Brief Amicus Curiae of Civil Liberties Union in Support of Appellants

Public Court Documents

1998

43 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Brief Amicus Curiae of Civil Liberties Union in Support of Appellants, 1998. 28df0ebb-d90e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/f24826df-342f-4fcc-aeb6-94fcdad4945b/brief-amicus-curiae-of-civil-liberties-union-in-support-of-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

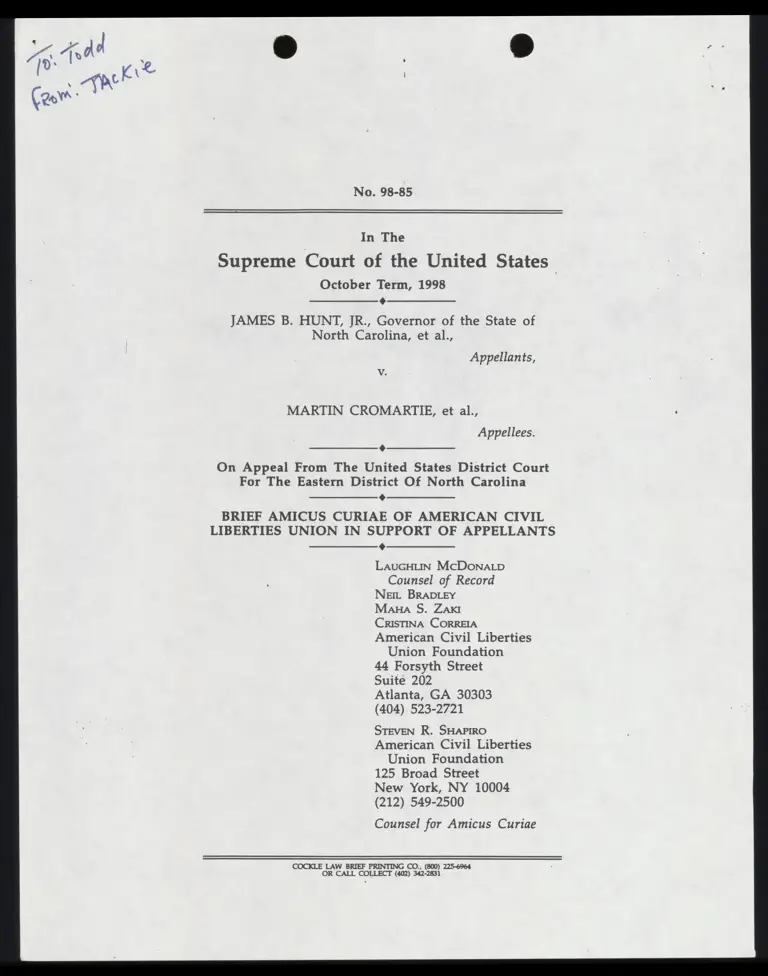

No. 98-85

In The

Supreme Court of the United States |

October Term, 1998

&

v

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., Governor of the State of

North Carolina, et al.,

Appellants,

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al,

Appellees.

4

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District Of North Carolina

*

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF AMERICAN CIVIL

LIBERTIES UNION IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS

¢

LaugHLIN McDoNALD

Counsel of Record

NEIL BRADLEY

MAHA S. Zaki

CrisTINA CORREIA

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

44 Forsyth Street

Suite 202

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-2721

SteveN R. SHAPIRO

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

125 Broad Street

New York, NY 10004

(212) 549-2500

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES . .... ia = ii

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT. ........0 nuh. 1

ARGUMENT: i. 5 ei Than J te pei 3

LaIntvoducHon. . .. one at ss ii ens 3

II. The Voting Rights Act and the Importance of

Majority-Minority Districts ................ 4

III. Challenges to the Voting Rights Act....... 7

IV. Majority White and Majority Nonwhite Dis-

tricts; Dual Standards .......... 08. oo. 11

V. Mistaken Assumptions about Segregation... 18

VI. The Comparison with Affirmative Action.. 22

VII. The Shaw /Miller Standards Are Unwork-

BIB. os sR 25

VIII. The Significance of Black Victories in 1996... 27

CONCLUSION on. cal i ide a 30

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Casts:

Abrams v. Johnson, Nos. 95-1425 & 95-1460 ......... 28

Abrams v. Johnson, 117 S.Ct. 1925 (1997)

a BL NI BGRY 1, 3,10, 12,17, 27

(1995), do i oy EL Ne EE 23

Allen v. Wright, 468 US. 737 (1984). ........ ........ 15

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Devel-

opment Corp..429 U.S. 252 (1977)... . 5c... 16, 17

Burton v. Sheheen, 793 F.Supp. 1329 (D.S.C. 1992) ..... 6

Busbee v. Smith, 549 F.Supp. 494 (D.D.C. 1982)....6, 23

Bush v. Vera, 116 S.Ct. 1941 (1996)...... 3, 4, 10, 13, 25

Chapman v. Meier, 420 US. 1 (1975) ................ 26

City of Memphis v. Greene, 451 U.S. 100 (1981)..... 17

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) ..... 17,22

City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson, Co., 488 U.S. 469

100 EAR TN Sh AIR SSI Tae A 23

Currie v. Foster, No. 97-CV-368 (W.D.La.) ............ 8

Daly v. High, No. 5:96 CV 86-V (W.D.N.C)).......... 8

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986)... 5... on 7.22

DeGrandy v. Wetherell, 794 F.Supp. 1076 (N.D.

Fla," 1992) ... 5 .. 5% Go ER PRRLTI \ p 6

DeWitt v. Wilson, 115 S.Ct. 2637 (1995).............. 11

Diaz v. Silver, 932 F.Supp. 462 (E.D.N.Y. 1996). ....... 5

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Diaz v. Silver, CV-95-2591 (E.D.N.Y. Feb. 26, 1997) ....:.11

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973)........... 13

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) .......... 12

Growe v. Emison, 507 U.S. 25 1993). . ih. 26

Hays v. Louisiana, 839 F.Supp. 1188 (W.D. La.

1993): ne ee SB Bs 6, 8

Hays v. Louisiana, 862 F.Supp. 119 (W.D.La. 1994) .... 21

Hays v. Louisiana, 936 F.Supp. 360 (W.D.La. 1996) .... 10

Holder v.. Hall, 312 U.S.:874 (1994). .. ....... 050k ius 1

Johnson v. Miller, 864 F.Supp. 1354 (S.D.Ga. 1994)

IRS a LP ai, oom se ie

Johnson v. Miller, 922 ESupp. 1552 (S.D.Ga. 1995). ..14, 20

Johnson v. Miller, 929 F.Supp. 1529 (S.D.Ga. 1996) ..... 8

Johnson v. Mortham, 926 F.Supp. 1460 (N.D.Fla.

1996). AE CA Ea a Te iE 8, 10

Jordan v. Winter, 604 F.Supp. 807 (N.D. Miss. 1984) ..... 6

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966).......... 21

King v. State Board of Elections, 979 F.Supp. 582

ANLD.IN. 1996) ec chin esti i id ait 8

King v. Illinois Board of Election, 118 S.Ct. 877

(1998). cis. a ei BAL RE 11

Kusper v. Pontikes, 414 U.S. 31 (1973) w.... oan. 2. 11

Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 117 S.Ct. 2186

(1997)... nu Fe NR Say ABE hr Ld 11

Leonard v. Beasley, Civ. No. 3:96-CV-3540 (D.S.C.)..... 8

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555 (1992) .... 14

Major v. Treen, 574 F.Supp. 325 (E.D.La. 1983)........ 6

McCain v. Lybrand, 465 U.S. 236 (1984)... . i. 05 1

Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. 2475 (1095). , Ja... passim

Moon v. Meadows, 952 F.Supp. 1141 (E.D.Va. 1997) ..8, 10

NAACP v. Button, 371 US. 415 (1963) ...... ous i 11

Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v.

