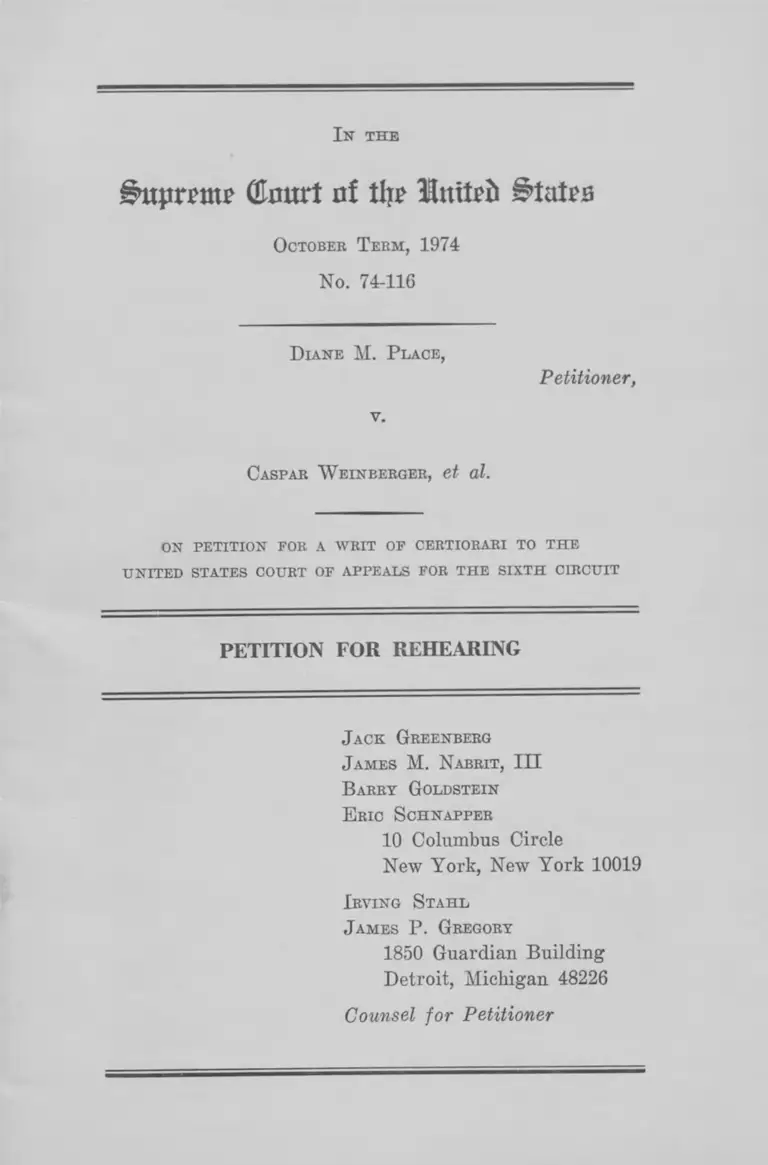

Place v. Weinberger Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Place v. Weinberger Petition for Rehearing, 1974. 7f0dca62-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f171d5a9-15ad-4fcb-862d-cec5ff1b8be4/place-v-weinberger-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

In the

jiuprm? ©curt nf tl|p llttUpfc States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1974

No. 74-116

D i a n e M. P l a c e ,

Petitioner,

v.

C a s p a r W e in b e r g e r , et al.

ON PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E

U N ITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR TH E SIXTH CIRCUIT

PETITION FOR REHEARING

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m e s M. N a b r it , III

B a r r y G o l d s t e in

E r ic S c h n a p p e r

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

I r v i n g S t a h l

J a m e s P . G r e g o r y

1850 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Counsel for Petitioner

In the

Supreme dmtrt nf % luitpfi States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1974

No. 74-116

D i a n e M. P l a c e ,

v.

Petitioner,

C a s p a r W e in b e r g e r , et al.

ON PETITION EOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E

U N ITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR TH E SIXTH CIRCUIT

PETITION FOR REHEARING

The Petitioner herein respectfully moves this Court for

an order vacating its denial of the Petition for Writ of

Certiorari, entered on November 25, 1974, and granting

the petition. This petition for a rehearing is founded upon

the decision of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in

Brown v. General Services Administration (No. 73-2628)

(November 21, 1974), pp. la-17a, Petition For Writ of

Certiorari filed December , 1974, No. 74- }

1 Counsel were notified by telephone of the decision in Brown

in the late afternoon of Thursday, November 21, 1974, and ob

tained a copy of the decision in the afternoon of Friday, Novem

ber 22, 1974. The instant Petition For W rit of Certiorari was

considered at the conference of Friday, November 22, 1974, the

result of which was announced on Monday, November 25, 1974.

Under the circumstances Petitioner, of course, had no opportunity

to bring this development to the attention of the Court prior to

the denial of Certiorari.

