And see United States v. Indianola Municipal

Separate School District, 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969)

and Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School

District, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969).

In the last analysis, however, we do not believe

that this case presents to this Court the nuestion or the

outer limits of the affirmative obligations of a neighbor,

hood schools-oriented board confronted by extreme

45

residential segregation not of its own making. This

Board's location of schools, manipulation of grade

structures, and drawing of zone lines to permit white

students to avoid nearer Negro schools make the ques

tion easier here.

20/

We come last to the Negro quota. To the extent

that it manifests the opposition of the white majority

to school desegregation it is impermissible. Monroe v.

Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450, 459 (1968).

We believe also that the educational hypotheses

involved are highly tentative and, concededly, there

has been no effort to measure them by the circumstances

of this district. (28 Tr. 138-139, 149-150, McLaulin.)

Moreover, some School Board witnesses agreed that the

20/ At one point (2 Mem. Op. p. 12), the court below

interpreted the doctrine as not reouiring white children

to go out of their "proper and legal zone" to attend a

majority Negro school. That is not the way it was

described by the Superintendent, however: ". . .but if

you draw the line and you see you get a 60 percent Negro

school and you say 'Principle Number So-and-so-that says

40 percent is the maximum,' than you change the line"

(29 Tr. 183, Lamberth).

- 46

correlation between race and the educational or socio

economic disabilities of some students, upon which the

hypotheses are based, is itself the product of prior

discrimination, including school segregation. (21 Tr.

126-128, Thomas; 28 Tr. 133-137, McLaulin.)

In a sense, therefore, this Court is being asked

to affirm not only the continuation of a slightly modified

dual system, but also to endorse the principle that prior

inequities may be the basis for present ones. Cf. Gaston

County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969). Whether or

not the schools that will be attended by a majority of

the Negro pupils in 1970-71 under the Board's plan may

fairly be characterized as the "academic scrap heap"

(22 Tr. 96-99, Foster), it seems irrefutable that the

Board candidly proposes to maintain one set of quality

schools for most whites and some blacks and another set

of lesser schools for most blacks and a few whites. And

to ascertain which are the inferior schools one need only

look at their racial composition. Cf. Brown v. Board of

Education, supra, at p. 494.

The United States urges, however, that this Court

need not sit as an educational tribunal. This case can

and should be decided upon the basis that the court below

- 47

erred when it permitted the Board to rely upon these

notions for a plan of segregation rather than desegre

gation. Anthony v. Marshall County Board of Education,

419 F.2d 1211, 1219 (5th Cir. 1969). For instance, by

the standards favored by the defendants’ principal

expert witness, Dr. Pettigrew, eight of fifty elementary

schools would be desegregated (31 Tr. 89-93, Pettigrew).

The School Board’s legal obligation is to estab

lish unitary schools by ". . . the best available

alternative.” Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, ____F. 2 d ____, slip op. p. 11 (5th

Cir., No. 29226, May 5, 1970). Educators may be skepti

cal of the theories employed, but so long as they meet

that requirement and do not otherwise entail racial dis

crimination, the racial desegregation retirements of

the Constitution are satisfied.

Presumably, this Board believes these theories.

And whatever their intrinsic merit, we find no constitu

tional impediment to their use as part of an otherwise

acceptable plan. As the expert Assistant Superintendent

testified, Norfolk’s racial percentages would permit the

almost unnualified implementation of these doctrines by

48

racially balancing the system. (28 Tr. 152, McLaulin.)

And among the options testified to by the government's

expert were several which illustrated how to do just

that--based on the Board's, not the government's,

asserted preference. (24 Tr. 81-82, Stolee.)

We conclude, therefore, that the defendants may

establish unitary schools by a formula uniformly

applied or several other methods. But on the facts

of this record neither this method nor any other, alone

or in combination, may be used to preserve unlawful

segregation.

C. The Relief

We believe that this case should be remanded to

the district court with the following specific instruc

tions .

(1) Faculty desegregation, including with

respect to student teaches and substitute

teachers, must be completed, by the formula

already adopted in the School Board's plan,

not later than the beginning of the 1970

summer session.

- 49

(2) That now and hereafter the Board must

operate desegregated senior high schools

not later than the beginning of the 1970-

71 school year, by the use of any proposal

now part of the record; or, should the

board opt for a different plan, such plan

shall be presented to the court below not

later than July 6, 1970, and plaintiffs and

the government shall be heard promptly with

respect to any objections they may make.

(3) With respect to the elementary and

junior high schools, we urge that the

defendants be required to adopt that edu

cationally sound plan or plans which

accomplish pupil desegregation, to the

maximum extent feasible, within the

resources of the district.

