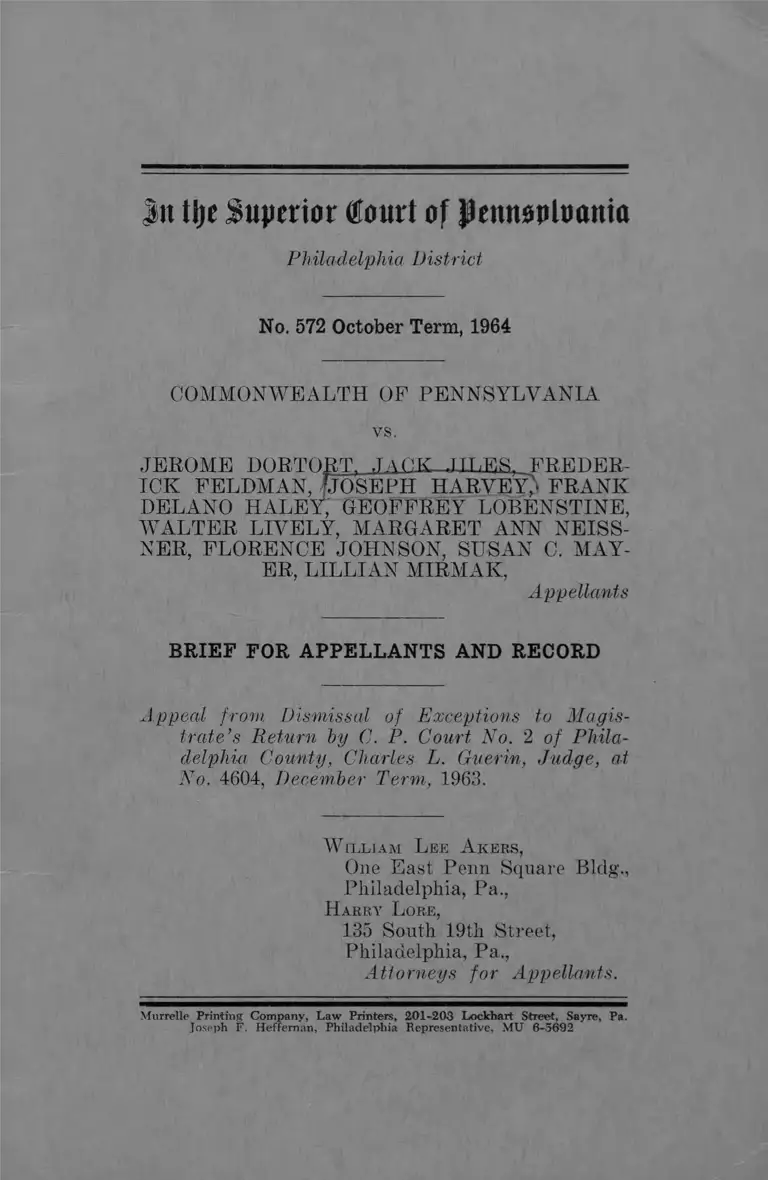

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Dortort Brief for Appellants and Record

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Dortort Brief for Appellants and Record, 1964. 9ab682fb-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f0f0babb-927c-455c-a4f6-ccba96b43f3b/commonwealth-of-pennsylvania-v-dortort-brief-for-appellants-and-record. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

J it tlje Superior dTourt of Pennoploonia

Philadelphia District

No. 572 October Term, 1964

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA

vs.

JEROME DORTORT. .) \('K, J.LLFS. FREDER-

ICK FELDMAN, ClOSEPH HARVEY> FRANK

DELANO HALEY, GEOFFREY LOBENSTINE,

WALTER LIVELY, MARGARET ANN NEISS-

NER, FLORENCE JOHNSON, SUSAN C. MAY

ER, LILLIAN MIRMAK,

Appellants

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS AND RECORD

Appeal from Dismissal of Exceptions to Magis

trate’s Return by C. P. Court No. 2 of Phila

delphia County, Charles L. Guerin, Judge, at

No. 4604, December Term, 1963.

W illiam L ee A kers ,

One East Penn Square Bldg.,

Philadelphia, Pa.,

H arry L ore,

135 South 19th Street,

Philadelphia, Pa.,

Attorneys for Appellants.

Murrelle Printing Company, Law Printers, 201-203 Lockhart Street, Sayre, Pa.

Joseph F. Heffeman, Philadelphia Representative, MU 6-5692

INDEX TO BRIEF

P age

Statement of Questions Involved ................... 1

History of the Case ........................................ 2

Argument:

1. A Criminal Conviction for a Civil Of

fense Violates Due Process ................... 5

2. The Conviction, Being Without Evidence,

Violates Due Process, and This Consti

tutional Deprivation May Be Raised on

Certiorari .................................................. 10

3. The Magistrates’ Courts of Philadelphia

Are Constitutionally Limited in Their

Jurisdiction to Hearing Cases Involving

City Ordinances Under Which the Penal

ty Sought Is One Hundred Dollars or

Less ......................................................... 15

4. The Petitioners’ Previous Acquittal

Bars Their Second Conviction for the

Same Act ................................................ 21

Conclusion ....................................................... 26

TABLE OF CITATIONS

C ases :

Bartkus v. Illinois, 359 U.S. 121, 151 ............. 25

Brown v. Hummel, 6 Pa. 86, 97 ................. 9,29

Byers v. Olander, 161 Pa. Sup. 165 ............. 19

City of New Castle v. Genbinger, 37 Pa. Sup.

'21 ................................................................. 13

l

Commonwealth v. Ashenfelder, 413 Pa. 517 .. 6, 28

Commonwealth v. Ayers, 17 Pa. Sup. 352, 358 13

Commonwealth v. Barbono, 56 Pa. Sup. 637 13

Commonwealth v. Beatty, 91 Pa. Sup. 37 . . . . 24

Commonwealth v. Bergen, 134 Pa. Sup. 62 . . 24

Commonwealth v. Bishop, 182 Pa. Sup. 151 . . 23

Commonwealth v. Cannon, 32 Pa. Sup. 78 . . 13

Commonwealth v. Comber, 374 Pa. 51 ......... 23

Commonwealth v. Conn, 183 Pa. Sup. 144 . . . . 14

Commonwealth v. Divoskein, 49 Pa. Sup. 614 13

Commonwealth v. Goldberg, 31 D. & C. 2d 373,

375 ................................................................ 14

Commonwealth v. Greene, 410 Pa. I l l ........ 6

Commonwealth v. Nesbit, 34 Pa. 398 ......... 12

Commonwealth v. Palms, 141 Pa. Sup. 430,

438 ............................................................... 14

Commonwealth v. Strada, 171 Pa. Sup. 358 . . 8

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 ......... . 10

Gieseu v. Conrad, 85 D. & C. 219 . ... . . . . . . . 7

Huber v. Redly, 53 Pa. 112, 117 ......... ........... 8

Marsteller v. Marsteller, 132 Pa, 517 .......... 24

Rex v. Vipont et ah, 2 Burrows 1163, 1165 . . 12

Rutenberg v. Philadelphia, 329 Pa, 26 ........ 21

Tappan v. Sementino, 13 D. & C. 2d 108 . . .b 7

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 10

United States v. Chorteau, 102 U.S. 612 . . . . 25

United States v. Gates, Fed. Cas. No. 15, 191 25

United States v. Glidden Co., 78 F. 2d 639 .. 25

id

25United States v. Jim, 48 F. 2d 593 .................

United States v. LaFranca, 282 U.S. 568 . . . .

United States v. McKee, Fed. Gas. No. 15,

688 ...............................................................

United States v. Seattle Brewing Co., 135 F.

597 ...............................................................

United States v. Ulrica, 102 U.S. 612 .........

C on stitu tio n s :

Constitution of Pennsylvania:

Article 5, Sec. 10 .................................. 3,

Article 5, Sec. 12 ................. 16,17,19, 20,

Article 1, Sec. 9 ....................................

Constitution of the United States, Fourteenth

Amendment ............................................... 7,

S t a t u t e s :

Act of April 17, 1876, P. L. 29, §1, as amend

ed, 19 P.S. 1189 ........................................