2

The instant case presents the question, inter alia, whether

the new remedies of section 717 of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act, as amended, apply to discrimination occurring prior

to March 24, 1972, the date on which that section became

law. Section 717, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16, authorizes the dis

trict courts to provide to federal employees aggrieved by

discrimination on the basis of race or sex the same rem

edies available to employees of private employers. There

is a conflict among the courts of appeals on this question;

three circuits have concluded that section 717 is applic

able to discrimination occurring before March 24, 1972,

and one circuit, in the instant case, has concluded that it

is not. On November 25, 1974, this Court denied the

Petition For Writ of Certiorari, Justices Stewart, White

and Douglas voting to grant the writ. Whenever a fed

eral employee has sought to assert federal jurisdiction

under section 717 to remedy such discrimination, the gov

ernment, in three circuits and at least twenty-four dis

trict courts, including the instant case, has opposed judicial

scrutiny of such claims of discrimination by arguing that

section 717 does not apply to discrimination occurring be

fore March 24, 1972.

In Brown v. General Services Administration the gov

ernment successfully advanced the opposite contention in

preventing judicial scrutiny of Mr. Brown’s claims; in

the Second Circuit the government contended that sec

tion 717 does apply to discrimination occurring before

March 24, 1972. The government there urged that sec

tion 717 had repealed a variety of statutes on which plain

tiff founded his cause of action. Since the discrimination

of which plaintiff complained had occurred prior to March

24, 1972, the government argued that section 717, and

thus the repeal, applied to such discrimination occurring

before the effective date of the section 717.

3

The Second Circuit, in holding at the instance of the

government that section 717 applied to discrimination be

fore its effective date, expressly rejected the contrary

conclusion reached by the Sixth Circuit, also at the urging

of the government, in this very case.

In light of Bradley, we cannot agree with the Sixth

Circuit’s holding in Place v. Weinberger, supra, that

Congress by its silence as to all sections of the Act

except one intended the other sections to have pro

spective application only.2

At oral argument in Brown, the government expressly

relied on Roger v. Ball, 497 F.2d 702 (4th Cir. 1974) and

urged that this Court’s decision in Bradley v. School Board

of the City of Richmond, 40 L.Ed 2d 476 (1974), dictated

that section 717 be applied to discrimination occurring

prior to March 24, 1974. In the instant case petitioner

advanced the identical argument3 but the government re

fused to acknowledge its correctness.

That the government advanced inconsistent positions

in these two cases was not the result of inadvertence. In

Brown the government, in stating its assumption that sec

tion 717 applied to discrimination occurring before March

24, 1972, conceded the government “has argued differently”

in other cases.4 * The Solicitor General was also made

aware of the inconsistent position being taken by the

government in different circuits.6 Had the Solicitor Gen

eral, in response to the Petition in this case, taken a

definitive position as to whether or not the government

maintained the decision of the Sixth Circuit was correct,

2 P. 11a.

3 Petition for W rit of Certiorari, No. 74-116, pp. 17-19.

4 Brief for Defendants-Appellees No. 73-2628, 2d Cir., p. 6 n.

6 See Petition for W rit of Certiorari, p. 19.

4

uniformity in the position of the government in other

case might have resulted. Instead, the Solicitor opposed

Certiorari solely on the ground that the decision below

was unimportant, thus avoiding committing the govern

ment to one position or the other.6

It has long been a precept of Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence,

at least since Lord Mansfield’s opinion in Montefiori v.

Montefiori, 25 K.B. 203 (1762), that a party must not be

permitted to advance inconsistent positions in judicial

proceedings. See, e.g. Story’s Equity Jurisprudence, 14th

ed., § 2020.7 The rule prevents a party from encouraging

the growth of conflicts among the courts by seeking to

win two inconsistent decisions where consistency would

preclude him from winning more than one. “ Such use of

inconsistent positions would most flagrantly exemplify

that playing ‘fast and loose with the courts’ which has

been emphasized as an evil the courts will not tolerate.

. . . And this is more than an affront to judicial dignity.

For intentional self-contradiction is being used as a means

of obtaining unfair advantage in a forum provided for

suitors seeking justice.” Scarano v. Central R. Co. of New

Jersey, 203 F.2d 510, 513 (3d Cir. 1953).

This Court has applied that principle in a variety of

cases. In Callanan Road Co. v. United States, 345 U.S.

507 (1953), this Court refused to permit the holder of a

certificate of convenience and necessity to collaterally

attack the provisions of its certificate. The Court noted

that, in obtaining its certificate, the holder had earlier

6 Memorandum for the Respondents in Opposition, pp. 2-4.

7 See also IB Moore’s Federal Practice, jf 0 .4 0 5 [8 ]; Note, 59

Harv. L.Rev. 1132 (1 9 4 6 ): Note, “ Estoppel Against Inconsistent

Positions in Judicial Proceedings” , 9 Brooklyn L. Rev. 245 (1940);

Note, 1 Tenn. L.Rev. 1 (1922). The principle was expressed by

Lord Kenyon in the maxim, “Allegans contraria non est audiendus” .

5

argued before the Interstate Commerce Commission that

the provisions of such certificates were not subject to

collateral attack. This Court held that “ [t]he appellant

cannot blow hot and cold and take now a position con

trary to that taken in the proceedings it invoked to obtain

the Commission’s approval.” 345 U.S. at 513. In Davis v.

Wakelee, 156 U.S. 680 (1895), Wakelee had obtained a

final state court judgment against Davis on certain notes

following service by publication. When Wakelee sought

to assert the underlying claim in a bankruptcy action, the

bankrupt Davis successfully argued that Wakelee need

not, and thus could not, do so since the claim had already

been reduced to a valid final judgment and was not dis

chargeable. Thereafter Davis moved to set aside the

original judgment on the ground that service by publica

tion was unconstitutional, relying on Penvoyer v. Neff, 95

U.S. 714 (1878). This Court forbade Davis from main

taining such an inconsistent position as to the legality of

service and the validity of the resulting judgment. 156

U.S. at 689-691.8 See also Philadelphia R.R. Co. v. How

ard, 54 U.S. (14 How) 307 (1851), Ohio R.R. Co. v. Mc

Carthy, 96 U.S. 258 (1878).

