Crossing the Bridge to Equity and Excellence: A Vision of Quality and Integrated Education for Connecticut Report

Reports

December 31, 1990

43 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Crossing the Bridge to Equity and Excellence: A Vision of Quality and Integrated Education for Connecticut Report, 1990. 6b7a68e3-a146-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f23d43bc-6552-4c5a-b3ad-11a606f7290f/crossing-the-bridge-to-equity-and-excellence-a-vision-of-quality-and-integrated-education-for-connecticut-report. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

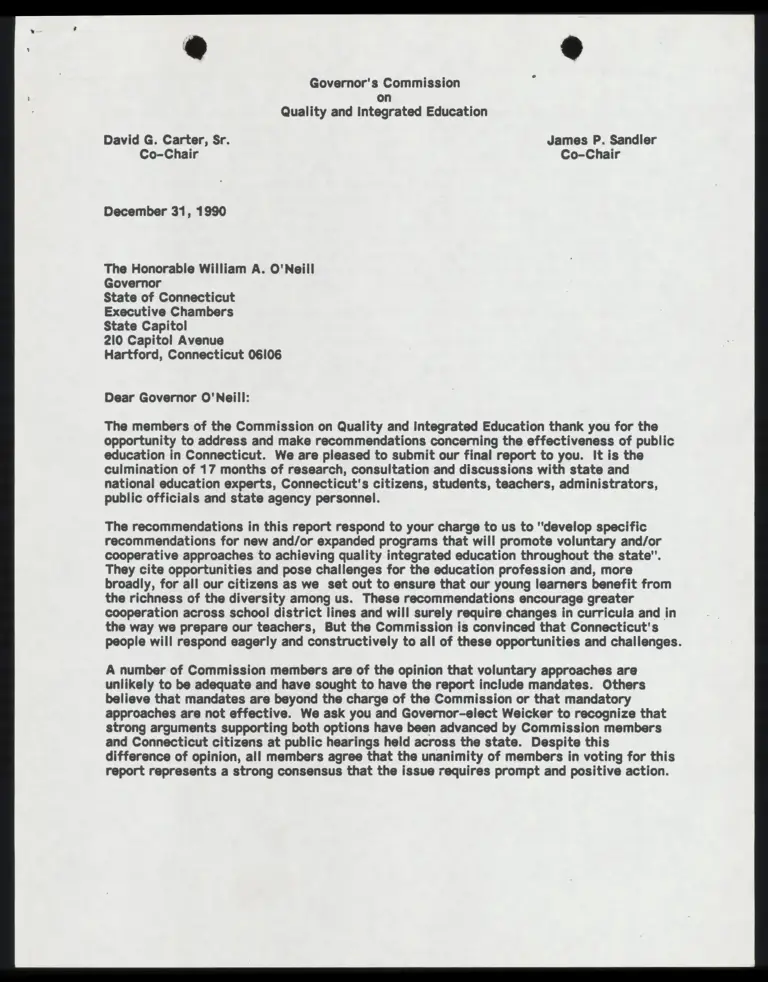

Governor's Commission

on

Quality and Integrated Education

David G. Carter, Sr. James P. Sandler

Co-Chair Co-Chair

December 31, 1990

The Honorable William A. O'Neill

Governor

State of Connecticut

Executive Chambers

State Capitol

210 Capitol Avenue

Hartford, Connecticut 06106

Dear Governor O'Neill:

The members of the Commission on Quality and Integrated Education thank you for the

opportunity to address and make recommendations concerning the effectiveness of public

education in Connecticut. We are pleased to submit our final report to you. It is the

culmination of 17 months of research, consultation and discussions with state and

national education experts, Connecticut's citizens, students, teachers, administrators,

public officials and state agency personnel.

The recommendations in this report respond to your charge to us to "develop specific

recommendations for new and/or expanded programs that will promote voluntary and/or

cooperative approaches to achieving quality integrated education throughout the state''.

They cite opportunities and pose challenges for the education profession and, more

broadly, for all our citizens as we set out to ensure that our young learners benefit from

the richness of the diversity among us. These recommendations encourage greater

cooperation across school district lines and will surely require changes in curricula and in

the way we prepare our teachers, But the Commission is convinced that Connecticut's

people will respond eagerly and constructively to all of these opportunities and challenges.

A number of Commission members are of the opinion that voluntary approaches are

unlikely to be adequate and have sought to have the report include mandates. Others

believe that mandates are beyond the charge of the Commission or that mandatory

approaches are not effective. We ask you and Governor-elect Weicker to recognize that

strong arguments supporting both options have been advanced by Commission members

and Connecticut citizens at public hearings held across the state. Despite this

difference of opinion, all members agree that the unanimity of members in voting for this

report represents a strong consensus that the issue requires prompt and positive action.

* » :

Governor William A. O'Neill 2.

Commission members feel a sense of urgency to reduce racial and economic isolation, a

problem the enormity of which grows alarmingly with every passing moment. Today's

youngsters are critical to tomorrow's civilization, its social relationships and its work

force, citizenship and leadership. Thus, educational quality is not just an issue for

educators and parents. Economics, simple justice and the demands of modern society

necessitate that we provide high-quality, integrated educational programs for all

students. With the size of the labor pool diminishing, we cannot afford to undereducate

any of our young people -- but we are. With our cities being more and more alienated,

we cannot afford to leave their residents increasingly isolated -- but we are. We must

take the lead in ensuring that today's young learn all of the skills, knowledge and

attitudes necessary to become productive members of Connecticut's work force and our

society as a whole. The alternative is an accelerating divisiveness, apathy, and anger

that are dehumanizing, threatening and costly. We must act now. |

Education cannot shoulder the burden of social change by itself. We now realize that no

set of educational strategies can fully address the myriad social issues that produce

inequality and undermine education. Substance abuse, hunger, parental neglect, crowded

and substandard housing and inadequate employment opportunities disproportionately

attack minority children in our state and divert them from educational opportunity. -

Unless other elements of society and other institutions actively share with education the

responsibility for addressing and remedying these conditions, not even the best of

strategic education plans can succeed.

This report is just a beginning. It focuses only on the role education has to play in the

pursuit of quality and integrated learning. The time has come to enlist those other

institutions we just mentioned. Accordingly, the Commission asks that the next

Governor advance the work of this Commission into such related areas of concern as

housing, human resources, income maintenance, and employment. If we refuse to face

these issues now, they will become more severe threatening our economic and social well

being.

The Commission recognizes that the state is confronting a serious budget problem, and

the Commission acknowledges that, while some of its recommendations will not require

any new money, others will. The fact that the Commission has not attached a dollar

amount to each recommendation must not bar legislative consideration. We can think of

no better investment than underwriting the opportunity for all our children to achieve to

their full potential and to welcome and value diversity.

Finally, we gratefully thank the many individuals and institutions that supported our work

with contributions of time, expertise and money, particularly The New Haven Foundation,

The Hartford Foundation, Pequot Community Foundation, Bridgeport Area Foundation, and

Fairfield County Cooperative Foundation. We also welcome the public reception of our

work. Many of our fellow Connecticut citizens already recognize that the

recommendations in this report point us toward the highest possible quality of public

education and a reaffirmation of the value of diversity in our State.

