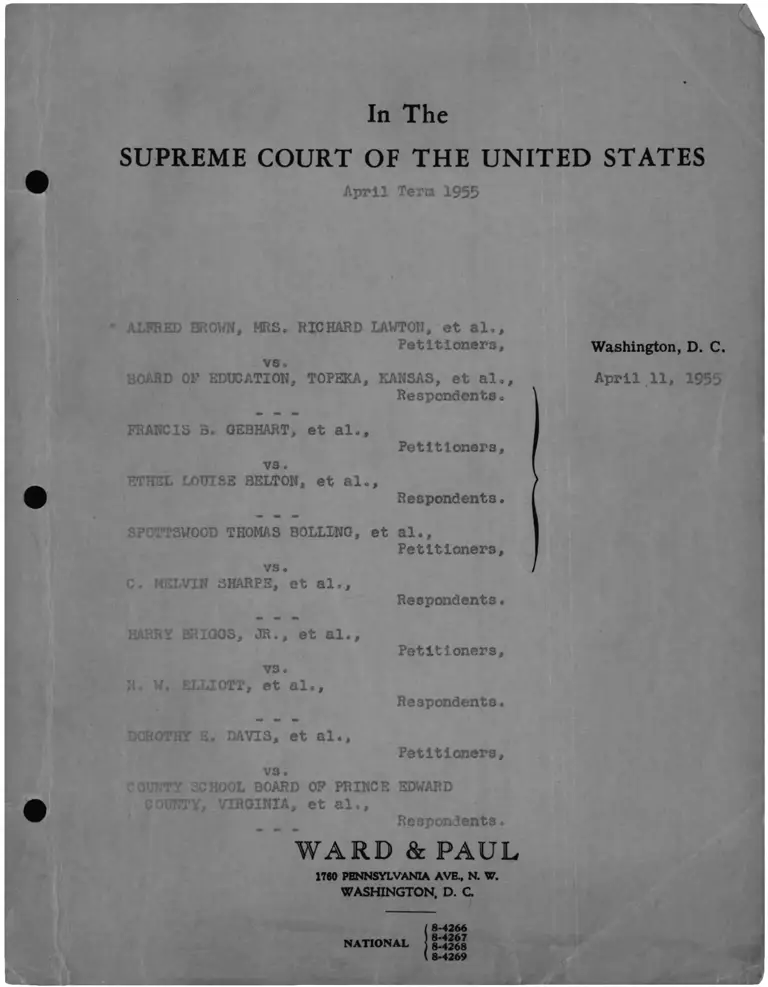

Brown v. Board of Education et al. Arguments

Public Court Documents

April 11, 1955

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education et al. Arguments, 1955. 14d16d9f-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f100845f-153b-46e9-88cb-edcd082bca7d/brown-v-board-of-education-et-al-arguments. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

April Term 1955

• ALFRED BROWN, MRS. RICHARD LAWTON, et al„,

Petitioners,

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION, TOPEKA, KANSAS, et al..

Respondents.

FRANCIS 3. GEBHART, et al.,

vs.

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, et al.,

Petitioners,

Respondents.

SPOTTSWOOD THOMAS BOLLING, et al..

Petitioners,

vs.

C. MELVIN SHARPE, et al.,

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., et al.,

vs

II. W. ELLIOTT, et al..

DOROTHY E. DAVIS, et al.,

Respondents.

Petitioners,

Respondents.

Petitioners,

vs.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, et al..

Respondents.

Washington, D. C.

April 11, 1955

1760 PENNSYLVANIA AVB., N. W.

WASHINGTON, D. C

NATIONAL

8-4266

8-4267

8-4268

8-4269

Contents

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF BOARD OF EDUCATION P a g e

Topeka, Kansas

By Mr. Harold R. Fatzer 4

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF OLIVER BROWN, ET AL

By Mr. Robert L. Carter 26

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF FRANCIS B. GEBHART, ET AL

By Mr. J„O. Craven 3S

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, ET AL

By Mr. Louis L.Reading 46

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF SPOTTSWOOD BOLLING, ET AL

By Mr. George Hayes and Mr. James Nabrit 53

70

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF C. MELVIN SHARPE ET AL

By Mr. Milton Korman 83

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF HARRY BRIGGS, JR. AND

DOROTHY DAVIS, ET AL

By Mr. Robinson 102

1

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

APRIL TERM, 1955

'stein

Cantor Fuff

ALFRED BROWN, MRS. RICHARD LAWTON, ET AL

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION, TOPEKA, KANSAS, Et AL

FRANCIS B, GEBHART ET AL,

vs.

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, ET AL,

SPOTTSWOOD THOMAS BOLLING, ET AL,

VS.

C. MELVIN SHARPE, ET AL,

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., ET AL

vs.

R. W„ ELLIOTT, ET AL

DOROTHY E, DAVIS, ET AL

V S .

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL.

Washington, B.C.

April 11, 1955

2

The above-entitled matter came on for oral argument

at 12 noon.

PRESENT:

The Chief Justice, Earl Warren and Associate

Justices Black, Reed, Frankfurter, Douglas,

Jackson, Burton, Clark and Minton,

APPEARANCES:

On behalf of the Board of Education of

Topeka, Kansas:

Harold R. Fatzer, Attorney General of Kansas,

On behalf of Oliver Brown, Et Al:

Robert L. Carter.

On behalf of Francis B. Gebhart, Et Al

Joseph Donald Craven, Attorney General of

Delaware,

On behalf of Ethel Louise Belton, Et Al

Louis L. Reading.

On behalf of Spottswood Thomas Bolling Et Al:

George E.C. Hayes and James M. Nabrit, Jr.

On Behalf of C„ Melvin Sharpe, Et Al:

Milton D, Korman.

On Behalf of Harry Briggs, Et AL

Thurgood Marshall.Spottswood W. Robinson, II;

On Behalf of R. W. Elliott, Et.

Robert LlcC Figg, jr. , and S.E. Rogers.

3

APPEARANCES - continued.

On Behalf of County School Board of

Prince Edv/ard County, Virginia, Et Al:

Archibald G. Robertson, and

Lindsay Almond, Jr., Attorney General of Virginia.

4

Goldstein

Cantor

Ruff

The Chief Justice, No. 1 on the Calendar, Alfred

Brown, Mrs. Richard Lawton, et al, vs. Board of Education of

Topeka, Kansas, et al,

The Clerk, Counsel are present, sir.

The Chief Justice; Attorney General Fatzer.

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF BOARD OF EDUCATION

By Mr. Fatzer.

Mr„ Fatzer; Chief Justice and Members of the Supreme

Court: I am Harold R, Fatzer, the Attorney General of Kansas

and with me today is Mr, Paul E. Wilson, the First Assistant

Attorney General who has previously argued the State’s position

when the question of the answer to Questions 1 , 2 and 3 ,

v/aa argued heretofore.

Today, we appear not as an adversary. We appear

horeetc be of assistance if we can to the Court in helping

it see that proper decrees are imposed and made.

Now in answer directly to the questions, your

Honors, of Nos. 4 and 5 and the subsequent subsections, we

want to say that traditionally in Kansas, segregation has

not been a policy of that state, on a 3 tate level. We suspect

that the Kansas case i^ probably the least complex of any

that is before it. We v/ish to say that that ha3 never been

a matter of state policy. We believe that the decision of

the Court has been received by the students, teachers, school

administrators and by the parents of both colored and white

5

with approval.

In answering and assisting this Court, I shall be

very brief in stating our position, what we believe should be

done with respect to the case that is now before the Court,

that is, the Topeka Board of Education.

Your Honors, we believe that 4-A should be answered

in the negative. We do not believe that the Immediate aad

forthwith admission of the Plaint!ffs--although they may be

in the school; I am not prepared to tell the Court that they

are not, I suspect that they are— would, and as the Board of

Education found, work a hardship, would impair administrative

procedures, and so we would suggest to the Court that no decree

be entered which would forthwith admit any student to the

school of his choice,, Rather, we believe that the Court

should exercise its equitable jurisdiction at all times in

these cases because of the public interest involved, notwith

standing the fact that the Plaintiffs in the case would

undoubtedly have some present and immediate right and personal

right of admission to the schools.

