McKinnie v. Tennessee Transcript of Record

Public Court Documents

March 5, 1963 - March 5, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McKinnie v. Tennessee Transcript of Record, 1963. 0c9295a8-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f21187be-4e71-498c-8244-07f70e1c4224/mckinnie-v-tennessee-transcript-of-record. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

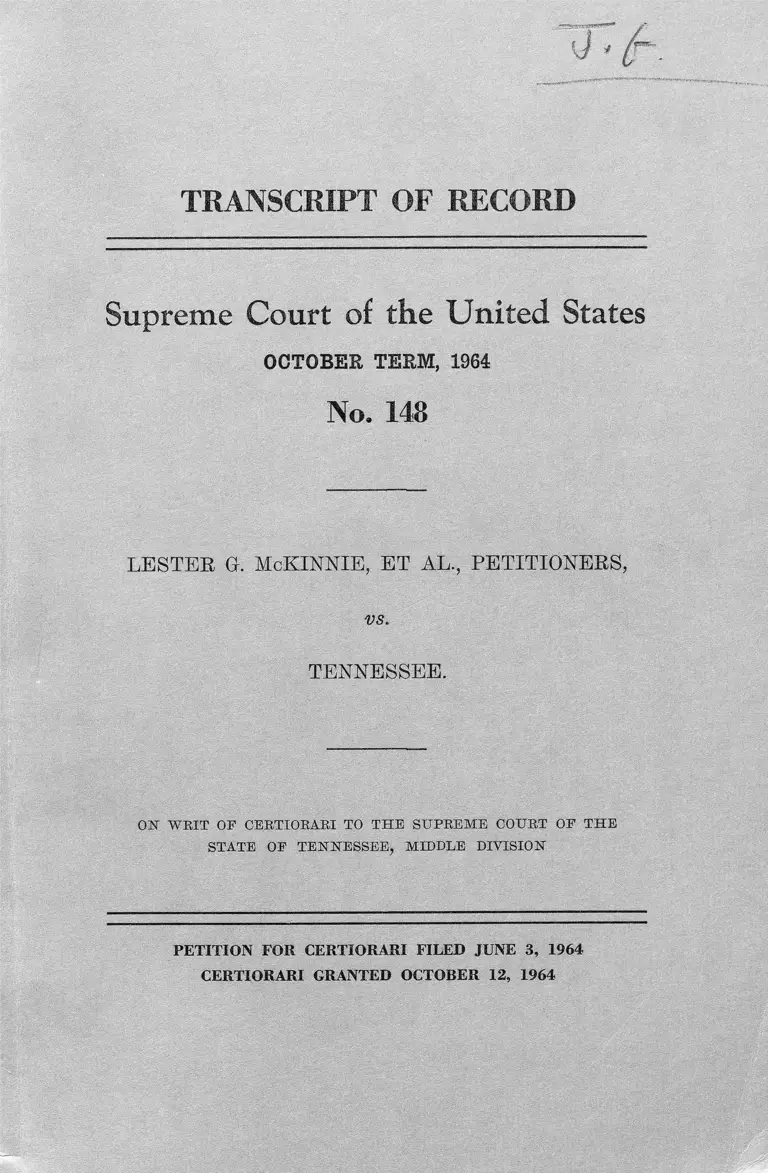

TRANSCRIPT OF RECORD

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1964

No. 148

LESTER G. McKINNIE, ET AL., PETITIONERS,

vs.

TENNESSEE.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF TENNESSEE, MIDDLE DIVISION

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI FILED JUNE 3, 1964

CERTIORARI GRANTED OCTOBER 12, 1964

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1964

No. 148

LESTER Gf. McKINNIE, ET AL., PETITIONERS,

vs.

TENNESSEE,

ON WRIT ON CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OP THE

STATE OF TENNESSEE, MIDDLE DIVISION

I N D E X

Original Print

Record from the Criminal Court of Davidson

County, Tennessee, Division Two

Minute entry of Grand Jury R eport__________ 8 1

Presentment __________________________________ 9 1

Motion of defendants to quash presentment____ 23 6

Motion under advisement ______________________ 25 7

Order overruling motion to quash presentment „ 27 8

Motion of defendants to quash presentment, etc. 28 9

Order overruling motion to quash presentment . 29 10

Minute entry of arraignment— plea ____________ 30 11

Minute entry— 5 jurors selected, special venire

ordered; respited, March 5, 1963 ____________ 31 11

Minute entry— 3 jurors selected, special venire

ordered; respited, March 6, 1963 ____________ 33 12

Minute entry—jury complete, March 7, 1963 ___ 35 13

Minute entry— portion of proof, respited ______ 37 14

Verdict _______________________________________ 38 15

Judgment_____________________________________ 39 16

Motion for a new trial ________________________ 41 17

Order overruling motion ______________________ 53 27

Bill of exceptions filed ________________________ 63 28

Record Press, Printers, New Y ork, N. Y., November 6, 1964

INDEXn

Original Print

Record from the Criminal Court of Davidson

County, Tennessee, Division Two— Continued

Clerk’s certificate (omitted in printing) ________ 64 28

Defendants’ Bill of Exceptions _________________ 1 29

Appearances _______________________________ 1 29

Colloquy ------------------------------------------------------ 2 30

Examination of prospective juror, A. L. Dick

erson --------------------------- 3 30

Examination of prospective juror, James L.

E therly----------------------------------------------------- 27 39

Examination of prospective juror, Thomas

B row n------------------------------------------------------- 199 40

Examination of prospective juror, Rosa Lee

Copeland _________________________________ 384 46

Examination of prospective juror, Floyd G.

Davis ------------------------------------------------------- 388 49

Examination of prospective juror, Herbert

Amie --------------------------------------------------------- 446 53

Examination of prospective juror, Granville

Williams _________ 510 70

Examination of prospective juror, W. T. Moon 659 74

Examination of prospective juror, Wendall H.

