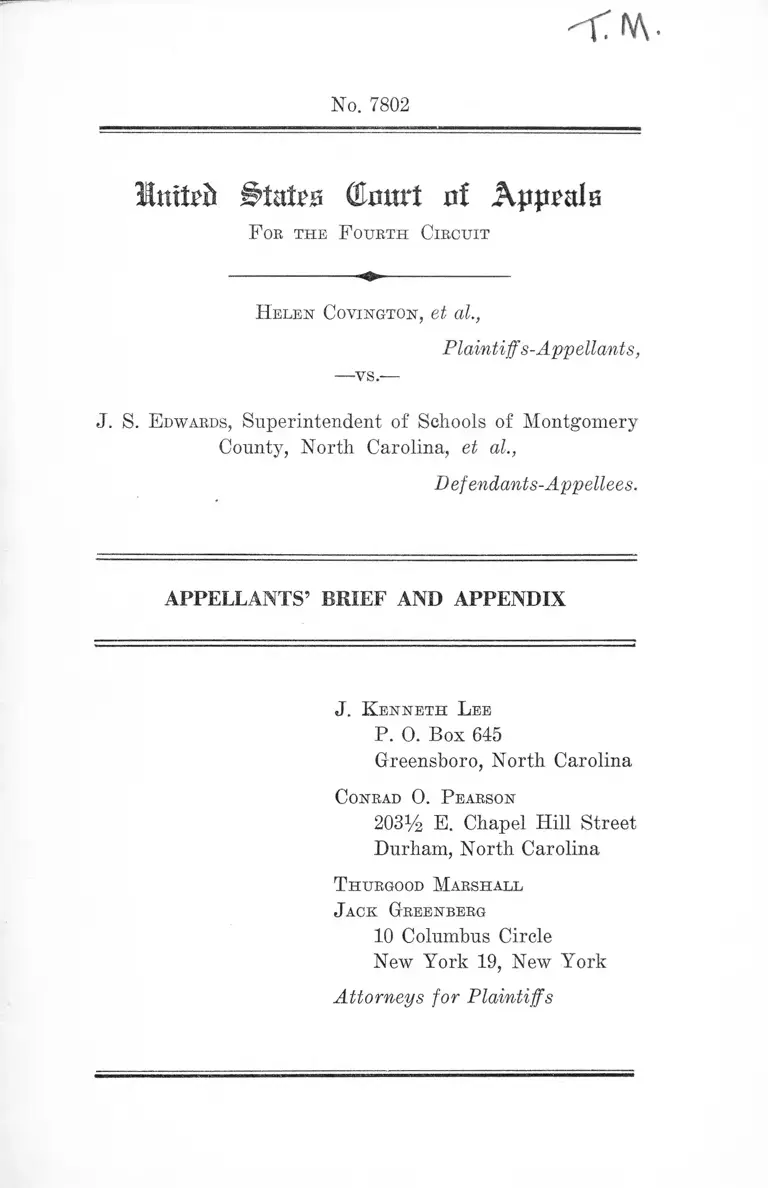

Covington v. Edwards Appellants' Brief and Appendix

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Covington v. Edwards Appellants' Brief and Appendix, 1958. 377aa77e-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f1e266c4-591d-41eb-b4a8-75bcf641044f/covington-v-edwards-appellants-brief-and-appendix. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

< < v \ -

No. 7802

Mmirit §>tatw Olimrt nf Appeals

F oe t h e F o u r t h C ir c u it

---------------------- ----------------------------

H e l e n C o v in g t o n , et al.,

Plaintiff's-Appellants,

—vs.—

J. S. E d w a r d s , Superintendent of Schools of Montgomery

County, North Carolina, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF AND APPENDIX

J . K e n n e t h L ee

P. O. Box 645

Greensboro, North Carolina

C o n r a d 0 . P e a r s o n

203% E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of the Case .................................................... 1

Questions Presented ....................................................- 4

Statement of the F a cts .................................................. 4

Argument .......................................................................... 7

Conclusion ............. .............. ............ ................... -.......... 17

A p p e n d ix ................................. -..................................................... l a

Petition............................................................................. l a

Complaint......................................................................... 4a

Amendment to Complaint.............................................. 10a

Answer ................................................ l^a

Petition of North Carolina Advisory Committee....... 27a

O rder............................ ^9a

Ruling on Motion to Strike............................................ 30a

Order ................................................................................. ^2a

Answer to Amendment to Complaint.......................... 35a

Motion for Leave to File Supplemental Complaint.... 36a

Amended and Supplemental Complaint ................—- 39a

Motion to Dismiss............................................ 48a

PAGE

Opinion .......................................................................... 49a

Judgment ............................................ 55a

C a se s :

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C., 1955) 13

Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County,

277 F. 2d 789 (4th Cir., 1955).................................... 7

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir., 1956) ..... 7

City Bank Farmers Trust Co. v. Schnader, 291 U. S.

24 (1934) .................................. 11

Cooper v. Aaron, —— U. S .-----, 3 L. ed. 2d 5 (1958) 11

Covington v. Montgomery County School Board, 139

F. Supp, 161 (M. D. N. C., 1956) .............................. 2

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 246 F. 2d 913

(5th Cir., 1957) ............................................................ 10

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915) ............. 12

Gully v. Interstate Natural Gas Co., 82 F. 2d 145 (5th

Cir., 1936) ................................................................... . 11

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm

Beach County, 258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir., 1958) ......... 9

Jeffers v. Whitley, 165 F. Supp. 951............................ 3,14

Kelly v. Board of Instruction of the City of Nash

ville, 159 F. Supp. 272 (M. D. Tenn., 1958) ............. 10

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education,

162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala., 1915) .......................... 9,12

United States Alkali Export Assoc, v. United States,

325 IT. S. 196 (1945)

11

11

Ill

S t a t u t e s :

PAGE

N. C. Gen. Assembly Resolution No. 29 (1955)........... 3

N. C. Gen. Stats, c. 115.................—..........................2, 8,15,16

N. C. Spec. Leg. Sess. Resolution of Condemnation

and Protest, Aug., 1956 .............................................. 3

O t h e r A u t h o r i t i e s :

Clark, Desegregation: An Appraisal of the Evidence

(1953) .............................................. -............ ............... 13

Report of the North Carolina Advisory Committee

on Education (1956)....... ............ ................................ 16

Shoemaker (ed.), With All Deliberate Speed (1957) 13

Williams and Ryan, Schools in Transition (1954)..... 13

States (tart ai Appeals

F oe t h e F o u r t h C ib c u it

H e l e n C o v in g t o n , et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

—vs.—

J. S. E d w a r d s , Superintendent of Schools of Montgomery

County, North Carolina, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case

The complaint in this action was filed on July 29, 1955

as a class action by thirteen adult plaintiffs personally and

as the next friends of forty-five minor plaintiffs on behalf

of themselves and all other citizens residing in Montgomery

County, North Carolina, similarly situated. The plaintiffs

are Negroes and the minor plaintiffs are eligible to attend

the public schools of Montgomery County, North Carolina.

The gravamen of the complaint is that defendants are main

taining a policy of segregating the schools in Montgomery

County, North Carolina contrary to the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution (App. 4a, 7a, 49a,

50a). The following proceedings then ensued.

August 12,1955: the complaint was amended to challenge

the constitutionality of certain North Carolina constitu

tional provisions without, however, changing the nature of

2

the cause of action (App. 10a); plaintiffs moved for a three-

judge court at this time and said motion was denied (App.

50a).

September 12,1955: defendants answered, alleging plain

tiffs’ failure to exhaust administrative remedies and that

plaintiffs lacked good faith in bringing the action (App.

12a, 50a). On motion of plaintiffs the allegations concern

ing lack of good faith were stricken (App. 30a).

