Lytle v. Household Manufacturing Inc. Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lytle v. Household Manufacturing Inc. Brief for Appellant, 1986. 773af822-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f144ffa8-32f0-4dc9-873b-82f9f23d436c/lytle-v-household-manufacturing-inc-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

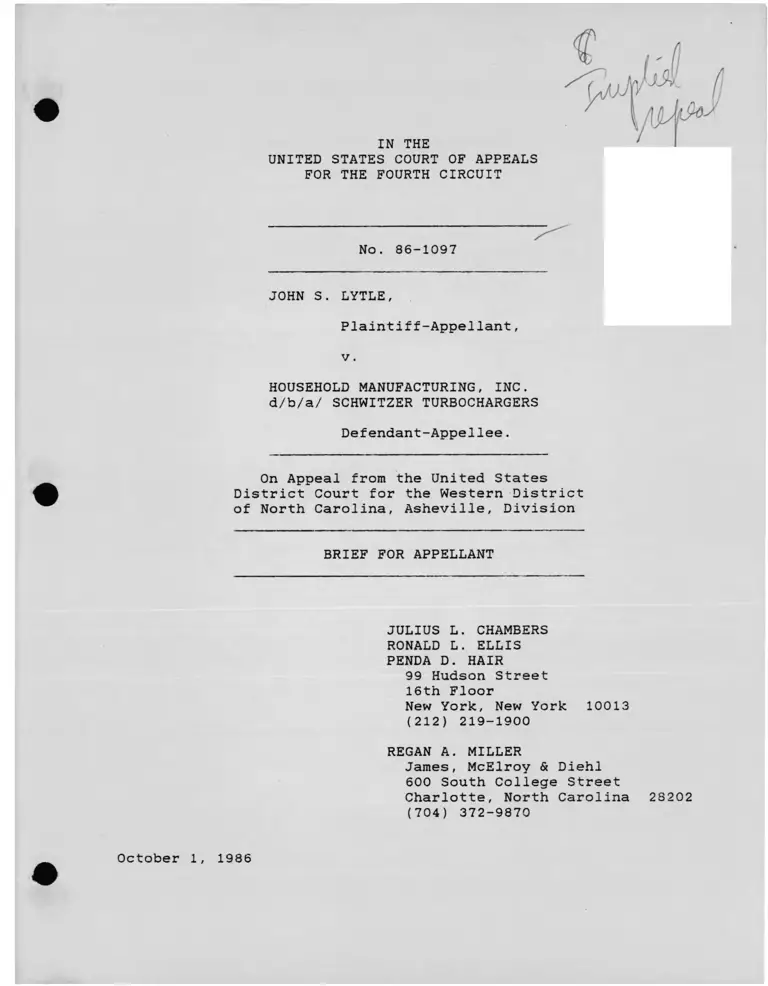

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 86-1097

JOHN S. LYTLE,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v .

HOUSEHOLD MANUFACTURING, INC.

d/b/a/ SCHWITZER TURBOCHARGERS

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Western District

of North Carolina, Asheville, Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

RONALD L. ELLIS

PENDA D. HAIR

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

REGAN A. MILLER

James, McElroy & Diehl

600 South College Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 2S202

(704) 372-9870

October 1, 1986

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities m

QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 1

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS 2

A. Discriminatory Discharge 2

1. Plaintiff's Work History 3

2. Plaintiff's Termination 4

3. Schwitzer's Absence Policy 8

4. Schwitzer's Treatment of White Employees 9

B. Retaliation Claim 11

C. The Decision Below 12

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 14

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRONEOUSLY DISMISSED PLAINTIFF'S

CLAIM UNDER 42 U.S.C. SECTION 1981 AND

UNCONSTITUTIONALLY DEPRIVED PLAINTIFF OF HIS RIGHT TO A JURY TRIAL 17

A. TITLE VII DOES NOT PREEMPT CLAIMS UNDER 42

U.S.C. SECTION 1981 17

B. TITLE VII AND SECTION 1981 CLAIMS MAY BE

BROUGHT IN THE SAME LAWSUIT 23

C. PLAINTIFF'S RETALIATION CLAIM IS ACTIONABLE

UNDER 42 U.S.C. SECTION 1981 31

D. PLAINTIFF IS CONSTITUTIONALLY ENTITLED TO A

JURY TRIAL ON HIS SECTION 1981 CLAIMS 32

II. THE TRIAL COURT'S JUDGMENT ON PLAINTIFF'S TITLE VII CLAIMS MUST BE VACATED 37

38

III. PLAINTIFF ESTABLISHED A PRIMA FACIE CASE

OF DISCRIMINATORY DISCHARGE UNDER TITLE VII

A. PLAINTIFF ESTABLISHED A PRIMA FACIE CASE

UNDER THE SUPREME COURT'S MODEL OF PROOF OF

INDIVIDUAL DISCRIMINATORY TREATMENT 38

B. PLAINTIFF ESTABLISHED A PRIMA FACIE CASE

UNDER MOORE V. CITY OF CHARLOTTE 39

C. PLAINTIFF ESTABLISHED A PRIMA FACIE CASE OF

DISCRIMINATION IN THE CLASSIFICATION OF HIS

ABSENCES AS UNEXCUSED 44

CONCLUSION

ADDENDUM — Relevant Statutes

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

CASES

Acosta v. Univ. of District of Columbia, 528 F.Supp.

1215 (D. D.C. 1981) ................................ 27

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, 415 U.S. 36 (1974) ...... ...15,21,24

Barfield v. A.R.C. Security, Inc., 10 FEP Cases 789

(N.D. Ga. 1975) ................................... 32

Beacon Theatres v. Westover, 359 U.S. 500 (1959) ..... . .14,16,37

Bell v. New Jersey, 461 U.S. 773 (1983) ............... 22

Bibbs v. Jim Lynch Cadillac, Inc., 653 F.2d 316 (8th

Cir. 1981) ........................................ 26

Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574

(1983) ............................................ 22

Boykin v. Georgia-Pacific Corp., 706 F .2d 1384

(5th Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 465 U.S.

1006 (1984) .......................................

Brady v. Thurston Motor Lines, 726 F.2d 136 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied, 84 L .Ed. 2d 53 (1984), subseauent

decision on remedy, 753 F .2d 1269 (4th Cir. 1985) 26

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d

1377, 1382 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 409

U.S. 982 (1972) ................................... 42

Brown v. GSA, 425 U.S. 820 (1976) ..................... ..20,28,29

Burrus v. United Tel. Co., 683 F .2d 339 (10th Cir.),

cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1071 (1982) ............... 42

Burt v. Abel, 585 F.2d 613 (4th Cir. 1978) ...........

Carpenter v. Stephen F. Austin State University, 706

F .2d 608 (5th Cir. 1983) .........................

33

27

ill

27

Choudhury v. Polytechnic Institute of New York, 735

F . 2d 38 (2d Cir. 1984) ............................... 32

Claiborne v. Illinois Central Railroad, 583 F.2d 143

(5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 442 U.S. 934

(1979) ................................................ 26,28

Continental Casualty Co. v. DHL Services, 752 F .2d 353

(1985) 35

Cox v. Consolidated Rail Corp., 557 F .Supp. 1261 (D.

D.C. 1983) ....................... TCt-t ............... 32

Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189 (1974) ................... 33

Dairy Queen v. Wood, 369 U.S. 469 (1962) ................. 37

Daniels v. Lord & Taylor, 542 F .Supp. 68 (N.D. 111.

1982) 27

DeMatteis v. Eastman Kodak Co., 511 F.2d 306 (2d Cir.),

modified on other grounds, 520 F.2d 409 (1975) 32

E.E.O.C. v. Gaddis, 733 F.2d 1373 (10th Cir. 1984) ...... 26

Electrical Workers v. Robbins & Myers, Inc., 429 U.S.

229 (1976) 21

Ellis v. International Plavtex, Inc., 745 F.2d 292

(4th Cir. 1984) 35

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976) ....... 25

Furnco Construction Co. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567 (1978) ... 43

Gairola v. Virginia Dept, of General Services, 753

F . 2d 1281 (4th Cir. 1985) 35

Gates v. I.T.T. Continental Baking, 581 F .Supp. 204

(N.D. Ohio 1984) 26,37

General Building Contractors v. Pennsylvania, 458 U.S.

375 (1982) 18,19,25

Goff v. Continental Oil Co., 678 F.2d 593 (5th Cir.

1982) 31,32

Goss v. Revlon Inc., 548 F.2d 405 (2d Cir. 1976) ........ 21

IV

32

Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 22 FEP Cases 680

S.D.N.Y. 1978) ..................................

Great American S. & L. Ass'n v. Novotny, 442 U.S. 366

(1979) 29

Greenwood v. Ross, 778 F.2d 448 (8th Cir. 1985) ......... 32

Gresham v. Waffle House, Inc. 586 F .Supp. 1442 (N.D.

Ga. 1984) 32

Griggs v. Duke Power, 401 U.S. 424 (1971) 19

Hall v. Pennsylvania State Police, 570 F .2d 86 (3d

Cir. 1978) 13

Hamilton v. Rodgers, 791 F . 2d 439 (5th Cir. 19.8 ) ....... 28

Harris v. Richards Mfg. Co., 675 F.2d 811 (6th Cir.