Respectfully submitted, Respectfully submitted,

David G. Carter es P. Sandler

Co-Chair o-Chair

CROSSING THE BRIDGE TO EQUITY AND EXCELLENCE:

A VISION OF QUALITY AND INTEGRATED EDUCATION FOR CONNECTICUT

Recommendations for Quality and

Integrated Education

The Report of the Governor's

Commission on Quality and

Integrated Education

December 1990

®

COMMISSION MEMBERSHIP LIST

Co-Chair

David G. Carter, President

Eastern Connecticut State University

Co-Chair

James P. Sandler, Attorney-at-Law

Byrne, Slater, Sandler, Shulman & Rouse

Alice Bethea, Business Manager

Intrn'l Ladies Garment Workers Union

Christina P. Burnham

Connecticut Association of

Boards of Education

Nancy Ciarleglio

League of Women Voters

Naomi K. Cohen

. State Representative

~ Amado Cruz, Principal

Hartford High School

Carol P. Duggan, Past President

Parent Teachers. Association

- M. Adela Eads

. State Senator

. Badi Foster, President

Aetna Institute

for Corporate Education

Thomas P. Geyer, Former.CEO

New Haven Register

Abraham Glassman, Chair

Connecticut State Board of Education

Peter Handrinos, Student

Yale University

Michael Helfgott

Executive Director

University of Connecticut

Educational Park, Inc.

Henry Kelly, Principal

Winthrop Elementary School

Bridgeport, Connecticut

Hartzel Lebed, Retired President

CIGNA Corporation (resigned 9/90)

I. Charles Mathews, Deputy Mayor

Hartford, Connecticut

Ramon A. Pacheco

Attorney-at-Law

Hartford, Connecticut

William R. Papallo, Superintendent

Stamford Public Schools

George Schatzki, Professor

University of Connecticut Law School

Ruth Sims, Former First Selectman

Greenwich, Connecticut

Joseph M. Suggs, Mayor

Bloomfield, Connecticut

Kevin B. Sullivan

State Senator

Gerald N. Tirozzi, Commissioner

Connecticut State Department of

Education

Robert M. Ward

State Representative

Molly Whalen, Student

Bloomfield High School

Deborah G. Willard

Teacher of the Year, 1986

Glastonbury High School

Robert Wood

Henry R. Luce Professor

Wesleyan University

PREFACE

Unlike those states blessed with abundant natural resources--silver, oil,

coal, iron ore and gold--Connecticut has always depended directly for its

welfare and prosperity on the industry and ingenuity of its people.

Connecticut must, therefore, continually invest in its citizens in order to

maintain and enhance its quality of life. More specifically, the executive

and legislative branches of government, our educators, and all our people earn

the greatest possible return on their investment by making those choices most

certain to produce a better educated populace.

We must set basic standards, of course. But more importantly, we must

expect and help our students to achieve, knowing as we do so that students

become wise and productive citizens when they meet and understand and then

value people from cultures, races and genders other than their own. Students

benefit, and Connecticut benefits, from the richness of diversity.

The Governor's Commission on Quality and Integrated Education transmits

this Report fully aware that other commissions, committees, and reports

precede us. Nevertheless, we consider this report fresh and imperative. It

focuses on and calls attention to both a critical problem that threatens our

State and a need that, if met, can sustain and nourish it: we must ensure

quality and integrated education for all our young learners.

The Commission hopes that voluntary methods will enable all of

Connecticut's public school students to receive a quality and integrated

education. We feel the recommendations in our report should be enacted and

that they then must be given time and resources to succeed.

We are also mindful that to the extent that the achievement of these

educational goals does not take place, the futures of far too many of our

children will continue to be at risk. We, therefore, suggest that there be a

finite amount of time given to these recommendations to determine if they do

succeed. If it is deemed that they don't, other approaches must then be

considered.

We hope to see our report discussed and debated. But once the

discussions cease, we expect our recommendations to generate action.

Connecticut has the people and the good will to meet our explicit challenges.

The question now before our State is this: can we afford not to help our

students reach their potential in life while learning to welcome diversity?

ii

INTRODUCTION

The State of Connecticut has long acknowledged an affirmative

responsibility to desegregate its public schools and to guarantee educational

equality for all students. The State's history of affirmative achievement has

appeared in the following instances:

(1) Since 1966, the State has provided both financial support and

technical assistance for one of this country's first voluntary

interdistrict transfer programs -- Project Concern -- which was

designed to promote voluntary desegregation among schools in urban

metropolitan areas.

(2) In 1969, the Connecticut General Assembly adopted legislation to

address what it saw as growing racial isolation in some Connecticut

districts. This law required the schools within a single district be

racially balanced. The racial balance regulations were adopted in

1979. Under the regulations the proportion of minority students in

any school must be within 25% points, plus or minus, of the

proportion of minority students in the district as a whole.

(3) Beginning in 1979, Connecticut's formula for financing public schools

has taken into account the needs of urban school districts by

including in the aid formula the number of children from low income

families. In 1989, a weighting for the number of students who score

below the remedial standard on the Connecticut Mastery Test was added

to the State's major school aid formula. :

(4) Since 1970, the State has supported magnet schools and programs as a

means for improving the overall quality of education while reducing

racial isolation. This support includes technical assistance to

intradistrict magnet schools. Recently, the legislature authorized

special bond funding for the construction or renovation of buildings

to house interdistrict magnet schools.

(5) In 1988, the State Department of Education issued a report on the

current status of racial isolation in the State. In response to this

report and at the direction of the State Board of Education, the

Department of Education prepared a second report recommending options

for achieving quality and integrated education. This report outlined

a number of steps the State could take to advance integration. One

of these "next steps" suggested that the Governor establish a "blue

ribbon" commission to recommend strategies for achieving voluntary

interdistrict integration.

(6) Since 1988, the legislature has focused the competitive interdistrict

cooperative grant program on educational programs that provide

opportunities for integration with over 100 districts participating.

More recently, the competitive summer school grant program has been

revised to favor programs that promote multiracial and multicultural

understanding.

The Governor's Commission on Quality and Integrated Education, appointed

by Governor O'Neill on September 20, 1989, represented still another

affirmative step in Connecticut's efforts to integrate its public schools.

The Commission--which includes citizens from across the state, including

legislators, corporate and community leaders, a member of a local school

board, parents, educators and scholars--came together to study the issue and

develop creative ways to promote voluntary and integrated education in

Connecticut. Specifically, the Governor charged the Commission to:

*(1) review the demography of the State of Connecticut and the trends in

and reasons for difference in the racial, ethnic and economic makeup

of Connecticut's public schools;

(2) review programs that foster racial and economic integration in public

schools, including magnet school programs, in Connecticut and other

states identifying their strengths and weaknesses;

(3) identify changes in the current school construction law and

regulations that would foster integration;

(4) develop proposals to recruit and retain minorities in the teaching

profession;

(5) develop proposals for both interdistrict and intradistrict programs

to promote quality and integrated education; and

(6) review current state aid programs to ensure support for proposed

integration programs."

