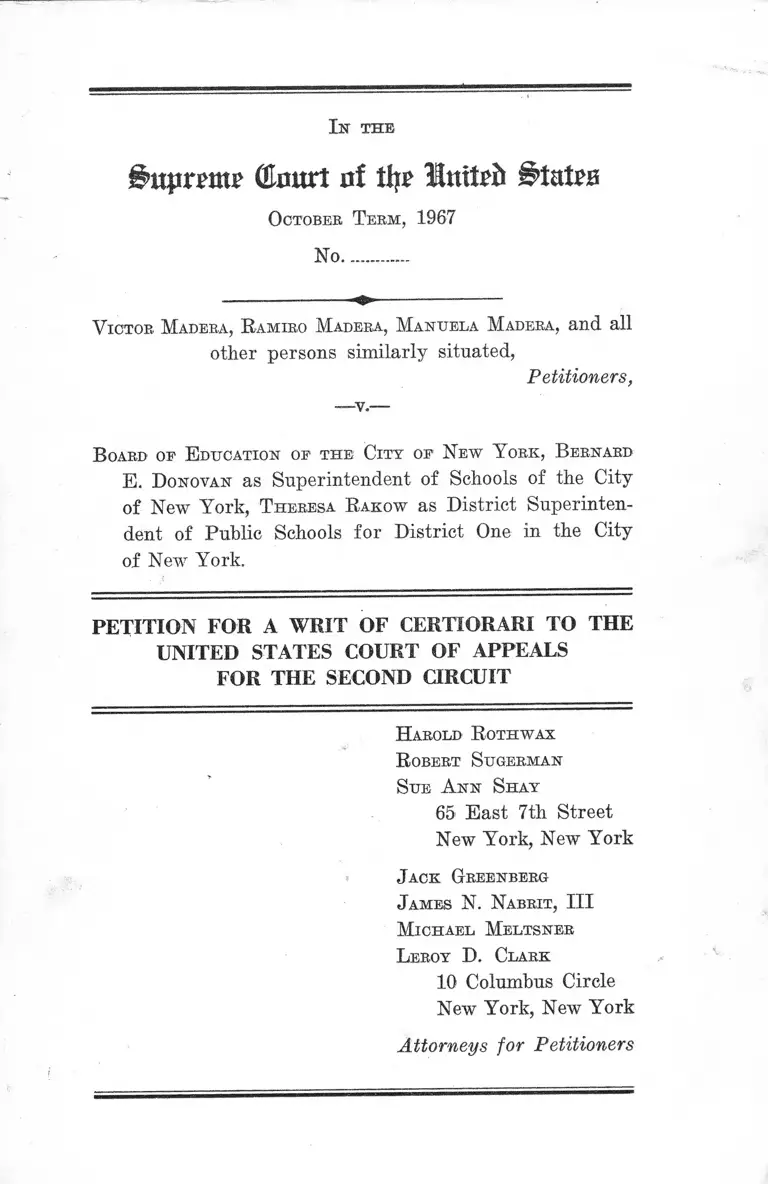

Madera v. Board of Education of the City of New York Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Madera v. Board of Education of the City of New York Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1967. 079283d2-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f01f37e0-98e9-4ee4-b02d-7e3530493a2a/madera-v-board-of-education-of-the-city-of-new-york-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

(Emtrt ni tfyp States

October Term, 1967

No.............

V ictor Madera, R amiro Madera, Manuela Madera, and all

other persons similarly situated,

Petitioners,

—v.—

B oard op E ducation op the City op New Y ork, B ernard

E. D onovan as Superintendent of Schools of the City

o f New York, T heresa R akow as District Superinten

dent of Public Schools for District One in the City

of New York.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

H arold R othwax

R obert Sugerman

Sue A nn Shay

65 East 7th Street

New York, New York

J ack Greenberg

James N. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Opinions Below ....................... 2

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 2

Question Presented ............................................................ 2

Constitutional Provisions, Statutory Provisions, and

Regulations Involved .................................................... 3

Statement ....................................................................... 3

How the Federal Question Was Raised and Decided

Below ................................................................................ 9

PAGE

R easons for Granting the W rit

The restriction on the role of the lawyer in this

case raises an issue of national importance in that

it severely impairs effective protection of the legal

rights of the poor ...... _............................................... 10

Certiorari should be granted to decide whether

due process of law is denied by a school suspension

hearing from which the parents and child in

volved are denied the assistance of a person of

their own choosing ...................................................... 15

Conclusion .......................................................................... 24

Appendix A la

Appendix B ....... ................ ....................... ........... ............... 25a

Appendix C .......................................................................... 68a

T able of Cases

Anonymous v. Baker, 360 U. S. 287 (1959) ..............—- 22

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia ex rel.

Virginia State Bar, 377 U. S. 1 (1964) ....................... 11

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) .... 11

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F. 2d

150 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied, 368 U. S. 930 .......22, 23

Oarrity v. New Jersey, 385 U. S. 493 (1967) ................. 8

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S. 335 (1963) ............... 11

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U. S. 12 (1956) ............................... 11

Hannah v. Larche, 363 IT. S. 420 (1960) ..........................- 22

In Re Gault, 387 U. S. 1 (1967) ............ .......................... 15

In Re Groban, 352 U. S. 330! (1957) ....... ...... .................. 22

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458 (1938) ....................... 17

Kent v. United States, 383 U. S. 541 (1966) ...............21-22

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U. S. 1 (1964) ............................... 22

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ....................... 11

Niznih v. United States, 173 F. 2d 328 (6th Cir. 1949) 22

Opp Cotton Mills v. Administrator, 312 U. S. 126 (1941) 18

XI

PAGE

Ill

PAGE

Powell v. Alabama, 287 IT. S. 45 (1932) ........................... 19

United Mine Workers of America, Dist. 12 v. Illinois

State Bar Association, 389 U. S. 217 (1967) ............... 11

United States v. Pitt, 144 F. 2d 169 (3rd Cir. 1944) .... 22

United States v. Sturgis, 342 F. 2d 328 (3rd Cir. 1965) 22

Wasson v. Trowbridge, 382 F. 2d 807 (2d Cir. 1967) .... 23

Constitutional P rovisions, Statutory P rovisions,

and R egulations Involved

U. S. Const., Amend. X IV ......................... 2, 3, 8, 9,10,18, 23

New York Const., Art. I § 6 ............ .................................. 19

28 U. S. C. $1254 (1) ....................... ..................................... 2

Criminal Justice Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 552, 18 U. S. C.

$3006 A .............................................................................. 11

Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 508 ........... 11

Economic Opportunity Act amendments of 1967, §222,

81 Stat. 672 ...................................................................... 12

New York City Board of Education, General Circular

No. 16 .................................................................... 3 ,5,7,9 ,17

New York Education Law §3212 ......................................... 3

New York Education Law §3214...............................3, 7, 8,17

New York Family Court Act §312 .................................. 3

New York Family Court Act §332 .................................. 3

New York Family Court Act §334 .................................. 8

New York Family Court Act §343 .................................. 8,18

New York Penal Law §280 ................. 3

Selective Service Regulation 1604.71 (d) 22

IV

Other A uthorities

PAGE

Cahn and Calm, The War on Poverty: A Civilian Per

spective, 73 Yale L. J. 1317, 1336-1337 (1964) .........12,13

Carlin and Howard, Legal Representation and Class

Justice, 12 U. C. L. A. L. Rev. 381 (1965) ................... 13

Conference Proceedings, The Extension of Legal Ser

vices to the Poor (1964) ...............................................H> 12

Handler, Controlling Official Behavior in Welfare Ad

ministration, 54 Calif. L. Rev. 479 (1966) ...............

Hentoff, Our Children Are Dying ....... ....... ...................

Kohl, 36 Children ......................................-.......................