These principles apply a fortiori when the party seeking

to advance inconsistent positions is the government. A

private party has an interest in winning an action regard

less of the arguments or maneuvers it may use. The gov

ernment’s overriding interest is that justice should be

8 “It may be laid down as a general proposition that, where a

party assumes a certain position in a legal proceeding, and suc

ceeds in maintaining that position, he may not thereafter, simply

because his interests have changed, assume a contrary position

. . . It is contrary to the first principles of justice that a man

should obtain an advantage over his adversary by asserting and

relying upon the validity of a judgment against himself, and in

a subsequent proceeding upon such judgment, claim it was ren

dered without personal service upon him.”

6

done; so long as that occurs the government has won,

regardless of whether a particular defendant goes free

or a civil litigant obtains injunctive or monetary relief.

Berger v. United States, 295 U.S. 78, 88 (1935). Six cir

cuits considering this question have all held that the

government may not advance inconsistent positions.9 As

the Second Circuit pointed out in Staten Island Hygeia

Ice Co. v. United States, 85 F.2d 68, 72 (1936), “ [tjhere

is nothing in the nature of sovereignty or in the recog

nized prerogatives of the sovereign that would allow the

government to take and keep a right without the accom

panying burden” .

The due administration of justice would be materially

advanced by requiring the Solicitor General to respond

to this Petition For Rehearing and to state definitively

whether the government maintains that section 717 does

or does not apply to discrimination occurring prior to

March 24, 1974. I f the Solicitor General adheres to the

government’s position in Brown, the instant case can be

summarily reversed.10 If the Solicitor General adheres to

the government’s position in the Sixth Circuit, the issues

presented by the pending Petition for Writ of Certiorari

in Brown will be substantially simplified, and the neces

sity for a grant of certiorari in the instant case, in view

of the new and conflicting decision of yet another court

9 Goodman v. Public Service Commission, 467 F.2d 375 (D.C.

Cir. 1972) ; United States v. Fox Lake State Bank, 366 F.2d 962,

965-66 (7th Cir. 1966); Vestal v. C.I.R., 152 F.2d 132 (D.C.Cir.

194 5 ); Eichelberger & Co. v. C.I.B., 88 F.2d 874 (5th Cir. 1937);

United States v. Brown, 86 F.2d 798 (6th Cir. 1936); Staten

Island Hygeia Ice Co. v. United States, 85 F.2d 68 (2d Cir. 1936);

United States v. Denver, etc., B.R., 16 F.2d 374, 376 (8th Cir.

1926).

10 See, regarding the effect of such confessions of error Urrutia

v. United States, 357 U.S. 577 (1 9 5 8 ); Howard v. United States,

356 U.S. 25 (1958).

7

of appeals, will be manifest. Compare Sanitary Refrigera

tor Co. v. Winters, 280 U.S. 30, 34 n. (1929). Directing

the Solicitor General to submit such a response is the

most expeditious manner of precluding the government

from continuing to advance different positions in different

courts of appeal.

The inconsistent positions taken by the respondents

doubtless reflect a good faith belief by the Department

of Justice that it would be extremely undesirable to

permit inquiry into claims that federal officials are

breaking the law by discriminating on the basis of race

or sex. But the national policy in this regard is to be

made, not by lawyers in the executive branch, but by

Congress. It was Congress which prohibited such discrim

ination in 1957. And it was Congress which, over the

objections of the executive branch, mandated such judicial

scrutiny in 1972. The issue presented by this case is the

extent to which attorneys within the Department of Jus

tice can thwart or delay implementation of congressional

policy by asserting whichever of two inconsistent theories

will, in any. particular case, prevent aggrieved employees

from obtaining a judicial remedy. It is the very essence

of a government of laws that there should be, in a case

such as this, but one rule, uniform and invariable, ap

plied to all citizens, regardless of whether, in some in

stances, the result of that application may be displeasing

to the men who chance to hold public office. United States

v. United Mine Workers, 330 U.S. 258, 307-08 (1947)

(Frankfurter, J. concurring). The ultimate responsibility

for vindicating that principle is imposed by the Constitu

tion on this Court.

8

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, as well as those contained in

the Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Petitioner prays that

this Court direct the Solicitor General to respond to this

Petition for Rehearing, and that the Court thereafter

grant rehearing of the order of denial, vacate that order,

grant the petition and review the judgment and opinion

below.

Respectfully submitted,

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m e s M. N a b r it , III

B a r r y G o l d s t e in

E r ic S c h n a p p e r

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

I r v in g S t a h l

J a m e s P. G r e g o r y

1850 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Counsel for Petitioner

9

Certificate of Counsel

As counsel for petitioner, I hereby certify that this

Petition for Rehearing is presented in good faith and not

for delay and is restricted to the grounds specified in Rule

58(2).

Counsel for Petitioner

APPENDIX

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Second Circuit

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F or the Second Circuit

No. 935— September Term, 1973.

(Argued June 14, 1974 Decided November 21, 1974.)