December 16,1955: plaintiffs, by leave of court, amended

their complaint to allege that defendants are officers of the

State of North Carolina and enforcing and executing state

statutes and policies (App. 33a, 35a, 50a).

February 23, 1956: plaintiffs petitioned for reconsidera

tion of the order denying motion for a three-judge court,

which once more was denied. Covington v. Montgomery

County School Board, 139 F. Supp. 161 (M. D. N. C., 1956)

(App. 51a).

September 13, 1956: plaintiffs filed a motion for leave to

file an amended and supplemental complaint and add par

ties defendant (App. 36a, 51a). This supplemental com

plaint alleged the unconstitutionality of certain state laws

known as the Pearsall Plan1 and it sought to make parties

1 b) That at its 1955 session, the North Carolina General Assembly

rewrote Chapter 115 of the General Statutes o f North Carolina, that Article

21, Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of North Carolina as amended in

1956, provides for the assignment of pupils in the public school system of

North Carolina; that on or about the 23rd day of July, 1956 the North

Carolina General Assembly, in special session passed an act amending Chapter

115 of the General Statutes by adding Articles 34 and 35 and revising Article

20, Section 166. That said Amendments, commonly known and referred to as

the “ Pearsall Plan,” authorized educational expense grants, local option and

to suspend operation of public schools, and revised the Compulsory School

Attendance Laws; that the said acts of the General Assembly hereinbefore

referred to were ratified by vote of the people September 8, 1956; that the

said acts hereinbefore referred to have as their singular and sole purpose and

effect the continuation of racial segregation in the public schools of this said

3

defendant the members of the State Board of Education and

the Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of

North Carolina. The Attorney General of the State of

North Carolina made a special appearance on behalf of

members of the board in opposition to plaintiffs’ motion

(App. 51a). At the same time those who theretofore had

been defendants made a motion to dismiss the original com

plaint for failure to state a claim upon which relief could

be granted (App. 48a, 51a).

October 6, 1958: the Honorable Edward M. Stanley,

Judge of the United States District Court for the Middle

District of North Carolina, entered judgment (1) dismiss

ing the action and (2) denying the motion to file the

amended and supplemental complaint. The opinion of the

court dismissed the complaint for failure of plaintiffs to

have exhausted administrative remedies (App. 52a-54a).

It also denied the motion to add the State Board of Educa

tion and the State Superintendent of Public Instruction as

parties for reasons stated more fully in the court’s opinion

in Jeffers v. Whitley, 165 F. Supp. 951 (M. D. N. C., 1958).

It should be observed that the North Carolina Advisory

Committee on Education petitioned the court for the right

to appear in this case, take depositions and otherwise par

ticipate (App. 27a, 28a), that said motion was granted

(App. 29a), and that a further motion of said Committee

was granted allowing it to be present at any legal proceed

ings in the action (App. 32a). The questions presented

herein are raised, of course, by the court s action in so dis-

;State by circuitous methods that will abort, modify, nullify or defeat the

spirit and purpose of -the laws of the United States.

e) That the public policy of the -State of North -Carolina, as declared by

the General Assembly by Resolution No. 29 passed on the 8th day of April,

1955 and by Resolution of -Condemnation and Protest passed in Special Legisla

tive Session, August, 1956, is to continue segregation -of the races in public

education; that said public policy is in violation of the Constitution and laws

of the United States (App. 44a).

missing the complaint and denying the motion to add

parties.

Questions Presented

1. In a case wherein plaintiffs do not seek assignment

to any particular school, but merely pray for the abolition

of a policy of segregating the public schools, was the com

plaint properly dismissed for failure to exhaust adminis

trative remedies?

2. In a case wherein a proposed supplemental and

amended complaint seeks to add the State Board of Educa

tion and the Superintendent of Public Instruction of the

State of North Carolina as parties, was the motion to file

said complaint properly denied when it alleged that sections

of the North Carolina law commonly known as the Pearsall

Plan were enacted for the purpose of continuing racial

segregation in the public schools of North Carolina; and

that the County Board in refusing to desegregate the

schools did so pursuant to orders, resolutions or directives

of the State Board of Education and the Superintendent of

Public Instruction?

Statement of the Facts

This case involves the issue of whether plaintiffs may

enjoin the segregation policy of defendant County Board

of Education. Before the commencement of the action

appellants submitted a petition to defendants which is ap

pended to defendants’ answer alleging that defendants were

maintaining racial discrimination in their school system

notwithstanding the decision of the United States Supreme

Court that such racial discrimination is unconstitutional.

Petitioners pray that the schools under defendants’ juris

diction be desegregated (App. 23a-24a). The case com

5

menced with a petition that the court appoint adult plain

tiffs as next friends for the purpose of bringing this action

“ for the purpose of enjoining the said officials from denying

these plaintiffs and others similarly situated admission to

the public schools of Montgomery County on a non-segre-

gated basis contrary to the Constitution of the United

States and the laws enacted pursuant thereto * * * ” (App.

la, 2a). The complaint is brief and simple and demands

no admission to any particular school. It merely states

“On September 7, 1954 plaintiffs petitioned the Board of

Education of Montgomery County to abolish segregation

in the schools in their district. Said board refused to de

segregate the schools within its jurisdiction” (App. 7a).

The prayer of the complaint requests that:

The Court issue interlocutory and permanent injunc

tions ordering defendants to promptly present a plan

of desegregation to this Court which will expeditiously

desegregate the schools in Montgomery County and

forever restraining and enjoining defendants and each

of them from thereafter requiring these plaintiffs and

all other Negroes of public school age to attend or not

to attend public schools in Montgomery County because

of race (App. 9a).

The answer to the complaint states:

At the time of the filing of the petition by the plaintiffs

the Board of Education of Montgomery had no au

thority and was powerless to take any action on said

petition under the Statutes of North Carolina then in

full force and effect (App. 14a).

Said answer further recites a resolution of the county

board denying said petition (App. 15a) and stating that

while awaiting the decision of the United States Supreme

Court on the mode of implementing its desegregation deci

6

sion “ the board deems it for the best interest of public

education to await the final decree of the court and in the

meantime operate the public schools of North Carolina [as]

now constituted” (App. 15a). Thereafter, following said

implementation decision the board appointed an advisory

committee to study the issue which resolved that :

Now, therefore, be it resolved that the Public Schools

of Montgomery County operate during the 1955-56

term with practices of enrollment and assignment of

children similar to those in use during the 1954-55

school year, and that this resolution be the authority

for the County Superintendent and the various district

school principals and officials to so act (App. 18a, 19a).

Said resolution further said that pending a complete study

of the school law as amended and of any and all new laws

relating to operation of public schools, any parent or

guardian may file a written application with the principal

of a school to which it is desired that said child be en

rolled. Various criteria were set forth which were deemed

relevant to whether such application should be granted

(App. 19a). The answer went on to state that the board and

its committees “have continued to make a study of the prob

lems involved in the operation of the schools in Montgomery

County to the end that the operation of such schools may

lawfully be continued and that the schools may be preserved

for all the children of the County” (App. 20a). This an

swer was adopted and ratified on January 19, 1956 in

response to an amendment to the complaint (App. 35a).

The motion to dismiss which was filed subsequent to

this answer, although it did not so state, apparently was

a motion for judgment on the pleadings pursuant to Rule

12c. It is, therefore, the status of the case, and presumably

defendants would not deny, that at present they continue

7

to operate the schools of Montgomery County as stated in

the two answers: i.e., in the manner in which they were

operated prior to the adoption of the resolutions quoted

above, that is, on a segregated basis. This is, of course,

subject to the possibility that a particular child may apply

to a particular school and if his application is granted,

or if on administrative appeal or by court action it is

held that the application should have been granted, that

particular child will be “ desegregated” ; but the traditional,

longstanding racial policy will continue to be applied to the

county at large.

