Lawson v. United States of America Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 30, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lawson v. United States of America Brief Amicus Curiae, 1949. 15be4fc2-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f1e031f9-5398-4b9d-b367-fbc64faf9bda/lawson-v-united-states-of-america-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Rue

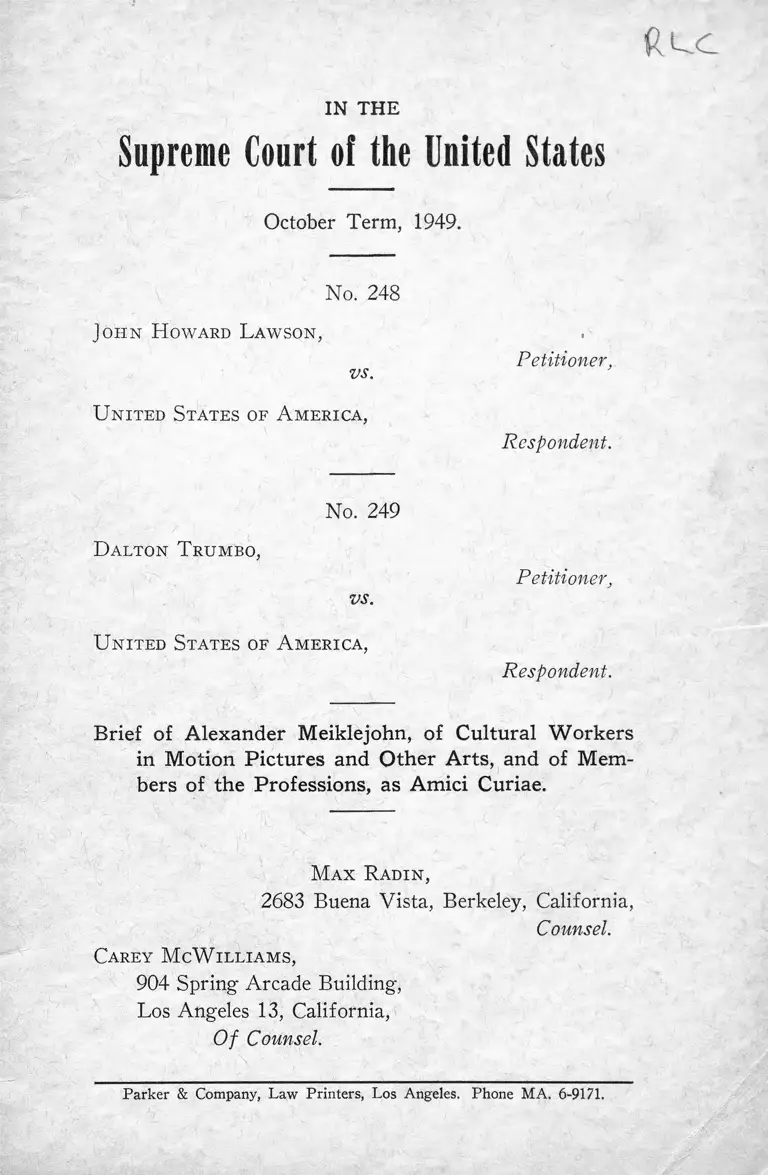

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1949.

No. 248

John H oward L awson,

vs.

U nited States of A merica,

No. 249

Dalton T rumbo,

vs.

U nited States of A merica,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

Petitioner,

Respondent.

Brief of Alexander Meiklejohn, of Cultural Workers

in Motion Pictures and Other Arts, and of Mem

bers of the Professions, as Amici Curiae.

M ax Radin ,

2683 Buena Vista, Berkeley, California,

Counsel.

Carey M cW illiams,

904 Spring Arcade Building,

Los Angeles 13, California,

O f Counsel.

Parker & Company, Law Printers, Los Angeles. Phone MA. 6-9171.

SUBJECT INDEX

PAGE

Freedom of expression............................................................. 12

The meaning of the hearings.........................................-................. 14

The triangle of pressure.................................................................... 18

Censorship in modern dress........................................................... 21

The illusion. of acceptance..................................... ........................ - 24

Economic subjugation .............. 27

The protection of ideas.................................................................... 29

Conclusion 36

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases. page

Child Labor Tax Case, 259 U. S. 20.......................~....................... 8

McDermott v. Pyle, 5 Parke Cr. (N . Y .) 102.................... ............ 34

Minor v. Happersett, 88 U. S. 162..................................................... 29

State v. Taylor, 47 Ore. 455, 8 Ann. Cases 627.............................. 34

United States v. Butler, 297 U. S. 1................................ -............ 8

United States v. Paramount Pictures, 334 U. S. 131.................... 8

M iscellaneous

A Free and Responsible Press (Univer. o f Chicago Press), pp.

6-9 ..................................................................... 30

Annals, American Academy of Political and Social Science, No

vember, 1938, p. 97, Freedom in the Arts.................................. 11

Annals, American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, No

vember, 1938, pp. 210-234, Hartshorne, The German Uni

versities and the Government.....................................- ................. 23

Annals, American Academy of Political and Social Science, No

vember, 1947, p. 82, The Motion Picture Industry.................... 10

Annals, American Academy of Political and Social Science, No

vember, 1947, pp. 22, 121, 122..................................................... 12

Bramstedt, Dictatorship and Political Police: The Technique

of Control by Fear (O xford Univer. Press, 1945, p. 137)..... 18

Byzantine Revision of the Corpus Juris, the Basilica (b. 60, 17) 17

Chafee, Free Speech in the United States (1941), pp. 17, 28-30,

154, 366, 529 ff. 545...................................................................... 11

Digest, Book 48, Title 19, Sec. 18................................................,.... 34

Hallowed, The Decline of Liberalism as an Ideology (1946),

p. 108 .................................................................................................. 26

Mirsky, History of Russian Literature (1927), p. 54.................... 21

New York Herald-Tribune, December 2, 1947, article by E. B.

White ....................................................- ...........................................- 34

New York Times, November 26, 1947, 1:2........................................ 17

PAGE

New York Times, April 1, 10, 1949...... .......................................... 21

House of Representatives Report No. 2, 76th Cong., 1st Sess.,

13, 1939 ........................................................ - .................................... 8

House of Representatives Report No. 1, 77th Cong., 1st Sess.,

24, 1941 ............................................................................................... 8

Sington and Weidenfeld, The Goebbels Experiment: A Study

of the Nazi Propaganda Machine (Yale Univ. Press, 1943),

Chap. IX , The Cinema in the Third Reich, pp. 211-223............ 25

Variety, Hollywood, April 13, 1949, Vol. 63, No. 28, p. 1........... 21

Statutes

Statute of Treason of 1350 (25 Edw. 3, st. 5, c. 2 ) .................... 34

United States Constitution, First Amendment.....................8, 9, 11

T extbooks

Broom, Legal Maxims (10th Ed. by Kersley, 1939).................... 34

47 Columbia Law Review, pp. 416, 428............................................ 8

3 Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, p. 291................................ 21

Kenny, Outlines of Criminal Law (15th Ed., 1936), pp. 41-42.... 35

4 Lawyers’ Reports Annotated (N . S.) 417................................ 34

14 University of Chicago Law Review, pp. 256, 267.................... 29

96 University of Pennsylvania Law Review, p. 399.................... 24

58 Yale Law Journal, p. 131............................................................. 23

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1949

No. 248

John H oward L awson,

vs.

