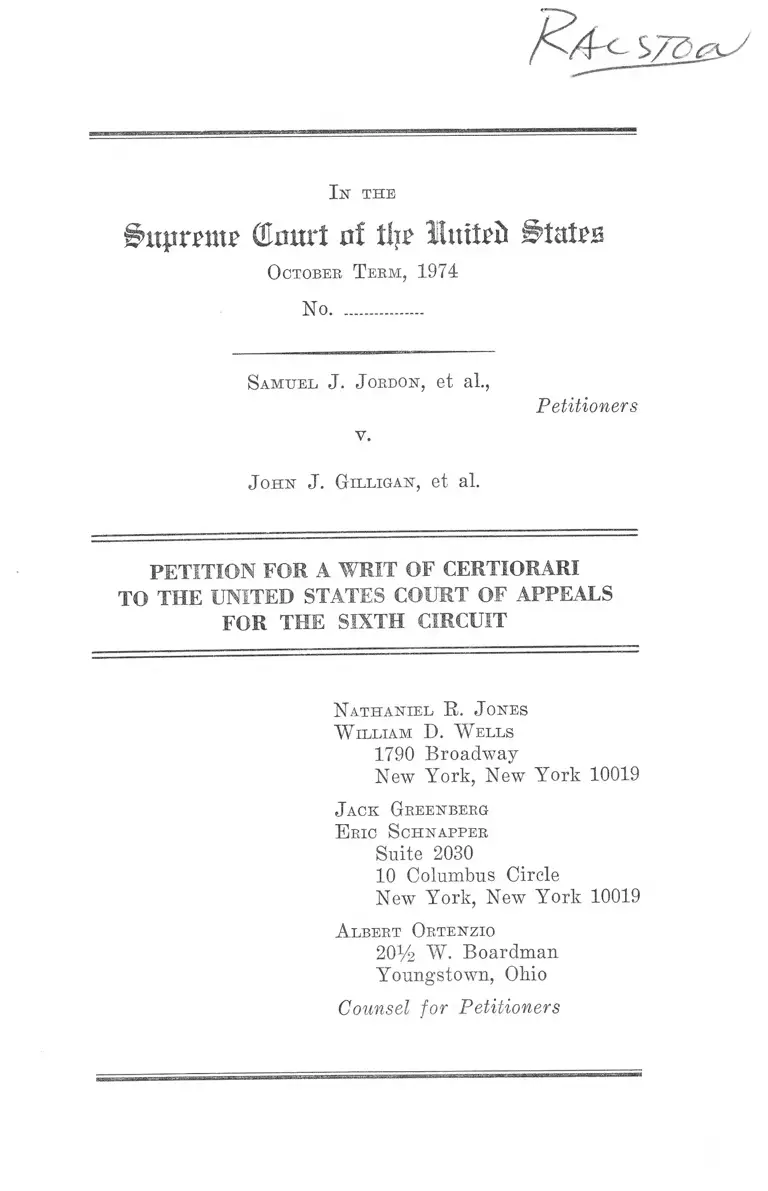

Jordon v. Gilligan Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jordon v. Gilligan Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1974. 5aedd17e-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f1b9c884-ee17-4028-94d0-4e2d0ad6e0b7/jordon-v-gilligan-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

CEnurt nf % lu tte i* States

O ctober T erm , 1974

No.................

S a m u el J . J ordon, e t al.,

Petitioners

v.

J o h n J . G illig a n , e t al.

PETITION FOE A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

N a th a n iel R . J ones

W illia m D . W ells

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

J ack Greenberg

E ric S ch n a pper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A lbert Ortenzio

20% W. Boardman

Youngstown, Ohio

Counsel for Petitioners

INDEX

Opinions Below........................................ 1

Jurisdiction ....................................... 2

Question Presented ........................................................ 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved........ 2

Statement of the Case ......................... 3

Reasons for Granting the Writ ..................................... 6

Conclusion ....... 20

A ppen d ix —

District Court Order Granting Applications for

Attorneys’ Pees and Expenses .............................. la

District Court Order Directing That Plaintiff’s

Attorneys’ Fees and Expenses Be Taxed as Costs 2a

Opinion and Order Denying Defendants’ Motion

for Stay of Execution and Vacating Attachment.... 3a

Opinion and Order Denying Defendants’ Rule

60(b) Motion .......................................................... 8a

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals April

25, 1974 ........ 10a

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals July

18, 1974 ..................................................................... 21a

PAGE

11

T able op A u th o b ities

Cases: page

Avco Corp. v. Aero Lodge, 390 U.S. 557 (1968) .......... 9

Beens v. Erdahl, (D. Minn., No. 4-71-Civ. 151) .......... 9

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 40

L. Ed. 2d 476 (1974) ................... 14

Brandenburger v. Thompson, 494 F.2d 885 (9th Cir.

1974) ............................................................................ 8,11

Clark v. Barnard, 108 U.S. 436 (1883) ................. ....... 17

Chicago, etc. R.R. Co. v. United Transportation Union,

402 U.S. 570 (1971) .................................................... 16

Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. (2 Dali.) 419 (1793) ........ 16

Class v. Norton, 376 F. Supp. 496 (D. Conn. 1974) ....... 9

Dick Press Guard Mfg. Co. v. Bowen, 229 F.193, 196

(N.D.N.Y. 1915) a fd 229 F.575 (2d Cir. 1915), cert.

denied 241 U.S. 671 (1915) ......................................... 17

Dillenberger v. Florida Probation and Parole Commis

sion, Civ. No. 73-66 (N.D. Fla.) .................................. 14

Eagle Mfg. Co. v. Miller, 41 F. 351 (S.D. Iowa 1890) .... 18

Ede’lman v. Jordan, 39 L. Ed. 2d 662 (1974) .......... 7,8,12,

13,15,19

Ex Parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908) ....6, 7, 9,10,12,15,16

Fairmont Creamery Co. v. Minnesota, 275 U.S. 70

(1927) .................................................... 6,11,12,16,18,19

First National Bank v. Dunham, 471 F.2d 712 (8th Cir.

1973) ............................................................................ 15

Gates v. Collier, 489 F.2d 298 (5th Cir. 1973) ....8, 9,11,19

General Oil v. Crain, 209 U.S. 211 (1908) ..................... 13

Graham v. Marshall, Civ. No. T-73-77 (N.D. Fla.) ........ 14

I l l

Hall v. Cole, 412 TT.S. 1 (1973) ..................................... 15

Hoitt v. Vitek, 495 F.2d 219 (1st Cir. 1974) ................ 8

Jordan v. Fusari, 496 F.2d 646 (2d Cir, 1974) ....7, 9,11,12

Jurisdictional Statement, No. 72-12, October Term, 1972 9

Kerns v. Jordon, cert. den. 42 U.S.L.W. 3468 (1974) .... 4

Kirkland v. New York State Dept, of Correctional Ser

vices, 374 F. Supp. 1361 (S.D.N.Y. 1974) ..................9,11

LaRaza Unida v. Volpe, 488 F.2d 559 (9th Cir. 1973)

8, 9,12

Liberies v. Daniel, No. 73-C-3217 (N.D. 111.) ................- 14

Manning v. Gilligan, No. 73-453, appeal dismissed 42

U.S.L.W. 3332 (1973) ................ ...... -......-............ -.... 4

Milburn v. Huecker, (6th Cir. Nos. 73-1259 and 73-1430)

(August 5, 1974) ..........................................................8,11

Mills v. Electric Auto-Life Company, 376 TJ.S. 375

PAGE

(1970) ................ .........-............................................... b

Missouri v. Fiske, 290 TJ.S. 18 (1933) ......................... 17

Mitchum v. Foster, 407 H.S. 225 (1972) ....................... 16

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ......................... 18

N.A.A.C.P. v. Allen, 340 F.Supp. 703 (M.D. Ala. 1972) 9

Named Individual Members of San Antonio Conserva

tion Society v. Texas Highway Dept., 496 F.2d 1017

(5th Cir. 1974) ................. —........-.........-.................... 8

Natural Resources Defense Council v. Environmental

Protection Administration, 484 F.2d 1331 (1st Cir.

1973) ......... ................. -........... -----........................ - 8

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ..........................................................................6,15

9

Newman v. State of Alabama, 349 F.Supp, 278 (M.D.

Ala. 1972) .....................................................................

Norris v. Jordan, No. 71-1109 and No. 71-1439, appeal

dismissed 409 U.S. 811 (1972), rehearing den. 409

U.S. 1029 ........................................... ........... ....... ...... 4

Norwood v. Harrison, No. WC 70-53-K (N.D. Miss.) .... 14

Ocean Accident & Guarantee Corp. v. Felgemaker, 143

F.2d 950 (6th Cir. 1944) ...... .................................... 17,18

Pegues v. Mississippi State Employment Services, No.