We believe, your Honors— and I want to make a brief

report of a situation that has developed since the brief in

the Kansas case was filed-— we believe that this case should be

reversed, that it should be remanded to the Federal District

Court in Kansas. I should like to tell you and briefly l’eview

the efforts of the Topeka Foard of Education to terminate

6

segregation in the public schools iu that city.

It was commenced on September 3, 1953. The

policy announced by the School Board was to terminate maintenance

of segregation in elementary schools as rapidly as was practica

ble. Five days following that date,to wit* September 8 , 1953,

segregation was terminated in two schools in the city. It

Involved only approximately ten colored children, but they were

living in the district. They were permitted to attend those

schools.

Justice Burton. You referred to the termination of

segregation in the elementary schools?

Mr, Fatzer. That is correct.

Justice Burton: Has it been terminated in

the other schools?

Mr. Fatzer. There is none in Grades 1 to 6, Mr.

Justice.

That was called the first step. The second step was

made on January 20, 1954. And that was effective for the school

term, current school terra, 1954-1955.

At that time, and by order of the Board o? Education,

segregation was terminated in twelve school districts in the

city and transportation was not provided to the Negro school

children living in those twelve districts on the basis that

the child could attend the school of that district but with

the privilege, if he preferred,to attend the colored school

7

which he had been attending. This affected approximately 113

children, plus the ten that had been previously affected from

Step 2— 123 Negro children were placed in the integrated school.

Justice Frankfurter. What is the total of school

population into which these 123 were merged, roughly?

Mr. Father: I v/ill have to refer—

Justice Frankfurter: What magnitude? Was it 10,000,

or 50,000?

Mr. Fatzer: No, nothing of that kind. I think

perhaps the school population in Topeka is roughly 8200, Mr.

Justice.

Justice Frankfurter: So there wa3 no problem of

space and buildings, and none of those problems?

Mr. Fatzsr: In one school there was. One school

in which, in the so-called Polk School there was the space

problem and I think three children were admitted to that

school and others were not because of this space problem.

Justice Frankfurter: And there was no re-districting

of the districts you have?

Mr. Fatzer: Not at that time.

Now I spoke to your honors of a subsequent event

that occurred subsequent to the filing of the State’s brief

here in response to the request of the Court, which occurred

on February 23, 1955. We have with us today the minutes of

the Topeka Board of Education adopted February 23, 1955, which

8

we have filed in the Clerk’s office as a supplement to the

brief filed in this Court in response to questions 4 and 5

propounded by the Court. We file it simply for informational

purposes to show the good faith of the members of the Board

of Education of Topeka in carrying out the previous announced

policy of terminating segregation as rapidly as practicable.

Now this third step, your Honors, is effective

September, 1955. It provides, (x) that segregation has been

terminated in all remaining buildings; (2) That the McKinley

Elementary School, one of the colored schools, be closed and

that it be placed on a standby basis for the coming year; (3 )

That colored schools, Buchanan School, Monroe and Washington

Schools be assigned districts within the areas of the city, the

same as any other school area in the city and that any child

who is affected by the change in the school district— I will

go ahead— any child who is affected by the change in school

district lines as recommended on a map which we did not attach

hereto, be given the option of finishing the elementary grades

In the school in which he attended in 1954 and 1955. That is,

he could attend the school in the district in which he resided

or, if the new district overlaps now into a district that

for erly existed before the re-districting, he can attend

the school that he attended last year. In other words. It is

equally available to both the white and the colored students.

Justice Frankfurter: Have I missed a statement as

9

to the basis or the reasons for which this re-districting was

done?

Mr. Fatzer: The basis of it was done, of course, Your

Honor, on the Court's decision of May, 1954, to comply with the

order of this Court that segregation, per se, was unconstitu

tional. That is the basis of it.

Justice Frankfurter: You mean there were exclusively

Negro schools?

Mr. Fatzer: Ye3 .

Justice Frankfurter: And those v/ere withdrawn from

use by the City?

Mr, Fatzer: One.was, your Honor.

Justice Frankfurter: One was. And the others are

now available to children, intermixed, is that it?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes.

Justice Frankfurter: Was that districting a geo

graphic districting?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes.

Justice Frankfurter: Was there any indication in the

minutes of the Board or in any document you filed as to the

compact geographic nature of this districting?

Mr. Fatzer: Unfortunately, your Honors, we did not

have attached to this the map of the Board of Education which

designated the particular districts of the City School System.

Justice Frankfurter: Could you supplement that later?

10

Mr. Fatzer: Yes, v/e would bo glad to.

Justice Reed. Could you also supplement that by showing

the percentage of actual white children in the districts?

Mr. Fatzer: I think that is set forth here in the

figures of the Superintendent of Public Instruction and

approved by the Board.

This shows roughly, your Honors, an estimation of—

on the assumption of one-third of the children attending the

strictly colored schools, Washington, Momroe and the Buchanan

%

Schools,who would be given the choice to attend the schools

which they attended last year, those three schools, or to go

into the new district in which they might reside and attend

the formerly all-white schools— one-third of the colored chil

dren will attend the school ax which they attended last year or

this present term.

Bear in mind this is effective in September of this

coming term.

There is another provision in this resolution of

the Topeka Board of Education and that is with respect to

kindergarten children, that those children entering kindergarten

:ln 1955-1956, September of this coming year, this coming

September, those who are affeetod by the change in the

school district boundaries as recommended, be given the option

of attending the same school in 1955-1956 that they would have

attended in 1954-1955 had they been opened up then.

11

It, has been reported to the Attorney General's

office that the purpose of this clause is that if a parent

v/ho had a child that v/ould enter kindergarten this year formerly

lived in a segregated district and as a result of the change

of school district boundaries, a result of this policy, the

parent can send his child to the school he v/ould have attended

last year or this current term if he had been old enough or

he can always send him to the school in the district in v/hich

he re3ides0

It has been suggested to us that the purpose of

that is to permit any parent to move from the area where he lives

to some other area in the City.

Justice Reed; Have you indicated the number of each

in each of these districts, the number of v/hite and colored

children?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes, if you have it, your Honor—

Justice Reed: I have it.

Mr. Fatzer: On page 2 it shows approximately the

number of students changing from the four colored schools

to the non-segregated schools.

Justice Reed: Those I suppose are the integrated

schools?

Mr. Fatzer: That is correct. I used the term "non-

integrated schools” as of the date of this order.

Justice Reed: It does not show the schools— under

12

paragraph 4, it does not show the number of white and colored

in different grades?

Mr. Fatser: Well, if Your Honors will go down to the

last four schools listed in Paragraph 4-— Buchanan, Monroe,

McKinley and Washington, you will note the estimated total of

attendance this year is considerably lower than the actual

attendance on this present school term. Whereas, the reverse

is true of the other schools affected.

Justice Clark: What was the attendance this past

session, this present system?

Mr. Fatzer: In the whole school system?

Justice Clark: No, the last three schools?

Mr. Fatser: Buchanan, 110; Monroe, 181. No, I

beg your pardon. Buchan 136; Monroe, 256.

Justice Clark: That is these figures here, I see.

I thought that was the next year.

Mr. Fatzer: No, this is the actual, 10-15-54, Mr.

Justice Clark, turn to the right-hand side of the page.

Justice Clark. Yes, I see. Thank you.

Justice Reed: Are your opponents here? Are they

going to argue?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes, they are.

Justice Harlan: Could I ask you a question?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes, sir.

Justice Harlan: Is the difference between those

13

tv/o columns, for example, the difference between 1 10 and 136

in the case of Buchanan, is that a result of your redistricting?

Mr. Fatzer: That is the estimated result of

redistricting.

Justice Harlan: Without regard to the possible

exercise of the option that you referred to?

