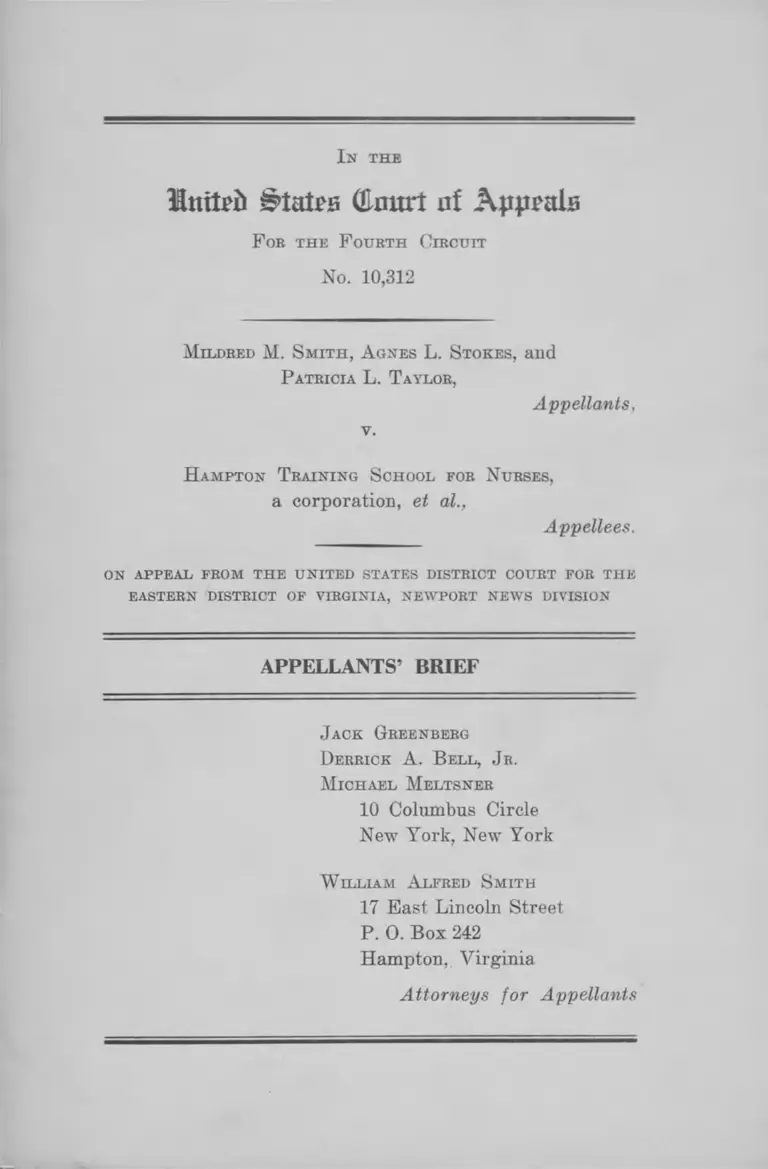

Smith v Hampton Training School for Nurses Appellants Brief

Public Court Documents

May 25, 1964

39 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Hampton Training School for Nurses Appellants Brief, 1964. b0c7139d-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f1f57eee-ec3f-445f-9fe5-83adebd26bd3/smith-v-hampton-training-school-for-nurses-appellants-brief. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

In the

U n ite d S ta te s (U n u rt n f A p p e a ls

F ob the F ourth Circuit

No. 10,312

M ildred M. S m ith , A gnes L. S tokes, and

Patricia L. Taylor,

Appellants,

v.

H ampton T raining S chool for Nurses,

a corporation, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM TH E UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR TH E

EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, NEW PORT NEW S DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Jack Greenberg

Derrick A. B ell, Jr.

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

W illiam A lfred S mith

17 East Lincoln Street

P. 0. Box 242

Hampton, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 1

Questions Presented .......................................................... 4

Statement of Facts ........................................................... 4

A rgument—

I—The Court below erred in dismissing the complaint

on the ground that Negro nurses are without con

stitutional rights if discharged solely on account

of race by a Hill-Burton Hospital prior to the

date of this Court’s decision in Simkins v. Moses

H. Cone Memorial Hospital (November 1, 1963) .. 10

A. The Constitutional Rights of the Nurses Ex

isted Prior to November 1, 1963 ...................... 11

B. Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital

Applied, Rather Than Reversed, Prior Law .... 12

C. Dixie Hospital Was Specifically Obliged Not to

Discriminate on the Basis of Race as Early as

1956 ......................................................................... 16

D. Even if Simkins Reversed Prior Law it Would

Apply to the Nurses ............................................ 18

II—Negro nurses, racially discharged from a Hill-Bur

ton Hospital, prohibited from discrimination by

the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, are en

titled to injunctive relief ordering reinstatement

with back pay ............................................................ 23

Conclusion 32

11

Admiral Corp. v. Admiral Employment Bureau, 161

F. Supp. 629 (N. D. 111. 1957) ...................................... 31

Alexander v. Hillman, 296 U. S. 222 ............................ 30,31

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F. 2d

992 (4th Cir. 1940) ......................................................... 28

Agwilines, Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, 87

F. 2d 146 (5th Cir. 1936) .............................................. 30

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ...................................... 18

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond........ 29

Bridges v. Hampton Training School for Nurses ........ 8

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ....11,18, 20, 25

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 ............................................................13,14,15,16,20,25

Caddington v. United States, 178 F. Supp. 604 (Ct.

Cl. 1959) ........................................................................... 28

Cat’s Paw Rubber Co. v. Barlo Leather & Findings Co.,

12 F. R. D. 119 (S. D. N. Y. 1951) .............................. 10

Chappell & Co. v. Palermo Cafe Co., 249 F. 2d 77

(1st Cir. 1957) ............................................................... 31

Coca Cola Co. v. Old Dominion Beverage Corp., 271 F.

600 (4th Cir. 1921) ......................................................... 31

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Comm. v. Continental

Airlines, 372 U. S. 714 .................... .....................H , 18, 25

Conley v. Gibson, 355 U. S. 41 .......................................... 27

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ............................................ 14

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U. S. 278 .... 25

Crane Co. v. Crane, 157 F. Supp. 293 (W. D. Ga. 1957) 31

Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 4 Wheat. 518 ........... 16

Daub v. United States, 292 F. 2d 895 (Ct. Cl. 1961) .... 28

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 350

IT. S. 877 ...................................................

PAGE

18

Ill

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F. 2d

150 (5th Cir. 1961) cert, denied 368 U. S. 930 ........... 29

Eaton v. Grubbs, 261 F. 2d 521 (4th Cir. 1958) ....14,15,29

Eaton v. Janies Walker Memorial Hospital, 329 F. 2d

710 (4th Cir. 1964) ....................................13,14,15, 20, 25

PAGE

Eskridge v. Washing-ton, 357 U. S. 214.......................... 22

Ettelson v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 137 F. 2d 62

(3rd Cir. 1943) cert, denied 320 U. S. 777 ................... 31

Flemming v. South Carolina Electric and Gas Co., 239

F. 2d 277 (4th Cir. 1956) ..............................................18,19

Gayle v. Browder, 350 U. S. 903 ...................................... 18

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S. 325 .............................. 22

Gilliam v. School Board of City of Hopewell ............... 29

Great Northern R. Co. v. Sunburst Oil & Refining Co.,

287 U. S. 358 ................................................................... 19

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U. S. 474 .................................. 27

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U. S. 1 2 .......................................... 22

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, 377

U. S. 218 ......................................................................... 30

Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320 (5th

Cir. 1962) ....................................................................... 13,15

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81 ................... 30

Hirsch v. Glidden Co., 79 F. Supp. 729 (S. D. N. Y.