1982) 21,26,32,33

Hudson v. 22 FEP Cases 947 (S.D.N.Y. 1975),

aff1d , 620 F.2d 351 (2d Cir.), cert, denied,

449 U.S. 1066 (1980) 32

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency Inc., 421 U.S. 454

1975) ................................... 18,19,20,26,29,30,33

Johnson v. Ryder Truck Lines, Inc., 575 F .2d 471 (4th

Cir. 1978), cert. denied, 440 U.S. 479 (1979) ...15,19,20,30

Jones v. Western Geophysical Co., 761 F.2d 1158 (5th

Cir. 1985) 26,28

Lanphear v. Prokop, 703 F.2d 1311, (D.C. Cir. 1983) 42

London v. Coopers & Lybrand, 644 F.2d 811 (9th Cir.

1981) 32

Lowe v. City of Monrovia, 775 F.2d 998 (9th Cir.

1985) 21,26

Mahone v. Waddle, 564 F.2d 1018 (3d Cir. 1977), cert.

denied, 438 U.S. 904 (1978) 18

Marable v. H. Walker & Associates, 644 F.2d 390 (5th

Cir. 1981) 13

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co., 427 U.S. 273

(1976) 25

v

McDonnell Douglas Corn. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) ...38,39,40

Moffett v. Gene B. Glick Co., 621 F.Supp. 244 (N.D.

Ind. 1985) ........................................... 32

Moore v. City of Charlotte, 754 F.2d at 1100 (4th

Cir.), cert, denied, 105 S.Ct. 3489 (1985) ..... 17,39,40,42

Moore v. Sun Oil Co. of Pennsylvania, 636 F.2d 154

(6th Cir. 1980) 33,37

New York City Transit Authority v. Beazer, 440 U.S. 568

(1979) 25

O'Brien v. Sky Chefs, Inc., 670 F.2d 864 (9th Cir. 1982) 42

Owens v. Rush, 654 F.2d 1370 (1981) ...................... 30

Page v. U.S. Industries, Inc. 726 F.2d 1038 (5th Cir.

1984 ) 27,28

Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Corporation,

727 F .2d 473 (5th Cir. 1984), cert, denied, 104

S.Ct. 3516 (1984) 26

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., subsequent decision,

535 F.2d 257, cert. denied, 429 U.S. 920, subsequent

decision, 634 F .2d 744 (1980), rev 1d on other

grounds, 456 U.S. 63 (1982) 42

Paxton v. United National Bank, 688 F.2d 552, 563 n. 15

(8th Cir. 1982), cert, denied, 460 U.S. 1083 (1983) 42

Pinkard v. Pullman-Standard, 678 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir.

1982) ................................................. 32

Poolaw v. City of Anadarko, 738 F.2d 364 (10th Cir.

1984), cert, denied, 84 L . Ed 2d 779 (1985) ......... 26

Powell v. Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency, 563

F.Supp. 419 (M.D. Penn. 1983) 27

Rivera v. City of Wichita Falls, 665 F.2d 531 (5th

Cir. 1982) 27,28

Rowe v. Cleveland Pneumatic Corp., 690 F.2d 88

(6th Cir. 1982) 42

vi

42

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348, 357-58

(5th Clr. 1972) ......................................

Runyan v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976) ...................

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097 (5th

Cir. 1970), cert■denied, 401 U.S. 948 (1971) ....... 21,

Segara v. McDade, 706 F.2d 1301 (4th Clr. 1983) .........

Setser v. Novack Investment Co., 638 F.2d 1137 (8th

Cir.), modified, 657 F.2d 932, cert.denied,

102 S.Ct. 615 (1981) ................................31,32,

Sisco v. J.S. Alberici Const. Co., 655 F.2d 146 (8th

Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 976 (1982) ......

Smith v. Western Elec. Co., 770 F.2d 520 (5th Cir.

1985) 27,

Stearns v. Beckman Instruments, Inc.,.737 F.2 1565

(Fed. Cir. 1984) .....................................

Tafoya v. Adams, 612 F.Supp. 1097 (D.C.

Colo 1985) 23,24,27,28,29,30,

Takeall v. WERD, Inc., 23 FEP Cases 947 (M.D. Fla.

1979) ...... ..........................................

Texas Department of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450

U.S. 248 (1981) ......................................

Thomas v. Resort Health Related Facility, 539 F.Supp.

630 (E.D.N.Y. 1982) 27,

Thornburg v. Gingles, 54 U.S.L.W. 4877 (June 30, 1986) ...

Waters v. Wisconsin Steelworks, 427 F .2d 476 (7th

Cir.), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 911 (1970) ............

Webb v. Kroger Co., 620 F.Supp. 1489 (S.D. W.Va. 1985) ...

Whiting v. Jackson State University, 616 F.2d 116 (5th

Cir. 1980) .................................... 26,27,28,32,

Williams v. Owens-Illinois, Inc., 665 F.2d 918 (9th

Cir. 1982), modified on other ground, 28 FEP

Cases 1820, cert.denied, 459 U.S. 971 (1982) ....... 26,

vii

18

22

33

33

32

28

35

31

32

38

38

22

21

45

39

33

Winston v. Lear-Siegler, 558 F.2d 1266 (6th Cir.

1977) 32

Wilson v. United States, 645 F .2d 728 (9th Cir. 1981) .... 35

Wright v. Olin Corp., 697 F.2d 1172, 1181

(4th Cir. 1982) 42

Young v. International Telephone and Telegraph Co.,

438 F. 2d 757 ( 1971) .................................. 18,22

Zuben v. Allen, 396 U.S. 168 (1969) ...................... 22

Constitution and Statutes

U.S. Constitution, Thirteenth Amendment ................... 18

U.S. Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment ................... 18

28 U.S.C. §1291 ... ....................................... 2

42 U.S.C. §1981 Passim

42 U.S.C. §1985(c) 29

42 U.S.C. §2000e et seg.................................... Passim

Legislative Authorities

110 Cong. Rec. (1964) 21,25

118 Cong. Rec. ( 1972) 23,25

H. R. Rep. No. 238, 92d Cong. 1st Sess. (1971) 19,22-25

S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong. 1st Sess. (1971) .............. 22

Other Authorities

Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 8(c)(2) 15,26

Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 41(b) 14,34

Moore's Federal Practice (1985) 35

B. Schlei & P. Grossman, Employment Discrimination Law ...

viii

33

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether independent causes of action under 42 U.S.C. §

1981 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that are based

on the same set of facts may be joined in the same lawsuit?

2. Whether the constitutional right to a jury trial

applies when legal claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 are joined with

equitable claims under Title VII?

3. Whether plaintiff established a prima facie case of

discriminatory termination under Title VII?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

John S. Lytle filed this action on December 6, 1984, seeking

relief under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§2000e et seq., and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C.

§1981. JA 5. Lytle alleged that his employer, Schwitzer

Turbochargers (a subsidiary of defendant, Household

Manufacturing, Inc.), discharged him because of his race and

retaliated against him for filing a charge of discrimination with

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. JA 5-8.

On December 26, 1984, plaintiff amended his Complaint to

allege that he had suffered such special damages as

embarrassment, damage to his reputation, emotional distress and

mental suffering as a result of the discriminatory and

retaliatory acts of defendant. JA 10. Plaintiff was allowed to

file a supplemental Complaint on November 27, 1985, which

contained the requisite allegations to provide the court with

jurisdiction over the retaliation claim under Title VII. JA 24.

Plaintiff requested a jury trial on his claims under Section

1981. JA 8.

On April 19, 1985, defendant moved for summary judgment on

several grounds, including that plaintiff's claim of

discriminatory discharge was barred by the doctrine of collateral

estoppel. (Pleading No. 11). On May 17, 1985, the District

Court denied the motion on the ground that "there is a genuine

issue as to material facts." JA 23.

On February 26, 1986, the Court dismissed plaintiff's claims

under 42 U.S.C. §1981, and denied plaintiff's request for a jury

trial. TR 2-10. Plaintiff's Title VII claims were tried to the

District Court on February 26-27, 1986. At the close of

plaintiff's case, the Court made findings of fact, and granted a

motion under Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 41(b) to dismiss the claim of

discriminatory discharge. TR 258-59. At the close of all of the

evidence, the Court, after making findings of fact and

conclusions of law, ruled for defendant on the retaliation claim.

The Court entered a judgment in favor of defendant on all claims

on March 12, 1986. TR 300-01.

Plaintiff filed a timely notice of appeal on April 11, 1986.

JA 63. This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §1291.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

A. DISCRIMINATORY DISCHARGE

This case involves the firing of a black employee for

2

alleged unexcused absences on two days. Plaintiff, supported by

his doctor, claimed that he was ill and that his absence should

have been classified as excused in accordance with defendant's

absence policy. Plaintiff also showed that white employees with

"excessive absence" in violation of defendant's policy were not

fired.

1. Plaintiff's Work History

John Lytle, a black person, first applied for a job as a

machine operator at the Arden, North Carolina, plant of Schwitzer

Turbochargers on February 29, 1980. TR 80. Schwitzer is engaged

in the business of manufacturing turbochargers and fan drives. TR

13.