Act of March 15, 1858, P. L. 114, §1, 53 P.S.

17082 ...........................................................

Act of April 15, 1835, P. L. 291, §7, 42 P.S.

291 ...............................................................17,

Act of December 9, 1955, P. L. 817, §1, 42 P.S.

241 ...............................................................20,

Act of May 9, 1949, P. L. 1028, §14, 42 P.S.

1144 .............................................................

Act of March 31, 1810, P. L. 427, §30, 19 P.S.

464 ...............................................................

Act of September 18, 1961, P. L. 1464, 19 P.S.

12.1 ...............................................................

Ord inances :

Philadelphia Code of General Ordinances,

Clip. 10, 500 ................................................

iii

25

25

25

25

12

21

i

22

6

20

21

24

24

5

6

M iscellaneous :

Anno. 80 ALE 2d 1362,; 1367 ; ., .................... 10

Francis Bacon, Essays Civil and Moral . . . . 11

31 Am. Jur., Justices of the Peace, §57 . . . . 16

1 Sutherland, Statutory Construction, §2025 18

12 C.J., Constitutional Law, §97, p. 260 ....19 ,20

Burke’s Politics; Selected Writings and

Speeches ..................................................... 27

Herbert Spencer, Social Statistics ............. 27

INDEX TO RECORD

I. Relevant Docket Entries ....................... la

II. Magistrate’s Transcript ......................... 4a

III. Defendants’ Exceptions ......................... 10a

TV. Opinion sur Exceptions ......................... 12a

Order ......................................................... 18a

IV

Statement of Questions Involved

1

STATEMENT OF QUESTIONS INVOLVED

1. Does a criminal conviction for an act. which

gives rise to a civil action only, deprive the pe

titioners of the due process of law secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States!

(Answered in the negative by the Court below).

2. Where the petitioners are convicted of a crim

inal offense before the Magistrate, and his return

is devoid of any evidence or facts concerning the

offense charged, have the petitioners been deprived

of due process of law secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States!

(Answered, in the negative by the Court below).

3. Are the Magistrate Courts of the City of

Philadelphia limited in jurisdiction to hearing

cases involving city ordinances under which the

penalty sought is one hundred dollars or less!

(Answered in the negative by the Court below).

4. If a single act constitutes several offenses

and the Commonwealth elects to prosecute for some,

but not for all, is the Commonwealth thereafter

barred from obtaining new convictions for the re

maining offense!

(Ansivered in the negative, by the Court below).

2

History of the Case

HISTORY OF THE CASE

On September 20, 1963 the appellants herein were

arrested in Room 210 City Hall, Philadelphia by

police officers of the City of Philadelphia. They

were initially charged with disorderly conduct, and

breach of the peace. The gravamen of the offense

was their continued presence in the room after be

ing directed to leave by a police officer.

Appellants were then tried before Magistrate

William Hagan, who found them each guilty of

disorderly conduct and presumptively discharged

them as to breach of the peace. From those con

victions an appeal was taken under the Act of

April 17, 1876, P. L. 29, Sec. 1, as amended, 19

P S. Sec.- 1189. The appeal was allowed and a

trial de novo, was ordered by the Court of Quarter

Sessions.

The trial de novo was held on January 24, 1964

before the Honorable Charles L, Guerin. At the

outset, the District Attorney advised the Court that

the evidence would not sustain the conviction be

low, and the Court thereupon entered a verdict of

not guilty as to the appellants.

Thereafter, on January 31, 1964, upon an in

formation sworn by Frank Rizzo, a police officer,

criminal summonses were issued by Magistrate Wil

liam Hagan for each of the appellants.' The sum

History of the Case

3

monses were identical in form save the name of the

appellant. A copy of one such summons is in the

(Record, page 8a). The summons charged breach

of the peace and violation of City of Philadelphia

Ordinance 10-501(2) (h).

The appellants were again tried before Magis

trate William Hagan, on February 14, 1964, who

this time clearly discharged the appellants on the

offense of breach of the peace, without, however,

indicating whether he acted in response to the

plea by defendants of prior adjudication or on the

merits. He found the appellants guilty under the

ordinance and imposed a fine on each of fifty dol

lars or ten days in jail. Prior to this hearing, at

which appellants were adjudged guilty of violating

the ordinance, they sought to have the proceedings

before the Magistrate enjoined and removed to the

United States District Court for the Eastern Dis

trict of Pennsylvania. The Magistrate was named

as a party defendant and service was made by the

United States Marshal on February 4, 1964.

Thereafter, the appellants herein sought writs of

certiorari from the Common Pleas Court. Their

petition was granted upon a rule to show cause and

in due course the writ was issued by Court of Com

mon Pleas Number 2. The certiorari was issued

under the Constitutional power of the Court given

by Art, 5, Sec. 10 of the Constitution of Pennsyl

vania. Pursuant to the command of the writ, the

Magistrate filed his return and defendants prompt

ly filed exceptions thereto (Record, pages 10a,

4

History of the Case

11a). The exceptions were argued on May 22,

1964 before the Honorable Charles L. Guerin and

all were dismissed, the Court rendering an oral

opinion thereon (12a-18a).

The reference in the opinion to a writ of habeas

corpus is erroneous. No writ was ever sought, at

any time, by appellants and no writ of habeas cor

pus ever issued. The prior adjudication by Judge

Guerin was not guilty (2a).

Argument

o

ARGUMENT

1. A CRIMINAL CONVICTION FOR A CIVIL

OFFENSE VIOLATES DUE PROCESS

Appellants were brought before the Magistrate

by warrants issued under the Penal Code. Act

of Sept. 18, 1961, P. L. 1464, 19 P.S. 12.1. There

were two counts to the information. The first

count charged the defendants with breach of the

peace. The second count charged a violation of the

City ordinance.

The prosecution was commenced, tried, and ad

judged as a criminal proceeding. It was conduct

ed by the District Attorney, (At the argument on

the. exceptions lie was “ appointed” City Solicitor.)

The Magistrate was asked to hold the defendants

for the action of tlie grand jury on the charge of

breach of the peace and convict them summarily of

violating the ordinance. At the conclusion of the

trial,.the Magistrate announced he. was discharging

defendants as to. breach of the peace, and finding

them guilty of violating the ordinance. He pro

nounced sentence of 10 days in the County Prison

or a fine of $50.00 plus $2.50 costs, as to .each of the

appellants. The ordinance provides as follows:

6

Argument

“ No person shall: . . .

(h) use any city facility or enter into any

city property without authority. The penalty

for violation of any provision of this chapter

shall be a tine not less than $50.00 nor more

than $300.00 together with imprisonment not

exceeding 90 days if the fine and costs are not

paid within 10 days.” Philadelphia Code of

General Ordinances Chapter 10-500. Sections

10-501(2) (h) and 10-502.

Since the fine is at least $50.00 petitioners ar

gued that its enforcement and the proceedings there

under should be governed by the Act of March 15,

1858, P. L. 114, Sec. 1, 53 P.S. 17082. This act

provides as follows:

“ For all breaches of the ordinances of the

City of Philadelphia, where the penalty de

manded is fifty dollars and upwards, actions

of debt shall be brought in the corporate name

of the City of Philadelphia.”

No action of debt or assumpsit was brought

against the defendants by either the City or

the Commonwealth. Instead, the Commonwealth

brought a criminal prosecution commenced as an

indictable offense. The Supreme Court of Penn

sylvania has made it plain that violations of ordi

nances give rise to civil actions, Commonwealth v.

Ashenfelder, 413 Pa. 517, and has condemned the

use of criminal proceedings for such acts: Com

monwealth v. Greene, 410 Pa. 111.

The statute is plain on its face and its applica

tion to the ordinance is irresistible. Neither the

Argument

7

District Attorney nor the Court below suggested

any reason why it should not control this case.

Appellants contend it does. The statute conforms

to the principle that violations of ordinances give

rise to civil not criminal actions. The jurisdic

tion of the Magistrate to proceed criminally ex

tends only to those acts made criminal by our law.