Cooper ----------------------------------------------------- 751 81

Swearing in of jury, reading of presentment to

jury, and defendants’ plea of not guilty____ 763 86

Evidence on behalf of the State: _____________ 764 88

Testimony of Woodrow Wilson Carrier—

direct _______________ 764 88

cross ________________ 775 94

Charles E. Edwards—

direct _______________ 776 95

cross ------------------------- 784 100

redirect _____________ 795 106

recross --------------------- 795 106

Mrs. Ann M. Edwards—-

direct _______________ 796 107

cross ------------------------- 804 111

Mrs. Lottie Martin—

direct ----------------------- 808 114

cross ------------------------- 814 117

INDEX 111

Record from the Criminal Court of Davidson

County, Tennessee, Division Two— Continued

Defendants’ Bill of Exceptions— Continued

Evidence on behalf of the State— Continued

Testimony of Woodrow Wilson Carrier—

(recalled) —

Original

cross ________________ 822

redirect _____________ 825

Thomas R. Beehan—

direct _________ i._____ 826

cross ________________ 837

Owen Smith—

direct _______________ 849

Offers in evidence ______________________ 858

Testimony of Owen Smith—

cross ______________ _ 872

Mickey Lee Martin—

direct _______________ 887

cross ________________ 892

Mrs. Katherine

(Vaulx) Crockett—

direct _______________ 896

cross ________________ 902

redirect _____________ 929

Vaulx Crockett—

direct _______________ 930

cross ________________ 940

Mrs. George W. Forehand—

direct _______________ 967

cross ________________ 974

redirect _____________ 991

Golden Cornelius Alley—

direct _______________ 992

cross ________________ 1000

redirect _____________ 1015

Johnny Claiborn—

direct _______________ 1017

cross ________________ 1022

Print

123

124

125

131

138

143

153

161

164

166

169

185

185

192

208

212

222

223

228

236

238

241

IV INDEX

Record from the Criminal Court of Davidson

County, Tennessee, Division Two— Continued

Defendants’ Bill of Exceptions— Continued

Evidence on behalf of the State— Continued

Testimony of M. L. Pyburn—

direct _______________ 1023 241

cross ________________ 1027 244

Sanford S. Moran—•

direct _______________ 1033 248

cross ________________ 1036 250

Mrs. Alma R id le y -

direct __ 1042 253

cross ________________ 1057 262

redirect _____________ 1058 263

Otis Williams—

direct _______________ 1059 264

Interrogation of Mr. Collins________________ 1061 265

Testimony of Otis Williams—

direct _______________ 1065 268

cross ________________ 1077 276

State closes its case___________________________ 1102 291

Reporter’s certificate (omitted in printing) ------ 1103 291

Charge of the Court___________________________ 1104 292

Defendants’ Special Requests No. 1, No. 2, No. 3

and No. 4 and denial thereof________________ 1123 307

Defendants’ Special Request No. 1, as revised by

the C ourt___________________________________ 1127 311

Verdict _______________________________________ 1128 311

Judge’s certificate to bill of exceptions_________ 1133 314

Proceedings in the Supreme Court of the State of

Tennessee, Middle Division, Nashville --------------- 1134 315

Opinion, Burnett, Ch. J. -------------------------------------- 1134 315

Judgment _______________________________________ 1151 326

Stay order, January 8, 1964 ____________________ 1152 327

Opinion on petition to rehear, Burnett, Ch. J. ____ 1153 328

Order denying petition to rehear ________________ 1155 329

Stay order, March 5, 1964 ----------------------------------- 1156 330

Clerk’s certificate (omitted in printing) --------------- 1157 330

Order allowing certiorari ------------------------------------ 1159 331

Original Print

1

[fol. 8]

IN THE

CRIMINAL COURT OF DAVIDSON COUNTY,

TENNESSEE, DIVISION TWO

No. 15866

State of Tennessee,

v.

L ester G. M cK innie, J ohn R. Lewis, F rederick L eonard,

John J ackson, Jr., Nathal W inters, F rederick Har

graves, H arrison Dean, and A llen Cason, J r.

Minute E ntry op Grand Jury R eport—

December 12,1962

Thereupon the Grand Jury for Davidson County, Ten

nessee, came into open court and after being regularly

called presented the following bills of indictments and pre

sentments which are in the following words and figures, to

wit:

Copy of indictment follows:

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morning

at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge

[fol. 9]

I n the Criminal Court op Davidson County, Tennessee

D ivision T wo

P resentment—December 12,1962

The Grand Jurors for the State of Tennessee, duly

elected, impaneled sworn, and charged to inquire for the

body of the County of Davidson and State aforesaid, upon

their oath aforesaid, present:

2

That Lester G. McKimrie, John R. Lewis, Frederick

Leonard, John Jackson, Jr., Nathal Winter, Frederick Har

graves, Harrison Dean, and Allen Cason, Jr., heretofore,

to wit, on the 21st day of October, 1962, and prior to the

finding of this presentment, with force and arms, in the

County aforesaid, unlawfully, wilfully, knowingly, delib

erately, and intentionally did unite, combine, conspire, agree

and confederate, between and among themselves, to violate

Code Section 39-1101-(7) and Code Section 62-711, and

unlawfully to commit acts injurious to the restaurant busi

ness, trade and commerce of Burrus and Webber Cafeteria,

Inc., a corporation, located at 226 6th Avenue North, Nash

ville, Davidson County, Tennessee, in the following manner

and by the following means, to w it:

On the day and date aforesaid, and for many months

and years prior thereto, the said Burrus and Webber Cafe

teria, Inc., had built up and established a restaurant and

cafeteria, elaborately furnished and equipped, known as the

B & W. Cafeteria, located at said address in the heart of

the business, commercial and uptown district of Nashville,

Tennessee, in a building fronting on the east side of 6th

Avenue North, and extending back to the westerly margin

of an alley in the rear, which dining room and cafeteria

had two long cafeteria lines, dining tables and chairs on

the ground level and additional dining tables and chairs on

the mezzanine level, with a large seating capacity for cus

tomers, patrons and clientele of said B & W. Cafeteria,

which had established itself by reputation as serving fine

foods, and which said cafeteria daily served hundreds of

white patrons, customers and clientele.

[fol. 10] The entrance from said 6th Avenue North into

said cafeteria is effected by a double door at the northwest

corner of said cafeteria, which leads into a vestibule, small

in area, with a second set of double doors on the east side

of said vestibule; all customers of said cafeteria enter and

leave through said vestibule.

The owners of said cafeteria and restaurant, which was

privately owned, had established a rule that they would re

ceive, admit and serve only such persons as customers,

patrons and clientele as said corporation elected to admit,

3

receive and serve in said cafeteria; and said Burras and

Webber Cafeteria, Inc., had reserved the right to control

the access and admission or exclusion of persons to said

cafeteria as the owners deemed proper, in their discretion

as the owners of private property; and under the provisions

of Section 62-710 of the Code of Tennessee, the owners of

said cafeteria reserved the right not to admit and to exclude

from said cafeteria any person the owners, for any reason

whatsoever, chose not to admit or serve in said cafeteria.

Among the rules established by the owners of said B & W

Cafeteria was one that they would serve food only to per

sons of Caucasian descent, or white persons, and not to

serve food to persons of African descent, or colored per

sons ; and said B & W Cafeteria was known to the general

public as a cafeteria and dining place, privately owned,

serving food only to white persons.

In the said City of Nashville at said time there were

numerous other dining rooms, restaurant, cafeterias and

places serving food, some of which served food only to

colored persons, and some serving food to both white and

colored persons, known as “integrated” restaurants, dining

rooms, cafeterias and food places, many of which were in

the immediate vicinity or within a few blocks of said B. & W.

Cafeteria, all of which was then and there well known to the

[fol. 11] defendants, hereinbefore named; and on said Oc

tober 21, 1962, food was available to said defendants at

numerous eating places in Nashville in the general vicinity

of said B & W Cafeteria.

The said defendants, Lester G. MeKinnie, John R. Lewis,

Frederick Leonard, John Jackson, Jr., Nathal Winter, Fred

erick Hargraves, Harrison Dean and Allen Cason, Jr., are

persons of African descent or colored persons; and said

defendants unlawfully, wilfully, deliberately, and intention

ally did unite, combine, conspire, agree and confederate,

between and among themselves, to conduct what is known

as “ sit-in” affairs, by going to divers restaurants, dining

rooms and cafeterias in Nashville, Davidson County, Ten

nessee, serving only white persons food, to enter said din

ing rooms, restaurants and cafeterias well knowing that

only white persons were being or would be served, and fur

ther well knowing that colored persons would not be served

4

food therein; and after being denied entrance thereto and

after being denied food service, and after being requested

to leave such dining rooms, restaurants and cafeterias, the

said defendants did conspire to block the entrance or vesti

bule of said B & W Cafeteria to prevent customers, patrons

or clientele from entering, and to block or prevent those

already therein and who had been served food and had

finished their meals from leaving said cafeteria by means of

the only regular entrance or exit thereto, being the above

described vestibule, all being contemplated to be done, well

knowing that their presence as “ sit-ins” was likely to pro

mote disorders, breaches of the peace, fights or riots by

patrons, customers and clientele of such segregated cafe

teria ;

And the said defendants, on said October 21, 1962, well

knew that prior or similar acts of “ sit-in” in Nashville had

resulted in fights, breaches of the peace, disorders, brawls

and riots previously, requiring the calling of police and

peace officers to quell conditions resulting therefrom, as at

least one of the defendants herein named had previously

participated in several of such “ sit-ins” conducted at other

dining rooms and restaurants in Nashville prior to October

21,1962.

[fol. 12] The said defendants are college students and are

strong advocates of an integration movement now being

conducted in Davidson County, Tennessee, and are engaged

in a movement to coerce, compel, and to intimidate owners

of restaurants, dining rooms and cafeterias serving only

white persons to “ integrate”, or to admit and serve food

to persons of African descent or colored persons against

the wishes, rule and established policy of the owners of such

segregated restaurants, dining rooms and cafeterias.

