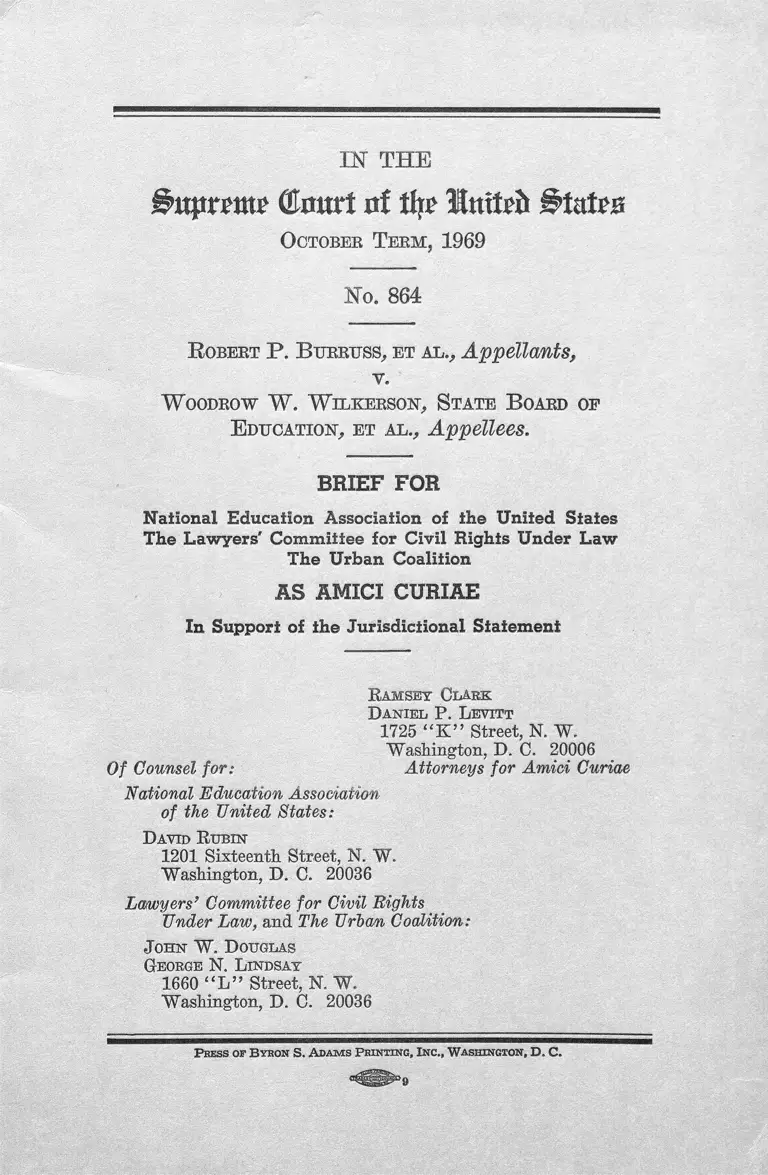

Burrus v Wilkerson Brief for Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1969

19 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Burrus v Wilkerson Brief for Amici Curiae, 1969. ebad1a2b-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f03f5b9e-1196-4a78-a88c-424487536ded/burrus-v-wilkerson-brief-for-amici-curiae. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

l&tpmtr (Emtrt itf % Intt^ BtaUz

O otobek T e b m , 1969

No. 864

R obekt P . B ttbruss, e t al ., Appellants,

v.

WOODROW W . W lLKEBSO^ STATE BOAED OP

E d u c a t io n , e t a l v Appellees.

BRIEF FOR

National Education Association of the United States

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

The Urban Coalition

AS AMICI CURIAE

In Support of the Jurisdictional Statement

Of Counsel for:

R a m s e y C l a r k

D a n ie l P . L evitt

1725 “ K ” Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20006

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

National Education Association

of the United States:

D avid R u b in

1201 Sixteenth Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Bights

Under Law, and The Urban Coalition:

J o h n W. D ouglas

G eorge N. L in d sa y

1660 “ L ” Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

P ress of B yron S. A dams Printing. Inc., W ashington, D . C.