The other aspect of the facts to which the court’s at

tention should be directed is that the proposed amended

and supplemental complaint alleged, and the special ap

pearance admitted for purposes of said special appearance,

that the policy of the State of North Carolina is one of

racial segregation in education, that the purpose of the

Pearsall Plan statutes is to continue segregation of the

races in public education and that the defendant county

school board in maintaining racial segregation was acting

pursuant to the authority and directives of the State Board

of Education and the State Superintendent of Public In

struction. Consonant with this role of the State is the

actual appearance in this case of the State Advisory Com

mittee on Education. It may be, of course, that on a full

trial such allegations might be disproved, but in this posture

of the case they stand as admitted.

Argument

1. The court below rested its decision to dismiss the

complaint for failure to state a claim upon which relief

could be granted on the Carson cases: Carson v. Board of

Education of McDowell County, 277 F. 2d 789 (4th Cir.,

1955) and Carson v. Warlich, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir., 19o6),

8

cert, denied 353 U. S. 910 (1957). But the Carson opinions

were written in contemplation of a different situation.

There, appellants sought admission to a particular school;

they had not employed the Pupil Assignment Plan for the

purpose of obtaining admission to that school, although the

Pupil Assignment Plan offered such an opportunity. The

Pupil Assignment Plan is replete with references to the

fact that it is designed to secure admission to particular

schools:

Sec. 115-178. “ Hearing before board upon denial of

application for enrollment.—The parent or guardian of

any child, or the person standing in loco parentis to

any child, who shall apply to the appropriate public

school official for the enrollment of any such child in

or the admission of such child to any public school

within the county or city administrative unit in which

such child resides, and whose application for such

enrollment or admission shall be denied, may, pursuant

to rules and regulations established by the county or

city board of education apply to such board for en

rollment in or admission to such school, and shall be

entitled to a prompt and fair hearing by such board in

accordance with the rules and regulations established

by such board. The majority of such board shall be a

quorum for the purpose of holding such hearing and

passing upon such application, and the decision of the

majority of the members present at such hearing shall

be the decision of the board. If, at such hearing, the

board shall find that such child is entitled to be en

rolled in such school, or if the board shall find that the

enrollment of such child in such school will be for the

best interests of such child, and will not interfere with

the proper administration of such school, or with the

proper instruction of the pupils there enrolled, and will

not endanger the health or safety of the children there

9

enrolled, the board shall direct that such child be en

rolled in and admitted to stick school (1955, c. 366, s.

3).” (Emphasis supplied.)

The plaintiffs in this case have not requested admission to

any particular school. They merely have requested aboli

tion of what is admittedly a policy of assignment by race.

The distinction is important and has been articulated

recently by the Fifth Circuit. In Holland v. Board of Public

Instruction of Palm Beach County, 258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir.,

1958), Judge Rives discussed the Holland case in contra

distinction to Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Educa

tion, 162 F. Supp. 372, 384 (N. D. Ala., 1958), aff’d ------

U. S . ------ , 3 L. ed. 2d 145 (1958), a suit involving an as

sault upon the constitutionality of the Alabama Pupil

Assignment Plan. Judge Rives, of course, is eminently

qualified to contrast the suits since he wrote the opinion

in each of them.

* * * for the record as a whole clearly reveals the basic

fact that, by whatever means accomplished, a com

pletely segregated public school system was and is

being maintained and enforced [in Palm Beach]. No

doubt that fact is well known to all of the citizens of

the County, and the courts simply cannot blot it out

of their sight.

# # # * #

So long as the appellant and other Negro children are

segregated in the public schools solely on the basis

of race, they and each of them (including the appel

lant) are being deprived of their rights under the

Constitution as construed by the Supreme Court. There

is no need, at this time, to consider separately the

charges of ‘gerrymandering,’ or of unconstitutionality

of the Florida Pupil Assignment Law either on its

face or in its application. It is enough to observe that

10

no means of any description can be legally employed

to deprive the appellant of his rights under the Con

stitution.2

* # # # #

The primary responsibility rests on the County Board

of Public Instruction to make ‘a prompt and reason

able start,’ and then proceed to ‘a good faith compli

ance at the earliest practicable date’ with the Constitu

tion as construed by the Supreme Court. ‘During this

period of transition,’ the district court must retain

jurisdiction to ascertain and to require good faith com

pliance.3

The Fifth Circuit is not alone in such a holding, for in

Kelly v. Board of Instruction of the City of Nashville, 159

F. Supp. 272 (M. D. Tenn., 1958), Judge Miller of the United

States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee,

held that:

* * * The Court is unable to reach the conclusion on the

facts of the instant case that the action should be dis

missed and the plaintiffs remitted to a so-called admin

istrative remedy, with the implied invitation to return

to the Federal Court if that remedy is exhausted with

out obtaining satisfactory results. This is true because

the Court is of the opinion that the administrative

remedy under the Act in question would not be an

adequate remedy. In this connection, it must be re

called that the relief sought by the complaint is not

merely to obtain assignment to particular schools but

2 258 F. 2d at 732.

3 Id. at 733 (citations omitted). And see Gibson v. Board of Public Instr.,

246 F. 2d 913, 914 (5th Cir., 1957), which in referring to the Florida law held:

“ * * * Neither that nor any other law can justify a violation of the Con

stitution of the United States by the requirement of racial segregation in

the public schools.”

11

in addition to have a system of compulsory segregation

declared unconstitutional and an injunction granted re

straining the Board of Education and other school

authorities from continuing the practice and custom

of maintaining and operating the schools of the city

upon a racially discriminatory basis.4

The Kelly case refers to the point which needs no elabora

tion. An administrative remedy must be adequate if a

plaintiff is to be barred from federal court for failure to

have exhausted it.5

It is, of course, not denied that the North Carolina admin

istrative remedy does not purport to be a means of securing

abolition of a segregation policy. The pupil assignment

plan permits governmentally enforced segregation to be

maintained. Its purport is that if any Negro child objects

to such segregation, and he or his family has the funds and

the fortitude to maintain protracted administrative and

legal proceedings, they may possibly secure for them

selves an exception to the general rule of segregation. The

general policy of keeping segregation, as executed by de

fendant board, seems hardly what the United States Su

preme Court meant by proceeding with “all deliberate

speed,” for it involves no progress, not even a scintilla of

progress whatsoever. It is by no stretch of the imagination

a “prompt start, diligently and earnestly pursued, to

eliminate racial segregation from the public schools.”

Cooper v. A aron ,------U. S .------- , 3 L. ed. 2d 5, 10 (1958).

4 159 F. Supp. at 275.

5 See, e.g., City Sank Farmers Trust Co. v. Schnader, 291 XT. S. 24, 34

(1934) (suit not premature where petitioner had, not availed himself of right

to hearing before officer already committed to action); Gully v. Interstate

Natural Gas Co., 82 F. 2d 145, 148 (5th Cir., 1936), cert, denied 298 XT. S. 688

(1936) (action not premature where it is known that board has decided on

course of action) ; cf. United States Alkali Export Assoc, v. United States,

325 TJ. S. 196 (1945) (board without power).

12

It hardly meets with the holding of the Court in Cooper v.

Aaron, that “ state authorities [are] thus duty bound to

devote every effort toward initiating desegregation and

bringing about the elimination of racial discrimination in

the public school system.” Id. at 11.

Because the concept of the pupil assignment plan has

not been held unconstitutional, see Shuttlesworth v. Bir

mingham Board of Education, supra, plaintiffs do not

contend that at some time, they or indeed any child, white

or colored, may not be required to have recourse to such an

administrative remedy. But this time would arise after a

segregation policy had been abolished, not while it still

exists. A pupil assignment plan administered in conjunc

tion with a segregation policy is merely an ingenious mode

of perpetuating segregation and plaintiffs should not be

compelled to employ it under such circumstances. Such a

combination—pupil assignment cum segregation policy—

governs the educational system by a grandfather clause.

See Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915). For the

formerly avowed policy of segregation merely imports the

practice of the past into the present by keeping the status

quo under another name. It places the burden of com

pliance on the individual children, whereas the Fourteenth

Amendment is addressed to the State.

The Court below cites Judge Parker’s opinion in Briggs

v. Elliott, that oft quoted passage which states that the

Supreme Court

* * * has not decided that the states must mix persons

of different races in the schools or must require them

to attend schools or must deprive them of the right of

choosing the schools they attend. What it has decided,

and all that it has decided, is that a state may not

deny to any person on account of race the right to

attend any school that it maintains. This, under the

13

decision of the Supreme Court, the state may not do

directly or indirectly; but if the schools which it main

tains are open to children of all races, no violation of

the Constitution is involved even though the children

of different races voluntarily attend different schools,

as they attend different churches.6

But Judge Parker certainly did not hold and indeed did not

mean to imply that a county could maintain a policy of

segregation, which Montgomery county admits it main

tains, if at the same time it offers the dubious opportunity

to individually isolated children to make application for

admission to particular white schools. The constitutional

right is the right to go to school in a system in which there

are no racial distinctions, not the right of an individual,

lonely Negro child to know that if he separately applies

and ultimately overcomes the hurdles he will be permitted

to enjoy desegregation in splendid isolation.

Plaintiffs would not presume to suggest the method by

which such desegregation can be accomplished. The litera

ture is replete with instances of how to establish non-

discriminatory school assignment. See, e.g., Shoemaker

(ed.), With All Deliberate Speed (1957) passim; Williams

and Byan, Schools in Transition (1954) passim; Clark,

“ Desegregation: An Appraisal of the Evidence,” 9 Journal

of Social Issues (1953) passim. But plaintiffs do urge that

the defendants may not, on one hand, maintain segregation

while, on the other, offer in support of its legality the right

to seek individual exceptions contrary, of course, to all the

pressures, legal and otherwise, that may be mustered by

against lone objectors.

2. The next aspect of this case involves the question of

whether the motion to add the State Board of Education

6 132 F. Supp. 776, 777 (E. D. -S. C., 1955).

14

and the State Board of Public Instruction as parties should

have been denied. For the reasons upon which the denial

was based the court referred to its opinion in Jeffers v.

Whitley, 165 F. Supp. 951 (M'. D. N. C., 1958). The basis

of this aspect of the Jeffers decision is articulated in the

following passage:

It is concluded that the state officials have no control

or authority whatever over the enrollment and assign

ment of pupils in the public schools of North Carolina,

and that the plaintiffs, if they prevail in this action,

are entitled to obtain complete relief against the county

officials, and that this action should be dismissed

against the state officials.7

But the supplemental complaint in this action has alleged

certain propositions of fact which, on the motion to dis

miss, have to be accepted as well pleaded. This is utterly

fundamental. The complaint alleged:

a) Defendant J. S. Edwards is Superintendent of Schools

for Montgomery County. Defendants E. R. Wallace, D. C.

Ewing, Harold A. Scott, James R. Burke and James Ingram

constitute the Montgomery County Board of Education.

Said Board of Education maintains and generally super

vises certain schools in said county for the education of

white children exclusively and other schools in said County

for the education of Negro children exclusively; that in the

performance of these acts, the said defendants are acting

pursuant to the direction and authority contained in State

Constitution provisions, State statutes, State administra

tive orders and legislative policy and as such are officers

of the State of North Carolina enforcing and executing

State statutes and policy. (Emphasis supplied.)

7 165 F. Supp. at 957.

15

That said Board refused to desegregate said schools

within its jurisdiction; that plaintiffs are informed and

believe and upon said information and belief allege that the

action of said Board in refusing to desegregate the schools

within its jurisdiction was done pursuant to orders, resolu

tions or directives of the State Board of Education and

the Superintendent of Public Instruction (emphasis sup

plied) (App. 41a-42a).

If this is true, as it is at least for purposes of this case,

the matter cannot be dismissed by simply pointing to the

theoretically broad powers entrusted to local boards free

of formal state requirements that there be segregation. The

state board of education unquestionably is exceedingly

powerful. This fact is plainly evidenced by the following

statutory provisions.

1. The administrative unit of the public school system

is approved by the State Board of Education. G. S.

115-4.

2. The State Board of Education has control of all

matters relating to the supervision and administra

tion of the fiscal affairs of the public schools.

3. The Board has the authority to appoint and equalize

over the state, all state school funds.

4. It has the power to invest in interest bearing securi

ties.

5. It has the power to accept federal funds and aid.

6. It has the power to purchase at mortgage sales.

7. It has the power in its discretion to alter the bound

aries of any city administrative unit or establish

additional administrative units.

8. It has the further duty to certify and regulate the

grade and salary of teachers, and other school bene

fits, and to adopt and supply text books.

16

9. It lias the power to adopt a standard course of study

upon recommendation of the state superintendent

of public instruction, and to formulate rules and

regulations for the enforcement of the compulsory

attendance law.

10. It further has the power to manage and operate a

system of insurance on public school property. (See

Cl. S. 115-11 for source of above numbered powers.)

11. It should further be noted that by authority of G. S.

115-283, state board of education has the general

supervision and administration of the educative ex

pense grants provided for under G. S. 115-274.

Moreover, we need not rely on the pleadings alone to

learn that the State Board and local boards have worked

in concert in opposition to desegregation. The July 23,

1956 Report of the North Carolina Advisory Committee

on Education states:

Immediately following publication of the April 5

report, the Committee and its staff, assisted by per

sonnel from the Governor’s Office, the Attorney Gen

eral’s Office and the Office of the Superintendent of

Public Instruction undertook to prepare rules and

regulations to be recommended to local school boards

for the implementation and the administration of the

1955 Assignment Law. This task consumed several

weeks, and during this time, extended conferences were

held with representatives from the Superintendents

Division of the North Carolina Education Association

and with members of the Policy Board of the North

Carolina School Boards Association. These repre

sentatives furnished a great deal of help to the Com

mittee and those working with it.

17

As soon as drafts of rules and regulations had been

prepared to the satisfaction of all those mentioned

above, conferences were held throughout the State with

school superintendents, school board attorneys, and

members of local school boards for the purpose of

explaining the provisions of the rules and regulations

and pointing out how they best could be used. These

conferences were, in the opinion of the Committee,

highly successful and most of the local school boards

in North Carolina, immediately thereafter, adopted

necessary rules and regulations in connection with the

1955 Assignment Act.8

Indeed, in this very case, the record reveals that the State

Advisory Committee on Education appeared at its own

request with full rights to participate as a party.

If a state board with such power as this one engaged in

concerted action with a local board to thwart desegregation

it should be held accountable. In this status of the case

that is the fact, and the legal result should follow.

CONCLUSION

Appellants respectfully submit that they should not be

required to engage in an exercise in administrative futility

and petition for admission to particular schools while ap

pellees maintain a policy of segregation. Appellants sub

mit further that the well pleaded facts described a concert

of action between state and local authorities and that

although the state may have no formal power to require

segregation the dominant position of the state as evidenced

by other statutory provisions insures that its directives

will not be flouted by local boards.

8 At 2-3.

18

Kespectfully submitted,

J . K e n n e t h L ee

P. 0. Box 645

Greensboro, North Carolina

CONRAD 0 . PEAKSON

203% E, Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Wherefore it is respectfully submitted that the deci

sion below dismissing the complaint and denying mo

tion to add parties should be reversed.

