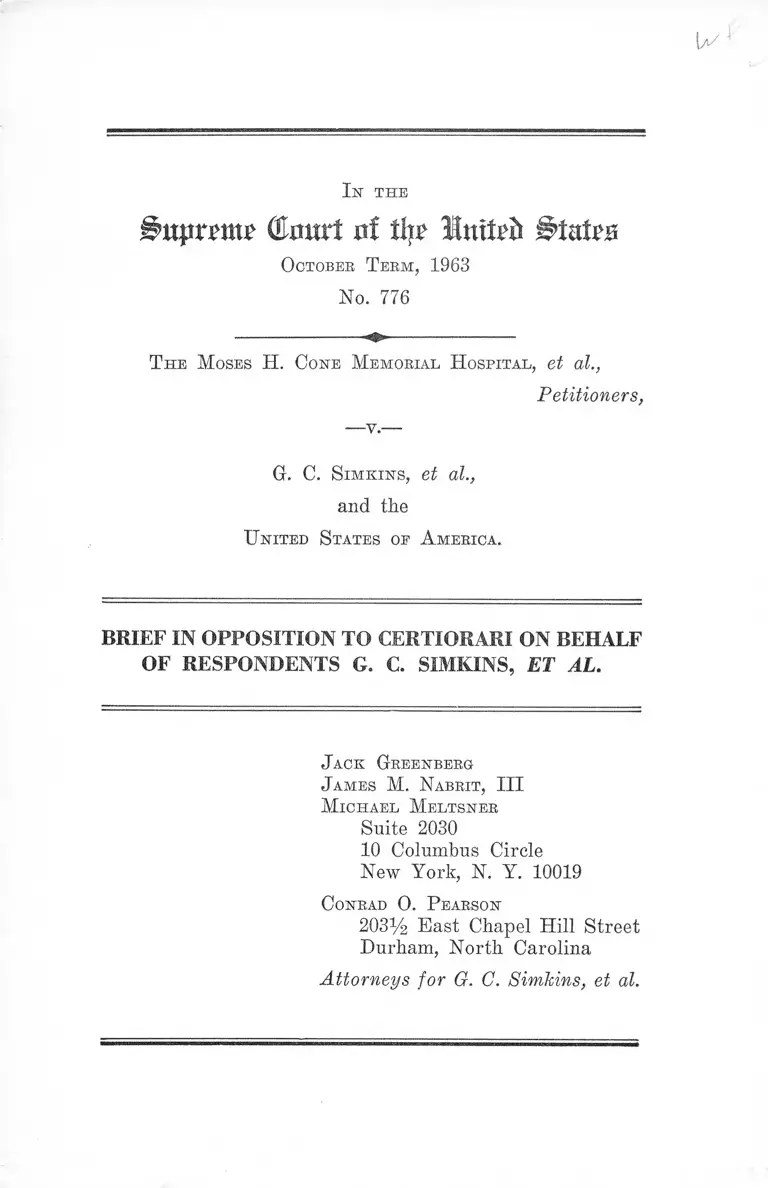

Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital v. Simkins Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital v. Simkins Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1963. 97dee3d2-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f22cd110-8479-4095-aea7-754a91c62e24/moses-h-cone-memorial-hospital-v-simkins-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n THE

(Emtrt 0! % IntteJi B tn tm

O ctober T erm , 1963

No. 776

T h e M oses H . C one M emorial H ospital, et al.,

Petitioners,

— y.—

G. C. S im k ir s , et al.,

and the

U nited S tates oe A merica.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI ON BEHALF

OF RESPONDENTS G. C. SIMKINS, ET AL.

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

M ichael M eltsher

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

C onrad O. P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for G. C. Simhins, et al.

