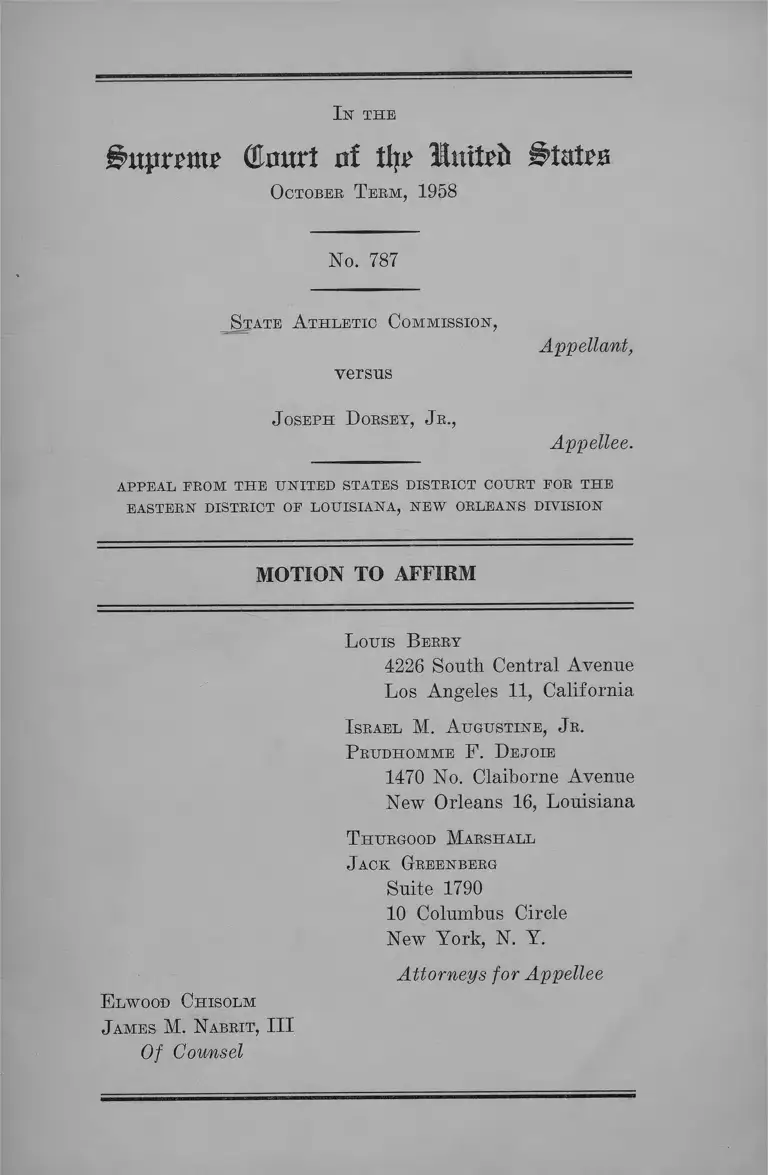

State Athletic Commission v. Joseph Dorsey, Jr. Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. State Athletic Commission v. Joseph Dorsey, Jr. Motion to Affirm, 1958. c764a1fe-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f0f67e84-c3c1-4a51-8674-0b32566482ef/state-athletic-commission-v-joseph-dorsey-jr-motion-to-affirm. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

In th e

Supreme (flmirt of % States

O ctober T er m , 1958

No. 787

S tate A th letic C om m ission ,

versus

Appellant,

J oseph D orsey, J r .,

Appellee.

A P PE A L P R O M T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTR IC T COU RT FOR T H E

EA STE R N D ISTR IC T OF L O U IS IA N A , N E W ORLEAN S DIVISION

MOTION TO AFFIRM

Louis B erry

4226 South Central Avenue

Los Angeles 11, California

I srael M. A u g u stin e , J r .

P ru d h o m m e F. D ejoie

1470 No. Claiborne Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

T hurgood M arshall

J ack Greenberg

Suite 1790

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellee

E lwood C h iso lm

J am es M. N abrit , III

Of Counsel

I n th e

f&npxmt (Limvt at % Itttfrft

O ctober T er m , 1958

No. 787

S tate A th letic C o m m ission ,

versus

J oseph D orsey, J r .,

Appellant,

Appellee.

A P P E A L P R O M T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTR IC T COURT FOR T H E

E A STE R N D ISTR IC T OP L O U IS IA N A , N E W ORLEAN S DIV ISIO N

MOTION TO AFFIRM

Appellee in the above-entitled case moves to affirm on

the ground that the questions presented are so unsubstan

tial as not to need further argument.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the three-judge United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, New Orleans

Division, is now reported at 168 F. Supp. 149.

