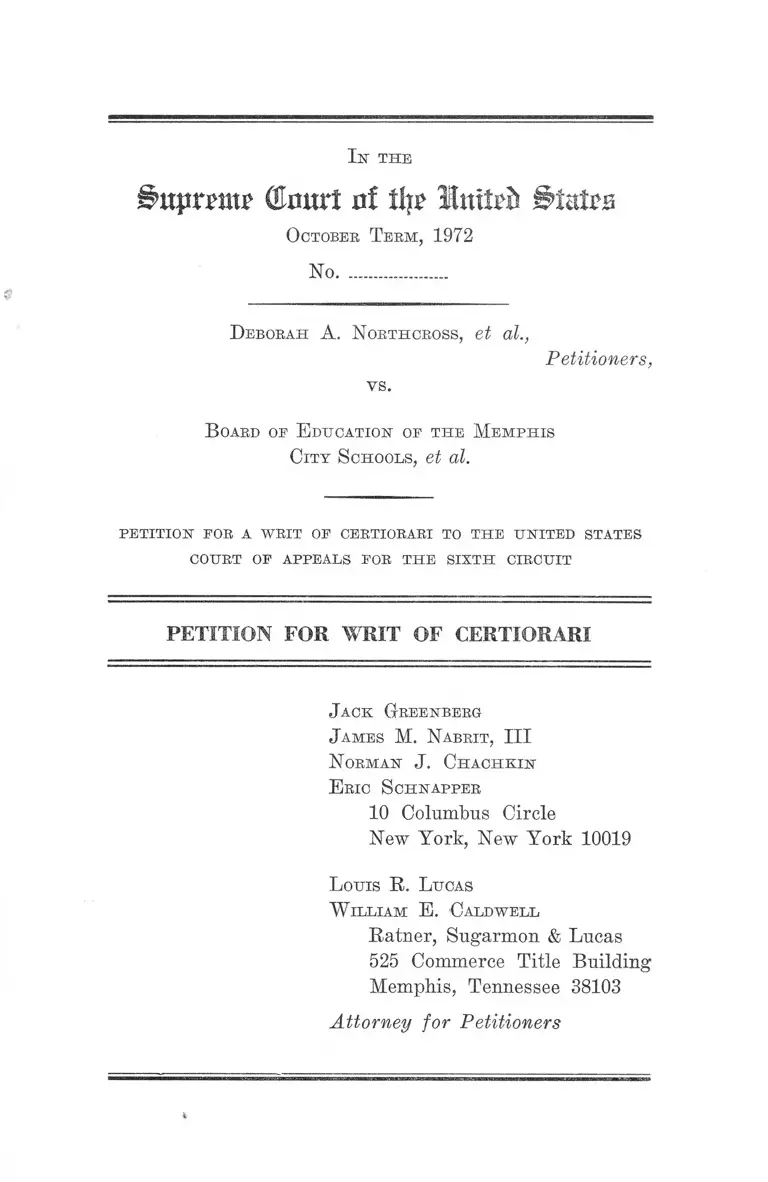

Northcross v. Memphis City Schools Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Northcross v. Memphis City Schools Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1972. 9c4db4d8-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f0d5d731-c345-484d-92a5-3dd72e2ee477/northcross-v-memphis-city-schools-board-of-education-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I k th e

(tort of % Imtrfc Stairs

O ctober T erm , 1972

No.....................

D eborah A. N orth cross, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

B oard of E ducation oe th e M em ph is

C it y S chools, et al.

petition for a w r it of certiorari to th e united states

court op appeals for th e sixth circuit

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

N orman J. C h a c h k in

E ric S chnapper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Louis R . L ucas

W illiam E . C aldw ell

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Attorney for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion B elow ......................_........................................ ...... 1

Jurisdiction ....... .................... ...... ............. ......................... 2

Question Presented ................................... 2

Statutory Provisions Involved ___________ ___ _____ _ 2

Statement of the Case ............. ......................... ............... 3

Reasons eor Granting the W rit ................................... 5

Conclusion ..................... 9

A ppendix............. la

Table op A uthorities

Cases:

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)....... 7, 8

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School

District, 449 F.2d 493 (8th Cir. 1971), 369 F.2d 661

(8th Cir. 1966) ..... ....... ..................... ............. ....... ....... 8

Cooper v. A llen ,------ F .2d ------- (5th Cir. 1972).......... . 8

Ford v. White, —— F. Supp.------ (S.D. Miss. 1972).... 8

Johnson v. Coombs,------F .2d ------- (5th Cir. 1972)..... 6

Knight v. Auciello,------F .2d ------- (1st Cir. 1972)....... 8

La Raza Unida v. V o lp e ,--------F. Supp. ------- (N.D.