As described above in detail, this district

has long transported pupils and it may not now decline

to do so, in order to preserve segregation, to the

extent that it resources permit. We believe that

50

the record reflects that Norfolk can afford, by its

own funds and others apparently available, significantly

increased transportation expenditures. We recognize,

however, that no definitive analysis of the district's

financial capability has been done, and such may well

be appropriate upon remand. Compare United ..States v.

School District 151, 301 F. Supp. 201, 221-226 (N.D.

111. 1969). That analysis, in our view, need not be

made here.

We would recommend, in view of the extensive

studying and planning that has already been done,

and to enable the parties appellant to make objection

below, if appropriate, that the defendants be required

to file a new terminal elementary and junior high

school plan by July 6, 1970. Also, we respectfully

remind the Court and the parties that the United

States Office of Education stands ready to assist

in the finalizing of the plan.

We are hopeful, despite prior disappointments,

that a general direction by this Court requiring the

Board, with or without extra-system technical assistance

51

illustrated below orand by means of the options

otherwise, to accomplish elementary and junior

high school desegregation, as defined above, will

be fulfilled.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, we urge that the

Judgment and Order of the district court should be

reversed and remanded with directions.

Respectfully submitted,

JERRIS LEONARD

Assistant Attorney General

DAVID L. NORMAN

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

CHARLES K. HOWARD, JR.

Attorneys

Department of Justice

i

FACULTY ASSIGNMENTS IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

FALL, 1966 - FALL, 1969

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA

1966-67 1967-63 1968-69 1969-70

LnLO

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS W N T %N W N T 7oN W N T 7oN W N T 7oN

Ballentine -- 0 -- 0 9 1 10 10

•

10 1 11 9 9 2 11 18

Bay View 33 2 35 6 28 2 30 7 30 2 32 6 28 2 30 7

Bowling Park 0 - - -- 100 1 30 31 97 3 39 42 93 6 31 37 84

Calcott -- 0 _ _ 0 27 2 29 7 31 2 33 6 28 2 30 7

Campostella 6 2 8 25 5 3 8 38 4 3 7 43

Carey 0 -- -- 100 2 13 15 87 3 16 19 84 3 13 16 81

Chesterfield 25 2 27 7 22 4 26 15 26 6 32 19 16 10 26 38

Coleman Place -- 0 -- 0 28 3 31 10 33 3 36 8 26 5 31 16

Coronado

(Norview Annex) •' 0 -- -- 100 2, 4 6 67 2 3 5 60 6 2 8 25

Crossroads -- 0 -- 0 37 2 39 5 41 2 43 5 36 3 39 8

Diggs Park 2 18 20 90 2 19 21 90 4 23 27 85 6 17 23 74

16 1 17 15 3 18 17 15 3 18 17 14 3 17Easton 18

1966-67

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS W N T %N

East Ocean View _ _ 0 -- 0

Fairlawn -- 0 -- 0

Gatewood 0 -- -- 100

Goode 0 -- -- 100

Granby Eleru. -- 0 _ _ 0

Ingleside 14 2 16 13

Lafayette -- 0 _ _ 0

( Lakewood 27 2 29 7

On■p' Lansdale -- 0 -- 0

Larchmont -- 0 -- 0

Larrymore 27 2 29 7

Lee 5 19 24 79

Liberty Park 0 _ _ -- 100

Lincoln 0 -- -- 100

Lindenwood 3 22 25 88

Little Creek Elem. 23 2 25 8

Little Creek Prim. 20 2 22 9

1967-68 1968-69 1969-70

W N T %N W N T %N W N T %N 1

5 1 6 17 5 1 6 17 (See Pretty Lake)

