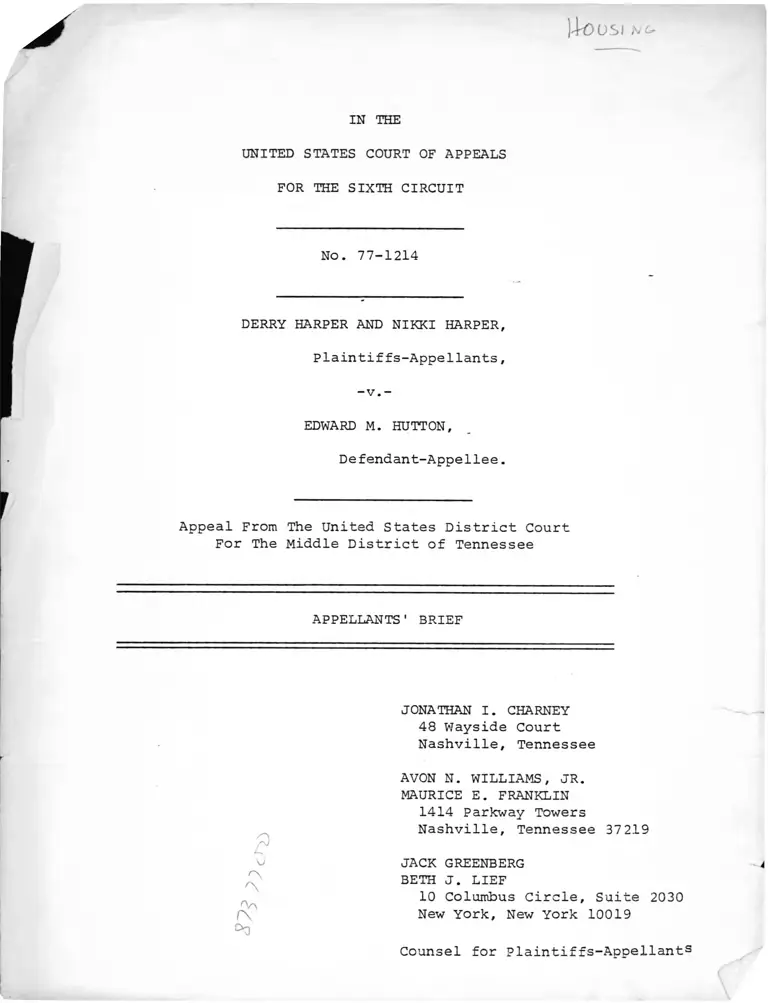

Harper v. Hutton Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harper v. Hutton Appellants' Brief, 1979. 023cfb6a-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f15fbc15-fc4c-4ca1-9366-1182bc492048/harper-v-hutton-appellants-brief. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

)-k)OSl NC,

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 77-1214

DERRY HARPER AND NIKKI HARPER,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-v.-

EDWARD M. HUTTON,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District of Tennessee

APPELLANTS' BRIEF

LVj

°r\

r\

JONATHAN I. CHARNEY

48 Wayside Court

Nashville, Tennessee

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

MAURICE E. FRANKLIN

1414 Parkway Towers

Nashville, Tennessee 37 2.19

JACK GREENBERG

BETH J. LIEF

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

INDEX

Statement of the Issues Presented.......................... vi

Statement of the Case..................................... 1

Statement of Facts........................................ 6

Argument

I. On The Basis Of The Uncontradicted Evidence

And The Facts As Found By The District Court,

Plaintiffs Derry And Nikki Harper Were Denied

Housing And Victimized By Unlawful Racially

Discriminatory Practices 19

II. Defendant's Deliberate Failure To Tell The

Harpers Of The Availability Of An Efficiency

Apartment On September 10, 1976 Violates The

Plaintiffs' Rights Under The Fair Housing

Law............................................ 35

CONCLUSION................................................. 40

Page

Table of Cases

Banks v. Perks, 341 F. Supp. 1175 (N.D. Ohio 1972).......... 26

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp.,495 F.2d 437

(5th Cir. 1974)............................................. 31

Boyd v. Lefrak Org. 509 F.2d 1110 (2d Cir. 1975)cert, denied,

423 U.S. 895 (1975)......................................... 34, 31

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Mach. Co., 457 F.2d 1377

(4th Cir. 1972).......................................;26,30,31

Causey v. Ford Motor Co., 516 F.2d 416 (5th Cir. 1975........ 19,20

Dailey v. City of Lawton, 296 F. Supp. 266 (W.D. Okla. 1969),

aff'd, 425 F . 2d 1038 (10th Cir. 197)........................ 29

Elazar v. Wright Prentice-Hall Equal Opportunity in Housing

§ 15, 197 (S.D. Ohio 1976)................................... 28,37

Harper v. Union Savings Assoc., Prentice-Hall Equal Opp. in

Housing, 515,203 (W.D. Ohio 1977).............................. 32

Haythe v. Decker Realty, 468 F.2d 336 (7th Cir. 1972)....... 29,38

Hester v. Southern Railway Co., 497 F.2d 1374 (5th Cir. 1974) 20

Johnson v. Jerry Pals Real Estate, 485 F.2d 528 (7th Cir. 1973 38

Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S. 409 (1968)....................... 25,34,38

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939).......................... 25

Nader v. Allegheny Airline, Inc. 512 F.2d 527 (D.C. Cir. 1975) 19

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co. 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974)............................................. 31

Rogers v. Internal Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340

(8th Cir. 1975)............................................ 31

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F .2d 348

(5th Cir. 1972)............................................ 20,31

Page

-ii-

Table of Cases (Continued)

Page

Senter v. General Motors Corp., 532 F.2d 511

(6th Cir. 1976)............................ 19,20,31

Sims v. Sheet Metal Workers Int., Ass'n, Local 65,

489 F . 2d 1023 (6th Cir. 1973).........................

Singleton v. Jackson Mun. Sep. School District,

419 F . 2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1970)........................

Smith v. Adler, 436 F.2d 344 (7th Cir. 1970)............ ... 26,29

Smith v. Concordia Parish Sch. Bd. 445 F.2d 285

(5th Cir. 1971....................................

Smith v. Sol D. Adler Realty Co., 436 F.2d 344

(7th Cir. 1971)..................................

State of Alabama v. United States, 304 F.2d 583 (5th Cir.

aff'd, 371 U.S. 37 (1962).............................

1962)

Stewart v. General Motors Corp., 542 F.2d 445

(7th Cir. 1976).......................................

Todd v. Lutz, Prentice-Hall Equal Opportunity in Housing

1(13,787 (W.D. Penn. 1976).............................

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co. 409 U.S. 205

(1972).....................................

United States v. Aubinoe, Prentice-Hall Equal Opp. in

Housing, 515,206 (D. Md. 1977)........................

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418

(5th Cir. 1971)......................................

United States v. Mintzes, 304 F. Supp 1305 (D. Md 1969).. 26

United States v. N.L. Industries, 479 F.2d 354

(8th Cir. 1973).....................................