U nited States of A merica,

No. 249

D alton T rumbo,

vs.

U nited States of A merica,

Petitioner.

Respondent.

Petitioner,

Respondent.

Brief of Alexander Meiklejohn, of Cultural Workers

in Motion Pictures and Other Arts, and of Mem

bers of the Professions, as Amici Curiae.

The following named cultural workers in motion pic

tures and other arts and members of the professions,

respectfully urge the favorable consideration by this Court

of the pending petitions for writs o f certiorari in the

above entitled cases for the reasons hereinafter set forth:

Alexander Meiklejohn and

From the M otion P icture Industry:

Sam Albert

Edward P. Bailey

Sol Barzman

Robert M. Bassing

Jeanne Bay less

Leon Becker

Laslo Benedek

Connie Lee Bennett

Seymour Bennett

Leonardo Bercovici

John Berry

Betsy Blair

Henry Blankfort

Michael Blankfort

Julian Blaustein

Phoebe Brand

Irving Brecher

Harold Buchman

Louis Bunin

Hugo Butler

Morris Carnovsky

Vera Caspary

Howland Chamberlin

Frances Chaney

Charles Chaplin

Maurice Clark

Angela Clarke

Frederick Cleary

Franklin Coen

John Collier

Richard Collins

Dorothy Comingore

Burt Conway

Jeff Corey

Howard Da Silva

Frank Davis

Jerome Davis

Nancy Davis

Olive Deering

I. A. L. Diamond

Howard Dimsdale

Walter Doniger

Jay Dratler

Peggy Dreis

Howard Duff

Marjorie Duffy

Philip Dunne

Arnaud d’Usseau

Leslie Edgley

Edward Eliscu

Guy Endore

Joseph Eger

Julius Epstein

Ross Evans

Jean Empson

Howard Feldman

Carl Foreman

Melvin Frank

David Fresco

Hugo W . Friedhofer

Anne Froelick

•3—

Jerry Gallard

John Garfield

Jody Gilbert

Augustus Goetz

Ruth Goetz

Ivan Goff

Lee Gold

S. L. Gomberg

Frances Goodrich

Don Gordon

Hilda Gordon

Lloyd Gough

James Gow

Farley Granger

Edward Gross

Margaret Gruen

Jerry Gruskin

Albert Hackett

Alvin Hammer

Louis Harris

Harold Hecht

Sig Herzig

Rose Hobart

Arthur Hoffer

J. Jerry Hoffman

Tamara Hovey

John Hubley

Edward F. Huebsch

Marsha Hunt

Ian McLellan Hunter

John Huston

Paul Jarrico

Robert Joseph

Gordon Kahn

Jay Kanter

Sol Kaplan

Robert Karnes

Roland Kibbee

Victor Killian

Mickey Knox

Arthur Kober

Howard Koch

Lester Koenig

H. S. Kraft

Burt Lancaster

Burton Lane

Arthur Laurents

W ill Lee

Robert Lees

Gladys C. Lehman

Isobel Lennart

Sonya Levien

Alfred Lewis Levitt

Melvin Levy

Norman Lloyd

Joseph Losey

Louella MacFarlane

Ben Maddow

Daniel Geoffrey Homes

Mainwaring

Arnold Manoff

Edward May

Edwin Justus Mayer

Gregory McClure

Kitty McHugh

Eve Miller

John Skins Miller

Frances Millington

4

Elick Moll

Karen Morley

Henry Myers

Leonard Neubauer

Mortimer Offner

Arthur Orloff

Norman Panama

Jerry Paris

Dorothy Parker

Irwin Parnes

Frank Partos

Kenneth Patterson

John Paxton

Leo Penn

Nat Perrin

Lester Pine

Phillip Pine

Elise Dufour Pinchon

Robert Pirosh

Abraham Polonsky

Stanley Prager

Robert Presnell Jr.

George W . Prior

Marian Prior

David Raksin

Elias Reif

Irving Reis

Anne Revere

Frederic Rinaldo

Ben Roberts

R. B. Roberts

Stephen Roberts

Robert Rossen

Selena Royle

Irving Rubine

Stanley C. Rubin

Shimen Ruskin

Robert Russell

Waldo Salt

Ruth Sanderson

Jack Scher

Wilton Schiller

Maxwell Shane

Victor Shapiro

Seymour Sheklow

Art Smith

Louis Solomon

Eugene Solow

Gale Sondergaard

Jan Sterling

Donald Ogden Stewart

John Strauss

Theodore Strauss

Jo Swerling

George Thomas

Cyril Towbin

Dorothy Tree

Paul Trivers

George Tyne

Michael Uris

Peter Viertel

Salka Viertel

Robert Wachsman

Sam Wanamaker

Joseph Warfield

Mel Waters

— 5-

John Weber

John Wexley

Lynn Whitney

Frances Williams

Mervin Williams

Michael Wilson

Richard Wilson

Robert E. Wilson

From Other A rts

Murray Abowitz, M.D.

Gregory Ain

Harmon Alexander

Robert E. Alexander

William Alland

Jack Agins, M.D.

Georgia Backus

Rev. Lee H. Ball

Bernard Baum

Irving Bieber, M.D.

Stella Bloch

Peter Blume

Alex Blumstein, M.D.

Theodore Brameld

Janet Brandt

John Brown

Cicely Browne

Allan M. Butler, M.D.

Jane Rosen Callender

Angus Cameron

Dr. A . J. Carlson

Harry Cimring, M.D.

Peggy Chantler

Jerome Chodorov

Helen F. Clark

P. Price Cobbs, M.D.

Shelley Winters

David W olfe

William Wyler

Frances Young

Nedrick Young

Fred Zimmeman

and P rofessions:

Marc Connelly

Thomas H. Creighton

Charles C. Cumberland

Michael Davidson

Albert Deutsch

William E. Dodd

Harl R. Douglass

Olin Downes

W . E. B. DuBois

Alice Dudley

Garrett Eckbo

Robert L. Einer

David Ellis

Robert H. Ellis, M.D.

Jerome Epstein

Paul S. Epstein

Tillman H. Erb

Lincoln Fairley

Hazel E. Field

Austin E. Fife

David Harold Fink, M.D.

Phyllis Frank

Lawrence J. Friedman,

M.D.

Dr. Arthur W . Galston

Ted Gilien

J. W . Gitt

Max Goberman

Sanford Goldner

Boris Gorelick

Shirley Graham

Elliott Grennard

Victor Gruen

Rev. Armand Guerrero

Uta Hagen

Dashiell Hammett

E. Y . Harburg

M. Robert Harris, M.D.

Kenneth Harvey

Frances Heflin

A. A. Heller

Regina Heller

Lillian Heilman

Victor Heyden

Stefan Heym

Ira Hirschman

W . E. Hocking

Tom Holland

John R. Holmes

Ernest A. Hutchinson,

M.D.

Garson Kanin

Lilian Kaplan

Doris Karnes

George Kast

Anne Kazarian

Rev. Albert Wallace

Kauffman

Milton Kestenbaum

John A. Kingsbury

Raphael Konigsberg

Peter Jona Korn

Kenneth N. Kripke

Jean LaCour

John Latouche

Jack Levine

Maxim Lieber

Irwin Lieberman

Oliver S. Loud

Robert J. Lynd

Norman Mailer

John Martin

Molly Mason

Lownder Maury

Leo Mayer, M.D.