Just as a Court of Common Pleas can not pro

ceed criminally on a complaint in assumpsit, the

Magistrate can not entertain a criminal prosecu

tion of a noncriminal matter. As a defect of form

it would be fatal. Tappan v. Sementino, 13 D. &

C. 2d 108. Here, it is one of substance, by which

the petitioners have been greatly harmed and preju

diced. The statute admits of no exceptions. If it

means anything, its words are mandatory. It pro

vides the sole and exclusive method of proceeding

on the subject ordinance. Without the required

action of debt, there has been no proceeding for

violating the ordinance under our law. The judg

ment of the Magistrate, having no legal founda

tion in an appropriate action is void, Giesen v.

Conrad, 85 D. & C. 219.

It is seldom that a mere error of state law of

fends the State and Federal Constitutions. How

ever, both the ninth section of the Bill of Rights

of the Constitution of this Commonwealth and the

first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States guarantee the

essential concepts of justice often described as due

process. ‘ ‘ Due process of law means a course of

legal proceedings according to those rules and prin

8

Argument

ciples which have been established for the protec

tion of private rights” , Commonwealth v. Strada,

171 Pa. Superior Ct. 358. “ It ordinarily implies

and includes a complaint, a defendant and a judge,

regular allegations, opportunity to answer and a

trial according to some settled course of judicial

proceeding.” Huber v. Reily, 53 Pa. 112, 117.

In this case the settled course of judicial pro

ceeding has been completely avoided. The appel

lants were entitled to the benefits of the civil law

and its rules. What rules govern a trial that is al

ternately criminal and civil? What rules of evi

dence prevail? Are the petitioners entitled to strict

construction of the offense and the charging paper

or is mere notice sufficient? May the appellants

file an affidavit of defense thereby preserving their

■defenses on the record? IIow may an action, 'which

vacilates, at the whim of the prosecutor, between

civil and criminal be defended"] Can a trial with

these uncertainties be due process? Can it be ac

cording to the law of the land? Indeed, Mr. Jus

tice Douglas spoke on this subject when he ad

dressed the American Law Institute in The May

flower Hotel in Washington, D.C., on May 20, 1953:

“ History show's that governments bent on a

crusade, or officials filled with ambitions have

usually been inclined to take short-cuts. The

cause being a noble one (for it always is), the

people being filled with alarm (for they usu

ally are), the government being motivated by

worthy aims (as it always professes), the de

mand for quick and easy justice mounts. These

Argument

9

short-cuts are not as flagrant perhaps as a

lynching, but the ends they produce are cumu

lative and if they continue unabated, they can

silently rewrite even the fundamental law of

the nation.”

The appellants were convicted. That word, with all

it implies, will follow them a:s an ever present cloud

forever.

The law of the Commonwealth required a civil

action. A criminal prosecution, in the teeth of our

law, shocks the conscience and cries out for relief.

Such a perversion of procedure probably would not

have been even attempted before a tribunal learned

in the law. By combining this illegitimate proce

dure and practice with the Magistrate’s Court, the

Commonwealth has effectively deprived appellants

of their rights under the law. The appellants’ right

to be served, to file answers, to preliminarily ob

ject, to have judgment on the pleadings, discovery

and, if the cause goes against them, a judgment of

debt rather than a conviction of crime have been

stripped away. Whatever rights they may have

been entitled to were rendered so uncertain of mode

of assertion that they were strangled by the gordi-

an knot below. Due process has been completely

avoided.

The court below has shifted the burden of secur

ing these rights to this Court. This burden has

been assumed in the past with alacrity. Brown v.

Hummel, 6 Pa. 86.

10

Argument

2: THE CONVICTION, BEING WITHOUT

EVIDENCE, VIOLATES DUE PROCESS

Exceptions Nos. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 (lOa-lla),

filed by the appellants to the Magistrate’s return,

were treated as one by the Court below. All these

exceptions treat of the fact that the Magistrate’s

return showed no evidence of any kind adduced at

the trial of appellants to support their conviction.

It is perfectly clear that a conviction without evi

dence of guilt violates federal due process. Thomp

son v. City of Lowisvitte, 362 U. S. 199, 80 S. Ct.

624, 4 L. Ed. 2d 654 (1960) ; Garner v. Louisiana,

368 U. S. 157, 82 S. Ct. 248, 7 L. Ed. 2d 207 (1961).

hi Thompson, the Supreme Court found no evi

dence in the record to support a conviction of dis

orderly conduct, and, accordingly held, 362 U. S.

at 206, 4 L. Ed. 2d at 659 :

“ Just as ‘ convictions upon a charge not made

would be sheer denial of due process’ so is it

a violation of due process to convict and pun

ish a man without evidence of his guilt.”

In the excellent annotation on Thompson in 80

A.L.R. 2d 1362 the simple truth is stated that (p.

1367):

“ Even a layman totally lacking in legal

sophistication could be expected to give a nega

tive and unhesitating answer to the question

whether the criminal law permits conviction of

Argument

11

crime when the prosecution introduces no evi

dence. . . . ”

Not only was the law ignored by the Court below,

but elemental justice should have dictated to' the

learned judge below that the conviction of appel

lants could not stand where there was not a scin

tilla of evidence to support it. “ Judges must be

ware of hard constructions and strained infer

ences” , wrote Sir Francis Bacon in 1597, “ for there

is no worse torture than the torture of laws.” 1

It is in such eases that misapplication of state

law offends the federal Constitution. Such is the

instant case.

The Court below refused to consider these excep

tions, which relate to the absence of evidence, and

grounded its refusal on the totally fallacious propo

sition, urged by the .District Attorney, that these

substantive defects in the proof had been waived

by taking certiorari to the Court of Common Pleas

instead of an appeal to the. Court of Quarter Ses

sions.2

1 Francis Bacon, Essays Civil and Moral (Cassell’s

National Library, 1891), p. 170.

- The Court below specifically stated as follows. (17a):

. “ All of these Exceptions [No. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and

12] relate to the merits of the controversy and are

not properly reviewable upon a Writ of Certiorari.

For error of : the nature complained of in these ex-

-ceptions, there is a remedy provided ... , by appeal

. ..to the Court of Quarter Sessions . . ...and the Court

of Quarter Sessions would then have jurisdiction to

hear the matter de novo and make its findings of

fact and of guilt or innocence.”

12

Argument

It is submitted that certiorari to the Magistrate

is the proper, appropriate and legal manner to

raise the defect of no evidence. Indeed, the Consti

tutional mandate in Art. 5, Sec. 10, is that the

judges of the Common Pleas Courts shall have the

power to issue writs of certiorari to inferior courts,

not of record, so that “ . . . right and justice . . . be

done.” It is difficult to imagine a grant of correc

tive power in a superior judicial tribunal broader

in its scope than that. How can right and justice

be done to the- appellants, if their convictions are

allowed to stand, where there is a. total void in the

evidence to support such conviction!

The law of the Commonwealth has been clear on

this point for three hundred years. In Rex v. Vi-

pont et al., 2 Burrows 1163, at 1165, the Court said:

‘ ‘ In a conviction the evidence must be set out.”

(The case was decided at Easter Term 1761, 1 Geo.

3).

The rule is discussed at length in the leading case

of Commonwealth v. Nesbit, 34 Pa. 398, 403 (1859).

Chief Justice Lowrie describes it as follows:

“ The technical formalities of the old sum

mary conviction are much beyond the ordinary

skill of justices of the peace in this country;

and for this and other reasons, some parts of

them have been much condemned in modern

legislation. But it is still essential, that a sum

mary conviction shall contain a finding that a

special act has been performed by the defend

ant ; and that it shall describe or define it, in

such a way, as to individuate it, and show that

it falls within an unlawful class of acts. With

out this, a judgment that the law lias been vio

lated gives nothing.

“ Now this is not merely a formal or techni

cal rule of summary convictions, but a most

essential and substantial one. No citizen can

have any sort of protection against the igno

rance or wickedness of inferior magistrates,

if these were authorized to convict citizens of

offenses, and yet allowed so to record their

proceedings, that the very act done, cannot be

ascertained, and thus their judgment cannot be

tested by their judicial superiors.