'9

INDEX

Page

Interest oe A m i c i ............................... 1

Questions P resented ............................................................. 3

Statement oe the Ca s e ........................................................ 3

Summary oe A rg u m en t ........................................................ 5

A rgument .......................................................... 6

I. The District Court Erred in Dismissing Appel

lants’ Claim That the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment Is Violated by

Certain Specific Features of the Formula by

Which the Commonwealth of Virginia Appor

tions Its Educational Resources Between Appel

lants, on the One Hand, and Public School Chil

dren in More Affluent Urban and Suburban

Counties ................................................................... 6

II. The District Court Erred in Concluding That

the Decision in Mclnnis and Its Summary A f

firmance by This Court Insulate From Judicial

Scrutiny the Statutory Formula Challenged

Here ........................................................................... 12

Conclusion ................................................................................ 15

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases :

Bellow v. Wisconsin, No. ——, Dane County Cir. Ct.,

W is................................................................................... 12

Board of Educ. of City of Detroit, Mich. v. Michigan,

No. 103342, Circuit Ct. for Wayne County, Mich. .. 12

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954) 10

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963) ................. 11

Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S.

663, 670 (1966) ........................................................... 11

McDonald v. Board of Election, 394 U.S. 802 (1969) . . 11

PageI

Mclnnis v. Shapiro, 293 F. Supp. 327 (N.D. 111. 1968),

aff’d per curiam sub nom. Mclnnis v. Ogilvie, 394

ii Index Continued

Missouri ea; rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) 10

Rodriquez v. San Antonio Independent School District,

No. 68-175 S.A. (W.D. Tex.) ................................... 12

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) .......... ................... 10

Serrano v. Priest, No. 938254, Calif. Super. Ct. (L.A.

Co. 1969) ........................................................... .. 12

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948) .......... 10

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) .......................... 10

C o n s t it u t io n s a n d S t a t u t e s :

Appalachian Eegional Development Act of 1965, Pub.

L. 89-4, 79 Stat. 5, 40 U.S.C. App. Sec. 1 et seq. . . 7

United States Constitution: Fourteenth Amendment .. 2, 5

Virginia Acts of Assembly, 1968, Chapter 806 .............. 8

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s :

Proceedings of the 72nd Annual Meeting of the South

ern Association of Colleges and Schools, Dallas,

Texas, November 1967 ............................................. 9

United States Office of Education, Approval and Ac

creditation of Public Schools, p. 15 (1960) .......... 10

IN T H E

(Emtrt ni tip United

O ctober T e r m , 1969

No. 864

R obert P . B urruss , e t a l ., Appellants,

v.

W oodrow W . W ilk erso n , S ta te B oard of

E du catio n , et a l ., Appellees.

BRIEF FOR

National Education Association of the United States

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

The Urban Coalition

AS AMICI CURIAE

In Support of the Jurisdictional Statement1

INTEREST OF AMICI

1. The National Education Association of the United

States [NEA], founded in 1857, is a Corporation

chartered by special Act of Congress in 1906. Its

membership includes more than one million profes

sional educators. Its purpose is to improve the char

acter and advance the interests of the teaching profes-

l Counsel for Appellants have consented to the filing of this brief. Counsel

for Appellees have indicated that they do not oppose its filing.

2

sion and to promote generally the cause of education

in the United States. In furtherance of this purpose,

the Association has long worked to insure the adequate

and equitable financing of public education. For more

than a century, NEA has striven to provide equal edu

cational opportunity for all American children, in rural

as well as in urban and suburban sections of the

Nation.