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement ................................................ 1

Federal Funds for Hospital Construction............... 4

General Facts About Hill-Burton Program ........... 5

Tlie North Carolina State P lan ................................ 5

Division of Federal and State Controls.................. 6

Opinions of the Courts B elow .................................. 6

A rgum ent ............... 9

I. The Decision of the Court Below Enjoining

Racial Discrimination at Hospitals Closely Regu

lated and Controlled by Government and Receiv

ing Large Amounts of Public Funds as Part of a

State Plan for Hospital Construction Was

Clearly Correct and Presents No Questions Cog

nizable Under Rule 19(1)(b) of the Rules of

This Court ...................... 9

II. Those Portions of Title 42 U.S.C. §291e(f) and

42 C.F.R. §53.112 Which Authorize Racial Dis

crimination Are Clearly Unconstitutional.......... 15

C onclusion ............ 18

T able of Cases

Ashwander v. Tenn. Valley Authority, 297 II. S. 288 .... 16

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 3 1 ...................................... 15

Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186.............................................. 17

11

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 754 (5th Cir. 1961) ....... 16

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ...................................... 9,15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ....... 9,10,15,16

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 ......................................................................... 9,10,13,16

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ........................................ 9,14

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ............................................ 9,14

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 220

F. 2d 387 (4th Cir. 1955) aff’d 350 U. S. 877 ............... 15

Gantt v. Clemson Agricultural College of S. Car., 320

F. 2d 611 (4th Cir. 1963) cert. den. 375 U. S. 814....... 16

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 ...................................... 15

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 8 1 ................... 9

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 ....... ............... 15

PAGE

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 6 1 .................................... 15

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 .............................. 16

McCabe v. Atchison Topeka and S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S.

151 ..................................................................................... 16

New Orleans City Park Improvement Association v.

Detiege, 358 U. S. 5 4 ...................................................... 15

Simkins, et al. v. Moses Cone Memorial Hospital, 323

F. 2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963) .......................... 7, 8,10,11,13,14

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U. S. 533 .... 15

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 15,17

Ill

PAGE

S tatutes and R egulations I nvolved

21 Fed. Reg. 9841 .....

42 C.F.R. §53.111.......

42 C.F.R. §53.112 .....

42 U.S.C. §291 ...........

42 IT.S.C. §291a.........

42 U.S.C. §291e(f) ....

42 U.S.C. §291f(a)(7)

42 U.S.C. §2911 (d) ....

42 U.S.C. §291h(d) ....

42 U.S.C. §2911i(e) .....

42 U.S.C. §291m .......

................... 1

............... 5

...... 1, 5, 7, 10,15

..................... 1

...................... 8

5, 7, 8, 10, 14,15

.....................3,12

..................... 3,12

..................... 12

..................... 12

...................... 11

S tate S tatutes

N. C. Gen. Stats. §131-120 5

In t h e

^uprmp (tort nf % Intfrft

O ctober T erm , 1963

No. 776

T he M oses H . Cone M emorial H ospital, et al.,

Petitioners,

— v.—

Gr. C. S im k in s , et al.,

and the

U nited S tates of A merica.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI ON BEHALF

OF RESPONDENTS G. C. SIMKINS, ET AL.

Statement

Plaintiff, a group of Negro physicians, dentists and

patients, brought this class action to enjoin two hospitals in

Greensboro, North Carolina (The Moses H. Cone Memorial

Hospital and Wesley Long Community Hospital, herein

after called Cone and Long hospitals) and their adminis

trators from continuing to deny them and other Negroes

admission to staff and treatment facilities on the basis of

race. They also sought declaration that a portion of the

Hill-Burton Act (Hospital Survey and Construction Act of

1946, Act of August 13, 1946, 60 Stat. 1941, as amended;

42 U. S. C. §§291, et seq.) and a regulation pursuant thereto

(42 C. F. R. §53.112; 21 Fed. Reg. 9841) were unconstitu

tional. These provisions authorize racial segregation or

exclusion of Negroes from hospitals receiving grants under

2

the Act on a separate but equal theory, as an exception to

a statutory requirement of racial nondiscrimination.

Long is a charitable hospital governed by a self-perpetu

ating board of twelve trustees (60a, 200a).* Cone too is a

charitable hospital governed by fifteen trustees chosen for

four year terms, as follows (50a-52a) :

(a) Three by Governor of North Carolina;

(b) One by Greensboro City Board of Commissioners;

(c) One by Board of Commissioners of Guilford County,

North Carolina;

(d) One by Guilford County Medical Society;

(e) Eight were appointed by Mrs. Bertha Cone until her

death in 1947; now they are elected by entire Board

of fifteen;

(f) One appointed by Board of Commissioners of Wa

tauga County, North Carolina until 1961 amendment

to charter; now elected by entire Board.