Finally, the Governor asked the Commission to report its recommendations by

December 31, 1990.

Defining Quality and Integrated Education

The Commission immediately faced the need to define "quality and

integrated education". It found help in reports and studies on early

desegregation efforts but found as well that the earliest desegregation

campaigns, which emphasized physical desegregation, occasionally failed to

provide a quality and integrated education for all students. In addition, the

Commission members agreed that what many observers characterize as second

generation school desegregation plans, which focus on "equal treatment and

equal access" within schools, also fell short of quality and integrated

education. Ultimately, the Commission concluded that a "quality and

integrated education" should expose students to an integrated student body and

faculty and a curriculum that reflects the heritage of many cultures. It

should also provide all students with equal opportunities to learn and to

achieve equal educational outcomes.

1 On these points, see Reseqregation of Public Schools: The Third

Generation, A Report on the Condition of Desegregation in America's Public

Schools, the Network of Regional Desegregation Assistance Centers, June 1989

and “Desegregation: Can We Get There From Here", Phi Delta Kappan, September

1990

Growing Racial Isolation

From this definition, the Commission set out to determine whether

Connecticut students had the opportunity to obtain a "quality and integrated

education”. The Commission soon found that the goal of "quality and

integrated education" is currently blocked by increasing racial isolation.

The majority of Connecticut's students remain isolated from daily

educational contact with students of other races and ethnic groups. Over 80

percent of the State's minority students cluster in just 16, or 10 percent, of

the districts. Seven of these districts accommodate over 60 percent of our

minority students while 140 other districts are more than 90 percent white.

When social class and income levels compound the factors of racial ethnic

difference, a bleak picture of inequity emerges. Most poor children live far

away from rich children, and all too many of Connecticut's African-American,

Hispanic, and recent immigrant children are poor. They are separated because

of the inextricable relationship, that generally exists in our society between

race and family wealth. But for the young people separateness, for whatever

reason, encourages suspicion and hostility based on appearances.

From a national perspective, most African-Americans and Hispanic children

live in the large urban districts, where they are heavily concentrated and

face severe segregation and inequality. The trends are toward more and more

severe racial and class isolation in inner-city schools.

From an educational perspective, this means that the metropolitan

community is becoming a "house divided against itself," and one wonders

whether it can endure permanently half minority and half white, half middle

class and half poor, half connected to the growing sectors of knowledge and

job opportunities and half struggling against high odds to teach students

basic reading and mathematics skills, only to see terrifying percentages of

them lost from a high school system that too often leads nowhere even for

those who survive.

Racial isolation has increased and continues to increase in Connecticut.

According to a study prepared for the Commission, the past five years have

seen a significant increase in the percentage of minority students in

Connecticut's five major metropolitan areas: Bridgeport, New Haven,

Bloomfield/Hartford, Norwalk/Stamford, New London and the towns near by. Only

small increases have appeared in other areas of the state. Meanwhile, between

1984 and 1989 the number of white students declined sharply as a result of the

1970s' "baby-bust" generation. During the next ten years, the numbers of both

white and minority students will almost certainly increase in absolute numbers

while the percentage of minority students will increase somewhat, although

less than in the previous five years.

In the five major metropolitan areas (urban center and surrounding

communities) just mentioned, the percentage of minority students seems

destined to remain stable for grades K through 5 during the next ten years.

In the middle grades, Bridgeport and Norwalk should remain stable with regard

to the percentage of minority students, while the percentage of minority

students will increase slightly in Hartford and New Haven. The New London

area projects the greatest growth in the percentage of minority students in

the middle grades.

Meanwhile, the effects of currently declining enrollments, particularly

declining white enrollments, will occur at the high school level. The :

percentage of minority students in grades 9 through 12 increased significantly

between 1984 and 1989 and will continue to increase over the next ten years.

The New Haven area will probably lead, increasing from 28.0% in 1989 to 35.2%

in 1999. Hartford will increase from 27.4% minority in 1989 to 32.7% in

1999. Bridgeport will see smaller increases, from 31.1% in 1989 to 33.8% in

1999.

The school districts in the rural areas of Connecticut currently

accommodate few, if any, minority students, and they will see little, if any,

increase over the next decade unless the trend is reversed.

Schools and school districts, however, are not the cause of increasing

racial and other isolation in our state. The Commission cannot ignore the

fact that such isolation, whatever its original causes, is now fundamentally

imbedded in the larger issue of poverty and lack of opportunity in employment,

housing, health and transportation which all aspects of our society have a

shared responsibility to address.

Educational isolation certainly tends to reinforce the effects of inequity

on the attitudes and achievement of our future citizens. But our children,

schools and school districts cannot be expected alone to solve issues that

adults remain unwilling even to address meaningfully. Opportunity and

integration are societal imperatives, not just imperatives for schools.

The Commission particularly associates racial and ethnic isolation with

existing housing patterns, finding a significant relationship between the

concentration of minority students and the occurrence of publicly assisted

housing. When one compares the 14 communities with the highest percentage of

minority students (all of them over 25 percent) with the 14 communities with ;

the highest percentages of assisted housing, one finds 9 communities on both

lists--an unsurprising correlation, given the current equation between

minority status and Tow incomes. The 1989 Blue Ribbon Housing Commission

fully documented the need for more housing affordable to moderate and

low-income families, and this Commission notes that affordable housing in

suburban and rural communities could increase the diversity of their student

populations. In particular, affordable housing in the outer suburbs and rural

communities could help integrate schools where interdistrict programs with

urban schools present long-distance transportation problems.

Although encouraged by Connecticut's new regional housing compacts, the

Commission foresees that our society may not soon succeed in undoing all the

consequences of poverty and inequity. We also recognize that the State has a

fundamental interest and perhaps greater ability to influence public education

to mitigate the damages racial and other isolation is inflicting on all of us

as a society.

One way to reduce the impact of housing patterns might be to amend the

traditional school registration policies of the local school districts (i.e.,

attending the school nearest your place of residence) by encouraging (and

allowing) attendance at the school nearest the place of employment of the

parent or guardian. Many jobs still remain in the central metropolitan areas

and while the environmental benefits of car pooling and alternate means of

transportation are being emphasized, an additional benefit would be the impact

on the integration numbers in the central (or core) cities and towns; not to

mention the advantage of having a parent closeby the school in case of

emergencies and for increasing participation in the ongoing life and community

of the school (See Finding #4).

The school would need to offer a full-day program with a latch-key

recreational and educational enhancement (museum visitations, arts, music,

games, study times, remedial and homework assistance) component. Since

employment and child care are already a cost factor in employment, the program

could be supported by user fees.

Thus, most of our findings and recommendations address issues of

education. However, the Commission strongly feels that educational

opportunity cannot be addressed in isolation and that every aspect of public -

policy in every region of our state should be linked in the cooperative

enterprise of removing barriers to achievement and the common ground that

strengthens us all as a society.

Lack of Minority Faculty

The Commission also found that few students enjoy exposure to an

integrated faculty, another important aspect of a quality and integrated

education. Minority group members represent 6.3 percent of the certified

school staff, compared to almost 25% percent of the student enrollment, and

that gap too has been increasing. At the same time, "(M)inority teachers were

more heavily concentrated in the five large cities than minority students

are. The large cities employed 70.6 percent of the minority group teachers;

the small towns, just over one percent" (Minority Student and Staff Report,

SBE, 1989).