Mr. Fatzer: Well, that is taken into consideration

on this estimate on the basis that one-third of the children

attending Washington, Monroe, Buchanan , will remain. Tv/o-

tbirds of them will go to 3 o m e other school.

Justice Reed. Are all the schools under 4, are they

colored, or only the last three?

Mr* Fatzer: The last 4 are, Buchanan, Monroe,

McKinley and Washington.

Justice Reed: That is my understanding, but I

still do not understand how many colored pupils are estimated

to be in grammar school next year*

Mr* Fatzer: 53, your Honor, at the top of page 2.

Justice Reed: 58. That is the estimate for next year?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes, sir* Now, I am not quite sure

that that takes into consideration, and it probably does not,

the 123 students that have been integrated on Steps 1 and 2.

This i3 an estimate of Step 3 to complete the program.

We believ?, your Honors, that thU Board has c a l l e d

with the Court’s decision in good faith. That it has done

14

everything it could aa expediently and aa rapidly aa posalble.

It ha3 taken approximately a year and five months of this

vj tiling Board to meet it a administrative program and problems*

to provide for teacher assignments* student assignments.. The

administrative Intent of compliance has been declared. .And

vie believe* your Honors* that the rule of Eccles vs. Peoples Bank

in 333 U.S. 426 Is applicable* that where the administrative

Intention Is expressed but has not yet come to fruition* vje

have held that the controversy is not ripe for equitable inter

vention. We believe that the cause should be remanded but that

this Board be permitted to carry out its orderly process of

integration.

Now perhaps the Court might he interested in the

other cities that are not affected by the decree in this case*

governing solely the Topeka Board of Education. I shall

briefly cover them.

In the first place* as I told the Court* this decision

has received no adverse reaction from the people of

our state. For instance* the City of Atchison* on the Missouri

River* approximately 3,0*000 people* with about 10 per cent

Negro population. On September 1 2 * 1953 the B0ard of Education

adopted a resolution terminating segregation in Grades 7

/

through 12* and so as to complete the plan* segregation is to

be terminated In grades 1 through 6 as soon a3 practicable.

In Lawrence* the seat of the University* approximately

15

24,000 population, with about 70 per cent of Negro population,

they have maintained segregated schools since 1369. That city

and that Board of Education has terminated segregation in its

system.

In Leavenworth, a city of approximately 20,000,

there is a population, Negro population of about 10 per cent.

The system was established, the segregated system was estab

lished In 1853 and has been maintained constantly since that

time. They have adopted resolutions In that Board, In that

city, and the first positive 3tep was taken in the

current year in which children of kindergarten and first-grade

pupils were to be admitted to the schools nearest their

residence and presumably in the ensuing school term it will

be extended to Grades 2, 3 and perhaps higher.

I should like just briefly, your Honors, to quote

from a report from one of the school authorities in Leavenworth

with respect to the time that, in his Judgment, they require

to complete their voluntary program, because I think. In the

first place, this man i3 one of the leading public school

educators in Kansas, he ha3 started the movement In Leavenworth

to comply with the Court's decision and I would like,Just

briefly, to read part of his report to our office:

"In my Judgment, the solution will have to be

carefully and slowly Introduced. You and I and most Board

members will readily agree to the righteousness of the complete

16

integration from the standpoint of our established principles

of decency* Christianity ang democracy. However* there is

a sufficient number of biased and prejudiced persons who villi

merce life miserable for those in authority who attempt to

move in that direction too rapidly. As a consequence* many of

us will be accused of 'dragging our feet* in the matter* not

because of our personal feelings or inclinations* but

because* in dealing with the public, its general approval

and acceptance is indispensable. One cannot force it. He

can only coax and nurture it along."

In Kansas City* Kansas* with a population of

approximately 130*000 persons* about 20 .6 per cent are members

of the Negro population. I should point out that this city has

a greater per cent of Negro population than 3ome southern

cities* such as Dallas* Louisville* SL. Louis* Miami* Oklahoma

City* and only slightly les3 than in Baltimore.

Up to the px-esent school term* including the present

school term— excuse me--up to the present school term the

City has maintained seven elementary schools* one Junior

high school and one high school *'or its approximately 6,000

Negro students* while it had 22 schools which were attended

by more than 23>000 white 3tudent3 .

Ju3t briefly* the Board of Education of that city

has adopted thi3 resolution which provides substance to begin

integration in all public schools at ihe opening of school on

17

September 13,. 195*1; second* to complete the Integration as

rapidly aa claaa apace can bo provided; to accomplish the

transition from segregation to Integration in a natural

and orderly manner designed*to protect the interest of all

the pupils and insure the support of the community* and

they seek to avoid disruption of professional life of career

teachers.

So that city* although no limit is set* they

are proceeding in good faith and with dispatch to end

segregation.

Parsons* a city of 15-000* located in the southern

part of the state* has less than 10 per cent of Negro population*

and they have announced their policy to end segregation*

effective last term with respect to all schools except one

school* due to it3 crowded condition and the fact that there was

a lack of adequate facilities and it required new buildings*

and when those are completed* there will be complete Integration

in that system.

In Coffeyville* a city on the State Line* the

Southern State Line* approximately 60*000 to 70-000 people*

approximately ip per cent colored population* they adopted

resolutions terminating segregation at the end of the school

year.

Only one city that we have not heard from* Fort

Scott. We have reports that in that city the only protest

13

against the proposed segregation was from Negro citizens.

I am sure that we shall have no difficulty with that city. We,

therefore, suggest to this Court that the case he reversed,

that it he remanded to the District Court and that the Board

of Education be permitted and allowed, without the interference

of any dec**ee, to carry out the program in good faith, subject

to any objections that any person might have with respect to its

completeness or with respect to its application, and that, at

that time, notice be given by the Court to Counsel,at which

time those matters may be dealt with by the lower court.

Justice Frankfurter: May I ask whether, in

Kansas, you have a cent'oallzed authority over the local school

boards or are they autonomous?

Mr. Fatzer: They are autonomous. They are

elected by the people. They are .financed by the people locally,

except with respect to state aid, but it is not conditioned

upon local action. It is conditioned upon daily, average daily

attendance.

/

Justice Frankfurter: And on the law enforcement side,

doe3 the Attorney General of Kansas,assuming that there is

a statewide law or an order of thi3 court, is the authority of

enforcement vested over localities in the Attorney General?

Mr, Fatzer: With respect to state law3, I think

that i3 correct, sir. I am doubtful if we would have any

dut;y ico enforce the decrees of this Court.

19

Justice Frankfurter: Who would? In a particular

case you have Topeka, Suppose this Court enters a decree*

assume we follow your suggestion of remanding the particularities

to the appropriate district court of the United States and

a decree Is then entered* binding against the School Board of

Topeka--! think it would be* would it not?

Mr. Fatzer: That i3 correct* the timbers of the

Board.

Justice Frankfurter: --what would the enforcing

authority* the Federal authority--has the Attorney General

of Kansas any responsibility In that regard?

Mr, Fatzer: In this case* when the three-Judge

court was convened* the statute was complied with wSth respect

to notice to the Governor and the Attorney General of the State.

It would be my Judgment* Mr. Justice* that the great

inherent power of the Federal District Court* that

It can enforce its own decrees.

Justice Reed: Mr. Attorney General*do you have

in Kanasa at present a law which permits segregation?

Mr. Fatzer: We do not now* no* sir. We have con

sidered it to be declared invalid by decision of this Court.

Justice Reed. That Is you have Interpreted the

decision as invalidating your law?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes* sir* we have.

Justice Reed: Therefore* you feel no obligation to

20

enforce the State law?

Mr. Fatzer: We feel any statute

Justice Reed. You have no obligation to enforce

that state law ?

Justice Frankfurter: What were the sanctions of

that state law., Mr. Attorney General, in connection with Mr.

Justice Reed’s question— what wa3 the nature of that law?

Mr. Fatzer: Purely permissive.

Justice Frankfurter: Just authorizes local school

boards to introduce it?