Samuel D. Menin

Arnold D. Mesches

Myron Middleton, M.D.

Arthur Miller

Pat Miller

Virginia Mullen

Helen Clare Nelson

Clifford Odets

Father Clarence Parker

Erwin Panofsky

Linus Pauling

Alexander E. Pennes, M.D.

Thomas L. Perry, M.D.

Nels Peterson

Ralph S. Phillips

Richard M. Powell

Alan Reed

Anton Refreigier

Carroll H. Richardson

Wallingford Riegger

Ben Rinaldo

Holland Roberts

Stephen Roberts

7

Vivian Roberts

Paul Robeson

Jack Robinson

Mary Robinson

O. John Rogge

Edwin Rolfe

David Rosen

Dr. Arthur Rubinstein

John Sanford

Elf Scharlin

Charles Schlein

Dr. Artur Schnabel

Max Howard Schoen,

D.D.S.

Budd Schulberg

Frederick L. Schuman

John R. Scotford

Evelyn Scott

Prof. William R. Sears

Ben Shahn

Felice Shaw

Seymour Sheklow

Max A. Sherman, M.D.

Merle Shore

Wilma Shore

Samuel Silver

John Sloan

Pearl Somner

Rev. F. Hastings Smyth

Raphael Soyer

William Steig

Phillip Stern

Gene Stone

Helen Stone

Burt Styler

Carl Sugar, M.D.

George Tabori

Mary Tarcai

Joseph A. Thompson

Oswald Veblen

Louis Vittes

Don Waddilove

Joseph W . Warfield

Morris Watson

Max Weber

Herbert Weisinger

Gene Weltfish

Fritz W . Went

Frank W . Weymouth

James Waterman Wise

Ella Winter

Angers Wooley

William Zorach

Convinced that issues of as great importance as any

with which this court has had to deal o f recent years

are here presented, those responsible for this brief have

deemed it appropriate to elaborate upon a major social

issue raised by the appellant which happens to be o f spe

cial concern to them. This issue has to do with the ques

tion of censorship, first, as it affects rights guaranteed

— 8—

to the petitioner by the Constitution o f the United States;

and, second, as it relates to the utilization o f governmental

power by a committee o f Congress to impose a censorship

upon the motion picture industry. However since both

aspects of the matter are inescapably interrelated, they

have been dealt with in this brief as presenting a single

issue,-------censorship. In brief compass, it is our con

tention :

1. That Congress cannot impose a direct censorship

upon the motion picture industry since motion pictures

enjoy the same protection under the First Amendment

as the press and radio ( United States v. Paramount Pic

tures, 334 U. S. 131, 166). Any prosecution arising out

of an effort on the part o f Congress to impose a direct

censorship on the motion picture industry in violation

of the First Amendment could not, therefore, be sus

tained. Since Congress cannot impose a direct censor

ship upon the motion picture industry, it follows that

Congress cannot accomplish by indirection that which it

is powerless to accomplish by direct legislation ( United

States v. Butler, 297 U. S. 1; Child Labor Tax Case,

259 U. S. 20). On this point it is perhaps sufficient to

observe that members o f Congress have frankly stated

that one o f the main purposes of the House Committee

on Un-American Activities has been to accomplish by

exposure and publicity ends which Congress could not

lawfully accomplish by legislation (see: H. R. Rep. No.

2, 76th Congress 1st Sess. 13, 1939; H. R. Rep. No. 1,

77th Congress 1st Sess. 24, 1941; also, 47 Columbia Law

Review 416 p. 428).

2. That a careful consideration o f the record in this

case will show that the hearings out o f which appellant’s

conviction for contempt arose involved an attempt by

Congress to impose a censorship upon the motion picture

industry in violation of the First Amendment. Since

any effort by Congress, directly or indirectly, to impose

a censorship upon the motion picture industry would

involve an abuse of power, petitioner was not required

to lend his assistance to the committee’s unconstitutional

purpose. Furthermore petitioner was doubly justified

in refusing to assist the committee in this enterprise

when it became apparent that, as part of its scheme to

censor the industry, the committee was compelled to use

its power as an agency of government to censor his

thinking. In this manner the issue of censorship was

brought directly home to the petitioner, as a citizen, for

a surrender of his personal privilege or right would

necessarily have involved an acquiesence in the scheme

by which the committee sought to censor the industry.

The development of these contentions requires (1) a

brief statement of the nature of motion pictures as a

medium of mass communication and the character of the

hearings out of which the citation for contempt arose;

and (2) a consideration of certain features of modern

political censorships.

* * *

Motion pictures belong in the category of the free arts.

In a sense, the motion picture is a composite form in

which all the free arts find expression: dance, drama,

painting, sculpture, opera, pageant; the plastic and

graphic as well as the verbal and literary arts. As a

composite form, the making of motion pictures has an

influence on the other arts and is in turn influenced by

developments in these related arts (see: “The Motion

- 10-

Picture Industry,” Annals, American Academy o f Pol

itical and Social Science, November, 1947, p. 82). Motion

pictures have an extraordinary relevance to the mainten

ance o f the democratic ideal since they are essentially a

mass medium o f communication. The weekly world atten

dance at motion pictures is estimated at 235,000,000 (A n

nals, supra, p. 1) : the weekly attendance in the United

States has exceeded 85,000,000 ( Hearings, p. 1). In its ef

fectiveness as a form of mass communication the motion

picture can only be compared with press and radio; yet,

as Terry Ramsaye has pointed out, motion pictures exceed

both press and radio in the degree to which they are

capable of penetrating “ the great illiterate and semi

literate strata where words falter, fail, and miss” {A n-

nals, supra, p. 1). As an educational medium alone, the

motion picture possesses the utmost actual and potential

importance (see: Annals, supra, pp. 103-109). O f mo

tion pictures it has been said that: “ Perhaps no Other

industry touches so intimately and significantly the lives

o f so large a proportion o f the world’s population. In

deed, the motion picture is relatively less important as an

economic institution than as a social institution, function

ing, with varying degrees of effectiveness and desirability,

in the transmission o f artistic ideas, the portrayal o f

human character and human emotions, the description of

culture patterns o f diverse societal groups, the dis

semination of information concerning current affairs, and

the interpretation o f individual and social experiences.

No other industry has so firm and so universal hold upon

the popular imagination or so complete command of pop

ular interest” (comments o f Dr. Gordon S. Watkins,

Annals, supra, p. vii). It is precisely the social impor

tance of motion pictures which invests the issue of cen

sorship, in this case, with such commanding significance.

11

Freedom of artistic expression is, o f course, embraced

within the guarantees o f the First Amendment ( Free

Speech in the United States by Zechariah Chafee, Jr,

1941, 17, 28-30, 154, 366, 529 f f ., 545); and this freedom

turns on the freedom to develop and express ideas. The

birth of an idea and its expression are not two distinct

processes: an idea is born in the act o f expression or

creation. Freedom to the artist, however, means more

than mere freedom of expression for it includes all that

the artist really wants which is a chance to be heard.