Kozol, Death at an Early A g e ...........................................

Madder, A Report on the “ 600” Schools: Dilemmas,

Problems and Solutions ................................................ 1

National Conference on Law and Poverty, Bibliography

of Selected Readings in Law and Poverty, in Con

ference Proceedings (1965) ........................................... 11

Neighborhood Law Offices: The New Wave in Legal

Services for the Poor, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 805 (1967) 12

Office of Economic Opportunity, First Annual Report

of the Legal Services Program to the American Bar

Association (1966) ........................................................ H> 12

Office of Economic Opportunity, The Poor Seek Jus

tice (1967) ........................................................................

Office of Juvenile Delinquency and Youth Develop

ment, U. S. Department of Health, Education and

Welfare, Neighborhood Legal Services—New Dimen

sions in the Law (1966) .................................................. 4

V

Reich, Individual Rights and Social Welfare: The

Emerging Legal Issues, 74 Yale L. J. 1245 (1965) .... 13

Reich, The New Property, 73 Yale L. J. 733 (1964) .... 13

Sparer, The Welfare Client’s Attorney, 12 U. C. L. A.

L, Rev. 361 (1965) ................ .......................................... 13

Symposium: Law of the Poor, 54 Calif. L. Rev. 319-

1014 (1966) ...................................................................... 11

Time, January 20, 1967, p. 18 ........................................ 14

PAGE

I n t h e

§>npx?m? Glaurt a! tip? Intttfi States

October T erm, 1967

No.............

V ictor Madera, R amiro Madera, Manuela Madera, and all

other persons similarly situated,

Petitioners,

—v.-

B oard of E ducation of the City of New Y ork, Bernard

E. Donovan as Superintendent of Schools of the City

of New York, T heresa Rakow as District Superinten

dent of Public Schools for District One in the City

of New York.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Second Circuit, entered in the above entitled case on

December 6, 1967.

2

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Second Circuit is reported at 386 F. 2d 778 (1967)

and is set forth in Appendix A, infra, pp. la-24a. The

opinion of the District Court is reported at 267 F. Supp.

356 (1967) and is set forth in Appendix B, infra, pp.

25a-67a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit was entered December 6, 1967. The

jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C.

§1254 (1).

Question Presented

At a hearing to be held at district headquarters before

a District Superintendent of the New York City public

schools a decision was to be made whether to continue

the suspension of a pupil indefinitely, return him to school,

transfer him to an educationally inferior school for dis

orderly students, or take action leading to institutionaliza

tion. Petitioners’ retained attorney from Mobilization for

Youth, Inc., a government funded anti-poverty program,

was excluded from this proceeding pursuant to a regula

tion of the board of education which permits a student

and his family to appear with an assistant of their choice

as long as the assistant is not an attorney.

Have petitioners been denied due process of law in vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment?

3

Constitutional Provisions, Statutory Provisions, and

Regulations Involved

This petition involves the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

This petition also involves New York Education Law

§§ 3212, 3214, and New York Family Court Act §§ 312, 332,

which are printed in the Appendix, infra, pp. 55a-58a.

This case also involves New York City Board of Edu

cation General Circular No. 16 which is printed in Appen

dix C, mfra, pp. 68a-77a.

Statement

For the main thrust of the attack on poverty on the

lower East Side, New York City relies on Mobilization

for Youth, Inc. (M FY). MFY is a government funded

anti-poverty organization that attempts to provide com

prehensive social services on a neighborhood basis. It em

ploys lawyers, social workers, as well as other technical

personnel, in a variety of educational and training pro

grams to cope with the dilemmas of the community. M FY’s

Legal Services Unit is an integral part of the attempt to

deal with the social ills the neighborhood faces.

To represent indigent clients, the Legal Services Unit

has obtained the approval of the Legal Aid Committee of

the Association of the Bar of the City of New York and

the permission of the Appellate Division of the Supreme

Court of New York, as required by Section 280 of the

New York Penal Law. The unit has received funds from

the Federal Government and the Ford Foundation. MFY

4

received its first grant to set up the Legal Services Unit

from the federal Office of Juvenile Delinquency and Youth

Development in November of 1963. The unit was in opera

tion by January 1964. It is generally recognized that

“ [T]he Legal Services Unit was the first successful proj

ect of its kind in the country” and the precursor of, and

the model for, the neighborhood legal services programs

that were later to spring up under the auspices of the

Office of Economic Opportunity.1 The unit was a pioneer

in the development of precedent-setting cases which affect

large numbers of the indigent and its contributions have

been significant in both criminal and civil areas. It has

long been known for its concern for the rights of juveniles.

For example, it put into operation the nation’s first pro

gram providing representation for juveniles at the police

precinct at the time of arrest.2 As an important facet of

its program, lawyers in the unit work with social workers

in a co-ordinated effort to assist community people in

resolving their problems.3

Manuela Madera, a Puerto Rican mother of four, lives

in the MFY area. She does not speak or understand Eng

lish. In early February, 1967 she and her husband Ramiro

were notified by Miss Theresa Rakow, the District Super

intendent of New York School District No. 1 that their 14

year old son, Victor, had been suspended from Public

School 22, the junior high school in which he was enrolled.

Victor was accused of striking a teacher, and was directed

1 Office of Juvenile Delinquency and Youth Development, U. S.

Department of Health, Education and Welfare, “Neighborhood

Legal Services—New Dimensions in the Law” (1966), p. 39.

2 Id. at 38.

3 Ibid.

5

to appear in Family Court on February 23, 1967 to answer

a charge of juvenile delinquency and also to attend a dis

trict superintendent’s “ suspense” hearing or “ guidance

conference” on February 17, 1967.4

The Maderas retained attorneys from the Legal Services

Unit of MFY to represent them at both the District Super

intendent’s hearing and the juvenile delinquency proceed

ings.5 When an MFY attorney notified Miss Rakow’s office

that he would appear at the February 17th suspension

hearing, on behalf of the Maderas, he was informed that

he would not be permitted to do so pursuant to regulations

of the board of education and the superintendent of

schools— specifically, General Circular No. 16 (1965-1966)

which provides that:

Inasmuch as this is a guidance conference for the

purpose of providing an opportunity for parents,

teachers, counselors, supervisors, et al., to plan edu

cationally for the benefit of the child, attorneys seek

ing to represent the parent or child may not partici

pate (Circular No. 16, infra, p. 74a).

Circular No. 16 discusses two kinds of suspensions, the

“principal suspense” (meaning by the principal of the

school) and the “ administrative suspense.” Under the prin

cipal suspense the school principal can suspend a student

from school for no more than five days. The administra

tive suspense involves more serious school problems and

4 A previous board of education Circular on school suspensions

(Circular No. 11) had designated this a “ suspense hearing” . Cir

cular No. 16 modified the name to “ Guidance and Conference” but

the change is “ not substantive in nature” . Exhibit A, Annexed to

Amended Complaint.

5 On February 28, 1967, the claim that Victor was a juvenile

delinquent was dismissed by the Family Court, 267 F. Supp. at 359.

6

threatens long term interruption of a child’s education.

Deliberations and decisions involving administrative sus

pensions are carried on at a District Superintendent’s of

fice after referral hy the school principal, and it was from

a hearing to consider this latter form of suspension that

the MFY attorney was barred. Petitioners have at no

time challenged any aspect of the principal suspense as a

normal incident of intraschool discipline. Such short term

suspensions are no part of this case.

When it became clear that counsel would be barred from

the hearing, petitioners’ attorneys obtained a temporary

restraining order in the district court prohibiting the

school officials from proceeding with the hearing unless

plaintiffs’ counsel could be present and participate. Sub

sequently, the parties proceeded in the district court with

a hearing on petitioners’ motion for a preliminary injunc

tion which was consolidated with the trial on the merits.