Feeney, 442 US, 256 (1979) ....... 05.0 hs 16, 17

Quilter v. Voinovich, 912 F.Supp. 1006 (N.D.Oh.

50) 3 SRR tC Nat Cea eR eae 8

Quilter v. Voinovich, 981 F.Supp. 1032 (N.D.Oh.

0 SREY OR TIER aa Ciel Seas Tae 11

Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board, 117 S.Ct.

IA HAST). re dD hE aia a 1

Rice v. Smith, CA No. 97-A-715-E M.D.Ala). ou 8

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 US. 613 (1982)................. 5

Scott v. U.S. Dept. of Justice, 920 F.Supp. 1248

(IMD.Fla. 1996) . isi... oo hamaidon vy Sata 8

Shaw v. Barr, 808 F.Supp. 461 (E.D.N.C. 1992)...... 6, 8

Shaw v. Hunt, 116 S.Ct. 1894 (1996)... ............ 3, 10

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 620 (1993) oo a passim

Smith v. Beasley, 946 F.Supp. 1174 (D.S.C. 1996)... ... 8

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966)

Py pee ie a a iw ve 8, 19, 21

Vv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

The Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall) 36

(1873). soa dpa in hia dah A ni 18

Thomas v. Bush, No. A-95-CA 18655 (W.D.Tex:) ...... 8

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) .......... 5, 18

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburg, Inc.

v.:Carey, 430 US, 144 (1977)... ston i 5 iin cia 22,23

United States v. Hays, 115 S.Ct. 2431 (1995).......... 1

United States v. Scott, 437 U.S. 82 (1978)............. 4

United States v. Students Challenging Regulatory

Agency Procedures, 412 U.S. 669 (1973)........... 16

Vera v. Richards, 861 F.Supp. 1304 (S.D.Tex. 1994)

EURO SE leds VE anon a 6,8, 13

Washington v. Davis. 426 U.S. 229 (1976). .......... 17

Wesch v. Hunt, 785 F.Supp. 1491 (S.D. Ala.).......... 6

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Ed., 476 U.S. 267

(I9BB) cc cal hs i cs eT a RE 23

ConsTiITuTIONAL PROVISIONS:

Fourteenth Amendment. ......o....0 0005. 00 passim

Fifteenth Amendment............. 0000 8 ans, 21

STATUTORY PROVISIONS: :

Civil Rights Act of 1957... 0nd i 9

Civil Rights Act of 1960... coc... ii iu, 9

Civil Rights Actof 1964......0...... oi. a 9

Voting Rights Act of JOGh ET ie me 1, 3, 9

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

42 US.C.'§ 1973, Section 2... oiaitiis, bu dm 3,5

42 U.S.C. § 1973¢°Section BD. ..c. oo oF. Bat 5

CONGRESSIONAL REPORTS:

S.Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982).......... 20

Voting Rights Act: Hearings Before the Subcomm.

on the Constitution of the Senate Comm. on the

Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 662 (1982)... ...=.. 20

Ruts:

S.Ct. Rule 373... 0... 00 or a er Bag ht 1

OTHER:

T. Alexander Aleinikoff & Samuel Issacharoff,

“Race and Redistricting: Drawing Constitu-

tional Lines After Shaw v. Reno,” 92 Mich. L.

Rev. 588 (1993)... ut rr ul ac Oo as 26

Michael Barone & Grant Ujifusa, The Almanac of

American Politics 1974 (1973)... 0. . C. iteiis u oo 7

James U. Blacksher, “Dred Scott’s Unwon Free-

dom: The Redistricting Cases As Badges of

Slavery,” 39 How. L. J. 633 (1996) ................. 24

David A. Bositis, Redistricting and Representa-

tion: The Creation of Majority-Minority Dis-

tricts and the Evolving Party System in the

South (Joint Center for Political and .Economic

Studies, 1995)... ..a.o- CmiE], uo ae ye 7, 19

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

David A. Bositis, “The future of majority-minority

districts and black and Hispanic legislative rep-

resentation,” in Redistricting and Minority Rep-

resentation (Bositis ed., 1998) .................. 28, 29

Congressional Quarterly, Inc., Politics in America

1994: 103rd Congress (Phil Duncan ed., 1993) ..... 12

Critical Race Theory: The Concept of “Race” in

Natural and Social Science (E. Nathaniel Gates

Md NR i a SS aa a 19

Armand Derfner, “Racial Discrimination and the

Right to Vote,” 26 Vand. L. Rev. 523 1073) .......0. 8

Robert G. Dixon, Jr; Democratic Representation:

Reapportionment in Law and Politics (1968) ....... 7

Nathan Glazer, “Reflections on Citizenship and

Diversity,” in Diversity and Citizenship: Redis-

covering American Nationhood (Gary J]. Jacob-

sohn & Susan Dunn eds., 1996)................... 19

Bernard Grofman & Lisa Handley, “1990s Issues in

Voting Rights,” 65 Miss. L. J. 205 (1995) .......... 26

Lisa Handley & Bernard Grofman, “The Impact of

the Voting Rights Act on Minority Representa-

tion: Black Officeholding in Southern State Leg-

islatures and Congressional Delegations” in

Quiet Revolution in the South (C. Davidson &

B..Grofmanceds., 1994) .... A... 00 0h sh rs 6

A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr., Gregory A. Clarick &

Marcella David, “Shaw v. Reno: A Mirage of

Good Intentions with Devastating Racial Conse-

quences,” 62 Ford. L. Rev. 1593 (1994). 5 ......... 9

viii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies,

Black Elected Officials: A National Roster (1993)

Pamela S. Karlan, “All Over the Map: The

Supreme Court’s Voting Rights Trilogy,” 1993

Sup..Ct. Rev. 245......0 as... 0 a

J. Morgan Kousser, The Shaping of Southern Poli-

tics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment

of the One-Part South, 1880-1910 (1974).......

J. Morgan Kousser, “Shaw v. Reno and the Real

World of Redistricting and Representation,” 26

Rut. L..J. 625 A995)... 0 connie. i

Paul Lewinson, Race, Class, and Party: A History

of Negro Suffrage and White Politics in the

South (1932).%.5-........... 3.3. Se Ne a

Cynthia A. McKinney, “A Product of The Voting

Rights Act,” The Washington Post, Nov. 26,

1996, p. ALB: 5 hans Ln Sa i Cn

Frank R. Parker, Black Votes Count (1987).......

Frank R. Parker, “The Constitutionality of Racial

Redistricting: A Critique of Shaw v. Reno,” 3 D.

Col. L. Rev. 1(1998).. .......45 .. ou alos 15,.22, 26

Richard H. Pildes, “The Politics of Race,” 108

Hatv. L.-Rev. 185941995)... . co iv. vin isis

Quiet Revolution in the South (C. Davidson & B.

Grolman-eds., 1994)... 0.00 Gi lipd a

Mark Sherman, “Redrawn Districts Expected To

Face Challenge,” Atlanta Journal & Constitu-

Hon, Aug. 2, 1995, pb. Bb... 0 coca viii

1X

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

1990 U.S. Census, Population and Housing Profile,

Congressional Districts of the 103rd Congress,

C.O. Weekly Report, V. 51, 3473-87... ........ ..xs 7

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Political Partici-

PAUHON (1968). ....c vii tah’ iit die den iss Sadi din 4

Bill Wasson, “Wilder Plan Expected to Win

Assembly OK,” The Richmond News Leader,

Dec. 3, 1991, Polis eiiniiisits vibe san. 6

www?2.state.ga.us/elections/federal.htm ............. 28

1

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE!

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a

nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with

nearly 300,000 members dedicated to defending the prin-

ciples of liberty and equality embodied in the Constitu-

tion and this nation’s civil rights laws. As part of that

commitment, the ACLU has been active in defending the

equal right of racial and other minorities to participate in

the electoral process. Specifically, the ACLU has partici-

pated in numerous voting cases before this Court, both as

direct counsel, e.g., McCain v. Lybrand, 465 U.S. 236 (1984),

Holder v. Hall, 512 U.S. 874 (1994), Abrams v. Johnson, 117

S.Ct. 1925 (1997), and as amicus curiae, e.g., United States v.