Statutes

The statute and regulation declared unconstitutional by

the District Court are Louisiana Revised Statutes of 1950,

4:451 et seq. (Acts 1956, No. 579), and Rule 26 of the

Rules and Regulations of the State Athletic Commission.

2

Questions Presented

Appellee, for the purposes of this motion, adopts the

“ Questions” as presented by appellant at pages 3-4 of its

Jurisdictional Statement.

REASON FOR GRANTING THE MOTION

The Questions Presented Are Unsubstantial

I.

Where a state agency purports to act under state au

thority and invades rights secured by the Federal Constitu

tion it is subject to the process of the federal courts, and

an action seeking appropriate relief against such an agency

is not prohibited by the Eleventh Amendment.

Appellant State Athletic Commission concedes, as it

must, that if this action had been brought against the indi

vidual members of the State Athletic Commission, that it

would not be prohibited as a suit against the state within

the meaning of the Eleventh Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States.1 However, appellant asserts

that a distinction may be drawn between suits against

individuals comprising a state board and suits against

the state board, arguing that the principle uniformly ap

plied to the former may not be applied against the latter.

1 Among the many decisions by this Court which require the

concession made by appellants are: Gunter v. Atlantic Coast Line

R. Co., 200 U. S. 273 (1906); Prout v. Starr, 188 U. S. 537 (1903) ;

Smyth v. Ames, 169 U. S. 466 (1898); Tindal v. Wesley, 167 U. S.

204 (1897) ; Reagan v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., 154 TJ. S. 362

(1894) ; Pennoyer v. McConnaughy, 140 U. S. 1 (1891); Ex Parte

Young, 209 U. S. 123 (1908); Alabama Public Serv. Comm. v.

Southern R. Co., 341 U. S. 341 (1951) ; Sterling v. Constantin,

287 U. S. 378 (1932); Georgia R. & Bkg. Co. v. Redwine, 342 U. S.

299 (1952); and many other cases collected at 43 A. L. R. 408.

3

The court below carefully considered the contention and

it is submitted that its disposition of the question was emi

nently correct. After citing School Board of Charlottes

ville v. Allen (4th Cir. 1956), 240 F. 2d 59, cert. den. 353

U. S. 910 (1957) and Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush

(5th Cir. 1957), 242 F. 2d 156, cert. den. 354 U. S. 921

(1957) the court below wrote at 168 F. Supp. 149, 151:

“ The short answer to the Commission’s contention

is that Dorsey’s suit is not against the State of Louis

iana, in name or in effect. It does not attempt to compel

state action, but to prevent illegal action of the Com

mission. As Judge Tuttle stated in the Bush case:

‘If in fact the laws under which the Board here pur

ports to act are invalid, then the board is acting with

out authority from the State and the State is no-wise

involved.’ A state can act only through agents.

Whether the agent is an individual official or a Com

mission, the agent ceases to represent the state when

state power is used in violation of the United States

Constitution.

“ There is no merit to the defendant’s contention

that the plaintiff should have sued the members of the

boxing Commission individually. We agree with the

court in School Board of City of Charlottesville v.

Allen that . . . ‘if high officials of the state and of

the federal government may be restrained and en

joined from unconstitutional action, we see no reason

why a school board [or any other state Commission]

should be exempt from such suit merely because it had

been given corporate powers.’ In Browder v. Gayle,

D. C., 142 F. Supp. 707, aff’d 352 U. S. 903, . . . the

court indicated that it is not necessary to sue the

members of a Commission individually when no spe

cial relief is sought against them by way of damages.

4

In the case before us the plaintiff is seeking relief from

action of the state’s agent, the State Athletic Com

mission, in its collective capacity as a commission.”

Furthermore, Governor of Georgia v. Sundry African

Slaves, 26 U. S. 110 (1828), relied upon by appellant, does

not support the argument made. That was an action

against the Governor of a state rather than a state agency,

but in any event it was litigated prior to the adoption of

the Fourteenth Amendment. Cf. Sterling v. Constantin,

278 U. S. 378 (1932).

That the distinction urged by appellant is without merit

is further demonstrated by Hopkins v. Clemson Agricul

tural College, 221 U. S. 636 (1911) in which no natural

persons were named defendants. That case held:

“ . . . a void act is neither a law nor a command.