2. The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Eights Under

Law, a non-profit private corporation organized in

1963, is composed of over 300 lawyers across the

country. In 1968, with the aid of a grant from the

Ford Foundation, the Committee initiated a project

to actively engage the services of lawyers in an attack

upon problems in such areas as education, housing, and

economic development. Well over 20,000 volunteer

hours have been committed to over 600 projects. In

the field of education, both national and local com

mittees have undertaken more than a score of projects

to promote quality education. For over a year, these

committees have studied, reviewed, and proposed vari

ous provisions for reform of education financing. It is

because of the importance of this case to the effort to

bring about adequate systems of education financing

that the Lawyers’ Committee urges the Court to grant

the requested relief.

3. The Urban Coalition, a private non-profit cor

poration, has established as one of its major objectives

the extension of quality education, particularly to those

students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Essential

to this task is the removal of the gross inequities result

ing from state education finance formulae which pres

ently favor suburban areas at the expense of rural and

urban areas. The present case challenges certain fea

tures of the education financing system of the Com

monwealth of Virginia. However, the factual pattern

which the case presents and the important Constitu

tional issues it raises extend to States across the Nation.

It is for this reason—because of the importance of this

case to the future of American education—that the

Urban Coalition requests this Court to grant the relief

sought by Appellants.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the District Court erred in dismissing

Appellants’ claim that the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment is violated by certain spe

cific features of the formula by which the Common

wealth of Virginia apportions its educational resources

between the public school children of Bath County and

similarly situated counties, on the one hand, and those

in more affluent urban and suburban counties.

2. Whether the District Court erred in holding that

the decision in Mclnnis v. Shapiro, 293 F. Supp. 327

(N.D. 111. 1968), aff’d per curiam sub nom. Mclnnis v.

Ogilvie, 394 U.S. 322 (1969), insulates from judicial

scrutiny the statutory formula challenged here.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Appellants filed this civil proceeding in the United

States District Court for the Western District of V ir

ginia, Harrisonburg Division, seeking declaratory and

injunctive relief with respect to the formula by which

the Commonwealth of Virginia apportions aid among

its public schools. The complaint alleged with particu

larity that the public school children of Bath County,

Virginia, and similarly situated counties [hereinafter

Appellants], were deprived of their rights under the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

4

ment as a result of the interplay of state law and the

County’s poverty.

On November 16, 1968, almost simultaneously with

the District Court decision in Mclnnis v. Shapiro, 293

F. Supp. 327 (N.D. 111. 1968), United States Dis

trict Judge Ted Dalton held that Appellants were

entitled to a three-judge court to pass upon the validity

of their claims. (J.S. App. B ) After taking testi

mony and other evidence with respect to the educa

tional situation in Bath County and its relationship to

the formula by which the Commonwealth of Virginia

apportions educational resources, the three-judge court

asked counsel for both sides to address themselves to

the decision in Mclnnis and its per curiam affirmance

by this Court, and to discuss possible judicial remedies

for the conceded educational deficiencies found in Bath

County. Counsel for appellees responded, resting their

defense squarely and exclusively upon Mclnnis. A p

pellants filed a memorandum distinguishing Mclnnis,

and proposing appropriate judicial remedies.

On May 27,1969, the three-judge court filed its opin

ion, dismissing the complaint. (J. S. App. A ) The

court conceded the existence of “ marked deficiencies

of the Bath County School physical and instructional

facilities, when compared with those of the other politi

cal subdivisions in Virginia.” (J. S. 4a) But it con

cluded, following Mclnnis, that no relief was available.

The court said that

“ [W ]e do not believe that [the deficiencies and

differences] are creatures of discrimination by the

State. Our reexamination of the Act confirms

that the cities and counties receive State funds

under a uniform and consistent plan. With this

conclusion we resolve the chief issue of the case,

and exposition of the method of computation is not

necessary. . . .

0

“ Truth is, the inequalities suffered by the school

children of Bath are due to the inability of the

county to obtain, locally, the moneys needed to be

added to the State contribution to raise the educa

tional provisions to the level of that of some of the

other counties or cities. The blame cannot be

placed on the people or the officials of the county.