72-4-S (N.D. Miss.) .............. ..................... ................ 14

Pyramid Lake Piute Tribe v. Morton, No. 74-342 ........ 6

Scheuer v. Rhodes, 40 L.Ed. 2d 90 (1974) ................... . 7

Sims v. Amos, 340 F.Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala. 1972), aff’d

409 U.S. 942 (1972) .............................. ...........9,10,11,19

Sinrock v. Obara, 320 F.Supp. 1098 (D. Del. 1970) .....9,12

Skehan v. Board of Trustees of Bloomsburg State Col

lege, (3d Cir., No. 73-1613) (May 3, 1974) .......8, 9,11,13

Souffront v. Compagnie des Suceries, 217 U.S. 475

(1910) .......................................................................... 17

Souza v. Travisono (No. 5261, D.R.I.) ......................... . 9

Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank, 307 U.S. 161 (1939) 16

Stolberg v. Members of the Board of Trustees for

State College of Connecticut, 474 F,2d 485 (2d Cir.

1973) ............................................................................ 7, 8

Taylor v. Perini, 359 F.Supp. 1185 (N.D. Ohio 1973)

5, 9,10

Utah v. United States, 304 F.2d 23 (10th Cir. 1962)

cert, denied 371 U.S. 828 ............................................. 11

Vanguard Justice Society v. Mandel, No. 74-71-K (D.

Md.) 14

V

PAGE

Virginia Coupon Cases, 114 U.S. 269 (1885) ................ 16

Wainwright v. State of Florida Department of Trans

portation, Civ. No. 73-42 (N.D. Fla.) ............... ......... 14

Welch v. Rhodes, (S.D. Ohio, No. 69-249) vacated 492

F.2d 1244 (6th Cir. 1974) ........ .................................. 9

Wyatt v. Stickney, 344 F.Supp. 373 (M.D. Ala. 1972) .... 9

Statutes:

7 TJ.S.C. §2305 .............................. ..... ............... ........... 16

12 U.S.C. §1975 ............................................................ 16

15 U.S.C. §15 ................................................................ 16

15 U.S.C. §72 ............... 16

15 U.S.C. §78(a) ......................................... 16

15 U.S.C. §298(b) ............ 16

15 U.S.C. §1640 ......................... 16

20 U.S.C. §1617 ............................................................. 16

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ................. 2

28 U.S.C. §1920(1) ..................... 19

28 U.S.C. §1920(2) .................................. 19

28 U.S.C. §2281 ......................................................... 4

33 U.S.C. §1365 (d) .................................... 16

42 U.S.C. §1983 ............................................................. 2

42 U.S.C. §2000a-3(a) .................................................. 16

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g) .................................................... 16

42 U.S.C. §3612(e) ...... 16

vi

49 U.S.C. §8.................................................................... 16

49 TJ.S.C. §16(2) ........................................... 16

49 TJ.S.C. §908(e) ......................................................... 16

86 Stat. 103 ............................................................... 13

Other Authorities:

6 Moore’s Federal Practice j[54.77[2] .........................15,16

ten Broek, Equal Under Law (1965) ............................ 17

PAGE

Graham, “The Early Anti-Slavery Backgrounds of the

Fourteenth Amendment”, 1950 Wis. L. Rev. 479 17

Graham, “the ‘Conspiracy Theory’ of the Fourteenth

Amendment,” 47 Yale L.J. 371 (1938) ..................... 17

Brief Amicus Curiae of the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc., in Edelman v. Jordan

No. 72-410 ................................................................... 17

In the

imitmiu' ( ta r t of % lnitr& ^tatrs

O ctober T erm , 1974

No.................

S a m u el J . J ordon, e t al.,

v.

Petitioners

J o h n J. G illig an , e t al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

The petitioners, Samuel Jordon et al., respectfully pray

that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review the judgment and

opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit entered in this proceeding on July 18, 1974.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals of July 18, 1974,

is not yet reported, and is set out in the Appendix hereto,

pp. 21a-35a. The opinion of the Court of Appeals of

April 25, 1974, is not yet reported, and is set out in the

Appendix hereto, pp. 10a-20a. The opinion of the Dis

trict Court of June 12, 1973 is not reported, and is set

out in the Appendix hereto, pp. 8a-9a. The opinion

of the District Court of March 9, 1973, is not reported,

and is set out in the Appendix hereto, pp. 3a-7a.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

July 18, 1974. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

Does the Eleventh Amendment prohibit the award of

costs, including attorneys’ fees, against a state or its em

ployees in their official capacities, in litigation to enforce

the Fourteenth Amendment?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

The Eleventh Amendment to the United States Consti

tution provides:

The judicial power of the United States shall not be

construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, com

menced or prosecuted against one of the United States

by citizens of another State, or by citizens or subjects

of any foreign state.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution provides in pertinent p a rt:

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the

United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,

are citizens of the United States and of the State

wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce

any law which shall abridge the privilege or immun

ities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any

State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property,

3

Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce,

by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this ar

ticle.

Section 1983, 42 U.S.C., provides:

Every person who, under color of any statute, or

dinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or

Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any

citizen of the United States or other person within

the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Con

stitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured

in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper

proceeding for redress.

Statement o f the Case

Petitioner Samuel Jordon commenced this class action

in November, 1971, to challenge the constitutionality of

a plan reapportioning the Ohio legislature. The complaint

named as defendants several state officials in their official

capacities, including the Governor and the members of

the Ohio Apportionment Board, a state body which had

drawn the new district lines. Petitioner claimed that the

district lines in question violated the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments in that (1) there were impermis

sibly great differences in the size of the districts (2) the

voters in certain portions of the state were disenfran

chised because they were not included in any district at

all, and (3) the districts had been racially gerrymandered

to minimize the voting strength of minority voters.

without due process of law; nor deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

* # #

4

Since the action involved the constitutionality of a stat

ute of statewide application, a three judge court was duly

convened. 28 U.S.C. §2281. After a hearing on the merits

the District Court on December 3, 1971, ruled the reap

portionment plan unconstitutional because of the disparate

size of the districts and because certain areas were not

included in any House or Senate District. The District

Court was thus not required to decide whether the plan

was also invalid as an attempt to discriminate on the basis

of race. The defendants took no appeal from this decision,

and on March 13, 1972, a new redistricting plan submitted

by the defendants was approved by the District Court.

Several intervenors sought without success to overturn the

District Court’s decision on the merits. See Norris v.

Jordon, Nos. 71-1109, 71-1439, appeal dismissed 409 U.S.

811 (1972), rehearing den. 409 U.S. 1029; Manning v. Gil-

ligan, No. 73-453, appeal dismissed 42 U.S.L.W. 3332

(1973) ; Kerns v. Jordon, cert. den. 42 U.S.L.W. 3468

(1974) .

On April 19, 1972, petitioner moved for an award of

counsel fees and expenses. The defendants did not oppose

the request, and the matter was referred to the original

District Court judge, a decision by the full panel not being

required on such a question. On May 19, 1972, Chief Judge

Battisti approved the request and ordered that counsel

fees and expenses totaling $27,272.65 be paid by “the State

of Ohio, through” the named defendants “collectively, in

their official capacities, as the persons responsible for ap

portioning the State of Ohio.” P. la. No appeal was taken

from this decision.

Eight months passed and the judgment remained un

paid. On January 17, 1973, the District Court issued a

new order directing that “costs, including Plaintiff’s at

torneys’ fees and expenses as previously ordered paid in

5

the amount of $27,272.65, shall be taxed as costs against

the State of Ohio” P. 2a. No appeal was taken from this

decision. Thereafter plaintiff filed a praecipes for a writ

of fieri facias against a bank account maintained by the

State of Ohio, and the District Court directed the bank

to pay the contested monies to the clerk of the court.

On February 22, 1973, nine months after the original

award of counsel fees and 36 days after the January 17,

1973, order, the defendants and the State of Ohio moved

under Rule 60, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, to vacate

the admittedly final orders of May 19, 1972, and January

17, 1973, on the ground that those orders were in excess

of the District Court’s jurisdiction.1 Shortly thereafter,

but before the writ was enforced, the State paid the

$27,272.65 and the District Court vacated the attachment

of the State’s bank account. On June 12, 1973, the Dis

trict Court denied defendants’ motion and reaffirmed its

decisions of May, 1972 and January, 1973. Pp. 8a-9a.

On appeal the Sixth Circuit reversed. Pp. 10a-35a.