1948) ................................................................................. 31

Jordan v. Hutcheson, 323 F. 2d 597 (4th Cir. 1963) .... 24

Khoury v. Community Memorial Hospital, Inc., 203

Va. 236, S. E. 2d 533 (1962) .....................................15,16

Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp. 174

(M. D. Tenn. 1961) 29

IV

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U. S. 618 ........................ 21,22,29

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 ............. 28

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167.......................................... 28

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643 ....................................21, 22, 28

Mosser v. Darrow, 341 U. S. 267 .................................... 19

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Assn., 347 U. S.

971 .................................................................................... 18

PAGE

N. L. R. B. v. Jones & Laughlin S. Oorp., 301 U. S.

47 .................................................................................... 27,30

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 .............................. 12

Rackley v. Orangeburg School District No. 5 (No. 8458,

E. D. S. C.) ................................................................... 29

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U. S. 232 .... 25

Service v. Dulles, 354 U. S. 365 ...................................... 26

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F.

2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963) ...................... 3, 4,10,11,12,14,15,

16,17,18,19, 20, 21,

22, 23,25, 29

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 ................................12,19

Slochower v. Board of Education, 350 U. S. 551 ........... 27

Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192.............. 27

Thomas v. United States, 289 F. 2d 948 (Ct. Cl., 1961) 27

Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship Committee of Steel

Workers, 223 F. Supp. 12 (N. D. Til. 1963), vacated

on other grounds, 332 F. 2d 243 (7th Cir. 1964) .... 27

Toreii (i v. Walkins, 367 U. S. 13S 25

Vitarelli v. Seaton, 359 U. S. 353 27

V

PAGE

Wickersham v. United States, 201 U. S. 392 ................. 27

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183 .............................. 25

Williams v. Sumter School District No. 2 (No. 1534

E. D. S. C.) ............................................................. ....... 29

Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25 ......................................21, 28

Woods v. Wright, 334 F. 2d 369 (5tli Cir. 1964) ........... 29

T able of S tatutes and R egulations

28 U. S. C. §1343 ( 3 ) ........................................................... 2

42 U. S. C. 291e(f) 1958 ed.................................... 10,16,17,18

42 U. S. C. §1981................................................................. 2

42 U. S. C. §1983 (RS §1979) ............................................2, 28

42 U. S. C. §§2000(d) .......................................................... 17

National Labor Relations Act of 1935, §10(c) ............... 30

42 CFR §53.111 ................................................................... 17

42 CFR §53.112 ..................................................... 10,16,17,18

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 12(b)(6) ........ 2

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 3 8 .................... 2,31

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 52(b) .............. 3

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 54(c) .............. 26

I n the

Mttiteii S ta te s (Hm trt at A p p e a ls

F or the F ourth Circuit

No. 10,312

M ildred M. S m ith , A gnes L. Stokes, and

Patricia L. T aylor,

Appellants,

v.

H ampton T raining S chool for N urses,

a corporation, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM TH E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR TH E

EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, NEW PORT NEW S DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case

This is a suit for an injunction ordering the Dixie

Hospital of Hampton, Virginia, to reinstate, with back

pay, three Negro nurses who were dismissed from employ

ment solely because they dined in the Hospital’s white-

employee cafeteria (4a, 11a).

The complaint was filed in the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, May 25, 1964,

along with motion for preliminary injunction alleging that

August 9, 1963 appellants, three Negro nurses employed

by the Hospital, ate lunch in the main cafeteria, reserved

for white persons only, and for this reason were summar

ily dismissed (6a-8a). Alleging that the Dixie Hospital

2

has received, and is receiving, federal funds under the Hill-

Burton Program, the nurses brought this action pursuant

to 28 U. S. C. §1343(3) and 42 U. S. C. §1983 to secure

relief for deprivation of rights guaranteed by the due

process and the equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment and the due process clause of the Fifth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States and 42

U. S. C. §1981 (4a, 5a, 10a). As defendants, the complaint

named administrators of the Hospital, the corporate entity,

and officers and directors of the corporation (5a, 6a).

On June 17, 1964, the Hospital filed an answer which

admitted participation in the Hill-Burton Program and

dismissal of the nurses because by eating in the white

cafeteria they violated Hospital “ rules” , but contested that

constitutional rights of the nurses were denied (15a-18a).

Interrogatories submitted by the nurses were answered

by the Hospital July 24, 1964 (26a, 30a). On January 18,

1965, the district court held an initial pre-trial conference

and set the case for trial July 27, 1965 (35a). Also on

January 18, the Hospital demanded a jury trial for all

the triable issues pursuant to Rule 38(d) of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure (37a). Motion to strike the Hos

pital’s demand for a jury trial was filed by the nurses on

February 15, 1964.

On April 14, 1965, the Hospital filed a motion to dismiss

pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure asserting that the complaint failed to state a

claim upon which relief can be granted (40a). On July 20,

1965, the district court filed an opinion considering the

motion and, on August 20, 1965, entered an order dismiss

ing the action on the basis of the opinion (41a-48a, 54a).

The opinion is reported at 243 F. Supp. 403.

3

Treating the motion to dismiss as a motion for “ sum

mary judgment on the pleadings” , the court granted it,

“dismissing the action at the costs of the plaintiffs” on

the ground that, at the time they were discharged, the

nurses were without constitutional rights to non-racial

treatment:

. . . public policy dictates that, whatever may be the

rights of a Negro discharged from employment fol

lowing the decision in Simkins by the Court of Appeals

and the subsequent denial of certiorari, together with

the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, no rights

are created which should be accorded retrospective

effect (46a).

In addition, the court found that even if the nurses had

constitutional rights to non-racial treatment they could not

seek reinstatement, with back pay, but could only main

tain an action for damages (47a).

On August 2, 1965, subsequent to receipt of the July 20,

1965 opinion, but prior to the entry of an order, appellants

moved the court, pursuant to Rule 52(b) of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, to amend its findings of July 20,

1965, and, in light of such amendments, to reconsider its

decision (49a-53a). Exhibits and affidavits were attached

in support of the motion (54a-82a). On September 7, 1965,

the court denied the motion.1

1 In denying the August 2, 1965 motion the court stated that the

motion was one to reconsider the July 20, 1965 decision and not a

motion to amend findings pursuant to Rule 52(b) o f the Federal Rules

o f Civil Procedure and that it had entered an order granting summary

judgment (August 20, 1965) with no reference to the August 2, 1965

motion because the court had not been sent a copy o f the motion by

appellants’ counsel at the time the motion was filed with the clerk (55a,

56a). However, the court denied the motion on the merits stating:

“ Irrespective o f the affidavits and exhibits attached to the ‘Motion,’ the

fundamental principles guiding the Court’s decision are not altered” (84a,

85a).

4

Notice of appeal to this Court from the August 20, 1965

and September 7, 1965 orders of the district court was

filed September 17, 1965 (86a).

Questions Presented

1. Whether three Negro nurses may be denied employ

ment on the basis of race at a non-profit, Hill-Burton Pro

gram, hospital, subject to the restraints against racial dis

crimination of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, on

the ground that their racial discharge from employment

took place August 9, 1963 px-ior to this Court’s decision

in Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F. 2d

959 (November 1, 1963).