The district court made extensive findings of fact as to

the nature of the hearing and what was at stake for the

pupil and parents involved, and permanently enjoined

school officials from holding “ administrative suspense”

hearings from which attorneys were excluded.

The district court found that at the conclusion of the

District Superintendent’s hearing, the school authorities

made decisions of very serious consequence for the child.

The District Superintendent decides whether to return the

student to the school in which he is enrolled, transfer him

to another school, or require him to continue under sus

pension. Some students under suspension were deprived

of schooling for as much as ten months. The court found

that in many cases the indefinite prolonged suspensions

resulting from the District Superintendent’s hearing were

the equivalent of expulsions, 267 F. Supp. at 369. School

7

records indicated that following a District Superintendent’s

hearing some students who were beyond the school leaving

age were “ discharged” or released by school authorities,

Court’s Exhibits 1-17.

In addition, the court found that the District Superinten

dent could have the pupil transferred to one of New York’s

special day schools for “ socially maladjusted” children—

popularly known as “ 600” schools because of their former

numerical designations. The district court, on the basis of

expert testimony, found that the “ 600” schools were an

inferior, ethnically segregated class of schools and that a

social stigma attached from placement in one of them.

While under the New York statutory scheme a child cannot

be placed in one of these special schools without parental

“ consent,” the district court dismissed such consent as

wholly illusory since the same New York statute also re

quires that should the parents refuse to give their consent

in writing they “ shall” be proceeded against for violating

their statutory duty to see to the pupil’s attendance at

school, N. Y. Educ. Law §§ 3214-5(a), 3214-5(c).

In addition to these immediate dispositions at the con

clusion of the hearing, the District Superintendent can

make referrals of the pupil which have significant educa

tional consequence. The Bureau of Child Guidance (BCG)

may determine that a student requires medical suspension,

home instruction or exemption from school attendance.

The Bureau of Attendance to which a referral may also

be made, may proceed with court action. “ In the latter

instance, school personnel will make themselves available

for testimony in court” (Circular No. 16, infra, p. 75a).6

6 Both the district court and court of appeals were dubious of the

admissibility of any statements made at the hearing in a subsequent

8

Such, referrals may result in institutional placement.

The New York City Board of Education runs schools in a

large number of residential institutions and hospitals and

school officials have the authority to order a student found

to be habitually truant, irregular in attendance, “ insub

ordinate” or “ disorderly” to be instructed “under confine

ment” for a period of up to two years, N. Y. Edue. Law

§■§ 3214-1; 3214-5a. As in the case of the “ 600” school, par

ents who refuse to accept the “ recommendation” of institu

tional placement are faced with the threat of court action.7

The district court found that these “ serious consequences” ,

made the exclusion of attorneys from a school suspension

hearing a violation of the Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment. The court permanently enjoined school

officials from enforcing the “no attorneys” provision in their

regulation relating to the suspension of children attending

public school.

On appeal, the court of appeals for the Second Circuit

reversed, vacated the injunction, and dismissed the corn-

court proceeding. However, neither court doubted that the dis

position of the guidance conference is admissible in a subsequent

court action. Section 334 of the Family Court Act, cited by the

court of appeals as barring statements made in a “ preliminary con

ference” from an adjudicatory Family Court hearing or criminal

action seems only to apply to a preliminary conference in the

Family Court action, and has no reference to conferences of other

agencies for other purposes—such as a school guidance conference.

The district court based its doubt on admissibility upon Garrity v.

New Jersey, 385 U. S. 493 (1967). What a Bureau of Attendance

officer could validly report in a subsequent court action concerning

the proceedings in a guidance conference is not clear.

7 Adamant parents who refuse to consent and find themselves in

Family Court defending a neglect charge do have the benefit of

counsel and the airing of the issues in a judicial tribunal (Family

Court Act, § 343). However, those parents who are intimidated by

the threat of a neglect proceeding unwillingly “ consent” to their

child’s institutional placement.

9

plaint. The appellate court did not share the view of the

district court as to the seriousness of the consequences of

the District Superintendent’s hearing. It expressed the

view that “ the rules, regulations, procedures and practices

disclosed on this record evince a high regard for the best

interest and welfare of the child.” The court was of the

opinion that “ law and order in the classroom should be the

responsibility of our respective educational systems” ; that

due process of law does not require the presence of coun

sel; and that a social worker who is allowed to attend the

hearing “ would provide more adequate counsel to the child

or parents than a lawyer.” 386 F. 2d at 788.

How the Federal Question Was Raised

and Decided Below

The question of whether in a school suspension hearing

which threatened loss of liberty and the right to public edu

cation the parents and child involved were entitled to an

assistant of their choice was raised throughout proceed

ings in the district court. 267 F. Supp. at 362. The district

court decided that the “ no attorneys” provision of board

of education Circular No. 16 violated the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

On December 6, 1967, the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Second Circuit reversed the district court

holding that the regulation of the board of education exclud

ing attorneys did not violate the Due Process Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. 386 F. 2d at 789.

10

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W RIT

I.

The restriction on the role o f the lawyer in this case

raises an issue o f national importance in that it severely

impairs effective protection o f the legal rights o f the

poor.

This case involves Victor Madera, a 14 year old Puerto

Rican youth who was suspended from school for allegedly

striking a teacher. He and his parents were summoned to

appear before district school officials for a hearing to de

termine Victor’s educational future. The family secured

the assistance of an attorney with Mobilization for Youth,

Inc., a neighborhood anti-poverty organization, but when

the attorney sought to participate at the hearing he was

informed that attorneys are excluded by board of education

policy.

The question here is whether consistent with the Four

teenth Amendment Due Process Clause a board of educa

tion may bar an attorney from a proceeding at the school

district level which will have profound consequences for

the future of a public school student, although any non

attorney advisor may be present. The court of appeals

upheld the exclusion of counsel because of what, petitioners

submit, is a dangerous misconception of the lawyer’s role

and the nature of the proceeding at which his assistance

was sought. Its decision is at odds with national efforts to

provide the poor with legal resources necessary to protect

their rights to procedural due process and their ability to

obtain fair treatment from government officials.

11

Recent years have witnessed increased concern for the

legal rights of the poor and a growing awareness of the

need to provide legal services to enable them to protect

themselves. This interest has been stimulated by and re

flected in decisions of this court,8 federal legislation,9 na

tional conferences,10 and a burgeoning legal literature.11

One of the most significant contributions to providing legal

services for the iwor has been the creation of local legal

services juojects under the federal Office of Economic

Opportunity (OEO). The growth and proliferation of these

neighborhood legal services projects evinces a strong na

tional commitment to providing the j>oor with the resources

necessary to eoxoe with modern bureaucratic society.

This commitment reaches far beyond representation of

the criminally accused. Indeed, federally funded legal ser

8 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954); Griffin v.

Illinois, 351 U. S. 12 (1956) ; and Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S.

335 (1963). Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia ex rel.

Virginia State Bar, 377 U. S. 1 (1964); NAACP v. Button, 371

II. S. 415 (1963) ; United Mine Workers of America, Dist. 12 v.

Illinois State Bar Association, 389 U. S. 217 (1967).

9 E.g., the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 508, and

the Criminal Justice Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 552, 18 U. S. C. § 3006 A.

ln E.g., National Conference on Law and Poverty, Washington,

D. C., June 23-25, 1965, under the Co-Sponsorship of the Attorney

General and the Director of the Office of Economic Opportunity;

The Extension of Legal Services to the Poor, Washington, D. C.,

November 12, 13, 14, 1964, under the Sponsorship of the U. S.

Department of Health, Education and Welfare; National Confer

ence on Bail and Criminal Justice, Washington, D. C., May 27-29,

1964 under the Co-Sponsorship of the U. S. Department of Justice

and the Vera Foundation.