The Court of Appeals held that the Eleventh Amendment

precludes an award of counsel fees or expenses against a

state or against state officials acting in their official ca

pacities. Pp. 26a-33a. The Sixth Circuit also concluded

1 A similar pattern occurred in two other federal cases in Ohio.

In Taylor v. Perini, 359 F. Supp. 1185 (N.D. Ohio 1973), counsel

fees were ordered, apparently without opposition, on September

12, 1972. On February 26, 1973, shortly after the Rule 60 motion

in this case, the Attorney General’s office advised the District

Court the state would not pay any fees, and shortly thereafter

moved to set aside the award of fees under Rule 60. In Welch v.

Rhodes (No. 69-249, S.D. Ohio), the District Court awarded coun

sel fees against the state, Ohio having contested the amount of the

fee but not liability. On February 22, 1973 Ohio unsuccessfully

moved to set aside the award under Rule 60. Taylor is now pend

ing on appeal in the Sixth Circuit; Welch was vacated and re

manded for clarification of the district court’s order. 494 F.2d

1244 (6th Cir. 1974).

6

that the two final orders of the District Court were not res

judicata, and could be collaterally attacked by a Rule 60(b)

motion. The Court of Appeals issued its initial opinion on

April 25, 1974. Pp. 10a-20a. Petitioner sought rehearing

en banc. On July 18, 1974 the original panel issued a new

opinion, pp. 21a-35a, and the petition for rehearing en

banc was denied.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The Eleventh Amendment became effective on January

8, 1798. Since February Term, 1810, the rules of this Court

have provided that costs shall be taxed against the losing

party in every cause. For at least a century the uniform

practice of this Court has been to tax such costs even

where the losing party is a State. Fairmont Creamery Co.

v. Minnesota, 275 U.S. 70, 77 (1927). Within the last de

cade the decisions of this Court, and a variety of new

federal statutes, have increased the number of cases in

which attorneys’ fees may be assessed as part of costs.

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400

(1968); Mills v. Electric Auto-Life Company, 376 U.S. 375

(1970). Within the last two years a score of decisions in

the district courts and courts of appeals have considered

whether, in litigation against state officials under Ex parte

Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908), the federal courts have the

power to award costs, including counsel fees, to a success

ful plaintiff.2 That question was raised by this Court at oral

argument, but not decided, in Edelman v. Jordan, No.

72-1410, Transcript, p. 8.

In the instant case the District Court concluded it had

such power. In attempting to enforce its award of costs,

2 A similar question regarding whether attorneys’ fees can be

awarded against the federal government is raised by the Petition

for Certiorari in Pyramid Lake Piute Tribe v. Morton, No. 74-342.

7

including counsel fees, the District Court entered two

orders directing payment—one against the defendant state

officials “in their official capacities,” p. la, and one against

the State of Ohio. P. 2a. Both orders contemplated pay

ment out of state funds.8 The Court of Appeals reversed,

apparently reasoning, in the light of this Court’s decision

in Edelman v. Jordan, 39 L.Ed. 2d 662 (1974), that any

monetary award to be paid out of the state treasury was

precluded by the Eleventh Amendment. The opinion of

the Sixth Circuit precludes such awards for either attor

neys’ fees or ordinarily taxable expenses of the litigation,

regardless of whether the award is nominally against offi

cials in their official capacities or against the state as such.* 4

Within the last year decisions in several other circuits

have upheld awards of attorneys’ fees against state agencies

or state officers in their official capacities. In Jordan v.

Fusari, 496 F. 2d 646, 651 (2d Cir. 1974), the Second Cir

cuit held that an award of counsel fees “as part of an order

granting injunctive relief, has at most the ‘ancillary effect

on the state treasury,’ which Edelman v. Jordan, supra,

42 U.S.L.W. at 4424, characterizes as ‘a permissible and

often inevitable consequence of the principle announced in

Ex parte Young,’ 209 U.S. 123 (1908).” See also Stolberg

v. Members of the Board of Trustees for State College of

8 The question of the liability of the state officials to satisfy

such awards out of their personal funds was not considered by

either the District Court or the Court of Appeals. See Scheuer

v. Rhodes, 40 L.Ed. 2d 90 (1974).

4 The sole reason given by the Court of Appeals for reversing

the award of counsel fees and expenses, and the only argument

advanced in the Sixth Circuit, by appellants, was the prohibition

of the Eleventh Amendment. Any other possible objection to that

award is precluded by the failure of the appellants to file a timely

appeal of the District Court decisions of May 19, 1972, and January

17, 1973. Only the jurisdictional objection founded on the Elev

enth Amendment, if any, can be relied upon to attack a final judg

ment under Rule 60(b), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

8

Connecticut, 474 F.2d 485, 490, n.3 (2d Cir. 1973). In Brand-

enburger v. Thompson, 494 F.2d 885, 888 (9th Cir. 1974),

the Ninth Circuit concluded that “an award of attorneys’

fees assessed against a state official acting in his or her

official capacity is not prescribed by the Eleventh Amend

ment.” See also LaRaza Unida v. Volpe, 488 F.2d 559 (9th

Cir. 1973), affirming 57 F.R.D. 94, 101-102, n.ll. In Gates

v. Collier, 489 F.2d 298 (5th Cir. 1973), rehearing en banc

granted, the Fifth Circuit reached the same conclusion.

Although the trial court had the power to assess attor

neys’ fees and expenses against the individual defen

dants found to have engaged in the unconstitutional

conduct, we think it does not vitiate the award because

the trial court prescribed that this part of the cost were

to be payable “from funds which the Mississippi Legis

lature, at its 1973 session, may appropriate for the

operation of the Mississippi State Penitentiary” . . .

489 F.2d at 302. See also Eoitt v. Vitek, 495 F.2d 219 (1st

Cir. 1974); Natural Resources Defense Council v. En

vironmental Protection Administration, 484 F.2d 1331,

1333 (1st Cir. 1973) Milburn v. Huecker, (6th Cir., Nos.

73-1259 and 73-1430) (August 5, 1974, slip opinion, pp.

4-6). Jordan, Eoitt and Milburn were decided after Edel-

man. On the other hand the Third Circuit has concluded

that the Eleventh Amendment does preclude any award

of counsel fees, Skehan v. Board of Trustees of Blooms-

burg State College, (3d Cir., No. 73-1613) (May 3, 1974

slip opinion, pp. 20-22), and a panel of the Fifth Circuit

has recently declined to follow Gates. Named Individual

Members of San Antonio Conservation Society v. Texas

Eiglnvay Dept., 496 F.2d 1017, 1025 (5th Cir. 1974), rehear

ing en banc granted. In the instant case the Sixth Circuit

noted that “lower court decisions have not been unan

imous,” p. 30a, and stated “we respectfully decline to adopt

9

the position taken by the Fifth Circuit” in Cates. P. 30a.6

Such a conflict among the circuits requires a grant of

certiorari by this Court to establish a uniform rule. Avco

Corp. v. Aero Lodge, 390 U.S. 557, 559 (1968).

The decision of the Sixth Circuit in this case is in square

conflict with the decisions of at least 8 District Courts. In

Sims y. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691, 694 (M.D. Ala. 1972) (state

reapportionment), aff’d 409 U.S. 942 (1972), the District

Court, relying on Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908),

awarded costs, including attorneys’ fees, against “the Ala

bama State Legislature, the Governor, the Attorney Gen

eral, and the Secretary of State.” See also Newman v. State

of Alabama, 349 F. Supp. 278 (M.D. Ala. 1972), N.A.A.C.P.

v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703, 710 (M.D. Ala. 1972) (employ

ment discrimination); Taylor v. Perini, 359 F. Supp. 1185,

1186-87 (N.D. Ohio 1973) (award against state correction

officials to be paid by state); LaRasa Unida v. Volpe, 57

F.R.D. 94,102 (N.D. Cal. 1972) (environmental protection).

Kirkland v. New York State Dept, of Correctional Services,

374 F. Supp. 1361, 1381-82 (S.D. N.Y. 1974) (employment

discrimination). Wyatt v. Stickney, 344 F. Supp. 387 (M.D.

Ala. 1972) (conditions in mental hospitals); Beens v.

Erdahl, (D. Minn., No. 4-71-Civ 151) (order dated Decem

ber 14, 1972) (state reapportionment); Class v. Norton,

376 F. Supp. 496, 376 F. Supp. 503 (D. Conn. 1974);

Sousa v. Travisono, (D.R. J., No. 5261) (opinion dated

July 8, 1974). Welch v. Rhodes, (S.D. Ohio, No. 69-249)

(orders dated May 8, 1972 and May 23, 1973) vacated 492

F.2d 1244 (6th Cir. 1974). But see Sincock v. Ohara, 320

F. Supp. 1098 (D. Del. 1970). Kirkland, Class and Sousa

were decided after Edelman. 5

5 Similarly the Third Circuit in SJcehan expressly declined to

follow Gates, slip opinion, p. 18, n. 7, or Jordan v. Fusari, Order

of June 11, 1974, amending opinion of May 3, 1974.