2. (a) Whether Negro nurses discharged on account of

race in violation of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments

are entitled to an injunction ordering reinstatement, with

back pay, or must maintain an action for damages before

a jury; (b) Whether the prayer of the nurses for back pay

from the time of the unconstitutional discharge must be

submitted to a jury.

Statement of Facts

In 1958, the Dixie Hospital, a non-profit, tax-exempt

facility and the only hospital in Hampton, Virginia, con

structed a new hospital building with the assistance of

over 1.7 million dollars received from the United States

pursuant to the Hill-Burton Act, 42 U. S. C. §§ 291 et seq.

(5a, 15a, 21a, 30a). The building housed a spacious cafe

teria, complete with glass urall overlooking a scenic view

of Chesapeake Bay and a seating capacity of approxi

mately 200 (73a). White employees, regardless of rank or

5

station, dined in the cafeteria; white visitors were per

mitted to eat there. Negro employees, however, were not

free to eat in the cafeteria (7a, 16a-18a, 32a, 42a, 73a, 74a).

At the time the new building was opened a room had

been set aside in the basement of the Hospital, across

from the kitchen, for the use of Negro employees (6a,

74a). Almost a year later, after several complaints, Negro

employees were permitted to eat in a small converted class

room situated down the hall from the main cafeteria (74a).

In order to dine in this room Negro employees had to

telephone their orders for food service to the cafeteria and

wait until the food was delivered to the room set aside

for their use. This procedure resulted in cold food and

delays which exhausted the 30 minute lunch period (74a).

Nurse Mildred Smith describes subsequent events:

“After several months of this practice, many of us signed

and prepared a petition to the director of the hospital

complaining about the eating facilities provided for Negro

personnel. A meeting was held with the director of nurses

and William C. Walton, the administrator of Dixie Hos

pital, at which time Mr. Walton said he would present

the matter to his board and give us a response within a

month. At this meeting, Mr. Walton was insulting and

indicated that we Negroes did not know when we were

well off, that we were second class citizens, and that before

coming to Virginia he had never called Negroes Mister or

Mrs. No board action on our petition was ever reported

to us.

“In May 1963 after more complaints, Negro nurses were

permitted to pass through the main cafeteria line, but

were forced to continue eating their meals in a small room

located approximately 50 feet down the hall from the

cafeteria. This room is a converted classroom and seats

6

perhaps 35 people. Because there are over 100 Negro

personnel who must eat there, the room is frequently-

crowded and persons must wait their turn for available

chairs. This, combined with the necessity of leaving the

main cafeteria and walking to the small room, necessitates

rushing our lunch which frequently causes distress and a

decrease in efficiency for the rest of the working day.

In addition, the humiliation we experience when we see

white persons, some of them maintenance personnel in

dirty working clothes, seated in the main cafeteria while

we are forced to leave because of our race, is impossible

to explain” (74a-75a).

On August 8, 1963, Mrs. Smith, nurses Taylor and Stokes

and another Negro employee ate their lunch in the main

cafeteria instead of carrying their food down the hall to

the “ Negro dining room” (7a, 75a). Thereafter, they were

reprimanded for eating in the white-only cafeteria and

cautioned not to do so again by the assistant administrator

of the Hospital, Mr. Edward Bennett (17a). He informed

them that their presence in the main cafeteria violated

Hospital “ rules” and that “ so long as they were employees

of Dixie Hospital they would have to abide by such rules”

(17a).

The following day, August 9, 1963, the three nurses,

along with two other Negro employees, again took their

food from the serving line to a table in the cafeteria in

stead of carrying it to the converted classroom set aside

for Negro use (7a, 17a, 73a, 75a). The decision to eat

lunch in the main cafeteria “resulted from a culmination

of the humiliation and inconvenience . . . and a belief that

we were both entitled to eat in the main cafeteria and that

there would be no serious objection from white persons

if we were to eat there” (75a). It “was not intended to

7

violate hospital regulations or create a disturbance, but

was the latest in a series of efforts by . . . Negro personnel

employed at Dixie Hospital to obtain equal working facili

ties” (73a). There were no disturbances and, on the second

day, many white persons welcomed the nurses and in

dicated that they were glad to see them back (75a). How

ever, later in the day nurses Smith, Taylor, and Stokes

were discharged by the Hospital (7a, 18a).

On August 26, 1963, an attorney for the nurses wrote

the administrator of the Dixie Hospital, Mr. Walton, re

questing their reinstatement and also seeking to be in

formed of any appellate procedure for reviewing their

dismissal. In a letter dated September 4, 1963, Mr. Walton

refused to reinstate the nurses and further stated that

“No procedure exists for the redress of matters of this

nature” (9a-10a).

The Hospital does not dispute that the only actions of

the nurses which led to their discharge was their eating

lunch in the white-only cafeteria (20a). There is no con

tention that the three nurses were discharged August 9,

1963 for any reason pertaining to their services as nurses,

although it is said that one nurse, Mrs. Smith, “ inciting

agitation among fellow workers concerning hospital poli

cies” (20a). However, the Hospital alleges that dismissal

of the Negroes for eating in the white cafeteria was “be

cause of insubordination and violation of the rules, regula

tions and policies of the Dixie Hospital” (18a).

The answer alleges that Mrs. Smith, who was a regis

tered nurse at the Dixie Hospital earning $280.00 per

month and whose employment by the hospital had begun

in 1955, was not a “completely satisfactory” employee be

cause she terminated her employment at various times

between the period 1955 and 1963 due to health, family

8

responsibilities, child birth and other reasons2 (18a, 19a).

There is, however, no attempt to connect these charges with

her dismissal on August 9, 1963.

Agnes L. Stokes was, at the time of her dismissal, a

licensed practical nurse at a salary of $210.00 per month.

Patricia L. Taylor was employed as a general practical

nurse also at a salary of $210.00 per month. The answer

concedes that the services of nurses Stokes and Taylor

were satisfactory, except that nurse Taylor had not ad

vanced herself to the level of a licensed practical nurse

(18a, 19a). There is no attempt to connect this charge

with her dismissal on August 9, 1963.

The record shows that Dixie Hospital maintains racially

discriminatory practices such as separate pediatrics wards

for white and Negro children and separate floors for

Negro and white patients and racial assignments of physi

cians (31a, 32a, 77a, 78a).3 The cafeteria was finally opened

to Negro employees October 2, 1963. In its answer Dixie

Hospital concedes and attempts to justify racial segrega

tion in general:

. . . certain forms of segregation are maintained in

Dixie Hospital as in other hospitals, to wit: Negro

2 In addition, the answer characterizes her as follow s:

So far as her actual physical duties were concerned, they were satis

factory and she was a competent and capable nurse. However, her

general appearance, ability to work with others, her attitude and

personality were only fair and were not up to the level expected of

a person o f her ability and she incited agitation and insubordination

among her fellow workers concerning hospital policies (19a, 20a).

3 A companion suit, Bridges v. Hampton Training School for Nurses,

a corporation, Civil Action No. 1001 pending in E. D. Va., o f which the

district court took judicial notice (43a) has as plaintiffs the three nurses

and a Negro physician, a white minor and her next friend. In that suit

plaintiffs seek injunctive relief against these and other racial policies

o f the hospital including segregation o f white patients attended by Negro

physicians.