Docket No. 73-2628

Clarence B rown,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

G e n e r a l S e r v ic e s A d m i n i s t r a t i o n , U n it e d S t a t e s o f A m e r

i c a , T r a n s p o r t a t io n a n d C o m m u n i c a t i o n s S e r v ic e ,

C o m m u n i c a t i o n s D i v is i o n , R e g io n 2 , J o s e p h A . D a l y ,

Regional Director, Transportation and Communications

Service, A l b e r t G a l l o , Chief, Communications Division

and F r a n k A. L a p o l l a , Acting Chief, Communications

Division, Transportation and Communications Service,

Region 2,

Defendants-Appellees.

B e f o r e :

L umbard, H ays and T imbers,

Circuit Judges.

Appeal from judgment entered in the Southern District

of New York, Lloyd F. MacMahon, District Judge, dismiss

ing a complaint which alleged racially discriminatory em-

la

2a

ployment practices on the part of an agency and officials

of the federal government.

Affirmed.

E eic S c h n a p p e r , New York, N.Y. (Jeff Greenup,

Jack Greenberg, James M. Nabrit, III,

Johnny J. Butler, Joseph P. Hudson and

Greenup & Miller, New York, N.Y., on the

brief), for Plaintiff-Appellant.

C h a r l e s F r a n k l i n R i c h t e r , Asst. U.S. Atty.,

New York, N.Y. (Paul J. Curran, TJ.S. Atty.,

and Gerald A. Rosenberg, Asst. U.S. Atty.,

New York, N.Y., on the brief), for Defen

dants-Appellees.

T i m b e r s , Circuit Judge:

This appeal from a judgment entered September 28,

1973 in the Southern District of New York, Lloyd F. Mac-

Mahon, District Judge, dismissing the complaint in an ac

tion brought against an agency and officials of the federal

government to redress alleged racially discriminatory em

ployment practices presents the questions (1) whether

Section 717(c) of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 19721 applies retroactively to claims arising before its

1 Section 717(c) o f the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972

as codified in 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16(c) (Supp. I I 1972), provides in

pertinent part:

“Within thirty days o f receipt o f notice o f final action taken by

[an] . . . agency, or by the Civil Service Commission upon an appeal

from a decision or order of such . . . agency . . . on a complaint of

discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin,

brought pursuant to subsection (a ) o f this section, Executive Order

11478 or any succeeding Executive orders, or after one hundred

3a

enactment; (2) whether the statute pre-empts any other

federal jurisdictional basis for appellant’s claim; and (3)

whether in any event appellant has failed to exhaust ad

ministrative remedies. We hold that each of these ques

tions must be answered in the affirmative. We affirm.

I. F acts

Appellant Clarence Brown, a black, has been employed

by the General Services Administration (GSA) Regional

Office No. 2 (New York City) since 1957. He has not been

promoted since 1966. His current job classification is

Communications Specialist, GS-7, Telecommunications

Division, Automated Data Telecommunications Service.

In December 1970, Brown was referred for promotion

to GS-9 by his supervisors along with two white employees,

Ownbey and Trost. All three were rated “ highly qualified” .

Trost was the only one promoted. Brown filed an admin

istrative complaint of racial discrimination with the GSA

Equal Employment Opportunity Office. The complaint was

withdrawn, however, after Brown was told that further

promotions would soon be available and that he had been

denied promotion because of lack of the requisite “voice

experience” .

Brown claims that he thereafter acquired full “ voice

experience” . In June 1971, another GS-9 promotional op

portunity opened. Brown and Ownbey again were rated

“highly qualified” for the opening. A third white employee

also was available. Ownbey was chosen.

and eighty days from the filing o f the initial charge with the . . .

agency . . . or with the Civil Service Commission on appeal from

a decision or order o f such . . . agency . . . until such time as

final action may be taken by [an] . . . agency, . . . an employee

. . . i f aggrieved by the final disposition o f his complaint, or by

the failure to take final action on his complaint, may file a civil

action as provided in section 2000e-5 of this title, in which civil

action the head of the . . . agency, . . . shall be the defendant.”

4a

On July 15, 1971, Brown filed a second administrative

complaint with the GSA Equal Employment Opportunity

Office, claiming racial discrimination in the denial of his

promotion. An investigative report was prepared. After

review, the GSA Regional Administrator determined that

there was no evidence of racial discrimination and so in

formed Brown by letter dated October 19, 1972. This letter

also informed Brown that he could request a hearing on

his complaint within seven days; but that if he did not

make such a request, the determination would become the

final agency decision and he would then have the right to

appeal the GSA’s decision to the Board of Appeals and

Review of the Civil Service Commission (CSC), or to file

a civil action in the federal district court within 30 days.

Brown requested a hearing. It was held on December

13, 1972 before a complaints examiner of the CSC. Brown

was represented by counsel. On February 9, 1973, the com

plaints examiner issued his findings and recommended de

cision. He found no evidence of discrimination and recom

mended that no action be taken on the basis of the com

plaint.