10

Tlie conflict among the lower courts exists largely because

of uncertainty as to the significance of this Court’s decision

of October 24, 1972, affirming Sims v. Amos, supra. Sims

had directed that an award of counsel fees be paid by the

Governor and Legislature of the State of Alabama. In its

Jurisdictional Statement, Alabama objected

The award to the plaintiffs of their attorneys’ fees and

expenses incurred and . . . the taxing of these items as

costs against the defendants who are elected state of

ficials erred in their official capacity . . . was tanta

mount to the award of money judgment against the

State of Alabama in direct violation of the doctrine

of sovereign immunity.

Jurisdictional Statement, No. 72-12, October Term, 1972,

p. 17. Appellees contended that Ex parte Young 209 U.S.

123 (1908), permitted an award of costs, including counsel

fees, against a state or its employees in their official capaci

ties, and that the Eleventh Amendment did not apply to any

award of costs even including counsel fees. Motion to

Dismiss or Affirm, No. 72-12, October Term, 1972, pp. 9-12.

This Court affirmed the award of counsel fees without opin

ion. 409 U.S. 942.

The lower courts awarding counsel fees against states

since Sims have consistently relied on this Court’s affirm

ance in that case. In Taylor v. Perini, 359 F. Supp. 1185,

1186, (N.D. Ohio 1973), the court explained regarding

Sims:

Counsel for the plaintiffs has also supplied this Court

with the Jurisdictional Statement of the case which was

filed in the United States Supreme Court by the Attor

ney General of Alabama. On page seventeen of this

statement, the question of Alabama’s sovereign im

munity is clearly set forth. Although the Supreme

Court affirmed the district court decision without

11

opinion, it can logically be assumed that, in light of

these two clear references to the Eleventh Amendment

problem, the Supreme Court considered it in making its

determination. This Court concludes, therefore, that

the Sims case is controlling on this issue. . . .

See also Gates v. Collier, 489 F.2d 298, 302 (5th Cir. 1973)

(quoting the Jurisdictional Statement); Jordan v. Fusari,

496 F.2d 646, 651 n .ll (2d Cir. 1974); Milburn v. Huecher

(6th Cir., nos. 73-1259 and 73-1430) (August 5, 1974, slip

opinion, p. 8); Brandenburger v. Thompson, 494 F.2d 885,

888 (9th Cir. 1974); Kirkland v. New York State Dept of

Correctional Services, 374 F.Supp. 1361, 1382 (S.D. N.Y.

1974). In the instant case the Sixth Circuit noted that

Sims had been relied on by 5 other courts, but declined to

follow it on the ground that summary affirmances were not

“of the same precedential value” as a written opinion from

this Court. Pp. 27a-29a. In Skehan v. Board of Trustees

of Bloomsburg State College (3d Cir., No. 73-1613), the

Third Circuit concluded that Edelman v. Jordan was in

tended to overrule the affirmance in Sims, and that this

Court’s failure to expressly overrule Sims was mere “in

advertence.” (May 3, 1974, slip opinion p. 18, n. 7). Such

uncertainty as to the significance and vitality of Sims can

only be resolved by this Court.

A similar conflict exists as to the significance of this

Court’s decision in Fairmont Creamery v. Minnesota, 275

U.S. 70 (1927). Fairmont Creamery expressly held that a

state’s sovereign immunity did not protect it from an

award of costs in federal court. See also Utah v. United

States, 304 F.2d 2d (10th Cir. 1962) cert, denied 371 U.S.

828. In Sims v. Amos the appellee contended that the rule

in Fairmont Creamery covered an award of counsel fees

as part of costs. Motion to Dismiss or Affirm, No. 72-12,

October Term, 1972, pp. 10-11. Fairmont Creamery was

expressly relied upon by the Second Circuit in Jordan v.

Fusari and the District Court in LaRaza Unida v. Volpe.

See No. 73-2364, 2d Cir., April 29,1974, slip opinion, p. 3068

n. 11, 57 F.R.D. 94, 101-102, n. 11 (N.D. Cal. 1972). The

Sixth Circuit, however, declined to follow Fairmont Cream

ery in this case on the ground that counsel fees are not

“analogous” to costs, p. 33a. and the district court in Sm

ooch v. Ohara, dismissed the “provocative language in the

opinion” on the incorrect assumption that the award of

costs in Fairmont Creamery had been against the United

States. 320 F. Supp. 1098, 1104, n. 12.

The Court of Appeals also concluded that Eleventh

Amendment restricts the power of the federal courts to en

force the Fourteenth Amendment, pp. 31a-33a. In Ex parte

Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908), this Court expressly left open

the question of whether the Eleventh Amendment had been

limited by the later enactment of the Fourteenth.6 In Edel-

man v. Jordan, 39 L.Ed. 2d 662 (1974), two members of this

Court concluded that question was still unresolved.7 The

Sixth Circuit, however, concluded that this Court in Edel-

man had decided, sub silentio, that the Eleventh Amend

ment limited the power of the federal courts to provide

remedies for violations of the Fourteenth.

6 “We think that, whatever the rights of complainants may be,

they are largely founded upon that [Fourteenth] Amendment,

but a decision in this case does not require an examination or

decision of the question whether its adoption in any way altered

or limited the effect of the earlier [Eleventh] Amendment”. 209

U.S. at 150.

7 “It should be noted that there has been no determination in

this case that state action is unconstitutional under the Fourteenth

Amendment. Thus, the Court necessarily does not decide whether

the States’ Eleventh Amendment sovereign immunity may have

been limited by the later enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the extent that such a limitation is neeessary to effectuate the

purposes of that Amendment, an argument advanced by an amicus

in this case.” 39 L.Ed. 2d at 690, n.2; c.f. Curtis v. Loether, 415

U.S. 189, 198, n.15 (1974).

13

Claims for money against a state can arise in three

separate legal frameworks. . . . Third, it may be based

on the Fourteenth amendment, which binds the states

directly and under §5 of which Congress has the power

to create remedies. . . . Justice Marshall is technically

correct that Edelman does not dispose of the Third

category. But the majority opinion expressly over

rules Shapiro v. Thompson, supra; State Department

of Health and Rehabilitative Services v. Zarate, supra,

and Wyman v. Bowens, supra, all Fourteenth amend

ment cases. We think Edelman must be read as closing

the door on any money award from a state treasury

in any category.

Appendix, 32a-33a. The Third Circuit has also concluded

that the Eleventh Amendment limits remedies under the

Fourteenth. Shehan v. Board of Trustees of Bioomsburg

State College (3d Cir., No. 73-1613) (May 3, 1974, slip

opinion p. 18, n.7).

In General Oil Company v. Crain, 209 U.S. 211, 226-27

(1908), this Court recognized that if the Eleventh Amend

ment precluded the award of necessary and proper relief

in cases under the Fourteenth Amendment, “the 14th

Amendment, which is directed at state action, could be

nullified as to much of its operation”. The decision of the

Sixth Circuit substantially restricts the power of Congress

under section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment to redress

violations of that Amendment. In the wake of Edelman,

Shehan, and the decision in this case, states have chal

lenged the constitutionality of several important federal

laws enacted under section 5. In 1972 Congress amended

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act to create a cause of

action against states which discriminate in employment on

the basis of race. 86 Stat. 103, 42 IJ.S.C. §2000e(a). Because

14

the remedies available under Title VII include both counsel

fees and back pay, the states of Florida, Mississippi, Mary

land and Illinois have contended that Title VII is, in this

respect, unconstitutional.8 In Tennessee the Attorney Gen

eral has ruled that Title VII violates the Eleventh Amend

ment, and that an employee who was discriminated against

on the basis of race and sex could not be reimbursed for

back wages “without a specific appropriation by the legis

lature.” Expressly relying on the decision of the Sixth

Circuit in this case, the ruling concluded

Jordon v. Gilligan, . . . held the granting of attorney’s

fees against state governments to be barred by the

Eleventh Amendment. The Courts have found this

necessary to preserve the fiscal integrity of the states

. . . . The Civil Rights Act is, therefore unconstitutional

in as much as it may attempt to require the payment

of back wages by State employees and the charging of

attorney’s fees against State government.9

The constitutionality of section 718 of the Emergency

School Aid Act of 1972, which authorizes awards of counsel

fees against a State or any agency thereof in certain school

litigation, is now at issue in Norwood v. Harrison, No. WC

70-53-K (N.D. Miss.). See Bradley v. School Board of the

City of Richmond, 40 L.Ed. 2d 476 (1974). The power of

Congress and the federal courts to enforce the Fourteenth

8 Dillenberger v. Florida Probation and Parole Commission, Civ.

No. 73-66 (N.D. Fla.) ; Wainwright v. State of Florida Department

of Transportation, Civ. No. 73-42 (N.D. F la .); Graham v. Marshall,

Civ. No. T-73-77 (N.D. F la .); Vanguard Justice Society v. Mandel,

No. 74-71-K (D. Md.) ; Liberies v. Daniel, No. 73-C-3217 (N.D.