Multicultural Curriculum

Also missing from the education of many Connecticut public school students

is the chance to study a curriculum that reflects the heritage of many

cultures. Numerous national educators note that the curricula currently in

use, reflect mainly European history and culture and tend to slight the .

histories, contributions and cultures of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. To

operate effectively and empathetically in a global economy, our students need

to understand the perspectives and concerns of others. Our curriculum should

acknowledge and value both our shared core culture and the unique cultural

backgrounds of the many groups that contribute to our country and the world.

Unequal Educational Opportunities

Despite Connecticut's commitment to provide equal educational opportunity

for all of its students, the Commission found inequalities persisting,

particularly for those in urban schools. For example, a significant

under-representation of minority students exists in higher level courses while

overrepresentation of minority students can be found in remedial classes.

While the State maintains no data on the diversity of students enrolled in

advanced placement courses, its information on the number of students taking

advanced placement examinations show that of the 3,202 high school students,

minority and non-minority, who took the examination in 1988-89, only 282, or

8.2 percent, were minority students. The report What Americans Study (Policy

Information Report, Education Testing Service, Princeton, New Jersey) examines

differences in course taking by race. Nationally, "African-American 1987

graduates... continued to lag substantially behind white graduates in advanced

mathematics courses". For example 65.9 percent of white 11th graders had

taken geometry compared to 46.0 percent of African-American 11th graders.

Moreover, minority students are overrepresented in such remedial classes

as Chapter 1. In 1987-88, Chapter 1 was 47 percent non-minority and 53

percent minority, almost double the minority percentage statewide. Even when

broken down by type of community (TOC), the minority percentage in Chapter 1

remained higher than the percentage of each minority group in each TOC.

Other indicators suggest that Connecticut's minority students have yet to

receive full equal educational opportunities. For example, the widespread use

of tracking and ability grouping persists, despite the compelling studies that

show these practices inhibit student achievement, particularly for minority

students. Additional recent research questions the benefits of tracking even

for its so-called benefited students. Tracking may include retaining students

in lower grades, which flies in the face of research showing that students

retained in early grades tend, sooner or later, to become dropouts.

Recent reports on educational outcomes for poor and minority students

question the effectiveness of such current practices as ‘tracking, ability

grouping and grade retention. For example, in Education That Works: An

Action Plan for the Education of Minorities, one can read that:

In the first few days of school, judgments are made about

children in the classroom. Some children, it is decided,

are advanced, some are average, and some are behind, and so

the grouping and tracking begin. In most school systems in

our nation, this decision effectively seals the child's

fate, sometimes for life. Students classified as slow

almost never catch up and school rapidly becomes a forum

for failure, not an arena for success. By the time these

children are in middle schools, tracking intensifies and

options begin to close. Minority children are liable to be

placed in non-academic tracks because they do not fit the

stereotypical, middle-class images our present educational

system holds up as ideal (such as fluency in English,

Ld

highly educated parents, and supportive out-of-school

experiences). What many need is an enriched program to

compensate for the lack of these assets. Students must not

only hear that "all children can learn," they must feel

that they are truly valued and that they can achieve

academic success. This includes the valuing of their

culture and language and the appreciation of their

individual talents, essential ingredients for heightened

self-esteem.

A second study reported in Better Schooling for the Children of Poverty:

Alternatives to Conventional Wisdom also addresses the issue of ability

grouping or tracking. It notes that "conventional wisdom" places "an emphasis

on disadvantaged learners' lack of information and intellectual facility".

According to the report, ability grouping is a problem because "low achieving

students tend to become permanently segregated in these groupings or tracks.

To make matters worse, determinations of 'low-achievement' are not necessarily

reliable, which means that students' academic abilities can be misdiagnosed.

This happens all too often when ethnic or linguistic features (e.g., dialect

speech or limited English proficiency) are misinterpreted as signs of low

ability....Furthermore, segregation in lower-track groups carries with it a

visible stigma that contributes to certain students being labeled 'dummies',

not to mention the more limited curricula that are sometimes offered such

groups".

The report also goes on to say that "because the evidence is mixed on the

efficacy of ability grouping for low achievers, teachers should consider a

variety of alternative arrangements" and it suggests that teachers use

“heterogeneous grouping such as cooperative and team learning and more

flexible and temporary ability-grouped arrangements".

Gap Between Non-Minority and Minority Achievement Scores

The nation and Connecticut's future depends on whether we provide a

quality education for all students, rich and poor, minority and non-minority.

The Commission found the same trend throughout the country evident in

Connecticut: the achievement of non-minority students exceeds that of

minority students right from the start, and the gap widens as students

progress from kindergarten to twelfth grade. For example, the results of the

1987 Connecticut Mastery Test (CMT) for grade 4, 6, 8 show substantial gaps in

achievement between minority and non-minority students. At the fourth grade

level, 74 percent of the white students met the composite remedial standard,

but only 36 percent of African-American fourth graders and 32 percent of

Hispanic fourth graders met this standard. Similarly, 31 percent of white

fourth graders met the mastery standard, while only 6 percent of

African-American students and 5 percent of Hispanic students met this higher

standard. Similar disparities appeared on the sixth and eighth grade mastery

tests. In addition, students whose dominant language was other than English

were three times more liable to fall short of the remedial standards, and

students who were in the free or reduced lunch program were almost twice as

likely to fall short of the standards.

The achievement gap between minority and non-minority students may be

attributable in part to the widely held view that "natural ability, rather

than effort, explains achievement" (American's Choice: High Skills or Low

Wages, the Report of the Commission on the Skills of the American Workforce).

The impact of this "belief" is that:

we communicate to millions of students every year,

especially to low-income and minority students, that we do

not believe that they have what it takes to learn. They

then live up to our expectations, despite the evidence that

they can meet very high standards under the right

conditions. :

Meanwhile, other nations, our business competitors, point to hard work as

the road to achievement. Hard work still applies here: We do little to serve

poor children by letting down standards under the pretext of equal educational

opportunity. We serve them best by raising expectations while building

schools where they can meet these expectations.

Public Attitudes Toward Integration in Public Schools

During its deliberations, the Governor's Commission on Quality and

Integrated Education commissioned the Institute for Social Inquiry at the

University of Connecticut to conduct a public opinion survey to determine

statewide attitudes toward integration. The majority of respondents gave

generally high marks to the Connecticut public schools, and those respondents

with children in public school rated the schools even higher than those

without public school children.

When asked to list the most important factors in choosing a school, those

surveyed focused on such "quality-related" issues as the number and quality of

teachers and the breadth of programs. For example, enrichment programs

received the highest rating: they were seen as "positive" by 94 percent of

the respondents. “Small classes with individual attention from teachers"

followed closely (92 percent). In third place the respondents ranked the

value of keeping students in schools in the same town where they lived (83

percent). Issues of racial balance came fourth. Seventy percent of all

respondents rated "making sure there was a good mix of racial backgrounds" and

“having teachers from a variety of racial backgrounds" as either positive or

very positive factors. Daycare programs and early childhood education also

emerged as positive factors. Seventy percent saw before and after school

daycare as positive while 61 percent said pre-school programs would be an

attraction were they choosing a school.