United States v. Northside Realty Associates, Inc.,

518 F .2d 884 (5th Cir. 1975).......................

-in-

Table of Cases (Continued)

United States v. Pelzer Realty, 484 F.2d 438

(5th Cir. 1973.......................... ......... 19, 20,26,34,37

United States v. Real Estate Development Corp.,

347 F. Supp. 776 (N.D. Miss. 782)................... 25,26, 29,38

United States v. Reddoch, 467 F.2d 897 (5th Cir. 1972)... 21,26,29

United States v. Senger Mfg. Co., 374 U.S. 174 n. 9

(1963).................................................. 19

United States v. West Peachtree Tenth Corp. 437 F.2d

221, 226 (5th Cir. 1971).............................. 29,34,37

United States v. Youritan Construction Co., 370 F. Supp.

643 (N.D. Cal. 1973), aff'd, 509 F.2d 623 (9th Cir.

1975)...................................... 20,21, 27, 29, 30,34,36

Weathers v. Peters Realty Corp., 499 F.2d 1197

(6th Cir. 1974)....................................... 21,34

Williams v. Matthews Co., 499 F.2d 819 (8th Cir. 1974),

cert, denied, 419 U.S. 1021 (1974) 21,25,29,30,34

Williamson v. Hampton Management, 339 F. Supp 1146

(N.D. 111. 1972)..................................... 26

Zuch v. Hussey, 394 F. Supp. 1028 (E.D. Mich 1975)

aff'd F . 2d 1168 (6th Cir. 1977)........................ 34

Page

-iv-

Table of Statutes and Authorities

Page

Federal Rule Civil Procedure 5 2(a)...................... 19

42 U.S.C. §1982........................................ . . 24

42 U.S.C. §3604 (a)................................... 27,37

42 U.S.C. §3604 (d)...................................... 35

U.S. Bureau of the Census, General Population

Statistics, Tennessee (1970) 44-70.................. 21

-v-

Statement of the Issues presented

1. whether, on the basis of the uncontradicted

evidence and the facts as found by the District Court,

Plaintiffs Derry and Nikki Harper were denied housing

and victimized by unlawful racially discriminatory practices.

2. Whether the Defendant's deliberate failure to

tell the Harpers of the availability of an apartment violates

the Plaintiffs' rights under the fair housing laws.

-vi

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1214

DERRY HARPER AND NIKKI HARPER,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

-v. -

EDWARD M. HUTTON,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court

For The Middle District of Tennessee

APPELLANTS' BRIEF

Statement of the Case

The appellants in this case, a black married couple,

charge defendant with racial discrimination in the rental

of units at Natchez Village Apartments in Nashville,

Tennessee. Jurisdiction in the Court below was predicated

on 28 U.S.C. § 1343(4) and 42 U.S.C. § 3612; plaintiffs

alleged violations of their rights under the 1968 Fair

Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. § 3601 et seg, and the Civil Rights

Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1982 to secure a dwelling without

discrimination on the basis of race or color (A. 6, 22).

This appeal challenges the district courts' interpretation

of the facts, application of the law, and dismissal of the

complaint.

The action began on September 23, 1976 when the

complaint was filed in the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Tennessee. Plaintiffs Derry

and Nikki Harper alleged that they visited Natchez

Village Apartment on September 4, 1976 and sought to rent

an apartment there; that the owner and manager of the

complex, defendant Edward M. Hutton, refused to rent the

apartment to them when they applied and required them to

give detailed financial information and to wait while a

credit check was run, although such requirements are not

imposed on white applicants; that the purpose of such

requirements was to discourage blacks and avoid renting

to them; and that thereafter he rented the apartment to

a white person and refused to rent an apartment to

plaintiffs (A. 6-8). The complaint sought a preliminary

and permanent injunction, compensatory and punitive

damages, and attorney's fees (A. 9-10).

On the same day that the complaint was filed, plain

tiffs filed a Motion for a Preliminary Injunction (A. 11-17)

A hearing was held on the Motion for a Preliminary

Injunction on September 30, 1976 (A. 23). The parties

agreed to consolidate the hearing with a trial on the

merits pursuant to Rule 65(a)(2) of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure (A. 23).

-2-

On December 22, 1976 the district court issued

its findings of fact and conclusions of law (A. 22-34).

The court found that:

(1) Plaintiffs were a black married couple and

that each was a full-time student; Derry,

at Vanderbilt University Law School, and

Nikki, at University of Tennessee (A. 24);

(2) During the week of August 23, 1976, plaintiffs

obtained permission to be released from their

lease at an apartment owned by Vanderbilt

University. They sought the release in order

to secure less expensive housing (A. 24);

(3) In response to an advertisement, Nikki Harper

telephoned Natchez Village Apartments and

after two conversations obtained an appointment

to view the apartments on September 4, 1976.

Mrs. Harper also provided defendant with some

information in response to a question from

defendant (A. 25);

(4) After viewing a vacant apartment, number 215,

plaintiffs told defendant Hutton they wanted

to rent the apartment. Hutton said that before

he would rent it to them, plaintiffs would

have to fill out an application and a credit

check would have to be run which would take

one week. (A. 25, 27) ;

(5) Defendant inquired about the plaintiffs'

financial status and plaintiffs supplied them

with information, including information about

loans and scholarships they had been granted,

the money they had in the bank, and the money

they expected to earn (A. 25-26);

(6) There was a conflict in testimony concerning

the plaintiffs' lease with Vanderbilt University.

Defendant testified that Mr. Harper told him he

could not rent an apartment because of his

existing lease; Mrs. Harper testified that her

husband said they could be released, but that

he would check to be sure (A. 27);

(7) All during the time plaintiffs were with

defendant, they were attempting to present a

good impression and to convince him that they

could afford the apartment (A. 27);

-3-

(8) On September 7, 1976 Mr. Harper reconfirmed

that he could be released from his lease

with Vanderbilt University (A. 27);

(9) On September 9, 1976 Mr. Harper telephoned

the defendant to find out if their application

had been accepted. Defendant told plaintiff

he had rented the apartment to someone else on

September 6 and that he had hot checked any of

the credit references the Harpers supplied

(A. 27-28) ;

(10) Defendant did not mention he had any other

apartments available although one was (A. 28);

(11) Evidence from white students who previously

rented, or were presently renting apartments

at Natchez Village established that none were

asked questions by defendant about their

financial status, that defendant did not

indicate that he would run credit checks

on them (A. 28-29);

(12) At the time of the hearing there were no blacks

living in Natchez Village; in the past defendant

had rented to a black individual only once (A. 29).

Despite these findings, the Court concluded that

plaintiffs had failed to prove their case (A. 31). The

Court stated that while "it has no doubt that plaintiffs

would have been good tenants," "[d]efendant could make the

business judgment that plaintiffs would not be financially

able to rent an apartment from him." (A.32). The Court

did not consider the fact that Hutton had never told the

plaintiffs he was rejecting them for financial reasons

and dismissed the fact that Hutton had not required financial

information from white applicants, even those who were

students and on scholarship, with the statement that:

"None of the white students were in

the same financial position as plaintiffs;

two students, a family, on loans and

scholarship." (A. 33)

-4-

The Court did not explain why a family of two students

was so different as an application by one student as

to justify such disparate treatment.