9

patients and white patients are on separate floors, if

that be segregation; males and females are segre

gated into different wards; maternity cases are segre

gated from other types of cases; pediatrics cases are

segregated from other types of cases. The types of

segregation referred to are in general practice in

Virginia and in other states throughout the United

States and is not in violation of the equal protection

and due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment and the due process clause of the Fifth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States (20a-21a).

The hospital also alleged that funds contributed by

white persons and organizations represented by them had

been made to the hospital “with the specific understanding

that the policy of Dixie Hospital of placing white and

Negro patients on separate floors, which policy had existed

for many, many years, would be maintained and such con

tributions were conditioned upon that policy” (21a).

Dixie Hospital has received and is presently applying

for large sums from the United States under the Hill-

Burton Program for hospital construction. In 1956, the

United States approved a grant to the hospital for approx

imately $1,730,000 of a total construction cost of $3,600,000

(55a-58a); the State of Virginia provided $173,000 towards

construction of the new building (31a). It was in the

building made possible by these funds that the events of

August 9, 1963 took place. In its application for these

funds Dixie Hospital represented to the United States

“that the facility will be operated without discrimination

because of race, creed or color” (58a).

Presently pending before the United States, and awaiting

decision as to whether or not the hospital is in compliance

with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, is the hos

10

pital’s application under the Hill-Burton Act for an addi

tional grant of $585,000 for new hospital construction (15a,

68a-72a, 77a, 78a). According to the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare, as of July 13, 1965, the hospital is

not in compliance with Title VI “ particularly in the areas

of patient assignment to rooms and the use of separate ad

mission lists for Negro and white patients” (78a).

A R G U M E N T

I

The Court below erred in dismissing the complaint

on the ground that Negro nurses are without consti

tutional rights if discharged solely on account of race

by a Hill-Burton Hospital prior to the date of this

Court’s decision in Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial

Hospital (November I , 1963).

In dismissing this action, the district court treated a

motion to dismiss filed by the Hospital ten months after

answer, as a motion for summary judgment on the plead

ings and granted the motion. On review of such a deter

mination, the facts alleged by the plaintiffs are accepted,

the question here being whether, on such facts, the nurses

are entitled to relief. See Cat’s Paw Rubber Co. v. Barlo

Leather & Findings Co., and cases cited 12 F. R. D. 119, 121

(S. D. N. Y. 1951).

The district court stated the dispositive issue of law in

this case to be whether “acting under what was then deter

mined to be ‘not State action’ and proceeding under wliat

was assumed to be a valid statute [42 IT. S. C. §291e(f)]

and regulation” [42 C. F. R. §53.112] Dixie Hospital is

“ liable for back pay and . . . required to reinstate the plain

11

tiffs to their former positions” (44a). (Emphasis supplied.)

The court answered this question by holding “public policy

dictates that, whatever may be the rights of a Negro dis

charged from employment following the decision in Simkins

by the Court of Appeals and the subsequent denial of cer

tiorari, together with the passage of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, no rights are created which should be accorded

retrospective effect” (46a).

A. The Constitutional Rights of the Nurses Existed

Prior to November 1, 1963.

The idea that the nurses’ constitutional right to be free

from racially nondiscriminatory treatment in their employ

ment conditions in a governmentally supported hospital

suddenly “vested” on the date this Court decided the

Simkins case is alien to much of our constitutional juris

prudence. Their rights derive from the Fourteenth Amend

ment which became a part of our basic law in the last cen

tury. But this case need not turn on any jurisprudential

argument about whether judges “create” or “ discover” law

in interpreting the Constitution. Ever since the Fourteenth

Amendment was ratified state agencies have been on no

tice that they are forbidden to discriminate racially. Since

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, they have been

on notice that segregation was a denial of equal protection.

In April 1963, some months before the appellants were

fired, a unanimous Supreme Court pointed to its prior de

cisions and said in Colorado Anti-Discrimination Comm. v.

Continental Airlines, 372 U. S. 714, 721:

But under our more recent decisions any state or fed

eral law requiring applicants for any job to be turned

away because of their color would be invalid under the

Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment and the

12

Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment.

And in May 1963, the Court had made it crystal clear that

state compelled segregation in restaurants violated the

Constitution. Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244.

The only issue was whether the Dixie Hospital was suf

ficiently involved with government to be bound by the Con

stitution. The Dixie Hospital between 1956 and 1959 ac

cepted more than 1.9 million of the taxpayers’ dollars. Ac

tion by the Hospital thereafter premised on the theory that

it was unaccountable to standards of conduct governing the

public was surely taken at its peril. This is particularly so

where the Hospital had no basis for a claim that it acted

in reliance on a prior precedent in its favor and should be

exempt from the surprise effects of a change of law. Cf.

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649, 650, 665, 666. These con

siderations require reversal of the judgment below.

However, it is also appellants’ belief that the specific

premises relied upon below are erroneous, and, moreover,

that even were they valid, the conclusion of the district

court still would not follow, see infra, pp. 18-23.

B. Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital

Applied, Rather Than Reversed, Prior Law.

The first premise relied upon assumes that “at the time

these causes of action now asserted by the plaintiffs arose,

the state and federal law was clear and the plaintiffs had

no cause of action,” for on August 9, 1963, the Hospital was

“acting under what was then determined to be ‘not state

action’ ” (44a-47a). In short, the district court, which ex

pressed “ serious doubts” as to Simkins v. Moses H. Cone

Memorial Hospital, 323 F. 2d 959 (4th Cir. Nov. 1, 1963),

considered the decision a reversal of prior law as to the

13

scope of the state and federal action requirements of the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

The conclusion will not bear examination of the Simkins

opinion. Far from overruling previous decisions on the

scope of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, this Court

expressly relied upon and applied such decisions, especially

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715

(1961).

The Court made this clear in unequivocal language:

“Weighing the circumstances, we are of the opinion that

this case is controlled by Burton” 4 (323 F. 2d at 967).

(Emphasis supplied.) Therefore, when the district court

states that “ There is nothing in Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, [81 S. Ct. 856, 6 L. ed. 2d

45] decided in 1961, which would give rise to the belief that

the rule in Simkins was forthcoming” (46a) the court’s

conclusion collides with the holding in Simkins itself that

Simkins was “ controlled” by Burton. See also Hampton

v. City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320, 323 (5th Cir. 1962)

decided before Simkins and before August 9, 1963, the date

of the racial discharge.

The district court’s erroneous view of Burton, supra, is

further illustrated by another of this Court’s decisions,

Eaton v. James Walker Memorial Hospital, 329 F. 2d 710

(4th Cir. 1964) which found Burton and Simkins cut from

the same cloth. In that case this Court refused to apply

the rule of res judicata (asserted to arise from an earlier

Eaton decision) to a constitutional violation because of the

principles enunciated in “Burton and Simkins . . . ” (329

F. 2d at 712).

4 Burton, supra, was decided by the United States Supreme Court on

April 17, 1961, more than two years before the nurses were discharged.

The refusal o f service to Mr. Burton took place in 1958.

14

In addition to Burton, the Court in Simkins expressly

based relief on a host of decisions on the scope of Fifth and

Fourteenth Amendments handed down prior to August 9,

1963, the date on which this cause of action arose (323 F. 2d

967-69) and the Court stressed language in Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 4 (1958) that the Constitution forbids

“ state participation through any arrangement, manage

ment, funds or property,” which supports segregation.

(Emphasis in original.) These decisions demonstrate be

yond a doubt that, far from reversing prior law, Simkins

applied existing principles to the “massive use of public

funds and extensive state-federal sharing in the common

plan” of the Hill-Burton Program (323 F. 2d at 967).