The general attitude toward integration proved positive, and when asked if

more should be done “to integrate schools in your community," those in favor

(42 percent) easily outnumbered those opposed (18 percent). (The remaining 40

percent either considered no change necessary or didn't know.) There was also

strong support for doing more “to integrate schools throughout the state" with

54 percent calling for more such efforts. At the same time voluntary efforts

were favored over mandatory programs, 39 to 17 percent. The respondents also

strongly favored beginning integration efforts in the elementary schools (80

percent).

Those surveyed recognized a certain quality in integrated schools. Seven

in ten agreed that "making sure a school is racially and culturally mixed

improves the quality of education for all students". Over 60 percent agreed

that "children who go to a one-race school will be at a disadvantage when they

grow up and must live and work in our multiracial society." Two-thirds agreed

that "if more children went to racially mixed schools, we would have less of a

problem with racial prejudice".

When asked whether or not they supported "busing of minority and white

students to achieve school integration" the respondents rejected the practice

five to three, but when the survey linked the concept of quality schools to

the concept of busing, the percentage of favorable responses increased to

one-half. "Busing" clearly remains an unpopular concept.

Apparently, the public sees a distinction between busing to achieve racial

balance as one thing and integration as another, even though the terms have

often been used interchangeably. Busing and racial balance connote moving

children from school to school to achieve some numerical goal or to meet some

administrative need. Integration, on the other hand, suggests positive,

productive interaction between students of different races and cultures:

"Racial balance" does not contribute to quality education; "integration"

does. According to the survey director, "The public sees little value in

achieving numerical balance which may not help education and which treats

students as members of classes."

THE FINDINGS

Following its research into the dimensions of racial isolation in

education in Connecticut and nationally, the Commission developed the

following five findings:

(1) BEducational opportunity cannot be addressed in isolation and every

aspect of public policy in every region of the state should be linked

in the cooperative enterprise of removing barriers to achievement and

of promoting the common ground that strengthens us all as a society.

(2) A quality education requires an integrated student body and faculty

and a curriculum that reflects the heritage of many cultures.

(3) Every student can learn at high levels from a quality and integrated

education.

(4) A need exists for communities to appreciate and support public

education, and for family members and others in the community to

involve themselves in the education of Connecticut's youth.

(5) Every educator must be trained to teach both a diverse student

population and a curriculum that incorporates and honors the diverse

cultural and racial heritages.

(6) Connecticut needs to attract and employ minority educators.

For each of its findings, the Commission established a goal, indicators of

success, and recommendations for achieving the goal. Each finding is

discussed separately in the following sections of this Report.

10

FINDING 1

The Commission's first finding is that we cannot ignore the underlying

causes of isolation and inequity in our schools and hope meaningfully to

improve quality and integrated education. Meaningful action is needed in

every region of the state honestly to recognize disparities and join in a

shared effort to help ourselves by helping each other overcome the inequities

which deny us the fullest measure of our potential in our communities, regions

and State.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Commission recommends that the communities in each and every region of

the State shall join in a cooperative effort over the next year to identify

and assess present barriers such as poverty, education, employment, housing,

health and transportation which perpetuate inequity, isolation and the lack of

greater integration. Each region must then develop and commit to a

cooperative plan of community and regional action with triennial evaluation

and progress reporting.

Regions could be identified by reference to regional planning agencies or

regional educational service centers. Existing regional authorities or newly

designated regional representatives would be designated for this purpose.

State agencies, regional planning agencies and regional educational service

centers would cooperatively provide administrative support and other technical

assistance as required. Failure of any community to participate in this

. process could jeopardize some or all State funding for the community.

FINDING 2

Having concluded that a quality education requires an integrated student

body and faculty and a curriculum that reflects the heritage of many

cultures, the Commission's concomitant goal is to maximize the number of

students who receive a quality education, increasing the number who do so

significantly each year.

The integration of our young learners implies our hope for a more

harmonious new century than the one now drawing to a close. We know hatred,

prejudice, and racism when we see it, and we see it all around us. We also

know fellowship, tolerance, and mutual respect when we see it, and examples

abound in our daily lives: the widespread acceptance by young people of a

multi-ethnic culture in music, sports, and style; the absence of prejudice

among young children who come together for play or pre-school activities.

11

The Commission believes that each school's student population should

reflect the majority-minority ratio of the students in its region. The

Commission further believes that the goal of quality and integration will be

achieved when each school provides an integrated learning environment

reflected or demonstrated in most or all of the following seven ways:

(1) Educational goals and the school environment must welcome and

accommodate integrated education,

(2) The curriculum should impart an expectation that all students will

become successful learners,

(3) The curriculum, both written and informal, should be multicultural,

reflecting the heritage of many cultures,

(4) Instructional materials and library collections too must mirror the

heritage of many cultures,

(5) In appraising the education of all our children, we must use

appropriate assessments,

(6) Schools should supplement a multicultural environment with

complementary assembly programs, field trips, etc, and

(7) The school leadership must remain open and responsive to constructive

proposals from staff, parents, and their organizations.

RECOMMENDATIONS

First, the Commission recommends that the State Board of Education develop

guidelines for an integrated and multicultural school environment by June

1992. Each school district should then develop its own local standards,

consistent with State guidelines while reflecting local diversity. These

standards would identify those characteristics of the school environment that

create a multicultural school, including the content of the curriculum and the

teaching perspectives, the instructional procedures and styles, and the

general organization of the schools.

Second, the Commission recommends that the State Board of Education review

the State's racial balance law and regulations in the light of the

Commission's recommendations and the experiences of school districts

implementing the law.

Third, the Commission recommends that the State legislature create and

expand and then fund a continuum of educational experiences in the new

integrated environment. A continuum of State funding programs would allow

local school districts to formulate local integration projects that reflect

local needs and that build on local strengths. The recommended programs

follow here in outline form:

12

I. Interdistrict Transfers

The Commission recommends creation of a new Interdistrict Transfers Grant

Program. The State legislature should establish a State grant program for

interdistrict transfers based on Project Concern, but accommodating two-way

transfers. Students currently participating in Project Concern would be

"grandfathered" into the new program, which would make these seven

contributions:

(1) It would establish a separate interdistrict grant to underwrite

tuition and transportation aids (Project Concern is currently funded

through the compensatory education grant program).

(2) It would set a target for increased student participation each year

beginning with the fiscal year FY92-93.

(3) It would invite parents to apply to include their children; however,

only those children whose transfer promises to enhance the cultural

diversity of the receiving school may participate.

(4) It would allow the sending school district to continue to count the

student as part of its enrollment and pay tuition to the receiving

district. For example, tuition based on a percentage of the

district's the per pupil expenditures or a percentage of the

district's state education aid per pupil.

(5) It would require the State pay the receiving school district a grant

based on per pupil expeditures.