Both hospitals are licensed to operate under the North

Carolina “ Hospital Licensing Act” and regulations (122a-

157a) which prescribe the management and operations of

hospitals in great detail.* 1 Enactment of the licensing law

* Citations are to appellant’s 'Appendix in the Court of Appeals.

1 For example, the rules provide among other things for medical

staff organization (123a) ; standards for facilities, organization,

and procedures in surgical operating rooms (125a-126a) ; equip

ment, organization, and procedures for the obstetric department

(126a-131a) ; separation of pediatric facilities from those for adults

and the newborn nursing service (132a) ; circumstances for ad

ministration of anesthesia (132a) ; clinical pathological laboratories

and blood tests (133a) ; that hospitals have adequate diagnostic

x-ray and fluoroscopic examination facilities (134a) ; designated

treatment facilities for emergency or outpatient service (134a);

3

was a prerequisite to participation in the Hill-Burton pro

gram (42 U. S. C. §§291f(a) (7), 291f(d)).

- Both hospitals are exempt from ad valorem taxes as

sessed by the City of Greensboro and Guilford County at

tax rates of $1.27 and $0.82 per $100 evaluation respectively.

The cost of the Hill-Burton construction projects for the

two hospitals set forth in this record (Cone: $7,367,023.32;

Long: $3,927,385.40) indicates that their property is ex

tremely valuable and that the value of the tax exemption

is substantial for each hospital.2

Both hospitals have a variety of contacts with govern

ment3 as a result of their involvement in the Hill-Burton

hospital construction program. In summary, both hospitals

have received large amounts of public funds, paid by the

United States to the State of North Carolina and then by

North Carolina to the hospitals. They received the funds

as a part of a “ State Plan” for hospital construction, which

contemplates and authorizes them to exclude Negroes. This

plan was approved by the Surgeon General of the United

States. They are subject to a complex pattern of govern

mental regulations and controls arising out of Hill-Burton

participation.

isolation rooms (135a) ; regulation of hospital pharmacies (135a-

136a) ; and records (136a-138a); organization of the nursing staff,

including minimum numbers (133a-139a); detailed provision for

hospital food service (139a-145a).

2 Assuming assessment at 50% of actual value, and given the

combined city-county rate of $2.09 per $100, Cone’s exemption is

worth about $76,985 per annum and Long’s is worth about $40,681

per annum.

• 3 Cone Hospital also participates in a nurses training program

with two tax supported, state schools, the Woman’s College of the

University of North Carolina and the Agricultural and Technical

College of North Carolina (an all Negro school). Student nurses

at the schools receive part of their training at Cone (55a-57a)

and carry out assignments at the hospital under the supervision

of their teachers, including assisting doctors and nurses, treating

patients, keeping hospital records, etc.

4

Federal Funds for Hospital Construction

When this action was commenced, the United States had

appropriated $1,269,950.00 to Cone and $1,948,800.00 to

Long. Cone’s allocation amounted to about fifteen percent

of the total construction expenses involved in its two proj

ects. Long’s share constituted about fifty percent of the

total cost of its three projects (203a-204a).

The following table summarizes the various grants.4

CONE HOSPITAL

Project No. Federal Funds

and Year Appropriated

_ Approved Purpose 5/8/62

NC-86

(1954) General hospital con

struction ........... . $ 462,000.00

NC-330

(1960) Diagnostic and treat

ment center; gen

eral hospital con

struction ............... 807,950.00

Federal

Total Cost % of

of Project Cost

$5,277,023.32

2,090,000.00

T otal ...... ...... ....... ............

NC-311

(1959) New hospital

struction

NC-353

(1961) Laundry

NC-358

(1961)

........ $1,269,950.00*

LONG HOSPITAL

con-

$1,617,150.00

66,000.00

H o s p i t a l Nurses

Training School .. 265,000.00

$7,367,023.32 17.2%*

$3,314,749.40 ----

120, 000.00 --------

492,636.00 -— -

Total ...... -........................ -....... $1,948,800.00** $3,927,385.40 49.6%*

* The District Court found “approximately” 15% for Cone and “approxi

mately” 50% for Long.