At the time he applied with Schwitzer, Lytle had about 20

years experience operating the kinds of machines used by

Schwitzer. TR 84. Nonetheless, after an initial interview, he

received no response to his application. TR 81. When he

contacted Schwitzer's Human Resources Counselor, Judith Boone,

Lytle was told that his application had been "misplaced on the

floor." TR 82. Then, rather than consider Lytle for a machinist

job, Boone told him that "there would be a chance for [him] to be

hired" if he attended an unpaid training course. TR 83. It was

not until January 15, 1981, after Lytle had completed this

training course, in which many of the trainees had never operated

a machine, that he was hired by Schwitzer into the lower level

position of machinist trainee. TR 83-84, 87. Less experienced

3

whites were hired directly into machine operator positions, TR

82-83.

During Lytle's employment at Schwitzer, his immediate

supervisor was Larry Miller, the Production Superintendent was A1

Duquenne, the Employee Relations Manager was Lane Simpson and the

Human Resources Counselor was Judith Boone, all of whom were

white. (Defendant's Answer to Plaintiff's First Request for

Admissions, ££> 1-4). In 1983, only seven of Schwitzer's 148

employees were black. TR 14.

Lytle slowly progressed into higher paying jobs and finally

achieved the highest graded machinist classification. TR 87-89.

In his 1982 performance evaluation, Lytle was commended for his

good attendance record. TR 86; PX 6. He was never reprimanded

or disciplined for attendence problems. TR 86-87.

2. Plaintiff's Termination

In February, 1983, Lytle began taking courses in mechanical

engineering at Asheville-Biltmore Technical College. TR 91.

These courses were taken "to better my job performance" and

"qualify for some of the better jobs at Schwitzer." Id. Lytle

was encouraged by his supervisors at Schwitzer to undertake this

educational program and, in fact, Schwitzer provided tuition

reimbursement. TR 92-93.

Lytle enrolled in a program which required that he attend

classes at least four evenings a week. TR 95. Since his shift

at Schwitzer normally ended at 3:30 p.m., these evening classes

4

did not conflict with his work schedule. TR 90-92. On class

days, Lytle left work at 3:30 p.m., arrived home about 4:00 p.m.,

had something to eat, arrived at the college library to study at

4:30 or 5:00 p.m., and attended class from 6:30 p.m. until

between 9:00 and 11:00 p.m. TR 92. He also frequently found it

necessary to study in the late evening and early morning hours.

TR 120.

By Summer, 1983, Lytle had begun to suffer health problems

as a result of this arduous schedule. He complained to the plant

nurse that he was dizzy, run down and possibly suffering from

high blood pressure. TR 71-72, 121. The nurse recommended that

he consult a doctor. Id. In June or July, Lytle also informed

his supervisor, Larry Miller, of these health problems and stated

that for this reason he preferred not to work overtime. TR 120.

At the beginning of August, 1983, Lytle cut back his school

program to two evenings per week. TR 95. During the first week

of August, Schwitzer machinists were called upon to work a

substantial amount of overtime in order to keep up with

production requirements. TR 238. Lytle worked a total of five

hours of overtime during that week. TR 127.

The next week, Lytle's health problems became worse and on

one occasion he became so dizzy that he fainted. TR 132. He

scheduled an appointment for Friday, August 12, 1983, with a

doctor who had been recommended by the Schwitzer nurse. TR 122,

130-131. On Thursday morning, August 11, Lytle asked his

5

supervisor, Miller, for permission to schedule Friday, August 12,

as a vacation day. TR 129-132. Although sick leave would have

been granted for a doctor's appointment, Lytle preferred to have

the absence treated as a vacation day. TR 194. Such treatment

meant that the day would not be counted as an absence under

Schwitzer's policy regarding "excessive absence." TR 208.

Treating absences because of illness as vacation days was a

common practice among Schwitzer's employees. TR 208.

Miller at first informed Lytle that there was no problem

with a vacation day on Friday the 12th. TR 130. However, later

in the day, Miller stated to Lytle: "if you're off Friday, you

have to work Saturday." TR 131. Saturday was not a normal work

day for Lytle, but Miller stated that Lytle was required to work

overtime on Saturday. TR 132. Lytle "explained that I wanted

Friday off to see the doctor, and I wouldn't be able to work

Saturday because I was physically unfit." TR 131-32. Miller

still insisted that Lytle work on Saturday, at which point Lytle

stated that if it were required, he would also take Saturday as a

vacation day. TR 132. Miller walked off, without objecting to

this suggestion. TR 132. Lytle understood that Friday would be

treated as a vacation day, and that he had sufficiently informed

Miller that he was physically unable to work on Saturday. TR

191.

About an hour later, Miller's assistant came to Lytle's work

station with a message that Lytle had received an emergency

6

TR 133.telephone call. TR 133. Lytle went to the employee's pay

telephone and tried to call home. TR 134. When he could not get

through, Lytle went to the nearest company telephone to call the

switchboard operator. He intended to inquire whether his wife

had stated the nature of the emergency. TR 135.1

While Lytle was talking with the switchboard operator,

supervisor Miller entered the room. TR 135-36. Lytle

immediately hung up the telephone and went out into the hallway

where Miller was waiting. TR 136. Miller then "jumped all over"

Lytle. TR 136. Miller kept repeating that Lytle could not use

the company telephone or leave his job station without

permission. TR 13 6. Lytle "tried to explain to him what I was

doing on the phone, but he wouldn't listen." TR 136. Because he

found it impossible to reason with Miller, Lytle "walked off and

went back to work." TR 136.

As Lytle was getting ready to go home, Miller "threw ... in

[Lytle's] tool box" a schedule of overtime for the following

week. TR 136-37. Miller again did not indicate that he had

disapproved Lytle's request to take Friday and Saturday as

vacation days. TR 137.

On Friday, August 12, Lytle kept his appointment with

Dr. Caldwell. TR 139. Dr. Caldwell testified at the trial as an

expert in internal medicine. TR 198. Dr. Caldwell diagnosed 1

1Lytle later found out that his child had suffered a medical

emergency while at school. TR 138-39.

7

Lytle as suffering from fatigue and depression. He recommended

that Lytle reduce his activities "in regard to ... work and/or

school" and that he get more rest. TR 200. He also felt that

Lytle was under too much stress and "that an impending major

illness might follow." Id. Dr. Caldwell concluded that Lytle

was ill on the day that he was examined, and he would have given

Lytle an excuse for not working the next day. TR 201, 203.

Except for three hours in Dr. Caldwell's office, Lytle

stayed at home and rested on Friday and Saturday, August 12-13.

TR 140-41.

On Monday, August 15, Lytle returned to work as usual. TR

141. During the day he was called into the office of Mr. A1

Duquenne, the plant manager. TR 142. Duquenne questioned him

about his absence on Friday and Saturday. Id. Lytle stated that

he had been granted permission to take a vacation day for the

Friday doctor's appointment. Id. Lytle also informed Duquenne

that he had discussed with Miller the fact that he was physically

unable to work on Saturday. TR 145. Later in the day, Lytle was

informed that he had been terminated. Id.

3. Schwitzer's Absence Policy

In February, 1982, Schwitzer adopted an Absence Policy which

outlined "the procedure to be used by our employees to schedule

or report necessary absences, tardiness or leaving early." px

22, p. 1. Pursuant to this policy, an employee was to report all

anticipated absences to his or her supervisor "as soon as

8

possible in advance of the time lost, but not later than the end

of the shift on the previous workday." Id.

This Policy provided that absences would be excused for

urgent personal business, urgent family obligation and personal

illness. PX 22, p. 2. The policy also provided that "excessive"

absence "will, most likely, result in termination of employment."

PX 22, p. 3. It defined "Excessive Absence" as either "a total

absence level which exceed[s] 4% of the total available working

hours, including overtime" or "any unexcused absence which

exceeds a total of 8 hours (or one scheduled work shift) within

the preceding 12-month period." PX 22, pp 2-3.

4. Schwitzer's Treatment of White Employees

Plaintiff introduced evidence from defendant's own records

of white employees who were not terminated despite "excessive

absence." Several white employees had excessive excused

absences. In January, 1983, Donald Rancourt, a white machinist,

TR 217-18, • received a written warning from Larry Miller

concerning an absence rate of 7.5%. TR 222, 23 0. In April,

1983, Rancourt's annual performance review noted that his absence

rate as of the week ending March 20, 1983 was 5.6%. TR 48; PX

15-C, page 4. Rancourt was not terminated. TR 54.

As of March 2, 1984, Jeffrey C. Gregory, a white machinist,

had an annual absence level of 6.3% of total available working

hours. TR 57-58; PX 28-B. He was not terminated. TR 58. It is

not clear whether he was even counselled concerning his excessive

9

absenteeism. TR 58.

On July 13, 1983, approximately one month prior to

Schwitzer's termination of Lytle, Rick Farnham, a white machine

operator, was counselled for excessive absenteeism. TR 55-56; PX

12- B. At that time Farnham's annual absence rate was 4.3%. TR

56; PX 12-B.. Farnham was not terminated.