By letter dated March 23, 1973, received by Brown on

March 26, the GSA Director of Civil Rights rendered the

final agency decision that the evidence did not support the

complaint of racial discrimination. The letter, pursuant to

regulations, included a copy of the transcript of the hear

ing and of the findings and recommended decision of the

complaints examiner. The letter also advised Brown of his

options: (1) to file an appeal with the Board of Appeals

and Review of the CSC within 15 days after receipt of

the letter, in which case he could commence a civil action

in the federal district court within 30 days after receipt

of the Board’s decision or 180 days after filing the appeal

if no decision had been rendered; or (2) to commence a

5a

civil action in the federal district court within 30 days after

receipt of the letter.2

Brown did not file an appeal with the Board. Instead,

he commenced the instant action in the district court on

May 7, 1973—more than 30 days after receipt of the letter.

His complaint named as defendants the GSA and Brown’s

superiors, Joseph A. Daly, Albert Gallo and Frank A.

Lapolla.

Basically, Brown’s complaint alleges that he has been

denied promotions because of his race.3 Apparently he

seeks a promotion to Communications Assistant, GS-9, a

supervisory position, and appropriate back pay, although

some reference is made in his brief to damages based on

discrimination.

The original complaint alleged jurisdiction under Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e

et seq. (1970); Section 717 of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 (Supp. II

1972); 28 U.S.C. §1331 (1970); and the Declaratory Judg

ment Act, 28 U.S.C. §§2201-02 (1970). The complaint also

sought to invoke jurisdiction to secure protection of and

redress deprivation of rights secured by 42 U.S.C. §§2000e

et seq. (1970) and 42 U.S.C. §1981 (1970). The complaint

demanded “ such relief as may be appropriate, including

injunctive orders, damages, costs, attorney’s fees and back

pay.” 4

2 The provisions for civil actions are set forth in Section 717(c) of

the Equal Employment Opportunity Act, 42 U.S.C. $2000e-16(c) (Supp.

I I 1972). See note 1 supra.

3 The position of the GSA is that Brown is a somewhat uncooperative

employee and therefore has not been promoted. The substantive dispute,

however, is not before us on this appeal. Our decision is limited to the

threshold jurisdictional questions presented.

4 Belief available under Title V II and the regulations promulgated

thereunder would include retroactive promotion with back pay and at

torney’s fees. 42 U.S.C. $$2000e-16(d), 2000e-5(g) (Supp. I I 1972);

42 U.S.C. $2000e-5(k) (1970); 5 C.F.B. $713.271(b) (1974).

6a

On July 23, 1973, defendants moved to dismiss the com

plaint on the ground that the court lacked subject matter

jurisdiction since Brown had not filed his complaint within

30 days as required by Section 717(c) of the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Act of 1972 and his action therefore was

barred by sovereign immunity.

On September 18, 1973, Brown moved for leave to file

an amended complaint. The proposed amended complaint

sought to add the CSC and Selbmann, the complaints exam

iner, as defendants, the original complaint having stated

that the CSC had been joined as a party defendant although

it was not actually named. The amended complaint also

alleged as additional bases of jurisdiction 28 U.S.C. §1343

(4) (1970) and the Tucker Act, 28 U.S.C. §1346(a) and (b)

(1970), and added an allegation that more than $10,000 was

in controversy.5 6

In a memorandum opinion filed September 27,1973, Judge

MacMahon held that Brown’s action was barred by sover

eign immunity and that the district court therefore lacked

subject matter jurisdiction. The judge also denied the

motion for leave to amend on the ground that the original

complaint had been dismissed and the proposed amended

complaint did not change the situation.

The essential questions thus presented are whether Sec

tion 717(c) of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972 is to be applied retroactively to claims arising before

but pending administratively at the time of its enactment;

if so, whether that Act pre-empts any other avenue of

judicial review; and whether in any event appellant has

failed to exhaust administrative remedies.

5 Although the original complaint had alleged jurisdiction under 28

U.S.C. §1331 (1970), no jurisdictional amount was alleged.

II. L e g is l a t iv e H is t o r y a n d S t a t u t o r y P r o v is io n s

We believe that a key to the resolution of these questions

may be found in the legislative history and the statutory

provisions that emerged.

Title YII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbids em

ployment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex

or national origin. 42 U.S.C. §§2000e-2 to -3 (1970), as

amended (Supp. II 1972). As originally enacted in 1964,

however, it did not apply to federal employees. 42 U.S.C.

§2000e(b) (1970). Executive Orders6 and agency regula

tions covered their complaints of employment discrimina

tion.7 In general, the agency itself conducted an investiga

tion and hearing on such complaints. Although the hear

ing examiner might come from an outside agency, espe

cially the CSC, the head of the employee’s agency made

the final agency determination. Appeal lay only to the

Board of Appeals and Review of the CSC.8

No private right of action was provided for federal em

ployees by Title YII until 1972 when Congress amended

the Equal Employment Opportunity Act by adding Sec

tion 717(c). The legislative history of this section gen

erally evinces a concern that job discrimination had not

been eliminated in the federal government. It indicates the

dissatisfaction of federal employees with the complaint

procedures available. The committee reports show that

Congress was not persuaded by testimony of agency offi

cials that legislation was not needed because a private right

6 See Exec. Order No. 11478, as amended, Exec. Order 11590, 3 C.F.R.

207 (1974), 42 U.S.C. $2000e, at 10,297 (1970); Exec. Order 11246, as

amended, Exec. Order 11375, 3 C.F.R. 169 (1974), 42 U.S.C. $2000e' at

10,294-97 (1970).