**A11 funds to Cone had been paid as of 5/8/62; $1,596,301.60 had been

paid to Long by that date.

. 4 ^ee, generally, Findings 11 through 17 (201a-204a). Further details appear

m the original record, Exhibits A through E to plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary

Judgment. (Parts of Exhibit B appear at 93a-103a.)

5

General Facts About Hill-Burton Program

The Hill-Burton program requires that states wishing to

participate must inventory existing facilities to determine

hospital construction needs and develop construction prior

ities under federal standards. State agencies designated to

perform this function are to adopt state-wide plans for

hospital construction to be approved by the Surgeon Gen

eral of the United States. The Act provides for grants of

federal funds to construct new or additional facilities for

government owned and voluntary nonprofit hospitals.6

The Surgeon General has authorized state plans to meet

the racial nondiscrimination requirement of 42 U. S. C.

§291e(f) by approving plans for separate facilities for

“ separate population groups” (42 C. F. It. §53.112). When

state plans are submitted on this basis, the state agency

and the Surgeon General may waive the requirement that

facilities built under the Act “be made available without

discrimination on account of race, creed or color, to all per

sons residing in the area to be served by that facility” (42

C. F. R. §53.112; see also, §53.111).

The North Carolina State Plan

In North Carolina the state agency authorized to operate

under the Hill-Burton program is the North Carolina Medi

cal Care Commission (N. C. Gen. Stats. §131-120). The

Medical Care Commission has adopted and periodically re

vised a “ State Plan” for separate facilities for Negroes

and whites in the Greensboro area (120a) :

Existing

Acceptable Beds

Area Name of Facility Location White

Non-

White

B-6 L. Richardson Memorial

Hospital ____________ Greensboro 0 91

Wesley Long Hospital .. Greensboro 220 0

Moses H. Cone Hospital Greensboro 482 0

Subtotals .. 702 91

5 A useful description of the over-all program and of the various types of

hospitals is contained in the “Affidavit and Report” of the General Counsel of

6

Accordingly, when the various project applications were

made by Cone and Long, the required assurance against

racial discrimination was waived by the Medical Care Com

mission and this was approved by the Surgeon General.* * * 6

Division of Federal and $tate Controls

The overall plan of the Hill-Burton program reflects a

division of power and responsibility between federal and

state governments for control and supervision of various

matters affecting participating hospitals. These provisions

may be sorted into seven categories: (1) control over con

struction contracts and the construction period; (2) con

trol over details of hospital construction and equipment;

(3) control over future operation and status of hospitals;

(4) control over details of hospital maintenance and opera

tion; (5) control of size and distribution of facilities; (6)

rights of project applicants and state agencies; and (7)

regulation of racial discrimination. The character of this

“ intricate pattern of governmental regulations, both state

and federal” is summarized by the Court of Appeals at

323 F. 2d 964-65.

Opinions of the Courts Below

The district court found that racial discrimination was

“ clearly established” (205a) and that the “ sole question”

was whether “defendants have been shown to be so im-

the Department of HEW who was the principal technical drafts

man of the law (173a-188a). This Report was filed in the district

court by the United States.

6 On Projects NC-86 and NC-330, the Cone Hospital initially

gave an assurance of nondiscrimination, but this was withdrawn

with the approval of the Medical Care Commission and the Sur

geon General, on the ground that “ the non-discrimination agree

ment was erroneously executed as a result of clerical inadvertence”

for which the Commission was responsible (104a-106a, 201a-202a).

7

pressed with a public interest as to render them instru

mentalities of government, and thus within the reach of the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments . . . ” (206a-207a).

After examining defendants’ various relationships with

federal and state governmental agencies, the court con

cluded that defendants were not subject to constitutional

restraints against discrimination (221a). For this reason,

the court refused to decide the validity of the separate

but equal provision of the Hill-Burton Act (220a).