1J See e.g., Symposium: Law of the Poor, 54 Calif. L. Rev. 319-

1014 (1966) ; Bibliography of Selected Readings in Law and Pov

erty, in Conference Proceedings, National Conference on Law and

Poverty (1965).

12

vice to the poor offices may not now handle criminal cases.12

And, in fact, lack of legal protection in the criminal area

constitutes only a small part of the vulnerability of the

poor.13

Neighborhood lawyers serving the poor are taking on

more than the traditional tasks of courtroom representa

tion.. They are instrumental in educating their clients to

the fact that the machinery of government is intended for

their use—that the law can work for the poor as well as

against them.14 They serve as negotiators for the commu

12 §222 of Economic Opportunity amendments of 1967, 81 Stat.

672.

13 As the Attorney General of the United States observed in

1964:

In the final analysis, poverty is a condition of helplessness—

of inability to cope with the conditions of existence in our

complex society. We know something about that helplessness.

The inability of a poor and uneducated person to defend him

self unaided by counsel in a court of criminal justice is both

symbolic and symptomatic of his larger helplessness.

But we, as a profession, have backed away from dealing with

that larger helplessness. We have secured the acquittal of an

indigent person—but only to abandon him to eviction notices,

wage attachments, repossession of goods and termination of

welfare benefits . . . it is time to recognize that lawyers have a

very special role to play in dealing with this helplessness. And

it is time we filled it.

Some of the necessary jobs are not very different from what

lawyers have been doing all along for government, for business,

for those who can pay and pay well.

Attorney General Robert P. Kennedy, Law Day Address, May 1,

1964, University of Chicago Law School, quoted in Calm and Cairn

“ The War on Poverty: A Civilian Perspective,” 73 Yale L. J.

1317, 1336-1337 (1964).

14 See generally Comment, “Neighborhood Law Offices: The New

Wave in Legal Services for the Poor,” 80 Harv. L. Rev. 805 (1967);

Office of Economic Opportunity, The Poor Seek Justice (1967) ;

Office of Economic Opportunity, First Annual Report of the Legal

Services Program to the American Bar Association (1966) ; United

States Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Conference

Proceedings: The Extension of Legal Services to the Poor (1964);

Office of Economic Opportunity, National Conference on Law and

Poverty (1965).

13

nity with governmental agencies not merely in litigation,

but on the administrative level with respect to welfare

assistance, public housing, and myriad other public bene

fits.13 The neighborhood lawyer performs functions which

would not necessarily require a lawyer in educated middle

class communities.16

The court of appeals rejected petitioners’ demand to

be represented in a serious matter by a neighborhood Legal

Service attorney at an administrative hearing on the ground

that the petitioners’ best interests were not served by repre

sentation by an attorney. This ruling unjustifiably deni

grates the role of all attorneys in providing the requisites

of due process whether they represent rich or poor.

If a poor, non-English speaking person’s right to be

heard is to be at all effective it must include the right to

be heard through an assistant of his own choosing. Peti

tioners do not claim that in every instance where a public

benefit is put in jeopardy, the individual concerned is en

titled to representation by counsel as a matter of con

stitutional right. This would be too rigid a response to a

problem that must be approached by a variety of means

serving a number of ends. But petitioners do claim that 15 16

15 See, Sparer, “ The Welfare Client’s Attorney,” 12 U. C. L. A.

L. Rev. 361 (1965) ; Carlin and Howard, “Legal Representation

and Class Justice,” 12 U. C. L. A. L. Rev. 381 (1965); Reich, “ The

New Property,” 73 Yale L. J. 733 (1964) ; Reich, “ Individual

Rights and Social Welfare: The Emerging Legal Issues,” 74 Yale

L. J. 1245 (1965); Handler, “ Controlling Official Behavior in

Welfare Administration,” 54 Calif. L. Rev. 479 (1966).

16 Often we are blinded to the efficacy of legal representation as

a potential route to a desired result because other modes of commu

nication, organization, pressure, and protest suffice— at least for the

middle class. Cahn and Cahn, “ The War on Poverty: A Civilian

Perspective,” 73 Yale L. J. 1317, 1344 (1964). (Emphasis sup

plied.)

14

when a citizen has someone available to assist him in deal

ing with public authorities, concerning matters of vital

personal interest, that person should not be barred, as the

board of education’s regulation requires, solely because he

happens to be a lawyer. It is an arbitrary and irrational

distinction, which if given widespread application will seri

ously undermine the attempts now being made to enable

the law to serve the poor as well as it serves the rich.

Some of the students indefinitely suspended as a result

of the District Superintendent’s hearing become dropouts,

adding to the flood of unemployed indigent youth in our

eities—and to the social problems attendant to such a flood.

As former Secretary for Health, Education and Welfare

Gardner has stated: “ the schools have been all too willing

to unload their behavior and scholastic problems on the

community in the foi’m of dropouts or expelled students.” 17 18

In all these cases the child was faced with a system, which

denied him the assistance of counsel when faced with ac

cusations by the established authorities.

Few rights could be of more importance to a maturing

youth than his right to an education and thus the procedures

which put this valuable right in jeopardy must comport

with our fundamental notions of fairness.1' Thus, although

this petition raises only a narrow question of law, that

question is of substantial public importance.

17 Time, January 20, 1967, p. 18.

18 Increasingly, the city schools are becoming institutions for our

poor and ethnic minorities, run by staffs that are middle class and

white. On matters of group values and argot there are tremendous

chasms of understanding. See, e.g., Kozol, Death at an Early Age;

Kohl, 36 Children; Hentoff, Our Children Are Dying. The

neighborhood lawyer, lately arrived as the tribune of the poor,

can be of great value' in bridging some of these chasms and estab

lishing genuine communication. In some neighborhoods he may be

the only one capable of doing so.

15

II.

Certiorari should be granted to decide whether due

process o f law is denied by a school suspension hearing

from which the parents and child involved are denied

the assistance o f a person o f their own choosing.

The district court and the court of appeals differed as to

what due process requires. The divergence flows from dis

parate views as to the nature of the hearing held by school

authorities and the seriousness of its consequences. To

the court of appeals the hearings are innocuous “ con

ferences”—preliminary investigations in which “ [T]he

most that is involved is a change of school assignment.”

386 F. 2d at 783. Its view of the nature of the hearing

is based in large part on an affidavit of the superintendent

of schools.19 The language of the affidavit is reminiscent

of that of a pre-In Re Gault, 387 U. S. 1 (1967) descrip

tion of the purposes and procedures of a juvenile court

attempting to justify why due process should not apply.

In the Gault case this Court found that there was a

definite “ gap between rhetoric and reality” in the juve

nile court system, 387 U. S. at 30. After observing and lis

tening to extensive testimony from parents, social workers,

and educational experts who had actually been involved in

suspension hearings, the district court came to a similar

19 386 F. 2d at 782. “ The conference is conducted in an atmos

phere of understanding and cooperation, in a joint effort involving

the parent, the school, guidance personnel and community and re

ligious agencies. There is never any element of the punitive, but

rather an emphasis on finding a solution to the problem.” Though

he recites the theory of the “ Guidance Conference” in detail, there

is no indication in the record that the Superintendent of Schools

has even ever attended a suspense hearing or “ Guidance Confer

ence.”

16

conclusion about the harsh reality of New York City sus

pension hearings. Not only did the district court refuse

to accept the benign description of the ambience and pro

cedures put forward by school officials, but it differed with

them as to the seriousness of the consequences of such

hearings. As a direct result of the District Superinten

dent’s conference a child may be returned to a regular

public school setting or he may be suspended indefinitely.

The district court found that some children are kept out

of school the equivalent of an entire school year— or longer,

267 F. Supp. at 371. Despite the child’s right to an edu

cation under New York law, in most cases of prolonged,

indefinite suspension, there is no home instruction or alter

native form of education offered by the school authorities.