7 See 5 C.F.R. Pt. 713 (1971).

8 Id .; S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 14 (1971), reprinted in

Legislative History of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act o f 1972,

at 410, 423 (1972) (hereinafter cited as Legislative History).

8a

of action already existed. They note that, even if such right

was available, the federal employee faced defenses of sov

ereign immunity and failure to exhaust administrative rem

edies ; and, even if such defenses were overcome, the relief

available, such as back pay or immediate advancement,

was in doubt.9

It was against this backdrop that Congress in 1972 pro

vided a private right of action for federal employees who

were not satisfied with the agency or CSC decisions. Under

Section 717(c), an aggrieved employee may commence an

action in a federal district court within 30 days after a

final order by his agency on a complaint of discrimination

based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin, or

within 30 days after a final order of the CSC on an appeal

from such an agency decision, or after the elapse of 180

days from the filing of the initial complaint with the agency

or of the appeal with the CSC if no decision has been ren

dered. No appeal need be taken to the CSC. The employee

may go directly to court after the agency decision. 42

U.S.C. §2000e-16(c) (Supp. II 1972), note 1 supra.

III. R e t r o a c t iv it y

Brown’s administrative complaint was filed with the GSA

in 1971. It was under agency consideration at the time of

the enactment of Section 717(c) on March 24, 1972. The

question of retroactivity thus presented is whether the sec

tion should be applied to claims of discrimination which

arose before its effective date but were awaiting final ad

ministrative decision at that time.10 Retroactivity in this

9 H. R. Rep. No. 92-238, 923 Cong., 1st Sess. 23-26 (1971), in Legis

lative History 61, 82-86; S. Rep. No. 92-415, 923 Cong., 1st Sess. 14-17

(1971), in Legislative History 410, 421-26.

10 Cf. Petterway v. Veterans Administration Hospital, 495 F.23 223

(5 Cir. 1974) (Section 717(c) hel3 not applicable to pre-Act claim o f

fe3eral employment 3iserimination because complaint was no longer

9a

context refers only to the claim; the district court com

plaint in the instant action was filed on May 7, 1973— well

after the date of enactment.

All parties to this appeal have sidestepped the retro

activity issue.- Appellees deal with the issue briefly in a

footnote by stating that they assume retroactive operation

in their arguments here although they have argued other

wise elsewhere. Appellant argues that the section is not

applicable to the instant action precisely because he did

not file his complaint within the required 30 days and that

other statutes provide a jurisdictional basis for his action.

The issue of retroactive application of this statute has

resulted in a conflict between the circuits. The District

of Columbia and Fourth Circuits have held that Section

717(c) applies retroactively to claims pending at the time

of its enactment. Womack v. Lynn,------ F .2 d -------- (D.C.

Cir. 1974) (No. 72-1827, filed October 1, 1974); Roger v.

Ball, 497 F.2d 702 (4 Cir. 1974). The Sixth Circuit has

held that it does not. Place v. Weinberger, 497 F.2d 412

(6 Cir. 1974). The district courts have gone both ways.

Compare, e.g., Ficklin v. Sabatini, 378 F.Supp. 19 (E.D.

Pa. 1974) (retroactive); Henderson v. Defense Contract

Administration Services, 370 F.Supp. 180 (S.D.N.Y. 1973)

(retroactive); Walker v. Kleindienst, 357 F.Supp. 749

(D.D.C. 1973) (retroactive) with Moseley v. United States,

No. 72-380-S (S.D. Cal., filed January 23, 1973) (non

retroactive) ; Hill-Vincent v. Richardson, 359 F.Supp. 308

(N.D. 111. 1973) (non-retroactive).

The conflict as to retroactivity has turned on whether

Section 717(c) is to be viewed as providing a new substan

tive right for federal employees or whether it merely

provides a new remedy for enforcing an existing right.

pending in agency at time of enactment and because complaint was

filed beyond 30 day period).

10a

The pre-1972 right of a federal employee not to be dis

criminated against is said to be found in Congressional en

actments, 5 U.S.C. §7151 (1970), and Executive Orders.

Exec. Orders 11246, 11478, note 6 supra. Courts which

have adopted the view that Section 717 (c) provides a new

remedy for enforcing an existing right have held the sec

tion retroactive on the grounds that it is remedial, Hender

son v. Defense Contract Administration Services, supra, or

that it is procedural. Koger v. Ball, supra.

Courts which have refused to give retroactive effect to

the statute, aside from rejecting the view that Section

717(c) merely creates a new remedy for a pre-existing

right, have held that Congress intended only certain por

tions of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act to be

retroactive for the reason that in Section 14 of the Act,

in 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5, at 1,257 (Supp. II 1972), there is a

specific provision that amendments to one section of Title

VII are to be given retroactive effect, and since there is

no reference in Section 14 to Section 717(c), the latter

should not be given retroactive effect. See, e.g., Place v.

Weinberger, supra.

This latter view strikes us as being inconsistent with the

underlying principle of Bradley v. School Board of City

of Richmond,------U .S.------- (1974), 42 U.S.L.W. 4703 (U.S.

May 15, 1974). There the Supreme Court held that a stat

ute11 authorizing a federal court to award attorney’s fees

in school desegregation cases should have been applied by

the Court of Appeals so as to result in the affirmance of the

decision of the District Court which had awarded such fees

on the basis of its general equity power, since the statute

was enacted after the District Court’s award hut before

11 Section 718 of the Emergency School Aid Act, Title V II of the

Education Amendments of 1972, 20 1J.S.C. $1617 (Supp. I l l 1973).