A P P E N D I X

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

M id d l e D is t r ic t of N o r t h C a r o l in a

G r e e n sb o r o D iv is io n

I n R e : H e l e n C o v in g t o n , E l s ie H o r n e , E t h e l I n g r a m ,

R o o se v e l t W i l l i a m s , G eo r g e S i m m o n s , M a u d e S m i t h ,

F l o r a K . S i m m o n s , J e n n ie N ic h l s o n , P e r c y T h o m a s ,

N e l l ie S m i t h e r m a n , J e ss ie M a r s h a l l , J a m e s M c A u l e y

and E. W. S t r e a t e r , et al.

Petition

Helen Covington and all other plaintiffs herein named

similarly situated and affected, in the above entitled ac

tion showeth to the court:

I

That Helen Covington and all other petitioners herein

similarly situated are citizens of the United States of

America and residents of Montgomery County, North

Carolina.

II

That Helen Covington and all other petitioners herein

named, similarly situated, and their minor children and/or

wards are desirous of instituting and prosecuting an action

against the officials charged with administering, operating

and effectuating the public school system in and for the

County of Montgomery for the purpose of enjoining the

said officials from denying these plaintiffs and other simi

larly situated admission to the public schools of Mont

gomery County on a non-segregated basis contrary to the

Constitution of the United States and the laws enacted

2a

Petition

pursuant thereto; that said minor children hereinafter

named, have not the capacity in their own right and name

to institute and prosecute the said proposed action, how

ever, that the petitioner Helen Covington, is the mother of

Cornett Covington, Jeanette Covington, Silvesta Coving

ton, Betty J. Stearns, Helen Covington, Lillie B, Stearns,

Woodrow Stearns and Henry Stearns.

That Elsie Horne is the mother of Elvon Horne and

Elsie May Horne;

That Ethel Ingram is the mother of Doris Ingram;

That Roosevelt Williams is the father of Billie J. W il

liams, Doris Williams, Annie Williams and Carlie Wil

liams ;

That George Simmons is the grandfather of Rose Marie

Laughton and Patricia Ann Laughton;

That Maude Smith is the mother of Prank Smith, Charles

Smith, and Ruth Smith;

That Flora K. Simmons is the mother of Anne Simmons;

That Jennie Nichlson is the mother of Brunder Sue

Nichlson, Linda Lou Nichlson and Oscar Nichlson;

That Percy Thomas is the father of John Lee Thomas,

Loyie Thomas, David Thomas, Sarah Thomas and Roose

velt Thomas;

That Nellie Smitherman is the mother of Lucille Smither-

man, Carrie Mae Smitherman, Elvena Smitherman, Alonzo

Smitherman and Ida Smitherman;

That Jessie Marshall is the mother of Dianne Marshall,

Evelyn Marshall and Betty Marshall;

That James McAuley is the father of James McAuley,

Jr., Vivian McAuley and Gloria McAuley;

That E. W. Streater is the father of Carolyn B. Streater,

Carrie Lee Streater, Eugene Streater, Betty J. Streater,

and Veralene Streater.

3a

Petition

W h e r e f o r e , the undersigned, for and on behalf of said

minors, pray the Court that an Order Issue appointing

each of them, respectively as a fit and proper person, as

next friend for his or her minor child, children, or ward

for the purpose of bringing in their behalf an action as

above set out.

Respectfully submitted this 20 day of July, 1955.

/ s / H e l e n C o v in g t o n

/ s / E l s ie H o r n e

/ s / E t h e l I n g r a m

/ s / R o o se v e l t W il l ia m s

/ s / G eorge S im m o n s

/ s / M a u d e S m i t h

/ s / F l o r a K. S im m o n s

/ s / J e n n ie N ic h l s o n

/ s / P e r c y T h o m a s

/ s/ N e l l ie S m i t h e r m a n

/ s / J e ssie M a r s h a l l

/ s / J a m e s M c A u l e y

/ s / M r . E. W. S t r e a t e r

Subscribed and sworn to before me this 20 day of July,

1955.

N o t a r y P u b l i c : / s / J a m e s H. B l u e

My commission expires: June 13, 1957.

4a

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F or t h e M id d l e D is t r ic t of N o r t h C a r o l in a

R o c k in g h a m D iv is io n

Civil Action No. 323

Complaint

I n R e : H e l e n C o v in g t o n , personally and as mother and

next friend of Cornett Covington, Jeanette Covington,

Silvesta Covington, Betty J. Stearns, Helen Covington,

Lillie B. Stearns, Woodrow Stearns and Henry Stearns,

minors; E l s ie H o r n e , personally and as mother and

next friend of Elvon Horne and Elsie May Horne,

minors; E t h e l I n g r a m , personally and as mother and

next friend of Doris Ingram, minor; R o o se v e l t W i l

l ia m s personally and as father and next friend of Billie

J. Williams, Doris Williams, Annie Williams and Carlie

Williams, minors; G eor g e S i m m o n s , personally and as

grandfather and next friend of Rose Marie Laughton

and Patricia Ann Laughton, minors; M a u d e S m i t h ,

personally and as next friend and mother of Frank

Smith, Charles Smith and Ruth Smith, minors; F l o r a

K. S im m o n s , personally and as mother and next friend

of Anne Simmons, minor; J e n n ie N i c h l s o n , personally

and as mother and next friend of Brunder Sue Nichlson,

Linda Lou Nichlson and Oscar Nichlson, minors; P e r c y

T h o m a s , personally and as father and next friend of

John Lee Thomas, Loyie Thomas, David Thomas, Sarah

Thomas and Roose Thomas, minors; N e l l ie S m i t h e r -

m a n , personally and as mother and next friend of Lucille

Smitherman, Carrie Mae Smitherman, Elvena Smither-

man, Alonzo Smitherman and Ida Smitherman, minors;

5a

Complaint

J e ss ie M a r s h a l l , personally and as mother and next

friend of Dianne Marshall, Evelyn Marshall and Betty

Marshall, minors; J a m e s M c A u l e y , personally and as

father and next friend of James McAuley, Jr., Vivian

McAuley and Gloria McAuley, minors; E. W. S t r e a t e r ,

personally and as father and next friend of Carolyn B.

Streater, Carrie Lee Streater, Eugene Streater, Betty

J. Streater, and Veralene Streater, minors,

Plaintiffs,

—vs.-

J . S. E d w a r d s , Supt. of Schools of Montgomery County,

N. C., E. B. W a l l a c e , D. C. E w i n g , H a r o l d A. S c o t t ,

J a m e s B. B itrt and J a m e s I n g r a m , members of the

Montgomery County Board of Education,

Defendants.

Plaintiffs on behalf of themselves and for the benefit of

and on behalf of all other citizens or residents of Mont

gomery County who may be similarly situated allege:

I

(a) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, section 1331. This action

arises under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitu

tion of the United States, section 1, and Title 8, United

States Code, section 41. The matter in controversy exceeds,

exclusive of interest and costs, the sum or value of Three

Thousand ($3,000.) Dollars.

(b) The jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, section 1343. This action is

6a

authorized by Title 8, United States Code, section 43 to he

commenced by any citizen of the United States or other

person within the jurisdiction thereof to redress the depri

vation, under color of a state law, statute, ordinance, regu

lation, custom or usage, of rights, privileges and im

munities secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the

Constitution of the United States, section 1, and by Title 8,

United States Code, section 41 providing for the equal

rights of citizens and of all persons within the jurisdiction

of the United States,

(c) The jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, section 2281. This is an action

for an interlocutory and permanent injunction restraining,

upon the ground of unconstitutionality, the enforcement of

provisions of the Constitution, administrative order of the

Montgomery County board of Education, and customs,

practices and usages requiring segregation in education

in Montgomery County of the State of North Carolina by

restraining defendants from enforcing such Constitutional

provisions, administrative order, customs, practices and

usages.