“ A sentence is reversed, if the record do

[sic] not show the commission of a well de

fined act that is forbidden by law.”

This rule as to the record on certiorari has been

consistently applied since, usually quoting the

above passage of Chief Justice Lowrie: Common-

ivealth v. Ayers, 17 Pa. Superior Ct. 352, 358; Com

monwealth v. Cannon, 32 Pa. Superior Ct. 78; City

of New Castle v. Genkingen, 37 Pa. Superior Ct. 21;

Commonwealth v. Ba-rhono, 56 Pa. Superior Ct. 637.

And habeas corpus will lie to discharge the defend

ant if he be imprisoned on such a record. Common

wealth v. Div.oskein, 49 Pa. Superior Ct, 614. In

City of New Castle, supra, the Court strikes at the

heart of the defect, saying about the record, 37 Pa.

Superior Ct. at 27:

“ It will be noted that the justice does not

find that the facts set forth in the information

are true.”

13

Argument

14

Argument

Indeed, it would appear that only by certiorari

could the defects complained of by the petitioners

be raised before the Court below. In Commonwealth

v. Palms, 141 Pa. Superior Ct. 430, 438, the Court

stated:

“ 14: will be noted that the defendant did not

proceed by way of certiorari to the court of

common pleas; hence we are not concerned

with alleged errors in the form of the com

plaint or the transcript of the justice. He chose

the remedy by appeal to the court of quarter

sessions, which constituted a waiver of formal

defects in the proceedings before the justice.”

See also Commonwealth v. Conn, 183 Pa. Superi

or Ct. 144; Commonwealth v. Goldberg, 31 D. & C.

2d 373 at 375. (“ By proceeding on appeal rather

than by writ of certiorari, appellants have waived

any defects in the Magistrate’s hearing, therefore,

compelling us to sustain their convictions.” per

Judge Chudoff.)

It thus follows that certiorari does not waive the

Constitutional infirmity of no evidence. It would

be absurd if it did because the method urged by the

District Attorney obtains a trial de novo by which

an entirely new record is made without reference

to the evidence, if any, below. An appeal from a

court not of record does not review the proceedings

below. Its purpose is to secure the proper admis

sion or exclusion of testimony, to present a defense,

and to secure a re-evaluation of the controverted

facts. This conviction being without any support

ing evidence or finding of fact cannot stand.

Argument

15

3. THE MAGISTRATES’ COURTS OF PHILA

DELPHIA ARE CONSTITUTIONALLY LIMIT

ED IN THEIR JURISDICTION TO HEARING

CASES INVOLVING CITY ORDINANCES UN

DER WHICH THE PENALTY SOUGHT IS ONE

HUNDRED DOLLARS OR LESS

The municipal ordinance under which the appel

lants were convicted provides a penalty of from

$50 to $300 along with imprisonment for failure to

pay. There was no suggestion or demand by the

District Attorney for a penalty less than the maxi

mum. The amount in controversy, as to each peti

tioner, was $300 and the question was, how much

of that sum, if any, were they liable for individu

ally.

Appellants argued below that the Magistrate had

no jurisdiction over the subject matter when the

penalty exceeds one hundred dollars. Even though

a judgment be rendered within Iris jurisdiction

(less than $100), the Magistrate’s jurisdiction is

not thereby determined or created. To hold other

wise would be to allow a magistrate to legislate and

carve an enclave of jurisdiction by his own fiat in

holding down the size of the penalty.

Since the Magistrate can not know beforehand

whether the case before him warrants the minimum

penalty or the maximum penalty, which he has no

authority to levy, how can it be argued, as the Com

monwealth has done, that the minimum penalty

shows that the Magistrate had jurisdiction. This

16

Argument

contravenes the most fundamental principle of ju

risdiction, and, indeed, the law expressly negatives

such a concept of “ Jurisdiction by Balkanization.”

“ The limitation of the justice’s jurisdiction

is ordinarily determined by the character and

amount of the punishment which may be in

flicted in a particular case, and in determining

whether a criminal case is within the jurisdic

tion of a justice of the -peace the maximum

punishment that might he imposed is . con

trolling, and the fact that the minimum punish

ment is -within his jurisdiction is immaterial.”

(Italics added.)

31 Am. Jur., Justices of the Peace, §57.

Any determination of the jurisdiction of the

Magistrate must begin with Art. 5, §12, of the Con

stitution of Pennsylvania,3 which creates the Magis

trate Courts in Philadelphia “ with jurisdiction not

3 Article 5, §12 provides: “ in Philadelphia there

shell be established, for each thirty thousand inhabitants,

one court, not of record, of police and civil causes, with

jurisdiction not exceeding one hundred dollars; such

courts shall be held by magistrates whose term of office

shall be six years, and they shall be elected on general

ticket at the municipal election, by the qualified voters at

large; and in the election of said magistrates no voter

shall vote for more than two-thirds of the number of per

sons to be elected when more than one are to be chosen;

they shall be compensated only by fixed salaries, to be

paid by said county ; and shall exercise such jurisdiction,

civil and criminal, except as herein provided, as is now ex

ercised by aldermen, subject to such changes, not involving

17

exceeding one hundred dollars ” in “ police and civil

causes ’

In opposition to this Constitutional limitation,

■which allows for no enlargement by its express

terms, the Commonwealth urged below only a part

of the Act of April 15, 1835, P. L. 291, §7, 42 P.S.

§291, which provides in full as follows:

“ The aldermen and justices of the peace of

every city, incorporated township, and borough

in this Commonwealth, shall have power to

hear and determine all actions of debt for pen

alty for the breach of any ordinance, by-laws

or regulations of such city, township or bor

ough, in the same manner, and subject to the

same right of appeal as debts under one hun

dred dollars, and such actions shall be. insti

tuted in the corporate name of such city, town

ship or borough.”

and argued that for breaches of ordinances the

magistrate has plenary jurisdiction, regardless, of

the amount involved, since the Act antedates the

Constitution and, presumptively, was incorporated

therein. The weakness of this argument is made

manifest by the clear language of the Pennsylvania

Constitution of 1874, Art. 5, §12, which, on its face,

repeals the Act of April 15, 1835, in so far as it

could be deemed to relate to the City of Philadel-

an increase of civil jurisdiction or conferring political du

ties, as may be made by law. In Philadelphia the office

of alderman is abolished.” (Amendment of November 2,

1909.)

Argument

18

Argument

pink.- See, '1- Sutherland, -Statutory Construction,

§2025 (ed. Ed.). That the Court below was misled

by this argument of the District Attorney, predi

cated upon a distorted citation of the Act, is patent

from the Court’s ruling in dismissing petitioner’s

exception No. 4, wherein the Court said 16a) :

‘ ‘ In that: Act of 1835 there is no provision as

to. the limitation upon the jurisdiction by vir

tue of the amount in controversy.”

Repeated urgings by appellants’ counsel that the

Commonwealth, was citing the A ct. improperly and

omitting key language from its citation went un

heeded by the learned Court below. Divinatio, non

interpretatio esty quae omnia recedit a liter a.

There is vastly more involved in this controversy

over the Magistrate’s jurisdiction than a “ One

Hundred Dollar Misunderstanding” between appel

lants and the Commonwealth. The issue strikes at

the vitals of the Magistrate’s jurisdiction ab initio

to hear these charges against appellants.

The plain language of the Act of 1835 shows that

it grants power to hear actions of debt for breach

of any ordinance only. The magistrate1 herein did

not entertain or hear an action of debt, but a crimi

nal prosecution. Even assuming, arguendo, that the

Commonwealth’s position is sound and the Act of

1835, which is silent on magistrates, the office being-

then unknown, prevails over the Constitution of

1874, which created the office and sets forth its

jurisdiction, and the dollar amount is not a juris

dictional limitation, the statute, nevertheless, by its

Argument

19

plain terms, still could not be authority for juris

diction in this case since it is limited to cases com

menced and heard as civil actions of debt. The

jurisdiction of the magistrate must be explicit in

the statute. Byers v. Olander, 161 Pa. Superior Ct.