11a

the Court of Appeals’ decision. The rationale of the Su

preme Court’s decision was stated as follows:

“We anchor our holding in this case on the prin

ciple that a court is to apply the law in effect at the

time it renders its decision, unless doing so would re

sult in manifest injustice or there is statutory direc

tion or legislative history to the contrary.” ------U.S.

a t ------ , 42 U.S.L.W. at 4707.

We believe that this principle applies here. Neither the

statute itself nor the legislative history gives any direction

as to whether Section 717(c) should be applied to com

plaints pending within the agency at the time of its enact

ment. In light of Bradley, we cannot agree with the Sixth

Circuit’s holding in Place v. Weinberger, supra, that Con

gress by its silence as to all sections of the Act except

one intended the other sections to have prospective ap

plication only. As the Supreme Court stated in Bradley:

“ [E]ven where the intervening law does not explicitly

recite that it is to be applied to pending cases, it is

to be given recognition and effect.

Accordingly, we must reject the contention that a

change in the law is to be given effect in a pending case

only where that is the clear and stated intention of the

legislature. . . . ” ------U.S. a t------- , 42 U.S.L.W. at 4708.

While Bradley dealt with a court of appeals’ review of a

district court’s decision, we believe that the underlying

principle is applicable to a review by a district court of an

agency decision. So far as the statutory language and the

relevant legislative history are concerned, retroactive appli

cation of Section 717(c) would appear to be appropriate.

This does not end our analysis under Bradley. We must

determine whether application of a change in law to pend-

12a

ing claims “ would result in manifest injustice” . ------ U.S.

a t ------ , 42 U.S.L.W. at 4707. In each of the cases where

Section 717(c) has been applied retroactively, it was done

to aid a plaintiff in the prosecution of his complaint. See,

e.g., Roger v. Ball, supra. In view of the policy of the

federal government against discrimination in federal em

ployment and its encouragement of efforts to eliminate

such discrimination in the private and state and local gov

ernment sectors, such retroactive application of the statute

appears sound. I f Section 717(c) is held applicable here,

however, Brown’s claim must fall since he admittedly has

failed to comply with its 30 day filing requirement.

We hold that there is no “manifest injustice” in the retro

active application of the statute to Brown’s complaint.

Twice he was notified in letters from the GSA of the pro

cedure for obtaining court review of the agency decision.

Both letters gave notice of the 30 day filing requirement.

His counsel have not suggested any excuse for the delay

in filing the complaint—either in their briefs, or in oral

argument, particularly in response to a direct question by

the Court concerning such delay. Instead, his counsel argue

that the statute does not apply because Brown has not com

plied with it.12 In a sense, he is correct in that he cannot

take advantage of the statute because he has not complied

with its terms. This failure is fatal to Brown’s claim, since

we hold below that Congress intended Section 717(c) to

be the exclusive judicial remedy for federal employee dis

crimination grievances.

IV. P k e -e m p t i o n

Appellees argue that, whatever may be the merits of the

alternative bases for jurisdiction asserted by appellant,

12 It is interesting to note that both the original complaint and the

proposed amended complaint invoked Section 717 as one basis o f

jurisdiction in the district court.

13a

they are pre-empted by Section 717(c). Neither the Act

itself nor its legislative history conclusively demonstrates

that such pre-emption was intended. Congress enacted

Section 717(c) to provide a private right of action for fed

eral employees—a right it believed to have been previously

non-existent or so difficult to enforce as to have been in

effect non-existent. The most persuasive argument in favor

of pre-emption is that the Act constitutes a waiver of sov

ereign immunity and as such must be strictly construed.

The doctrine of sovereign immunity forbids suits against

the government without its consent. Sovereign immunity

in the present context involves not only that of the United

States but also that of its officers in performing their offi

cial functions. As the Eighth Circuit succinctly put it :

“A suit against an officer of the United States is one

against the United States itself ‘ if the decree would

operate against’ the sovereign, Hawaii v. Gordon, 373

U.S. 57, 58, 83 S.Ct. 1052, 1053,10 L.Ed. 2d 191 (1963);

or if ‘the judgment sought would expend itself on the

public treasury or domain, or interfere with the public

administration’, Land v. Dollar, 330 U.S. 731, 738, 67

S.Ct. 1009, 91 L.Ed. 1209 (1947); or if the effect of

the judgment would be ‘to restrain the Government

from acting, or to compel it to act’, Larson v. Domestic

& Foreign Commerce Corp., 337 U.S. 682, 704, 69 S.Ct.

1457,1468, 93 L.Ed. 1628 (1949)___ ” Gnotta v. United

States, 415 F.2d 1271, 1277 (8 Cir. 1969) (Blackmun,

J.), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 934 (1970).

The court in Gnotta held that demands for promotion and

back pay fall within the scope of this immunity as they

necessarily involve expenditures from the Treasury and

compel the exercise of administrative discretion in an offi

cial personnel area. 415 F.2d at 1277. This is precisely

the relief demanded in the instant case.