II

Plaintiffs bring this action pursuant to Rule 23 (a) (3) of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for themselves and on

behalf of all other Negroes similarly situated, whose num

bers make it impracticable to bring them all before the

court; they seek common relief based upon common ques

tions of law and fact.

Complaint

I l l

Plaintiffs are Negroes, citizens of the United States and

the State of North Carolina. They are residents of Mont

7a

gomery county in said state. Their children or wards all

satisfy all requirements for admission to the schools of

Montgomery county. Adult plaintiffs, not applicants, are

parents or guardians of infant plaintiffs, applicants.

IV

Defendant J. S. Edwards is Superintendent of Schools of

Montgomery County. Defendants E. R. Wallace, D. C.

Ewing, Harold A. Scott, James R. Burt„and James Ingram

constitute the county board of education. Said board main

tains and generally supervises certain schools in said

County for the education of white children exclusively and

other schools in said County for the education of Negro

children exclusively.

Complaint

V

On September 7, 1954 plaintiffs petitioned the Board of

Education of Montgomery county to abolish segregation in

the schools in their district.

VI

Said board refused to desegregate the schools within its

jurisdiction.

VII

The North Carolina constitutional provision involved is:

Article IX, Section 2, which provides

“ The General Assembly, at its first session under this Con

stitution, shall provide by taxation and otherwise for a gen

eral and uniform system of public schools, wherein tuition

shall be free of charge to all children of the state between

the ages of six and twenty-one years and children of the

8a

white race and the children of the colored race shall be

taught in separate public schools, but there shall be no dis

crimination in favor of, or to the prejudice of either race.

V III

This North Carolina Constitutional provision and the cus

toms, practices and usages of the Montgomery County

school officials as applied to these plaintiffs by these de

fendants deprive plaintiffs of equal protection of the laws

in violation of the 14th Amendment of the Constitution of

the United States.

Complaint

IX

Plaintiffs and those similarly situated suffer and are

threatened with irreparable injury by the acts herein com

plained of. They have no plain, adequate or complete

remedy to redress these wrongs other than this suit for an

injunction. Any other remedy would be attended by such

uncertainties and delays as to deny substantial relief, would

involve multiplicity of suits, cause further irreparable in

jury and occasion damage, vexation and inconvenience, not

only to the plaintiffs and those similarly situated, but to

defendants as governmental agencies.

W h e r e f o r e P l a in -t if f s respectfully pray that:

(1) The Court convene a Three-Judge Court as required

by Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2281 and 2284.

(2) The Court advance this cause on the docket and order

a speedy hearing of the application for interlocutory injunc

tion and the application for permanent injunction according

to law, and that upon such hearings:

The Court enter interlocutory and permanent judgments

declaring that Article IX Section 2 of the North Carolina

9a

Constitution, and any customs, practices and usages pur

suant to which plaintiffs are segregated in their schooling

because of race, violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution.

(3) The Court issue interlocutory and permanent injunc

tions ordering defendants to promptly present a plan of

desegregation to this Court which will expeditiously de

segregate the schools in Montgomery County and forever

restraining and enjoining defendants and each of them from

thereafter requiring these plaintiffs and all other Negroes

of public school age to attend or not to attend public

schools in Montgomery county because of race.

(4) The Court allow plaintiffs their costs and such other

relief as may appear to the Court to be just.

This the 29th day of July, 1955.

/ s / C. 0. P e a r s o n

2031/2 E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, N. C.

Attorney for the Plaintiffs

/ s / J. K e n n e t h L ee

P. 0. Box 645

Greensboro, N. C.

Attorney for the Plaintiffs

/ s / G eo r g e A. L a w s o n

914 Gorrell St.

Gr’boro, N. C.

Attorney for the Plaintiffs

/&/ M a j o r S. H ig h

914 Gorrell Street

Greensboro, N. C.

Attorney for the Plaintiffs

(Duly verified.)

Complaint

10a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

M id d l e D is t r ic t op N o r t h C a r o l in a

G r e e n s b o r o D iv is io n

Amendment to Complaint

[ s a m e t i t l e ]

The plaintiffs, by leave of Court first had and obtained,

amend their complaint heretofore filed in this action as fol

lows:

Paragraph VIII of said complaint which now reads:

“ This North Carolina Constitutional provision and cus

toms practices and usages of the Montgomery County

School officials as applied to these plaintiffs by these

defendants deprive plaintiffs of equal protection of the

laws in violation of the 14th amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States.”

Is hereby amended to read:

“ This North Carolina Constitutional provision in so far

as it requires children of the white race and the children

of the colored race shall be taught in separate public

schools and the customs, practices and usages of the

Montgomery County School officials as applied to these

plaintiffs by these defendants deprive plaintiffs of equal

protection of the laws in violation of the 14th Amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States.”

Paragraph 2, subparagraph 2 of the prayer for relief

which now reads:

11a

“ The Court enter interlocutory and permanent judg

ment declaring that Article IX section 2 of the North

Carolina Constitution, and any customs, practices and

usages pursuant to which plaintiffs are segregated in

their schooling because of race, violate the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.”

Is hereby amended to read:

“ The Court enter interlocutory and permanent judg

ment declaring that Article IX Section 2 of the North

Carolina Constitution in so far as it requires children

of the white race and the children of the colored race

shall be taught in separate public schools, and any cus

toms, practices and usages pursuant to which plaintiffs

are segregated in their schooling because of race,

violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.”

And except as hereby amended plaintiffs adopt and ratify

their original Complaint as if herein set out.

This 12 day of August, 1955.

Amendment to Complaint

/ s / J. K enneth Lee

Attorney for the Plaintiffs

12a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

M iddle D isteict of N orth Carolina

R ockin gham D ivision

Civil Action No. 323

Answer

[ same title ]

The defendants answering the complaint of the plaintiffs,

allege and say:

(1) (a) It is denied that this canse is one for the juris

diction of this court under Title 28, United States Code,

Section 1331. It is denied that there is involved in this cause

the constitutionality of any provisions of a State Constitu

tion or Statute, or the acts of any person or body, depriving

or tending to deprive any of the plaintiffs of any right under

the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States. It is denied that the matter in controversy

exceeds, exclusive of interest and costs, the sum or value

of Three Thousand Dollars ($3,000.00).

(b) It is denied that there is presented a question for

the jurisdiction of this court under Title 28, United States

Code, Section 1343. It is denied that the plaintiffs, or any

one of them, have been deprived of any right secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United

States, Section One, or by Title 28, United States Code,

Section 1343.

(c) It is denied that this cause presents a matter within

the jurisdiction of this court under Title 28, United States

Code, Section 2281. It is denied that there is, or can be,

involved in this cause the question of the enforcement or

13a

operation of any provisions of the Constitution of North

Carolina, or the enforcement or operation of any adminis

trative order of the Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, or any custom, practice or usage of said Board, in

violation of any of the rights of any plaintiff herein.

(2) It is denied that this action is, or can be a class action

brought on behalf of others situated similarly to plaintiffs.

It is denied that this is even an action on behalf of plaintiffs.

Also, as hereinafter alleged more particularly, on informa

tion and belief, it is alleged that this action is a collusive

action brought for purposes other than protection of plain

tiffs.

(3) It is admitted that the plaintiffs are negroes, citizens

of the United States, and of the State of North Carolina,

and are residents of Montgomery County. The defendants

do not have sufficient information to form a belief as to the

remaining allegations of paragraph three and, therefore,

deny the same.

(4) It is admitted that defendant, J. S. Edwards, is

Superintendent of Schools of Montgomery County, and that

defendants, E. K. Wallace, I). C. Ewing, James A. Burt,

Harold A. Scott, James Ingram, are members, and the only

members, of the Board of Education of Montgomery

County. It is admitted that the Board of Education of

Montgomery County generally supervises the public schools

in Montgomery County. Except as herein admitted, the

allegations of paragraph four are denied.