The Court also distinguished the fact that a white

tenant, Mr. Campbell, was allowed to rent although

obligated under another lease while plaintiffs were not

on the grounds that Mr. Campbell has rented from the

defendant previously and stated he would be able to break

his lease (A. 33) .

The Court did not make any conclusions of law regard

ing the fact that on September 10, 1976, when the Harpers

reconfirmed they could be released from their other

apartment, Hutton withheld information that an apartment

was available.

Simultaneously with the filing of the Memorandum,

the Court issued an Order dismissing the case (A. 35).

Plaintiffs timely filed their Notice of Appeal on

January 21, 1977 from the District Court's conclusions

of law and dismissal of the complaint.

-5-

Statement of Facts

Defendant Edward M. Hutton has been the sole owner

and manager since 1967 of Natchez Village Apartment, a

fifty-unit complex in Nashville, Tennessee (A. 137,156).

Thirty-four units are efficiency units which rent at

$155.00 per month (A. 96, 138). During the entire ten years

that defendant Hutton has operated Natchez Village, he has

only rented one unit to a black person (A. 154-155),

although blacks comprise approximately 20% of the population

1/in the Nashville area.

Defendant Hutton offered no testimony concerning his

usual application and rental procedure. According to the

undisputed testimony of four white tenants at Natchez

Village, however, Hutton's procedure for approving appli

cants for tenancy, at least white applicants, and executing

leases is quite simple. Hutton makes an appointment with

a prospective tenant to see an available apartment within

hours after the applicant's initial inquiry, and if the

applicant offers to rent the apartment after viewing it',

Hutton immediately produces and executes a lease with the

parson (A. 64,73,81). Although applicants are asked to

list some credit references and bank accounts (A.65,71-2,77,81)

1/ U.S. Bureau of the Census, General Population Statistics,

Tennessee (1970), p. 44-70.

-6-

no information is sought as to amounts of income, assets

or liabilities, nor is any credit check to verify ref

erences required or made prior to signing leases since the

leases are executed on the spot (A. 65,67,68,73,76,81).

Testimony concerning five white applicants revealed

that they all experienced similar application procedures.

Neal S. Fleming, a white male, who was about to enter

Vanderbilt University Law School in the fall, 1974, in

quired about a studio efficiency at the defendant's

Natchez Village Apartment in June, 1974 (A. 62). The day

after viewing an available efficiency he offered to rent

it and made an appointment for the following day to sign

the lease (A. 64). Despite the fact that Mr. Fleming

volunteered that he was a scholarship student (A. 63).

defendant Hutton made no inquiry as to the amount of the

scholarship, nor did he request or obtain any information

about Mr. Fleming's income, assets or liabilities (A. 64).

In response to a request for credit information, Mr. Fleming

only listed Vanderbilt University (A. 65). However,

the defendant did not require that the execution of the

lease be delayed until a credit check was run, did not

ask for further financial references, and the lease was imme

diately signed (A. 65).

A similar procedure was applied to Mr. Robert E. Campbell,

-7-

a white male who was about to enter Vanderbilt University

School of Law, when he sought an efficiency at Natchez Village

in July, 1974 (A. 79). He spoke to the defendant on the

telephone one evening and obtained an appointment to view an

available efficiency on the following day. Mr. Campbell

offered to rent the efficiency and was immediately permitted

to sign a lease (A. 81). Although credit reference informa

tion was requested, no request was made for specific infor

mation on income, assets or liabilities, nor was any such

information volunteered (A. 80-81,159). Defendant Hutton

did not run a credit check prior to approving Campbell as

a tenant and to executing the lease (A. 81).

After residing at the defendant's apartment complex

for some time, Mr. Campbell moved out. At a later date,

after Mr. Campbell was married, he again sought an apartment

from the defendant at Natchez Village Apartments. Again,

the applicant was permitted to execute a lease without

tendering specific financial data and without having to wait

until a credit check was made (A. 81). The second lease

was executed despite the fact that Mr. Campbell was bound

to another apartment house (A. 84, 162).

There was no significant variation in the application

-8-

procedure when, in July of 1976, a white female entering

law school, Ms. Sue D. Sheridon, sought an apartment from

the defendant (A. 66). She saw an efficiency on one day

and on the following day telephoned and offered to rent

it (A. 66-67). An appointment was made for two or three

hours later to sign the lease, and the lease was executed

that same day, July 13, 1976 (A. 67,38-39,51-52). Routine

credit references were provided on the lease such as charge

accounts and bank accounts, all of which were located out

side of the State of Tennessee (A. 67,51-52). No

information on the balances in these bank accounts was

provided nor was there any request for facts as to Ms.

Sheridon's assets, income or liability, and no such information

was volunteered (A. 72,73,159,162). Furthermore, no

mention of a credit check was made nor was any possible

because, as usual, the lease was executed immediately

(A. 67).

The same procedure was followed in the case of the

application of John Billings, a white male who was entering

Vanderbilt University to seek a degree in Chemical Engineering

(A. 153). Mr. Billings first visited the Natchez Village

Apartments on Monday, September 6, 1976, Labor Day, and

immediately offered to rent the apartment number 215, which was

-9-

&n efficiency (A. 138). Mr. Billings was permitted to lease

the efficiency in question that same day. Defendant

Hutton did not delay execution of the lease until he

checked credit references and did not seek any specific

financial data (A. 153,162).

Ms. Jennifer Smart, a white female who was a second

year law student, telephoned defendant Hutton on September

15, 1976 to inquire about renting an efficiency apartment

at Natchez Village (A. 74-75). As with the other white

applicants, Ms. Smart was allowed to view the efficiency

and sign a lease on September 15, 1976, the same day (A. 76).

Although Ms. Smart told Hutton she had a job as a research

assistant and had a bank account with a bank in Nashville,

Hutton asked no questions as to her salary, assets, lia

bilities or other credit references and executed a lease

without verifying the existence of the bank account or

job (A. 75-76) .

The application and rental procedure which had con

sistently been applied to white prospective tenants varied

drastically, however, when plaintiffs, a black married

couple, sought housing at Natchez Village.

Derry Harper, a black male, was entering his first

year at Vanderbilt University School of Law in August,

-10-

1976. His wife, Nikki, who is also black, was in her

last year as a student at the University of Tennessee

(A. 93,122). The Harpers had been assigned an apart

ment in Oxford House, a complex operated by Vanderbilt

University, at a rental cost of $2034.00 for the academic

year, August 22, 1976 to May 13, 1977 (Def. Ex. B, A. 54-55).