Rather it is ascribable solely to the absence of tax

able values sufficient to produce the required

moneys. The tax rate and the appropriations have

been strained to afford the children better schools. ’ ’

(J. S. 4a)

SUMMARY OF ARGUM ENT

First, the state laws challenged below have the effect

of depriving Appellants of their rights under the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. (1)

These laws concededly deny to Appellants desperately

needed state supplements to teachers’ salaries, and

other forms of state assistance, which are accorded to

more affluent urban and suburban counties. (2) They

reduce Appellants to the use of educational facilities

branded “ substandard” by state authorities, which may

contribute to the system’s lack of accreditation, and

whose improvement, the Commonwealth admits, is be

yond the County’s resources. (3) And they make it im

possible for Appellants to obtain either adequate voca

tional training or a curriculum broad enough to render

graduates of the County’s schools eligible to attend

state institutions of higher learning. As a result,

Bath County’s young people are deprived of educa

tional incentive and are relegated to poorly paid

work as domestics or unskilled laborers, the County’s

Appalachian poverty is made self-perpetuating, and

the gulf between rich and poor areas of the Common

wealth is maintained and widened.

6

Second, the present case affords a timely and appro

priate vehicle for mitigating the chilling effect of the

decision in Mclnnis v. Shapiro, 293 F. Supp. 327 (N.D.

111. 1968), aff’d per cnriam sub nom. Mclnnis v. Ogilvie,

394 U.S. 322 (1969). As the present case illustrates,

the District Court decision in Mclnnis, and its sum

mary affirmance by this Court, have induced lower

federal and state courts indiscriminately to reject

efforts to measure state formulae for financing public

education by the requirements of the Equal Protection

Clause. Until this Court indicates that its summary

affirmance in Mclnnis was not intended to have this

deadening effect, litigants, whether in Appalachia or

in urban areas, will find it unduly difficult, if not im

possible, to obtain the judicial relief to which they are

entitled. We believe this ease a highly appropriate

vehicle for mitigating the overkill effect of Mclnnis.

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court erred in dismissing Appellants' claim

that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

is violated by certain specific features of the formula by

which the Commonwealth of Virginia apportions its educa

tional resources between Appellants, on the one hand, and

public school children in more affluent urban and suburban

counties.

The District Court agreed that Bath County is a poor

county, and that its poverty is related to the “ defi

ciencies and differences” which characterize its educa

tional system. And the court commended the County

and its people for straining their own financial re

sources to the legal and practical maximum. (J. S.

4a) But the court concluded that because school dis

tricts in Virginia receive state funds “ under a uniform

and consistent plan,” there was no violation of the

7

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. {Ibid.)

In this respect, the court was in error. Bath County,

located in the southwestern portion of the state, is in

deed a poor county.2 As the record shows, nearly half

of the County’s families have an income of under

$3000. (Tr. 27) Principal occupations are serving

as domestics at The Homestead resort and working as

laborers in the County’s forests. The County has no

public library, no theatres, no public tennis courts or

golf courses, and no public swimming pools. (Tr. 70)

The County now taxes itself at the maximum level

permitted by state law, and this year will spend 93

percent of its total tax revenues on its school system.

(Tr. 104)

As a result of the interplay of the County’s poverty

and the way in which otherwise uniform and consistent

state laws operate, Appellants are denied equal oppor

tunities as compared to those afforded public school

children in more affluent urban and suburban parts of

the Commonwealth.

This brief will focus on several key discriminations

resulting from the interplay of poverty and state law.

1. Salary Assistance: Because of its geographical

location and its poverty, Bath County is unable to re

cruit a full staff of accredited teachers. In average

teacher’s salary, the County ranks 113th of 127 in V ir

ginia. (Tr. 30) In percentage of teachers with ad

vanced degrees, the County places 119th.

Instead of compensating for these inadequacies, V ir

ginia law visits harsh financial penalties upon the

2 An "Appalachian County” for purposes of the Appalachian Regional De

velopment Act of 1965, P.L. 89-4, 79 Stat. 5, 49 U.S.C. — , App. § 1 et seq.