Cal. 1972) 8

u

PAGE

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d 143 (5th

Cir. 1971) .......................................................................... 8

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375 (1970).— 8

N.A.A.C.P. v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703 (M.D. Ala. 1972) 8

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400

(1968) .................................. 6

Ross v. Goshi,------F. Supp.-------- (D. Hawaii 1972).... 8

Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala. 1972)____ 8

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 H.S. 1 (1971) .............................................. 3

Thompson v. School Board of Newport News, ------

F.2d ------ (4th Cir. 1972) ........ ...... ............... ............. 6

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham, 393 H.S.

268 (1969) .................................................................... 8

Wyatt v. Stickney, —— F. Supp. ------ (M.D. Ala.

1972) ............... 8

Other Authorities:

28 U.S.C. § 1254 ................................ 2

42 H.S.C. § 1983 .................................... .................... ......... 8

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure 39 ..................... 4, 8

Section 718, Emergency School Aid Act of 1972 .....2, 5, 6,

7,8

I k the

§>upmn? (fetrt of il}£ IHtuteh JitatTB

O ctober T erm , 1972

No.....................

D eborah A. N orth cross, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

B oard of E ducation of th e M em ph is

C ity S chools, et al.

petition for a w rit of certiorari to th e united states

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

The petitioners Deborah Northeross et al. respectfully

pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review the order

and judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit entered in this proceeding on November

24, 1972.

Opinion Below

The Court of Appeals issued no opinion in support of

its order of November 24, 1972. That order appears in

the Appendix hereto.

The Court of Appeals issued opinions at earlier stages

in this proceeding on June 7, 1971, which is reported at

2

444 F.2d 1179, and on August 29, 1972, which is reproduced

in the Appendix to the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

filed in No. 72-677. The District Court for the Western

District of Tennessee issued opinions at earlier stages in

this proceeding on May 1, 1970, reported at 312 F. Snpp.

1150, and on December 10, 1971 and April 20, 1972, both

reproduced in the Appendix to the Petition for a Writ of

Certiorari filed in No. 72-677.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit was entered on November 24, 1972. This petition

is filed within 90 days of that date. This Court’s juris

diction is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

Question Presented

Did the Court of Appeals err in denying plaintiffs costs

and attorneys fees?

Statutory Provisions Involved

Section 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972,

86 Stat. 235, provides:

S ec . 718. Upon the entry of a final order by a

court of the United States against a local educational

agency, a State (or any agency thereof) or the United

States (or any agency thereof), for failure to comply

with any provision of this title or for discrimination

on the basis of race, color, or national origin in viola

tion of title VI of the Civil Eights Act of 1964, or the

fourteenth amendment to the Constitution of the

United States as they pertain to elementary and sec

3

ondary education, the court, in its discretion, upon a

finding that the proceedings were necessary to bring

about compliance, may allow the prevailing party,

other than the United States, a reasonable attorney’s

fee as part of the costs.

Statement o f the Case

This case was commenced over a decade ago to desegre

gate the public schools of Memphis. The latest round of

litigation derives from the decision of the Sixth Circuit

Court of Appeals in 1971 directing the District Court to

reconsider the desegregation plans for the Memphis public

schools in the light of this Court’s decision in Swann v.

Charlotte-MecldenVurg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971).

In April, 1972, after extensive hearings, the District

Court ordered into effect a new desegregation plan to

eliminate the vestiges of the dual school system in Memphis.

Both plaintiffs and defendants appealed from the order of

the District Court. On August 29, 1972 the Sixth Circuit

ruled in favor of the plaintiffs on all questions, granting

plaintiffs’ request for an order directing the District Court

to prepare a timetable for further desegregation, and af

firming over defendants’ objections the District Court’s

order for the 1972-1973 school year. On February 20, 1973,

this Court denied the school board’s petition for a writ

of certiorari to review the decision of August 29, 1972.

Board of Education of Memphis City Schools v. North-

cross, No. 72-677.