The rent for the Oxford House apartment was thus approxi

mately $235.00 per month. Because the Harper's budget was

limited, they decided to seek a less expensive apartment

and before September 1, 1976, they had secured the per

mission of the Vanderbilt University Housing Director to

terminate their lease if they could find suitable alternative

housing (A. 92,105,119,123,132).

In response to the defendant's published advertisement

that a studio efficiency was available at Natchez Village

Apartments, Mrs. Harper called the number listed in the

advertisemtnt on August 31st (A. 95, Pi. Ex. 2). A woman

answered who stated that she was not sure whether an ef

ficiency was available and told Mrs. Harper to call back

later in the week (A. 95 ). When Mrs. Harper did call

back on September 2nd she spoke to the defendant who con

firmed that an efficiency was available for $155 per month

(A. 97). During that conversation she stated that she and

-11-

her husband were students. The defendant then inquired

as to their sources of income and she responded that they

were each receiving scholarship grants and loans (A. 97).

At that time Hutton did not state either that Natchez

Village had a requirement of a minimum income for tenants

or that students living on scholarship funds could not meet

application requirements (A. 96-98). Mrs. Harper requested

an appointment to view the efficiency and the defendant

suggested that she come by two days later on Saturday morn

ing, but to call prior to arriving (A. 98). As agreed,

Mr. Harper called the defendant at 9:00 A.M., that Saturday,

September 4, 1976. Defendant Hutton refused to see them

immediately, but rather told Mr. Harper to call back in

fifteen minutes in order to give the defendant a chance

to see if the efficiency could be viewed (A. 125).

Finally, the plaintiffs were permitted to visit the efficiency

at 10:30 A.M. (A. 125). The efficiency that they viewed

was apartment number 215 (A. 134,138). After inspecting it,

the plaintiffs decided that they wanted to rent the efficiency

and so informed the defendant (A. 100-102,123,149). Rather

than permit the plaintiffs to sign a lease at that time, as

he had allowed white applicants, defendant Hutton ques

tioned the plaintiffs for forty-five minutes about

-12-

their specific income, assets and liabilities. Hutton

permitted the Harpers to fill out an application, but

informed them that he would have to run a credit check

which would take an entire week before proceeding any

further. He also required them to return to Vanderbilt

to verify the fact that they could be released from

their lease at Oxford House (A. 102-120,123,128-133,150-153)

In response to Hutton's qustioning, the Harpers sought to

provide the defendant with all the data that he requested,

including exact amounts and sources of income (A. 150),

although no such information had been sought from other

applicants. Unlike the other applicants, the defendant

also insisted upon a local reference, which the Harpers

immediately provided (A. 131).

The interview concluded upon the understanding that

the Harpers wanted the apartment. They were to call back

on the following Friday, September 10th, to learn the

results of the credit check and to reconfirm that they

were under no obligation to Vanderbilt and could be re

leased from their apartment at Oxford House (A. 118,123,132)

On the first working day following the Harper's visit

to Natchez Village, Tuesday, September 7, 1976, Mr. Harper

complied with defendant Hutton's request and reconfirmed

-13-

with a Vanderbilt official that he could be released from

his lease (A. 87,133). However, when according to

Hutton's instructions, Derry Harper called on September

10 to learn the results of the credit check and whether

he and his wife could sign a lease. Hutton informed him

that the apartment had been rented (A. 134). Although it

was clear that Mr. Harper still wanted an efficiency

apartment at Natchez Village, defendant Hutton only told

Mr. Harper that the apartment he and his wife had viewed

was unavailable and specifically kept from the plaintiff

the fact that another efficiency had just become available

(A. 140-142,157, PI. Ex. 4, 46-49).

At trial it was undisputed by defendant Hutton that

plaintiffs Derry and Nikki Harper could afford to pay the

rent and would have made good tenants (A. 105-114,129,159,43-44).

It was also clear that, despite the objective and admitted

fact that the Harpers are a stable couple whowould have

made good tenants, defendant Hutton had no intention of

ever renting to this black young married couple. At one

point Hutton testified that he did not allow the Harpers

to sign a lease on September 4, 1976, when they first

wanted to do so, because the couple did not give "a clear

indication as to how much money they would have, either

-14-

annually or monthly which would be available for living

2/

expenses, rent, food, etc.," (A. 158). However,

Hutton admitted that he had never asked for such financial

information, let alone in such minute detail, from any

other applicant (A. 161-162). Unlike other appli

cants, the defendant insisted upon a local reference which -

was provided (A. 131).

Moreover, Hutton required the Harpers to wait an

entire week in order to run a credit check on them, although

he admitted that he did not subject white applicants, even

those who were also students, to a credit check nor did

he postpone executing the leases of white applicants until

detailed financial data had been submitted (A. 65,67,68,73,76,81

159-161). Hutton's supposed justification for requiring the credit

check only for the black couple and for no white applicants

was that the credit information supplied by the white

2y Although the Harpers testified that they told Hutton

specific information on the amount of money covered

by scholarships and loans (A. 128-129), Hutton

stated that the information he received was not a

"clear indication" of monthly allotments for "living

expenses, rent, food, etc.,"(A. 158). The district

court found that the Harpers had submitted financial

data (A. 25-26).

-15-

apartment seekers was "far more substantial then the

information which Mr. and Mrs. Harper submitted" (A. 160).

yet, Neal Fleming, a white tenant, testified that he only

told Hutton he was a scholarship student and that the

only credit reference he provided was Vanderbilt University

(A.62-63). in contrast, the Harpers listed a Chevron

credit card as well as Vanderbilt University and supplied

substantial financial data (A. 130).

It became clear that the use of a credit check on a

black applicant was only a ruse to avoid renting to a

black person when Hutton admitted that he had not run the

credit check on the Harpers and, indeed, never intended

to run the check (A. 156,163). Although Hutton testified

that he did not run a credit check because the apartment

the Harpers wanted had already been rented (A. 156).

that excuse simply does not hold up because another ef

ficiency had become available on September 8, 1976.

Hutton received word that a tenant, Miss Shoshid, was

vacating a one-bedroom apartment (A. 140-141).

Hutton knew that a tenant who was then occupying an efficiency

apartment, Miss Sims, wanted the first available one-

bedroom, and "immediately . . . got in touch" with her

"and obligated the [one-bedroom] apartment" (A. 142).

Miss Sim's efficiency apartment was thus available for rent

-16-

as of September 8, 1976. When faced with the bold fact

that he had intentionally refused to inform the Harpers

about the availability of this apartment or to check the

references, Hutton's only reply was that "I wasn't under

any obligation" to call the Harpers or to tell them on

September 10, 1976 that the efficiency was available (A.144).

The efficiency the Harpers viewed was leased to a white

tenant, Mr. Billings, on September 6, 1976 (A. 139-140).

The second efficiency was also leased to a white tenant,

Miss Smart, on September 15, 1976 (A. 139).