16 1 17 6 17 2 19 11 16 2 18 11

AZ 18 20 90 3 19 22 86 5 16 21 76

0 -- -- 100 1 16 17 94 3 14 17 82

21 1 22 5 29 2 31 6 23 2 25 8

16 2 18

•

11 16 2 18 11 16 2 18 11

9 1 10 10 11 1 12 8 7 2 9 22

21 3 24 13 23 2 25 8 21 3 24 13

22 2 24 8 • 24 2 26 8 23 4 27 15

23 2 25. 8 24 2 26 8 23 2 25 8

34 2 36 6 36 3 39 8 33 3 36 8

5- 15 20 75 6 18 24 75 11 14 25 56

0 -- -- 100 1 21 22 95 3 18 21 86

4 15 19 79 4 17 21 81 7 16 23 70

4 21 25 84 4 24 28 86 7 23 30 77

22 3 25 12 25 3 28 11 21 4 25 16

20 2 22 9 24 1 25 4 21 3 24 13

1966-67

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS W N T 7oN

Madison 1 5 6 83

Marshall 17 4 21 19

Meadowbrook 22 2 24 8

Monroe 31 6 37 16

Norview 22 2 26 8

Oakwood 5 18 23 78

Oceanair -- 0 -- 0

Ocean View -- 0 -- 0

Pineridge -- 0 -- 0

Poplar Halls 18 2 20 10

Pretty Lake -- 0 -- 0

Roberts Park 0 -- -- 100

Rosemont 2 5 7 71

St. Helena 4 11 15 73

Sewells Pt.

(Annex & Elem.) 17 5 22 23

Sherwood Forest 23 2 25 8

1967-68

W__N_T__

3 8 11

15 7 22

20 2 20

32 7 39

16 2 18

3 14 17

-- 0 --

30 3 33

11 1 12

19 2 21

-- 0

4 16 20

1 2 3

3 12 15

19 6 25

2 26

1968-69 1969-70

%N W N T 7oN W N T %N

73 3 9 12 75 See Jr■. High

32 18 11 29 38 10 18 28 64

9 21 3 24 13 20 3 23 13

18 29 16 35 46 19 24 43 56

11 13 5 18 28 14 3 17 18

82 3 16 19 84 4 14 18 78

0 24 5 29 17 20 2 22 9

9 31 3 34 9 29 8 34 15

8- 9 2 11 18 8 2 10 80

10 20 2 22 9 19 2 21 10

0 . 4 1 5 20 3 2 5 40

80 4 16 20 80 5 15 20 75

67 4 3 7 43 See Jr. ]high

80 4 12 16 75 4 11 15 73

24 27 4 31 13 27 7 34 21

8 24 1 25 4 21 3 24 1324

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

Smallwood

Stuart

Suburban Park

Tarrailton

Taylor

Tidewater Park

Titus

Titustown

Tucker

West

Willoughby

Young Park

w 1966N -67T YoN

0 -- _ _ 100

28 2 30 7

21 2 23 9

22 2 24 8

-- 0 -- 0

4 18 22 82

0 -- -- 100

3 11 14 79

0 -- -- 100

0 -- -- 100

-- 0 -- 0

3 19 22 86

1967-68W N T %N

2 17 19 89

29 3 32 10

17 2 19 11

20 3 23 13

14 2 16 13-

3 18 21 86

0 - - - - 100

0 - - - - 100

0 - - - - 100

0 - - 100

20 3 23 13

4 16 20 80

1968-69W N T %N

4 16 20 80

28 6 34 18

21 1 22 5

22 3 25 12

16 2 18 11

4 18 22 82

3 20 23 87

1 11 12 92

0 -- -- 100

2 19 21 90

21 4 25 16

3 21 24 88

1969-70W N T %N

7 12 19 63

24 10 34 29

19 2 21 10

19 4 23 . 17

14 2 16 13

8 15 23 65

6 17 23 74

3 8 11 73

3 16 19 84

3 18 21 86

20 4 24 17

5 18 23 78

Faculty represents full-time classroom teachers.

Sources: School Board Reports to the Court, 1966-1968. 1969 Statistics^as provided by

Dr. McLaughlin in Sept. 1969. (Schools with uniracial faculties were omitted from the

the reports. In those instances, the % Negro is based on the traditional racial composition

of the school.)

FACULTY ASSIGNMENTS IN THE JR. HIGH SCHOOLS

FALL, 1966 - FALL, 1969

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA

JR. HIGH SCHOOLS W

1966

N

-67

T 7oN W

1967

N

-68

T %N W

1968-69

N T 7oN W

1969-70

N T %N

Azalea Gardens 63 3 66 5 67 3 70 4 68 3 71 4 67 6 73 8

Blair 68 5 73 7 67 8 75 11 67 9 76 12 64 12 76 16

Campostella 8 46 54 85 7 45 52 87 8 50 58 86 13 44 57 77

Jacox 6 60 66 91 8 57 65 88 9 61 70 87 13 61 74 82

Lake Taylor 61 3 64 5 65 2 67 3 67 2 69 3 69 4 73 5

Madison 2 15 17 89 4 21 25 84 5 2 27 81 13 32 45 71

Northside 71 3 74 4 71 4 75 5 70 5 75 7 65 9 74 12

Norview 53 2 55 4 48 6 54 11 50 6 56 11 50 7 57 12

Rosemont 5 8 13 61 7 15 22 68 9 13 22 59 10 14 24 58

Ruffner 3 60 63 95 5 58 63 92 8 57 65 88 15 48 63 76

Willard 32 2 34 6 32 ' 3 35 9 32 4 36 11 33 4 37 11

TOTALS 372 207 579 36 381 222 603 37 393 232 625 37 412 241 653 37

Faculty represents full-time classroom teachers.