165 (1947).

Appellants submit that the Act of 1835 must be

construed to authorize the hearing of one hundred

dollar ordinances exclusively. Otherwise, the con

stitutional interdiction in Art. 5, §12, against an

increase in the civil jurisdiction of the magistrate

would render the statute unconstitutional since it

would allow Philadelphia magistrates to hear all

actions for breach of city ordinances without re

gard to . the amount in controversy.

If this were so, the magistrate could hear a case

involving any ordinance and impose any penalty

provided. This, the Constitution of Pennsylvania

expressly prohibits in Philadelphia. And because

of such prohibition, Art. 5, §12, of the Constitution

must be deemed to have effected a pro tanto re

peal of the Act of 1835 as it relates to Philadelphia.

“ . . . statutes may be nullified, in so far as

. future operation is concerned, by a constitution

as well as by statute; and the constitution, as

the highest and most recent expression of the

law making power, operates to repeal, not only

all statutes that are expressly enumerated as

repealed, but also all that are inconsistent with

the full operation of its provisions.” 12 C.J.,

Constitutional Law, §97, pp. 725-726.

20

Argument

Thus, it is patent that Art. 5, §12 of the Consti

tution intended to curtail the broad grant of the

Act of 1835. The office of aldermen was abolished

therein, and the office of magistrate created. As

such, magistrates can have no power not author

ized by the organic instrument of their creation.

‘ ‘ Since the Constitution of its own vigor, and

as the sole source of all delegated authority,

vests the judicial power in designated tribu

nals, it follows that the essentials of jurisdic

tion there conferred are unalterable and inde

structible, and can neither be increased nor

diminished by the legislature . . . ”

12 C. JConstitutional Law, §260, p. 816.

It is thus submitted that the Act of April 15,

1835, P. L. 291, 42 P.S. §291, gives no authority to

Philadelphia magistrates for the office was non

existent until 1875. The authority of magistrates

to hear cases of ordinances rests solely on the Con

stitutional grant of Art. 5, §12. That grant is a re

stricted grant and cannot be enlarged by any stat

ute. 12 C.J., Constitutional Law, supra. Were it

otherwise, the Act of December 9, 1955, P. P. 817,

§1, 42 P.S. §241, which provides:

“ The aldermen, magistrates and justices of

the peace, in this Commonwealth, shall have

concurrent jurisdiction with the courts of com

mon pleas of all actions arising from contact,

either express or implied, and of all actions

of trespass, wherein the sum demanded does

not exceed five hundred dollars ($500.00), ex

cept in cases of real contract, where the title

Argument

21

to lands or tenements may come in question.”

As amended 1955, Dec. 9, P. L. 817, §1.

would have enlarged the magistrate’s jurisdiction

to five hundred dollars. This Act is ineffective as

to Philadelphia magistrates! because of the consti

tutional proscription against an increase in civil

jurisdiction. Likewise, any statute, or group of

statutes, which would increase the jurisdiction in

excess of the constitutional limit of one hundred

dollars is ineffective for that purpose.- It is only

because Art. 5, §12, allows magistrates to hear

cases formerly heard by aldermen that a magis

trate has any authority to hear ordinance cases at

all. The harm to the defendants was catastrophic.

We will not here brief the defects in the magistrate

system. Of. Rutenberg v. Philadelphia, 329 Pa. 26.

To try the defendant before a magistrate, when he

is entitled to a court of record, is to shear him of

the law’s protection. The Latin expresses the situa

tion succinctly—horribile dictu.

1. THE APPELLANTS’ PREVIOUS ACQUIT

TAL BARS THEIR SECOND CONVICTION

FOR THE SAME ACT

The appellants committed one act. That act was

refusing to leave the premises after being directed

to do so by a police officer. At the time of their

arrest, they were told they were charged with dis

orderly conduct, breach of the peace and trespass

ing. At the outset of their first trial before* the

22

Argument

Magistrate, the charge of trespassing was not

urged by the Commonwealth. At the conclusion of

the trial the Magistrate pronounced all defendants

guilty of disorderly conduct. He made no pro

nouncement on the other charges nor did lie reserve

judgment thereon. An appeal was subsequently al

lowed to the Court of Quarter Sessions by Wein-

rofct, J. on November 11, 1963. The trial de novo

was then scheduled for January 24, 1964 before

(luerin, J. The defenses raised included, inter alia:

that the defendants were petitioning their govern

ment, an activity protected by the Constitutions of

Pennsylvania and the United States; that the stat

ute was void for indefiniteness on its face; that

the statute failed to give adequate notice that the

act of the petitioners wras proscribed; and, that

on the whole record there was no evidence tending

to show guilt and hence the due process clause of

the 14th Amendment required a finding of not

guilty.

The trial judge entered a verdict of not guilty aw

to all defendants. The docket entries from the for

mer case are printed in the record pursuant to

Rule 34 (la-2a).

In the instant case, the Court was asked to take

judicial notice of its own records and apply the

rule of autrefois acquit. The Commonwealth ar

gued that since the offense charged was different,

the nde did not apply. The appellants, of course,

conceded that the charge was different in name.

It caii be noted, however, that the present charge

is, in effect, the former charge of trespassing in

Argument

23

more sophisticated terminology. The Common

wealth argued that the failure to leave constituted

an unauthorized use of the building, presence and

use becoming synonomous. The appellants relied

on the previous decisions in this state to the effect,

that where one act constitutes several offenses and

the state elects to prosecute for some, but not all

of them, it cannot thereafter institute new prose

cutions for the remainder. Commonwealth v. Bishop,

182 Pa. Superior Ct. 151; Commonwealth v. Comber,

374 Pa. 57. This contention was not met or an

swered by the Court below'. Instead, upon being

orally advised, by the District Attorney, that the

prior proceeding had been upon a writ of habeas

corpus, the Court decided the issue on that ground

despite counsel ’s oral advice; that no writ of habeas

corpus had ever been sought by tlie petitioners, or

over issued.

Finally, the Commonwealth argued that Excep

tion No. 13 was not sustainable on certiorari with

out citing any authority. This Court has made clear

that such a plea is tested by the record. Common

wealth v. Comber, supra, and the cases cited there

in..

This issue was raised before the Magistrate and

argued.by counsel. The District Attorney counter-

argued bv reading into the record excerpts from

the transcript of the previous trial to show that the

offense, disposed of earlier in the Court of Quarter

Sessions, was .not the same in name. The' District

Attorney also argued that the offense of breach

of the peace had been left, open by the Magistrate

from his hearing on September 27, 1963. Counsel

re-argued that breach of the peace could not be still

open unless the Magistrate had violated the Act of

May 9, 1949, P. L. 1028, Sec. 14, 42 P.S, 1144(d)

and (e) requiring prompt decisions.

In the Court of Common Pleas, the District At

torney argued that such a plea was not made be

fore the magistrate in the necessary old law French.

Such words have not been necessary since the Act

of March 31, 1810, P. L. 427, Sec. 30, 19 P.S. 464,

which provides:

“ In any plea of autrefois acquit or autrefois

convict, it shall be sufficient for any defend

ant to state he has been lawfully convicted or

acquitted, as the case may be, of the offense

charged in the indictment.” 4

Such a plea is available for summary offenses,

Commonwealth r. Beatty, 91 Pa. Superior Ct. 37;

Mars teller v. Marsteller, 132 Pa. 517; Common

wealth v. Bergen, 134 Pa. Superior Ct. 62. In the

instant case, the Common Pleas Court had before

it the information do cribing the acts constituting

the second offense, and the entire proceeding of the

first trial. The most cursory examination would

have revealed the identity of the act alleged to have

been committed in both cases. The decision of the

4 The reporter’s notes to this Act sav,

“ This section proposes in favor of the,accused, to

simplify the pleas of heretofore acquitted, and here

tofore convicted, and thus relieve them from all tech

nical embarrassments. ’ ’

24

Argument

Argument

25

Court below that it need not look at these records

was patently erroneous.