On August 23, 1982, David Calloway, a white machinist, was

given his second warning in three months about excessive

absenteeism. In June, 1982, his absence percentage was 4.5% and

he was warned that "an immediate improvement must be made." PX

13- B, p. 1. In August, his absence percentage remained at 4.5%.

He had been absent for a total of 16.2 hours since the June

warning, and two absences were on consecutive Mondays. TR 44.

Instead of termination, Calloway was given an additional sixty

days in which to correct the problem. PX 13-B.

In addition, Greg Wilson, a white machinist, was absent two

successive days without obtaining prior approval. TR 23-24. Of

the sixteen hours of absence, eight were categorized as

unexcused. The second day's absence was "excused" because Wilson

called to inform his supervisor that he was ill. This two-day

absence followed three unexcused tardies. Thus, as of March,

1983, Mr. Wilson had accumulated excessive unexcused absences.

TR 67. Yet, Wilson was not fired, but merely counselled to

improve his absence record. The record of employee counselling,

dated March 3, 1983 states:

10

"On 3-2-83, Greg was absent from

work for 8 hours without calling

in, and was unexcused for this

reason. Greg has had 3 previous

unexcused absences for tardiness,

for which he was verbally warned.

... Greg has exceeded the unexcused

absence limit defined in our

Absence Policy and will be

terminated if further unexcused

absence occurs within the next 12-

month period."

PX 14B. (Emphasis added).

B . RETALIATION CLAIM

On August 23, 1983, Lytle filed a charge of discrimination

with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. TR 61; PX 1.

This charge was received by Schwitzer's Human Resources

Counselor, Judith Boone, shortly thereafter. TR 61-62. Around

the same time, Lytle began seeking employment with other

businesses in the Asheville area without success. He was

informed by some of these prospective employers that they were

having difficulty getting an adequate reference from his former

employer, Schwitzer. TR 111.

Mr. Adrienne Finch interviewed Lytle for a position at ABF

Freight Systems. TR 100. Judith Boone, Schwitzer's Human

Resources Counselor, received an employment reference tracer for

Lytle from ABF headquarters. Although the form stated that

applicants could not be hired unless the questionnaire was

completed, Boone refused to answer the questions or return the

form. In a telephone interview, she provided only job title,

date of hire, and date of termination. TR 65-67.

11

Lytle was also informed by Steve Yates, Personnel Director

of Thomas and Howard, that he was not able to obtain sufficient

information from Schwitzer in order to determine whether or not

to hire Lytle. TR 111. Judith Boone refused to provide any

information to Thomas and Howard except for dates of employment

and position title. TR 112.

Schwitzer claimed that it was merely applying its normal

policy with respect to references for individuals who have been

involuntarily terminated. TR 261. Yet, Joe Carpenter, a white

male, obtained a favorable letter of reference signed by Mr. Lane

Simpson, the Personnel Director of Schwitzer. This letter

stated: "Joe proved to be both willing and competent in

performing any duty required of him. I can recommend Joe to any

potential employer. ..." PX 10. Carpenter, who was terminated

from his position as a Machine Operator II for falsification of

timesheets, was the only machinist involuntarily terminated prior

to Lytle in 1983. Defendant claimed that Mr. Carpenter's letter

of reference was a mistake. TR 270.

C. THE DECISION BELOW

In dismissing plaintiff's claims under the Civil Rights Act

of 1866, 42 U.S.C. section 1981, the Court reasoned:

I will find from the pleadings in

this cause that there is no

independent basis alleged in the

1981 action. I will conclude,

based upon the reasoning of the

Tafoya case, that Title VII

provides the exclusive remedy, and

this case will be tried by the

12

Court without a jury, and the 1981

claim is dismissed.

TR 8.

In granting a Rule 41(b) dismissal of plaintiff's claim of

discriminatory discharge, the Court concluded that plaintiff had

not established a prima facie case of discrimination. The Court

first stated that plaintiff had 9.8 hours of unexcused absence.

TR 258. The Court also found that plaintiff had shown evidence

of four white employees who exceeded the excused absence limit

and who were given warnings. Id. The Court ruled "that the

conduct on the part of the white employees is not substantially

similar in seriousness to the conduct for which plaintiff was

discharged." TR 259. The Court therefore concluded "as a matter

of law that [plaintiff] has not established a prima facie case,

since he has not established that Blacks were treated

differently, and in fact committed violations of the company's

policy of sufficient seriousness." TR 259.

With regard to the retaliation claim, the Court, after

hearing all of the.evidence, made findings of fact that defendant

had a policy "that when asked for references from prospective

employees, the defendant provided only the dates of employment

and the job title and, if requested, a description." TR 300.

The Court found as fact "that the granting of that one favorable

letter of reference was done through inadvertence." TR 300.

13

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Plaintiff, alleging that his employer fired him because of

his race and then retaliated against him for filing an EEOC

charge, joined claims under both 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He requested a jury trial. The

primary issue raised by this appeal is whether the District Court

improperly dismissed plaintiff's claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and

thus deprived plaintiff of a jury trial on the critical questions

of discriminatory and retaliatory intent. If plaintiff was

entitled to a jury trial on his claims under § 1981, then the

District Court's determinations on plaintiff's Title VII claims

must be vacated to await resolution of joint factual issues by

the jury. Beacon Theatres v. Westover. 359 U.S. 500 (1959).

Plaintiff also argues that the District Court erred in

ruling that he did not establish a prima facie case of

discrimination under Title VII. However, in dismissing

plaintiff's discharge claim under Rule 41(b), the District Court

relied upon findings of fact on issues that should have been

reserved for the jury. Thus, this Court need not reach the Title

VII issue if it agrees that plaintiff is entitled to a jury trial

on the issue of liability.

With regard to the first issue, the United States Supreme

Court, this Court and a vast number of lower federal courts have

concluded that Title VII does not preempt claims under § 1981.

Rather, "Section 1981 affords a federal remedy against racial

14

discrimination in employment that is 'separate, distinct, and

independent' from the remedies available under Title VII."

Johnson v. Ryder Truck Lines. Inc.. 575 F.2d 471 (4th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied. 440 U.S. 979 (1979). These decisions rest squarely

on explicit legislative history that Title VII was not "meant to

affect existing rights granted under other laws." S. Rep. No.

415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 24 (1971).

It is not necessary that a victim of employment

discrimination "elect" remedies. Rather, "Title VII manifests a

congressional intent to allow an individual to pursue

independently rights under both Title VII and other application

state and federal statutes." Alexander v. Gardner-Denver. 415

U.S. 36, 48 (1974)(emphasis added).

Section 1981 and Title VII claims may be joined in a single

proceeding. Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 8(e)(2). Indeed, such joinder

should be encouraged to avoid the expense and inconvenience of

separate lawsuits. The United States Supreme Court, this Court

and scores of other federal courts have entertained complaints

joining § 1981 and Title VII claims.

Moreover, plaintiff in this case presented triable issues of

fact that should have been submitted to the jury. Plaintiff was

fired allegedly for excessive unexcused absences over a two and a

half day period in August, 1983. Plaintiff's so-called unexcused

absences consisted of leaving at the normal end of his shift on a

Thursday afternoon, rather than working overtime. Plaintiff

15

explained that he was required to leave on that afternoon because

of an emergency telephone call. Plaintiff was absent on the

following Friday and Saturday because of a doctor's appointment

and illness. Plaintiff submitted evidence that all of these

absences should have been excused under defendant's normal policy

of excusing absences caused by doctor's appointments, illness or

an urgent personal emergency. Clearly plaintiff's evidence

raised a triable question of fact as to whether discrimination

motivated the classification of his absences as unexcused.

Plaintiff also submitted evidence that five whites in his

department had excessive absences under the defendant's Absence

Policy and were not terminated. This evidence, particularly when

combined with plaintiff's more general evidence of discriminatory

intent, was sufficient to raise a question of fact concerning

defendant's motive in terminating plaintiff.

If the Court rules that plaintiff was unconstitutionally

denied the right to a jury trial, the trial court's dismissal of

his Title VII claims must be vacated. Under Beacon Theatres, all

joint issues of fact concerning legal and equitable claims that

have been raised in a single lawsuit must first be decided by the

jury. Only then may the remaining equitable issues be decided by

the Court. The District Court erred in this case by denying the

request for a jury trial and then deciding the Title VII claims.

To correct this error, the Title VII judgment must be vacated and

remanded for entry of a ruling consistent with the jury's verdict

16

on the § 1981 claims.

If this Court does not order a jury trial on joint issues of

fact affecting plaintiff's Title VII claims of discrimination and

retaliation, then the Court must decide whether plaintiff

established a prima facie case of discriminatory discharge.

Under the standards announced in Moore v. City of Charlotte. 754

F . 2d at 1100, 1110 (4th Cir.), cert, denied. 105 S.Ct. 3489

(1985), plaintiff clearly met this burden. Moore directs that

the District Court analyze similarity of offenses by utilizing

the employer's own scale of seriousness of offenses. Here,

plaintiff showed that other employees had "excessive absences"

within the meaning of his employer's definition and yet were not

terminated. Moreover, plaintiff presented a prima facie case of

discrimination in the classification of absences as unexcused in

circumstances where the absences of white employees were excused.

Thus, the District Court's Rule 41(b) dismissal of plaintiff's

claim of discriminatory discharge must be reversed.