As an overt act in the furtherance of said unlawful con

spiracy, on Sunday, October 21, 1962, shortly after noon,

when the said B & W Cafeteria was engaged in serving

food to numerous customers, patrons, and clientele, and

while many persons were coming in and out of said cafe

teria, the said defendants did assemble at a point near said

cafeteria, and then as a group did go to the 6th Avenue

door of said cafeteria, and did enter into said vestibule,

with intent to get through the second doors of said vestibule,

5

and to enter one of the serving lines within said cafeteria

in an effort to obtain food and service therein;

At said door the owners of the B. & W. Cafeteria had

placed a guard to prevent such “ sit-in” movement; said

guard was compelled to block the further entrance at the

second door; whereupon said defendants did form a block

within said vestibule, preventing customers and patrons

from either entering from the street or from coming out of

said cafeteria after finishing their meals; and said con

spirators did further attempt to force their way inside the

main cafeteria sections, did push around and shove white

patrons therein, which conduct continued for a period of

more than thirty minutes during one of the busiest hours

of business at said cafeteria; and as a further overt act in

the furtherance of said conspiracy, said defendants did re

fuse to leave said vestibule and cafeteria when requested

and demanded by proper officers and employees of said

cafeteria.

[fol. 13] During said period of time so spent by said de

fendants in said vestibule, said defendants knowingly, de

liberately and intentionally did place said B & W. Cafeteria

and the persons lawfully therein in excitement, turmoil and

confusion; the orderly conduct of the business of said cafe

teria was greatly upset, disrupted and obstructed; nu

merous persons gathered within and without said cafeteria

by reason of said acts and conduct of the defendants, which

said defendants then and there well knew were calculated

to produce disorder, breaches of the peace, confusion, brawls

and turbulent and riotous conduct, and which was done by

said defendants with a view to commit acts injurious to

the business of the B & W Cafeteria, its trade and com

merce, which was injured therefrom;

Contrary to the form of the statutes in such cases made

and provided, in violation of Section 39-1101 of the Code of

Tennessee, and against the peace and dignity of the State

of Tennessee.

6

[fol. 23]

I n the Criminal Court oe Davidson County, T ennessee

D ivision T wo

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

M otion oe Defendants to Quash P resentment—

Piled January 10,1963

Come the defendants and move the Court for an order

quashing the presentment and dismissing this cause, for

the following reasons:

1. Because the State of Tennessee, through its judicial

officers in their official capacities are trying to enforce a

policy of racial discrimination, same being in violation of

rights protected under the Fourteenth Amendment of the

United States Constitution.

2. Because the acts relied on by the State arising under

Section 62-711 of the Code of Tennessee, do not refer to

the exclusion of persons of designated race or color since

such designation would not be in harmony with the pro

vision of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States

Constitution and if so interpreted, could not be enforced by

the State or any of its officials acting in their official

capacities.

3. Because the acts charged in the third and fourth para

graphs or any paragraph or parts of the presentment do

not constitute a criminal act.

[fol. 24] 4. Because the presentment does not allege or

show that the defendant conspired to do an unlawful act

or that they conspired to do an unlawful act in an unlawful

manner.

5. That the rights relied upon by the defendants are

individual and personal rights created by the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment and a denial thereof cannot be enforced by the State

7

or any person acting in an official capacity as representa

tive of the State.

Wherefore, defendants move the Court for an order

quashing the presentment and dismissing this cause.

Looby & Williams, By Z. Alexander Looby, Attorneys

for Defendants.

[File endorsement omitted]

[fol. 25]

In the Cbiminal Coubt of Davidson County, T ennessee

D ivision Two

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

Motion U ndeb A dvisement— January 10,1963

Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the State

and the defendants in person.

Thereupon this cause was heard by the court upon defen

dants’ motion to quash or dismiss the presentment in this

cause, upon the evidence introduced and after argument of

counsel for the State and the defendants, said motion was

by the court taken under advisement.

It is therefore considered by the court that this cause be

set upon the docket on January 14, 1963 for final disposition.

Mr. Z. Alexander Looby, Attorney for the defendants.

Mr. Harry G. Nichol, District Attorney General.

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morning

at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

8

[fol. 27]

I n the Criminal Court op Davidson County, T ennessee

D ivision T wo

N o. 15866

[Title omitted]

Order Overruling M otion to Quash P resentment—

January 15, 1963

Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the State

and the defendants in person.

Thereupon this cause was heard by the court upon defen

dants’ motion to quash or dismiss the presentment entered

against them, which motion was by the court taken under

advisement on January 10,1963.

It is therefore considered by the court that said motion

be overruled and that this cause be put upon the docket for

arraignment at a later date, to which action of the court

the defendants by their attorney made an exception.

Mr. Z. A. Looby, Attorney for the defendants.

Mr. Harry G. Nichol, District Attorney General.

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morning

nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

9

[fol. 28] [File endorsement omitted]

Isr the Criminal Court of Davidson County, Tennessee

D ivision T wo

[Title omitted]

Motion of D efendants to Quash P resentment, etc.—

Filed January 30, 1963

Come the defendants and move the Court to quash the

presentation heretofore returned against them or, in the

alternative, to require this State to make an election because

the presentment purports to charge the defendants with

violating Code Section 39-1101-(7) and Code Section 62-711,

all under and in the same count, same being bad for du

plicity.

Therefore, the defendants move the Court to quash their

indictment or in the alternative to require the State to

elect whether it will prosecute the defendants under Code

Section 39-1101-(7) or whether it will prosecute them under

Code Section 62-711.

Looby & Williams, By Z. Alexander Looby, Attorneys

for Defendants.

Certificate of Service (omitted in printing).

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morning

at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

10

[fol. 29] [File endorsement omitted]

I n the Criminal Court of Davidson County, T ennessee

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

Order Overruling M otion to Quash P resentment—

February 1, 1963

This cause came on to be heard upon the motion of the

defendants, heretofore filed in this cause, to quash the

presentment returned against them for the reason that the

presentment was duplicitous in that it charged the defen

dants with a conspiracy to violate two sections of the Code

in the same count of the presentment.

After hearing the matter and argument of counsel, both

for the State and for the defendant, and the presentation

of the law applicable, the Court is pleased to over-rule the

motion of the defendants by authority of Section 40-1818

of T.C.A. and the holding of our Supreme Court in the case

of State vs. Smith in Vol. 194 at Page 608.

To this action of the Court in over-ruling their motion to

quash the presentment, the defendants excepted.

This the 1st day of February, 1963.

John L. Draper, Judge.

11

[fol. 30]

I n the Criminal Court op Davidson County, T ennessee

D ivision T wo

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

Minute E ntry of A rraignment— P lea— February 1, 1963

Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the State

and the defendants in person, who being arraigned upon

said indictment plead not guilty to the same; thereupon

this cause was continued until a later date of the present

term of this court.

Mr. Z. Alexander Looby and Mr. Avon Williams, Attorneys

for the defendants.

Mr. Harry G. Nichol, District Attorney General for the

State.

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morning

at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

[fol. 31]

I n the Criminal Court of Davidson County, T ennessee

D ivision T wo

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

Minute E ntry—5 J urors Selected, Special V enire

Ordered; R espited— March 5, 1963

Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the State

and the defendants in person, who being arraigned upon

said indictment plead not guilty to the same and for their

trial put themselves upon the country and the Attorney

General doth the like.

12

Thereupon, the court proceeded to the impaneling of the

jury, when the following were duly and regularly elected

and impaneled, to wit: Howard C. Lewis, C. P. Holland,

Joe W. Slate, Harley C. Dean and William Eawls.

And it appearing to the court that the jury was incomplete

and the panel exhausted, it is ordered by the court that the

jury box be brought into open court as provided by law,

and that 100 names be drawn therefrom, as provided by

law, and that venire facias issue to the Sheriff of Davidson

County, Tennessee to summon said venire to appear before

the Judge of this court tomorrow morning at 9:00 o’clock

which has been done.