111.); Pegues v. Mississippi State Employment Services, No. 72-4-S

(N.D. Miss.).

9 Letter of Assistant Attorney General William B. Hubbard to

Mr. Randy Griggs, Director, Tennessee Office of Economic Oppor

tunity, July 18, 1974.

15

Amendment is a constitutional question of the first mag

nitude which only this Court can definitively decide, and a

prompt resolution is necessary lest uncertainty as to the

availability of a remedy delay the commencement or prose

cution of private civil litigation to enforce Title VII or

other prohibitions against state discrimination.

The decision of the Sixth Circuit clearly misconstrues this

Court’s decision in Edelman v. Jordan, 39 L.Ed.2d 662

(1974). Edelman did not forbid the award of any relief

which had any financial impact on a state; it recognized the

propriety of relief with an “ancillary effect on the state

treasury” as “a permissible and often inevitable conse

quence of the principle announced in Ex Parte Toumg.” 39

L.Ed.2d at 675. The awards precluded by the Eleventh

Amendment are those “measured in terms of a monetary

loss resulting from a past breach of a legal duty on the part

of the defendant state officials”. 39 L.Ed.2d at 676. When

counsel fees are available in the United States it is not as

an element of damages needed to make whole the plaintiff.

See 6 Moore’s Federal Practice 1)54.77 [2]. Counsel fees,

unlike damages or retroactive welfare payments, are not

provided as compensation violation of a substantive right,

but for a variety of other reasons, such as (1) punishing a

litigant for obdurately obstinate conduct and deterring such

conduct in the future, First National Bank v. Dunham, 471

F.2d 712 (8th Cir. 1973) (2) sharing the cost of the litiga

tion among those benefiting from it, Hall v. Cole, 412 U.S. 1

(1973), and (3) encouraging the prosecution by “private

attorneys general” of litigation advancing important public

policies. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390

U.S. 400 (1968). Such an award is not analogous to the

award at law of compensatory damages, the relief which

the Eleventh Amendment was enacted to preclude, but is

an incident of the inherent power of equity to render com

16

plete justice in a case. Compare Sprague v. Ticonic Na

tional Bank, 307 U.S. 161 (1939). The Amendment does not

preclude an award of costs against a state, Fairmont

Creamery v. Minnesota, 275 U.S. 70 (1927), and when at

torneys fees are available it is as an element of costs. Mills

v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375, 391 (1970); 6 Moore,

Federal Practice If 54.77.10 An award of counsel fees, as any

other award of costs, does not fall within the proscription of

the Eleventh Amendment.

The Sixth Circuit was also in error in concluding that the

Eleventh Amendment limited the remedies available to

enforce the Fourteenth Amendment. Although those pro

visions can often be reconciled through the legal fiction of

Ex parte Young 209 TJ.S. 123 (1908), when the two amend

ments are in conflict the more specific and recent provisions

of the Fourteenth must prevail. See The Virginia Coupon

Gases, 114 U.S. 269, 331 (1885); Chicago, etc. R.R. Co. v.

United Transportation Union, 402 TJ.S. 570, 582 (1971).

Sovereign immunity is merely a procedural protection for

the sovereign powers of the states, Chisholm v. Georgia, 2

TJ.S. (2 Dali.) 419, 429 (1793) (Iredell, J., dissenting), and

that immunity has no application in areas where the Four

teenth Amendment has stripped the states of their sover

eign power. See Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U.S. 225, 242

(1972). That the Eleventh Amendment should be con

strued to limit remedies under the Fourteenth would he

particularly inappropriate in view of the fact that the

framers of the Fourteenth believed the rights described

therein already existed by virtue of the privileges and im-

10 Federal statutes expressly authorizing an award of counsel

fees invariably do so by making them one of the recoverable costs.

See e.g. 7 U.S.C. §2305; 12 U.S.C. §1975; 15 U.S.C. §§15, 72,

78(a), 298(b), 1640; 20 U.S.C. §1617; 33 U.S.C. §1365(d);

42 U.S.C. §§2000a-3(a), 2000e-5(g), 3612(c) ; 49 U.S.C. §§8, 16(2),

908(e).

17

inanities clause and the Bill of Eights, and proposed the

Amendment to assure that there would be a remedy to re

dress violations of those rights. See generally ten Broek,

Equal Under Law (1965); Graham, “The Early Anti-

Slavery Backgrounds of the Fourteenth Amendment”, 1950

Wis.L.Bev. 479; Graham, “the ‘Conspiracy Theory’ of the

Fourteenth Amendment,” 47 Yale L.J. 371 (1938); Brief

Amicus Curiae of the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Edu

cational Fund, Inc., in Edelman v. Jordan, No. 72-410.

Under the circumstances of this case Ohio clearly waived

any immunity from liability for costs and attorneys’ fees.

In an action such as this a state doubtless has a right to

intervene in the litigation, participate in its conduct, and

submit its legal claims to judicial determination. Had Ohio

formally become a party, it would have waived its immunity

under the Eleventh Amendment and become liable to judg

ment like any other litigant. Clark v. Barnard, 108 U.S.

436, 447-48 (1883); Missouri v. Fishe, 290 U.S. 18, 24 (1933).

In the instant case Ohio, without formally becoming a

party, sought and obtained all the benefits of that status

in the District Court; it appeared through the state Attor

ney General, it assumed control of the defense, and it suc

cessfully opposed efforts by the nominal defendants to con

trol that defense. A non-party who with such an interest

in the outcome of litigation, even if the non-party would

otherwise have been outside the jurisdiction of the district

court, is bound by the outcome of the litigation, Sou fron t

v. Compagnie des Suceries, 217 U.S. 475, 486-87 (1910);

Dick Press Guard Mfg. Co. v. Bowen, 229 F.193, 196 (N.D.

N.Y. 1915), aff’d 229 F.575 (2d Cir. 1915), cert, denied 241

U.S. 671 (1915). Such a nominal non-party is no stranger

to the litigation, and judgment on the merits may be entered

directly against him as well as against the formal parties.

Ocean Accident & Guarantee Corp. v. Felgemaker, 143 F.2d

18

950, 952 (6th Cir. 1944); Eagle Mfg. Co. v. Miller, 41 F.351,

357 (S.D. Iowa 1890).

Neither the Eleventh Amendment nor Monroe v. Pape,

365 U.S. 167 (1961), give a state an absolute immunity

from liability; they assure such immunity only so long as a

state does not seek the benefits that would be its as a party.

When a state official is sued for an alleged violation of

federal law, the state may choose to remain at arms length

from the litigation, leaving the official to prove his innocence

of the charges. In such a case the state’s immunity remains

intact. But if the state elects to participate fully in the

litigation, assuming the same control .of the litigation it

would have had as a named defendant, it must accept the

ordinary consequences of such participation. In cases such

as this for injunctive relief the named officials, if left to

their own resources, would have little interest in the out

come of the litigation; it is only because of the participa

tion of the state that substantial efforts by plaintiffs counsel

are required. A state cannot, by such participation in civil

rights litigation, precipitate extended litigation and require

the expenditure of substantial time, effort and monies by

plaintiffs and their counsel without becoming liable for the

costs, including counsel fees, of such action if the defense

is unsuccessful.

The Court of Appeals also overturned that portion of

the District Court’s opinion awarding costs for items other

than counsel fees. The District Court order of May 19,

1972, granted as part of costs $1262.65 for various expenses

of the litigation. Although the Sixth Circuit opinion deals

primarily with the question of counsel fees, it reverses the

award of these expenses as well as “void for lack of juris

diction.” pp. 23a, 35a, This Court, however, has of course

held that a state’s immunity does not protect it from an

award of costs. Fairmont Creamery Co. v. Minnesota, 275

19

U.S. 70 (1927). Among the items awarded as expenses by

the District Court were expenditures traditionally awarded

as costs, including marshall fees, 28 U.S.C. § 1920(1) and

stenographic charges, 28 U.S.C. §1920(2). Insofar as the

Sixth Circuit held that Ohio could not be required to pay

these costs, its decision was clearly erroneous.

The substantiality of the question presented by this Peti

tion is attested to by the position taken by the United States

in an amicus brief in Gates v. Collier (5th Cir. No. 73-1790).