(6) It would require the State pay the sending school district 100

percent of the costs of transportation in excess of $400 per pupil;

the State would pay the normal aid percentage for the first $400 of

costs, and the maximum excess costs grant would be $1000 per pupil.

(7) It would require the local districts to announce the number of net

seats available for interdistrict transfers (the net equaling

incoming minus outgoing). When the number of applications exceeds

the number of seats available, districts shall use a lottery to

determine which students will attend. No screening criteria may be

applied.

II. Interdistrict Cooperative Grant

The Commission recommends expansion of the Interdistrict Cooperative

Grant. Thirty-six grant proposals were submitted for 1991-92. The proposals

involved over 100 districts and the total funding requested was $2 million.

Because of limited funding, however, only 27 programs were awarded grants, and

they received only 63 percent of the amount requested. State funding limits

forced the reduction of many of these programs, some of which are in their

third year of funding and have student waiting lists.

13

The State should limit grants under this program to activities during the

regular school year and to (a) planning for full-year programs (with a two

year limit on planning grants) or (b) short-term or part-time student

programs. Joint programs involving at least one district that has less than

15 percent minority students should receive preference, and the State

legislature should increase funding to $2 million in 1991-92 and to $3 million

in 1992-93. Over the long term, the legislature needs to provide sufficient

funding to ensure the continuation of effective programs.

III. Summer School Grant

The Commission recommends expansion of the Summer School Grant, which

served 12,000 students in 17 local programs at a total funding level of $1

million in 1990-91. The State Board of Education has requested $1 million for

1991-92. We recommend that the legislature increase funding by $1 million per

year for two years. We further recommend that the grant program be limited to

(1) interdistrict integrated programs, (2) full day programs, (3) programs

that run for at least 20 days, and (4) programs that combine remedial and

enrichment activities. The summer program should also include a follow-up

component that would allow students and teachers to reinforce understandings

and relationships they established during the summer.

IV. Pre-School Programs

The Commission recommends the creation of regional integrated pre-school

programs. The Commission's public opinion survey indicated significant

support for these programs. By a wide margin, in fact, those polled believed

that integration should begin in the elementary grades. In addition, research

into the effects of the Head Start Program documents significant gains from a

year of quality pre-school for children whose family incomes or medical status

placed the child at risk of school failure.

The Commission recommends that a special grant program be established to

fund the operation of at least three model regional integrated pre-school

programs, and it recommends that the State school construction laws be amended

to provide State aid for either the construction or renovation of buildings to

accommodate integrated pre-school programs and day care programs. All school

districts should be eligible for this aid.

V. Magnet Schools

\

The Commission recommends that school districts and parents work to ensure

that each child has an opportunity to attend an integrated regional magnet

school or to participate in an interdistrict program in a school with a

diverse student body. The Commission recommends that the State, in

partnership with local school districts, establish sufficient regional magnet

programs to guarantee space for each child who chooses to learn in an

14

integrated school. The Commission also recommends that the “State develop

standards for the operation of regional magnet schools that address, at least,

the following ten concerns:

(1) a rigorous high quality academic program,

(2) an academically diverse student body,

(3) the racial composition of the student body,

(4) the racial composition of the staff,

(5) a multi-cultural curriculum,

(6) staff training that accommodates cultural diversity,

(7) admission procedures, retention patterns, and student

discipline,

(8) community involvement in the magnet school planning,

(9) parent awareness, commitment and involvement, and

(10) participation of bilingual and special education students

The Commission recommends that the State amend the school construction

laws to provide generous funding for the construction, renovation and/or

leasing of buildings to house regional magnet schools. The Commission further

recommends that the State amend school construction laws to provide funding

for the construction, renovation or leasing of buildings for magnet schools on

both public and private college campuses.

The Commission recommends that the State Board of Education examine the

idea of establishing satellite elementary magnet schools on the sites of large

businesses. It also recommends that school districts form regional

partnerships to plan and operate magnet schools, that the regional education

service centers assume responsibility for the structure and support of these

regional planning efforts, and that the State help underwrite the planning and

operating of these magnet schools. The public opinion poll showed strong

support for integration at the elementary level.

The Commission's study of school expansion and replacement needs revealed

a pending need for substantial elementary school construction in Bridgeport,

Hartford, New Haven, New London and Stamford-Norwalk areas. There appears,

however, to be no widespread need for new middle and high school classrooms.

Meanwhile, the need for new elementary classroom space presents an Spportunity

for the establishment of regional magnet schools.

The Commission recommends that the State Board of Education instruct the

Educational Equity Study Committee to develop specific legislative proposals

for entitlement grants to fund these regional magnet schools while

incorporating the concept of State and regional partnership. The Equity

Committee should address (1) school construction grants, (2) magnet planning

grants, (3) operating grants for the extra costs of magnet schools, and (4)

transportation grants. The Commission recommends that the State Board of

Education ask the Educational Equity Study Committee to develop a grant

program to assist districts with more than 25% minority students to develop

and implement intradistrict magnet schools.

The Equity Committee should also develop specific legislative proposals

for the new interdistrict transfer grant and the pre-school grant and related

changes in the school construction laws and regulations. The Equity Committee

should begin meeting in the Spring of 1991 and transmit a preliminary report

to the State Board of Education by January 1992.

15

Fr A Ear ie ee A move 4 ” ET Be ed of dX Wr S25 Se a a

VI. State Vocational Technical Schools

The Commission recommends that the State expand the outreach programs of

its vocational-technical schools. To ensure that the State's existing

regional magnet school system, the regional vocational-technical schools,

remain a model of diversity in staff, students, and curriculum, the Commission

recommends that the State fund special outreach programs targeted to currently

underrepresented groups. The Commission further recommends that the State

expand the seventh grade summer exploratory programs and target currently

underrepresented groups. The Commission recommends funding for these

proposals for Fiscal Year 1991-92 at $300,000.

VII. Technology for Integration

The Commission recommends the use of technology such as computer

networking, interactive television, and distance learning to foster links

between urban and suburban districts and between urban and rural districts.

VIII. Non-Traditional Approaches:

Recognizing that traditional solutions may only yield traditional results,

the Commission recommends that the State determine the desirability of

establishing non-traditional approaches to achieving integration.

IX. Priority School District Grant

The Commission recommends that the State significantly increase funding

for the Priority School District programs.

FINDING 3

The Commission's third finding is that all students can learn at high

levels with a quality and integrated education. The goal for each school in

Connecticut is to maximize each and every student's learning so as to help all

students become productive and responsible members of a pluralistic society.

We will have achieved this goal when

(1) A student's achievement is no longer affected by such irrelevant

factors as race, ethnicity, gender, residence, and wealth;

(2) These irrelevant factors no longer limit a student's access to

educational programs;

(3) Each school offers appropriate educational opportunities to maximize

student learning;

16

(4) all students graduate with an education best preparing them to be a

productive, responsible, and effective adult; and

(5) all students are exposed to both cognitive and experiential education

ensuring their understanding of and appreciation for our society's

racial, ethnic and cultural diversity.