Defendant Hutton's other excuse for refusing to rent

an apartment to the Harpers on September 4, 1976 was equally

lame. He testified that he did not want to rent to the

Harpers until they were certain they could be released from

their Oxford House apartment lease (A. 152). On

September 1, 1976, prior to viewing the apartment at

Natchez Village, the Harpers had already secured the per

mission of the Vanderbilt University Housing Director to

terminate their lease if they could find suitable housing

(A. 85-92,105,119,123,132). Nevertheless, Hutton in

sisted that they return to Vanderbilt to verify the fact

that they could be released from their lease (A. 100-120,

123,128-133,150-153). The insistence upon such verification

-17-

was not followed when white applicants were in similar sit

uations. Robert Campbell, a white person, testified that

he was allowed to sign a lease with Hutton despite the

fact that he was bound by another lease at a different

apartment house (A. 84,162). More telling is the fact

that on September 19, 1976, when the Harpers did reconfirm

to Hutton that they could be released from their Vanderbilt

Apartment, Hutton deliberately declined to offer or even

tell them about the availability of a second efficiency in

the apartment complex (A. 144).

As a consequence of the more onerous requirements

imposed on the Harpers, the week-long delay, and the delib

erate refusal to tell them of the availability of an apart

ment, plaintiffs were denied the opportunity, despite

their undisputed qualification, to sign a lease for one

apartment 215 on September 4, 1976 and for Miss Sim's

apartment on September 10, 1976. Both apartments were

rented to white persons and the entire complex remains

all-white (A. 154).

-18-

r

ARGUMENT

I

ON THE BASIS OF THE UNCONTRADICTED

EVIDENCE AND THE FACTS AS FOUND BY

THE DISTRICT COURT, PLAINTIFFS DERRY

AND NIKKI HARPER WERE DENIED HOUSING

AND VICTIMIZED BY UNLAWFUL RACIALLY

DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES.

The factual findings of a district court cannot be

disturbed unless they are clearly erroneous, Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure 52(a). The "clearly erroneous"

standard of review does not apply where, as in the in

stant case, appellate review is sought not as to find

ings of fact, but as to the application of law to those

3/

facts and the ultimate conclusion reached on the merits.

Thus, a review of the ultimate finding of discrimination

under a civil rights statute is not subject to the "clearly

3/ United States v. Senger Mfq. Co., 374 U.S. 174, n. 9

(1963); Stewart v. General Motors Corp.. 542 F.2d 445,

449 (7th Cir. 1976); Senter v. General Motors Corp., 532

F.2d 511, 526 (6th Cir. 1976); Causey v. Ford Motor Co.,

516 F.2d 416, 420-421 (5th Cir. 1975); Nader v. Allegheny

Airline, Inc., 512 F.2d 527, 538-539 (D.C. Cir. 1975);

United States v. Pelzer Realty, 484 F.2d 438, 442 (5th

Cir. 1973) (housing discrimination case).

-19-

erroneous" standard; neither is the weight accorded facts,

issues of burden of proof, or application of the legal

principles embodied in the civil rights laws. Senter v.

General Motors Corp., supra; see Sims v. Sheet Metal Workers

Int. Ass'n, Local 65, 489 F.2d 1023, 1026 (6th Cir. 1973);

United States v. Pelzer Realty, supra; Rowe v. General

Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348, 356 n.15 (5th Cir. 1972). A

review of the undisputed evidence and the facts as found

by the district court establish as a matter of law that

defendant Hutton failed to rebut the prima facie case of

racial discrimination and that plaintiffs Derry and Nikki

Harper were victims of unlawfully discriminatory practices.

In cases involving racial discrimination, this Court

and other courts have heeded the well-recognized principle

that "statistics often tell much and courts listen." State

of Alabama v. United States, 304 F.2d 583 (5th Cir. 1962),

4/

aff'd, 371 U.S. 37 (1962). See United States v. Youritan

Construction Co.. 370 F. Supp 643 (N.D. Cal. 1973).aff1d.

j/ Stewart v. General Motors, supra; Causey v. Ford Motor

Co., supra; see Hester v. Southern Railway Co., 497 F.2d

1374, 1381 (5th Cir. 1974); United States v. Jacksonville

Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418, 423-424 (5th Cir. 1971).

XJU\ U '•O

- 20-

JLjjjy ^-^4-

IdaJ Lih-J-*

" L<jLAU V UHJi.’L+A

Q, (g V<Jr*

30 n "9:

\A'

. t ^ T \dZ>

3̂

*

? v

\

V

509 F.2d 623 (9th Cir. 1975); United States v. Northside

Realty Associates, Inc.. 518 F.2d 884, 888 (5th Cir. 1975);

va Weathers v. Peters Realty Corp., 499 F.2d 1197, 1201-1202

y

(6th Cir, 1974); Williams v. Matthews, 499 F.2d 819, 827

(8th Cir. 1974); United States v. Reddoch, 467 F.2d 897

(5th Cir, 1972). Defendant Hutton was the sole owner and

manager of Natchez Village Apartments in Nashville, Tennessee

' ^^ Xs (A * ^37, 156). During the ten years that he operated the

/xv ̂ ih Vs

" v J S>•J ^

1 t,to a black person only once; at the time that the plaintiffs,

* 5y £

A0 complex which contains fifty units, he rented an apartment

4' ^

£ X »

a black married couple, sought housing at Natchez Village,

% the complex housed not a single black tenant (A. 154-155),

>■o r r

<jf « * '°

although blacks comprise approximately 20% of the population

Vin the Nashville area.

1

\ .

A

% <N

i' v. V

v J

■y

Such statistics, coupled with virtually stipulated evi

dence that a black applicant for a vacant dwelling was sub

jected to standards and procedures more exacting than those

applied to white applicants, constitute a prima facie case

of housing discrimination casting the burden upon a defendant

to come forward with evidence that race was not a factor in

his decision to deny housing. United States v. Youritan

Construction Co., supra, 370 F. Supp. at 649; Williams v.

^ ' <ruMj MXLl X-4 Tir-Matthews, supra, 499 F.2d at 827. ~Zb(_̂uu (

5/ U.S. Bureau of the Census, General Population Statistics

Tennessee (1970), p. 44-70.

■K

X

7

i 34 v

3

Vi7 f DJ/.

LAfl7 /L <M>

-21-

AU-V cu-̂ u a

'*techuJM . " mUrlL/

d

t\0r r

V/ 0 &

p * y ^ o 1 z1 «

^ * £

, ^ ° e’ ^

- AgA \h

»0

Aqq p v ? / * , ?<& (F+'thj'j i&<tJ

. ■ -fc*U- jQ jfaJLuX JU dj -U. iArxA~ cuLLs y p ^ v ^ A o~^—

i/i/ < in pi1)

0U-A^M_ovvuyK # J U ^ o , ajt> JL *-* #-*- /̂ ''n A ^

r l L C ^ L t ^ , CLiA flJ > tl<y Jy -V^xJ-'U. K-JS

Aj j j L ul-cl*^ {i t a. aJc^j •* vaA-lA -L^ fpuA< AJL^-AurwA-' djyyU~p a jLa ^_

fojb^LUuuA^' dJuî cL hi t h M Y 7 ^

<i-» (k 'J P* a t-yy^^p nAJJLAJ fcA

L fijj* ^ ̂ ^ ^ * W * Vtlpt*

, A* J*lU aJLlA

In this case, defendant Hutton twice prevented the

Harpers from renting an apartment by imposing not one,

but a series of burdensome requirements and delaying

tactics which were never imposed on white applicants, and

Hutton made it impossib-le fof plaintiffs to obtain housing

by falsely representing there were no apartments available

when he knew there were.