It is a nullity. It confers no authority. It affords

no protection. Whoever seeks to enforce unconstitu

tional statutes, or to justify under them, or to obtain

immunity through them, fails in his defense and in his

claim of exemption from suit.” (At 644)

Moreover, “ . . . [I]t cannot matter that the agent is a

corporation rather than a single man.” Sloan Shipyards

Corp. v. United States Shipping Board Emergency Fleet

Corporation, 258 U. S. 549, 567 (1922). The Fourteenth

Amendment is addressed “ to the states, but also to every

person, whether natural or juridical, who is the repository

of state power.” Home Telephone & Tel. Co. v. City of

Los Angeles, 227 IT. S. 278, 286 (1913).

Disposing of an identical contention by reference to

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT. S. 483 (1954), the

Fourth Circuit remarked in School Board of Charlottes

ville v. Allen, supra at 63, that it was “ not reasonable to

5

suppose that the Supreme Court would have directed in

junctive relief against school boards acting as state agen

cies, if no such relief could be granted because of the pro

visions of the Eleventh Amendment to the Constitution.”

II.

A State Statute and an administrative regulation pro

hibiting prize fights between persons of different races

plainly violates rights protected by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

The opinion of the court below is unquestionably cor

rect, and the appeal presents no substantial question on

the merits, for the statute and regulation in question (1)

effect a racial discrimination, contrary to the equal pro

tection and due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment and (2) impair the right to pursue a lawful occupa

tion contrary to the due process clause of that amendment.

(1) With respect to racial discrimination see, of course,

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954); Bolling

v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954). It has been repeatedly

held, in cases relied upon by the court below, that the funda

mental constitutional principles of the Brown and Bolling

cases are not to be restricted to public education. Browder

v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (1956), affirmed 352 U. S. 903;

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City (4th

Cir. 1955), 220 F. 2d 386, affirmed 350 U. S. 877; Department

of Conservation v. Tate (4th Cir. 1956), 231 F. 2d 615 cert,

den. 352 U. S. 838; City of Petersburg v. Alsup (5th Cir.

1956), 238 F. 2d 830 cert. den. 353 U. S. 922; Morrison v.

Davis (5th Cir. 1958), 252 F. 2d 102 cert. den. 356 U. S. 968.

(2) Concerning the right of appellee to pursue his calling

free from arbitrary racial restrictions it is to be remembered

that while professional boxing is subject to regulation by the

state, all regulation must be within the limitations imposed

6

by the Constitution of the United States. Harvey v. Morgan,

Tex. Civ. App., 1954, 272 S. W. 2d 621 is similar to this case.

The Texas Court of Civil Appeals, following the rationale

of the Brown case, invalidated a statute which prohibited

boxing matches, etc. between “ any person of the Caucasian

or ‘white’ race and one of the African or ‘Negro’ race.” 2

See Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33, 41 (1915) in which the

Court ruled that the authority of the states:

. . . “ does not go so far as to make it possible for

the state to deny to lawful inhabitants, because of

their race or nationality, the ordinary means of earn

ing a livelihood it requires no argument to show that the

right to work for a living in the common occupations

of the community is of the very essence of the personal

freedom and opportunity that it was the purpose of

the Amendment to secure.”

See also Takahashi v. Fish db Game Commission, 334 U. S.

410 (1948); Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886).

III.

The appellee had standing to challenge the statute and

regulation involved herein.

Appellant’s objection that appellee had no license as a

prize fighter in Louisiana, on the date of trial, and that this

fact deprives him of standing or sufficient interest to press

this action is clearly unsubstantial. The statement of the

Court below is a sufficient answer. The Court found that:

Dorsey was issued a license for 1957. He has no

license for 1958, but the Commission’s policy is to

issue a license to a prize fighter only on the date of a

scheduled fight and then only after the fight has been

2 The quoted phrase from the Texas statute is identical to a por

tion of Louisiana’s Commission Rule 26, involved in this ease.

7

held and the boxer’s license fee deducted from his

share of the purse. The Commission admits the es

sential allegations of Dorsey’s complaint and admits

also that it would not allow Dorsey to engage in a mixed

prize fight in Louisiana. (At 168 F. Supp. 150-151)

And of course, it was admitted by the answer that Dorsey

was licensed and in good standing when the action was com

menced.

In any event, Dorsey’s interest is no less substantial than

that of the plaintiffs in Truax v. Raich, supra, at 38-39, and

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 (1925).

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the questions presented

by appellant are clearly unsubstantial and this motion

to affirm should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Loins B erby

4226 South Central Avenue

Los Angeles 11, California

I srael M. A u g u stin e , Jr.

P ru d h o m m e F. D ejoie

1470 No. Claiborne Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

T hurgood M arshall

J ack G reenberg

Suite 1790

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellee

E lwood Ch iso lm

J am es M . N abrit , III

Of Counsel