“ Certainly,” writes Dr. W . Rex Crawford, “ the sym

phonic composer will find it a hollow freedom that per

mits him to put what notes he will on paper, if he cannot

find a conductor who will give his work a hearing. The

dramatist cannot remain satisfied with reading his bold

lines and presenting his novel situations to a group of

friends in his library, if every effort to obtain a theater

encounters new objections . . . It is small comfort

to have won an architectural contest if the design that

ranked second is the one the committee chooses to erect”

( “ Freedom in the Arts,” Annals, American Academy of

Political and Social Science, November, 1938, p. 97).

This is not to say that society must provide the composer

with an orchestra, the playwright with a theater, and

the author with a publisher or stand accused of having

denied the meaning of freedom in the arts. But it is to

insist that the artist’s freedom is violated when he is

denied a chance to have his work heard, regardless of

its merits, solely because o f his political beliefs or affilia

tions. Under these circumstances it is not merely an

individual right of expression that is violated; the de

nial extends to one aspect o f the process by which a

society expresses itself, by which a culture is transmitted,

by which social change is effected.

- 12-

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION.

Freedom of expression, in its related meanings, has a

special significance in the making of motion pictures.

Cost factors alone severely limit the number and kind

of “ ideas” that find expression in motion pictures. Fur

thermore motion pictures are at the mercy o f a mass

market o f a magnitude and heterogenity unknown to the

universe o f print or radio. It has been said, in fact,

that “ movies are far more dependent upon a mass refer

endum than are other media of communication” (see,

Annals, American Academy of Political and Social Sci

ence, November, 1947, pp. 22, 121, 122). These factors

more or less inherent in the nature of the medium, have

been re-enforced by the manner in which the motion

picture industry has developed as an institution. Because

motion pictures started as a medium of “ amusement”

and “ entertainment,” without any artistic pretensions, the

industry long sought to cultivate a distinction between

“ entertainment” and “ propaganda” as a means of min

imizing its social obligations and avoiding responsibility

for the fullest development of the new art form. The

distinction, o f course, is essentially unreal (see, Annals,

supra, p. 117). Any dramatic presentation which is

coherent enough to hold the attention and interest o f an

audience is in some degree entertaining; and, conversely,

the “purest” entertainment film is likely to have hidden

psychological or social implications. Hence the treatment

of non-conventional subjects is certain to bring forth

charges o f “ propaganda” just as the making o f “ pure

entertainment” films will be denounced as an evasion o f

social responsibility. In either case the charge stems

from the fact that a new art form has not yet been given

— 13—

a real measure o f freedom in the selection and treatment

o f ideas and subject matter. For it is obviously absurd,

and also unfair, to charge the industry with a lack of

social responsibility— or with political bias— and at the

same time to deny the industry that measure of freedom

which alone would stimulate a real sense o f responsibility.

That the industry has been “ unregulated” in the past does

not mean that it has been “ free.”

Those who engage in the production of motion pictures

in a democracy have a clear responsibility to further the

values upon which such a society is based (a responsi

bility which derives from the freedom of expression

which in theory is guaranteed in such a society); but

dictation, direct or indirect, is utterly at variance with

the idea of social responsibility. Censorship makes for

an evasion, not an acceptance, o f real social responsibil

ity. Like the press and radio, the motion picture industry

is subject to regulation in the public interest; but the

content and ideas o f motion pictures cannot be dictated

by a congressional committee any more than such a com

mittee could dictate the editorial policy o f the American

press. The real question we propose to discuss is, there

fore: Did the appellant’s conviction arise out o f an abuse

o f the congressional power of investigation or, stated

another way, did the committee, in its hearings in this

matter, seek to impose a censorship upon the American

film industry?

On this point it is important to note that the hearings

are entitled: “ Hearings Regarding the Communist In

filtration of the Motion Picture Industry.” At the open

ing session, the chairman expressly stated that the purpose

of the hearing was to determine the extent to which

— 14—

Communist influences,— which the chairman carefully

failed to define,— had infiltrated the motion picture indus

try in Hollywood ( Hearings, pp. 3, 9 ). Obviously this

statement had reference not to the question o f ownership

or control but to the question o f propaganda. In de

termining the purpose o f the hearing, therefore, it is

significant that the chairman, with the apparent approval

o f his colleagues, characterized the purpose in such a

manner as to make it unmistakably clear that the com

mittee was directly concerned with the content and ideas

o f the American film industry. It would be impossible, ob

viously, to determine the propaganda content o f American

films without making a systematic examination of the

output o f the industry for a stated period, picture by pic

ture, story by story, scene by scene.

The Meaning of the Hearings.

The real meaning of the hearings, however, is to be

found not in the stated purpose but in the actual utiliza

tion of official power by the committee: what it did as an

official agency o f government, how it proceeded, what it

accomplished. Although elaborately disclaiming any in

tention of imposing a censorship upon the industry ( Hear

ings, p. 73), this is precisely what the committee not only

sought to accomplish but actually succeeded in doing.

The record is replete with suggestions, advanced by the

chairman and other members of the committee, that the

industry should make “ anti-Communist” pictures {H ear

ings, pp. 28, 76, 106, 132, 144, 145, 146, 223, 227, 324).

Wholly unambiguous, these suggestions were made in a

tone and manner that carried clear overtones of compul

sion. The record is also full o f suggestions, emanating

from the chairman and other members of the committee,

15—

that the industry should make more pictures “ extolling

the American way of life” ( Hearings, pp. 29, 237, 307).

At the same time the industry was severely criticized

— and, more important, publicly criticized,— for having

made certain motion pictures which were discussed, by

name, at considerable length. It will also be noted that

the committee discussed with spokesmen for the industry

specific details having to do with the content and ideas

of films; references, for example, were made to films de

picting evil bankers and corrupt congressmen, with the

clear implication that the committee did not approve of

such characterizations. The objective of the use of o f

ficial governmental power in all o f this was clearly cen

sorial.

The same abuse of power, moreover, is betrayed in the

committee’s pre-occupation with the role of the writer

in the motion picture industry. Not only were the hear

ings largely concerned with writers, but the committee

consistently and carefully stressed the importance of

writers to the purpose of the inquiry ( Hearings, pp.

35, 58, 150, 225). The basis for the committee’s in

terest in writers is, of course, quite clear. In a com

posite art form like motion pictures, the writer occupies

a role or position that is of special interest to the censor.

Not that the writer is capable of infiltrating propaganda

into films— the manner in which the industry is organ

ized makes this a preposterous supposition,— but be

cause the writer, more directly than the other crafts

men, is concerned with the content and ideas of motion

pictures. The “ story” is the principal raw material of

the industry; every production starts with an idea;

and writers are the principal germinators and developers

— 16—

o f ideas in the industry (see: Annals, supra, pp. 37-40,

16).