The youth who attains the school leaving age while on sus

pension and who was sceptical about the value of an edu

cation has little incentive to return to the classroom.

Others who have passed the school leaving age are simply

released or “ discharged,” by school officials. Under these

circumstances, the district court properly viewed these pro

longed indefinite suspensions as the “ functional equivalent”

of expulsion, 267 F. Supp. at 369.

Another direct consequence of the hearing is possible

placement in a “ 600” school or “ school for socially malad

justed children.” To characterize this disposition as a mere

“ change of school assignment,” as did the court of appeals,

is unjustifiable in the face of both oral testimony and the

written report of an educational expert, hired by the board

itself to make a study of the “ 600” schools, to the effect

that these schools are “ ethnically segregated, inconven

iently located, undersupported, organizationally unstable

and unable to meet the needs of its student body.” Dr.

Bernard Mackler, “ A Report on the ‘600’ Schools: Di

17

lemmas, Problems and Solutions,” pp. 4-5. In short, as a

consequence of a District Superintendent’s hearing a child

risks the educational disadvantage (as well as social

stigma) that comes from placement in inferior schools

operated for misfits. School officials must obtain parental

consent before placing a child in such a special day school,

N. Y. Education Law §3214-5(a), but the statute also pro

vides that should the parents fail to consent in writing,

they “ shall” be proceeded against for neglect, § 3214-5 (c)

(1). Such consent, as the district court found, is wholly illu

sory and lacks those elements of voluntariness recognized as

“ consent” in law. Cf., Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458

(1938).

Both the district court and the court of appeals agreed

that these consequences result from the District Superin

tendent’s hearing—they differed as to their seriousness.

It is clear, therefore, that the hearing is not merely a pre

liminary investigatory procedure but rather an accusa

tory-adjudicatory proceeding in which, as required by

Circular No. 16, “ findings” and a “ decision concerning the

disposition of the case” are made. General Circular No. 16,

mfra, p. 75a.

As a result of the hearing or “ guidance conference” the

District Superintendent may also refer the student’s case

to the Bureau of Child Guidance or other agencies for study

and recommendation, or to the Bureau of Attendance for

court action. Such referrals to the BCG or related agen

cies may result in institutional placement. As in the case

of the “ 600” school, parents who refuse to accept the

“ recommendation” of institutional placement are faced

with the threat of court action, N. Y. Education Law

§§3214-5(a); 3214-5(c). Parents who are coerced by this

18

threat find their children institutionalized without further

opportunity for a hearing. There may be further investi

gations and decisions after a referral by the District Super

intendent to the BCG, see 386 F. 2d at 785, but there is

no subsequent opportunity for a hearing?0 Opp Cotton

Mills v. Administrator, 312 U. S. 126, 152-53 (1941).

While the court of appeals concluded that the conse

quences of the hearing would be “ limited” it conceded

that “ any action that would effectively deny an education

must meet the minimal standards of due process” within

the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment. 386 F. 2d at

784. The court considered the question of whether due

process permits exclusion of retained counsel on this basis

and rejected petitioners’ contention on the grounds that

the right to representation is not an essential ingredient of

a fair hearing.

If the Maderas’ right to be heard is, however, to be

more than a hollow formality, they must he permitted to

be heard by and through an assistant of their own choos

ing—including the neighborhood lawyer. More than three

decades ago, this Court observed, concerning both civil and

criminal matters that

“ The right to be heard would be, in many cases, of

little avail if it did not comprehend the right to be

heard by counsel. Even the intelligent and educated 20

20 The only exception, of course, would be where the parent and

child are proceeded against in Family Court for refusal to comply

with board of education school requirements, in which case they

would be assured of proper procedural safeguards including coun

sel, Family Court Act § 343.

Thus, contrary to the court of appeals’ disclaimer (386 F. 2d at

788) the question of what due process requires before a child is

expelled from sehool or sent to a special day or residential school

was before the court.

19

layman has small and sometimes no skill in the science

of law . . . He lacks both the skill and knowledge ade

quately to prepare his defense, even though he have

a perfect one. He requires the guiding hand of counsel

at every step in the proceedings against him. With

out it, though he be not guilty, he faces the danger of

conviction because he does not know how to establish

Ms innocence. I f that be true of men of intelligence,

how much more true is it of the ignorant and illiter

ate, or those of feeble intellect.” Powell v. Alabama,

287 U. S. 45, 68-69 (1932).

It is erroneous to conclude that the language of Powell

is irrelevant, as did the court of appeals, because school

suspension hearings do not involve “ cases” or “ courts.”

I f a tribunal—no matter what it is called—is able to make

factual findings, adjudicate issues, and impose serious dis

abilities then for purposes of aid to the uneducated lay

man, we have both a “ case” and a “ court.” It is ironic that

if the City of New York, or any other party, sued the

Maderas for the smallest sum of money, no one would

question their right to the assistance of retained counsel.

New York Const. Art. I § 6.

The poor parents and child who leave the school setting

and come to the bureaucratic headquarters downtown for

a hearing are faced with a formidable array of authorities

and experts, who know each other, speak well, are at ease

in the hearing room, and who proceed to determine what

is in their view best for the child’s future on the basis

of what is alleged to have been his conduct in the past,

A rule excluding lawyers, while allowing all others, is not

only arbitrary, capricious, and irrational in its classifica

20

tion, but prevents parents and children from having the

assistance of members of a profession especially well suited

for dealing with this type of hearing. Lawyers have a

special skill in being able to devise satisfactory resolu

tions when many competing values and interests are at

stake—a skill which school officials concerned with the best

welfare of a child should welcome.

The concern of the court of appeals that the mere presence

of a lawyer in their midst would be destructive of the pur

poses of the hearing is ill-founded. Due process does not

require a full scale judicial hearing. A lawyer at such

hearings would be limited by reasonable rules established

by the school authorities. But within this framework, the

lawyer has a valuable contribution to make—certainly as

much as the parents’ social worker, priest, or other adviser,

all of whom could have been present at the Madera hearing,

while their lawyer would be barred. Should an attorney

stray outside this framework, he would be subject to the

same reasonable controls that the board could exercise over

other types of advisers.

The opinion of the court of appeals denigrates the role

of the lawyer. Not only does it unjustifiably elevate the

effectiveness of the social worker over that of an attorney,

but it suggests that a lawyer in this situation would be

little more than a “ destructive” pettifogger—quick with

quibbles and legal niceties to clog the machinery of the

hearing, but with little positive contribution to make. On

the contrary, an attorney has the best interest of the child,

his client, at heart— as much as do school officials. He is

trained to seek creative ways to resolve the problems at

hand, maximizing alternatives and offering suggestions that

might not have occurred to the school authorities, but which

21

would be acceptable to all involved. This lias been the ex

perience of attorneys in other parts of New York State

where there is no bar to attorney participation in school

hearings, as was reported by an amicus curiae brief filed

in the court of appeals by the Nassau County Legal Ser

vices Corporation, another O.E.O. Legal Services office

which regularly represented children before school boards.