On November 1,1963 the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit, sitting en banc, reversed the decision of the District

Court, 323 F. 2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963). The Court, per

Sobeloff, Chief Judge, found the necessary “ ‘degree of

state [in the broad sense, including federal] participation

and involvement’ ” , 323 F. 2d at 967,7 present as a result of

the participation by the hospitals in the Hill-Burton pro

gram. The court emphasized massive use of public funds,

“ extensive state-federal sharing” in a common plan for

state hospital development, and that the Hill-Burton pro

gram was not limited to the granting of aid to individual

hospitals: “ It shows rather a Congressional design to in

duce the states upon joining the program to undertake the

supervision of the construction and maintenance of ade

quate hospital facilities throughout their territory. Upon

joining the program a participating state in effect assumes

as a state function the obligation of planning for adequate

hospital care.” 323 F. 2d at 967-69. In addition, the court

emphasized that the challenged discrimination had been

sanctioned affirmatively by state and federal governments

pursuant to federal law and regulation, 323 F. 2d at 968;

42 U. 8. C. §291e(f); 42 C. F. R. §53.112.

The court also held that the constitutionality of the pro

visions of the Hill-Burton Act which authorized racial

7 The brackets are in the court’s opinion.

8

discrimination was properly before it. Finding in the legis

lative history of the Act a desire on the part of Congress to

permit the states to develop programs of hospital construc

tion that would provide adequate service “ to all their

people” 42 U. S. C. §291a, the court held, “ it served the

dominant Congressional purpose best to prune from the

statutory provision only that language which adopted what

is now known to be an unconstitutional means of establish

ing a constitutional end.” 323 F. 2d at 969. The court,

therefore, let stand the general prohibition against dis

crimination in 42 IT. 8. C. §291e(f) and found unconstitu

tional the exception tolerating separate but equal facil

ities :

. . . but an exception shall be made in cases where sep

arate hospital facilities are provided for separate pop

ulation groups if the plan makes equitable provisions

on the basis of need for facilities and services of like

quality for each such group . ..

9

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Decision of the Court Below Enjoining Racial

Discrimination at Hospitals Closely Regulated and Con

trolled by Government and Receiving Large Amounts

of Public Funds as Part of a State Plan for Hospital

Construction Was Clearly Correct and Presents No Ques

tions Cognizable Under Rule 1 9 ( l ) ( b ) of the Rules of

This Court.

Decisions of this Court leave little doubt that govern

mental action as broad, significant, and effective as that

found in this case involves Fifth Amendment due process8

and Fourteenth Amendment due process and equal pro

tection9 strictures against racial discrimination. Racial

discrimination is constitutional only when “unsupported

by State authority in the shape of laws, customs, or ju

dicial, or executive proceedings” or when “ not sanctioned

in some way by the State.” 10 Discrimination is forbidden

when the State participates “ through any arrangement,

management, funds or property” 11 or when the State

places its “power, property or prestige” behind the dis

crimination.12

In this case racial segregation, which repeatedly has

been held to constitute discrimination per se since Brown

8 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497; Hirabayashi v. United States,

320 U. S. 81, 100.

9 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483: Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1,19.

.10 Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3,17.

11 Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 4, 19.

12 Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, 725.

10

v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, has been explicitly

authorized by a federal statute13 antedating Brown. The

discrimination has been approved by agencies and officials

of North Carolina and the United States (93a, 99a, 113a,

120a). Large sums of public moneys have been expended

by government to support the hospitals. They have sub

mitted to a comprehensive pattern of state and federal

controls in return for these funds and have become part

of a state master plan for hospital construction on a state

wide basis. The hospitals are aided by the state because

they fulfill a public function which the state would have to

perform if the hospitals did not. North Carolina has

granted these hospitals the power to operate and the privi

lege of receiving federal aid.14 See 323 F. 2d at 967-68.

The petition for certiorari filed by the hospitals sug

gests that the Court of Appeals determined that the hospi

tals should be restrained from racial discrimination solely

on the ground that they have received money from the

United States. Reasoning from this faulty premise, peti

tioners urge that the court below sanctioned a rule of limit

less application which would apply the Constitution to

every area of human endeavor. The parade of “horribles”

suggested by petitioners (see Petition for Certiorari, pp.