It should also be noted that the committee was con

cerned not with writers in the abstract but with certain

writers; moreover, its concern with these writers was most

specific, namely, it wanted these writers discharged from

their positions and blacklisted in the industry. The record

discloses, most significantly, that the industry was re

luctant to discharge the writers under investigation; it

was also reluctant to adopt a policy which would be tanta

mount to a blacklisting of these writers in the industry

{Hearings, pp. 53, 65, 313, 471, 472). Almost from

the opening session, the committee brought pressure

to bear upon the industry spokesmen to force them to

discharge the writers who had been selected for investi

gation. At one point the chairman stated: “ W e hope that

by spotlighting these Communists you will acquire that

will,” meaning the will to dismiss the writers under in

vestigation {Hearings pp. 141-142). This was not one

o f the incidents o f the hearings; it was obviously a major

purpose. Not only was the suggestion repeatedly ad

vanced that the writers should be dismissed {Hearings

pp. 49, 50, 53) but at least one member of the com

mittee kept insisting that the Motion Picture Producers

Association should blacklist these men in the industry

{Hearings p. 18). In the context o f the hearings, these

suggestions must be regarded as more than mere casual

hints or gratuitous recommendations; they carried the

implied threat o f a directly imposed federal censorship

in case of noncompliance. What the committee clearly

set out to accomplish was a censorship of the industry

accomplished through the stratagem o f forcing the in

— 17—

dustry to discharge a selected group o f writers who were

identified with a point of view and set of ideas o f which

the committee disapproved. A purge of ideas was ac

complished through a purge of individuals associated or

identified with these ideas; in effect this type of censor

ship might be described as symbolic censorship. That the

committee succeeded in forcing the industry, against its

better judgment, to discharge the writers under investiga

tion, is merely another way of saying that it succeeded

in its strategy of imposing a censorship-by-indirection

upon the industry (see: New York Times, November 26,

1947, 1 :2).

As the history o f German and Italian fascism clearly

reveals, there can be no more effective censorship o f any

medium of communication than a purge o f the individuals

identified with ideas and points of view which the censors

want to expurgate. This is not, o f course, because the

individuals selected for the purge are necessarily persons

o f outstanding influence and ability; the purge is intended

to be symbolic. In the conquest of ideas, the taking of

ten hostages can in effect approximate the direct suppres

sion of certain ideas and points o f view. This is pre

cisely what Mr. Stripling had in mind when he asked a

spokesman for the industry: “ Don’t you think the most

effective way of removing those Communist influences

. . . . and I say Communist influences; I am not say

ing Communists; I am not accusing them all o f being

Communists . . . but don’t you think the most effective

way is the payroll route?” ( Hearings pp. 49-50). Seldom

has there been a more explicit statement o f a principle

basic to the strategy o f terror, namely, “ you take my life

when you do take the means whereby I live.”

— 18—

The Triangle of Pressure.

The three main “ nerves” which modern censorship

manipulates, it has been said, are coercion, bribery, and

persuasion, or, translated into practical policy, terror,

corruption, and propaganda. “ The totalitarian engineers,”

writes Dr. E. K. Bramstedt ( Dictatorship and Political

Police: The Technique o f Control by Fear, Oxford Uni

versity Press, 1945, p. 137), “ either threaten man with

dangerous insecurity, turning the screw on him by various

forms of terror, or they promise him a deceptive security

by the cash value o f corruption or the mental opium of

propaganda. In all these cases they reckon that man

will eventually prefer the security of complete submission

to the grave risks o f an independent attitude. Many

advantages o f an economic or social kind are promised

and sometimes granted. The mind of the masses is

filled with colorful suggestions of what is marked as good

or bad for them. It is the combination o f these three

agencies which constitutes the mental climate of a dic

tatorship. Terror, corruption, and propaganda are only

three different sides of the same triangle, and it is impos

sible to recognize its geometrical proportions without

taking all three into consideration. All three aim at

directing people according to a preconceived pattern of

thought and action. They reduce them to an attitude o f

docile passivity and make them the mere object o f intel

lectual hypnosis, however subtly applied. Man, when suc

cessfully approached by any of these three methods, does

not act but reacts, he does not think but follows a stim

ulus. At the end he is enchained by fetters o f which

he is often only vaguely aware.” (Emphasis added.)

— 19-

Propaganda by government is a method used to divest

the people o f their right to propagandize. The former

is destructive of democracy, the latter is necessary to it.

Only those who ignore the unmistakable contemporary

reality embedded in the analysis just quoted can be blind

to the fact that the logical and intentional consequence

o f the contempt citations in this case was the censorship

o f a particular point o f view and of certain ideas in the

making of motion pictures and, at the same time, an open

encouragement of certain other ideas and points of view.

Had the committee subpoenaed a group of newspaper

publishers and demanded of them that they discharge

and blacklist ten editorial writers, all associated with a

certain point o f view, the meaning could not have been

more unmistakable. To underscore the strategy o f the

hearings, it should be pointed out that the industry did

in fact adopt a general industry-wide “ non-Communist”

hiring policy. Coupled with the discharge and black

listing of the ten writers, the adoption of this policy

constituted the industry’s symbolic acceptance of the un

stated alternative offered by the committee, namely,

acquiescence in the plan o f censorship which we are sug

gesting or Congress will adopt a program of direct cen

sorship.

So far as other writers in the motion picture industry

are concerned, the effect of the discharge o f appellant

and his colleagues could only be : first, to discourage the

submission of any plot, story, or theme which might pos

sibly give rise to an inference that the author was identi

fied with or sympathetic toward the wide range of ideas

which the committee insisted that the industry should

suppress; and, second, to encourage every writer in the

-20-

industry to submit only those ideas, stories, and themes

which, by inference, would meet with the approval o f the

committee. The penalty for failure to comply with this

general policy o f caution can be most severe, namely,

dismissal from the industry. The fact that writers in

the industry are well paid (Hearings p. 73)— that the

prizes for conformity are high— only emphasizes the

ease with which an indirect censorship has been im

posed on the industry by a committee of the Congress.

For there was a dual— although closely related— purpose

in the strategy o f the committee: just as it sought to

coerce and bribe the writers o f the industry so it sought

to terrorize and corrupt the owners and/or managers

o f the industry. In effect the spokesmen for the in

dustry were compelled to submit to the will o f the com

mittee as the price to be paid for escaping direct censor

ship and other forms o f harassment including the possi

bility o f further public hearings. And there was, of

course, a third purpose: namely, propaganda for the mil

lions who followed the hearings in the press, on the radio,

or on the screen.

The plan of censorship devised by the committee has a

special significance to the individual writer or creative

artist in our society. In the past, as the Authors League

o f America Inc., has stated in a resolution bearing on

this case, censorship has commonly “ operated only against

a work produced and issued to the public, and only to one

work at a time . . . Here, however, we are faced with

a different form of censorship. Here the man himself

is proclaimed suspect . . . Indeed, the whole corpus

of a man’s work, past and future, is thus declared sus

pect” ( Hollywood on Trial, p. 146). To emphasize the

— 21-

meaning o f this statement, suffice it to say that Twentieth-

Century Fox Film Corporation, subsequent to the con

tempt convictions in this case, purchased a story by

Albert Maltz, one o f the writers here involved (New York

Times, April 1, 1949, April 10, 1949); and then suddenly

announced, under obvious pressure, that it would not

produce the story ( Variety, Hollywood, April 13, 1949,

Vol. 63, No. 28, p. 1), - - an act o f cultural vandalism

in one of its ugliest and crudest forms.

Censorship in Modern Dress.