The mere presence of a lawyer would at the same time

provide an assurance of regularity and fairness in the pro

ceedings. The superintendent of schools in his affidavit filed

with the answer to the complaint in this action expressed

his opposition to the presence of an attorney as follows:

“ The attorney might assert that the improper acts of the

pupil did not occur, or that the nature of the act has

been exaggerated, or he might seek to establish ex

tenuating circumstances.” 21

I f appropriate and valid, all of these things an attorney

might and should do. Objections to an attorney’s presence

cannot fairly be bottomed upon such considerations for

the hearing officials are under an obligation to hear the

child’s version of the events and anything he has to say

by way of explanation. The board’s practice of assuming

the correctness of the accumulation of reported incidents

on the child’s anecdotal record, see, 386 F. 2d at 788, does

not “ evince a high regard for the best interest and welfare

of the child” 386 F. 2d at 789. If this evidence is impor

tant for the decision in the child’s case, it should be sub

jected, within reasonable limits, to examination, criticism,

and refutation. There is no irrebuttable presumption of

accuracy attached to staff reports. Cf., Kent v. United

21 Affidavit of Bernard E. Donovan, Superintendent of Schools.

22

States, 383 U. S. 541, 563 (1966); Hannah v. Larche, 363

U. S. 420, 489 (1960).

The authorities relied upon by the court of appeals do

not support denial of counsel to petitioners. In re Groban,

352 U. S. 330 (1957) and Anonymous v. Baker, 360 U. S.

287 (1959) are inapposite. Groban, a 5-4 decision, held that

a state could constitutionally deny a witness a right to

counsel at an investigatory hearing. Application of this

holding to the instant case is highly dubious since (1) the

Maderas are not witnesses, but principals and (2) this is

an adjudicatory, not an investigative hearing. Further

more, the pillars which supported Groban have been re

moved for the objection to exclusion of counsel was that it

impaired the privilege against self-incrimination. At the

time the privilege was not protected against state action

by the due process clause, Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U. S. 1

(1964).22

The court of appeals mistakenly read Dixon, v. Alabama

Hoard of Education, 294 F. 2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961), cert,

denied, 368 U. S. 930 (1961), as supporting the exclusion of

attorneys at a school expulsion hearing. Dixon discussed

the procedural rights deemed necessary in such hearings

22 Nor should the draft board cases, United States v. Sturgis, 342

F. 2d 328 (3rd Cir. 1965) ; Niznik v. United States, 173 F. 2d 328

(6th Cir. 1949); United States v. Pitt, 144 F. 2d 169 (3rd Cir.

1944), cited by the court of appeals, 386 F'. 2d at 787, be in any

way dispositive of the issues in this ease. This Court has never

passed upon the constitutionality of the Selective Service rule

excluding counsel at draft board hearings. What is more, these

hearings do not involve conduct that is cognizable in the criminal

or juvenile courts or determinations that result in any immediate

deprivation. Significantly, the Selective Service System provides

registrants with legal advisors who, although they deal principally

with appeals, are generally charged with assisting the registrant

in the protection of his rights. Selective Service Regulation 1604.71

(d). There is no such analogue in the New York City school sys

tem.

23

but was silent on the question of the presence of counsel.

It was concerned mainly with the issues of notice and the

right to be heard. There is nothing in Dixon standards to

indicate that a student exercising his right to be heard,

would be barred from the assistance of an attorney of his

own choosing at the hearing.23

We emphasize that to permit a lawyer under a rule that

permits all other manner of advisors to be present and

participate at the hearing at the District level is not to re

quire one in all instances. The burden on the board of

education of allowing a person to appear by counsel when

one is available is nil. I f denied the assistance of a neigh

borhood lawyer, however, the Maderas of our cities are at

a serious disadvantage before administrative bodies. The

New York City board of education regulation barring only

attorneys from District school suspension hearings where

valuable rights are in jeopardy is an arbitrary rule which

prejudices the right to be heard guaranteed by the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

23 The Second Circuit Court of Appeals has itself recognized that

the presence of counsel “as an ingredient of fairness is a function

of all other aspects of the hearing”—including the maturity and

education of the individual involved. Wasson v. Trowbridge, 382

F. 2d 807, 812 (2d Cir. 1967).

24

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, the petition for writ of cer

tiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

H arold R othwax

R obert Sugerman

Sue A nn Shay

65 East 7th Street

New York, New York

J ack Greenberg

James N. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

Leroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Petitioners

A P P E N D I C E S

la

APPENDIX A

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F or the Second Circuit

No. 502— September Term, 1966.

(Argued June 8, 1967 Decided December 6, 1967.)

Docket No. 31346

V ictor Madera, R amiro Madera and

Manuela Madera,

Plaintiff s-Appellees,

— against—

B oard of E ducation of the City of New Y ork, B ernard

E. D onovan, as Superintendent of Schools of the City

of New York, T heresa S. R akow, as District Superin

tendent for District One in the City of New York,

Defendants-Appellants.

----------*----------

B e f o r e :

Moore, F riendly and A nderson,

Circuit Judges.

______ fy____ __

Appeal from an order entered on April 11, 1967, in the

United States District Court for the Southern District of

New York, Constance Baker Motley, Judge, enjoining ap

pellants from conducting a District Superintendent’s Guid

ance Conference to consider the situation of a child sus

pended for disciplinary reasons without affording the child

and his parents the right to be represented by legal counsel.

2a

Opinion reported, 267 F. Supp. 356 (S. D. N. Y. 1967).

Judgment reversed; injunction vacated and complaint dis

missed.

J ohn J. L oflin, Office of the Corporation Coun

sel, City of New York (J. Lee Rankin, Cor

poration Counsel, and Luis M. Neco, of

counsel), for defendants-appellants.

R obert Sugarman, New York, N. Y. (Harold

J. Rothwax and Sue Ann Shay, New York,

N. Y., on the brief), for plaintiffs-appellees.

David I. A she, R obert Carter, W illiam Chis

holm, K enneth W . Greenawalt, David

Haber, Herbert A. H eerwagen, R hoda H.

K arpatkin, W hitman K napp, R ichard L.

Levinson, L eah Marks, Stephen M. Nag-

ler, B urt Neuborne, Gregory J. P errin,

Carl R achlin, George Schiffer, W illiam

A. W hite, and R ay H. W illiams, New York,

N. Y. (Rhoda Karpatkin, Leah Marks, Carl

Rachlin, Stephen M. Nagler, of counsel),

for American Jewish Congress, New York

Metropolitan Council, et al., as amici curiae.

John DeW itt Gregory, Mineola, N. Y. (Allen

Redlich, Syosset, N. Y., of counsel), for

Nassau County Law Services Committee,

Inc., as amicus curiae.

Lubell and Lubell, New York, N. Y. (Jonathan

W. Lubell and Stephen L. Fine, New York,

N. Y., of counsel), for New York City Chap

ter of the National Lawyers Guild as amicus

curiae.

3a

R obert P rojansky, New York, N. Y., for Harlem

Social Workers’ Action Committee as ami

cus curiae.

V ladeck, E lias, F rastkle, V ladeck & L ewis,

New York, N. Y. (Max H. Frankie, Everett

E. Lewis, and Zachary Wellman, Newr York,

N. Y., of counsel), for Council of Super

visory Associations as amicus curiae.

----------* ----------

Moore, Circuit Judge:

On February 2, 1967, plaintiff, Victor Madera, was a

14-year-old student in the seventh grade in Junior High

School No. 22, District No. 1 of the New York City public

school system. On that date, after a period of more than

a year of behavioral difficulties, Victor was suspended from

school by the principal. Victor’s principal notified the

District Superintendent of District No. 1, Miss Theresa

Rakow, of the suspension. Miss Rakow notified Victor’s

parents, requesting their presence at a Guidance Confer

ence to be held in her office on February 17, 1967, with

regard to Victor’s suspension.

After Victor’s parents received the notice, they sought

the aid of legal counsel who wrote to Miss Rakow asking

to appear on behalf of Mr. and Mrs. Madera and their son

at the conference. Miss Rakow’s office advised the attorney

that he could not attend the conference. General Circular

No. 16 (1965-1966), promulgated by the Board of Educa

tion of the City of New York and the Superintendent of

Schools, provides:

“ Inasmuch as this is a guidance conference for the pur

pose of providing an opportunity for parents, teachers,

counselors, supervisors, et al., to plan educationally

4a

for the benefit of the child, attorneys seeking to rep

resent the parent or child may not participate” (page

5).