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRONEOUSLY DISMISSED PLAINTIFF'S

CLAIM UNDER 42 U.S.C. SECTION 1981 AND

UNCONSTITUTIONALLY DEPRIVED PLAINTIFF OF HIS RIGHT TO A

JURY TRIAL

A. TITLE VII DOES NOT PREEMPT CLAIMS UNDER 42

U.S.C. SECTION 1981

Plaintiff's complaint joined claims under both Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Civil Rights Act of 1866,

codified as 42 U.S.C. § 1981. Title VII and § 1981, "although

17

related, and although directed to most of the same ends, are

separate, distinct and independent." Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency Inc.. 421 U.S. 454, 461 (1975). Section 1981 authorizes a

civil action to secure "a limited category of rights,

specifically defined in terms of racial equality." General

Building Contractors Ass'n v. Pennsylvania. 458 U.S. 375, 384

(1982).2 The rights protected by § 1981 are based on the

fundamental principles of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth

Amendments.3 Section 1981 "on its face relates primarily to

racial discrimination in the making and enforcement of

contracts," including discrimination in employment.4 Railway

2Section 1981 is derived from §1 of the Civil Rights Act of

1866. See General Building Contractors. 458 U.S. at 384. It was

recodified as §16 of the Civil Rights Act of 1870. Id. at 385.

As currently codified, 42 U.S.C. §1981 provides:

All persons within the jurisdiction

of the United States shall have the

same right ... to make and enforce

contracts ... as is enjoyed by

white citizens.

3General Building Contractors. 458 U.S. at 396, n.17; Mahone

v. Waddle. 564 F.2d 1018, 1030 (3d Cir. 1977), cert, denied. 438

U.S. 904 (1978); Young v. International Telephone and Telegraph

Co. , 438 F.2d 757, 759 (1971); Waters v. Wisconsin Steelworks.

427 F.2d 476, 482 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied. 400 U.S. 911

(1970) .

4The reach of section 1981 is not limited to employment

discrimination. See, e.g.. Runvan v. McCrary. 427 U.S. 160, 172-

73 (1976)(§1981 prohibits private, nonsectarian, commercially-

operated schools from denying admission on the basis of race);

Marable v. H. Walker & Associates. 644 F.2d 390, 395 (5th Cir.

1981)(§1981 applied to invidious discrimination in housing); Hall

v. Pennsylvania State Police. 570 F.2d 86, 91-2 (3d Cir.

1978)(§1981 requires commercial enterprises to extend the same

18

Express. 421 U.S. at 459-60.

Title VII, by contrast is limited in its coverage to

employment discrimination. However, Title VII covers such

discrimination on the basis of religion, sex and national origin

as well as race and color. Moreover, Title VII prohibits

unintentional discrimination under the disparate impact theory of

liability, while §1981 liability requires a finding of

discriminatory intent.5

Section 1981 and Title VII also provide different procedures

and remedies. "[T]he two procedures augment each other and are

not mutually exclusive." H.R. Rep. No. 238, 92d Cong. 1st Sess.

19 (1971) . Section 1981 provides the right to a jury trial,

while Title VII does not. In addition, Title VII provides a

mandatory, comprehensive administrative scheme of enforcement.

"[T]he filing of a Title VII charge and resort to Title VII's

administrative machinery are not prerequisites for the

institution of a § 1981 action." Railway Express. 421 U.S. at

460. Section 1981 authorizes compensatory and punitive damages,

as well as the types of equitable relief provided by Title VII.

Id.

in Johnson v. Ryder Truck Lines. Inc.. 575 F.2d 471 (4th

Cir. 1978), cert, denied. 440 U.S. 979 (1979), this Court held

treatment to contractual customers).

5Compare Griggs v. Duke Power Co.. 401 U.S. 424 (1971). with

General Building Contractors. 458 U.S. at 389.

19

that Title VII does not preclude relief under 42 U.S.C. §1981.

The Court concluded: "The Civil Rights Act of 1964 did not

repeal by implication any part of §1981 ... Section 1981 affords

a federal remedy against racial discrimination in private

employment that is 'separate, distinct, and independent' from the

remedies available under Title VII of the 1964 Act." Id. at 473-

74.

This Court's decision in Ryder Truck Lines is consistent

with binding Supreme Court precedents and with the overwhelming

weight of authority in the lower federal courts. In Johnson v.

Railway Express Agency. 421 U.S. at 461, the Supreme Court

rejected the theory that Title VII is the exclusive remedy for

private employment discrimination. In that case, the Court held

that the timely filing of a charge with the EEOC under Title VII

did not toll the running of the limitations period for a §1981

claim based upon the same facts. Id. at 466. The Court

concluded "that Congress clearly has retained § 1981 as a remedy

against private employment discrimination separate from and

independent of the more elaborate and time-consuming procedures

of Title VII." Id. at 466.

The Supreme Court reaffirmed the Railway Express decision in

Brown v. GSA. 425 U.S. 820, 829 (1976). Brown held that section

717 of Title VII. provides the exclusive judicial remedy for

claims of discrimination in federal employment. The Court

contrasted this exclusive remedy for federal employees with the

20

Railway Express decision governing private employment. Id. The

Court in Brown further noted that Johnson rested on an explicit

legislative history of Title VII which "'manifests a

congressional intent to allow an individual to pursue

independently his rights under both Title VII and other

applicable state and federal statutes.'" 425 U.S. at 833

(emphasis added)(quoting Alexander v. Gardner-Denver. 415 U.S. at

48) . See also Electrical Workers v. Robbins & Mvers, Inc.. 429

U.S. 229, 236-37 (1976).

The District Court's conclusion that "Title VII provides the

exclusive remedy" also conflicts with decisions of numerous lower

federal courts holding that Title VII did not preempt §1981.6

These court decisions are soundly based on the legislative

history of Title VII. In 1964, Congress rejected an amendment

proposed by Senator Tower that would have made Title VII the

exclusive federal remedy for employment discrimination. 110

Cong. Rec. 13650-52 (1964). In support of this amendment,

Senator Ervin read the text of §1981 into the record. 110 Cong.

Rec. 13075. Thus, Congress' knowledge of the §1981 cause of

action when it rejected Senator Tower's amendment cannot be

doubted.

6E.g. , Lowe v, City of Monrovia. 775 F.2d 998, 1010 (9th

Cir. 1985); Harris v. Richards Mfq. Co. . 675 F.2d 811, 814 (6th

Cir. 1982); Goss v. Revlon Inc. . 548 F.2d 405, 407 (2d Cir.

1976); Sanders v. Dobbs Houses. Inc.. 431 F.2d 1097, 1100 (5th

Cir. 1970), cert. denied. 401 U.S. 948 (1971); Waters v.

Wisconsin Steelworks. 427 F.2d 476, 434-85 (7th Cir.), cert. denied. 400 U.S. 911 (1970).

21

When Title VII was extended to cover state and local

employees in 1972, both the House and the Senate Reports

reaffirmed the continued viability of § 1981 as a remedy for

employment discrimination. The House Report stated:

[T]he Committee wishes to emphasize

that the individual's right to file

a civil action in his own behalf,

pursuant to the Civil Rights Act of

1870 . . ., 42 U.S.C. § 1981, . . .

is in no way affected.

Title VII was envisioned as an

independent statutory authority

meant to provide an aggrieved

individual with an additional

remedy to redress employment

discrimination.

H.R. Rep. No. 238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 18-19 (1971).7 The

Senate Report similarly provided that Title VII was not "meant to

affect existing rights granted under other laws." S. Rep. No.

415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 24 (1971).8

In addition, in 1972 Congress twice rejected a proposed

amendment that would have made Title VII an exclusive remedy.

7The Committee also noted with approval the Court decisions

in Young v. I.T. & T.. 438 F.2d 757 (3d Cir. 1971) and Sanders v.

Dobbs House, supra. holding that Title VII and § 1981 remedies

augment each other and are not mutually exclusive. Id.

8 Subsequent legislative history is most authoritative when

Congress relies on its understanding of the meaning of a statute

in revising the statute. E.g.. Bell v. New Jersey. 461 U.S. 773,

784-85 & n. 12 (1983); Bob Jones University v. United States. 461

U.S. 574, 599-602 (1983).

The Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized that the

authoritative source for legislative intent lies in the committee

reports on the bill. Thornburg v. Gingles. 54 U.S.L.W. 4877,

4881 n.7 (June 30, 1986). See also. Zuben v. Allen. 396 U.S.

168, 186 (1969) .

22

118 Cong. Rec. 3373, 3965. Senator Hruska, sponsor of the

proposed amendment, called upon the Senate to cure "the defects

of the existing law" and to avoid what he perceived to be an

unnecessary multiplicity of suits under other laws. 118 Cong.

Rec. 3960. He warned that without the Amendment, "the employee

could completely bypass both the E.E.O.C. and the N.L.R.B. and

file a complaint in Federal court under the provisions of the

Civil Rights Act of 18 66----» 118 Cong. Rec. 3173. Senator

Hruska reminded his colleagues that Title VII did not grant

exclusive jurisdiction of employment discrimination cases to the

EEOC. On the contrary, the design of Title VII provided for use

of "all available means." 118 Cong. Rec. 3960. Senator

Williams, in opposing the amendment, cautioned that the passage

of the Amendment would "wipe out" §1981, "one of the basic civil

rights statutes that have guided the country for a century." 118

Cong. Rec. 3963. Thus, Congress in 1972 was fully aware that

§1981 rights were not preempted by Title VII when it again

rejected an amendment to make Title VII the exclusive remedy for

employment discrimination.