The district court cited only two cases to support its

conclusion that Simkins was a reversal of prior law. These

decisions do not establish the proposition. They were not

overruled by Simkins. Nor do they detract from the force

of Burton, supra, and other decisions handed down prior to

August 9, 1963, and relied upon by the Court in Simkins.

Eaton v. Grubbs, 261 F. 2d 521 (4th Cir. 1958) cert,

denied 359 U. S. 984 dealt with discrimination at a hos

pital which did not participate in the Hill-Burton Pro

gram. The narrow confines of this first Eaton case are

demonstrated by language in Simkins, supra, and in the

second Eaton case, a decision based on neAv and expanded

allegations, Eaton v. James Walker Memorial Hospital,

329 F. 2d 710 (4th Cir. 1964).

In Simkins this Court stated: “ . . . The Eaton case did

uot involve any consideration of the Hill-Burton Program,

with its massive financial aid and comprehensive plans.

Moreover, no argument was presented in Eaton as to pos

sible fulfillment by a private body of a ‘state function’ pur

suant to an extensive state plan. And finally, the Eaton

15

case did not consider what effect overt state and federal

approval would have on otherwise purely private discrimi

nation” (323 F. 2d at 969). In the second Eaton case this

Court stated: “ [t]he opinion of this court [in the first Eaton

case] does not deal with [governmental construction sub

sidies] and indeed shows no awareness of it; nor was this

argued to the court” and “ . . . most importantly, the first

Eaton case did not consider the argument . . . that the

‘private’ hospital is fulfilling the function of the state”

(329 F. 2d at 712, 713).

Even as confined to its own facts, the first Eaton decision

was undermined in 1961 by Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U. S. 715, long before the August 9, 1963

racial discharge. This Court stated in Simkins: “ In light

of Burton, doubt is cast upon Eaton’s continued value as

precedent” (323 F. 2d at 968). See also Eaton v. James

Walker Memorial Hospital, 329 F. 2d 710, 712 (4th Cir.

1964). The Fifth Circuit had taken the same view of the

first Eaton case as early as May 17, 1962 when it decided

Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320, 323 (5th

Cir. 1962). Thus, even if Eaton correctly stated the law as

to Hill-Burton hospitals when decided in 1958 (and it did

not) it did not do so when the nurses were discharged in

1963, two years after the Burton decision.

A decision of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia,

Khoury v. Community Memorial Hospital, Inc., 203 Va.

236, 123, S. E. 2d 533 (1962), was also relied upon by the

district court. In Khoury, a physician claimed he was dis

charged in breach of contract by a hospital which had re

ceived Hill-Burton funds, and he sought, inter alia, to es

tablish that the hospital was a public rather than a private

corporation. Although the opinion of the Supreme Court

of Appeals does not state the significance of the distinction

16

to the physicians’ rights, the contention is rejected on the

authority of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 4 Wheat. 518

(1819) and state decisions.

The court did not decide any question of the scope of

the state or federal action requirement of Fifth and Four

teenth Amendments. It could not have considered such

questions pertinent because it nowhere mentions Burton,

supra, 365 U. S. 715 (1961), the latest Supreme Court pro

nouncement on the Fourteenth Amendment, or any other

federal decision besides the Dartmouth College case which,

of course, concerns itself with whether Dartmouth College

was a public or private corporation within the meaning of

the obligation of contract clause, Art. 1, §10 of the Consti

tution. As the Simkins decision demonstrates, Burton,

supra, and other federal decisions, and not Khoury, had

stated the proper scope of the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments long before August, 1963.

C. Dixie Hospital Was Specifically Obliged Not to

Discriminate on the Basis of Race as Early as

1956.

The second premise on which the decision below rests

assumes the Hospital was proceeding under the “ separate

but equal” provisions of the Hill-Burton Act at the time

of the nurses’ racial discharge, August 9, 1963, and that

these provisions constituted “a valid statute and regula

tion.” 5 (44a, 47a) This is a serious error with respect to

the obligations of the Hospital under the Hill-Burton Act,

for Dixie Hospital had agreed to operate “without discrim

ination because of race” as early as 1956 (58a).

Until 1964, when the Hill-Burton Act was amended to

eliminate reference to discrimination in light of Title V I of

5 42 U. S. C. $291e(f) 1958 ed.; 42 C. F. R. $53,112.

17

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. §$2000(d) et seq.

the Surgeon General was authorized to permit state plans

to meet the racial nondiscrimination requirement of 42

U. S. C. 291e(f) 1958 ed. by approving in certain narrow

circumstances separate facilities for “ separate population

groups.” 6 It was this exception to a general nondiscrimina

tion requirement which the Court declared unconstitutional

in Simkins, supra (329 F. 2d at 969). A hospital which did

not apply for and receive permission to maintain separate

facilities for “ separate population groups” however, was

always required to conform to the Hill-Burton Act re

quirement that all facilities built under the Act be made

available “without discrimination on account of race, creed

or color” (42 U. S. C. §291e(f) 1958 ed.; 42 C. F. R. §53.112;

see also §53.111).

The two hospitals involved in the Simkins case applied

for and received federal funds pursuant to the “ separate

but equal” exception, but as its application reveals plainly,

Dixie Hospital did not (58a). The Simkins hospitals took

federal funds pursuant to an exception to the nondiscrimi

nation provision and might claim that they relied on “a

valid statute and regulation” (44a) in denying the constitu

tional rights of Negro patients and physicians (Even this

argument, however, was rejected in Simkins, supra, 323

F. 2d at 970), but Dixie Hospital has no such equity to

assert. Dixie was never granted the “ separate but equal”

exemption to the nondiscrimination clause of the Act. It

received federal funds in 1 956 , seven years before the

racial discharge on the basis of its assurance that it would

not “discriminate on the basis of race, creed or color”

(58a) pursuant to a statute which, except in one clearly

6 Waiver o f the nondiscrimination assurance required a specific finding

by the Surgeon General and a state agency that there were equal facilities

available in the community for Negroes. 42 C. F. R. 553.112.

18

defined instance, not applicable to Dixie Hospital, pro

hibited racial and religious discrimination. 42 U. S. C.

§291e(f) 1958 ed.; 42 C. F. R. §53.112. Dixie Hospital,

therefore, had bound itself not to “ discriminate on the

basis of race” long before this cause of action arose.

Of course, even if the “ separate but equal” exception had

been granted to Dixie Hospital it had been rendered clearly

unconstitutional long before 1963, Simkins, supra (323 F. 2d

at 970). See Flemming v. South Carolina Electric and Gas

Co., 239 F. 2d 277 (4tli Cir. 1956) a decision in direct con

flict with the judgment below.7 See also Muir v. Louisville

Park Theatrical Assn., 347 U. S. 971 (vacated in light of

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (May 17,1954);

Gayle v. Browder, 350 U. S. 903 (1956); Dawson v. Mayor

and City Council of Baltimore, 350 U. S. 877 (1955); Colo

rado Anti-Discrimination Comm. v. Continental Airlines,

372 U. S. 714, 721 (1963).

D. Even if Simkins Reversed Prior Law it would

Apply to the Nurses.