Mr. Fatzer: They could introduce it or reject it,

which some of them did. One city in the state never even used

it. Two cities in the state previously, which had segregation

previously terminated on their own volition. It is a purely

permissive. It was a purely permissive statute. We consider it

without force and effect at this time.

Justice Frankfurter: And you are in this litigation

by virtue of the requirement of notice to the Governor and the

Attorney General under the three-Judge court statute?

Mr. Fatzer: That 13 correct, your Honor. We felt that

this system was apparently being maintained under authority of

thi3 Court, under authority of our Supreme Court, and other

appellate courts. We felt that we owed a duty to uphold the

decisions of our 3tate courts with respect to this state

statute and that is why we were here originally. And we are

21

here novj not as an adversary hut to assist the Court in

any way we can in helping it arrive at a correct decree if

any need be entered locally.

Justice Douglas: How many students are involved

here in the Tope lea case?

Mr, Fatzer: 32 00., I think, your Honor, was

the figure.

Justice Douglas: I moan in this litigation.

Mr. Fatzer: The whole school system was involved.

Justice Douglas. In Topeka?

Mr. Fatzer: My recollection i3 that there were

336 Negroes, 7,4l3 white children for a total of 8,254

children altogether, 336 colored children 7,4lS white children,

or a total of 3,254.

Justice Douglas: These appellants in No. 1 you

say, you do not know whether they have all been taken into the

schools that they sought to enter?

Mr. Fatzer: I can not tell you that, sir, I assume

they have. I do not know.I am sure that counsel for the

Appellant can advise the Court on that, I do not know.

Justice Douglas: I suppose, if they were just

an application by one Negro student to enter the school that

was closest to hi3 home which happened to be a white school,

and he was admitted, that that case would hecome moot then?

22

Mr. Fatzer: I assume* sir* that there are more

children involved* all the children of the City School

system are Involved* in my judgment.

Justice Clark: Under the plan in Topeka* there

will be no segregation* enforced segregation after when?

Mr. Fatzer: Commencing September* 1955* 3ir.

Justice Clark: That is this next September?

Mr. Fatzer: That is this next school term.

Justice Clark: There will be no enforced segregation?

Mr. Fatzer: No enforced segregation.

Justice Clark: Now skipping over to the City of

.Kansas City* what is the schedule there? I understood you to say

they did riot; have a definite schedule* is that correct?

MR. Fatzer: Well* if I said that* I did not want

to leave that Impression* Mr.Justice Clark.

Justice Clark: I may have misunderstood you.

Mr. Fatzer: I shall read with some care here the

resolution of this Board adopted August 2.

Justice Clark: Where is it? I can read that if you

want to go ahead.

Mr. Fatzer: It is on page 20 of the

Supplemental brief of the State of Kansas as to questions 4 and 5

propounded by the Court.

Justice Reed. Going back to page 2 of what you

filed here on April 11 on the schools* I may be stupid about it*

Contents

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF BOARD OF EDUCATION P a g e

Topeka, Kansas

By Mr. Harold R. Fatzer 4

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF OLIVER BROWN, ET AL

By Mr. Robert L. Carter 26

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF FRANCIS B. GE ESI ART, ET AL

By Mr. J.D. Craven 3S

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, ET AL

By Mr. Louis L.Reading 46

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF SPOTTSWOOD BOLLING, ET AL

By Mr. George Hayes and Mr. James Nabrit 53

70

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF C. MELVIN SHARPE ET AL

By Mr. Milton Korman 83

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF HARRY BRIGGS, JR. AND

DOROTHY DAVIS, ET AL

By Mr. Robinson 102

1

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

APRIL TERM, IS55

G(dstein

Cantor Fuff

ALFRED BROWN, MRS. RICHARD LAWTON, ET AL

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION, TOPEKA, KANSAS, Et AL

FRANCIS B, GERHART ET AL,

vs.

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, ET AL,

SPOTTSWOOD THOMAS BOLLING, ET AL,

vs.

Co MELVIN SHARPE, ET AL,

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., ET AL

vs.

R. W. ELLIOTT, ET AL

DOROTHY E, DAVIS, ET AL

VS.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL.

Washington, D.C,

April 11, 1955

2

The above-entitled matter came on for oral argument

at 12 noon.

PRESENT:

The Chief Justice, Earl Warren and Associate

Justices Black, Reed, Frankfurter, Douglas,

Jackson, Burton, Clark and Minton,

APPEARANCES:

On behalf of the Board of Education of

Topeka, Kansas:

Harold R. Fatzer, Attorney General of Kansas.

On behalf of Oliver Brown, Et Al:

Robert L. Carter.

On behalf of Francis B. Gebhart, Et Al

Joseph Donald Craven, Attorney General of

Delaware.

On behalf of Ethel Louise Belton, Et Al

Louis L. Reading.

On behalf of Spott3wood Thomas Bolling Et Al:

George E.C. Hayes and James M. Nabrit, Jr.

On Behalf of C. Melvin Sharpe, Et Al:

Milton D, Korman.

On Behalf of Harry Briggs, Et AL

Thurgood Marshall,Spottswood W. Robinson, II;

On Behalf of R. W. Elliott, Et.

Robert LlcC Figg> jr. , and S.E. Rogers.

3

APPEARANCES - continued.

On Behalf of County School Board of

Prince Edward County, Virginia, Et Al:

Archibald G. Robertson, and

Lindsay Almond, Jr., Attorney General of Virginia.

4

Goldstein

Cantor

Ruff

The Chief Justice* No. 1 on the Calendar, Alfred

Brown, Mrs. Richard Lawton, et al, vs. Board of Education of

Topeka, Kansas, et al.

The Clerk, Counsel are present, sir.

The Chief Justice; Attorney General Fatzer.

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF BOARD OF EDUCATION

By Mr. Fatzer.

Mr, Fatzer; Chief Justice and Members of the Supreme

Court: I am Harold R, Fatzer, the Attorney General of Kansas

and with me today is Mr. Paul E. Wilson, the First Assistant

Attorney General who has previously argued the State’s position

when the question of the answer to Questions 1 , 2 and 3 .

v;aa argued heretofore.

Today, we appear not as an adversary. We appear

hereeto be of assistance if we can to the Court in helping

it see that proper decrees are imposed and made.

Now in answer directly to the questions, your

Honors, of Nos. 4 and 5 and the subsequent subsections, we

want to say that traditionally in Kansas, segregation has

not been a policy of that state, on a 3 tate level. We suspect

that the Kansas case io probably the least complex of any

that is before it. We wish to say that that ha3 never been

a matter of state policy. We believe that the decision of

the Court has been received by the students, teachers, school

administrators and by the parents of both colored and white

5

with approval.

In answering and assisting this Court, I shall be

very brief in stating our position, what we believe should be

done with respect to the case that is now before the Court,

that is, the Topeka Board of Education.

Your Honors, we believe that 4-A should be answered

in the negative. We do not believe that the immediate aud

forthwith admission of the Plaintiffs— although they may be

in the school; I am not prepared to tell the Court that they

are not, I suspect that they are— would, and as the Board of

Education found, work a hardship, would impair administrative

procedures, and so we would suggest to the Court that no decree

be entered which would forthwith admit any student to the

school of his choice. Rather, v/e believe that the Court

should exercise its equitable jurisdiction at all times in

these cases because of the public interest involved, notwith

standing the fact that the Plaintiffs in the case would

undoubtedly have some present and immediate right and personal

right of admission to the schools.

We believe, your Honors— 'and I want to make a brief

report of a situation that has developed since the brief in

the Kansas case v/a3 filed— we believe that this case should be

reversed, that it should be remanded to the Federal District

Court in Kansas. I should like to tell you and briefly review

the efforts of the Topeka Foard of Education to terminate

6

segregation in the public schools in that city.

It was commenced on September 3, 1953. The

policy announced by the School Board was to terminate maintenance

of segregation in elementary schools as rapidly as was practica

ble. Five days following that date,to wit* September 8 , 1953,

segregation wa3 terminated in two schools in the city. It

Involved only approximately ten colored children, but they were

living in the district. They were permitted to attend those

schools.