[fol. 32] Thereupon the 5 jurors heretofore impaneled and

elected were placed in charge of Mr. Dewey Norman, a

regular officer of this court, who was duly sworn as the

law directs to take charge of and wait upon said jury until

finally discharged by the court.

Mr. Z. Alexander Looby and Mr. Avon Williams, Attorneys

for the defendants.

Mr. Harry G. Nichol and Mr. Gale Robinson, Attorneys

Generals for the State.

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morning

at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

[fol. 33]

I n the Criminal Court of Davidson County, T ennessee

D ivision T wo

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

M inute E ntry— 3 J urors Selected, Special V enire

Ordered, R espited— March 6, 1963

Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the State

and the defendants in person, also the 5 jurors heretofore

impaneled in this cause who were on yesterday respited

from the further consideration of the cause on trial until

13

the meeting of court today, came here into open court in

charge of their sworn officer in whose charge they were

placed on yesterday.

Thereupon the court proceeded in the further impaneling

of the jury when the following were duly and regularly

elected and impaneled, to wit: 0. H. Glasgow, Herbert

Amic and Willie D. Swindle.

And it appearing to the court that the jury was incomplete

and the panel exhausted, it is ordered by the court that the

jury box be brought into open court as provided by law,

and that 100 names be drawn therefrom, as provided by law,

and that venire facias issue to the Sheriff of Davidson

County, Tennessee to summon said venire to appear before

the Judge of this court tomorrow morning at 9:00 o’clock,

which has been done.

[fol. 34] Thereupon the 8 jurors heretofore impaneled and

elected were placed in charge of Mr. Charles R. Hill, a

regular officer of this court, who was duly sworn as the law

directs to take charge of and wait upon said jury until

finally discharged by the court.

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morning

at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

[fol. 35]

l x the Criminal Court of Davidson County, T ennessee

D ivision T wo

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

Minute E ntry— Jury Complete, P ortion of P roof;

E espited— March 7, 1963

Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the State

and the defendants in person, also the 8 jurors heretofore

impaneled in this cause, who were on yesterday respited

from the further consideration of the cause on trial until

the meeting of court today, came here into open court in

charge of their sworn officer, in whose charge they were

14

placed on yesterday. And the court proceeded to complete

the impaneling of the jury when the following were duly

and regularly elected and impaneled, to wit: William T.

Moon, Charles H. Williams, H. J. Farnsworth and Wendell

H. Cooper.

It then appearing to the court that the jury was complete,

the jury was duly sworn to well and truly try the issues

joined, and true deliverance make according to the law and

evidence and after hearing a portion of the proof and there

not being time on today to conclude the trial the jury was

[fol. 36] respited from the further consideration of the

cause on trial until the meeting of court tomorrow morning

at 9:00 o’clock, and the jury was placed in charge of Mr.

Paul Startup, a regular officer of this court, who was duly

sworn as the law directs to take charge of and wait upon

said jury until finally discharged by the court.

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morning

at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

[fol. 37]

In the Criminal Cottkt op Davidson County, T ennessee

D ivision Two

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

M inute E ntry— P oetion op P roof, R espited—

March 8, 1963

Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the State

and the defendants in person, also the jury heretofore

impaneled in this cause who were on yesterday respited

from the further consideration of the cause on trial until

the meeting of court today, came here into open court in

charge of their sworn officer in whose charge they were

placed on yesterday, and renewed their consideration of

the cause on trial and they having heard the further por

tion of the proof and there not being time on today to

conclude the trial the jury was again respited from the

further consideration of the cause on trial until tomorrow

15

morning at 9 :00 o’clock and the jury was placed in charge

of Mr. John Ed Polk, a regular officer of this court who

was duly sworn as required by law, to take charge of and

wait upon said jury until finally discharged by the court.

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morning

at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

[fol. 38]

I n the Criminal Court op Davidson County, Tennessee

D ivision T wo

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

V erdict—March 9, 1963

Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the State

and the defendants in person, also the jury heretofore

impaneled in this cause who were on yesterday respited

from the further consideration of the cause on trial until

the meeting of court today, came here into open court and

renewed the consideration of the cause on trial, and they

having heard the remainder of the proof, argument of coun

sel and charge of the court, aforesaid, upon their oath afore

said, do say: That they find the defendants guilty of

unlawful conspiracy.

Thereupon the jury was discharged.

It is therefore considered by the court that the judgment of

the court be reserved until a later date.

Mr. Z. Alexander Looby and Mr. Avon Williams, Attorneys

for the defendants.

Mr. Harry G. Nichol and Mr. Gale Robinson, District At

torney Generals for the State.

Ordered that court stand adjourned until Monday morning

at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

16

[fol. 39]

I n the Criminal Court oe Davidson County, T ennessee

D ivision T wo

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

J udgment—March 19, 1963

Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the State

and the defendants in person.

Heretofore, the defendants Lester G. McKinnie, John R.

Lewis, Frederick Leonard, John Jackson, Jr., Nathal Win

ter, Frederick Hargraves, Harrison Dean and Allen Cason,

Jr., were found guilty of conspiracy to violate Section

39-1101-(7) of the Code in this cause by a jury on Saturday,

March 9, 1963, and the judgment of the court was reserved

until this date, at which time the verdict of the jury was

made the judgment of the court.

It is, therefore, considered by the court that the defendants,

Lester G. McKinnie, John R. Lewis, Frederick Leonard,

John Jackson, Jr., Nathal Winter, Frederick Hargraves,

Harrison Dean and Allen Cason, Jr., for their offenses of

a conspiracy to violate Code Section 39-1101-(7) shall pay a

fine of $50.00 each together with the costs of this prosecution

[fol. 40] and each defendant shall be confined in the County

workhouse for a period of 90 days commencing on the date

of their delivery to the keeper thereof, subject to the rules

and regulations of said Institution.

That they pay the costs of this prosecution or that they, by

their labor, pay the same at the rates of labor allowed by

law, subject to the rules and regulations of said Institution.

Thereupon the defendants by their attorney gave notice

to the court of a motion for a new trial and said attorney

is allowed 30 days within which time to prepare and file said

motion.

Mr. Avon Williams and Mr. Z. Alexander Looby, Attorneys

for the defendants.

Mr. Harry G. Nichol and Mr. Gale Robinson, Attorneys

General for the State.

17

(Charge of the Court Copied in Bill of Exceptions)

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morning

at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

[fol. 41]

I n the Criminal Court of Davidson County, T ennessee

D ivision T wo

N o. 15866

[Title omitted]

Motion for New T rial—Filed April 18, 1963

Come the defendants, Lester G. McKinnie, John R. Lewis,

Frederick Leonard, John Jackson, Jr,, Nathal Winter, Fred

erick Hargraves, Harrison Dean, and Allen Cason, Jr., and

move the Court thereon in the above entitled cause, and

to grant them a new trial upon the following grounds:

1. The Court erred in overruling the individual motions

filed by each of said defendants on 17 December 1962 for

an order remanding the cause to the Court of General Ses

sions to be acted upon by a Judge of said Court.

2. The Court erred in overruling defendants’ motion filed

on 18 January 1962 for an order quashing the presentment

and dismissing the cause on the grounds stated therein.

3. The Court erred in overruling defendants’ motion field

on 30 January 1962 to quash the presentment or, in the al

ternative, to require the State to make an election as to

which of the State statutes alleged in the indictment it

would prosecute the defendants under.