Sources: School Board Reports to the Court, 1966-68. 1969 Statistics as provided by Dr.

McLaughlin in September, 1969.

FACULTY ASSIGNMENTS IN THE SR. HIGH SCHOOLS

FALL, 1966 - FALL, 1969

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA

1966-67 1967-68 1968-69 1969-70SR. HIGH SCHOOLS W N T %N ' W N T %N W N T %N W N T YoN

Granby • 105 2 107 2 103 5 108 5 103 5 108 5 99 9 108 8

Lake Taylor 76 8 84 10 102 9 111 8 101 8 109 - 7

Maury 104 3 107 3 94 5 99 5 102 8 110 7 9712 13 11012 12

i

NorviewCO 114 3 117 3 105 6 111 5 105 7 112 6 103 8 111 7

1 Washington 7 101 108 94 17 95 112 85 17 99 116 85 27 90 117 77

TOTALS 330 109 439 25 395 119 514 23 429 128 557 23 42712 128

1

555 2 23

Faculty represents full-time classroom teachers.

Sources: School Board ReDorts to the Court, 1966-68. 1969 Statistics as provided by Dr.

McLaughlin in September, 1969.

TOTAL .PUPIL ENROLLMENT BY RACE AND LEVEL

FALL, 1966 - FALL, 1969

NORFOLK PUBLIC SCHOOLS

RACE ELEM. JR. HIGH SR. HIGH ALL LEVELS

1966-67 W 19,923 6,907 6,486 33,316

N 14,443 4,092 3,190 22,535

T 34,366 11,809 9,676 55,851

7oN (42) (42) (33) (40)

1967-68 W 19,164 6,904 7,235 33,303

N 14,173 5,258 3,632 23,063

T 33,337 12,162 10,867 56,366

%N (43) (43) (33) (41)

1968-69 W 18,563 6,853 7,086 32,502

N 14,188 5,533 3,793 23,514

T 32,751 12,386 10,879 56,016

7oN (43) (45) (35) (42)

1969-70 W 18,302 7,082 7,237 32,621

N 13,884 5,903 4,220 24,007

T 32,186 12,985 11,457 56,628

7oN (43) (45) (37) (42)

Sources: School Board's Annual Reports to the Court, 1966-1968.

1969-70 Enrollment figures as provided by School Board

in September, 1969.

59

PUPIL ENROLLMENTS IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

FALL, 1966 - FALL, 1969

AND

PROJECTED ENROLLMENTS

UNDER SCHOOL BOARD’S LONG RANGE PLAN

1969 1969 1966-67 1967-

School Grades Capacity W N T %N W N.

Ballentine 1-6 270 302 0 302 0 253 1

Bay View 1-6 795 1066 0 1066 0 856 0

Bowling Park 1-6 925 0 931 931 100 0 962

Calcott 1-7 795 842 0 842 0 846 0

Camp Allen 1-6 735 — -~ --

CampoStella 1-6 245 47 155 202 77 50 155

Carey 1-6 545 0 519 519 100 0 418

Chesterfield 1-7 735 285 481 766 63 193 547

Coleman Place 1-6 925 910 0 910 0 925 0

Coronado 1-3, 215 0 176 176 100 0 158

5-6

- 60 -

Projected

68

T %N

1968-69

W N T 7oN

1969-70

W N T

1

7oN

Long Range

Plan

W N T

254 0 247 0 247 0 252 TJL

1

253 0 505 170 675

(Combined

with

Lafayette)

856 0 814 19 833 2 874 0 874 0 850 0 850

962 100 0 963 963 10C 0 934 934 100 0 850 850

846 0 825 3 828 0 841 0 841 100 850 0 850

205 76 48 145 193 75

(To be con

structed)

45 136 181 75

550 185 735

55 170 225

418 100 0 393 393 100 0 366 366 100 0 500 500

740 74 90 635 725 88 15 671 722 93 110 615 725

925 0 893 0 893 0 865 0 865 0 875 0 875

100 0 118 118 100 107 103 210

("Norview

Annex")

49 (Combined

with

Norview)

Proj ected

Long Range

School

1969

Grades

1969

Capacity

1966-67

W N T

Lincoln

Lindenwood

Little Creek

Elera.