We have discussed those respects in which the judgment

below must be reversed because founded on erroneous as

sumptions regarding the state of the law prior to Simkins,

supra, and the basis of the Simkins decision. Even assum

ing the district court to be correct, however, its conclusion

7 There, the district court dismissed a damage action by a Negro ex

cluded, June 22, 1954, from her seat on a bus operated by the defendant

company on the ground that “ the separate but equal doctrine o f Plessy

v. Ferguson as applied to the bus driver was not repudiated” by the

United States Court o f Appeals for the Fourth Circuit “ until after the

event on which the suit is based; and that it would be unjust to apply the

new rule retroactively and hold the bus company liable for damages for

an act which was lawful when it was performed” (239 F. 2d 278, 279).

This Court reversed on the ground that Brown v. Board o f Education,

347 U. S. 483 and Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (decided May 17,

1954) “ left no doubt that the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine had been

generally repudiated” in all areas o f public life.

19

that Simkins is only prospective in application does not

follow.

First, as this Court observed in Flemming v. South Caro

lina Electric and Gas Company, 239 F. 2d 277, 279 (4th

Cir. 1956) “In most jurisdictions it is held that reliance on

a statute subsequently declared unconstitutional does not

protect one from civil responsibility for an act in reliance

thereon which would otherwise subject him to liability.”

(Emphasis added.) The rule was applied in Flemming to

facts indistinguishable from the instant case. Although a

rule of prospective application is permissible to prevent

hardship or injustice, Great Northern R. Co. v. Sunburst

Oil & Refining Co., 287 U. S. 358, the general rule is that

in civil cases reversal does not insulate one from liability,

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649, 650, 665, 666. See also

Mosser v. Darrow, 341 U. S. 267 stating a new rule of lia

bility for trustees in bankruptcy but, nevertheless, impos

ing the burden of that rule retroactively.

Second, the Court in Simkins expressly rejected the only

basis on which the case could be given only prospective ef

fect. In Simkins, the hospitals argued with great force

that as they had been affirmatively permitted to discrimi

nate by Act of Congress and Executive decision relief as

to them should be denied. The Court met this argument

head-on and rejected it on the basis of the nature of the

Constitution and the equities involved:

This court does not overlook the hospitals’ conten

tion that they accepted government grants without

warning that they would thereby subject themselves to

restrictions on their racial policies. Indeed, they are

being required to do what the Government assured

them they would not have to do. But in this regard,

the defendants, owners of publicly assisted facilities,

20

can stand no better than the collective body of South

ern voters who approved school bond issues before the

Brown decision or the private entrepreneur who out

fitted his restaurant business in the Wilmington Park

ing Garage before the Burton decision. The voters

might not have approved some of the bond issues if

they had known that the schools would be compelled

to abandon their historic practice of separation of the

races, and the restaurateur might have been unwilling

to venture his capital in a business on the premises

of the Wilmington Parking Authority if he had antici

pated the imposition of a requirement for desegregated

service. What was said by the Supreme Court in

Burton in regard to the leases there in question is

pertinent here:

[W]hen a State leases public property in the man

ner and for the purpose shown to have been the case

here, the proscriptions of the Fourteenth Amendment

must be complied with by the lessees as certainly as

though they were binding covenants written into the

agreement itself. (Emphasis added.) 365 U. S. at

p. 726.

We accord full weight to the argument of the de

fendants, but it cannot prevail. Not only does the

Constitution stand in the way of the claimed immunity

but there are powerful countervailing equities in favor

of the plaintiffs. Racial discrimination by hospitals

visits severe consequences upon Negro physicians and

their patients.

The Court in Simkins, therefore, conclusively rejected

an attempt to limit that decision to the future.

Third, the Negro physicians and patients in Simkins

were granted relief for causes of action which arose long

21

before the nurses’ racial discharge, August 9, 1963. The

complaint in Simkins was filed February 12, 1962 and the

acts of the two Greensboro, North Carolina hospitals which

the court found to be unconstitutional took place prior to

the filing of that complaint. If the view of the district

court as to the prospective nature of the holding in Simkins

is to be sustained, an exception must be carved out for the

litigants in Simkins.

Fourth, in the Second Eaton decision, 329 F. 2d 710

(4th Cir. 1964) Simkins already has been applied to a

cause of action which arose prior to the date of the Simkins

decision.8

Fifth, the case relied upon below to support application

of Simkins prospectively, Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U. S.

618, has been misapplied. Linkletter holds that Mapp v.

Ohio, 367 U. S. 643 (which expressly overruled Wolf v.

Colorado, 338 U. S. 25) would not be applied to cases

finally decided prior to Mapp in which federal habeas

corpus was not brought until subsequent to Mapp. In

Mapp, the Court incorporated the rule which excluded

evidence seized in violation of the Fourth Amendment into

the Fourteenth Amendment. Linkletter found that the pur

pose of the exclusionary rule is “ to deter the lawless action

of police,” a purpose which could not be served by making

Mapp retroactive (381 U. S. 636, 637). Here, the ends

of the Fourteenth Amendment—to secure Negro rights to

equal protection—are clearly served by applying Simkins.

Another consideration in the decision to apply Mapp

prospectively was the probability that a large number of

prisoners would go free, probably without trial. The Court

8 Tlie cause o f action in the second Eaton case also arose prior to

August 9, 1963.

22

was concerned with the administration of justice and the

integrity of the judicial process. “ To make the rule of

Mapp retrospective would tax the administration of justice:

hearings would have to be held on the excludability of

evidence long since destroyed, misplaced, or deteriorated.

If it is excluded, the witnesses available at the time of the

original trial will not be available or if located, their

memory will be dimmed. To thus legitimate such an

extraordinary procedural weapon will seriously disrupt

the administration of justice” {Ibid). None of these con

siderations even remotely apply to the rights asserted by

Negro nurses to relief against racial discharge. Moreover,

the decision does not even have general application in the

criminal field.9

Sixth, the equities in favor of these nurses are over

whelming. They compel application of Simkins. The nurses

sought merely to overcome the demoralizing and degrading

effects of racial segregation by seating themselves at a

table in the cafeteria rather than carrying their food

from that cafeteria to the Negro “dining room” in a Hos

pital which had pledged the United States, in order to

receive over 1.7 million dollars, that it would not discrim

inate on the basis of race. They caused no commotion or

disturbance of any kind and they directed themselves to

discrimination in hospitals, the severe consequences of

which this Court has concluded are “powerful counter

vailing equities” touching “health and life itself” Simkins,

supra (323 F. 2d at 967, 970).

9 In the criminal field, aside from Linkletter supra, and its peculiar

circumstances, there has been no reluctance to make new rules retroactive,

see e.g., Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U. S. 12 (1958) applied to a 1925 convic

tion in Eskridge v. Washington, 357 U. S. 214; Gideon v. Wainwright,

372 U. S. 325 has also been applied retroactively.

23

Finally and fundamentally, the whole issue posed by the

decision below—whether the rule of Simkins is to be “ retro

spective”—has relevance only to the appellants claim for

back pay, and no relevance at all to their claim for prospec

tive relief based on the law as it is now clearly understood

by all, i.e., for an order directing that they forthwith be

put to work at the Hospital in the jobs of which they were

unlawfully deprived. The familiar principle is that equity

courts apply prospective relief on the basis of the law as

it exists at the time the relief is granted. These nurses

want the Court to order the hospital to give them their

jobs now and for the future. That part of their claim for

relief does not involve even a hint of ex post facto un

fairness. As far as reinstatement is concerned, the entire

debate about retrospectivity is beside the point.

II

Negro nurses, racially discharged from a Hill-Burton

Hospital, prohibited from discrimination by the Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments, are entitled to injunc

tive relief ordering reinstatement with back pay.