Plaintiffs’ complaint, filed on March 31, 1960, expressly

sought costs as part of the relief prayed for. On Sep

tember 7, 1972, plaintiffs filed a timely Bill of Costs in

4

connection with the August 29 decision, pursuant to Fed

eral Rule of Appellate Procedure 39(c). On October 25,

1972, counsel for plaintiffs were first notified by the Clerk

of the Sixth Circuit that the court had directed that costs

not be taxed in favor of plaintiffs.1 On November 3, 1972,

plaintiffs petitioned the Sixth Circuit for rehearing, and

urged that the judgment and mandate of the court be

amended to award plaintiffs their costs, including a reason

able attorneys fee as part thereof.2 On November 24, 1972,

the Court of Appeals denied the petition for rehearing

and separately and expressly denied plaintiffs’ requests for

costs and attorneys fees.

1 The majority opinion of the panel issued August 29, 1972, con

tains no reference to the matter of costs. The words “no costs

allowed” appeared at the end of the dissenting opinion and were

not separately paragraphed. The transmittal letter of the Clerk

of the Sixth Circuit, dated August 29, 1972, contained no mention

of costs. The mandate of the Sixth Circuit, issued October 5, 1972,

was not furnished to counsel for the parties. On October 13, 1972,

plaintiffs’ counsel wrote to the clerk of the Sixth Circuit inquiring

as to the disposition with respect to costs. On October 25, 1972,

counsel for plaintiffs received a letter from the clerk stating that,

“at the direction of the court,” no costs had been taxed in the

mandate of October 5. Whether the clerk found this direction in

the August 29 opinion or received it at some later time was not

disclosed.

2 Because of the delay in notification the petition was accom

panied by a motion for leave to file petition out of time. Defendants

opposed the petition for rehearing on the merits thereof but did

not question its timeliness.

5

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

This is the first case to reach this Court arising under

section 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972.

Section 718 expressly authorizes the federal courts to

award a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of costs to the

prevailing party in school desegregation cases. The statute

provides:

Upon the entry of a final order by a court of the

United States against a local educational agency, a

State (or any agency thereof) or the United States

(or any agency thereof), for failure to comply with

any provision of this title or for discrimination on the

basis of race, color, or national origin in violation of

title VI of the Civil Eights Act of 1964, or the four

teenth amendment to the Constitution of the United

States as they pertain to elementary and secondary

education, the court, in its discretion, upon a finding

that the proceedings were necessary to bring about

compliance, may allow the prevailing* party, other than

the United States, a reasonable attorney’s fee as part

of the costs.

Section 718 became law on July 1, 1972.

In their petition for rehearing in the Court of Appeals

seeking costs including a reasonable attorney’s fee, peti

tioners explicitly called the court’s attention to section 718.

Petitioners urged that the section clearly applied to the

instant case, and that under the facts an award of legal

fees was mandatorju The Sixth Circuit denied both costs

and legal fees without opinion.

The decision reached by the Sixth Circuit in this case is

at odds with contemporaneous decisions handed down in

6

Section 718 cases by the Fourth and Fifth Circuit Courts

of Appeals. The opinions of those courts in Johnson v.

Coombs and Thompson v. School Board of Newport News

are reproduced in the Appendix hereto.

Both the Fourth and Fifth Circuits would require the

award of attorney’s fees for services rendered after the

effective date of the Act, regardless of when the action

involved was commenced. Johnson v. Coombs, p. 2a;

Thompson v. School Board of Newport News, p. 6a. In

this case substantial services were rendered after the

enactment of the statute on July 1, 1972; the appeal itself

was argued on July 16, 1972.

While section 718 states that the federal courts “may”

award attorney’s fees under the circumstances described,

the Fifth Circuit correctly construed the statute to re

quire the award of such fees in the absence of special cir

cumstances rendering such an award unjust. In Johnson

the court, noting the similarity of language and purpose

between section 718 and Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act, explicitly adopted this Court’s standard announced

in Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400

(1968), p. 9a. In the instant case the Sixth Circuit did

not find any circumstances rendering the award of attor

ney’s fees unjust, and none exist.

The result reached by the Sixth Circuit in this case is

entirely inconsistent with that reached by the Fifth Cir

cuit in Johnson under virtually identical circumstances.

Here, as in Johnson, legal fees were sought, inter alia, for

services rendered in prosecuting an appeal after the effec

tive date of the Act in an action commenced before that

date. Here, as in Johnson, there were no special circum

stances found, shown, or even argued which would have

made an award unjust. Here, as in Johnson, the plaintiffs

had succeeded in compelling the defendant school board

7

to abolish a de jure dual school system. Yet here, unlike

Johnson, attorneys’ fees were denied.