B. TITLE VII AND SECTION 1981 CLAIMS MAY BE

BROUGHT IN THE SAME LAWSUIT

The Court below, and the Tafoya decision upon which it

relied, attempted to fashion two exceptions to the employment

discrimination victim's right to pursue both Title VII and §1981

remedies. First, the Court below appears to suggest that a

plaintiff may pursue only one of the two remedies available to

23

him. See TR 8 ("It would appear from a very cursory reading of

Johnson [v. Railway Express] that the Title VII action was never

filed as a lawsuit in that case."). Second, the Court in Tafoya

v . Adams. 612 F. Supp. 1097 (D.C. Colo. 1985), concluded that

while "Congress did not intend to preclude [state and local

employees] from bringing §§ 1981 and 1983 claims completely," 612

F. Supp. at 1101, the claims may not be joined "in the same

judicial proceeding" unless the § 1981 claims "are independent

and are not based on violations of rights set forth in Title

VII." Id. at 1102-1103. Both of these suggested limitations on

the availability of Title VII and § 1981 remedies are at odds

with the court authorities and legislative history and must be

rejected.

The suggestion that a victim of employment discrimination

must "elect" remedies has been rejected by the Supreme Court. In

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.. 415 U.S. 36, 46, 49 (1974), the

Court reversed rulings by a District Court and Court of Appeals

that "the doctrine of election of remedies" could apply to

preclude Title VII lawsuits. Instead, the Court held that "Title

VII manifests a congressional intent to allow an individual to

pursue independently his rights under both Title VII and other

applicable state and federal statutes." Id. at 48 (emphasis

added).

The legislative history mandates this conclusion. As noted

above, Congress intended that Title VII would provide an

24

additional remedy and that rights under § 1981 would not be

affected. H. R. Rep. No. 238, supra. at 18-19. Obviously,

forcing a plaintiff to elect remedies "affects'* the availability

of the § 1981 remedy. Moreover, Congress was aware of the

existence of multiple remedies. See 110 Cong. Rec. 13651

(1964)(Senator Tower). In 1972, Senator Hruska argued for

exclusivity because:

Court decisions issued subsequent

to the passage of Title VII have

held that Title VII has not

preempted the field of civil rights

in employment and thus an

individual has an independent cause

of action in cases of employment

discrimination pursuant to the

provisions of the Civil Rights Act

of 1866 (42 U.S.C. 1981) and 1871

(42 U.S.C. section 1983) and that

actions may be brought under all

three laws simultaneously.

118 Cong. Rec. 1791-92. (Emphasis added).

The notion that Title VII and § 1981 claims may not be

brought in the same proceeding unless the § 1981 claim is

supported by an "independent basis" is equally erroneous. Since

enactment of Title VII, the Supreme Court on numerous occasions

has issued decisions in cases where the plaintiff joined in the

same lawsuit a Title VII and a § 1981 claim based on the same

facts.9 Yet, the Court has never hinted that such a procedure is

9E.g., General Building Contractors, supra; New York City

Transit Authority v. Beazer. 440 U.S. 568, 577 (1979); McDonald

Yj__Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co. . 427 U.S. 273, 285, 296 (1976);

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co.. 424 U.S. 747, 750, n.l (1976).

25

prohibited or that two separate lawsuits should instead be

pursued.10 *

Similarly, this Court,11 and other federal courts in scores

of cases have heard both Title VII and §1981 claims based on the

same facts in the same lawsuit. See Fed. Rule Civ. Proc.

8(e)(2). These courts have afforded to plaintiffs the procedural

and substantive protections available under both statutes.12

10The Court in Johnson v. Railway Express appeared to

recommend such joinder of claims, when it suggested that a § 1981

plaintiff could ask the District Court to stay the § 1981

proceedings until the Title VII administrative process has been

completed. 421 U.S. at 465.

i:iE.g. . Brady v. Thurston Motor Lines. 726 F.2d 136, 138

(4th Cir.), cert, denied. 84 L.Ed.2d 53 (1984)(affirming finding

that defendant's employment practices violated both Title VII and

§ 1981), subsequent decision on remedy. 753 F.2d 1269 (4th Cir. 1985) .

12Lowe v. City of Monrovia. 775 F.2d 998, 1010 (9th Cir.

1985); Jones v. Western Geophysical Co.. 761 F.2d 1158, 1159 (5th

Cir. 1985)(Title VII and § 1981 claims tried simultaneously by

court sitting without a jury); Poolaw v. city of Anadarko. 738

F.2d 364, 368 (10th Cir. 1984), cert, denied. 84 L.Ed. 2d 779

(1985) (bench trial on Title VII and jury trial on § 1981 claims

conducted simultaneously); E.E.O.C. v. Gaddis. 733 F.2d 1373

(10th Cir. 1984); Harris v. Richards Mfq. Co.. 675 F.2d 811, 814

(6th Cir. 1982)("private plaintiff who sues under both Title VII

and Section 1981 may obtain the equitable relief provided by

Title VII and such equitable relief as well as legal relief by

way of compensatory and punitive damages afforded by Section

1981"); Williams v. Owens-Illinois, Inc.. 665 F.2d 918, 922, 925

(9th Cir. 1982), modified on other grounds. 28 FEP Cases 1820,

cert.denied. 459 U.S. 971 (1982)(§ 1981 claims tried to jury and

Title VII claims tried to court with advice of jury); Bibbs v.

Jim Lynch Cadillac. Inc.. 653 F.2d 316 (8th Cir. 1981); Whiting

3L:__Jackson State University. 616 F.2d 116 (5th Cir. 1980);

Claiborne v. Illinois Central Railroad. 583 F.2d 143, 146, 154

(5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied. 442 U.S. 934 (1979)(punitive

damage award under § 1981 proper "even when the section 1981

claim is joined with Title VII claims"); Gates v. I.T.T.

26

Other than the decision below, which is void of any legal

reasoning, Tafoya v. Adams stands alone in its holding that an

independent factual basis is required for the assertion of a

§1981 claim concurrently with a Title VII cause of action.13 The

Continental Bakina. 581 F.Supp. 204 (N.D. Ohio 1984)(plaintiff

asserting both Title VII and §1981 claims based on defendant's

rejection of his employment application entitled to jury trial on

§1981 claim for punitive damages and back pay); Powell v.

Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency. 563 F.Supp. 419 (M.D. Penn.

1983); Daniels v. Lord & Tavlor. 542 F.Supp. 68 (N.D. 111.

1982) (plaintiff charging discriminatory failure to promote,

discipline and discharge under both Title VII and §1981, entitled

to jury trial on §1981 legal claims); Thomas v. Resort Health

Related Facility. 539 F.Supp. 630 (E.D.N.Y. 1982)(plaintiff

bringing joint Title VII and §1981 claims for discriminatory

discharge entitled to jury trial on §1981 claim for mental

anguish); Acosta v. Univ. of District of Columbia. 528 F.Supp.

1215 (D.C. D.C. 1981).

13 Defendant in the court below relied upon a series of

footnotes in Fifth Circuit cases. See Rivera v. City of Wichita

Falls, 665 F . 2d 531, 534 n.4 (5th Cir. 1982); Carpenter v.

Stephen F. Austin State University. 706 F.2d 608, 612 n.l (5th

Cir. 198 3) ; Page v. U.S. Industries, Inc.. 726 F.2d 1038, 1041

n.2 (5th Cir. 1984); Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corn..

727 F . 2d 473, 475 n.l (5th Cir. 1984), cert, denied. 104 S.Ct.

3516 (1984).' See also Smith v. Western Elec. Co.. 770 F.2d 520,

521 n.l (5th cir. 1985).

However, it is clear that this line of footnotes addresses

only the appropriate procedure for appellate review of the

substantive question of liability in situations where the

plaintiff joins Title VII and §1981 claims that both rest on

allegations of intentional discrimination. They arise out of the

specific situation in Rivera, in which the legal basis for the

§1981 claim was unclear because the discrimination was on the

grounds of national origin, not race. This line of footnotes

stands only for the unexceptional proposition that in this

circumstance, the substantive elements of liability under §1981

parallel those under Title VII, and thus on appeal it is not

necessary for the Court to consider the liability questions

separately for §1981.

This line of footnotes stems from the Fifth Circuit's

conclusion in Whiting v, Jackson State University. 616 F.2d 116,

27

reasoning of the Tafova decision is severely flawed. The Court

in Tafova relied heavily on the Supreme Court decisions in Brown

121 (5th Cir. 1980), that "[w]hen section 1981 is used as a

parallel remedy with section 706 of Title VII against disparate

treatment in employment, its elements appear to be identical to

those of section 706." In Whiting. Title VII and §1981 claims

were joined in the same lawsuit and the plaintiff obtained a jury

trial. Thus, it is clear that the statement in Whiting refers

only to the elements of substantive liability, and does not to

deny the availability of both remedies, including their different

procedures or remedies.