Justice Burton. You referred to the termination of

segregation in the elementary schools?

Mr, Fatzer, That is correct.

Justice Burtont Has it been terminated in

the other schools?

Mr. Fatzer. There i3 none in Grades 1 to 6, Mr.

Justice.

That was called the first step. The second step was

made on January 20, 1954. And that was effective for the school

term, current school term, 1954-1955.

At that time, and by order of the Board o? Education,

segregation was terminated in twelve school districts in the

city and transportation was not provided to the Negro school

children living in those twelve districts on the basis that

the child could attend the school of that district but with

the privilege, if he preferrsd,to attend the colored school

7

which he had been attending. This affected appro2:iaately 113

children, plus the ten that had been previously affected from

Step 2— 123 Negro children were placed in the integrated school.

Justice Frankfurter. What is the total of school

population into which these 123 wore merged, roughly?

Mr. Father: I will have to refer —

Justice Frankfurter: What magnitude? Was it 10,000,

or 50,000?

Mr. Father: No, nothing of that kind. I think

perhaps the school population in Topeka is roughly 8200, Mr.

Justice.

Justice Frankfurter: So there v/as no problem of

space and buildings, and none of those problems?

Mr. Father: In one school there was. One school

in which, in the so-called Polk School there was the space

problem and I think three children were admitted to that

school and others were not because of this space problem.

Justice Frankfurter: And there v/as no re-districting

of the districts you have?

Mr. Fatzer: Not at that time.

Now I spoke to your Honors of a subsequent event

that occurred subsequent to the filing of the State’s brief

here in response to the request of the Court, which occurred

on February 23, 1055, We have with us today the minutes of

the Topeka Board of Education adopted February 23, 1955, which

8

we have filed in the Clerk’s office as a supplement to the

brief filed in this Court in response to questions 4 and 5

propounded by the Court. We file it simply for informational

purposes to show the good faith of the members of the Board

of Education of Topeka in carrying out the previous announced

policy of terminating segregation as rapidly as practicable.

Now this third step, your Honors, is effective

September, 1955. It provides, (1) that segregation has been

terminated in all remaining buildings; (2) That the McKinley

Elementary School, one of the colored schools, be closed and

that it be placed on a standby basis for the coming year; (3 )

That colored schools, Buchanan School, Monroe and Washington

Schools be assigned districts within the areas of the city, the

same as any other school area in the city and that any child

who is affected by the change in the school district— I will

go ahead— any child who is affected by the change in school

district lines as recommended on a map which we did not attach

hereto, be given the option of finishing the elementary grades

in the school in which he attended in 1954 and 1955.. That is,

he could attend the school in the district in which he resided

or, if the new district overlaps now into a district that

for erly existed before the re-districting, he can attend

the school that he attended last year. In other words, it is

equally available to both the white and the colored students.

Justice Frankfurter: Have I missed a statement as

9

to the basis or the reasons for which this re-districting was

I

done?

Mr. Fatzer: The basis of it was done, of course, Your

Honor, on the Court’s decision of May, 1954, to comply with the

order of this Court that segregation, per se, was unconstitu

tional. That is the basis of it.

Justice Frankfurter: You mean there were exclusively

Negro schools?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes.

Justice Frankfurter: And those were withdrav/n from

use by the City?

Mr. Fatzer: One was, your Honor.

Justice Frankfurter: One was. And the others are

now available to children, intermixed, is that it?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes.

Justice Frankfurter: Was that districting a geo

graphic districting?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes.

Justice Frankfurter: Was there any indication in the

minutes of the Board or in any document you filed as to the

compact geographic nature of this districting?

Mr. Fatzer: Unfortunately, your Honors, we did not

have attached to this the map of the Board of Education which

designated the particular districts of the City School System.

Justice Frankfurter: Could you supplement that later?

10

Mr. Fatzer: Yes, v/e would be glad to.

Justice Reed. Could you also supplement that by showing

the percentage of actual white children in the districts?

Mr. Fatzer: I think that is set forth here in the

figures of the Superintendent, of Public Instruction and

approved by the Board.

This shows roughly, your Honors, an estimation of—

on the assumption of one-third of the children attending the

strictly colored schools, Washington, Monr*oe and the Buchanan

Schools,who would be given the choice to attend the schools

which they attended last year, those three schools, or to go

into the new district in which they might reside and attend

the formerly all-white schools— one-third of the colored chil

dren will attend the school ax which they attended last year or

this present term.

Bear in mind this is effective in September of this

coming term.

There is another provision in this resolution of

the Topeka Board of Education and that is with respect to

kindergarten children, that those children entering kindergarten

in 1955-1956, September of this coming year, this coming

September, those who are affeetod by the change in the

school district boundaries as recommended, be given the option

of attending the same school in 1955-1956 that they would have

attended in 1954-1955 had they been opened up then,

11

It, has been reported to the Attorney General’s

office that the purpose of this clause is that if a parent

who had a child that v/ould enter kindergarten this year formerly

lived in a segregated district and as a result of the change

of school district boundaries, a result of this policy, the

parent can send his child to the school he would have attended

last year or this current terra if he had been old enough or

he can always send him to the school in the district in which

he resides.

It has been suggested to us that the purpose of

that is to permit any parent to move from the area where he lives

to some other area in the City.

Justice Reed; Have you indicated the number of each

in each of these districts, the number of white and colored

children?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes, if you have it, your Honor—

Justice Reed: I have it.

Mr. Fatzer: On page 2 it shows approximately the

number of students changing from the four colored schools

to the non-segregated schools.

Justice Reed: Those 1 sixppose are the integrated

schools?

Mr. Fatzer: That is correct. I used the term "noa-

integrated schools” as of the date of this order.

Justice Reed: It does not show the schools— under

12

paragraph 4, it does not show the number of white and colored

in different grades?

Mr. Fatzer: Well, if Your Honors will go down to the

last four schools listed in Paragraph 4— Buchanan, Monroe,

McKinley and Washington, you will note the estimated total of

attendance this year is considerably lower than the actual

attendance on thi3 present school term. Whereas, the reverse

is true of the other schools affected.

Justice Clark: What was the attendance thi3 past

session, this present system?

Mr. Fatzer: In the whole school system?

Justice Clark: No, the last three schools?

Mr. Fatzer: Buchanan, 110; Monroe, 181. No, I

beg your pardon. Buchan 136; Monroe, 256.

Justice Clark: That is these figures here, I see.

I thought that was the next year.

Mr. Fatzer: No, this is the actual, 10-15-54, Mr.

Justice Clark, turn to the right-hand side of the page.

Justice Clark. Yes, I see. Thank you.

Justice Reed: Are your opponents here? Are they

going to argue?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes, they are.

Justice Harlan: Could 1 ask you a question?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes, sir.

Justice Harlan: Is the difference between those

13

tv/o columns, for example, the difference between 1 10 and 136

in the case of Buchanan, is that a result of your redistricting?

Mr. Fatzer: That is the estimated result of

redistricting.

Justice Harlan: Without regard to the possible

exercise of the option that you referred to?

Mr, ratzer. Well, that is falcon into consideration

on thi3 estimate on the basis that one-third of the children

attending Washington, Monroe, Buchanan , will remain. Tv/o-

thirds of them will go to 3ome other school.

Justice Reed. Are all the schools under 4, are they

colored, or only the last three?

Mr* Fatzer: The last 4 are, Buchanan, Monroe,

McKinley and Washington*

Justice Reed: That is my understanding, but I

still do not understand how many colored pupils are estimated

to be in grammar school next year*

Mr, Fatzer: 53, your Honor, at the top of page 2.

Justice Reed: 58. That is the estimate for next year?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes, 3 ir. Now, I am not Quite sure

that that takes into consideration, and it probably does not,

the 123 students that have been integrated on Steps 1 and 2.