On February 16, 1967, the Maderas sought and obtained

a temporary restraining order from the district court, re

straining appellants:

“ From holding any proceeding at which the plaintiffs

may be affected and, particularly, from conducting

the ‘Assistant Superintendent’s Hearing’ scheduled

for February 17, 1967, without permitting plaintiffs’

legal counsel to be present and to perform his tasks

as an attorney.”

After a trial, the district court issued a permanent in

junction and held that “ the right to a hearing as a due

process requirement [is] of such constitutional signifi

cance as to void application of defendants’ ‘no attorneys

provision’ to the District Superintendent’s Guidance Con

ferences.” 267 F. Supp. at 373. Defendants, the Board of

Education, have appealed the issuance of that injunction.

Pending the decision of the appeal, this Court on May 1,

1967, granted a stay.

At the very outset it should be made clear what this

case does not involve. First, the Guidance Conference is

not a criminal proceeding; thus, the counsel provision of

the Sixth Amendment and the cases thereunder are in

applicable. Second, there is no showing that any attempt

is ever made to use any statement at the Conference in

any subsequent criminal proceeding. The record is to the

contrary (186-87),1 and the district court so found, 267

The numbers refer to pages of the stenographer’s minutes of the

trial.

5a

F. Supp. at 372. Therefore, there is no need for counsel

to protect the child in his Fifth Amendment privilege

against self-incrimination.

The issue is one of procedural “ due process” in its

general sense, free from the “ specifics” of the Fifth and

Sixth Amendments. What constitutes due process under

any given set of circumstances must depend upon the na

ture of the proceeding involved and the rights that may

possibly be affected by that proceeding. Cafeteria and

Restaurant Workers Union v. McElroy, 367 U. S. 886, 895

(1961). Thus, it will be necessary to describe the nature

and purpose of the District Superintendent’s Guidance

Conference in some detail.

Article XI, Section 1 of the New York Constitution

states that “ the legislature shall provide for the mainte

nance and support of a system of free common schools,

wherein all the children of this state may be educated.”

In New York, a person over five and under twenty-one is

“ entitled” to attend the free public schools in the school

district or city in which he resides. §3202(1), New York

Education Law. Attendance at school is a statutory re

quirement for minors between the ages of seven and six

teen. §3205(1), Education Law.

The suspension of a pupil who is insubordinate or dis

orderly or who endangers the safety or morals of himself

or other minors, is authorized by section 3214(6) of the

Education Law.2 There are two kinds of suspensions, the * 1 2

2 Section 3214-6 provides:

6. Suspension of a minor, a. The school authorities, the super

intendent of schools, or district superintendent of schools may suspend

the following minors from required attendance upon instruction:

(1) A minor who is insubordinate or disorderly;

(2) A minor whose physical or mental condition endangers the

health, safety, or morals of himself or of other minors;

( continued on follow in g page )

6a

“ principal suspense” (meaning by the “ principal” of a

school) and the “ administrative suspense.” Under the

principal suspense the school principal has the authority

to suspend the child from classes for a period of no more

than five days. Generally, the principal tries to meet with

the parents of the child to try to solve the problem before

the suspension, but sometimes the situation requires an

immediate suspension with a later conference before the

child is returned to school. Normally, a principal sus

pense does not require any consideration by the District

Superintendent (168-170).

If the principal feels that a simple suspension will not

solve the problem., he may suspend the child and refer

the suspension to the District Superintendent. This is

what is referred to as an “ administrative suspense,” a

suspense which remains in effect pending an adminis

trative decision. Section 3214(6) (b) vests the responsi

bility for dealing with the suspended child with the Dis

trict Superintendent. There is no statutory requirement

that a parent be granted a hearing prior to invoking this

power. Cosme v. Board of Education, 50 Misc. 2d 344,

270 N. T. S. 2d 231 (1966), affirmed without opinion,

27 App. Div. 2d 905 (1st Dept. 1967). Section 3214-5(a)

requires only that a hearing be held prior to sending a

child to a special day school or to confinement. However, 3

(3) A minor who, as determined in accordance with the provisions

of part one of this article, is feebleminded to the extent that he

cannot benefit from instruction.

b. Procedure after suspension. In the case of a minor who is

suspended as insubordinate or disorderly, immediate steps shall be

taken for his commitment as provided in this section, or for his

attendance upon instruction elsewhere; in the case of a minor

suspended for other cause, the suspension may be revoked whenever

it appears to be for the best interest of the school and the minor

to do so.

7a

pursuant to procedure promulgated by the Board of Edu

cation of the City of New York and the Superintendent

of Schools and distributed in General Circular No. 16,

hearings, or “ Guidance Conferences,” relating to the sus

pension are held in all cases. The principal, after suspend

ing the student, notifies the parents that a conference will

be held and the District Superintendent’s office notifies

them of the date of the conference.

In attendance at the Guidance Conference are the child

and his parents, the principal, the guidance counselor of

the suspended child’s school, the District Superintendent,

her assistant, the guidance counselor assigned to her office,

and the school-court coordinator assigned to the district.

If the parents do not speak English, they may bring an

interpreter with them or one will be provided. In addi

tion to his parents, the suspended child may have a rep

resentative from any social agency to whom the family

may be known, attend the Guidance Conference. Students

and their parents have never been represented at any of

these Conferences by counsel (184-85).

The function of the school-court coordinator is to pro

vide a liaison between the Family Court and the schools.

He interprets to the court “ the program and facilities”

of the school and he “ interprets to the school the deci

sions of the court and the recommendations of the courts”

(171). In some cases the Family Court may make use of

the District Superintendent’s decision at the Guidance Con

ference, and when requested to do so by the court, it is

the school-court coordinator who takes this information

to the court. In such a case, the court would receive only

the school record of the child containing the fact that the

child had been suspended and some notation as to where

he had been transferred or where he had been placed

8a

after the suspense (355-56). Apparently as a matter of

convenience, the school-court coordinator will also take

notes at the Guidance Conference (180). However, it is

clear that no statements made during such a preliminary

conference could be admitted into evidence at any adju

dicatory hearing before the Family Court. Section 334

of the Family Court Act provides that “ No statement

made during a preliminary conference may be admitted

into evidence at an adjudicatory hearing under this act

or in a criminal court at any time prior to conviction.” 3

The District Superintendent’s guidance counselor co

ordinates the activities of the District Superintendent’s

office with the Bureau of Child Guidance. The guidance

counselor takes notes and keeps records of the Guidance

Conference. When the ehild returns from suspension, the

guidance counselor helps to place him in the proper school

situation (172).

At the Guidance Conference it is made clear to the

parents and the child that it is not intended to be puni

tive, but it is, rather, an effort to solve his school prob

lems. Each one present, including the child if he is old

enough, is asked what he thinks should be done and con

tributes to the discussion. Sometimes either the parents

or the child will be asked to step outside for a moment so

that one might discuss problems that would be difficult

to discuss in front of the other (173-74).

“ The sole purpose of the conference is to study the

facts and circumstances surrounding the temporary

suspension of this student by his school principal, and

to place the child in a more productive educational

3 Parenthetically, it may be noted that in the Family Court where a

charge of juvenile delinquency was made by a teacher, Victor was

represented by counsel, a right given by section 728 of the New York

Family Court Act.

situation. At these conferences the assistant super

intendent interviews the child, his parents and school

personnel to learn the cause of the child’s behavior.

The conference is conducted in an atmosphere of

understanding and cooperation, in a joint effort in

volving the parent, the school, guidance personnel and

community and religious agencies. There is never

any element of the punitive, but rather an emphasis

on finding a solution to the problem.