The district court also expressed “ serious doubts”

whether Simkins, supra, “permits an action for wrongful

discharge” against a Hill-Burton Hospital (47a). As

suming arguendo that Dixie Hospital is prohibited from

racially discharging employees, the district court held that

the Simkins decision does not permit an action for an in

junction ordering reinstatement, with back pay, but only

an action for damages (47a).

The complaint prayed for an order reinstating the nurses

and granting them back pay from the time of the racial

discharge; money damages were not sought, the complaint

24

alleging “no plain, adequate or complete remedy to redress

these wrongs other than this suit for an injunction.” Any

other remedy would “deny substantial relief,” cause “ ir

reparable injury and occasion damage, vexation and in

convenience to plaintiffs” (4a, 10a, 11a).

By seeking reinstatement with back pay for the unconsti

tutional discharge, the nurses pray for what is the only

effective and meaningful remedy which secures their con

stitutional rights. They desire the return of their rights

through prospective relief: an order restoring their jobs

for the future. They also seek back pay, traditional ac

companiment to reinstatement, in order to restore status

fully as if the wrongful discharge had not occurred. The

nurses do not seek damages because, regardless of the

recovery, they could not repair the wrong and return their

jobs. Constitutional rights would be often empty promises

if another needed only to pay damages in order to deprive

them. This is especially true because the rights involved

are “inherently incapable of pecuniary valuation” Jordan

v. Hutcheson, 323 F. 2d 597, 601 (4th Cir. 1963).

The district court treated this action narrowly, as if it

were merely another for breach of contract. The nurses,

however, do not seek relief on any theory of contract or

agency law; their right to relief is grounded in the Con

stitution itself. The Hospital, having received massive sup

port from federal and state governments by participating

in the Hill-Burton program, was bound by the Constitution

when it racially dismissed the nurses. They are entitled,

therefore, to relief which secures the rights which the

Hospital denied.

The notion, also suggested by the court below, that a

Hill-Burton hospital is subject to the Constitution to the

extent that it must treat Negro patients and accept Negro

25

physicians and dentists as staff members without discrim

ination of any kind, but, on the other hand, is free to

racially discharge Negro employees is unsupportable.

When the restraints of the Constitution apply, a person

may not be dismissed from employment for reasons which

are patently arbitrary or discriminatory.10 In Simkins v.

Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F. 2d 959 (4th

Cir. 1963), and Eaton v. James Walker Memorial Hospital,

329 F. 2d 710 (4th Cir. 1964), relying on a long line of

decisions applying the principles of Brown v. Board of

Education to every area of public life, this Court expressly

held that Negro physicians and dentists were entitled to

injunctive relief ordering their placement on the medical

and dental staffs of Hill-Burton hospitals. Certainly Ne

gro nurses are entitled to as much protection as that ac

corded to Negro physicians and dentists. It is difficult

to conceive the reasoning which would permit protection

of the physicians and dentists in Simkins and Eaton, but

deny it to the nurses here. As far as race is concerned,

the Dixie Hospital is as bound to nondiscrimination as the

United States and the State of Virginia, its partners in

the Hill-Burton program. Colorado Anti-Discrimination

Comm. v. Continental Airlines, 372 U. S. 714, 721. As the

Supreme Court stated, when applying the principle to

a restaurateur in Burton, supra (365 at 726), “ . . . the

proscriptions of the Fourteenth Amendment must be com

10 Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183, 192 (invalidation o f loyalty

oath applied to teachers which based employability solely on the fact

o f membership in certain organizations); Cramp v. Board o f Public

Instruction, 368 U. S. 278, 288 (public school teacher may not be dis

charged for failure to subscribe to unconstitutionally vague oath) ;

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U. S. 488, 495-96 (appointee to the office of

Notary Public may not be denied permission for failure to subscribe to

religious oa th ); Schware v. Board o f Bar Examiners, 353 U. S. 232

(applicant for admission to the Bar may not be excluded from practice

when evidence does not support ground o f exclusion).

26

plied with by the lessee as certainly as though they were

binding covenants written into the agreement itself.” 11

The district court recognized that the remedy of rein

statement, with back pay sought by the nurses is one which

is commonly granted to employeees wrongfully discharged

by government as well as in the labor-relations field (47a),

but concluded, without elaboration, that injunctive relief

was not appropriate here.

The principle on which such remedy may be denied to

employees protected by the Constitution because of govern

mental action while granted to the employees of govern

ment is not readily apparent. There is no reason suggested

why an injunction, the only effective remedy, is not relief

to which the nurses are “ entitled,” Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, Rule 54(c). On the contrary, the rule is that

these nurses, having established their substantive rights,

are “ entitled” in a federal court to any traditional remedy

which offers the relief they seek.

Decisions permitting reinstatement, back pay, and other

forms of injunctive relief which amounts to the same thing

are many, and they are not limited to those occasions where

a specific statutory provision reinstatement or back pay or

both exists. In Service v. Dalles, 354 U. S. 365, the Supreme

Court granted injunctive relief ordering reinstatement with

back pay for a wrongfully discharged federal employee

without reference to statutory authorization. Accord:

11 It should not be forgotten that it is state and federal responsibility

which give rise to the prohibitions to the Fifth and Fourteenth Amend-

mens. These Amendments are addressed to government and cast upon

the states and the federal government the affirmative obligation to assure

nondiscrimination. To permit Dixie Hospital to discriminate in employ

ment is to permit the State o f Virginia and the United States to deny

due process o f law and equal protection o f the laws because state and

federal governments are deeply involved in the financing, regulation, and

planning o f Dixie Hospital.

27

Vitarelli v. Seaton, 359 U. S. 353; Greene v. McElroy, 360

U. S. 474, 491, 492 (Fifth Amendment protects employee of

defense contractor from arbitrary interference with em

ployment relationship).

It is settled beyond question that Negro employees sub

ject to discriminatory practices based on race are entitled

to relief by injunction as well as damages in the federal

courts. Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192; Con

ley v. Gibson, 355 U. S. 41. In these and other, similar, de

cisions injunctive relief was granted for breach of a duty

arising from statute. Here, the right of the nurses is pre

eminent, arising as it does directly from the due process

and equal protection clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments.

As early as IVickersham v. United States, 201 U. S. 392

(1906) the Court exercised its inherent equitable powers to

reinstate a federal employee with back pay although there

was no statutory authority for back pay on the ground that

the removal was without legal effect. In Slochoiver v. Board

of Education, 350 U. S. 551, the Supreme Court found that

a school teacher could not be removed from his position for

exercise of his constitutional privilege against self incrimi

nation. See also cases cited in note 10, supra p. 25. In

N. L. R. B. v. Jones & Laughlin S. Cory., 301 U. S. 47, 48, the

Supreme Court justified Congress’ power to authorize the

National Labor Relations Board to reinstate employees,

with back pay, on the basis of an established judicial power

to do so. In Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship Committee of

Steel Workers, 223 F. Supp. 12 (N. D. 111. 1963), vacated on

other grounds, 332 F. 2d 243 (7th Cir. 1964), the district

court ordered labor unions, subject to the restraints of the

Constitution against racial discrimination because of fed

eral and state support, to accept named Negro plaintiffs as

apprentices. In Thomas v. United' States, 289 F. 2d 948,

28

949, 951 (Ct. Cl., 1961) the Court exercised its equitable

power to grant back pay, there being no statutory authori

zation. The Court also considered a statute which only

allowed back pay if there was reinstatement, but stated that

the court was empowered to grant back pay: “Even where

no reinstatement has been ordered judgment for back pay

may be given if the facts of the case justify such action

[citing cases].” Similarly, Daub v. United States, 292 F. 2d

895 (Ct. Cl., 1961) gave recovery for back pay lost between

discharge and reinstatement even though the employee was

not entitled to recover under any statute. Accord: Cad-

dington v. United States, 178 F. Supp. 604 (Ct. Cl., 1959)

(equity demands relief).