8-10) bears, however, no relationship to the carefully

worded and limited opinion of the Court of Appeals. In

their zeal to obtain review before this Court, petitioners

have asked the Court to review a decision never rendered.

Applying the principles of Burton v. Wilmington Park

ing Authority, 365 U. S. 715, the Court of Appeals found

13 42 U. S. C. §291e(f) ; 42 C. F. R., §53.112.

14 In addition, as to Cone, two other factors should be noted:

(1) the State has passed legislation directing public officials to

appoint members of its governing Board and (2) the State has

chosen to train students enrolled at public colleges at the hospital.

11

that receipt of large sums as part of a complex statutory

plan15 for the construction of hospitals on a state-wide

basis resulted in application of the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments, 323 F. 2d at 965-67. The court also relied on

the Congressional purpose (as shown in the legislative

history of the Hill-Burton Act) to induce the states to as

sume the responsibility for planning the construction,

financing, and regulation of adequate hospital facilities

throughout the state, and the affirmative sanction of the

hospitals’ racial discrimination given by Hill-Burton Act

and regulations, 323 F. 2d at 968.

The decision of the Court of Appeals is rooted in the

peculiar soil of the Hill-Burton program. For example,

these hospitals are subject to a variety of government con

trols by virtue of their participation in the federal-state

hospital construction program. The character of the physi

cal facilities and the equipment of the hospitals is closely

controlled by both federal and state governments. The

effect of this regulation of construction and equipment on

the future operations of the hospitals is manifest. Bequir- 16

16 Petitioners earnestly contend that the Hill-Burton Act itself

expressly disclaims any federal right to exercise supervision or

control over the administration of any hospitals receiving funds

under the Act and rely on 42 U. S. C. §291m. Section 291m states:

State control of agencies.— Except as otherwise specifically

provided, nothing in this subchapter shall be construed as

conferring on any federal officer or employee the right to

exercise any supervision or control over the administration,

personnel, maintenance, or operation of any hospital, diag

nostic or treatment center, rehabilitation facility, or nursing

home M'ith respect to which any funds have been or may be

expended under this subject.

_ Petitioners’ reliance on this provision is misplaced. The provi

sion states, “except as otherwise specifically provided,” and the

Hill-Burton Act and regulations specifically provide for a great

amount of control, 323 P. 2d at 964, 965. Secondly, the provision

is entitled, “State control of agencies,” and can at the most be

taken to mean that where there is possible conflict between state

and federal agencies, state regulation should prevail.

12

ing that a hospital build and arrange a particular depart

ment and stock it with approved equipment obviously de

termines the character of the service the hospital will

render in the future. Beyond this, the federal statute re

quires that the states must directly regulate the details of

hospital maintenance and operation. In order to partici

pate in the Hill-Burton program North Carolina had to

undertake an elaborate regulatory and licensing scheme

(42 U. S. C. §§291f(a)(7), 291f(d)). This state control

over the defendant hospitals’ operation is exact and de

tailed (see footnote 1, supra).

The funds paid to these hospitals under the Hill-Burton

Act are to be used solely for carrying out the project as

approved by the State and Surgeon General.16 If the hos

pitals sell or transfer ownership within twenty years to

anyone not qualified under the Act to apply for funds or

not approved by the state agency, or if the hospitals cease

to be nonprofit, the United States is authorized to recover

the present value of the federal share of the approved

project.16 17

Under Hill-Burton, the number and distribution of hos

pital beds in an area is decided by State and Federal Gov

ernments. Once funds are granted bringing an area up to

the standard of hospital beds considered adequate for the

population, no further beds can be programmed. If North

Carolina had chosen to build publicly owned hospitals in

Greensboro, Cone and Long could have been denied all

federal aid. On the other hand, the aid granted them now

prohibits the construction of duplicating city, county, or

other nonprofit facilities with federal aid. The participat-

16 42 U. S. C. §2911i (d).

17 42 U. S. C. §291h(e).

13

ing hospitals have become the chosen and exclusive instru

ments to carry out governmental objectives.

In addition to operating “ as integral parts of comprehen

sive joint or intermeshing state and federal plans,” 323 F.