Plaintiffs Derry and Nikki Harper first attempted to

rent an efficiency apartment, number 215, at Natchez Village

on September 4 (A. 100-102, 134, 138, 149). Defendant

Hutton required them to provide detailed information as to

their financial ability to pay for the apartment, including

exact amount and sources of income, and monthly allotments for

rent, food, and clothing (A. 150, 158). Through defendants'

admission and independent proof it was established that no

detailed showing of financial ability was ever required of

white tenants at Natchez Village (A. 54, 67, 58, 73, 76, 81).

Indeed, the white tenants who testified stated that Hutton asked

for no information at all concerning salary, amount of scholarship

or source of income (A. 64, 67, 68, 73, 76, 81). The Harpers

were also required to furnish a local reference although white

applicants were not asked for one. (A. 64, 67, 73, 131).

Hutton refused to allow the Harpers to sign a lease for

the efficiency on September 4, 1976 when they wished to do so,

and told the Harpers they would have to wait an entire week

before he would tell them if they were acceptable as tenants

(A. 118, 123, 132). This time delay was never imposed on

white applicants, who were allowed to execute a lease

immediately. (A. 64, 73, 81).

Hutton's excuse for the week delay was that he needed to

check the credit references which the Harpers provided (A. 118,

123, 132). No such procedure was indicated or required for

white applicants; no such credit check was ever run on white

applicants. (A 159-161).

Indeed, defendant did more than apply a different

standard for black applicants; he misled them by advising

them that a week was necessary for an investigation in the

face of his clear policy to "under no circumstances . . . hold

apartments." (A. 146)- Clearly defendant's requirement of a

credit check was a "ruse" to avoid renting to a black couple,

for Hutton admitted that he made absolutely no effort to

run the credit check as he had promised. (A. 156, 163).

The only other reason Hutton offered for not renting

to the Harpers was that the plaintiffs were obligated

under a least to Vanderbilt University (A. 152). Hutton

did not testify that he followed any "rule" against renting

to white persons who were obligated under another lease,

and, in fact, the evidence showed otherwise. Hutton im

mediately rented an apartment to Robert Campbell despite

the fact that he too was subject to a pre-existing lease at

the time he applied for and obtained an apartment (A. 84,

162). Indeed, the district court specifically found that

Hutton had not asked for financial information from whites

but required detailed data from the Harpers (A. 25, 28, 29),

that Hutton did not let the Harpers sign a lease immediately

as he had permitted whites to do (A. 27, 28-29); that Hutton

stated to the Harpers that a credit check was required prior

to approval (A. 27); and that Hutton did rent an apartment

to a Campbell, who was white, despite the fact that he was

under a pre-existing lease (A. 28).

Such discriminatory treatment violates the guarantee

assured to the Harpers by 42 U.S.C. § 1982 to enjoy "the

24

same right" to obtain housing as is enjoyed by white

persons. Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S. 409, 413 (1968);

Smith v. Sol D. Adler Realty Co., 436 F.2d 344, 349-

50 (7th Cir. 1971). As the Court of Appeals in

Williams v. Matthews Co., 499 F.2d 819, 826 (8th Cir.

1974) stated:

"Recent cases make clear that

the statutes prohibit all forms

of discrimination, sophisticated

as well as simple-minded, and

thus disparty of treatment be

tween whites and blacks, appli

cation procedures, and tactics

of delay, hindrance and special

treatment must receive short

shrift from the courts."

The "disparity of treatment between blacks and whites,

application procedures, tactics of delay, hindrance

and special treatment" imposed by Hutton on plaintiffs

here deserves no more than the "short shrift" accorded

discrimination by other courts.

Defendant's imposition of stringent financial re

quirements, credit checks and delaying tactics, imposed

6/ See also Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268, 275 (1939);

United States v. Real Estate Development Corp.. 347 F.Supp.

776, 782 (N.D. Miss.1972).

25

on blacks but not on whites, was "inconsistent with any

intent to enforce the policy in a non-discrirainatory way

or indeed to enforce the policy at all except as to plain

tiffs." Williamson v. Hampton Management, 399 F. Supp. 1146,

1148 (N.D. 111. 1972). To force blacks, and not whites to

submit to credit checks is but a veiled attempt to discourage

them from seeking housing and to delay accepting them in

the hope a white applicant would appear, and is disfavored by

the courts. See United States v. Reddoch, 467 F.2d 897 (5th

Cir. 1972). The imposition of all such burdensome and

delaying tactics on blacks and not whites violates the fair

housing laws. Seaton v. Sky Realty Go., 491 F.2d 634, 636

(7th Cir. 1976); United States v. Pelzer Realty, supra, 484

F.2d at 442, 444; United States v. Mintzes, 304 F. Supp. 1305

(D. Md. 1969); Banks v. Perks, 341 F. Supp. 1175 (N.D. Ohio

1972). The conclusion that racial motivation lies behind

such actions is inescapable: the legal effect of statistical

evidence which establishes a virtual absence of blacks, when

reinforced by the total absence of criteria "applied to all

alike" is that race is the only identifiable explanation.

United States v. Real Estate Development Corp, supra, 347

F. Supp. at 782, citing Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Mach.

Co., 457 F .2d 1377, 1388 (4th Cir. 1972). As the court in

26

United States v. Youritan Construction Co., supra, 370

F. Supp. 648 explicitly held:

"[A]11 practices which have the effect of

denying dwellings on prohibited grounds

are . . . unlawful . . . . The imposition

of more burdensome application procedures,

of delaying tactics, and of various forms

of discouragement by resident managers and

rental agents constitutes a violation of

Section 3604(a) [of the Fair Housing Act

of 1968]."

While Hutton's disparate treatment of the Harpers

when they first applied for an efficiency apartment on

September 4, 1976, was explainable on no other ground but

racial discrimination, his behavior on September 10, 1976,

when he next spoke to the Harpers, left no doubt whatso

ever that he had no intention of renting to the black couple.

When Derry Harper called the defendant on September 10,

1976 to learn the results of the credit check and to re

confirm that he and his wife could be released from their

lease with Vanderbilt University, Hutton told him that he

had not run the credit check (A. 134). Although Hutton

testified that he did not check Harper's references

because the efficiency apartment the Harpers wished to

rent had been leased two days before (A. 156)

2 7

Hutton deliberately withheld the fact that another efficiency

1/

apartment had become available on September 8, 1976 (A. 142).