(5) It is admitted that on September 7, 1954, there was

presented to the Board of Education of Montgomery

County a written petition bearing the purported signatures

of twenty-seven (27) persons. Among those purported sig

natures, there were the names of the following who are also

Answer

14a

plaintiffs in this action: Flora K. Simmons, George Sim

mons and Percy Thomas. The name of no other plaintiff in

this action appears on that petition. Attached to this An

swer as Exhibit “A ” is a copy of said petition. Except as

herein admitted, the allegations of paragraph five are

denied.

(6) The allegations of paragraph six are denied. At

the time of the filing of the petition by the plaintiffs the

Board of Education of Montgomery had no authority and

was powerless to take any action on said petition under the

Statutes of North Carolina then in full force and effect.

Immediately following the presentation of the petition

referred to in paragraph five of this Answer, the Mont

gomery County Board of Education took action which was

evidenced by a resolution adopted by that Board. That

resolution reads as follows:

“Resolution Relating to Petition Filed by ,J. Kenneth Lee

and George A. Lawson, Attorneys on Behalf of Loyie

E. Thomas et al., Petitioners requesting that all schools

in Montgomery County be immediately desegregated in

accordance with the Supreme Court’s decision.

“ On motion of J. E. Maness seconded by H. A. Scott

the Board unanimously adopted the following resolu

tion:

“ W hereas, The State Board of Education on June 3,

1954, adopted a resolution as follows:

“ ‘The Board is aware of the manifold problems facing

the public schools of North Carolina by reason of the

recent decision of the Supreme Court of the United

States. The Court has ruled in the actions pending

before it that segregation of pupils on the basis of

race is unconstitutional. The Court has adjudicated

Answer

15a

a principle, but not the procedures through which

the principle shall be implemented and effectuated.

The Court has called for future hearing and argument

at the October Term, 1954, before issuing a final de

cree directing the course of action to be followed.

“ ‘In view of this and the necessity to make allotment

of teachers and other arrangements to operate the

public schools of the State for the school term 1954-55,

the Board deems it for the best interest of public

education to await the final decree of the Court and in

the meantime operate the public schools of North

Carolina now constituted.

“ ‘At the request of the Governor, the State Board, in

co-operation with the State Superintendent of Public

Instructions and others, will continue to study the

problem and work toward the best possible solution.

The Board appeals to every citizen in North Carolina

to remain calm and reasonable during the considera

tion of this problem.’

“A nd w hereas , The Board of Education of Montgomery

County is in accord with the aforesaid resolution of

The State Board of Education, and is of the opinion

that the public schools of Montgomery County should

be operated according to the constitution and laws of

the State of North Carolina, under the direction of The

State Board of Education, and in accord with the rules

and regulations promulgated by said Board for such

purposes.

“ Now, therefore, be it resolved that the petition filed

by attorneys on behalf of Loyie E. Thomas et al. for

immediate desegregation of the public schools of Mont

gomery County be and the same is hereby denied.”

Answer

16a

Following the decree of the Supreme Court of the United

States on May 31, 1955, and other decrees handed down by

the District Courts pursuant thereto in Civil Action No.

2657 Eastern District of South Carolina, Charleston Divi

sion, on July 15, 1955, and Civil Action No. 1333 Eastern

District of Virginia, Richmond Division, on July 18, 1955,

and pursuant to an enactment of the 1955 General Assembly

of North Carolina, the Board of Education of Montgomery

County adopted resolutions reading as follows on July 26,

1955:

“ On motion of Harold A. Scott seconded by James

Ingram, the following resolution was unanimously

adopted:

“ Whereas, the 1955 General Assembly of North Carolina

transferred to the local administrative units complete

authority over the enrollment and assignment of chil

dren in the public schools and the transportation of

children in school buses; and

“ Whereas, this Board may expect to be faced with many

difficult problems in the administration of School law

and expeeially (sic) with problems arising as a re

sult of the decision of the Supreme Court of the United

States dealing with segregation in public schools, and

“Whereas, this Board realizes that serious, thoughtful

and careful study of these problems is essential for

the successful operation of the public Schools of Mont

gomery County to the best and most beneficial interest

of all the citizens of the County, and especially the

school children, and

“Whereas, this Board feels that it is its duty to seek

factual information necessary to the elucidating, assess

Answer

17a

ing and solving* of these problems, and to that end that

an advisory committee be appointed for the special pur

poses of studying these problems and to make recom

mendations relative thereto to this Board:

Answer

“ Now, therefore, be it resolved:

1. Howard Dorsett 6. Howard Bennett

2. J. R. Russell 7. H. Page McAuley

3. E. R. Burt, Jr. 8. K. A. McCloud

4. Oscar Stevens 9. Ernest King, Jr.

5. Clyde Kern 10. S. H. McCall, Jr.

be and they are hereby appointed as a Committee to be

known as ‘The Montgomery County Advisory Commit

tee on Education’, to serve at the will of the Mont

gomery County Board of Education.

“2. That said Committee shall begin an immediate study

of the problems arising from the decision of the United

States Supreme Court regarding segregation as same

will affect the Public Schools of Montgomery County,

and make reports to this Board of its findings.

“3. That said Committee act as quickly and efficiently

as possible, but with due diliberation, in order that its

findings may be factually correct, and its recommenda

tions sound and legally feasible.

“ On motion of James Ingram seconded by D. C. Ewing,

the following resolution was unanimously adopted:

“Whereas, the 1955 General Assembly of North Carolina

transferred to the local Administrative units complete

authority over the enrollment and assignment of chil

dren in the public schools and the transportation of chil

dren in school buses; and

18a

“ Whereas, this Board may expect to be faced with many

difficult problems in the administration of the school

law and especially with problems arising as a result

of the decision of the Supreme Court of the United

States dealing with segregation in public schools, and

“ Whereas, due to the late adjournment of the 1955 Ses

sion of the General Assembly of North Carolina, and

the subsequent distribution of the laws relating to the

operation and administration of the public schools of

North Carolina, and the emensity of the task faced by

the Board of Education in setting up new and different

administrative systems, and the lack of time in which

to perform said tasks prior to the opening of schools

this year, this Board has not had, and will not have

sufficient time to make any complete an adequate

study of said laws, and

“Whereas, plans and procedures for operation of the

schools of Montgomery County for the next year had

already been formulated under provisions of prior laws,

and

“ Whereas, the Board has given serious and considerate

thought to the importance of these studies, the amount

of information needed and the time required to assem

ble same, and the time required for school organiza

tions, and the importance of first getting the reports

and recommendation of the Montgomery County Ad

visory Committee on Education:

“Now, therefore, be it resolved that the Public Schools

of Montgomery County operate during the 1955-56 term

with practices of enrollment and assignment of chil

dren similar to those in use during the 1954-55 school

year, and that this resolution be the authority for the

Answer

19a

County Superintendent and the various district school

principals and officials to so act.

“ Be it further resolved, that pending a complete study

of the School Law, as amended, and any and all new

laws relating to the operation of the public schools,

any parent or guardian of any child, or the person

standing in loca Parentis to any child, who desires that

said child shall be entered in any school other than the

one to which said child has been assigned, shall file

written application with the principal of the school

in which it is desired that said child be enrolled, giv

ing the name of the child and the reason, or reasons,

why the change is requested. The principal with whom

such application is filed shall act favorably thereon

if he shall find that the enrollment of such child in such

school will be for the best interest of such child, and

will not interfere with the proper administration of

such School, or with the proper instruction of the pupils

there entrolled, and will not endanger the health or

safety of the children there enrolled, considering the

needs and welfare of the child seeking administration,

the welfare and best interest of all other children in

the school, availability of facilities, including trans

portation, fitness of facilities, including health, aptitude

of the child and curriculum adjustment of the School,

residence of the child, and all other factors considered

pertinent, relevant and material affecting either the

child or the school, otherwise the application shall be

denied. Upon the denial of any such application, by the

school principal, application for a hearing thereon be

fore this Board may be made in writing by the parent

or guardian of such child, or the person standing in

Answer

20a

loco parentis to said child, a copy of the ruling of the

principal denying admittance to accompany said ap

plication.”