2d at 967, the Cone and Long hospitals are the bene

ficiaries of approximately 1.2 and 1.9 million dollars, re

spectively, paid to them through the Treasurer of the State

of North Carolina, from the United States of America

under the Hill-Burton program. Prior to receipt of Hill-

Burton assistance, Long Hospital operated a 78-bed hos

pital considered obsolete by North Carolina (160a) and

unsuitable by the United States of America (93a). Long

has now constructed and operates a 220-bed modern hos

pital, a nurses training school and has a $120,000 laundry

constructed under Hill-Burton with 50 per cent federal

funds. Cone Hospital has completed construction of a

300-bed hospital, a 182-bed addition, and a diagnostic and

treatment center with the assistance of the United States

and the State of North Carolina under the Hill-Burton

program.

These federal grants in excess of a million dollars to

each hospital distributed in accordance with state and fed

eral priorities obviously are substantial. (The tax exempt

status of the hospital’s property increases the financial

subsidy. Cf. Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365

U. S. at 724.)

The effect of governmental subsidy upon an otherwise

private entity is highly relevant in deciding whether the

restraints of the Constitution should apply. The argument

of petitioners that the effect of three million dollars of

public funds on the hospitals is insignificant for purposes

of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments is erroneous.

Here, there is a governmental participation through an

“ arrangement,” “ funds,” and “property” calling for the ap-

14

plication of constitutional principles against discrimina

tion. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 4, 19. It would be diffi

cult to know what Cooper v. Aaron means if it does not

embrace contributions of funds in the million dollar range

to build tax exempt property.

Affirmative Governmental Sanction of Discrimination

In addition to the interrelation of the hospitals with gov

ernment, an additional factor compels the conclusion that

the discrimination practiced is within the purview of the

Constitution. This discrimination was sanctioned affirma

tively by a federal statute and regulations, and by a state

plan for hospital construction on a segregated basis. The

conduct of private persons is insulated from constitutional

requirements only insofar as it is “ unsupported by State

authority in the shape of laws, customs, or judicial or ex

ecutive proceedings” or is “not sanctioned in some way by

the State.” Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 17. Here the

affirmative state sanction of racial segregation (the state

plan for segregation in the Greensboro area) enables the

hospitals to avoid giving an assurance not to discriminate

as a condition of receiving the funds. This is in accord

with the Hill-Burton Act (42 IT. S. C. §291e(f)) which al

lows the states to authorize segregation in either govern

ment hospitals or nonprofit hospitals. As segregation is

supported by federal statute and regulations and by state

executive decisions, i.e., the state plan, the decision of the

Court of Appeals enjoining discrimination is clearly cor

rect. See 323 F. 2d at 968 n. 16, and cases cited.

15

II.

Those Portions of Title 42 U. S. C. §29Ie(£ ) and

42 C. F. R. §53 .112 Which Authorize Racial Discrimina

tion Are Clearly Unconstitutional.

The provisions of the Hill-Burton Act and regulations

declared unconstitutional by the court below authorize hos

pitals receiving federal funds to segregate or exclude Ne

groes on a separate but equal basis as an exception to a

general statutory policy of nondiscrimination.

Since Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, the

“ separate but equal” doctrine has been repudiated in re

gard to every type of facility to which it was applied.18 * * In

sofar as the Hill-Burton Act and federal regulations

authorize the defendants as agencies of the state and fed

eral governments to engage in racial discrimination, these

provisions obviously conflict with the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497; Brown v.

Board of Education, supra.

The hospitals seek to avoid the massive weight of this

authority by contending that the act does not require dis

crimination but simply provides that a nondiscrimination

assurance will be waived when separate facilities are pro

vided for Negroes in the community. That the provision is

cast in terms of a waiver permitted by government in no

way changes its unconstitutionality. The Kansas statute

ruled unconstitutional by this Court in Brown v. Board of

18 Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 220 F. 2d

387 (4th Cir. 1955), aff’d 350 U. S. 877; Holmes v. City of Atlanta,

350 U. S. .879; Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903; Bailey v. Patterson,

369 U. S. 31; Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350; New Orleans

City Park Improvement Association v. Detiege, 358 U. S. 54;

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U. S. 533; Johnson v.