The Sixth Circuit’s failure to explain its denial of costs

and attorney’s fees obscures the exact nature of its dis

agreement with the interpretation of section 718 adopted

by the Fourth and Fifth Circuits. But the rule adopted

in this case, however unclear its rationale, is of course

binding upon the district courts in the Sixth Circuit. Con

flicts between the circuits regarding a plaintiff’s rights to

attorney’s fees in school desegregation cases should not be

countenanced merely because one of the appellate courts

involved declines to enunciate the basis of its decisions.

It is particularly important that this Court clarify the

meaning of section 718 because of its impact on private

parties seeking to enforce the commands of Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), and its progeny.

Since this Court’s decision in Brown, Negro school chil

dren and their parents have been responsible for the bulk

of the school desegregation litigation in the United States.

That litigation has often proved lengthy and complicated;

the instant plaintiffs have been pursuing this case in the

Federal courts for 13 years. Yet while the public officials

opposing them were able to draw upon tax dollars to fight

the integration of the public schools, private citizens have

all too often been forced to bear their own expenses. It was

to end this obvious injustice that Congress enacted section

718, and a writ of certiorari is necessary to assure that

Congress’ desires are not frustrated in the Sixth Circuit.

The result reached by the Sixth Circuit in this case is

inconsistent with a number of decisions in other circuits

awarding attorney’s fees to plaintiffs suing to enforce

important congressional or constitutional policies even in

the absence of an express statutory authorization of such

fees. Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d 143

8

(5th. Cir. 1971); Knight v. Auciello, ------ F.2d ------ (1st

Cir. 1972); N.A.A.C.P. v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703 (M.D.

Ala. 1972); Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala.

1972); Cooper v. Allen, ------ F.2d ------ (5th Cir. 1972);

Wyatt v. Stickney,------ F. Supp. -------- (M.D. Ala. 1972);

Ford v. White, —*—■ F. Supp. ------ (S.D. Miss. 1972);

La Rasa Unida v. Volpe, ------ F. Supp. ------ (N.D. Cal.

1972); Ross v. Goshi,------ F. Supp. —-— (D. Hawaii 1972).

Litigation such as this benefits all students, black and

white, and imposing plaintiff’s legal fees on the defendant

school board effectively transfers that expense to the entire

class benefiting from it. Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co.,

396 U.S. 375 (1970). After almost two decades of litiga

tion under Brown, full relief under 42 TJ.S.C. § 1983 re

quires that the victims of discrimination no longer be

forced to bear the constant and crushing burden of enforc

ing their constitutionally accorded rights. Clark v. Board

of Education of Little Rock School District, 449 F.2d 493

(8th Cir. 1971), 369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966). Petitioners

submit that the award of legal fees under section 718

should not be limited to fees for services rendered after

July 1, 1972, but should extend to all cases still pending

on that date. Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham,

393 U.S. 268 (1969). Certainly in a case such as this the

Court of Appeals was unjustified in denying to plaintiffs

as the prevailing party on appeal the costs authorized by

Rule 39, Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure.

9

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, a writ of certiorari should issue to

review the judgment and opinion of the Sixth Circuit.

J ack Gbeenbebg

J ames M. N abbit , III

N obm ax J . C h a c h k ik

E bic S chnappee

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Lotus E. L ucas

W illiam E. C aldwell

Eatner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Attorney for Petitioners

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX

Order

I n th e

U nited S tates C ourt of A ppeals

F or th e S ix t h C ircuit

(Filed November 24, 1972)

D eborah A. N qrthcross, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees-

Cross Appellants,

B oard of E ducation of th e M em ph is

C ity S chools, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants-

Cross Appellees.

Before:

W eick , Celebrezze and P eck ,

Circuit Judges.

Upon due consideration, Plaintiffs-Appellees and Cross-

Appellants’ motion to file petition for rehearing and sug

gestion for rehearing en banc out of time is hereby denied.

Plaintiffs-Appellees’ request for costs and attorneys’

fees is hereby denied.

So o r d e r e d .

E ntered b y Order o f th e C ourt

J ames A. H iggins

Clerk

2a

Appendix

I n th e

U nited S tates C ourt of A ppeals

F or th e F ourth C ircuit

Nos. 71-2032 and 71-2033

F r a n k V . T hom pson , et al.,

Appellants,

v.