4. The satutes under which defendants were arrested,

charged in the presentment, tried and convicted, are un

constitutional on their face by purporting to make it a

crime to conspire “ to commit any act injurious to public

health, public morals, trade, or commerce” (T. C. A. Section

39-1107(7)), or to be guilty of “ turbulent or riotous con-

[fol. 42] duct within or about any hotel, inn, theater, or

18

public house, common carrier, or restaurant” (T.C.A. Sec

tion 62-711), in that said statutes do not define the type of

conduct therein prohibited with sufficient particularity to

apprise defendants or give them warning of the offense al

leged, nor do said statutes contain sufficient standards of

guilt or definition of the offenses created thereby upon which

judicial determination of guilt could be made, all of which

renders said statutes so vague, indefinite and uncertain as

applied to defendants and the evidence offered against them

in this case as to violate their rights under the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

5. That one of the statutes charged in the presentment

and upon which defendants were convicted (T.C.A. Section

62-710), is not and does not purport on its face to be a

criminal statute, and the criminal conviction of the defen

dants for an alleged violation of this statute violates their

rights secured by the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

6. The Court erred in charging the jury as follows:

“ Section 62-710 of the Code of Tennessee provides as

follows: The rule of the common law giving the right

of action to any person excluded from any hotel or

public means of transportation or place of amusement

is abrogated, and no keeper of any hotel or public

house or carrier of passengers for hire except railway,

street, interurban and commercial, or conductors,

drivers or employees of such carrier, or keeper, shall

be bound or under any obligation to entertain, carry,

or admit any person whom he shall, for any reason

whatever, choose not to entertain, carry or admit to

his house, hotel, vehicle, or means of transportation

or place of amusement, nor shall any right exist in favor

of any such person so refused admission. The right of

such keepers of hotels and public houses, carriers of

passengers and keepers of places of amusement and

their employees to control the access and admission or

exclusion of persons to or from their public houses,

means of transportation, and places of amusement, to

19

be as complete as that of any private person, private

house, vehicle, or private theater, or places of amuse

ment for his family . . .

[fol. 43]

* * m # # # *

You will note from the language of the presentment

that the defendants are charged with the offense of

unlawful conspiracy to violate Code Section 39-1101-

(7), Code Section 62-710 and Section 62-711, in that

they did unlawfully commit acts injurious to the res

taurant business, trade and commerce of Burrus and

Webber, Cafeteria, Inc., a corporation located at 223

—uh, 226 Sixth Avenue, North, Nashville, Davidson

County, Tennessee . . .

* # * # # # #

. . . if you find and believe, beyond a reasonable doubt,

that the said defendants unlawfully, willfully, know

ingly, deliberately and intentionally did unite, combine,

conspire, agree and confederate between and among

themselves to violate Tennessee Code Sction 39-1101-

(7) and Code Sections 62-710 and 62-711, and unlaw

fully to commit acts injurious to the restaurant busi

ness, trade and commerce of the Burrus and Webber

Cafeteria, Inc., a corporation located at 226 Sixth Ave

nue, Nashville, Davidson County, as charged in this

presentment, then it will be your duty to convict the

defendants, provided that they, or one of them, did in

pursuance of said agreement, or conspiracy, do some

overt act to effect the object of the agreement, that is,

if you find that said agreements and acts in the further

ance of said objective was done in Davidson County,

Tennessee . . . ”

This was error because said Code Section 62-710 was not

included in the presentment does not create or purport to

create any criminal offense and the criminal charge, trial

and conviction of defendants thereunder upon said charge

of the Court violates their rights secured by the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution.

20

7. T. C. A. Sections 39-1101(7), 62-710 and 62-711, are

nnconstitntional and void on their face as applied to the

defendants on the presentment and evidence in this case

in that said statutes are being applied as state law author

izing and enforcing a rule, custom and practice of racial

segregation or discrimination in facilities licensed by the

State, open to the public, and invested with a public interest,

thereby violating rights of the defendants secured by the

due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

8. The arrest, trial and conviction of the defendants

upon the presentment, evidence and the charge of the Court

[fol. 44] in this case was expressly predicated upon, and

for the sole purpose of, enforcing a private rule, practice

or custom of racial segregation for the benefit of the Burrus

and Webber Cafeteria, Inc., which actions of state execu

tive and judicial officers and agencies and the resulting

convictions of defendants are unconstitutional and void as

violating rights of defendants secured by the due process

and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution.

9. The Court erred in denying that portion of Defen

dants’ Special Request No. 1 for Instructions to the Jury,

which was as follows:

“Evidence that the defendants agreed to seek entry,

or that they went to the premises and sought entry, to

the B&W Cafeteria for the purpose of being served

food, could not constitute such an unlawful agreement

or overt act in pursuance thereof even though the de

fendants were Negroes and the B&W Cafeteria had a

policy of refusing to serve food to Negroes, for . . . ”

10. The Court erred in denying Defendants’ Special Re

quest No. 2 for Instructions to the Jury, which was, in

words and figures, as follows:

“ Defendants’ Special R equest No. 2

eoe Instructions to the J ury

If you should find from the evidence that the defen

dants went to the B&W Cafeteria, a place of business

21

offering meals to the general public, and sought to enter

there for the purpose of purchasing and being served

meals, and that said Cafeteria or its agents blocked

their entry in pursuance of an for the purpose of en

forcing, a rule of the Cafeteria to serve only white

persons and not to serve Negroes, and that the defen

dants remained standing in a peaceable manner where

they were when the Cafeteria blocked their entrance,

either for the purpose of still seeking admission to

the Cafeteria, or for the purpose of peaceably protest

ing the Cafeteria’s policy of racial exclusion or segre

gation, then you could not find the defendants guilty

of committing any unlawful act, nor could you find

defendants guilty of a conspiracy or agreement to com

mit any unlawful act under this evidence, and this is

true even though you also find from the evidence that

it was necessary for some white patrons to pass through

or around the defendants in order to gain ingress or

[fol. 45] egress to or from the Cafeteria or that some

prospective white patrons may have been reluctant or

may have refused, to enter, stay in, or come out of

the restaurant because of the defendants’ presence

there.”

11. The Court erred in denying Defendants’ Special Re

quest No. 3 for Instructions to the Jury, which was, in

words and figures, as follows:

“ Defendants’ Special R equest No. 3

FOB INSTBUCTIONS TO THE JUBY

You will not consider or bring in any verdict as to

that portion of the presentment which charges a con

spiracy by defendants to violate Code Section 62-711,

for the reason that the State has abandoned this por

tion of the charge, and has offered no evidence in sup

port thereof.”

12. The Court erred in denying Defendants’ Special Re

quest No. 4 for Instructions to the Jury, which was, in

words and figures, as follows:

22

“ Dependants’ Special R equest N o. 4

Poe I nstructions to the J ury

Notwithstanding T. C. A. Code Section 62-710, or

any statute or other law of the State of Tennessee,

the B&W Cafeteria, or its proprietors, have no legal

right to exclude persons from said business, offering

food service and meals to the general public, solely on

account of the race or color of the persons so excluded,

or to enforce or have enforced, any private rule or

policy of racial segregation or exclusion through crim

inal action in a Court of the State of Tennessee; for

any State law which attempts or attempted to estab

lish such a legal right, and any action of State agencies,

including the Courts thereof, in enforcing, directly or

indirectly such a private rule or policy, would be and

is unconstitutional and void as depriving the defen

dants in this case of the equal protection of the laws

and of due process of law as secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.”

13. The evidence offered against defendants, all Negroes,

in support of the presentment charging them with con

spiracy to violate Code Section 39-1101-(7) and Code Sec

tion 62-711, establishes that they and each of them were

at the time of arrest and at all times covered by the

[fol. 46] charge or presentment, in peaceful exercise of con

stitutional rights to assemble with others for the purpose

of speaking and protesting against the practice, custom,

usage and rule of racial discrimination in Burrus and

Webber Cafeteria, 226 Sixth Avenue, North, Nashville,

Tennessee, an establishment performing an economic func

tion invested with the public interest; that defendants peace

fully were attempting to obtain service in the facilities of

said Cafeteria in the manner of white persons similarly

situated, and at no time were defendants or any of them

defiant, in breach of the peace, or guilty of any turbulent

or riotous conduct or acts injurious to trade or commerce,

and were at all times upon an area essentially public, where

fore defendants, by their arrest, trial and conviction under

said State statutes and through action of state officers and

23

the state court have been denied rights secured by the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

14. The evidence establishes that prosecution of defen

dants was procured for the purpose of preventing them

from engaging in peaceful assembly with others for the

purpose of speaking and otherwise peacefully protesting

in public places the refusal of the preponderant number of

restaurants, facilities and accommodations open to the

public in Nashville, Tennessee, to permit the defendants,

all Negroes, and other members of defendants’ race from

enjoying the access to such restaurants, facilities and ac

commodations afforded members of other races; and that

by this prosecution and conviction of defendants, the prose

cuting witnesses, arresting officers and State District At

torney General have employed the aid of state officials and

of the Court to enforce a racially discriminatory policy

contrary to the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

[fol. 47] United States.