See Tr. 21.

8

County because of them. The Commonwealth has legis

lated a state salary supplement in the amount of 60 per

cent of teachers’ salaries—the principal form of state

financial aid to public education. But state assistance

is adjusted downward in relationship to the number of

unaccredited teachers and to the extent that the number

of students per class drops below 30 in elementary

school and 23 in high school. 1968 Acts of Assembly,

Ch. 806, Item 564. These penalty provisions presum

ably have the otherwise laudatory purpose of providing

incentives for school districts to hire only accredited

teachers and to use their resources efficiently.

But in the circumstances in Bath County, the incen

tive system not only breaks down, but works in reverse.

Sixteen of the County’s 53 teachers are unaccredited

and therefore ineligible to receive any form of state

salary supplement. (Tr. 15-16) And the County can

not aggregate the necessary number of students per

classroom; the County is sparsely settled and carved

up by beautiful but inconveniently placed mountains.3

(Tr. 14-16) As a result, the state salary assistance

program strips Bath County of desperately needed

state funds—which are paid to more affluent school

districts.

Other forms of salary assistance are likewise denied

Bath County, but granted less needy school districts.

Virginia, for example, provides a 60 percent supple

ment to salaries of principals (item 560), other super

visory personnel (item 557) and vocational training

and other special teachers (item 558). But Bath

County cannot afford principals or assistant principals

in its elementary schools, and has no supervisors of

8 The topography makes consolidation of school districts or schools not

feasible.

9

instruction, vocational training teachers, or visiting

specialists. (Tr. 15, 73-74) Nor is the County able

to earn its share of state matching grants for voca

tional training equipment. (Tr. 73-74, 113) It is

simply not affluent enough to gain access to state aid.

No one would suggest that Virginia could per

missibly provide mortgage assistance to all homeown

ers, provided they live in $40,000 homes. The state

supplement program is precisely analogous, and it is

equally unconstitutional as applied to Bath County.

2. Curriculum Deficiencies: As a consequence of its

own poverty and the partial denial to it of state

salary and other assistance, the County is unable to

offer a currieulmn which will help break the cycle of

poverty. Because of the lack of funds and the ex

pensive nature of this kind of education, Bath County

is unable to offer technical vocational training. (Tr. 74)

Nor is it able to provide a curriculum which has a

sufficient range of courses to entitle graduates of the

County’s schools to enter such state institutions of

higher learning as William and Mary College (Tr.

79) .4 A great many institutions,5 moreover, require ap

plicants to come from accredited high schools, and the

Bath County schools are unaccredited. See Proceed

ings of 72d Annual Meeting of the Southern Associa

tion of Colleges and Schools, Dallas, Texas, November

1967. As a result, students drop out in large numbers

to take such dead-end jobs as caddying at The Home

stead. (Tr. 78)

4 Bath County schools offer but 39.5 units compared to the statewide

average o f over 62, and a figure for Fairfax County of 137. (Tr. 30-31)

5 We are advised, however, that Virginia’s own state institutions accept

accreditation by the Commonwealth itself, which Bath County schools have

been given.

io

It was conceded below that it is not witbin the power

of the County, unaided, to correct these curriculum

deficiencies. We contend that so long as Virginia

maintains institutions of higher learning open to high

school graduates who have taken the required courses,

it must insure that schools in each and every county

offer at least the curriculum necessary to meet the

entrance requirements set by such state institutions.

See Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ; Sweatt v.

Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ; Sipuel v. Board of Re

gents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948); Missouri ex rel. Gaines

v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938). As this Court said

in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 493

(1954), “ [WJhere the State has undertaken to pro

vide [public education, it] is a right which must be

made available to all on equal terms.”