The Commonwealth does not dispute that the

present conviction was for the identical act for

which appellants were previously tried and ac

quitted. It urges that, as long as the charge varies

in name, prior acquittals are of no effect. The

Commonwealth may prosecute for one act as often

as it can change the name of the charge. Such

concept is completely hostile to our laŵ and to our

democratic traditions. Little can be added to the

opinion of Justice Black in Bartkus v. Illinois, 359

IT. S. 121, 152.

Our traditional abhorrence of the misuse of the

state’s immense resources against an individual by

repetitious prosecutions and suits has resulted in

an eminent line of opinions to the effect that a

criminal prosecution bars a later suit for a penalty

which arises out of the same act. United States r.

JniFranca, 282 IJ. K.. 5(58; United Slates r. (1 idden

Un., 78 F. 2639; United Slates r. dun, .38 F. 2d. 593;

United States v. Ulrici, 102 U. S. 612; United States

v. Charteau, 102 U. S. 602; United States in Seattle

Brewing Co., 135 F. 597; United States v. Oates,

Fed. Cas. No. 15, 191 ; United States v. McKee, Fed.

Cas. No. 15, 688.

This case was a second criminal prosecution ar

raying the pow'er and resources of the state against

such meagre resources as the appellants could com

mand. How many times must this unequal struggle

l)e waged? How many times can appellants be ar

26

Argument

rested! How many times must they put down then-

daily occupations and take up their defense! Their

resources are exhausted, but the resources of the

state are inexhaustible. Shall there be trial by law

or trial by ordeal!

CONCLUSION

On its face, this record shows the conviction of

appellants for a comparatively minor offense. Yet,

iii such a conviction the full force and weight of

the Commonwealth becomes exposed, and the true

issues surrounding the conviction emerge into the

light. Appellants, at the time of their arrests, were

protesting, as the Constitution of the United States

allows them to do, certain shortcomings in the

housing relocation program of the City of Phila

delphia. The inadequacies of this program fell

mainly on the shoulders of Negro residents living-

in sub-standard housing. Because of their protest,

they Were twice arrested, and the second time

charged with violating the City ordinance. This

was. unmistakably an endeavor by Commonwealth

and City officials to quell the voice of protest.

If this Court allows these illegal convictions to

stand, a serious impediment and an enormous in

cubus will be engrafted onto the administration of

justice in this Commonwealth. For the appellants,

who have been singled out for prosecution because

of the proper exercise of their Constitutional

A rgument

27

rights, recognize. that this Court has the power to

undo the harm that has been done to them below.

It was Edmund Burke, in his Letter to the Sheriffs

of the City of Bristol on the Affairs of America,

written April 3, 1777, who stated

"People without much difficulty admit the

entrance of that injustice of which they are

not the immediate victims. In times of high

proceedings it is never the faction of the pre

dominant power that is in dangerf for no tyr

anny chastises its own instruments. It is the

obnoxious and the suspected who want the pro

tection of the law . .

The "high proceedings,” which resulted in the

convictions of the appellants, without an iota of

evidence to support such convictions, consisted of

a purposeful and systematic effort to ignore the

law oil magistrate’s jurisdiction, the law on prior

acquittal, the law on using criminal process to en

force civil penalties, and to mislead the Court be

low on the nature of its scope of review on cer

tiorari. The great English philosopher Herbert

Spencer, in his Social Statics, cautioned that, " le

gal forms are commonly used for purposes of op

pression” and called for an end to the practice.6

Appellants herein, similarly, call upon this Court

to reverse their convictions and, thus, vindicate the

r> Burke’s Politics: Selected Writings and Speeches

.(Ed. by Ross, J. S. Hoffman and Paul Levack, Alfred A.

Knopf Co.. New York 1949), pp. 98-99.

e Spencer, Social Statics, p. 113 (London, 1892).

28

Argiitneni

proper administration of justice, which does not

countenance the use of judicial machinery for the

purpose of oppression.

Appellants seek no special favors or considera

tions. They ask only that any proceedings against

them be according to our law, and that their rights

be the same as the rights of their fellow citizens.

This is their entitlement under our heritage. Yet

it would be error to assume that the rights asserted

by the appellants serve only their interests. The

questions presented are ones of great public im

portance concerning which there has been much un

certainty. Commonwealth v. Ashenf elder, 413 Pa.

517. Despite much criticism, the minor judiciary

will be part of our judicial system for yet some

time. Its duties, and the limitation of its powers,

should be made clear. It is apparent that the offi

cials and the courts of the most populous city of

the Commonwealth misapprehend the duties and

the limits of the Magistrates.

In addition, our high principles of justice .and

orderly procedure become a mocking slogan if

they are not available to those who' require them.

Such principles must be continually pronounced

and applied else they perish in the whirlpool of ex

pediency. The words of our Court, though written

a hundred years ago, are still appropriate:

“ All men are liable1 to' err, and the law-mak

ing power, with the best motives which the

purest hearts furnish, may err. It is here,

however, in this Court, of last resort, that .the

Argument

29

private citizen must look for the preservation

of his private rights. Here is the ark of his

safety, and the goal of his peace; and when the

humblest citizen comes into this Court with the

constitution of his country in his hand, we dare

not disregard the appeal.” Broivn v. Hummel,

6 Pa. 86 at 97.

Respectfully submitted,

W il lia m L ee A kers ,

H arry L ore,

Attorneys for Appellants.

Docket Entries

la

RECORD

IN THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS NO. 2

OF PHILADELPHIA COUNTY

No. 4604 December Term, 1963

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

vs.

Jerome Dortort, -Jake Tiles, Frederick Feldman,

Frank Delano Haley, Geoffrey Lobenstine, Wal

ter Lively, Margaret Ann Neissner, Florence

Johnson, Susan Mayer, and Lillian Mirmak

RELEVANT DOCKET ENTRIES

‘•■‘•Docket Entries of Former Acquittal Pursuant

To Rule 34”

C ourt of Q uarter S essions

Misc. No. 759 October Term, 1963

2a

Docket Entries

10-4-63, Jerome Dortort et al. Appeal Summary

Conviction Disorderly Conduct.

10-22-63, Room 646, 10:00 a.m. Held under advise

ment. Weinrott, J.

11.-11-63, Appeal allowed. Weinrott, J.

1-24-64, Not guilty—all monies returned. Guerin, J.

Tx C omm on I ’ okas No. 2

No. 4604 December Term, 1963

4604

W. 1j. Akers App. for Deft.

Feb. 20, 1964, Petition for Writ of Certiorari.

Feb. 20, 1964, Rule upon the Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania and Magistrate William Hagan

to show cause why Writs of Certiorari should

not issue. All proceedings to stay meanwhile.

Eo die, Petition filed.

Mar. 12, 1964, Rule absolute. The Prothonotary

shall issue the Writ of Certiorari directed to

Magistrate William Hagan, requiring him to

certify to this Court the record within 10 days.

All proceedings to stay meanwhile.

Eo die, Order entered.

Mar. 18, 1964, Writ of Certiorari to Magistrate W il

liam Hagan Ret. 1st Monday of April 1964.

Docket Entries

3a

Mar. 26, 1964, Written record opened—returned to

office and filed.

Apr. 7, 1964, I)efts., by their counsel, file excep

tions to the return of Magistrate filed.

May 22, 1964, Petition dismissed as to all defend

ants. Guerin, J .

May 29, 1964, Execution of sentences affirmed May

22, 1964 stayed for 30 days in order for- defend

ants to petition for Certiorari from Supreme

Court—order filed.

Aug. 4, 1964, Certiorari from Superior Court, Oct.

Term 1964 #572 brought into office and filed.

Jerome Bortort et al. appellants. Fee pd.

$12.00.

Aug. 18, 1964, Acceptance of Charles L. Guerin,

Judge and of Mildred G. Kelly, stenographer

of notice of Appeal filed.

Oct. 27, 1964, Opinion filed.

4a

M agist rate’s Transcript

II.