The Department of Justice there urged at length that the

Eleventh Amendment does not prohibit the award of coun

sel fees against a state in a case such as this. The Govern

ment contended that the states waive any immunity from

such an award by participation in the litigation. “In choos

ing to defend an action properly brought in a federal forum,

defendants must assume responsibility for the normal inci

dents of such a suit, including costs, witness fees, and at

torneys’ fees.” Brief for the United States, pp. 16-17. Ex

pressly referring to Mr. Justice Marshall’s dissent in Edel-

man v. Jordan, supra, p. 32, the United States asserted

“There are considerations which suggest that the Eleventh

Amendment is limited in part by the Fourteenth and that

issue must eventually be decided (perhaps in a case seeking

‘damages’ for Fourteenth Amendment violations).” Brief

for United States, p. 15, n,8. The Government expressly

relied on Fairmont Creamery Co. v. Minnesota, 275 U.S. 70

(1927), on this Court’s affirmance of Sims v. Amos, 409

U.S. 942 (1972), and contended that counsel fees were with

in the “ancillary effect on the state treasury” permitted by

Edelman. Brief for the United States, pp. 7, 18-20.

20

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, a Writ of Certiorari should issue

to review the judgment and opinion of the Sixth Circuit.

N a t h a n ie l R . J o nes

W il l ia m D . W ells

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

J ack G reen berg

E r ic S c h n a p p e r

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A lb er t O rten zio

201/2 W. Boardman

Youngstown, Ohio

Counsel for Petitioners

APPENDIX

la

District Court Order Granting Applications for

Attorneys Fees and Expenses

[Entered: May 19, 1972]

[C a ptio n ]

Battisti, C .J.:

Counsel for plaintiffs have made application for the

allowance of attorney’s fees and expenses to date. There

is no opposition to the amounts requested and they seem

reasonable on their face.

Therefore, the State of Ohio, through John J. Gilligan,

Governor; Joseph T. Ferguson, State Auditor; Ted W.

Brown, Secretary of State; Anthony 0. Calabrese, Sr.,

State Senator; and Robert A. Manning, State Represen

tative, collectively, in their official capacities, and as the

persons responsible for apportioning the State of Ohio,

are ordered and directed to pay attorney’s fees to Na

thaniel R. Jones in the sum of $15,580.00 and expenses

in the sum of $799.64 and are ordered and directed to pay

attorney’s fees to Albert J. Ortenzio in the sum of $10,430.00

and expenses in the sum of $463.01.

Frank J. Battisti

Chief Judge

2a

District Court Order Directing That Plaintiff’s

Attorney’s Fees and Expenses Be Taxed as Costs

[Filed: January 17, 1973]

By previous order entered by this Court the State of

Ohio was ordered to pay Plaintiff’s attorneys’ fees in this

action. The Court now being advised that the State of

Ohio has failed and confines to refuse to comply with

said order, now directs that Plaintiff’s attorneys’ fees and

expenses be taxed as costs in this action.

Accordingly, costs, including Plaintiff’s attorneys’ fees

and expenses as previously ordered paid in the amount of

$27,272.65 shall be taxed as costs against the State of Ohio.

It is so O rdered .

[C a p t io n ]

Judge

Date: January 17, 1973

3a

Opinion and Order Denying Defendants5 Motion for

Stay of Execution and Vacating Attachment

[Filed: March 9, 1973]

[ C a p t i o n ]

B a t t is t i, C.J.:

M em o ra n d u m O p in io n and O rder

The defendant State of Ohio has moved this Court,

pursuant to Rule 62(b), Fed.R.Civ.P., for an order staying

execution of, or any proceedings to enforce, the order

awarding attorneys’ fees entered previously. This motion

has been denied.

This case has experienced a rather long tenure in this

Court, but its end is finally in sight. The Court sees no

necessity for reviewing all of the history. However, a short

precis of recent events is required. Subsequent to this

Court’s last order in March, 1972, counsel submitted a

bill for attorneys’ fees. The State of Ohio wisely decided

not to object, because the fees were justified and reason

able. The amounts charged by counsel represents the

prevailing hourly rates charged by attorneys in their re

spective areas. This Court has regularly permitted attor

neys to so recover. In fact, in two recent protracted cases

Cleveland counsel were paid the prevailing hourly rates.1

One of these cases involved the apportionment of the City

of Cleveland.

The necessity and desirability of allowing attorneys’

fees in such cases such as this was best expressed by a 1

1 See In the Matter of the Complaint of the Cambria Steamship

Company, et al., C 67-61 (U.S.D.C. N.D. Ohio, 1973); see also

Kathleen Ann Tanko v. Anthony R. Stringer, et al., C 69-113

(U.S.D.C. N.D. Ohio, 1971).

4a

tliree-jucige district court for the Middle District of Ala

bama, Northern Division. The Court there said:

“In instituting the case sub judice, plaintiffs have

served in the capacity of ‘private attorneys genera?

seeking to enforce the rights of the class they repre

sent. See generally Newman v. Piggie Park Enter

prises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968); Miller v. Amusement

Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970). If,

pursuant to this action, plaintiffs have benefited their

class and have affectuated a strong congressional

policy, they are entitled to attorneys’ fees regardless

of defendants’ good or bad faith. See Mills v. Electric

Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375 (1970). Indeed, under

such circumstances, the award loses much of its dis

cretionary character and becomes a part of the effec

tive remedy a court should fashion to encourage public-

minded suits, id., and to carry out congressional policy.

Lee v. Southern Home Sites, 444 F.2d 143 (5th Cir.

1971).

The present case clearly falls among those meant

to be encouraged under the principles articulated in

Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc. and Mills, and expanded

upon in Southern Home Sites and Bradley [v. School

Board of Richmond, 53 F.R.D. 28 (E.D.Va., 1971)].

The benefit accuring to plaintiffs’ class from the prose

cution of this suit cannot be overemphasized. No

other right is more basic to the integrity of our

democratic society than is the right plaintiffs assert

here to free and equal suffrage. In addition, con

gressional policy strongly favors the vindications of

federal rights violated under color of state law, 42

U.S.C. 1983, and, more specifically, the protection of

Opinion and Order Denying Defendants’ Motion for

Stay of Execution and Vacating Attachment

5a

the right to a nondiscriminatory franchise. See the

Voting Eights Act of 1965, 79 Stat, 437, 42 U.S.C.

1973; the Civil Rights Acts of 1964, 78 Stat. 241,

42 T7.S.C. 1971; of 1960, 74 Stat, 86, and of 1957,

71 Stat. 634; and U.S. Const., amend. XIV and SV.

It is of no consequence that the statute under which

plaintiffs filed this suit, 42 U.S.C. 1983, is silent on

the availability of attorneys’ fees. See Long v. Georgia

Kraft Co., Civil No. 71-1476, 5th Cir., Jan. 28, 1972,

and the many cases cited therein; Knight v. Auciello,

40 U.S. LAVeek 2453 (1st Cir. Jan. 17, 1972).

Despite the benefit to plaintiffs’ class, however, and

despite this suit’s effectuating the purpose of con

gressional legislation, the case sub judice is one most

private individuals would hesitate to initiate and

litigate. Circumstances described in Bradley as ren

dering school desegregation suits unattractive to pro

spective plaintiffs apply with equal force to reappor

tionment cases:

. . . No substantial damage award is ever likely,

and yet the costs of proving a case for injunctive

relief are high. To secure counsel willing to under

take the job of trial, including the substantial duty

of representing an entire class . . . necessarily means

that someone—plaintiff or lawyer—must take a great

sacrifice unless equity intervenes . . .’

Consequently, in order to attempt to eliminate these

impediments to pro bono publico litigation, such as

is here involved, and to carry out congressional policy,

an award of attorneys’ fees is essential.” Sims, et al.

v. Amos, et al., 340 F. Supp. 691, 694-695 (M.D. Ala.

1971) (Footnote eliminated).

Opinion and Order Denying Defendants’ Motion for

Stay of Execution and Vacating Attachment

6a

Some clamor lias been generated over the amount of

these fees and the necessity of the State to pay them.

This clamor is not a part of this Court’s record and is not

for our consideration. However, it should be noted that

counsel have performed a great service for all those who

vote in elections for the General Assembly of the State of

Ohio. Counsel have devoted many hours to perform a

beneficial service for this State. They deserve to be paid

for the successful efforts. Plaintiffs then attached a State

bank account. The attachment has not been consummated

for reasons unknown to this Court. Fortunately, however,

the State has come to realize its lawful debt to these men

must be paid and has now done so. Therefore, the Marshal

is hereby ordered to remove the attachment on the Union

Commerce Bank in Cleveland.

It should be noted that although the plaintiffs have been

successful in the United States Supreme Court, they are

still victimized by frivolous appeals to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, brought by a lawyer

whose ability to comprehend federal practice seems ex

tremely limited. His refusal to obey a clear injunction

caused him to be found guilty of contempt by this Court.