3. School Plant: Bath County, as a result of its

proverty, is forced to use a substantial number of ed

ucational facilities which the Commonwealth’s own

experts have ruled “ substandard” . These include

school cafeterias with earthen floors! Since adequate

school plant is one of the criteria which determine

a school system’s accreditation,6 the deficiencies in Bath

County’s school plant may be a factor in rendering

its graduates ineligible for admission to some insti

tutions of higher learning. Affluent counties, able

to raise funds for school construction, receive some

state assistance with respect to interest costs. (Tr.

147) But the Commonwealth provides no funds for

construction of local school facilities—even to elimi

nate concededly “ substandard” facilities. Here again,

state law aids the rich while declining to aid the poor.

* * *

e United States Office of Education, Approval and Accreditation of Public

Schools, p. 15 (1960).

11

Certainly it cannot be said that the Court below sub

jected these discriminatory effects to the “ careful ex

amination . . . warranted where lines are drawn on

the basis of wealth. . . McDonald v. Board of

Election, 394 U.S. 802 (1969); Harper v. Virginia

State Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663, 670 (1966) ;

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963).

Each of the aforementioned evils is susceptible of

remedy by a simple, easily enforceable court order.

(1) The District Court should suspend application

to Bath County and similarly situated counties of the

penalty provisions whose effect is to deprive the County

of its share of state salary assistance. The Common

wealth should be required to provide 60 percent of

teachers’ salaries here, just as it does in Fairfax and

in other affluent counties, without regard to the num

ber of unaccredited teachers or to deviations in class

size. These are concededly circumstances not within

the County’s control, and may not be made the basis

for penalizing the County financially. (2) Similarly,

Virginia should be required to do whatever is nec

essary, providing special funds or visiting faculty, in

order to enable the County to offer a curriculum

which will at least make its high school graduates

eligible to meet the entrance requirements set by

William and Mary College, and like state institutions.

(3) Finally, it should be required to provide the

funds necessary to correct conceded deficiencies in

Bath County’s physical facilities, at least to the ex

tent these affect the system’s accreditation.

12

II. The District Court erred in concluding that the decision

in Mclnnis and its summary affirmance by this Court insulate

from judicial scrutiny the statutory formula challenged here.

One of the most distressing circumstances to those

working to improve the quantity and quality of Ameri

can education is the way in which Mclnnis and its

summary affirmance by this Court have been held to

shut the door to efforts to challenge state formulae

for apportioning educational resources. The present

case is but one example of the unnecessarily chilling

effect of Mclnnis.’’

Although we did join as amici to urge this Court to

note probable jurisdiction in Mclnnis, it is not nec

essary for us now to quarrel with the decision reached

there. Mclnnis is easily distinguishable from the

present case, despite the reluctance of lower courts to

observe the distinctions.

1. Mclnnis was a decision on a bare complaint, sup

plemented only by legal memoranda; no factual ma

terials were adduced. In the present case, on the other

hand, a full set of facts was put into the record, in

cluding abundant documentation, live testimony and

factual concessions by the Commonwealth.

2. In Mclnnis, the court rejected what it deemed

the “ nebulous concept” under which plaintiffs there

sought to require allocation of state funds solely on

the basis of the “ educational needs” of students. The

1 1n addition to the present case, see Serrano v. Priest, No. 938254, Calif.

Super. Ct. (L.A. Co. 1969), dismissed on the basis o f the lower court decision

in Mclnnis. Moreover, eases in other jurisdictions, at least in part, are not

being filed or pressed for fear Mclnnis will lead to their quick dismissal. See,

e.g., Board o f Educ. o f City o f Detroit, Mich. v. Michigan, No. 103342, Circuit

Ct. for Wayne County, Mich.; Rodriquez v. San Antonio Independent School

District, No. 68-175 S.A. (W.D. Tex.) ; Bellow v. Wisconsin, No. — —, Dane

County Cir. Ct., Wis.