This goal agrees with those in several other recent reports and with the

first goal of the National Governor's Association: "By the year 2000 all

children will start school ready to learn." The report goes on to say that

In preparing young people to start school, both the federal

and state governments have important roles to play,

especially with regard to health, nutrition, and early

childhood development. The Federal Government should work

with the states to develop and fully fund early

intervention strategies for children. All eligible

children should have access to Head Start, Chapter One, or

some other successful preschool program with strong

parental involvement. Our first priority must be to

provide at least one year of preschool for all

- disadvantaged children.

In support of its goal the National Governor's Association developed the

following three objectives:

“(1) All disadvantaged and disabled children will have access to high

quality and developmentally appropriate preschool programs that help

prepare children for school.

(2) Every parent in America will be a child's first teacher and devote

time each day helping his or her preschool child learn; parents will

have access to the training and support they need.

(3) Children will receive the nutrition and health care needed to arrive

at school with healthy minds and bodies, and the number of low

birthweight babies will be significantly reduced through enhanced

prenatal health systems."

17

RECOMMENDATIONS

First, the Commission agrees that a strong beginning is critical to

success in school, and to ensure that all students come to school ready to

learn, the Commission recommends that school districts, in cooperation with

appropriate State and local agencies:

(1) provide through the appropriate health department staff,

preventive health care programs at all schools where there is a

significant percentage of low income students;

(2) provide school breakfast and school lunch programs in all

schools with a significant percentage of low income students; and

(3) provide at least one year of preschool for all at-risk students.

Second, given these concerns, the Commission recommends that the State

work with local school districts to develop and promote alternatives to

tracking and ability grouping.

Third, to ensure that all districts provide the appropriate range of

programs and maintain appropriate class sizes, the Commission recommends that

the Educational Equity Study Committee review current state aid programs to

ensure that these programs favor those schools and districts with the greatest

financial needs and those students with the greatest educational needs. The

range of educational programs at a school or district must be sufficiently

broad, deep, and diverse to maximize and enrich the education of every

student. Class size and student faculty ratios should, moreover, reflect

educational policy rather than the limits of school or district wealth. The

Educational Equity Study Committee should report its finding and proposed

legislation to the State Board of Education by January 1992.

Fourth, to improve the effectiveness of our educational system and

encourage all students to learn at the highest levels possible, the Commission

supports (1) current State efforts to restructure its testing programs to

include more performance assessments, including items based on the Common Core

of Learning; and (2) State and local school district plans to report annually

on students and educational outcomes by school and district. :

18

FINDING 4

The Commission's fourth finding is the need for our local communities and

the State to appreciate and support public education and for family members

and other community members to increase their involvement in the education of

Connecticut's youth. The Commission is disturbed by an apparent erosion of

community support for public education in recent years, and it formulated two

goals in response to this concern:

(1) Communities must come to understand the full value of public

education in our society and economy and actively support it.

(2) All adult family members and other community members must increase

their involvement in the education of Connecticut's youth.

The Commission suggests that educators, parents, community and business

leaders all have a role to play in communicating to our children, in

particular, and to the entire community, the critical importance of getting

the best education possible. Those who would remain competitive in the global

economy require a well-educated work force: “No nation has produced a highly

qualified work force without first providing its workers with a strong general

education". We will have achieved these two goals when:

(1) the State, the cities, the school districts, and the whole community

recognize the necessity of an educated population and work

cooperatively to support public education;

(2) parents and guardians (a) adequately prepare their children for

school (that is, make certain they are housed, are clothed, and

maintain good health practices); (b) emphasize the importance of

education and maintain a positive attitude toward school; (c) follow

their children's progress in school by attending school orientation,

information and training sessions; and

(3) each school offers an outreach program designed to involve all

members of the community. : :

RECOMMENDATIONS

First, the Commission recommends that local school districts, in concert

with parents and community and business leaders, develop long-term educational

outcomes for their students. The community should also specify those

education skills they consider essential for their community.

Second, the Commission recommends that local school districts and

community leaders work together to develop an information program that

promotes a clearer understanding of the strong direct connection between a

well-educated work force and a competitive economy.

19

Third, the Commission recommends that parents and educators work closely

together to keep all students engaged in a rigorous program of learning from

the elementary grades through the high school years. Such a partnership is

critical if we are to ensure that all children are prepared to meet the

challenges of the 21st century.

Fourth, to help parents become effective partners with teachers in .

supporting and monitoring their children's educational programs, the

Commission recommends that parents and educators together plan and implement a

program of parent orientation and training. The purpose of these programs

would be (1) to inform parents about their children's program of studies, and

(2) to share with parents the latest and best information on how children

learn and how parents can help their children learn. The Commission

recommends that schools and parents set goals for parent involvement in their

children's education.

Fifth, working with the larger community, the Commission recommends that

local school districts develop outreach programs to encourage local

businesses, community agencies (for example, the social service centers, day

care centers, and churches), and the elderly to become involved in their

community's schools.

(1) by contributing financially to school activities, to such

complementary educational resources as libraries:

(2) by becoming tutors, oral historians, instructors or helpers in school

activities, either during the regular school day or as part of the

after-school or seasonal activities;

(3) by visiting classrooms and illustrating for students the skills

required in a particular line of business--holding out the hope,

meanwhile, that a child may gain employment in that business with the

appropriate educational preparation; and

(4) in every case possible, encourage local businesses to hire and train

neighborhood students for either summer or year-round positions.

20

FINDING 5

The Commission's fifth finding is that Connecticut educators must be

trained to teach both a diverse student population and a curriculum that

incorporates the heritages of diverse cultural and racial groups. Our goal

must be to familiarize our teachers with the skills and knowledge necessary

for teaching a diverse student population and curricula that embrace

multicultural understanding.

Most of us are brought up conditioned to be ethnocentric, to believe that

our culture is both different and better. This is particularly true when a

cultural group lives in relative isolation. Our country has been strengthened

from the first by cultural differences and is becoming ever more diverse. All

‘humankind, in fact, now lives in a world where groups are becoming

increasingly interrelated, less and less isolated. Accordingly, we must all

learn about other cultures.

As our most valuable human investment, children, most of all, deserve a

strong foundation of ethnic diversity and cultural pluralism throughout the

curriculum. Cultural pluralism means that each person, regardless of group

identification, enjoys an inherent claim to respect, dignity and rights.

Cultural pluralism also implies that no one cultural style enjoys an inherent

precedence over another. Our country and our state then act unfairly by

imposing a curriculum in language arts, history and the arts that

disproportionately reflects a white, European culture. Nevertheless, A Study

of Book-Length Works Taught in High School English Courses found that:

“A summary of the titles required by 30 percent or more of the public

schools compares the results in 1988 with those 25 years earlier. Of the

27 titles that appear in 30 percent or more of the schools, 4 are by

Shakespeare, 3 by Steinbeck, and 2 each by Twain and Dickens. Only two

women appear on the list--Harper Lee and Anne Frank-- and there are no

minority authors."

The author concludes that there are "...fundamental questions about the nature

of the literary and cultural experiences that students should share, as well

as the degree of differentiation that is necessary if all students are to be

able to claim a place and an identity within the works that they read. The

debates also involve fundamental pedagogical questions about the most

effective means to help all students develop an appreciation for and

competence in the reading of literature."