15. The defendants, all Negroes, were tried and con

victed by a jury composed entirely of white persons in

the City of Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee, an area

in which racial segregation has been imposed by state law

in virtually all aspects of public life for many years, and

which is still the public and private custom and practice

of nearly all white people in said area. The express and

sole purpose of the presentment and trial of defendants in

this case was to enforce through state action a private rule

and practice of racial discrimination against defendants and

all other Negroes, maintained by Burrus and Webber Cafe

teria, a restaurant open to the general public in Nashville,

Tennessee. The State’s Attorney deliberately and sys

tematically challenged and excused all Negro veniremen

who were called as prospective jurors. All white veniremen

who were called and accepted by the State admitted their

personal practice, custom, philosophy and belief in com

plete racial segregation in virtually all aspects of their

social existence. It was therefore impossible for defendants

to secure a fair and impartial jury of their peers on the

24

presentment in this case, and they were thereby deprived

of their rights secured by Article 1, Section 9 of the Con

stitution of Tennessee and by the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution.

16. The Court erred in holding that jurors Wm. T. Moon

and Wendell H. Cooper were competent, and in requiring

defendants to accept said jurors over protest, the defen

dants having exhausted all of their challenges, because

all of these jurors admitted their personal practice, cus

tom, philosophy, indoctrination and belief in complete racial

segregation and discrimination against Negroes, as being

a group inferior to white persons, in virtually all aspects

[fol. 48] of their social existence. The sole and express

purpose of the presentment and trial of defendants in this

case was to enforce through state executive and judicial

action just such a private rule and practice of racial dis

crimination against defendants and all other Negroes, main

tained by Burrus and Webber Cafeteria, a restaurant open

to the general public in Nashville, Tennessee, as to which

all of said jurors, being white persons, admitted their said

personal indoctrination, custom, prejudice and belief. The

State’s Attorney deliberately and systematically challenged

and excused all Negro veniremen who were called as pro

spective jurors. Defendants were thereby deprived of their

rights to a fair and impartial jury of their peers, in vio

lation of Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution of Ten

nessee and in violation of the due process and equal pro

tection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution. The Court overruled defendants’ mo

tions that said jurors be disqualified for cause upon the

foregoing grounds, to which action defendants excepted.

17. The Court erred in holding that the juror, Herbert

Amic, was competent, and in requiring defendants to accept

said juror and seating said juror over protest, because he

admitted that he would start out in the case with a preju

diced attitude toward the defendants where the presentment

alleged or the proof showed that they went to the Burrus

and Webber Cafeteria and sought to be served knowing

that the cafeteria had a rule discriminating against Negro

25

patrons, and he admitted his personal belief, opinion and

prejudice in favor of such a rule. The Court overruled

defendants motion that said juror be disqualified for cause

upon the foregoing ground, to which action defendants ex

cepted. Defendants were thereby deprived of their rights

to a fair and impartial jury of their peers, in violation of

Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution of Tennessee and

in violation of the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

[fol. 49] United States.

18. There was no evidence upon which the jury could

find the defendants guilty of the offense charged in the

presentment.

19. All of the evidence preponderated in favor of the

innocence and against the guilt of defendants of the offense

charged in the presentment.

20. The judgment of the Court fixing the punishment of

defendants in words and figures as follows:

“ O R D E R

“ Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the

State and the defendants in person.

Heretofore, the defendants, Lester G. McKinnie,

John R. Lewis, Frederick Leonard, John Jackson, Jr.,

Nathal Winter, Frederick Hargraves, Harrison Dean,

and Allen Cason, Jr., were found guilty of conspiracy

to violate Section 39-1101-(7) of the Code in this cause

by a jury on Saturday, March 9, 1963, and the judg

ment of the Court was reserved until this date, at which

time, the verdict of the jury was made the judgment of

the Court.

It is, therefore, considered by the Court that the

defendants, Lester G. McKinnie, John R. Lewis, Fred

erick Leonard, John Jackson, Jr., Nathal Winter,

Frederick Hargraves, Harrison Dean, and Allen Cason,

Jr., for their offenses of a conspiracy to violate Code

Section 39-1101-(7) shall pay a fine of $50.00 each

together with the costs of this prosecution and each

defendant shall be confined in the County Workhouse

26

for a period of 90 days commencing on the date of their

delivery to the keeper thereof, subject to the rules and

regulations of said institution.

That they pay the costs of this prosecution or that

they, by their labor, pay the same at the rates of labor

allowed by law subject to the rules and regulations

of said institution. Thereupon, the defendants, by their

attorney, gave notice to the Court of a motion for a

new trial and said attorney is allowed 30 days within

which time to prepare and file said motion.

This the 19th day of March, 1962.

/ s / John L. Draper

John L. Draper, Judge”

is contrary to the verdict of the jury, which was in words

and figures as follows:

The Court: The Jury is all present. Gentlemen of the

jury have you agreed upon a verdict?

Foreman: We have.

The Court: What is it?

Foreman: We agreed your Honor, on a fine less than

$50, so we find the defendants guilty.”

[fol. 50] Said judgment of the Court therefore deprives

defendants of rights secured by the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

Wherefore, the defendants move the Court to set aside

and vacate the verdict of the jury and the judgment thereon

and grant them a new trial.

Looby & Williams, By Z. Alexander Looby, Solicitors

for Defendants.

Proof of service (omitted in printing).

[File endorsement omitted]

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morning

at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

27

[fol. 53]

I n the Criminal Court op Davidson County, Tennessee

D ivision T wo

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

Unlawful Conspiracy

Order Overruling Motion— May 10,1963

Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the State

and the defendants in person.

Thereupon this cause was heard by the court on May 3,

1963, upon defendants’ motion to be granted a new trial,

which was by the court taken under advisement until this

date, on which date said motion was by the court overruled.

It is therefore considered by the court that the defendants

Lester G. McKinnie, John K. Lewis, Frederick Leonard,

John Jackson, Jr., Nathal Winter, Frederick Hargraves,

Harrison Dean and Allen Cason, Jr., for their offenses of a

conspiracy to violate Code Section 39-1101-(7) shall pay a

fine of $50.00 each together with the costs of this prosecu

tion and each defendant shall be confined in the County

Workhouse for a period of 90 days commencing on the date

[fol. 54] of their delivery to the keeper thereof, subject to

the rules and regulations of said Institution.

That they pay the costs of this prosecution or that they by

their labor pay the same at the rates of labor allowed by

law, subject to the rules and regulations of said Institu

tion. To the judgment and ruling of the court in overruling

defendants’ motion for a new trial, the defendants except

and pray an appeal in the nature of a writ of error to the

next term of the Supreme Court sitting at Nashville, which

is by the court granted and the defendants are allowed 30

days from this date within which time to prepare and file

their Bill of Exceptions.

Mr. Z. A. Looby and Mr. Avon Williams, Attorneys for the

defendants.

28

Mr. John K. Maddin, Special Prosecutor for the State.

Mr. Harry G. Nichol, District Attorney General for the

State.

Mr. Gale Robinson, Assistant Attorney General for the

State.

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morn

ing at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

# # # # # # #

[fol. 63]

In the Criminal Court of Davidson County, Tennessee

D ivision Two

No. 15866

[Title omitted]

B ill of E xceptions F iled—May 31,1963

Came the Attorney General who prosecutes for the State

and the defendants in person, who by their attorneys tender

this their bill of exceptions to the judgment of the court in

overruling defendants’ motion for a new trial, which was

by the court signed, sealed and ordered made a part of the

record.