This is an estimate of Step 3 to complete the program.

We believ?, your Honors, that this: Board has complied

with the Court's decision in good faith* That it has done

14

everything it could aa expediently and aa rapidly aa poaaible.

It ha3 taken approximately a year and five months of this

willing Board to meet ita adminiatrative program and problems,

to provide for teacher aasignmenta, 3tudent assignments., The

administrative intent of compliance has been declared. .And

we believe, your Honors, that the rule of Ecclea va. Peoples Bank

in 333 U.S. 426 is applicable, that where the administrative

Intention ia expressed but haa not yet come to fruition, we

have held that the controversy is not ripe for equitable inter

vention. We believe that the cause should be remanded but that

this Board be permitted to carry out its orderly process of

integration.

Now perhaps the Court might he interested in the

other cities that are not affected by the decree in this case,

governing solely the Topeka Board of Education. I shall

briefly cover them.

In the first place, as I told the Court, this decision

has received no adverse reaction from the people of

our state. For instance, the City of Atchison, on the Missouri

River, approximately 3,0,000 people, with about 10 per cent

Negro population. On September 1 2 , 1953 the B0ard of Education

adopted a resolution terminating segregation in Grades 7

/

through 12, and so as to complete the plan, segregation Is to

be terminated in grades 1 through 6 as soon as practicable.

In Lawrence, the seat of the University, approximately

15

24,000 population, with about 70 per cent of Negro population,

they have maintained segregated schools since 1369, That city

and that Board of Education has terminated segregation In its

system.

In Leavenworth, a city of approximately 20,000,

there 13 a population, Negro population of about 10 per cent.

The system was established, the segregated system was estab

lished in 1353 and has been maintained constantly since that

time. They have adopted resolutions In that Board, in that

city, and the first positive 3tep was taken in the

current year in which children of kindergarten and first-grade

pupils were to be admitted to the schools nearest their

residence and presumably in the ensuing school term it will

be extended to Grades 2, 3 and perhaps higher,

I should like just briefly, your Honors, to quote

from a report from one of the school authorities in Leavenworth

with respect to the time that. In hi3 Judgment, they require

to complete their voluntary program, because I think. In the

first place, this man is one of the leading public school

educators in Kansas, he ha3 started the movement in Leavenworth

to comply with the Court’s decision and I would like,ju3t

briefly, to read part of his report to our office:

"In my Judgment, the solution will have to be

carefully and slowly introduced. You and I and most Board

members will readily agree to the righteousness of the complete

16

integration from the standpoint of our established principles

of decency,. Christianity an£ democracy. However, there is

a sufficient number of biased and prejudiced persons who will

matce life miserable for those in authority who attempt to

move in that direction too rapidly. As a consequence, many of

us will be accused of 'dragging our feet' in the matter, not

because of our personal feelings or inclinations, but

because, in dealing with the public, its general approval

and acceptance is indispensable. One cannot force it. He

can only coax and nurture it along."

in Kansas City, Kansas, with a population of

approximately 130,000 persons, about 2 0 .6 per cent are members

of the Negro population, I should point out that this city has

a greater per cent of Negro population than 3ome southern

cities, such as Dallas, Louisville, St. Loui3, Miami, Oklahoma

City, and only slightly less than in Baltimore.

Up to the px-esent school term, including the present

school term-excuse me--up to the present school term the

City has maintained seven elementary schools, one Junior

high school aud one high school *or its approximately 6,000

Negro students, while it had 22 schools which were attended

by more than 23.. 000 white 3tudent3 .

Ju3t briefly, the Board of Education of that city

has adopted thi3 resolution which provides substance to begin

integration in all public schools at the opening of school on

17

September 13., 195*1; seconds to complete the integration as

rapidly aa claa3 apace can he provided; to accomplish the

transition from segregation to integration in a natural

and orderly manner designed.,to protect the interest of all

the pupils and insure the support of the community* and

they seek to avoid disruption of professional life of career

teachers.

So that city* although no limit i3 set* they

are proceeding in good faith and with dispatch to end

segregation.

Parsons* a city of 15.*000* located in the southern

part of the state* has less than 10 per cent of Negro population*

and they have announced their policy to end segregation*

effective last term with respect to all schools except one

school* due to its crowded condition and the fact that there was

a lack of adequate facilities and it required new buildings*

and when those ax’© completed* there will be complete integration

in that system.

In Coffeyville* a city on the State Line* the

Southern State Line* approximately 60*000 to 70*000 people*

approximately ip pen* cent colored population* they adopted

resolutions terminating segregation at the end of the school

year.

Only one city that we have not heard from* Fort

Scott. We have reports that in that city the only protest

13

against the proposed segregation was from Negro citizens«

I am sure that vje shall have no difficulty with that city. We,

therefore, suggest to this Court that the case he reversed,

that it he remanded to the District Court and that the Board

of Education be permitted and allowed, without the Interference

of any decree, to carry out the program in good faith, subject

to any objections that any person might have with respect to its

completeness or with respect to its application, and that, at

that time, notice be given by the Court to Counsel,at which

time those matters may be dealt with by the lower court.

Justice Frankfurter: May I ask whether, in

Kansas, you have a cent-eallzed authority over the local school

boards or are they autonomous?

Mr, Fatzer: They are autonomous. They are

elected by the people. They are financed by the people locally,

except with respect to state aid, but it is not conditioned

upon local action. It is conditioned upon daily, average daily

attendance.

Justice Frankfurter: And on the law enforcement side,

doe3 the Attorney General of Kansas,assuming that there Is

a statewide law or an order of this court, is the authority of

enforcement vested over localities In the Attorney General?

Mr. Fatzer: With respect to state law3, I think

that is correct, sir, X am doubtful If we would have any

duty to enforce the decrees ox" tnis Court.

19

Justice Frankfurter: Who would? In a particular

case you have Topeka. Suppose this Court enters a decree*

assume we follow your suggestion of remanding the particularities

to the appropriate district court of the United States and

a decree is then entered,, binding against the School Board of

Topeka--I think it would be., would it not?

Mr. Fatzer: That 13 correct, the iPmbera of the

Board.

Justice Frankfurter: — what would the enforcing

authority, the Federal authority--ha3 the Attorney General

of Kansas any responsibility in that regard?

Mr. Fatzer: In this case, when the three-Judge

court was convened, the statute was complied witn with respect

to notice to the Governor and the Attorney General of the State.

It would be my Judgment, Mr. Justice, that the groat

Inherent power of the Federal District Court, that

it can enforce Its own decrees.

Justice Reed: Mr. Attorney General,do you have

in Kanasa at present a law which permits segregation?

Mr. Fatzer: We do not new, no, sir. We have con

sidered it to be declared invalid by decision of this Court.

Justice Reed. That Is you have Interpreted the

decision as invalidating your law?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes, air, we have.

Justice Reed: Therefore, you feel no obligation to

20

enforce the State lavj?

Justice Reed. You have no obligation to enforce

that state law?

Justice Frankfurter: What were the sanctions of

that state law., Mr, Attorney General, in connection with Mr.

Justice Reed's question— what was the nature of that law?

Mr. Fatzer: Purely permissive.

Justice Frankfurter: Just authorizes local school

boards to introduce it?

Mr. Fatzer: They could introduce it or reject it,

which some of them did. One city in the 3tate never even used

it. Two cities in the state previously, which had segregation

previously terminated on their own volition. It is a purely

permissive. It was a purely permissive statute. We consider it

without force and effect at this time.

Justice Frankfurter: And you are in this litigation

by virtue of the requirement of notice to the Governor and the

Attorney General under the three-Judge court statute?

Mr. Fatzer: That 13 correct, your Honor. We felt that

this system was apparently being maintained under authority of

thi3 Court, under authority of our Supreme Court, and other

appellate courts. We felt that we owed a duty to uphold the

decisions of our state courts with respect to this state

statute and that is why we were here originally. And we are

Mr. Fatzer: We feel any statute —

21

here now not ag an adversary but to asslot the Court in

any way we can in helping it arrive at a correct decree if

any need be entered locally.