MAGISTRATE’S TRANSCRIPT

Pursuant to the mandate of this Honorable Court,

dated March 18, 1964, I, William Hagan, Magis

trate of the City and County of Philadelphia,

Court No. 15, do hereby certify and send, together

with the Writ of Certiorari, the record of the afore

said action with all things touching the same:

Defendants, Jerome Dortort, Jake Jiles, Freder

ick Feldman, Frank Delam> Haley, Geoffrey Loben-

stine, Walter Lively, Margaret Ann Neissner, Flor

ence Johnson, Susan Mayer, and Lillian Mirmak, as

well as one Joseph Harvey, were charged in a

sworn complaint, executed by and sworn to under

the oath of Frank Rizzo, Deputy Commissioner of

Police of the City of Philadelphia, an attested copy

of which complaint is hereunto attached and made

part hereof, with breaches of the peace and with

violating the provisions of Chapter 10-500, Section

10-501 (2) (h) of the Philadelphia Code in that each

of the defendants did use a City facility, namely,

the office of the Development Coordinator, Room

210, City Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and en-

teied into said City Property, and remained there

in, without authority, and refused to leave the same

when lawfully requested so to do, the said offenses

being committed on the 20th day of September, 1961!

at and in Boom 210, City Hall, Philadelphia, Penn

sylvania.

Pursuant to- said sworn complaint and intonua

lion, which was filed with me on January 31, 1964,

summonses were duly issued by me, under my hand

and seal and served upon each of said defendants,

together with copies of the complaint, summoning

each of the defendants to appear before me at Boom

625 City Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on Feb

ruary 4, 1964. The original summonses and pre

cepts as to each defendant are hereunto attached

and made part hereof.

Also attached hereto and made part hereof, are

copies of the docket entries as to each defendant,

showing, inter alia, the names of the witnesses who

appeared, at the hearing held before me on Febru

ary 1.4, 1964, and who, after being duly sworn ac

cording to law, testified.

All of the defendants, with the sole exception of

defendant, Joseph Harvey, appeared and were rep

resented by counsel and were given an opportunity

to examine all witnesses. None of the defendants

testified nor did they offer any witnesses in their

behalf.

After considering all evidence presented, all de

fendants, with exception of defendant Joseph Har

vey, who did not appear, were adjudged guilty of

violating the provisions of Section 10-501 (2) (h)

of the Philadelphia Code of City Ordinances and

were sentenced to pay a fine of $50.00 and costs of

$2.50 or imprisonment for 10 days in County

5a

Magistrale’s Transcript

Prison. As to the charge of breach of peace, each

defendant was discharged.

1 hereby certify that the above is correct return

and transcript from the docket of my Court.

Witness our said Magistrate and the official seal

of said Court on the 26tli day of March, 1964.

William Hagan

Magistrate Court No. 15

( Seal)

Get

Magistrate’s Transcript

AFFIDAVIT AND INFORMATION FOR

ISSUANCES OF CRIMINAL

SUMMONS

City and County of Philadelphia,

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, ss:

Frank Rizzo, being duly sworn according to law,

deposes and says: that lie is a Deputy Commission

er of Police of the City of Philadelphia; that with

in the City and County of Philadelphia, State of

Pennsylvania, and within two years last past, to

wit: on or about Friday, September 20, 1963, and

in the offices of the Development Coordinator,

Room 210, City Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania;

being a department of the government of the City

of Philadelphia, the following named persons to wit:

Jerome Dortort, Jake Jiles, Frederick Feldman,

Joseph Harvey, Frank Delano Haley, Geoffrey

Lobenstine, Walter Liveley, Margaret Ann Neisser,

Florence Johnson, Susan C. Mayer and Mary Lilli

an Minnak, did commit breaches of the peace, caus

ing consternation and alarm which disturbed the

peace and quiet of the community all of which was

against the law and against the peace and dignity

of this Commonwealth.

And, deponent further avers that the said above-

named person on said date and at said place did in

violation of Chapter 10-500, Section 10-501 (2) (h)

of the Philadelphia Code of General Ordinances use

a City facility, namely; the office of the Develop

ment Coordinator, Room 210, City Hall, Philadel

phia, Pennsylvania, and entered into said City

property, and remained therein, without authority,

and refusing to leave the same when lawfully re

quested so to do, all of which was against the law

and against the peace and dignity of the City of

Philadelphia and this Commonwealth.

Wherefore, deponent requests the issuance of a

criminal summons against each of the above named

persons summoning each of them to appear in the

manner and form as prescribed by the Act of As

sembly No. 617, approved September 18, 1961.

All of which deponent avers to be true to the best

of his knowledge, information and belief.

(s) Frank Rizzo

Frank Rizzo

Sworn to and subscribed before me this 30th day

of January, 1964.

Milton S. Logan

Notary Public

[Illegible]

7a

Magistrate’s Transcript

True and attested copy.

William Hagan

Magistrate Court No. -l~>

■8 a

Magistrate’s Transcript

POLICE CRIMINAL 'SUMMONS

No. 9581

Magistrates Court No. 15, County of

Philadelphia

To Jerome Dortort, 3718 Spring Garden St.

Complaint having been made this day by Deputy

Commissioner Frank Rizzo that you charged with:

Breach of the Peace and Viol. City Ordinance

10-501 (2) ( in.

You are hereby summoned to appear before me,

Magistrate of Court No. 15, at Room 625, City Hall,

Central Police Court, on the till day of February,

1964, at 2 o ’clock p.m., to the end that an investi

gation may be made of the said complaint and up

on your failure to appear at the time and place

herein mentioned you are liable to a fine not ex

ceeding one hundred dollars ($100).

Date at 11:00 aim. this 31st day of January, 1964.

Signed William Hagan

[Note: Nine other Summonses, being identical,

are omitted.]

Jerome Dortort, Complaint filed on 1-31-64 by

Deputy Commissioner Frank Rizzo charges Breach

Magistrate’s Transcript

9a

of the Peace and violation City Ordinance 10-501

(2)(h), Criminal Summons 9581 issued on 1-31-64

by Magistrate Hagan.

Date: 2-4-64, Place: Room 254 City Hall.

A ttys, for defendant: Wm. Akers, Harry Lore,

David Cohen, Edwin Wolf.

Atfy. for Prosecution: Chas. Bogdanoff, A.D.A.

This case was turned over to United States Dis

trict Court.

This case was returned to- Magistrate’s Court and

was heard 2-14-64 at 625 City Hall.

Witnesses

Richard H. Buford, 402 S. 9th St.

Deputy Commissioner Frank Rizzo.

Loretta Logan, 5748 Walnut St.

Inspector' Frank Nolan.

Disposition of Indictable Offenses

Defendant discharged.

Disposition of Summary Offenses

Defendant Jerome Dortort found guilty of Viol.

City Ordinance 10-501 (2)(h) and sentenced to pay

a fine of $50.00 and costs of $2.50 or imprisonment

for 10 days in C.P.

[Note: Nine other Statements, being identical,

are omitted.]

10a

Exceptions

III.

DEFENDANTS BY THEIR COUNSEL, FILE

THESE EXCEPTIONS TO THE RETURN OF

THE MAGISTRATE

1. The return shows a criminal prosecution for

a civil offense.

2. The return shows the prosecution was insti

tuted in the name of the Commonwealth who is not

a proper party to do so.

3. The return shows the prosecution was con

ducted by the District Attorney who had no power

to so conduct.

4. The return shows that the amount involved

was $300.00 whereby the Magistrate has no juris

diction to adjudicate it.

5. The return shows the summons were issued

for a hearing on February 4, W(>4 and that the

hearing was actually held ten days later.

6. The return fails to show service of the sum

mons on any defendant.

7. The return fails to show any finding of fact

or 'to describe how the offense was committed.

8. The return fails to summarize or allude to

any testimony.

Exceptions

11a

9. The return fails to show that any of the de

fendants were identified as being at th© place of

the alleged offense.

10. The return fails to show the time the alleged

offense was committed.

11. The return shows a conviction without any

evidence.

12. The return shows the defendants were

charged inter alia with having “ remained there

in” which is not an act prohibited by the Ordinance

under which they were convicted.