S chool B oard of th e C ity of N ew port N ew s , et al.,

\ Appellees.

Nos. 71-1993 and 71-1994

M ichael Copeland, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

S chool B oard of th e C it y of P ortsm outh , et al.,

Appellees.

No. 72-1065

N ath an iel J am es, et al.,

Appellees,

v.

B eaufort C ou nty B oard of E ducation ,

Appellant.

(Decided November 29, 1972)

3a

Appendix

Before

H ayn sw o bth , Chief Judge,

W in ter , ■Craven , B urzn er , R ussell and F ield ,

Circuit Judges, sitting en banc.

P er Cu r ia m :

We ordered en banc consideration of lawyer fee claims

in these school cases to consider the extent of the ap

plicability of § 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act of

1972. In the City of Portsmouth and the Beaufort County

cases, however, apparently adequate fees are allowable on

other bases. The precise extent of the reach of § 718 in

those cases, therefore, now appears academic.

In the Newport News case, most of the legal services

are yet to be rendered, and we are unanimously of the

view that, if relief is granted, fees will be allowable under

§ 718 for those future services. The division within the

Court as to the application of § 718 will have some bearing

upon any ultimate allowance of fees in that case, though

less than was supposed when reargument was requested.

The Court is unanimously of the view that it should

apply § 718 to any case pending before it after the Sec

tion’s enactment. This is consistent with the principle of

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 103,

most recently enunciated in the Supreme Court in Thorpe

vi Housing Authority of Durham, 393 U.S. 268.

A majority of the Court, however, is of the view that

only legal services rendered after the effective date of

§ 718 are compensable under it. Those members of the

Court invoke the principle that legislation is not to be

given retrospective effect to prior events unless Congress

has clearly indicated an intention to have the statute ap

plied in that manner. They do not find such an intention

4a

from the omission of a provision in an earlier draft ex

pressly limiting its application to services rendered after

its enactment, when the earlier draft was extensively re

vised and there is no affirmative expression by any member

of Congress of an intention that it should be applied to

services rendered prior to its enactment.

A minority of the Court would apply § 718 to legal

services, whenever rendered, in connection with school liti

gation culminating in an order entered after June 30,

1972. In their view, someone must pay the fee, and a

statutory placement of the burden of payment on school

boards is not a retroactive application of the statute, though

some of the services may have been rendered before its

enactment as long as an order awarding relief, the fruit of

the services, is entered afterwards.

The cases will be remanded for such further proceedings

in the District Court as may be necessary in accordance

with the views of the majority, applying § 718, when it

may otherwise be applicable, only to services rendered

after June 30, 1972.*

In the Portsmouth case, the District Court will award

reasonable attorneys’ fees on the principle of Brewer v.

The School Board of the City of Norfolk, 4 Cir., 456 F.2d

943 (1972). In the Beaufort County case, the award here

tofore made by the District Court is approved.

Remanded.

Appendix

'* In the Newport News case, on a completely different basis, the

District Court made an award of attorneys’ fees of $750.00 in

connection with services and events occurring before June 30, 1972.

Since that award was not dependent upon § 718, nothing we say

here should be construed to disturb it.

5a

W in ter , Circuit Judge, con cu rr in g sp ec ia lly :

I concur in the judgment of the court to the extent that it

directs the allowance of attorneys fees in the City of

Portsmouth, Beaufort County and Newport News cases.

For the reasons set forth in my separate opinion in Bradley

v. School Board of Richmond, — — F .2d ------ (4 Cir., No.

71-1774, decided ), I would direct the

allowance in all three cases on the basis that § 718 of the

Emergency School Aid Act of 1972 applies to leg*al services

rendered before the effective date of that enactment in

cases pending* on that date.

Appendix

6a

Appendix

I n t h e

U nited S tates C ourt of A ppeals

F or th e F if t h Circuit

No. 72-3030

P rincess E anola J ohn son , E tc ., et al .,

Plaintiffs- Appellees,

versus

M. B row n ing C ombs, Superintendent,

Grand Prairie Independent School District, et a l .,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas

(December 6, 1972)

Before T hornberry , M organ and Clark ,

Circuit Judges.