Hays, 115 S.Ct. 2431 (1995), Reno v. Bossier Parish School

Board, 117 S.Ct. 1491 (1997).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Amicus respectfully suggests that this case offers an

appropriate occasion for the Court to reconsider its redis-

tricting cases that began with Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 620

(1993). Majority-minority districts, which have been sys-

tematically challenged in the wake of Shaw, have been the

key to the increase in black office holding since passage

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. By creating lenient

standing rules for white voters and relieving them of the

obligation to show that majority-minority districts have

I Letters of consent to the filing of this brief have been

lodged with the Clerk of the Court pursuant to Rule 37.3. This

brief was not authored in whole or in part by counsel for a party

and no person or entity, other than the amicus curiae, its

members, or its counsel, made a monetary contribution to the

preparation or submission of this brief.

2

been drawn for a discriminatory purpose, Shaw and its

progeny have transformed the Fourteenth Amendment

from a law designed to prohibit discrimination against

racial minorities to one that can now be used to dismantle

majority-minority districts and allow whites once again

to maximize their control of the electoral process.

The majority-minority districts created after the 1990

census were the most racially integrated districts in the

country. Not only have they not caused segregation or

other harm, but they have ameliorated to some extent the

affliction of racial bloc voting and have thus bestowed a

benefit upon the electorate and society as a whole.

In requiring strict scrutiny of majority-minority dis-

tricts, the Shaw cases have singled nonwhites out for

special, discriminatory treatment in the redistricting pro-

cess. While whites are acknowledged to have a constitu-

tionally protected right to organize politically, the

comparable efforts of nonwhites alone are deemed consti-

tutionally suspect. Such a result violates the concept of

equal treatment under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Experience has shown that, contrary to this Court's

intent, the Shaw standards, have proven both unworkable

and unfair. Legislators no longer know when the consid-

eration of race in redistricting is required, permissible, or

impermissible. Because of the absence of clear and reli-

able standards, the federal courts have been drawn

increasingly and unnecessarily into the redistricting pro-

cess.

The decision below should be reversed because

plaintiffs failed to prove a cognizable injury and that the

legislature acted with a discriminatory purpose. To the

extent that Shaw v. Reno and its progeny are inconsistent

3

with reversal, those decisions should be reconsidered and

reversed.

ARGUMENT

I. Introduction

This case provides the Court with an opportunity to

reconsider its line of redistricting cases that began with

Shaw v. Reno.2 As described more fully below, the Shaw

cases have created legal and political confusion. Legisla-

tors no longer know the extent to which race can or

should be taken into account in drawing district lines.

The result of that confusion has been to draw the federal

courts increasingly, and unnecessarily, into the redistrict-

ing process. Shaw and its progeny have also created rules

that give special preferences to whites and shackle racial

minorities with special disadvantages in redistricting.

Five years after Shaw we are witnessing a systematic

attack on majority-minority districts, which threatens to

erode the gains in minority political participation so

laboriously accumulated since passage of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 et seq.

This Court has acknowledged that states may legit-

imately consider race in redistricting for a variety of

reasons — to overcome the effects of prior and continuing

discrimination, to comply with the Fourteenth Amend-

ment and the Voting Rights Act, or simply to recognize

communities that have a particular racial or ethnic

makeup to account for their common, shared interests.

2 The cases following Shaw are Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct.

2475 (1995), Shaw v. Hunt, 116 S.Ct. 1894 (1996), Bush v. Vera,

116 S.Ct. 1941 (1996), and Abrams v. Johnson, 117 S.Ct. 1925

(1997). 7

4

Amicus submits that, prior to the millennium census and

the next round of redistricting, the Court should frankly

admit that the Shaw cases demand reconsideration, and

that federal judicial intrusion in redistricting is warranted

only when the creation of majority-minority districts

causes cognizable harm, such as the denial or abridgment

of the right to vote or participate equally in the electoral

process.3

II. The Voting Rights Act and the Importance of

Majority- Minority Districts

On the eve of passage of the Voting Rights Act there

were fewer than 100 black elected officials in the entire 11

states of the Old Confederacy. U.S. Commission on Civil

Rights, Political Participation 15 (1968). By January, 1993

the number had increased to 4,924. Joint Center for Politi-

cal and Economic Studies, Black Elected Officials: A

National Roster xxiii (1993).4 This increase was caused

primarily by the creation of majority-minority districts

pursuant to the preclearance provisions of Section 5 of

3 Two members of the Court have stated or implied that

they would abandon Shaw. See Bush v. Vera, 116 S.Ct. at 1975 (“1

would return to the well-traveled path that we left in Shaw 1”)

(Stevens, J., dissenting); id. at 2011 (“while I take the commands

of stare decisis very seriously, the problems with Shaw and its

progeny are themselves very serious”) (Souter, J., dissenting).

Where “the lessons of experience” have shown a decision to be

wrong or unworkable, the Court has not hesitated to overrule it.

United States v. Scott, 437 U.S. 82, 101 (1978).

* This is not to suggest, however, that blacks in the South

hold office in anything approaching their percent of the

population. While blacks are 19.2% of the region’s population,

they are only 6.1% of its elected officials. National Roster at 1, 39,

93, 105, 175, 237, 319, 377, 399, 409, 439.

5

the Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c, and the vote dilution provi-

sions of Section 2 of the Act, 42 US.C. § 1973.5 Any

doubts in that regard were effectively eliminated by pub-

lication of Quiet Revolution in the South (C. Davidson & B.

Grofman eds., 1994), the most comprehensive, systematic

study ever undertaken of the Voting Rights Act.6 In par-

ticular, that study supports three critical findings:

First, the increase in the number of blacks

elected to office in the South is a product of the

increase in the number of majority-black dis-

tricts and not of blacks winning in majority-

white districts. Second, even today black popu-

lations well above 50 percent appear necessary

if blacks are to have a realistic opportunity to

elect representatives of their choice in the South.

Third, the increase in the number of black dis-

tricts in the South is primarily the result not of

redistricting changes based on population shifts

as reflected in the decennial census but, rather,

of those required by the Voting Rights Act.

> This Court has recognized the tendency of at-large

elections to submerge or dilute the voting strength of cohesive

minority communities “by permitting the political majority to

elect all representatives of the district.” Rogers v. Lodge, 458

U.S. 613, 616 (1982). The use of majority-minority districts has

been an obvious, and successful, way of countering the

debilitating effects of at-large bloc voting by the majority.

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50 (1986).

6 Quiet Revolution was a collaborative effort by 27 political

scientists, historians, and lawyers funded by the National

Science Foundation. According to Professor Richard Pildes,

Quiet Revolution is “[u]tterly free of ideological cant . . . [and]

presents the most sober, comprehensive, and significant

empirical study of the precise effects of the VRA ever

undertaken.” Richard H. Pildes, “The Politics of Race,” 108

Harv. L. Rev. 1359, 1362 (1995).

6

Lisa Handley & Bernard Grofman, “The Impact of the

Voting Rights Act on Minority Representation: Black

Officeholding in Southern State Legislatures and Con-

gressional Delegations” in Quiet Revolution at 335-36.

The impact of the Act has been particularly visible

and dramatic at the congressional level. Fifteen new

majority-minority congressional districts were created in

the South in the 1980s and 1990s as a result of litigation,

the threat of litigation, or the Section 5 preclearance pro-

cess.”

7 Vote dilution litigation in the 1980s produced majority

black districts in Georgia (the 5th) (Busbee v. Smith, 549 F.Supp.

494 (D.D.C. 1982)), Louisiana (the 2d) (Major v. Treen, 574

F.Supp. 325, 355 (E.D.La. 1983)), and Mississippi (the 2d)

(Jordan v. Winter, 604 F.Supp. 807, 813 (N.D. Miss. 1984)).