As our nation becomes more culturally diverse and the need grows for our

people to appreciate and understand different cultures, educators must develop

learning experiences and environments that preserve and illustrate, with a

sense of gratefulness and appreciation, each group's contribution to the

richness of the entire society.

An amalgamation of approaches--enhancing, for example, the teacher

preparation programs, eliminating materials that contain bias, supportive

administrators, integrating the entire curriculum, and ongoing programs that

promote interaction among students--would strengthen and enliven our school

system and encourage it to serve all of our students beneficially and equally.

21

But such a fundamental change in our public school curriculum requires a

concomitant change in teacher preparation. The Commission concludes,

therefore, we will have achieved this goal only when each educator has been

trained to teach both a diverse student population and a curriculum that

incorporates the heritages of diverse cultural and racial groups.

RECOMMENDATIONS

First of all, we must change our teacher preparation programs to include

the following six training elements:

(1) Future teachers must acquire the skills to effectively teach in a

diverse student environment. All teacher preparation programs

should require a comprehensive urban teaching experience.

(2) Future teachers must be able to develop and teach a multicultural

curriculum, and teacher preparation programs should require a course

of study in multicultural education.

(3) To attain an appreciation for cultures other than their own,

teachers should become proficient in a second language. Programs

should include the study of the language itself, the history,

literature and culture of our country.

(4) Immersion being the smoothest path to understanding a different

culture, teacher preparation programs should encourage foreign

exchange programs.

(5) The Permanent Advisory Council on the Teaching Profession should

prepare now to incorporate multicultural education into the

certification and recertification regulations.

(6) The current certification regulations should be revised to reflect

the new teacher preparation requirements for a student exchange

experience, a second language proficiency, courses on student

diversity and the multicultural curriculum.

Second, educators already in the work force must enjoy the same

opportunity for training as the individuals in teacher preparation programs.

Accordingly, the Commission recommends that (a) the Connecticut Department of

Education use funding and regulations to encourage multicultural education

training for all professional educators; (b) with its Celebration of

Excellence program as a model, the Department of Education fund exemplary

curriculum projects which incorporate diversity and educate about prejudice;

and (c) the teacher preparation programs centers in the Connecticut State

University system be used to develop the programs recommended.

22

Third, additional funding should be made available to implement the

following three programs:

(1) Institutions of higher education should hire faculty members with

experience in developing multicultural curriculum for its teacher

preparation programs.

(2) Institutions of higher education should plan a series of workshops

designed to incorporate the multicultural curriculum concept into

the professional development experience of all teachers.

(3) Institutions of higher education should provide teacher and student

exchange grants and establish a study abroad center for students in

teacher preparation programs.

As we do so often when our society faces problems, again we ask our

schools to address the issue within our children's educational experiences.

The concern this time is for cultural diversity; the request this time,

however, is fraught with complexity and emotion. Multicultural education

already exists, at least rhetorically; but the Commission can find few

examples of it flourishing in the classroom. Several studies confirm that the

principle requirement for the success of this type of program is teacher

awareness. Slavin states, "to train teachers to foster interracial

interaction, teacher workshops should be focused not on understanding

intergroup relations, but on specific teaching methods that that promote

student interaction."

Fourth, the Commission recommends that centers be established at which

teachers and administrators would be able to satisfy their professional

development requirements (continuing education units - CEUs) by participating

in workshops. Centers would be funded by a State grant.

23

FINDING 6

The Commission found that there are too few minority educators in the

State of Connecticut, and its recommended goal is for the State to begin

immediately to increase the number of minority educators.

Today, only 6 percent of the 37,000 full-time professional staff in the

State's public schools are members of minority groups. One hundred and one

districts (61%) have less than one percent minority staff. Sixty-five of

these districts have no minority teaching staff. Of particular concern is the

low number of minority professionals in the area of special education as

reflected in A Plan to Increase Minority Participation At All Levels in the

Special Education Profession.

Meanwhile, minority boys and girls comprise almost 25% of the student

population, and projections indicate that as the minority student population

increases, the number of minority teachers will decrease. Too rarely do

minority youngsters find the adult role models they need in their school

buildings. But white students miss out too. If we want to inculcate in our

children the value and importance of diversity, the lesson must start in the

classroom. In addition, the low number of minority teachers deprives the

profession itself of the valuable enrichment that comes from a diverse mix of

teachers and administrators and their approaches to issues in instruction and

curriculum. However, if we take no steps to reverse the trend, by 2020 "the

average child will have only two minority teachers--out of about 40--during

his or her Kindergarten through twelve school years. And this

under-representation will be worse at the college level."

But how. can we as a State reverse these trends? The Commission finds that

minority graduation rates from four-year institutions remain

disproportionately low, and some questions follow from this fact: how can we

increase the numbers of minority people entering and graduating from our

colleges and universities when they meet fewer and fewer college educated

minorities in their earlier schooling? How can we attract minorities into the

profession of teaching when they can find fewer and fewer minority colleagues

there? And, how do we retain those who enter the teaching profession when

other professions actively beckon?

The key is to put in place a comprehensive, thoroughly integrated State

plan involving the entire education system. The Commission will consider the

goal achieved when each school district has an integrated faculty. The

objectives will require Connecticut to (a) increase the number of minorities

graduating from teacher preparation programs in the State; (b) recruit

minority teachers from out-of-state; (c) retain minority teachers in the

profession; and (d) regionalize the recruitment and retention of minority

teachers.

24

RECOMMENDATIONS

First, we absolutely must increase the number of minorities graduating

from teacher preparation programs in the State of Connecticut. The Department

of Higher Education has initiated a program to recruit and retain minorities

in higher education throughout the State, and although we appear to be doing

better, an under-representation of minority students persists in four-year

institutions generally and in teacher preparation programs specifically. To

increase the latter, we must increase the former. It is as simple as that.

To attract Connecticut's young minority students to Connecticut colleges and

universities, the State should, in the Commission's view, adopt the following

six strategies:

(1) Identify minority teachers to serve as role models who agree to work

with interested minority students in selected districts. These

teachers would serve as mentors, providing their students with

guidance and leadership as they prepare to enter college.

(2) Work with such other programs as Career Beginnings, CONNCAP, Upward

Bound and Day of Pride to guide minority students toward higher

education. The Connecticut Collegiate Awareness Program (CONNCAP)

and Upward Bound are consortia between a college and a local school

system that identify junior high school minority students who

demonstrate college potential. The programs provide support and

enrichment opportunities to students in anticipation of college.

These programs convince young students with academic ability that

they can succeed in college. CONNCAP provides academic enrichment

and exposes students to a campus -environment. A number of similar

programs already exist, and they should all be encouraged and

expanded.

(3) Establish among parents a positive impression of teaching as a

profession. Parents have a strong influence on a student's

schooling and career choice, and part of any student program should

be a segment for parents.

(4) Encourage partnerships between selected school districts and nearby

colleges to help minority students continue on to college and

succeed. After establishing a formal association between its high

schools and higher education, the State should also make sure the

students receive individual attention at the time of their admission

and enrollment.

(5) Establish a minority scholarship program to ensure that academically