Ordered that court stand adjourned until tomorrow morn

ing at nine o’clock.

John L. Draper, Judge.

[fol. 64] Clerk’s Certificate to foregoing transcript

(omitted in printing).

29

[fol. 1] [File endorsement omitted]

I n' the Criminal Court of Davidson County, T ennessee

D ivision T wo

No. 15866

In tlie Matter of:

State of T ennessee,

v.

Lester Gr. McK innie, J ohn E. Lewis, F rederick L eonard,

John J ackson, J r,, Nathal W inters, F rederick H ar

graves, H arrison D ean, and A llen Cason, J r,

D efendants B il l of E xceptions

including

Voir dire

Before: Hon. John L. Draper, Judge and A Jury.

A p p e a r a n c e s :

For the State:

Harry Nichol, Dale Robinson, Howard F. Butler.

For the B&W Cafeteria:

Jack Maddin.

For the Defendants:

Z. Alexander Looby, Avon Williams, Jr.

[fol. 2]

* # # # # # #

The above-styled cause came on for trial before Hon.

John L. Draper, Judge, and a Jury on March 5, 1963,

in the Criminal Court of Davidson County, Tennessee, Part

II, when the following proceedings were had, to-wit:

* = * # # # # #

30

Colloquy

The Court: All right, gentlemen, we are ready to begin

picking a jury.

Mr. Looby: If your Honor please, the Defendants re

spectfully request the privilege of waiving the jury and

want to be tried by the Court, without a jury.

Mr. Nichol: If your Honor please, the State will insist

upon a jury. If the state waives the jury, any fine to be

assessed by the Court alone is limited to $50. The statute

says in cases of this kind for a jury to assess as high as

$1,000.

Mr. Looby: If your Honor please, I object to the At

torney General making a speech now. This is no time to

make a speech about waiving the jurors. This is no time

to make a speech.

Mr. Nichol: I am saying we do not want to waive a jury.

Mr. Looby: I am addressing the Court.

The Court: General, does the State—

Mr. Nichol: We decline to waive the jury.

The Court: All right. Then the case will be tried before

the jury. This will settle it.

[fol. 3] Mr. Looby: If the Court please, we respectfully

except to the Court’s ruling.

The Court: All right. Call in a prospective juror.

Mr. Looby: If the Court please, we want to call them

as individuals, and then have individual examination.

The Court: I said a prospective juror.

(A. L. D ickerson is brought in to be examined) (sworn

by clerk).

Criminal Court Clerk: Have you formed or expressed

an opinion as to the guilt or innocence of the Defendants,

Lester G. McKinnie, John R. Lewis, Frederick Leonard,

John Jackson, Jr., Nathal Winters, Frederick Hargraves,

Harrison Dean and Allen Cason, Jr., who are charged with

violating Code §39-1101, unlawful conspiracy?

A. No.

The Court: He is competent.

Mr. Nichol: Mr. Dickerson, do you know any of these

Defendants here?

31

A. No, sir.

Q. The charge here is that they violated Code Section

§39-1101-7. It charges that they unlawfully conspired to

obstruct trade and commerce of the business of the B&W

Cafeteria. Do you know any of the facts of that case?

A. No, sir.

Q. I will ask you if you go into that jury box, is there

any reason why you cannot apply to the facts the law of

Tennessee as given you by the Court in this case ? Is there

[fol. 4] any reason or conscientious scruples against the

present laws of Tennessee on this subject?

A. (Hesitates.)

The Court: Do you understand his question?

A. No, sir. I did not.

Mr. Nichol: In other words, what has been your business

over the years, Mr. Dickerson?

A. Pardon?

Q. What’s been your business over the years?

A. Bowling alley business.

Q. What?

A. Bowling alley business.

Q. Do you own a bowling alley, or where is it located?

A. 8th and Church.

Q. 8th and Church? Is there any reason in the world

why you can’t—that you know, that you can’t hear the

evidence in the courtroom and apply to that the law of Ten

nessee, as given to you by the Court, and give both the

State and the Defendants a fair and impartial trial?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. We accept Mr. Dickerson.

Mr. Looby: Mr. Dickerson, you say you operated a bowl

ing alley at 8th and Church?

A. Yes, sir.

[fol. 5] Q. And it was open to the public, was it?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Open to anybody regardless of their race?

A. No.

Q. You were segregated?

A. You could say so.

Q. Well, did it exclude Negroes?

32

A. Pardon?

Q. Did you exclude Negroes?

A. Yes, sir.

Q, That is the case that is involved here. This is a case

involving the exclusion of Negroes. Could you give these

men in this case a full and fair and impartial trial?

A. I think so.

Q. If you have a place open to the public and they

should come there and attempt to come in, would you con

sider it an obstruction of your trade and commerce?

A. The place is not there any more.

Q. Sir?

A. The place is not there any more, it has been sold and

moved out.

Q. But if they came there, would you consider it an

obstruction of trade and commerce?

A. Yes.

Q. And, feeling the way you do, do you think you could

give these men a fair and impartial trial, based on your

[fol. 6] opposition?

A. I think so.

Q. I think this juror shows prejudice and bias, and we

should pass him because of the very questions he’s de

cided.

The Court: Well, he answered to the contrary, Gentle

men, and the Court can’t search a juror apart.

Mr. Looby: But he says, if your Honor please, he is

not operating any business, but he objected to that in a

business. And that’s all this case is about.

Juror: I would have to object, or close up.

Mr. Looby: Sir?

Juror: I would have to object, or close up.

Q. And you would object?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. You would have to object?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you would have to close if you didn’t?

A. I would be forced to close if I let him come in at that

time.

33

Q. And this case is about—this case is about the B & W

Cafeteria, and they went to the B & W Cafeteria, and

went in for service, and were arrested because of that,

solely because of their race. Don’t you think you would be

somewhat prejudiced against them?

A. Do I think what?

[fob 7] Q. Don’t you think you would be prejudiced

against them?

A. I don’t know.

The Court: You just say you don’t know. I think he is

entitled to an answer on that.

A. I don’t know what the circumstances are in this case.

Mr. Looby: They have the policy, they say, of serving

only white people, and of not serving Negroes, and they

are supposed to serve only white people. Do you feel

that—if they have the policy of serving only whites, that

if Negroes went in there to be served, that that would con

stitute an offense and you would convict them?

A. I don’t know. I can’t answer that.

Mr. Looby: May it please your Honor, I think that with

the attitude he has toward these things that he couldn’t

give a fair and impartial verdict in this case.

The Court: You told the counsel for the Defendants that

you could give them a full, fair and impartial trial a while

ago?

A. I think so.

By the Court:

Q. Can you stand by that, sir?

A. I think so.

By the Court:

Q. Well, do you know so?

A. No, I don’t know so. I think I can, I can be fair.

[fob 8] The Court: That’s all that’s required for you to

be fair to the state and to the defendants. And if you are

going to do that, sir, I think you are a competent juror. If

you are not, then you are not competent.

34

A. Well, I think I could be fair. That’s all I can say.

The Court: Gentlemen, that makes him competent.

Mr. Looby: Mr. Dickerson, do you understand the nature

of this case?

A. Slightly.

Q. Well, then, I will try to explain it and if I don’t,

the Judge will stop me. The B & W operates a restaurant

here, and they have a policy not to serve Negroes. Any

white man can go in there and get served, no matter who he

is, or what he looks like. But if he is a member of the

Negro race, he is not allowed.

These boys are all Negroes, and they went there seeking

service. And that is the only offense that is named—

they are charged here with attempting to obstruct trade.

Now, with these facts, and readily realizing that you

operated a bowling place here where you said you had a

policy not to allow Negroes, and abiding by that policy, do

you think you could give them a fair and impartial trial?

Honestly?

A. I think so.

Q. You really do? Is that your honest conviction?

[fol. 9] A. I think I could.