Similar litigation in the 1990s produced a majority black

congressional district in Alabama (the 7th) (Wesch v. Hunt, 785

F.Supp. 1491, 1498-99 (S.D. Ala.)), two in Florida (the 3d and

17th), and a third (the 23d) in which blacks and Hispanics

combined were the majority (DeGrandy v. Wetherell, 794

F.Supp. 1076, 1088 (N.D. Fla. 1992)), and one in South Carolina

(the 6th) (Burton v. Sheheen, 793 F.Supp. 1329, 1367-69 (D.S.C.

1992)). During the 1990s Section 5 objections, or threatened

objections, by the Attorney General also resulted in the creation

of two additional majority black districts in Georgia (the 2d and

11th) (Johnson v. Miller, 864 F.Supp. 1354, 1366 (S.D.Ga. 1994)),

one additional district in Louisiana (the 4th) (Hays v. Louisiana,

839 F.Supp. 1188, 1196 n.21 (W.D. La. 1993)), and two in North

Carolina (the 1st and 12th) (Barr v. Shaw, 808 F.Supp. 461, 464

(E.D.N.C. 1992)). The threat of litigation or objections to

preclearance by civil rights organizations was a factor in the

creation of a second majority black district in Texas (the 13th)

(Vera v. Richards, 861 F.Supp. 1304, 1315 (S.D.Tex. 1994)), and

one in Virginia (the 3d). See Bill Wasson, “Wilder Plan Expected

to Win Assembly OK,” The Richmond News Leader, Dec. 3,

1991, p. 1. The two other majority-minority districts in the South

were the 9th (majority black) in Memphis, and the 18th

7

The increase in majority black districts was followed

by an increase in black elected officials. Seventeen of the

majority-minority congressional districts — and none of

the majority white districts — elected a black in 1992. 1990

U.S. Census, Population and Housing Profile, Congres-

sional Districts of the 103rd Congress, C.Q. Weekly Report,

V. 51, 3473-87.8

III. Challenges to the Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act has undeniably been the vic-

tim of its own success. Following the 1992 elections the

courts were flooded with challenges by white voters who

claimed that the majority black districts were unconstitu-

tional racial gerrymanders.® Lawsuits challenging con-

gressional plans were filed in North Carolina (Shaw v.

(majority black and Hispanic) in Texas. Michael Barone & Grant”

Ujifusa, The Almanac of American Politics 1974 (1973).

8 There were also substantial increases in the number of

majority-minority state legislative districts, and a

corresponding increase in black legislators following the 1990

redistricting. In the South, the number of black state senators

increased from 43 to 67, and the number of black house

members from 159 to 213. David A. Bositis, Redistricting and

Representation: The Creation of Majority-Minority Districts and

the Evolving Party System in the South 46-7 (Joint Center for

Political and Economic Studies, 1995).

? Since all districting is designed to advance the interests of

particular voters or groups, e.g., incumbents, Democrats,

farmers, coastal residents, suburbanites, etc., one leading expert

has said that “[a]ll districting is ‘gerrymandering.’ ” Robert G.

Dixon, Jr., Democratic Representation: Reapportionment in Law

and Politics 462 (1968). In Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109, 132

(1986), this Court defined a gerrymander as an electoral

arrangement that denies or degrades “a voter's or a group of

voters’ influence on the political process as a whole.”

8

Barr, 808 F.Supp. at 465-66), Texas (Vera v. Richards, 861

F.Supp. at 1309), Louisiana (Hays v. Louisiana, 839 F.Supp.

at 1190-91), Florida (Johnson v. Mortham, 926 F.Supp. 1460

(N.D.Fla. 1996)), New York (Diaz v. Silver, 932 F.Supp. 462

(E.D.N.Y. 1996)), Virginia (Moon v. Meadows, 952 F.Supp.

1141 (E.D.Va. 1997)), Georgia (Johnson v. Miller, 864

F.Supp. at 1359), Illinois (King v. State Board of Elections,

979 E.Supp. 582 (N.D.Ill. 1996)), South Carolina (Leonard v.

Beasley, Civ. No. 3:96-CV-3540 (D.S.C.)), and Alabama

(Rice v. Smith, CA No. 97-A-715-E (M.D.Ala.)).10

This litigation reflected a well established historical

pattern. As this Court and others have poignantly

observed, political mobilization in the black community,

particularly in the South, has rarely gone unopposed

since Reconstruction onwards. South Carolina v. Katzen-

bach, 383 U.S. 301, 310 (1966) (noting the adoption by

various southern states beginning in 1890 of tests “speci-

fically designed to prevent Negroes from voting”). See

also J. Morgan Kousser, The Shaping of Southern Politics:

Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Part

South, 1880-1910 (1974); Paul Lewinson, Race, Class, and

Party: A History of Negro Suffrage and White Politics in the

South (1932); Armand Derfner, “Racial Discrimination

and the Right to Vote,” 26 Vand. L. Rev. 523 (1973). In

10 Similar challenges were filed against majority black state

legislative districts in South Carolina (Smith v. Beasley, 946

F.Supp. 1174, 1175 (D.S.C. 1996)), Florida (Scott v. U.S. Dept. of

Justice, 920 F.Supp. 1248 (M.D.Fla. 1996)), Texas (Thomas v.

Bush, No. A-95-CA 18655 (W.D.Tex.)), Georgia (Johnson v.

Miller, 929 F.Supp. 1529 (S.D.Ga. 1996)), Louisiana (Currie v.

Foster, No. 97-CV-368 (W.D.La.)), North Carolina (Daly v. High,

No. 5:96 CV 86-V (W.D.N.C.)) and, Ohio (Quilter v. Voinovich,

912 ESupp. 1006 (N.D.Oh. 1995)).

9

modern times the Voting Rights Act, which has been the

single most effective tool of black enfranchisement in our

nation’s history, has become a natural lightning rod for

this opposition. See, e.g., Frank R. Parker, Black Votes

Count 34-5 (1987) (describing as a “massive resistance”

campaign the efforts by Mississippi's white leadership to

blunt the increase in black voter registration after passage

of the 1965 Act).1!

The first of the modern reverse discrimination cases

to reach the Court following the 1990 census was Shaw v.

Reno, a challenge to congressional redistricting in North

Carolina and a precursor to this case.12 In Shaw, the Court

held that plaintiffs who alleged that districts were

11 Similar efforts in other southern states to thwart the civil

rights acts of 1957, 1960, 1964, and 1965 are discussed in the

various state chapters in Quiet Revolution.

12 It is not surprising that the latest backlash erupted in the

context of congressional redistricting. The creation of majority

black districts for county commissions and city councils, while

important at the local level and by no means uncontroversial,

lacked the visibility and impact of the creation of majority black

districts for Congress. Members of Congress, axiomatically,

wield national political power, and the election of blacks to

national office is more likely to galvanize attention and

opposition. There was also the critical issue of the sheer number

of blacks elected to Congress. Courts and social scientists have

frequently commented on the “tipping phenomenon,” where

whites flee a neighborhood or the public schools when the

perception takes hold that there has been “too much”

integration. See, e.g., A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr., Gregory A.

Clarick & Marcella David, “Shaw v. Reno: A Mirage of Good

Intentions with Devastating Racial Consequences,” 62 Ford. L.

Rev. 1593, 1632 n.194 (1994). The unprecedented success of black

congressional candidates in the 1992 elections had a similar

impact, at least for some.

10 .

“bizarre” or “irrational” in shape, and were “unexplain-

able on grounds other than race,” stated a claim for relief

under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. 509 U.S. at 643, 658.

Two years later the Court expanded on Shaw when it

held that a bizarre district shape was not a prerequisite

for a constitutional challenge but was simply one way of

proving a suspect racial classification or purpose. See

Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2485. As the Court explained

in Miller, a plaintiff could establish

either through circumstantial evidence of a dis-

trict’s shape and demographics or more direct

evidence going to legislative purpose, that race

was the predominant factor motivating the leg-

islature’s decision to place a significant number

of voters within or without a particular district.