The footnote in Rivera. the lead case relied upon by

defendant, cites Whiting as an explanation for its conclusion

that "consideration of alternative remedies was not necessary."

It is inconceivable that the Fifth Circuit would cite with

approval a case that affirmed the plaintiff's right to assert

§1981 and Title VII claims jointly and to obtain a jury trial on

the §1981 claims, if in the same footnote, the Court intended to deny such rights.

The meaning of the Rivera footnote is further explained in

two subsequent footnotes in this line. In Page v. U.s.

Industries, Inc.. 726 F.2d at 1041 n.2 (1984), the Court referred

to the Rivera footnote as a "rule of this Court" establishing

when "consideration of an alternative remedy brought under §1981

is necessary." And in its most recent citation to the Rivera

footnote, the Fifth Circuit explained: "Because the same

analyses apply to claims under section 1981 as under Title VII

[citing Rivera footnote], we shall consider [the §1981] claim

together with the Title VII claim. The district court made no

separate finding on this issue." Smith v. Western Elec. Co.. 770

F.2d at 521 n. 1 (1985). It is significant that the Court did

not dismiss the §1981 claim, but merely considered it on appeal

"together" with the Title VII claim.

This meaning of the Rivera footnote also is confirmed by

recent Fifth Circuit decisions. In cases where the existence of

the^ §1981 claim makes a difference in the procedures or remedy

available, the Court has carefully protected the plaintiff's

entitlement to the attributes of a §1981 claim, notwithstanding

the joinder of a Title VII claim. Hamilton v. Rodgers. 791 F.2d

439, 440-42 (5th Cir. 1986)(where §1981 and §1983 claims joined

with Title VII claim, court notes that substantive elements of

liability are same under all statutes, but that compensatory

damages for emotional injury may be awarded under §198 3) ; Whiting

supra; Claiborne, supra; Jones v. Western Geophysical Co., supra.

28

v. GSA. supra, and Great American S. & L. Ass'n v. Novotnv. 442

U.S. 366 (1979). 612 F. Supp. at 1100. But, as noted above, the

Brown decision carefully distinguished Johnson v.Railway Express.

Similarly, the Court in Novotnv. in holding that "§ 1985(c)14 may

not be invoked to redress violations of Title VII," 442 U.S. at

378, again distinguished § 1981. The Court noted that unlike

cases involving §1981, "[t]his case ... does not involve two

'independent' rights." Id.15 Thus, neither Brown nor Novotnv

can be construed to support the decision in Tafoya.

The Court in Tafoya also reasoned that to permit the

assertion of non-independent § 1981 claims in the same lawsuit

with a Title VII claim would "subvert" Title VII's comprehensive

remedial scheme. 612 F.Supp. at 1101. However, this argument

was considered and rejected in Railway Express. The Court there

14Section 1985(c) establishes a cause of action for damages

caused by actions in furtherance of a conspiracy to deprive a

person or class of persons of equal protection of the laws.

15The Court further explained:

This case thus differs markedly from the

cases recently decided by this Court that

have ... held that substantive rights

conferred in the 19th century were not

withdrawn, sub silentio, by the subsequent

passage of the modern statutes. . . . And in

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency [citation

omitted], we held that the passage of Title

VII did not work an implied repeal of the

substantive rights to contract conferred by

the same 19th century statute and now

codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

Id. at 377.

29

noted that the availability of a § 1981 cause of action might

permit a plaintiff to avoid Title VII's detailed administrative

procedures. However, Court concluded that "these are the natural

effects of the choice Congress has made available to the claimant

by it conferring upon him independent administrative and judicial

remedies." 421 U.S. at 461.

Moreover, the "independent basis" requirement of Tafoya is

incomprehensible. The Court apparently used this phrase to refer

to claims with an independent legal, as opposed to factual,

basis.16 Yet, the authorities are overwhelming that a Section

1981 race discrimination claim rests on inherently independent

legal grounds. E.q., Johnson v. Railway Express. 421 U.S. at

459-60; Johnson v. Ryder Truck. 575 F.2d at 473-74. Even the

Court in Tafoya acknowledged that "independent of Title VII

remedies, § 1981 ... provide[s] remedies for racial

discrimination." 612 F. Supp. at 1099 (emphasis added).

Finally, the suggestion is ludicrous that a plaintiff should

be encouraged to bring two separate lawsuits to enforce both

Title VII and § 1981 with respect to the same set of facts. Such

a solution, while it may be tolerated in some situations, see

Railway Express. 421 U.S. at 461, certainly is not the preferred

or most efficient manner of litigating independent claims that

16The Court in Tafoya distinguished a binding Tenth Circuit

precedent, Owens v. Rush. 654 F.2d 1370 (1981), on the ground

that the plaintiff there "alleged violations of independent

substantive rights in addition to his Title VII claims." 612 F. Supp. at 1104 n.5.

30

are legally and factually similar.17

C. PLAINTIFF'S RETALIATION CLAIM IS ACTIONABLE

UNDER 42 U.S.C. SECTION 1981

It is well-established that 42 U.S.C. § 1981 encompasses a

cause of action for retaliation for the filing of race

discrimination claims. This is because "[t]he ability to seek

enforcement and protection of one's right to be free of racial

discrimination is an integral part of the right itself." Goff v.

Continental Oil Co,. 678 F.2d 593, 598 (5th Cir. 1982). "Section

1981 would become meaningless if an employer could fire an

employee for attempting to enforce his rights under that

statute." Id.

Similarly, § 1981 creates a cause of action for retaliation

against an employee who files a charge of discrimination under

Title VII. Retaliation against someone who files an EEOC charge

alleging racial discrimination "would inherently be in the nature

of a racial situation." Setser v. Novack Investment Co.. 638

F • 2d 1137, 1146 (8th Cir.), modified. 657 F2d 932, cert, denied.

102 S.Ct. 615 (1981). "[I]t would be impossible completely to

17The court in Tafoya did not explain how the two separate

lawsuits^ would relate to each other, if at all. Presumably if

the plaintiff lost in the first lawsuit, collateral estoppel

would bar relitigation of facts. If plaintiff first prevailed in

a Title VII lawsuit, a second action under §1981 would be

necessary on any claims for compensatory or punitive damages, or

for damages outside the two-year backpay limit of Title VII. If

the plaintiff first prevailed in a §1981 lawsuit, a subseguent

Title VII litigation might still be necessary to address claims

under the disparate impact theory of liability, which is beyond the scope of §1981.

31

disassociate the retaliation claim from the underlying charge of

discrimination." Goff. 678 F.2d at 599. For this reason, five

federal circuits,18 and numerous district courts,19 have held

that § 1981 prohibits retaliation for the filing of an EEOC

charge. Indeed, no federal Court of Appeals has held to the

contrary.20

D. PLAINTIFF IS CONSTITUTIONALLY ENTITLED TO A

JURY TRIAL ON HIS SECTION 1981 CLAIMS

It is undisputed that a plaintiff is constitutionally

entitled to a jury trial on all legal claims for relief under

18E.q., Choudhurv v. Polytechnic Institute of New York. 735

F .2d 38 (2d Cir. 1984); DeMatteis v. Eastman Kodak Co.. 511 F.2d

306, 312 (2d Cir. 1975), modified on other grounds. 520 F.2d 409

(2d Cir. 1975); Goff, supra (5th Cir.); Pinkard v. Pullman-

Standard, 678 F .2d 1211, 1229, n.15 (5th Cir. 1982)(per curiam),

cert denied, 459 U.S. 1105 (1983); Whiting v. Jackson State

University, 616 F.2d 116 (5th Cir. 1980); Harris v. Richards Mfg.

Co. , 675 F.2d 811, 812 (6th Cir. 1982); Winston v. Lear-Siecler

Inc. , 558 F.2d 1266, 1268-70 (6th Cir. 1977); Greenwood v, Ross.

778 F .2d 448, 455 (8th Cir. 1985); Sisco v. J.S. Alberici Const.

Co.;../ 655 F. 2d 146, 150 (8th Cir. 1981), cert, denied. 455 U.S.

976 (1982); Setser v. Novack. supra (8th Cir.); London v.

Coopers & Lybrand. 644 F.2d 811 (9th Cir. 1981).

19E.q., Moffett v. Gene B. Glick Co.. 621 F. Supp. 244, 282-

83 (N.D. Ind. 1985); Gresham v. Waffle House, Inc.. 586 F. Supp.

1442, 1446 (N.D. Ga. 1984); Cox v. Consolidated Rail Corn.. 557

F. Supp. 1261, 1265 (D.D.C. 1983).

20In the 1970's, a few federal district courts in the Second

and Fifth (now Eleventh) Circuits concluded that § 1981 did not

encompass retaliation. See Hudson v. I.B.M.. 22 FEP Cases 947

(S.D.N.Y. 1975)(decision on merits affirmed without reaching

retaliation issue, 620 F.2d 351 (2d Cir.), cert, denied. 449 U.S.

1066 (1980)); Takeall v, WERD, Inc.. 23 FEP Cases 947 (M.D. Fla.

1979) ; Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corn.. 22 FEP Cases 680 (S.D.N.Y.