The full meaning of the hearings out o f which appel

lant’s conviction arose, however, can only be understood

in terms o f the new censorship which has arisen to plague

our times. Although censorships change as times change

and new conditions arise, the basic idea o f all censorships

is the same: to protect an authority based on privilege

by a policy of suppressing ideas and opinions (Vol. I ll,

Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, p. 291). Hence the

scope o f most censorships is commensurate with the area

o f privilege under attack. For example, the most rigorous

o f old-style censorships, that o f Czarist Russia, left cer

tain areas of intellectual life open to free inquiry and,

even as to prohibited fields, was easily evaded (see: A

History of Russian Literature by Prince D. S. Mirsky,

1927, p. 54). Within the last quarter century, however,

a new censorship has arisen which differs in crucially

important respects from the censorships of the nineteenth

century.

Since the social crisis, as viewed by the modern censors,

is now “ total,” the scope o f the new censorships is all-

inclusive. Not only has the scope of censorship changed:

the methods and techniques of suppression have also

— 22-

changed. The rigor of any censorship will depend on

many factors, including the relative ease and speed of

communication. Since nearly anything said or written

stands a chance nowadays o f being heard or read by large

masses o f people, and in a brief period of time, modern

censorships aim, not merely at preventing or punishing

the expression of ideas, but at reaching back one step

further to control the process o f thought itself. Here

the scientific technical apparatus of modern times has

revolutionized the methods of censorships (see Bram-

stedt, supra, p. 1.)

The enforcement of conformity has been rightly called

the beginning o f modern dictatorships. Once the process

is launched it must be systematically extended until the

last vestige of resistance has been overcome. As Sir

Frederick Pollock once pointed out, there is nothing more

vicious or damnable than heresy, that is, if you believe

in heresy. To those who believe in political heresies,

there can be no limit to the right of the state to suppress

so grave an evil. The body politic must be “ purged” and

“ cleansed” of all “ undesirable” elements and no sooner

is the first purge effected than it develops that the purging

process must be continuous. Starting usually with the

civil service, the purge is rapidly extended to the labor

movement, the professions, until, in a thorough and

systematic manner, every social and occupational stratum

has been coordinated. At this point the party or agency

in charge of the purge usually undertakes a purge o f its

own ranks so as to further “ coordinate” the structure

of power that is being created in the guise of extirpating

heresies.

-23-

As rapidly as possible the censorship program is ex

tended to the entire educational system which is “ co

ordinated” through an attack on the concept of academic

freedom and a gradual denial, to students and faculty,

o f the right to entertain unorthodox views. In the social

sciences, objectivity quickly becomes a mirage and eventu

ally even the most academic disciplines are directed toward

“ the closest possible relationship with the national pol

itical needs o f our people” (Neuman, supra, p. 196; em

phasis added). The “ new” education is based, of course,

upon a thorough-going proscription o f unorthodox be

liefs and a systematic indoctrination that permeates every

field of inquiry and instruction. As in other areas of

social life, this coordination is largely achieved through

the taking o f “ hostages.” The coordination o f the Ger

man colleges and universities was brought about by the

dismissal of probably not more than 15 percent of the

academic teaching staff (see: “ The German Universities

and the Government” by E. Y . Hartshorne, Annals,

American Academy of Political and Social Sciences,

November, 1938, pp. 210-234). The key to the success

of this new technique of the token purge is to be found

in “ the effect that this politicization has on the remaining

academicians” (Neuman, supra, p. 196). In the civil

service, as in education, “ political reliability” becomes the

dominant concept. The Nazis brought about a remark

able “ coordination” of the German civil service by the

dismissal of not more than 10 percent of the bureaucrats

(see: Yale Lazu Journal, Vol. 58, p. 131).

As the enforcement of conformity proceeds it becomes

necessary for the censors to create a “ system o f interlock

ing fears” (Neuman, supra, p. 198). In fact the new

- 24-

censorship is to be distinguished from all censorships of

the past by its use o f modern technological innovations to

bring about an amazingly effective organization o f terror

with what appears to be a minimum show of force and

violence. Every resource o f modern technology is brought

to bear upon the problem of annihilating the last vestige

of resistance or opposition. As conformity becomes an

end in itself— an all-consuming public passion,— distrust

is practiced as a matter o f official policy. Thus the

suspect is guilty before he is arrested; counter-espion

age becomes the order of the day; and “ loyalty” becomes

a major obsession. Ostensibly designed to protect the

government against revolutionary overthrow by “ force

and violence,” the new censorship proceeds by force and

violence to overthrow the rights of the people.

The Illusion of Acceptance.

Although compelled to use force, the censors are also

anxious to create the illusion that their dictates are obeyed

out of the cheerful readiness o f a seemingly free people.

“ Every dictatorship,” writes Neuman (supra, p. 203), “ is

eager to create the impression of seeming normalcy essen

tial not only to visitors from foreign countries but to

its own citizens.” For this reason, the new controls pro

ceed by relative indirection; the indirect censorship is

preferred to direct control. As pointed out in the Uni

versity o f Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 96 at p. 399:

“ The pressure has been toward the development o f new

devices, untrammelled by such hard-won protective ele

ments (as civil rights), devices operating indirectly,

imposing new sanctions such as economic deprivation in

place o f fine and incarceration. The inclination has been

to draw within the operation of such techniques those

•25-

persons who, because of their position only on the fringes

o f groups formerly subject to criminal law, could not

otherwise be brought under governmental control” (em

phasis added). Among the factors which make the use of

such indirect techniques feasible is the great extension of

propaganda facilities. For example, all modern dictator

ships have been quick to use and control motion pictures

as part o f their propaganda apparatus (see: The Goebbels

Experiment: A Study o f the Nazi Propaganda Machine

by Derrick Sington and Arthur Weidenfeld, Yale Uni

versity Press, 1943, Chapter IX , “ The Cinema in the

Third Reich,” pp. 211-223, where it is pointed out, p.

215, that control o f personnel was one o f the means used

to coordinate the industry).

One o f the secrets of the success of the new censorship

is that it is far more brutal and coercive than it appears

to be; most o f its dictates, in fact, rest on implied sanc

tions. Laws are not needed to limit the right of free

speech; speech is just as “ free” as people feel free to

speak. The Commission on Freedom of the Press has

given an unequivocal “ Yes” in answer to the question,—

Is the freedom of the press in danger? Yet no laws

have been passed which would challenge the right of a

free press. Indeed the new censorship is an aspect of

the continued rapid growth of an undemocratic economic

structure of power in our society and o f the encompassing

insecurity which affects every element in the society, the

rich as well as the poor. It is this structure o f economic

power which has tended to rob civil rights of real mean

ing and significance. “ Liberalism,” as Dr. John H. Hal

lowed has reminded us, “ was not destroyed by the Nazis

. . . rather, the Nazis were the legitimate heirs to a

- 26-

system that committed suicide” ( The Decline o f Liberal

ism as An Ideology by Dr. John H. Hallowed, 1946, p.

108). In fact, liberalism has been steadily undermined

by the gradual disappearance of individual autonomy and

initiative in social and economic life. The new censors,

therefore, do not need to imprison armies; a handful of

strategically selected hostages, in each group or strata,

will suffice for their purposes.

“ Pressure” is the key word in the vocabulary o f the

new censorship. The entire weight of the economic struc

ture can be brought to bear, at any threatened point, in

the effort to enforce conformity. For the initial attack,

exponents of extreme points o f view are usually selected

since they can be relied upon to offer open and defiant

resistance to the censors. At the outset it is the in

transigent, the defiant, witness that the censors elect to

degrade and silence, not because this witness is regarded

as particularly “ dangerous” but because his humiliation

will have greater symbolic (i. e. propaganda) value than

would the humiliation o f a less defiant non-conformist.