Justice Douglas: How many students are involved

here in the Topeka case?

Mr. Fatzer: 8200., I think., your Honor., was

the figure.

Justice Douglas: I mean in this litigation,

Mr. Fatzer: The whole school system was involved.

Justice Douglas. In Topeka?

Mr. Fatzer: My recollection is that there were

836 Negroes., 7,4l3 white children for a total of 3^254

children altogether* 836 colored children 7,4l3 white children.,

or a total of 3*254.

Justice Douglas: These appellants in No. 1 you

say., you do not know whether they have all been taken Into the

schools that they sought to enter?

Mr. Fatzer: I can not tel*, you that., 3ir, I assume

they have. I do not know.I am sure that counsel for the

Appellant can advise the Court on that, I do not know.

Justice Douglas: I suppose.. If they were just

an application by one Negro student to enter the school that

was closest to his home which happened to he a white school.,

and he was admitted., that that case would hecome moot then?

22

children involved* all the children of the City School

system are involved* in my judgment.

Justice Clark: Under the plan in Topeka* there

will be no segregation* enforced segregation after when?

Mr. Fatzer: Commencing September* 1955* 3ir.

Justice Clark: That is this next September?

Mr. Fatzer: That is this next school term.

Justice Clark: There will be no enforced segregation?

Mr. Fatzer: No enforced segregation.

Justice Clark: Now skipping over to the City of

Kansas City* what is the schedule there? I understood you to say

they did not have a definite schedule* is that correct?

MR. Fatzer: Well* if I said that* I did not want

to leave that impression* Mr.Justice Clark.

Justice Clark: I may have misunderstood you.

Mr. Fatzer: I shall read with some care here the

resolution of this Board adopted August 2.

Justice Clark: Where i3 it? I can read that if you

want to go ahead.

Mr. Fatzer: It is on page 20 of the

Supplemental brief of the State of Kansas as to questions 4 and 5

propounded by the Court.

Justice Reed. Going back to page 2 of what you

filed here on April 11 on the schools* I may be stupid about it*

Mr. Fatzer: I assume* sir* that there are more

23

but in the fourth section., that refers only to Negroes.

Mr/Fatzer: That is Item No. 4.,"The following is

the estimate of the number of students in 19 5 5 -19 5 6 that

would be in the affected schools."

Justice Reed: Does that mean Negroes* too?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes.

' Justice Reed: You don't know the percentage of

Negro students in each school?

Mr. Fatzer: No* I am in error* your Honor. That i3

total enrollment.

Justice Reed: I understood you had a total

enrollment of 3oroe 3*000?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes* that is correct.

Justice Reed: Then there is only 2750 accounted

for here.

Mr. Fatzer: We would be glad* your Honor* to provide

this breakdown with respect to these schools* with respect to

whether they are white or colox^ed in each grade.

Justice Reed: It would help me.

Mr. Fatzer: All right. In other words —

Justice Reed: You have rediotricted and what I was

interested in is to know whether the redistricting has

resulted in essential--whether all the school population will be

unsegregated* or whether you will have all of the schools in one

section all colored population.

2H

the areas that are predominantly through history., geographic

residential colored areas.

Justice Reed: Very normal that there Is a separation

of population.

Mr. Fatzer: Mow on the fringe, some of the colored

students under thi3 plan would go to the white schools, the

white children that are in the new areas, new districts, could

likewise complete their course. They can attend either school.

It is a privilege that is given to either child.

Justice Reed: And we do not know how long that

will continue, strictly speaking?

Mr. Fatzer: Well, from now on. I mean, segregation.

Justice Reed: The plan oould result in not a

segregated school, hut an all-white school and an all-Negro

school?

Mr. Fatzer: It Is my understanding, sir, that

that would not be the case. Now for the children, if you will

note under No. 2-D, any child who i3 affected by the change In

district lines a3 herein recommended, be given the option of

finishing elementary grades. That would be, if he was in the

first grade, he could finish the elementary grades 1 to 6 in

the school which he attended this current year. Now that

Is equally available to both the colored and the white students.

Justice Reed: I understand that, but It is also

Mr. Fatzer: The colored schools are In the

25

equally available that all the Negroes could go to one

□chool and all the whites to another.

Mr. Patzer: I am not prepared to say on that, sir,

but my understanding is that that would not be the case.

Ue will be glad to furnish the Court maps showing this area

and we would be glad to show a breakdown under No. 4, Mr.

Justice Reed, of the per cent and the number of the

different white and colored students.

Justice Frankfurter: I would be grateful to you

if you would add to that what is not fully clear in my mind and

I do not want to take the Court's and your time— if you would

he good enough to state why there had to be, in the judgment

of the School Board, redistricting and the basis on

which the redlstrlctlng was done.

Is my question clear?

Mr. Fatzer: Why redlstrlctlng—

Justice Frankfurter: Why was it necessary, in

order to carry out the desegregation, the abolition of

segregation, why wa3 it necessary to have new cr changed

school districts and what were the considerations which led

to the kind of districts that they carried out?

Mr. Fatzer: It Is rry understanding, Mr. Justice,

that the reasons they required the rodiatricting of the

schools, as this proposal would establish, is that

colored schools did not have a district previously, chan xu,

26

in a general large way., that children living in thia particular

part of the city would attend thia particular achool.

Juatice Frankfurter: They Just took them by bua to

achoola aet aside for colored children?

Mr, Fatzer: That ia right.

Juatice Frankfurter: I see.

Mr, Fatzer: They gathered them up. So that now

they have definite proposed diatricte for each of the3e

achool3 with definite geographic lines.

Juatice Frankfurter: And your map3 will show the

nature of the districts., the contours of the districts., will

they not?

Mr, Fatzer: That ia correct.

Thank you, your Honors, very much.

The Chief Justice: Mr. Carter?

ORAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF BROWN, ET AL

By Mr, Robert L. Carter

Mr. Carter: We are in accord with Mr. Fatzer that

the case should be reversed and remanded to the District

Court, We feel that the decree should be entered by this

court declaring the Kansas statute by which power the

Topeka Board proceeded to organize and have segregated schools,

that that statute be declared unconstitutional and void.

Justice Frankfurter: I understood that the

Attorney General had already expressed an opinion to that

27

effect.

Mr. Carter: He had expressed an opinion.

Justice Frankfurter: I am not saying what you said

should not be done* but he has already announced that this

Court’s decision on May 17 of last year invalidated

that statute. Is that a correct understanding?

Mr. Carter: Yea, sir. That is invalidated, that

invalidated the statute but, as far as Topea is concerned,

any power to organize and segregate a school must emanate

from a specific statute or else,under the state law,there is

no power to maintain segregation. Therefore, the Invalidation

of this statute means there is no power at all in Kansas to

maintain and operate segregated schools as the law has been

Interpreted by the State Courts of Kansas.

Justice Reed: That was involved in the suit

you brought here?

Mr. Carter: Yea, sir.

Justice Reed: What do you mean, you want a specific

Invalidation of this specific statute?

Mr. Carter: We think, your Honors, that such

a decree ought to be entered, declaring the statute unconstitu

tional because as of now the implications are that the statute

is unconstitutional by the May 17th decision, but the May 17th

decision has no specific declaration or Judgment or decree.

And In the reversal, we think this should be set forth In

28

your reversal and remanding to the lower court.

Justice Feed: If we had aald that in the opinion,

then it would not bo necessary in the decree, or would it?

Mr. Carter: I think It would in terms of the

decree. It scem3 to me that 13 the thing that the lower

court gets and acts upon rather than the opinion of the court,

Justice Reed: If a decree Is reversing the decision

of the court below to allow all children, a complete Integratlon-

I do not just understand, yourpoint.

Mr. Carter: We think that‘the May 17th decision

In effect means that the Kansas statute which was here in this

case is void. What we are asking for Is specifically a

decree, reversing and specifically saying the statute is uncon

stitutional and has no force and effect.