Any conceivable justification for imposing the requirement

only on blacks dissipates in the face of Hutton's failure to run

the check at all and to inform the Harpers of the availability

of Miss Sims' e f f i c i e n c y Elazar v. Wright, Prentice-Hall Equal

Opportunity in Housing §15, 197 (S.D. Ohio 1976) .

When plaintiffs in a housing discrimination case establish

a prima facie case of discrimination, a defendant cannot rebut

that showing by any excuse whatsoever; he must come forward with a

legitimate justification for his conduct. Proof by a defendant of

a "legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason" can only be based on a

showing that conditions imposed and procedures utilized were

accurately and uniformly applied, and were objectively determin

able. Defendant Hutton-did not make such a showing.

7/ On September 8, 1976 Hutton had learned that a tenant,

Ms. Shoshid, was vacating a one-bedroon apartment (A. 140-141).

He. knew that a tenant who was then occupying an efficiency,

Miss Sims, wanted a one-bedroon apartment, and "immediately...

got in touch" with her "and obligated the [one bedroom]

apartment." (A. 142). Miss Sims efficiency was thus available

for rent as of September 8, 1976 (A. 142) . The district court

so found (A. 28).

28

Mere denial by a defendant that his refusal to rent is not

racially motivated (A. 158) .cannot serve, by itself, to rebut

a prima facie case since "most persons will [no longer] admit

publicly that they entertain any bias or prejudice against

8/

members of the Negro race" and most often they will "cloak and

9/

conceal" such unlawful discriminatory conduct. For this reason,

many findings of racial discrimination in housing turn on proof

10/

circumstantially demonstrating the unlawful conduct.

The proof established that plaintiffs had been treated

unlike white applicants, and it was incumbent upon the

defendant to come forward with proof that he had imposed such

8/ Dailey v. City of Lawton. 296 F. Supp. 266, 268 (W.D. Okla.

1969), aff'd, 425 F.2d 1038 (10th Cir. 1970); United States v .

Real Estate Development Corp., id.

9/ Haythe v. Decker Realty, supra, 468 F.2d at 338.

10/ United States v. Youritan Construction Co., supra; Williams

v. Matthews, supra; Smith v. Sol Adler Realty, supra, United

States v. Reddoch, supra, United States v. West Peachtree Tenth

Corp., supra; Dailey v. City of Lawton, supra; United States v .

Real Estate Development Corp., supra, 347 F. Supp. at 784.

29

requirements on other white applicants. Stated another way,

defendant could only rebut plaintiffs1 prima facie case with clear

proof that white tenants or applicants were subjected to the

requiremtnts and delays imposed on the Harpers.

The district court stated that it had "no doubt that

plaintiffs would have made good tenants" but nevertheless con

cluded that "Defendant could make the business judgment that

plaintiffs would not be financially able to rent an apartment

from him" (A. 32) .

We respectfully submit that the district court's conclusion

misses the issue: although it is of course true that a landlord

may apply sound judgment in his business decisions and consider

an applicant's income and resources, the fair housing laws

mandate that judgment as to financial ability be based on

objective facts and be applied to all alike. As the Court in

United States v. Youritan Construction Co., supra, 370 F. Supp.

at 649-650, held:

"Just as vague and undefined employment

standards which result in whites, but

not blacks being hired are unlawfully

discriminatory, so too are arbitrary and

uncontrolled apartment rental procedures

which produce otherwise unexplained

racially discriminatory results. See Brown

v. Gaston Dyeing Co., 457 F.2d 1377,

1383 (7th Cir. 1972), cert, denied.. 409

U.S. 982 (employment.)"

11/

Accord., Williams v. Matthews, supra.

1 1 / The use of subjective criteria to substantive business judg

ments in race matters have been uniformly rejected in other

areas of civil rights. - 30 - (CONTINUED)

The need for objective criteria ss opposed to subjective judgment

is clear:

" [P] procedures which depend almost entirely

upon the subjective evaluation . . . are

a ready mechanism for discrimination

against Blacks." Rowe v. General Motors

Corp., supra.

The facts in this case are clear proof of the ease with which

non-objective standards may be to disguise racial discrimination.

Hutton had no objective standard to justify the imposition of a

credit check and detailed financial data in the case of black

applicants but not whites. He only testified that the credit in

formation given by whites "was far more substantial from an

economic standpoint (A. 160). The facts prove otherwise: Neil

Fleming, a white tenant, told Hutton he was a scholarship student

and only offered Vanderbilt University as a credit reference

(A. 62-63). Four other applicants were students as well (A. 62,

74,75,79, 153), yet, Hutton required no actual showing of financ

ial ability from them.

11/ (CONTINUED) Selection procedures too heavily dependent on

subjective evaluations violate the right to equal employment

opportunity under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Sen ter v. General Motors Corp., 532 F.2d 511, 529 (6th Cir. 1976)

Ropers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340, 1345 (8th Cir.

1975); Baxter Vo Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., 495 F.2d 437, 444

n. 3 (5th Cir. 1974); Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494

F.2d 211, 214 (5th Cir. 1974); United States v. N. L. Industries.

479 F.2d 354, 368 (8th Cir. 1973); Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing

Mach. Co., supra, 457 F.2d at 1382-1383 (4th Cir. 1972); Rowe v.

General Motors Corp., 487 F.2d 348, 359 (5th Cir. 1972). See also

Singleton v. Jackson Mun. Sep. School District., 419 F.2d 1211

(5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 1032 (1971) (hiring and

firing of teachers in systems undergoing desegregation process)/

(CONTINUED) - 31 -

The failure to have an objective business standard of, for

example, two credit references or a minimum amount of available

income, enabled Hutton subjectively to vary requirements, impose

12/

delays and to maintain an all-white apartment complex. Where

objective standards are uniformly applied to substantiate a

business judgment, that standard can be applied without discrim

ination. See Boyd v. Lefrak Ore., 509 F.2d 1110, 1114 (2nd Cir.

1975), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 895 (1975); United States v .

Aubinoe, Prentice-Hall Equal Opp. in Housing, 515,206 (D. Md.

1977); Harper v. Union Savings Association, Prentice-Hall

Equal Opportunity in Housing 515, 203 (W.D. Ohio 1977) . Without

such a standard, blacks who objectively can afford an apartment

can be all too readily put off and frustrated in their right to

equal housing opportunity. In this very case, Hutton himself

11/ (CONTINUED) Smith v. Concordia Parish Sch. Bd., 445 F.2d 285

(5th Cir. 1971) (reduction of staff in school desegregation

process).

12/ The district court incorrectly declined to draw the inference

that the failure to apply requirements equally was indicative of

racial discrimination on the belief that none of the white

students were in the exact financial position of plaintiffs

(A. 33). Of course, no two applicants are ever identical. It is

precisely for this reason, however, that the requirement of

objective standards must be imposed: a landlord, like Hutton, may

otherwise all too easily cite slight differentiations between

individuals as an excuse for refusing to rent to blacks. Moreover,

Hutton could not have compared the prospective tenants at all,

since he had no financial data from many white applicants.