The appellant in that case suffered the same fate. The

Courts should not be used as a sounding board for their

political grievances. The proper remedy lies elsewhere,

that is to say, in the political process. It is entirely con

ceivable that counsel may properly seek attorneys’ fees

from the appellant for his frivolous appeals. However,

since this matter is not before the Court, no such deter

mination is made. It is clear, however, that counsel did

not comprehend the order to the Supreme Court. Man

ifestly he was not a proper party to appeal to the United

Opinion and Order Denying Defendants’ Motion for

Stay of Execution and Vacating Attachment

7a

States Supreme Court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1253. Whether

he has standing in the Court of Appeals remains to be seen.

On the other hand, counsel for the State of Ohio recog

nized that there were obvious constitutional infirmities on

the face of the first apportionment plan. A new plan was

submitted to this Court and it was defended admirably.

They recognized the service of plaintiffs’ distinguished

counsel and therefore did not oppose the fee bills. They

knew that almost all the precedent and right reason sup

ports the payment of reasonable attorneys’ fees in reap

portionment cases. They also knew that to oppose the

bills would have been a vain act and that responsible

lawyers do not so indulge themselves and their clients.

Accordingly, payment having been executed, the attach

ment made by plaintiffs on the Union Commerce Bank,

Cleveland, Ohio, is hereby vacated.

It is so Ordered .

Opinion and Order Denying Defendants’ Motion for

Stay of Execution and Vacating Attachment

[s] Frank J. Battisti

F r a n k J . B a t t ist i

Chief Judge

8a

Opinion and Order Denying Defendants’

Rule 6 0 (b ) Motion

[Filed: June 12, 1973]

Battisti, C.J.

Defendants have filed a motion under Rule 60(b) re

questing the Court to reconsider the awarding of attorney

fees in this case. They allege as a basis for this motion

that the Eleventh Amendment to the United States Con

stitution proscribes the awarding of such fees.

The facts of this case need not be discussed further at

this time. Counsel for plaintiff performed a valuable ser

vice for the people of the State of Ohio in proposing an

acceptable reapportionment plan for the State legislature.

The Court awarded reasonable fees as compensation for

these services, and counsel for the State neither objected

nor appealed when the award was made. Defendants now

claim that this award of fees should be reopened under

Rule 60(b), alleging for the first time that it is violative

of the Eleventh Amendment.

The judgment is not void and, therefore, not subject to

being reopened under Rule 60(b)(4). Even assuming,

arguendo, that the Eleventh Amendment argument were

sound, the judgment entered herein is res judicata as to

any issue which was or could have been raised in the initial

proceedings. See Chicot County Drainage District v. Bax

ter State Bank, 308 US 371 (1940). Thus, the Court need

not decide the Eleventh Amendment question at this time.

It should be noted in passing, however, that at least one

other three-judge court has awarded attorney fees in simi

lar circumstances, Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691 (N.D.

[C a pt io n ]

9a

Ala. 1972), aff’d, 409 US 942 (1972). More recently, Judge

Young considered this argument and rejected it in a de

tailed and well-reasoned opinion. Taylor v. Perini, -----

F. S upp----- (N.D. Ohio, No. C 69-275, decided May 23,

1973).

Nor is this an appropriate case to consider under Rule

60(b)(6). That rule was clearly designed to operate only

in circumstances in which a full and fair hearing was not

had in the first instance. Counsel has not attempted to

show a “reason justifying relief from the operation of the

judgment,” other than to present a defense not raised

earlier. The adoption of this position would make any

judgment subject to reopen upon discovery of additional

defenses which were available but not raised at the first

trial, and would completey destroy the concept of res

judicata as that term is generally understood. This could

not have possibly been the intention of the drafters of

Rule 60(b) (6), for sound public policy has always dictated

that there must be an end to litigation at some point. See

Baldwin v. Iowa State Traveling Men’s Assoc., 283 US 522

(1931). That point in this case should have been reached

long ago.

Defendants have shown no valid reason to justify re

opening this case. Accordingly, their motion under Rule

60(b) is denied.

I t I s S o O rdered .

Opinion and Order Denying Defendants’

Rule 60(b) Motion

[ s ] F r a n k J. R a t t ist i

Frank J. Battisti

Chief Judge

Opinion o f United States Court o f Appeals

April 25 , 1974

No. 73-1973

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Sa m u e l J. J ordon , e t a l .,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

J o h n J. G illig a n , e t a l .,

Defendants-Appellants.

A p p e a l from the

United States District

Court for the North

ern District of Ohio,

Eastern Division.

Decided and Filed April 25, 1974.

Before: P eck , M il l e r and L iv ely , Circuit Judges.

P eck , Circuit Judge. This is an appeal from an order en

tered in the district court denying appellants’ motion to va

cate a prior order of that court awarding attorneys’ fees

against the State of Ohio. The appellants’ principal assertion

is that the award was void since, under the Eleventh Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, the State was

immune from the award, and the court was without jurisdic

tion to make it.

The record establishes that in November of 1971, Samuel

Jordon filed a class action suit against the members of the

Ohio Apportionment Board, a state body responsible for the

decennial reapportionment of the Ohio legislature. Included

as defendants were state officials and members of the Ma

honing County Board of Elections in their official capacities.

The State of Ohio was not a named defendant. Plaintiff

11a

sought, on behalf of the class of all Ohio voters, a declaratory

judgment that a reapportionment plan adopted by the Board

was constitutionally infirm, and he asked that injunctions re

quiring the Board to establish a revised plan that would sat

isfy applicable requirements be issued. Plaintiff also prayed

for an award of attorneys’ fees against the defendants. Federal

jurisdiction was invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1343 for

alleged violations of' the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend

ments as implemented by 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

The Board’s original plan was declared unconstitutional by

the three-judge district court convened to hear the case under

the terms of 28 U.S.C. § 2281. The district court ordered ap

pellants to submit a new plan that would comply with state

and federal constitutional demands. A revised plan was duly

submitted to and approved bv the court in December of 1971.

After allowing appellees 60 days in which to- file objections to

the revised plan, the court entered a final order adopting

it for the decennium.

Counsel for appellees filed applications for awards of at

torneys’ fees and expenses in the combined amounts of $27,-

272.65. The district court, in the absence of any objections

to the applications from appellants, entered the following

order on May 19, 1972:

“Counsel for plaintiffs have made application for the

allowance of attorney’s fees and expenses to date. There

is no opposition to the amounts requested and they seem

reasonable on their face.

“Therefore, the State of Ohio, through John J. Gilligan,

Governor; . . . collectively, in their official capacities, and

as the persons responsible for apportioning the State of

Ohio, are ordered and directed to pay attorney’s fees

Eight months passed and the judgment remained unpaid. On

January 17, 1973, the district court ordered the award of at

torneys’ fees and expenses taxed as costs against the State of

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

April 25, 1974

12a

Ohio.1 Appellees filed a praecipes for a writ of fieri facias

against a bank account maintained by the State at a bank

in Cleveland, Ohio, and the court acted to enforce it by

ordering the bank to pay the contested monies to the clerk

of the court.1 2

The appellants filed a motion to vacate the award of attor

neys’ fees based on Rule 60(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, and simultaneously filed a motion for stay of ex

ecution pending disposition of the Rule 60(b) motion. Short

ly thereafter, but before the writ was enforced, the State paid

the $27,272.65 judgment. In response to the voluntary pay

ment, the district court vacated, by order, the attachment of

the State’s bank account. The court also issued an order

denying appellants’ Rule 60(b) motion. It was from this

denial that the present appeal was perfected.

Rule 60(b), Fed. R. Civ. P., provides in pertinent part as

follows: “On motion and upon such terms as are just, the

court may relieve a party . . . from a final judgment, order,

or proceeding for the following reasons: . . . (4) the judg

ment is void . . . If, as appellants assert, the award of

attorneys’ fees and expenses against the State of Ohio was

void for lack of jurisdiction, we must reverse. A void judg

ment is a legal nullity and a court considering a motion to

vacate has no discretion in determining whether it should be

set aside. See generalhj, 7 J. Moore, Federal Practice, \\ 60.25

[2], at 301 (2d ed. 1973).

Before discussing the central issue in this case a few words

of clarification are in order. This cause, insofar as the award

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

April 25, 1974

1 “By previous o rd er . . . th e S ta te of Ohio w as o rdered to pay

P lain tiff’s a tto rneys’ fees in th is action. T he C ourt now being ad

vised th a t the S ta te of Ohio has failed and continues to refuse to

com ply w ith said o rder, now d irects th a t P la in tiff’s a tto rn ey s’ fees

and expenses be taxed as costs in th is action .”