This Court is also authorized by the provisions of 42

U. S. C. §1983 to grant broad relief “ in equity or other

proper proceeding for redress.” Congress in enacting

§1983 (RS§1979: §1 of the Ku Klux Act of 1871) intended

to provide a comprehensive, federal remedy for depriva

tions of the Fourteenth Amendment by those, such as the

Dixie Hospital, acting “under color of law.” McNeese v.

Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668, Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S.

167. Literally thousands of civil actions have been brought

under §1983 to redress deprivation of the constitutional

rights; the experience of this jurisprudence demonstrates

beyond question the broad discretion of this Court to secure

constitutional rights. See e.g., Alston v. School Board of

City of Norfolk, 112 F. 2d 992 (4th Cir. 1940) (Board re

strained from making racial distinction in fixing salary of

Negro and white teachers).

When a constitutional violation is involved the reasons

for granting just relief are all the more pressing; effective

remedies for constitutional deprivations are as important

as constitutional rights themselves. Compare Mapp v. Ohio,

367 U. S. 643 with Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25. One of

the primary grounds for overruling Wolf, and elevating the

29

exclusionary rule to the level of constitutional principle,

was the discovery that remedies other than the exclusionary

rule were ineffective protections of Fourth Amendment

rights. See Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U. S. 618, 634.

Unless the nurses are taken back into the employ of the

Hospital, the plain inference is that institutions subject to

the Constitution such as Dixie Hospital may racially dis

criminate at no greater sanction than damages awarded by

a jury. Such a conclusion is directly inconsistent with Sim-

kins, supra and Eaton, supra, where the hospitals were

ordered to accept Negro physicians and dentists without

regard to race, for it would permit them, there being no

significant distinction in this regard between doctors and

nurses, to dismiss the physicians and dentists because of

race and pay whatever damages a jury would assess. A

school board might entertain hopes of removing Negro

teachers only subject to the same sanction.12 Cf. Bradley v.

School Board of the City of Richmond-, Gilliam v. School

Board of City of Hopewell, (U. S. Sup. Ct., No. 415 and

No. 416, October Term 1965 vacating and remanding 345

F. 2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965); 345 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1965)).13

12 This Court may soon be called upon to review racial discharge of

Negro teachers. See Rackley v. Orangeburg School District (No. 8458,

E. D. S. C .) ; Williams v. Sumter School District (No. 1534 E. D. S. C .).

13 A number of other decisions invoke the specific remedy sought here

to safeguard constitutional rights. In Dixon v. Alabama State Board of

Education, 294 F. 2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961) cert, denied 368 U. S. 930, the

Fifth Circuit enjoined expulsion o f Negro college students from a tax

supported college without constitutional safeguards o f notice and hearing.

Although the “ misconduct” for which the students had been expelled was

not definitely specified, all o f them had participated in a peaceful protest

against racial segregation at a lunch counter in the basement o f the

Montgomery County Courthouse. In Knight v. State Board o f Educa

tion, 200 F. Supp. 174 (M. D. Tenn. 1961) 13 Negro students had been

arrested as “ freedom riders” in Jackson, Mississippi. Their reinstate

ment was ordered on the authority o f the Dixon case. See also Woods

v. Wright, 334 F. 2d 369 (5th Cir. 1964) reinstating thousands o f

Birmingham, Alabama public school children expelled because they par

ticipated in peaceful protests against racial segregation.

30

The consequence of such a rule to the public interest in pre

venting racial distinctions, which are “by their very nature

odious to a free people,” could not be more disastrous.14

These unpleasant examples will not occur because this

Court has the power to frame decrees which provide effec

tive relief for denial of constitutional rights. See e.g.

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U. S.

218, 234 (federal courts have broad powers to enter a decree

which will enjoin state supported segregation); Alexander

v. Hillman, 296 U. S. 222, 239.

There is no suggestion in the cases described above,

where the remedy sought here was granted, that a jury is

required to order back pay. However, the district court

suggested, without deciding, that a jury might be required

on the issue of back pay or of the extent to which the nurses

have minimized loss of earnings (48a). But back pay has

always been recognized as equitable relief, issued to restore

status, or as an incident to reinstatement which protects

against wrongful discharge, without conferring the right

of trial by jury. When §10(c) of the National Labor Rela

tions Act of 1935, which authorizes the National Labor

Relations Board to grant “ reinstatement of employees with

or without back pay,” was challenged as abrogating trial

by jury under the Seventh Amendment, the constitutional

ity of the section was upheld on the ground that such

awards are equitable in nature, N. L. R. B. v. Jones &

Laughlin S. Cory., 301 U. S. 1, 47, 48; Agwilines, Inc. v.

National Labor Relations Board, 87 F. 2d 146, 151 (5th Cir.

1936):

They provide for public proceedings, equitable in their

nature. They exert power to restore status disturbed

in violation of statutory injunction similar to that ex

14 Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100.

31

erted by a chancellor in issuing mandatory orders to

restore status.

Nor do the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 38(a)

require a jury trial on the back pay issue, for the Rules

do not enlarge the scope of the constiutional right to a jury

trial. Ettelson v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 137 F. 2d 62,

65 (3rd Cir. 1943) cert, denied 320 U. S. 777.

Moreover, the issue of mitigation of loss of earnings does

not entitle the Hospital to a jury trial. Even in cases, unlike

this, where the relief sought is not solely equitable, “ there

is no right to trial by jury on an issue of damages that is

incidental to the equitable relief sought by plaintiff [s], the

general rule being that equity having acquired jurisdiction

of a cause it should dispose of the entire controversy”

Crane Co. v. Crane, 157 F. Supp. 293, 295 (W. D. Ga. 1957).

Equity often grants relief in the form of money damages as

an adjunct to equity jurisdiction without trial by jury on

the issue of damages. See e.g. Coca Cola Co. v. Old Domin

ion Beverage Corp., 271 F. 600, 602, 604 (4th Cir. 1921);

Chappell & Co. v. Palermo Cafe Co., 249 F. 2d 77, 81 (1st

Cir. 1957); Hirsch v. Glidden Co., 79 F. Supp. 729, 730

(S. D. N. Y. 1948); Admiral Corp. v. Admiral Employment

Bureau, 161 F. Supp. 629 (N. D. 111. 1957).

In conclusion, Alexander v. Hillman, 296 U. S. 222, 239

is apposite. Federal courts of equity, the Supreme Court

said, may “ suit proceedings and remedies to the circum

stances of cases and formulate them appropriately to safe

guard, conveniently to adjudge and promptly to enforce

substantial rights of all parties before them.” Appellants,

racially discharged in violation of the Constitution, despite

representations by the Hospital to the United States that

it would not discriminate, are entitled to the relief prayed.

32

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the foregoing reasons, appellants

pray the judgment below be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Derrick A. B ell, Jr.

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

W illiam A. S mith

17 East Lincoln Street

P. 0. Box 242

Hampton, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C.