- 32

admitted that the Harpers objectively met the financial standards

for renting his apartment (A. 159).

The defendant also alleged that he would not lease to indivi

duals under a current lease obligation (A. 152) and gave this as

an excuse for not renting to the plaintiffs on September 4, 1976

(A. 152), This excuse is untenable for three reasons.

First, the defendant did not apply this requirement uniformly; he

rented an apartment to a white applicant, Mr. Campbell, even though

he knew that Mr. Campbell had to make arrangements to be released

13/

from an existing lease. Second, it is clear from the testimony

of the plaintiffs and the Director of Housing at Vanderbilt

University, Dean K. C. Potter, that the plaintiffs had obtained

permission to terminate their lease with Vanderbilt and that this

was communicated to the defendant on September 4, 1976 (A. 92,

105, 119, 123, 132) . Third, if any doubt existed at all about

the obligation under the Vanderbilt lease, this issue was

completely removed from the case by September 10, 1976, when the

plaintiff called to pursue his application for an apartment after

the week's delay that the defendant demanded (A. 156). The

13/ The Court noted that there was no evidence as to whether any

other person applied for Campbell's apartment while he was in the

process of breaking his lease (A. 33). However, it would have

been impossible for other persons to have applied, since 'Campbell

rented the apartment immediately (A. 81).

33

defendant clearly did not have this third excuse available on

this date when he withheld information about an available

apartment. (A. 144).

14/ 15/ 16/

As this Court, other circuit courts, and the Supreme Court

have recognized, the fair housing laws are the critical vehicle

for removing the scourge of slavery and for securing the equal

right to rent housing for all persons, whatever the color of

their skin. The Congressional mandate to prohibit all racial

discrimination - overt, or subtle - can be all too readily

subverted if subjective, arbitrarily applied treatment of

applicants is allowed to rebut prima facie proof of discrimina

tion. United States v. Youritan Construction Co., supra;

Williams v. Matthews, supra; see United States v. West Peachtree

Tenth Corp.. supra. 437 F.2d at 228; compare Boyd v. Lefrak.

supra. (specific objective criteria uniformly applied).

14/ Weathers v. Peter Realty, supra.

15/ Zuch v. Hussey. 394 F. Supp. 1028 (E.D. Mich. 1975), aff1d,

547 F.2d 1168 (6th Cir. 1977); United States v, Youritan

Construction Co., supra; Williams v. Matthews Co., supra; United

States v. Pelzer Realty, supra.

16/ Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co.. 409 U.S. 205

(1972); Jones v. Mayer, supra.

34

II

DEFENDANT'S DELIBERATE FAILURE TO TELL

THE HARPERS OF THE AVAILABILITY OF AN

EFFICIENCY APARTMENT ON SEPTEMBER 10,

1976 VIOLATES THE PLAINTIFFS' RIGHTS

UNDER THE FAIR HOUSING LAW.

Section 804 of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, 42

U.S.C. § 3604(d) specifically provides: .

"[I]t shall be unlawful—

(d) To represent to any person because

of race, color, religion, sex, or na

tional origin that any dwelling is not

available for inspection, sale, or

rental when such dwelling is in fact so

available."

On September 4, 1976, when the Harpers first sought

an efficiency apartment at Natchez Village, Hutton required

them to wait one week allegedly so that he could check their

credit references (A. 152). On September 8, two days before

the Harpers telephoned Hutton to learn the results of the

credit check, another efficiency apartment became available

(A. 140-142). Indeed, the district court found:

"On September 8, defendant was informed

by one of his tenants, Ms. Norma Shoshid,

that she was breaking her lease, and would

be vacating her one bedroom apartment by

Sepetmber 30. (Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 4.)

Defendant rented the one bedroom apartment

to a Miss Sims, who was then renting an

efficiency apartment from defendant. This

efficiency was subsequently rented by Ms.

Jennifer Smart [a white person] on September

15" (A. 28) .

35

It is undisputed that when the Harpers telephoned

Hutton on September 10, he did not tell them of the

availability of Miss Sims' efficiency (A. 140, 144).

Hutton testified at one point that when the Harpers

asked about "going ahead," he told them the apartment

"had already been leased" (A. 156). At two other times,

Hutton testified that on"Friday the 10th . . . I didn't

have anything available" (A. 140, 161), despite the doc

umentary proof and the court's findings to the contrary

(pi. Ex. 4, A. 46-49, 28). He also testified, in response

to a specific question from the district court, that

Derry Harper did not specifically ask if he had any other

apartments available (A. 144).

The district court did not refer to all of Hutton's

testimony on this point but only stated:

Defendant testified that he did not

mention that the efficiency was avail

able to Mr. Harper when Mr. Harper

called on September 10 because Mr.

Harper did not ask him whether he had

any other apartments available for

rent (A. 29) .

The district court erred in not concluding as a matter of

law that defendant's failure to inform the Harpers of the

availability of the second efficiency was a violation of

of 42 U.S.C. § 3604(d). United States v. Youritan

36

Construction Co., supra. 370 F. Supp. at 650-652; United

States v. West Peachtree Tenth Corp., 437 F.2d 221, 226

(5th Cir. 1971); Todd v. Lutz. Prentice-Hall Equal

Opportunity in Housing § 13,787 (W.D. Penn. 1976); accord,

12/Elazar v. Wright, supra.

Hutton's testimony that he did not inform the Harpers

of the availability of the Sims' efficiency because they

did not specifically ask is patently unconvincing. When a

person seeks a particular type of apartment in a complex,

like an efficiency, it is obvious that he or she wishes to

see all such units. Hutton's deliberate decision to with

hold the fact that another efficiency was available is

"inconsistent with commonsense or the ordinary business

IB/

practices" of a manager who is attempting to maintain his

complex at full occupancy. Hutton's opinion that he did not

have to show black apartment seekers "everything" is a

17/ Hutton's failure also violated Section 604(a) of the

Act which provides:

"[I]t shall be unlawful—

(a) to refuse to sell or rent after the making of

a bona fide offer, or to refuse to negotiate for

the sale or rental of, or otherwise to make unavail

able or deny, a dwelling to any person because of

race, rolor, religion, sex, or national origin

(emphasis added).

18/ United States v. Pelzer. supra, 494 F.2d at 446.

37

violation of the fair housing laws. Johnson v. Jerry Pals

Real Estate, 485 F.2d 528, 530 (7th Cir. 1973). As the

court in Johnson, id, stated, to permit defendant to avoid

renting to blacks by such methods

"... would be to encourage real

estate agents to use such an arti

fice to avoid selling it properties

to blacks, despite the clear con

gressional mandate to the contrary.

See Jones v. Mayer. 392 U.S. 409,

447-449 (1968); Smith v. Adler, 436

F .2d 344, 349-350 (7th Cir. 1970);

Haythe v. Decker. 468 F.2d 336, 338

(7th Cir. 1972); United States v.

Real Estate Development Corp., 347

F. Supp. 776, .781-783 (N.D. Miss.

197 2) ."

38