It is not the deeds but the mental attitude of this witness

that invests him with importance in the eyes of the censor

(see: Bramstedt, supra, p. 25). Once the strategic host

ages have been selected, every variety o f pressure,—

coercion, bribery, and persuasion,— is brought to bear

to force them to recant. In fact recantation is the real

objective of the inquisition. For the new censorship

must convert or destroy; it feels menaced by silence. Set

in motion at the top, the pressures aimed at securing total

conformity are systematically applied throughout every

social and occupational strata. The prelude to recantation

is the breaking of the will to resist and resistances are

•27—

broken by myriad and convergent pressures. The aim of

Foche, the dreaded Minister of Police under Napoleon I,

as Bramstedt has pointed out, was “not so much the

annihilation of the caught bird, but the catching of others.

He did not believe so much in violent punishment, but in

enforced enlightenment. The prisoner could improve his

own position by enlightening the eager police . . . all

the worse for him if he failed to realize his own interest”

{supra, p. 24).

Economic Subjugation.

Economic subjugation is, of course, one of the most

effective pressures for conformity in our society. If the

recusant witness is a writer, do not bother to burn his

books (a book-burning might call attention to the en

croachment on civil rights); simply blacklist him with

editors and publishers. Make it difficult for him to com

municate with his audience and dangerous for his audience

to communicate with him. Convey to him by a thousand

suggestions, often subtle, always brutal, an awareness of

the fact that certain themes are regarded as “ subversive.”

Dangle rich prizes for conformity before his eyes and

rely upon enlightened self-interest to police his thoughts.

Make it impossible for him to earn a livelihood by his

craft if he fails to conform. Destroy his self-confidence.

Create such an atmosphere o f hostility toward him that

even his children will be shunned by the children of con

formists. If he is a clergyman, talk to his trustees. If

he is a lawyer, pressure his clients to pressure him.

Through skillfully directed propaganda, make this

recusant witness a social and moral pariah in the com

munity. Label him; smear him; force him to recant;

or, indirect pressures failing, destroy him. But, all the

•28-

while, be at great pains to deny that any “punishment”

is being inflicted or that any ostracism is intended. Cam

paigns of this character can be organized without the

enactment of a single statute infringing civil rights. For

the undemocratic structure of economic power is used to

provide the unvoiced threat, the unstated sanction, that

can convert a “hint” into a command, a suggestion into

a threat.

Those on whose behalf this brief is filed have read the

record of the hearings out of which this prosecution arose

with a feeling of deep shame and outrage. From first

to last the record is one that reflects no credit on American

institutions or ideals. We refer not merely to the ob

jectives of the committee but to the manner and method,

the tone and temper of the hearings. There was no

“hearing” in this matter within any rationally defined

meaning of the term; what took place was more in the

nature of an ideological lynching, a form of psycholog

ical warfare conducted on grossly unequal terms. Every

effort was made to humiliate appellant, ostensibly a mere

witness before the committee; to focus an image of him

on the mirror of American public opinion of such calcu

lated distortion as to make him an object of universal

hatred and contempt. Indicative of the committee’s sense

of fairness is the fact that it brought a parade of

“friendly” witnesses to the stand and permitted and en

couraged these witnesses to defame appellant and his

colleagues without giving the latter any opportunity to

protect their reputations. No opportunity whatever was

offered the appellant to cross-examine these witnesses or

to call witnesses in his own behalf or to make a state

ment. The more violent and abusive the friendly wit-

— 29—

nesses became, the more the committee beamed its ap

proval. All the facilities o f press, radio, and motion

pictures were enlisted to make the humiliation of the

appellant a nationwide spectacle (see: 14 University of

Chicago Law Review 256, p. 267).

The proceedings out of which this prosecution arose

are poisoned with a bigotry and petty malice that, even

in the brief span o f time that has elapsed since the hear

ings, incites utter amazement and incredulity. It is,

indeed, hard to believe that it was a committee o f the

Congress of the United States which conducted this

witch-hunt. As Chief Justice Waite pointed out in Minor

v. Happersett [88 U. S. 162]: “ Allegiance and protec

tion are reciprocal obligations. The one is a compensation

for the other; allegiance for protection and protection for

allegiance.” But here a committee o f the Congress with

drew the protection o f due process from a group of citi

zens o f the United States in the course of an inquiry

into their allegiance to the government,-------a most un

pleasant spectacle to recall, even in retrospect.

The Protection of Ideas.

W e are not so much concerned, however, with the lack

o f due process in the hearings or the personal injustice

done appellant, as we are with the threat of censorship

implicit in this proceeding, the censorship not only of a

most important medium of mass communication but of the

thought-processes of every craftsmen connected with mo

tion pictures. Still more are we concerned with this

censorship as it constitutes a denial that the American

people are capable of self-government. The guarantees

of the First Amendment secure a public purpose as well

as a private right and the public purpose has nowhere

— 30 —

been more clearly stated than in the Report o f the Com

mission on Freedom of the Press (A Free and Respon

sible Press, University of Chicago, 1947, pp. 6-9) :

“ Freedom of the press is essential to political lib

erty. Where men cannot freely convey their thoughts

to one another, no freedom is secure. Where free

dom of expression exists, the beginnings o f a free

society and a means for every extension of liberty

are already present. Free expression is therefore

unique among liberties: it promotes and protects all

the rest. It is appropriate that freedom of speech

and freedom of the press are contained in the first

o f those constitutional enactments which are the

American Bill o f Rights.

Civilized society is a working system of ideas. It

lives and changes by the consumption o f ideas.

Therefore it must make sure that as many as pos

sible o f the ideas which its members have are avail

able for its examination. It must guarantee freedom

of expression, to the end that all adventitious hind

rances to the flow o f ideas shall be removed. More

over, a significant innovation in the realm of ideas is

likely to arouse resistance. Valuable ideas may be

put forth first in forms that are crude, indefensible,

or even dangerous. They need the chance to develop

through free criticism as well as the chance to sur

vive on the basis o f their ultimate worth. Hence

the men who publish ideas require special protection.

* * *

Across the path o f the flow of ideas lie the exist

ing centers o f social power. The primary protector

o f freedom o f expression against their obstructive

influence is government. Government acts by main

taining order and by exercising on behalf o f free

speech and a free press the elementary sanctions

—31

against the expressions of private interest or resent

ment: sabotage, blackmail, and corruption.

But any power capable of protecting freedom is

also capable of endangering it. Every modern gov

ernment, liberal or otherwise, has a specific position

in the field o f ideas; its stability is vulnerable to

critics in proportion to their ability and persuasive

ness. A government resting on popular suffrage is

no exception to this rule. It also may be tempted

— just because public opinion is a factor in official

livelihood— to manage the ideas and images entering

public debate.

If freedom of the press is to achieve reality,

government must set limits on its capacity to inter

fere with, regulate, or suppress the voices o f the

press or to manipulate the data on which public

judgment is formed.

Government must set these limits on itself, not

merely because freedom of expression is a reflection

of important interests of the community but also

because it is a moral right. It is a moral right be

cause it has an aspect o f duty about it.