2 “The C ourt being advised th a t th e re are funds being held in ex

cess in the am ount of $27,272.65, it is ORDERED th a t the Union C om

m erce B ank tu rn over and deliver funds m th e sum of $27,272.65

to the C lerk of this C ourt fo rth w ith ; said am ount rep resen tin g the

sum designated and levied upon by the F ieri Facias.” O rder of

F eb ruary 2, 1973.

13a

of attorneys’ fees is concerned, although nominally against the

chief executive and other officials of the State of Ohio, in

substance and effect was against the State.3 Any award of

attorneys’ fees, whether against the State of Ohio or its officials,

vitally affects the rights and interests of the State in preserving

its revenues. According to the general rule “a suit is against

the sovereign if ‘the judgment sought would expend itself on

the public treasury . . . .’ Land v. Dollar, 330 U.S. 731, 738

(1947) . . . .” Dugan v. Rank, 372 U.S. 609, 620 (1963);

accord, Dawkins v. Craig, 483 F.2d 1191 (4th Cir. 19/3).

And as this Court stated in Harrison Construction Co. v. Ohio

Turnpike Com’n., 272 F.2d 337, 340 (6th Cir. 1939), “When

the action is in essence one for the recovery of money from

the State, the State is the real, substantial party in interest

and is entitled to invoke its sovereign immunity from suit

even though individual officials are nominal defendants. See,

Kraus v. Rhodes, 471 F.2d 430 (6th Cir. 1972).

Appellants do not contend that state officials are immune

from suits brought to restrain unconstitutional acts undertaken

in their official capacities. The law clearly recognized the right

of an interested party to force state officials to act in accord

ance with the Constitution. Georgia R.R. and Banking Co.

v. Redwine, 342 U.S. 299 (1932); Ex parte Young, 209 U.S.

123 (1908); Lee v. Board of Regents of State Colleges, 411

F.2d 1237 (7th Cir. 1971); Samuel v. University of Pittsburgh,

56 F.R.D. 533 (W.D. Pa. 1972); Wright, Law of Federal

Courts, §48, at 183 (1970). Appellants do assert, however,

that both a state and its officials are immune from monetary

awards arising in connection with such a suit, even if the

awards are for attorneys’ fees.

To further sharpen the focus of this inquiry, we note that

in the instant case the district court ordered the attorneys’

3 T here can be no doubt th a t the d is tric t court in tended th e aw ard of

a tto rneys’ fees to ru n against the S ta te of Ohio, even though the

S tate w as not a p a rty to th is suit. A lthough the exact m eaning of the

court’s May 19, 1972 o rder, quoted in the tex t, is a rguab ly unclear,

any possible m is in te rp re ta tion was obviated by the J a n u a ry 17, 19/3

o rder (supra note 2), and by the subsequen t a ttach m en t of th e S ta te ’s

bank account.

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

April 25,1974

14a

fees taxed as costs, and ordered the State of Ohio to pay the

costs.4 We do not question the general principle that a court

may tax attorneys’ fees as costs under the appropriate circum

stances in cases involving private parties5 or where sanctioned

by statutory law,6 but it seems basic that if a party is immune

from an award of attorneys’ fees as such, that immunity is

not altered by taxing the fees as part of the costs. If the

award is void in one form, it is void in the other.

Stripped of distracting shadow questions, the case before

us presents a singular, although by no means simple, issue:

Does a federal court have the power to award attorneys’ fees

against a state or its officials acting in their official capacities

in a suit brought under 42 U.S.C. § 19S3 to vindicate consti

tutional rights? To this inquiry we must respond in the

negative.

The Supreme Court reviewed and clarified the principles

under which a federal court may award attorneys’ fees against

an unsuccessful litigant in Hall v. Cole, 412 U.S. 1 (1973).

The Court recognized the existence of a “class benefit” ration

ale for awarding fees where “plaintiff’s successful litigation

confers ‘a substantial benefit on the members of an ascer

tainable class . . . . ” ’ Id. at 5. The basis of tiffs theory is that

because the efforts of the individual plaintiff benefited a group

or class of persons, equity requires the group to share the

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

April 25, 1974

4 Order of January 17, 1973, supra note 1.

s “A lthough the trad itio n a l A m erican ru le o rd in arily d isfavors the

allow ance of a tto rneys’ fees in the absence of s ta tu to ry o r con tractua l

authorization, federal courts, in the exercise of th e ir eq u itab le pow ers,

m ay aw ard a tto rn ey s’ fees w hen the in te res t of ju stice so requ ires .”

H all v. Cole, 412 U.S. 1, 4 (1973). Ju s t ic e 'h a s been held to so req u ire

w here bad fa ith is exh ib ited by the unsuccessful litig an t or w here

“p la in tiff’s successful litigation confers ‘a substan tia l benefit on m em

bers of an ascerta inab le class Id. a t 5.

This C ourt has also recognized th e equ itab le pow er to m ake such

aw ards. Sm oot v. Fox, 353 F.2d 830 (6 th Cir. 1965).

W e take heed of the fact th a t in th is case th e re w as no evidence

of bad fa ith on the p a rt of appellan ts o r the S ta te of Ohio.

6 S ta tu tes often provide for aw ards of a tto rn ey s’ fees. See, e.g.,

C layton Act, 15 U.S.C. $ 15; C om m unications A ct of 1934, 47 U.S.C.

§ 206; In te rs ta te Com m erce Act, 49 U.S.C. § 16(2 ); etc.

15a

financial burden of the plaintiff's litigation. In the instant case,

that appellee’s prosecution of this suit to bring Ohio’s leg

islative districts within the requirements of the one man —

one vote rule benefited every Ohio voter is not questioned.

However, as the Supreme Court pointed out in Hall, the class

benefit theory can only be employed where the court has

the requisite jurisdiction to make such an award. 412 U.S.

at 5. In this case the district court clearly had jurisdiction

over the appellants insofar as the suit involved a plea for in

junctive relief to force constitutional reapportionment.

The Eleventh Amendment, however, contains an express con

stitutional limitation on the power of the federal courts.

“The Judicial power of the United States shall not be

construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, com

menced or prosecuted against one of the United States by

Citizens of another State or by Citizens or Subjects of any

foreign State.”

Through judicial interpretation, this amendment has been held

to bar a citizen who would bring suit against his own state.

Employees v. Missouri Public Health Dept., 411 U.S. 279

11973); Pardon v. Terminal Taj. of the Alabama State Docks

Dep’t., 277 U.S. 184 (1964). This amendment has also been

found to be the embodiment of the doctrine of sovereign

immunity. Adams v. Harris County, Texas, 316 F. Supp. 938

(S.D. Texas 1970), rev’d on other grounds, 452 F.2d 994 (5th

Cir. 1971). The sovereign immunity of the states is, then,

a limitation of federal judicial power, that is, on the consti

tutional grant of jurisdiction to the federal courts.

As stated heretofore, the Eleventh Amendment’s immunity

is unavailable to state officials where an action of constitu

tional proportions is brought for injunctive relief. Georgia R.R.

and Banking Co. v, Redminc, supra, etc. The rationale behind

the doctrine of sovereign immunity is the protection of the

states’ fiscal integrity.. See, Land v. Dollar, supra; Dugan v.

Rank, supra; Harrison Construction Co. v. Ohio Turnpike

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

April 25,197A

16a

Comn., supra. “Thus the rule has evolved that a suit by priv

ate parties seeking to impose a liability which must be paid

from public funds in the state treasury is barred by the Eleventh

Amendment.” Eclehnan v. Jordon, -12 U.S.L.W. 4419, 4422

7 U.S. March 26, 1974); accord, Kraus v. Rhodes, supra.

In Sincock v. Ohara, 320 F. Supp. 109S (Del. 1970), a reap-

portionment suit similar to the one at bar, a three-judge district

court concluded that an award of attorneys’ fees could not

be made against the State of Delaware because of the prohi

bition contained in the Eleventh Amendment. On the other

hand, appellees point out that in Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp.

691 (M.D. Ala. 1972), the district court awarded attorneys’

fees against Alabama’s state legislators, secretary of state, at

torney general and governor on the basis of the class benefit

doctrine. Unfortunately, it is impossible to determine from the

opinion whether the award was made against the above of

ficials in their official capacities or as private individuals, there

is no indication that the State of Alabama was held liable, and

the court did not deal with the Eleventh Amendment prob

lems presented here.7

Sims was appealed to the Supreme Court. Appellees assert

that the Supreme Court's affirmance of Sims, 409 U.S. 942

(1972), conclusively establishes a district court’s power to

award attorneys’ fees against a state in a suit brought to en

force constitutional rights. We do not agree. Sims v. Amos

was reported in two segments at the district court level: the

first report, dealing with the substantive reapportionment is