Justice Frankfurter: You would rather go to the

decree, rather than the opinion?

Mr. Carter: Yes.

Justice Frankfurter: Because the decree Is the

thing that counts:

Mr. Carter: Y es. Secondly, we would like a

decree that would indicate that an order to the Topela

Board to cease and desist at once from basing school attendance

and admission on the basis of race so that as of September,

1955 no child in Topeka would be going to school on the basis

of race or color. We would think that an instruction should lie

29

issued to the District Court to hold Jurisdiction and hold

proceedings to satisfy itself that the school board of Topeka

as of September, 1955, has a plan which satisfies these

requirements in that the school system has been reorganized

to the extent that there is no question of race or color

involved in the school attendance in its rules.

We also think that the School should hold Jurisdic

tion, the District Court should hold Jurisdiction to issue

whatever other orders the Court desires.

We feel that everything that Mr. Fatzer has said

augurs for a forthwith decree in this case .

The plan which has been issued as che third step,

is not one that indicates that there are any reasons why

desegregation should not be obtained as of September, 1955.

The plan says that desegregation will obtain as of September,

1955. We take objection to the plan. We think there are a

number of Governors in the plan which will mean there will be

a modified form of segregation being maintained for many /ears

as the plan now operates, but we do not think that this is

the place for U3 to argue about the question of the plan.

We think that this court issues a decree as we have

suggested to the lower court with the school board and the

attorneys for the appellants can argue as to whether or not

a specific plan which is being adopted by the Board

30

conforms with the requirements of thi3 court's opinion and

Its decree, that segregation bo ended as of September, 1955,

'which we think should be done.

Justice Frankfurter. As of September. Can you

tell specifically when the classes are formed In the Topeka

schools? Wien is the makeup of the classes affected in

thia litigation? When, in September, the first of September,

or— do you happen to know about that? The point of my question

is as to the time rhen this must be determined if it is

to affect the entering classes in September, when it is

that the district court will have to hear these things?

Mr. Carters I do not have that information. I

know that one of the resolutions, the school opens September 15,

I think thl3 year. I do not know when they open in 1955.

Justice Frankfurter: The Attoi’ney General will be

able to tell U3 then?

Mr Carter: I would think that we would of course

want to have a hearing before the District Court at as early

a date as possible so that this matter could be settled and

there wOild be no question but that the question in Topeka

would he going to unsegregate schools on a plan which conforms

to the court's decree in all its requirementr

as of September, 1955. With that we would be satisfied.

Justice Clark: Are the appellants segregated at

thia time?

31

Mr. Carter: Yea* air. There are five who are in

the junior high school who have moved out of thia claaa

because they are not in a non-segregated school. About

six of them are attending Washington, Buchanan, and- Monroe

schools which are the segregated schools.

Justice Harlan: Is that the result of expulsion,

or their own choice?

Mr. Carter: Well, your Honor, as a result of

expulsion, this plan, what is known as the third step— there

were IS school districts In Topeka. The first six schools

listed on page 2 of the Order, the papers which the

Attorney General gave you, those schools are the remaining

six schools In which segregation still obtains, the all-white

schools. The lower four schools are the all-Negro schools.

In all of the other districts, that is approximately

12, Negro and white children are attending schools together,

that is the Negro children are able to go to the schools that

are nearest to their homes.

This third step purports to complete the Integration

of the system and to bring Into the system the three Negro

schools and make It a part of the total school system. Now

instead of 18 schools, you will have 2 1 schools purportedly

servicing every one. Our objection to thia Is the fact that in

our opinion these three schools will remain segregated, all

Negro children will be attending them for many years to come and

32

we think that doe3 not conform to your order.

Justice Douglas: Are those Buchanan, Monroe and

Washington?

Mr. Carter: Ye3, sir.

Justice Cl irk: Will that be on a voluntary basis,

you think?

Mr. Carter: No, that will not be on a voluntary

basis because the Negro children who now live in the District,

as this thing i3 reorganised in the district serviced,for

example, by Buchanan, as you will note, the children in

this district have an option to go to a school outside of the

District, but since the Negro children only had the option

or the right before this thing was put into effect, to go

to Buchanan, Monroe and Washington,they can not exercise an

option to go to any other school than the Negro school. That

means this, that the white children will go out of the district

and continue to go to the schools they are going to and the

Negro children will he forced to continue in Buchanan,

therefore you will have segregated schools.

I think that is a3 much segregation as before the

May 17th order.

Justice Harlan: Do you attribute that result to the

way the option system may work rather than the way the

district is made up?

Hr. Carter: Yes, sir. I know nothing about the

33

district. I cannot say whether the districting is done fairly,

I do not know anything about the matter. But on the face of

It, this is nry objection to the plan as it is given to us by

the Attorney general.

Justice Clark: I thought all the students would

be given a choice as to whether they want to stay there or

go to another school under Section 3- page 1, the bottom of the

page. It does not 3ay all, but it says the estimated number of

students who will transfer is indicated as one-third.

Mr. Carter: I know. Justice Clark, but if you

will look on page 1, Item D on the third step, this is the

option, that "Any child who is affected by change in the

district lines as herein recommended, be given the option of

finishing elementary grades in the school which he attended

1954-1955 and continue therein."

This is the option to be exercised and this is the

option where the Negro child has no option and the white

child in the District that is serviced by one of the former

Negro schools, has an option to go out of the district and

the Negro child has not.

The Chief Justice: Thank you, Mr. Carter.

Mr. Attorney General, can you tell us when the

schools open in Topeka?

Mr. Fatzer; My understanding Is, sir, that it

commences on the second Monday in September and that the

3*

enrollment of students is generally completed during a

three-day period just about,, just before the second Monday

In September.

The Chief Justice: The determining as to where

a child shall go Is not made until In September?

Mr. Fatzer: I think that Is true. I assume that

it villi be worked out under this plan. If the lower court

would approve it or if it were to be modified by that date*

surely the schools authorities want to know how many children

are going to be In some school and whether facilities are going

to be adequate and whether or not, under the program and the

plan as proposed or as may be modified, that what children

are going, whether they are eligible under the plan to go to this

school and whether existing facilities are available to take

care of them.

The Chief Justice: I think generally what thi3 Court

would be Interested in knowing would be In the event there 13

a remand to the District Court, if It might be said when

it get3 there, that It wag too late for next year.

Mr. Fatzer: No.

The Chief Justice: That it should have beer, there

before some date, say. In July or August when those

things are done.

Mr. Fatzer: I am sure that would not be the case,

your Honors. I can tell this Court that I am pretty certain.

35

Justice Reed: From what you say* I take it that

you consider it proper to allow an option to a child to go to

another school* that is within the limits of the Constitution?

Mr. Fatzer: Bearing in mind* sir* that our under

standing at present —

Justice Reed: Before you answer that* may I make

another statement. I understand that normally a child in Topeka

goes to the school in the school district in which he resides?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes* sir.

Justice Reed: Now* there i3 a variation from

that which allows him to go to another school if he

has been going there before. That is the 2-E section?

Mr. Fatzer: Yes. He can complete his elementary

course in the other school, if he should be in another

district.

Justice Reed: A child who goes to school for the

first time* for the first year* in the first grade* may he

choose a school to which he goes?

Mr. Fatzer: The first year only.

Justice Reed: And after having chosen the first year*

then he continues there?

Mr. Fatzer: He must attend in the district in

which he resides under Plan 2~E.

Justice Reed: If he attends in 1955-1956* you

interpret that to mean only for 1 9 5 5-19 5 6* for that year?

30

Mr. Fatzcr: That la the interpretation placed upon

It by the attorney for the Board of Education to our office*

yes*sir* that they only attend there one year.

If* in the area of the Monroe school* some

child by geographic area would be within that boundary and

within another district prior to this redistricting and

could have attended last year if they had been old enough* they

could attend the so-called white school for the one-year

period on the basis that it would permit time for the parents

to move if they so desired.

I am told that very frankly that is the purpose of

the section.