It is true that the motives of expression are not

all dutiful. They are and should be as multiform

as human emotion itself, grave and gay, casual and

purposeful, artful and idle. But there is a vein of

expression which has the added impulsion of duty,

and that is the expression o f thought. I f a man is

burdened with an idea, he not only desires to express

it; he ought to express it. He owes it to his con

science and the common good. The indispensable

function of expressing ideas is one o f obligation

— to the community and also to something behind

the community— let us say to truth. It is the duty

o f the scientist to his result and o f Socrates to

— 32—

his oracle; it is the duty o f every man to his own,

belief. Because of this duty to what is beyond the

state, freedom of speech and freedom o f the press

are moral rights which the state must not infringe.

The moral right o f free expression achieves a

legal status because the conscience of the citizen is

the source o f the continued vitality o f the state.

Wholly apart from the traditional ground for a free

press— that it promotes the ‘victory o f truth over

falsehood’ in the public area— we see that public

discussion is a necessary condition of a free society

and that freedom of expression is a necessary con

dition o f adequate public discussion. Public dis

cussion elicits mental power and breadth; it is es

sential to the building of a mentally robust public;

and, without something o f the kind, a self-gov

erning society could not operate. The original source

of supply for this process is the duty o f the indi

vidual thinker to his thought; here is the primary

ground o f his right.

This does not mean that every citizen has a moral

or legal right to own a press or be an editor or have

access, as o f right, to the audience of any given

medium of communication. But it does belong to

the intention of the freedom of the press that an

idea shall have its chance even if it is not shared by

those who own or operate the press. The press is

not free if those who operate it behave as though

their position conferred on them the privilege of

being deaf to ideas which the processes of free speech

have brought to the public attention.” (Emphasis

added.)

In this country we have never acquiesced in the proposi

tion that persons could be punished for their beliefs any

more than we have approved the theory that beliefs per se

-33 -

can be banished from men’s minds by fear or compulsion.

Belief is a domain that lies beyond speech and statement.

Freedom of speech and of press are indispensable aspects

o f self-government; but freedom of belief rests on our

concept o f the moral freedom of the person. W e have

always insisted that the person must be regarded as

morally free since only by this insistence are we justified

in drawing the inference of responsibility upon which

the theory of self-government rests. Under our system

of government, therefore, we do not reject a policy by

arresting the persons who have proposed it. "The essence

of our political theory,” writes Mr. E. B. White (New

York Herald-Tribune, December 2nd, 1947), “ in this

country is that a man’s conscience shall be a private, not

a public affair, and that only his deeds and words shall

be open to survey, to censure and to punishment. The

idea is a decent one, and it works. It is an idea that

cannot safely be compromised with, lest it be utterly

destroyed. It cannot be modified even under circum

stances where, for security reasons, the temptation to

modify it is great . . . One need only watch totali

tarian at work to see that once men gain power over

other men’s minds, that power is never used sparingly and

wisely, but lavishly and brutally and with unspeakable

results. I f I must declare today that I am not a Com

munist, tomorrow I shall have to testify that I am not a

Unitarian. And the day after that I have never belonged

to a dahlia club. It is not a crime to believe anything at

all in America.”

— 34—

The American tradition, in this respect, merely follows

the established maxim of the law which runs Cogitationis

poenam nemo meretur ( “ No one deserves punishment for

his thought” ). In one form or another this maxim oc

curs in all the standard collections o f maxims, including

the one o f Broom (10th ed. by Kersley, 1939). It is cited

as an authoritative statement o f law in our courts. Cf

McDermott v. Pyle, 5 Parke Cr. (N . Y .) 102; which

again is cited for this maxim in State v. Taylor, 47 Ore.

455, 8 Ann. Cases 627; 4 L. R. A. N. S. 417.

The maxim is derived from the Corpus Juris o f Jus

tinian. It appears in the Digest, Book 48, Title 19, Sec.

18, and is there quoted from the great jurist, Ulpian, who

died in 228 A. D. It was regarded as sufficiently im

portant so that, brief as it is, it forms a section of the

title by itself. It was repeated in the Byzantine revision

o f the Corpus Juris, the Basilica (b. 60, 17), put to

gether in the ninth century. The Glossators o f the thir

teenth century note it particularly and cite other illus

trations. It is a well-known fact that these Glossators

exercised a considerable influence on the founders o f the

common law, especially on Bracton.

Even in the common law of treason, where it has been

frequently declared that there is an exception to this prin

ciple, because under the Statute of Treason o f 1350 (25

Edw. 3, st. 5, c. 2) “ imagining” or “ compassing” the

death of the King was included, it has been pointed out

that the statute itself— which in part has been taken over

into the Constitution of the United States— demands quite

— 35—

explicitly an overt act as proof o f the “ imagining” and

“ compassing.” And in the revival o f the statute in the

first year of Mary (1553) there is an express denuncia

tion, in the preamble, o f those who punish people for

words alone “ without fact or deed.” The notion that

thoughts could be punished, without even words, would

have been abhorrent even during the quasi-absolutism of

the Tudors. Cf. Kenny, C. S. Outlines o f Criminal.Law,

15th ed. (1936) 41-42.

The maxim cogitationis poenam nemo meretur was

widely quoted by civilians and canonists. Every now

and then it was uneasily explained away by some jurists

in their eagnerness to carry out the arbitrary decrees of

their masters. But the great majority pointed out that

these “ interpretations” were perversions. The maxim

was not a casual assertion; on the contrary, it was placed

in a deliberately conspicuous position in the Digest title

called, “ On Punishment,” which dealt with the theory and

practice of punishment under the law. It is worthy of

note that in a dictionary of canon and civil law of 1759,

edited by Bynkershoek, the maxim is quoted with the con

cluding words coram terreno tribunali, “ before an earthly

tribunal.” The suggestion is made, therefore, that before

a heavenly tribunal thoughts might be punishable. Wheth

er or not the Committee on Un-American Activities o f the

House of Representatives feels that it can claim a standing

higher than that of an earthly tribunal we need not con

jecture but we may assume that this Court makes no

such pretension.

- 36-

Conclusion.

Concerned as we are with the social implications of the

issues in this case, we most respectfully urge the court

to decide these issues upon the basis of broad principle

and in a manner that will provide a real guide to American

policy. A reversal of the petitioner’s conviction will not

necessarily settle the issue discussed in this brief but a

reversal based upon the guarantees of the First Amend

ment would go far toward arresting the trend toward

censorship o f thought and opinion of which this case is

a most significant manifestation. In the last three decades,

this court has vindicated and upheld the guarantees o f the

First Amendment in a manner and with a courage that

is quite beyond praise. Now the court is being asked,

in this case, to vindicate these same guarantees against

encroachment by the federal Congress in an abuse of the

important power of investigation. W e can appreciate

the seriousness of the issue which is thus presented to the

court but we are convinced that the mere fact that the

transgressor in this instance happens to be a committee

of the Congress will not blunt the force of the precedent

with which this court has upheld the American Bill of

Rights.

M ax R adin ,

Counsel.

Carey M cW illiam s,

O f Counsel.

Service o f the within and receipt o f a copy

thereof is hereby admitted this................ day of

September, A. D. 1949.

9-15-49— 5000