Id., at 2488. In sum, the plaintiffs’ burden under Miller is

to “show that the State has relied on race in substantial

disregard of customary and traditional districting prac-

tices.” Id. at 2497 (O'Connor, J., concurring).

Applying the rules in Shaw and Miller, the Court has

struck down majority-minority districts in North Carolina

(the 12th) (Shaw v. Hunt, 116 S.Ct. at 1907), Georgia (the

11th) (Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2494) (the 2d) (Abrams

v. Johnson, 117 S.Ct. at 1935), and Texas (the 18th, 29th,

and 30th) (Bush v. Vera, 116 S.Ct. at 1951). Lower courts

have done the same to majority-minority congressional

districts in Florida (the 3d) (Johnson v. Mortham, 926

F.Supp. at 1495), Virginia (the 3d) (Moon v. Meadows, 952

F.Supp. at 1150), Louisiana (the 4th) (Hays v. Louisiana,

936 F.Supp. 360, 371 (W.D.La. 1996)), and New York (the

11

12th) (Diaz v. Silver, CV-95-2591 (E.D.N.Y. Feb. 26,

1997)).13

There is nothing sinister or unlawful about the

desires or efforts of whites to elect candidates of their

choice, including candidates of their own race. To the

contrary, the “freedom to associate with others for the

common advancement of political beliefs and ideas is a

form of ‘orderly group activity’ protected by the First and

Fourteenth Amendments.” Kusper v. Pontikes, 414 U.S. 51,

56-7 (1973) (quoting NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 430

(1963)). What is indefensible is that under the Shaw cases

the freedom of whites to associate for the common

advancement of political beliefs and ideas, including the

right to construct and run in majority white districts, is

deemed constitutionally protected, while the comparable

efforts of blacks and other nonwhites are deemed consti-

tutionally suspect.

IV. Majority White and Majority Nonwhite Districts;

Dual Racial Standards

One principle that has emerged with disturbing clar-

ity from the Shaw cases is that they “place at a dis advan-

© tage the very group, African Americans, whom the Civil

13 Not all the Shaw/Miller challenges have succeeded. The

Court summarily affirmed without opinion lower court

decisions rejecting challenges to congressional plans in

California (DeWitt v. Wilson, 115 S.Ct. 2637 (1995)), and Illinois

(King v. Illinois Board of Election, 118 S.Ct. 877 (1998), aff'g, 979

F.Supp. 582, 619 (N.D.Ill. 1996), as well as a legislative plan in

Ohio (Quilter v. Voinovich, 981 ESupp. 1032 (N.D.Oh. 1997),

aff'd, 118 S.Ct. 1358 (1998)). The Court also affirmed the decision

of the district court rejecting a challenge to a legislative

redistricting settlement in Florida. Lawyer v. Department of

Justice, 117 S.Ct. 2186 (1997).

12

War Amendments sought to help.” Abrams v. Johnson, 117

S.Ct. at 1950 (Breyer, J., dissenting). The Court has never

invalidated a majority white district on account of its

bizarre shape, or because the jurisdiction subordinated its

traditional redistricting principles to race, although there

is a long and continuing history of protecting white

incumbents through the creation of majority white dis-

tricts, including those that are highly irregular in shape

and disregard “traditional” districting principles.

For example, the Congressional Quarterly has

described District 4 in Tennessee (96% white) as “a long,

sprawling district, extending nearly 300 miles . . . from

east to west it touches four States — Mississippi, Alabama,

Kentucky, and Virginia.” Congressional Quarterly, Inc.,

Politics in America 1994: 103rd Congress 1418 (Phil Duncan

ed., 1993). The 11th District in Virginia (81% white) has “a

shape that vaguely recalls the human digestive tract.” Id.

at 1602. District 9 in Washington (85% white) has a “ ‘Main

Street’ [which] is a sixty-mile stretch of Interstate 5.” Id.

at 1635. District 13 in Ohio (94% white) “centers around

two distinct sets of communities . . . [t]he Ohio Turnpike

is all that connects the two.” Id. at 1210. Yet no court,

even after Shaw, has held or suggested that any of these

oddly shaped districts is constitutionally suspect.

To the contrary, such majority white districts have

always been regarded as immune from challenge under

the Court’s often stated principle that a regular looking

14 Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960), is not to the

contrary. In Gomillion, the Court held that the redefinition of the

city of Tuskegee’s boundaries “was not an ordinary geographic

redistricting measure” but was subject to challenge because it

removed most of the city’s black residents denying them “the

right to vote in municipal elections.” 364 U.S. at 341.

13

district shape was not a federal constitutional require-

ment. Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735, 752 n.18 (1973)

(district “compactness or attractiveness has never been

held to constitute an independent federal requirement”).

Even Shaw v. Reno acknowledged that a compact district

shape was “not . . . constitutionally required,” 509 U.S. at

647, an acknowledgment that is difficult to reconcile with

the Court’s contradictory holding that “reapportionment

is one area in which appearances do matter,” id. at 647,

and that the 12th District in North Carolina was subject to

challenge because of its non-compact, or “extremely

irregular,” shape. Id. at 642.

In the Texas redistricting case, filed in 1994, the plain-

tiffs challenged 24 of the state’s 30 congressional districts,

18 of which were majority white. Vera v. Richards, 861

F.Supp. at 1309. The district court invalidated just three

districts, the only two that were majority black and one

that was majority Hispanic. Id. at 1343-44. The court

admitted that the other districts were irregular or bizarre

in shape, but held that they were constitutional because

they were “disfigured less to favor or disadvantage one

race or ethnic group than to promote the re-election of

incumbents.” Id. at 1309. Thus, the oddly shaped majority

white districts, designed to keep white incumbents in

office, were tolerable as “political” gerrymanders, while

the oddly shaped majority black districts, designed to

provide black voters the equal opportunity to elect candi-

dates of their choice, were intolerable as “racial” gerry-

manders.

On appeal, this Court affirmed. According to the

Court “political gerrymandering” was not subject to strict

scrutiny. Bush v. Vera, 116 S.Ct. at 1954. For that reason

“irregular district lines” could be drawn for “incumbency

14

protection” and “to allocate seats proportionately to

major political parties.” Id. See also id. at 1972 (“[d]istricts

not drawn for impermissible reasons or according to

impermissible criteria may take any shape, even a bizarre

one”) (Kennedy, J., concurring). Amicus respectfully sub-

mits that the creation of a dual standard in redistricting

depending on whether a district is majority white or

nonwhite is inconsistent with fundamental notions of

equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment.15

The Shaw cases have also established special standing

rules to facilitate challenges by white voters to majority-

minority districts. The Court has described standing as

“an essential and unchanging part of the case-or-contro-

versy requirement of Article III,” that includes, among

other things, the requirement of “an ‘injury in fact’ — an

invasion of a legally protected interest which is . . .

concrete and particularized.” Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife,

504 U.S. 555, 560 (1992).

In Shaw v. Reno, however, the plaintiffs “did not claim

that the General Assembly’s reapportionment plan

unconstitutionally ‘diluted’ white voting strength.” Shaw

v. Reno, 509 U.S. at 641.1 Even more dramatically, the

15 Blacks have also frequently been denied the advantages

of incumbency. In Johnson v. Miller, 929 F.Supp. 1552, 1565

(5.D.Ga. 1995), the district court took note of the state’s historic

policy of drawing district lines “so incumbents remain in their

districts in a new plan and to avoid placing two incumbents in

the same districts.” In its remedial plan, however, the court

placed a black incumbent (McKinney) in a new district and put

a white incumbent in the district of another black incumbent

(Bishop). Id.