14a

Sovereign immunity would bar prosecution of this action

absent an effective waiver. Congress can impose restric

tions on its consent to be sued, Battaglia v. United States,

303 F.2d 683, 685 (2 Cir.), cert, dismissed, 371 U.S. 907

(1962), including limitations on the time within which suit

must be commenced. United States v. One 1961 Red Chev

rolet Impala Sedan, 457 F.2d 1353, 1357 (5 Cir. 1972). The

consent Congress has given for the instant type of action

is set forth in Section 717(c). Such consent is conditioned

on compliance with the 30 day filing requirement.

Statutes waiving sovereign immunity are to be strictly

construed. But assuming, as appellant argues, that deci

sions of the Supreme Court illustrate a more liberal atti

tude with regard to waivers of sovereign immunity at least

where a federal agency is concerned, see Federal Housing

Administration v. Burr, 309 U.S. 242 (1940); Kiefer &

Kiefer v. Reconstruction Finance Corp., 306 U.S. 381

(1939), we cannot ignore the explicit condition imposed by

Congress on a suit such as the instant one. It would wholly

frustrate Congressional intent to hold that a plaintiff could

evade the 30 day filing requirement “ by the simple ex

pedient of putting a different label on [his] pleadings.”

Preiser v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 475, 489-90 (1973).

The instant complaint was filed more than a year after

passage of the 1972 Act. Brown had notice of its provi

sions. He has offered no excuse for failure to comply,

nor has he addressed the issue of retroactivity. We find

no injustice in requiring compliance with the 30 day filing

requirement. On the contrary, to permit suit without com

pliance with the conditions imposed by Section 717(c)

would effectively undermine the strong public policy that

requires strict construction of a statute which waives

sovereign immunity.18

13 In view of our holding, we find it unnecessary to consider appellant’s

claims that jurisdiction can be founded on 28 U.S.C. $1361 (1970)

15a

V. F a i l u r e t o E x h a u s t A d m in i s t r a t i v e R e m e d ie s

Finally, even if we were to hold in favor of Brown on

the issues discussed above, his claim would fall for failure

to exhaust administrative remedies under regulations in

effect prior to the 1972 Act. Although he pursued these

remedies to the extent of obtaining a final agency deci

sion, he failed to appeal to the Board of Appeals and Re

view of the CSC. See 5 C.F.R. §§713.231 to .234 (1974), 34

Fed. Reg. 5371 (1969).

Assuming without deciding that exhaustion of federal

administrative remedies may not be required in every case

of alleged discriminatory federal employment practices, cf.

McKart v. United States, 395 U.S. 185 (1969); but see Penn

v. Schlesinger, 490 F.2d 700, 707-14 (5 Cir. 1973) (dissent

ing opinion), rev’d en banc, 497 F.2d 970 (5 Cir. 1974)

(adopting panel dissent), there is nothing in the allega

tions of Brown’s complaint which justifies the “premature

interruption of the administrative process.” McKart v.

United States, supra, 395 U.S. at 193. The “notions of

judicial efficiency” stressed by the Court in McKart are

particularly applicable here:

“A complaining party may be successful in vindicating

his rights in the administrative process. I f he is re

quired to pursue his administrative remedies, the

courts may never have to intervene.” 395 U.S. at 195.

For aught that appears in the record before us, we can

not say that an appeal to the CSC might not have resulted

in granting the relief sought by Brown. Since he did

not exhaust his administrative remedies, however, we have

been presented with troublesome jurisdictional questions

(mandamus); the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. $$701-06

(1970); the Tucker Act, 28 U.S.C. $1346(a) and (b ) (1J70); and

42 U.S.C. $1981 (1970) and 28 U.S.C. $1343(4) (1970).

16a

which must be resolved before the substantive issue of

discrimination can even be considered. See Penn v.

Schlesinger, supra, 490 F.2d at 712.

Moreover, it cannot be said here that the administra

tive remedies available to Brown were inadequate or fu

tile. Cf. McKart v. United States, supra, 395 U.S. at

200; Eisen v. Eastman, 421 F.2d 560, 569 (2 Cir. 1969),

cert, denied, 400 U.S. 841 (1970). Administrative regula

tions in effect at the time Brown filed his complaint in

the district court (and which remain in effect) provided

for retroactive promotion with back pay if discrimina

tion was found. 5 C.F.R. §713.271(b) (1974), 37 Fed. Reg.

22,717 (1972). This essentially is the relief sought in

his federal court action. Nor does Brown claim that he

had no notice of the appellate relief available (he re

ceived two letters so informing him), or that his attempts

to seek administrative remedies were frustrated. See Penn

v. Schlesinger, supra, 490 F.2d at 706.

Under the circumstances of this case, we hold that Brown

inexcusably failed to exhaust available administrative rem

edies.

C o n c l u s io n -

Clearly the federal courts have jurisdiction under Sec

tion 717(c) of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972 to review claims by federal employees of dis

criminatory employment practices. Brown’s failure to com

ply with the statutory requirements with respect to ap

pealing to the Board of Appeals and Review of the CSC,

or by commencing a timely action in the district court,

has presented the threshold jurisdictional issues to which

this opinion is addressed. We hold that his failure to

commence the instant action in the district court within

30 days of the final agency decision is fatal to his com

17a

plaint since Section 717 (c) operates retroactively and pre

empts any other avenue of judicial review; and that he

has failed to exhaust available administrative remedies.

The entire process of administrative review by the CSC

and of judicial review within the 30 day period for seek

ing such review makes no sense at all if an employee may

simply ignore the statutory requirements.

Affirmed.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. «^§g» 219