13

District Court concluded that it lacked the means to

ascertain what those needs were, and the ability to

fashion a decree to implement such a standard. In

the present case, on the other hand, Appellants ask

only that they not he penalized because of the poverty

of the County. Bath County should receive only the

same state salary assistance that more affluent coun

ties receive—without regard to penalties triggered by

the County’s poverty. The Commonwealth should in

sure that Bath County is able to offer a curriculum

which at least equips graduates to apply for admission

to William and Mary College and like state institu

tions, and that the County’s physical facilities are

raised to levels which the Commonwealth’s own in

spectors will concede to be not “ substandard.”

3. In Mclnnis, the District Court emphasized that

Illinois guaranteed that each school district would ex

pend at least $400 per pupil, and that the legislature

periodically raised the floor. Virginia guarantees no

such mininram expenditure per pupil.8 And its legis

lature, as the record here demonstrates, has stead

fastly rejected recommendations by distinguished com

missions that it do more for poor school districts.8

5. The Mclnnis court observed that under the Illi

nois statutory scheme, each school system has an op

portunity to choose what portion of local revenues

are to be devoted to education as opposed to other

public needs. It held this decision “ reasonable, es

pecially since the common school fund assures a mini

mum of $400 per student.” 293 F. Supp., at 333.

* This statement must be qualified. In the unlikely event that the Com

monwealth’s contribution of 60 percent of salaries yields less than $110 per

pupil, that amount will be furnished in lieu of teacher aid. 9

9 See, e-g., the Turner Commission Report of 1967.

u

Here, not only does tlie Commonwealth, provide Bath

Connty with no such $400 floor, hut the County will

this year spend 93 percent of all local revenues on

education, is already taxing itself at the maximum

level permitted by state law, and therefore does not

have the luxury of choosing between education and

other public needs. Even the County’s single-minded

concentration on education leaves it woefully short of

educational funds.

In sum, Mclnnis and the present case are wTorlds

apart. Here Appellants proceed on an entirely differ

ent theory, focusing on equal educational opportuni

ties and facilities rather than arguably difficut-to-define

student educational needs. Here, the interplay of V ir

ginia’s statutory formula and Bath County’s poverty

is well documented, and indeed is conceded.

We do not, of course, know why this Court declined

to review Mclnnis. It may have balked at the lack

of a factual record. It may have been troubled by

the request that it relate state educational expenditures

to the “ educational needs” of students. It may have

been influenced by the $400 per pupil floor guaranteed

by the state legislature to all school districts. Or it

may have been persuaded that the Illinois legislature

was facing up to the State’s educational needs.

Whatever the reasons, none of them applies to the

present ease, and the Court below was in error in

following Mclnnis.10 We believe that it is vital that

this Court now make clear that Mclnnis was not in

tended to shut the door to judicial review of all for

mulae by which the states apportion funds among

school districts. Mclnnis has already had a substantial

10 Of course, even i f Mclnnis were squarely in point, this Court would not

be precluded by its summary affirmance in that case from setting this one

for plenary review. See The Sunday Law Cases, 366 U.S. 420, 511 (1961).

chilling effect oil school litigation. The present case

is, we believe, a highly appropriate one for demonstrat

ing that the courts are open to measure state for

mulae for apportioning educational resources by the

standards of the Equal Protection Clause.

CONCLUSION

We believe the record in this case requires reversal

of the decision of the District Court and the entry of

appropriate relief. Should the Court not wish to un

dertake the latter step, we believe it would be a sub

stantial service to American education and especially

to the school children of rural counties like Bath,

were this Court simply to remand to the District Court

with instructions to fashion relief so as to prevent

the interplay of poverty and state law from violating

the Fourteenth Amendment rights of the children.

Respectfully submitted,

Of Counsel for:

R a m s e y Cl a r k

D a n ie l P. L evitt

1725 “ K ” Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20006

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

National Education Association

of the United States:

D avid R u bin

1201 Sixteenth Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Bights

Under Law, and The Urban Coalition:

J o h n W . D ouglas

G eorge N. L in dsay

1660 “ L ” Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20036