16 Nor, as Justice White pointed out, could they. Whites

were 79% of the state’s VAP but a majority in ten (83%) of its 12

15

three-judge court in Miller made an express finding that

“the plaintiffs suffered no individual harm; the 1992 con-

gressional redistricting plans had no adverse conse-

quences for these white voters.” Johnson v. Miller, 864

F.Supp. at 1370. The lack of a concrete and personal injury

should have denied both the Shaw and Miller plaintiffs

standing to bring their cases to federal court.

The Court nonetheless found that the plaintiffs in

each case had standing because they alleged that their

right to participate in a “color-blind” electoral process

had been violated. Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. at 641; Miller v.

Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2485-86 (the essence of plaintiffs’

equal protection claim is not that their voting strength

has been minimized or canceled out, but “that the State

has used race as a basis for separating voters into dis-

tricts”). The injury identified by the Court was in being

“stereotyped” or “stigmatized” by a racial classification.

Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2486; Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S.

at 643.

In prior cases involving black plaintiffs, however, the

Court held that a similar abstract, hypothetical, or stig-

matic injury was not sufficient to confer standing to chal-

lenge discriminatory governmental action. For example,

in Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737, 754 (1984), the Court

rejected a challenge by blacks to alleged discrimination

congressional districts. Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. at 666-67 (White,

J., dissenting). One commentator has described the Shaw

plaintiffs “not as injured parties, but as spoilers, intent on

eliminating the new majority-black districts as a matter of

principle.” Frank R. Parker, “The Constitutionality of Racial

Redistricting: A Critique of Shaw v. Reno,” 3 D. Col. L. Rev. 1, 9

(1995). :

16

by the Internal Revenue Service because “stigmatic

injury, or denigration” suffered by members of a racial

group when the Government discriminates on the basis

of race was insufficient harm to confer standing. Allow-

ing standing in the absence of direct injury would,

according to the Court, “transform the federal courts into

‘no more than a vehicle for the vindication of the value

interests of concerned bystanders.” ” Id. at 756 (quoting

United States v. Students Challenging Regulatory Agency

Procedures, 412 U.S. 669, 687 (1973)).

Shaw and Miller have thus established a liberal rule of

standing in the absence of direct injury for whites chal-

lenging majority-minority districts that is different from

the restrictive rule of standing applied to blacks challeng-

ing official action as being discriminatory.

In addition, Shaw also relaxed the requirement that

white plaintiffs prove the state intended to discriminate

against them in enacting a challenged redistricting plan.

The Shaw v. Reno plaintiffs did not claim that the state's

plan was enacted for the purpose of diluting white voting

strength. 509 U.S. at 641. Indeed, the legislature's admit-

ted purpose in creating majority black districts was the

entirely nondiscriminatory one of complying with the

Voting Rights Act. Id. at 635, 655. The Court reasoned,

however, that even though a districting plan was facially

neutral, a racial classification was apparent or “express”

where a majority black district had a “bizarre” shape, and

that accordingly “[n]o inquiry into legislative purpose is

necessary.” Id. at 642.17 This is markedly different than

17 The cases principally relied upon by the Court,

Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v. Feeney, 442 U.S.

256 (1979), and Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

17

the standard applied by the Court in other civil rights

contexts.

Since Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), the

Court has required proof of a discriminatory purpose to

establish a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. And

in City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980), the Court

applied that rule to the voting context. In setting aside a

constitutional challenge by black voters to municipal at-

large elections, the Court stressed that “only if there is

purposeful discrimination can there be a violation of the

Equal Protection Clause.” Id. at 66. Even proof that black

voting strength in the city had been diluted was, accord-

ing to the Court, “most assuredly insufficient to prove an

unconstitutionally discriminatory purpose.” Id. at 73.

Accord, City of Memphis v. Greene, 451 U.S. 100, 119 (1981)

(“the absence of proof of discriminatory intent forecloses

any claim that the official action challenged in this case

violates the Equal Protection Clause”).18

Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977), do not support its

analysis. In Arlington Heights, the Court held that a severe

discriminatory impact may support an inference of

discriminatory purpose, but that “[p]roof of racially

discriminatory intent or purpose is required to show a violation

of the Equal Protection Clause.” 429 U.S. at 265. In Feeney, in a

passage omitted in Shaw v. Reno, the Court held that “even if a

neutral law has a disproportionately adverse effect upon a racial

minority, it is unconstitutional under the Equal Protection

Clause only if that impact can be traced to a discriminatory

purpose.” 442 U.S. at 272. A fortiori, the cases relied upon by the

Court do not support the proposition that a facially neutral

classification that has no discriminatory impact can be

unconstitutional absent proof of a discriminatory purpose.

18 In light of Shaw, whites challenging discrimination under

the Constitution also have a lower burden of proof than blacks

challenging discrimination under the Voting Rights Act. Such a

18

Shaw/Miller's new cause of action based on bizarre

district shape, new dual standard depending on whether

a district is majority white or non-white, and absence of

the requirements of showing a discriminatory purpose

and effect now allow the Fourteenth Amendment, which

was intended to prohibit discrimination against minor-

ities, see The Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall) 36, 81

(1873) (the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted to rem-

edy “discrimination against the negroes as a class, or on

account of their race”), to be used to destroy majority-

minority districts and deprive blacks of equal political

opportunities.

V. Mistaken Assumptions about Segregation

The underlying premise of the redistricting decisions

is that creating nonwhite majority districts is a form of

“segregation” which harms individuals and society. Shaw

v. Reno, 509 U.S. at 641. Under this view, individuals are

harmed because of “the offensive and demeaning

assumption that voters of a particular race, because of

their race, ‘think alike, share the same political interests,

and will prefer the same candidates at the polls.” ” Miller

v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2486. Society is allegedly harmed

because “ ‘[r]acial gerrymandering . . . may balkanize us

into competing racial factions.”” Id. As demonstrated

below, each of these premises is seriously flawed.

The majority-minority districts in the South created

after the 1990 census, far from being segregated, were the

result is anomalous given the purpose of the Act to ease the

standard of proof in statutory challenges. Thornburg v. Gingles,

478 U.S. at 43-4.

19

most racially integrated districts in the country. They con-

tained an average of 45% non-black voters. Bositis, Redis-

tricting and Representation at 28. No one familiar with Jim

Crow could confuse the highly integrated redistricting

plans of the 1990s with racial segregation under which

blacks were not allowed to vote or run for office. As

Justice Stevens has recognized, plans containing majority-

minority districts are a form of “racial integration.” Miller

v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2498 (Stevens, ]J., dissenting). More-

over, the notion that majority black districts are “segre-

gated,” and that the only integrated districts are those in

which whites are the majority, is precisely the sort of race

based concept which the Court has consistently deplored.

The premises of Shaw and Miller are flawed for the

further reason that race is not merely an “assumption” or

“stereotype,” it is also a social and political fact of Ameri-

can life.1® See generally Nathan Glazer, “Reflections on

Citizenship and Diversity,” in Diversity and Citizenship:

Rediscovering American Nationhood (Gary J. Jacobsohn &

Susan Dunn eds., 1996). Indeed, it is the acknowledgment

-of that fact that led Congress to enact the Voting Rights

Act. South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. at 337 (describ-

ing the purpose of the Act to insure that “millions of non-

white Americans will now be able to participate for the

first time on an equal basis in the government under

which they live”).

19 This is very different from saying that race is a scientific

fact. See Critical Race Theory: The Concept of “Race” in Natural

and Social Science ix (E. Nathaniel Gates ed., 1997) (scientists

are now agreed that “race” has “no scientifically verifiable

referents”). oy

20

Lower courts applying the Act have reached the

same conclusion. In Miller v. Johnson, for example, the

trial court concluded that racial discrimination was such

a pervasive feature of life in Georgia that it took judicial

notice of it and dispensed with any requirement that it be

proved. The district court also acknowledged that, on the

basis of existing statewide racial bloc voting patterns, the

Voting Rights Act required the creation of a majority

black congressional district in the Atlanta metropolitan

area to avoid dilution of black voting strength. Johnson v.