In furtherance of the matters set forth in those resolu

tions, the Board of Education of Montgomery County and

its committee, appointed as is set forth in the resolution

quoted immediately above in this answer, have continued to

make a study of the problems involved in the operation of

the schools of Montgomery County to the end that the

operation of such schools may lawfully be continued and

that the schools may be preserved for all the children of the

County.

(7) It is admitted that Article 9, Section 2, of the Con

stitution of North Carolina, contains provisions as quoted

in paragraph seven of the Complaint and Amended Com

plaint. It is denied that the constitutionality of any provi

sion so quoted is involved in this cause of action.

(8) The allegations of paragraph eight are denied.

(9) The allegations of paragraph nine are denied.

F u rther A nsw er and D efense

For a further answer and defense to the matters alleged

in the plaintiffs’ complaint, these defendants allege and

say:

That the plaintiffs complain of the alleged action taken

by the defendants in the summer of 1954. Plaintiffs have

waited approximately one (1) year before asserting any

such right. This action was brought after the decision of

the Supreme Court on May 31, 1955, and plaintiffs have

not alleged that they went to or sought any relief from

the Board of Education of Montgomery County following

Answer

21a

the decision of the Supreme Court of May 31, 1955, or ap

plied to the Board of Education of Montgomery County

following the enactment of the 1955 General Assembly of

North Carolina, or that they made any effort whatever to

ascertain what the Board of Education of Montgomery

County was doing or intended to do following the decision

of the Supreme Court of the United States on May 31,1955.

This action was brought by the plaintiffs within twenty (20)

days following the announcement of the decrees of the

three-judge Federal Courts in South Carolina and Virginia,

more specifically referred to in paragraph six of this An

swer, in which the courts allowed the schools of Clarendon

and Prince Edward Counties, South Carolina and Virginia

respectively, sufficient time for compliance with the mandate

of the Supreme Court of the United States.

For a second and further defense, defendants allege that

following such court decrees as above referred to, the plain

tiffs failed and neglected to make any effort to ascertain

what the Board of Education of Montgomery County was

doing, or to make any request of the Board of Education

of Montgomery County. Plaintiffs have completely failed to

take any action to secure administrative relief or adminis

trative action since the adjournment of the 1955 General

Assembly of North Carolina, the decree of the Supreme

Court of the United States on May 31, 1955, or since the

decrees of the three-judge Federal Courts in South Carolina

and Virginia in July 1955. Plaintiffs have not been diligent

in the proper prosecution of any proper rights which they

have with relation to the schools of Montgomery County.

Plaintiffs’ conduct leads only to the conclusion that what

the plaintiffs are seeking is a suit in court rather than ad

ministrative relief. The children of Montgomery County

had been assigned by the time of the filing of this action

Answer

22a

to the schools and the Board of Education cannot make

changes quickly within the school framework which was well

known to the plaintiffs.

For a third and further answer, the defendants are in

formed and believe, and therefore on information and be

lief allege and say, that the plaintiffs are not in a position

to ask a court of equity to exercise its equity powers on be

half of plaintiffs for that the plaintiffs are not in this ac

tion seeking the proper protection of any rights of any

individual plaintiff. This action is not a bona fide effort to

obtain the relief sought in the complaint. The purposes of

this action are the stirring up of trouble, the disruption of

the operation of the schools, and the advancement of the

interests of others than the plaintiffs who have no legal

interest in the subject matter of this controversy and no

right to the relief sought herein. These defendants allege

that the institution of this action, at the time and under

the circumstances when it was instituted, threatens an abuse

of the courts and of the processes of the courts and is con

trary to public policy.

W herefore, hav ing fu lly answ ered the said com plaint,

the defendants p ra y that the action be d ism issed, w ith p r e j

udice, and that the costs be taxed against the p la intiffs.

The defendants respectfully request the court for a jury

trial.

/ s / G arland S. Garbiss,

Troy, N. C.

Attorney for Defendants

Answer

(Duly verified.)

23a

EXHIBIT “A ”

P etition

N orth Carolina )

M ontgomery County )

To the Superintendent )

and Board of School Trustees )

of the Montgomery County, )

North Carolina, Public Schools )

The undersigned petitioners respectfully show unto the

Superintendent and School Board:

I.

That they are parents of children of school age who are

entitled to attend and who are attending the public elemen

tary and secondary schools under your jurisdiction.

II.

That pursuant to state law, five racially segregated public

schools are being maintained and operated by you for chil

dren of Negro parentage.

III.

That on the 17th day of May, 1954, the United States

Supreme Court ruled that the maintenance of racially

segregated public schools is a violation of the Constitution

of the United States and that “ . . . in the field of public

education the doctrine of separate by equal has no place.

Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

24a

IV.

That in spite of the above quoted decision, the Negro

children under your jurisdiction are still denied the right

to attend the schools of Montgomery County on an unsegre

gated basis for the current school term, and are required

to attend one of the aforesaid five schools maintained by

you solely for Negro students; That under the constitutional

principles enunciated by the Supreme Court on May 17th,

children of public school age attending and entitled to at

tend public schools cannot be denied admission to any school

or be required to attend any school solely because of race or

color.

V.

That the uncontinued maintenance of segregated schools

by you as above set out is a denial of the right guaranteed

the Negro children of Montgomery County by the Federal

Constitution, and that the nature and extent of this action

is such that your petitioners and their children will suffer

irreparable harm unless immediate action is taken by you

to rectify the present situation.

W h e r e e o b e , your petitioners pray

(1) That all schools under your jurisdiction be immediately

desegregated in accordance with the Supreme Court’s de

cision.

(2) That by reason of the urgency of the situation and the

nature of the issues involved, decisive and conclusive action

be taken on this petition at the September 7, 1954, meet

ing of the Board of School Trustees.

Respectfully submitted this 7 day of September, 1954.

Exhibit “A”

25a

E xhibit “ A ”

/ s / Loyie E. Thomas ,

s / Percy Thomas

s / Ada Butler

s / Hattie Stanback .

s / Erie Green .

s / Sara Butler ,

s / James S. Smith ,

s / Jessie M. Marshall ,

s / Henry Baldwin ,

s / Eushie McAuley ,

s / Trumella L. Diggs ,

s / A. D. Freeman ,

s / J. W. French

s / Oscar Thomas ,

s / Gladys K. Thomas ,

s / Sidney Thomas (his) (x),

s / E. D. Gainney ,

s / Teccie M. Hammond ,

s / Jess Cagle ,

s / Irene Martin ,

s / Daisey Harris ,

s / James Butler ,

s / N. W. Towery ,

s / Flora Kelly Simmons ,

Petitioner

U

U

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

66

66

66

66

66

66

66

66

66

6 6

66

66

66

26a

/ s / T. H. Simmons , “

s / Ernest Simmons , “

s / George Simmons, Pres. , “

Peabody High School P.T.A.

s/ J. K enneth Lee

J. Kenneth Lee

Attorney for Petitioners

s / George A. Lawson

George A. Lawson,

Attorney for Petitioners

Exhibit “ A ”

27a

Petition

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

M iddle D istrict of N orth Carolina

R ockingham D ivision

Civil Action #323

[ same title ]

William W. Taylor, Jr., and Thomas F. Ellis, counsel

for the North Carolina Advisory Committee on Education,

respectfully show to the Court that, because of the vitally