Virginia, 373 U. S. 61.

16

Education, supra, authorized and did not require racial

discrimination.19

As the act and regulations authorize the discrimination

which the Court of Appeals found unconstitutional and en

joined, the constitutionality of the act and regulations are

necessarily presented for decision. To the extent that the

Constitution forbids racial discrimination by the hospitals,

it also forbids statutory authorization of such discrimina

tion.

To argue as do the hospitals that even if their conduct

is subject to constitutional responsibility, respondents are

not entitled to declaratory relief—declaring the statute

which authorized such conduct unconstitutional—would be

inconsistent as well as potentially confusing.20 To be sure,

settled principles of constitutional construction reflect judi

cial concern with unnecessary decisions of constitutional

questions.21 But there is no suggestion in the cases—and

more important in the theory of judicial restraint under

lying them—that a statute authorizing invalid conduct will

19 See also Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715, 726-27, Mr. Justice Stewart concurring; McCabe v. Atchison

Topeka and S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 151; cf. Lombard v. Louisiana,

373 U. S. 267; Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 754 (5th Cir. 1961) ;

Gantt v. Clemson Agricultural College of 8. Car., 320 F. 2d 611

(4th Cir. 1963), cert. den. 375 U. S. 814.

20 The United States argued forcefully in the district court that

failure to adjudicate the constitutionality of the Act in such a

context would subject the administration of the Act to uncer

tainty and subject the United States to possible liability for

maladministration. “Not only is it unseemly for a high executive

official of the United States to continue administering a statute

which under the decisions of the courts seems clearly unconsti

tutional, but if the Surgeon General misconceives his legal obli

gations under the Act he may well subject himself to suit by those

injured by his conduct.” (Memorandum in support of Conclu

sions of Law Proposed by the United States, p. 21.)

21 See Ashwander v. Tenn. Valley Authority, 297 U. S. 288, 345

et seq.

17

not be declared unconstitutional when the conduct itself

is held unconstitutional. Such a result would turn a rule

of avoidance of unnecessary constitutional decisions into

a rule of abdication. Failure to declare the separate but

equal provisions of the Hill-Burton Act unconstitutional

would not be avoidance of a decision of “ gravity and

delicacy” 22 for fundamental reasons of political organi

zation but a simple failure to articulate an inescapable

conclusion. In Turner v. Memphis, 369 IT. S. 350, relied on

by the hospitals, a state statute might have, under a

strained construction, permitted the conduct enjoined and

the court was merely applying settled principles of com

ity in not construing the statute. Here, a federal statute

authorizes unequivocally the racial segregation enjoined.

Secondly, in Turner Negro plaintiffs did not seek a dec

laration of the unconstitutionality of the statute.

Apart from vague notions of judicial restraint, the hos

pitals suggest no viable theory upon which failure to

adjudicate the constitutional question should be based.

Negro physicians, dentists and patients surely have “ such

a personal stake in the outcome of the controversy as to

assure that concrete adverseness which sharpens presen

tation of issues” which was said in Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S.

186, 204, to be the “ gist of the question of standing.” And

it is not material that the hospitals did not rely explicitly

on the Hill-Burton Act provision authorizing segregation.

They have received the benefit of and acted in accordance

with its terms, and they have defended the practice which

the statute authorizes. The constitutionality of a statute

of the United States is inescapably bound up in this litiga

tion, and the question is not avoided because it is not

fully articulated in a defensive pleading. The hospitals

did not defend explicitly on the basis of the validity of

22 Ibid.

18

their statutory authorization to segregate because deci

sions of this Court made the success of such an argument

improbable. Any suggestion that this constitutional ques

tion is not shaped by the record is without merit.

In summary, the decision below accords with principles

recently articulated by this Court. There is no conflict of

circuits; nor is there any other persuasive reason why

certiorari should be granted.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, f o r the fo re g o in g reasons, respondents p ra y

that the w rit o f ce r tio ra ri be denied.

B esp ectfu lly subm itted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

M ichael M eltsner

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

C onrad O. P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

P. O. Box 1428

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for G. C. Simkins, et at.