Miller, 922 F.Supp. at 1568. Given the existence of racial

bloc voting, treating blacks and whites as having differ-

ent voting preferences is to acknowledge reality, not

indulge stereotypes.

Nor is there any evidence that majority-minority dis-

tricts have either caused or increased social or other

harm. In 1982, opponents of the amendment of Section 2

claimed that the creation of majority-minority districts

would “deepen the tensions, fragmentation and outright

resentment among racial groups,” Voting Rights Act:

Hearings Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the

Senate Comm. on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 662

(1982) (statement of John H. Bunzel), “pit race against

race,” id. at 745 (statement of Michael Levin), “foster

polarization,” id. at 1328 (statement of Donald L.

Horowitz), and “compel the worst tendencies toward

race-based allegiances and divisions.” Id. at 1449 (letter

from William Van Alstyne). Congress considered and

rejected these claims because there was no evidence to

support them. It concluded that the amendment would

not “be a divisive factor in local communities by empha-

sizing the role of racial politics.” S.Rep. No. 417, 97th

21

Cong., 2d Sess. 32-3 (1982). It found there was “an exten-

sive, reliable and reassuring track record of court deci-

sions using the very standard which the Committee bill

would codify.” 1d.20

None of the Shaw cases, moreover, indicate that any

of the theoretical harms suggested by the majority have

in fact come to pass. In Miller v. Johnson, the witnesses at

trial testified without contradiction that the challenged

plan had not increased racial tension, caused segregation,

imposed a racial stigma, deprived anyone of representa-

tion, caused harm, or guaranteed blacks congressional

seats. Johnson v. Miller, Trial Transcript, Vol. III, p. 268;

Vol. IV, pp. 194, 106, 239, 240, 242; Vol. VI, pp. 36, 38, 45,

47, 56, 58, 117, 120. The district court concluded that “the

1992 congressional redistricting plans had no adverse

consequences for these white voters.” Johnson v. Miller,

864 F.Supp. at 1370.

The district court reached a similar conclusion in

Hays v. Louisiana. Although holding the state’s congres-

sional plan unconstitutional under Shaw, the district court

nonetheless acknowledged “the great benefits that are

derived by an increase in minority representation in gov-

ernment.” 862 F.Supp. 119, 128 (W.D.La. 1994) (Shaw, J.,

20 In the political sphere, where Congress has “a specially

informed legislative competence,” this Court has held that its

duty is to determine only if there is “a basis upon which

Congress might predicate a judgment” that a particular practice

was a valid means of carrying out the commands of the

Constitution. Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 656 (1966).

Accord, South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. at 337. There

clearly was a basis upon which Congress could conclude that

majority-minority districts did not cause social or other harm

and were thus a valid means of implementing the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments.

22

concurring). Minority elected officials, the court wrote,

“have shown that they perform admirably,” that their

efforts in government “provide positive role models for

all black citizens,” and that they “insure that the legal

obstacles to minority advancement in all areas of life will

be eliminated.” Id. In a similar vein, one veteran civil

rights lawyer has said that, based on his experience in

Mississippi, “the creation of majority-minority districts

and the subsequent election of minority candidates

reduces white fear and harmful stereotyping of minority

candidates, ameliorates the racial balkanization of Ameri-

can society, and promotes a political system in which race

does not matter as much as it did before.” Parker, 3 D.

Col. L. Rev. at 19-20.

VI. The Comparison with Affirmative Action

Prior to Shaw, the Court frequently noted that one of

the essential purposes of redistricting was to “reconcile

the competing claims of political, religious, ethnic, racial,

occupational, and socioeconomic groups.” Davis v. Ban-

demer, 478 U.S. at 147 (O'Connor, J., concurring). For that

and other reasons, “legislators necessarily make judg-

ments about the probability that the members of certain

identifiable groups, whether racial, ethnic, economic, or

religious, will vote in the same way.” City of Mobile v.

Bolden, 465 U.S. at 87 (Stevens, J., concurring). See United

Jewish Organizations of Williamsburg, Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S.

144, 176 n.4 (1977) (“[i]t would be naive to suppose that

racial considerations do not enter into apportionment

decisions”).

Voting districts have regularly been drawn to accom-

modate the interests of racial or ethnic groups, such as

Irish Catholics in San Francisco, Italian-Americans in

23

South Philadelphia, Polish-Americans in Chicago, and

Anglo-Saxons in North Georgia. Miller v. Johnson, 115

S.Ct. at 2505 (Ginsburg, J., dissenting); Busbee v. Smith,

549 F.Supp. at 502 (in the state’s 1980 congressional plan

“keeping the cohesive [majority white] mountain coun-

ties together was crucial”). The Court specifically rejected

a challenge by white voters in 1977 to a New York plan

that “deliberately used race in a purposeful manner” to

create nonwhite majority state legislative districts in

order to comply with the Voting Rights Act. United Jewish

Organizations of Williamsburg, Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S. at 165.

The Court held that the use of race to insure fairness and

inclusiveness in redistricting did not impose a racial

stigma and was proper where white voting strength was

not diluted. Id. at 179-80.

In requiring striet scrutiny of nonwhite majority dis-

tricts, i.e., a showing that the districts are “narrowly

tailored to achieve a compelling interest,” Miller v. John-

son, 115 S.Ct. at 2490, the Miller majority drew heavily

upon the affirmative action cases, indicating that major-

ity-minority districts were simply another form of race

based preferences. Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2482.21

21 In support of this proposition, Miller cited Adarand

Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 115 5.Ct. 2097, 2113 (1995) (subjecting

to strict scrutiny “all racial classifications, imposed by whatever

federal, state, or local governmental actor”), City of Richmond

v. J.LA. Croson, Co., 488 U.S. 469, 494 (1989) (declaring

unconstitutional a municipal set aside for minority contractors),

and Wygant v. Jackson Board of Ed., 476 U.S. 267, 274 (1986)

(invalidating teacher layoff provisions of an affirmative action

agreement). ;

24

Whether or not one thinks the affirmative action

cases were rightly decided, their application to redistrict-

ing ignores the fundamental distinction between the race

conscious allocation of limited employment or contrac-

tual opportunities and the far different task of reconciling

the claims of political, ethnic, racial, and other groups in

the redistricting process. See Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. at

675 (“efforts to remedy minority vote dilution are wholly

unlike what typically has been labeled ‘affirmative ac-

tion’ ”) (White, J., dissenting). If anything, the current

challenges to affirmative action only highlight the impor-

tance of assuring equal opportunity in the political pro-

cess.

In light of the Court's recent decisions, racial minor-

ities are now the only group that is targeted for special

disadvantages in redistricting. All other groups — politi-

cal, religious, occupational, or socioeconomic - may orga-

nize themselves freely and press for recognition in the

redistricting process. The efforts of non-whites alone are

subject to the exacting and debilitating standards of strict

scrutiny. See James U. Blacksher, “Dred Scott's Unwon

Freedom: The Redistricting Cases As Badges of Slavery,”

39 How. L. J. 633, 634 (1996) (“it is black and Latino

citizens alone who may not choose to associate with each

other freely and try to optimize their legislative influence

in pursuit of a common political agenda”) (footnote omit-

ted). Such a result cannot be reconciled with the purposes

of the Fourteenth Amendment. As Justice Stevens wrote

in Shaw:

If it is permissible to draw boundaries to pro-

vide adequate representation for rural voters,

for union members, for Hasidic Jews, for Polish

Americans, or for Republicans, it necessarily fol-

lows that it is permissible to do the same thing

for members of the very minority group whose

25

history in the United States gave birth to the

Equal Protection Clause.

509 U.S. at 679 (Stevens, J., dissenting).

VII. The Shaw /Miller Standards Are Unworkable

The Shaw/Miller standards have left legislators in a

quandary as to when the consideration of race in redis-

tricting is impermissible, permissible, or required.