13. The return indicates that the defendant’s

plea of autrefoi acquit should have been sustained

by reason of their previous acquittal for the same

act in the Court of Quarter Sessions, Misc. No.

759, October Term, 1963, Guerin, J. presiding, Jan

uary 24, 1964.

Wherefore, the defendants pray this Court to

sustain this appeal and reverse their convictions.

William hoe Akers

Attorney for Defendants

12a

Opinion

IV.

HEARING OF M AY.22, 1964

Room 443(H) City Ilall, Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, Friday, May 22, 1964

Before: Hon. Charles L. Guerin, J.

Appearances

Charles Jay Bogdanoff, Esq. (Acting as City

Solicitor), for the City of Pliila.

William Lee Akers, Esq., for the Petitioners.

A rgnment

THE COURT: The proceedings in this matter

were originated by the filing with Magistrate Ha

gan of an affidavit taken by Deputy Commission

er of Police, Frank Rizzo, in which he complained,

first, that the persons named in these proceedings

as- defendants were guilty of breach of the peace;

and, secondly, they were guilty of violating a City

Ordinance, Section 10-501 (2) (h) of the Code.

The respondents or defendants subsequently ap

peared before Magistrate Hagan, after intervening

13a

delays which it is not necessary to recount herein,

and at the conclusion of the hearing Magistrate

Hagan discharged all the defendants of any crimi

nal responsibility for what they were alleged to

have done.

As a portion of his return, lie indicated that he

had imposed a fine of Fifty Dollars and costs upon

each of the defendants on the violation of the above-

mentioned provision of the City Charter, which

provides for a fine of not less than Fifty Dollars

nor more than Three Hundred Dollars, together

with imprisonment not exceeding ninety days, if

the fine.and costs are not paid within ten days.

This proceeding has some unusual features in

that it was instituted in the name of the Common

wealth of Pennsylvania and it embodies two differ

ent sets of complaints, one clearly within the crim

inal law, and the second, clearly within the civil

law.

Now, whether that is fatal or not is for me to

deterinine, and 1 hold that it is not fatal, if it was

error. The parties appeared and had their hear

ing. Undoubtedly, Magistrate Hagan had jurisdic

tion to hear the complaint with respect to- breach

of the peace, had that alone been complained o f ;

and, subject to a reservation which I will dispose

of later, the Magistrate had prima facie jurisdic

tion to hear the alleged violation of the City Ordi

nance.

So that I see no error, except perhaps in the

caption of the case which, on the documents before

Opinion

14a

Opinion

me, appears to be Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

against Jerome Dor-tort and others, Court of Com

mon Pleas No. 2, December Term, 1963, No. 4604.

It has been stated that the City Solicitor, Mr.

Ivins, appears before us on behalf of the City of

Philadelphia and has moved to have the caption

amended so as to make it read City of Philadel

phia against the various defendants. I do not have

before me a written motion. If there is such a

written motion, I will allow it. If there, has been

no such written motion filed, I will accept the oral

motion and direct that the caption of the case be

amended to read City of Philadelphia against the

various named defendants.

The matter now comes before me upon excep

tions filed by defendants to the Return of the

Magistrate, as to the allowance ,o.r making absolute

of a Rule to Show Cause why a Writ of Certiorari

should not issue as to each defendant.

So- that. I have before me for consideration only

the question of the regularity of' the proceedings

before the Lower Court.

1 shall now discuss and dispose of all Exceptions

filed by the defendants.

Exception No. 1 is: “ The Return shows a crimi

nal prosecution for a civil offense.”

1 have heretofore indicated that the Return

shows that the criminal prosecution had been dis

posed of and I have before me only the regularity

of the proceedings with respect to the civil offense.

Opinion

15 a

Exception No. 2 reads: “ The Return shows the

prosecution was instituted in the name of the Com

monwealth who is not a proper party to do so.”

I have indicated that the Commonwealth was a

proper party to institute the alleged violation of

the criminal law and, while it is not a proper party

seeking to recover a penalty for violation of a City

Ordinance, that is merely a defect in form which

may be cured at any stage of the proceedings, and

1 have allowed that defect to be cured by changing

the caption of the case from Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania to City of Philadelphia.

Exception No. 3: “ The Return shows the prose

cution was conducted by the District Attorney who

had no power to so conduct.”

That exception has not been urged, but even had

it been urged it would have no merit because who

conducts the prosecution is a matter for the re

sponsibility of the parties seeking to recover for

alleged misconduct and has no bearing upon the

merits of the case.

Exception No. 1: “ The Return shows that the

amount involved was $300.00, whereby the Magis

trate has no jurisdiction to adjudicate it.”

The Magistrate, under a provision of the law of

Pennsylvania which I do not here cite because I

regard it as unnecessary, does indeed have limited

jurisdiction, and that limit is to where the amount

in controversy does not exceed $100.00. However,

there is an earlier Act of Assembly, the Act of

1835, which has been referred to in argument which

does give general jurisdiction to Magistrates or

Justices of the Peace or Aldermen and so forth,

to entertain jurisdiction to recover items such as

that sought to be recovered in this case. In that

Act of 1835 there is no provision as to the limita

tion upon the jurisdiction by virtue of the amount

in controversy.

My view of the. status of this matter is that the

Magistrate, not having exceeded the. jurisdictional

amount to which he is limited, did not thereby lose

jurisdiction; he retained jurisdiction under the Act

of 1835, and the disposition made by him of impos

ing a fine of Fifty Dollars and costs was well with

in the jurisdictional limits of a Magistrate. I,

therefore, dismiss this Exception.

Exception No. 5 was not urged; in fact, ;it; was,

in effect, withdrawn, as was Exception No. 6.

Exception No. 7 reads: “ The Return fails to

show any finding of fact or to describe lmy. the

offense was committed.”

Exception No. 8 reads: “ The Return fails to sum

marize or allude to any testimony.”

Exception No. 9 reads! “ The Return fails to

show that any of the defendants were identified

as being at the place of the alleged offense.”

Exception No. 10 reads: “ The Return fails to

show the time the alleged offense was committed.”

Exception No. 11 reads: “ The Return shows a

conviction without any evidence.,” , . - .

16a

Opinion

Opinion

17 a

Exception 12 reads: “ The Return shows the de

fendants were charged inter alia with having ‘ re

mained therein’, which is not an Act prohibited by

the Ordinance under which they were convicted.”

All of these Exceptions relate to the merits of the

controversy and are not properly reviewable upon

a Writ of Certiorari. For error of the nature com

plained of in these Exceptions, there is a remedy

provided, and that remedy is by appeal to the

Court of Quarter Sessions, not to Common Pleas

Court, and the Court of Quarter Sessions would

then have jurisdiction to hear the matter de novo

and make its findings of fact and of guilt or inno

cence.

For these reasons, those Exceptions are dis

missed.

Exception No. Id reads: “ The Return indicates

that the defendants’ plea of autrefoi(s) acquit

should have been sustained by reason of their pre

vious acquittal for the same Act, in the Court of

Quarter Sessions, Miscellaneous, No. 759, October

Term, 1.963, Guerin, J. Presiding, January 24,

1964.”

This Exception has no merit because it has no

basis in fact. At the hearing which 1 held on Jan

uary 24, 1964, I found that the defendants were

not properly charged with disorderly conduct and,

therefore, I granted a Writ of Habeas Corpus and

discharged the defendants of the offense of dis

orderly conduct, but there still remained open and

undetermined a charge of breach of the peace be-

18a

Opinion

Order

Certificates of Stenographer and Court '

fore the Magistrate who had then made his Return

to me. And 1 noted then for the record that I took

no action with respect to the offense of alleged

breach of the peace, and indicated that that charge

was open for further disposition by the Magistrate

before whom complaint had been made.

For all of these reasons, the Exceptions are dis

missed.

Petition is dismissed.

I hereby certify that the proceedings and evi

dence are contained fully and accurately in the

notes taken by me on the trial of the above cause,

and that this copy is a correct transcript of the

same.

Mildred G. Kelly

Official Stenographer

The foregoing record of the proceedings upon

the trial of the above cause is hereby approved and

directed to be filed.

Judge