Q. What do you understand a fair and impartial trial

to mean ?

A. Pardon?

Q. What do you understand a fair and impartial trial

to mean ?

A. What did he say?

The Court: (Bepeats what Mr. Looby has just asked.)

He said what do you understand a fair and impartial trial to

mean?

A. Just the facts in the case.

Mr. Looby: And you think that if they had a policy not

to serve Negroes, you think—you wouldn’t think they were

wrong, would you?

A. I couldn’t say I do. I don’t know.

Mr. Nichol: Your Honor, they are asking him to pass on

the facts before they are heard. He is examining the wit

ness—

35

Mr. Looby: I ’m not examining the witness—

The Court: Yeah, Mr. Dickerson, did yon understand

him?

A. No, sir.

The Court: Repeat the question.

Mr. Looby: Do you really consider that this place, hav

ing a known policy to serve only white people, and not to

serve Negroes,—that was their policy—and the fact that

the Negroes went in there and demanded service—that they

were wrong to do that ?

Mr. Nichol: I make an objection to that, if your Honor

[fol. 10] please.

The Court: Yes. I sustain your objection, General.

Mr. Nichol: That would be voir dire—to place the—

The Court: No, no, no, you made an objection. I sustain

it. I think that will be part of his lawsuit.

Mr. Williams: Respectfully except, if your Honor please.

Mr. Looby: Do you think operating a business—do you

think a group of Negroes coming in and demanding service

•—do you think that would affect your judgment here? That

it would be obstructing trade?

Mr. Nichol: I object to that.

The Court: I sustain that, General. That calls for him to

decide the lawsuit.

Mr. Looby: Mr. Dickerson, do you think or believe that

in a public place since you are in Nashville, and in the

United States of America, that citizens of the United States,

regardless of their race, have a right to equal treament?

Mr. Nichol: If your Honor please, we object to that. It

is a matter of law.

Mr. Looby: If your Honor please, it is not just a matter

of law in this case. It is a matter of the law and the facts.

The Court: Well, I ’ll let him answer that, General, I

believe.

A. I can’t understand the gentleman. Will you repeat

the last question?

[fol. 11] Mr. Looby: Will your Honor tell him what I said.

The Court: I think he asked you—I am not sure that

I can state it exactly right—I think he asked you whether

36

or not you thought, under the law, Negroes and whites had

equal rights in Nashville, and United States of America.

A. That depends.

Mr. Looby: On what does that depend, Mr. Dickerson?

Mr. Nichol: I just want to state an exception. You are

asking the witness questions based on identical cases or

maybe of slightly varying degrees. You are now asking

him to pass on other cases. You said public places. That

is not involved in this here. It’s private.

Mr. Looby: I asked him no such question. You said that

depends, Mr. Dickerson—it depends on what?

A. Depends on what the case dwindles down to. I am

not sure. I haven’t heard the case—and I’m not sure what

it’s all about. I ’ve an idea.

Q. The question is whether or not in a place of public

accommodation, whether any American citizen is entitled

to equal rights regardless of race.

Mr. Nichol: Your Honor, he is asking him to pass on

the law—not fact.

The Court: Gentlemen, I believe I will have to sustain

the state’s objection on that.

Mr. Looby: But I understood you to say that in operat-

[fol. 12] ing a bowling alley, in Nashville, for the public,

you maintained a policy of excluding Negroes and that you

didn’t believe that they had an equal right to be served

there ? Is that what you said?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you say that? Now, I want you to talk so the

Court can hear you. Don’t shake your head. Say yes, or no.

A. (To reporter.) What did he say?

(Reporter repeats what Mr. Looby said.)

A. I can’t understand him.

(Reporter repeats again.)

A. I can’t understand him.

The Court: Well, repeat the question.

37

Mr. Looby: I understood you to say that in operating

a bowling alley for public accommodation you maintained

a policy to exclude Negroes and that is your policy?

A. Yes.

Q. It is?

A. That’s right.

Q. And that is your policy, and that is still your feeling

about it?

A. Yes.

Q. It is?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you think in spite of your feeling, Mr. Dicker-

son, about that situation, you think a question involving

[fol. 13] the same principle,—you think you could pass

on a fair and impartial verdict for the Defendants, these

Negroes?

A. I don’t know.

Q. As a matter of fact, you just couldn’t?

A. I can’t say yes or no right now.

Q. You have a doubt in your mind?

A. It depends on the circumstances.

Q. You have a doubt in your mind about it, don’t you?

A. Why, yes, naturally. I don’t understand the case.

Q. Yes, sir.

The Court: Are you saying, sir, that after you heard

all the proof, after you heard all the charge of the Court,

you still could not give these Defendants a fair and im

partial trial because of your former policy? Your former

technique? Your former opinion?

A. Well—

The Court: Is that what you are telling Counsel?

A. Well, it’s the policy that I had.

The Court: And the feeling that you had?

A. (Hesitates.) I can’t—I can’t say.

The Court: You can’t say now that you could give them

a fair and impartial trial ?

A. I think I can give them a fair and impartial—

38

The Court: Trial!

[fol. 14] A. Yes, sir.

The Court: That’s all we ask you, sir, if you think

you can give the Defendants, in spite of the questions

that have been asked, and in spite of your former policy and

business?

A. I think so.

By the Court:

Q. You still thing you can give the Defendants a fair

and impartial trial ?

A. I think I can.

The Court: Gentlemen, that makes—again, I repeat,

that makes him competent, it appears to me.

Mr. Williams: May it please the Court, we respectfully

except. This witness has unequivocably in response to a

question as to whether or not in the light of his feeling

he can give these Defendants a fair and impartial trial,

he has said, “ I don’t know. I have doubts.” Now, we re

spectfully except to the Court denying our challenge for

cause, on the basis of the Court’s then asking him over

again, whether he can give them a fair and impartial

trial. I think that what he means is that he can sit up there

and listen. And that he just considers a fair and impartial

trial in words. But it’s going to be doubtful the substance

of it. His answer was that he didn’t know, that he had

serious doubts, and we feel that, under those circumstances,

that we are entitled to a challenge for cause, and we re

spectfully except, if your Honor please. We respectfully

except to the action of the Court.

The Court: All right. I overrule your application for

challenge for cause.

[fol. 15] Mr. Williams: May it please the Court, as I

understand the statute, each Defendant is entitled to three

pre-emptory challenges, is that right?

The Court: That’s right.

Mr. Williams: Is that correct, sir, so—

The Court: That’s the way I understand it.

39

Mr. Williams: That would be a total of 24 challenges ?

The Court: Eight.

Mr. Looby: We want the record to show, your Honor,

that with most—with the utmost reluctance, we challenge

pre-emptorily and we are now using, the record will show,

one of our pre-emptory challenges in this instance when we

are entitled to a challenge for cause, so if it becomes neces

sary to use all of our pre-emptory challenges, let it be

considered an error.

The Court: All right. Let the—you do exercise pre-

emptory challenge?

Mr. Looby: Yes, sir.

The Court: You will be excused, Mr. Dickerson. Now,

Gentlemen, for the Defendants, in order to keep abreast of

what we are doing, you ought to exercise it for some par

ticular Defendant, and tell the Clerk.

Mr. Nichol: Which Defendant?

Mr. Williams: Lester G. McKinnie is charged.

The Court: All right.

[fol. 27] (J ames L. E therly is called to the witness stand

as a prospective juror.)

(He is sworn and examined by the Clerk of the Criminal

Court.)

The Court: Competent.

Mr. Nichol: You say you know none of the Defendants?

A. James L. Etherly.

[fol. 28] Q. We excuse him.

Mr. Williams: We would like for the record to show that

this prospective juror was challenged and excused—the first

Negro that has been called, and he was excused pre-

emptorily by the State, without even an examination.

Mr. Nichol: Pre-emptory challenge.

#

40

[fol. 199] (T homas Bbown is called as a prospective juror,

sworn by the clerk and examined by the clerk.)