Clark , Circuit Judge: On the merits, the judgment ap

pealed from is due to be affirmed. Weaver v. Board of

Public Education of Brevard County, Florida, ------ F.2d

—— • (5th Cir. 1972) [No. 71-3465, September 6, 1972],

The collateral question as to plaintiffs’ entitlement to

attorneys’ fees below and on this appeal raises a novel

issue. The law of the circuit prior to the passage of Sec

7a

tion 718 of the Education Amendments Act of 19721 made

it clear that in school desegregation cases attorneys’ fees

would be awarded only if the school board was found to

have acted in an “unreasonable and obdurately obstinate”

manner. See Williams v. Kimbrough, 415 F.2d 874 (5th

Cir. 1969), cert, denied 396 IT.S. 1061, 90 S.Ct. 753, 24

L.Ed.2d 755 (1970) [citing Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14

(8th Cir. 1965)], and Horton v. Lawrence County Board

of Education, 449 F.2d 793 (5th Cir. 1971). The same rule

has been applied in actions under 42 U.S.C.A. § 1982 (which,

like Williams and Horton, were not governed by a statutory

provision for attorneys’ fees), Lee v. Southern Homesites

Corporation, 429 F.2d 290 (5th Cir. 1969).

However, the enactment of Section 718 of the Education

Amendments Act of 1972 requires that we answer three

questions on this appeal: first, does the statute merely

codify the existing “unreasonable and obdurately obstinate”

standard, or does it set new parameters within which the

district court must exercise its discretion; second, if the

statute does create a new legal standard, to what degree

should that standard be applied retroactively; and third,

when is an order a “final order” within the meaning of the

statute ?

Appendix

1 Upon the entry of a final order by a court of the United States

against a local educational agency, a State (or any agency thereof),

or the United States (or any agency thereof), for failure to comply

with any provision of this title or for discrimination on the basis

of race, color, or national origin in violation of title VI of the

Civil Eights Act of 1964, or the fourteenth amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States as they pertain to elementary and

secondary education, the court, in its discretion, upon a finding

that the proceedings were necessary to bring about compliance,

may allow the prevailing party, other than the United States, a

reasonable attorneys’ fee as part of the costs.

8a

We note at the outset that Section 718 is similar, though

not identical,2 3 * * * * to the provision allowing attorneys’ fees to

the successful party in an action based on Title II of the

1964 Civil Rights Act.8 In the leading case interpreting

that provision, Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc.,

390 U.S. 400, 401 88 S.Ct. 964, 966, 19 L.Ed.2d 1263 (1968),

the Supreme Court held that attorneys’ fees must be

awarded “unless special circumstances would render such

an award unjust.” Rejecting “good faith” as a defense,

the Court reasoned that,

If Congress’ objective had been to authorize the

assessment of attorneys’ fees against defendants who

make completely groundless contentions for purposes

of delay, no new statutory provision would have been

necessary, for it has long been held that a federal

court may award counsel fees to a successful plaintiff

where a defense has been maintained “ in bad faith,

vexatiously, wantonly, or for oppressive reasons.” 6

Moore’s Federal Practice, 1352 (1966 ed.).

390 U.S. at 403 n. 4, 88 S.Ct. at 966 n. 4.

Newman has been applied by this Court in Miller v.

Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534 (5th Cir.

1970), where we concluded in another Title II action that

neither the fact that a non-frivolous controversy existed

nor the fact that the defendants acted in good faith con-

Appendix

2 Section 718 requires a threshold finding by the trial court that

the proceedings were necessary to enforce compliance.

3 In any action commenced pursuant to this subehapter, the court,

in its discretion, may allow the prevailing party, other than the

United States, a reasonable attorneys’ fee as part of the costs, and

the United States shall be liable for costs the same as a private

person, 42 U.S.C. § 2000a-3(b).

9a

stituted the “ special circumstances” contemplated by the

Supreme Court. Thus, the standard ajjplied under the

statutory language in Title II actions diverged somewhat

from the standard applied in school desegregation cases

by this Court and other Circuit Courts which have con

sidered the question. See Brewer v. School Board of City

of Norfolk, Virginia, 456 F.2d 943, 949 (4th Cir.), cert.

denied ------ U.S. ------ , 92 S.Ct. 1778, ------ - L.Ed.2d ------

(1972). That Congress chose to structure Section 718 in

language similar to that interpreted by the Supreme Court

in Neivman is a strong factor indicating that the two

statutes should be interpreted pari passu.