1978), Barfield v. A.R.C. Security, Inc.. 10 FEP Cases 789 (N.D.

Ga. 1975) . However, all of the decisions have been discredited

by later Court of Appeals decisions. E.g.. Choudhurv. supra (2d

Cir.); Goff, supra. (5th Cir.).

32

§1981. Harris v. Richards Mfq. Co. . 675 F.2d 811, 814-15 (6th

Cir. 1982); Williams v. Owens-Illinois, Inc.. 665 F.2d 918, 928

(9th Cir. 1982); Setser v. Novack Investment Co.. 638 F.2d 1137,

1140 (8th Cir. 1981), modified on other grounds. 657 F.2d 962 (en

banc), cert, denied. 454 U.S. 1064 (1981); Moore v. Sun Oil Co.

of Pennsylvania. 636 F.2d 154, 156 (6th Cir. 1980). See also

Secrara v. McDade. 706 F.2d 1301, 1304 (4th Cir. 1983) (right to

jury trial under 42 U.S.C. §1983); Burt v. Abel. 585 F.2d 613,

616 n. 7 (4th Cir. 1978)(same).21 In this case, Lytle asserted a

legal claim under §1981 for compensatory and punitive damages,

including emotional distress. JA 7 (Complaint, £> 23), JA 10

(Amendment to Complaint).22

Lytle presented sufficient evidence to send both his

discharge and retaliation claims to the jury. Although the

District Court dismissed the parallel Title VII discharge claim

under Rule 41(b), such a dismissal is not equivalent to a ruling

that plaintiff presented insufficient evidence to send the § 1981

21In Curtis v. Loether. 415 U.S. 189, 194 (1974), the

Supreme Court held that the Seventh Amendment applies to an

action in federal court to enforce a civil rights statute that

creates legal rights and remedies. The right to a jury trial

thus applies under §1981 because that section affords plaintiffs

both equitable and legal relief, including compensatory and, in

some cases, punitive damages. Johnson v. Railway Express. 421

U.S. at 460.

22Since plaintiff was entitled to a jury trial with respect

to all legal claims arising under §1981, he was entitled to have

a jury determine liability. Moore. 636 F.2d at 157. See. B.

Schlei & P. Grossman, Employment Discrimination Law, 1983-84 Cum.

Supp. 212 (2d Ed.). See also Point II, below.

33

discharge claim to the jury. A dismissal in a non-jury case

under Rule 41(b) is "on the ground that upon the facts and the

law the plaintiff has shown no right to relief." Fed. Rule Civ.

Proc. 41(b)(emphasis added). Rule 41(b) by its terms applies

only "in an action tried by the court without a jury." Id. The

Rule explicitly provides that "the court as trier of the facts

may determine them." Id. If the court enters a Rule 41(b)

dismissal against the plaintiff, it "shall make findings as

provided in Rule 52(a)." Id.

The difference between a Rule 41(b) dismissal in a non-jury

case and a directed verdict in a jury trial has been noted by

many courts. As recently explained by the Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit,

the court's role [under Rule 41(b)]

is fundamentally different from its

role in a jury trial when ruling on

a defendant's motion for a directed

verdict at the close of the

plaintiff's case. In ruling on a

motion for directed verdict, the

judge must determine if the

evidence is such that reasonable

minds could differ on the

resolution of the questions

presented in the trial, viewing the

evidence in the light most

favorable to the plaintiff. On a

motion for directed verdict, the

court may not decide the facts

itself. In deciding a Rule 41(b)

motion, however, the trial court in

rendering judgment against the

plaintiff is free to assess the

credibility of witnesses and the

34

evidence and to determine that the

plaintiff has not made out a case.23

In this case, there is no doubt that the District Court

relied upon findings of fact in entering the Rule 41(b) dismissal

of plaintiff's discharge claim. The District Court's conclusion

that plaintiff had 9.8 hours of excessive unexcused absence was

crucial to its dismissal of the discharge claim. Yet,

plaintiff's evidence showed, and defendant did not deny, that an

excused absence will be granted as a matter of course for

doctor's appointments, illness and urgent family obligation.

Lytle testified that he informed his supervisor of both his

Friday doctor's appointment and his physical inability to work on

Saturday. Thus, plaintiff presented sufficient proof for a jury

to conclude that, absent racial discrimination, Lytle's absences

on both Friday and Saturday would have been excused.24

Similarly, Lytle testified that he attempted to inform

Miller about the emergency telephone call on Thursday afternoon

and that Miller was abusive and would not listen. A jury could

23Continental Casualty Co. v. DHL Services. 752 F.2d 353,

355-56 (1985). Accord Stearns v. Beckman Instruments, Inc.. 737

F.2d 1565, 1567 (Fed. Cir. 1984)(judgment under Rule 41(b) "need

not be entered in accordance with a directed verdict standard");

Wilson v. United States. 645 F.2d 728, 730 (9th Cir. 1981) ("The

Rule 41(b) dismissal must be distinguished from a directed

verdict under Rule 50(a)."). See generally V MOORE'S FEDERAL

PRACTICE 41-175 to 41-179 (1985).

24See, Gairola v. Virginia Dept, of General Services. 753

F . 2d 1231 (4th Cir. 1985) (it is for jury to weigh the evidence

and pass on credibility); Ellis v. International Plavtex, Inc..

745 F .2d 292, 298 (4th Cir. 1984).

35

reasonably conclude that, absent discrimination, Lytle's failure

to work overtime on Thursday afternoon would have been excused as

an urgent family obligation.

Second, even if the jury determined that plaintiff was

properly charged with unexcused absence, whether white employees

were treated more leniently for similar offenses is a question of

fact that also must be decided by the jury.

The District Court itself indicated that it was making

findings of fact about issues on which reasonable individuals

could differ. During argument on the Rule 41(b) motion, Mr.

Lytle's attorney suggested that "the only reason Mr. Lytle is

being charged with unexcused absence . . . is because of Mr.

Larry Miller's decision not to consider Friday a vacation day and

to make Saturday a mandatory 8-hour overtime work period. And

the misunderstanding that Mr. Lytle had about that is the only

reason he didn't call in." TR 252-53. In response to an

objection that the argument was "not necessarily supported by the

evidence here" the Court stated: "It's a reasonable

interpretation of the evidence." TR 253. Thus, had the District

Court not dismissed plaintiff's section 1981 claim, there is no

doubt that the Court would have sent the discharge claim to the

jury.

Plaintiff also presented more than enough evidence to send

his retaliation claim to the jury, as acknowledged by the

District Court when it denied the Rule 41(b) motion on this

36

claim. The retaliation claim turns on the factual question

whether Schwitzer's favorable letter of recommendation for Joe

Carpenter was a mistake. This factual determination will depend

heavily on the fact-finder's assessment of credibility.

Therefore, plaintiff is constitutionally entitled to a jury trial

on his retaliation claim.

II. THE TRIAL COURT'S JUDGMENT ON PLAINTIFF'S TITLE VII

CLAIMS MUST BE VACATED

In Beacon Theatres v. Westover. 359 U.S. 500, 508-12 (1959),

the Supreme Court held that where legal and equitable claims

based on the same factual allegations are joined in the same

case, the District Court must, absent "the most imperative

circumstances," try the legal claims to the jury before itself

deciding the equitable claims. This order of proof is necessary

to avoid depriving a party of the right to a jury trial on the

legal claims. Id. See also Dairy Queen v. Wood. 369 U.S. 469

(1962) .

Applying Beacon Theatres to the facts of this case, the

District Court's decision and judgment on Lytle's Title VII

claims must be vacated to allow a jury determination of all

relevant facts. The appropriate procedure is for the jury to

determine the issue of liability and for the Court subsequently

to determine any issues of remedy that are of an equitable

nature. See Moore v. Sun Oil. 636 F.2d at 157; Gates v. ITT

Continental Baking Co.. 581 F. Supp. 204, 297 (N. D. Ohio

1984)("in ruling upon plaintiff's claim pursuant to [Title VII],

37

the Court is bound by the jury's determination of facts"); Thomas

v. Resort Health Related Facility. 539 F.Supp. 630, 634 (E.D.N.Y.

1982) .

III. PLAINTIFF ESTABLISHED A PRIMA FACIE CASE OF

DISCRIMINATORY DISCHARGE UNDER TITLE VII

A. PLAINTIFF ESTABLISHED A PRIMA FACIE CASE

UNDER THE SUPREME COURT'S MODEL OF PROOF OF

INDIVIDUAL DISCRIMINATORY TREATMENT

The Supreme Court has developed a model of proof to be used

in individual Title VII cases "to bring the litigants and the

court expeditiously and fairly to [the] ultimate question" of

discriminatory intent. Under this model, the plaintiff first has

the burden of establishing a prima facie case. Texas Department

of Community Affairs v. Burdine. 450 U.S. 248, 254 (1981). For

example, a plaintiff who was not rehired allegedly because of his

commission of an offense against the employer may establish a

prima facie case by showing:

(i) that he belongs to a racial

minority; (ii) that he applied and

was qualified for a job for which

the employer was seeking

applicants; (iii) that, despite his

qualifications, he was rejected;

and (iv) that, after his rejection,