According to the Court, a legislature may properly “be

aware of racial demographics,” but it may not allow race

to predominate in the redistricting process. Miller v. John-

son, 115 S.Ct. at 2488. A state “is free to recognize com-

munities that have a particular racial makeup, provided

its action is directed toward some common thread of

relevant interests.” Id. at 2490. Redistricting may be per-

formed “with consciousness of race.” Bush v. Vera, 116

S.Ct. at 1951. Indeed, it would be “irresponsible” for a

State to disregard the racial fairness provisions of the

Voting Rights Act. Id. at 1969 (O'Connor, J., concurring).

A state may therefore “create a majority-minority district

without awaiting judicial findings” if it has a strong basis

in evidence for avoiding a Voting Rights Act violation. Id.

‘at 1970. Even the Court has acknowledged that it “may be

difficult” to make and apply such distinctions. Miller v.

Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2488.

The Justices who have disagreed with the Court's

new decisions have at various times said that the Shaw

standards are “unworkable,” Abrams v. Johnson, 117 S.Ct.

at 1949 (Breyer, ]., dissenting), Bush v. Vera, 116 S.Ct. at

2011 (“[t]he Court has been unable to provide workable

standards”) (Souter, J., dissenting), are “a jurisprudential

wilderness that lacks a definable constitutional core,”

Bush v. Vera, 116 S.Ct. at 1975 (Stevens, J., dissenting), and

26

“render ] redistricting perilous work for state legisla-

tures,” Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. at 2507 (Ginsburg, J.,

dissenting). Justice Souter has recognized that “it is as

impossible in theory as in practice to untangle racial

considerations from the application of traditional district-

ing principles in a society plagued by racial-bloc voting

with a racial minority population of political signifi-

cance.” Id. at 2005-06 (dissenting).22

Because of the absence of clear and reliable standards

the courts have increasingly been drawn into redistrict-

ing, which this Court has recognized “is primarily the

duty and responsibility of the State through its legislature

or other body, rather than of a federal court.” Chapman wv.

Meier, 420 U.S. 1, 27 (1975). Accord, Growe v. Emison, 507

U.S. 25, 34 (1993). Faced with the prospect of being sued

for a constitutional violation if they create majority-

minority districts and sued for a Voting Rights Act viola-

tion if they do not, states will be strongly tempted to

22 The views of the dissenters are widely shared by others.

See, e.g., Bernard Grofman & Lisa Handley, “1990s Issues in

Voting Rights,” 65 Miss. L. J. 205, 215 (1995) (Shaw “did not

establish clearly manageable standards”); T. Alexander

Aleinikoff & Samuel Issacharoff, “Race and Redistricting:

Drawing Constitutional Lines After Shaw v. Reno,” 92 Mich. L.

Rev. 588, 651 (1993) (“[a]t the end of the day, Shaw remains an

enigmatic decision”); Parker, 3 D. Col. L. Rev. at 43 (the Shaw

standards are “vague and subjective”); Higginbotham, et al., 62

Ford. L. Rev. at 1603 (describing Shaw as “obscure”); Pamela S.

Karlan, “All Over the Map: The Supreme Court's Voting Rights

Trilogy,” 1993 Sup. Ct. Rev. 245; J. Morgan Kousser, “Shaw v.

Reno and the Real World of Redistricting and Representation,”

26 Rut. L. J. 625 (1995).

27

leave redistricting to the federal courts.23 And those that

do not will likely end up in court anyway. The flood of

litigation generated by Shaw is itself proof of the accuracy

of Justice Breyer’s observation that, given the subjective

nature of the applicable standards, “[a]ny redistricting

plan will generate potentially injured plaintiffs, willing

and able to carry on their political battles in a judicial

forum.” Abrams v. Johnson, 117 S.Ct. at 1950 (dissenting).

VIII. The Significance of Black Victories in 1996

In Abrams v. Johnson the Court cited the election of

Cynthia McKinney and Sanford Bishop, the incumbents

from the old 11th and 2d Districts in Georgia, to support

its finding that whites had shown a “general willingness”

to vote for black candidates and its conclusion that Sec-

tion 2 did not require the creation of more than one

majority black district in Georgia. 117 S.Ct. at 1936.

Despite the white votes they received, the voting in

McKinney's and Bishop's elections was in fact racially

polarized.

In the Democratic primary, McKinney got only 13%

of the white vote. She won the nomination because she

got most of the black vote and whites mainly stayed

home or voted in the Republican primary. White turnout

23 That is what Georgia did. After the remand in Miller v.

Johnson, the legislature met in special session to redistrict the

Congress. After several weeks of discussion and plan drawing,

the legislature adjourned without taking action, leaving

redistricting to the federal court. Abrams v. Johnson, 117 S.Ct. at

1929. The chair of the senate reapportionment committee

lamented that “[nJobody knows what they're doing.” Mark

Sherman, “Redrawn Districts Expected To Face Challenge,”

.Atlanta Journal & Constitution, Aug. 2, 1995, p. Bé6.

28

was extremely low — only 11% of registered voters com-

pared to 31% for blacks. As a consequence, the electorate

in the Democratic primary was effectively majority black.

Abrams v. Johnson, Nos. 95-1425 & 95-1460, Response of

Appellants Lucious Abrams, Jr., et al., to Appellees’

Motion to Supplement the Record on Appeal, p. 2.

Running in a heavily Democratic district in the gen-

eral election, McKinney increased her percentage of the

white vote, but voting was still along racial lines. Most

blacks again voted for McKinney while approximately

70% of whites voted for her white Republican opponent.

David A. Bositis, “The future of majority-minority dis-

tricts and black and Hispanic legislative representation,”

in Redistricting and Minority Representation 12 (Bositis ed.,

1998). The voting in the new 2d District was similarly

polarized. In the general election Bishop got most of the

black vote but approximately 65% of whites voted for his

white opponent. Bositis, “The future of majority-minority

districts” at 14.

McKinney has credited her victory to the fact that she

was initially elected in a majority black district and had

an opportunity to establish a track record of service to

constituents of both races. Cynthia A. McKinney, “A

Product of The Voting Rights Act,” The Washington Post,

Nov. 26, 1996, p. A15. Non-incumbent blacks, by contrast,

who ran in majority white congressional districts in 1996

in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Texas all lost. Bositis, “The

future of majority-minority districts” at 38-9. McKinney

and Bishop were reelected in 1998, but again both were

running with the strong advantage of incumbency.

www2 state.ga.us/elections/federal.htm.

Given the persistent patterns of racial bloc voting

over time in the South, it is prudent to suggest that the

29

real test of the new majority white congressional districts

which have elected minorities will come when non-

incumbent minorities run for office. The recent elections

may be a sign of a gradual thaw in voter attitudes. If so,

they will underscore the value of highly integrated major-

ity-minority districts to society and voters of all races in

helping to ameliorate the affliction of racial bloc voting.

But in the meantime, it is premature to claim that the

electorate is suddenly color blind and that racial bloc

voting no longer exists. See Bositis, “The future of major-

ity-minority districts” at 15 (“[d]espite the noteworthy

election of four black U.S. representatives in majority-

white districts in 1996, there is little reason to believe that

any significant barrier has been breached or that electoral

politics in the United States have become de-racialized to

any significant degree”); Pildes, 108 Harv. L. Rev. at 1361

(describing the color blind model of politics in the South

as “among the great myths currently distorting public

discussion”).

. 30

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated herein the judgment below

should be reversed. To the extent that Shaw v. Reno and its

progeny are inconsistent with that result, they should be reconsidered.

Respectfully submitted,

LAUGHLIN McDonNALD

Counsel of Record

NEL BRADLEY

MAHA ZAK

CrisTiINA CORREIA

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

44 Forsyth Street

Suite 202

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-2721

STEVEN R. SHAPIRO

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

125 Broad Street

New York, NY 10004

(212) 549-2500

® Counsel for Amicus Curiae

x