Moreover, in addition to the similarity of the language

used in Section 718 and its Title II analogue, the two pro

visions share a common raison d’etre. The plaintiffs in

school cases are “private attorneys general” vindicating

national policy in the same sense as are plaintiffs in Title

II actions. The enactment of both provisions was for the

same purpose— “to encourage individuals injured by racial

discrimination to seek judicial relief . . .” See Newman,

supra, 390 TJ.S. at 402, 88 S.Ct. at 966. We hold that if the

court finds that the proceedings were necessary to bring

about compliance, then Section 718 must be applied in

accordance with the test enunciated in Newman, i.e., in

the absence of special circumstances attorneys’ fees are

to be awarded.

We decline to apply § 718 retroactively to the expenses

incurred during the years of litigation prior to its enact

ment. This interpretation of the neutral language of the

statute is compelled both by the long-established presump

tion against retrospective application in the absence of a

clear legislative intent and the clear precedents of this

Circuit governing such litigation. School desegregation

Appendix

Appendix

litigation has produced precedents which have been some

what less than clear and explicit. Even when plaintiff and

defendant were in agreement about the end to be reached,

the means and the timing which would accomplish the goal

often remained in bitter dispute. There was a necessity

that the demands of the aggrieved plaintiffs be harmonized

with legitimate educational interests of the school authori

ties and the community as a whole in the smooth and un

eventful transition to a unitary school system. Many

school districts have been litigating in this field filled with

fast changing precedents and guidelines for a number of

years; to apply this statute retroactively would place a

wholly unexpected and unwarranted burden on these dis

tricts who have done no more than litigate what they, in

good faith, believed to be demands which exceeded the

Constitution’s demand.4

Under these circumstances, a retroactive application of

this statute would punish school boards for good faith ac

tion in seeking the guidance of the courts to determine

what was required of them. Furthermore, retroactive

awards of attorneys’ fees for these past years of litiga

tion would not serve the purpose of encouraging future

legal challenges of segregated school systems. The incon

clusive legislative history of Section 718 furnishes no

basis for inferring that Congress intended this provision

to be given such a sweeping effect.

Thus, as to legal services awarded prior to July 1, 1972,

the effective date of the Education Amendments Act of

1972, we hold that the award of attorneys’ fees is to be

4 Of course if the litigation could be characterized as unreason

able and obdurately obstinate, then by the same reasoning as ad

vanced in Newman, supra, Section 718 would be surplusage under

the existing rule of Williams and Morton.

11a

Appendix

governed by the standard enunciated by this court in Wil-

liams and Horton. Awards for legal services rendered on

or after that date are governed by the statute.

The brief order of the trial court indicates that the single

standard applied there was the one set out in Bradley v.

School Board of City of Richmond, Virginia, 53 F.R.D.

28 (E.D. Va. 1971). Without deciding whether the stan

dard enunciated in Bradley is consistent with Section 718,

we rule that Bradley, at least insofar as it holds that full

and appropriate relief in school desegregation cases must

include the award of expenses of litigation, 53 F.R.D. at

41, is inconsistent with the standard of this circuit ap

plicable to legal services rendered prior to the effective

date of the statute. Since the record indicates that some

part of the legal services in this case may have been ren

dered prior to that date, we vacate the award of attorneys’

fees and remand to the district court for further proceed

ings in accord herewith.

Section 718 expressly allows attorneys’ fee awards only

upon “the entry of a final order.” The most suitable test

for such finality exists in the body of law which has been

developed in determining appealability under 28 U.S.C.A.

§ 1291. In general, this means a judgment or order which

ends the litigation on the merits and comprehends only

the execution of the court’s decree. See C. Wright, Federal

Courts § 101 (2d ed. 1970). Since most school cases in

volve relief of an injunctive nature which must prove its

efficacy over a period of time, it is obvious that many sig

nificant and appealable decrees will occur in the course of

litigation which should not qualify as final in the sense

of determining the issues in controversy. The ultimate

approach to finality must be an individual and pragmatic

one. Such a matter should be committed to the deter

mination of the trial court.

12a

For the district court’s guidance at the appropriate time,

we now hold that plaintiffs are entitled to a reasonable at

torneys’ fee for prosecuting this present appeal, in the

amount of 1,250 dollars. See Meeks v. State Farm Mut.

Ins. C o.,------ F. 2d —— (5th Cir. 1972) [No. 71-2137, No.

2293, May 22, 1972]; Campbell v. Green, 112 F.2d 143 (5th

Cir. 1940).

Appendix

A eeibmed in part,

V acated in p art and

R emanded.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219