“ After full and careful study and discussion a plan

is formulated to deal more adequately with the prob

lems presented by the child. Every effort is bent

towards the maintenance of a guidance approach. The

emphasis is on returning the child as rapidly as pos

sible to an educational setting calculated to be most

useful to him.” 4

At the very beginning of the conference, the District Su

perintendent’s staff may gather to go over the school rec

ords and background of the case before the parents and

child arrive, but the parents are asked what they think

should be done with the child and “ no decision is made

until the parent and child have participated” (303).

It is important to note that there are only three things

that can happen to a student as a direct result of the

District Superintendent’s conference:

1. The suspended child might be reinstated in the same

school, in the same or a different class, or

2. The suspended child might be transferred to another

school of the same level, or

4 Affidavit of Bernard E. Donovan, Superintendent of Schools.

10a

3. The suspended child—but only with the parents’ con

sent—might be transferred to a special school for socially

maladjusted children (Gen. Circular No. 16).

Schools for socially maladjusted pupils (formerly known

as “ 600” schools) were established about eighteen years

ago. They are schools which are provided with special

services for rehabilitation of children who are socially

maladjusted or are problem children. These schools have

smaller classes, specially trained teachers and special pro

grams. More money is allocated to them so that they are

able to provide more equipment and field trips for the

children (100-101). There is evidence that these schools

are presently inadequate to meet the needs of the New

York public school system,5 but no practical alternative

has been offered for educating the disruptive child (445-

51). It is undoubtedly true that a certain social stigma

attaches to being placed in a school for socially malad

justed children. But this is true of many decisions of

educational placement, such as, deciding not to promote

a child or to remove him from a rapid advancement class

or even the decision to give him a low or failing mark.

Furthermore, the only schools for socially maladjusted

children to which the District Superintendent could refer

a child after a Guidance Conference are those which pro

vide for attendance during regular school hours as in any

other school (236). In deciding as to which school to refer

the child, an effort is made to reduce any stigma by send

ing him to a school out of the neighborhood if possible

(246).

Thus, aside from a decision that the child should be

returned to the school he has been attending, the District

5 Dr. Bernard Mackler, A Report on the “600” Schools: Dilemmas,

Problems, and Solutions (Plaintiff’s Exhibit 3).

11a

Superintendent is only authorized finally to decide that

the child he transferred to another school. The most that

is involved is a change of school assignment. However,

after the Guidance Conference, the District Superintend

ent may also:

4. Refer the student’s case to the Bureau of Child

Guidance or other social agency for study and recommen

dation, or

5. Refer the case to the Bureau of Attendance for court

action (Gen. Circular No. 16).

I f the compulsory school attendance law, §3205, Educa

tion Law, is being violated, it is the responsibility of the

Bureau of Attendance to take the matter to the Family

Court. If, after the guidance conference, the District Super

intendent determines that the child should be enrolled in a

special school for socially maladjusted children, his par

ents are told to report to that school with the child. The

written consent of the parent or person in parental rela

tion to the child, is necessary before he may be required to

attend a school for socially maladjusted children. §3214-5

(a), Education Law. However, if the parents refuse to

give such consent they may be prosecuted for violation of

the compulsory education laws. §§3214-5(c)(1), 3212-2(b).

If the child does not report for admission, the Bureau of

Attendance is notified and appropriate action is commenced

in the Family Court.

The Bureau of Child Guidance (BCG) is the “clinical

arm of the Board of Education. Its employees are social

workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists” (175). When the

District Superintendent refers a child to the BCG, it makes

a study of the child “ as seems indicated to help” the Dis

trict Superintendent or to advise her “ of what may be

12a

[the] best educational placement” (17G). The BCG has no

authority to order a particular placement for a child, but

can only recommend various alternatives to the District

Superintendent (307-08). What these alternatives are would

depend on the individual child but, in general, they are the

following:

1. The child is able to attend school but should be sent

to a school with a particular kind of program.

2. The child should be sent to a special day school for

socially maladjusted pupils or a residential institution

where the Board of Education operates such a school.

3. The child should be instructed at home.

4. The child should be temporarily exempted from school

while his parents seek institutional help.

5. The child should receive a medical suspension or ex

emption.

G. The child should be exempt from school (176).

I.

The Fourteenth Amendment prohibits a state from de

priving “ any person of life, liberty, or property, without

due process of law.” Thus it has long been clear that

where a government affects the private interest of an indi

vidual, it may not proceed arbitrarily, but must observe

due process of law. Wynehamer v. People, 13 N. Y. 378

(1856).

“ . . . The liberty mentioned in that amendment

means not only the right of the citizen to be free from

the mere physical restraint of his person, as by incar

ceration, but the term is deemed to embrace the right

of the citizen to be free in the enjoyment of all his

13a

faculties; to be free to use them in all lawful ways; to

live and work where he w ill; to earn his livelihood or

avocation and for that purpose to enter into all con

tracts which may be proper, necessary and essential to

his carrying out to a successful conclusion the pur

poses above mentioned.” Allgeyer v. Louisiana, 165

U. S. 578, 5 (1897).

It has been held that any action that would effectively

deny an education must meet with the minimal standards

of due process.

“ . . . It requires no argument to demonstrate that

education is vital and, indeed, basic to civilized society.

Without sufficient education the plaintiffs would not be

able to earn an adequate livelihood, to enjoy life to the

fullest, or to fulfill as completely as possible the duties

and responsibilities of good citizens.” Dixon v. Ala

bama State Board of Education, 249 F. 2d 150 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 368 U. S. 930 (1961).

See also Wasson v. Trowbridge, 382 F. 2d 807 (2d Cir.

1967); Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp.

174 (M. D. Tenn. 1961). These cases, however, involved an

expulsion from school. The result of the action by the

educators in an expulsion case would have been the drastic

and complete termination of the educational experience in

that particular institution.5 But no case has yet to go so

far as to hold that various trial type hearing requirements

apply to such proceedings as in the present case. The

trial court cites Woods v. Wright, 334 F. 2d 369 (5th Cir.

1964), for the proposition that “ Arbitrary expulsions and

suspensions from the public schools are also constitution

6 The K n igh t case involved an indefinite suspension which was deemed

the equivalent of an expulsion.

14a

ally repugnant on due process grounds.” 267 F. Supp. at

373 (emphasis supplied). Although Woods did deal with

a short suspension, it was an appeal from the refusal of a

district court to grant a temporary restraining order. The

court specifically stated that the due process question was

“ not properly before us for decision.” 334 F. 2d at 374.

Furthermore the point of Woods was not procedural due

process but a violation of First Amendment rights. In the

present case, the child has already been suspended and the

determination for the District Superintendent’s Guidance

is how that child may best be returned to the educational

system. Quite the opposite of the problem in Wasson,

Dixon, Knight, and Woods, supra.

As noted above, it is the school principal that initially

issues the administrative suspense. After this preliminary

suspension, aside from a decision that the child should re

turn to the school he has been attending, the District Super

intendent’s Guidance Conference is only authorized finally

to decide whether or not he should be transferred to an

other school. At most what is involved would be a change

of school assignment.

The court below found that “ a ‘Guidance Conference’

can ultimately result in loss of personal liberty to a child

or in a suspension which is the functional equivalent of

his expulsion from the public schools or in a withdrawal

of his right to attend the public schools.” 267 F. Supp. at

369 (emphasis supplied). The difficulty with this holding

is, of course, the word “ ultimately.” The trial court by a

series of hypothetical assumptions, in effect, turned a mere

Guidance Conference relating to Victor’s future educa

tional welfare into a quasi-criminal adversary proceeding.

The possibilities of Youth House, the Psychiatrist Division

of Kings County Hospital or Bellevue Hospital, institution

alization, or attendance enforcement proceedings were men

15a

tioned. 267 F. Supp. at 371-72. When, as and if, in the

future, Victor or his parents find themselves faced with

charges in the Family Court, there would seem to be ade

quate safeguards in the law for preservation of their con